- DigiLexis Consulting, Lome, Togo

Credential Exchange Infrastructures based on open standards are emerging with work ongoing across many different jurisdictions, in several global standards bodies and industry associations, as well as at a national level. This article addresses the technology advances on this topic, particularly around identification mechanisms, through the Self-sovereign identity model. It also tackles necessary institutional processes and policy concerns relating to their implementation. Rooted in a sociohistorical culture and practice of inquiry, the goal of the article is to bring emerging digital identity systems within the grasp of a wider public as well as to contribute to mutual understanding across stakeholder groups (technical community, governments, international cooperation entities, civil society and academia) about what is at stake. This is expected to enhance their capacity to better navigate across the pitfalls of this transition period from paper to digital systems and the full adoption of the latter, with each of these stakeholders playing a part in enabling trust around digital identity infrastructure and transactions, both within related ecosystems and in the broader society. This article makes contributions around three axes. First axis is conceptual and analytical. The article outlines three conceptualized phases in the evolution of identity practices in history with the hypothesis that the availability of new record-creation methods invites changes in, and expansion of, the existing identification processes. This helps make a stronger case for why the Internet needs an identity capability. In addition, the article defines or elaborates on key concepts including identity, credential and trust. The second axis of the article is a case study on self-sovereign identity as instantiated by the Sovrin network. The case study presents the technology and its design with a view to enabling a non-technical public to understand what it is and how it works, while highlighting the fact that the technology still needs institutional processes to make it work as intended. The final axis of this article provides guidelines to policy actors potentially facing the need to enable large scale implementations of these emerging technologies, as they mature. Policy-makers approaching this material may want to read this section first and then return to the rest of the paper.

Introduction

Most of the population in the industrialized countries and at least city dwellers over the rest of the world are familiar with situations where, for all intents and purposes, they have to present identifying documents before they can proceed with the business at hand. From a basic standpoint, that is an identification process which is enabled by some administrative artifacts we generically call identity documents. Without those documents, individuals will, in the best-case scenario, have to spend a lot more time resolving their identity for the person or institution they are faced with, or they just might not get anything done as they intended. For that reason and for several other benefits, we go through the process of getting those documents and we carry them around with us so that we can use them as needed. For the same reasons, some other people may find incentives to forge those documents where they cannot or do not want to get proper ones. Therefore, authenticating those documents themselves, as well as authenticating the link between them and their holder (checking the accuracy of their identity function), has been a critical need and endeavor throughout their multi-century history.

For the most part of that history, those administrative artifacts have been made in paper or in paper-like material. Over time and given the above-mentioned risks, various techniques and technology have been used to make them more reliable and tamper-proof as much as possible, improving their identification capability overall. In recent times, that challenge has been taken up by digital technology using biometric data to bind the body of the identity holder (subject) to those artifacts. However, we cannot address digital identity exclusively just as the latest form of identity on-land. The “land of origin” for the digital itself is the Internet, not just from its native protocol stack but also as popularized by the Web and today’s mobile apps. Solving the identity problem on the Internet is of critical value once we realize that the digital economy is here to stay and that online identification loopholes and malpractice are a major hindrance.

The purpose of this paper is to introduce to stakeholders other than the small group of technologists involved in building solutions to address this issue—meaning governments, international cooperation entities, civil society and academia—but particularly to policy-makers, one of the fundamental ways in which the Internet identity problem is being solved today using a framework known as Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI). The Sovrin Network, an implementation of that framework using blockchain technology, will serve as a case. Following that exposé focusing on the technology, institutional aspects of this implementation will be teased out by examining its governance mechanisms. And finally, a number of recommendations are formulated for policy-makers, particularly in the countries less familiar with, or less engaged in, these fast-paced developing technologies, at this point in time. Before we get to the empirical part however, the paper sets the stage with a theorizing view of a historical account of the evolution of identity practices, following an overview of the epistemological and methodological context in which this approach is rooted.

