- 1Graduate School of Social Work, University of Denver, Denver, CO, United States

- 2Shopworks Architecture, Denver, CO, United States

This article presents the Dignified Design Assessment Tool (DDAT), a measurement instrument that captures the concept of dignified design in the design and development of affordable housing. Dignified design is the conceptual model and within this conceptual model is the trauma informed design (TID) framework. The TID framework is now widely used in affordable housing development. This article provides an illustration and test of the content validity of the TID framework. Then, the article concludes by presenting the four item DDAT, which uses 100 word narrative responses. Instructions for administering the DDAT, and DDAT scoring guidance, are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Introduction

The built environment, particularly housing, is a critical factor in individual health and well-being (1). However, housing costs in the United States have reached crisis levels, with over 50% of renters now classified as cost-burdened (2). At the same time, the housing industry faces increasing pressure to produce more homes at lower costs. A significant unintended consequence of building more housing under these financial constraints, especially when material prices are high, is the construction of unsustainable housing that harms rather than supports well-being (3). This issue is particularly pronounced in the development of affordable housing where health-promoting design features (4) are often sacrificed to meet the limitations of housing finance systems that rely on subsidies.

Despite the challenges of designing and building sustainable housing that promotes healing and thriving, Dignified Design has emerged as a popular and empirically supported approach, particularly in the field of affordable housing. Dignified Design is an approach that promotes the health and thriving of permanent supportive housing (PSH) end users, recognizing that modern life is stressful, and the built environment can play a critical role in supporting psychological and somatic regulation. As an ideal, Dignified Design aims to create places that protect, promote, and celebrate the dignity of life—“dignity” defined as a fundamental state of being and a quality of humanness inherent to everyone. Dignified Design is being adopted in states like Colorado, Oregon, Florida, and others. However, the dignified design research field needs to provide ways for stakeholders to measure, implement, and test the impact of this approach to affordable housing design and construction.

This research brief introduces the Dignified Design Assessment Tool (DDAT), a four-item, narrative-response measure of Dignified Design. The DDAT plays a crucial role in advancing both the understanding and adoption of Dignified Design practices. It offers a versatile method for measuring Dignified Design across various stakeholders. For affordable housing design and development teams, the DDAT serves as a tool to assess the extent and quality of Dignified Design in project plans. For affordable housing finance, it provides a standardized way to evaluate and score dignified design in proposed developments—such as its potential integration into Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) Qualified Allocation Plans (QAPs). Finally, for affordable housing program staff and researchers, the DDAT offers a means to assess the impact of housing design and the built environment on residents' health and well-being.

Trauma informed design is now dignified design

The DDAT is used as a measure of our dignified design model. Our dignified design model is an evolution of our initial Trauma-Informed Design (TID) framework (4). The TID framework was rooted in the trauma-informed care literature (5), which emphasizes six core concepts: (1) safety; (2) trustworthiness and transparency; (3) peer support; (4) collaboration and mutuality; (5) empowerment, voice and choice; and 6) cultural, historical and gender issues. As such, the TID framework centers the corresponding principles of safety and the “three C's"—community, comfort, and choice.

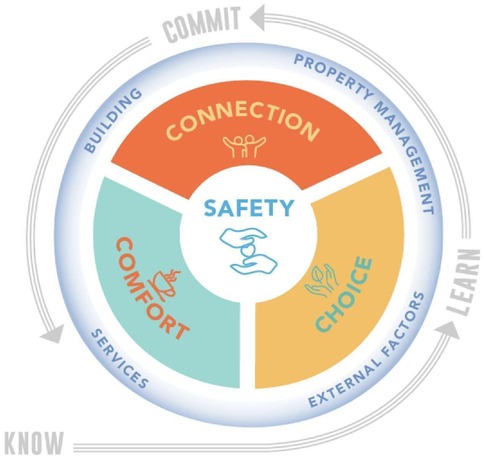

Figure 1 provides an illustration of our TID framework, which serves as the basis for the DDAT. At the center of the TID framework are the four core principles of safety and the three C's—comfort, connection, and choice. Safety serves as the primary value and focus of dignified design. Without some sense of safety, experiences of comfort, connection, and choice cannot be fully accessed.

Safety and the three C's exist within a larger framework describing the dignified design context. The extent to which the four core principles are experienced depends not only on the building itself but also on the nature and quality of onsite services and property management. As such, a dignified design approach to both service delivery and property management is also critical. Additionally, external factors, including the historical, ecological, and cultural context of the building's physical and temporal location, must be considered. Ideally, these various contextual influences are viewed through a holistic and responsive lens that recognizes the interconnectedness of factors on the health and well-being of residents and staff. The TID framework is then held and guided by an ongoing process we refer to as know–learn–commit, which describes the role and responsibility of design professionals and other decision-makers in the building development process.

