- 1Aier School of Ophthalmology, Central South University, Changsha, China

- 2Aier Eye Institute, Changsha, China

- 3Key Laboratory for Regenerative Medicine, Ministry of Education, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

- 4Institute of Ophthalmology, Medical College, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

- 5Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

Background: Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a main complication of diabetes mellitus (DM). Recent studies have implicated microRNAs in human retinal microvascular endothelial cell (HRMEC) dysfunction. In this study, we aim to investigate the apoptotic promotion of miR-29b-3p by blocking SIRT1 in HRMEC for DR situation.

Method: Blood samples were obtained from DR patients and controls. Dual-luciferase reporter assay using HEK-293T cells was performed to show the direct interaction of miR-29b-3p and the 3′UTR of SIRT1. HRMECs were exposed to 5.5 mmol/L of glucose (normal control), 5.5 mmol/L of glucose and 24.5 mmol/L of mannitol (osmotic pressure control), 30 mmol/L of glucose [hyperglycemia (HG)], 150 μmol/L of CoCl2 (hypoxia), and 30 mmol/L of glucose plus 150 μmol/L of CoCl2 (HG-CoCl2). To identify the regulating relationship between miR-29b-3p and SIRT1, HRMECs were transfected with miR-29b-3p mimics/inhibitors or their negative controls. SRT1720 was used as a SIRT1 agonist. Cell viability was assessed with the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay, and apoptotic cells were stained by one-step terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit. Gene and protein expression were assayed by quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-qPCR) and western blotting separately.

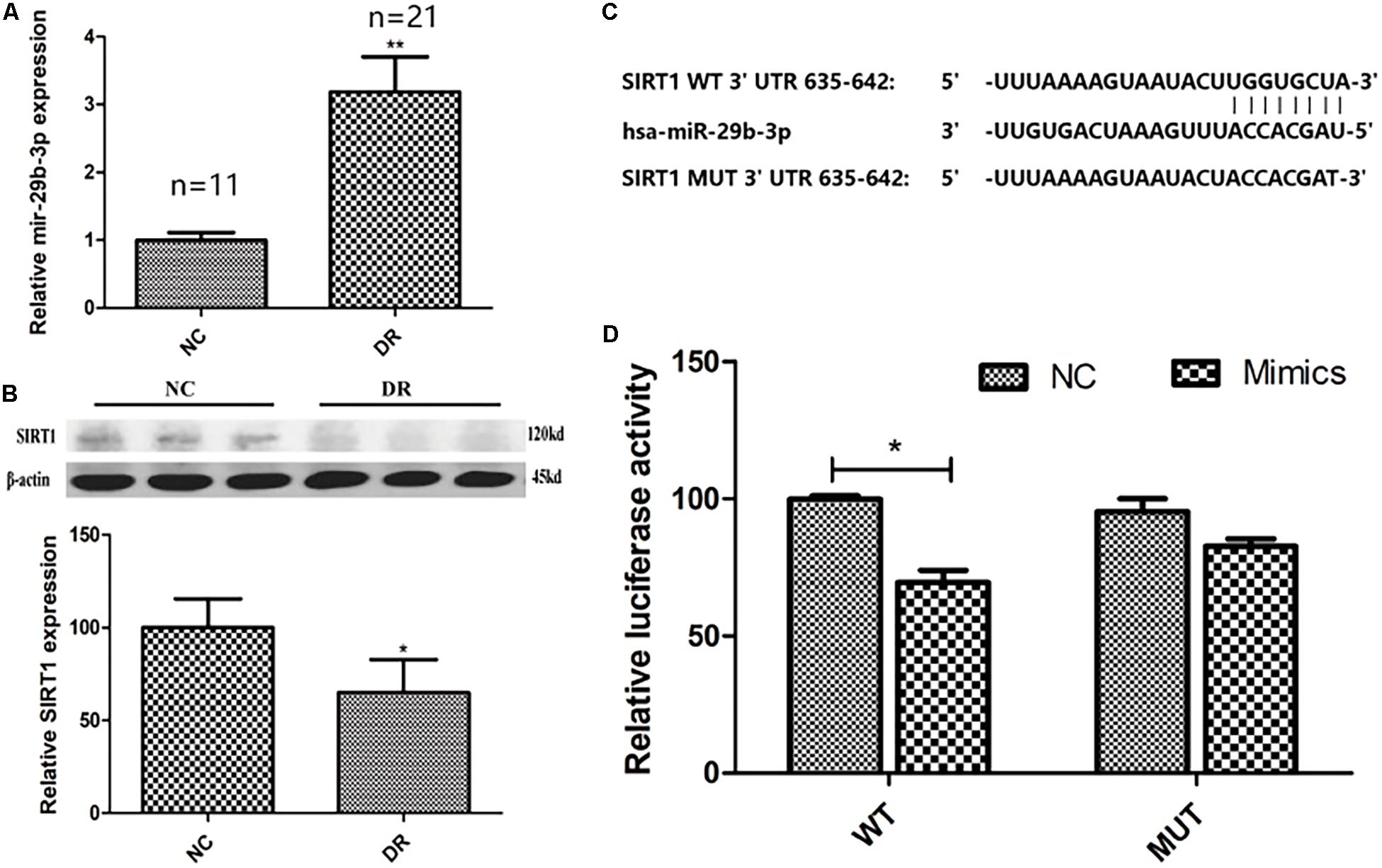

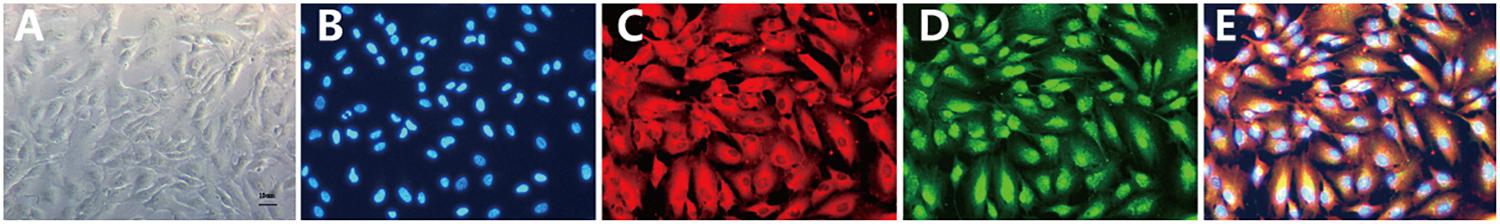

Result: MiR-29b-3p was upregulated to 3.2-fold, and SIRT1 protein was downregulated to 65% in DR patients. Dual-luciferase reporter assay showed the direct interaction of miR-29b-3p and SIRT1. HRMECs were identified as >95% positive for CD31 and von Willebrand factor (vWF). MiR-29b-3p and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio was upregulated, whereas SIRT1 was downregulated in HRMECs in the HG-CoCl2 condition. Decreased cell viability and upregulated apoptosis were also found in HRMECs of the HG-CoCl2 condition. Upregulated miR-29b-3p decreased the expression of SIRT1 and increased the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2, whereas downregulated miR-29b-3p increased the expression of SIRT1 protein and downregulated the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2. SRT1720 rescued miR-29b-3p-induced HRMEC apoptosis via upregulating the expression of SIRT1 protein.

Conclusion: The dysregulation of miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 is a potential mechanism of HRMEC apoptosis in DR. MiR-29b-3p/SIRT1 may be a potential therapeutic target for DR.

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a main complication of diabetes mellitus (DM), and it is a leading cause of blindness in working-aged adults worldwide (Chong et al., 2017). Vascular damage, which may be caused by cell apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and a series of metabolic disorders, is an initial characteristic and will exacerbate DR progression (Kannenkeril et al., 2018; Miloudi et al., 2019). Once the blood–retina barrier is broken down, dangerous factors from the circulating blood will leak into the retinal tissue and cause irreversible damage to the retinal neural cells (Trost et al., 2016; Xu and Chen, 2017). Although a series of studies have been carried out to investigate the pathogenesis of human retinal vascular endothelial cell apoptosis (Santiago et al., 2018; Whitehead et al., 2018), the mechanism is largely unknown.

