- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tzafon Medical Center, Reproductive Medicine, Poriya, Israel

- 2Azrieili Faculty of Medicine in Galilee, Bar-Ilan University, Safed, Israel

Endometriomas are a common manifestation of endometriosis in women of reproductive age and pose a clinical challenge due to their association with pain, infertility, and compromised ovarian reserve. Surgical removal through cystectomy remains the standard intervention, but compelling evidence demonstrates its deleterious impact on ovarian reserve and potential acceleration of ovarian aging. These concerns have prompted an investigation of less invasive alternatives. Among these, ethanol sclerotherapy has emerged as a promising, minimally invasive, often ultrasound-guided procedure offering cyst resolution with minimal trauma to ovarian tissue. This mini-review synthesizes current evidence on ethanol sclerotherapy for the management of endometriomas, with an emphasis on clinical outcomes and implications for fertility preservation. Evidence indicates that ethanol sclerotherapy is highly effective technically, with low rates of major complications. Pain relief is achievable, recurrence rates can be reduced with longer ethanol exposure, and ovarian reserve is preserved compared with cystectomy. Assisted reproduction outcomes suggest comparable pregnancy rates, with some data supporting a higher oocyte yield following sclerotherapy. Nevertheless, the quality of evidence is limited, predominantly derived from observational studies, and results vary regarding long-term efficacy and reproductive outcomes. Ethanol sclerotherapy is best considered a minimally invasive, fertility-sparing option for women seeking to avoid surgery or preserve reproductive potential. Future randomized controlled trials should clarify its role relative to cystectomy and expectant management, establish optimal procedural parameters, and assess long-term outcomes, including ovarian reserve, live birth rates, and cost-effectiveness.

1 Introduction

Ovarian endometriomas are a frequent manifestation of endometriosis in reproductive-age women, affecting up to 55% of those with the condition (1). They pose a significant clinical challenge due to their association with pain, infertility, and decreased ovarian reserve (2–4). Advances in imaging, particularly ultrasound, now enable a reliable diagnosis in most cases (5); however, management remains debated, especially in women who wish to preserve fertility (6, 7). Although cystectomy continues to be regarded as the standard of care, accumulating evidence demonstrates its detrimental effect on ovarian reserve, with the potential to accelerate ovarian aging (8–10).

These concerns have shifted attention toward fertility-preserving strategies. Minimally invasive options, such as ablative techniques or aspiration combined with sclerotherapy, aim to manage endometriomas while sparing healthy ovarian tissue. Among the sclerosing agents investigated, ethanol has been most widely adopted due to its potent cytotoxic, dehydrating, and thrombogenic effects on endometriotic cyst walls, as well as low affordability (11). First described more than thirty years ago, ethanol sclerotherapy for endometrioma management today is commonly performed under ultrasound guidance, offering a minimally invasive approach that may reduce damage to ovarian reserve compared with conventional cystectomy (12–14).

Ethanol sclerotherapy has been applied both as primary management and as treatment for recurrent endometriomas. Its feasibility in outpatient or day-surgery settings, combined with relatively low complication rates, makes it particularly attractive. Yet, uncertainties remain regarding optimal technique, durability of results, and long-term reproductive outcomes (15).

This mini-review summarizes clinical evidence on ethanol sclerotherapy, focusing on safety, efficacy, impact on ovarian reserve, and fertility outcomes. In doing so, it highlights the potential of this approach as a fertility-preserving alternative to cystectomy and identifies key gaps requiring further investigation.

2 Mechanism and procedure

Ethanol sclerotherapy involves aspiration of endometrioma contents followed by flushing with normal saline solution, and instillation of ethanol into the cyst cavity under ultrasound guidance, most commonly transvaginally. Ethanol acts by denaturing proteins, dehydrating epithelial cells, and inducing coagulative necrosis of the cyst wall. Vascular thrombosis within the cyst lining further contributes to ablation of the endometriotic tissue (11). In line with interventional radiology experience, the total ethanol dose is commonly limited to approximately 1 mL/kg, as doses in this range have been associated with systemic blood alcohol concentrations up to about 0.07% and a potential risk of intoxication (11).

