- 1Department of Midwifery, College of Medical Health Science, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia

- 2Department of Midwifery, Mekidela Amba Primary Hospital, Mekidela, Ethiopia

- 3Department of Midwifery, Mida Weremo Primary Hospital, Meragna, Ethiopia

- 4Department of Midwifery, Dessie Health Science College, Dessie, Ethiopia

- 5Department of Midwifery, Sayint Primary Hospital, Sayint, Ethiopia

- 6Department of Midwifery, Shebel Berenta Health Office, Shebel Berenta, Ethiopia

Introduction: Antenatal care refers to the medical attention provided by skilled healthcare professionals to pregnant women to ensure optimal health outcomes for both the mother and fetus throughout pregnancy. In Ethiopia, there is limited evidence regarding the completion of eight antenatal care contacts and the factors associated with it. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and associated factors of completing eight antenatal care contacts among mothers in Shebel Berenta Woreda.

Method: A community-based cross-sectional study was employed. A stratified sampling technique was employed to select the sample. Data were exported from Kobo Toolbox software to SPSS version 27 for analysis. Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to assess associations between the outcome and independent variables, with statistical significance determined at a p-value of <0.05.

Result: This study showed that the prevalence of eight or more antenatal care contacts was 9.6% [95% confidence interval (CI): 7.4–12.3]. In this study, good knowledge of ANC [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.402; 95% CI: 1.115–5.175], media exposure (AOR = 2.47; 95% CI: 1.15–5.306), time of early initiation for first ANC contact (AOR = 5.46; 95% CI: 2.837–10.51), women's governmental occupation (AOR = 3.745; 95% CI: 1.364–10.28), two to four pregnancies (AOR = 3.524; 95% CI: 1.696–7.32), and family size less than five (AOR = 3.005; 95% CI: 1.461–6.179) were significantly associated with the outcome variable.

Conclusion: The study indicates that the prevalence of eight or more antenatal care contacts was low. Time of initiation for first ANC contact, women's occupational status, knowledge of antenatal care, family size, number of pregnancies, and media exposure were significantly associated with the outcome variable.

Introduction

Antenatal care (ANC) is a broad term to describe the medical attention provided by skilled healthcare professionals for pregnant women to ensure optimal health conditions for both the mother and fetus throughout pregnancy (1). Antenatal care is a vital service for reducing pregnancy complications and improving child health outcomes (2, 3).

Antenatal care is essential to maintain the health of women and their unborn children. Women can learn healthy behaviors during pregnancy and better recognize danger signs during pregnancy and childbirth. Through antenatal care, pregnant women can also access micronutrient supplementation, such as iron-folic acid, treatment for hypertension to prevent eclampsia, immunization against tetanus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing, and in areas where malaria is endemic, medications and insecticide-treated mosquito nets (2, 4–6). ANC facilitates and increases opportunities for the uptake of preventive measures, the timely detection of danger signs, a reduction in complications, and addressing healthcare inequalities (7).

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends at least eight ANC contacts during pregnancy, replacing the previous focused antenatal care model. These include one contact in the first trimester (up to 12 weeks), two in the second trimester (at 20 and 26 weeks), and five contacts in the third trimester (at 30, 34, 36, 38, and 40 weeks) to improve perinatal outcomes and enhance women's experience of care (8).

Globally, maternal mortality is alarmingly high. In 2020, 287,000 women died during and after pregnancy and childbirth. These deaths predominantly occurred in low- and lower-middle-income countries, accounting for approximately 95% of all maternal fatalities. Tragically, the majority of these deaths could have been prevented. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) alone accounted for 70% of global maternal deaths. Ethiopia also contributed significantly in 2020, with 3.6% of global maternal deaths (9). ANC remains a prominent measure for improving maternal health outcomes (10).

Ethiopia acknowledges the importance of antenatal care in improving maternal and neonatal health outcomes. However, the benefits of ANC are only realized when expectant mothers use these services as recommended. In many underdeveloped countries, the prevalence of ANC service utilization remains low. Regular prenatal visits are essential for the early identification and management of maternal complications and risk factors (11).

A higher frequency of ANC contacts with healthcare providers can reduce maternal mortality by up to 20% during pregnancy, labor, delivery, and the postnatal period. It also plays a vital role in reducing the incidence of stillbirth, neonatal and infant mortality, stunting, and underweight (4, 7, 12–14). High-quality ANC follow-up can lower stillbirth rates by almost half—both directly through preventative care and indirectly by encouraging deliveries in health facilities where complications can be effectively managed (4). Receiving a minimum of eight ANC contacts before delivery has been shown to reduce the risk of preterm birth and low birth weight by 72% and 64%, respectively (15). Similarly, eight antenatal care visits are associated with a 45.2% reduction in the likelihood of under-five mortality (16, 17).

The increased risk of fetal death between 32 and 36 weeks of gestation may be linked to a reduced number of antenatal visits. Asymptomatic conditions such as pre-eclampsia, fetal growth restriction, and unexplained intrauterine death may present unexpectedly in the third trimester. More frequent routine visits during this period can help detect these complications earlier, allowing for timely intervention (18). A study based on 54 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from low- and middle-income countries found that only 11.3% of women received eight or more ANC contacts (19). In 2021, the prevalence of compliance with the eight-visit ANC model in SSA was 7.7% (20).

