The Inclusive Professional Framework for Societies: Changing Mental Models to Promote Diverse, Equitable, and Inclusive STEM Systems Change

- 1Amplifying the Alliance to Catalyze Change for Equity in STEM Success (ACCESS+), Washington, DC, United States

- 2ProActualize Consulting, LLC, Moscow, ID, United States

- 3University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

- 4INCLUDES Aspire Alliance, Madison, WI, United States

- 5University of Connecticut, Mansfield, CT, United States

- 6Women in Engineering, ProActive Network, Washington, DC, United States

- 7High Point University, High Point, NC, United States

- 8Katalytik, Christchurch, United Kingdom

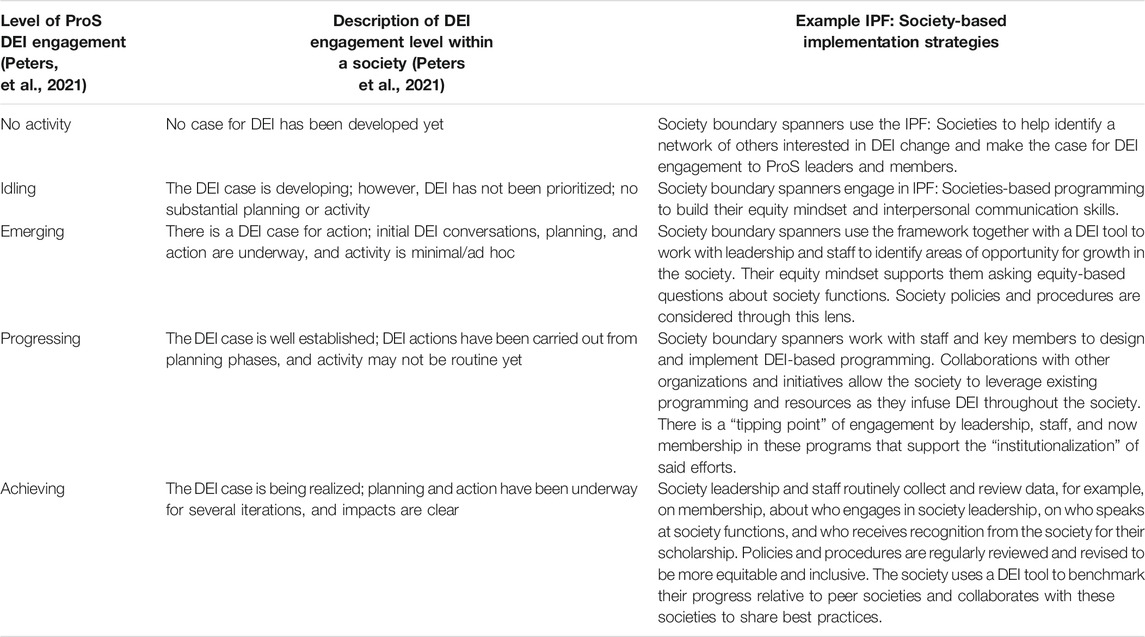

Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) professional societies (ProSs) are uniquely positioned to foster national-level diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) reform. ProSs serve broad memberships, define disciplinary norms and culture, and inform accrediting bodies and thus provide critical levers for systems change. STEM ProSs could be instrumental in achieving the DEI system reform necessary to optimize engagement of all STEM talent, leveraging disciplinary excellence resulting from diverse teams. Inclusive STEM system reform requires that underlying “mental models” be examined. The Inclusive Professional Framework for Societies (IPF: Societies) is an interrelated set of strategies that can help ProSs change leaders (i.e., “boundary spanners”) and organizations identify and address mental models hindering DEI reform. The IPF: Societies uses four “I's”—Identity awareness and Intercultural mindfulness (i.e., equity mindset) upon which inclusive relationships and Influential DEI actions are scaffolded. We discuss how the IPF: Societies complements existing DEI tools (e.g., Women in Engineering ProActive Network's Framework for Promoting Gender Equity within Organization; Amplifying the Alliance to Catalyze Change for Equity in STEM Success' Equity Environmental Scan Tool). We explain how the IPF: Societies can be applied to existing ProS policy and practice associated with common ProS functions (e.g., leadership, membership, conferences, awards, and professional development). The next steps are to pilot the IPF: Societies with a cohort of STEM ProSs. Ultimately, the IPF: Societies has potential to promote more efficient, effective, and lasting DEI organizational transformation and contribute to inclusive STEM disciplinary excellence.

Inclusive Stem Disciplinary Excellence Requires Systems Reform

Addressing complex global challenges, such as climate change and health disparities, requires optimal engagement of people trained in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Because diverse teams embody enhanced capacity for problem solving, innovation, and resilience, they advance disciplinary excellence in a way that homogenous groups cannot (e.g., Page, 2007; Borman et al., 2010; Page, 2017; McGee, 2020). Consequently, not only are more STEM-trained people needed, but specifically more diverse STEM-trained people are needed.

