Abstract

Sound localization requires rapid interpretation of signal speed, intensity, and frequency. Precise neurotransmission of auditory signals relies on specialized auditory brainstem synapses including the calyx of Held, the large encapsulating input to principal neurons in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB). During development, synapses in the MNTB are established, eliminated, and strengthened, thereby forming an excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) synapse profile. However, in neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), E/I neurotransmission is altered, and auditory phenotypes emerge anatomically, molecularly, and functionally. Here we review factors required for normal synapse development in this auditory brainstem pathway and discuss how it is affected by mutations in ASD-linked genes.

Introduction

Neurodevelopmental disorders with auditory phenotypes, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and schizophrenia (SZ), display altered balance of excitatory and inhibitory (E/I) neurotransmission throughout the brain. Sound localization depends on the E/I ratio in auditory brainstem nuclei and higher auditory structures. Errors in neurotransmission lead to altered signal speed, strength, duration, and ultimately signal interpretation. A consequence of these E/I neurotransmission errors can be observed in ASD, which is often accompanied by sensory symptoms including sound hyper- or hyposensitivity (Van der Molen et al., 2012; Knoth et al., 2014). The establishment of normal E/I ratios in auditory brainstem nuclei begins during embryonic and postnatal development, with additional refinement after hearing onset. Impairments in sound localization have been reported in patients with ASD and SZ (Matthews et al., 2007; Perrin et al., 2010; Visser et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2019), and studies of young and adult brains showed abnormalities in brainstem sizes (Hashimoto et al., 1992; Nopoulos et al., 2001; Claesdotter-Hybbinette et al., 2015). Epidemiological data have highlighted a potential for ASD susceptibility during a gestational period of brainstem development (reviewed in Dadalko and Travers, 2018). Studies using animal models of autism have shown alterations in the E/I ratio and signal strength in the sound localization pathway during postnatal development (Rotschafer et al., 2015; Ruby et al., 2015; Garcia-Pino et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2019). However, physiological differences of auditory brainstem development in sound processing disorders require further investigation. Notably, brainstem alterations in SZ and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are poorly understood. Here, we discuss factors required for normal development of the E/I ratio in the sound localization circuit and summarize signaling pathways that are altered in models of ASD.

Medial Nucleus of the Trapezoid Body: Development and Effects of Neurodevelopmental Disorders