Although Ethiopia adopted the 2016 WHO model recommending eight antenatal care contacts in 2020 to reduce maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity (1, 21), implementation remains limited. The guidelines focus on key ANC principles, including pregnant-woman-centered care, maternal and fetal assessments during initial and follow-up contacts, prevention and treatment of common pregnancy-related issues, counseling and health promotion, as well as strengthening the health system to improve ANC coverage (1).

Although several studies have examined the prevalence and associated factors of eight or more antenatal care contacts, there remains a gap in understanding the specific role of women's knowledge and attitudes toward these contacts. In addition, most of the research relies on secondary data, and no studies have been conducted in the current study area.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess the prevalence and factors associated with receiving eight or more ANC contacts among mothers in Shebel Berenta Woreda, Ethiopia. ANC is crucial for reducing maternal mortality and improving maternal and child health outcomes.

Method and materials

Study area and period

Shebel Berenta Woreda is located in East Gojjam Zone, situated in the north central highlands of Ethiopia in Amhara National Regional State. It extends from 10° 15′ N to 10° 30′ N latitude and from 38° 15′ E to 38° 27′ longitude. It is found 293 km northeast of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Shebel Berenta Woreda has 26 kebeles (4 urban and 22 rural kebeles). Shebel Berenta Woreda has 1 primary hospital, 6 health centers, and 24 health posts. According to the Central Statistics Agency of Ethiopia’s population projection of Woreda in 2023, the total population is 130,412, of which 63,634 are males and 66,778 are females (21). Over the past 6 months 1,683 mothers have given birth, according to the woreda report.

The study was conducted between 15 April and 31 May 2024.

Study design

A community-based cross-sectional study was employed.

Source population

All mothers who gave birth in the last 6 months in Shebel Berenta District were the source population.

Study population

Mothers who gave birth in the last 6 months in selected kebeles of Shebel Berenta District during the data collection period comprised the study population.

Inclusion criteria

Mothers residing in Shebel Berenta District who gave birth within the last 6 months before data collection were included.

Exclusion criteria

Mothers who recently migrated to Shebel Berenta District after childbirth and those unable to provide information during the data collection period were excluded.

Sample size determination

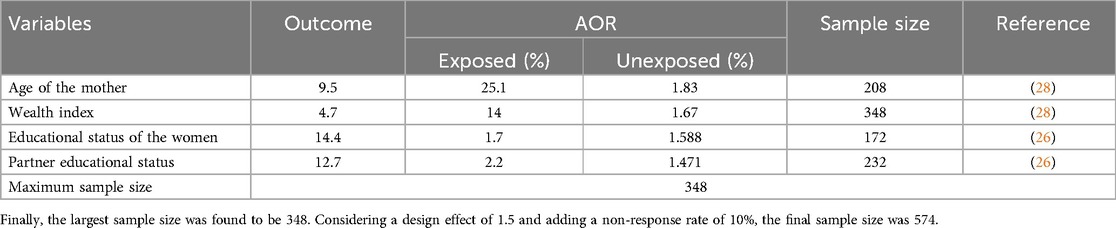

The sample size for each objective was determined using the StatCalc function in OpenEPI Info software version 7.2.6, and the largest calculated sample size was selected for this study (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample size determination for assessing the prevalence and associated factors of eight antenatal care contacts among mothers in Shebel Berenta District, East Gojjam Zone, northeast Ethiopia, 2024.

To determine the prevalence of eight antenatal care contacts, the single population proportion formula was used, based on the following assumptions:

where N is the minimum sample size required for the study, Z is the standard normal distribution (Z = 1.96) with a 95% confidence interval (CI), P is the prevalence of eight ANC contacts (30.7% in Addis Ababa) (12), and d is a tolerable margin of error (d = 0.05). Therefore, the sample size for the first objective is 327.

Sampling technique

To ensure a comprehensive understanding of the prevalence and associated factors of eight or more ANC contacts in Shebel Berenta District, a stratified sampling method was employed. Initially, the population was divided into two strata based on urban and rural settings, given the district's mix of both. A total of 4 urban and 22 rural kebeles were identified. Stratified sampling was used to ensure adequate representation of both urban and rural populations. Of the kebeles, 30% (eight rural and two urban) were randomly selected from each stratum. With each selected kebele, a list of mothers who had given birth in the past 6 months was obtained from health extension workers. Simple random sampling within the selected kebele was then implemented to select households or individuals using the lottery method. If the selected participant was not present during data collection, at least two revisits were made to interview her on the other day. If she was still unavailable, the next eligible woman was selected and interviewed.

Data collection procedure

Data were collected using a pre-tested semi-structured questionnaire through the Kobo Collect mobile application. The process was conducted by four diploma-level midwives under the supervision of two BSc midwives. The principal investigator oversaw the overall data collection process. Both the data collectors and supervisors were trained by the principal investigator. Only mothers who were willing to participate and had signed the informed consent form were interviewed.

