- 1Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, The First People’s Hospital of Zunyi (The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University), Zunyi, China

- 2Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guiyang, China

- 3Department of Pediatric Rehabilitation, The First People’s Hospital of Zunyi (The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University), Zunyi, China

- 4Department of Pediatric Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China

- 5Department of Pediatric Surgery, Guizhou Children’s Hospital, Zunyi, China

Background: Nudging has gained momentum in healthcare as a behavioral strategy to support beneficial health choices. However, its ethical legitimacy remains contested, especially regarding autonomy, transparency, fairness, and risks of covert influence.

Objective: This scoping review synthesizes ethical debates on healthcare nudges and proposes governance principles to guide ethically responsible implementation.

Methods: We conducted a scoping review following the PRISMA-ScR framework across international and Chinese databases. Conceptual and empirical bioethics literature from 2013 to 2023 was analyzed through thematic synthesis.

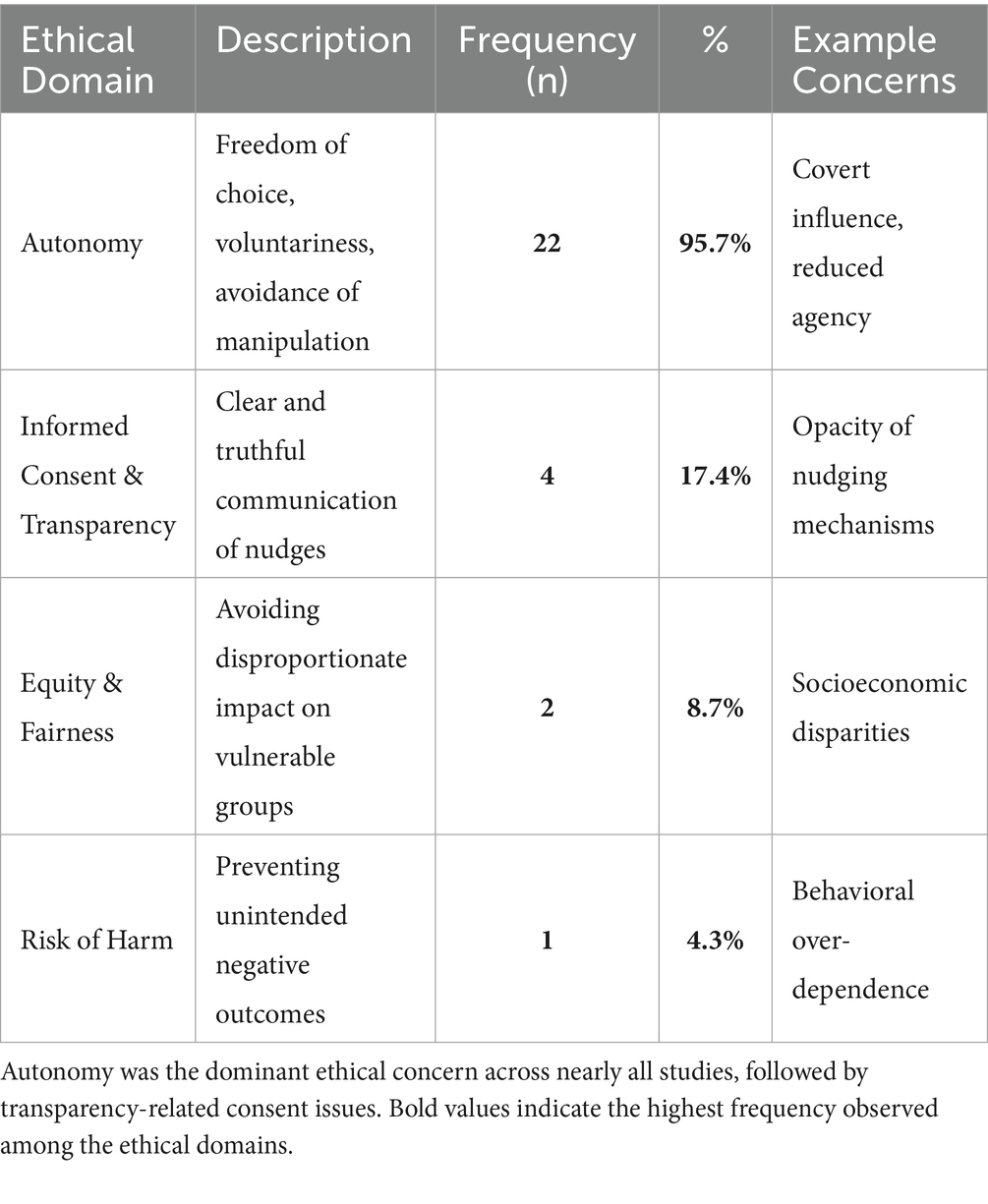

Results: Twenty-three studies met inclusion criteria. Ethical concerns centered on autonomy (22/23), informed consent and transparency (4/23), equity and distributive fairness (2/23), and risk of unintended harm (1/23). Reflective nudges that support deliberation were more widely endorsed than covert defaults. Recent scholarship emphasizes transparency, proportionality, stakeholder participation, and equity audits as conditions for ethical legitimacy.

Contribution: To our knowledge, this is the first review to systematically synthesize ethical dimensions of healthcare nudges using the PRISMA-ScR framework and to propose an actionable governance model for responsible behavioral regulation. The review advances ethical theory by integrating principlism, consequentialism, and deontology with cross-cultural public health ethics, and policy insights by identifying operational safeguards for health systems.

Conclusion: Healthcare nudges can be ethically justified when designed with transparency, meaningful opt-out options, proportionality of influence, and equity safeguards. Responsible behavioral governance requires culturally sensitive implementation, independent oversight, and continuous monitoring of autonomy and fairness outcomes. Future empirical work should examine real-world impacts on patient agency and equity across diverse clinical and cultural contexts.

1 Background

