- 1Department of Otolaryngology, Hannover Medical School, Hanover, Germany

- 2Cluster of Excellence “Hearing4all”, Hannover Medical School, Hanover, Germany

- 3Advanced Bionics GmbH, European Research Center, Hanover, Germany

Objective: To evaluate the feasibility and reliability of a smartphone-based, self-administered matrix sentence test for assessing speech perception in cochlear implant (CI) users, and to compare its outcomes with those of the standard clinical Oldenburg Sentence Test (OLSA) in free-field conditions.

Methods: Nineteen adult CI users (12 experienced, 7 newly implanted) completed a standard open-set OLSA testing and a closed-set version using a research smartphone app with direct Bluetooth streaming to their hearing devices in a sound-treated room. The app presented five response alternatives per sentence and estimated speech reception thresholds (SRTs) at 60% word recognition to account for increased chance level. Test-retest differences and between-group effects were analyzed using mixed-model ANOVA and post hoc t-tests.

Results: All participants were able to complete the smartphone-based test independently. SRTs obtained via the app showed strong agreement with clinical measures, particularly among experienced users. Larger deviations were observed in three newly implanted participants. The ANOVA revealed a significant effect of experience level (p = 0.02), but no effect of test method and no interaction. Usability was rated high, and the simplified five-option interface was well tolerated across age groups.

Conclusion: The results demonstrate that smartphone-based matrix sentence testing with direct audio streaming is a feasible and reliable method for assessing speech-in-noise perception in CI users. This approach offers potential for remote monitoring and self-assessment beyond the clinical setting.

1 Introduction

Speech intelligibility is a key outcome measure in evaluating the success of individuals receiving cochlear implant (CI). As CI users adapt to the electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve, speech perception tests are routinely administered, initially during device activation and subsequently at follow-up visits to monitor their progress (Baumann et al., 2025). However, challenges arise in more complex acoustic settings with background noise, where many users experience difficulties in understanding speech (Hey and Hoppe, 2025; Zaltz et al., 2020).

The matrix sentence test, introduced by Wagener et al. (1999c,a,b) as the Oldenburg sentence test (OLSA) for the German language, is utilized in both research and clinical contexts, to assess hearing performance in challenging listening conditions with background noise in different languages (Kollmeier et al., 2015). The matrix sentence test is a fast and reproducible method for measuring speech intelligibility in noise using semantically unpredictable five-word sentences, such as “Nina gives seven old chairs.” The test determines the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) at which 50% of the speech material is understood, known as the speech reception threshold (SRT). The OLSA is typically administered in an open-set format, where participants repeat the sentences aloud and the responses are scored by an examiner. Alternatively, a closed-set format displays 10 response options, including the correct one, for visual selection. Both formats yield comparable outcomes (Brand et al., 2004; Holube et al., 2009). The OLSA uses speech-modulated stationary noise (OLnoise) as a masker, which yields a steep discrimination function, as well as high sensitivity and reproducibility of test results (Wagener and Brand, 2005) SRTs are usually calculated by fitting a psychometric function to each individual's performance data (Brand and Kollmeier, 2002).

The matrix sentence test is available in multiple languages (Kollmeier et al., 2015), making it well-suited for use in smartphone-based applications with global reach. Thanks to its standardized structure and validated translations, data can be reliably pooled across languages, enabling cross-linguistic comparisons and multinational performance studies. With modern smartphones, the test signals can be streamed directly to hearing aids (HA) or CI processors, enabling users to complete speech perception assessments independently at home, tasks that were previously limited to clinical environments.

Saak et al. (2025) investigated three user interfaces for conducting the matrix sentence test via smartphone: a slider interface, where users indicated how many words they had understood; a typing interface, in which participants manually entered their responses; and a wheel interface, which allowed sentence selection by rotating through options. All were compared against a ten-option matrix interface, a closed-set format in which participants selected the correct sentence from 10 alternatives. This differs from standard clinical practice, where the matrix sentence test is typically administered in an open-set format, requiring participants to repeat sentences aloud without visual prompts.

