Abstract

Inhibitory control is a core cognitive function that is primarily associated with activation in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and is the cognitive function that inhibits impulses, thoughts, and suppresses irrelevant information to an identified goal or task. Prior research suggests that bilingualism may affect brain activity related to inhibitory control, yet few studies have compared functional activity between monolingual and bilingual children. The current study used functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) to examine region of interest comparisons and task-state functional connectivity across the PFC during an interference suppression Simon task with 13 bilingual (East Asian or Ibero-romance paired with English) and 13 age-matched English monolingual preschoolers. Results showed no significant differences in behavioral measures of interference suppression. However, bilingual preschoolers showed lower oxygenated hemoglobin activation and more localized patterns of connectivity within the PFC, suggesting more efficient processing during suppression compared to their monolingual peers. This may reflect the bilingual experience of regularly suppressing their second language when not in use, thus facilitating neural efficiency. These findings contribute to the growing body of literature on bilingual cognitive development suggesting that functional connectivity during executive function may differ in bilingual children, even at a young age, despite no observable behavioral differences. This highlights the importance of integrating neuroimaging with behavioral data to gain a more comprehensive understanding of bilingual cognitive development.

Introduction

Executive Function (EF) refers to a set of cognitive processes that enable goal-directed behavior and are primarily supported by the prefrontal cortex (Jones and Graff-Radford, 2021). Inhibitory control falls under EF and refers to the ability to suppress irrelevant thoughts or actions (Rothbart and Posner, 1985). Inhibitory control undergoes rapid development during early childhood (3–5 years old, Moriguchi, 2014, Zelazo and Carlson, 2012) and is crucial for later academic achievement, emotion regulation, and social success (Anthony and Ogg, 2020; Beisly and Jeon, 2024; Sasser et al., 2015). A longitudinal study further supports the importance of inhibitory control over the lifespan, finding that high self-control skills between ages 3 and 11 resulted in significantly better health, higher incomes, and lower rates of criminal conviction in adulthood (Moffitt et al., 2011).

Bilingualism has been proposed as one factor that may influence the development of EF through neural adaptation. Bialystok (2024) proposes that bilingualism facilitates “adaptation,” where neural networks are modified through experience, potentially enhancing attention skills across multiple domains. Exposure to multiple languages early in development may improve attentional control by requiring children to listen to and process multiple linguistic inputs (Bialystok and Craik, 2022). This enhanced attention control may give bilingual children an advantage on complex tasks that demand high levels of sustained attention (Bialystok, 2024). Despite being related constructs, findings of a bilingual advantage have typically been shown with tasks that require interference suppression as opposed to response inhibition (e.g., Simon and Stroop tasks; Martin-Rhee and Bialystok, 2008; Nayak et al., 2020). However, while some studies support a bilingual advantage in interference suppression, findings remain mixed, with almost twice as many studies documenting an advantage in older children (ages 6–12) than in younger children (Hilchey and Klein, 2011; Planckaert et al., 2023).

These inconsistencies in behavioral findings have led some researchers to suggest that cultural and socioeconomic status (SES) factors such as education, occupation, and income may confound the results (Paap, 2022). A meta-analytic review revealed only a small effect of bilingualism on EF, which disappeared once they adjusted for publication bias (Lowe et al., 2021). However, a Bayesian inference analysis found that bilingual children outperform monolinguals in EF “far more often than chance,” even when controlling for publication bias, year, sample size, and task type (Yurtsever et al., 2023). These conflicting findings highlight the need to investigate bilingualism’s effect using neuroimaging techniques rather than relying solely on behavioral measures (Pliatsikas, 2024). The use of neuroimaging techniques can provide additional information on the underlying cognitive functions that may not be adequately captured by behavioral studies (Morita et al., 2016).

Neuroscience research suggests that as inhibitory control matures, neural activation becomes more specialized and efficient, shifting from broad, global activation to a more localized pattern in the prefrontal cortex (Fiske and Holmboe, 2019; Hwang et al., 2010). This aligns with the neural efficiency hypothesis, which posits that greater proficiency in cognitive tasks becomes more automated by adapting to the demands, thus requiring only specific brain regions and less global activation (Debarnot et al., 2014). This further aligns with the principle of efficient coding which states that the brain works to transmit the maximum amount of information in the way that is most metabolically efficient, leading to reduced neural load for behavioral performance (Zhou et al., 2022). Given this framework, examining brain activity can provide deeper insight into how bilingualism influences inhibitory control at the neural level.

Evidence suggests that bilinguals may develop more efficient attentional control, particularly in tasks requiring interference suppression, where irrelevant information must be ignored. For example, in a response inhibition task, Mehnert et al. (2013) found increased connectivity for children ages 4–6 in the bilateral frontal and parietal cortices during both response and inhibition trials using functional near-infrared neuroimaging (fNIRS). Conversely, the adult participants activated only during the inhibition trials and only within the right frontal and parietal cortex. Their results align with the neural efficiency hypothesis, suggesting that younger children, who have less practice with inhibition, recruit neural networks that are broader and not fully specialized compared with adults who have had more practice and are more proficient. Bilingualism, by providing additional practice in attentional control, may accelerate this neural adaption process, leading to less global activation and greater efficiency during inhibition, even in young children (Li et al., 2023).

Bilingualism has been associated with structural brain changes in both grey and white matter, particularly as second language proficiency increases (García-Pentón et al., 2016; Luk and Pliatsikas, 2016; Pliatsikas, 2020). These structural changes in the brain have been shown to influence functional connectivity patterns (Wang and Tao, 2024) and behavioral outcomes for cognitive skills (Gavett et al., 2018). This may, in turn, contribute to a potential bilingual advantage or more efficient cognitive processes in childhood. Task-based functional connectivity measured with fNIRS assesses how different brain regions interact and coordinate their activity during the performance of a specific task. It reflects the temporal correlation in oxygenated hemoglobin fluctuations between regions, revealing which areas co-activate during task engagement and thus may be functionally linked. This approach helps identify networks of coordinated neural activity that support specific cognitive processes, such as inhibitory control (Linnman et al., 2012; Chong et al., 2025). In the context of inhibitory control, studies examining interference suppression have found increased neural activation in areas of the prefrontal cortex, including the bilateral dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex [dlPFC; Brodmann areas (BAs) 9 and 46], medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; BA 10) and bilateral inferior frontal gyrus (IFG; BA 45; Peters and Smith, 2020; Tao et al., 2021; Wang and Tao, 2024). These findings highlight the importance of investigating how bilingualism may shape functional connectivity within these networks during interference suppression tasks.

Despite these advances, understanding the functional impact of bilingualism on interference suppression remains challenging, particularly in young children. However, a recent review highlights fNIRS as a promising tool for refining existing theories on the effects of bilingualism and cognition (see Pliatsikas, 2024 for a review). Importantly, the review notes that fNIRS studies have yet to provide consistent evidence on how bilingualism influences brain function, underscoring the need for further research to clarify these effects. For instance, a study found no association between second language on functional brain activation during a task (Moriguchi and Lertladaluck, 2020), whereas other studies have found those positive associations (Arredondo et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2021).

