- 1Division of Pediatric Urology, Department of Urology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 2Division of Pediatric Urology, Department of Urology, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Morgantown, WV, United States

Purpose: Classic bladder exstrophy (CBE), is a complex congenital malformation affecting formation of the lower abdominal wall and bladder. This study evaluates the readability of common online resources regarding CBE and its treatment. We hypothesize that high levels of reading comprehension are reflected in these resources, which may not be suitable to the general population for understanding this condition.

Methods: The search terms “bladder exstrophy” and “bladder exstrophy treatment” were reviewed on the Google search engine. The first 100 search results for each search query were collected. The readability of each webpage was assessed using a combination of four independent validated formulae: the Gunning-Fog index (GFI), SMOG grade (Simple Measure of Gobbledygook), Dale-Chall index (DCI), and the Flesch-Kincaid grade (FKG).

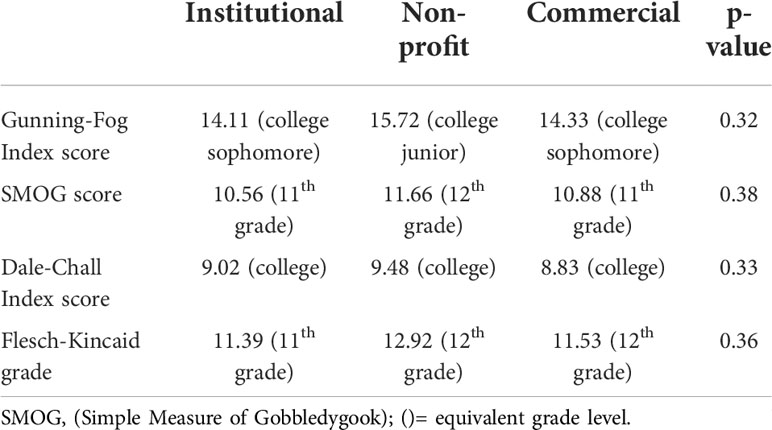

Results: A total of 200 search results were examined using the two search queries, yielding 72 unique webpages that fit the inclusionary criteria. The mean readability scores across all websites were a GFI of 14.3, SMOG score of 10, DCI of 9.06, and a FKG of 11.6. These scores correlate to adjusted grade levels of college sophomore, 11th grade, college, and 11th grade respectively. There was no significant difference of readability between website categories across GFI (p = 0.32), SMOG (p = 0.38), DCI (p = 0.33), and FKG (p = 0.36).

Conclusion: This study demonstrates that online health information regarding CBE and its treatment is written at least the 11th grade reading level or above. This highlights the necessity to simplify online resources pertaining to CBE.

Introduction

Classic bladder exstrophy (CBE) is a rare congenital abnormality that presents with defects of the bladder, abdominal wall, pelvic floor, and bony pelvis. It is the most common variant of the exstrophy-epispadias complex (EEC) with an estimated incidence of 2.2 cases per 100,00 live births (1). Individuals born with bladder exstrophy suffer from long term morbidity of their condition which is not truly resolved even with the best of reconstructive results.

From birth, caregivers are inundated with information about this unfamiliar disease to enhance their understanding of their child and improve shared decision-making. Unfortunately, as many as ninety million adults are estimated to have low health literacy (HL) in the United States (2). Known risk factors include low socioeconomic status, limited English-language proficiency, and certain ethnic groups (3). The impact of poor caregiver HL on child health outcomes is well documented as an inciting factor for drug dosing errors, frequently missed appointments, and poor glycemic control in diabetic children (4). An estimated 98% of parents have used the Internet to search for information regarding their child’s health (5). While caregivers report holding academic websites in higher regard than commercial websites, they often find them to be “too scientific” or difficult to understand (6). This can lead to caregivers relying on commercial websites instead as they seem comprehensive yet convenient (6). In an analysis of the quality of health websites’ information, commercial websites were associated with significantly greater use of biased language and they received inferior content quality scores (7).

