- 1Department of Population Health Sciences, Georgia State University School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 2Department of Health Policy and Behavioral Sciences, Georgia State University School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 3Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 4Gangarosa Department of Environmental Health, Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 5Hubert Department of Global Health, Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA, United States

Introduction: Menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) policy initiatives have emerged as a key strategy to improve adolescent MHH, particularly through the expansion of state-level legislation aimed at increasing access to menstrual materials in K-12 schools in the United States (US). However, limited research has evaluated the implementation or effectiveness of these policies, and efforts to rigorously track and characterize existing policies remain limited. This study systematically reviewed and characterized state-level policies concerning menstrual material access in K-12 schools.

Methods: We conducted a comprehensive search of all 50 US state government websites and legal databases to identify relevant legislation. Using MHH domains covered by the indicators recommended by the Global MHH Monitoring Group, we characterized policies. We also estimated policy reach by state and overall using National Center for Education Statistics enrollment data.

Results: We found that 32 (64%) US states have enacted policies since 2017, which have the potential to improve MHH for approximately nine million, or 34%, of K-12 students. Most policies lack comprehensive coverage of essential MHH domains, including only three of the seven MHH domains on average.

Discussion: These findings highlight the need for more rigorous research to evaluate the effectiveness of different policies and identify the best strategies for implementation.

1 Introduction

Globally, adolescents in both high- and low-income communities face many barriers to safe, hygienic, and dignified menstruation in school settings (1–6). Key challenges include no or inadequate access to menstrual material, a lack of private bathrooms, and insufficient menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) education (1, 7–10). These barriers negatively affect the health and well-being of menstruating students (1, 3, 11). Furthermore, when schools lack adequate MHH resources (e.g., menstrual material) and infrastructure (e.g., private bathrooms), they risk exacerbating existing health, economic, and social disparities by preventing adolescents from practicing necessary behaviors and having positive experiences during menstruation. Adolescents unable to effectively manage menstruation—particularly while in school—may experience declines in participation and attendance, which can reduce academic performance, increase grade repetition and dropout, and decrease economic potential and quality of life (1, 3, 7, 12–14). Since adolescence is a critical period for developing health capabilities (15–17), ensuring MHH needs are met at menarche and throughout puberty is vital for breaking cycles of inequity (11, 18).

Policy initiatives have emerged as a common strategy to address barriers to managing menstruation and to improve MHH among adolescents (4, 5, 19–21). Some countries have implemented comprehensive policies addressing multiple aspects of MHH, while others are narrower in scope (e.g., reducing or removing taxes on menstrual materials). However, many countries lack policies altogether (4, 5). The expansion of policy in the United States (US) has been particularly significant, overwhelmingly consisting of state-level legislation to increase adolescents’ access to menstrual materials in K-12 schools (21–23). Between 2017 and 2022, 21 states and territories passed policies focused on the provision of menstrual materials in schools (21). Amidst this rapid expansion of policies, there has been no systematic evaluation of these policies’ effectiveness or their implementation — aside from one study in Chicago Public Schools (24). Moreover, efforts to rigorously track and characterize existing policies remain limited.

This study addresses a critical gap in understanding MHH progress in the US by focusing on the most common adolescent-focused legislation: policies on menstrual material access in K-12 schools. This focus complements prior research on the only other type of adolescent-specific MHH legislation in the US, state school health education standards (25). Specifically, we systematically reviewed and characterized state-level policies concerning menstrual material access in K-12 schools using the seven domains covered by the indicators recommended by the Global MHH Monitoring Group (26) and building upon existing research and legislative tracking by non-profit organizations (e.g., Alliance for Period Supplies) and businesses (e.g., Aunt Flow). The seven domains were identified for integration into global and national monitoring efforts in response to the urgent need to understand unmet MHH needs among adolescents and to monitor progress across all aspects of MHH (26). In this study, progress refers to policy formulation and adoption. We do not assess the implementation, effectiveness, or impact of policies. Findings from this study will provide a benchmark for tracking progress and can help guide discussions on creating comprehensive and effective policies.

2 Assessment of policies

2.1 Search strategy

We systematically searched each US state's government website and three legal databases (Bill Track 50, LegiScan, and Casetext) for publicly available state legislation related to menstrual material access in K-12 schools (e.g., public and private elementary, middle, and high schools). Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (27) (see Supplementary Table S1), our search targeted policies addressing menstrual material access because (1) they represent the most common adolescent-focused legislation in the US, and (2) a recent study reviewed the other primary type of adolescent-focused legislation, state school health education standards that may require MHH education (25). Generic search terms included [“menstrual hygiene”, “feminine hygiene”, “menstrual products”, “feminine products”, OR “period products”] AND [“schools”]. States with no relevant legislation were classified as having no policy. The search included all dates and concluded on August 12th, 2024.

2.2 Screening and selection of documents

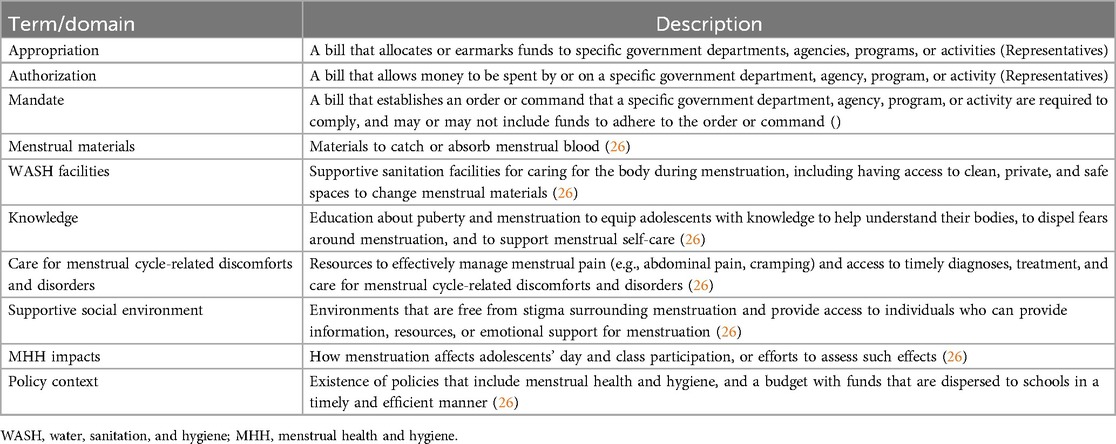

To be eligible for inclusion in analyses, policy documents had to: (i) relate to the provision of menstrual materials in any K-12 schools, (ii) be from one of the 50 US states, (iii) be officially enacted by August 12th, 2024, and (iv) be the most recent and currently enacted version. We included three types of policies: appropriations (allocating or earmarking funds) (28), authorizations (permitting the use of funds) (28), and mandates (requiring specific actions, with or without funding) (29) related to MHH and K-12 schools (Table 1). Official state policy documents and accompanying fiscal notes were included in analyses. Policies that were solely focused on MHH education, were introduced with no resolution, had failed, were still in discussion, or had been amended or were no longer the current policy were excluded. States with failed or unresolved legislation were classified accordingly.