Unfortunately, STEM cultures often discourage diversity by reproducing exclusionary norms and values (Tonso, 1996, 1999, 2007; Seymour and Hewitt, 1997; Pawley and Tonso, 2011; BaillieKabo and Reader, 2012; Riley et al., 2014; Cech and Rothwell, 2018; Hughes, 2018; McGee, 2020). Current US STEM systems privilege white, and/or men in STEM, and are typically perceived as unwelcoming by marginalized groups, especially women from various backgrounds (Metcalf et al., 2018; McGee, 2020; Campbell-Montalvo et al., 2021a). Expression of majority priority is manifest in complex ways, such as equating masculinity with technical ability, embracing and centering whiteness (Hacker, 1981, 1989; Eisenhart and Finkel, 1998; Lohan and Faulkner, 2004; Faulkner, 2007; Foor et al., 2007; Tonso, 2007; Pawley and Tonso, 2011; BaillieKabo and Reader, 2012), and fostering the false idea that STEM is an apolitical, value-free, empirical meritocracy (McGee, 2020; Metcalf, 2017). Systems of power, privilege, and oppression intersect with those shaped by gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality, disability, nationality, class, and more (Crenshaw, 1989; Crenshaw 1991; Griffin and Museus, 2011; Collins, 2015; Metcalf, 2016; Warner et al., 2016; Metcalf et al., 2018). Collectively, these intersecting systems influence opportunities, create barriers, and can in turn promote exclusionary experiences for a variety of individuals, including women and other groups underrepresented in STEM. These experiences of exclusionary STEM systems are often replicated in, and sustained, not just in established STEM work environments but also by a STEM education system that socializes the next generation of the STEM workforce to abide by and reproduce these norms and values (Trouillot, 1995; Foucault, 2007; Tonso, 2007; Tonso, 2014).

While STEM systems reform is clearly needed to attract, retain, and support a thriving diverse STEM talent pool, there is widespread expectation that minoritized and marginalized people will, and should be, the ones tasked with changing a system by which they are oppressed and largely excluded (Forrester, 2020). Majoritized people receive disproportionate power within the current system, so it is incumbent on them to be leaders in STEM system change to promote inclusive disciplinary excellence. This change must be supported through both “intentional introspection and subsequent action” (Chaudhary and Berhe, 2020, pg. 3).

Uncovering Professional Society Mental Models

Mental models are “deeply held beliefs and assumptions, and taken-for-granted ways of operating that influence how we think, what we do, and how we talk” (Kania et al., 2018, p. 4). We argue that intentional introspection of mental models can foster systems change. Systems change is “shifting the conditions that are holding the problem in place” (Kania et al., 2018). Kania et al. (2018) identified six conditions of systems change that are explicit (i.e., policies, practices, resource flows), semi-explicit (i.e., relationships and connections, power dynamics), and implicit (i.e., mental models). Mental models hold the other conditions in place. Unless we learn to work at the mental models level, other structural changes “...will, at best, be temporary or incomplete” (Kania et al., 2018, p.8). While work addressing mental models has been increasing in academic institutions (e.g., NSF ADVANCE-funded initiatives) and industry settings, few projects have undertaken these efforts within professional societies (ProSs).

Given the multiple, varied disciplinary functions performed by STEM ProSs, and that STEM ProSs often engage other STEM system gatekeepers (e.g., corporate, laboratory, and academic organizations), STEM ProSs are uniquely positioned as critical levers for STEM systems change (e.g., National Academy of Sciences et al., 2005). Peters and others (in press) identify 11 functions performed by STEM ProSs (i.e., governance and leadership; membership; programming; professionalization; student chapters; prizes, awards, and funding; outreach and engagement; employment; advocacy; and publishing). Through functions such as these, the ProS reinforces mental models regarding how the discipline “looks, feels, and acts.” Leaders are identified, innovations celebrated, and the next generation is nurtured. For example, students enter STEM degree programs with varying levels of social capital (Skvoretz et al., 2020), and ProSs keep them in their programs (Smith et al., 2021; Campbell-Montalvo et al., in press). Some STEM ProSs are actively engaged in STEM systems change to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) through STEM ProS functions (e.g., Segarra et al., 2020a; Segarra et al., 2020b; Campbell-Montalvo et al., in press, Campbell-Montalvo et al., 2020; Etson et al., 2021). However, we believe that to foster greater engagement by STEM ProSs, more STEM ProS-specific tools are needed, especially those that can help make explicit and reframe mental models underpinning STEM ProS functions.

The IPF: Societies as a Tool for Mental Model Changes

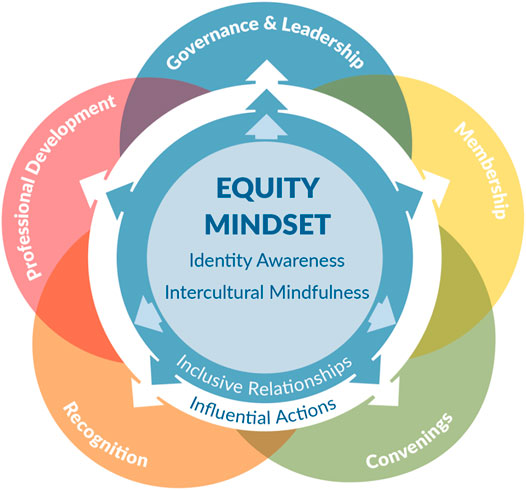

We offer the Inclusive Professional Framework for Disciplinary and Professional Societies (IPF: Societies) as an approach to help elucidate and adjust mental models that underlie STEM ProS functions (INCLUDES Aspire Alliance National Change, n.d.). The IPF: Societies is a framework that can be used to explore how internal conditions support and hinder current ProS DEI aspirations and help set a foundation for lasting organizational change. Specifically, the IPF: Societies is a research-informed approach that focuses on awareness and skill development to build an equity mindset—an orientation in which actions are grounded in understanding of how social positionings affect access to resources. This mindset creates greater capacity for inclusive relationships and supporting actions that are focused on DEI change. The IPF: Societies includes the four “I's”:

1. Identity awareness,

2. Intercultural mindfulness,

3. Inclusive relationships, and

4. Influential DEI actions.

The IPF: Societies derives from the Inclusive Professional Framework for Faculty (IPF: Faculty). The IPF: Faculty was developed by the Aspire Alliance's National Change Initiative, which is part of the National Science Foundation's Inclusion across the Nation of Communities of Learners of Underrepresented Discoverers in Engineering and Science (NSF INCLUDES). The IPF: Societies was developed with input from leaders from the NSF ADVANCE-funded Amplifying the Alliance to Catalyze Change for Equity in STEM Success (ACCESS+), (n.d) Initiative, whose mission is to “accelerate the awareness, adoption, and adaptation of NSF ADVANCE evidence based, gender-related, DEI policies, practices, and programs within and across STEM ProSs, by providing support to STEM ProS boundary spanners.” Through partnership with ACCESS+ the IPF: Societies graphic was created, along with example functions (see Figure 1); and the model was tailored to a ProS audience, refined, and piloted. Ongoing work through ACCESS+ will support engagement and continued refinement through use with future cohorts of ACCESS+ ProSs and the development of complementary resources.

FIGURE 1. The IPF: Societies graphic with five example professional society functions (INCLUDES Aspire Alliance National Change, n.d.).

Given the parallel role that mental models play in university and ProS systems, we propose that it is valuable to adapt the IPF for use in ProSs. Like the IPF: Faculty, the IPF: Societies at its core focuses on building an equity mindset through identity awareness and intercultural mindfulness and then puts that mindset into practice through reinforcing skills that support inclusive relationships. Where the frameworks (i.e., IPF: Faculty and IPF: Societies) differ is in the contexts and roles of those applying the framework. The IPF: Faculty was developed to promote inclusive skill development for faculty across their roles within academic institutions (e.g., teaching, advising, research mentoring, collegiality, and leadership) (Gillian-Daniel et al., 2021b; Dukes et al., in press). For the IPF: Societies, application occurs, initially by society DEI change leaders (i.e., “boundary spanners”), in the various functions that the society performs for its members and discipline, as discussed in greater detail below (see Figure 1: IPF: Societies with example ProS functions).

The IPF: Societies has dual target audience foci: 1) DEI change leaders (individual focus) and 2) the ProSs as a system (organizational focus). Key individuals within the organizational system are ProS DEI change leaders, known as “boundary spanners,” who are people within an organization who work to connect ideas, resources, and stakeholders (Hill, 2020). These individuals engage in five key behaviors: 1) finding—identifying knowledge and resources outside one's organization to advance innovation, research, and development (Ancana and Caldwell, 1992; Tushman and Scanlan, 1981); 2) translating—making sense of what is found for modification and application within one's own organization (Katz and Tushman, 1981); 3) diffusing—sharing what is gained from extra-institutional connections with fellow organizational members (Rogers, 2003); 4) gaining support—laying the political foundation and support within an organization to implement innovation (Brion et al., 2012; Faraj and Yan, 2009); and 5) social “weaving” behaviors by being the bridge wherewith to connect diverse stakeholders from multiple organizations under a common purpose (Burt, 1992; Kania and Kramer, 2011). Boundary spanners are an ideal lever for enacting and promoting DEI change given that they are often in positions to reach other boundary spanners in their ProSs and beyond (Aldrich and Herker, 1977; Katz and Tushman, 1981; Ancona and Caldwell, 1992; Hill, 2020). We propose that uptake of the IPF: Societies by boundary spanners to develop and refine DEI awareness, knowledge, and skills can better position these change leaders to make systemic changes within their ProS. This in turn has potential ripple effects extending to the wider STEM system (Leibnitz et al., 2021). Similarly, by STEM ProSs using the IPF: Societies to explore the ProS organizational system, both internal-focus (i.e., the STEM ProS business infrastructure) and external-focus (i.e., member and disciplinary serving STEM ProS infrastructure) DEI awareness and organizational capacity are enhanced, better positioning ProSs to enact DEI systems change.

Figure 1 depicts the progression of the IPF: Societies' processes, showing how the equity mindset is developed and expands into relationships and actions that guide ProS core functioning, catalyzing STEM DEI systems change. We propose that the IPF: Societies can be usefully applied at both individual and organizational levels. Below we describe specific aspects of the IPF: Societies as well as its application.

Identity awareness is an awareness of aspects of one's own social and cultural identities and how those identities are situated within larger intersecting systems of power. Intercultural mindfulness is the “ability to understand cultural differences in ways that enable one to interact effectively with others from different racial, ethnic, or social identity groups in both domestic and international contexts” (Gillian-Daniel et al., 2021a). Collectively, “these domains encompass many features of intercultural humility, including: 1) awareness of one's own cultural backgrounds, including intersecting social identities; 2) recognizing one's biases and privileges in relation to self and others; 3) committing to learning about others' cultural backgrounds; and 4) addressing disparities in relational power by, in part, learning to recognize power differentials” (Gillian-Daniel et al., 2021a). The more aware one is of aspects of one's own social and cultural identities, the identities of others, and how those identities are situated within larger, intersecting systems of power, the more equitably mindful one can be of impacts, decisions, and programming driven by those identities.