Methods

From a methodological1 standpoint, there are two prongs to this research article. First, it develops a conceptualized narration of the evolution of identity (the way people have come to handle the process of identification over time) and the available enabling tools. We make the case that digital technology, particularly the Internet, is still in search of its own version of identity which it will inevitably find—or humanity will not fully enter the digital era.

The second prong in our methodology is the use of a case study to illustrate what is shown to be predictable from the first prong: that great strides are being made, by necessity, towards achieving a viable solution for digital identity. The case selected is one of the most current, indeed still emergent, technologies for digital identity to show how the problem of identity on the Internet can be solved and how close we might be to solving it.

The value of the method used in this paper is grounded in sociohistorical practices of inquiry (Somers 1994; Somers 1998; Hall 1999; Tilly 2006; Tilly 2008). First of all, according to Tilly (2008), “transactions, interactions, social ties, and conversations constitute the central stuff of social life.” That postulate characterizes the epistemological stance he calls “relational realism.” Reinforcing the same idea, Somers (1998) notes that the basic units of social analysis are “neither individual entities (agent, actor, firm) nor structural wholes (society, order, social structure) but the relational processes of interaction between and among identities.” Furthermore, the notion of relation in this framework also has theoretical implications. On the one hand, society is a bounded set of “numerous matrices of patterned relationships, social practices, and institutions mediated not by abstractions but by linkages of political power, social practices and public narratives” (Somers 1998). On the other hand, theory in this context is mostly a generalization about observable facts treated as effects of unobservable factors which are only inferred, to the extent that they appear to be compellingly necessary to explain certain outcomes and, in that regard, relational realism is also and particularly based in that link posited between observable facts and non-observable ideas with an explaining power about those facts.

Within this framework, theory does not depend only on the capacity of the rational mind applying universal and a-temporal rules of formal logic, which would imply that a theory remains eternally true as long as those rules obtain; rather, relational realism acknowledges by anticipation that theory is “historically provisional” (Somers 1998); it is time-bound and subject to change. Concurring with that, George and Bennett (2005) further emphasize a distinctive trait of theory in social sciences, pointing to the fact that theory is not exclusively devoted to enabling prediction but also to explaining social phenomena or patterns. While doing the latter, cumulative and progressive advances into theorizing may be accomplished, notably through the strengthening and the wider applicability (to multiple settings or to different phenomena) of analytical frameworks that may have proven more heuristic than others.

To complete this methodological overview, we turn to Hall (1999) who frames sociohistorical research as a practice whereby different research communities make claims to knowledge using different types of discourse which they develop in an effort to sustain their claims. Hall calls those types formative discourses in that, ultimately, they in turn help form different practices of inquiry. He distinguishes four such discourses, each one having its role across the different practices of inquiry: those include value discourse, narrative, social theory, as well as explanation and interpretation discourse.

On the other hand, Hall identifies mainly eight “alternative and yet interdependent methodological practices of inquiry” (p.169) split over two orientations, four particularizing practices being one orientation, and four generalizing practices the other. None of the practices of inquiry is discursively pure; rather, each one of them is “an ordered hybrid of discourses” (p.216) only with a predominant role of methodological significance for one particular discourse. In other words, each one of the four discourse types is formative for one particularizing and for one generalizing practices of inquiry, while playing a minor role for the other practices.