2.3 Data extraction

We developed a data extraction form in Excel using a mixed deductive and inductive approach that involved identifying a conceptual framework, piloting and refining the form, and ensuring consistency through independent extractions and reconciliation. First, we deductively identified critical components of effective and adequate MHH to assess policies, based on recommendations from the Global MHH Monitoring Group, a group of MHH experts and stakeholders who aim to develop indicators for and support countries in monitoring global progress in and out of school. The Global MHH Monitoring Group's recommendations—grounded in UNICEF's proposed operational pillars for MHH and definitions of “menstrual hygiene management,” “menstrual health and hygiene,” and “menstrual health”—identify five domains that are needed to achieve MHH: menstrual materials; water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) facilities; knowledge; care for menstrual cycle-related discomforts and disorders; and a supportive social environment. We also included two other domains—adolescent impacts of MHH and the policy context—based on the indicators recommended by the Global MHH Monitoring Group. Collectively, these seven domains provide a holistic framework for assessing adolescent MHH (26). Descriptions of the MHH domains are provided in Table 1.

Next, we employed an inductive approach by closely reviewing policies to identify additional themes. Three reviewers (EW, PK, and AMB) independently extracted data from the same five policy documents and compared their data to refine the extraction sheet and ensure consistency in extraction.

The finalized data extraction form captured policy details (e.g., year passed, type of policy), target schools and populations (e.g., public, grade levels), implementation cost estimates, funding provisions, and the seven MHH domains. Policies were independently reviewed by two researchers (EW and PK) using the pre-piloted data extraction form. Extraction inconsistencies were resolved by author AMB by re-checking the relevant documents and re-extracting the relevant data.

2.4 Data synthesis

Using R Studio v4.0.5, we generated descriptive statistics about policies in aggregate and sorted MHH domain data to characterize how policies addressed essential MHH requirements. We also estimated the potential reach of each policy using available National Center for Education Statistics [NCES; 2022–2023 for public schools (30), 2021–2022 for private schools (31)] data and the target schools outlined in policies. All data, as well as the pre-piloted data extraction form are publicly available (32).

