Abstract

There are many features of youth sport that can make it exciting and motivating or, alternatively, make it dull, stressful, or otherwise uninviting. Among those features are the participants themselves. When young athletes sign up for a sport, opt to stay with a particular team, invest time and energy into practicing, or consider their competitive successes and failures, their peers (those of similar age, standing, and power) often play a part. Teammates are probably the most important peers in shaping youth sport choices and experiences, but other peers at school and elsewhere can also influence young athletes. In this article, we describe three ways that peers matter in youth sport. We argue that the quality of young athletes’ sport experiences is tied to specific friendships, broader acceptance by peers, and how athletes compare themselves to their peers. These aspects of peer relationships play important roles in shaping athlete motivation and performance.

Introduction: Peers and the Quality of Youth Sport Experiences

Most young people play a sport at some point in their childhood, with many trying a range of sports and staying involved with sports over several years. Organized sports usually take place in community settings, private clubs, or in schools. There are also informal opportunities in neighborhoods, parks, schoolyards, and other places where young people gather with minimal adult supervision. Across these settings, young people participate for a variety of reasons, including the opportunity to be with peers and make friends. It is important to consider peers when seeking to understand the quality of youth sport experiences.

Often, sport scientists and others focus exclusively on how an athlete performs in sport, but ultimately the quality of a sport experience is more than just personal bests, winning, and losing. Quality sport experiences bring enjoyment, the opportunity to learn physical and life skills, and the chance to test oneself and perform. Sport experiences also bring various opportunities to be social. Peers can contribute to a good-quality sport experience. Therefore, the study of peers in sport can help us better understand how to create sport experiences that are attractive and fulfilling. When we use the term peers, we are often referring to people of about the same age, such as schoolmates, teammates, or others with roughly equal standing and power [1]. There are other ways to think of peers—for example, all orange belts in a karate dojo might be considered peers because of their shared level of accomplishment. In this case, both youth and adults could be considered part of a peer group. However, when studying children or adolescents in sport, we typically view peers to mean those of about the same age or grade who share sport and non-sport experiences in common.

How might peers influence sport experiences? Consider Olivia, who is thinking about joining the track and field team at her middle school. She has two good friends in her neighborhood, Leslie and Maya, with whom she plays outside, rides the bus to school, and otherwise spends time. Leslie and Maya are joining the team, and are encouraging Olivia to join too. Olivia has tried a variety of sports but has not stuck with them. In basketball, she felt excluded because she had a late start in the sport compared to her teammates. She had difficulty breaking into the social circle of the team. In field hockey, she got along well with her teammates, but viewed herself as less skilled than the others. She sometimes felt embarrassed about her play, especially when peers not on her team were spectating, and she received limited playing time. She tried swimming, but the way practices were structured left little time to interact with friends—she wanted more than just a focus on performance. Yet, despite these past experiences, she likes the idea of joining track and field. She can be with Leslie and Maya, there are no cuts from the team (low pressure), lots of others participate, everyone gets the chance to compete, and the team is recognized at the spring school assembly.

