- 1Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona (ASPB), Barcelona, Spain

- 2CIBER of Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain

- 3Institut de Recerca Biomédica Sant Pau (IIB SANT PAU), Barcelona, Spain

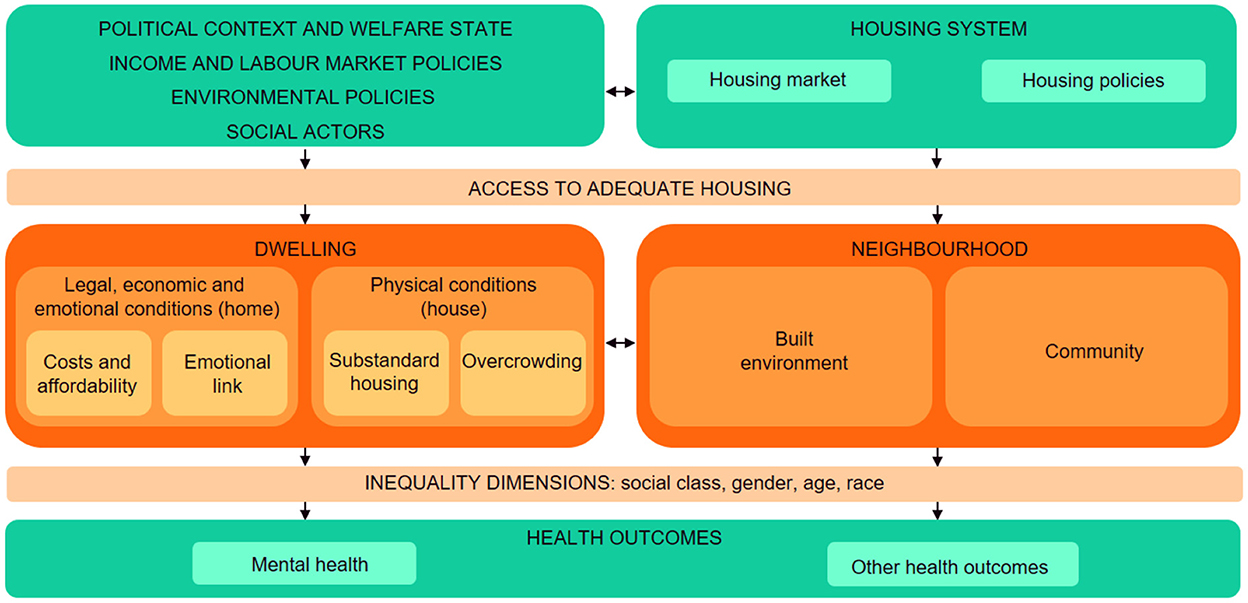

The title of this section of Frontiers in Environmental Health “Housing conditions and public health” reflects the topic of the section because precisely these conditions have been associated to physical and mental health. The macro policies, the housing system, the neighborhood, and the physical, and social conditions can have an impact on health. These conditions have different impact on health according to the dimensions of inequalities. The Figure 1 below summarizes the relationship between housing and health (1).

Figure 1. Housing determinants of health. Source: Adapted from the proposal of Novoa et al. (1).

The macro-structural conditions include the political context, the welfare state, income policies, labor market policies and environmental policies. These macro-structural conditions include government and political tradition, economic and social actors (such as large multinationals, wars, etc.). Increasingly, these policies depend on higher instances of the country, such as other countries of the European Union. There are some studies that relate the political context with the health and health inequalities of the population and show the influence of political tradition on health, in the sense that countries with a social democratic tradition promote a more extensive welfare state, promote more progressive fiscal policies, with fewer income inequalities and full employment policies, offering better results in some health indicators (2). However, political actors are influenced by many forces, some of them related with the interests of social actors or enterprises that act as a lobby, especially powerful in the case of housing, where the lucrative aspects are very important. Moreover, environmental policies may influence housing policies in order to promote environmentally sound housing construction and maintenance to address the effects of climate change.

The housing system: Housing is a social right, as stated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the United Nations (article 25). Government's housing policy (taxation, social housing) can increase access to high quality affordable housing, especially among low-income households, which can improve residents' health and reduce health inequalities (3). Public social housing can heavily influence income distribution by offering housing at a relatively cheap or moderate price. In some cities, this type of housing can represent more than half of the total housing stock. However, the housing system is regulated not only by the governments but also by the market, which can lead to a speculative use of housing. In countries where the market is predominant, adequate housing is a commodity difficult to access, especially among low-income population. For example, during the economic recession many people lost their house because they were not able to pay their mortgage. From a health and health inequalities perspective, housing policies should focus on improving housing affordability, stability and quality, with a special focus on low-income populations, as well as neighborhood and environmental design, to maximize the health benefits (4, 5). Although there are recognized barriers to implementing housing policies from a health perspective (6), there are also some facilitators. For instance, housing policies can benefit different sectors, including health and well-being as well as environmental sustainability. A more systemic approach in housing policies can address the complex interaction that exists between housing, environment and health (7).