3 Results

3.1 Overview of policies

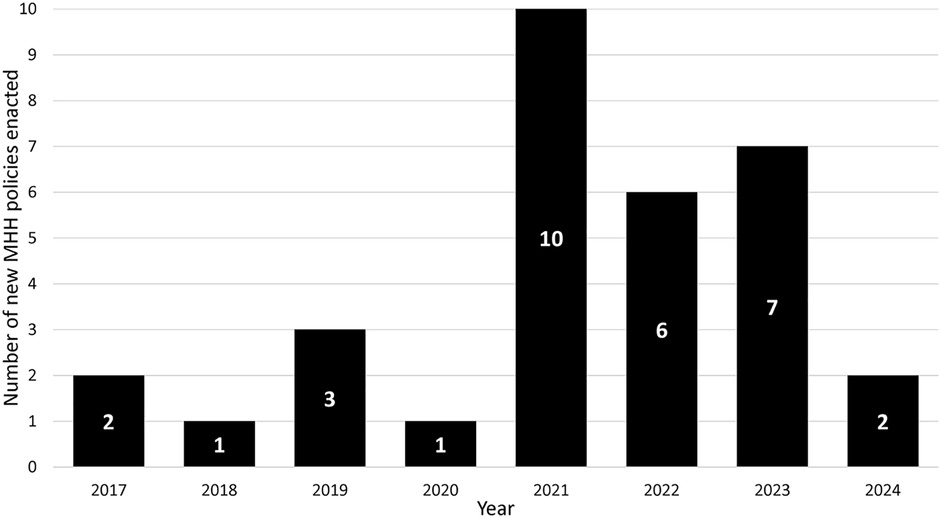

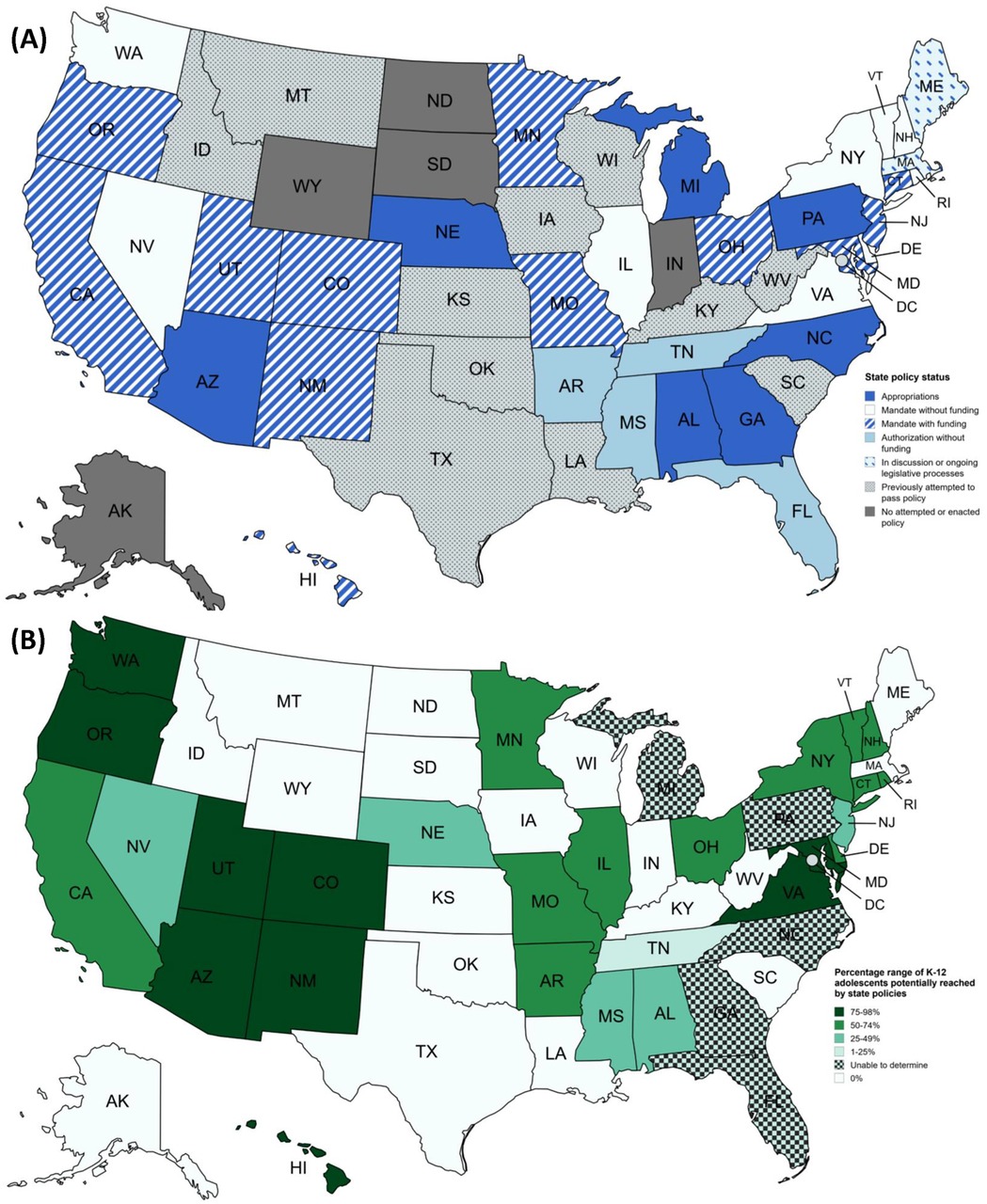

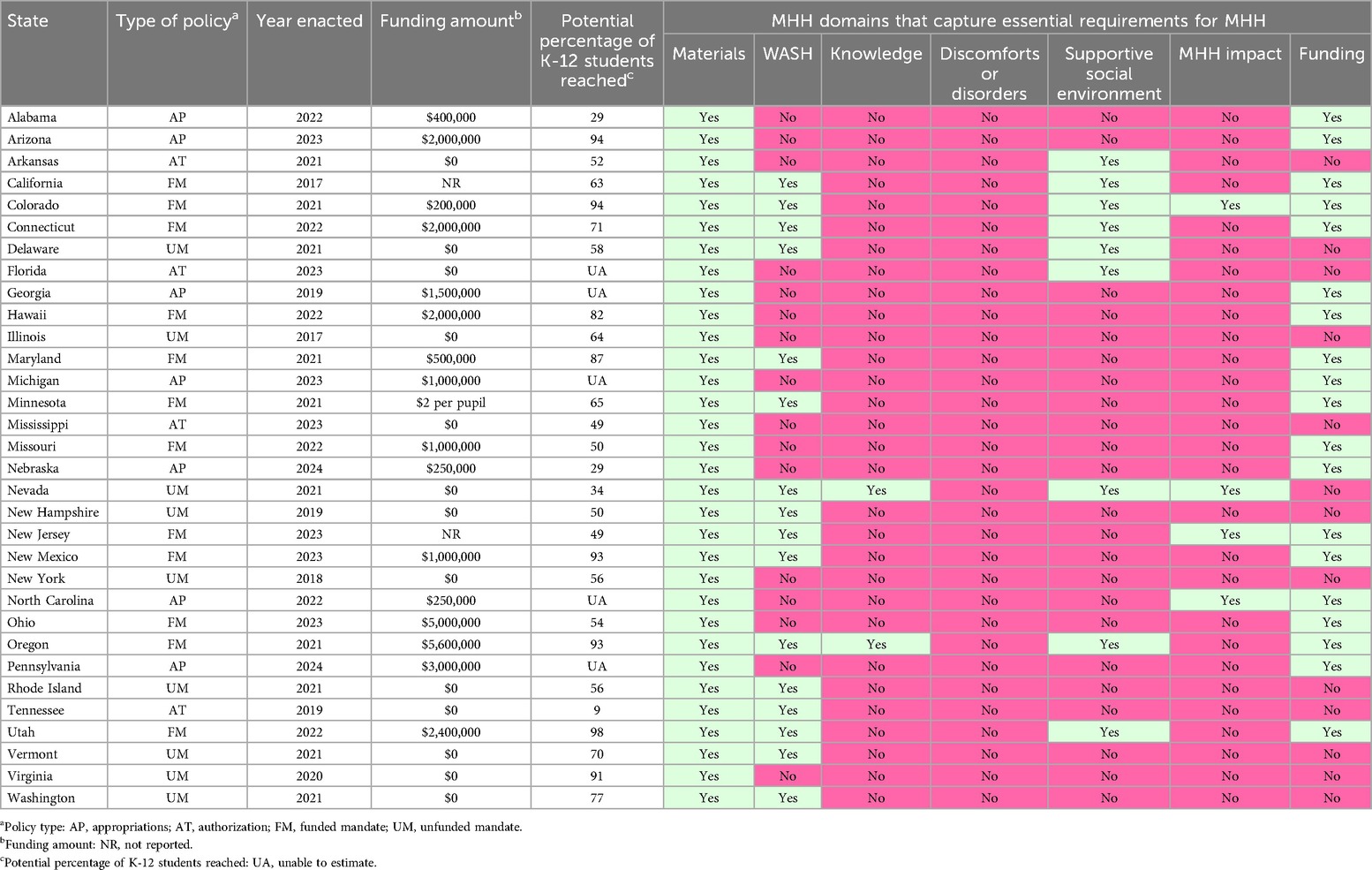

Our search revealed that 32 (64%) of 50 US states enacted policies to increase menstrual materials accessibility in schools (Figure 1A). These policies collectively have the potential to improve MHH for approximately nine million, or 34%, of K-12 students who can menstruate in the US (Figure 1B; Table 2). Additionally, 11 states (22%) unsuccessfully attempted to pass similar legislation and two (4%) had bills in discussion, meaning 45 (90%) US states had engaged MHH-related policy. Most policies were state mandates (21/32, 66%) requiring schools to provide menstrual materials, 12 of which (57%) included funding for implementation. Other policies were appropriations legislation (7/32, 22%) and unfunded authorizations (4/32, 13%). All active policies (n = 32) were enacted since 2017, reflecting a substantial increase in state level support for MHH in schools (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Maps of policy coverage in US states* (A) policy status as of August 12th, 2024, (B) estimated proportion of K-12 adolescents potentially reached by menstrual health and hygiene state policies. *Maps were created with mapchart.net.

Table 2. Type of policy and select details by state based on the most recent and currently enacted version.

3.2 Delineation of roles and responsibilities

