- School of Digital Public Administration, Astana IT University, Astana, Kazakhstan

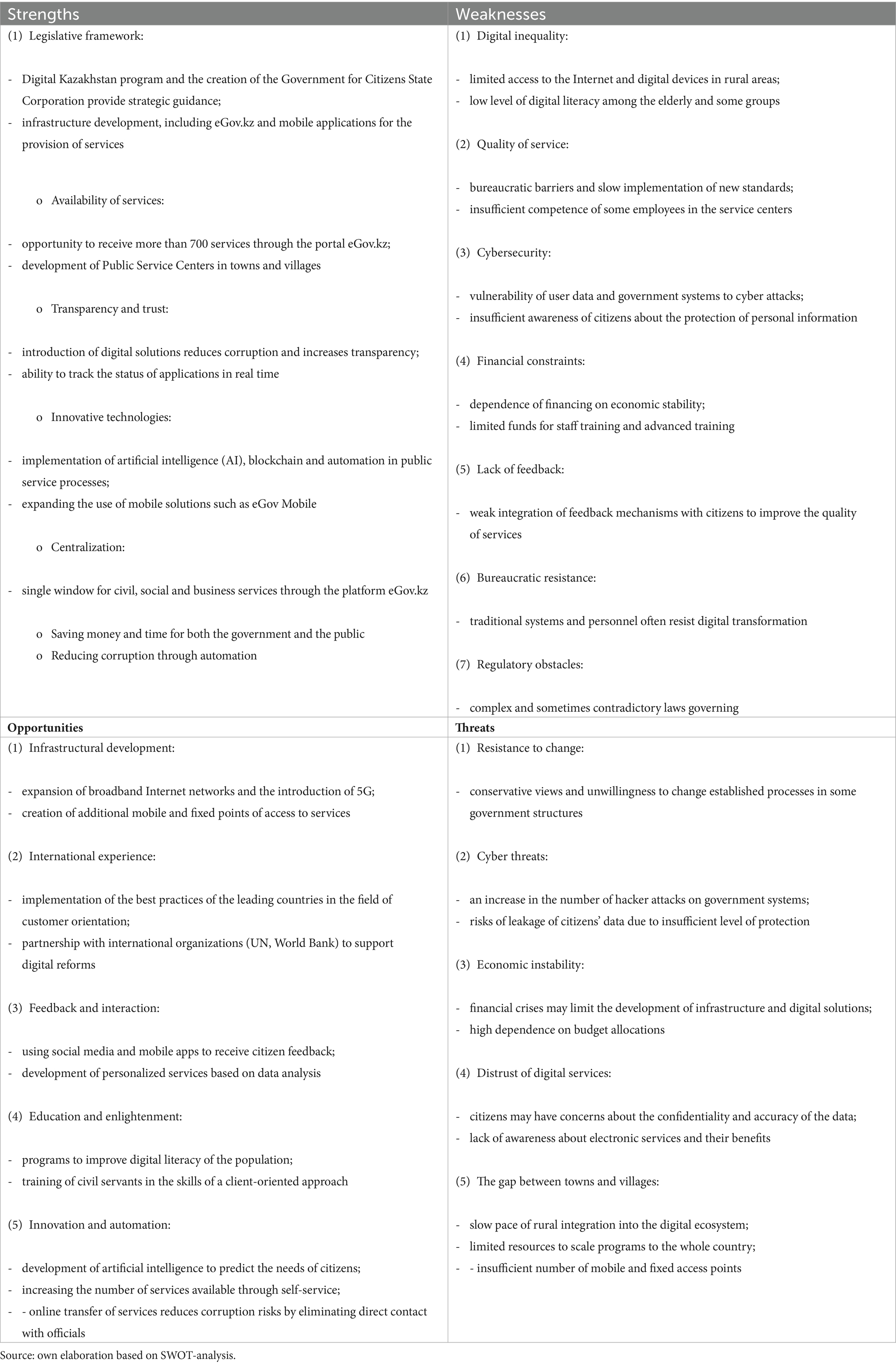

Digital transformation of public services is reshaping governance worldwide, yet evidence on citizen-centered outcomes in emerging economies remains limited. Kazakhstan’s ambition to adopt proactive, composite, and once-only service models presents an opportunity to evaluate how far institutional intent translates into improved citizen experience. We used a mixed-methods design combining (i) SWOT and PEST analyses of legal, institutional, and technological frameworks; (ii) an expert panel (n = 5 senior staff of the Agency for Civil Service Affairs, rating 7 items on a 0–5 scale); (iii) a large-scale national e-government survey of 27,336 authenticated respondents across all 20 regions (completion rate 97.1%); and (iv) international focus groups on AI in public services. Weighted percentages and Wilson 95% confidence intervals were calculated for citizen-reported problems; expert mean ratings summarized institutional factors. Experts rated enforcement capacity (mean 4.8/5) and statutory basis for once-only/composite/proactive services (4.6/5) highest among political factors, but identified weak international financial support (3.4/5) and cybersecurity posture (3.8/5) as persistent gaps. Citizen survey data show technical errors (23.3, 95% CI 22.8–23.8), redundant bureaucracy (15.2%, 14.8–15.7), and staff capability gaps (14.5%, 14.0–14.9) as the leading obstacles. Urban respondents were overrepresented (98.4% vs. 1.6% rural), highlighting a digital inclusion gap. Focus groups found that 70.8% of international participants reported some use of AI in public services but noted uneven environmental safeguards. Kazakhstan has built a robust legal and institutional infrastructure for digital public services, yet legacy registers, digital divides, and data-protection gaps constrain performance. Codifying once-only, composite, and proactive services as mandatory principles, investing in data stewardship and cybersecurity, and treating inclusive digital literacy as public infrastructure are critical next steps. These findings offer a model for other emerging economies seeking to balance innovation with equity and accountability.

1 Introduction

The global context in which development efforts unfold today is radically different from even a decade ago. A world characterized by Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity, and Digital (VUCA-D) is compounded by an environment that is increasingly Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, and Incomprehensible (BANI). In such a landscape, traditional approaches to development and governance no longer suffice. What is needed is resilient, adaptive, and inclusive innovation, and digital technologies are uniquely positioned to provide that.

Recognizing this critical inflection point, the International Telecommunication Union and the United Nations Development Programme have launched the Digital Development Acceleration Programme. This strategic initiative aims to use digital transformation as a catalyst for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a globally agreed-upon blueprint for peace, prosperity, and planetary health by 2030. Digital technologies are not only enablers of efficiency but also stabilizers in turbulent times. According to experts, these tools can accelerate progress toward at least 70% of the 169 SDG targets. In the face of VUCA-D challenges like economic volatility and geopolitical disruption, digital platforms offer agility and scalability. Meanwhile, the BANI reality, where public anxiety and societal fragility are growing, calls for transparent, secure, and ethical digital ecosystems that foster trust and coherence (United Nations, 2015; World Bank, 2016; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2016).

Kazakhstan’s trajectory intersects directly with SDG 16 (effective, accountable institutions), SDG 9 (resilient infrastructure and innovation), and SDG 10 (reducing inequalities). Concretely, the reform levers administrative simplification, regulatory coherence, and algorithmic accountability, translate into SDG 16 gains by strengthening legality, transparency, and public trust in service delivery. Proactive and composite services (e.g., life-event bundles for birth, starting a business, relocation, or social protection) reduce discretion and processing times while expanding redress channels, thereby improving integrity and citizen satisfaction. The once-only data-sharing principle, underpinned by secure interoperable registries and auditable consent, cuts compliance costs and error rates, enabling real-time eligibility checks and “tell-us-once” experiences that close loopholes and enhance accountability. Inclusive access measures, omni-channel portals, mobile-first design, assisted digital points, multilingual interfaces, and open data, further institutionalize the “Citizens First” ethos by ensuring rules are applied consistently and decisions are explainable, measurable, and contestable.

Advancing SDG 9, the program links resilient digital infrastructure (nationwide secure connectivity, government cloud and data centers, cybersecurity operations, and API-based interoperability rails) with an innovation policy stack (regulatory sandboxes, public procurement of innovation, GovTech challenges, and open standards). This pairing increases system uptime and security while crowding in private solutions to public problems. Proactive and composite services generate predictable demand signals for local SMEs, while once-only data flows and reliable digital identity, payment rails reduce transaction frictions, conditions under which innovative firms can scale.

For SDG 10, inclusive access is the decisive bridge from digital ambition to equitable outcomes. Infrastructure investments are targeted to shrink urban–rural gaps (last-mile broadband, community Wi-Fi, shared facilities), while affordability measures (social tariffs, device support for low-income households, zero-rated public services) and capabilities programs (digital literacy for women, older persons, youth, and persons with disabilities) broaden effective use. Proactive entitlement checks, powered by once-only data, help surface “missing beneficiaries” and reduce take-up barriers for cash and in-kind programs (United Nations, 2015).

Together, these levers form a coherent, measurable pathway: SDG 16 is strengthened through transparent, rules-based digital administration, SDG 9 is accelerated by secure, interoperable infrastructure that lowers innovation costs, and SDG 10 is advanced by ensuring access, affordability, and capability so that the returns to digital transformation are broadly and shared. This mapping provides a policy-relevant lens for the recommendations that follow accountability.

While recognizing the enormous potential of digital technologies to promote sustainable development, it is important to consider the risks involved. From large-scale cyber threats to the ethical dilemmas associated with artificial intelligence (AI), these challenges require a holistic approach. Thus, developing reliable, ethical and inclusive digital solutions is vital. Of particular concern is the growing inequality in access to technological resources. Today, 85% of all global digital patents are registered in just five countries, indicating an excessive concentration of innovation power (Aldoseri et al., 2024). This threatens to widen the global divide and hinder equal participation in the digital future. Ensuring that digital innovation benefits everyone rather than reinforcing the privileges of a few requires governments, international organizations, the private sector and civil society to work together.

Despite impressive global progress, digital development remains uneven, both between and within countries. This is deepening many digital divides across regions, genders, age groups and social groups. The urban–rural divide also remains significant, with rural areas facing a lack of infrastructure, slow internet speeds and limited access to digital services. The digital space increasingly reflects and sometimes reinforces existing offline inequalities.