MicroRNA is a kind of non-coding RNA composed of 19–25 nucleotides (Lu and Rothenberg, 2018). Thousands of microRNAs have been discovered since they were first reported in 1993, and a single kind of microRNA may have hundreds of target mRNAs (O’Kelly et al., 2012; Landrier et al., 2019). MicroRNA regulates post-transcriptional gene expression via binding to target sites directly or promoting mRNA degradation (Landrier et al., 2019). A series of studies have revealed the regulation of microRNA in aging, tumor progression, metabolic diseases, and inflammation (Klieser et al., 2019; Majidinia et al., 2019; Nasr et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019). In recent years, a variety of microRNAs (miR-409-3p, miR-98-5p, miR-16-5p, etc.) have been proved to participate in DM progression and its complications (Duan et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2019; Ventriglia et al., 2019). Furthermore, numerous microRNAs (miR-3197, miR-2116-5p, miR-152, miR-34a, etc.) are identified as specificity biomarkers, and they participate directly in DR progression (Fu and Ou, 2019; Ji et al., 2019; Thounaojam et al., 2019). SIRT1 is a NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase, which plays important roles in metabolic regulation and adaptation (Boutant and Cantó, 2014). Through deacetylation of various transcription factors (p53, p65, STAT3, etc.), SIRT1 widely takes part in the regulation of inflammation, oxidative stress, autophagy, and cell apoptosis (Kitada et al., 2019; Sanz et al., 2019). Researchers believe that SIRT1 is a protective factor in DM and its complications (Potente et al., 2007; Boutant and Cantó, 2014; Collin et al., 2019; Myers et al., 2019). Bax is widely accepted as a pro-apoptosis factor, whereas Bcl-2 is an anti-apoptosis factor; the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 may be more important than either alone in determining apoptosis (Oltvai et al., 1993). SIRT1 is proved to downregulate the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2, thus further attenuating cell apoptosis (Nguyen et al., 2019; Sasaki et al., 2019).

Recent studies have revealed the decrease of SIRT1 in diabetes patients (Balestrieri et al., 2013) and the increase of miR-29b-3p in diabetes (Esteves et al., 2018). Furthermore, Su et al. (2019) have proved the direct regulation of miR-29b-3p to SIRT1 in insulin resistance. To our knowledge, there is no research to illuminate the regulatory relationship of miR-29b-3p/SIRT1/Bax/Bcl-2 pathway in human retinal microvascular endothelial cell (HRMEC). Here, we performed this study to verify the role of miR-29b-3p in DR.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Tissues

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Aier Eye Hospital (Changsha, Hunan, China). This study was approved by the ethics committee of Aier Eye Hospital (AIER2018IRB21) and registered on the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ChiCTR1900025449). Consent was obtained from all the participants before collection. Blood samples were obtained from 21 DR patients aged 37–71 years. Negative control (NC) blood samples came from 11 pterygium patients without DM aged 53–69 years. All the samples were stored at −80°C for further experiments. Human retinas in this study were obtained from organ donors without DM or retinal diseases.

Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

We predicted SIRT1 as a potential target of miR-29b-3p by using miRNA database (TargetScanHuman 7.2). Then the 3′-UTR of human SIRT1 containing the predicted binding sites [wild type (WT)] or mutated binding sites [mutant type (MUT)] was amplified and inserted into pmir-RB-ReportTM vector. The reporter plasmids and miR-29b-3p mimics or NC were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) to determine if SIRT1 is a direct target of miR-29b-3p. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured 48 h after transfection using the Dual-Glo® Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, United States).

Cell Culture and Treatment

Primary HRMECs were isolated according to methods described previously (Fan et al., 2016); briefly, retinas were immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 5% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) for 5 min and then transferred into Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) to remove vitreous. Retinas were then minced into small pieces and digested with type II collagenase (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) at 37°C for 30 min. Cell suspension was filtered through a 70-μm mesh and cultured in endothelial cell medium (ECM; ScienCell, San Diego, CA, United States). Culture medium was replaced every 2–3 days.

To explore the HRMEC damage in DR, we constructed an in vitro model of hyperglycemia and hypoxia conditions. HRMECs were cultured in 5.5 mmol/L of glucose (normal control), 5.5 mmol/L of glucose and 24.5 mmol/L of mannitol (osmotic pressure control), 30 mmol/L of glucose [hyperglycemia (HG)], 150 μmol/L of CoCl2 (hypoxia), 30 mmol/L of glucose, and 150 μmol/L of CoCl2 (HG-CoCl2). Culture medium was refreshed every 24 h. SRT 1720 Hydrochloride (MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, United States) was used as an activator to upregulate the expression of SIRT1.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence to platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1/CD31) and von Willebrand factor (vWF) were used to determine the endothelial cell purity (Gao et al., 2013). Primary antibodies to CD31 (mouse anti-CD31 antibody, ab24590, 1:100, Abcam) and vWF (rabbit polyclonal to vWF antibody, ab6994, 1:100, Abcam) were used to detect CD31 and vWF, respectively. Goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 594) and goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488) were used to detect the primary antibodies separately. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Cells of passages between 3 and 5 and 95% positive for CD31 and vWF were used in this study.

Cell Transfection

Cells were seeded in 6-well and 96-well plates with a density of 2 × 105/well and 4 × 103/well. The miR-29b-3p mimics, inhibitors, and their NCs were purchased from RiboBio (Guangzhou, China) and transfected into cells using riboFECTTM CP Reagent (Guangzhou, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. NC mimics labeled with Cy3 fluorescence (Guangzhou, China) were transfected to observe the transfect efficiency directly. After 30 h of transfection, the HRMECs were collected for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) stain, cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8), quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-qPCR), and Western blot (WB) assay.

Cell Apoptotic and Viability Assay

For apoptosis and viability assay, 4 × 103 cells/well were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified environment. The One Step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit (Beyotime) was used for detecting apoptotic cells. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Fluorescent images were acquired by a fluorescence microscope (ECLIPSE Ts2R, Nikon). The quantification of TUNEL-positive cells was obtained by ImageJ software and calculated by GraphPad Prism version 5.0. Cell viability was determined by a CCK-8 assay (MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, United States). Seven replicates per group and a group without cells served as the blank. After being treated with different conditions, 100 μl of fresh culture medium with 10% CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was observed by SynergyTM HTX Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek Technologies, Winooski, VT, United States). The relative viability of cells was calculated according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase–Polymerase Chain Reactions

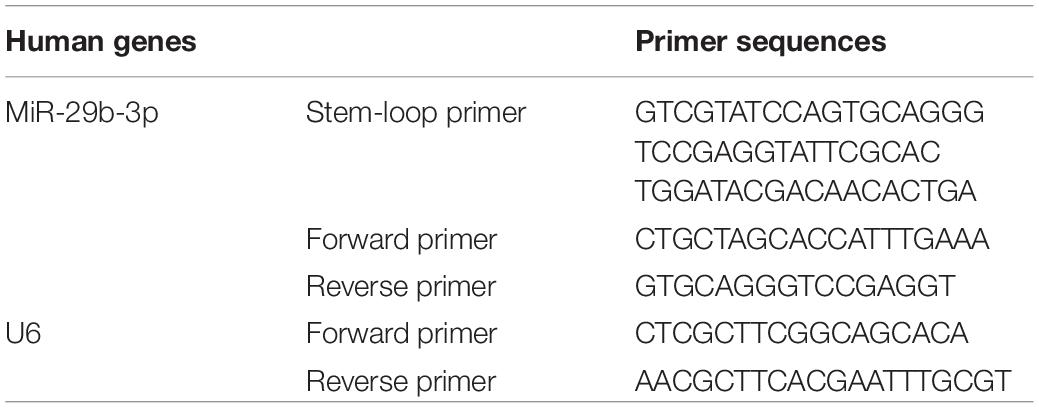

MicroRNA was isolated with a microRNA kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, United States) and reversed to cDNA with a reverse transcription kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland); the stem-loop method was especially used for microRNA reverse transcription as described previously (Chen et al., 2005). The RT product was subjected to 45 cycles of qPCR reactions with ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech, Jiangsu, China) in a Roche LightCycler® 96 System (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). U6 was used to normalize the expression of microRNA. The relative expression level of miRNA was calculated by the 2–Δ Δ CT method. The specific primers for miR-29b-3p and U6 are listed in Table 1.