Schools and school districts were named as the main frontline implementers of policies in most states (30/32, 94%), with certain school staff (e.g., principals, nurses) being designated to determine where and how menstrual materials should be made available in schools in five policies (16%). Departments or Boards of Education were named as the policy administrators and/or enforcers in 15 (47%) states. Administrative responsibilities included establishing processes and parameters for schools and districts to apply for and receive funds to support implementation, allocating funds, reviewing applications to award funding, and reimbursing school purchases. Enforcement pertained to monitoring policy implementation and compliance and submitting reports to legislative entities.

3.3 Policy features by MHH domain

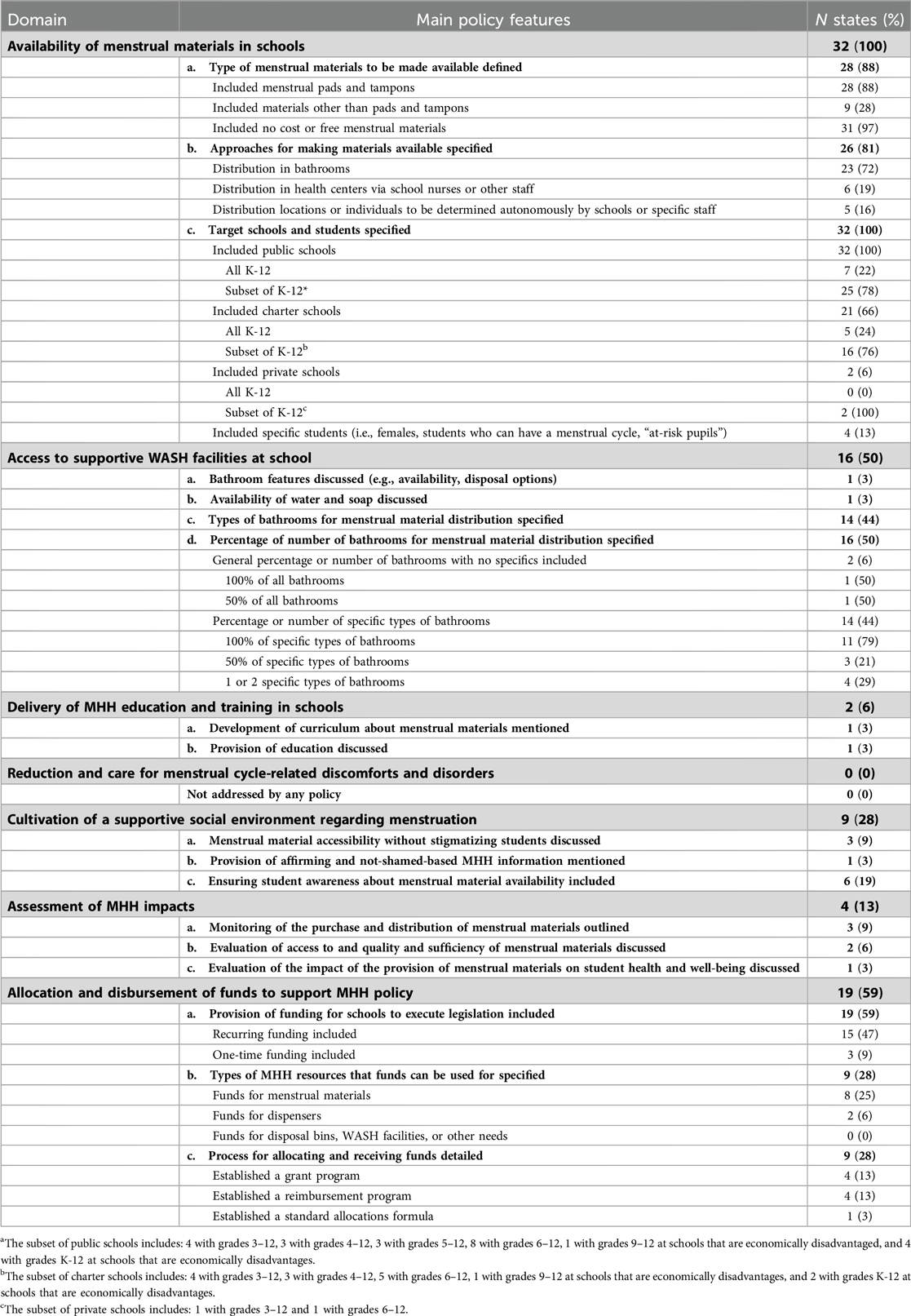

In aggregate, policies included administration and implementation approaches that covered six of seven MHH domains (Tables 2, 3), but on average only included three domains (range: 1–5; Table 2). While all policies (32/32) included information about menstrual materials, other domains were not as extensively covered. Approximately half included funding provisions (19/32, 59%) and WASH facilities (16/32, 50%). Actions for cultivating a supportive social environment (9/32, 28%), assessing MHH impacts (4/32, 13%), and delivering MHH education and training (2/32, 6%) were less common. No policy addressed reduction and care for menstrual cycle-related discomforts and disorders.

Table 3. Main policy features and descriptive statistics by MHH domains that capture essential requirements for MHH as recommended by the global MHH monitoring group (n = 32).