Furthermore, a recent fNIRS study found evidence that suggests that bilingualism may promote neural efficiency in the PFC. It found that bilingual children required fewer cortical resources during a card sort interference/switching task, suggesting that bilinguals require fewer neural resources to achieve similar behavioral performance as monolinguals (Li et al., 2023). Building on these findings, the current study leverages fNIRS to examine functional connectivity within the bilateral dlPFC, mPFC, and bilateral IFG during interference suppression task. This will provide deeper insights into how bilingual and monolingual preschoolers differ in their neural processing of interference suppression.

By incorporating fNIRS alongside behavioral measures of interference suppression in early childhood, the current study aims to enhance our understanding of the bilingual experience of young children during inhibition. Based on conceptualizations of bilingualism promoting attentional control (Bialystok, 2024; Bialystok and Craik, 2022), we hypothesize that bilingual preschoolers will demonstrate similar behavioral performance on the congruent trials requiring less attentional control and better performance on the incongruent trials of a Simon-like interference suppression task than age-matched monolingual preschoolers. We further hypothesize task-state functional connectivity region of interest pattern differences within the prefrontal cortex with bilingual preschoolers, demonstrating more efficient neural processing (i.e., less global connections) than monolingual preschoolers.

Materials and methods

Participants

The current study utilized data from 26 preschool aged children recruited from an on-campus childcare from a large public university in the United States of America and the surrounding community. Parents of participating children were asked to complete online questionnaires describing family characteristics and home language use. The current sample included 13 bilingual children (female = 9, mean age = 59.39 months) whose home languages were primarily of East Asian or Ibero-Romantic descent and 13 age matched monolingual English children (female = 5, mean age = 59.22 months). Most participating parents for bilingual children had a bachelor’s degree (n = 5) followed by those with a doctorate (n = 4) then a master’s degree (n = 3). One parent had completed some college. Most participating parents for monolingual children had a bachelor’s degree (n = 7) followed by a doctorate (n = 2), master’s degree (n = 2), and having completed some college (n = 2). Second languages spoken at home include Mandarin (n = 4), Portuguese (n = 3), Spanish (n = 3), Korean (n = 1), German (n = 1), and French (n = 1). Descriptive statistics for all continuous and categorical variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Characteristic | Monolingual | Bilingual | Total sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age (months) | 59.22 | 9.27 | 59.39 | 9.27 | 59.30 | 9.08 |

| English proficiency (PPVT) | 128.7 | 17.64 | 115.2 | 23.23 | 121.95 | 21.24 |

| Effortful control | 68.25 | 6.92 | 65.69 | 13.19 | 66.92 | 10.52 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 5 | 38 | 9 | 69 | 14 | 54 |

| Male | 8 | 62 | 4 | 31 | 12 | 46 |

| Parent education | ||||||

| Some college | 2 | 15 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 12 |

| Bachelors | 7 | 54 | 5 | 38 | 12 | 46 |

| Masters | 2 | 15 | 3 | 23 | 5 | 19 |

| Doctorate | 2 | 15 | 4 | 31 | 6 | 23 |

| Second language | ||||||

| Mandarin | 4 | 31 | ||||

| Portuguese | 3 | 23 | ||||

| Spanish | 3 | 23 | ||||

| Korean | 1 | 8 | ||||

| German | 1 | 8 | ||||

| French | 1 | 8 | ||||

| Pairwise comparison | Congruent RT | Incongruent RT | t(12) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (ms) | SD (ms) | M (ms) | SD (ms) | |||

| Monolingual | 1474.06 | 285.96 | 1581.07 | 370.31 | −2.12 | 0.055 |

| Bilingual | 1403.94 | 323.73 | 1531.85 | 413.55 | −1.24 | 0.239 |

Demographic characteristics.

N = 26 (n = 13 for each group).

Bilingualism can be a complex construct, with definitions varying based on age and study purpose. For example, very young children may be considered bilingual if they receive an appropriate amount of exposure to a second language whereas more weight would be given to the level of fluency in older youth and adults. Due to the wide variety of language pairings present in our sample, we selected our bilingual sample based on exposure to a second language rather than proficiency (Loe and Feldman, 2016; Valicenti-McDermott et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2015). For this study, bilingualism is defined as having at least 25% exposure to a second language and monolingualism is defined as having at least 90% exposure to a first language (Pearson et al., 1993). The present study utilized a language background questionnaire (LBQ) adapted from a phone-based questionnaire (Singh et al., 2015) where parents were asked about the different home languages to which their children were exposed. Bilingual participants in our sample had an average of 74% (45–100%) second language exposure from parents. Monolingual children were marked as zero exposure to a second language. All parents of participants signed an IRB approved consent form and received monetary compensation for participating. Children provided assent and received a book or toy of their choosing.

Measures

Peabody picture vocabulary test—fourth edition

English receptive vocabulary was measured using the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—Fourth Edition (PPVT-4) (Dunn and Dunn, 2007) to ensure that all of the children, regardless of their home language, had similar levels of understanding in English. The PPVT-4 is a norm-referenced task that is individually administered by a trained researcher. The task requires the child to choose the picture that best represents the stated word. The child has four picture options to choose from and the task ends when the child misses 8 or more words in a set of 12. The PPVT-4 provides a standardized score based on age and sex.

Child’s behavior questionnaire—effortful control

Similarity between monolingual and bilingual parents’ perceptions of various aspects of their children’s behaviors (e.g., inhibitory control, attention, and emotion regulation), was measured using the effortful control subscale of the child’s behavior questionnaire very short form Putnam and Rothbart (2006) and Rothbart et al. (2001). Parents answered 12 questions related to child effortful control (α = 0.88; e.g., Is good at following instructions.) and a sum score was computed. This measure was included to examine whether caregivers’ reports of the aforementioned behaviors differed between bilingual and monolingual preschoolers and to provide an additional context beyond our laboratory setting.

Spatial conflict arrows (arrows)

Interference suppression was assessed using the Spatial Conflict Arrows (Arrows; Figure 1) task from the EF Touch battery, a computerized set of tasks developed for children aged 3–5 years (Willoughby et al., 2012a; Willoughby et al., 2012b). This Simon-like task (Simon, 1969) measures interference suppression by requiring children to respond to the direction an arrow is pointing, regardless of its location on the screen. In congruent trials, the arrow appears on the same side it points to (e.g., pointing left on the left side), while in incongruent trials, the arrow appears on the opposite side (e.g., pointing left on the right side). All participants completed the same sequence of 36 trials (19 congruent, 17 incongruent), presented in a single block. The task began with 12 congruent trials, followed by 12 incongruent trials, and ended with a mixed sequence. For the first six participants (split evenly between monolingual and bilingual), trials were presented for 2 s, which was later adjusted to 4 s for the remaining participants to better accommodate younger children.

Figure 1

Congruent and incongruent trials for spatial conflict arrows. (A) Represents congruent trials and (B) represents incongruent trials. Children were required to respond based on the direction the arrow is pointing and not the location of the arrow.