Equity mindedness underpins building inclusive relationships. At both personal and organizational levels, willingness, capacity, and the communication skills to effectively engage those whose lived experiences may not match one's own is vital for examining mental models and advancing inclusive ProS DEI reform. At the boundary spanner level, inclusive relationships mean reflecting on whose voices are, and are not, centered and carry decision-making power when discussing important ProS policies, processes, and activities. From the STEM ProS perspective, building inclusive relationships could be reflected in collaborations with a range of organizations with intention to build mutual capacity. Inclusive relationships at the society level help shift social narratives and can inform sense making around information collected about the ProS, two examples of how mental models have critical impact on organizational systems (Kania et al., 2018).

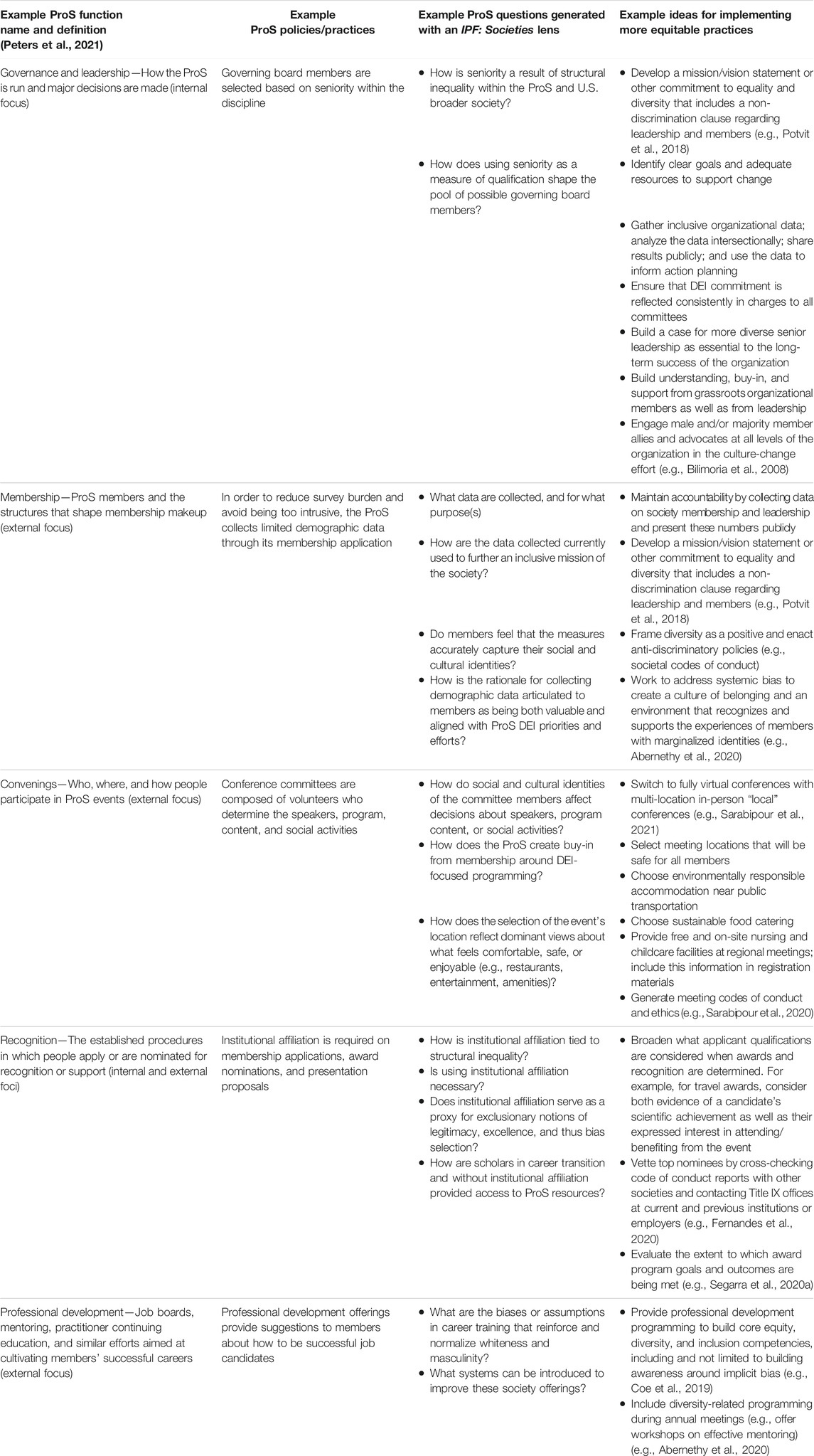

Influential actions are how boundary spanners and ProSs drive STEM system change. We propose that informed and diversely networked people serving as DEI boundary spanners will be motivated and held accountable for positive DEI change. Boundary spanners' actions can be focused on core ProS functions. Peters and others (2021) identified 11 functions of STEM ProSs for action focus. For explanatory purposes, we focus on a subset of five ProS functions identified by Peter et al. (2021) as depicted in the outer circles of Figure 1 and highlighted in Table 1. Ultimately, we propose that IPF: Societies-informed boundary spanners will engage in the influential actions associated with establishing new mental models and create accountability for nurturing the new diverse, equitable, and inclusive ProS look, feel, and actions.