Among the tested interfaces, the ten-option matrix format yielded the most consistent SRTs relative to laboratory-based open-set testing. However, the alternative formats were rated by some participants as more intuitive or faster to use, despite slightly reduced measurement precision. Saak et al. (2025) noted that the slider interface may be particularly suitable for users with visual or tactile limitations.

Although Saak et al. (2025) did not evaluate a simplified version of the matrix interface, we identified a five-option matrix format as a viable alternative in an in-house pilot trial. This version reduces visual and cognitive load while maintaining the closed-set structure and may thus improve usability in smartphone-based self-assessment without compromising test validity.

In this feasibility study, we evaluated whether CI users can effectively operate a smartphone-based matrix sentence test interface and whether the resulting SRTs are reliable. Participants were divided into two groups: experienced users with bilateral or bimodal CIs who were already familiar with clinical speech testing, and inexperienced users who were still in the early stages of adapting to electrical hearing. As the app is intended for broad applicability, it was essential to assess usability and reliability across both groups.

2 Methods

2.1 Study participants

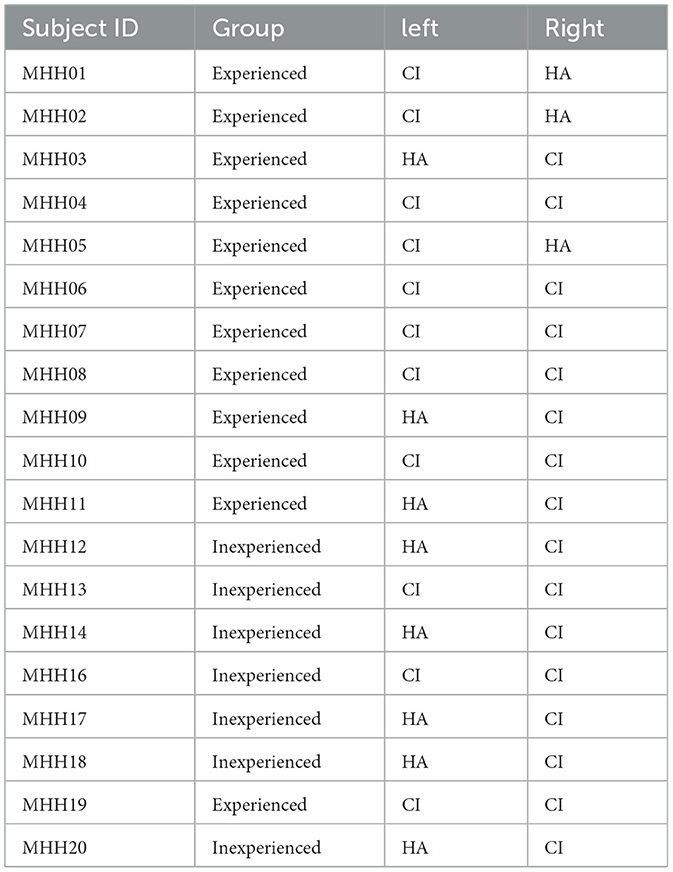

The study included a total of 20 adults using either two CIs (bilateral) or one CI and one HA (bimodal). For one participant, the matrix sentence test proved to be too challenging, resulting in no available data. In the following, data from 19 subjects will be presented.

To be a study candidate, participants were required to have a CI from Advanced Bionics (Clarion II or later) and to use either the HiRes Fidelity 120 or HiRes Optima sound coding strategy. In bimodal users, hearing thresholds on the acoustic ear were required to be no worse than 80 dB HL between 250 Hz and 1 kHz. Additionally, all participants were required to be at least 18 years old and to have experience using smartphones, defined as using at least one app per day.

Two groups of CI users participated in the study: an experienced group (N = 12) with a mean CI experience of 7.7 years (SD = 6.5), and an inexperienced group (N = 7) with a mean duration of 0.7 years (SD = 1.4) since implantation. Some participants in the inexperienced group were tested only a few days after initial activation.