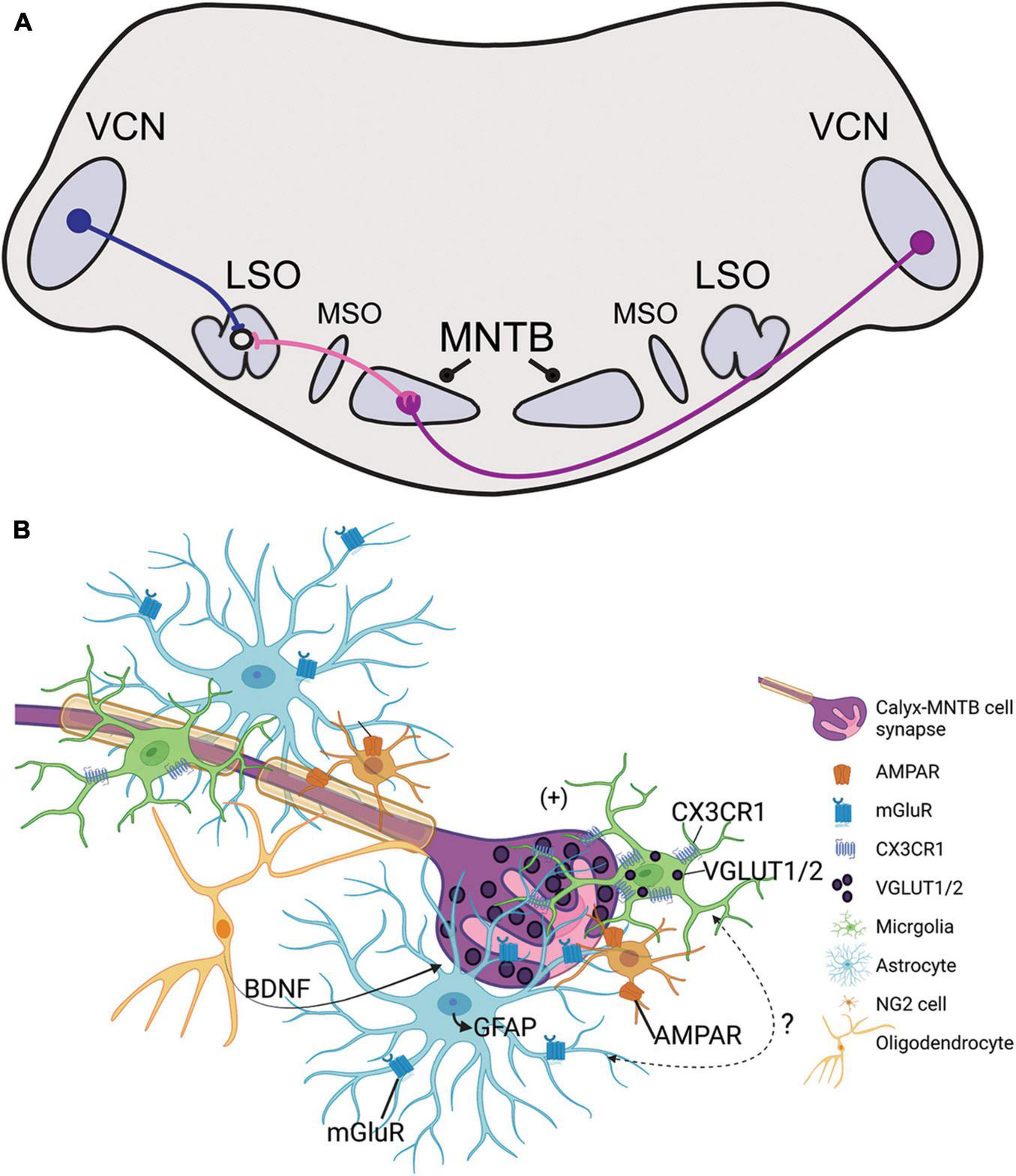

Auditory stimuli are detected by cochlear hair cells that transmit signals centrally through peripheral processes of spiral ganglion neurons (SGN). Central processes of SGNs bifurcate upon entering the brainstem to innervate the ventral and dorsal parts of the cochlear nucleus (CN) (Fekete et al., 1984). SGNs directly connect the hair cell in the periphery to its neuronal target in the CN, which then relays excitatory glutamatergic signals to auditory brainstem nuclei and higher auditory structures. Globular bushy cells (GBCs) receive endbulb inputs from SGNs and project to the contralateral medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) through a specialized central synapse, the calyx of Held (Figure 1A; Harrison and Irving, 1966; Spirou et al., 2005). MNTB neurons provide inhibitory glycinergic input to the lateral superior olive (LSO), medial superior olive (MSO), ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus, and superior periolivary nucleus (SPON) (Liu et al., 2014; Kulesza and Grothe, 2015; Kopp-Scheinpflug et al., 2018; Torres Cadenas et al., 2020). The MNTB is a main contributor of inhibition within the sound localization pathway through its termination onto MSO and LSO neurons and provides monaural temporal information via its connection to the SPON (Zarbin et al., 1981; Moore and Caspary, 1983; Kuwabara and Zook, 1992; Sommer et al., 1993; Behrend et al., 2002; Dehmel et al., 2002; Kulesza, 2007). LSO simultaneously receives excitatory projections from spherical bushy cells in the ipsilateral ventral cochlear nucleus (VCN) and inhibitory input from ipsilateral MNTB (Figure 1A). The balance of excitation and inhibition in LSO allows for computation of interaural level differences used in sound localization. Tonotopy is conserved across the central auditory pathway, which in turn allows the listener to localize sounds based on signal speed, intensity, and frequency within the brainstem and higher auditory regions.

FIGURE 1

(A) Illustration of the sound localization pathway in the auditory brainstem. Globular bushy cells (purple) cross the midline and terminate onto the contralateral medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) through the calyx of Held. MNTB neurons provide inhibitory input to cells in the medial superior olive (MSO) and lateral superior olive (LSO; projections shown in pink). LSO neurons simultaneously receive excitatory input from the ipsilateral ventral cochlear nucleus (VCN) via spherical bushy cells (blue). The excitatory/inhibitory ratio in the LSO is used in interaural level difference computation to facilitate sound source localization. (B) Schematic representation of glial signaling at the calyx of Held during development. The GBC axon is highly myelinated and terminates in the calyx of Held (purple), which is surrounded by microglia (green), astrocytes (light blue), NG2 cells (orange), and oligodendrocytes (yellow). Glutamatergic vesicles (dark purple) are released from the calyx and dominantly modulate the MNTB neuron (pink). Synapse development and strengthening depend on oligodendrocyte secretion of BDNF, and receptors such as NG2-AMPAR and astrocyte-mGluR which respond to calyceal glutamatergic release. Microglia contain VGLUT1/2 puncta and express CX3CR1, a receptor that modulates inhibitory pruning in the MNTB during circuit formation. Microglia elimination reduces GFAP expression in the MNTB but the signaling mechanism involving microglia-astrocyte communication has not been identified.

The precision of the sound localization pathway requires orchestrated maturation of cell number, synapse number and strength, and neurotransmitter phenotypes (Kotak et al., 1998; Nabekura et al., 2004; Gillespie et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2016). In the VCN, the endbulb of Held expands and develops elaborate branches (Cant and Morest, 1979; Ryugo and Sento, 1991; Nicol and Walmsley, 2002). The establishment of the mature calyx of Held in MNTB requires the elimination of multiple small inputs until exactly one calyx remains, strengthens, and forms a highly reticulated encapsulation of a principal cell soma by the onset of hearing at about P12 (Held, 1893; Kuwabara and Zook, 1991; Kuwabara et al., 1991; Hoffpauir et al., 2006; Holcomb et al., 2013). As calyces mature, MNTB neurons exhibit faster IPSC depression following hearing onset (Rajaram et al., 2020). MNTB-LSO connections also strengthen as they decrease in IPSC amplitude leading up to hearing onset while MNTB-MSO synapse amplitudes continue to decrease following hearing onset (Kim and Kandler, 2003; Magnusson et al., 2005; Walcher et al., 2011; Pilati et al., 2016; Rajaram et al., 2020). In the gerbil, MNTB-LSO synapse strengthening is largely completed by the third postnatal week, and studies using cochlear ablations suggest that synaptic pruning and topographic establishment during the postnatal period are activity-dependent (Sanes et al., 1992; Sanes and Takács, 1993; Kandler and Gillespie, 2005).

Factors Required for Proper MNTB Development

The MNTB forms by E17 (Morest, 1969; Kandler and Friauf, 1993; Hoffpauir et al., 2010), and proto-calyceal inputs can be seen before birth (Hoffpauir et al., 2010; Borst and Soria van Hoeve, 2012). Axon guidance molecules such as ephrin-B2, Netrin-1, DCC, and Robo3 guide GBC axons across the midline toward contralateral MNTB (Howell et al., 2007; Hsieh et al., 2010; Yu and Goodrich, 2014). Bone morphogenic protein (BMP)-receptor signaling early in development is required for correct GBC axonal targeting, pruning, and calyceal growth (Kolson et al., 2016b; Kronander et al., 2019). BMP signaling is altered in autism model organisms, and in humans, several signaling pathways associated with BMP are disrupted in ASD (Kumar et al., 2019). For instance, in the rodent, silencing Fmr1, a gene linked to fragile X syndrome, which is often correlated with autism, leads to an upregulation in BMP type II receptor and its signaling kinase (Kashima et al., 2016). In the brainstem, Fmr1 deletion leads to stunted SOC nuclei development, reduced pruning of inhibitory synapses in the MNTB and CN, and delays in auditory brainstem signal propagation (Rotschafer et al., 2015; Ruby et al., 2015; McCullagh et al., 2020). In the LSO, Fmr1 KO mice showed higher levels of excitatory input strength while inhibitory synapses were not affected (Garcia-Pino et al., 2017). Recent studies have noted hypoplasia in autistic brains, with significant reductions in SOC nuclei size, and cell volume and shape in the MNTB (Kulesza et al., 2011; Lukose et al., 2015). It is thus clear that within the MNTB there are anatomical and molecular abnormalities, impairments in synapse development and elimination, and functional deficits which result from genetic manipulation of an ASD-linked gene.

Synapse Organization and Strengthening

Proper synapse development in the MNTB requires spontaneous firing patterns, which aid in the establishment of topographic arrangements of cell structure and function along the MNTB mediolateral axis (Hoffpauir et al., 2006; Rodriguez-Contreras et al., 2008; Holcomb et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2013). In newborn prehearing rodents, spatially restricted and synchronous spontaneous activity in inner hair cells propagates along the developing auditory brainstem and refines the tonotopic maps (Friauf et al., 1999; Kandler et al., 2009; Sonntag et al., 2009; Tritsch et al., 2010; Crins et al., 2011; Leighton and Lohmann, 2016; Sun et al., 2018; Di Guilmi and Rodríguez-Contreras, 2021). Prior to P4, MNTB axons are abundant yet topographically imprecise (Sanes and Siverls, 1991). By P9, MNTB-LSO connections are refined, topographic precision is increased, and synapses are strengthened following activity-dependent pruning (Sanes and Friauf, 2000; Kim and Kandler, 2003; Müller et al., 2009, 2019; Hirtz et al., 2012; Clause et al., 2014). Genetic removal of the α9 subunit of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α9 KO) affects spontaneous firing patterns without altering overall activity levels and prohibits functional and structural sharpening of the inhibitory tonotopic map in the projection from MNTB to LSO (Clause et al., 2014), demonstrating that temporal patterns of spontaneous activity are important in development.