Against this backdrop, Kazakhstan’s digital governance strategy stands out as a forward-looking model. As part of its ambition to join the 30 most developed countries, Kazakhstan has embedded digital transformation into its governance and public service delivery architecture. Kazakhstan faces the ambitious task to build of a new model of public administration, where the interests of citizens who consume services are considered (“Citizens First” principle), and the qualitative improvement of public service delivery processes is the main priority of public administration reform. The current state of the civil service system of the Republic of Kazakhstan is characterized by the desire to comply with the principles of a listening, open, pragmatic and respectful state. Thus, in the Strategy “Kazakhstan-2050: A New political course of the established state” and the Concept of the development of the public administration system until 2030, the principle of “Citizens first” is noted as one of the fundamentally important aspects of the further development of the republic for the coming decades. Currently, government agencies are pursuing a targeted policy to digitalize the services provided, considering increased customer orientation.

The purpose of the study is to analyze the key stages of the formation of the public services delivery system and identify the main directions for improving the customer-oriented approach in the context of the digital transformation of the state apparatus.

1.1 Research questions

Building on Digital-Era Governance (DEG), the New Public Service (NPS), and co-production theory, we articulate three overarching research questions:

RQ1 (theoretical lenses): Which progressive theoretical approaches and institutional models enable the full implementation of a citizen-centered approach to public service delivery under conditions of rapid digitalization?

RQ2 (system assessment): What is the current level of development of Kazakhstan’s public-service system, specifically its legal, institutional, technological, and citizen-experience dimensions, and what unresolved issues persist?

RQ3 (mechanisms and equity): to what extent do proactive, composite, and once-only service models, supported by digital infrastructure, improve speed, simplicity, and perceived fairness, particularly across territorial, demographic, and educational divides?

1.2 Hypotheses

Derived from DEG, NPS, and international evidence, we specify four testable hypotheses:

H1: Experts will rate the political and technological dimensions of Kazakhstan’s digital public-service reforms as having higher impact on customer orientation than the economic or social dimensions (PEST analysis).

H2: Citizens residing in urban areas, with higher education levels, and higher digital literacy will report fewer obstacles (e.g., bureaucratic procedures, unclear algorithms, low integration) than rural, less educated, or digitally disadvantaged groups (citizen survey).

H3: The prevalence of proactive, composite, and once-only service models will correlate positively with citizen perceptions of speed, simplicity, and fairness in service delivery (triangulated from expert SWOT/PEST and citizen survey data).

H4: Trust, privacy, and cybersecurity concerns will moderate citizens’ willingness to adopt digital channels, such that higher concern predicts greater reliance on assisted or in-person channels, even when digital options are available.

1.3 Empirical strategy

These questions and hypotheses guide the mixed-methods design described in sections 2.1–2.2. SWOT and PEST frameworks operationalize institutional and expert judgments (H1); the large-scale egov.kz survey operationalizes citizen experience (H2–H4); and focus-group data with international experts situate Kazakhstan’s trajectory globally (RQ1–RQ3). By specifying hypotheses, we can test whether institutional intent (laws, platforms, proactive/composite design) translates into improved citizen outcomes and more equitable access.

To achieve this goal, the paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 includes material and methodology. Section 3 presents results of data analysis, including existing literature on digital transformation with special attention to public services delivery system, as well as the empirical results. Section 4 discusses the main outcomes, potential implications and concludes the research with several practical recommendations and suggesting areas for future research.

The practical applicability of the results and recommendations obtained during the projects for government agencies, which will contribute to solving urgent issues of socio-economic development of Kazakhstan and Central Asia.

2 Research methods

2.1 Research design

The main approaches to conducting research assume the complexity and consistency of the analytical tools used. The set of qualitative methods includes retrospective, SWOT and PEST analysis of Kazakhstani practice, as well as focus-group research with international experts and the survey of Kazakhstani citizens. While achieving the set goal and implementing the research objectives, the following research questions will be answered:

What progressive theoretical approaches exist today for the full implementation of a customer-oriented approach in the provision of public services to the citizens?

What is the current level of development of the public services system in Kazakhstan? What are the unresolved issues?

The methodology combines interdisciplinary, analytical, and systematic approaches. Methods included desk research; review of materials from international organizations; analysis of Kazakhstan’s legal documents; expert focus-group data; and development of a strategic-analysis-based framework to assess public administration effectiveness.

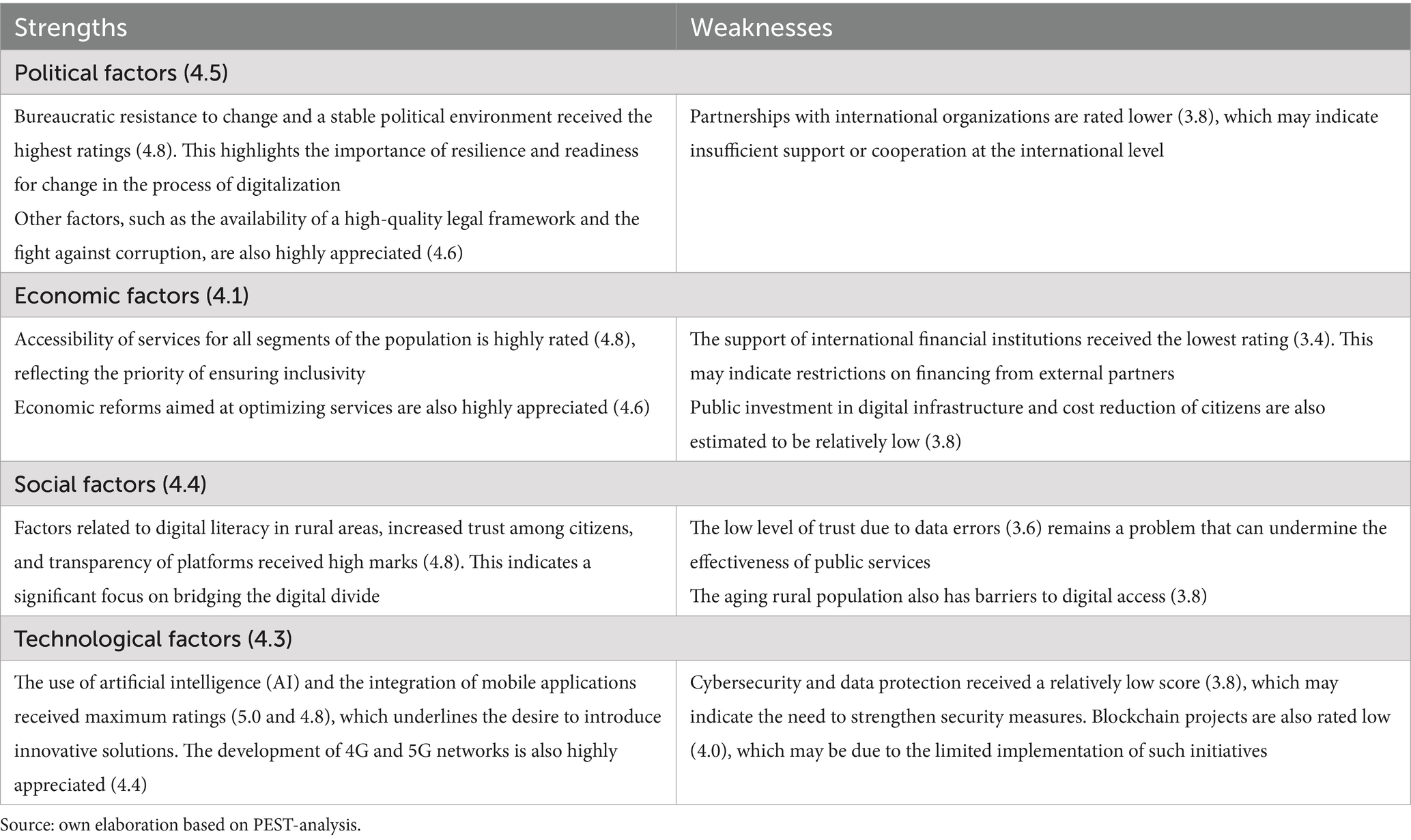

Firstly, the SWOT analysis considers the main positive and negative aspects of public services delivery system and digitalization. Secondly, the PEST analysis further discusses different influences of the following factors: political, economic, social and technological factors. The impact of each factor is assessed by experts on a scale from 1 to 5:

1 -Low impact. This factor has minimal impact on customer orientation.

2 -Weak influence. This factor has some influence, but it is insignificant.

3 -Average impact. This factor has a noticeable impact, but not a critical one.

4 -High impact. This factor has a significant impact on customer orientation.

5 -Very high influence. This factor has a strong and significant influence.

0 -Does not affect. This factor has no effect.

For the purposes of the study, the experts are identified as employees of the authorized body in the field of public service, whose competence includes issues related to monitoring and evaluating the quality of public services, as well as issues related to the de-bureaucratization of the state apparatus. We surveyed experts from the Agency for Civil Service Affairs (n = 5; units for service quality and de-bureaucratization). Items rated on a 0–5 impact scale with the mean number. Experts were eligible if they (i) were current staff of the Agency for Civil Service Affairs of Kazakhstan; (ii) had responsibilities in public-service quality monitoring and/or de-bureaucratization; and (iii) had more than 2 years professional experience in these functions. Although centrally based, experts had oversight of services across all regions. We operatively implemented PEST into 7 items. Each item was rated on a 0–5 impact scale (0 = no effect; 1 = low; 2 = weak; 3 = average; 4 = high; 5 = very high). Items were defined with one-sentence descriptors to standardize interpretation. The survey was self-completed electronically after a short briefing.

Thirdly, a focus group study was conducted with practitioners from the public sector, academic community and researchers from countries of Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America (ministries, regulatory agencies, research and academic organizations, private companies). Participants in the focus group study were asked to answer 6 questions aimed at analyzing and studying country aspects of the implementation of artificial intelligence in the public sector, such as “How would you rate the current stage of AI implementation in public services in your country?,” “In which areas do you think AI should be used in the public sector?,” “How does your country’s framework address the environmental consequences of digital transformation in public service?,” etc.