3.3.1 Availability of menstrual materials in schools

The type of menstrual materials, approaches for making materials available to students, and target schools and students were the main aspects of implementation elaborated on in policies (Table 3).

3.3.1.1 Types of menstrual materials

Most policies (28/32, 88%) defined menstrual materials that can or must be made available, all of which included menstrual pads and tampons. Nine policies included flexible language (e.g., “but not limited to”) alongside specified materials to allow schools discretion in selecting materials. One policy (Ohio) also mentioned reuseable materials (e.g., cups, discs). Four policies did not define or specify the type of menstrual materials. No policies specifically noted types of materials that should not be included. All but one policy (Arizona) stated that materials should be provided at no cost.

3.3.1.2 Approaches for making materials available

Most policies (23/32, 72%) primarily focused on implementation strategies to make menstrual materials available in school bathrooms at no cost. Specific distribution strategies within bathrooms largely were absent, although 10 policies mentioned the use or estimated cost of dispensers. Policies in Colorado, Michigan, Ohio, Virginia, and Washington schools, districts, school boards, or school principals to determine appropriate locations or designated individuals for distribution. Six policies targeted school nurses or other staff (e.g., counselors, teachers), either to serve as the sole access point in schools (Florida, Mississippi) or to complement bathroom distribution (Colorado, Vermont, Washington). Alabama's policy had conflicting details, stating that schools could be reimbursed for dispensers for distributing menstrual materials but that materials should be provided “to female students…through a female school counselor, female nurse, or female teacher.”

3.3.1.3 Target schools and students

Every (32/32, 100%) state policy aimed to increase or authorize menstrual material provision in public schools, with most (25/32, 78%) targeting a subset of K-12 public schools (e.g., those serving grades 6–12). Only seven (23%) addressed the availability of menstrual materials in all state K-12 public schools. The remaining 25 pertained to a subset based on grade and/or poverty level. For example, New Hampshire's legislation required all public middle and high schools to make menstrual materials available in bathrooms; and Alabama's appropriations legislation established a Department of Education program to reimburse public schools with grades 5–12 who receive Title I funding to purchase and distribute menstrual materials. Tables 2, 3 provide additional details about schools targeted in policies.

Most state policies also included charter schools (21/32, 66%), five of which addressed menstrual material availability in all K-12 charter schools. Others mirrored public school specifications, pertaining to a subset of schools based on grade and/or poverty level. Only two policies (6%) included private schools. Both of which focused on specific grade levels: 6–12 in New York and 3–12 in Washington.

Four policies (13%) identified specific student populations to receive menstrual materials. Policies from Florida and Ohio mentioned that menstrual materials should be available to “female students”, and Delaware's mentioned students who can have a menstrual cycle. The policy from Michigan targeted “at-risk pupils,” which included those who faced challenges such as economic disadvantage and chronic absenteeism, among others. Michigan's policy further specified the number of materials students should receive: “at a minimum, 20 tampons or menstrual pads each month for the school year.”

3.3.2 Access to supportive WASH facilities at school

Only two policies (6%; Oregon, Colorado) referred to specific bathroom features (e.g., availability, disposal options) and the availability of water and soap, even though the menstrual material availability in bathrooms was the primary implementation action discussed in policies. Oregon's policy defined the features of a bathroom: “Bathroom means a space with a toilet, a sink, and a trash receptacle that is privately accessible to students”. Colorado's policy mentioned that appropriated funds could be used to install and maintain disposal bins for menstrual materials.

The main WASH aspects in policies pertained to the number of bathrooms where materials should be made available. Fourteen policies (44%) specified that menstrual materials should be made available in specific types of bathrooms and approximately half of policies (16/32, 50%) specified the percentage or number of bathrooms where menstrual materials should be made available. Two policies included the percentage of bathrooms where menstrual materials should be made available generally: Minnesota's policy stated that materials should be in 100% of bathrooms and Delaware's stated 50% of all bathrooms. Most policies (14/16, 88%) included the percentage or number of specific types of bathrooms: 11 stated that materials should be in 100% of certain bathrooms, three stated that materials should be in 50% of certain bathrooms, and four stated materials should be in one or two specific bathrooms. Nine policies stated that materials should be available in 100% of bathrooms intended for all genders or that are gender neutral, with the remaining mentioning 50%.

3.3.3 Delivery of MHH education and training in schools

The delivery of MHH education and training was only addressed in two policies (6%; Nevada, Oregon). Nevada's specifically required schools to develop a curriculum on menstrual material access. Oregon's policy required schools to provide “health and sexuality education that includes information on menstrual health,” and to provide and display menstrual product instructions within bathrooms. No details about specific knowledge or skills were included in the policy.

3.3.4 Reduction and care for menstrual cycle-related discomforts and disorders

Menstrual cycle-related discomforts and disorders were not addressed in any policies.

3.3.5 Cultivation of a supportive social environment regarding menstruation

Making menstrual materials available without stigmatizing students, providing affirming and not-shame-based MHH information, and informing students about the availability of menstrual materials were the main actions outlined in policies that related to cultivating a supportive social environment regarding menstruation. Policies from Connecticut, Nevada, and Oregon noted the need for materials to be accessible without stigmatizing those who request them. No specific actions were discussed, though Nevada's policy proposed that schools develop a plan to “ensure access and destigmatize the need for menstrual products.” Additionally, as discussed in Section 3.4, Oregon's policy required schools to provide positive and not-shame-based education and instructions on menstrual materials.

Six policies (19%; Arkansas, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Utah) proposed strategies to ensure student awareness about menstrual material availability, which can help students feel comfortable requesting support. California's policy required schools to post a notice detailing policy requirements and contact information for an individual responsible for maintaining the supply of menstrual materials. Policies from Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, and Florida focused on notifying students about the specific location of materials. Delaware's policy specifically required schools to publish and maintain menstrual material locations on school websites, whereas policies from Arkansas and Florida mentioned informing students generally. For example, Florida's policy states that “Participating schools shall ensure that students are provided appropriate notice as to the availability and location of the products”. Utah's policy was the least descriptive, stating that schools should inform students of the availability of menstrual materials.