Western Blots

After being treated with different conditions, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Lysates were then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C to collect the supernatant. Protein quantification was performed using BCA Protein Assay Kit (Solarbio) according to the company’s protocol. The supernatant proteins were concentrated with the method described previously (Zaiss et al., 2013). Briefly, supernatant, methanol, and chloroform were mixed thoroughly. The mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was discarded carefully. Then another volume of methanol was added to the pellet and vortexed to mix thoroughly. The mixture was again centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was discarded. After being air-dried for 5 min, the proteins were dissolved with the lysis buffer from a Caspase 3 Activity Assay Kit (Beyotime), and the quantification was performed using a Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Solarbio).

Protein was denatured using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer (Solarbio) by heating the samples at 98°C for 6 min. Electrophoresis was performed using 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Pall) and blocked with 5% non-fat milk containing Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. IRDye® 800CW goat anti-rabbit/mouse secondary antibody (LI-COR) was used to detect primary antibody binding. The immunoblots were analyzed and quantified using ImageJ software. Antibodies to SIRT1(19A7AB4), Bax (E63), and Bcl-2 (E17) were obtained from Abcam. Caspase-3 and β-actin (8H10D10) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. Total protein stain was performed by using a REVERT Total Protein Stain kit (LI-COR). Relative quantification of cleaved caspase-3 in supernatant was achieved by normalizing each target to the value of total proteins.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software version 19.0 and GraphPad Prism version 5.0 were used for descriptive analysis. The data were shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The results presented in the paper were representative of at least three different repetitions. Student’s t test was performed to assess differences between two means. A chi-square test for qualitative data was applied. One-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test was performed in multiple means comparison. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

SIRT1 Is a Direct Target of MiR-29b-3p in Diabetic Retinopathy

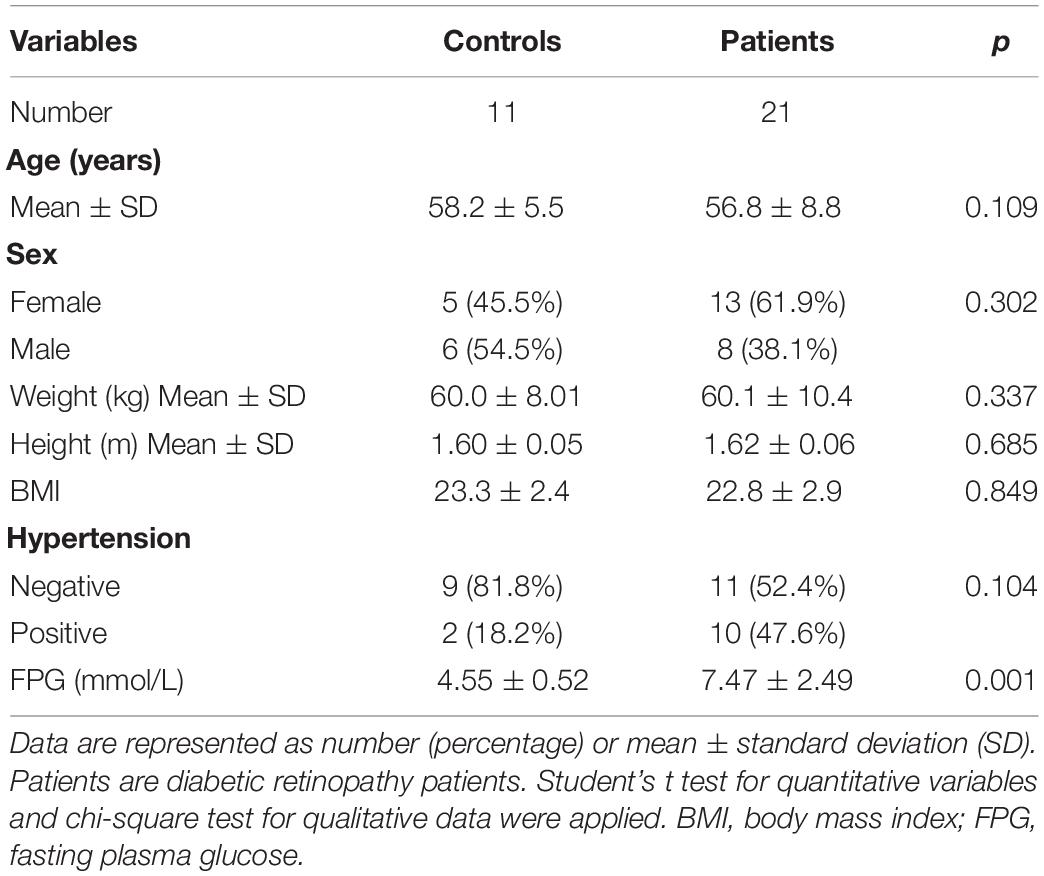

The baseline data of clinical samples are shown in Table 2. To explore the expression pattern of miR-29b-3p and SIRT1 in DR patients, RT-qPCR and WB were performed. MiR-29b-3p RNA was upregulated to 3.2-fold (Figure 1A), and SIRT1 protein was downregulated to 65% (Figure 1B) in DR patients’ blood samples. With the miRNA online database (TargetScanHuman7.2 and miRBase), we found that SIRT1 is a direct target of miR-29b-3p (Figure 1C). Dual-luciferase reporter assay using HEK-293T cells showed the direct interaction of miR-29b-3p and the 3′UTR of SIRT1. After 48-h cotransfection, overexpressed miR-29b-3p reduced the luciferase activity of WT reporter but had no inhibition on the MUT reporter (Figure 1D). The results of this study showed that miR-29b-3p could inhibit the expression of SIRT1 by binding with the 3′-UTR of SIRT1, and SIRT1 might be the downstream target gene of miR-29b-3p.

Figure 1. The clinical expression pattern and dual-luciferase reporter assay of miR-29b-3p and SIRT1. (A) In DR patients’ blood, miR-29b-3p was upregulated to 3.2-fold compared with that of control group. (B) DR patients’ blood SIRT1 protein was downregulated to 65% compared with that of control group. (C) SIRT1 is a direct target of miR-29b-3p predicted by the miRNA online database (TargetScanHuman7.2 and miRBase). (D) Dual-luciferase reporter assay using HEK-293T cells showed the direct interaction of miR-29b-3p and the 3′UTR of SIRT1. After 48-h cotransfection, overexpression of miR-29b-3p reduced the luciferase activity of WT reporter but had no inhibition on the MUT reporter. Data are shown as mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. NC, negative control; DR, diabetic retinopathy; WT, wild type; MUT, mutant type.

Verification of Human Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cell

Human retinal microvascular endothelial cell clusters began to form on the third day after plating. After 10-day culture, the cells showed an oval morphology and a contact-inhibited monolayer (Figures 2A,B). Immunofluorescence was performed to detect CD31 and vWF, which were well-known typical vascular endothelial cell markers. As a result, both CD31 (Figure 2C) and vWF (Figure 2D) were positive on the same cells (Figure 2E). These results verified the cell type and purification.

Figure 2. Culture and verification of HRMEC. (A) After 10-day culture, the cells showed an oval morphology and a contact-inhibited monolayer. (B) Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue fluorescent). (C) CD31 was positive (red fluorescent). (D) vWF was positive (green fluorescent). (E) Merged picture revealed double staining positive for CD31/vWF. The cell morphology and immunofluorescent results verified the HRMEC cell type. HRMEC, human retinal microvascular endothelial cell; CD31, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

Expression of MiR-29b-3p and SIRT1 in Human Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cell Under Hyperglycemia–CoCl2 Condition