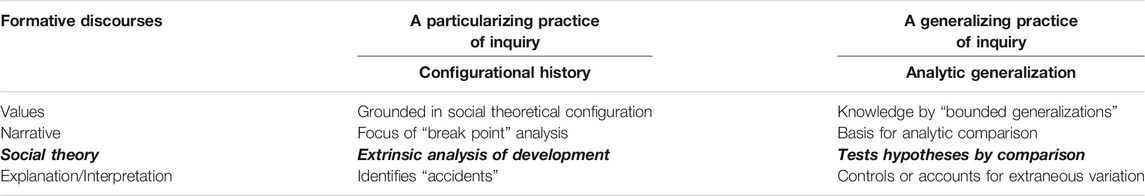

For instance, in what I call below a theoretical reduction, we are guided by social theory discourse. Social theory discourse is formative to the particularizing practice of configurational history by enabling extrinsic analysis of development, and to the generalizing practice of analytic generalization through the testing of hypotheses by comparison. The first of the parts of this paper addressing the subject matter (A Theoretical Reduction: History and Concepts section) falls under the latter: I am extrinsically analyzing historical periods, the delineation and the connection of which is only based on the focus of external observers (us) on a particular problem of interest (identity). That focus is not necessarily that of the actors contemporaneous to, or even involved in, the events and phenomena that are covered by this account. Such theoretical delineation or periodization of history around identity gives perspective, both retrospectively and prospectively, and allows one to see the scale of the challenge and explore what potential solutions may look like.

Later on, when different digital identity solutions are fully deployed and effective, this work may help us elaborate hypotheses to be tested with regard to which ones of the solutions might prevail and under which social and other non-technological conditions. In that possible future scenario, we will be inquiring for analytical generalization using social theory discourse (Table 1). For now, let us expound our proposed social theory-oriented configuration of the history of identity practices, starting with the underlying theoretical view.

TABLE 1. The role of formative discourses in inquiry practices of configurational history and analytic generalization, with their common ordering discourse and its roles in italic bold [based off Hall (1999), Tables 7.1 and 8.1].

A Theoretical Reduction: History and Concepts

By theoretical reduction I am abstracting and conceptually assembling a storyline or simply a narrative account from empirical phenomena. In this case, I am linking historical events or processes, which certainly are more variegated in their actual occurrence, so as to offer a picture of theoretical significance or to generate a theoretical statement. In the following, such theoretical reduction is applied to the way identity has been historically addressed from merely using humans’ natural senses to using digital technology as a means of making and keeping records2. But let us start with the statement of our theory which provides the basis for this way of thinking about the evolution of identity practices through the lens of historical periodization.

Theory Formulation

Record-making techniques enable or augment human agency3. More precisely, new record-creation techniques bring about new forms of mediated human agency; new ways for humans to be present, to decide, act and change things at a distance. With a new widespread record-creation technique comes a significant extension of human agency, supported by a number of accompanying mechanisms.

By new, we do not just mean a technique that is chronologically more recent in existence, but a technique that allows to do significantly more than its last predecessor or to do really new things which its last predecessor couldn’t do, in such an amount that it can be considered a life-changer for people in need of using that type of techniques. Agency is defined in the online Sociology Dictionary as the “capacity of an individual to actively and independently choose and to affect change; free will or self-determination”4. It is the capacity of human individuals to exercise their free will, to reflect or deliberate, form an intention or choose a purpose of their own, make a decision and act on their own behalf. Our need to resort to the concept of agency, which is borrowed from institutional theories, particularly institutional sociology, is not commanded by a collective action problem where the free will of individuals is faced with collective structures, as usually the case. Rather, the main focus in our context is on the identity subjects who are individual entities (here humans) and to whom we are applying the concept of agency hence, the apparent emphasis on individuality in our definition. But given that theoretical background of the concept, let us clarify further some of the implications of using it in this context with our formulation of its definition.

We do not think “social phenomena result from the actions of atomized (socially unconnected) individuals” but rather, that “human agency is both constrained and enabled” (Emirbayer and Mische 1998; Abdelnour et al., 2017). While individuals with agency are free to the extent which they, and the society as a whole, can conceive of freedom, they exist and evolve within physical and social settings and as such, they are not completely foreign to pre-existing norms and commitments that prevail in those settings. As a consequence, acknowledging agency for individuals does not mean we think pure and absolute individualism is possible and that such individualism prevails over social structures. Most likely, social phenomena are an outcome of an open interaction between agency and structure5.

Extending human agency through record-making techniques then means that the above-mentioned multi-faceted capacity by which we define agency for the actual physical individual can be fully projected and maintained through the type of records at hand, whether paper-written (using human language alphabet, numbers and humanly created symbols) or digital (using a wider array of characters and symbols, numbers, and various codes based on machine languages as well as encoding schemes, etc.).