Accuracy was scored as the proportion of correct responses (0–1.00), and reaction time was recorded in milliseconds. Performance was analyzed separately for congruent and incongruent trials. Group comparisons between bilingual and monolingual children were conducted using Mann–Whitney U tests for accuracy (based on non-normal distributions) and independent-samples t-tests for reaction time. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, appropriate for small sample sizes (N < 50) (Ghasemi and Zahediasl, 2012). All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.4.2 (R Core Team, 2024).

fNIRS data acquisition and processing

fNIRS data were collected in a secured room using a continuous-wave NIRSport2 system (NIRx, Medical Technologies, LLC). A NIRx prefrontal cortex montage containing eight light sources that emit near-infrared light at wavelengths of 760 and 850 nm and seven detectors (Figure 2) was used. This resulted in 20 channels of data being collected. Prior to the neuroimaging session, parents and children provided consent/assent, and efforts were made to ensure participants’ comfort throughout. Prior to data collection, participants were fitted with the cap which was then calibrated to get the best possible signal. If channels had poor connections, the cap was readjusted, and hair was parted to allow for sources and detectors to have more direct contact with the scalp.

Figure 2

Prefrontal 8 × 8 cap montage. Red circles are source locations and blue circles are detector locations. Location labels follow the EEG 10/10 system. Researchers received verbal consent from the mother and assent from the child to take this photo. Maternal consent was also received to include a deidentified copy of the photo for publication.

Data were exported from the NIRSport2 device into MATLAB version R2022b (The MathWorks Inc., 2022) where the NIRS Brain AnalyzIR Toolbox (Santosa et al., 2018) was used to preprocess the fNIRS data, extract the oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated (HbR) hemoglobin values, map the channel coordinates onto the Brodmann areas of interest (BAs 8, 9, 10, 45, and 46) and calculate the inter- and intra-individual correlations between fNIRS channels for both HbO and HbR. The current analyses focused on changes in hemoglobin concentration and functional connectivity for only HbO values as they are more sensitive to task related changes and have a higher signal amplitude than HbR values (Hoshi, 2003; Luke et al., 2021). Prior to preprocessing the fNIRS data, event triggers for all trials were manually input based off an initial task-start trigger from data collection. Trigger timings were calculated following the previously mentioned pattern of trials. These markers were then used for both analyses. First, raw data were visually inspected for noisy channels. Following the visual inspection, raw values were then converted to optical density values and then a temporal derivative distribution repair (Fishburn et al., 2019) was applied to help correct motion artifacts. Next, optical density values were then converted to HbO and HbR values via the modified Beer–Lambert Law (Jacques, 2013). For the functional connectivity analysis, converted data was down sampled from 10 to 1 Hz in order to reduce the impact of serial autocorrelations on analyses (Pinti et al., 2019). However, for the region of interest analysis, data was not down sampled. Finally, due to the unique statistical properties of fNIRS, an autoregressive, iteratively reweighted robust model (pre-whitening) was used to improve model robustness and account for serial dependencies in the data (Barker et al., 2013; Huppert, 2016).

Region of interest analysis

Participant neural activity (beta values) were calculated by solving a generalized linear model (GLM) for each channel within every participant for both trial types. Level one of the GLM included individual HbO values during task completion. Level-one analysis also included regressors to model channel activation during each task condition regardless of group. Level-two of the GLM explored main effects of condition for each group. Additionally, between group comparisons for both condition types were examined at this level. The formula for the level-two GLM is displayed here [beta ~ − 1 + group:cond + (1|ID)].

Connectivity analysis

Individual level bivariate correlations were calculated between each channel pairing to determine task-state functional connectivity across the prefrontal cortex. The first 24s1 for each trial type (i.e., congruent and incongruent) were utilized for the connectivity analyses. Analyzing trial types individually allows us to capture the nuanced activation patterns and gives us a better overall picture of neural efficiency. Prior to the connectivity analyses, channel coordinates were registered to the Colin 27 atlas with a 53 cm circumference. Task-state functional connectivity was assessed using auto-regressive whitened robust correlations between channel pairs, for HbO. Individual-level connectivity patterns were first calculated using the “connectivity” function from the Nirs Brain AnalyzIR toolbox (Santosa et al., 2018). This function calculates an all-to-all connectivity matrix via an autoregressive, robust correlation with a maximum model order of 4x the sampling rate. Group level models were then calculated using the “MixedEffectsConnectivity” function. The formula for the mixed effects model is presented here (R ~ −1 + group:cond) (for additional information on the mathematical procedures and functions see Barker et al., 2013; Lanka et al., 2022; Santosa et al., 2017; Santosa et al., 2018). To determine significance of channel correlations, one-sample t-tests were conducted and a False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) was used to account for multiple comparisons.

Results

Descriptives

Children in the bilingual and monolingual groups did not differ in age [t(26) = −0.04, p = 0.97], parent report of effortful control (U = 86.50, z = 0.46, p = 0.663, r = 0.09) or receptive English language score as measured by the PPVT-4 [t(16.8) = 1.46, p = 0.162]. Additionally, bilingual and monolingual groups did not differ in terms of parental education levels [t(23.9) = −0.45, p = 0.26]. These findings suggests that both bilingual and monolingual children were comparable in age, English receptive language proficiency, parent reported effortful control behavioral scores, and parental education levels, despite differences in language exposure.

Interference suppression behavioral data

Within group differences

To test for a within group interference effect between correct responses for congruent and incongruent trials of the spatial conflict arrows task, paired samples t-tests were conducted for monolingual and bilingual preschoolers. For the bilingual preschoolers, the results were non-significant [t(12) = −1.24, p = 0.24] suggesting that the bilingual preschoolers did not experience an interference effect during this task. For the monolingual preschoolers, the results were also non-significant [t(12) = −2.12, p = 0.055], however, as the p-value was 0.055 and was approaching significance, this may indicate that there is potentially an interference effect between trial types for monolingual preschoolers and should be tested further with a larger sample.

Between group differences

To test if there are group differences in task performance during the spatial conflict arrows task, Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted due to non-normality in the dependent variables based on the results of the Shapiro–Wilk test which is recommended for small sample sizes (Ghasemi and Zahediasl, 2012; Shapiro et al., 1968; WCong = 0.832, p < 0.001; WInong = 0.917, p = 0.038; WCombined = 0.902, p = 0.017). Accuracy comparisons between bilingual (MdnCong = 0.89, IQR = 0.16; MdnIncong = 0.71, IQR = 0.18; MdnCombined = 0.81, IQR = 0.19) and monolingual (MdnCong = 0.84, IQR = 0.21; MdnIncong = 0.88, IQR = 0.29; MdnCombined = 0.86, IQR = 0.28) preschoolers for task accuracy split by trial type and combined are presented in Table 2. The results indicated that there was not a significant difference in the accuracy between groups (UCong = 84, z = −0.03, p = 0.999, r = 0.01; UIncong = 111.50, z = 1.39, p = 0.171, r = 0.27; UCombined = 102.50, z = 0.93, p = 0.368, r = 0.18) for congruent and incongruent tasks. To test if there are group differences between bilingual (MCong = 1403.94 ms, SD = 323.73 ms; MIncong = 1531.85 ms, SD = 413.55 ms; MCombined = 1415.27 ms, SD = 343.51 ms) and monolingual (MCong = 1474.06 ms, SD = 285.96 ms; MIncong = 1581.07 ms, SD = 370.31 ms; MCombined = 1484.10 ms, SD = 374.36 ms) preschoolers in task reaction time Welch’s two-sample t-tests were conducted as reaction time was normally distributed (WCong = 0.944, p = 0.169; WIncong = 0.981, p = 0.888; WCombined = 0.926, p = 0.061). Reaction time comparisons between groups are presented in Table 3. The results for the t-test indicated that there was also not a significant difference between groups [tCong(23.6) = 0.59, p = 0.564, d = 0.23; tIncong(23.7) = 0.32, p = 0.752, d = 0.13; tCombined(23.8) = 0.49, p = 0.630, d = 0.19] for the congruent and incongruent tasks. This Suggests that both groups were able to respond similarly on both congruent and incongruent tasks of the Simon-like task measuring interference suppression.