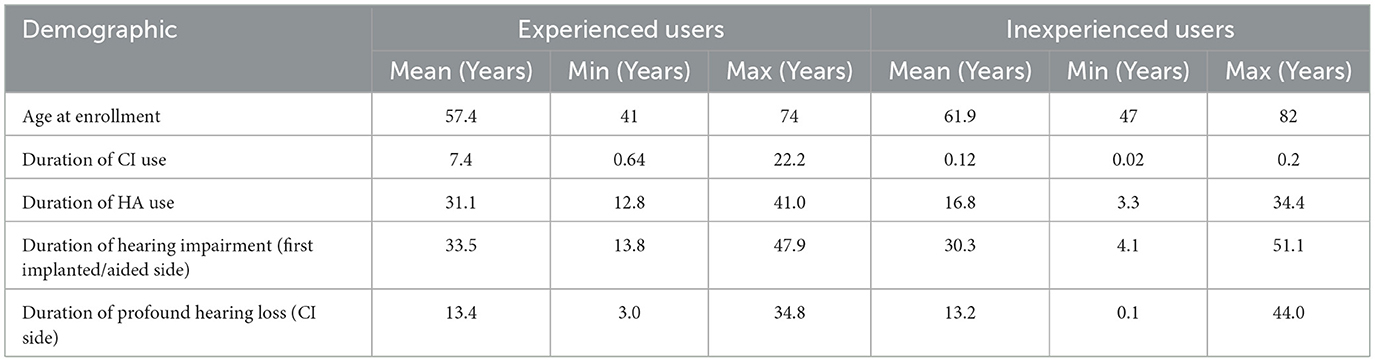

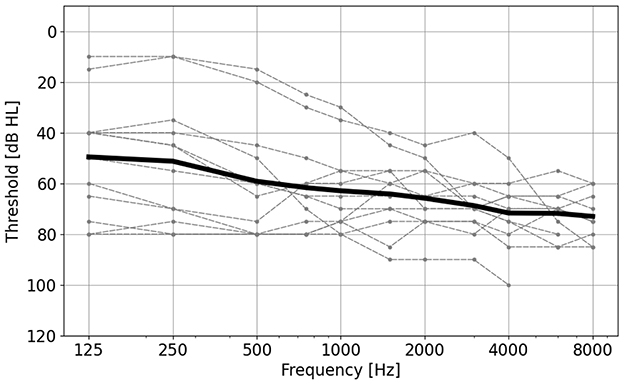

Demographic data are summarized in Table 1. Seven participants were bilateral CI users, and 12 were bimodal users. Table 2 provides details on device configuration for each ear. All bimodal participants were fitted with a Phonak Naída Link M hearing aid for the study. Their hearing thresholds on the acoustic side were ≤ 80 dB HL between 250 Hz and 1 kHz (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Audiograms of all 12 bimodal participants for the HA side (gray lines), as well as the mean (black line).

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Hannover Medical School (protocol code 9645_B0_S_2021).

2.2 Research app

The matrix sentence test was implemented in a research smartphone application previously described by Kliesch et al. (2023, 2024). The app was developed for the Apple iOS platform (version 15 or later) and transferred to dedicated study iPhones using Apple's TestFlight testing environment (version 3.2.2 or later), as it was not available through the App Store at the time of the study.

After pairing the app with the CI or HA via Bluetooth, participants were able to complete the matrix sentence test [OLSA; (Wagener et al., 1999c)] using direct audio streaming. Instead of presenting speech and background noise (OLnoise) through loudspeakers, the test material was streamed directly into the hearing devices. Because both CI processors and HAs are calibrated systems, the app ensures accurate presentation levels through fixed calibration of the Bluetooth input signal. SRTs were determined by fitting a psychometric function to the performance data of each participant, as in the standard OLSA procedure.