TABLE 1. How the IPF: Societies informs practices within five example professional society functions.

Discussion

The IPF: Societies complements the use of other DEI organizational tools and increases both individual and organizational capacity to more efficiently and effectively identify and engage with DEI actions resulting from use of these tools. For example, we offer the Women in Engineering ProActive Network's (WEPAN's) Four Frames for Promoting Gender Equity Within Organizations (WEPAN, 2013). Originally adopted from Simmons University's Center for Gender in Organizations (1998), the four frames include: 1) equipping the individual, 2) creating equal opportunity, 3) valuing difference, and 4) revisioning culture. A STEM ProS DEI boundary spanner employing the IPF: Societies can evaluate and introduce more inclusive professional development programs (Frame 1); examine and recommend DEI changes to organizational structures, policies, and practices (Frame 2); call attention to ways in which ProS leaders and the organization are not “walking the DEI walk” (Frame 3); and identify and remedy incongruences between ProS existing practices and goals outlined in the ProS strategic plan (Frame 4). Similarly, from an organizational perspective, WEPAN's frames could be used to evaluate the equity of professional development programs and educational pathways (Frame 1); examine and revise organizational structures, policies, and practices to support greater DEI integration across all society functions (Frame 2); ensure that all leaders are, and continue to be, trained and coached on how to enact DEI-focused changes (Frame 3); and create opportunities to re-vision ProS culture and reflect that updated vision in the ProS mission and strategic plans (Frame 4).

As with WEPAN's four frames, the IPF: Societies complements the Equity Environmental Scanning Tool (EEST) (Peters et al., 2021). The EEST is a DEI self-assessment tool for ProSs adapted by ACCESS+ from The Royal Academy of Engineering and Science Council Diversity and Inclusion Progression Framework (2021). We propose that boundary spanners skilled in using the IPF: Societies will be more efficiently and effectively able to enact changes in areas identified by the EEST. Table 1 illustrates how the IPF: Societies can inform ProS DEI practices in relation to a subset (i.e., 5 of the original 11) of Peters et al. (2021) ProS's core functions, each of which have an internal focus (i.e., the STEM ProS business infrastructure) and/or an external focus (i.e., member and disciplinary serving STEM ProS infrastructure). We propose that taking an IPF: Societies lens to the policies and practices associated with each of these functions will help uncover and offer an opportunity to change previously implicit ProS mental models. We use questions to illustrate application of the IPF: Societies. In each core ProS function (column 1), existing policies or practices are presented that might appear reasonable to some (column 2), but when the IPF: Societies lens is applied (column 3), systemic and structural inequities affecting how the ProS engages with staff and members become more visible. We offer example ideas of equitable practices that could emerge from application of the IPF: Societies (column 4). This table shows how the ProS may not be making programming decisions with an understanding of structural issues (i.e., equity mindset), therefore missing out on the opportunity to address them and counter obstacles to DEI through inclusive relationships and influential actions.

When and where the IPF: Societies is brought into the ProS DEI change cycle will likely be dictated by the culture of the ProS and/or ProS leaders. Examples for how the IPF: Societies can be used and inform engagement is depicted in Table 2 below.

Conclusion

In sum, Identity awareness and Intercultural mindfulness create an equity mindset that supports inclusive relationships and influential actions. The four “I's” core to the IPF: Societies provide a framework for reflecting and acting on ProS culture at individual (e.g., STEM ProS DEI boundary spanner) and organizational levels. The IPF: Societies offers a way to guide change of mental models. ProS DEI boundary spanners employing the IPF: Societies can leverage their positionality and ability to straddle groups to affect cultural change across STEM ProSs, in combination with the efforts of other boundary spanners and in the disciplines in which they engage.

Of critical importance when working with mental models in ProSs is the expectation that there may be resistance to DEI initiatives, especially among members with majoritized identities who may be invested, even subconsciously, in maintaining existing power structures (Lipsitz, 2006). Because people occupy a constellation of identities of various positionings, awareness of common discourses rejecting DEI could help in ProSs navigating them (Bonilla-Silva, 2006). The IPF: Societies offers a framework to begin difficult discussions and offers a structured approach for working toward change. Of course, to be effective, the IPF: Societies requires sustained mobilization of its pieces, vis-à-vis making DEI concerns part of the fabric of ProSs.

Potential outcomes of wide-scale implementation of the IPF: Societies could be ProS actions in service of a more diverse, inclusive, and equitable STEM culture writ large. Resultant increased individual capacity to engage in the articulation and reframing of legacy mental models in turn guides organizational transformation and culture reform through broader systems change. As organizations engage in systemic change, greater ProS and STEM culture DEI changes can be made. Eventually, DEI change becomes less about individual efforts for specific DEI actions and more about broad, structurally patterned ProS organizational transformation and, ultimately, STEM culture reform.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

GML, DG-D, and RMcCG contributed to conception, design, and finalization of the paper. RC-M and HM contributed to drafts of the manuscript with special emphasis on social-science sections of the manuscript. SP had special focus on the IPF: Societies figure development. JWP and RC-M contributed to drafts of the manuscript with special emphasis on the sections associated with the ACCESS+ Equity Environmental Scanning Tool (EEST). VAS, AL-P, and ELS provided IPF model and figure refinement. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos (2017953, 1834518, 1834522, 1834510, 1834513, 1834526, and 1834521). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

