- Business School, Huanggang Normal University, Huanggang, China

Modern food systems face unprecedented challenges that require transformative policy responses beyond conventional forecasting. We argue that scenario building and science fiction narratives can serve as tools for policy innovation, helping stakeholders to consider complexity, weigh trade-offs, and shape more adaptive strategies. By synthesizing insights from foresight studies, participatory scenario exercises, and narrative approaches, this perspective suggests that creative future visions can support new policy pathways toward sustainable food systems. These methods offer co-created visions of possible futures encompassing climate, diets, technologies, and governance systems.

1 Introduction

Conventional forecasting models rely on extrapolations of past trends, projecting futures as linear extensions of the present [Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2022]. While valuable for stable conditions, these approaches falter when confronted with discontinuous changes, tipping points, and novel socio-ecological configurations, which are precisely the challenges facing contemporary food systems. Climate disruption, dietary transitions, technological breakthroughs, and geopolitical shifts create conditions where systems may cross critical thresholds, such as the Amazon rainforest shifting from carbon sink to source (Nobre et al., 2016), with cascading consequences for agriculture and food security. Agricultural and food systems, which are inherently complex and adaptive, require futures thinking approaches that accept uncertainty, complexity, and diversity (Wiebe and Prager, 2021).

Future scenario development, participatory foresight, and speculative narratives are useful tools for policy design because they increase possible futures (Vervoort and Gupta, 2018). By using imaginative tools like science fiction to build scenarios, researchers can test new pathways and challenge existing beliefs. Such approaches support policy innovation, which involves the development of novel policy instruments, governance arrangements, or problem framings that represent substantive departures from established approaches (Howlett, 2014). Policy innovation becomes essential when conventional frameworks prove inadequate for addressing wicked problems characterized by complexity, uncertainty, and conflicting values.