Finally, the study involves a survey of 27,336 respondents, conducted on the Kazakhstani e-government platform (egov.kz) from September to October 2024:

1. Sampling frame and eligibility. The platform covers all 20 regions of Kazakhstan and requires authenticated login via National Digital ID, so the sampling frame comprised verified adult users (≥18 years) of egov.kz who accessed any of the main service categories during the fieldwork window. Respondents were eligible if they (i) were residents of Kazakhstan, (ii) had logged into egov.kz at least once in the previous 12 months, and (iii) consented to participate after reading the electronic information sheet;

2. Recruitment pathway and completion rate. An invitation banner rotated on the egov.kz home page and inside the “My Services” dashboard; it appeared at most once per user session to minimize fatigue. Of ~42,000 eligible authenticated users shown the banner, 29,520 clicked through, 28,152 began the questionnaire, and 27,336 completed it (completion rate 97.1% of starters; 64.9% of invitees). Because the instrument was short (median completion time 4.8 min) and mobile-friendly, item nonresponse was low (≤5% per question);

3. Duplicate and bot filtering. Each submission was tied to a single egov.kz user ID; back-end logs automatically restricted multiple submissions. CAPTCHA and device fingerprinting were applied to prevent bot activity. Suspicious sessions (unrealistic completion times <1 min or >5 standard deviations from the median) were flagged and excluded before analysis (<0.5% of records);

4. Questionnaire wording, length, and languages. The instrument contained 12 closed-ended and 2 open-ended questions covering (i) satisfaction with service timeliness and ease, (ii) obstacles encountered (technical errors, bureaucracy, unclear algorithms, staff competence, etc.), and (iii) demographic variables (region, settlement type, sex, age, education, employment, household vulnerability).

Of the 27,336 respondents, 54.13% are men. In terms of age categories, the largest group is aged 30 to 45, accounting for 51.79% of the sample. Among the 20 regions of the country, respondents from major cities such as Almaty (14.67%) and Astana (12.12%) make up a significant share of the sample. This may indicate a higher level of citizen involvement in the process of receiving public services and greater awareness. This assumption is further supported by the fact that most respondents (98.43%) live in cities, while only 1.57% reside in villages. Regarding socio-economic status, more than 47% of respondents report being at a satisfactory level. This suggests that a significant portion of the population is experiencing financial difficulties and may require state support, underscoring the need for targeted social and economic policy interventions.

2.2 Ethics and consent

This study was reviewed and approved by the Research ethics committee of the Center for Analytical Research and Evaluation under Supreme Audit Chamber of the Republic of Kazakhstan (conclusion of the Committee July 15, 2024 on approval of the research program of a scientific project). The approved research program covers both the expert focus-group component and the 2024 citizen survey delivered via the national e-government platform (egov.kz). All participants were 18 years or older. Participation was voluntary, with the right to decline any question or withdraw at any time without consequence.

Electronic informed consent was obtained from each participant of focus group before recording and discussion began. No identifying details are published, and quotations are reported in coded, non-identifying form. National citizen survey (egov.kz) was presented to authenticated users with a consent screen outlining the study purpose, voluntary nature, expected duration, absence of direct benefits or risks beyond daily life, confidentiality measures, and contact information for questions/concerns. Proceeding beyond the consent screen constituted affirmative informed consent. The instrument did not collect direct identifiers (e.g., names, phone numbers); demographic and location fields were limited to non-precise categories. No monetary incentives were offered to survey and focus group participants. The survey was administered on the national e-government platform (egov.kz) with informed consent, and all records were anonymized. Focus group transcripts contain potentially identifying narratives and cannot be shared publicly. All procedures followed institutional policy and the Law “On Personal Data and their Protection.”

3 Results

3.1 Theoretical framework: digital-era governance and the new public service

Public service delivery systems have undergone significant changes over the past few decades. Early approaches focused on bureaucratic service delivery models, which often led to inefficiency and delays. The concept of bureaucracy proposed by Weber (1922) as a rational and legal form of organization emphasized strict hierarchical structures and standardized procedures, but was criticized for its rigidity (Weber, 1922). Scientists Hood (1991), Osborne and Gaebler (1992) advocated a more results-oriented, decentralized, and market-based approach to public administration (New Public Management, NPM).

In the early 2000s, a New Public Governance (NPG) emerged that focused on collaboration, networking, and citizen engagement in the service delivery process. The NPG focuses on public services, such as partnerships between government and citizens, in which the public actively participates in the creation, provision and evaluation of services. One of the most significant shifts in the provision of public services has been the transition to citizen-oriented services.

According to Linders (2012), citizen participation is crucial for improving public service delivery outcomes, as it leads to faster, more personalized, and more efficient service delivery (Linders, 2012). The theory of joint production of Ostrom (1996) suggests that citizens should actively participate in the creation and provision of public services, rather than being passive recipients (Ostrom, 1996). At the same time, scientist Behn (2001) emphasized efficiency management within the framework of a model focused on the interests of citizens, noting that efficiency indicators should correspond to citizens’ satisfaction and results, and not just efficiency (Behn, 2001).

The role of technology in improving the provision of public services has become a central topic in literature in recent decades. The advent of e-government has fundamentally changed the service delivery system using digital platforms that make services more accessible, efficient, and transparent. Gil-Garcia and Pardo (2005) conducted an in-depth analysis of e-government, noting that technology can significantly reduce transaction costs, increase transparency, and expand accessibility (Gil-Garcia and Pardo, 2005).

In turn, Heeks (2007) argued that while e-government initiatives promise improved service delivery, there are challenges in terms of access, inclusivity, and digital literacy, especially in developing countries. As governments have begun to realize the potential of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), the focus has shifted to using technology to improve service delivery and citizen engagement (e-government 2.0).

Mergel (2013) emphasized the growing role of social networks and online interaction tools in the field of public services, which provide citizens with the opportunity to communicate with government agencies in real time and receive feedback. Recent studies on public services delivery focus on digital transformation. Thus, Trischler and Westman Trischler (2021) introduce the definition “design for experience” as an approach to public service design in the age of digitalization. Other research (Krøtel, 2019; Di Giulio and Vecchi, 2023; Haug et al., 2023; Mergel et al., 2023) discuss the issue of digitally induced change. Special attention was given to implementation of AI in public administrations.

Recent work stresses that “digital government transformation” (DGT) is an umbrella term that spans technological change, organizational and cultural shifts, and new forms of communication and service delivery (Eom and Lee, 2022; David et al., 2023; Sanina et al., 2024). In the Sustainability 2024 bibliometric study, DGT is discussed variously as a complex process, a primarily technological change, an organizational change, a socio-cultural transformation, and as communication change to meet citizen expectations; related keywords include open data, big data, AI, IoT, data management, and digitized government services. The authors also find that despite intuitive linkages to sustainable development, the explicit DGT–SDG nexus remains underexplored and comparatively marginal in public administration journals (Sanina et al., 2024).

Wilson and Mergel (2022) study U. S. “digital champions” individuals who advocate ideas, technologies, and strategies to overcome DGT barriers, and ask what barriers they experience and which strategies they deploy. Using an integrated deductive, inductive analysis of interviews, they model how champions navigate structural and cultural barriers and reveal underexamined dynamics in that interplay. This maps a strategy space for advancing tools and processes inside government and clarifies how champions conceptualize relationships between cultural or structural constraints and overcoming tactics.

Besides this, Güler and Büyüközkan (2023) situates DGT within adjacent domains—e-procurement, open government data, public value, adoption models, accessibility, and citizen-centric portal design, illustrating the field’s diffusion across management, planning, policy, and information systems journals and the growing attention to evaluation, accessibility, and inclusion in digital services.

The ecosystem approach as a unified principle of public services delivery based on digitization was analyzed by Andersson et al. (2022), as well as by Idzi and Gomes (2022), as well as Yukhno (2024). Based on systematic literature reviews, these researchers provide perspectives on public governance in the Digital Era. The unified state digital ecosystem is centered on big data, AI, and data analysis with citizen-centric approach in mind.

The conceptual framework of value creation in public service logic based on supply chain management and digitization was studied by Trischler et al. (2023), Virtanen and Jalonen (2023), Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek and Szymczak (2023). This approach could increase the efficiency and quality of public service implementation processes.

Digital-Era Governance (DEG) argues for reintegration of government functions, needs-based holism, and deep digitization to replace siloed, paper-centric workflows (Dunleavy and Tinkler, 2005). In our context, DEG motivates joined-up service models (e.g., proactive, composite, and extraterritorial services) and once-only data exchange between registers to reduce burden and error. In parallel, co-production theory treats citizens as partners who help define problems, co-design services, and co-deliver outcomes (Ostrom, 1996; Bovaird, 2007; Voorberg et al., 2014). It underpins our emphasis on participatory feedback loops, user testing, and assisted channels for groups facing digital or geographic barriers. Moreover, the New Public Service (NPS) reframes the role of public servants from steering to serving, prioritizing democratic values: equity, accountability, and trust, over narrow efficiency (Denhardt and Denhardt, 2000, 2015). NPS aligns our analysis with rights-based access, fail-safe procedures and inclusive design so that digital reforms expand, not restrict access.

Fail-safe procedures are a no-refusal-for-formality rule with (i) right to cure missing/expired documents within a defined period; (ii) ex officio data retrieval from state registers (once-only principle); (iii) silence-is-consent for low-risk services after statutory time limits; and (iv) duty to assist and escalate. This shifts burden off applicants and increases equity. In Kazakhstan’s system, across PSCs, the eGov portal, and sectoral ministries, fail-safe procedures would be set in law to keep applications moving despite routine defects. Authorities may not reject cases for curable issues or for data already held by the state. Applicants get a defined cure window (e.g., 10–20 working days) and officials have a duty to assist (explain gaps, provide templates, and, where lawful, retrieve data). Agencies must seek information ex officio from authenticated registers (once-only). Processing is risk-based: low-risk services can be provisionally issued with post-checks; higher-risk require verification first, per ministerial rules. Statutory deadlines stand where lawful, silence-is-consent may apply, otherwise written delay reasons are required. All uses are logged and audited; appeal rights and proportionate sanctions apply. Data access is necessary, proportionate, and logged; high-risk services need a privacy impact assessment. In practice: PSC clerks issue deficiency notices and trigger register queries; eGov flags gaps, captures consent, queues cures, and sends SMS/email updates; back-office risk engines govern provisional issuance; oversight bodies audit logs for legality, equal treatment, and privacy compliance.