One particular type of mechanism which does that is called a credential6. Credentials are not just any assertion of claims; rather they are meant to be trusted (to be accorded the status of truth) and, as a result, they need to meet a number of requirements that make them credible and reliable in the relevant context. In effect, credentials modify the boundaries of human agency only to the extent that others7 trust what is being asserted through them. Such extension raises the need to address identity within the new scope of agency, using the very means of that record-making technique which enables it in the first place. It would be self-defeating to allow the claims about somebody, or something the credential was meant to warrant, to be misattributed to somebody else or be taken for something else.

Any given record-making technique fosters the development of corresponding practices and institutions. In other words, every new record-making technique enables new practices as well as new institutions or institutional processes. The new record-making technique must clearly provide an added value compared to the older techniques; it has to make business and life easier, in one way or another, while improving institutional processes and overall performance. This means at least one of the following: it can significantly extend the pre-existing scope of human agency; or it can significantly reduce the cost, or take much of the friction out, of exercising human agency under the pre-existing scope; or it can do both. The potential or actual value to be added by the new record-making technique, including the extended scope of agency it may enable, dictates the need and interest to embrace such technique as well as to address identity within that scope using the resources availed by that technique.

Questions that arise include:

• How can we make sure the new technique is reliable, trustworthy, in the various ways it extends human agency?

• How can we make sure it accurately represents personhood as well as the reliable attribution and discovery of the actual roles, rights, liabilities, privileges and authorities which any given individual instance of personhood may bear?

• How can we avoid falsehood in such representations?

In generalized terms, these are and will always be the identity challenges at every turn of significant change in the nature of records and the affordances of the means by which they are made, due to related technological change or evolution.

A Three-phase Evolution

Phase I, Face to Face

At the beginning, there are people living together. They go about doing whatever they need to do to live and survive, to keep going with their life and to thrive. That necessity generates all sorts of behaviors including interactions with others as well as transactions. Conceptualizing the evolution of identity, one may describe the first phase as follows. Mostly, individuals’ behaviors and actions are performed and can only be performed when they are physically involved, either themselves or by another representing individual. And anybody who would witness such behaviors or actions can only rely on the capacity of their own senses and human memory to identify the person who was involved in those actions, interactions or behaviors as someone they have already seen, met or someone they knew. This is all the more feasible that the chances of having to deal with people popping in, out of nowhere, hailing from humanly unreachable distances are very low and, as a consequence, such rare occurrences are easily manageable for the human memory and, if necessary, by mobilizing the community’s attention (collective memory). It may be noted that, already in this phase, identity is ascertained—authenticated, I might say, by one’s own means and for one’s own intents and purposes—through the ability to match incoming information (exhibited by the person appearing now before us) with an information record we are already familiar with which is generally stored in human memory8.

In sum, to a great extent during this phase, human senses and memory are enough for people to be able to attribute to their fellow community members whatever they need to for practical purposes, in a consistent manner, over whatever period of time may be needed. Such empirical capacity to make attributions and to make them consistently is also what makes human beings able to attribute and recognize roles, rights and responsibilities (duties)9 in relation with any given individual in their social environment.

Phase II, Paper

With the thirteenth century paper revolution—accelerated by diffusion of Gutenberg’s printing press by the fifteenth century—documentation practices evolved to integrate paper and written records including documentation of identity.

For paper to have a meaningful impact on the things humans do as well as on how they do those things (their behaviors), on the state of anyone’s roles, rights or responsibilities in the society, it will need to be used in ways that can be trusted enough by all key stakeholders, including anyone who might have claims that could interfere with existing roles, rights or responsibilities as well as on the community’s common resources. This implies that those written records will have to be endowed with some authority—in relation to their ability to accurately reflect the outer world order. Such world order is shaped by, among other things, people’s decisions and choices which re-order the distribution of rights and obligations. The way that reordering is done and the result has to be acceptable in the eyes of the key stakeholders (and beyond them, the community overall), and that is achieved by following certain protocols and using certain symbols and signs—which is facilitated by the sharing of the same beliefs. To trust this type of mechanism means that all key stakeholders accept it as a valid way to represent people who may then use such representations to enact decisions and choices, to assert or alter their roles, rights and responsibilities, and possibly those of others, provided that protocol and format requirements are met.