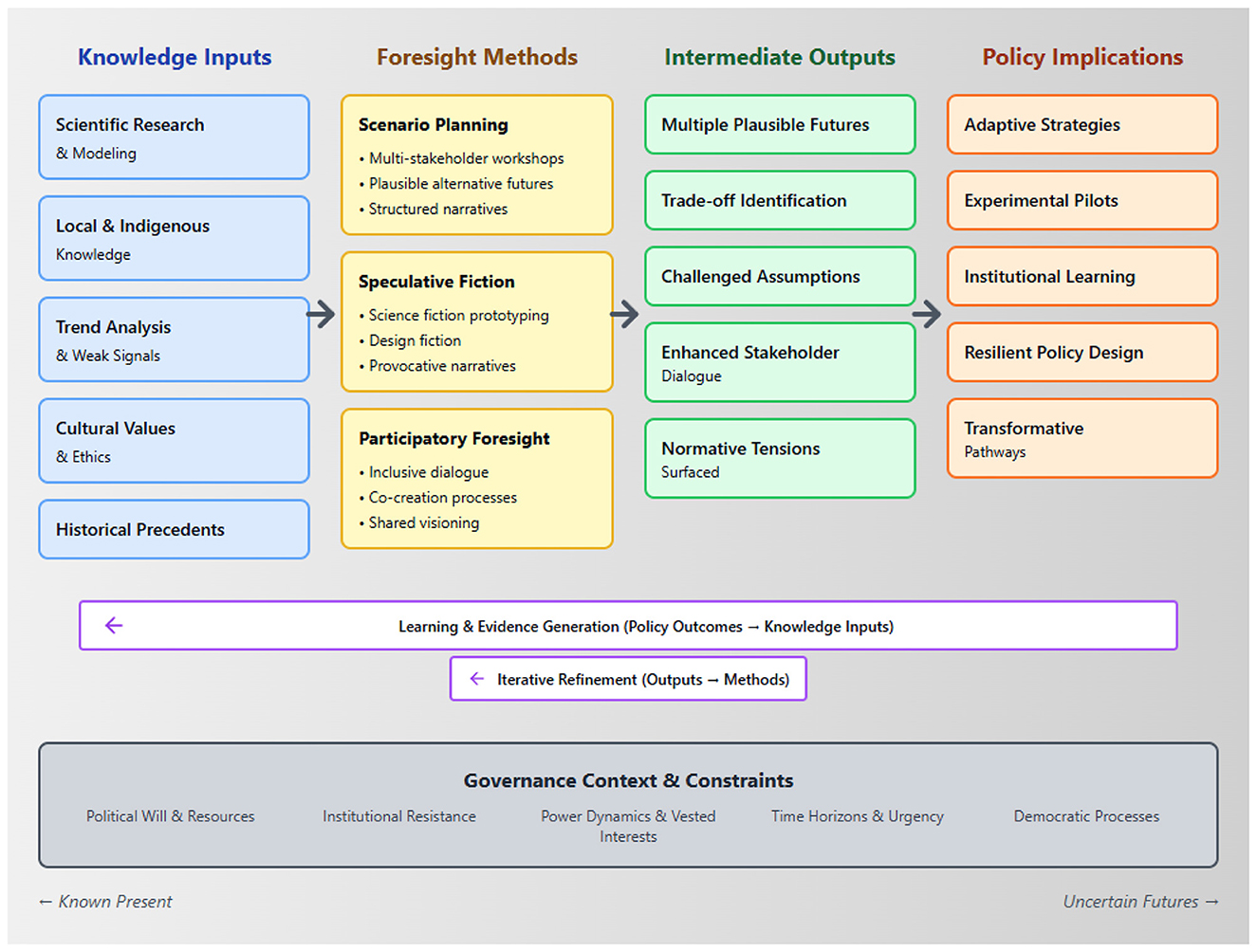

This paper combines ideas from sustainability science, futures studies, and public policy to argue that scenarios and future-oriented narratives can be effective tools for governing agricultural systems and food production. These approaches allow stakeholders to deal with emerging issues, identify emerging opportunities, and support the formulation of more flexible and inclusive policies by combining scientific knowledge, local expertise, and creative ideas. We aim to demonstrate how integrating scenario planning with speculative fiction can enhance policy innovation in food systems, while acknowledging the political and institutional challenges that constrain such transformations. Figure 1 illustrates this conceptual framework, showing how different knowledge sources (scientific evidence, local expertise, and creative speculation) feed into iterative learning processes that inform policy outcomes. This integration enables more adaptive and inclusive food systems governance.

However, embracing transformative approaches requires more than methodological innovation; it demands shifts in how societies imagine possible futures. Drawing on Vertesi (2019) analysis of social imaginaries (the shared ways people imagine their social existence), we recognize that scenarios and fiction must contend with deeply embedded mental models. Adaptive thinking about food systems requires cultivating openness, curiosity, and critical reflexivity about one's assumptions (Dryzek, 2013). In democratic contexts, where diverse publics and officials may resist transformation, such capacities become essential yet extraordinarily difficult to develop. Officials may exploit public ambivalence for political advantage, while populations struggle to envision departures from familiar food practices. We therefore approach foresight methods with appropriate modesty, positioning them as valuable but insufficient tools requiring broader strategies for democratic social learning.

2 Integrating scenario design and participatory futures thinking in agriculture

Foresight, broadly defined, encompasses systematic approaches to exploring potential futures and their implications for present-day decision-making (Rohrbeck et al., 2015). A key foresight method, scenario planning constitutes a structured method for constructing and analyzing alternative future contexts to enhance strategic decision-making under uncertainty (Schoemaker, 1995). Widely employed in climate change and integrated assessment modeling (Pulver and VanDeveer, 2009), scenarios are not predictive but provide divergent paths for stakeholders to tackle uncertainty (van Vuuren et al., 2012). Rather than forecasting what will happen, scenarios explore what could happen under different combinations of uncertainties and trends (Ramirez and Wilkinson, 2016). By assessing multiple scenarios, policymakers and practitioners can enhance the resilience and adaptive capacity of food systems.