The mature MNTB contains a cell size gradient, which increases from the most medial (high frequency) to the most lateral (low frequency) regions (Weatherstone et al., 2017; Milinkeviciute et al., 2021a). Fmr1 KO mice have a delay in the establishment of the cell size gradient across the MNTB mediolateral axis (Rotschafer et al., 2015). Calyces also increase in size along the tonotopic axis (Milinkeviciute et al., 2021a). Membrane capacitance is correlated with larger synaptic input across the tonotopic axis and time constants are faster in the medial neurons compared to the lateral neurons (Weatherstone et al., 2017). These tonotopic variations reflect the optimization of MNTB cells for function at a wide range of frequencies.

Ion channels are tonotopically distributed in the MNTB, and this gradient can be disrupted with hearing impairment (von Hehn et al., 2004). Kv3.1 tonotopic distribution is lost in mice lacking Fmr1 (Strumbos et al., 2010). Congenital removal of Pak1, an autism-linked gene which normally regulates the development and maintenance of hair cell stereocilia, results in profound hearing loss and a reduction in synapse density in the cochleae, which may disable the establishment of topography (Cheng et al., 2021).

Inhibitory Synapse Distribution

Synaptic puncta are also distributed in a gradient across the MNTB mediolateral axis. Glycine transporter 2 (GLYT2) positive puncta can be detected in the MNTB prior to hearing onset and increase in expression across the mediolateral axis in the adult mouse (Friauf et al., 1999; Altieri et al., 2014; Milinkeviciute et al., 2021a). Loss of the microglial fractalkine receptor Cx3cr1, an ASD and SZ-linked gene (Ishizuka et al., 2017), disrupts the topographic distribution of GLYT2 in the MNTB, leads to a loss of MNTB neural size gradients and faster signal transmission, as measured by the auditory brainstem response (ABR) (Ishizuka et al., 2017; Milinkeviciute et al., 2021a). The MNTB in Fmr1 KO mice shows elevated levels of GABA/glycinergic marker vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) (Rotschafer et al., 2015; Ruby et al., 2015). Functionally Fmr1 KO mice have diminished peak amplitudes as measured by the ABR, and fewer all-or-none EPSCs in the MNTB (Rotschafer et al., 2015; Lu, 2019). Together, these studies show that autism-linked genes appear to influence distributions of ion channels and levels of inhibitory synapses, potentially altering balance in E/I neurotransmission.

Glial Mechanisms in Synaptic Pruning

Synaptic development, elimination, and maintenance are also mediated by glial cells. Post-mortem examinations of ASD or SZ brains have shown increased glial cell number and activation levels, and models of these neurodevelopmental disorders display altered glial pathology (Rodriguez and Kern, 2011; Laskaris et al., 2016). Glia contact and modulate synapses both during development and in the mature brain. Developmental fate-mapping studies show that glial cell expansion during development coincides with the formation of neural circuits in the auditory brainstem; SOC cell-type specific markers co-labeled with glial cell markers in the MNTB (Brandebura et al., 2018). At P0, glia, including microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, sparsely occupy lateral regions of the brainstem including the CN and over the first two postnatal weeks can be detected in more medial regions (Dinh et al., 2014; Saliu et al., 2014). In the MNTB, neuron-enriched genes decrease across the first two postnatal weeks, while glia-enriched genes increase within the same time frame (Kolson et al., 2016a). Glial cells interact with calyces and MNTB principal cells in an orchestrated manner both during development and adulthood (Dinh et al., 2014; Kolson et al., 2016a).

Astrocytes Contact and Modulate MNTB Synapses

Astrocytes contact pre- and postsynaptic membranes in MNTB (Elezgarai et al., 2001) and these contacts elicit slow inward currents through gliotransmisson in the mature MNTB (Reyes-Haro et al., 2010). Astrocytes lie in close apposition to the developing calyx of Held (Figure 1B; Dinh et al., 2014). In the MNTB astrocytes are coupled via gap junctions, and a single astrocyte can contact multiple MNTB principal cells and directly contact calyceal membranes in the active zones of the synapse (Müller et al., 2009; Reyes-Haro et al., 2010). Astrocytes express glutamate transporters and receptors, but calyceal activity does not trigger glutamate uptake currents in astrocytes (Bergles and Jahr, 1997; Renden et al., 2005; Reyes-Haro et al., 2010). The vellous processes of astrocytes contain metabotropic glutamate receptors in mice, reported at P6-18, which allows for uptake of excess glutamate from calyces and prevention of glutamate receptor saturation in the immature calyx (Figure 1B; Elezgarai et al., 2001; Sätzler et al., 2002; Renden et al., 2005; Uwechue et al., 2012).

Pharmacological ablation of microglia during development decreases expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a marker for mature astrocytes, in the MNTB (Milinkeviciute et al., 2019). When microglia return to control levels following the cessation of treatment, GFAP expression is restored to that of age-matched control mice (Milinkeviciute et al., 2021b). Deletion of Cx3cr1, expressed primarily on microglia, leads to an increase in GFAP expression in the MNTB (Figure 1B; Milinkeviciute et al., 2021a). Mice lacking Fmr1 have significantly more astrocytes in the VCN and LSO at P14, but there were no differences in the MNTB at this age, despite the abnormal cell numbers and sizes found in the MNTB at that age (Rotschafer et al., 2015). Studies of astrocytes in the auditory brainstem of SZ or ADHD are lacking, despite the evidence of reactive astrogliosis found in SZ or abnormal astrocytosis in ADHD models (Lim and Mah, 2015; Tarasov et al., 2020).

Oligodendrocytes Regulate Calyx Function

Non-calyceal spaces surrounding MNTB principal cells are filled with microglia, astrocytes, and/or oligodendrocytes (Figure 1B; Elezgarai et al., 2001; Reyes-Haro et al., 2010; Holcomb et al., 2013; Dinh et al., 2014). Firing patterns of GBCs can influence axon diameter and myelin thickness, suggesting that GBCs may regulate their own myelination (Sinclair et al., 2017). Neuron/glia antigen 2 (NG2)-glia, typically regarded as oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (Eugenín-von Bernhardi and Dimou, 2016), also interact with the calyx of Held and receive excitatory input from calyces through AMPA-receptor mediated “synapse-like” inputs (Figure 1B; Müller et al., 2009). NG2 cells are involved in fast signaling with synapses in the mature and developing CNS (Bergles et al., 2000). In the brainstem, oligodendrocytes release BDNF to modulate the glutamate vesicle pool at the nerve terminal, thereby mediating calyx strength and synaptic plasticity in an activity-dependent manner (Berret et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2019). BDNF has been detected at abnormal levels in ASD and SZ patients (Bryn et al., 2015; Gören, 2016; Saghazadeh and Rezaei, 2017; Peng et al., 2018). The development of oligodendrocytes and NG2 cells are dependent on postnatal microglia (Hagemeyer et al., 2017). Although auditory brainstem functions of BDNF in ASD or SZ models are unknown, this signaling pathway could be a regulatory mechanism for E/I balance at the level of the MNTB.