GML is the director of ProActualize Consulting, LLC, a consulting business specializing in applying evidence-based strategies to promote inclusive organizational and disciplinary excellence.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abernethy, E. F., Arismendi, I., Boegehold, A. G., Colón-Gaud, C., Cover, M. R., Larson, E. I., et al. (2020). Diverse, Equitable, and Inclusive Scientific Societies: Progress and Opportunities in the Society for Freshwater Science. Freshw. Sci. 39 (3), 363–376. doi:10.1086/709129

Aldrich, H., and Herker, D. (1977). Boundary Spanning Roles and Organization Structure. Amr 2 (2), 217–230. doi:10.5465/amr.1977.4409044

Amplifying the Alliance to Catalyze Change for Equity in STEM Success (ACCESS+) (n.d.). Retrieved from https://accessplusstem.com/(Accessed September 22, 2021).

Ancona, D. G., and Caldwell, D. F. (1992). Bridging the Boundary: External Activity and Performance in Organizational Teams. Administrative Sci. Q. 37 (4), 634–665. doi:10.2307/2393475

Baillie, C., Kabo, J., and Reader, J. (2012). Heterotopia: Alternative Pathways to Social justice. Zero Books.

Bilimoria, D., Joy, S., and Liang, X. (2008). “Breaking Barriers and Creating Inclusiveness: Lessons of Organizational Transformation to advance Women Faculty in Academic Science and Engineering,”. Hum. Resour. Manage. 47, 423–441. doi:10.1002/hrm.20225

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2006). Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Brion, S., Chauvet, V., Chollet, B., and Mothe, C. (2012). Project Leaders as Boundary Spanners: Relational Antecedents and Performance Outcomes. Int. J. Project Manag. 30, 708–722. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2012.01.001

Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Harvard University Press.

Campbell-Montalvo, R. A., Caporale, N., McDowell, G. S., Idlebird, C., Wiens, K. M., Jackson, K. M., et al. (2020). Insights from the Inclusive Environments and Metrics in Biology Education and Research Network: Our Experience Organizing Inclusive Biology Education Research Events. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 21 (1), 1–9. doi:10.1128/jmbe.v21i1.2083

Campbell-Montalvo, R., Kersaint, G., Smith, C., Puccia, E., Sidorova, O., Cooke, H., et al. (in press). The Influence of Professional Engineering Organizations on Women and Underrepresented Minority Students' Fit. Front. Edu.

Campbell-Montalvo, R., Kersaint, G., Smith, C., Puccia, E., Skvoretz, J., Wao, H., et al. (2021). How Stereotypes and Relationships Influence Women and Underrepresented Minority Students' Fit in Engineering. J. Res. Sci. Teach., 1–37. doi:10.1002/tea.21740

Cech, E. A., and Rothwell, W. R. (2018). LGBTQ Inequality in Engineering Education. J. Eng. Educ. 107 (4), 583–610. doi:10.1002/jee.20239

Chaudhary, B., and Berhe, A. A. (2020). Ten Simple Rules for Building an Anti-racist Lab. Charlottesville, VA: Center for Open Science. doi:10.32942/osf.io/4a9p8

Coe, I. R., Wiley, R., and Bekker, L. G. (2019). Organisational Best Practices towards Gender equality in Science and Medicine. Lancet 393 (10171), 587–593. Available at:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014067361833188X. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33188-X

Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality's Definitional Dilemmas. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 41, 1–20. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, 139. Chicago: University of Chicago Legal Forum.

Dukes, A. A., Gillian-Daniel, D. L., Greenler, R. Mc. C., Parent, R. A., Bridgen, S., Esters, L. T., et al. (In press). “The Aspire Alliance Inclusive Professional Framework for Faculty—Implementing Inclusive and Holistic Professional Development that Transcends Multiple Faculty Roles,” in The Handbook of STEM Faculty Development. Editors S. Linder, C. Lee, and K. High (Charlotte, NC: American Society for Engineering Education).

Eisenhart, M. A., and Finkel, E. (1998). Women's Science: Learning and Succeeding from the Margins. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Etson, C., Block, K., Burton, M. D., Edwards, A., Flores, S., Fry, C., et al. (2021). Beyond Ticking Boxes: Holistic Assessment of Travel Award Programs Is Essential for Inclusivity. Charlottesville, VA: OSF Preprintsdoi:10.31219/osf.io/fsrpb

Faraj, S., and Yan, A. (2009). Boundary Work in Knowledge Teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 94 (3), 604–617. doi:10.1037/a0014367

Faulkner, W. (2007). ‘Nuts and Bolts and People’. Soc. Stud. Sci. 37 (3), 331–356. doi:10.1177/0306312706072175

Fernandes, A. M., Abeyta, A., Mahon, R. C., Martindale, R., Bergmann, K. D., Jackson, C. A., et al. (2020). “Enriching Lives within Sedimentary Geology”: Actionable Recommendations for Making SEPM a Diverse. Equitable and Inclusive Society for All Sedimentary Geologists. Pre-printAvailable at: https://eartharxiv.org/repository/object/90/download/170/.