While scenario planning provides a structured means of exploring uncertainty, its value depends on whose perspectives shape the narratives. Participatory approaches enhance this process. Involving farmers, extension workers, civil society organizations, and local governments ensures that scenario narratives integrate on-the-ground realities, experiential knowledge, and cultural values (Johnson and Karlberg, 2017). However, participatory methods require careful attention to power imbalances, resource requirements, and stakeholder expectations (Reed, 2008). Such engagement is particularly valuable when examining transitions in dietary patterns and nutrition-related behavior, as it surfaces cultural values, resource constraints, and behavioral drivers critical for designing equitable interventions.

However, participatory methods require careful attention to power imbalances, resource requirements, and stakeholder expectations (Reed, 2008). Beyond practical concerns, participatory foresight confronts deeper challenges rooted in social imaginaries. Participants may find it difficult to transcend taken-for-granted understandings of how food systems work (Taylor, 2004). Meaningful engagement thus requires creating spaces for reflective practice where participants examine their framing assumptions (Schön, 1983), demanding patience and recognition that transformation in collective imagination proceeds slowly and unevenly.

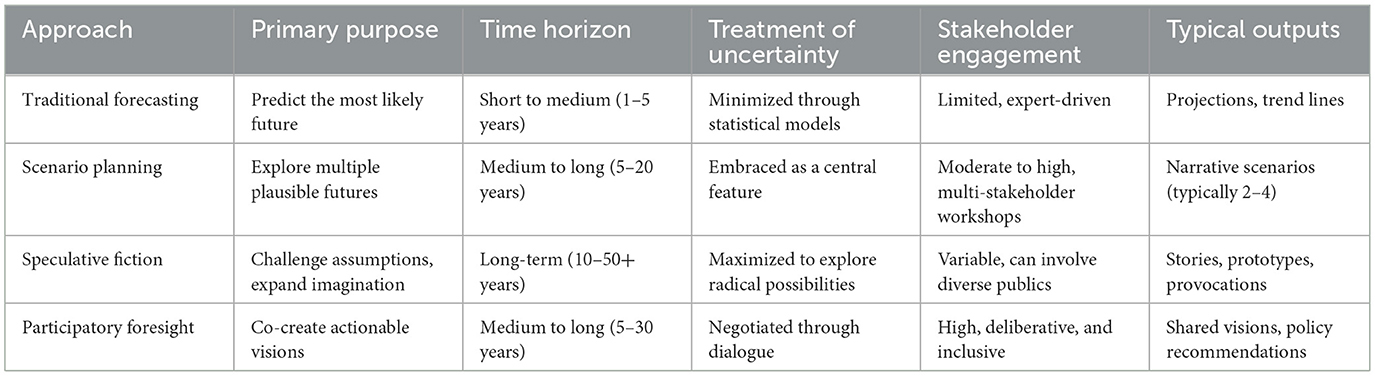

Such engagement is particularly valuable when examining transitions in dietary patterns and nutrition-related behavior, as it surfaces cultural values, resource constraints, and behavioral drivers critical for designing equitable interventions. When developed collaboratively, these scenario narratives help stakeholders identify and deliberate trade-offs and synergies among competing objectives. For example, a scenario in which there is a rapid shift toward plant-based protein sources may reduce greenhouse gas emissions and land pressure, but may also pose challenges related to nutrition adequacy, consumer acceptability, and cultural preferences. Such shifts also raise questions about dietary diversity, affordability, and the resilience of local food systems (Willett et al., 2019; Blackwell et al., 2024; Steiner et al., 2020). In another scenario, genetically engineered crops for climate resilience feature prominently, with prospects for higher yields and less vulnerability to drought and pests, along with challenges around seed sovereignty and corporate control (Pixley et al., 2019). Anticipating such trade-offs enables more nuanced policy making. Table 1 compares these foresight approaches across key dimensions, illustrating how different methods serve complementary purposes in food systems policy development.