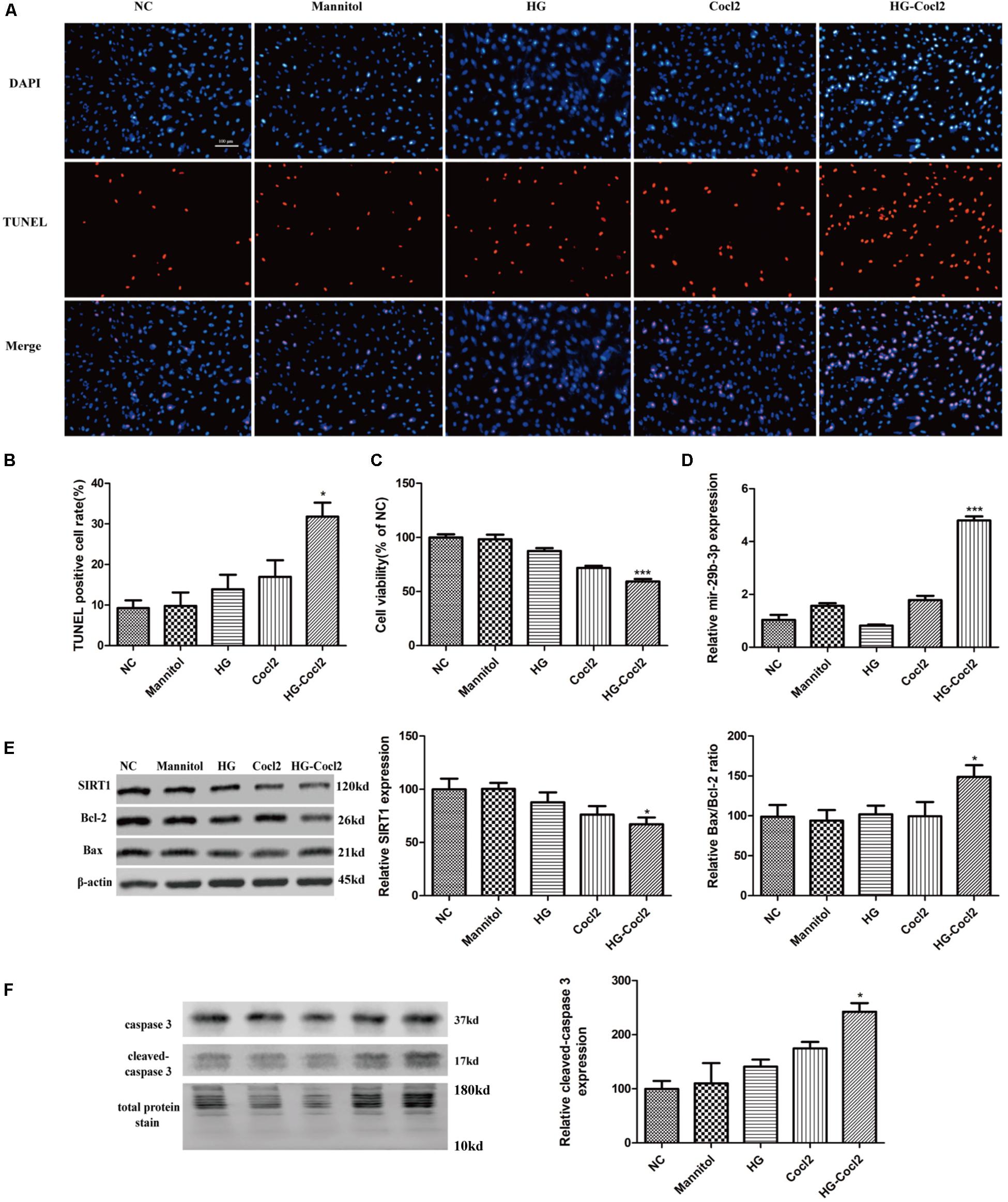

After treatment with the HG-CoCl2 condition and different controls, obvious apoptosis was observed by TUNEL assay (Figures 3A,B), and cell viability was decreased compared with that of controls (Figure 3C). MiR-29b-3p was upregulated (Figure 3D) in the HG-CoCl2 condition, whereas SIRT1 protein was downregulated (Figure 3E). HG-CoCl2 upregulated Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and the expression of cleaved caspase-3 significantly (Figures 3E,F).

Figure 3. Cell apoptosis and expression pattern of miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 in HRMEC under HG-CoCl2 condition. (A) Obvious apoptotic cells were observed in HG-CoCl2 condition. (B) Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells. (C) Cell viability was decreased by HG-CoCl2 condition compared with that of different controls. (D) MiR-29b-3p was upregulated significantly in HG-CoCl2 condition. (E) SIRT1 protein was downregulated and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio was upregulated. (F) Relative expression of cleaved caspase-3 was upregulated by HG-CoCl2 treatment. Data are shown as mean ± SD, *p < 0.05 versus the NC group and ***p < 0.001 versus the NC group. NC, negative control; HG, high glucose; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling.

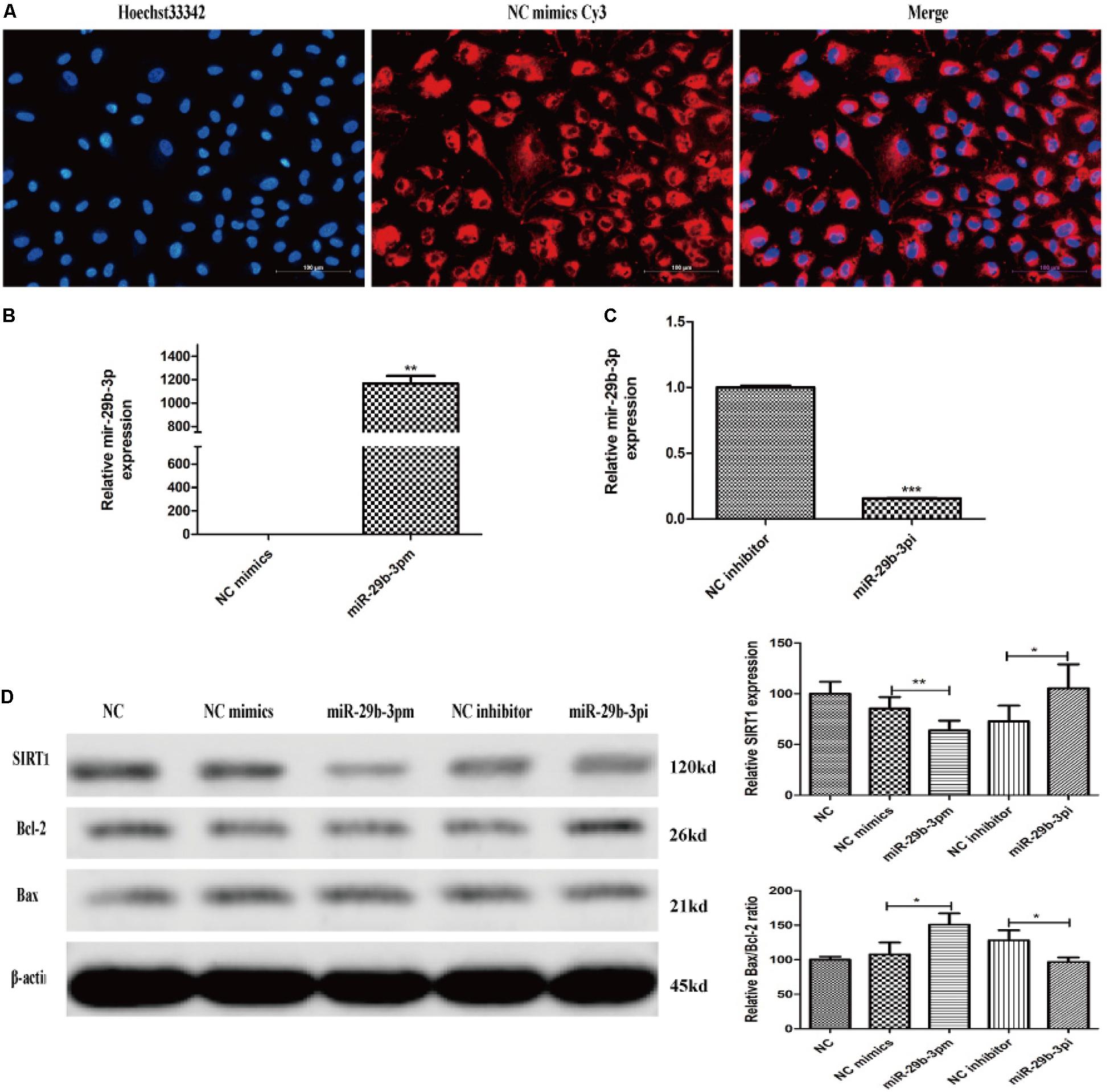

MiR-29b-3p Inhibits SIRT1 in Human Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cell