For sclerotherapy, ethanol is typically used in high-concentration, parenteral-grade formulations. Commercial products, such as Dehydrated Alcohol Injection, USP and Dehydrated Alcohol for Injection BP, are sterile, non-denatured ethanol solutions containing ≥98%–100% ethanol by volume, supplied as preservative-free single-dose ampules or vials (usually 1–5 mL) intended for injection (16). In ovarian endometrioma sclerotherapy, published protocols most commonly employ 95%–96% or 99% ethanol, with the instilled volume defined as a fraction of the aspirated cyst volume, sometimes with an absolute upper cap, rather than on a per-kilogram body-weight basis. Only sterile, non-denatured preparations specifically formulated for parenteral use should be used; laboratory-grade or industrial “absolute ethanol” is unsuitable. The use of denatured alcohol is contraindicated because it contains toxic additives such as methanol and other denaturants that are unsafe for parenteral administration. When lower concentrations are desired, some protocols have described ethanol diluted to 50%–70% under aseptic conditions by hospital pharmacy. These considerations outline the characteristics of parenteral ethanol preparations used in clinical practice for this off-label procedure.

The technical aspects of endometrioma ethanol sclerotherapy vary widely across published studies. Ethanol concentrations range from 20% to 100%, though most protocols use 95%–100% (17–20). The instilled volume typically corresponds to 20%–100% of the aspirated cyst volume, not exceeding 60–100 mL to minimize ethanol spillage (17, 19, 20). The duration of ethanol contact varies: some protocols recommend immediate aspiration after irrigation (“wash-out”), while others suggest retention for 5–20 min. Increasing evidence suggests that retention for longer than 10 min results in lower recurrence compared with shorter exposure or wash-out techniques (17, 18).

Procedures are usually performed transvaginally under ultrasound guidance. However, the transabdominal approach (using abdominal ultrasound or laparoscopy) is employed in select cases depending on the endometrioma's location, accessibility, and specific case features. Notably, the laparoscopic approach offers the advantage of direct visualization, enabling immediate cleaning and irrigation of the pelvis in the event of ethanol spillage, thereby minimizing inflammation and adhesions (21).

The transvaginal procedure is typically carried out after cleansing the vagina under sterile conditions. The endometrioma is usually punctured, its content aspirated, and flushed using an echogenic needle ranging from 17 to 20 gauge and 20–25 cm long (18–20, 22). Local analgesia, sedation, or general anesthesia is usually required; some centers have recently reported the feasibility of outpatient settings without anesthesia (23–25).

Overall, ethanol sclerotherapy, especially the transvaginal approach, is a technically straightforward, broadly accessible, and repeatable procedure. However, heterogeneity in technique underscores the need for standardized protocols to optimize safety and effectiveness.

3 Clinical outcomes

3.1 Safety and adverse events

Available evidence consistently indicates that ethanol sclerotherapy is a safe treatment. Minor adverse events (pelvic pain, fever, mild bleeding, ethanol leakage) occur in about 10% of cases, while major complications (abscess formation, ethanol intoxication) are reported in fewer than 2% (18, 22, 26). To reduce major complications, specifically intoxication, intra-procedural ethanol loss should be meticulously evaluated, and test blood alcohol levels if leakage is suspected. Endometriomas larger than 80 mm should be managed in specialized centers (27). While prophylactic antibiotics are advised in these cases, they do not appear to prevent infectious complications (27). Overall, compared to cystectomy, complication rates are at least comparable, with the advantage of avoiding surgical risks such as inadvertent ovarian tissue removal or adhesion formation.

In the 8-year single-center experience by Miquel et al. involving 126 women, ethanol sclerotherapy was associated with an overall complication rate of 9.5%, including mild pelvic pain (6%) and transient fever (2%), with one case of ethanol intoxication reported leading to coma (27). In this case, the maximum blood alcohol level was 2.38 g/L and the ethanol loss was 30 mL. Kim et al. pooled 21 studies that employed ethanol and found a major complication rate of 1.7%, primarily abscess formation (18). Frankowska et al. observed only isolated transient pain events in their review of 16 studies, confirming a high safety profile (22). In contrast, García-García et al. reported ethanol leakage in 3.1% of procedures, yet without systemic toxicity (26). Collectively, these data confirm that ethanol sclerotherapy is a low-risk intervention when performed with ultrasound guidance and careful monitoring of ethanol loss.