Data quality control

The data collection tool was primarily prepared in the English language. It was then translated into the local language (Amharic). Finally, it was re-translated back into English to check its accuracy and consistency. The questionnaire was pre-tested on a 5% sample size from Mankorkuay Kebele in Enemay Woreda. Training was provided to data collectors and supervisors both 1 day before and 1 day after the pretest. The training covered the objectives of the study, the data collection tool, procedures for data collection, and methods for ensuring the completeness of the data. To maintain data quality, proper coding and categorization were implemented. Each day, the principal investigator and supervisors reviewed the collected data for completeness, accuracy, clarity, and consistency. The reliability of the Likert scale variables was assessed using Cronbach's alpha (0.807).

Dependent variables

The dependent variables were the eight and above ANC contacts.

Independent variables

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics included maternal age, maternal and husband’s educational status, maternal occupation, marital status, wealth index, residence, religion, type of family, family size, age at marriage, and health insurance coverage.

Obstetrics characteristics

Obstetric characteristics included number of pregnancies, parity, place of delivery, contraceptive use, birth interval, birth order, whether the pregnancy was planned, experience of pregnancy-related complications, timing of ANC initiation, and awareness of pregnancy complications.

Health service-related factors

Health service-related factors included the type of institution being attended (private or governmental).

Information and decision-making-related characteristics

Information and decision-making-related characteristics included media exposure, the primary decision-maker regarding maternal healthcare, and knowledge and attitudes toward ANC contacts.

Operational definitions

Media exposure

Media exposure was obtained by aggregating women's exposure to television, radio, and newspapers. Women were considered exposed if they accessed any of these media at least once a week (22).

Measurement of household wealth index

The household wealth index, used as a proxy indicator for socioeconomic status, was calculated using principal component analysis (23).

Knowledge of ANC

The minimum and maximum scores for knowledge of ANC were 0 and 18, respectively. Based on the total score from the knowledge assessment variables, participants scoring above the mean were considered knowledgeable, while those scoring below the mean were classified as having poor knowledge (24).

Attitude toward ANC

The total attitude score toward ANC was in the range of 8–40. Women scoring above the mean were considered to have a good attitude (24).

Data processing and analysis

Data were collected through the Kobo Tools app and then exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 27 for processing and analysis. Descriptive statistics for different variables were presented as frequency, percentage tables, and pie charts. Logistic regression was used to identify variables significantly associated with the outcome. Both bivariable and multivariable logistic regressions were performed to examine associations between independent variables and the outcome. Variables with a p-value <0.25 in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariable model. Multi-collinearity among independent variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor (1.17) and tolerance tests. In the multivariable analysis, adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% CIs were used to determine the strength of the association. Variables with p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The model's fitness was confirmed by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (0.427), indicating a good fit for the logistic regression model.

A principal component analysis was employed to determine the household wealth index. Initially, wealth index variables were selected, then descriptive statistics and standard deviations were calculated. Variables that met the assumptions of principal component analysis were retained, and wealth index quintiles were created by ranking the cases.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from Wollo University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, on behalf of the Research Ethics Review Committee (reference number CMHS/519/2024). A formal letter requesting permission and support was sent from the Wollo University Department of Midwifery to the Shebel Berenta Woreda Health Office, and from there to each selected kebele leader. All study participants were informed about the purpose, risks, benefits, and confidentiality of the study, as well as their right to refuse participation. Written and signed voluntary consent was obtained from all participants before the interview. Respondents were also assured that the information they provided would be treated with complete confidentiality and would not cause them any harm.

Results

Sociodemographic factors

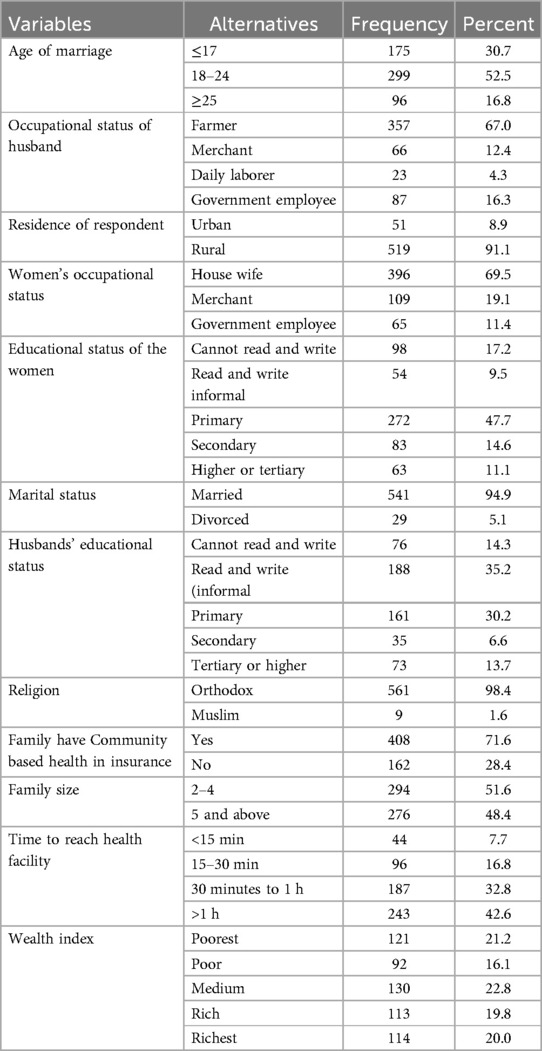

A total of 570 participants took part in this study, with a response rate of 99.3%. The mean age of the women was 29 ± 6.65 years. Most of the women (94.9%) were married, and 299 (52.5%) were married between the ages of 18 and 24 years. Most respondents (98.4%) identified as Orthodox Christian. The majority of the women were housewives (69.5%). Of the women, 98 (17.2%) could not read and write, and 121 (21.2%) were in the poorest wealth index category (Table 2).