The legal, economic and emotional conditions (the home): Included in this dimension there are several aspects. One is housing affordability, which refers to the ability to pay the rent or mortgage as well as other housing-related costs such as energy or water supplies. Housing affordability issues have been related to both poor physical and mental health (8–15), and can reduce the available budget to attain other basic needs, such as food, clothing or medications. It can also eventually end in foreclosure and eviction, situations which have been related to very poor health conditions, much worse than that of the general population (16). Another aspect is tenure security, a concept very closely related to ontological security, which implies being able to develop a stable life project in the same place, which reduces uncertainty and anxiety, generates peace of mind and allows to develop feelings of rootedness and belonging (17, 18). The concept of housing insecurity (sometimes used in the literature as housing instability) includes different combinations of housing unaffordability and tenure insecurity. Finally, another aspect included in this dimension is the emotional and social meaning of the home, according to which dwellings can provide feelings of security, stability and connection, and therefore enhance wellbeing (19–21). Feeling unsatisfied with one's home can result in psychological distress, which can lead to physical and mental health problems (10, 22).

The physical conditions (the house): The physical aspects of the house are also important to promote a good health status (13, 14, 23–25). They can be classified according to 3 categories: thermal comfort, environmental quality, and space quality and functionality.

When referring to inadequate housing temperature, it is not only important to focus on the effect of cold temperatures because health impacts can be attributable to both cold and hot temperatures (26, 27). Fuel poverty has been defined as not being able to keep the house at an adequate temperature and it is caused by 3 aspects: (1) low incomes and not being able to pay the energy costs, (2) high energy prices, which are expected to continue increasing following the start of the Ukraine war in 2022; and (3) poor energy efficiency of housing due to the low quality of materials used in the construction (28, 29). The effects of dampness, moisture and mold on health are well known, they can result in allergic and respiratory problems, in addition to mental health problems, as well as general symptoms such as fatigue or headache (22, 23, 25, 30–33).

Other physical housing conditions that can have an impact on health include environmental quality such as exposure to indoor allergens and chemicals such as radon, lead, carbon monoxide, emission of pollutants from cooking and heating with gas or solid fuels, volatile organic compounds from cleaning materials and solvents, as well as dust, pests and infestations and outside noise (30, 32, 34). These exposures are higher in low-income countries, which have lower quality housing.

Related with space quality, houses with overcrowding (to many people living in the house) can also result in poor physical health, including increased risk of infectious diseases. It has also been associated with higher rates of poor mental health among adults and children, and reduced school performance among children, in addition to interpersonal conflicts (10, 23, 25, 31, 33, 34).

The physical and social environment of the neighborhood: The neighborhood where the dwelling is located also has an important influence on health and health inequalities (14, 35). Neighborhood characteristics are heavily influenced by urban planning, which determines the available public infrastructure (such as transport infrastructure and public transportation, or the sewerage system) and equipment (sport, health and education, among others) as well as more general regulations concerning aspects such as buildings and public space use. Urban planning can also influence a neighborhood's environmental characteristics, such as water and air quality and noise pollution, important health determinants, mainly in urban areas. Especially important in urban areas is air and noise pollution derived from motorized mobility, aspects that have been related with several negative health outcomes (36–38).

Health-promoting residential environments should provide access to appropriate commerce, education, employment, healthy food outlets, and healthcare within walking distance, and should also include adequate street design, green spaces and other places for leisure, all of which have been linked to positive mental health and physical activity (22, 32). On the contrary, an inadequate built environment can lead to psychological distress and mental health problems. Furthermore, higher rates of intentional injury, poor birth outcomes, cardiovascular disease, infectious diseases, physical inactivity and all-cause mortality have been observed in low-income neighborhoods (31).

Finally, how housing impacts on health will also depend on the different inequality axes. The social stratification of society is determined by the different axes of inequality, such as social class, gender, age, ethnicity or race, and territory of origin and/or residence. These axes determine hierarchies of power in society that have an impact on the opportunities to have good housing conditions and also good health. They are related with the existence of inequalities in health which have been defined as “the differences in health between socioeconomic groups that are systematic, socially produced and unfair” (39). Differences are systematic because they do not occur randomly, but have a persistent pattern in the population, affecting the most disadvantaged social groups. They are socially produced because they are the consequence of the way society functions. And they are unjust because they violate people's fundamental rights. Many studies have shown inequalities in housing, being poor housing conditions more prevalent among less privileged populations, consequently showing worse health outcomes (14, 33, 40).