3.2 Technical efficacy

Across published systematic reviews, ethanol sclerotherapy demonstrates high technical success rates, typically ranging from 95% to 98% (18, 19). The high success rate reflects the ability to aspirate, perform adequate saline flushing, and successfully instill ethanol without procedural failure. Success is largely influenced by factors such as cyst accessibility, operator skill, and the duration of ethanol exposure. However, in a recent comprehensive single-center retrospective cohort study involving 126 women and 131 procedures, the reported failure rate was approximately 10% (27). The main reasons for failure were saline solution leakage, indicating endometrioma rupture during flushing, interpositions of the digestive tract, and thick endometrioma content that could not be adequately aspirated.

3.3 Pain relief

Overall, sclerotherapy has been shown to improve endometriosis-associated pain; however, the success rate has not been consistently reported across systematic reviews (17, 18, 20, 22). In recent single-center retrospective low-scale studies, significant improvement in dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain was reported within 6–12 months following the procedure (28, 29). In the meta-analysis by Kim et al, the pooled pain-relief rate was 85.9% (95% CI 73.9%–92.9%, I2 = 48%), similar to cystectomy but achieved through a minimally invasive approach (18). Long-term follow-up data remain limited beyond one year. While cystectomy also provides effective pain relief, ethanol sclerotherapy offers a less invasive alternative with potentially minimal tissue damage (22).

3.4 Recurrence

Recurrence remains the main limitation of conservative approaches. Rates after ethanol sclerotherapy vary widely, from 10% to 60% depending on follow-up duration and technique (17, 22). In the systematic review by Kim et al., a pooled estimate of 13.8% (9.4%–19.9%; I2 = 75%) was found (18). Retention of ethanol for more than 10 min significantly reduces recurrence compared to shorter exposure or irrigation techniques (17, 18). While recurrence rates may be slightly higher than after cystectomy, repeated sclerotherapy is feasible and does not seem to entail cumulative surgical trauma (30).

3.5 Ovarian reserve

Preservation of ovarian reserve is arguably the primary benefit of ethanol sclerotherapy over surgical excision. Whereas cystectomy consistently leads to a substantial reduction in serum AMH levels, estimated at 40%–60% after one year, with greater losses after bilateral procedures (8, 31), two systematic reviews indicate that ethanol sclerotherapy does not significantly alter AMH levels (18, 22). A recent systematic review further confirmed that sclerotherapy maintains ovarian reserve more effectively than endometriotic cystectomy, as reflected by a smaller decline in AMH (32).

In a recent single-center retrospective comparison study (n = 70), laparoscopic endometriotic cystectomy caused a significant reduction in AMH levels after 12 months (2.48 ± 1.34 vs. 1.62 ± 1.22; P < 0.001), whereas ethanol sclerotherapy did not impact serum AMH levels (2.12 ± 1.05 vs. 2.09 ± 1.01; P = 0.120) (33). In the systematic review by Kim et al., no significant overall change in AMH was observed, with a mean difference of −0.01 ng/mL (−0.04–0.03, P = 0.95, I2 = 0%) (18). Lavadia et al. demonstrated a significantly greater decline in AMH after endometriotic cystectomy compared to sclerotherapy, with a mean difference of 1.69 ng/mL (95% CI 0.58–2.80, P = 0.003, I2 = 94%) (32). These consistent findings seem to highlight the ovarian-reserve–sparing benefit of ethanol exposure compared to endometriotic cystectomy.

Several reviews have also reported improved AFC following sclerotherapy, possibly reflecting decompression of the ovary once the cyst decreases considerably in size (17, 22, 34, 35). However, this should be interpreted with caution, as AFC is a less sensitive measure of ovarian reserve than AMH in cases with endometrioma before surgical management (36).

A theoretical concern is that ethanol might diffuse through the cyst wall into the adjacent ovarian cortex, potentially exposing primordial follicles. Experimental animal studies using rat models, which investigate the injection of ethanol into simple ovarian cysts, reveal stromal fibrosis and follicular loss (37, 38). However, there is no experimental model that measures ethanol diffusion from an endometrioma cavity into ovarian tissue, and the depth of ethanol penetration remains unknown. Nevertheless, prolonged ethanol exposure has been linked to greater tissue injury in animal models, and clinical series highlight that minimizing dwell time, ensuring complete re-aspiration, avoiding leakage, and carefully monitoring ethanol loss appear to mitigate the risk of diffusion-related damage to ovarian reserve.