While scenario planning provides structured exploration of plausible futures, speculative narratives and fiction can push boundaries further by challenging fundamental assumptions about food systems.

3 The role of speculative narratives in sustainable food policy development

Storytelling, including science fiction, plays a powerful complementary role (Marshall et al., 2023; Merrie, 2019; Vertesi, 2019). Science fiction and speculative fiction can free policymakers and stakeholders from the constraints of today's paradigms, allowing them to imagine futures that may not be considered plausible or desirable. This imaginative leap is valuable. What once appeared unthinkable, such as entirely automated vertical farms, community-owned digital seed libraries, or climate-induced collapses of major staple crops, can become legitimate subjects of policy consideration and contingency planning when explored through narratives.

To operationalize these imaginative practices, several methodological approaches formalize the use of speculative fiction in policy contexts, extending beyond entertainment to serve as tools for exploring possible futures (Candy and Kornet, 2019; Dunne and Raby, 2013). One such approach, science fiction prototyping (SFP), pioneered by Brian David Johnson at Intel Corporation, provides a structured approach: researchers identify emerging trends and uncertainties, construct narratives grounded in scientific plausibility, embed these narratives in scenarios of future use, and extract policy implications (Johnson, 2011). Importantly, SFP originated in corporate contexts where decision-making structures differ substantially from democratic policy processes. While the method offers valuable techniques for making futures tangible, its application to food systems governance requires adaptation to accommodate multiple publics, contested values, and distributed authority (Stilgoe et al., 2013). Unlike predictive modeling, SFP creates “prototypes of the future” that stakeholders can interrogate, critique, and refine, though the quality depends heavily on process design.

Beyond text-based prototyping, design fiction and speculative design translate imagined futures into tangible forms, such as mock-ups of future food packaging or speculative menus for climate-adapted cuisines (Auger, 2013; Dunne and Raby, 2013). In food systems, this might involve mock-ups of future food packaging, simulated interfaces for precision agriculture platforms, or speculative menus from climate-adapted cuisines. These artifacts provoke reflection on desirability, feasibility, and ethical implications.

While speculative fiction offers valuable imaginative capacities, these approaches also have limitations. Speculative and design-fiction practices can “close down” alternatives by privileging certain futures and publics unless they are deliberately opened to plural perspectives; more broadly, sociotechnical imaginaries often reflect and reproduce institutional power (Bardzell and Bardzell, 2013). The creative freedom that makes speculation valuable can also distance scenarios from practical constraints, and the narrative focus may emphasize dramatic possibilities over incremental but important changes. Effective use requires careful attention to whose futures are being imagined and for whom (Jasanoff and Kim, 2015).

Despite these limitations, speculative fiction adds significant value by complementing traditional scenario planning. While conventional scenarios map out plausible pathways, speculative fiction pushes boundaries by asking “what if?” in more radical ways. For policy foresight, this combination helps decision-makers prepare for surprises, recognize weak signals, and maintain cognitive flexibility, which are crucial capacities in turbulent times (Ramirez and Wilkinson, 2016).

This approach has been employed in other domains of policy foresight. Researchers studying climate adaptation have been using narrative scenario approaches to envision future coastlines or energy systems, and sometimes including elements of speculative fiction to also challenge assumptions and enrich debate (Rickards et al., 2014). Applied to food systems, several concrete examples illustrate this potential. The Institute for the Future's Food Futures Lab has developed speculative scenarios exploring distributed food production, synthetic biology in agriculture, and climate-adapted diets, engaging diverse stakeholders in considering policy implications [Institute for the Future (IFTF), 2011]. Arizona State University's Center for Science and the Imagination has commissioned science fiction stories addressing food security, biotechnology governance, and sustainable agriculture, using these narratives in policy workshops and public engagement (Finn and Cramer, 2014). Margaret Atwood's MaddAddam trilogy, while fictional, has been analyzed by scholars examining biotechnology governance and food systems transformation, demonstrating how literary speculation can inform policy discourse (Milkoreit, 2017).