Aims of the section “housing conditions and public health”

This section of the Journal aims to receive manuscripts referred to the issues commented above as well as those that provide a deep understanding of the mechanisms that explain how housing conditions are related to health outcomes and also those that show and evaluate specific housing policies and interventions with the objective to improve health outcomes and to reduce health inequalities. Submissions can be any of the following article types: Case Report, Clinical Trial, Correction, Editorial, General Commentary, Hypothesis and Theory, Methods, Mini Review, Opinion, Original Research, Perspective, Policy and Practice Reviews, Review, Systematic Review, Technology and Code, Brief Research Report, Classification, Policy Brief, Study Protocol, Community Case Study, Curriculum, Instruction, and Pedagogy, Specialty Grand Challenge, Data Report, Conceptual Analysis and Clinical Study Protocol.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Novoa AM, Bosch J, Diaz F, Malmusi D, Darnell M, Trilla C. Impact of the crisis on the relationship between housing and health. Policies for good practice to reduce inequalities in health related to housing conditions. Gac Sanit. (2014) 28(Suppl 1):44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2014.02.018

2. Borrell C, Espelt A, Rodríguez-Sanz M, Navarro V. Politics and health. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2007) 61:658–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.059063

3. Alidoust S, Huang W. A decade of research on housing and health: a systematic literature review. Rev Environ Health. (2021). doi: 10.1515/reveh-2021-0121. [Epub ahead of print].

4. Leifheit KM, Schwartz GL, Pollack CE, Linton SL. Building health equity through housing policies: critical reflections and future directions for research. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2022) 76:759–63. doi: 10.1136/jech-2021-216439

5. Lesser EP. Housing to Health: A Literature Review Analyzing Housing Pathways Policy Initiatives. Mankato, MN: Capstone Experience (2022), 194. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/coph_slce/194

6. World Health Organization. Policies, Regulations and Legislation Promoting Healthy Housing: A Review. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

7. Sharpe RA, Taylor T, Fleming LE, Morrissey K, Morris G, Wigglesworth R. Making the case for “whole system” approaches: integrating public health and housing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:2345. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112345

8. Matthews KA, Kiefe CI, Lewis CE, Liu K, Sidney S, Yunis C. Socioeconomic trajectories and incident hypertension in a biracial cohort of young adults. Hypertension. (2002) 39:772–6. doi: 10.1161/hy0302.105682

9. Evans GW, Wells NM, Moch A. Housing and mental health: a review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique. J Soc Issues. (2003) 59:475–500. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00074

10. Sandel M, Wright RJ. When home is where the stress is: expanding the dimensions of housing that influence asthma morbidity. Arch Dis Child. (2009) 91:942–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.098376

11. Taylor MP, Pevalin DJ, Todd J. The psychological costs of unsustainable housing commitments. Psychol Med. (2007) 37:1027–36. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009767

12. Bentley R, Baker E, Mason K, Subramanian SV, Kavanagh AM. Association between housing affordability and mental health: a longitudinal analysis of a nationally representative household survey in Australia. Am J Epidemiol. (2011) 174:753–60. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr161

13. Singh A, Daniel L, Baker E, Bentley R. Housing disadvantage and poor mental health: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. (2019) 57, 262–272. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.018

14. Swope CB, Hernández D. Housing as a determinant of health equity: a conceptual model. Soc Sci Med. (2019) 243:112571. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112571

15. Arundel R, Li A, Baker E, Bentley R. Housing unaffordability and mental health: dynamics across age and tenure. Int J Hous Policy. (2022) 27:1–31. doi: 10.1080/19491247.2022.2106541

16. Vásquez-Vera H, Palència L, Magna I, Mena C, Neira J, Borrell C. The threat of home eviction and its effects on health through the equity lens: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. (2017) 175:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.010

17. Dupuis A, Thorns DC. Home, home ownership and the search for ontological security. Sociol Rev. (1998) 46:24–47. doi: 10.1111/1467-954X.00088

18. Gustafsson K, Krickel-Choi NC. Returning to the roots of ontological security: insights from the existentialist anxiety literature. Eur J Int Relat. (2020) 26:875–95. doi: 10.1177/1354066120927073

19. Reyes A, Novoa AM, Borrell C, Carrere J, Pérez K, Gamboa C, Daví L, Fernández A. Living together for a better life: the impact of cooperative housing on health and quality of life. Buildings. (2022) 12:2099. doi: 10.3390/buildings12122099