Composite services bundle multiple, legally distinct services around a single life event, such as birth, school enrollment, or starting a business, so that one application triggers a coordinated sequence (for example: birth certificate—child benefit—clinic registration). By orchestrating steps across agencies, composites cut repeat data entry, lower transaction costs, and make handoffs transparent. Proactive services, by contrast, are initiated by the state without a citizen application. Using register events or eligibility rules, the administration can offer pre-filled benefits or updates when income, address, or family status changes. The two models are complementary: composite design reorganizes how people apply, while proactive design reduces the need to apply at all.

International experience shows the range of tools available. Estonia applies a strong once-only principle and life-event bundles through secure register interoperability and ex officio checks, supported by assisted completion and legal duties to retrieve data centrally. Singapore’s LifeSG streamlines childbirth and schooling with life-event composites and adds proactive nudges when eligibility is detected. The United Kingdom’s “Tell Us Once” illustrates a composite-proactive hybrid for bereavement, where a single notification propagates across agencies. At the EU level, the Single Digital Gateway and once-only initiatives promote cross-border data exchange and document reuse, embedding no-wrong-door access and ex officio verification for selected procedures.

For Kazakhstan, aligning fail-safe procedures with composite and proactive models ensures legal rights, no wrongful refusal, a right to cure, and a duty to assist, are matched by technical capabilities such as register interoperability, full logging, and risk-based verification. The result is fewer Type-I denials (eligible users rejected for fixable reasons), faster delivery, and better equity for rural, older, or low-literacy users, while preserving due-process and privacy safeguards.

Overall, we integrate these lenses into our empirical strategy as follows: (i) service models (proactive, composite, extraterritorial) operationalize DEG’s holism; (ii) participation & feedback mechanisms instantiate co-production; and (iii) equity and accessibility metrics (rural access, digital literacy, disability accommodations) express NPS values. This blended framework guides our interpretation of SWOT and PEST diagnostics and the citizen survey, ensuring that policy recommendations target not only efficiency gains but also legality, inclusiveness and trust are core to sustainable digital transformation.

3.2 Kazakhstani e-governance: retrospective overview

The development of the public service delivery system in sovereign and independent Kazakhstan is inextricably linked to the history of the formation and modernization of the public administration system. Conventionally, the reform of public administration is divided into three stages.

The first stage (from 1997 to 2002) was marked by the implementation of administrative and budgetary reform, in which the basic foundations of public sector management were built and the transition to a new budget system was implemented, which laid the foundation for the introduction of program-oriented management methods and the formation of the institution of public administration.

The second stage (from 2003 to 2006) is characterized by reforms in the division of powers and decentralization of power. The result of this area of reform was the optimization of the central state apparatus, during which an internal reorganization of ministries and their departments was carried out.

The third stage (starting in 2007) was marked by a large-scale reform of the public administration system.

The postulates put forward for the further development of the national public administration system are reflected in the Plan of Priority Measures for the Modernization of the Public Administration System adopted in 2007, where, as one of the designated priorities, the President highlighted the direct focus of government agencies on providing high-quality services to the population. This period was marked by a significant “step forward” toward building an effective public service delivery system in Kazakhstan (Bokayev et al., 2024; Ibadildin et al., 2025).

In Kazakhstan, the concept of “public service” was first introduced in 2007 by the Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Administrative Procedures.” At the same time, this definition remained generalized and did not allow for a clear distinction between the concepts of “public service” and “public function.” Later, the concept of “public service,” which was improved taking into account the norms of the resolution of the Constitutional Council of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On the official interpretation of Article 54, sub-paragraphs (1) and (3) of paragraph 3 of Article 61, as well as a number of other norms of the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan on the organization of public administration,” although it allowed to overcome some inaccuracies of previous editions, fill in existing gaps and to reflect more fully the essence of the meaning of public services, at the same time left unresolved a number of questions, the answers to which will be partially given later, with the entry into force of the Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Public Services.”

At the same time, the legislative support in force at that time (certain norms were provided for by the laws of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Administrative Procedures,” “On Regulatory Legal Acts,” the Budget Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan) in this area made it possible to begin work on identifying public services and then including them in the Register of Public Services, to orient the activities of responsible government agencies—the responsibility of service providers to comply with the standards and regulations of public services. Moreover, for the first time, the provision of public services through the Public Service Center (PSC) and the e-government portal was launched (Iskendirova et al., 2025; Amirova et al., 2025).

The definition of a public service was given in paragraph 1 of Article 34 of the Budget Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan: “A public service is recognized as the activity of government agencies, their subordinate organizations and other individuals and legal entities, which is one of the forms of implementation of certain functions of government agencies, provided for by the legislation of the Republic of Kazakhstan, aimed at meeting the needs of individuals and legal entities (with the exception of government agencies), having an individual character and carried out at the request of individuals and (or) legal entities (with the exception of government agencies).”

Further, a regulatory framework was laid to improve the quality of public services, including the approval of the Register of Public Services, standards and regulations for public services included in this register. Kazakhstan has become one of the first post-Soviet countries to create an e-government web portal. Since 2012, the E-Licensing portal has been put into operation.

At the same time, to further develop the public administration system, since 2010, an assessment of the effectiveness of government agencies, including the provision of public services, including the electronic form of their provision, has been introduced. The results of the annual assessment have significantly improved the public administration system by improving the quality and accessibility of public services. In particular, in accordance with the instructions of the Head of State, given based on the results of the assessment of the effectiveness of government agencies in 2011, the Law “On Public Services| was developed and approved in April that year. This Law is a fundamental document in the field of public services. The Law establishes the inalienable right of a citizen to receive public services without any discrimination.

For the first time, the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan approved the Register of Public Services on June 30, 2007. Initially, the Registry included 132 public services. Currently, the Registry contains 1,359 public services (including subspecies), of which 1,255 are electronic (93%) and 104 are paper based. Seven hundred and thirty-eight services are provided on an alternative basis (55%), 111 composite services, and 1,281 (95%) through the State Corporation.

Thus, over the past 17 years, the number of public services in the Registry has increased by more than 10 times. Of note is the inclusion of healthcare services in 2010, and services for issuing licenses and other permits in 2012, which significantly expanded the “space” for standardization.

The stages of formation of the public services sector in the context of digitalization:

1. The stage of the origin and creation of infrastructure (before the 2000s). Creation of primary conditions for modernization and automation of public services.

2. The beginning of the formation of e-government (2004–2010). The development of a legal framework and the creation of platforms for the provision of public services in electronic form (eGov.kz, Law “On Personal Data and their Protection,” the Law “On Public Services”).

3. Development and expansion of digital services (2010–2015). Mass introduction of electronic public services and creation of infrastructure for their provision (Public service centers, implementation of the “Single window” system for business registration and receiving social benefits).

4. The Digital Kazakhstan Program and the integration of innovations (2016–2020). Improving the quality and accessibility of public services using advanced technologies (eGov Mobile, artificial intelligence, blockchain, big data, electronic queue systems).

5. Integration with international standards and improvement (2021-present). Support for the sustainable development of digital public services and the implementation of international practices (chatbots, voice assistants, online consultations, availability of public services in rural and remote areas through mobile applications and online platforms).

Kazakhstan’s legal and institutional framework already contains several elements conducive to proactive, composite, and once-only service models. Article 34 of the Budget Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan (adopted 4 December 2008, No. 95-IV) defines “public service” as an activity of state bodies provided on the basis of law to meet citizens’ needs, while Article 5(3) of the Law “On Public Services” No. 377-IV dated 15 April 2011 (as amended) obliges state bodies to obtain necessary data from official information systems without re-requesting it from applicants (Budget Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2025; Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On State Services”, 2013). This provision underpins the “once-only” principle and is reinforced by Government Decree No. 535 dated 30 June 2007 “On Approval of the Register of Public Services,” which structures service delivery and allows the inclusion of composite bundles.

The Administrative Procedures Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan No. 219-VI dated 29 June 2020 (entered into force 1 July 2021) further codifies “fail-safe” administration. Article 25 establishes the duty of administrative bodies to assist applicants; Article 26 grants applicants the right to cure deficiencies within a defined time frame; and Article 27 imposes statutory time limits on decisions, allowing silence-is-consent for low-risk services where provided. Together these articles create a clear legal platform for right-to-cure, duty-to-assist, and predictable decision timelines (Administrative Procedures Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2020).

Composite and proactive services also have emerging statutory and programmatic bases. Government Decree No. 827 dated 12 December 2017 approved the State Program “Digital Kazakhstan,” which launched proactive service delivery pilots such as automatic birth benefit registration. Amendments to the Law “On Public Services” (2019–2020 revisions) added references to proactive service delivery, allowing administrative bodies to pre-fill applications or initiate services when eligibility is detected. However, these provisions remain scattered across subordinate acts and pilot programs, limiting their enforceability.

Kazakhstan’s Law “On Personal Data and Their Protection” No. 94-V dated 21 May 2013 (as amended) supplies the privacy and accountability framework for ex officio data retrieval, requiring consent, secure processing, and audit trails. In practice, these safeguards must be fully integrated into once-only and proactive models to ensure public trust (Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Personal Data and Their Protection”, 2013).

Taken together, these statutes provide a legal foundation but not yet a unified statutory obligation for once-only, proactive, and composite services. Codifying these models as mandatory design principles in the Law “On Public Services” and the Administrative Procedures Code would reduce inter-agency transaction costs, clarify duties to share and protect data, and insulate reforms from electoral cycles. Drawing on international best practices such as the EU Single Digital Gateway Regulation (EU) 2018/1724 and Estonia’s “Once Only” principle, Kazakhstan could achieve the next stage of digital-era governance while safeguarding rights to privacy and due process.