Collectively, although current evidence suggests that ethanol sclerotherapy is less damaging to ovarian reserve than endometriotic excision, long-term data are still lacking. Furthermore, there is a lack of robust data on how ethanol concentration and sclerosing duration impact ovarian reserve measures.

3.6 Reproductive outcomes

Pregnancy outcomes following ethanol sclerotherapy appear promising, although evidence is heterogeneous and based mainly on small observational studies. Reported overall pregnancy rates range from 30% to 40%, with no definitive difference between spontaneous and assisted conceptions (17–19, 22, 39). In cases of assisted reproduction, sclerotherapy yields similar numbers of retrieved oocytes and clinical pregnancy rates compared to no intervention (17, 22, 39).

Notably, Cohen et al. observed a higher average oocyte yield with sclerotherapy compared to endometriotic cystectomy with a standardized mean difference of 2.71 (95% CI 0.98–4.44, P = 0.03, I2 = 70%) (17). Similar findings were reported in a recent meta-analysis by Lavadia, which showed higher clinical pregnancy rates after ethanol treatment (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.24–2.60, P = 0.01, I2 = 50%) with comparable live birth outcomes (32). These results suggest that sclerotherapy preserves ovarian responsiveness without impairing implantation potential. However, evidence on live birth rates remains limited, primarily derived from small, observational studies. Conversely, He et al. found a non-significant difference in overall pregnancy rates (OR, 1.67; 95% CI 0.74–3.75; P = 0.22, I2 = 34%), underscoring the need for standardized protocols for ethanol sclerotherapy (19).

4 Comparison with endometriotic cystectomy

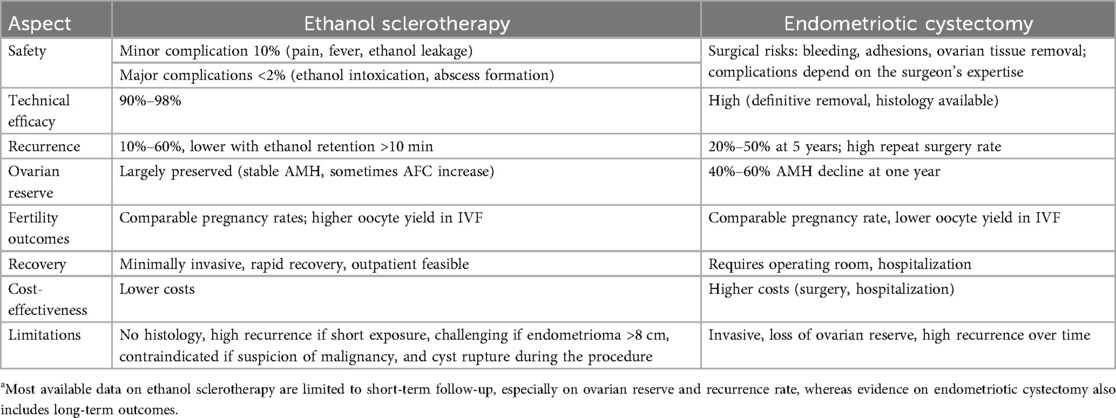

Cystectomy has long been considered the standard treatment for endometriomas, as it allows for the tentative removal of the cyst and provides histological confirmation. However, it carries risks such as loss of ovarian reserve, surgical complications, and recurrence rates that can approach 50% after five years (40, 41). Table 1 summarizes the main points of comparison between the two approaches. Ethanol sclerotherapy offers advantages in several areas, including lower complication rates that are comparable to surgery. Its technical success is high, although recurrence tends to be greater unless ethanol is retained (17, 18, 20). Most notably, ethanol sclerotherapy generally preserves ovarian reserve, unlike cystectomy, which is associated with a decline (22, 31). Additionally, fertility outcomes appear similar, with some evidence of higher oocyte yields and improved clinical pregnancy rates during IVF cycles (32, 40). Furthermore, small-scale studies suggest that sclerotherapy may be more cost-effective, as it could reduce hospitalization and overall expenses (23, 24). Nonetheless, cystectomy remains necessary in cases of suspected malignancy, large symptomatic cysts, or when histological confirmation is required. Therefore, ethanol sclerotherapy should not be viewed as a universal replacement for endometriotic cystectomy but rather as a feasible and viable fertility-preserving option for women of reproductive age, especially those with infertility or planning a future pregnancy.