20. Carrere J, Reyes A, Oliveras L, Fernández A, Peralta A, Novoa AM, et al. The effects of cohousing model on people's health and wellbeing: a scoping review. Public Health Rev. (2020) 41:22. doi: 10.1186/s40985-020-00138-1

21. Barrett P. Intersections Between Housing Affordability and Meanings of Home: A Review. Kotuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online (2022). doi: 10.1080/1177083X.2022.2090969

22. Krieger J, Higgins DL. Housing and health: time again for public health action. Am J Public Health. (2002) 92:758–68. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.5.758

23. The WHO European Centre for Environment and Health. Environmental Burden of Disease Associated with Inadequate Housing. Copenhagen: WHO (2011).

24. Hernández D, Phillips D, Siegel EL. Exploring the housing and household energy pathways to stress: a mixed methods study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2016) 13:916. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13090916

25. Saez de Tejada C, Daher C, Hidalgo L, Nieuwenhuijsen M. Vivienda y Salud Características y Condiciones de la Vivienda. Barcelona: Diputación de Barcelona (2021).

26. Oliveras L, Artazcoz L, Borrell C, Palència L, López MJ, Gotsens M, et al. The association of energy poverty with health, health care utilisation and medication use in southern Europe. SSM Popul Health. (2020) 12:100665. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100665

27. Carrere J, Peralta A, Oliveras L, López MJ, Marí-Dell'Olmo M, Benach J, et al. Energy poverty, its intensity and health in vulnerable populations in a Southern European city. Gac Sanit. (2021) 35:438–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2020.07.007

28. Hills J. Fuel Poverty: The Problem and Its Measurement—Interim Report of the Fuel Poverty Review. Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion. London: The London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton (2011).

29. Recalde M, Peralta A, Oliveras L, Tirado-Herrero S, Borrell C, Palència L, et al. Structural energy poverty vulnerability and excess winter mortality in the European Union: exploring the association between structural determinants and health. Energy Policy. (2019) 133:110869. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2019.07.005

30. Bonnefoy X. Inadequate housing and health: an overview. Int J Environ Pollut. (2007) 30:411–29. doi: 10.1504/IJEP.2007.014819

31. James C. Homes Fit for Families. An Evidence Review. Washington, DC: The Family Parenting Institute (2008). Available online at: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/4977949/homes-fit-for-families-family-and-parenting-institute (accessed October 14, 2022).

32. Lawrence RJ. Housing for health promotion. Int J Public Health. (2011) 56:577–8. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0307-z

33. The WHO European Centre for Environment and Health. Environmental Health Inequalities in Europe. Copenhagen: WHO (2012).

34. Pollack C, Egerter, S, Sadegh-Nobari, T, Dekker, M, Braveman, P. Issue Brief 2: Housing Health. Where We Live Matters to Our Health: The Links between Housing Health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2008). Available online at: http://www.commissiononhealth.org/PDF/e6244e9e-f630-4285-9ad7-16016dd7e493/Issue%20Brief%202%20Sept%2008%20-%20Housing%20and%20Health.pdf (accessed December 12, 2022).

35. Borrell C, Pons-Vigués M, Morrison J, Díez E. Factors and processes influencing health inequalities in urban areas. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2013) 67:389–91. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-202014

36. Briggs D. Environmental pollution and the global burden of disease. Br Med Bull. (2003) 68:1–24. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg019

37. Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. Influence of urban and transport planning and the city environment on cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2018) 15:432–38. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0003-2

38. Orsetti E, Tollin N, Lehmann M, Valderrama VA, Morató J. Building resilient cities: climate change and health interlinkages in the planning of public spaces. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:1355. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031355

39. Whitehead M, Dahlgren G. Concepts and principles for tackling social inequities in health: levelling up Part 1. World Health Organ Stud Soc Econ Determ Populat Health. (2006) 2:460–74.

Keywords: housing, living condition, environmental health, dwelling, inequality

Citation: Borrell C, Novoa AM and Perez K (2023) Housing conditions, health and health inequalities. Front. Environ. Health 1:1080846. doi: 10.3389/fenvh.2022.1080846

Received: 26 October 2022; Accepted: 17 November 2022;

Published: 06 January 2023.

Edited by:

Pam Factor-Litvak, Columbia University, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Borrell, Novoa and Perez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carme Borrell, Y2JvcnJlbGxAYXNwYi5jYXQ=

Carme Borrell

Carme Borrell Ana M. Novoa

Ana M. Novoa Katherine Perez

Katherine Perez