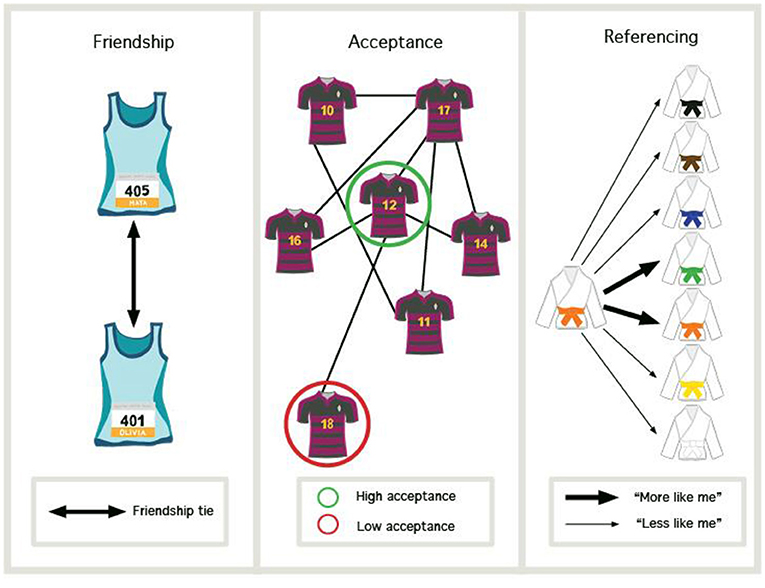

Olivia’s experiences and current decision-making are influenced strongly by her peers. In the sections below, we discuss three ways that peers matter in youth sport (Figure 1). Studying this topic can help us make sport more engaging and meaningful to young people. This is especially important information for adults, because they are often in charge of sport experiences, but are not a part of the peer-to-peer interactions.

- Figure 1 - Three Ways that Peers Matter in Youth Sport.

- Friendships with specific peers, general acceptance by the peer group, and how athletes compare themselves to (reference) peers are uniquely related to the quality of youth sport experiences.

Friendships: One-on-One Peer Relationships

The opportunity to be with friends motivates young people to participate in sport. So, friendships are one important way that peers matter in sport [1]. Friendships are close relationships that develop on a one-on-one level. When a young athlete participates in a sport with a friend or several friends, there is great potential for the sport to be fun and personally meaningful. Also, by participating in sport together, friends have an opportunity to get to know one another better and to have shared experiences. Friendships can enhance sport experiences and sport experiences can enhance friendships.

Interviews and surveys of youth sport participants ages 8–16 years have highlighted both positive and negative features of sport friendships and defined six key features of sport friendship quality [2, 3] (Figure 2). High-quality sport friendships are supportive and encouraging, loyal and close, involve having things in common, are highly enjoyable, experience occasional conflicts, and effectively resolve any conflicts that arise. Research shows that the more highly young athletes rate their sport friendships in these ways, the more likely they are to enjoy their participation, believe that they are competent at sport, and feel good about themselves. Athletes who rate their sport friendships more highly are also more motivated to participate because they want to, instead of feeling that they have to—which is a healthier form of motivation [1, 4].

- Figure 2 - Six Core Features of Sport Friendship.

- When sport friends are supportive, loyal, have things in common, enjoy being together, and manage conflict effectively, the stage is set for a good-quality sport experience.

Acceptance by Peers

Young people generally want to be accepted by others their age. Those who are accepted feel meaningfully connected to others, while those with low acceptance may feel isolated. Through involvement in sport, athletes might try to achieve a sense of peer acceptance and belonging among teammates, or try to gain acceptance or popularity with other classmates and peers. Said another way, young athletes’ interest in sport participation is tied to social goals as well as competitive goals [5]. Research shows that young people believe that being good at sport is a way to be popular with peers [1]. Also, when young people achieve a sense of acceptance or belonging in sport, there are benefits to their motivation and well-being [1, 4]. Feeling accepted can encourage continued involvement in sport and also benefit a young athlete’s social development. On the other hand, sport involvement is not as motivating or beneficial when a young participant is not accepted by teammates or is on a team with a lot of conflict.

Peer Referencing

A third way that peers matter in sport is that they can be a source of information about how good athletes are at sport and about which attitudes and behaviors are valued. Said another way, peers often serve as a point of reference for one another. Peer referencing is a common mental process that enables us to gauge our abilities and how we fit into a social situation. In sport, peer referencing relies heavily on peer comparisons, particularly in later childhood [4]. Athletes develop an interest in how they compare with others, and this can motivate or discourage them depending on their conclusions. For example, young athletes might compare themselves to others in the karate dojo and aspire to move to the next belt level. Alternatively, they might feel discouraged by not being as accomplished as others or believe that their progress is slow compared to others.

The way comparisons motivate or discourage young athletes depends on what is rewarded and considered “success” in sport. This is referred to as the peer-created motivational climate [6]. Peers may create a sport climate that strongly emphasizes outcompeting teammates and judges who is the “best.” Alternatively, peers might create a sport climate that reinforces putting in strong effort, developing skills, and striving for improvement. Less skilled athletes can struggle with their motivation when their peers are too much like the first group. However, a less skilled athlete in a climate that promotes effort and improvement can remain strongly motivated.