Historically, particularly in the West, those tools included seals, handwritten signatures, bureaucratic procedures plus, later on, agreements among nations-states and the continuous integration of evolving techniques, notably in more recent times, some degree of technology into paper-based record-making methods. All of that is done while keeping an eye on the need to prevent or mitigate the risks of tampering. The Church, the King and then the Government, or other accepted authorities (banks, schools, hospitals) backed or regulated by any of the first three, vouched for representations made through those systems. In their respective setting and at the best of their authority, those institutions along with their system of governance have served as the source of trust in this type of identity mechanism10, 11.

As shown in Chango (2012), it took a long historical process to get from the time when, as a document, the passport started crystalizing in its core components and functions, in the 15th century, to a place where it became an internationally accepted and effective standard credential for all border-crossing travelers, in the 20th century. In effect, it is only after the First World War that the first international conference was ever convened, by the League of Nations, to agree on international guidelines for the passport; that was the “Conference of Passports, Customs Formalities and Through Tickets” held in Paris in October 1920. Other follow up conferences include the “Conference on safety and viability of international travel” held in Chicago in 1944 which gave birth to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)12. Ever since, the task of refining passport standards so as to tackle the challenges to its efficacy, has fallen to ICAO.

Basically, identity through paper-based written records is essentially made by describing observable attributes and known facts about the identity subjects. That information and relevant data are collected at enrollment and kept in paper files which are classified using some bureaucratic physical scheme, with a view to easing their manual retrieval at any point in the future if need be. A subset of that information and data, including particularly most observable attributes, is captured on a handy document which is given to the identity subject (making them a holder, indeed the only legitimate holder, of that document.) We have left the first phase, the Face-to-Face identification process where enrollment is random and authentication is done live, based on personal memories. Now the identifying entity is impersonal—it is an institution, e.g., the state, the state bureaucracy, the government—and so is their memory made of all the information and data they retain about the identity subject, in paper files in the back-end office. The memory is objectivized through a file system, a sort of paper database, and several potential individuals with the proper authorization may check out the content of that memory. Distinctive features in this model include photography and inked fingerprint, both of which are anthropometric data or data source but may arguably be considered as early biometrics. Authentication is done by looking at the content of the document and observing the identity holder in order to check the observable information in the document,13 including the photography, against its living source. In this phase, regular authentication still relies widely on human eye and visual observation capacity. At most, law enforcement would use a magnifying glass to scrutinize the ID photography details or to parse the inked fingerprint they have on file, trying to match them with the living face of an identity holder or with another specimen of fingerprint which they just collected from a suspect, for instance14.

Phase III, Digital

Digital technology opens up two main paths for further progress. The first is the use of digital technology as an additional step to increase security and trustworthiness within the paper-written records paradigm15. I would call this a linear path, the path of incremental improvement (within the same paradigm).

The second one is a path of a paradigm shift or a qualitative leap; it introduces a completely new way of expressing and sharing identity information which would be commensurate with fully digital record-making settings. This path appears inevitable because, among other things, the Internet already allows people to conduct a sizable amount of their daily life operations online—while adding new capabilities to the previous two phases (the phase of physical presence-based agency and the phase of paper records mediated agency). Furthermore, many of those operations can be fully completed and validated without any physical presence or interactions during the process, neither for the person conducting those operations nor for the party on whose behalf they are conducted.

The question now is, can we conduct any of those operations requiring a proof of our identity without sending around, on the Internet, an electronic copy of our limited and monolithic physical credentials or some sensitive identity-related information? In other words, are we merely going to transpose analog methods to electronic environments, while applying them to electronic versions of physical stuff (thereby deemed digital), or are we going to shift to digitally doing digital stuff? Clearly, there is tremendous value to be gained, at scale, if we could do the latter and do it well—and that is the challenge many dedicated technologists have been working on for almost two decades16.