3.3.6 Assessment of MHH impacts

No policy included strategies to assess the impact menstruation had on students’ day or class participation. However, four (13%; Colorado, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina) outlined monitoring and/or evaluation strategies to be conducted by schools, district governing bodies, or state education departments. Monitoring strategies targeted specific materials purchased and distributed for reporting to state legislative bodies (e.g., The Senate and House of Representatives, Joint Legislative Education Oversight Committee). Evaluation strategies included assessment of menstrual material access, quality, and sufficiency, and the impact of the provision of materials on student health and well-being.

3.3.7 Allocation and disbursement of funds to support MHH policy

Nineteen policies (59%) included appropriations or funding for implementation, most of which (15/19, 79%) were recurring funds. Twelve of the 21 (57%) enacted mandates established funding mechanisms for schools to execute legislative requirements. However, Colorado's policy only provided funding for certain schools to implement requirements. Unfunded mandates required schools to purchase materials using their existing budget or to obtain them through donations, gifts, grants, or partnerships.

Policies included $1.76 million for policy implementation on average (n = 16), though three policies (California, Minnesota, New Jersey) did not specifically state the amount of the funding to be allocated and funding varied widely (minimum: $200,000 [Colorado], maximum: $5,595,000 [Oregon). Eight of the 19 funded policies (42%) stated that funds were only for the purchase of menstrual materials. Two (Maryland, New Mexico) allocated some money to dispensers. The remaining policies did not include allocation details. No policies specifically allocated funding for disposal bins, WASH facilities, or other needed infrastructure, resources, or education.

Of the 19 policies that include funding, 47% detailed a process or stated that a process should be developed for funds to be allocated to or received by schools. Four policies established a grant program (Colorado, New Mexico, North Carolina, Pennsylvania). Colorado specified that schools with 50% or more students enrolled who are eligible for free or reduced-cost lunch and the Colorado School for the Deaf and the Blind must submit an application to the Department of Education that includes data concerning the number of students enrolled and the number of bathrooms on the property. Pennsylvania's policy outlined the same application process at Colorado, but public school entities with 25% or more students enrolled in free or reduced-cost lunch were eligible. New Mexico's policy stated that “grants of up to $5,000 will be awarded on a first-come, first-serve basis, prioritizing public school units that did not receive an award the previous fiscal year.” North Carolina's policy did not detail the grants program but required that the Department of Education establish and administer a grant program using existing resources and staff. Four other policies established a reimbursement program (Alabama, California, Maryland, Oregon) that required schools to file annual claims of costs. Minnesota uniquely included an allocations formula where schools received “$2 times the adjusted pupil units of the district for the school year” to purchase menstrual materials.

4 Discussion and actionable recommendations

Our systematic review of existing state legislation concerning menstrual material access in K-12 schools reveals progress in policy formulation and adoption, as well as the limitations of current MHH policies across the US. Thirty-two states have passed policies to increase adolescents’ access to menstrual materials in schools since 2017. However, the characterization of policies reveals that existing approaches do not comprehensively address all essential MHH domains as detailed by the Global MHH Monitoring Group. As a result, current policies may fall short in effectively supporting adolescent MHH in schools. Findings offer insights for improving MHH legislation, which can help to facilitate evidence-based policy development with the potential to significantly impact adolescent MHH. We offer five areas of consideration to improve existing policies and to guide the development of new policies: (1) establishing an MHH initiative and policy repository, (2) addressing all MHH domains comprehensively, (3) outlining clear actions and programmatic details, (4) including all relevant age groups and grade levels, and (5) providing adequate funding.

First, tracking and benchmarking MHH policies both for the US and globally is complicated by the lack of a centralized repository of initiatives and policy documents. Identifying policies during our review was challenging, with many only obtained after extensive searches. While this challenge is certainly not unique to MHH policies, the inability to find relevant policies complicates policy benchmarking and communication. Informal searches for resources related to best practices and lessons learned in MHH policy development and implementation also revealed gaps in information sharing. An open-access, full-text repository of initiatives, policies, guidance documents, and implementation toolkits for addressing adolescent MHH in schools would be a valuable step forward. The repository could include iterations over the years to enable assessment of changes made over time, as relevant, and could also support benchmarking for some of the Global MHH Monitoring Group's recommended indicators (26) and ideally connect to surveillance data to track progress in the coming years. We are ready to organize such a repository to address this gap and invite interested policy makers and researchers to contact us to contribute to and update our current database on OSF (32).

Second, many of the MHH domains are not addressed in the MHH policies included in this review, which is consistent with the evaluation of Illinois’ policy conducted in Chicago Public Schools (24), MHH policies in other countries (33, 34), and policies related to MHH education in the US (25). By comparing policy content to the essential MHH domains, we found that policies only covered three domains on average, with no single policy covering more than five of the seven domains. Additionally, a recent study on the only other type of adolescent-specific MHH legislation in the US—state school health education standards—found that the inclusion of MHH education in school health curricula is minimal and inadequate across states. Only three states cover menstrual materials (California, Michigan, and New Jersey) and three include menstruation management (Michigan, Oregon, Utah). Students in Oregon, for example, are taught about managing the physical and emotional changes that occur during puberty and about prioritizing personal care (25). A more holistic approach—one that extends beyond menstrual materials to include reducing and caring for menstrual cycle-related discomforts and disorders, providing education and training, fostering supportive social environments, ensuring menstrual-friendly WASH facilities, securing funding, and evaluating MHH impact—would significantly enhance the capacity of schools to effectively address the needs of menstruating adolescents. Aligning these efforts with ongoing advocacy to integrate MHH into school health education standards, which remains absent in most states (25), could further bolster the effectiveness of MHH policies.

Third, existing policies lack clear actions and programmatic details, limiting their practical implementation. Policies tended to be vague, often focused on the type of menstrual materials to be made available, how materials should be made available to students, and which schools and students will be targeted while omitting critical elements such as a detailed budget, implementation plan, evidence-based practices, or delegation of responsibilities. To improve the use of evidence-based practices and front-line priority setting, clear actions and programmatic details need to be outlined in policies. However, this will require research to determine what types of policies are effective and how to best implement those policies. While the limited number of effectiveness trials of menstrual material provision and educational interventions have demonstrated improved school attendance, MHH knowledge, and wellbeing, more rigorous research is needed to inform best practices for policy design and implementation (2, 4, 5, 35).