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of women who gave birth in Shebel Berenta District, East Gojjam Zone, northeast Ethiopia, 2024 (N = 570).

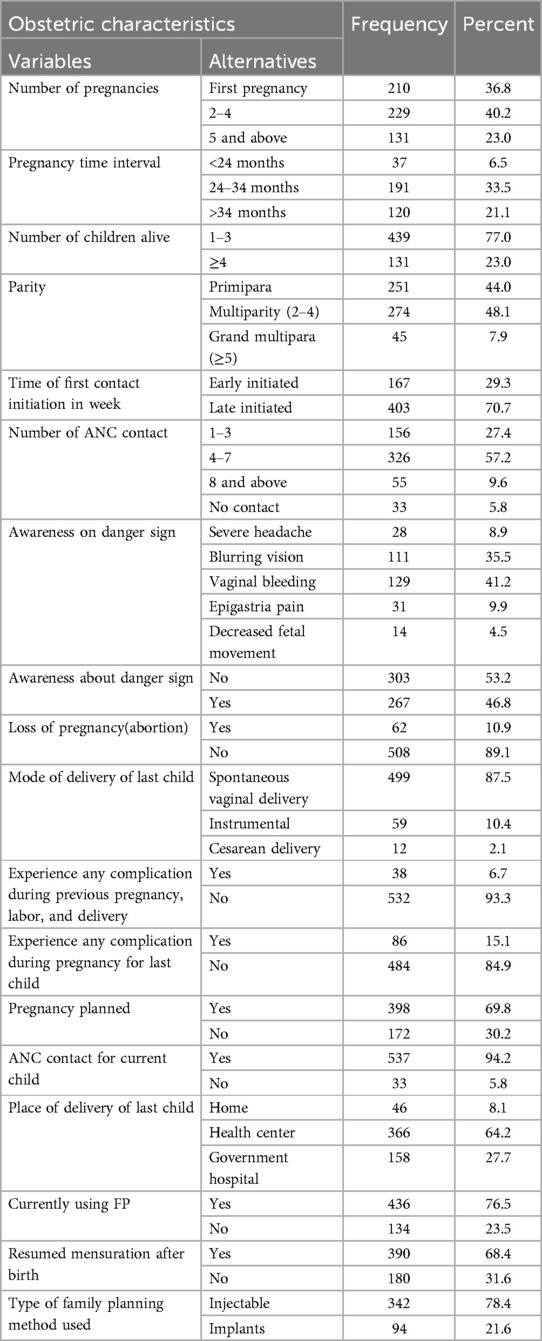

Obstetric factors affecting ANC utilization among pregnant women

Of the women participating in this study, 436 (76.5%) were using modern family planning methods, of whom 78% used injectables. Of the pregnancies, 398 (69.8%) were planned. Among the participants, 216 (37.9%) were experiencing their first pregnancy. Of the mothers who had ANC contact, 403 (70.7%) started antenatal care late (after 12 weeks of gestation). More than half (53.2%) of the pregnant mothers had no awareness of danger signs during pregnancy. Of the mothers, 46 (8.1%) gave birth at home (Table 3).

Table 3. Obstetric characteristics of women who gave birth in Shebel Berenta District, East Gojjam Zone, northeast Ethiopia, 2024 (N = 570).

Knowledge and attitude toward ANC among pregnant women

More than half of the women (306, 53.7%) had poor knowledge about ANC contact, while the majority (94.4%) had a good attitude toward it.

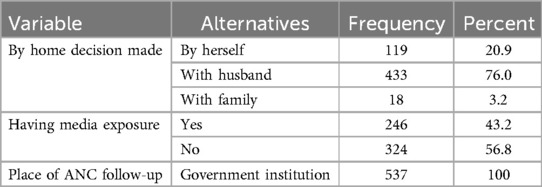

Health service and decision-making characteristics toward ANC among pregnant women

All women received antenatal care from government institutions during their pregnancy. Only 119 (20.9%) women made healthcare decisions independently, and 324 (56.8%) had no media exposure during their pregnancy (Table 4).

Table 4. Health service and decision-making characteristics of women who gave birth in Shebel Berenta District, East Gojjam Zone, northeast Ethiopia, 2024 (N = 570).