Those two paths may be recognized as that of 1) digital identity in the form of a digitized physical credential, and 2) that of digital identity in the form of a fully digital (online) credential. It must be noted though, that under some circumstances, the first one may also help operate online. As a matter of fact, these need not necessarily be two different things. Digital identity may associate a physical token with online digital records and systems, both enabled by the same digital technology, making it possible to use or to refer to the same identity offline and online. Either way, it is the capability of online operations afforded to the identity holders themselves which brings about the full value of a new extension of human agency. In any case, the state of the technology today clearly allows us to think of digital identity as something of its own, based only on digital components, totally operable online in a digital environment. And that is our primary concern in this article: whatever happens outside the networks, how can that lead to digital identity solutions that work over the networks?

Clarifying Key Concepts

Identity and Credential

The community mobilized around the Sovrin Foundation has put together a Glossary which defines identity as “Information that enables a specific Entity to be distinguished from all others in a specific context. Identity may apply to any type of Entity, including Individuals, Organizations, and Things. Note that Legal Identity is only one form of Identity.” Back in 2005, Kim Cameron in his Seven Laws of Identity17 offered the following definition for digital identity: “a set of claims made by one digital subject about itself or another digital subject.” This definition was then embraced by a cross-section of software industry players plus various other stakeholders18. From the same Sovrin glossary, a credential is “A digital assertion containing a set of Claims made by an Entity about itself or another Entity. Credentials are a subset of Identity Data. A Credential is based on a Credential Definition.”

Before we get into discussing those concepts and some corollaries, I propose to consider the following reformulations or alternative definitions.

Identity is basic information about any individual entity, in a given context, 1) which said individual entity can use to support the validity of a claim they might need to make relating to themselves, or 2) which a legitimate party needs to verify, and can do so, in order to make a necessary decision about said individual entity, in the context at hand.

As an informational resource, identity often is in a structured format (especially when it comes in the form of a credential: see definition below) but it may also be any piece of information fulfilling either one of the two requirements in this definition. It is basic information in the sense that it generally is part of the primary information that is used, or is most relevant, to define the concerned entity in the context at hand. Here, the term “individual” doesn’t necessarily refer to an individual human being, but to an individual instance of any entity. An individual entity in the physical world is a physically discrete thing which can be counted as one among its kind. A corporate entity may be one legal entity but instantiated through several different branches; each one of those branches may qualify as an individual entity (even if some assertions can also be made about the corporate legal entity as a whole; that is because identity is contextual19). In other, non-physical, environments, an individual entity is whatever is structured, whether through syntax or other means, to perform as a unit of its kind.

Starting from the Sovrin Glossary’s definition of credential, we shall note that there is a difference, generally, between a credential and simple information as part of an assertion: a credential is a specific type of assertion which exhibits characteristics that make it trustworthy for most stakeholders who are ready to consider it as a proof for the assertion it is making.

A credential is a document, an object or a data structure designed or intended to make any kind of assertion about an entity, according to a method that qualifies it as proof of what is being asserted. As a result, it may also serve as proof for any number of claims one may directly derive from such assertions20.

In that sense, the two functions enumerated in the above reformulation of the definition of identity are concretely achieved using appropriate credentials. A corollary of the two definitions (of identity and credential) is that it is only by way of a credential that identity becomes a concrete, usable, portable and effective tool, in the form of some sort of artifact whether physical or digital, which is thus recognized by a variety of stakeholders as an identity credential. In the expression “identity credential,” the notion of credential adds more of a dimension of proof to the simple notion of identity. A second corollary is that identity credentials are, a priori, a subset of credentials, a specific type of credentials while, arguably, credentials in general may be used as well for a variety of other things not intended for identification21.