Nudge theory—originally conceptualized by Thaler and Sunstein as a form of “libertarian paternalism” that shapes choices without restricting options—has become increasingly influential in healthcare policy and clinical practice (1, 2). Nudges have been deployed to improve vaccination uptake, chronic disease prevention, organ donation, medication adherence, and digital health engagement.

Despite their promise, nudges have sparked vigorous ethical debate. A central fault line exists between Sunstein’s defense of nudges as autonomy-preserving tools that steer individuals toward welfare-enhancing behaviors and Hausman’s critique that nudges may disguise coercion under the guise of freedom, thereby compromising authentic self-determination (3, 4). This debate anchors broader philosophical disputes between:

1. liberal paternalism vs. autonomy maximization,

2. welfare promotion vs. manipulation avoidance, and

3. subtle influence vs. explicit consent in health decision-making.

Autonomy, informed consent, and public health ethics are conceptually interconnected in these debates. Autonomy requires individuals to understand influences on their choices and retain voluntary control. Informed consent operationalizes autonomy by demanding transparency and comprehension. Public health ethics balances individual freedom with collective welfare, prompting ongoing tension between voluntariness and utilitarian justification in behavioral interventions (2, 5).

While nudging has often been ethically defended on consequentialist or utilitarian grounds—particularly where it reduces disease burden or enhances health equity—critics argue that hidden steering may bypass deliberation and violate procedural respect for persons, even when outcomes are beneficial (4, 6). Recent scholarship advances frameworks such as ethical behavioral governance and participatory nudging to reconcile these tensions by emphasizing transparency, stakeholder engagement, and accountability (7–9).

Furthermore, cultural values shape ethical interpretations of nudging. Western liberal bioethics prioritizes individual autonomy, explicit consent, and freedom from interference, making transparency a prerequisite for ethical legitimacy (10). In contrast, East Asian contexts rooted in Confucian and communitarian philosophies place greater emphasis on relational autonomy, social harmony, and solidarity, making public-health nudges more acceptable when aligned with collective welfare and culturally situated norms (11, 12). Yet, critics warn that invoking collective good must not legitimize unchecked paternalism, reinforcing the need for culturally sensitive but principled safeguards.