Fourth, current policies are not adequately responsive to the decreasing average age at menarche in the US (36), with few pertaining to all K-12 schools and only half including those younger than 11 years old. Research shows a significant trend toward earlier menarche over the past 50–100 years, with the prevalence of early menarche (before age 11) and very early menarche (before age 9) nearly doubling across birth years from 1950 to 2005. These trends are particularly pronounced among adolescents of low socioeconomic status and who are Black, Asian, or multi-racial (36). While only six policies explicitly target economically disadvantaged schools or students, these population-level trends underscore the importance of designing inclusive policies that consider both age and socioeconomic context. The inclusion of adolescents aged 9 and above in policies, with particular attention to low-income, Black, Asian, and multi-racial adolescents, would allow for timely intervention during critical developmental windows and would be responsive to widening MHH disparities.

Fifth, the absence of dedicated funding in nearly half of the policies reviewed, and the lack of budgetary provisions for disposal bins, WASH facilities, or other needed infrastructure, or education, represents a significant barrier to the sustainability and expansion of MHH programming. Without adequate funding to accompany policies, even well-designed policies are unlikely to achieve their intended outcomes. By including specific budget allocations for each MHH domain in policy provisions, state governments can better support the comprehensive MHH needs of adolescents and enable evaluation of policy impacts. Additional research is needed to assess the reach of current policies based on current funding, as well as to determine the optimal level of funding required to facilitate both effective implementation and long-term sustainability.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

This review used a mixed deductive and inductive approach to extract and characterize data, resulting in a comprehensive and rigorous synthesis of US state policies related to menstrual material access in K-12 schools. We intentionally used a structured yet flexible approach due to the novelty of the review and desire to capture in-depth information about policies. However, limiting our review to official state government policy documents focused on menstrual materials in K-12 schools presents some limitations. First, policies addressing other MHH domains that could complement those included in our review may have been excluded; though to our knowledge, other US MHH policies targeting adolescents are uncommon. Those that do exist are restricted to education about menstrual materials, menstrual management, and physiological aspects of menstruation (25). Second, the mere presence or absence of policies or strategies in a policy document does not necessarily reflect concrete action, or that the policy is achieving what it is intended to achieve. A well-recognized issue is the gap between what is articulated in official documents and what is actually implemented, and further, if the policy impacts the lives of those it is intended to serve. Additionally, MHH programs may be implemented in some states without a formal policy and these were not captured. Overall, the findings of this review indicate that few states have made significant steps in the development of a comprehensive set of strategies to address adolescent MHH in schools. However, in-depth evaluation of actual policy implementation, impacts, and resources allocated for state policies is needed to expand upon baseline data produced in this study.

5 Conclusions

Our findings indicate notable legislative expansion in the US toward supporting adolescent MHH, evidenced by 32 states enacting policies to support the provision of menstrual materials in K-12 schools. However, 18 states, representing approximately 7 million school age children who can menstruate, still lack any policy. Most policies lack comprehensive coverage of essential MHH domains, highlighting an urgent need for integrated, holistic approaches. Establishing an open-access, publicly accessible database of policy documents with regular systematic reviews of policy development could facilitate knowledge sharing and the development of more robust policies to strengthen adolescent MHH support.

Author contributions

AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EW: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. PK: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SS-B: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MF: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frph.2025.1589772/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Barrington DJ, Robinson HJ, Wilson E, Hennegan J. Experiences of menstruation in high income countries: a systematic review, qualitative evidence synthesis and comparison to low-and middle-income countries. PLoS One. (2021) 16(7):e0255001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255001

2. Hennegan J, Montgomery P. Do menstrual hygiene management interventions improve education and psychosocial outcomes for women and girls in low and middle income countries? A systematic review. PLoS One. (2016) 11(2):e0146985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146985

3. Hennegan J, Shannon AK, Rubli J, Schwab KJ, Melendez-Torres GJ. Women’s and girls’ experiences of menstruation in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. PLoS Med. (2019) 16(5):e1002803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002803

4. Sommer M, Caruso BA, Torondel B, Warren EC, Yamakoshi B, Haver J, et al. Menstrual hygiene management in schools: midway progress update on the “MHM in ten” 2014–2024 global agenda. Health Research Policy and Systems. (2021a) 19:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-00669-8

5. Sommer M, Caruso BA, Sahin M, Calderon T, Cavill S, Mahon T, et al. A time for global action: addressing girls’ menstrual hygiene management needs in schools. PLoS Med. (2016) 13(2):e1001962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001962

6. Phillips-Howard PA, Caruso B, Torondel B, Zulaika G, Sahin M, Sommer M. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent schoolgirls in low-and middle-income countries: research priorities. Glob Health Action. (2016) 9(1):33032. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.33032

7. Sebert Kuhlmann A, Teni MT, Key R, Billingsley C. Period product insecurity, school absenteeism, and use of school resources to obtain period products among high school students in St. Louis, Missouri. J Sch Nurs. (2024) 40(3):329–35. doi: 10.1177/10598405211069601

8. Deo DS, Ghattargi CH. Perceptions and practices regarding menstruation: a comparative study in urban and rural adolescent girls. Indian J Community Med. (2005) 30(1):33. https://journals.lww.com/ijcm/citation/2005/30010/perceptions_and_practices_regarding_menstruation_.12.aspx

9. Crockett LJ, Deardorff J, Johnson M, Irwin C, Petersen AC. Puberty education in a global context: knowledge gaps, opportunities, and implications for policy. J Res Adolesc. (2019) 29(1):177–95. doi: 10.1111/jora.12452

10. Haver J, Long JL, Caruso BA, Dreibelbis R. New directions for assessing menstrual hygiene management (MHM) in schools: a bottom-up approach to measuring program success (dispatch). Stud Soc Justice. (2018) 12(2):372–81. doi: 10.26522/ssj.v12i2.1947

11. Sommer M, Torondel B, Hennegan J, Phillips-Howard PA, Mahon T, Motivans A, et al. How addressing menstrual health and hygiene may enable progress across the sustainable development goals. Glob Health Action. (2021b) 14(1):1920315. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2021.1920315