Microglia Regulate Synapse Elimination and Brainstem Function

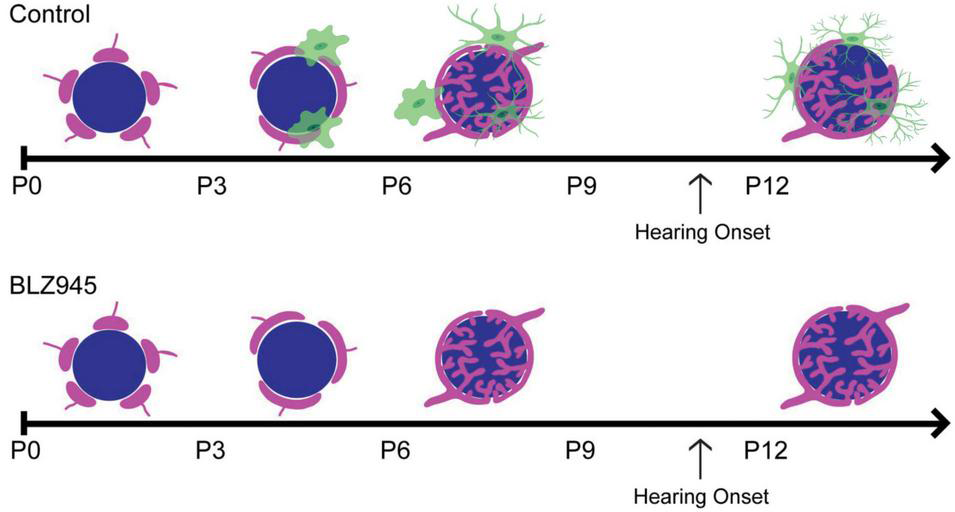

Microglia have increasingly become regarded as circuit sculptors in that they shape axonal projections, eliminate excess synapses, and strengthen intact connections (Paolicelli et al., 2011; Kettenmann et al., 2013). Post-mortem examinations of ASD brains showed higher microglial densities in the cerebral cortex (Tetreault et al., 2012) and abnormal microglial-neural spatial organization in the prefrontal cortex (Morgan et al., 2012). Further, inhibition of microglial activation is a potential therapeutic strategy for SZ, and microglial modulation may be a strategy to induce synaptic pruning in ASD (Monji et al., 2009; Andoh et al., 2019). Thus, it is interesting to identify the roles of microglia in auditory circuit development. Microglia can be sparsely detected in the VCN as early as P0, with expression patterns in the MNTB appearing by P6 (Dinh et al., 2014). Microglia in the early postnatal period first appear to have an amoeboid shape and later show a ramified morphology with more extended processes, indicating microglial maturation. In the mouse MNTB, microglial numbers peak by P14, an age after hearing onset. Microglia are in close apposition with the calyx of Held, with their processes interposed between calyces and MNTB principal cells, and peak in number at a time when excess synaptic contacts are pruned (Figure 2; Holcomb et al., 2013; Dinh et al., 2014). Loss of microglia during development impairs calyceal pruning after hearing onset (Figure 2; Milinkeviciute et al., 2019). VGLUT1/2 puncta were observed within microglia, possibly indicating that microglia engulf glutamatergic terminals during pruning. After cessation of the microglial-inhibiting drug BLZ945, microglia gradually returned from lateral to medial regions of the brainstem, recapitulating the pattern seen in normal development. The return of microglia was associated with recovery of auditory brainstem maturation and partial recovery of deficits in the auditory brainstem response (Dinh et al., 2014; Milinkeviciute et al., 2021b). Microglia may also influence the pruning of inhibitory synapses in the auditory system, as deletion of microglial Cx3cr1 was associated with impaired pruning of inhibitory synapses in MNTB (Milinkeviciute et al., 2021a).

FIGURE 2

(Top) Schematic representation of calyceal pruning during the first two postnatal weeks. Proto-calyces (magenta) innervate MNTB cells (blue) and are eliminated until a single dominant input remains. Microglia (green) are seen near calyces and display mature morphology after hearing onset. (Bottom) Microglia elimination with BLZ945 impairs calyceal pruning and leads to higher levels of polyinnervated MNTB neurons. Adapted from Milinkeviciute et al. (2019).

In animals deafened after the first postnatal week, microglia in VCN have more active morphology compared to the control group, which showed more ramified processes (Noda et al., 2019). In mice with cochlear removals activated microglia in the VCN were in close apposition to glutamatergic but not GABAergic synapses (Janz and Illing, 2014). Further, deafening led to an upregulation of phagocytic and anti-inflammatory markers in the VCN (Noda et al., 2019). From these studies, it appears that microglia regulate the elimination of synapses during auditory circuit development. Whether similar findings would be detected in a model of sensory processing disorders is not known. A potential clue is that mice that lack certain autism-linked genes, such as Fmr1 and Cx3cr1, show impaired pruning and that ASD and SZ are linked with abnormal microglia.

Concluding Remarks

In this review, we discussed factors that are required for normal MNTB development as well as ASD-related models that impair auditory development. The establishment of the MNTB requires factors that regulate axon guidance, development of synapses as well as topographic gradients, synapse elimination, and synapse strengthening. In models of ASD, loss of Fmr1, Pak1, or Cx3cr1 results in structural and functional alterations of synapses and an altered glial cell profile. These factors may similarly alter synaptic balance in SZ, ADHD, or other neurodevelopmental disorders.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Author contributions

SC, GM, and KC wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH NIDCD DC010796 and NIH T32 DC010775.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Altieri S. C. Zhao T. Jalabi W. Maricich S. M. (2014). Development of glycinergic innervation to the murine LSO and SPN in the presence and absence of the MNTB.Front. Neural. Circuits8:109. 10.3389/fncir.2014.00109

2

Andoh M. Ikegaya Y. Koyama R. (2019). Microglia as possible therapeutic targets for autism spectrum disorders.Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci.167223–245. 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2019.06.012

3

Behrend O. Brand A. Kapfer C. Grothe B. (2002). Auditory response properties in the superior paraolivary nucleus of the gerbil.J. Neurophysiol.872915–2928. 10.1152/jn.2002.87.6.2915

4

Bergles D. E. Jahr C. E. (1997). Synaptic activation of glutamate transporters in hippocampal astrocytes.Neuron191297–1308. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80420-1

5

Bergles D. E. Roberts J. D. Somogyi P. Jahr C. E. (2000). Glutamatergic synapses on oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the hippocampus.Nature405187–191. 10.1038/35012083