Recent cautionary evidence highlights “digi-service bubble” risks, rapid front-end digitisation without commensurate back-end coordination, leading to fragility and inequities (Saputra et al., 2025). Kazakhstan’s successive reform waves, administrative consolidation and service standardization, the roll-out of Public Service Centers, and the subsequent turn to digital-by-default, established the legal and institutional premises for integrated, user-centered delivery. The empirical analysis that follows examines how far these premises translate into citizen-experienced outcomes. Specifically, we operationalize the reform logic through measures of proactive, composite, and extraterritorial services; once-only data exchange; and safeguards for inclusion and trust. Using a national survey and expert SWOT and PEST diagnostics, we test whether institutional intent has yielded improvements in speed, simplicity, equity, and perceived reliability, and we identify the capability and data-governance constraints that continue to condition performance. This bridges from institutional design to observed performance structures the analysis that follows.

3.3 SWOT and PEST analysis

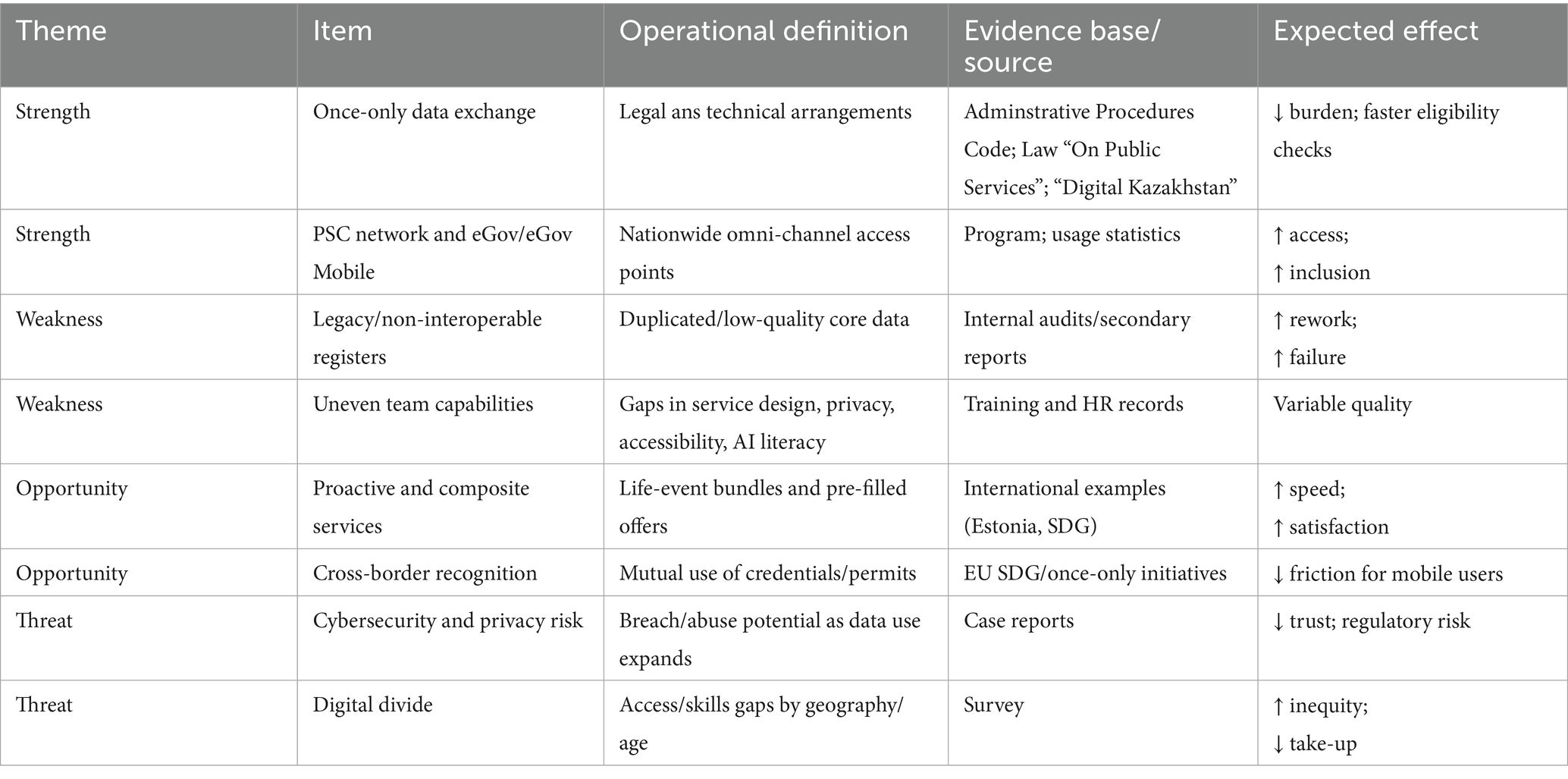

SWOT and PEST analysis methods are used for in-depth retrospective analysis, study of strategic documents and current legislation of the Republic of Kazakhstan on the provision of public services and digitalization (Tables 1, 2).

The SWOT analysis showed that the system of public services in Kazakhstan is undergoing significant changes, focusing on digitalization, convenience and transparency. Despite the existing challenges, the country is making steady progress in improving the quality and accessibility of services. In the coming years, an increased focus on innovation, inclusivity and data protection is expected, which will allow Kazakhstan to strengthen its position as a leader in digital transformation in the Central Asian region (Table 2).

In this regard, it is necessary to additionally conduct a PEST analysis that will assess the political, economic, social and technological factors affecting the legislative framework and initiatives of Kazakhstan in the field of public services and e-government. The aim of PEST analysis is to determine which political, economic, social and technological factors influence customer orientation in the provision of public services.

Through a retrospective analysis and study of the legislative framework, the following political, economic, social and technological factors have been identified that influence customer orientation in the provision of public services. An expert survey was conducted to assess the impact of each of these factors on the customer orientation of the provision of public services using digitalization. Based on the analysis of the data obtained, expert estimates and average values are given for each factor, as well as strengths and weaknesses (Table 3).

The SWOT and PEST tables provide a valuable descriptive account of Kazakhstan’s digital government landscape, yet their analytical contribution is realized only when they are explicitly connected to a coherent reform program (Table 4).

The analyses indicate four cross-cutting themes: (i) an enabling central mandate and a growing portfolio of digital assets (Strengths/Political); (ii) structural weaknesses in data governance, legacy processes, and uneven capabilities (Weaknesses/Technological); (iii) opportunities for scale through standards, cross-sector collaboration, and cross-border service design (Opportunities/Political-Technological); and (iv) persistent threats rooted in cybersecurity risk, variable public trust, and the rural/age digital divide (Threats/Social-Technological). These themes motivate six integrated recommendations discussed below.

1. Institutional Strengths and the Architecture of Reform. The combination of a strong central mandate and maturing e-government platforms provides a foundation to consolidate the system architecture of service delivery (Strengths/Political). The analysis supports the legal codification of once-only data exchange and of composite and proactive services as core design principles, rather than discretionary practices. Establishing statutory and secondary regulatory bases for these models would reduce inter-agency transaction costs, clarify duties to share and protect data, and insulate reforms from electoral cycles. In the short term (0–12 months), drafting amendments and issuing implementing rules would be feasible; medium-term horizons (12–24 months) should focus on phased roll-out across high-volume services. Appropriate stewardship would rest with the Ministry of Justice and the Digital Ministry, with monitoring through indicators such as the proportion of transactions using pre-filled data and the number of services operating under an explicit once-only legal basis.

2. Remedying Structural Weaknesses. The tables point to legacy registers, data duplication, and uneven process quality as major barriers to scale (Weaknesses/Technological). These constraints justify a national data governance program comprising a distributed network of chief data stewards, a master data management approach, and Application Programming Interface (API)-based interoperability aligned with open standards. Short-term work should design stewardship roles and governance boards; medium-term efforts should prioritize remediation backlogs for critical registers; long-term attention should institutionalize continuous quality assurance. Progress may be tracked by duplicate-record rates, API uptime, and the percentage of critical registers with formally appointed stewards.

A second weakness concerns uneven organizational capabilities. Here diagnostics imply the need to institutionalize capacity-building for service teams, including competencies in service design, privacy and security, accessibility, data stewardship, and AI literacy. Rather than ad hoc training, the evidence supports a career-long learning architecture (e.g., an academy with modular credentials), communities of practice, and Human Resource (HR) incentives that link advancement to demonstrated competencies. Short-term pilots can be launched immediately; alignment of promotion criteria and the diffusion of communities of practice are realistic medium-term targets. Indicators include certification rates by role, the number of services redesigned per quarter, and pass rates on privacy/accessibility audits.

1. Opportunities for Scaling Public Value. On the opportunity side, the diagnostics highlight the strategic value of standards adoption and cross-border collaboration (Opportunities/Political–Technological). Standardization (interoperability profiles, accessibility norms, assurance processes for algorithmic systems) lowers coordination costs and increases reuse of components. In parallel, cross-border pilots in domains with high citizen mobility (e.g., education credentials, business registration) can demonstrate the feasibility and value of extraterritorial service models. Such pilots should be pursued in the medium term and institutionalized thereafter, with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and sector ministries as co-owners. Evaluation should consider transaction time and cost savings, user satisfaction, and the number of services achieving mutual recognition.

2. Threats to Trust, Security, and Inclusion. The PEST analysis underscores significant threats related to cybersecurity and privacy, and the SWOT highlights trust sensitivities among user segments (Threats/Social–Technological). These findings justify a privacy-by-design and cybersecurity uplift that includes data protection impact assessments for high-risk services, independent audits, red-teaming exercises, and public-facing transparency notes on data flows. Short-term action should establish baseline controls, with medium-term goals of third-party certification and regular resilience testing.

Equally, the social dimension of diagnostics points to persistent digital exclusion affecting rural residents and older users. The analysis supports the treatment of inclusive digital literacy as public infrastructure rather than a temporary compensatory program. This entails co-designed curricula in Kazakh and Russian, accessible formats, delivery through PSCs and mobile units, and partnerships with schools, libraries, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and employers. Crucially, assisted-digital channels at PSCs should be maintained as a permanent complement to online channels. Monitoring should include course completion rates, pre/post task-success measures, reductions in the rural–urban success gap, and satisfaction among users aged 60 + .