DDAT for subsidized housing finance decision making

The DDAT is valuable to a wide range of stakeholders. Primarily, it can serve as a scoring tool to evaluate the merits of affordable housing projects when competing for housing finance subsidies. For instance, in a state's competitive LIHTC process, the DDAT can be embedded directly into the LIHTC QAP and scored by housing finance authority staff. In this manuscript, we provide scoring guidance for stakeholders interested in embedding the DDAT in their work. Design and development teams can also use the DDAT to conduct self-assessments, evaluating the success of dignified design elements in their building plans. Additionally, affordable housing staff and researchers can employ the DDAT to examine the impact of design on the health and well-being of residents and staff.

Research purpose

Create a dignified design measurement tool.

Methods

Study setting

This measurement study is conducted in Colorado in partnership with an architectural firm involved in design teams that submit QAPs for Colorado's LIHTC applications. We utilize the Colorado LIHTC QAP process to aid in the development and validation of our Dignified Design Assessment Tool (DDAT).

The Colorado Housing Finance Authority (CHFA) manages the state's low-income housing tax credits, overseeing the creation and updating of the QAP, the review of applications, and the distribution of funds.

In 2021 CHFA began requiring all permanent supportive housing (PSH) projects pursuing LIHTC funding to respond to questions about trauma-informed design (TID) and how the principles and processes of TID were incorporated in the design and development of the project.

In the Colorado LIHTC QAP, newly added questions directly related to TID are as follows:

• “If the project is serving Persons experiencing Homelessness or Special Populations, describe how the proposal follows best practices (trauma-informed design, funding for services, experience, etc.).”

• “Describe the outreach to the community that you have done and describe local opposition and/or support for the project (including financial support).”

Content validity

Our first step in creating the DDAT was to validate the TID framework, which provides the conceptual underpinnings of the assessment tool. We verified content validity of the TID framework by analyzing how themes from the LIHTC QAP applications align with the conceptual model presented in Figure 1. To achieve this, we extracted data from all LIHTC QAP application narratives submitted between 2021, when the TID questions were added to the Colorado LIHTC QAP, through the first round of 2024. Two rounds of LIHTC CAP narratives were extracted each calendar year (with the exception of 2024), resulting in a total of seven rounds of application narratives for analysis. All extracted application narratives were consolidated into a single document for analysis. This document included the following categories: (1) the name of the project as listed on the application; (2) an indication of whether the project was a hybrid [30%–80% Area Median Income (AMI)] or fully permanent supportive housing; (3) narratives for the following sections: amenities, services, community engagement, and other TID elements; and (4) narratives screened by a project research assistant that contained information on safety, comfort, connection, and choice.

DDAT item development

After assessing the content validity of the Dignified Design framework, we proceeded with the development of items for the DDAT. Experts on our team generated initial items based on the dignified design conceptual model and the TID framework.

Analysis

Analysis for content validity of the TID framework consisted of coding extracted LIHTC QAP narratives. a priori codes for the analysis were safety, comfort, connection, choice and resident participation. Qualitative coders were also instructed to use open coding for any additional categories they found relevant to the TID framework. Three analysts independently coded the extracted narrative data. Following this, the three coders compared their codes and themes to identify coding convergence and confirm the content validity of the Dignified Design conceptual model and the TID framework.

For the development of the DDAT items, a team of four Dignified Design experts reviewed and critiqued the initial items. Based on this review and critique, revised DDAT items were generated and are presented in this manuscript.

Results

Content validity of the TID framework

We reviewed seven rounds of Colorado LIHTC application narratives between 2021 and 2024. Of the 152 reviewed applications, a total of 38 applications were identified as dedicated PSH builds, meeting criteria for continued analysis. Those 38 applications were reviewed and coded to assess the validity of the Dignified Design conceptual model and the TID framework. The extracted text for each LIHTC QAP application were approximately 100–200 words and tended to have broad descriptions, not providing specifics on the way safety, comfort, connection and choice were incorporated in the design.

Initial coding confirmed that the concepts of safety, comfort, connection, and choice were present in narrative responses to Colorado LIHTC QAP applications. The most frequently mentioned theme in the LIHTC QAP narratives was “safety”, with applicants discussing how the housing design and development team is addressing safety through both physical security measures and policies, like trauma-informed care management. The presence of the a-priori codes of safety, comfort, connection and choice in LIHTC Qap application narratives confirms content validation for the DD conceptual model and TID framework.

Very few applicants discussed whether and how they engaged end users, specifically potential residents or staff. In their responses to questions about community engagement, narratives primarily referenced outreach efforts to neighborhood associations and local nonprofits rather than to end users. The research team noted that several PSH applicants who they knew had implemented a comprehensive end user engagement process failed to mention it in their application narratives.