After 30-h transfection, annulus red fluorescence was observed around the nucleus (Figure 4A). HRMECs were transfected with miR-29b-3p mimics (miR-29b-3pm), inhibitors (miR-29b-3pi), and their NCs. RT-qPCR and WB were performed to verify the transfection effect. The mRNA expression level of miR-29b-3p in miR-29b-3pm was elevated (Figure 4B), whereas miR-29b-3pi decreased the expression of miR-29b-3p obviously (Figure 4C). Relative SIRT1 protein expression was downregulated and the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 was upregulated in miR-29b-3pm to NC, whereas relative SIRT1 protein expression was upregulated and the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 was downregulated in miR-29b-3pi to NC (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. MiR-29b-3p mimics, inhibitors, and their negative controls were transfected into HRMEC successfully. (A) Annulus red fluorescence was observed around the nucleus after 30-h transfection with NC mimics Cy3. (B) The mRNA expression level of miR-29b-3p in miR-29b-3pm transfection was elevated significantly. (C) The mRNA expression level of miR-29b-3p was decreased in miR-29b-3pi transfection. (D) Relative SIRT1 protein expression was downregulated and the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 was upregulated in miR-29b-3pm to negative control. In miR-29b-3pi, relative SIRT1 protein expression was upregulated and the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 was downregulated versus that of negative control. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. NC, negative control; miR-29b-3pm, miR-29b-3p mimics; miR-29b-3pi, miR-29b-3p inhibitor.

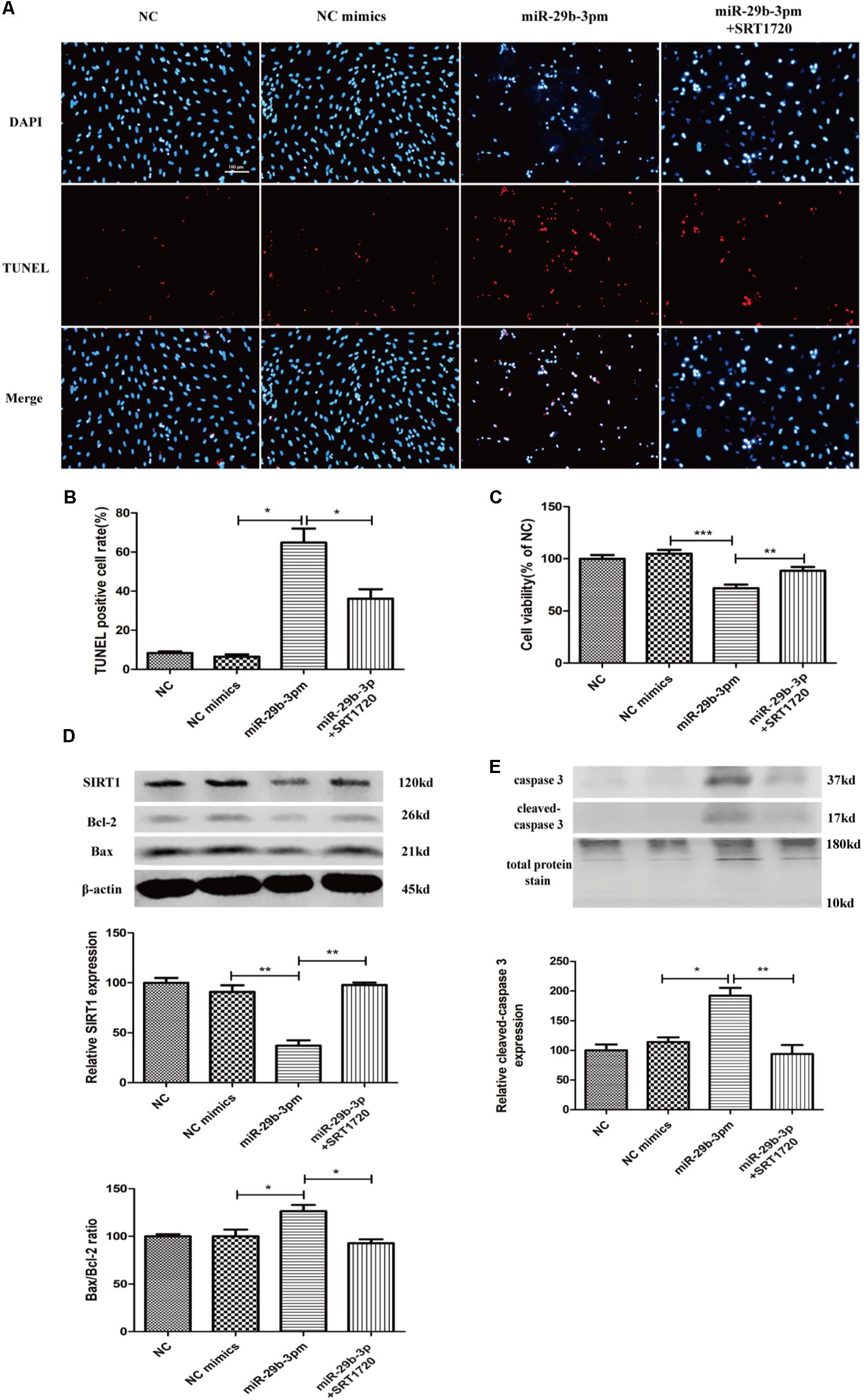

MiR-29b-3p Promotes Human Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cell Apoptosis via Blocking SIRT1

MiR-29b-3p mimics were transfected into HRMEC with or without SRT1720. Upregulated miR-29b-3p increased apoptosis (Figures 5A,B) and decreased cell viability in HRMEC (Figure 5C), whereas apoptosis was decreased (Figures 5A,B) and cell viability was upregulated after the treatment of SRT1720 (Figure 5C). Relative SIRT1 protein expression was decreased and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and cleaved caspase-3 were upregulated after the transfection of miR-29b-3p, whereas after the treatment of SRT1720, relative SIRT1 protein expression was upregulated and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and cleaved caspase-3 were downregulated (Figures 5D,E).

Figure 5. MiR-29b-3p promotes HRMEC apoptosis via blocking SIRT1. (A) Upregulated miR-29b-3p promoted apoptosis, whereas SRT1720 alleviated the apoptosis promotion of miR-29b-3p. (B) Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells. (C) Cell viability was downregulated by miR-29b-3pm and upregulated after the treatment of SRT1720. (D) Relative SIRT1 protein expression was decreased and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio was upregulated after the transfection of miR-29b-3pm, whereas after the treatment of SRT1720, relative SIRT1 protein expression was upregulated and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio was downregulated. (E) Relative cleaved caspase-3 protein expression was upregulated after the transfection of miR-29b-3pm and downregulated after the treatment of SRT1720. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. NC, negative control; miR-29b-3pm, miR-29b-3p mimics; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling.