In the context of nutrition and sustainable diets, narratives can help anticipate how emerging foods, such as lab-grown proteins, biofortified crops, or climate-resilient staples, might be received by different populations. They can also explore how food culture, identity, and perceptions of health evolve in future food environments shaped by policy, climate, or technology.

Beyond the nutrition context, these narrative experiments are more than mere entertainment. Narratives can draw attention to normative tensions: who benefits, who loses, and who makes the decisions. They can highlight ethical dilemmas, reveal blind spots in contemporary research and policy priorities, or highlight underappreciated cultural heritage issues in food practices. By engaging readers on both emotional and intellectual levels, speculative stories can inspire new research directions, promote critical reflection, and foster innovative policy initiatives.

4 Linking futures thinking to policy implementation

While scenario planning and speculative narratives offer valuable tools for expanding policy imagination, their effectiveness ultimately depends on successful translation into policy action. In practice, this means that participatory workshops, stakeholder dialogues, strategic foresight training, and institutional processes should be carefully designed with the aspiration (though not the guarantee) that insights from scenario analysis might inform decision-making (Fleming et al., 2021). The language of “ensuring” integration overstates the control that facilitators possess in democratic contexts. Rather than designing systems that deterministically channel foresight into policy, practitioners can create conditions that make integration more likely: building trust through sustained engagement, demonstrating relevance to pressing concerns, and generating outputs aligned with policy processes. Yet integration remains contingent on political will, institutional receptivity, and often unpredictable windows of opportunity (Kingdon, 2011).

For scenarios and narratives to have policy impact, they must also be embedded in adaptive governance frameworks that value anticipation and reflection (Mitchell et al., 2015). To institutionalize the use of scenario analysis, policymakers could require regular updates of scenario analysis in agricultural development plans or establish multi-stakeholder scenario analysis working groups. Facilitators could present scenario results to policymakers to clarify what actions can be taken now to increase resilience and flexibility. For example, if agroecology is envisioned to be widely practiced under conditions of global market turmoil, policymakers could immediately invest in farmer-led research, local seed systems, and knowledge-sharing networks, rather than waiting until a crisis occurs (Ojoyi et al., 2017).

This approach can also guide policy experimentation and pilot initiatives. If scenarios suggest, for instance, that certain innovative practices such as perennial grain systems or blockchain-based supply chain transparency could prove valuable in multiple futures, policymakers might fund small-scale experiments to test feasibility and scalability (Chapman et al., 2022). Over time, iterative scenario exercises have the potential to create a feedback loop, with each round of futures thinking informing the evaluation and redesign of policies, enabling a learning-by-doing approach in governance (Wise et al., 2014). While empirical evidence of such feedback loops remains limited, emerging examples from adaptive management in natural resource governance demonstrate the viability of this approach (Armitage et al., 2009).

4.1 Navigating resistance and political challenges

Implementing futures-oriented approaches confronts predictable human and institutional resistance. When foresight exercises challenge dominant frames, initial reactions often involve defensiveness and entrenchment rather than openness (Dewulf and Bouwen, 2012). Psychological research on framing effects demonstrates that people cling to familiar interpretations when confronted with dissonant information, particularly when their identities or interests feel threatened.

Institutionally, policy regimes resist disruption through multiple mechanisms: regulatory frameworks favor incumbents, professional norms privilege established expertise, and resource allocation perpetuates existing priorities (Candel et al., 2014; Geels, 2014). Policymakers and institutional actors operate within entrenched governance structures, political coalitions, and policy frames that may actively defend established paradigms. Such regimes exhibit resistance to transformation, sustained by path dependencies, vested interests, and cognitive lock-in (Geels and Schot, 2007). Recognizing these dynamics calls for modest claims about the transformative potential of foresight and a clear-eyed understanding of the political work required for policy change.