Table 2

| Trial type | Monolingual (n = 13) | Bilingual (n = 13) | U(24) | Z-score | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | ||||

| Congruent accuracy | 0.84 | 0.21 | 0.89 | 0.16 | 84 | −0.03 | >0.999 |

| Incongruent accuracy | 0.88 | 0.29 | 0.71 | 0.18 | 111.50 | 1.39 | 0.171 |

| Combined accuracy | 0.86 | 0.22 | 0.81 | 0.19 | 102.50 | 0.93 | 0.368 |

Group comparisons of response accuracy for congruent and incongruent trials.

Groups were compared via Mann–Whitney U tests.

Table 3

| Trial type | Monolingual (n = 13) | Bilingual (n = 13) | t(23.6) | Cohen’s d | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Congruent RT | 1474.06 | 285.96 | 1403.94 | 323.73 | 0.59 | 0.23 | 0.564 |

| Incongruent RT | 1581.07 | 370.31 | 1531.85 | 413.55 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.752 |

| Combined RT | 1484.10 | 374.36 | 1415.27 | 343.51 | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.630 |

Group comparisons of reaction time for correct congruent and incongruent trials.

Groups were compared via Welch’s Two Sample t-test. Reaction times are in milliseconds.

Region of interest analysis results

To evaluate how bilingual and monolingual preschoolers differ in patterns of neural recruitment during interference suppression, a generalized linear model analysis was conducted. For congruent trials, neither monolingual or bilingual participants had significant activation for any channels at an FDR corrected q-value of 0.05. For incongruent trials, only the monolingual participants had significant activation in channels S1-D2, β = 12.49, SE = 3.46, t(46) = 3.61, q = 0.04, and S4-D5, β = 16.25, SE = 3.39, t(46) = 4.79, q < 0.01.

For congruent trials, there were no significant differences in channel activation at a q < 0.05 between monolingual and bilingual preschoolers. Channels S1-D2, β = 12.49, SE = 3.46, t(46) = 3.61, q = 0.01, and S4-D5, β = 16.25, SE = 3.39, t(46) = 4.79, q < 0.001.

A bar plot for fNIRS channels averaged into regions of interest based on the channel weights (Supplementary Table 1) is displayed in Figure 3. Each bar plot represents a different group (Bilingual/Monolingual) by trial type (Congruent/Incongruent) pairing. The canonical hemodynamic response function for significant (p < 0.05) group by trial type for each channel is displayed in Figure 4 for monolingual preschoolers and Figure 5 for bilingual preschoolers. Supplementary results at an uncorrected p < 0.05 are also included in Supplementary information. These results did not meet the significance threshold after correcting for multiple comparisons. However, they may display important trends which are valuable for future research with larger sample sizes. We are cautious to overinterpret these uncorrected results but hope that sharing these patterns will guide future investigations in this area.

Figure 3

Beta values by region of interest. *q < 0.05. Channel weights for each region of interest are located in Supplementary Table 1; L DLPFC, Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex; L IFG, Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus; L mPFC, Left Medial Prefrontal Cortex; R DLPFC, Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex; R FEF, Right Frontal Eye Fields; R IFG, Right Inferior Frontal Gyrus; R mPFC, Right Medial Prefrontal Cortex.

Figure 4

Average hemodynamic response function by channel for significant group × congruent pairings. Error bars are represented by ± 1 SE; Channel S1_D2 covers part of the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (BA_9L); Channel S4_D2 covers part of the Right Frontal Eye Fields (BA_8R); Channel S5_D6 covers part of the Right Medial Prefrontal Cortex (BA_10R); Channel S7_D5 covers part of the Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (BA_9R).

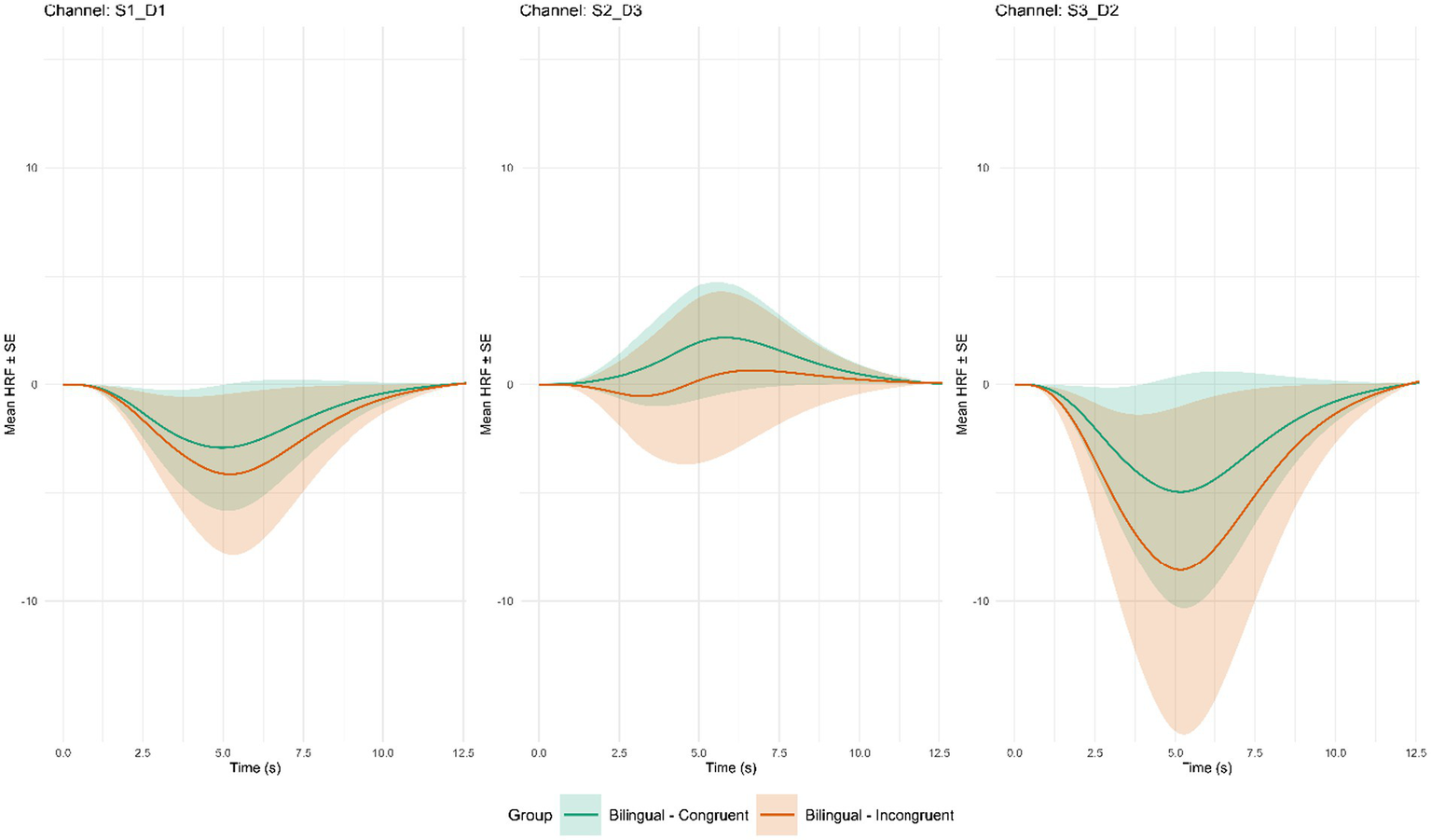

Figure 5

Average hemodynamic response function by channel for significant group × incongruent pairings. Error bars are represented by ± 1 SE; Channel S1_D1 covers part of the Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus (BA_45L); Channel S2_D3 covers part of the Left Medial Prefrontal Cortex (BA_10L); Channel S3_D2 covers part of the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (BA_9L).