The average American adult reads at an 8th grade level, with nearly 20% of adults being unable to understand texts at a 4th grade level (8, 9). International literacy, as assessed by the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), demonstrated that the US scored a literacy score of 272 above the international average of 267 (10). Critically, the average American still falls behind compared to other countries such as Japan (296) and Finland (288) (10). As such, the American Medical Association (AMA) and National Institute of Health (NIH) recommend that all medical information materials should be no greater than a 6th or 7th-8th grade reading level, respectively (11, 12). In this study, the readability of common informational websites available to the general public regarding CBE and its treatment are examined. We hypothesize that the majority of online information on the topic of CBE and its treatment, is written beyond the 6th grade reading level and thus incomprehensible by a significant number of patients.

Methods

The search terms “bladder exstrophy” and “bladder exstrophy treatment” were reviewed on the Google search engine (https://google.com). The first 100 search results for each search were collected on June 6, 2022 using an incognito window and with the disabling of “cookies”. Each website was classified into one of three categories: institutional (.edu/gov), commercial (.com), and non-profit/charity (.org). Webpages were excluded if they were duplicate websites, videos, research or news articles, and/or paid advertisements. Websites requiring payment or log-in information, such as UpToDate, were also excluded from review. Websites required a minimum of 200 words to accurately evaluate readability. IRB approval was deemed not necessary for this study.

The readability of each webpage was assessed using a combination of four independent validated formulae: the Gunning-Fog index (GFI), SMOG grade (Simple Measure of Gobbledygook), Dale-Chall index (DCI), and the Flesch-Kincaid grade (FKG). An online tool (readabilityformulas.com) was used to score each portion of text by copying the text from each page into the text box function. The GFI evaluates text based on average sentence length and number of “complex” words, those containing three or more syllables (13). This is similar to the SMOG index, which derives its score from the number of words with greater than three syllables (13). The FKG also bases its score based on sentence length as well as multisyllabic words (13). The scores of the GFI, SMOG, and FKG indicate the U.S. grade level required to understand the content (a score of 11.1 is understood by an 11th grade student). The DCI measures sentence length and examines “difficult” words, those that are outside a layperson’s familiarity. A score of 6.0-6.9 resembles a 7th/8th grade level, 7.0-7.9 resembles a 9th/10th grade level, 8.0-8.9 resembles a 11th/12th grade level, and a score above 9 indicates a college level.

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the readability of each website category with each validated formula. A p-value of <0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. Analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel.