5 Future directions and research gaps

Despite encouraging outcomes, ethanol sclerotherapy remains underutilized in the management of ovarian endometriomas, largely due to the paucity of high-quality evidence and the heterogeneity of existing studies. Several important questions require clarification and study before this technique can be more widely adopted. Table 2 outlines key areas for future research in this field.

A central issue is that available data combine cases of primary (unoperated endometrioma) and secondary (endometrioma recurrence) ethanol sclerotherapy, which causes bias, complicates the proper assessment of the procedure's safety and efficacy, and obscures its optimal position in the therapeutic sequence. Technique optimization also remains unresolved, with variation in ethanol concentration, instilled volume, and exposure duration across studies; identifying standardized parameters is critical for ensuring reproducible outcomes. Patient selection is another key area of uncertainty, as the influence of cyst size, laterality, and the presence of coexisting deep or superficial endometriosis on efficacy and safety has not been systematically evaluated. Furthermore, while short- and medium-term outcomes are encouraging, evidence on long-term efficacy one year and beyond is scarce, particularly with respect to recurrence and sustained reproductive performance. Similarly, attention should be focused on the impact of ethanol sclerotherapy on ovarian reserve measures over time, employing serum AMH, the most sensitive biomarker in this setting (36).

Furthermore, fertility endpoints reported to date are mostly limited to pregnancy and clinical pregnancy rates, whereas live birth, the most meaningful outcome for affected women, remains insufficiently studied. Finally, the outpatient feasibility of sclerotherapy, which may avoid general anesthesia and reduce hospitalization, raises the possibility of substantial health economic advantages; however, formal cost-effectiveness analyses are lacking. Addressing these gaps through well-designed randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies is essential to establish the precise role of ethanol sclerotherapy in endometrioma management and as a fertility-preserving alternative, and to position it appropriately alongside cystectomy and expectant management within individualized, multidisciplinary fertility-oriented care.

6 Conclusion

Ethanol sclerotherapy represents a safe, technically effective, and fertility-preserving alternative for managing ovarian endometriomas in reproductive-age women. It provides effective symptom relief, reduces recurrence when optimized, and crucially avoids the significant loss of ovarian reserve associated with cystectomy. Reproductive outcomes appear at least comparable, with a potential advantage in ovarian response during IVF.

However, the strength of evidence remains low, and uncertainties persist regarding long-term efficacy and the optimal technique. Ethanol sclerotherapy is best considered a complementary tool within individualized care, particularly for women prioritizing fertility preservation or those at risk from repeated surgeries. Future well-designed trials are needed to define its role more precisely and establish standardized protocols.

Author contributions

JY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Jenkins S, Olive DL, Haney AF. Endometriosis: pathogenetic implications of the anatomic distribution. Obstet. Gynecol. (1986) 67:335–8. 3945444

2. de Ziegler D, Borghese B, Chapron C. Endometriosis and infertility: pathophysiology and management. Lancet. (2010) 376:730–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60490-4

3. Chapron C, Marcellin L, Borghese B, Santulli P. Rethinking mechanisms, diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2019) 15:666–82. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0245-z

4. Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1244–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1810764

5. Guerriero S, Van Calster B, Somigliana E, Ajossa S, Froyman W, De Cock B, et al. Age-related differences in the sonographic characteristics of endometriomas. Hum Reprod. (2016) 31:1723–31. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew113

6. García-Velasco JA, Somigliana E. Management of endometriomas in women requiring IVF: to touch or not to touch. Hum Reprod. (2009) 24:496–501. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den398

7. Tao X, Chen L, Ge S, Cai L. Weigh the pros and cons to ovarian reserve before stripping ovarian endometriomas prior to IVF/ICSI: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0177426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177426