Functional connectivity results

To test our hypothesis that bilingual children would show more efficient neural processing during interference suppression, we examined group differences in task-related functional connectivity within the prefrontal cortex. Specifically, we expected bilingual preschoolers to exhibit more localized connectivity patterns reflecting efficient recruitment of executive control regions, while monolingual preschoolers were hypothesized to show broader, less focused connectivity, indicative of greater or less efficient resource recruitment. Bilingual preschoolers exhibited more localized connectivity with significant correlations primarily observed in the left and right hemispheres of the dorsolateral (BAs 9 and 46) and medial (BA10) PFC. At an FDR corrected q-value of 0.001, bilingual children showed 28 significant correlations during congruent trials and 21 significant correlations for incongruent trials. However, there were relatively few connections between the dlPFC/mPFC to the Frontal Eye-fields (FEF; BA 8) and the left/right IFG (BA 45) suggesting more efficient recruitment of core executive function regions during task performance. Conversely, monolingual preschoolers exhibited a more broadly distributed pattern of functional connectivity. Monolinguals showed 35 significant connections during congruent trials and 63 significant correlations for incongruent trials, across the PFC, including stronger connections to the FEF and IFG, suggesting less efficient and more broadly distributed engagement of PFC, potentially requiring the co-activation of multiple regions to support task demands during interference suppression (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

Task-state functional connectivity patterns for oxygenated hemoglobin. (A) Displays task-state functional connectivity patterns for all preschoolers split by group and trial type. (B) Displays task-state functional connectivity correlation matrices split by group and trial type. Correlation patterns are displayed on a Mercator projected 2D atlas for each group x trial type pairing.

Together these results suggest bilingual and monolingual preschoolers engage distinct functional connectivity patterns during task-state interference suppression Bilingual preschoolers exhibited a more localized connectivity pattern particularly between regions of the left and right dlPFC and mPFC which may reflect a more efficient recruitment of neural resources. In contrast, monolingual showed broader PFC connectivity, particularly with attention control regions FEF and cognitive control IFG, suggesting greater network-wide engagement during the task. To see a full table of channel weights for Brodmann Areas and channel pairing correlation values (see Supplemental material).

Discussion

The current study aimed to enhance our understanding of the bilingual experience of young children in relation to executive function by examining both behavioral performance and neural processing during a Simon-like interference suppression task using fNIRS. We focused on the interference suppression aspect of interference suppression following conceptualizations of bilingualism promoting attentional control (Bialystok, 2024; Bialystok and Craik, 2022). Our hypotheses were two-fold. First, for the behavioral data, we hypothesized that monolingual and bilingual preschoolers would perform similarly on the congruent interference suppression task which did not require suppression of information, and that bilingual preschoolers would perform better than monolingual preschoolers on the incongruent task that required more attentional control. Second, for the neuroimaging data, we hypothesized that compared to monolingual preschoolers, bilingual preschoolers would demonstrate more efficient neural processing resulting in less global connections during interference suppression.

As hypothesized, bilingual and monolingual preschoolers performed similarly on congruent trials. Conversely, our lack of significant differences for accuracy and response time on incongruent trials are inconsistent with our hypothesis that bilingual children would outperform the monolingual children on incongruent trials. However, these findings are consistent with recent literature that reported no bilingual group advantage in behavioral performance during either the congruent or incongruent trials in an age-appropriate interference suppression task, indicated by the similarity in performance on accuracy and response time (Lowe et al., 2021). Similarities in behavioral data findings may support the perspective that children need to be older with more refined interference suppression skills having been developed before behavioral performance differences are found between monolinguals and bilinguals. Indeed, a systematic review conducted found that for interference suppression, only 38% of studies found a bilingual advantage when using a Simon-like task during the critical period (i.e., younger than 6 years old) compared to 60% who found an advantage in the older, post-critical period age group (i.e., 6–12 years old; Planckaert et al., 2023). Following the theory that attention control is the underlying mechanism that could contribute to a bilingual advantage, the tasks, while age-appropriate, may not have been complex enough to require high levels of attention (Bialystok, 2024). While these explanations should be examined further, it may be that there is not a detectable inhibition behavioral difference between monolingual and bilingual preschoolers. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis suggests that research studies that report a bilingual advantage are based on small effect sizes with the findings moderated by SES and the quality of the research design (Lowe et al., 2021). They suggest addressing these limitations through large sample sizes, improved methodological rigor and moving beyond measuring bilingualism/monolingualism as a dichotomous variable (Lowe et al., 2021). As bilingualism is not a static, monolithic trait, bilingual children vary in their age of language acquisition, proficiency in each language, switching between languages and the context for language interactions (De Bruin, 2019). More detailed and nuanced information about bilingual participants and their language experiences could improve our understanding of the effect of bilingualism on the complex construct of executive functioning.

Region of interest and functional connectivity

Interestingly, despite the lack of differences in behavioral performance, we found strong evidence for differences in ROI activation and task-state functional connectivity patterns. Regarding ROI activation, in comparison with bilinguals, there was the greatest increase in activation for monolinguals during incongruent trials in channel S1-D2 (FEF; BA8) and S4-D5 (BA9-dorsomedial PFC and BA10-frontopolar PFC). FEF have been implicated in eye/gaze control and decision-making driven by uncertainty (Dadario et al., 2023). The dorsomedial PFC has shown involvement with response-, decision-, and strategic-control (Venkatraman et al., 2009) and the frontopolar PFC has been associated with metacognition during decision making (Qiu et al., 2018) and also in processing concurrent potential behavioral plans during decision making (Koechlin and Hyafil, 2007).

Also, while exhibiting more localized prefrontal connectivity patterns, bilingual preschoolers showed similar behavioral performance to monolingual preschoolers in both task accuracy and reaction time. This, in conjunction with the aforementioned reduced activation in key decision-making areas of the PFC, suggests that bilingual children may engage a more efficient prefrontal network during interference suppression rather than relying on widespread cortical recruitment. Bilingual children may have more practice with and proficiency in attentional control due to their experience with processing multiple languages (Bialystok and Craik, 2022), leading to adapted neural activation patterns aligning with the neural efficiency hypothesis (Debarnot et al., 2014).