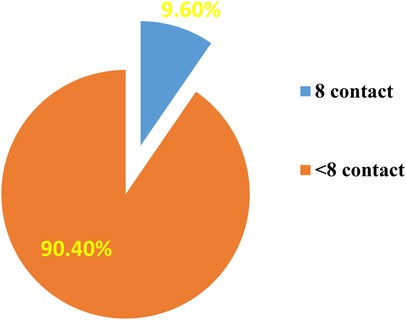

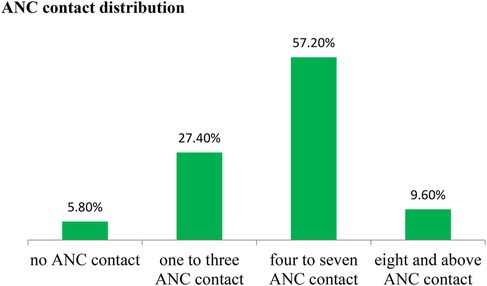

Magnitude and distribution of eight or more ANC contacts among pregnant women

The prevalence of eight or more antenatal care contacts was 9.6% (95% CI: 7.4–12.3) among pregnant women (Figures 1, 2).

Figure 1. Magnitude of eight ANC contacts among women who gave birth in Shebel Berenta District, East Gojjam Zone, northeast Ethiopia, 2024 (N = 570).

Figure 2. Distribution of ANC contacts among women who gave birth in Shebel Berenta District, East Gojjam Zone, northeast Ethiopia, 2024 (N = 570).

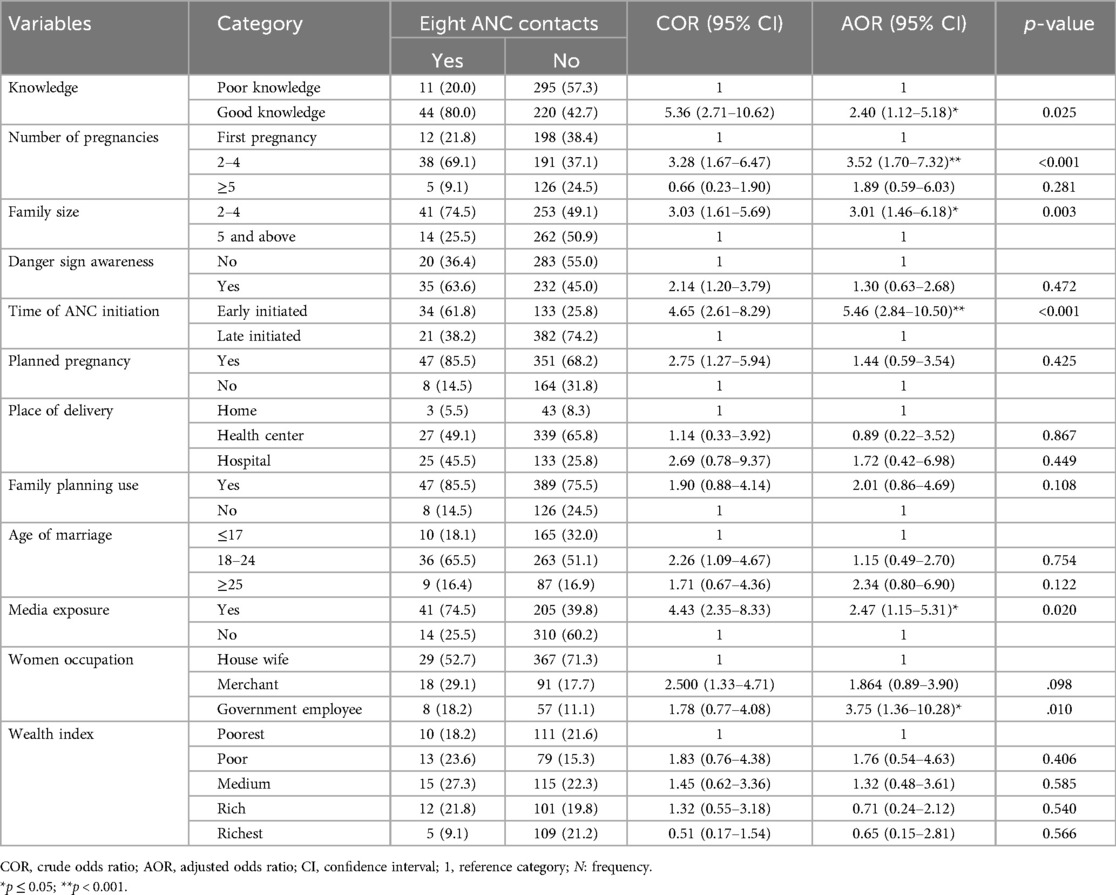

Factors associated with eight or more ANC contacts among pregnant women

In the bivariate analysis, 12 independent variables were identified as candidates for multivariable analysis at a p-value of <0.25. These included knowledge about ANC, wealth index, number of pregnancies, family size, awareness of danger signs, timing of the first ANC contact, whether the pregnancy was planned, place of delivery, family planning use, media exposure, and women's occupation. All these variables were included in the multivariable analysis using the backward stepwise variable selection method. Knowledge about ANC, media exposure, timing of the first ANC contact, women's occupational status, number of pregnancies (gravidity), and family size were significantly associated with attending eight or more antenatal care contacts (p-value <0.05%; 95% confidence level).