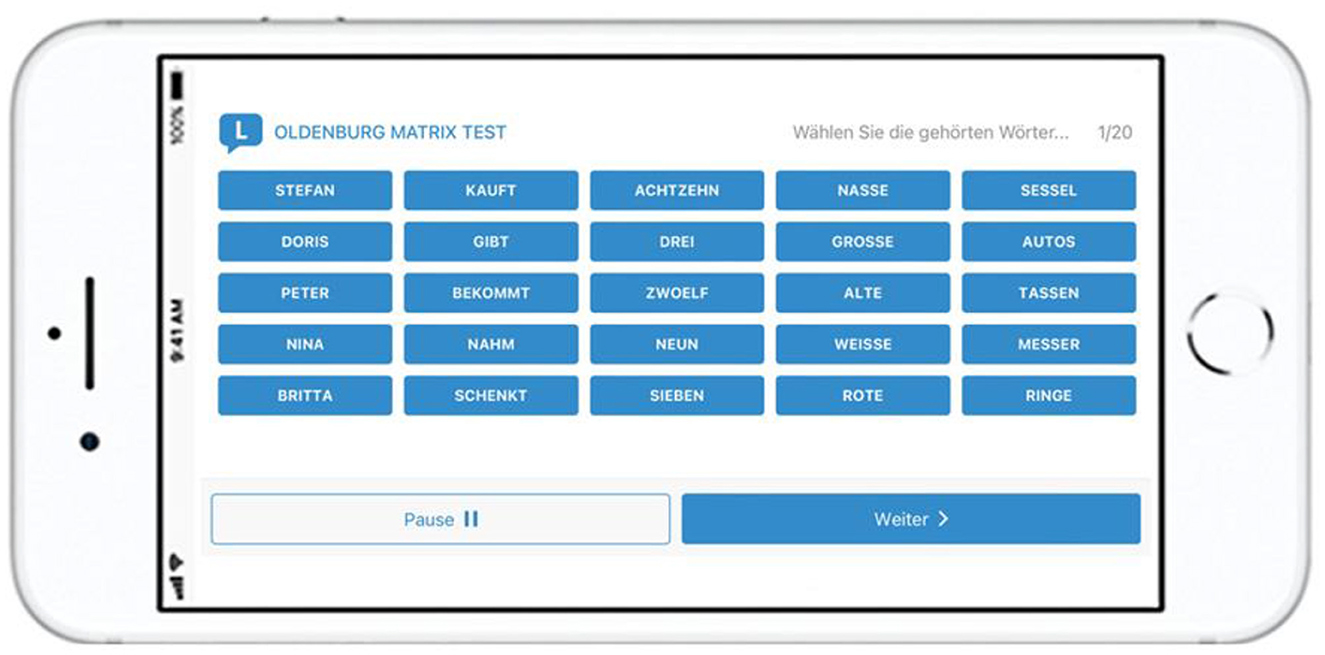

The test was implemented in a closed-set format: after hearing each sentence, participants selected the perceived sentence from multiple-choice options displayed on the smartphone screen (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. This figure shows the German Oldenburg matrix sentence test as implemented in the research app. The participants can select the words they believe they have understood.

As shown in Figure 2, only five sentence options were presented on the smartphone screen, fewer than in the original closed-set OLSA format, which typically displays 10 alternatives (Holube et al., 2009; Wagener et al., 1999c). This reduction was necessary due to limited screen space on smartphones: displaying 10 options would have resulted in text items too small for many users, particularly older participants, to read and select comfortably.

Reducing the number of response alternatives from ten to five increases the chance level of a correct guess from 10% to 20%, potentially biasing the results toward artificially improved (i.e., lower) SRTs. To counteract this, the app computes the SRT at 60% word recognition rather than the conventional 50%. This adjustment ensures that participants must understand a greater proportion of the sentence material, thereby compensating for the increased chance level and resulting in poorer (i.e., higher) SRTs.