Our findings are supported by Li et al. (2023) who found that bilingual preschoolers showed similar behavioral performance to monolingual preschoolers in a switching/interference suppression task, however, the bilingual preschoolers activated only 11 channels compared to the 15 of the monolingual children suggesting more efficient executive function processing for the bilingual children. Additionally, similar to our results, monolingual children significantly activated the FEF region whereas bilingual children did not (Li et al., 2023). The FEF region is heavily involved in the allocation of attention to relevant stimuli (Corbetta and Shulman, 2002). The reduced connectivity to the FEF in bilingual children may reflect greater efficiency within attentional control, requiring less engagement of this region to allocate attention to relevant stimuli. This finding provides some support for the idea that bilingualism facilitates neural efficiency in executive function. Conversely, monolingual children, who have less experience managing competing linguistic inputs, may require broader and less specialized patterns when suppressing conflicting stimuli.

Our results suggest that bilingual and monolingual preschoolers recruit different neural networks when suppressing irrelevant information. The bilingual children exhibited lower activation across prefrontal regions, as reflected in smaller beta values from the GLM analysis for both congruent and incongruent trials, along with more localized task-based connectivity patterns. Despite these differences, they achieved comparable accuracy and reaction times to monolingual children. Together, these findings suggest that bilingual children may engage a more efficient and targeted prefrontal network during interference suppression (incongruent trials), requiring fewer cortical resources to meet the same cognitive demands. These reduced activation levels and specialized connectivity patterns may reflect a more refined neural strategy rather than broad, distributed prefrontal recruitment. Over time, this efficiency in executive function may contribute to cognitive advantages, particularly in academic settings where attentional control and cognitive flexibility are essential for learning. As bilingual children continue to develop, their ability to manage competing linguistic inputs, especially for those who are highly proficient in their second language, may enhance their capacity to process new, complex information with reduced reliance on broader cognitive resources (Hansen et al., 2025).

Limitations and future directions

The current study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the sample size was small (13 per group) which limits statistical power to detect smaller effect sizes especially for group differences in behavioral results. However, our sample size was comparable to multiple others looking at bilingual and monolingual preschoolers (Arredondo et al., 2017; Li et al., 2023; Moriguchi and Lertladaluck, 2020; Okanda et al., 2010). Future studies should utilize larger group sizes to increase power. Second, the sample was recruited from a single large public university and the surrounding community which may limit the generalizability of the results to other regions. The language experiences for both bilingual and monolingual preschoolers are likely to be different based on region (i.e., rural/urban; McCoy et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2025) and should be examined further. Sampling from multiple diverse locations to increase generalizability would help address this limitation. Third, short separation channels (SSCs) were not utilized in the current study which introduces the risk of superficial noise contaminating the fNIRS signal. Future studies should consider the use of SSCs, however, it should be noted that for young children (i.e., 3 years old) 1 cm SSCs may include some cortical contribution (Pinti et al., 2024) increasing the risk of removing true cortical activity when analyzing the data which warrants caution when using SSCs with young children. Fourth, the bilingual group included a wide variety of home languages which may bias results as language pairings may impact functional brain activation differently during interference suppression due to concepts such as language distance (Leivada et al., 2024). Future studies may benefit from limiting the range of language pairings or systematically accounting for language distance to better isolate bilingualism-related effects. Fifth, we were unable to fully control for child sex due to the smaller sample size. While our matching procedure prioritized age, this resulted in unequal sex distributions across groups. Balancing sex across conditions in future work would allow for better control of this variable. Finally, the trial blocks for the connectivity analysis were only 24 s per condition. Although this approach ensured consistency across participants, longer task blocks may improve the reliability of connectivity estimates (Wang et al., 2017).

Conclusion

The current study used fNIRS neuroimaging and behavioral data to examine inhibitory control in bilingual and monolingual preschool-aged children. Region of interest (ROI) GLM and task state functional connectivity analyses across the prefrontal cortex were analyzed for an interference suppression Simon-like task for 13 bilingual and 13 monolingual children. While bilingual and monolingual child performed similarly in terms of task accuracy and reaction time, ROI and functional connectivity analyses revealed that bilingual preschoolers exhibited a more localized prefrontal connectivity pattern compared to monolinguals, which may indicate greater neural efficiency during interference suppression processing compared to their monolingual peers. Greater efficiency in interference suppression may reflect adaptations in attention control due to experience with bilingualism, potentially supporting broader cognitive development. Further research is needed to explore how these neural differences evolve over time and whether they translate into long-term cognitive or academic advantages.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Utah State University Office of Research Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was not obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article because verbal informed consent was received from the child’s parent to take and publish the image and verbal assent was received from the child to take the photo.

Author contributions

MC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AH: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MT: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Funding for this project was received from the Utah State University College of Education and Human Services Graduate Award Opportunity. Funding supporting the open access publication of this manuscript was received from the Utah State University Library Open Access Fund.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnint.2025.1591250/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^To ensure consistency in our time-based connectivity analysis, we constrained the analysis window to an equal duration (24 s) across all participants, regardless of trial timing. Although the first six participants completed 12 trials at 2 s each, and the remaining participants completed 12 trials at 4 s each, the same 24-s time window was used for all. A sensitivity analysis excluding the first 6 participants revealed a global decrease of connections for all trial type x group combinations while maintaining similar patterns between monolingual and bilingual children. This global decrease likely represents a loss of statistical power, thus, we retained the full sample size of 26 participants for the final analyses.

References

1

Anthony C. J. Ogg J. (2020). Executive function, learning-related behaviors, and science growth from kindergarten to fourth grade. J. Educ. Psychol.112, 1563–1581. doi: 10.1037/edu0000447

2

Arredondo M. M. Hu X. S. Satterfield T. Kovelman I. (2017). Bilingualism alters children's frontal lobe functioning for attentional control. Dev. Sci.20:e12377. doi: 10.1111/desc.12377,

3

Arredondo M. M. Kovelman I. Satterfield T. Hu X. Stojanov L. Beltz A. M. (2022). Person-specific connectivity mapping uncovers differences of bilingual language experience on brain bases of attention in children. Brain Lang.227:105084. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2022.105084,

4

Barker J. W. Aarabi A. Huppert T. J. (2013). Autoregressive model based algorithm for correcting motion and serially correlated errors in fNIRS. Biomed. Opt. Express4, 1366–1379. doi: 10.1364/BOE.4.001366,

5

Beisly A. Jeon S. (2024). Development of inhibitory control in head start children: association with approaches to learning and academic outcomes in kindergarten. Cogn. Dev.70:101434. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2024.101434

6

Benjamini Y. Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat Methodol.57, 289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x

7

Bialystok E. (2024). Bilingualism modifies cognition through adaptation, not transfer. Trends Cogn. Sci.28, 987–997. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2024.07.012,

8

Bialystok E. Craik F. I. (2022). How does bilingualism modify cognitive function? Attention to the mechanism. Psychon. Bull. Rev.29, 1246–1269. doi: 10.3758/s13423-022-02057-5,

9

Chong K. Chen S. Chen X. Zhang X. Liu D. Zhou Z. et al . (2025). Resting-state connectivity and task-based cortical response in post-stroke executive dysfunction: A fNIRS study. NeuroImage: Reports, 5, 100236. doi: 10.1016/j.ynirp.2025.100236,

10

Corbetta M. Shulman G. L. (2002). Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.3, 201–215. doi: 10.1038/nrn755,