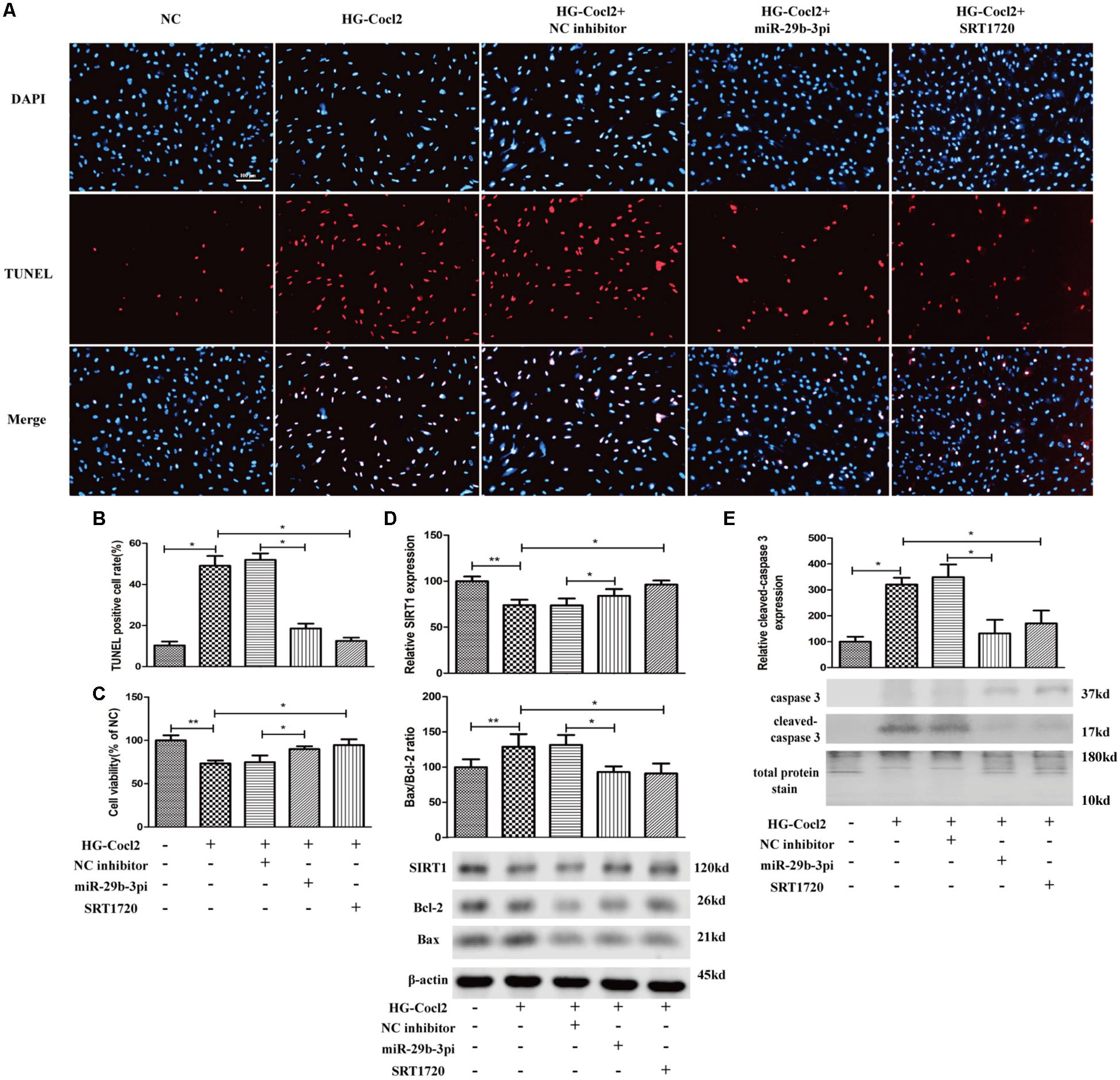

MiR-29b-3pi and SRT1720 Alleviate Hyperglycemia–CoCl2-Induced Human Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cell Apoptosis

MiR-29b-3pi and SRT1720 effectively alleviated HRMEC apoptosis induced by HG-CoCl2 (Figures 6A,B) and improved cell viability (Figure 6C). Relative SIRT1 protein expression was increased and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio (Figure 6D) and cleaved caspase-3 were also downregulated obviously by miR-29b-3pi and SRT1720 (Figure 6E).

Figure 6. MiR-29b-3p inhibitor and SRT1720 alleviate HG-CoCl2-induced HRMEC apoptosis. (A) Cell apoptosis was induced by HG-CoCl2 obviously, whereas miR-29b-3pi and SRT1720 alleviated the apoptosis significantly. (B) Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells. (C) MiR-29b-3pi and SRT1720 promoted cell viability in HG-CoCl2 condition. (D) MiR-29b-3pi and SRT1720 increased the expression of SIRT1 protein and downregulated Bax/Bcl-2 ratio in HG-CoCl2 condition. (E) Relative expression of cleaved caspase-3 was downregulated by miR-29b-3pi and SRT1720. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. NC, negative control; HG-CoCl2, high glucose and CoCl2; miR-29b-3pi, miR-29b-3p inhibitor; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling.

Discussion

Diabetic retinopathy is a serious complication of DM, which may cause irreversible vision loss or even blindness. Microvascular damage is a typical worsening characteristic as DM progresses (Stehouwer, 2018). However, the mechanism of microvascular damage in DR is complicated and should be further studied. In this study, we illuminated the dysregulation of miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 in DR patient blood samples. Additionally, using cultured HRMEC apoptotic model induced by HG-CoCl2, we proved that miR-29b-3p promoted HRMEC apoptosis. These findings indicate that miR-29b-3p may be an important regulator in vascular damage in DR progression.

Hyperglycemia and hypoxia are the leading causes of diabetic vascular injury via enhanced oxidative stress, nitrosative stress, and advanced glycation, thus promoting inflammation (Miyata and de Strihou, 2010; Chiu and Taylor, 2011). The experimental model of hyperglycemia and hypoxia conditions is widely used in the research of diabetic complications (Bakhashab et al., 2014, 2016). In this study, we constructed an in vitro hyperglycemia and hypoxia model with HRMEC to investigate the diabetic vascular damage mechanism. This model revealed similar apoptotic promotion as the study from Bakhashab et al. (2018) on human umbilical vein endothelial cells.

Previous studies revealed that dysregulation of miR-29 family promoted cell apoptosis in many human diseases including cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and myocarditis (Chen et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). Yuan et al. (2018) found that miR-29b would activate NF-κB, thus aggravating endothelial cell inflammatory damage. Overexpression of miR-29b increased the expression of cleaved caspase-3, which is a typical apoptotic factor (Yuan et al., 2018). Saravanan et al. (2019) reported that miR-29b-3p was selectively released in exosomes from inflammation and hypoxia induced islets before apoptosis and cell death, which coincided with activation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response markers IRE-1α, XBP1, HIF-1α, and CHOP. They also detected the selective release of miR-29b-3p in plasma exosomes after these cells were transplanted into streptozotocin (STZ) diabetic nude mice. Therefore, miR-29b-3p might be an early indicator of human islet cell apoptosis during prediabetic conditions (Saravanan et al., 2019). MiR-29b-3p was obviously upregulated in high glucose-induced endothelial cells (Silambarasan et al., 2016), and overexpression of miR-29b-3p could cause insulin resistance in mice (Su et al., 2019). These findings indicate that miR-29b-3p may be involved in vascular damage and DM progression. Our findings in clinical samples and HG-CoCl2-induced HRMEC are consistent with these studies.

SIRT1 was proved to alleviate inflammation and apoptosis via deacetylating inflammatory transcription factors; therefore, SIRT1 was gradually coming to be interpreted as a DR protector (Mishra et al., 2018), whereas in DM patients and especially in patients with poor glycemic control, SIRT1 was significantly downregulated (Balestrieri et al., 2013). We also verified this and found that SIRT1 protein was downregulated in DR blood samples. Furthermore, we revealed the tendency that SIRT1 was decreased in DR patients’ plasma using the ELISA method (Supplementary Figure 1). Mariani et al. (2015, 2016) and Khalyfa et al. (2019) reported that SIRT1 was downregulated in DM-associated metabolic diseases plasma and the decreased exosome SIRT1 might be correlated with endothelial dysfunction. However, the regulatory mechanism of diabetes to SIRT1 is not clear. Recent studies revealed that the microRNA might be an indispensable regulator (Yamakuchi and Hashiguchi, 2018). Thounaojam et al. (2019) found that overexpression of miR-34a could decrease the expression of SIRT1 directly and induce mitochondrial dysfunction in high glucose-induced retinal endothelial cells. Thus, miR-155-5p, miR-106b, etc. were successively identified to target SIRT1 directly in diabetes conditions (Chen and Yang, 2017; Jiao et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). We predicted that SIRT1 was a direct target of miR-29b-3p by the miRNA online database (TargetScanHuman7.2 and miRBase). We also found the different expression patterns of miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 in DR patient and control blood samples. However, the regulatory mechanism of miR-29b-3p to SIRT1 in DR is still unknown. Our in vitro research displayed that overexpression of miR-29b-3p in HRMEC downregulated SIRT1 protein expression and promoted cell apoptosis and that the apoptotic promotion of upregulated miR-29b-3p could be rescued by a SIRT1 specific agonist SRT1720. Furthermore, we verified that both miR-29b-3p inhibitor and SRT1720 could increase SIRT1 protein expression and alleviate cell apoptosis in HG-CoCl2-induced HRMEC. Therefore, we suggest that SIRT1 is a direct target of miR-29b-3p in DR patients’ retinal microvascular endothelial cells.