Foor, C. E., Walden, S. E., and Trytten, D. A. (2007). "I Wish that I Belonged More in This Whole Engineering Group:" Achieving Individual Diversity. J. Eng. Edu. 96 (2), 103–115. doi:10.1002/j.2168-9830.2007.tb00921.x

Forrester, N. (2020). Diversity in Science: Next Steps for Research Group Leaders. Nature 585, S65–S67. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02681-y

Gillian-Daniel, D. L., Troxel, W. G., and Bridgen, S. (2021b). Promoting an Equity Mindset through the Inclusive Professional Framework for Faculty. The Department Chair 32 (2), 4–5. doi:10.1002/dch.30408

Gillian-Daniel, D. L., Greenler, R. M., McCBridgen, S. T., Bridgen, S. T., Dukes, A. A., and Hill, L. B. (2021a). Inclusion in the Classroom, Lab, and beyond: Transferable Skills via an Inclusive Professional Framework for Faculty. Change Mag. Higher Learn. 53 (5), 48–55. doi:10.1080/00091383.2021.1963158

Hacker, S. L. (1989). Pleasure, Power and Technology: Some Tales of Gender, Engineering, and the Cooperative Workplace. Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman.

Hacker, S. L. (1981). The Culture of Engineering: Woman, Workplace and Machine. Women's Stud. Int. Q. 4 (3), 341–353. doi:10.1016/s0148-0685(81)96559-3

Hill, L. B. (2020). Understanding the Impact of a Multi-Institutional STEM Reform Network through Key Boundary-Spanning Individuals. J. Higher Edu. 91 (3), 455–482. doi:10.1080/00221546.2019.1650581

Hughes, B. E. (2018). Erratum for the Research Article: "Coming Out in STEM: Factors Affecting Retention of Sexual Minority STEM Students" by B. E. Hughes. Sci. Adv. 4 (3), eaau2554. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao637310.1126/sciadv.aau2554

INCLUDES Aspire Alliance National Change(n.d). Inclusive Professional Framework for Societies. Available at: https://www.aspirealliance.org/national-change/inclusive-professional-framework/ipf-societies (Accessed on September 22, 2021)

K. A. Griffin, and S. D. Museus (Editors) (2011). Using Mixed-Methods to Study Intersectionality in Higher Education: New Directions in Institutional Research (Jossey-Bass).

Kania, J., and Kramer, M. (2011). Collective Impact. Stanford Soc. Innovation Rev. 9 (1), 36–41. Available at: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/collective_impact.

Kania, J., Kramer, M., and Senge, P. (2018). The Water of Systems Change. FSG. Available at: http://efc.issuelab.org/resources/30855/30855.pdf.

Katz, R., and Tushman, M. (1981). An Investigation into the Managerial Roles and Career Paths of Gatekeepers and Project Supervisors in a Major R & D Facility. R. D Manag. 11 (3), 103–110. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9310.1981.tb00458.x

K. Borman, R. Halperin, and W. Tyson (Editors) (2010). Becoming an Engineer in Public Universities: Pathways for Women and Minorities (New York, NY: Springer).

Leibnitz, G. M., Gillian-Daniel, D. L., and Hill, L. B. (2021). Networking Networks: Leveraging STEM Professional Society “Boundary Spanners” to Advance Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. NSF INCLUDES Rapid Community ReportsAvailable at: https://adobe.ly/3fPxjUs.

Lipsitz, G. (2006). The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How white People Profit from Identity Politics. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Lohan, M., and Faulkner, W. (2004). Masculinities and Technologies. Men and masculinities 6 (4), 319–329. doi:10.1177/1097184x03260956

McGee, E. O. (2020). Black, Brown, Bruised: How Racialized STEM Education Stifles Innovation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Metcalf, H. (2016). Broadening the Study of Participation in the Life Sciences: How Critical Theoretical and Mixed-Methodological Approaches Can Enhance Efforts to Broaden Participation. Lse 15 (3), rm3. doi:10.1187/cbe.16-01-0064

Metcalf, H., Russell, D., and Hill, C. (2018). Broadening the Science of Broadening Participation in STEM through Critical Mixed Methodologies and Intersectionality Frameworks. Am. Behav. Scientist 62 (5), 580–599. doi:10.1177/0002764218768872

Metcalf, H. (2017). Science Must Clean up its Act. Scientific American. Available at: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/voices/science-must-clean-up-its-act/.

National Academy of Sciences (2005). National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of MedicineFacilitating Interdisciplinary Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/11153

Page, S. (2007). The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Pawley, A., and Tonso, K. L. (2011). Monsters of Unnaturalness: Making Women Engineers' Identities via Newspapers and Magazines (1930-1970). J. Soc. Women Eng. 20, 50–75.

Peters, J., Campbell-Montalvo, R., Leibnitz, G., Metcalf, H., Lucy-Putwen, A., Gillian-Daniel, D., et al. (2021). Refining an Assessment Tool to Optimize Gender Equity in Professional STEM Societies. WCER Working Paper No. 2021-7 Available at: https://wcer.wisc.edu/docs/working-papers/WCER_Working_Paper_No_2021_7.pdf.

Potvin, D. A., Burdfield-Steel, E., Potvin, J. M., and Heap, S. M. (2018). Diversity Begets Diversity: A Global Perspective on Gender equality in Scientific Society Leadership. PloS one 13 (5), e0197280. Available at: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0197280. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0197280

Riley, D., Slaton, A. E., Pawley, A. L., Johri, A., and Olds, B. M. (2014). Social justice and Inclusion: Women and Minorities in Engineering. Cambridge handbook Eng. Educ. Res., 335–356.