Given these contested ethical landscapes, a scoping review design is well-suited to map evolving arguments, identify conceptual patterns, and synthesize multidisciplinary discourse across bioethics, public health, behavioral economics, and political philosophy. Unlike narrative reviews, scoping reviews allow systematic identification of competing ethical positions and emergent trends, which is essential when navigating morally charged, rapidly developing policy tools such as nudges.

2 Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) framework to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility. The review aimed to address two primary research questions: (1) What barriers hinder the resolution of ethical concerns associated with applying nudge theory in healthcare? and (2) What strategies have been proposed to manage these ethical issues?

2.1 Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed across both international and Chinese databases, including the Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP Database, Wanfang Data, and SinoMed (CBMdisc). All databases were searched from their inception to December 31, 2024, with no restrictions on study design but limited to English and Chinese publications.

The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms across three main domains: (1) “nudge,” “nudging,” or “nudge theory”; (2) “health,” “medical,” “clinical,” or “public health”; and (3) “ethic,” “ethics,” or “ethical issue.” Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to structure the queries.

An example Boolean search string (PubMed) is as follows:

(“nudge” OR “nudging” OR “nudge theory”) AND (“health” OR “medicine” OR “public health” OR “clinical practice”) AND (“ethics” OR “ethical issue” OR “bioethics”).

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Eligibility was defined using the PCC (Population–Concept–Context) framework (13). Studies were included if they:

(P) Discussed patients, healthcare providers, or public populations affected by nudges;

(C) Examined ethical issues related to nudge theory (e.g., autonomy, consent, justice, risk); and.

(C) Were situated in health-related domains such as clinical care, disease prevention, nutrition, pharmacotherapy, digital health, or public health policy.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) non-English or non-Chinese publications; (2) absence of full-text access; and (3) articles that did not explicitly address ethical issues related to nudge applications.

2.3 Study selection

The study selection process followed PRISMA 2020 recommendations. All retrieved records were imported into NoteExpress (version 3.9) for duplicate removal. Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and if consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer adjudicated the decision. To ensure inter-rater reliability, a pilot calibration exercise was conducted prior to full screening, resulting in a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.87, indicating strong agreement.