In summary, in this study, we investigated the different expression of miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 in blood samples from DR patients and controls. We found that miR-29b-3p was upregulated and SIRT1 was downregulated in DR blood samples. We further explored the interaction mechanism of miR-29b-3p and SIRT1 in cultured HRMEC apoptotic model induced by HG-CoCl2. To the best of our knowledge, the relevant reports on the mechanism of miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 in diabetic HRMEC have not yet found. Our study illuminated this mechanism preliminarily. Our data provided the proof that miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 may be a potential therapeutic target for DR. However, DR is a very complicated disease that may be affected by aging, diabetes duration, smoking, etc. (Varma et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2019). We need more clinical samples to verify our findings especially the vitreous or retinal tissues from DR patient surgeries. We need more in vitro research on the apoptotic regulation mechanism of miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 via deacetylation method, as epigenetics plays an important role in DM and its complications (Menzies et al., 2016).

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Aier eye Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

ST and JC conceived the project. YZ carried out most of the experiments and wrote the manuscript. JL assisted in the cell culture and Western blotting. ZC helped in data analysis. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81570876).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the help of Dr. Zhongping Chen, Dr. Qichang Wang, Dr. Juan Chen, and the residents. Without their help, it would not have been possible to collect the clinical samples.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2019.01621/full#supplementary-material

References

Bakhashab, S., Ahmed, F., Schulten, H. J., Ahmed, F. W., Glanville, M., Al-Qahtani, M. H., et al. (2018). Proangiogenic effect of metformin in endothelial cells is via upregulation of VEGFR1/2 and their signaling under hyperglycemia-hypoxia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:293. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010293

Bakhashab, S., Ahmed, F. W., Schulten, H. J., Bashir, A., Karim, S., Al-Malki, A. L., et al. (2016). Metformin improves the angiogenic potential of human CD34+ cells co-incident with downregulating CXCL10 and TIMP1 gene expression and increasing VEGFA under hyperglycemia and hypoxia within a therapeutic window for myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 15:27.

Bakhashab, S., Lary, S., Ahmed, F., Schulten, H. J., Bashir, A., Ahmed, F. W., et al. (2014). Reference genes for expression studies in hypoxia and hyperglycemia models in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. G3 4, 2159–2165. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.013102

Balestrieri, M. L., Servillo, L., Esposito, A., D’Onofrio, N., Giovane, A., Casale, R., et al. (2013). Poor glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes patients reduces endothelial progenitor cell number by influencing SIRT1 signalling via platelet-activating factor receptor activation. Diabetologia 56, 162–172. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2749-0

Boutant, M., and Cantó, C. (2014). SIRT1 metabolic actions: integrating recent advances from mouse models. Mol. Metab. 3, 5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.10.006

Chen, C., Ridzon, D. A., Broomer, A. J., Zhou, Z., Lee, D. H., Nguyen, J. T., et al. (2005). Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178

Chen, D. L., and Yang, K. Y. (2017). Berberine alleviates oxidative stress in islets of diabetic mice by inhibiting miR-106b expression and up-regulating SIRT1. J. Cell. Biochem. 118, 4349–4357. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26089

Chen, J., Li, Y., Li, Y., Xie, L., Wang, J., Zhang, Y., et al. (2018). Effect of miR-29b on the proliferation and apoptosis of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells by targeting Mcl-1 and CCND2. Biomed Res. Int. 2018:6051407. doi: 10.1155/2018/6051407

Chen, M., Luo, C., Zhao, J., Devarajan, G., and Xu, H. (2019). Immune regulation in the aging retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 69, 159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.10.003

Chiu, C. J., and Taylor, A. (2011). Dietary hyperglycemia, glycemic index and metabolic retinal diseases. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 30, 18–53. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.09.001

Chong, Y. H., Fan, Q., Tham, Y. C., Gan, A., Tan, S. P., Tan, G., et al. (2017). Type 2 diabetes genetic variants and risk of diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology 124, 336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.11.016

Collin, D. L. A., Takeishi, K., Guzman-Lepe, J., Morita, K., Achreja, A., Popovic, B., et al. (2019). Generation of human fatty livers using custom-engineered induced pluripotent stem cells with modifiable SIRT1 metabolism. Cell Metab. 30, 385–401.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.017

Duan, Y. R., Chen, B. P., Chen, F., Yang, S. X., Zhu, C. Y., Ma, Y. L., et al. (2019). Exosomal microRNA-16-5p from human urine-derived stem cells ameliorates diabetic nephropathy through protection of podocyte. J. Cell. Mol. Med. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14558 [Epub ahead of print].

Esteves, J. V., Yonamine, C. Y., Pinto-Junior, D. C., Gerlinger-Romero, F., Enguita, F. J., and Machado, U. F. (2018). Diabetes modulates MicroRNAs 29b-3p, 29c-3p, 199a-5p and 532-3p expression in muscle: possible role in GLUT4 and HK2 repression. Front. Endocrinol. 9:536. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00536

Fan, Y., Qiao, Y., Huang, J., and Tang, M. (2016). Protective effects of panax notoginseng saponins against high glucose-induced oxidative injury in rat retinal capillary endothelial cells. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2016:5326382. doi: 10.1155/2016/5326382

Fu, X., and Ou, B. (2019). miR-152/LIN28B axis modulates high-glucose-induced angiogenesis in human retinal endothelial cells via VEGF signaling. J. Cell. Biochem. 121, 954–962. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28978

Gao, A., Feng, Y., Zeng, F., Wang, X., Wang, F., Yang, L., et al. (2013). [Protective effect of panax notoginseng saponins against femoral fracture-induced apoptosis in the superficial cells of rat renal cortex]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 33, 1692–1695.

Huang, Z., Lu, L., Jiang, T., Zhang, S., Shen, Y., Zheng, Z., et al. (2018). miR-29b affects neurocyte apoptosis by targeting MCL-1 during cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Exp. Ther. Med. 16, 3399–3404. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6622

Ji, H., Yi, Q., Chen, L., Wong, L., Liu, Y., Xu, G., et al. (2019). Circulating miR-3197 and miR-2116-5p as novel biomarkers for diabetic retinopathy. Clin. Chim. Acta 501, 147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.10.036

Jiao, D., Zhang, H., Jiang, Z., Huang, W., Liu, Z., Wang, Z., et al. (2018). MicroRNA-34a targets sirtuin 1 and leads to diabetes-induced testicular apoptotic cell death. J. Mol. Med. 96, 939–949. doi: 10.1007/s00109-018-1667-0

Kannenkeril, D., Bosch, A., Harazny, J., Karg, M., Jung, S., Ott, C., et al. (2018). Early vascular parameters in the micro- and macrocirculation in type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 17:128. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0770-4

Khalyfa, A., Marin, J. M., Qiao, Z., Rubio, D. S., Kheirandish-Gozal, L., and Gozal, D. (2019). Plasma exosomes in OSA patients promote endothelial senescence: effect of long-term adherent continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz217 [Epub ahead of print].

Khan, R., Kadamkode, V., Kesharwani, D., Purkayastha, S., Banerjee, G., and Datta, M. (2019). Circulatory miR-98-5p levels are deregulated during diabetes and it inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis by targeting PPP1R15B in keratinocytes. RNA Biol. 17, 188–201. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2019.1673117

Kitada, M., Ogura, Y., Monno, I., and Koya, D. (2019). Sirtuins and type 2 diabetes: role in inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function. Front. Endocrinol. 10:187. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00187

Klieser, E., Mayr, C., Kiesslich, T., Wissniowski, T., Fazio, P. D., Neureiter, D., et al. (2019). The crosstalk of miRNA and oxidative stress in the liver: from physiology to pathology and clinical implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:5266. doi: 10.3390/ijms20215266

Landrier, J. F., Derghal, A., and Mounien, L. (2019). MicroRNAs in obesity and related metabolic disorders. Cells 8:859. doi: 10.3390/cells8080859

Lu, T. X., and Rothenberg, M. E. (2018). MicroRNA. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 141, 1202–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.034

Majidinia, M., Karimian, A., Alami, F., Yousefi, B., and Safa, A. (2019). Targeting miRNAs by polyphenols: novel therapeutic strategy for aging. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1:113688 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.113688 [Epub ahead of print].