2.3 Study procedure

All participants were provided with a smartphone preloaded with the research app. If their own hearing devices were not compatible with direct Bluetooth streaming (e.g., due to older-generation hardware), they were temporarily equipped with Advanced Bionics Naída CI M speech processors and, in the case of bimodal users, a Phonak Naída Link M hearing aid. The CI processors were programmed with each participant's individual clinical MAP using the Target CI software. The HAs were adjusted according to the participants' audiometric profiles by a clinical engineer. Individual earmolds were used for coupling.

Participants were instructed by the investigator on the use of the smartphone, the research app, and the matrix sentence test. All measurements were conducted in a sound-treated room during a single study appointment. This included Step 1: unaided (for the acoustic ear in bimodal users) and aided audiometric thresholds for all participants; Step 2: free-field OLSA testing as the gold standard; Step 3: smartphone-based speech perception tests. In the free field condition, both speech and noise were presented from the front (S0N0) at a distance of one meter. For the streaming condition, the audio signal was streamed to both ears: either to two CI processors or to one CI processor and one HA in bimodal users. For the speech perception assessment, hearing devices were manually set to “Speech in Quiet” with an omnidirectional microphone setting. The speech perception test was conducted with noise fixed at 65 dB SPL, using an adaptive speech level and a starting SNR of 0 dB.

3 Results

This section reports the results of a comparative analysis of speech perception outcomes obtained with the smartphone-based matrix sentence test and the standard laboratory-based OLSA, across two participant groups differing in CI experience.

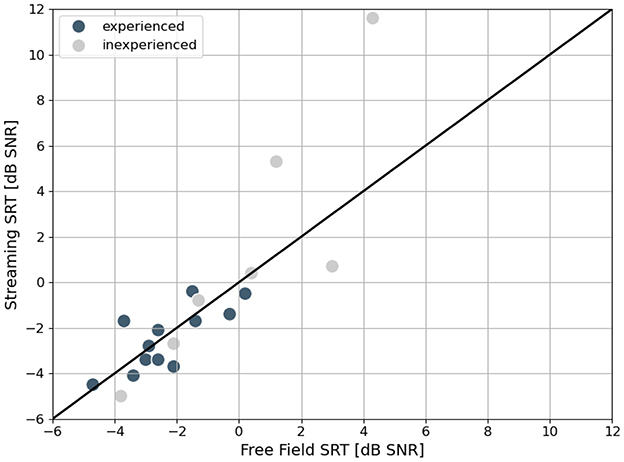

Figure 3 shows a scatter plot comparing SRTs obtained via the app with those measured in the laboratory. Overall, data points are closely aligned with the diagonal, indicating good agreement between methods. In the inexperienced group, however, three data points deviate more substantially. Two of these correspond to participants tested within the first week after CI activation, while the third outlier represents the oldest participant in the study (82 years), who also belonged to the inexperienced group with 6 weeks of CI experience.

Figure 3. Scatterplot showing results of the free field SRTs on the x axis and the results of the streaming SRTs on the y axis. The black diagonal line indicates perfect correlation between both measurements. Dark gray dots indicate experienced CI users, light gray dots inexperienced CI users.