Putting It All Together

The three ways peers matter in sport—friendships, acceptance, and peer referencing—are not independent of one another. Peer referencing occurs in situations that contain friends and teammates, who may be accepting or not. For example, David’s soccer teammates may not warmly accept him and they may be overly competitive with one another, yet his long-time best friend is on the team. Having such a good friend on the team may make David’s participation enjoyable and motivating in spite of his challenges with other teammates. Research supports that challenges with peers in sport can be overcome when some peer factors are positive; however, an athlete will be most motivated when all peer factors are going well [7]. That is, when an athlete has quality friendships in sport, is well accepted by teammates, views oneself as comparing well to others, and is comfortable with the peer-created motivational climate, the athlete will probably have positive experiences in sport. Of course, peer relationships, motivation, and other experiences in sport are connected in complex ways. Future research is needed to more clearly understand when and how peers are most impactful, for good or bad, in youth sport.

To ensure that Olivia, David, and other young athletes have positive experiences with their peers in sport, there are a few things that adults and athletes themselves can do [8]. For example, it is important to allow time during practice and other team gatherings for athletes to be social and develop their friendships. Similarly, it is important for young people to have time to enjoy playing sports informally, without too much supervision from adults. When focus is placed exclusively on organized sport and high performance and not on the broader interests and needs of young people, athletes can struggle with their motivation. Also, coaches can encourage teammates to emphasize effort, improvement, and teamwork over competing with one another. Reinforcing these qualities often results in improvements in skills and performance, while keeping a positive environment. Finally, because peers can have conflicts or will sometimes exclude one another, it is important for coaches to learn how to constructively manage conflicts and how to make sure that everyone on the team is feels included. This can ensure that every member of the team feels valued and has a quality youth sport experience.

Glossary

Peers: ↑ Individuals of about the same age, such as schoolmates, teammates, or others with roughly equal standing and power.

Friendships: ↑ Close relationships that develop on a one-on-one level.

Peer Acceptance: ↑ The degree to which one is accepted by or popular within a group of peers.

Peer Referencing: ↑ A mental process where individuals compare themselves to others with respect to skills, attitudes, and values.

Peer-Created Motivational Climate: ↑ How a peer group defines and reinforces what is considered successful. Some groups emphasize performance outcomes and others emphasize effort and improvement.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emma Smith for helpful feedback on an early draft of this article.

References

[1] ↑ Smith, A. L., Mellano, K. T., and Ullrich-French, S. 2019. “Peers and psychological experiences in physical activity settings,” in Advances in Sport and Exercise Psychology, 4th Edn, eds T. S. Horn and A. L. Smith (Champaign: Human Kinetics). p. 133–50.

[2] ↑ Weiss, M. R., Smith, A. L., and Theeboom, M. 1996. “That’s what friends are for:” children’s and teenagers’ perceptions of peer relationships in the sport domain. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 18:347–79. doi: 10.1123/jsep.18.4.347

[3] ↑ Weiss, M. R., and Smith, A. L. 1999. Quality of youth sport friendships: Measurement development and validation. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 21:145–66. doi: 10.1123/jsep.21.2.145

[4] ↑ Weiss, M. R. 2019. Youth sport motivation and participation: Paradigms, perspectives, and practicalities. Kinesiol Rev. 8:162–70. doi: 10.1123/kr.2019-0014

[5] ↑ Allen, J. B. 2003. Social motivation in youth sport. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 25:551–67. doi: 10.1123/jsep.25.4.551

[6] ↑ Ntoumanis, N., Vazou, S., and Duda, J. L. “Peer-created motivational climate,” in Social Psychology in Sport, eds S. Jowett and D. Lavallee (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics). p. 145–56.

[7] ↑ Smith, A. L., Ullrich-French, S., Walker, E., and Hurley, K. S. 2006. Peer relationship profiles and motivation in youth sport. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 28:362–82. doi: 10.1123/jsep.28.3.362

[8] ↑ Smith, A. L., and Delli Paoli, A. G. 2018. “Fostering adaptive peer relationships in youth sport,” in Sport Psychology for Young Athletes, eds C. J. Knight, C. G. Harwood, and D. R. Gould (New York, NY: Routledge). p. 196–205.