Results

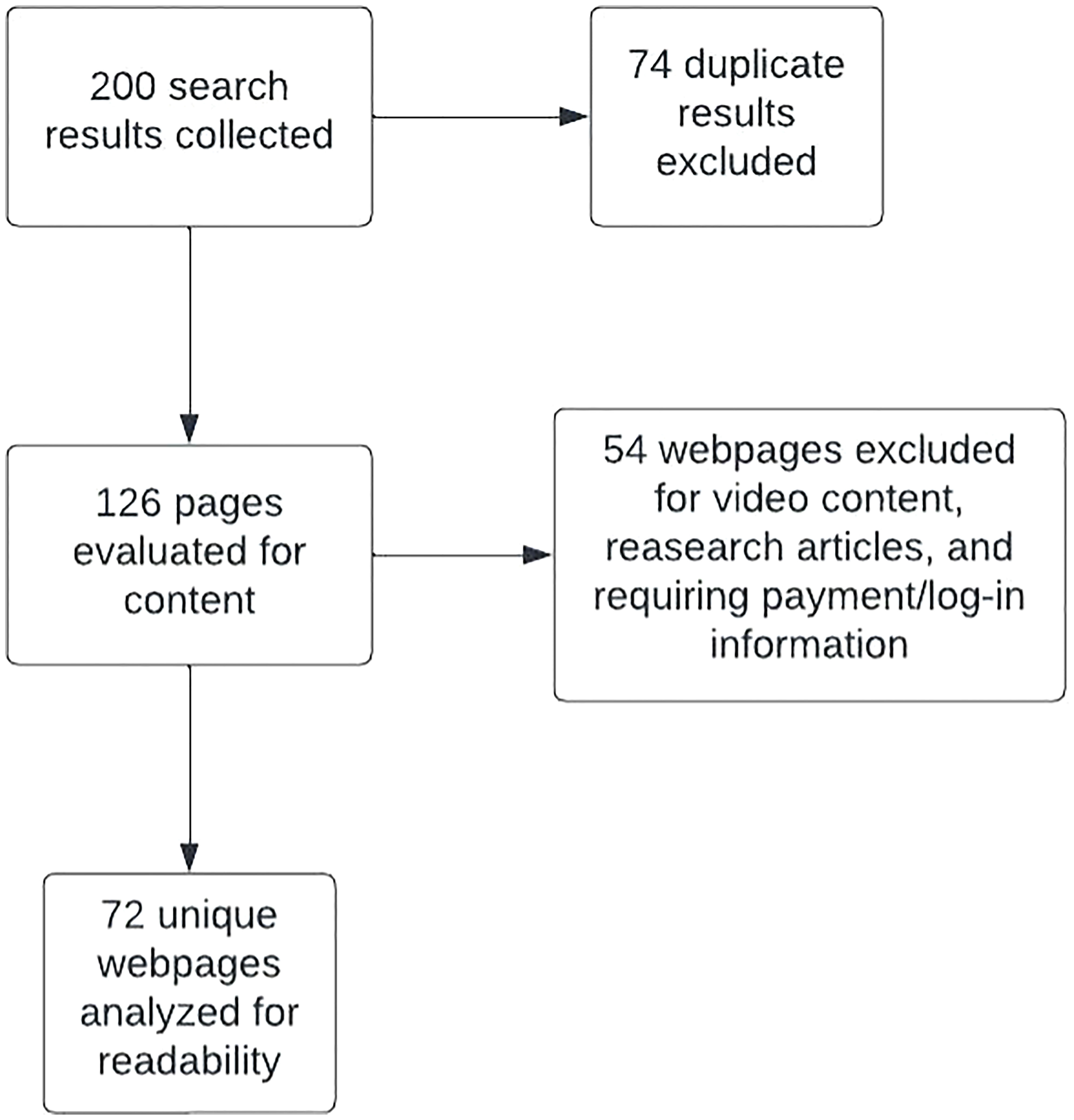

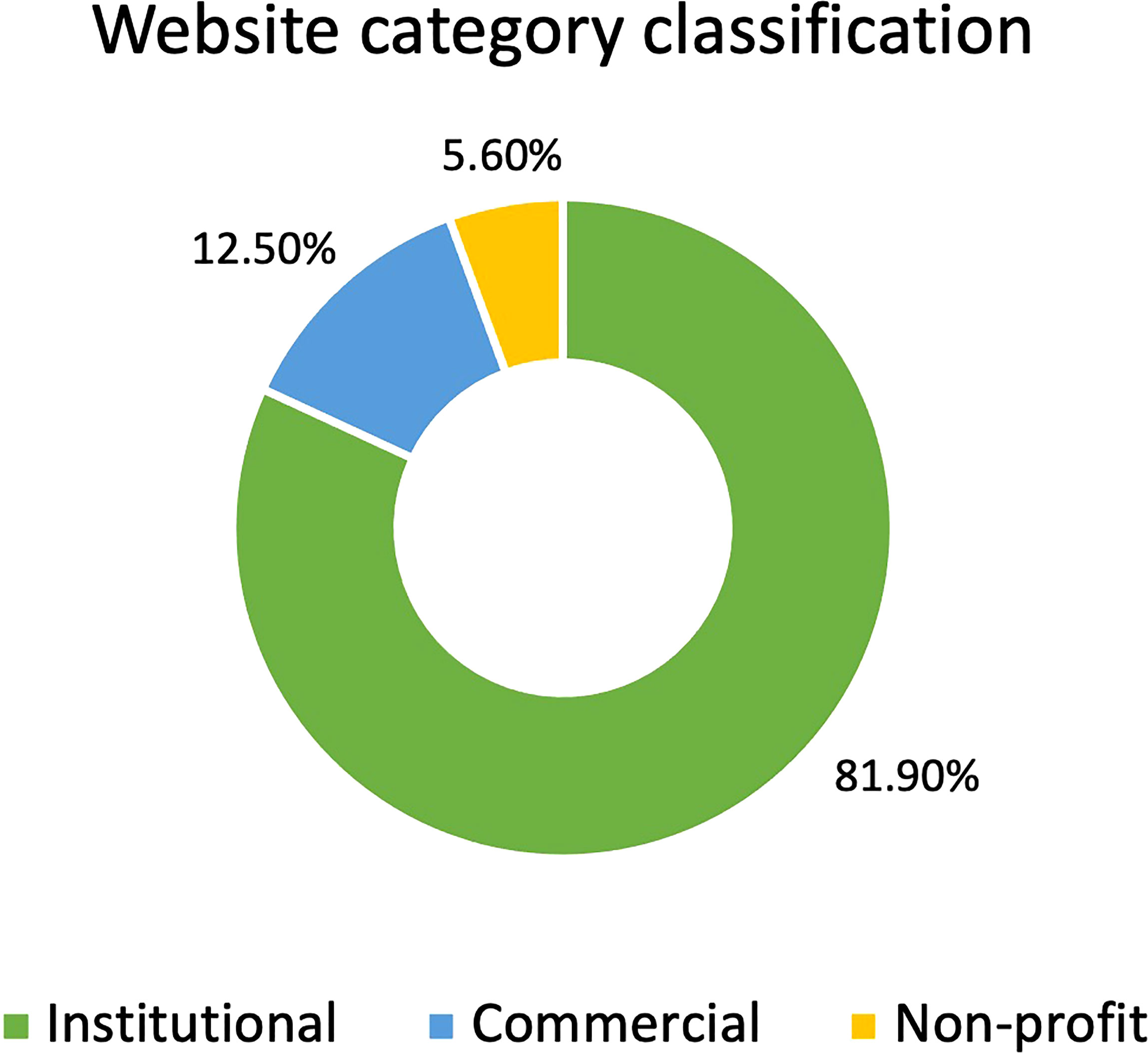

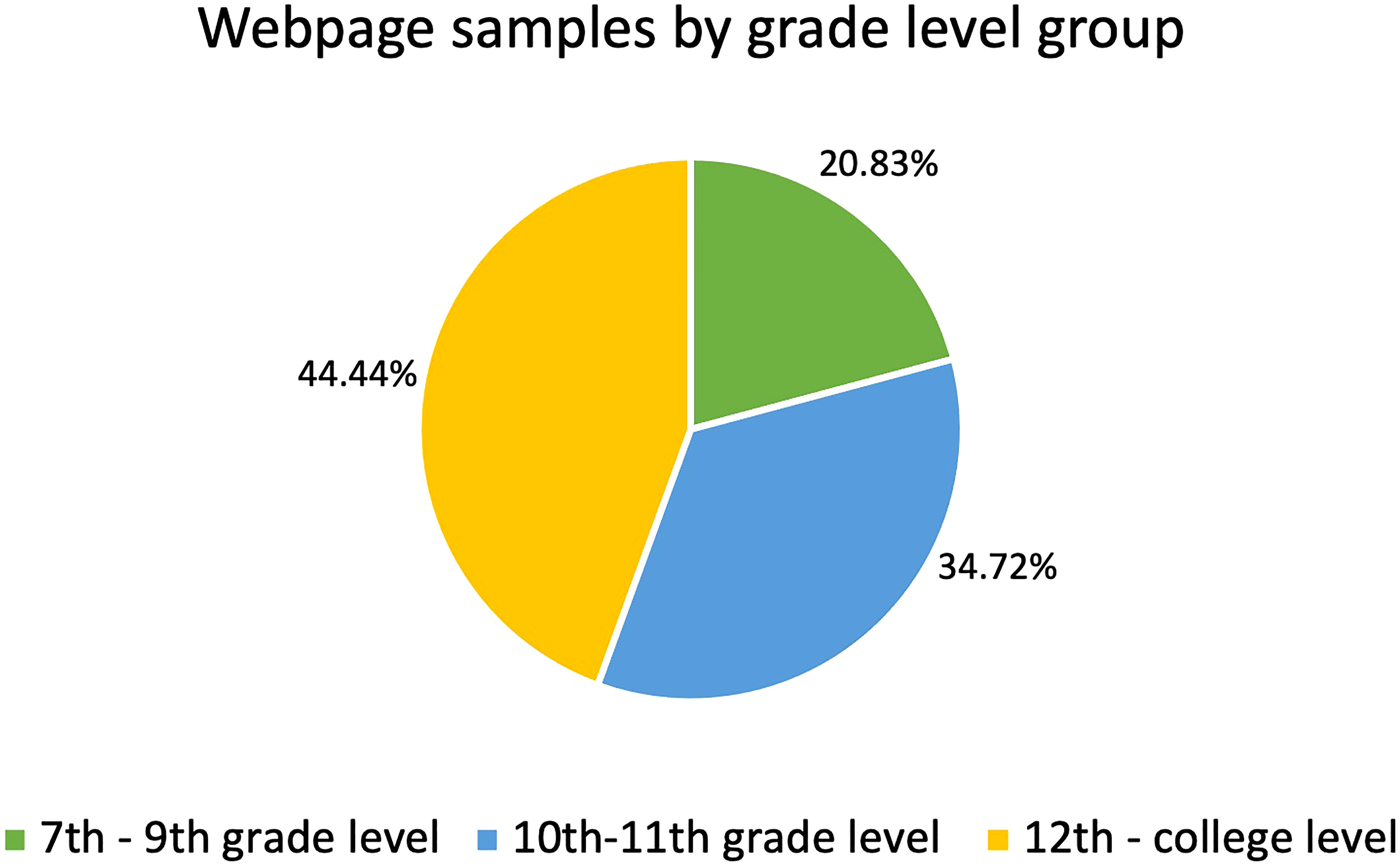

A total of 200 search results were examined using the two search queries, yielding 72 unique webpages that fit the inclusionary criteria (Figure 1). The majority of webpages were categorized as institutional websites (n = 59, 81.9%), with the remaining categorized as commercial (n = 9, 12.5%) and non-profit (n = 4, 5.6%) websites (Figure 2). The mean readability scores across all websites were a GFI of 14.3 (SD = 2.96, range: 9.1-24.1, variance = 8.77), SMOG score of 10.71 (SD = 2.22, range: 6.8-19.3, variance = 4.93), DCI of 9.06 (SD = 0.92, range: 7.3-11.7, variance = 0.84), and a FKG of 11.6 (SD = 2.96, range: 6.9-23.4, variance = 8.75). These scores correlate to adjusted grade levels of college sophomore, 11th grade, college, and 11th grade, respectively. Webpages were further classified into grade level groups of 7th – 9th grade, 10th – 11th, and 12th and college level based on SMOG score (Figure 3).

The data was then analyzed to compare the readability between different website categories (Table 1). Surprisingly, there were no significant differences between website categories across GFI (p = 0.32), SMOG (p = 0.38), DCI (p = 0.33), and FKG (p = 0.36).