1. Closing the Loop: Feedback, Learning, and Accountability. A recurring diagnostic weakness concerns slow or uneven learning from user feedback. To address this, feedback should be embedded directly into service flows (eGov, mobile, and PSC counters), consolidated in a central platform with text analytics and rigorous safeguards, and linked to service backlogs with explicit service-level agreements. Public dashboards and “You said, we did” notes can increase accountability and, over time, rebuild trust. In the short term, a central platform and Service Level Agreements (SLA) are achievable; integration with procurement and backlog management should follow in the medium term. Suitable indicators include median time-to-fix, fix rates within SLA, and reductions in repeat complaints by category.

2. Sequencing and Governance Logic. The diagnostics also inform the order of operations. The legal and data-governance foundations (codification and stewardship) must precede the full scaling of proactive and composite services; otherwise, weaknesses in data quality and accountability would propagate as reforms scale. Similarly, capacity-building is not an adjunct but a precondition for sustainable delivery, while inclusive literacy and assisted channels are necessary to mitigate the distributional risks highlighted by the social and technological threat vectors. A pragmatic sequence consistent with the evidence would therefore be: Foundation (0–12 months): legal drafting, data governance design, academy pilots, and feedback platform establishment; Scale (12–36 months): legal roll-out, register remediation and APIs, expansion of literacy programs, and integration of feedback with service backlogs and procurement, alongside initial cross-border pilots; Sustain (36 + months): mature privacy/cyber regimes, continuous improvement cycles, annual curriculum refreshes, and production-grade cross-border services. Governance should mirror this sequence. Each priority service requires a clearly identified senior owner (“owner of last resort”), with cross-cutting stewardship functions (data protection, cybersecurity, accessibility) organized as federated networks capable of auditing, advising, and enforcing standards. Budgeting should earmark a fixed proportion of program funds for capacity and feedback operations, thereby aligning incentives with the learning orientation implied by the diagnostics.

In this regard, the Agency for Civil Service Affairs is working on 17 transformational approaches, through the prism of which public services should be provided: extraterritoriality, proactivity, compositeness, minimization of deadlines and documents, exclusion of reference services, incomplete/half-hearted services, alternative/non-alternative provision of services, commissions, approvals, urgent/indefinite services, paid/free services, checks/rechecks in the provision of services, centralization/decentralization of services, conflicts in regulatory legal acts, the hearing procedure. In addition, it is necessary to legislate the following ways of providing public services: (i) composite method is the provision of a public service involving a combination of several services provided on the basis of a single application; (ii) proactive method is the provision of public services aimed at anticipating the provision of services based on the needs of citizens; (iii) extraterritorial method is provided.

The SWOT and PEST analysis enables high-ambition reforms. We prioritize legal codification of proactive and composite models and once-only data exchange. Economic constraints argue for phased investment: stabilize core platforms and identity; expand rural broadband and PSC staffing; embed AI assurance and cybersecurity. Social findings (digital divide, elder usability, trust) motivate targeted literacy programs, assisted channels, and service proxies with strong safeguards. Technological factors (AI potential vs. data protection gaps) call for secure data governance, model transparency, and failure-resilient architectures.

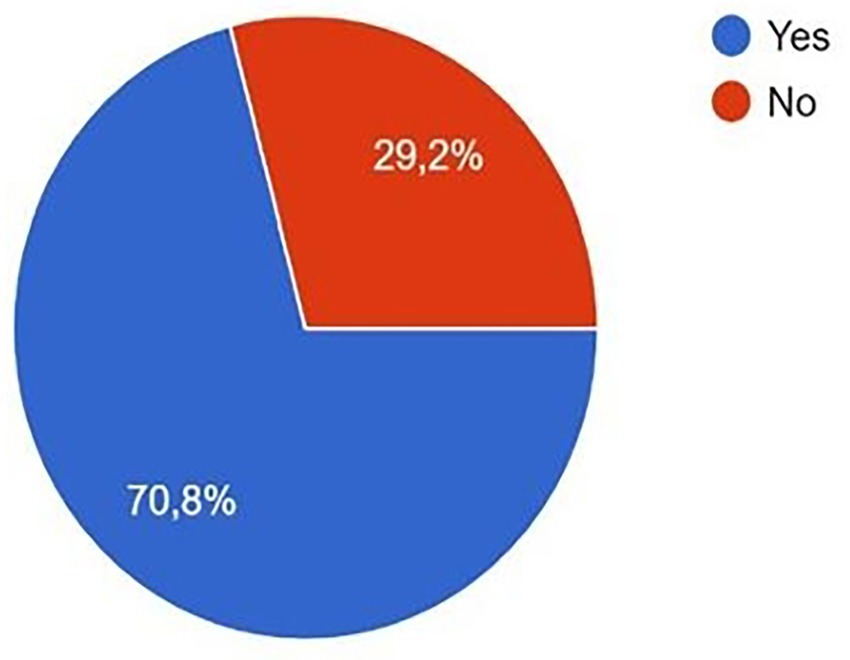

3.4 International experts’ perspective

According to experts, only 1/3 of the participating countries currently do not use artificial intelligence in the public sector (Figure 1). The survey indicates that public-sector adoption of AI is already common but not yet universal. A clear majority of respondents (70.8%) report some use of AI in government, while 29.2% report no use. This pattern suggests that many administrations have moved beyond aspiration to hands-on experimentation, typically through pilots or niche deployments, yet have not achieved system-wide integration. The stage of adoption implied here places a premium on the “plumbing” of trustworthy AI: data stewardship, model assurance, and privacy and security reviews that enable scaling across agencies. Concentration in early sectoral stages suggests governance capacity is the binding constraint; reforms should prioritize model assurance, data quality, and procurement competence before scaling.

According to the data presented, half of the respondents (50%) believe that the implementation of artificial intelligence in the civil service system is at an early stage of application in certain sectors, which indicates limited and selective use. About 41.6% of participants assess the situation as an initial stage, namely discussion or initial implementation. Only 8.3% of respondents indicated that artificial intelligence is actively used in various industries. At the same time, none of the experts chose level 5, which indicates the absence of large-scale institutional implementation with legislative support.

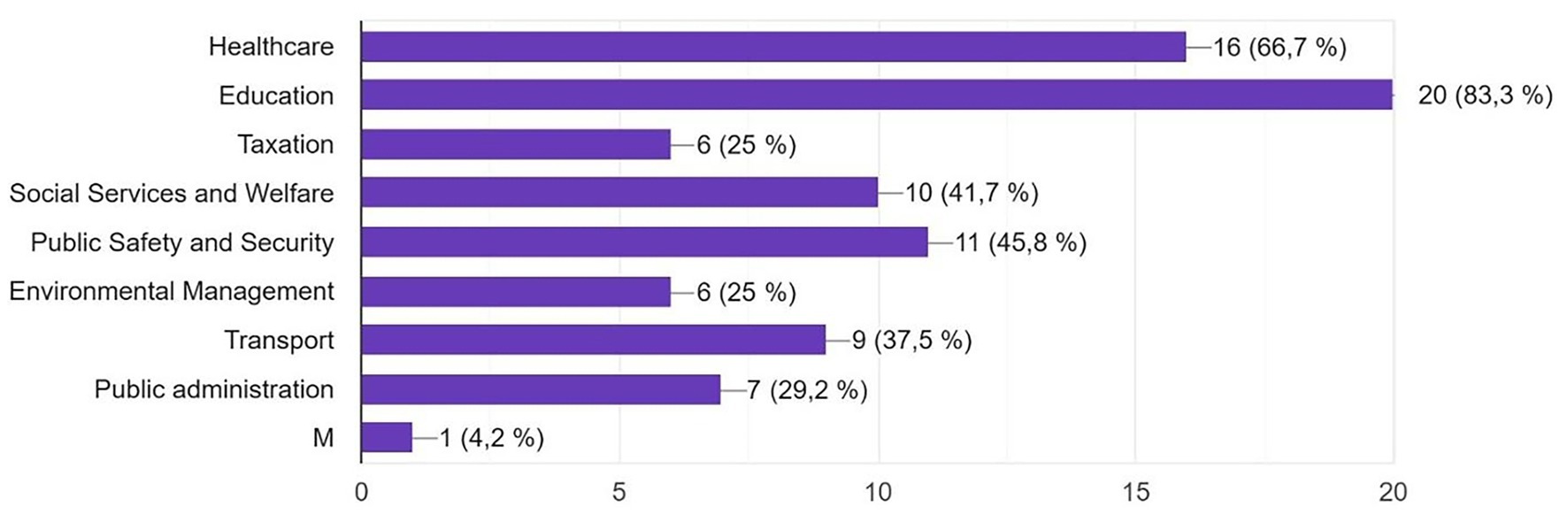

To the next question, “In what areas do you think artificial intelligence should be used in the public sector?” (Figure 2). Education/healthcare dominance aligns with public value and scale; sequencing pilots here maximizes social return while building ethical guardrails.

Focus group participants believe that artificial intelligence (AI) can significantly improve the quality of educational services (83.3%). AI is also considered a priority as a tool for improving diagnostics, treatment and increasing efficiency (66.7%). In addition, AI is associated with opportunities in the field of crime prevention, video surveillance and emergency response (45.8%). A similarly close value (41.7%) can also be associated with the ability of AI to improve the provision of social services, predict needs and optimize work with vulnerable groups of the population. About 1/3 of the votes are also provided in the designation of the increasing role of AI in the development of smart transport systems, logistics and autonomous transport (37.5%), as well as in increasing the efficiency of administrative processes, automating document flow and assisting in decision-making (29.2%). Taxation and environmental management are noted as areas where AI can help in fraud detection, sustainability analysis and risk forecasting (25%). Thus, education and healthcare are the leaders in priority, which indicates high trust in AI in these areas. At the same time, the sectors “Security, social security and transport” also stand out as important areas. The diversity of answers indicates the wide potential for the use of AI in public administration.