Mariani, S., Costantini, D., Lubrano, C., Basciani, S., Caldaroni, C., Barbaro, G., et al. (2016). Circulating SIRT1 inversely correlates with epicardial fat thickness in patients with obesity. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 26, 1033–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2016.06.001

Mariani, S., Fiore, D., Basciani, S., Persichetti, A., Contini, S., Lubrano, C., et al. (2015). Plasma levels of SIRT1 associate with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese patients. Endocrine 49, 711–716. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0465-x

Menzies, K. J., Zhang, H., Katsyuba, E., and Auwerx, J. (2016). Protein acetylation in metabolism - metabolites and cofactors. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 12, 43–60. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.181

Miloudi, K., Oubaha, M., Ménard, C., Dejda, A., Guber, V., Cagnone, G., et al. (2019). NOTCH1 signaling induces pathological vascular permeability in diabetic retinopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 4538–4547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814711116

Mishra, M., Duraisamy, A. J., and Kowluru, R. A. (2018). Sirt1: a guardian of the development of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes 67, 745–754. doi: 10.2337/db17-0996

Miyata, T., and de Strihou, C. V. Y. (2010). Diabetic nephropathy: a disorder of oxygen metabolism. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 6, 83–95. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.211

Myers, M. J., Shepherd, D. L., Durr, A. J., Stanton, D. S., Mohamed, J. S., Hollander, J. M., et al. (2019). The role of SIRT1 in skeletal muscle function and repair of older mice. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 10, 929–949. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12437

Nasr, M. A., Salah, R. A., Abd, E. M., Elshenawy, S. E., and El-Badri, N. (2019). Dysregulated MicroRNA fingerprints and methylation patterns in hepatocellular carcinoma, cancer stem cells, and mesenchymal stem cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 7:229. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00229

Nguyen, P. A., Won, J. S., Rahman, M. K., Bae, E. J., and Cho, M. K. (2019). Modulation of Sirt1/NF-κB interaction of evogliptin is attributed to inhibition of vascular inflammatory response leading to attenuation of atherosclerotic plaque formation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 168, 452–464. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.08.008

O’Kelly, F., Marignol, L., Meunier, A., Lynch, T. H., Perry, A. S., and Hollywood, D. (2012). MicroRNAs as putative mediators of treatment response in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 9, 397–407. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.104

Oltvai, Z. N., Milliman, C. L., and Korsmeyer, S. J. (1993). Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell 74, 609–619. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90509-o

Potente, M., Ghaeni, L., Baldessari, D., Mostoslavsky, R., Rossig, L., Dequiedt, F., et al. (2007). SIRT1 controls endothelial angiogenic functions during vascular growth. Genes Dev. 21, 2644–2658. doi: 10.1101/gad.435107

Santiago, A. R., Boia, R., Aires, I. D., Ambrósio, A. F., and Fernandes, R. (2018). Sweet Stress: coping with vascular dysfunction in diabetic retinopathy. Front. Physiol. 9:820. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00820

Sanz, M. N., Grimbert, L., Moulin, M., Gressette, M., Rucker-Martin, C., Lemaire, C., et al. (2019). Inducible cardiac-specific deletion of Sirt1 in male mice reveals progressive cardiac dysfunction and sensitization of the heart to pressure overload. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:5005. doi: 10.3390/ijms20205005

Saravanan, P. B., Vasu, S., Yoshimatsu, G., Darden, C. M., Wang, X., Gu, J., et al. (2019). Differential expression and release of exosomal miRNAs by human islets under inflammatory and hypoxic stress. Diabetologia 62, 1901–1914. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4950-x

Sasaki, Y., Ikeda, Y., Miyauchi, T., Uchikado, Y., Akasaki, Y., and Ohishi, M. (2019). Estrogen-SIRT1 axis plays a pivotal role in protecting arteries against menopause-induced senescence and atherosclerosis. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 27, 47–59. doi: 10.5551/jat.47993

Silambarasan, M., Tan, J. R., Karolina, D. S., Armugam, A., Kaur, C., and Jeyaseelan, K. (2016). MicroRNAs in hyperglycemia induced endothelial cell dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:518. doi: 10.3390/ijms17040518

Stehouwer, C. (2018). Microvascular dysfunction and hyperglycemia: a vicious cycle with widespread consequences. Diabetes 67, 1729–1741. doi: 10.2337/dbi17-0044

Su, T., Xiao, Y., Xiao, Y., Guo, Q., Li, C., Huang, Y., et al. (2019). Bone marrow mesenchymal stem Cells-derived exosomal MiR-29b-3p regulates aging-associated insulin resistance. ACS Nano 13, 2450–2462. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b09375

Thounaojam, M. C., Jadeja, R. N., Warren, M., Powell, F. L., Raju, R., Gutsaeva, D., et al. (2019). MicroRNA-34a (miR-34a) mediates retinal endothelial cell premature senescence through mitochondrial dysfunction and loss of antioxidant activities. Antioxidants 8:328. doi: 10.3390/antiox8090328

Trost, A., Lange, S., Schroedl, F., Bruckner, D., Motloch, K. A., Bogner, B., et al. (2016). Brain and retinal pericytes: origin, function and role. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 10:20. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00020

Varma, R., Bressler, N. M., Doan, Q. V., Gleeson, M., Danese, M., Bower, J. K., et al. (2014). Prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic macular edema in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 132, 1334–1340. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.2854

Ventriglia, G., Mancarella, F., Sebastiani, G., Cook, D. P., Mallone, R., Mathieu, C., et al. (2019). miR-409-3p is reduced in plasma and islet immune infiltrates of NOD diabetic mice and is differentially expressed in people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 63, 124–136. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-05026-1

Wang, Y., Zheng, Z. J., Jia, Y. J., Yang, Y. L., and Xue, Y. M. (2018). Role of p53/miR-155-5p/sirt1 loop in renal tubular injury of diabetic kidney disease. J. Transl. Med. 16:146. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1486-7

Whitehead, M., Wickremasinghe, S., Osborne, A., Van Wijngaarden, P., and Martin, K. R. (2018). Diabetic retinopathy: a complex pathophysiology requiring novel therapeutic strategies. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 18, 1257–1270. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2018.1545836

Xu, H., and Chen, M. (2017). Diabetic retinopathy and dysregulated innate immunity. Vis. Res. 139, 39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2017.04.013

Yamakuchi, M., and Hashiguchi, T. (2018). Endothelial cell aging: how mirnas contribute. J. Clin. Med. 7:170. doi: 10.3390/jcm7070170

Yuan, H., Ma, J., Li, T., and Han, X. (2018). MiR-29b aggravates lipopolysaccharide-induced endothelial cells inflammatory damage by regulation of NF-κB and JNK signaling pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 99, 451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.060

Zaiss, M. M., Maslowski, K. M., Mosconi, I., Guenat, N., Marsland, B. J., and Harris, N. L. (2013). IL-1β suppresses innate IL-25 and IL-33 production and maintains helminth chronicity. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003531. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003531

Zhang, H., Li, H., Ge, A., Guo, E., Liu, S., and Zhang, L. (2018). Long non-coding RNA TUG1 inhibits apoptosis and inflammatory response in LPS-treated H9c2 cells by down-regulation of miR-29b. Biomed. Pharmacother. 101, 663–669. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.129

Keywords: diabetic retinopathy, miR-29b-3p, SIRT1, human retinal microvascular endothelial cell, apoptosis

Citation: Zeng Y, Cui Z, Liu J, Chen J and Tang S (2020) MicroRNA-29b-3p Promotes Human Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cell Apoptosis via Blocking SIRT1 in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Physiol. 10:1621. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01621

Received: 18 September 2019; Accepted: 24 December 2019;

Published: 29 January 2020.

Edited by:

Qiaobing Huang, Southern Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Qilong Wang, Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, ChinaJianbo Wu, University of Missouri, United States

Copyright © 2020 Zeng, Cui, Liu, Chen and Tang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiansu Chen, Y2hlbmppYW5zdTIwMDBAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Shibo Tang, dGFuZ3NoaWJvQHZpcC4xNjMuY29t

Yong Zeng

Yong Zeng Zekai Cui2

Zekai Cui2 Jian Liu

Jian Liu Jiansu Chen

Jiansu Chen