6

Berret E. Barron T. Xu J. Debner E. Kim E. J. Kim J. H. (2017). Oligodendroglial excitability mediated by glutamatergic inputs and Nav1.2 activation.Nat. Commun.8:557. 10.1038/s41467-017-00688-0

7

Borst J. G. Soria van Hoeve J. (2012). The calyx of Held synapse: from model synapse to auditory relay.Annu. Rev. Physiol.74199–224. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153236

8

Brandebura A. N. Morehead M. Heller D. T. Holcomb P. Kolson D. R. Jones G. et al (2018). Glial Cell Expansion Coincides with Neural Circuit Formation in the Developing Auditory Brainstem.Dev. Neurobiol.781097–1116. 10.1002/dneu.22633

9

Bryn V. Halvorsen B. Ueland T. Isaksen J. Kolkova K. Ravn K. et al (2015). Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in childhood.Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol.19411–414. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.03.005

10

Cant N. B. Morest D. K. (1979). The bushy cells in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of the cat.Neuroscience41925–1945. 10.1016/0306-4522(79)90066-6

11

Cheng C. Hou Y. Zhang Z. Wang Y. Lu L. Zhang L. et al (2021). Disruption of the autism-related gene Pak1 causes stereocilia disorganization, hair cell loss, and deafness in mice.J. Genet. Genom.48324–332. 10.1016/j.jgg.2021.03.010

12

Claesdotter-Hybbinette E. Safdarzadeh-Haghighi M. Råstam M. Lindvall M. (2015). Abnormal brainstem auditory response in young females with ADHD.Psychiatry Res.229750–754. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.08.007

13

Clause A. Kim G. Sonntag M. Weisz C. J. Vetter D. E. Rûbsamen R. et al (2014). The precise temporal pattern of prehearing spontaneous activity is necessary for tonotopic map refinement.Neuron82822–835. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.001

14

Crins T. T. Rusu S. I. Rodríguez-Contreras A. Borst J. G. (2011). Developmental changes in short-term plasticity at the rat calyx of Held synapse.J. Neurosci.3111706–11717. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1995-11.2011

15

Dadalko O. I. Travers B. G. (2018). Evidence for Brainstem Contributions to Autism Spectrum Disorders.Front. Integr. Neurosci.12:47. 10.3389/fnint.2018.00047

16

Dehmel S. Kopp-Scheinpflug C. Dörrscheidt G. J. Rübsamen R. (2002). Electrophysiological characterization of the superior paraolivary nucleus in the Mongolian gerbil.Hear Res.17218–36. 10.1016/S0378-5955(02)00353-2

17

Di Guilmi M. N. Rodríguez-Contreras A. (2021). Characterization of Developmental Changes in Spontaneous Electrical Activity of Medial Superior Olivary Neurons Before Hearing Onset With a Combination of Injectable and Volatile Anesthesia.Front. Neurosci.15:654479. 10.3389/fnins.2021.654479

18

Dinh M. L. Koppel S. J. Korn M. J. Cramer K. S. (2014). Distribution of glial cells in the auditory brainstem: normal development and effects of unilateral lesion.Neuroscience278237–252. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.08.016

19

Elezgarai I. Bilbao A. Mateos J. M. Azkue J. J. Benítez R. Osorio A. et al (2001). Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors are differentially expressed in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body in the developing and adult rat.Neuroscience104487–498. 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00080-X

20

Eugenín-von Bernhardi J. Dimou L. (2016). NG2-glia.Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.94927–45. 10.1007/978-3-319-40764-7_2

21

Fekete D. M. Rouiller E. M. Liberman M. C. Ryugo D. K. (1984). The central projections of intracellularly labeled auditory nerve fibers in cats. J. Comp. Neurol.229, 432–450. 10.1002/cne.902290311

22

Friauf E. Aragón C. Löhrke S. Westenfelder B. Zafra F. (1999). Developmental expression of the glycine transporter GLYT2 in the auditory system of rats suggests involvement in synapse maturation.J. Comp. Neurol.41217–37. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19990913)412:1<17::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-E

23

Garcia-Pino E. Gessele N. Koch U. (2017). Enhanced Excitatory Connectivity and Disturbed Sound Processing in the Auditory Brainstem of Fragile X Mice.J. Neurosci.377403–7419. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2310-16.2017

24

Gillespie D. C. Kim G. Kandler K. (2005). Inhibitory synapses in the developing auditory system are glutamatergic.Nat. Neurosci.8332–338. 10.1038/nn1397

25

Gören J. L. (2016). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and schizophrenia.Ment. Health Clin.6285–288. 10.9740/mhc.2016.11.285

26

Hagemeyer N. Hanft K. M. Akriditou M. A. Unger N. Park E. S. Stanley E. R. et al (2017). Microglia contribute to normal myelinogenesis and to oligodendrocyte progenitor maintenance during adulthood.Acta. Neuropathol.134441–458. 10.1007/s00401-017-1747-1

27

Harrison J. M. Irving R. (1966). Ascending connections of the anterior ventral cochlear nucleus in the rat.J. Comp. Neurol.12651–63. 10.1002/cne.901260105

28

Hashimoto T. Tayama M. Miyazaki M. Sakurama N. Yoshimoto T. Murakawa K. et al (1992). Reduced brainstem size in children with autism.Brain Dev.1494–97. 10.1016/S0387-7604(12)80093-3

29

Held H. (1893). Die zentrale Gehörleitung.Arch. Anat. Physiol. Anat. Abtheil.17201–248.

30

Hirtz J. J. Braun N. Griesemer D. Hannes C. Janz K. Löhrke S. et al (2012). Synaptic refinement of an inhibitory topographic map in the auditory brainstem requires functional Cav1.3 calcium channels.J. Neurosci.3214602–14616. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0765-12.2012

31

Hoffpauir B. K. Grimes J. L. Mathers P. H. Spirou G. A. (2006). Synaptogenesis of the calyx of Held: rapid onset of function and one-to-one morphological innervation.J. Neurosci.265511–5523. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5525-05.2006

32

Hoffpauir B. K. Kolson D. R. Mathers P. H. Spirou G. A. (2010). Maturation of synaptic partners: functional phenotype and synaptic organization tuned in synchrony.J. Physiol.5884365–4385. 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.198564

33

Holcomb P. S. Hoffpauir B. K. Hoyson M. C. Jackson D. R. Deerinck T. J. Marrs G. S. et al (2013). Synaptic inputs compete during rapid formation of the calyx of Held: a new model system for neural development.J. Neurosci.3312954–12969. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1087-13.2013

34

Howell D. M. Morgan W. J. Jarjour A. A. Spirou G. A. Berrebi A. S. Kennedy T. E. et al (2007). Molecular guidance cues necessary for axon pathfinding from the ventral cochlear nucleus.J. Comp. Neurol.504533–549. 10.1002/cne.21443