In this study, women with good knowledge of ANC were 2.4 times more likely to have eight or more ANC visits, highlighting the importance of awareness in service utilization (AOR = 2.402; 95% CI: 1.115–5.175). Women who had media exposure were 2.47 times more likely to attend eight or more ANC visits compared to those who had no media exposure (AOR = 2.47; 95% CI: 1.15–5.306). Women who initiated the first ANC contact early were 5.64 times more likely to have eight or more ANC visits than those who started late (AOR = 5.46; 95% CI: 2.837–10.51). Women employed in government positions were 3.75 times more likely to have eight or more ANC visits than housewives (AOR = 3.745; 95% CI: 1.364–10.28). Women with two to four pregnancies were 3.524 times more likely to have eight or more ANC visits compared to primigravida women (AOR = 3.524; 95% CI: 1.696–7.32). In addition, women from households with fewer than five members were 3.005 times more likely to have eight or more ANC contacts than those with five or more family members (AOR = 3.005; 95% CI: 1.461–6.179). These factors were all significantly associated with completing eight or more ANC contacts (Table 5).

Table 5. Factors associated with eight ANC contacts among women who gave birth in Shebel Berenta District, East Gojjam Zone, northeast Ethiopia, 2024 (N = 570).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the prevalence and factors associated with achieving eight or more ANC contacts among women in Shebel Berenta District. The findings revealed that the prevalence of eight or more antenatal care contacts was 9.6% (95% CI: 7.4–12.3) among women who gave birth in the district. This result aligns with studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries using data from 54 DHS and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (19), as well as studies from Benin and Cameron (25).

The prevalence in this study is higher than that reported in Bangladesh (26) and several African countries, including Mozambique, Mali, Guinea, Senegal, Uganda, and Zambia (25), as well as in Delta state in southern Nigeria (27), Rwanda (28), and Ethiopia (12). The difference might be related to variations in sociocultural factors, study settings, and periods.

The prevalence found in this study was lower than that reported in studies conducted in Nigeria (25, 29), Ghana (15, 30), and Liberia (31). The difference might be related to variations in sociocultural factors, study settings, and the timing of adoption and implementation of the newly recommended WHO antenatal care contact model. In Ethiopia, the new WHO model was only implemented at the end of 2022.

In this study, family size emerged as an important determinant of eight or more ANC contacts. Women from households with fewer than five members were three times more likely to complete eight or more ANC contacts compared to those from households with five or more members. This finding aligns with the DHS-based multi-level analysis conducted across 54 countries (19), as well as a study from Palestine (32). A possible explanation is that women in smaller households may have fewer domestic responsibilities and receive greater social and emotional support from their husbands and families, facilitating ANC visits.

Women with good knowledge about ANC were twice as likely to have eight or more ANC contacts compared to those with poor knowledge. This may be due to their greater understanding of the importance, timing, and frequency of ANC visits, which encourages them to seek appropriate healthcare and adhere to regular follow-ups during pregnancy. Good knowledge of ANC also allows women to recognize the risks associated with inadequate prenatal care, empowering them to prioritize their health and attend ANC appointments consistently.

Women exposed to media were twice as likely to have eight or more ANC contacts compared to those without media exposure, in line with findings from various studies (22, 27, 33, 34). This association may be explained by the role of mass media in promoting positive health-seeking behaviors through dissemination of information about the benefits of regular and timely ANC. Media also informs women about available services and health facility hours. Effective use of media platforms can improve maternal and child health outcomes by motivating women to seek and maintain ANC throughout pregnancy (26, 33, 34). Women with access to health information are generally more aware of the benefits of ongoing maternal healthcare, danger signs, and pregnancy-related complications than those without such access (35).

Women employed by the government were four times more likely to have eight or more contacts compared to housewives. This result is in line with evidence from 36 sub-Saharan African countries (33). This can be explained by government-employed women having better sociocultural attitudes toward the importance of ANC follow-up, stronger adherence to policy implementation, and generally more proactive health-seeking behaviors regarding ANC visits (33).

Women who initiated ANC contact early were five times more likely to have eight or more antenatal care contacts compared to those who started late. This result is consistent with studies conducted in Benin, Palestine, and Nigeria (32, 36). Early initiation allows for comprehensive monitoring of maternal health, timely detection of complications, and prompt interventions, which contribute to a higher number of ANC visits. In addition, women who start ANC early are more likely to receive essential health education on nutrition, lifestyle modification, birth preparedness, and danger signs during pregnancy. This fosters a stronger commitment to their pregnancy health and a positive attitude toward seeking healthcare, empowering them to actively participate in their pregnancy care and adhere to the recommended ANC visit schedule.

Women with two to four pregnancies were three times more likely to have eight antenatal care contacts compared to first-time pregnant women. This result contradicts with findings from multi-country representative data (25) and a study conducted across 36 sub-Saharan African countries (33). The discrepancy may be due to sociocultural differences, the time gap between studies, and the fact that women with multiple pregnancies tend to have greater experience and familiarity with the healthcare system and providers. Their increased knowledge and established perception of the importance of follow-up likely contribute to why women with two to four pregnancies are more likely to attend frequent ANC contacts compared to first-time mothers.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strength of this study lies in being the first in Ethiopia to use primary data after the implementation of the new antenatal care contact model aimed at improving maternal and child health outcomes. In addition, the community-based design allowed for the collection of adequate information.