Any informational resource that can fulfill either of the two functions outlined in our definition of identity, or both, is enough to be referred to as identity in the practical context of identity management. The information needed to achieve those two basic functions may include all of the attributes on an identity credential, or just one of them, although in the latter case, the identity subject in the physical world will still have to show the whole credential. In the digital world however, the technology allows the credential holder to select and present only the one relevant attribute or even to derive a lower-definition claim from a pre-defined, higher-definition attribute, as opposed to presenting the original attribute itself in a transparent manner (e.g., “Age 21 or older” as a claim, instead of “Born on August 30, 2000” for instance, as an attribute).

Overall, at the very basic level, identity management processes need the following:

1) An individual entity who will be the one whom the identity information is about (also referred to as identity subject);

2) The registration of said individual entity by collecting and storing data about them so that the data can be discovered or retrieved later on, for verification and authentication purposes;

3) The subsequent issuance or attribution of some token, potentially with authenticating capabilities (which is known as a credential), so that it can serve as proof of registration as well as proof of a number of facts about the registered individual entity, including the ones collected at time of registration.

There might be other requirements depending on the technology being used. But in the absence of any of those three things, there can’t be a reliable process of identification and thus, there is no identity management system22.

About Identity and Uniqueness

The two definitions of identity given above, from Sovrin Glossary and from Kim Cameron’s Laws of Identity, may appear to show some tension in the way they are formulated: the first definition makes of the property of uniqueness (capability to distinguish a specific entity from all others) its central point, while the other doesn’t mention it but rather focuses on claims. Why is that? And if uniqueness is actually involved, where do we locate and how do we apprehend it?

A long historical track of mathematical elaborations as well as philosophical debates around identity have probably prepared the ground for the compelling notion and inclination to think that oneness and permanence are constitutive dimensions to the concept of identity (Perry 1975; Parfit 1984; Noonan 1989). Moreover, the notion of authoritative identity credentials as a monopoly of the government has also instilled over time some sense of requirement for identity to be unique in order to be true. For multiple generations, the only identity which nearly all stakeholders regard as authoritative, that is, as the “real and true” identity, is the one that the government vouches for through a national credential23. Even any other identity credential, most of the time, relies on a government-issued credential, that is, the government-defined identity. In the resulting mental model, people would have a hard time with the idea that one individual can have multiple, alternative national or legal, or simply valid, identities within the same nation-state.

We know from experience that identity verification encounters generally are trivial and do not involve proofing of uniqueness at any level. Even authentication is more about accuracy than it is about establishing proof of uniqueness of anything, as that process normally deals with one identity subject and one credential at a time. But the whole process works because uniqueness is implied, and enabled at some point the whole identity value chain. How does that work? Identity verifiers are mostly concerned with checking for the following:

1) The identity holder is actually the subject to whom the credential was intentionally issued.

As a consequence, only the intended subject of any given credential must be able to control it, under normal circumstances24.

2) The source of the credential, its issuer, is clearly and reliably identifiable from the credential.

This helps assess the value (particularly in terms of pertinence to the context and potential for truthfulness) to ascribe to the assertions or attributes contained in the credential and, subsequently, the veracity or level of confidence to accord to the claims enabled by those assertions or attributes.

3) There are no other conditions, either originally included or having occurred since the credential was issued, which invalidate it at the time, or for the context, of use.

There are no restrictions added to the assertions which may exclude a specific use case or may not apply to the context at hand; at the time of use, the credential is not materially distorted or deteriorated, possibly transforming it into something the original issuer wouldn't endorse, or it hasn't expired or hasn't been revoked,25 etc.

Those requirements are general, also applicable to non-digital, physical credentials. However, if we were to spell out the same set of requirements applying them specifically to the digital realm, the third requirement is better split into two. That is because typically, physical credentials not involving any digital technology are tampered with only physically or materially, so that the result can generally be spotted by expert human beings (through naked eye or possibly with the help of a simple piece of equipment such as some special electric light.) In any case, the possibilities for tampering with digital credentials are potentially endless compared to physical credentials. For that reason, an exclusively digital context would have requirement “3” above split into a new requirement “3” which will simply read: “The credential is not restricted or has not been revoked,” and the following requirement:

4) The credential has not been tampered with.