Sarabipour, S., Khan, A., Seah, Y. F. S., Mwakilili, A. D., Mumoki, F. N., Sáez, P. J., et al. (2021). Changing Scientific Meetings for the Better. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 (3), 296–300. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-021-01067-y. doi:10.1038/s41562-021-01067-y

Sarabipour, S., Schwessinger, B., Mumoki, F. N., Mwakilili, A. D., Khan, A., Debat, H. J., et al. (2020). Evaluating Features of Scientific Conferences: A Call for Improvements. BioRxiv. Available at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2020/04/21/2020.04.02.022079.full.pdf.

Segarra, V. A., Primus, C., Unguez, G. A., Edwards, A., Etson, C., Flores, S. C., et al. (2020b). Scientific Societies Fostering Inclusivity through Speaker Diversity in Annual Meeting Programming: a Call to Action. Mol. Biol. Cel 31 (23), 2495–2501. doi:10.1091/mbc.E20-06-0381

Segarra, V. A., Vega, L. R., Primus, C., Etson, C., Guillory, A. N., Edwards, A., et al. (2020a). Scientific Societies Fostering Inclusive Scientific Environments through Travel Awards: Current Practices and Recommendations. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 19 (2), es3. doi:10.1187/cbe.19-11-0262

Skvoretz, J., Kersaint, G., Campbell-Montalvo, R., Ware, J. D., Smith, C. A. S., Puccia, E., et al. (2020). Pursuing an Engineering Major: Social Capital of Women and Underrepresented Minorities. Stud. Higher Edu. 45 (3), 592–607. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1609923

Smith, C. A. S., Wao, H., Kersaint, G., Campbell-Montalvo, R., Gray-Ray, P., Puccia, E., et al. (2021). Social Capital from Professional Engineering Organizations and the Persistence of Women and Underrepresented Minority Undergraduates. Front. Sociol. 6, 1–13. doi:10.3389/fsoc.2021.671856

The Royal Academy of Engineering and the Science Council (2021). Diversity Progression Framework 2.0 for Professional Bodies: A Framework for Planning and Assessing Progress. Retrieved from: https://sciencecouncil.org/professional-bodies/diversity-equality-and-inclusion/diversity-framework/ (Accessed on September 22, 2021).

Tonso, K. L. (1999). Engineering Gender− Gendering Engineering: A Cultural Model for Belonging. J. women minorities Sci. Eng. 5 (4), 365–405. doi:10.1615/jwomenminorscieneng.v5.i4.60

Tonso, K. L. (2014). Making Science Worthwhile: Still Seeking Critical, Not Cosmetic, Changes. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 9 (2), 365–368. doi:10.1007/s11422-012-9448-5

Tonso, K. L. (2007). On the Outskirts of Engineering: Learning Identity, Gender, and Power via Engineering Practice. Boston, MA: Brill.

Tonso, K. L. (1996). The Impact of Cultural Norms on Women*. J. Eng. Edu. 85 (3), 217–225. doi:10.1002/j.2168-9830.1996.tb00236.x

Tushman, M. L., and Scanlan, T. J. (1981). Boundary Spanning Individuals: Their Role in Information Transfer and Their Antecedents. Amj 24 (2), 289–305. doi:10.5465/255842

Warner, L. R., Settles, I. H., and Shields, S. A. (2016). Invited Reflection. Psychol. Women Q. 40 (2), 171–176. doi:10.1177/0361684316641384

Women in Engineering ProActive Network (WEPAN). (2013). Framework for Promoting Gender Equity in Organizations. Available at: https://www.wepan.org/general/custom.asp?page=FourFrames (Accessed September 22, 2021).

Keywords: inclusive professional framework for societies, mental models, intercultural mindfulness, equity mindset, inclusive relationships, identity awareness, influential actions, DEI (or Diversity Equity and Inclusion)

Citation: Leibnitz GM, Gillian-Daniel DL, Greenler RMcC, Campbell-Montalvo R, Metcalf H, Segarra VA, Peters JW, Patton S, Lucy-Putwen A and Sims EL (2022) The Inclusive Professional Framework for Societies: Changing Mental Models to Promote Diverse, Equitable, and Inclusive STEM Systems Change. Front. Sociol. 6:784399. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.784399

Received: 27 September 2021; Accepted: 14 December 2021;

Published: 18 February 2022.

Copyright © 2022 Leibnitz, Gillian-Daniel, Greenler, Campbell-Montalvo, Metcalf, Segarra, Peters, Patton, Lucy-Putwen and Sims. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gretalyn M. Leibnitz, Leibnitz.ACCESSplus@gmail.com

Gretalyn M. Leibnitz

Gretalyn M. Leibnitz Donald L. Gillian-Daniel

Donald L. Gillian-Daniel Robin M c C. Greenler

Robin M c C. Greenler Rebecca Campbell-Montalvo

Rebecca Campbell-Montalvo Heather Metcalf

Heather Metcalf Verónica A. Segarra

Verónica A. Segarra Jan W. Peters

Jan W. Peters Shannon Patton

Shannon Patton Andrea Lucy-Putwen

Andrea Lucy-Putwen Ershela L. Sims

Ershela L. Sims