35

Hsieh C. Y. Nakamura P. A. Luk S. O. Miko I. J. Henkemeyer M. Cramer K. S. (2010). Ephrin-B Reverse Signaling Is Required for Formation of Strictly Contralateral Auditory Brainstem Pathways.J. Neurosci.309840–9849. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0386-10.2010

36

Ishizuka K. Fujita Y. Kawabata T. Kimura H. Iwayama Y. Inada T. et al (2017). Rare genetic variants in CX3CR1 and their contribution to the increased risk of schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders.Trans. Psychiatry7e1184–e1184. 10.1038/tp.2017.173

37

Jang M. Gould E. Xu J. Kim E. J. Kim J. H. (2019). Oligodendrocytes regulate presynaptic properties and neurotransmission through BDNF signaling in the mouse brainstem.Elife8:e42156. 10.7554/eLife.42156

38

Janz P. Illing R.-B. (2014). A role for microglial cells in reshaping neuronal circuitry of the adult rat auditory brainstem after its sensory deafferentation.J. Neurosci. Res.92432–445. 10.1002/jnr.23334

39

Kandler K. Clause A. Noh J. (2009). Tonotopic reorganization of developing auditory brainstem circuits.Nat. Neurosci.12711–717. 10.1038/nn.2332

40

Kandler K. Friauf E. (1993). Pre- and postnatal development of efferent connections of the cochlear nucleus in the rat.J. Comp. Neurol.328161–184. 10.1002/cne.903280202

41

Kandler K. Gillespie D. C. (2005). Developmental refinement of inhibitory sound-localization circuits.Trends Neurosci.28290–296. 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.007

42

Kashima R. Roy S. Ascano M. Martinez-Cerdeno V. Ariza-Torres J. Kim S. et al (2016). Augmented noncanonical BMP type II receptor signaling mediates the synaptic abnormality of fragile X syndrome.Sci. Signal.9:ra58. 10.1126/scisignal.aaf6060

43

Kettenmann H. Kirchhoff F. Verkhratsky A. (2013). Microglia: new roles for the synaptic stripper.Neuron7710–18. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.023

44

Kim G. Kandler K. (2003). Elimination and strengthening of glycinergic/GABAergic connections during tonotopic map formation.Nat. Neurosci.6282–290. 10.1038/nn1015

45

Knoth I. S. Vannasing P. Major P. Michaud J. L. Lippé S. (2014). Alterations of visual and auditory evoked potentials in fragile X syndrome.Inter. J. Dev. Neurosci.3690–97. 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2014.05.003

46

Kolson D. R. Wan J. Wu J. Dehoff M. Brandebura A. N. Qian J. et al (2016a). Temporal patterns of gene expression during calyx of held development.Dev. Neurobiol.76166–189.

47

Kolson D. R. Wan J. Wu J. Dehoff M. Brandebura A. N. Qian J. et al (2016b). Temporal patterns of gene expression during calyx of held development.Dev. Neurobiol.76166–189. 10.1002/dneu.22306

48

Kopp-Scheinpflug C. Sinclair J. L. Linden J. F. (2018). When Sound Stops:offset Responses in the Auditory System.Trends Neurosci.41712–728. 10.1016/j.tins.2018.08.009

49

Kotak V. C. Korada S. Schwartz I. R. Sanes D. H. (1998). A developmental shift from GABAergic to glycinergic transmission in the central auditory system.J. Neurosci.184646–4655. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04646.1998

50

Kronander E. Clark C. Schneggenburger R. (2019). Role of BMP Signaling for the Formation of Auditory Brainstem Nuclei and Large Auditory Relay Synapses.Dev. Neurobiol.79155–174. 10.1002/dneu.22661

51

Kulesza R. J. Jr. (2007). Cytoarchitecture of the human superior olivary complex: medial and lateral superior olive.Hear Res.22580–90. 10.1016/j.heares.2006.12.006

52

Kulesza R. J. Jr. Grothe B. (2015). Yes, there is a medial nucleus of the trapezoid body in humans.Front. Neuroanat.9:35. 10.3389/fnana.2015.00035

53

Kulesza R. J. Jr. Lukose R. Stevens L. V. (2011). Malformation of the human superior olive in autistic spectrum disorders.Brain Res.1367360–371. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.015

54

Kumar S. Reynolds K. Ji Y. Gu R. Rai S. Zhou C. J. (2019). Impaired neurodevelopmental pathways in autism spectrum disorder: a review of signaling mechanisms and crosstalk.J. Neurodevelop. Disord.11:10. 10.1186/s11689-019-9268-y

55

Kuwabara N. DiCaprio R. A. Zook J. M. (1991). Afferents to the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body and their collateral projections.J. Comp. Neurol.314684–706. 10.1002/cne.903140405

56

Kuwabara N. Zook J. M. (1991). Classification of the principal cells of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body.J. Comp. Neurol.314707–720. 10.1002/cne.903140406

57

Kuwabara N. Zook J. M. (1992). Projections to the medial superior olive from the medial and lateral nuclei of the trapezoid body in rodents and bats.J. Comp. Neurol.324522–538. 10.1002/cne.903240406

58

Laskaris L. E. Di Biase M. A. Everall I. Chana G. Christopoulos A. Skafidas E. et al (2016). Microglial activation and progressive brain changes in schizophrenia.Br. J. Pharmacol.173666–680. 10.1111/bph.13364

59

Lee H. Bach E. Noh J. Delpire E. Kandler K. (2016). Hyperpolarization-independent maturation and refinement of GABA/glycinergic connections in the auditory brain stem.J. Neurophysiol.1151170–1182. 10.1152/jn.00926.2015

60

Leighton A. H. Lohmann C. (2016). The Wiring of Developing Sensory Circuits-From Patterned Spontaneous Activity to Synaptic Plasticity Mechanisms.Front. Neural. Circuits10:71. 10.3389/fncir.2016.00071

61

Lim S.-Y. Mah W. (2015). Abnormal Astrocytosis in the Basal Ganglia Pathway of Git1(-/-) Mice.Mol. Cells38540–547. 10.14348/molcells.2015.0041

62

Liu H. H. Huang C. F. Wang X. (2014). Acoustic signal characteristic detection by neurons in ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus in mice.Dongwuxue Yanjiu35500–509.