Discussion

CBE is a rare condition with minimal awareness among the general public. Historically, caregivers received all information from their medical team, however, since the widespread adoption of the Internet, caregivers have increasingly relied on online-search engines for health information and support. Evaluation of the effectiveness of this online platform for online patient information has been of great interest in several areas of medicine to ensure patient families can best understand their diagnosis. Indeed, this challenge is not unique to the information on CBE nor that of urology, it is endemic to all fields of medicine. Countless studies have been published evaluating the readability of patient education materials online across multiple specialties, and the trend for information to be above the recommended reading level is overwhelming (14–26).

Data derived from our online query yielded a composite readability level far more advanced than the recommended 6th and 7th-8th grade reading level set by the AMA and NIH, respectively. Across the four different formulas used to analyze the text, the lowest average score was equivalent to an 11th grade reading level. No websites achieved the recommended 6th grade level. However, two institutional/non-profit websites (Indiana Department of Health and Cedars-Sinai Hospital) were found to be a 7th grade reading level.

Regarding the analysis of website categories and readability, we find the meager sample size of non-profit and commercial websites as a potential source of bias capable of skewing results. Several similar papers assessing the readability of patient health information on various urologic pathology have found no clear trend between website type and readability (14–18). Some have found commercial sources to have simpler text, while others have associated institutional webpages with more advanced levels of readability. Nevertheless, these data underscore the pressing need for academic and institutional groups to ensure their online information is comprehensible for all patients. The rare nature of CBE is likely the impetus for why most online information available to patients comes from institutional sources. For instance, a similar study on the readability of hypospadias information, a relatively common malformation, shows a stark contrast with nearly 42% arising from non-institutional sources (14).