The following responses were received to the next question: “How does your country’s system (e.g., laws, strategies, action plans) address the environmental impacts of the digital transformation of the civil service?” (Figure 3).

Each segment of the diagram represents a specific environmental measure or public policy element related to digital transformation. Environmental safeguards within digital-government programs appear uneven. The most reported actions focus on end-of-life management, hardware recycling (33.3%) and “responsible disposal” policies (25%). Smaller shares mention trade-in schemes, public monitoring of ICT energy consumption, or fully system-wide approaches; a minority report no measures at all. This profile suggests governments are prioritizing downstream e-waste handling while under-investing in upstream efficiency and transparency. A fuller “green-digital” policy stack would couple datacenter energy and water KPIs (including for vendors) with procurement standards for repairability and energy performance, lifecycle asset management and device-sharing, carbon-aware workload placement, and public dashboards on ICT energy use.

Overall, many countries, according to the participants, lack a systemic or comprehensive approach to environmental issues in the context of digital transformation. Only a fifth of respondents reported a comprehensive public policy, indicating the need to develop integrated solutions. The immediate policy implication is to pair expansion with assurance, setting outcome metrics for priority sectors (e.g., learning gains, wait-time reductions, case-resolution speed) and institute robust governance (impact assessments, monitoring, and recourse). At the same time, environmental commitments should shift from “recycle only” to lifecycle-wide accountability. These findings are based on a modest expert sample and reflect self-reported conditions; they are therefore best read as directional evidence to guide sequencing and capability-building rather than as precise national estimates.

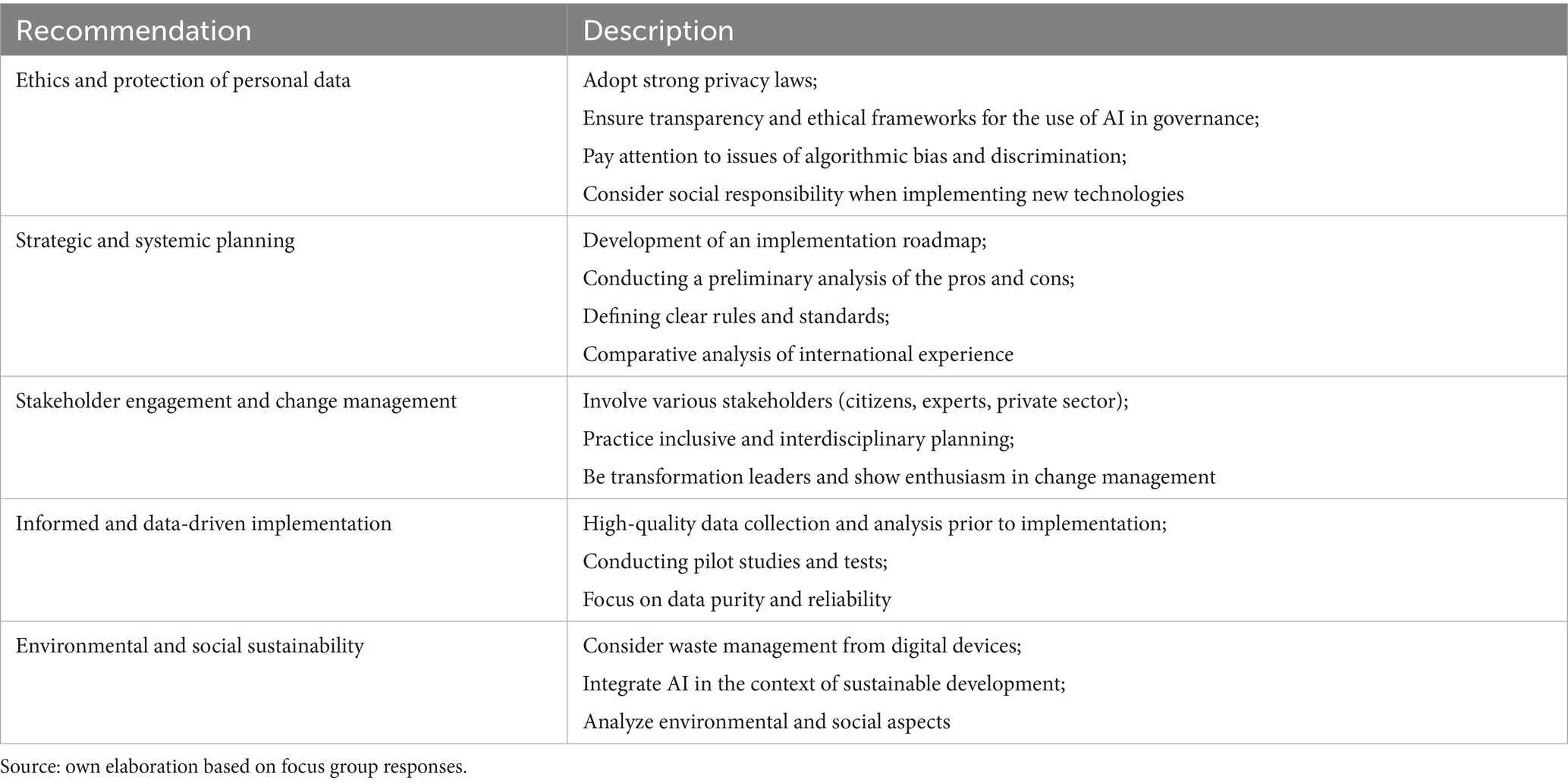

To the final question, “What advice would you give to managers considering expanding the use of artificial intelligence in public service?” Various suggestions were received from respondents, covering aspects of ethical use of personal data, transformation management, strategic planning and analysis. The key findings are the following suggestions (Table 5).

In summary, respondents’ recommendations cover five priority areas: ethical principles and data protection; strategic systems planning; stakeholder engagement; evidence-based implementation; sustainable and environmentally responsible development. These proposals form a holistic understanding of how to develop AI in the public sector so that it is effective, ethical, and focused on the needs of society.

3.5 Citizens’ perspective

3.5.1 Overall assessment

The survey results show that digitalization has had a significant impact on the quality of public services. The most frequently mentioned result of digitalization was the acceleration of public service delivery times, as indicated by 41.44% of respondents. This suggests that the transition to digital platforms reduces waiting times and improves access to services. Simplification of procedures, increased awareness and quality of services also received considerable attention. For example, 16.61% of respondents noted that digitalization has optimized the procedures for providing public services, and 10.17% emphasized the increased awareness of service recipients about the procedure for receiving services. These aspects indicate that digitalization not only makes services more accessible but also promotes more effective interaction between government agencies and citizens.

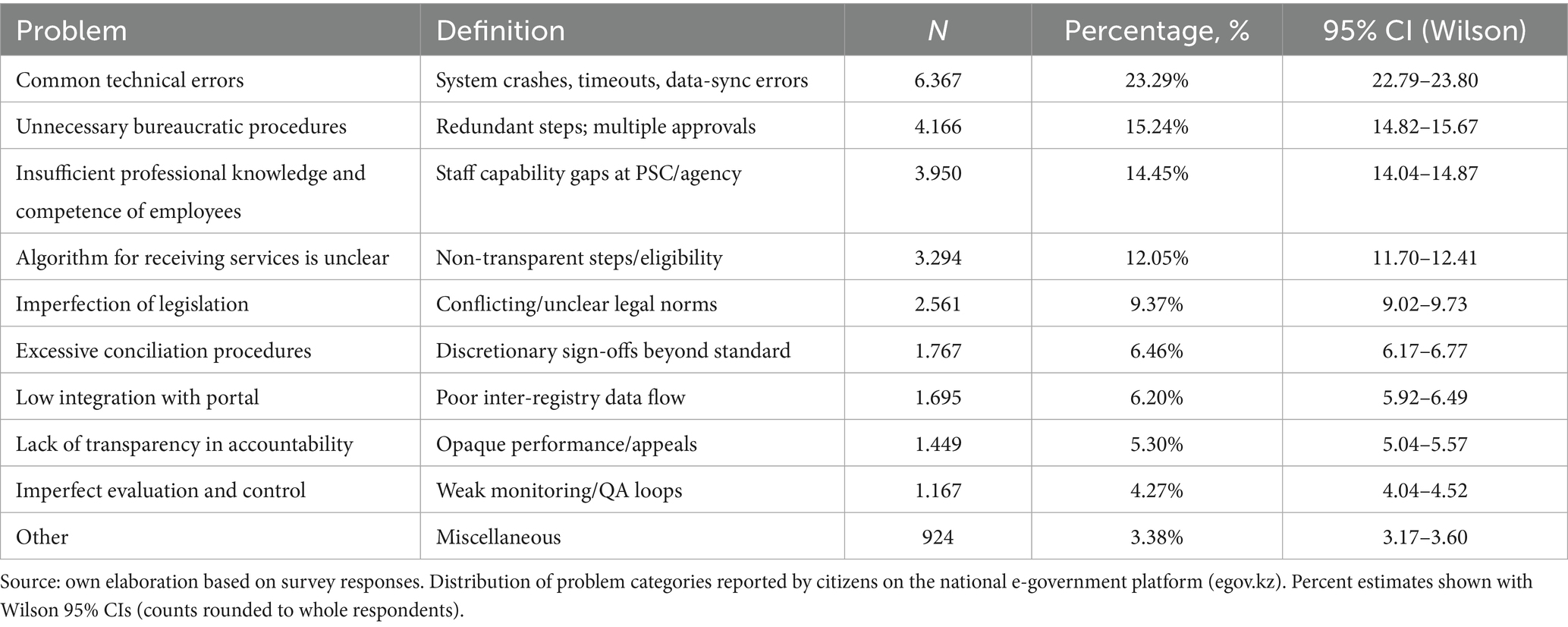

The results of the survey of respondents show that there are many problems, and each of them requires attention. The main problems were identified in the following categories: bureaucracy, lack of qualification of employees, shortcomings in the system, and technical errors (Table 6).

Table 6. Citizen-reported problems in obtaining public services (National Survey, Sep–Oct 2024; n = 27,336).