However, as a community-based cross-sectional study, there is potential for recall bias, which may have led to an overestimation or underestimation of the prevalence of eight or more antenatal care contacts. Nevertheless, we attempted to ask questions related to the services received during antenatal care, including what was provided and how it was delivered.

Conclusion

This study showed a low prevalence of eight or more antenatal care contacts. Key factors significantly associated with increased ANC visits included good knowledge about ANC, media exposure, early initiation of ANC, being a government employee, having two to four pregnancies, and a household size of fewer than five members.

These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions to improve antenatal care utilization. Strategies should focus on enhancing community education, expanding media campaigns on the importance of ANC follow-up, and raising awareness about relevant policies for the community.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from Wollo University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, on behalf of the Research Ethics Review Committee (reference number CMHS/519/2024). A formal letter requesting permission and support was written from the Wollo University Department of Midwifery to the Shebel Berenta Wereda Health Office and from there to each selected kebele leader. All the study participants were informed about the purpose, risks, benefits, and confidentiality of the study, as well as their right to refuse. Written and signed voluntary consent was obtained from all study participants before the interview.

Author contributions

NA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wollo University College of Medicine and Health science ethical review committee for allowing us to conduct this research. We also express our gratitude to the data collectors for their valuable contribution in collecting accurate data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience: screening, diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis disease in pregnant women. Evidence-to-action brief: Highlights and key messages from the World Health Organization's 2016 global recommendations. World Health Organization (2023). Available online at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/365953 (Accessed July 30, 2025).

2. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience. Geneva: World Health Organization (2018).

3. Mebratie AD. Receipt of core antenatal care components and associated factors in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. Front Glob Womens Health. (2024) 5:1169347. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2024.1169347

4. Afulani PA. Determinants of stillbirths in Ghana: does quality of antenatal care matter? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2016) 16(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0925-9

5. Kuhnt J, Vollmer S. Antenatal care services and its implications for vital and health outcomes of children: evidence from 193 surveys in 69 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open. (2017) 7(11):e017122. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017122

6. Nimi T, Fraga S, Costa D, Campos P, Barros H. Prenatal care and pregnancy outcomes: a cross-sectional study in Luanda, Angola. Int J Gynecol Obstet. (2016) 135:S72–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.08.013

7. Rahman A, Nisha MK, Begum T, Ahmed S, Alam N, Anwar I. Trends, determinants and inequities of 4(+) ANC utilisation in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. (2017) 36(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s41043-016-0078-5

8. World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016).

9. World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000 to 2020: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division: Executive Summary. Geneva: World Health Organization (2023).

10. Downe S, Finlayson K, Tunçalp Ö, Gülmezoglu AM. Provision and uptake of routine antenatal services: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 6(6):1–94. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012392.pub2

11. Terefe AN, Gelaw AB. Determinants of antenatal care visit utilization of child-bearing mothers in Kaffa, Sheka, and Bench Maji zones of SNNPR, southwestern Ethiopia. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. (2019) 6:2333392819866620. doi: 10.1177/2333392819866620

12. Woldeamanuel B, Belachew T. Risk factors associated with frequency of antenatal visits, number of items of antenatal care contents received and timing of first antenatal care visits in Ethiopia: multilevel mixed-effects analysis. Research Square [Preprint] (2020). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-110214/v1

13. Lavin T, Pattinson RC, Kelty E, Pillay Y, Preen DB. The impact of implementing the 2016 WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience on perinatal deaths: an interrupted time-series analysis in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. BMJ Glob Health. (2020) 5(12):e002965. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002965

14. McDiehl RP, Boatin AA, Mugyenyi GR, Siedner MJ, Riley LE, Ngonzi J, et al. Antenatal care visit attendance frequency and birth outcomes in rural Uganda: a prospective cohort study. Matern Child Health J. (2021) 25:311–20. doi: 10.1007/s10995-020-03023-0

15. Akum LA, Offei EA, Kpordoxah MR, Yeboah D, Issah A-N, Boah M. Compliance with the World Health Organization’s 2016 prenatal care contact recommendation reduces the incidence rate of adverse birth outcomes among pregnant women in northern Ghana. PLoS One. (2023) 18(6):e0285621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285621

16. Oduse S, Zewotir T, North D. The impact of antenatal care on under-five mortality in Ethiopia: a difference-in-differences analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03531-5

17. World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience: Summary: Highlights and Key Messages from the World Health Organization’s 2016 Global Recommendations for Routine Antenatal Care. Geneva: World Health Organization (2018).