63

Lu Y. (2019). Subtle differences in synaptic transmission in medial nucleus of trapezoid body neurons between wild-type and Fmr1 knockout mice.Brain Res.171795–103. 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.04.006

64

Lukose R. Beebe K. Kulesza R. J. Jr. (2015). Organization of the human superior olivary complex in 15q duplication syndromes and autism spectrum disorders.Neuroscience286216–230. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.11.033

65

Magnusson A. K. Kapfer C. Grothe B. Koch U. (2005). Maturation of glycinergic inhibition in the gerbil medial superior olive after hearing onset.J. Physiol.568497–512. 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.094763

66

Matthews N. Todd J. Budd T. W. Cooper G. Michie P. T. (2007). Auditory lateralization in schizophrenia–mismatch negativity and behavioral evidence of a selective impairment in encoding interaural time cues.Clin. Neurophysiol.118833–844. 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.11.017

67

McCullagh E. A. Rotschafer S. E. Auerbach B. D. Klug A. Kaczmarek L. K. Cramer K. S. et al (2020). Mechanisms underlying auditory processing deficits in Fragile X syndrome.Faseb J.343501–3518. 10.1096/fj.201902435R

68

Milinkeviciute G. Chokr S. M. Castro E. M. Cramer K. S. (2021a). CX3CR1 mutation alters synaptic and astrocytic protein expression, topographic gradients, and response latencies in the auditory brainstem.J. Comp. Neurol.5293076–3097. 10.1002/cne.25150

69

Milinkeviciute G. Chokr S. M. Cramer K. S. (2021b). Auditory Brainstem Deficits from Early Treatment with a CSF1R Inhibitor Largely Recover with Microglial Repopulation.eNeuro8ENEURO.318–ENEURO.320. 10.1523/ENEURO.0318-20.2021

70

Milinkeviciute G. Henningfield C. M. Muniak M. A. Chokr S. M. Green K. N. Cramer K. S. (2019). Microglia Regulate Pruning of Specialized Synapses in the Auditory Brainstem.Front. Neural. Circuits13:55. 10.3389/fncir.2019.00055

71

Monji A. Kato T. Kanba S. (2009). Cytokines and schizophrenia:microglia hypothesis of schizophrenia.Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci.63257–265. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01945.x

72

Moore M. J. Caspary D. M. (1983). Strychnine blocks binaural inhibition in lateral superior olivary neurons.J. Neurosci.3237–242. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-01-00237.1983

73

Morest D. K. (1969). The differentiation of cerebral dendrites:a study of the post-migratory neuroblast in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body.Z Anat. Entwicklungsgesch128271–289. 10.1007/BF00522528

74

Morgan J. T. Chana G. Abramson I. Semendeferi K. Courchesne E. Everall I. P. (2012). Abnormal microglial-neuronal spatial organization in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in autism.Brain Res.145672–81. 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.03.036

75

Müller J. Reyes-Haro D. Pivneva T. Nolte C. Schaette R. Lübke J. et al (2009). The principal neurons of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body and NG2(+) glial cells receive coordinated excitatory synaptic input.J. Gen. Physiol.134115–127. 10.1085/jgp.200910194

76

Müller N. I. C. Sonntag M. Maraslioglu A. Hirtz J. J. Friauf E. (2019). Topographic map refinement and synaptic strengthening of a sound localization circuit require spontaneous peripheral activity.J. Physiol.5975469–5493. 10.1113/JP277757

77

Nabekura J. Katsurabayashi S. Kakazu Y. Shibata S. Matsubara A. Jinno S. et al (2004). Developmental switch from GABA to glycine release in single central synaptic terminals.Nat. Neurosci.717–23. 10.1038/nn1170

78

Nicol M. J. Walmsley B. (2002). Ultrastructural basis of synaptic transmission between endbulbs of Held and bushy cells in the rat cochlear nucleus.J. Physiol.539713–723. 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012972

79

Noda M. Hatano M. Hattori T. Takarada-Iemata M. Shinozaki T. Sugimoto H. et al (2019). Microglial activation in the cochlear nucleus after early hearing loss in rats.Auris Nasus Larynx46716–723. 10.1016/j.anl.2019.02.006

80

Nopoulos P. C. Ceilley J. W. Gailis E. A. Andreasen N. C. (2001). An MRI study of midbrain morphology in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to psychosis, neuroleptics, and cerebellar neural circuitry.Biol. Psychiatry4913–19. 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01059-3

81

Paolicelli R. C. Bolasco G. Pagani F. Maggi L. Scianni M. Panzanelli P. et al (2011). Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development.Science3331456–1458. 10.1126/science.1202529

82

Peng S. Li W. Lv L. Zhang Z. Zhan X. (2018). BDNF as a biomarker in diagnosis and evaluation of treatment for schizophrenia and depression.Discov. Med.26127–136.

83

Perrin M. A. Butler P. D. DiCostanzo J. Forchelli G. Silipo G. Javitt D. C. (2010). Spatial localization deficits and auditory cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia.Schizophr Res.124161–168. 10.1016/j.schres.2010.06.004

84

Pilati N. Linley D. M. Selvaskandan H. Uchitel O. Hennig M. H. Kopp-Scheinpflug C. et al (2016). Acoustic trauma slows AMPA receptor-mediated EPSCs in the auditory brainstem, reducing GluA4 subunit expression as a mechanism to rescue binaural function.J. Physiol.5943683–3703. 10.1113/JP271929

85

Rajaram E. Pagella S. Grothe B. Kopp-Scheinpflug C. (2020). Physiological and anatomical development of glycinergic inhibition in the mouse superior paraolivary nucleus following hearing onset.J. Neurophysiol.124471–483. 10.1152/jn.00053.2020

86

Renden R. Taschenberger H. Puente N. Rusakov D. A. Duvoisin R. Wang L. Y. et al (2005). Glutamate transporter studies reveal the pruning of metabotropic glutamate receptors and absence of AMPA receptor desensitization at mature calyx of Held synapses.J. Neurosci.258482–8497. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1848-05.2005

87

Reyes-Haro D. Müller J. Boresch M. Pivneva T. Benedetti B. Scheller A. et al (2010). Neuron-astrocyte interactions in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body.J. Gen. Physiol.135583–594. 10.1085/jgp.200910354

88

Rodriguez-Contreras A. van Hoeve J. S. Habets R. L. Locher H. Borst J. G. (2008). Dynamic development of the calyx of Held synapse.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.1055603–5608. 10.1073/pnas.0801395105

89

Rodriguez J. I. Kern J. K. (2011). Evidence of microglial activation in autism and its possible role in brain underconnectivity.Neuron Glia. Biol.7205–213. 10.1017/S1740925X12000142

90

Rotschafer S. E. Marshak S. Cramer K. S. (2015). Deletion of Fmr1 alters function and synaptic inputs in the auditory brainstem.PLoS One10:e0117266. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117266

91

Ruby K. Falvey K. Kulesza R. J. (2015). Abnormal neuronal morphology and neurochemistry in the auditory brainstem of Fmr1 knockout rats.Neuroscience303285–298. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.061

92

Ryugo D. K. Sento S. (1991). Synaptic connections of the auditory nerve in cats: relationship between endbulbs of held and spherical bushy cells.J. Comp. Neurol.30535–48. 10.1002/cne.903050105

93

Saghazadeh A. Rezaei N. (2017). Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Levels in Autism:a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.J. Autism Dev. Disord.471018–1029. 10.1007/s10803-016-3024-x

94

Saliu A. Adise S. Xian S. Kudelska K. Rodríguez-Contreras A. (2014). Natural and lesion-induced decrease in cell proliferation in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body during hearing development.J. Comp. Neurol.522971–985. 10.1002/cne.23473