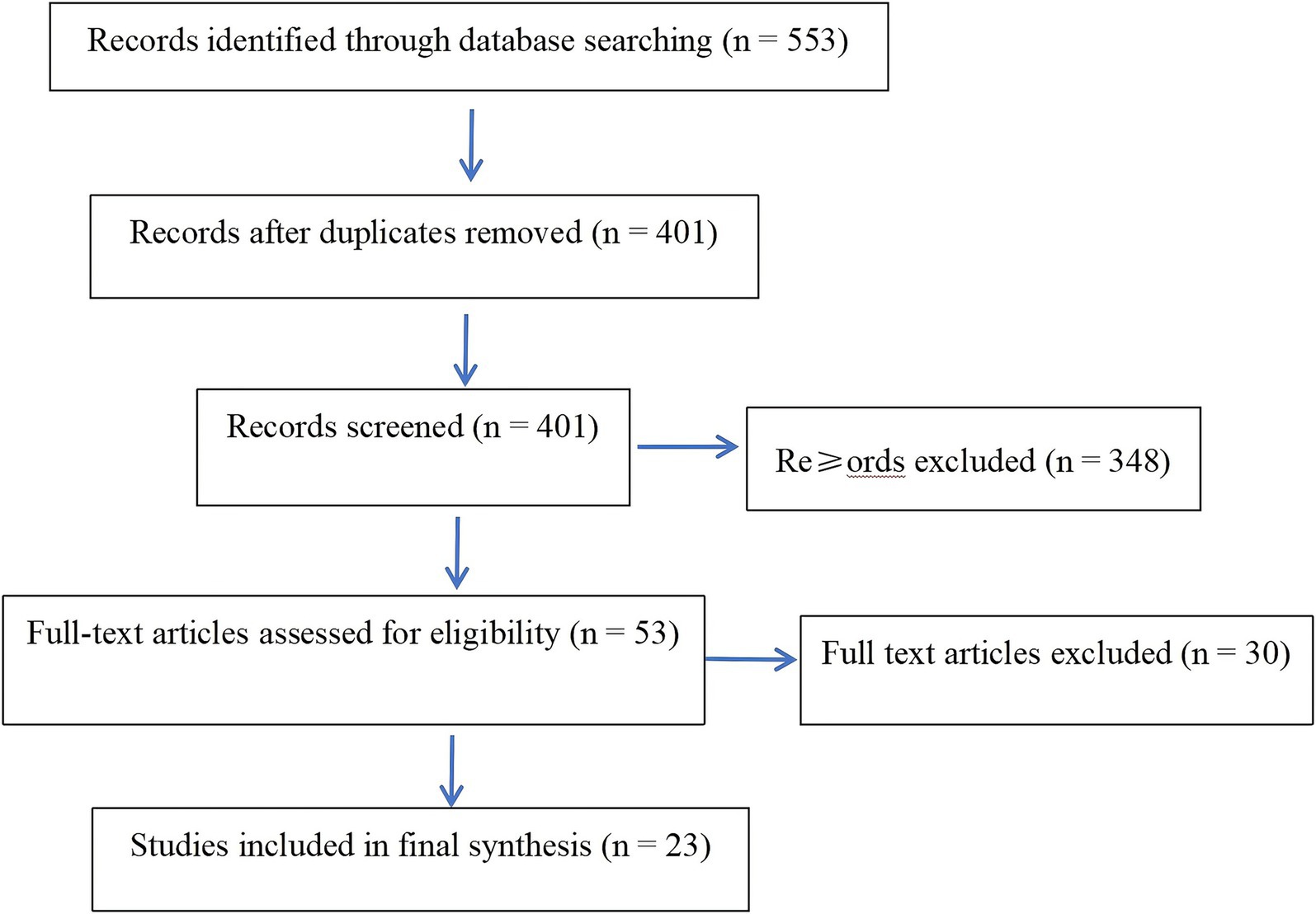

A total of 553 records were identified. After removing duplicates, 401 unique studies remained. Following title and abstract screening, 53 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Thirty were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria, leaving 23 studies for final synthesis (6, 8, 14–34). The complete selection process is depicted in Figure 1 (PRISMA Flow Diagram).

2.4 Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction was independently performed by two reviewers using a standardized data charting form developed for this study. Extracted variables included:

• author(s) and year of publication,

• country or region,

• study design,

• ethical domains addressed, and.

• proposed coping strategies or ethical frameworks.

To ensure consistency, reviewers underwent initial calibration training and pilot testing of the extraction form. All disagreements during data charting were discussed and resolved collaboratively, with audit verification by a senior reviewer.

The extracted data were summarized using descriptive statistics and thematic synthesis. Frequency analysis was applied to identify the most prevalent ethical issues (e.g., autonomy, consent, fairness, risk). Qualitative findings were organized into four major ethical domains—autonomy, informed consent, distributive justice, and risk mitigation—to facilitate comparison across studies.

2.5 Detailed search strategy

To ensure transparency and reproducibility, the complete Boolean search strings for all databases are provided below, in accordance with PRISMA-ScR guidelines.

PubMed(“nudge” OR “nudging” OR “nudge theory”)

AND (“health” OR “medicine” OR “public health” OR “clinical practice”)

AND (“ethics” OR “ethical issue” OR “bioethics”)<italic>Date range</italic>: From inception to December 31, 2024<italic>Language restriction</italic>: English OR Chinese

Embase

(‘nudge theory’/exp. OR ‘nudge’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘nudging’:ti,ab,kw)

AND (‘health care’/exp. OR ‘public health’/exp. OR ‘medicine’:ti,ab,kw).

AND (‘ethics’/exp. OR ‘ethical issue’:ti,ab,kw).<italic>Language restriction</italic>: English OR Chinese

Web of Science

TS = ((“nudge” OR “nudging” OR “nudge theory”)

AND (“health” OR “medicine” OR “public health”)

AND (“ethics” OR “ethical issue” OR “bioethics”))<italic>Date range</italic>: Up to December 31, 2024

Cochrane Library

(“nudge” OR “nudging” OR “nudge theory”)

AND (“ethics” OR “bioethics” OR “ethical issue”)<italic>Scope</italic>: Reviews, protocols, and trials relevant to ethical design in healthcare