One of the most pressing issues, according to respondents, is excessive bureaucracy. This item received 15.24% of votes and indicates that many citizens are faced with the need to go through multiple approval stages before receiving the required service. Excessive bureaucracy can significantly slow down the process of providing services, which negatively affects the level of satisfaction of citizens. Excessive approval procedures, noted by 6.46% of respondents, also play a significant role in slowing down the process. Often, these procedures are not only time-consuming, but also lead to confusion and misunderstanding, which further aggravates the situation.

The most significant problem, according to the survey results, was frequent technical errors, which received 23.29% of the votes. Technical failures can occur for various reasons: from outdated software to a lack of resources to maintain systems in working order.

Such errors can greatly undermine citizens’ trust in public services. If citizens encounter problems receiving services, this can lead to an increase in the number of complaints and dissatisfaction. Solving this problem requires both a technical and organizational approach. It is necessary to invest in updating equipment and software, as well as training employees to promptly resolve technical problems.

Thus, the survey results showed that there are many problems in the provision of public services, including excessive bureaucracy, lack of employee qualifications, unclear algorithms for receiving services, opaque accountability system, imperfect legislation, low level of integration of information systems and frequent technical errors. All these problems require a comprehensive approach to solving and constant monitoring.

3.5.2 Segmented results

The analysis is based on the survey summaries with breakdowns by region, sex, ethnicity, age, settlement type, purchasing power, employment status, family category, and education. To highlight the most meaningful differences within each slice, we calculated the range of shares (max–min, in percentage points) for identical answer options across segments of the same question (Figure 4). This makes it possible to rank items by the “strength of segmentation” and avoid overemphasizing minor gaps. The survey covers all regions with the largest subsamples in Almaty city and Astana city.

Regional differences. The regional profile shows the largest, and intuitive, contrasts linked to settlement type and the structure of employment. The share of residents of regional capitals and cities of republican significance is highest in Astana (81%) and lowest in Almaty region (17%). Conversely, the share of rural settlements peaks in Almaty Region (53%) and bottoms out in Astana (2%). The share selecting “manufacturing and industrial sector” is notably higher in Ulytau (41%) and lower in Turkistan Region (10%). Occupation: “employee of a private company”: highest in Almaty city (41%), lowest in Turkistan Region (13%). These differences point to a familiar polarization of “capital and industrial” versus “agrarian and peripheral” territories, critical for targeting public services and employment programs.

Sex differences primarily concern employment and attitudes toward the modality of public service delivery. For the “manufacturingand industrial sector,” men mark it more often (25%) than women (10%). On several options regarding a transition to single-channel (non-alternative) provision of public services, we observe opposite sex shifts of 10–15%: in one option, men agree more often (47% vs. 33% for women), whereas for an alternative option it is women who agree more often (57% vs. 46% for men). Work experience (more than 20 years) is more common among men (36%) than women (24%). The share “employee of a private company” is higher among men (36%) than women (24%). Men are more represented in industrial segments and private employment. This aligns with greater tenure and partially explains differences in preferences regarding service delivery formats.

The most noticeable gaps concern attitudes to the service-delivery format and educational profile. For individual options on single-channel public service provision, ranges reach 18% (e.g., 47% among “Kazakh” vs. 29% among “other” for one option; and a reverse tilt of 62% vs. 44% for a different option). Differences in educational attainment reach 15% (e.g., 48% vs. 33% for a given category). Ethnocultural factors matter for explaining variability in attitudes to public services and educational status.

Settlement type, purchasing power, employment. Settlement type understandably aligns with place of residence and some social attitudes. In the employment slice, contrasts are pronounced: the share with “no work experience” is much higher among the unemployed (22%) than the employed (5%); “working in a private company” is, conversely, more common among the employed (47%) and less so among the unemployed (32%). Purchasing power (as a proxy for economic status) correlates with labor-market inclusion and educational profile.

Educational status is among the strongest differentiators. For several indicators, ranges reach 30% and above between the extremes of educational attainment (e.g., 64% vs. 13% on a given item). Higher education is associated with greater long tenure (difference 21% for “more thab 20 years”) and with more urban residence.

The survey reveals a small set of powerful cleavages that consistently organize attitudes and socioeconomic outcomes: territory (urban–rural/industrial–agrarian), education, and household vulnerability. These factors explain far more variation than age alone and, in many questions, more than sex or ethnicity.

4 Discussion

The public service system in Kazakhstan is undergoing an active transformation aimed at improving quality, accessibility and transparency. The main directions of development include the introduction of digital technologies, improvement of infrastructure, improvement of legislation and the introduction of a customer-oriented approach. Taking this into account and the analysis carried out, it can be concluded that for the research question (RQ1) “What progressive theoretical approaches exist today for the full implementation of a customer-oriented approach in the provision of public services to the citizens?”:

1. Our empirical findings reveal a dual narrative: on the one hand, Kazakhstan has built a comprehensive legislative and institutional infrastructure for digital public services; on the other hand, persistent gaps in data governance, digital literacy, and system integration continue to shape citizen experience. The SWOT and PEST analyses highlighted structural strengths such as a strong central mandate and mature e-government platforms, while also exposing weaknesses in legacy registers, uneven process quality, and digital exclusion in rural areas and among older citizens. When framed through Digital-Era Governance (DEG) and the New Public Service (NPS), these findings affirm that Kazakhstan’s public-service reforms are transitioning from fragmented digitization to integrated, citizen-centered delivery. This alignment with SDG 16 (effective, accountable institutions), SDG 9 (infrastructure and innovation), and SDG 10 (reducing inequalities) underlines the global significance of Kazakhstan’s trajectory.

2. The segmented survey analysis shows clear territorial, demographic, and educational patterns that warrant targeted policy responses. First, territorial targeting should differentiate between industrial regions and large cities, emphasizing productive jobs and private-sector support, and agrarian regions, where active labor measures must be combined with basic services and transport connectivity. Second, gender and labor markets require reallocation and re-skilling programs, particularly for women and younger workers with less than 20 years of tenure, who are underrepresented in industrial sectors. Third, vulnerable households with overlapping disadvantages in employment, tenure, and education need prioritized support, including activation measures to return to employment and adult-education upskilling. Fourth, education remains a powerful anchor: higher education correlates with more stable employment and urban residence, so policies for digitization and improved job matching should explicitly address barriers faced by lower-educated groups. Taken together, these segment-based interventions ensure that digital public services do not amplify existing disparities but instead help close them.

3. The diagnostic themes from the SWOT and PEST analyses point to six interlocking system reforms. First, legally codify once-only data exchange and composite and proactive services as mandatory design principles. Second, create a national data-governance program with chief data stewards, master data management, and API-based interoperability aligned with open standards. Third, institutionalize capacity-building for service teams through a Digital Government Academy, career-long learning, and communities of practice. Fourth, adopt international standards for cross-border service models and algorithmic assurance to lower coordination costs and enhance trust. Fifth, strengthen cybersecurity and privacy by introducing data protection impact assessments, independent audits, and public transparency notes on data flows. Sixth, treat inclusive digital literacy and assisted channels as permanent public infrastructure, co-designed with civil society and delivered via PSCs, mobile units, and schools. These measures directly tackle the bottlenecks exposed to the diagnostics and align reform sequencing with institutional readiness.

4. Building on the system-level recommendations, Kazakhstan should invest in career-long capacity-building for civil servants, inclusive digital literacy for the public, and adaptive feedback mechanisms that turn citizen input into visible improvements. Competencies should span service design, data stewardship, privacy and security, accessibility, AI literacy, and participatory methods. Inclusive digital literacy should be delivered as public infrastructure through multilingual, accessible, and mobile training programs, complemented by permanent assisted channels. Feedback should be captured at scale, processed securely, acted upon, and made transparent through “You said, we did” dashboards. These steps will close the loop between design, delivery, and accountability, reinforcing public trust and reducing the urban and rural digital divide.

Reframing Kazakhstan’s digital reforms against the Sustainable Development Goals clarifies their broader significance. Codifying fail-safe rules, investing in interoperable registers, and expanding rural connectivity all advance SDG 16 (accountable institutions), SDG 9 (reliable, sustainable infrastructure), and SDG 10 (equal opportunity). Sequencing should prioritize quick-win composite services, medium-term data-sharing and workflow redesign, and longer-term AI-assisted services with robust safeguards. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of these reforms using both quantitative and qualitative measures, while cross-border collaborations can position Kazakhstan as a regional leader in citizen-centric digital transformation.

5 Conclusion

Kazakhstan’s public service delivery system has advanced through successive stages of digital transformation, moving from foundational infrastructure and basic e-services toward proactive, composite, and citizen-centric models. By analyzing legal and institutional frameworks alongside large-scale survey and expert data, this study demonstrates both the progress achieved and the systemic challenges that remain. Digital-Era Governance, the New Public Service, and the Sustainable Development Goals provide a coherent lens through which to interpret these findings: reforms must integrate legality, inclusiveness, and trust rather than simply accelerate service delivery.

The evidence underscores the need to embed “fail-safe” procedures, codify once-only data exchange, and institutionalize capacity-building as preconditions for sustainable scale-up. Equally, inclusive digital literacy and permanent assisted channels should be treated as core public infrastructure to prevent the widening of existing disparities. Targeted interventions, tailored to territorial, gender, and educational divides, are essential to ensure that digital public services expand opportunity rather than reinforce inequality.

Looking ahead, Kazakhstan can consolidate its position as a regional leader by sequencing reforms strategically: start with legal and data-governance foundations; scale interoperable systems, cross-border pilots, and literacy programs; then deploy AI-assisted services with strong ethical and privacy safeguards. Continuous feedback loops and transparent performance indicators will sustain public trust and adaptive learning.

By uniting empirical evidence with normative guidance, this study contributes a roadmap for transforming public administration into a more inclusive, resilient, and citizen-centered digital ecosystem. The lessons here extend beyond Kazakhstan, offering emerging economies a model for balancing innovation with equity and accountability in the digital age.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because Informed consent was embedded in the questionnaire form and explicitly agreed to by all participants prior to proceeding with the survey. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, grant IRN AP22787363.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The software ChatGPT was used to improve the translation of texts.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note