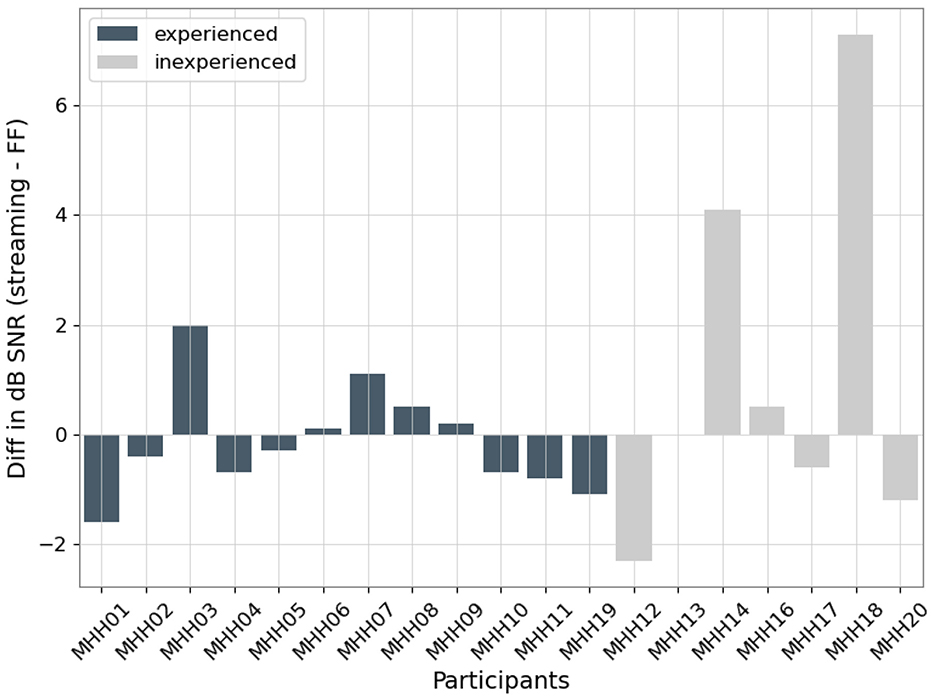

This pattern is also visible in Figure 4, which shows the individual differences between the two test conditions. In the experienced group, differences remained below 2.5 dB for all participants, whereas the three inexperienced users described above showed larger discrepancies.

Figure 4. Bar plot showing individual differences between speech intelligibility measures performed in free field (FF) in the lab and via streaming using the smartphone app.

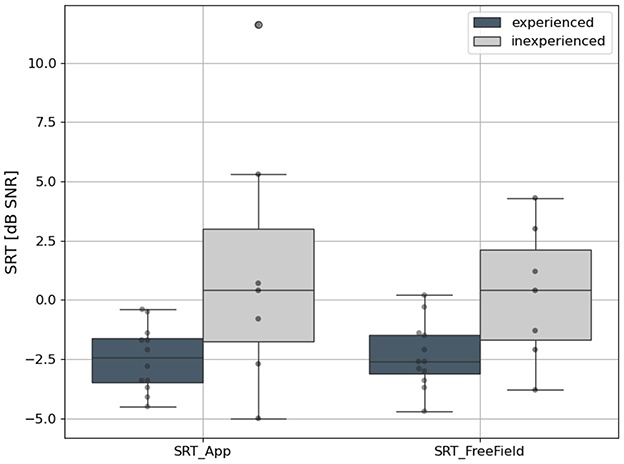

Figure 5 presents the results as box plots, showing median values along with the 25th and 75th percentiles. Median SRTs were comparable between the two test methods in both groups. A mixed-model ANOVA (implemented using Python with the pingouin package) revealed no significant interaction between participant group (experienced vs. inexperienced) and measurement method (lab vs. app): F(1, 17) = 1.49, p = 0.239. However, there was a significant main effect of participant group [F(1, 17) = 6.56, p = 0.02], indicating overall better performance in the experienced group, independent of test method. No main effect was observed for measurement method alone.

Figure 5. Boxplot showing SRTs for all participants displaying the 25th and 75th quartiles, and the median (represented by a continuous line). Results for the experienced CI users are shown in black and results for the inexperienced users are shown in gray. All individual SRTs are displayed by gray dots.

A post hoc one-sided t-test confirmed a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.042), consistent with the expectation that experienced users would show lower SRTs.

4 Discussion

This feasibility study evaluated a smartphone-based research application for measuring speech intelligibility in noise among CI users. Speech perception outcomes obtained via the app, using direct Bluetooth streaming into CI processors and HAs, were compared to standard free-field measurements using the OLSA. All participants were able to complete the app-based test independently, including the oldest participant at 82 years of age, indicating good usability across age groups. Only one subject had to be excluded, not due to difficulties with the app interface, but because no reliable SRT could be obtained (SRT > 15 dB SNR).