CINAHL

(MH “Nudge Theory” OR TI “nudge” OR AB “nudging”)

AND (MH “Health Behavior” OR “public health” OR “clinical practice”)

AND (MH “Ethics” OR “ethical issue” OR “bioethics”)<italic>Filters applied</italic>: Peer-reviewed articles; English or Chinese

CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure)

Subject = (Nudge OR Nudge Theory)

AND Subject = (Ethics OR Ethical Issue OR Medical Ethics)<italic>Date range</italic>: From inception to December 31, 2024

Wanfang Database

Subject = (Nudge OR Nudge Theory)

AND (Medicine OR Public Health OR Health Management)

AND (Ethics OR Ethical Issue)

VIP Database

(“Nudge” OR “Nudge Theory”) AND (“Ethics” OR “Ethical Issue”) AND (“Health” OR “Medicine”)

SinoMed (CBMdisc)

(“Nudge” OR “Nudge Theory”) AND (“Ethics” OR “Ethical Issue”) AND (“Healthcare” OR “Public Health”)

Notes

• The search cutoff date for all databases was December 31, 2024.

• Only English and Chinese studies were included.

• All searches were independently conducted and verified by two reviewers, with third-party validation.

• ·All records were imported into NoteExpress (v3.9) for deduplication and management.

• The detailed selection and screening process is illustrated in Figure 1 (PRISMA Flow Diagram).

2.6 Data analysis

Extracted data were synthesized using a qualitative thematic approach. Following iterative review and coding, ethical issues were categorized into conceptual domains (autonomy, informed consent, distributive justice, and risk). Frequency counts were used to summarize the prevalence of each domain across included studies. No meta-analysis was conducted, consistent with the methodological nature of a scoping review. All analysis procedures adhered to PRISMA-ScR guidance to ensure rigor, transparency, and reproducibility.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

A total of 553 records were identified through database searches. After removing 152 duplicates, 401 unique records remained for screening. Following title and abstract screening, 348 articles were excluded for not meeting eligibility criteria. Fifty-three full-text articles were reviewed in detail, resulting in 30 exclusions due to lack of ethical focus or insufficient relevance to healthcare nudging. Ultimately, 23 studies were included in the final synthesis (Figure 1).

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

The 23 included studies were published between 2013 and 2023. Most originated from high-income Western countries including the United States (n = 8) (12, 13, 15, 19, 21, 24–26), Norway (n = 3) (14, 18, 29), the United Kingdom (n = 2) (16, 23), and the Netherlands (n = 2) (20, 28). A smaller but meaningful proportion came from Asian regions such as China and Singapore (5, 8), as well as additional countries including France (30), Greece (11), Italy (22), Israel (27), Denmark (17), and Brazil (6), reflecting a growing global interest in ethical dimensions of nudging.

Most studies employed conceptual or normative ethical analysis, while several incorporated case-based ethical reflection or policy evaluation (Table 1).

3.3 Ethical themes identified

Across the included studies, four core ethical domains emerged (Table 2). Autonomy-related concerns were the most prevalent, appearing in 22 studies (5, 6, 8, 11–23, 25–30), highlighting risks of covert manipulation, coercive defaults, and diminished voluntariness. Issues of informed consent and transparency were discussed in four studies (13, 14, 19, 24), focusing on inadequate disclosure and limited user understanding. Equity and distributive fairness concerns appeared in two studies (5, 12), emphasizing disproportionate effects on vulnerable populations. One study (18) identified risk of harm, noting unintended negative outcomes associated with nudging strategies.

3.4 Synthesis of key trends

Across included studies, autonomy and transparency emerged as the central normative benchmarks in ethical evaluation of nudges. Evidence suggests that ethically acceptable nudges should be:

• Clear and transparent.

• Respectful of individual deliberation.

• Proportionate in behavioral influence.

• Aligned with long-term welfare.

Narrative comparisons showed a general preference for Type 2 (reflective) nudges over Type 1 (automatic) nudges, particularly in clinical contexts where patient agency must remain paramount.