12. Thomas C, Melendez-Torres GJ. The experiences of menstruation in schools in high income countries: a systematic review and line-of-argument synthesis. Psychol Sch. (2024) 61(7):2820–44. doi: 10.1002/pits.23192

13. Cotropia CA. Menstruation management in United States schools and implications for attendance, academic performance, and health. Womens Reprod Health. (2019) 6(4):289–305. doi: 10.1080/23293691.2019.1653575

14. Kuhlmann AS, Key R, Billingsley C, Shato T, Scroggins S, Teni MT. Students’ menstrual hygiene needs and school attendance in an urban St. Louis, Missouri, district. J Adolescent Health. (2020) 67(3):444–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.040

15. Bundy DAP, Silva ND, Horton AP, Patton GC, Schultz L, Jamison DT. Child and adolescent health and development: realizing neglected potential. In: Bundy DAP, Silva ND, Horton S, Jamison DT, Patton GC, editors. Child and Adolescent Health and Development. 3rd ed. Chapter 1. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank (2017).

16. Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, et al. Our future: a lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. (2016) 387(10036):2423–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1

17. Baird S, Ezeh A, Azzopardi P, Choonara S, Kleinert S, Sawyer S, et al. Realising transformative change in adolescent health and wellbeing: a second lancet commission. Lancet. (2022) 400(10352):545–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01529-X

18. Phillips-Howard PA, Hennegan J, Weiss HA, Hytti L, Sommer M. Inclusion of menstrual health in sexual and reproductive health and rights. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2018) 2(8):e18. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30204-9

19. Olson MM, Alhelou N, Kavattur PS, Rountree L, Winkler IT. The persistent power of stigma: a critical review of policy initiatives to break the menstrual silence and advance menstrual literacy. PLOS Global Public Health. (2022) 2(7):e0000070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000070

20. Patkar A. Policy and Practice Pathways to Addressing Menstrual Stigma and Discrimination. the Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. (2020). p. 485–509.

21. Francis L, Meraj S, Konduru D, Perrin EM. An update on state legislation supporting menstrual hygiene products in US schools: a legislative review, policy report, and recommendations for school nurse leadership. J Sch Nurs. (2023) 39(6):536–41. doi: 10.1177/10598405221131012

22. Schmitt ML, Booth K, Sommer M. A policy for addressing menstrual equity in schools: a case study from New York city, USA. Front Reprod Health. (2022) 3:725805. doi: 10.3389/frph.2021.725805

23. Weiss-Wolf J. US Policymaking to Address Menstruation: Advancing an Equity Agenda. the Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. (2020). p. 539–49.

24. Shah S, Shenkman J, Chicojay T, Kamiri-Ong J, DiPaolo M, DeClemente T, et al. Building a future for school-based menstruation health and hygiene (MHH): evaluating implementation of a menstrual hygiene management (MHM) policy in Chicago public schools. J Prev Interv Community. (2024) 52(2):353–74. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2024.2379082

25. Sebert Kuhlmann A, Hunter E, Lewis Wall L, Boyko M, Teni MT. State standards for menstrual hygiene education in US schools. J School Health. (2022) 92(4):418–20. doi: 10.1111/josh.13135

26. Hennegan J, Caruso BA, Zulaika G, Torondel B, Haver J, Phillips-Howard PA, et al. Indicators for national and global monitoring of girls’ menstrual health and hygiene: development of a priority shortlist. J Adolescent Health. (2023) 73(6):992–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.07.017

27. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

28. Representatives, United States House of. The House Explained: Glossary of Terms. Washington, DC: US House of Representatives. Available online at: https://www.house.gov/the-house-explained/open-government/statement-of-disbursements/glossary-of-terms

29. Mandate. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster. (2025). Available online at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mandate (Accessed August 07, 2025).

30. Statistics, National Center for Education. Table 203.40. Enrollment in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools, by Level, Grade, and State or Jurisdiction: Fall 2022. US Department of Education (2023). Available online at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d23/tables/dt23_203.40.asp

31. Statistics, National Center for Education. Table 205.80. Private Elementary and Secondary Schools, Enrollment, Teachers, and High School Graduates, by State: Selected Years, 2009 Through 2021. US Department of Education (2023). Available online at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d23/tables/dt23_205.80.asp

32. Ballard AM, Wallace E, Kaza P, Self-Brown S, Freeman MC, Caruso BA. Menstrual health and hygiene in US schools: a policy dataset from a systematic review. [Dataset] OSF. doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/G7C26

33. Alhelou N, Kavattur PS, Rountree L, Winkler IT. ‘We like things tangible:’ a critical analysis of menstrual hygiene and health policy-making in India, Kenya, Senegal and the United States. Glob Public Health. (2022) 17(11):2690–703. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.2011945

34. Head A, Huggett C, Chea P, Suttor H, Yamakoshi B, Hennegan J. Menstrual Health in East Asia and the Pacific: Regional Progress Review. Bangkok: United Nations Children’s Fund, Burnet Institute and WaterAid (2023).

35. Hennegan J. Interventions to Improve Menstrual Health in low-and Middle-income countries: Do We Know What Works? the Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. (2020). p. 637–52.

Keywords: period poverty, menstrual policy, adolescent health, menstrual equity, school-based health

Citation: Ballard AM, Wallace E, Kaza P, Self-Brown S, Freeman MC and Caruso BA (2025) Mapping menstrual health and hygiene progress in US schools: a systematic policy review and comparison across states. Front. Reprod. Health 7:1589772. doi: 10.3389/frph.2025.1589772

Received: 7 March 2025; Accepted: 31 July 2025;

Published: 20 August 2025.

Edited by:

Kokouvi Kassegne, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Tsitsi Masvawure, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, United StatesJacey Minoi, University of Malaysia Sarawak, Malaysia

Copyright: © 2025 Ballard, Wallace, Kaza, Self-Brown, Freeman and Caruso. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: April M. Ballard, YWJhbGxhcmQxMUBnc3UuZWR1

April M. Ballard

April M. Ballard Emily Wallace

Emily Wallace Pranitha Kaza3

Pranitha Kaza3 Shannon Self-Brown

Shannon Self-Brown Matthew C. Freeman

Matthew C. Freeman Bethany A. Caruso

Bethany A. Caruso