11

Dadario N. B. Tanglay O. Sughrue M. E. (2023). Deconvoluting human Brodmann area 8 based on its unique structural and functional connectivity. Frontiers in neuroanatomy, 17:1127143. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2023.1127143,

12

De Bruin A. (2019). Not all bilinguals are the same: A call for more detailed assessments and descriptions of bilingual experiences. Behav. Sci.9:33. doi: 10.3390/bs9030033,

13

Debarnot U. Sperduti M. Di Rienzo F. Guillot A. (2014). Experts bodies, experts minds: how physical and mental training shape the brain. Front. Hum. Neurosci.8:280. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00280,

14

Dunn L. M. Dunn D. M. (2007). Peabody picture vocabulary test--fourth edition (PPVT-4) [database record]. APA PsycTests. doi: 10.1037/t15144-000

15

Fishburn F. A. Ludlum R. S. Vaidya C. J. Medvedev A. V. (2019). Temporal derivative distribution repair (TDDR): a motion correction method for fNIRS. NeuroImage184, 171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.09.025,

16

Fiske A. Holmboe K. (2019). Neural substrates of early executive function development. Dev. Rev.52, 42–62. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2019.100866,

17

García-Pentón L. Fernandez Garcia Y. Costello B. Duñabeitia J. A. Carreiras M. (2016). The neuroanatomy of bilingualism: how to turn a hazy view into the full picture. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci.31, 303–327. doi: 10.1080/23273798.2015.1068944

18

Gavett B. E. Fletcher E. Harvey D. Farias S. T. Olichney J. Beckett L. et al . (2018). Ethnoracial differences in brain structure change and cognitive change. Neuropsychology32, 529–540. doi: 10.1037/neu0000452,

19

Ghasemi A. Zahediasl S. (2012). Normality tests for statistical analysis: a guide for non-statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab.10, 486–489. doi: 10.5812/ijem.3505,

20

Hansen E. Slawny C. Kaushanskaya M. (2025). The influence of cross-speaker code-switching and language ability on inhibitory control in bilingual children. Biling. Lang. Cogn.28, 980–988. doi: 10.1017/S1366728924000804

21

Hilchey M. D. Klein R. M. (2011). Are there bilingual advantages on nonlinguistic interference tasks? Implications for the plasticity of executive control processes. Psychon. Bull. Rev.18, 625–658. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0116-7,

22

Hoshi Y. (2003). Functional near-infrared optical imaging: utility and limitations in human brain mapping. Psychophysiology40, 511–520. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00053,

23

Huppert T. J. (2016). Commentary on the statistical properties of noise and its implication on general linear models in functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Neurophotonics3:010401. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.3.1.010401,

24

Hwang K. Velanova K. Luna B. (2010). Strengthening of top-down frontal cognitive control networks underlying the development of inhibitory control: a functional magnetic resonance imaging effective connectivity study. J. Neurosci.30, 15535–15545. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2825-10.2010,

25

Jacques S. L. (2013). Optical properties of biological tissues: a review. Phys. Med. Biol.58, R37–R61. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/11/R37,

26

Jones D. T. Graff-Radford J. (2021). Executive dysfunction and the prefrontal cortex. Behav. Neurol. Psychiatry27, 1586–1601. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000001009,

27

Koechlin E. Hyafil A. (2007). Anterior prefrontal function and the limits of human decision-making. Science318, 594–598. doi: 10.1126/science.1142995,

28

Lanka P. Bortfeld H. Huppert T. J. (2022). Correction of global physiology in resting-state functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Neurophotonics9:035003. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.9.3.035003,

29

Leivada E. Kelly-Iturriaga L. Masullo C. Westergaard M. Rothman J. (2024). The unpredictable role of language distance in bilingual cognition: A systematic review from brain to behavior. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition1–14. doi: 10.1017/S1366728925100746

30

Li H. Wu D. Yang J. Xie S. Chang C. Luo J. (2023). Bilinguals have more effective executive function: evidence from an fNIRS study of the neural correlates of cognitive shifting. Int. J. Bilingual.27, 22–38. doi: 10.1177/13670069221076375

31

Linnman C. Moulton E. A. Barmettler G. Becerra L. Borsook D. (2012). Neuroimaging of the periaqueductal gray: state of the field. NeuroImage60, 505–522. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.095,

32

Loe I. M. Feldman H. M. (2016). The effect of bilingual exposure on executive function skills in preterm and full term preschoolers. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr.37, 548–556. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000318,

33

Lowe C. J. Cho I. Goldsmith S. F. Morton J. B. (2021). The bilingual advantage in children’s executive functioning is not related to language status: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Sci.32, 1115–1146. doi: 10.1177/0956797621993108,

34

Luk G. Pliatsikas C. (2016). Converging diversity to unity: commentary on theneuroanatomy of bilingualism. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci.31, 349–352. doi: 10.1080/23273798.2015.1119289

35

Luke R. Shader M. J. Gramfort A. Larson E. Lee A. K. McAlpine D. (2021). Oxygenated hemoglobin signal provides greater predictive performance of experimental condition than de-oxygenated. BioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2021.11.19.469225

36

Martin-Rhee M. M. Bialystok E. (2008). The development of two types of inhibitory control in monolingual and bilingual children. Bilingualism11, 81–93. doi: 10.1017/S1366728907003227

37

McCoy D. C. Morris P. A. Connors M. C. Gomez C. J. Yoshikawa H. (2016). Differential effectiveness of head start in urban and rural communities. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol.43, 29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2015.12.007,

38

Mehnert J. Akhrif A. Telkemeyer S. Rossi S. Schmitz C. H. Steinbrink J. et al . (2013). Developmental changes in brain activation and functional connectivity during response inhibition in the early childhood brain. Brain Dev.35, 894–904. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.11.006,

39

Moffitt T. E. Arseneault L. Belsky D. Dickson N. Hancox R. J. Harrington H. et al . (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.108, 2693–2698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010076108,

40

Moriguchi Y. (2014). The early development of executive function and its relation to social interaction: a brief review. Front. Psychol.5:388. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00388,

41

Moriguchi Y. Lertladaluck K. (2020). Bilingual effects on cognitive shifting and prefrontal activations in young children. Int. J. Bilingual.24, 729–739. doi: 10.1177/1367006919880274

42

Morita T. Asada M. Naito E. (2016). Contribution of neuroimaging studies to understanding development of human cognitive brain functions. Front. Hum. Neurosci.10:464. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00464,

43

Nayak S. Salem H. Z. Tarullo A. R. (2020). Neural mechanisms of response-preparation and inhibition in bilingual and monolingual children: lateralized readiness potentials (LRPs) during nonverbal Stroop task. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci.41:100740. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2019.100740,

44

Okanda M. Moriguchi Y. Itakura S. (2010). Language and cognitive shifting: evidence from young monolingual and bilingual children. Psychol. Rep.107, 68–78E. doi: 10.2466/03.10.28.PR0.107.4.68-78,

45

Paap K. (2022). The bilingual advantage in executive functioning hypothesis: how the debate provides insight into psychology’s replication crisis. New York: Routledge.