Emerging research—especially in the context of digital health and algorithmic guidance—raised concerns regarding opacity, hidden persuasion, and unequal behavioral effects, underscoring the need for procedural fairness and stakeholder engagement.

4 Discussion

This review demonstrates that ethical debate around healthcare nudges remains dominated by concerns about autonomy and transparency, accompanied by increasing attention to equity and distributive justice. Across empirical and normative literatures, respect for individual agency, intelligible disclosure, proportionality of influence, and fairness in behavioral impact emerged as core ethical benchmarks. Reflective nudges that promote deliberation were more widely endorsed than automatic nudges that subtly manipulate default behaviors, particularly in clinical and consent contexts. Recent research suggests that algorithmically mediated nudges may intensify these concerns by introducing opaque cognitive steering mechanisms, which necessitate new transparency protocols and governance safeguards (35).

The integration of principlism, consequentialism, and deontology provides a coherent ethical foundation for evaluating nudging interventions. From a principlist lens, protecting autonomy and avoiding harm remain essential conditions for ethical legitimacy (31). Consequentialist reasoning supports nudges when measurable public health benefits outweigh minimal intrusion, provided transparency safeguards are upheld (33, 36). By contrast, a deontological perspective demands truthful and non-coercive influence regardless of outcome, a position that strengthens ethical requirements for disclosure and voluntariness (37). Emerging theoretical models such as “boosting” or “self-nudging” prioritize individual agency and cognitive empowerment over external control, aligning with democratic and participatory frameworks for behavioral policy (38).

Recent scholarship emphasizes “responsible behavioral governance” models, including public justification of nudging mechanisms, participatory design, and equity audits in digital health contexts (36, 39, 40). These developments reflect a shift from libertarian paternalism to procedural ethics, in which legitimacy depends not only on outcomes but also on transparency, accountability, and cultural sensitivity. Notably, scholars have raised concerns that predictive governance systems—especially those embedded within AI infrastructures—may erode voluntariness and blur the line between influence and manipulation, prompting calls for algorithmic accountability and ethical constraints (41).

In East Asian contexts informed by collectivist ethics, nudges aimed at promoting shared welfare may obtain broader acceptance when transparency and community benefit are clearly communicated (12, 42). However, recent psychological analysis indicates that AI-enabled nudging may also trigger unintended mental health effects, such as reduced agency or perceptual dissonance, particularly in sensitive populations (43). Thus, ethical nudging must be culturally adaptive, yet anchored in universal principles of agency, fairness, and harm prevention.

To support ethical implementation, policymakers and ethics committees should adopt structured evaluation protocols, such as proportionality tests, disclosure standards, equity impact assessments, and sunset clauses for high-influence defaults. Incorporating behavioral ethics into professional training could further strengthen governance and mitigate risks of cognitive paternalism and digital influence asymmetry. Public-sector case studies demonstrate the feasibility of integrating AI-driven behavioral interventions with ethics-by-design principles and participatory oversight frameworks (44). Similar governance challenges have been addressed in domains such as taxation, where AI-powered nudging systems have prompted the development of predictive monitoring tools grounded in ethical compliance protocols (45).

4.1 Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, only English-language publications were included, which may introduce linguistic bias and underrepresent relevant scholarship published in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and other languages—particularly important given the growing ethical discourse in Asian bioethics. Second, gray literature, policy briefs, and government white papers were excluded, potentially omitting pragmatic ethical insights on applied behavioral governance. Third, conceptual and normative studies dominated the dataset, meaning that empirical verification of ethical risks and outcomes remains limited; conclusions are therefore predominantly interpretive. Finally, digital health nudges and AI-mediated behavioral tools were underrepresented in studies before 2020, suggesting that ethical implications of algorithmic nudging require ongoing attention as the field evolves.

Despite these constraints, rigorous screening, independent coding, triangulation, and sensitivity checks strengthened analytic reliability and helped mitigate interpretive bias.

5 Conclusion

Healthcare nudges hold substantial promise in advancing public health goals while preserving individual choice. This review demonstrates that ethical legitimacy hinges on transparency, meaningful autonomy preservation, proportionality of influence, and equity in behavioral impact. By grounding analysis in ethical theory and cross-cultural perspectives, our findings contribute to evolving frameworks for responsible behavioral governance in healthcare.