During our webpage analysis, we observed certain webpages had nearly identical text, figures, and readability scores. These pages had all sourced their content from the Mayo Clinic Patient Care and Health Information page on bladder exstrophy. Approximately 8 webpages utilized some or all of their content from the Mayo Clinic page, which had an estimated 10th grade reading level which likely influenced our analysis. Nevertheless, these websites were included in the assessment as these webpages were likely to be found by patients seeking information.

This study is not without its limitations. Readability scores, while objective and easy to use, are an imperfect measure to describe comprehensibility of a text. Readability scores place more emphasis on complex word usage, number of syllables, and total sentence word count. Comprehension could be better evaluated with structured one-on-one interviews in conjunction with objective readability formulas. Additionally, the layout of text and figures used were not included in the evaluation of readability. We used the Google search engine to perform all searches, despite the fact that some patients utilize less common search engines like Bing. We felt that the first 100 webpages would have very high concordance with Bing search engine results. Another limitation of the utilization of the Google search engine is its personalized results, which can vary search results for each user based on their Google account, geographic location, and search history (27). Although this effect can be reduced, with the use of an incognito window and disabling of “cookies,” the effect cannot be completely expunged.

This study demonstrates that online health information about CBE is written, on average, at the 11th grade level and above, considerably higher than the recommended level of 6th grade. This highlights the necessity for hospitals and health care systems to strive to make their online information accessible and comprehensible.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

AH and CM conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. ZW and AG conceptualized and designed the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript. JG and CC conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated, and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr. Gearhart for valuable discussions and feedback.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

CBE, Classic bladder exstrophy; GFI, Gunning-Fog Index; SMOG, Simple Measure of Gobbledygook; DCI, Dale-Chall Index; FKG, Flesch-Kincaid Grade; EEC, Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex; HL, Health Literacy; PIAAC, Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies; AMA, American Medical Association; NIH, National Institute of Health; ANOVA, one-way analysis of variance.

References

1. Siffel C, Correa A, Amar E, Bakker MK, Bermejo-Sánchez E, Bianca S, et al. Bladder exstrophy: an epidemiologic study from the international clearinghouse for birth defects surveillance and research, and an overview of the literature. Am J Med Genet Part C: Semin Med Genet (2011) 157C(4):321–32. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30316

2. Kampouroglou G, Velonaki VS, Pavlopoulou ID, Fildissis G, Tsoumakas K. Parental health literacy in the pediatric surgical setting. Chirurgia (Bucur) (2019) 114:326–0. doi: 10.21614/chirurgia.114.3.326

3. Kutner M, Greenburg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The health literacy of america's adults: Results from the 2003 national assessment of adult literacy. NCES 2006-483. Natl Center Educ statistics. (2006) 9–14. accessed at https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf

4. Morrison AK, Glick A, Yin HS. Health literacy: implications for child health. Pediatr Rev (2019) 40(6):263–77. doi: 10.1542/pir.2018-0027

5. Pehora C, Gajaria N, Stoute M, Fracassa S, Serebale-O'Sullivan R, Matava CT. Are parents getting it right? a survey of parents’ internet use for children’s health care information. Interactive J Med Res (2015) 4(2):e3790. doi: 10.2196/ijmr.3790

6. Bernhardt JM, Felter EM. Online pediatric information seeking among mothers of young children: results from a qualitative study using focus groups. J Med Internet Res (2004) 6(1):e36. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.1.e7

7. Li JZ, Kong T, Killow V, Wang L, Kobes K, Tekian A, et al. Quality assessment of online resources for the most common cancers. J Cancer Education (2021) 8:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s13187-021-02075-2

8. Eltorai AE, Ghanian S, Adams CA Jr., Born CT, Daniels AH. Readability of patient education materials on the american association for surgery of trauma website. Arch Trauma Res (2014) 3(2):1–4. doi: 10.5812/atr.18161

9. Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching patients with low literacy skills (1996), 2 (Philadelphia, PA: Lipincott Williams and Wilkins).

10. NCES Organization. Adult literacy. U.S. Department of Education (2017). Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics. (Washington D.C.).