8. Raffi F, Metwally M, Amer S. The impact of excision of ovarian endometrioma on ovarian reserve: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2012) 97:3146–54. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1558

9. Thombre Kulkarni M, Shafrir A, Farland LV, Terry KL, Whitcomb BW, Eliassen AH, et al. Association between laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis and risk of early natural menopause. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e2144391. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.44391

10. Younis JS, Taylor HS. The impact of ovarian endometrioma and endometriotic cystectomy on anti-müllerian hormone, and antral follicle count: a contemporary critical appraisal of systematic reviews. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2024) 15:1397279. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1397279

11. Albanese G, Kondo KL. Pharmacology of sclerotherapy. Semin Intervent Radiol. (2010) 27:391–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267848

12. Noma J, Yoshida N. Efficacy of ethanol sclerotherapy for ovarian endometriomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2001) 72:35–9. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(00)00307-6

13. Koike T, Minakami H, Motoyama M, Ogawa S, Fujiwara H, Sato I. Reproductive performance after ultrasound-guided transvaginal ethanol sclerotherapy for ovarian endometriotic cysts. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2002) 105:39. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(02)00144-6

14. Yazbeck C, Madelenat P, Ayel JP, Jacquesson L, Bontoux LM, Solal P, et al. Ethanol sclerotherapy: a treatment option for ovarian endometriomas before ovarian stimulation. Reprod Biomed Online. (2009) 19:121–5. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60055-7

15. Younis JS. Ethanol sclerotherapy for endometrioma management: what is the level of evidence? Reprod Biomed Online. (2025) 51:105181. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2025.105181

16. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Dehydrated Alcohol Injection, USP: Prescribing Information. DailyMed. Revised March 2025. Available online at: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/ (Accessed November 10, 2025).

17. Cohen A, Almog B, Tulandi T. Sclerotherapy in the management of ovarian endometrioma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. (2017) 108:117–124.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.015

18. Kim GH, Kim PH, Shin JH, Nam IC, Chu HH, Ko HK. Ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy for the treatment of ovarian endometrioma: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. (2022) 32:1726–37. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-08270-5

19. He Y, Wang D, Deng Y. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy versus cystectomy for the treatment of ovarian endometriomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Women’s Health Review. (2024) 20:e280323215050. doi: 10.2174/1573404820666230328121709

20. Ronsini C, Iavarone I, Braca E, Vastarella MG, De Franciscis P, Torella M. The efficiency of sclerotherapy for the management of endometrioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical and fertility outcomes. Medicina (Kaunas). (2023) 59:1643. doi: 10.3390/medicina59091643

21. Şükür YE, Aslan B, Kaplan NB. Transvaginal ultrasound guided versus laparoscopic ethanol sclerotherapy: techniques, tips & tricks. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2025) 32:581–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2025.03.015

22. Frankowska K, Dymanowska-Dyjak I, Abramiuk M, Polak G. The efficacy and safety of transvaginal ethanol sclerotherapy in the treatment of endometrial cysts—a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:1337. doi: 10.3390/ijms25021337

23. Garcia-Tejedor A, Martinez-Garcia JM, Candas B, Suarez E, Mañalich L, Gomez M, et al. Ethanol sclerotherapy versus laparoscopic surgery for endometrioma treatment: a prospective, multicenter, cohort pilot study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2020) 27:1133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.08.036

24. Koo JH, Lee I, Han K, Seo SK, Kim MD, Lee JK, et al. Comparison of the therapeutic efficacy and ovarian reserve between catheter-directed sclerotherapy and surgical excision for ovarian endometrioma. Eur Radiol. (2021) 31:543–8. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07111-1

25. Miquel L, Preaubert L, Gnisci A, Netter A, Courbiere B, Agostini A, et al. Transvaginal ethanol sclerotherapy for an endometrioma in 10 steps. Fertil Steril. (2021) 115:259–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.08.1422

26. García-García I, Alcázar JL, Rodriguez I, Pascual MA, Garcia-Tejedor A, Guerriero S. Recurrence rate and morbidity after ultrasound-guided transvaginal aspiration of ultrasound benign-appearing adnexal cystic masses with and without sclerotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2022) 29:204–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2021.09.708