46

Pearson B. Z. Fernandez S. C. Oller D. K. (1993). Lexical development in bilingual infants and toddlers: comparison to monolingual norms. Lang. Learn.43, 93–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1993.tb00174.x

47

Peters G. J. Smith D. M. (2020). The medial prefrontal cortex is needed for resolving interference even when there are no changes in task rules and strategies. Behav. Neurosci.134, 15–20. doi: 10.1037/bne0000347,

48

Pinti P. Dina L. M. Smith T. J. (2024). Ecological functional near-infrared spectroscopy in mobile children: using short separation channels to correct for systemic contamination during naturalistic neuroimaging. Neurophotonics11:045004. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.11.4.045004,

49

Pinti P. Scholkmann F. Hamilton A. Burgess P. Tachtsidis I. (2019). Current status and issues regarding pre-processing of fNIRS neuroimaging data: an investigation of diverse signal filtering methods within a general linear model framework. Front. Hum. Neurosci.12:505. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00505,

50

Planckaert N. Duyck W. Woumans E. (2023). Is there a cognitive advantage in inhibition and switching for bilingual children? A systematic review. Front. Psychol.14:1191816. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1191816,

51

Pliatsikas C. (2020). Understanding structural plasticity in the bilingual brain: the DynamicRestructuring model. Biling. Lang. Cogn.23, 459–471. doi: 10.1017/S1366728919000130

52

Pliatsikas C. (2024). Examining functional near-infrared spectroscopy as a tool to study brain function in bilinguals. Front. Lang. Sci.3:1471133. doi: 10.3389/flang.2024.1471133

53

Putnam S. P. Rothbart M. K. (2006). Development of short and very short forms of the children's behavior questionnaire. J. Pers. Assess.87, 102–112. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8701_09,

54

Qiu L. Su J. Ni Y. Bai Y. Zhang X. Li X. et al . (2018). The neural system of metacognition accompanying decision-making in the prefrontal cortex. PLoS Biol.16:e2004037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004037,

55

R Core Team (2024) R: a language and environment for statistical computingViennaR Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/

56

Rothbart M. K. Ahadi S. A. Hershey K. L. Fisher P. (2001). Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: the children's behavior questionnaire. Child Dev.72, 1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355,

57

Rothbart M. K. Posner M. I. (1985). “Temperament and the development of self-regulation” in The neuropsychology of individual differences (Boston, MA: Springer), 93–123.

58

Santosa H. Aarabi A. Perlman S. B. Huppert T. J. (2017). Characterization and correction of the false-discovery rates in resting state connectivity using functional near-infrared spectroscopy. J. Biomed. Opt.22:055002. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.22.5.055002,

59

Santosa H. Zhai X. Fishburn F. Huppert T. (2018). The NIRS brain AnalyzIR toolbox. Algorithms11:73. doi: 10.3390/a11050073,

60

Sasser T. R. Bierman K. L. Heinrichs B. (2015). Executive functioning and school adjustment: the mediational role of pre-kindergarten learning-related behaviors. Early Child. Res. Q.30, 70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.09.001,

61

Shapiro S. S. Wilk M. B. Chen H. J. (1968). A comparative study of various tests for normality. J. Am. Stat. Assoc.63, 1343–1372. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1968.10480932

62

Simon J. R. (1969). Reactions toward the source of stimulation. J. Exp. Psychol.81, 174–176. doi: 10.1037/h0027448,

63

Singh L. Fu C. S. Rahman A. A. Hameed W. B. Sanmugam S. Agarwal P. et al . (2015). Back to basics: a bilingual advantage in infant visual habituation. Child Dev.86, 294–302. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12271

64

Tao L. Wang G. Zhu M. Cai Q. (2021). Bilingualism and domain-general cognitive functions from a neural perspective: a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.125, 264–295. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.02.029,

65

The MathWorks Inc. (2022) MATLAB version: 9.13.0 (R2022b)Natick, MAThe MathWorks Inc.. Available online at: https://www.mathworks.com

66

Valicenti-McDermott M. Tarshis N. Schouls M. Galdston M. Hottinger K. Seijo R. et al . (2013). Language differences between monolingual English and bilingual English-Spanish young children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Child Neurol.28, 945–948. doi: 10.1177/0883073812453204,

67

Venkatraman V. Rosati A. G. Taren A. A. Huettel S. A. (2009). Resolving response, decision, and strategic control: evidence for a functional topography in dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci.29, 13158–13164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2708-09.2009,

68

Wang J. Dong Q. Niu H. (2017). The minimum resting-state fNIRS imaging duration for accurate and stable mapping of brain connectivity network in children. Sci. Rep.7:6461. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06340-7,

69

Wang G. Tao L. (2024). Bilingual language control in the brain: evidence from structural and effective functional brain connectivity. J. Cogn. Neurosci.36, 836–853. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_02128,

70

Willoughby M. T. Blair C. B. Wirth R. J. Greenberg M. (2012a). The measurement of executive function at age 5: psychometric properties and relationship to academic achievement. Psychol. Assess.24, 226–239. doi: 10.1037/a0025361,

71

Willoughby M. T. Kuhn L. J. Blair C. B. Samek A. List J. A. (2017). The test-retest reliability of the latent construct of executive function depends on whether tasks are represented as formative or reflective indicators. Child Neuropsychol.23, 822–837. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2016.1205009,

72

Willoughby M. T. Wirth R. J. Blair C. B. (2012b). Executive function in early childhood: longitudinal measurement invariance and developmental change. Psychol. Assess.24, 418–431. doi: 10.1037/a0025779,

73

Xie S. Wu D. Yang J. Luo J. Chang C. Li H. (2021). An fNIRS examination of executive function in bilingual young children. Int. J. Biling.25, 516–530. doi: 10.1177/1367006920952881

74

Yang J. Luo Q. Li Y. Huang C. Xu Y. Ou K. et al . (2025). Unveiling the urban-rural discrepancy: a comprehensive analysis of reading and writing development among Chinese elementary school students. Learn. Instr.98:102145. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2025.102145

75

Yurtsever A. Anderson J. A. Grundy J. G. (2023). Bilingual children outperform monolingual children on executive function tasks far more often than chance: an updated quantitative analysis. Dev. Rev.69:101084. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2023.101084

76

Zelazo P. D. Carlson S. M. (2012). Hot and cool executive function in childhood and adolescence: development and plasticity. Child Dev. Perspect.6, 354–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00246.x

77

Zhou D. Lynn C. W. Cui Z. Ciric R. Baum G. L. Moore T. M. et al . (2022). Efficient coding in the economics of human brain connectomics. Netw. Neurosci.6, 234–274. doi: 10.1162/netn_a_00223,

Summary

Keywords

fNIRS, functional connectivity, bilingualism, preschool, inhibitory control

Citation

Cook ML, Boyce LK, Hancock AS, Turner MS and Bradshaw SD (2025) Examining the role of early bilingualism on interference suppression and prefrontal connectivity. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 19:1591250. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2025.1591250

Received

10 March 2025

Revised

18 October 2025

Accepted

28 November 2025

Published

17 December 2025

Volume

19 - 2025

Edited by

Avantika Mathur, Vanderbilt University, United States

Reviewed by

Arun Karumattu Manattu, University of Wisconsin-Madison, United States

Zhilong Xie, Jiangxi Normal University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Cook, Boyce, Hancock, Turner and Bradshaw.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew L. Cook, matthew.cook@usu.edu

†Present address: Allison S. Hancock,Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia Research Center, Utah State University, Logan, UT, United States

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.