11. Weis BD. Health literacy: a manual for clinicians. Washington D.C., Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association (2003). (Chicago, IL).

12. National Institute of Health. How to write easy-to-read health materials. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20170121030554/https://medlineplus.gov/etr.html (Accessed June 30th, 2022).

13. Ley P, Florio T. The use of readability formulas in health care. Psychology Health Med (1996) 1(1):7–28. doi: 10.1080/13548509608400003

14. Cisu TI, Mingin GC, Baskin LS. An evaluation of the readability, quality, and accuracy of online health information regarding the treatment of hypospadias. J Pediatr Urol (2019) 15(1):40–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.08.020

15. Werner Z, Trump T, Zaslau S, Shapiro R. Assessing comprehension of online information in the united states for third-line treatment of overactive bladder. Int Urogynecology J (2022) 13:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00192-022-05218-1

16. Koo K, Shee K, Yap RL. Readability analysis of online health information about overactive bladder. Neurourology Urodynamics (2017) 36(7):1782–7. doi: 10.1002/nau.23176

17. Sare A, Patel A, Kothari P, Kumar A, Patel N, Shukla PA. Readability assessment of Internet-based patient education materials related to treatment options for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Acad Radiol (2020) 27(11):1549–54. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2019.11.020

18. Colaco M, Svider PF, Agarwal N, Eloy JA, Jackson IM. Readability assessment of online urology patient education materials. J Urol (2013) 189(3):1048–52. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.255

19. Doinn TÓVerifytat, Broderick JM, Abdelhalim MM, Quinlan JF. Readability of patient educational materials in pediatric orthopaedics. JBJS (2021) 103(12):e47. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.01347

20. Ballestas SA, Soriano RM, Sethna AB. Readability assessment of online rhytidectomy patient information. Plast Surg Nursing (2020) 40(3):145–9. doi: 10.1097/PSN.0000000000000311

21. Sharma AN, Martin B, Shive M, Zachary CB. The readability of online patient information about laser resurfacing therapy. Dermatol Online J (2020) 26(4):1–8. doi: 10.5070/D3264048343

22. Duong PT, Moy MP, Simeone FJ, Chang CY, Wong TT. Assessing the readability of patient-targeted online information on musculoskeletal radiology procedures. Skeletal Radiol (2021) 50(7):1379–87. doi: 10.1007/s00256-020-03562-1

23. Alejos D, Tregubenko P, Jayarangaiah A, Steinberg L, Kumar A. We need to do better: readability analysis of online patient information on cancer survivorship and fertility preservation. J Cancer Policy (2021) 28:100276. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpo.2021.100276

24. Pass JH, Patel AH, Stuart S, Barnacle AM, Patel PA. Quality and readability of online patient information regarding sclerotherapy for venous malformations. Pediatr Radiol (2018) 48(5):708–14. doi: 10.1007/s00247-018-4074-3

25. Nawaz MS, McDermott LE, Thor S. The readability of patient education materials pertaining to gastrointestinal procedures. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol (2021) 2021:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2021/7532905

26. Ahmadi O, Louw J, Leinonen H, Gan PY. Glioblastoma: assessment of the readability and reliability of online information. Br J Neurosurgery (2021) 35(5):551–4. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2021.1905772

Keywords: exstrophy, readability, online health information, exstrophy treatment, classic bladder exstrophy

Citation: Haffar A, Morrill C, Garcia A, Werner Z, Crigger C and Gearhart JP (2022) Complicating the already complex? Readability scores in bladder exstrophy and its treatment. Front. Urol. 2:1044639. doi: 10.3389/fruro.2022.1044639

Received: 15 September 2022; Accepted: 26 October 2022;

Published: 16 November 2022.

Edited by:

Kiarash Taghavi, Monash Children’s Hospital, AustraliaReviewed by:

Moneer K Hanna, Cornell University, United StatesYuval Bar-Yosef, Dana-Dwek Children’s Hospital, Israel

Copyright © 2022 Haffar, Morrill, Garcia, Werner, Crigger and Gearhart. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ahmad Haffar, aihaffar@mix.wvu.edu

Ahmad Haffar

Ahmad Haffar Christian Morrill1

Christian Morrill1 John P. Gearhart

John P. Gearhart