The app implemented a closed-set matrix interface displaying five sentence alternatives per trial. Saak et al. (2025) compared various smartphone-based test interfaces. Among them, the traditional ten-item matrix format yielded the most consistent SRTs, fastest completion times, and highest user preference ratings. However, they reported that one older participant struggled with the interface due to small on-screen buttons, raising concerns about its suitability for users with visual or tactile impairments. By reducing the number of options displayed to five, our study allowed for larger selection fields, potentially improving accessibility without compromising the test's closed-set structure. To account for this change, we increased the SRT to 60%.

The results demonstrated strong agreement between laboratory- and app-based SRTs, particularly among experienced CI users. In contrast, three of the seven inexperienced participants showed larger deviations, two of whom had been tested only a few days after initial CI activation. This suggests that early post-implant variability may influence performance in both test conditions. However, a larger sample is needed to better understand the impact of activation time on measurement variability. Overall, these findings support the feasibility and reliability of the smartphone-based matrix test and indicate its potential applicability across CI users with different levels of experience.

Extending the smartphone-based testing approach to other devices is an important consideration for broader implementation. As HAs and CIs are calibrated devices, adaptation to other manufacturers is expected to be relatively straightforward, particularly for users with bilateral provisions and a unified Bluetooth connection. For bimodal users, coordinated Bluetooth transmission to both devices is essential, as demonstrated in this study with Advanced Bionics implants and Phonak Link hearing aids. These challenges are largely technical and can be addressed through device-specific calibration, standardized streaming interfaces, or collaboration with manufacturers.

Finally, it is worth noting that streaming may offer a more controlled and reproducible presentation level than free-field testing, which can be affected by factors such as head position, ambient acoustics, and room reverberation. In this sense, smartphone-based testing could complement clinical assessments by enabling high-quality, standardized evaluations outside the clinic.

5 Limitations

This study identifies several limitations that could influence the interpretation and generalization of the findings:

Test Order: There was no randomization of the test order. The free-field measurement was always conducted first as part of routine clinical testing, followed by the app-based assessment during the same appointment. However, since participants completed a training list prior to testing, and the adaptive OLSA minimizes learning effects, a systematic bias due to test order is unlikely (Wagener et al., 1999b; Wagener and Brand, 2005).

Small Sample Size: The study included only data from 19 participants, limiting the statistical power and generalizability of the results. The small sample size, particularly after dividing participants into experienced and new CI users, further reduces generalizability. Moreover, the considerable variability among new CI users complicates interpretation of the results.

Given the feasibility nature of this study, the limitations emphasize the need for follow-up research to confirm and extend these results. Expanding validation across different devices and lager study groups will be essential for broader clinical adoption.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Ethics Committee of Hannover Medical School (protocol code 9645_B0_S_2021 approved on 17. March 2021). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. MS: Writing – original draft. TL: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors declare that this study received funding from Advanced Bionics GmbH. Employees of this company were involved in the conceptualization, methodology, and software development steps (see also Author Contributions). No employees of the company were involved in the data collection, data analysis and data interpretation steps. This study was also funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany's Excellence Strategy -EXC 2177/1 -Project ID 390895286.

Conflict of interest

MB and MS were employed by Advanced Bionics GmbH.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Baumann, U., Weißgerber, T., and Hoppe, U. (2025). Anpassung von Cochleaimplantatsystemen. HNO 73, 335–356. German. doi: 10.1007/s00106-025-01593-5

Brand, T., and Kollmeier, B. (2002). Efficient adaptive procedures for threshold and concurrent slope estimates for psychophysics and speech intelligibility tests. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 111, 2801–2810. doi: 10.1121/1.1479152

Brand, T., Wittkop, T., Wagener, K., and Kollmeier, B. (2004). Vergleich von Oldenburger Satztest und Freiburger Wörter- test als geschlossene Versionen 7. Leipzig: DGA Jahrestagung.