These challenges are particularly acute in democratic food systems governance because of the intimate connection between food practices and cultural identity. Social imaginaries about food are woven into lived experience, bodily practices, and affective attachments (Carolan, 2011). Asking people to imagine radically different food futures (whether plant-based proteins replacing meat, vertical farms supplanting traditional agriculture, or algorithmic optimization governing food distribution) challenges deeply held notions of the good life, proper nourishment, and human relationships with land and animals. Taylor (2004) argues that shifts in social imaginaries occur gradually through accumulation of new practices and experiences rather than rational argument alone. This suggests that scenario exercises and speculative narratives, while valuable, cannot substitute for the slow work of building new lived realities that make alternative futures experientially plausible. Facilitators must approach foresight work with appropriate humility, positioning it as one element within broader ecosystems of social learning.

These dynamics have important implications. First, democratic processes of policy transformation require sustained commitment, resources, and political will, often spanning electoral cycles and outlasting the enthusiasm of initial champions (Meadowcroft, 2009). Scenario planning cannot bypass these temporal realities. Second, outcomes remain probabilistic and difficult to predict; even well-designed foresight processes may fail to shift policy if political conditions prove inhospitable. Third, stakeholders engaged in scenario exercises frequently express impatience for tangible results, creating pressure to demonstrate short-term value even as long-term transformation unfolds slowly (Ramirez and Selin, 2014). Managing this tension requires careful process design: celebrating incremental wins, maintaining transparent communication about timeframes, and building trust through inclusive participation. Facilitators must balance visionary ambition with realistic acknowledgment of constraints, positioning foresight not as a panacea but as one element within broader strategies for policy change.

5 Conclusion

Agriculture and food systems confront challenges such as climate instability, resource scarcity, dietary transitions, and social inequalities that exceed the capacity of traditional forecasting to adequately inform policy. Scenarios and speculative narratives offer tools for expanding mental models, exploring diverse futures, and challenging entrenched assumptions about food system transformation.

This paper contributes to scholarship by synthesizing foresight methods, speculative design, and policy studies into an integrated framework for food systems governance. We demonstrate how participatory scenario-building and speculative storytelling can inform policy innovation while acknowledging the substantial political and institutional barriers to implementation. These approaches are complementary to evidence-based research and field experiments, prompting policy communities to consider values, ethics, and priorities alongside technical solutions.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of scenarios and speculative fiction in food systems governance depends not only on methodological rigor but on cultivating civic capacities for futures thinking. This includes openness to unfamiliar possibilities, curiosity about alternative arrangements, critical self-reflexivity, and tolerance for ambiguity (Appadurai, 2013). These capacities must be nurtured through education, dialogue, and practice. In democratic societies facing urgent food system challenges and political polarization, expanding collective imagination becomes simultaneously more necessary and more difficult. We offer this framework recognizing that social imaginaries shift slowly and that resistance to transformative change (from both populations and officials) often represents rational responses to perceived risks and the difficulty of envisioning alternatives to deeply embedded ways of life.

Future research should empirically evaluate how scenario-based and speculative approaches influence policy outcomes across different governance contexts, document best practices for managing stakeholder expectations and power dynamics in participatory foresight, and explore how these methods can be scaled from local to regional and global levels while maintaining legitimacy and relevance.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Resources. AR: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Resources, Investigation, Validation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Armitage, D. R., Plummer, R., Berkes, F., Arthur, R. I., Charles, A. T., Davidson-Hunt, I. J., et al. (2009). Adaptive co-management for social–ecological complexity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 7:89. doi: 10.1890/070089

Auger, J. (2013). Speculative design: crafting the speculation. Digit. Creat. 24, 11–35. doi: 10.1080/14626268.2013.767276

Bardzell, J., and Bardzell, S. (2013). “What is “critical” about critical design?,” in CHI'13: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New York, NY: ACM), 3297–3306. doi: 10.1145/2470654.2466451