27. Miquel L, Liotta J, Pivano A, Gnisci A, Netter A, Courbiere B, et al. Ethanol endometrioma sclerotherapy: safety through 8 years of experience. Hum Reprod. (2024) 39:733–41. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deae014

28. Lee J-K, Ahn S-H, Kim H-I, Lee Y-J, Kim S, Han K, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of catheter-directed ethanol sclerotherapy and its impact on ovarian reserve in patients with ovarian endometrioma at risk of decreased ovarian reserve: a preliminary study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2022) 29:317–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2021.08.018

29. Mohtashami S, Jabarpour M, Aleyasin A, Aghahosseini M, Najafian A. Efficacy of ethanol sclerotherapy versus laparoscopic excision in the treatment of ovarian endometrioma. J Obstet Gynaecol India. (2024) 74:60–6. doi: 10.1007/s13224-023-01840-1

30. Zeng CH, Cao CW, Shin JH, Kim GH, Kim SH, Lee SR, et al. Safety and clinical outcomes of two-session catheter-directed sclerotherapy using ethanol for endometrioma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. (2024) 47:901–9. doi: 10.1007/s00270-024-03700-5

31. Younis JS, Shapso N, Fleming R, Ben-Shlomo I, Izhaki I. Impact of unilateral versus bilateral ovarian endometriotic cystectomy on ovarian reserve: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. (2019) 25:375–91. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmy049

32. Lavadia CMM, Jeong HG, Ryu KJ, Park H. Ovarian reserve and IVF outcomes after ethanol ovarian sclerotherapy in women with endometrioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. (2025) 51:104840. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2025.104840

33. Ghasemi Tehrani H, Tavakoli R, Hashemi M, Haghighat S. Ethanol sclerotherapy versus laparoscopic surgery in management of ovarian endometrioma: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Acad Emerg Med. (2022) 10:e55. doi: 10.22037/aaem.v10i1.1636

34. Gonçalves FC, Andres MP, Passman LJ, Gonçalves MO, Podgaec S. A systematic review of ultrasonography-guided transvaginal aspiration of recurrent ovarian endometrioma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2016) 134:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.10.021

35. Ioannidou A, Machairiotis N, Stavros S, Potiris A, Karampitsakos T, Pantelis AG, et al. Comparison of surgical interventions for endometrioma: a systematic review of their efficacy in addressing infertility. Biomedicines. (2024) 12:2930. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12122930

36. Younis JS, Shapso N, Ben-Sira Y, Nelson SM, Izhaki I. Endometrioma surgery—a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect on antral follicle count and anti-müllerian hormone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2022) 226:33–51.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.06.102

37. Atilgan R, Yalcin SE, Ozkan EA, Kafkasli A. Impact of intracystic ethanol instillation on ovarian cyst diameter and adjacent ovarian tissue. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2014) 174:133–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.12.019

38. Şimşek M, Kuloğlu T, Pala Ş, Boztosun A, Can B, Atilgan R. The effect of ethanol sclerotherapy of 5 min duration on cyst diameter and rat ovarian tissue in simple ovarian cysts. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2015) 9:1341–7. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S76835

39. Gao X, Zhang Y, Xu X, Lu S, Yan L. Effects of ovarian endometrioma aspiration on in vitro fertilization-intracytoplasmic sperm injection and embryo transfer outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2022) 306:17–28. doi: 10.1007/s00404-021-06278-2

40. Guo SW. Recurrence of endometriosis and its control. Hum Reprod Update. (2009) 15:441–61. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp007

Keywords: fertility preservation, endometrioma, ethanol sclerotherapy, ovarian reserve, endometriosiis

Citation: Younis JS (2025) Ethanol sclerotherapy for endometriomas: a fertility-preserving alternative. Front. Reprod. Health 7:1716957. doi: 10.3389/frph.2025.1716957

Received: 1 October 2025; Revised: 18 November 2025;

Accepted: 21 November 2025;

Published: 4 December 2025.

Edited by:

Shevach Friedler, Barzilai Medical Center, IsraelReviewed by:

Sujata Kar, Ravenshaw University, IndiaCopyright: © 2025 Younis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Johnny S. Younis, anlvdW5pc0Bwb3JpYS5oZWFsdGguZ292Lmls

Johnny S. Younis

Johnny S. Younis