Knowing that several project narratives were written without design team engagement in a formal Dignified Design training, may show that project teams may be implementing TID framework concepts without formal dignified Design training. Additionally, TID framework concepts may be part of design decisions, but without fully integration of the concepts within the Dignified Design conceptual model. For example, while air conditioning units and operable windows may provide “choice” in terms of temperature control and air flow, these are standard practices in the field that do not necessarily reflect dedicated or nuanced attention to Dignified Design. Similarly, a project narrative may have highlighted security measures, such as fob access and building cameras, without addressing the influence of those elements on psychological safety or ontological security.

DDAT item generation

Following the confirmation of content validity for the TID conceptual model, four items for the DDAT were drafted, with scores for each item ranging from 1 to 9. The initial draft of the DDAT was then reviewed and critiqued by five TID experts. Based on their feedback, the original items were simplified and made more specific to ensure that each question addressed only one concept. The final version of the DDAT, along with the DDAT scoring guidance, is presented in the Supplementary Material.

The DDAT is constructed as a four-item assessment tool. Items on the assessment are as follows:

• Q1. End User Engagement. Please describe how you engaged end users (including current or “potential” residents1) in your design plan?

• Q.2. Safety, Comfort, Connection, Choice. Please describe how the dignified design concepts of safety, comfort, connection and choice are integrated and embedded in your design?

• Q3. Context: Building, Property Management, External Factors and Services. Please describe design decisions that incorporated the building context, including: (1) the surrounding community; (2) property management; (3) external factors; and (4) services/staff?

• Q4. Know-Learn-Commit. Please describe how you and your team have engaged in the dignified design Know-Learn-Commit process?

Items are scored on a scale of 0 to 4 with 0 indicating a low score and 4 indicating a high score. Scaling anchors for scores of 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 can be found in the DDAT included in the Supplementary Material.

Discussion and conclusions

The TID conceptual framework was found to have content validity based on the coding of seven rounds of Colorado's LIHTC QAP extracted narratives. One interesting finding from the QAP narrative coding was that several design teams engaged end users in their design processes but did not document this engagement in their QAP narratives. This suggests that the instructions in LIHTC QAP applications can be more explicit regarding the importance of end user engagement in Dignified Design.

Once content validity was established, experts in the Dignified Design field generated the four item DDAT. The DDAT is intended to assess Dignified Design within the affordable housing sector. The DDAT and its scoring guidance are presented in the Supplementary Material.

Next steps for DDAT research include (1) feasibility testing of the DDAT; and (2) assessment of the DDAT criterion-related validity. These steps can be undertaken concurrently as partners in the affordable housing field adopt the DDAT into their practices. One anticipated way for the DDAT to be integrated into practice is as part of state QAPs for LIHTC applications.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Denver Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BM: Writing – review & editing. LR: Writing – review & editing. CH: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We are thankful for the funding support of Kaiser Foundation and the Sozosei Foundation. Without their support, we could not have completed this research.

Conflict of interest

Authors JW, RM, LR and CH were employed by company Shopworks Architecture.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used in the final editing of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvh.2025.1546442/full#supplementary-material

Footnote

1. ^potential residents are a similar population to the residents you will be serving on this project.

References

1. Koeman J, Mehdipanah R. Prescribing housing: a scoping review of health system efforts to address housing as a social determinant of health. Popul Health Manag. (2021) 24(3):316–21. doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0154

2. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. (2024). The State of the Nation’s Housing 2024. Available at: https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/reports/files/Harvard_JCHS_The_State_of_the_Nations_Housing_2024.pdf (Accessed on March 19, 2025).

3. Breysse P, Farr N, Galke W, Lanphear B, Morley R, Begofskly L. The relationship between housing and health: children at risk. Children’s Health. (2004) 112(15):1583–88. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7157

4. Shopworks Architecture, Group 14 Engineering & University of Denver. (2020). Designing for healing, dignity, & joy: Promoting physical health, mental health, and well-being through a trauma-informed approach to design. https://shopworksarc.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Designing_Healing_Dignity.pdf#:∼:text=Our%20aim%20is%20to%20create,which%20all%20people%20can%20thrive. (Accessed on March 19, 2025).

Keywords: dignified design, trauma informed design, affordable housing, permanent supportive housing, homelessness

Citation: Brisson D, Wilson J, Macur R, Mann B, Rossbert L and Holtzinger C (2025) Dignified design assessment tool. Front. Environ. Health 4:1546442. doi: 10.3389/fenvh.2025.1546442

Received: 16 December 2024; Accepted: 5 May 2025;

Published: 21 May 2025.

Edited by:

Prudence Khumalo, University of South Africa, South AfricaReviewed by:

Medani Bhandari, Akamai University, United StatesStormy Monks, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, United States

Copyright: © 2025 Brisson, Wilson, Macur, Mann, Rossbert and Holtzinger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniel Brisson, ZGFuaWVsLmJyaXNzb25AZHUuZWR1

Daniel Brisson

Daniel Brisson Jennifer Wilson2

Jennifer Wilson2