We propose that ethical nudges be governed through transparent disclosure, equity assessment, proportionality justification, and independent oversight. As digital behavioral technologies expand, ongoing empirical evaluation—particularly of patient comprehension, voluntariness, and equity outcomes—will be essential.

Beyond China’s rapidly developing behavioral health environment, these recommendations offer globally applicable insights for ethical policy design, ensuring that nudges function not as covert persuasion tools but as respectful, participatory, and socially equitable public health instruments.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LX: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KC: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. RT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft. JT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft. XS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Science and Technology Cooperation Program of Zunyi City, Guizhou Province, China (Grant No. ZunShiKeHe HZ [2024] No. 84).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Thaler, RH, and Sunstein, CR. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press (2008).

2. Sunstein, CR. Nudging and choice architecture: ethical considerations. Yale J Regul (2015) 32:413–450. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjreg/vol32/iss2/6

3. Hausman, DM, and Welch, B. Debate: to nudge or not to nudge. J Polit Philos. (2010) 18:123–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00351.x

4. Engelen, B. Ethical criteria for health-promoting nudges: a case-by-case analysis. Am J Bioeth. (2019) 19:48–59. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2019.1588411

6. Schmidt, AT. The power to nudge. Am Polit Sci Rev. (2017) 111:404–17. doi: 10.1017/S0003055416000664

7. Reijula, S, and Hertwig, R. Self-nudging and the citizen choice architect. Behav Public Policy. (2021) 5:90–106. doi: 10.1017/bpp.2020.22

8. Yeung, K. Hypernudge’: big data as a mode of regulation by design. Inf Commun Soc. (2017) 20:118–36. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1186713

9. Wachner, J. Do nudges harm autonomy? Empirical studies on the effect of nudges on expected and experienced autonomy [Ph.D. thesis] Utrecht, Netherlands Utrecht University 2022. Available online at: https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/422844

10. Beauchamp, TL, and Childress, JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press (2013).

11. Fan, R. Reconstructing the Confucian concept of autonomy: a relational approach. Asian Bioeth Rev. (2010) 2:71–83. doi: 10.1353/asb.0.0027

12. Ho, A. Relational autonomy or undue pressure? Family’s role in medical decision-making. Scand J Caring Sci. (2008) 22:128–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00561.x

13. Chan, SL, Ho, CZH, Khaing, NEE, Ho, E, and Pong, C. Frameworks for measuring population health: a scoping review. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0278434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278434

14. Sunstein, CR. Are nudges ethical? Perspect Psychol Sci. (2022) 17:15–26. doi: 10.1177/1745691621995183

15. Blumenthal-Barby, JS, and Burroughs, H. Seeking better health care outcomes: the ethics of using the “nudge”. Am J Bioeth. (2012) 12:1–10. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2011.634481

16. Arneson, RJ. Nudge and shove. Soc Philos Policy. (2015) 32:260–89. doi: 10.1017/S0265052515000108

17. Grüne-Yanoff, T. Old wine in new casks: libertarian paternalism still violates liberal principles. Soc Choice Welfare. (2012) 38:635–45. doi: 10.1007/s00355-011-0636-0

18. Rebonato, R. Taking liberties: a critical examination of libertarian paternalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan (2012).

19. Bovens, L. The ethics of nudge In: T Grüne-Yanoff and SO Hansson, editors. Preference change: approaches from philosophy, economics and psychology. Dordrecht: Springer (2009). 207–19.