95

Sanes D. H. Friauf E. (2000). Development and influence of inhibition in the lateral superior olivary nucleus.Hear Res.14746–58. 10.1016/S0378-5955(00)00119-2

96

Sanes D. H. Markowitz S. Bernstein J. Wardlow J. (1992). The influence of inhibitory afferents on the development of postsynaptic dendritic arbors.J. Comp. Neurol.321637–644. 10.1002/cne.903210410

97

Sanes D. H. Siverls V. (1991). Development and specificity of inhibitory terminal arborizations in the central nervous system.J. Neurobiol.22837–854. 10.1002/neu.480220805

98

Sanes D. H. Takács C. (1993). Activity-dependent refinement of inhibitory connections.Eur. J. Neurosci.5570–574. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00522.x

99

Sätzler K. Söhl L. F. Bollmann J. H. Borst J. G. G. Frotscher M. Sakmann B. et al (2002). Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of a Calyx of Held and Its Postsynaptic Principal Neuron in the Medial Nucleus of the Trapezoid Body.J. Neurosci.2210567–10579. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10567.2002

100

Sinclair J. L. Fischl M. J. Alexandrova O. Heβ M. Grothe B. Leibold C. et al (2017). Sound-Evoked Activity Influences Myelination of Brainstem Axons in the Trapezoid Body.J. Neurosci.378239–8255. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3728-16.2017

101

Smith A. Storti S. Lukose R. Kulesza R. J. Jr. (2019). Structural and Functional Aberrations of the Auditory Brainstem in Autism Spectrum Disorder.J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc.11941–50. 10.7556/jaoa.2019.007

102

Sommer I. Lingenhöhl K. Friauf E. (1993). Principal cells of the rat medial nucleus of the trapezoid body: an intracellular in vivo study of their physiology and morphology.Exp. Brain Res.95223–239. 10.1007/BF00229781

103

Sonntag M. Englitz B. Kopp-Scheinpflug C. Rübsamen R. (2009). Early postnatal development of spontaneous and acoustically evoked discharge activity of principal cells of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body: an in vivo study in mice.J. Neurosci.299510–9520. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1377-09.2009

104

Spirou G. A. Rager J. Manis P. B. (2005). Convergence of auditory-nerve fiber projections onto globular bushy cells.Neuroscience136843–863. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.068

105

Strumbos J. G. Brown M. R. Kronengold J. Polley D. B. Kaczmarek L. K. (2010). Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein Is Required for Rapid Experience-Dependent Regulation of the Potassium Channel Kv3.1b.J. Neurosci.3010263–10271. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1125-10.2010

106

Sun S. Babola T. Pregernig G. So K. S. Nguyen M. Su S. M. et al (2018). Hair Cell Mechanotransduction Regulates Spontaneous Activity and Spiral Ganglion Subtype Specification in the Auditory System.Cell1741247–1263. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.008

107

Tarasov V. V. Svistunov A. A. Chubarev V. N. Sologova S. S. Mukhortova P. Levushkin D. et al (2020). Alterations of Astrocytes in the Context of Schizophrenic Dementia.Front. Pharmacol.10:1612. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01612

108

Tetreault N. A. Hakeem A. Y. Jiang S. Williams B. A. Allman E. Wold B. J. et al (2012). Microglia in the cerebral cortex in autism.J. Autism Dev. Disord.422569–2584. 10.1007/s10803-012-1513-0

109

Torres Cadenas L. Fischl M. J. Weisz C. J. C. (2020). Synaptic Inhibition of Medial Olivocochlear Efferent Neurons by Neurons of the Medial Nucleus of the Trapezoid Body.J. Neurosci.40509–525. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1288-19.2019

110

Tritsch N. X. Rodriguez-Contreras A. Crins T. T. Wang H. C. Borst J. G. Bergles D. E. (2010). Calcium action potentials in hair cells pattern auditory neuron activity before hearing onset.Nat. Neurosci.131050–1052. 10.1038/nn.2604

111

Uwechue N. M. Marx M.-C. Chevy Q. Billups B. (2012). Activation of glutamate transport evokes rapid glutamine release from perisynaptic astrocytes.J. Physiol.5902317–2331. 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.226605

112

Van der Molen M. J. W. Van der Molen M. W. Ridderinkhof K. R. Hamel B. C. J. Curfs L. M. G. Ramakers G. J. A. (2012). Auditory and visual cortical activity during selective attention in fragile X syndrome: A cascade of processing deficiencies.Clin. Neurophysiol.123720–729. 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.08.023

113

Visser E. Zwiers M. P. Kan C. C. Hoekstra L. van Opstal A. J. Buitelaar J. K. (2013). Atypical vertical sound localization and sound-onset sensitivity in people with autism spectrum disorders.J. Psychiatry Neurosci.38398–406. 10.1503/jpn.120177

114

von Hehn C. A. Bhattacharjee A. Kaczmarek L. K. (2004). Loss of Kv3.1 tonotopicity and alterations in cAMP response element-binding protein signaling in central auditory neurons of hearing impaired mice.J. Neurosci.241936–1940. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4554-03.2004

115

Walcher J. Hassfurth B. Grothe B. Koch U. (2011). Comparative posthearing development of inhibitory inputs to the lateral superior olive in gerbils and mice.J. Neurophysiol.1061443–1453. 10.1152/jn.01087.2010

116

Weatherstone J. H. Kopp-Scheinpflug C. Pilati N. Wang Y. Forsythe I. D. Rubel E. W. et al (2017). Maintenance of neuronal size gradient in MNTB requires sound-evoked activity.J. Neurophysiol.117756–766. 10.1152/jn.00528.2016

117

Xiao L. Michalski N. Kronander E. Gjoni E. Genoud C. Knott G. et al (2013). BMP signaling specifies the development of a large and fast CNS synapse.Nat. Neurosci.16856–864.

118

Yu W. M. Goodrich L. V. (2014). Morphological and physiological development of auditory synapses.Hear Res.3113–16.

119

Zarbin M. A. Wamsley J. K. Kuhar M. J. (1981). Glycine receptor: light microscopic autoradiographic localization with [3H]strychnine.J. Neurosci.1532–547.

Summary

Keywords

cochlear nucleus, medial nucleus of the trapezoid body, tonotopy, synaptic pruning, calyx of Held

Citation

Chokr SM, Milinkeviciute G and Cramer KS (2022) Synapse Maturation and Developmental Impairment in the Medial Nucleus of the Trapezoid Body. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 16:804221. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2022.804221

Received

29 October 2021

Accepted

17 January 2022

Published

09 February 2022

Volume

16 - 2022

Edited by

Patricia Gaspar, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), France

Reviewed by

Maria Eulalia Rubio, University of Pittsburgh, United States; Jean Livet, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), France

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Chokr, Milinkeviciute and Cramer.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karina S. Cramer, cramerk@uci.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.