18. Hofmeyr GJ, Hodnett ED. Antenatal care packages with reduced visits and perinatal mortality: a secondary analysis of the WHO antenatal care trial-commentary: routine antenatal visits for healthy pregnant women do make a difference. Reprod Health. (2013) 10(1):1–2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-20

19. Jiwani SS, Amouzou-Aguirre A, Carvajal L, Chou D, Keita Y, Moran AC, et al. Timing and number of antenatal care contacts in low and middle-income countries: analysis in the countdown to 2030 priority countries. J Glob Health. (2020) 10(1):1–12. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010502

20. Odusina EK, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Seidu A-A, Budu E, Zegeye B, et al. Noncompliance with the WHO’s recommended eight antenatal care visits among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis. BioMed Res Int. (2021) 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2021/6696829

21. Islam MM, Masud MS. Determinants of frequency and contents of antenatal care visits in Bangladesh: assessing the extent of compliance with the WHO recommendations. PLoS One. (2018) 13(9):e0204752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204752

22. Gebeyehu FG, Geremew BM, Belew AK, Zemene MA. Number of antenatal care visits and associated factors among reproductive age women in sub-Saharan Africa using recent demographic and health survey data from 2008 to 2019: a multilevel negative binomial regression model. PLoS Global Public Health. (2022) 2(12):e0001180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0001180

23. Saaka M, Awini S, Kizito F, Hoeschle-Zeledon I. Fathers’ level of involvement in childcare activities and its association with the diet quality of children in northern Ghana. Public Health Nutr. (2023) 26(4):771–8. doi: 10.1017/S1368980022002142

24. Kebede AA, Taye BT, Wondie KY. Factors associated with comprehensive knowledge of antenatal care and attitude towards its uptake among women delivered at home in rural Sehala Seyemit district, northern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. (2022) 17(10):e0276125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276125

25. Fagbamigbe AF, Olaseinde O, Setlhare V. Sub-national analysis and determinants of numbers of antenatal care contacts in Nigeria: assessing the compliance with the WHO recommended standard guidelines. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03837-y

26. Ekholuenetale M. Prevalence of eight or more antenatal care contacts: findings from multi-country nationally representative data. Global Pediatric Health. (2021) 8:2333794X211045822. doi: 10.1177/2333794X211045822

27. Sui Y, Ahuru RR, Huang K, Anser MK, Osabohien R. Household socioeconomic status and antenatal care utilization among women in the reproductive-age. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:724337. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.724337

28. Sserwanja Q, Nuwabaine L, Gatasi G, Wandabwa JN, Musaba MW. Factors associated with utilization of quality antenatal care: a secondary data analysis of Rwandan demographic health survey 2020. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22(1):812. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08169-x

29. Feng Y, Ahuru RR, Anser MK, Osabohien R, Ahmad M, Efegber AH. Household economic wealth management and antenatal care utilization among business women in the reproductive-age. Afr J Reprod Health. (2021) 25(6):143–54. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2021/v25i6.15

30. Ekholuenetale M, Nzoputam CI, Barrow A. Prevalence and socioeconomic inequalities in eight or more antenatal care contacts in Ghana: findings from 2019 population-based data. Int J Womens Health. (2021):349–60. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S306302

31. Ekholuenetale M, Nzoputam CI, Barrow A. Effects of socioeconomic factors and booking time on the WHO recommended eight antenatal care contacts in Liberia. PLOS Global Public Health. (2022) 2(2):e0000136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000136

32. Horino M, Massad S, Ahmed S, Abu Khalid K, Abed Y. Understanding coverage of antenatal care in Palestine: cross-sectional analysis of Palestinian multiple indicator cluster survey, 2019–2020. PLoS One. (2024) 19(2):e0297956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0297956

33. Tessema ZT, Tesema GA, Yazachew L. Individual-level and community-level factors associated with eight or more antenatal care contacts in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from 36 sub-Saharan African countries. BMJ Open. (2022) 12(3):e049379. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049379

34. Ekholuenetale M, Benebo FO, Idebolo AF. Individual-, household-, and community-level factors associated with eight or more antenatal care contacts in Nigeria: evidence from demographic and health survey. PLoS One. (2020) 15(9):e0239855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239855

35. Hailemariam T, Atnafu A, Gezie LD, Tilahun B. Utilization of optimal antenatal care, institutional delivery, and associated factors in northwest Ethiopia. Sci Rep. (2023) 13(1):1071. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-28044-x

36. Ekholuenetale M, Nzoputam CI, Barrow A, Onikan A. Women’s enlightenment and early antenatal care initiation are determining factors for the use of eight or more antenatal visits in Benin: further analysis of the demographic and health survey. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. (2020) 95(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s42506-020-00041-2

Keywords: eight contacts, pregnant women, Ethiopia, antenatal care, associated factors

Citation: Abebaw N, Negesse Y, Begashw A, Amare D, Tsegaw G, Meshesha D and Geto K (2025) Prevalence and associated factors of eight antenatal care contacts among mothers who give birth in Shebel Berenta district, East Gojjam zone, northeast Ethiopia, 2024. Front. Reprod. Health 7:1531380. doi: 10.3389/frph.2025.1531380

Received: 20 November 2024; Accepted: 14 July 2025;

Published: 11 August 2025.

Edited by:

Dorina Onoya, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO), South AfricaReviewed by:

Hari Ram Prajapati, Banaras Hindu University, IndiaAlelign Tasew Jema, Madda Walabu University, Ethiopia

Copyright: © 2025 Abebaw, Negesse, Begashw, Amare, Tsegaw, Meshesha and Geto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nigusie Abebaw, bmlndXNpZWFiZWJhd0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Nigusie Abebaw

Nigusie Abebaw Yezbalem Negesse1

Yezbalem Negesse1