Hey, M., and Hoppe, U. (2025). Management of audiological disorders in cochlear implants: outcomes in demanding listening situations and future perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 14:2089. doi: 10.3390/jcm14062089

Holube, I., Blab, S., Fürsen, K., Gürtler, S., Meisenbacher, K., Nguyen, D., et al. (2009). Einfluss des Maskierers und der Testmethode auf die Sprachverständlichkeitsschwelle von jüngeren und älteren Normalhörenden. Z. Audiol. 48, 120–127. German.

Kliesch, S., Chalupper, J., Lenarz, T., and Büchner, A. (2023). Evaluation of two self-fitting user interfaces for bimodal CI-recipients. Appl. Sci. 13:8411. doi: 10.3390/app13148411

Kliesch, S., Chalupper, J., Lenarz, T., and Büchner, A. (2024). App-based self-adjustment - user behavior and adjustment practices of cochlear implant users in everyday life. Appl. Sci. 14:11708. doi: 10.3390/app142411708

Kollmeier, B., Warzybok, A., Hochmuth, S., Zokoll, M. A., Uslar, V., Brand, T., et al. (2015). The multilingual matrix test: principles, applications, and comparison across languages: a review. Int. J. Audiol. 54 (Suppl. 2), 3–16. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2015.1020971

Saak, S., Kothe, A., Buhl, M., and Kollmeier, B. (2025). Comparison of user interfaces for measuring the matrix sentence test on a smartphone. Int. J. Audiol. 64, 745–757. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2024.2385551

Wagener, K. C., and Brand, T. (2005). Sentence intelligibility in noise for listeners with normal hearing and hearing impairment: influence of measurement procedure and masking parameters. Int. J. Audiol. 44, 144–156. doi: 10.1080/14992020500057517

Wagener, K. C., Brand, T., and Kollmeier, B. (1999a). Entwicklung und Evaluation eines Satztests in deutscher Sprache Teil II: optimierung des Oldenburger Satztests [Development and evaluation of a German sentence test Part II: optimization of the Oldenburg sentence test]. Z. Audiol. 38, 44–56. German.

Wagener, K. C., Brand, T., and Kollmeier, B. (1999b). Entwicklung und Evaluation eines Satztests für die deutsche Sprache Teil III: evaluation des Oldenburger Satztests [Development and evaluation of a German sentence test Part III: evaluation of the Oldenburg sentence test]. Z. Audiol. 38, 86–95. German.

Wagener, K. C., Kühnel, V., and Kollmeier, B. (1999c). Entwicklung und Evaluation eines Satztests für die deutsche Sprache I: design des Oldenburger Satztests [Development and evaluation of a German sentence test I: design of the Oldenburg sentence test]. Z. Audiol. 38, 4–15. German.

Zaltz, Y., Bugannim, Y., Zechoval, D., Kishon-Rabin, L., and Perez, R. (2020). Listening in noise remains a significant challenge for cochlear implant users: evidence from early deafened and those with progressive hearing loss compared to peers with normal hearing. J. Clin. Med. 9:1381. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051381

Keywords: matrix sentence test, remote audiology, cochlear implant, Oldenburg sentence test, MHealth (mobile Health)

Citation: Kliesch S, Brendel M, Schulte M, Lenarz T and Büchner A (2025) Comparison of app-based and clinically administered matrix sentence tests in cochlear implant users. Front. Audiol. Otol. 3:1693547. doi: 10.3389/fauot.2025.1693547

Received: 27 August 2025; Accepted: 31 October 2025;

Published: 21 November 2025.

Edited by:

Meisam Arjmandi, University of South Carolina, United StatesReviewed by:

Brian Richard Earl, University of Cincinnati, United StatesGavriel Kohlberg, University of Washington, United States

Copyright © 2025 Kliesch, Brendel, Schulte, Lenarz and Büchner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sven Kliesch, S2xpZXNjaC5zdmVuQG1oLWhhbm5vdmVyLmRl

Sven Kliesch

Sven Kliesch Martina Brendel

Martina Brendel Michael Schulte

Michael Schulte Thomas Lenarz

Thomas Lenarz Andreas Büchner

Andreas Büchner