Blackwell, M. S. A., Takahashi, T., Cardenas, L. M., Collins, A. L., Enriquez-Hidalgo, D., Griffith, B. A., et al. (2024). Potential unintended consequences of agricultural land-use change driven by dietary transitions. NPJ Sustain. Agric. 2:1. doi: 10.1038/s44264-023-00008-8

Candel, J. J. L., Breeman, G. E., Stiller, S. J., and Termeer, C. J. A. M. (2014). Disentangling the consensus frame in food security: a meta-frame analysis. Food Policy 44, 47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.10.005

Candy, S., and Kornet, K. (2019). Turning foresight inside out: an introduction to ethnographic experiential futures. J. Futures Stud. 23, 3–22. doi: 10.6531/JFS.201903_23(3).0002

Chapman, E. A., Thomsen, H. C., Tulloch, S., Correia, P. M., Luo, G., Najafi, J., et al. (2022). Perennials as future grain crops: opportunities and challenges. Front. Plant Sci. 13:898769. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.898769

Dewulf, A., and Bouwen, R. (2012). Issue framing in conversations for change: discursive interaction strategies for “doing differences.” J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 48, 168–193. doi: 10.1177/0021886312438858

Dryzek, J. S. (2013). The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses, 3rd Edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dunne, A., and Raby, F. (2013). Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.

Finn, E., and Cramer, K. (2014). Hieroglyph: Stories and Visions for a Better Future. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Fleming, A., Jakku, E., Fielke, S., Taylor, B. M., Lacey, J., Terhorst, A., et al. (2021). Foresighting Australian digital agricultural futures: applying responsible innovation thinking to anticipate research and development impact under different scenarios. Agric. Syst. 190:103120. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103120

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2022). The Future of Food and Agriculture – Drivers and Triggers for Transformation. Rome: FAO.

Geels, F. W. (2014). Regime resistance against low-carbon transitions: introducing politics and power into the multi-level perspective. Theor. Cult. Soc. 31, 21–40. doi: 10.1177/0263276414531627

Geels, F. W., and Schot, J. (2007). Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 36, 399–417. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003

Howlett, M. (2014). Why are policy innovations so rare and so often negative? Second-order policy design and institutionalized policy learning. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 16, 475–491. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.12.009

Institute for the Future (IFTF) (2011). Four Futures of Food: Global Food Outlook Alternative Scenarios Briefing (SR-1388). Available online at: https://legacy.iftf.org/uploads/media/IFTF_SR1388_GFOFuturesFood.pdf

Jasanoff, S., and Kim, S. H. (2015). Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226276663.001.0001

Johnson, B. D. (2011). Science Fiction Prototyping: Designing the Future with Science Fiction. San Rafael, CA: Morgan and Claypool Publishers. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-01796-4

Johnson, O. W., and Karlberg, L. (2017). Co-exploring the water–energy–food nexus: facilitating dialogue through participatory scenario building. Front. Environ. Sci. 5:24. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2017.00024

Kingdon, J. W. (2011). Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, 2nd Edn., updated. Harlow: Longman.

Marshall, H., Wilkins, K., and Bennett, L. (2023). Story thinking for technology foresight. Futures 146:103098. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2023.103098

Meadowcroft, J. (2009). What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long-term energy transitions. Policy Sci. 42, 323–340. doi: 10.1007/s11077-009-9097-z

Merrie, A. (2019). “Beyond prediction—radical ocean futures—a science fiction prototyping approach to imagining the future oceans,” in Predicting Future Oceans, eds. A. M. Cisneros-Montemayor, W. W. L. Cheung, and Y. Ota (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 519–527. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-817945-1.00047-2

Milkoreit, M. (2017). Imaginary politics: climate change and making the future. Elem. Sci. Anth. 5:62. doi: 10.1525/elementa.249

Mitchell, M., Lockwood, M., Moore, S. A., and Clement, S. (2015). Scenario analysis for biodiversity conservation: a social–ecological system approach in the Australian Alps. J. Environ. Manag. 150, 69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.11.013