20. Nihlén Fahlquist, J. Ethical problems with nudges in public health: the case of Sweden’s COVID-19 strategy. J Bioeth Inq. (2021) 18:629–38. doi: 10.1007/s11673-021-10130-0

22. Floridi, L. Soft ethics and the governance of the digital. Philos Technol. (2018) 31:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s13347-017-0261-x

23. Nys, T, and Engelen, B. Judging nudging: answer to critics. Int J Philos Stud. (2017) 25:202–20. doi: 10.1080/09672559.2016.1262440

24. Kim, SYH, and Mills, AE. Ethical reflection on nudging in healthcare. Hast Cent Rep. (2019) 49:33–42. doi: 10.1002/hast.1024

25. Felsen, G, and Reiner, PB. How much control do we have? A review of the evidence for and against libertarian paternalism. Am J Bioeth Neurosci. (2015) 6:25–36. doi: 10.1080/21507740.2015.1047050

26. Selinger, E, and Whyte, K. Is there a right way to nudge? The practice and ethics of choice architecture. Sociol Compass. (2011) 5:923–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00413.x

27. Furey, M, Wilmot, S, and Scully, JL. Nudge ethics: a review. Health Care Anal. (2021) 29:317–34. doi: 10.1007/s10728-020-00401-5

28. Blumenthal-Barby, JS. Between reason and coercion: ethically permissible influence in health care and health policy contexts. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. (2012) 22:345–66. doi: 10.1353/ken.2012.0008

30. Volpp, KG, Loewenstein, G, and Asch, DA. Choosing wisely: low-value services, utilization, and patient cost sharing. JAMA. (2012) 308:1635–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13616

31. Sugden, R. Do people really want to be nudged towards healthy lifestyles? Int Rev Econ. (2017) 64:113–23. doi: 10.1007/s12232-016-0264-1

32. Marchiori, DR, Adriaanse, MA, and de Ridder, DT. Unresolved questions in nudging research: putting the psychology back in nudging. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. (2017) 11:e12297. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12297

33. Grüne-Yanoff, T, and Hertwig, R. Nudge versus boost: how coherent are policy and theory? Mind Mach. (2016) 26:149–83. doi: 10.1007/s11023-016-9387-z

34. Saghai, Y. Salvaging the concept of nudge. J Med Ethics. (2013) 39:487–93. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-100727

35. Rodriguez-Fernandez, F. Artificial intelligence and economic psychology: toward a theory of algorithmic cognitive influence. AI Soc. (2025). doi: 10.1007/s11023-015-9367-9

36. Ploug, T, and Holm, S. Doctors, patients, and nudging in the clinical context—four views on nudging and informed consent. Am J Bioeth. (2015) 15:28–38. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2015.1074303

38. Reijula, S, and Hertwig, R. Boosting agency: behavioral policy for democratic societies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (2024).

39. Sunstein, CR. Sludge: What stops us from getting things done and what to do about it. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (2021).

40. Reijula, S, and Hertwig, R. Self-nudging and the citizen choice architect. Behav Public Policy. (2020) 4:90–105. doi: 10.1017/bpp.2018.22

41. Yeung, K. AI nudging and ethics in the age of predictive governance In: Governance Futures. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2025) [Forthcoming]

42. Fan, R. Self-determination vs. family-determination: two incommensurable principles of autonomy. Bioethics. (1997) 11:309–22. doi: 10.1111/1467-8519.00070

43. Hudon, A, and Stip, E. (2024). Artificial intelligence and the emergence of AI-psychosis: a viewpoint. ResearchGate [Preprint]. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/396563261_Artificial_Intelligence_and_the_Emergence_of_AI-Psychosis_A_Viewpoint

44. Mohamed, R, Bouasria, B, and Jamal, EA. 2025. The integration of artificial intelligence and the contributions of behavioral economics into public management in Morocco. In: 2025 IEEE conference on governance & AI.

Keywords: nudge theory, healthcare ethics, PRISMA-ScR, autonomy, behavioral governance, bioethics, health policy ethics, behavioral economics

Citation: Shang H, Xiong L, Chen K, Tian R, Tu J and Shang X (2025) Ethical dimensions of healthcare nudges: a PRISMA-ScR–guided scoping review and framework for responsible behavioral governance. Front. Public Health. 13:1716466. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1716466

Edited by:

Deep Shikha, Swami Rama Himalayan University, IndiaReviewed by:

Faiz Albar Nasution, University of North Sumatra, IndonesiaAhmad Zaini Miftah, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Shang, Xiong, Chen, Tian, Tu and Shang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lingfang Xiong, MTgxNjYxMDc1QHFxLmNvbQ==

Huijing Shang1

Huijing Shang1 Xianhui Shang

Xianhui Shang