Nobre, C. A., Sampaio, G., Borma, L. S., Castilla-Rubio, J. C., Silva, J. S., and Cardoso, M. (2016). Land-use and climate change risks in the Amazon and the need of a novel sustainable development paradigm. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 10759–10768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605516113

Ojoyi, M., Mutanga, O., Mwenge Kahinda, J., Odindi, J., and Abdel-Rahman, E. M. (2017). Scenario-based approach in dealing with climate change impacts in Central Tanzania. Futures 85, 30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2016.11.007

Pixley, K. V., Falck-Zepeda, J. B., Giller, K. E., Glenna, L. L., Gould, F., Mallory-Smith, C. A., et al. (2019). Genome editing, gene drives, and synthetic biology: Will they contribute to disease-resistant crops, and who will benefit? Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 57, 165–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080417-045954

Pulver, S., and VanDeveer, S. D. (2009). “Thinking about tomorrows”: scenarios, global environmental politics, and social science scholarship. Glob. Environ. Politics 9, 1–13. doi: 10.1162/glep.2009.9.2.1

Ramirez, R., and Selin, C. (2014). Plausibility and probability in scenario planning. Foresight 16, 54–74. doi: 10.1108/FS-08-2012-0061

Ramirez, R., and Wilkinson, A. (2016). Strategic Reframing: The Oxford Scenario Planning Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198745693.001.0001

Reed, M. S. (2008). Stakeholder participation for environmental management: a literature review. Biol. Conserv. 141, 2417–2431. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014

Rickards, L., Ison, R., Fünfgeld, H., and Wiseman, J. (2014). Opening and closing the future: climate change, adaptation, and scenario planning. Environ. Plann. C Gov. Policy 32, 587–602. doi: 10.1068/c3204ed

Rohrbeck, R., Battistella, C., and Huizingh, E. (2015). Corporate foresight: an emerging field with a rich tradition. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 101, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2015.11.002

Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1995). Scenario planning: a tool for strategic thinking. Sloan Manag. Rev. 36, 25–40.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Steiner, A., Aguilar, G., Bomba, K., Bonilla, J. P., Campbell, A., Echeverria, R., et al. (2020). Actions to Transform Food Systems Under Climate Change. Wageningen: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/108489 (Accessed November 8, 2025).

Stilgoe, J., Owen, R., and Macnaghten, P. (2013). Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 42, 1568–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008

Taylor, C. (2004). Modern Social Imaginaries. Durham: Duke University Press. doi: 10.1215/9780822385806

van Vuuren, D. P., Kok, M. T. J., Girod, B., Lucas, P. L., and de Vries, B. (2012). Scenarios in global environmental assessments: key characteristics and lessons for future use. Glob. Environ. Change 22, 884–895. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.06.001

Vertesi, J. (2019). “All these worlds are yours except …”: science fiction and folk fictions at NASA. Engaging Sci. Technol. Soc. 5, 135–159. doi: 10.17351/ests2019.315

Vervoort, J., and Gupta, A. (2018). Anticipating climate futures in a 1.5 °C era: the link between foresight and governance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 31, 104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.01.004

Wiebe, K., and Prager, S. (2021). Commentary on foresight and trade-off analysis for agriculture and food systems. Q Open 1:qoaa004. doi: 10.1093/qopen/qoaa004

Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., et al. (2019). Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 393, 447–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4

Keywords: scenario planning, foresight, sustainable food systems, food systems policy, participatory governance, plant-based diets, food system transformation, policy innovation

Citation: Zhou Y and Razzaq A (2025) What if? Integrating scenarios and fiction in food systems policy and governance. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1619641. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1619641

Received: 28 April 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025;

Accepted: 10 November 2025; Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Farhad Zulfiqar, Sultan Qaboos University, OmanReviewed by:

Gemma Cobb, Griffith University, AustraliaCopyright © 2025 Zhou and Razzaq. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amar Razzaq, YW1hci5yYXp6YXFAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=

Yewang Zhou

Yewang Zhou Amar Razzaq

Amar Razzaq