The credential has not been altered or compromised by third-party’s malicious manipulations either to misappropriate it or to make other false assertions.

Focusing here on the digital context, requirement “2” above addresses the provenance of the credential, while the remaining three requirements address the fidelity of the credential26. The provenance requirement is mixed in that, while it may use cryptographic functions relating to the issuer’s identifier, the full assessment of the authority and credibility of the issuer to make the assertions conveyed by the credential is enabled through governance processes including some knowledge of the outer world environment. The fidelity requirements ensure that the credential is true to itself, that it fully works and is appropriately used, as designed. The fidelity requirements are fully enabled by cryptography and they represent the “What you see is what you get” part in the credential exchange—here meaning, what you see through cryptography.

Practically meeting requirement “1” from the list above is what brings up the uniqueness dimension in the conceptualization of identity as a subject of management. That is not to say that an entity can only have one identity. The same attribute may be claimed by millions of people but if proof of that attribute is needed for any particular individual, it will have to be part of a credential which said individual can show for a simple verification and which, at best, can be authenticated. The farther we are from authenticating an assertion or an attribute about a particular entity, the lesser we can be certain that said assertion or attribute is true about that particular entity. Then we cannot build any commitment on that identity (which links a particular subject to an assertion about them), since some other entity foreign to it can wrongfully claim it and (mis-)use it. Clearly, the reason for this requirement is that typically, an identity credential can only realize its true purpose and full utility when it is tied to only one subject at a time as a single source of agency27. Binding any given identity to a unique individual entity as the intended subject of that identity is the condition that makes it possible later on to verify whether the presenter of said identity is its rightful holder or not. And the best way to attest to that binding is to include authentication as part of the verification process (which is not always done with physical credentials).

Depending on the context in the physical world, the verification of requirement “1” is done in various ways with varying levels of certainty or assurance about the result. Historically, at the beginning of the rise of identity documents, law enforcement relied on the good will of identity holders to dutifully use only the documents that were intended to them by the authority, not someone else’s. At that phase, the proof was the weakest, assuming that can even be called a proof. After that, the credential-subject binding method was based on what I call anthropometrics,28 along with other evidentiary features of uniqueness, including photography and ink fingerprint, affixed to identity credentials in order to bind the actual identity subject to the document. Then, most of the time, verifiers would just look back and forth at the picture on the credential and at the face of the identity holder; they also have the possibility to use the date of birth in order to assess its plausibility as compared to the estimated age range that could be imputed to the physical subject. That is still a weak correlation method. Only when the subject is submitted to verification at a law enforcement office where fingerprint can be taken again and compared with what is on the identity holder’s document or on file, only then a strong case can be made based on evidence supporting that requirement “1” is met.

With digital identity, there is the model of a physical credential enabled by digital technology but which to a large extent operates as a more sophisticated version of the previous type of credential, whether it is used as a stand-alone token or in interface with online systems, still in the physical presence of the subject holding the credential. Here, the enabling elements with regard to requirement “1” include biometrics (electronic fingerprint, iris scan, etc.) which is encoded, that is, translated into a machine language, affixed to the credential, and will be shown to a machine reading equipment connected to an electronic database during the verification or authentication process. At that point, relevant biometrics is captured anew from the identity subject and is matched with the biometrics the machine reads from the credential which is matched with the biometrics previously stored in the database, in order to authenticate the credential, the data contained in it as well as the binding of the subject to that credential. This brings us to the model of a totally digital identity online. With this model, the physical subject does not interface directly with the system but through computer networks, and therefore cryptographic keys—which are secret information that is supposed to be known or possessed only by the identity holder—are the key element that enables the proof of binding between the credential and the user presenting it, that is, the identity subject (as we will see in The Trust Over IP Technology Stack section, particularly at Layer 3).

In any case, establishing the uniqueness of an identity subject in relation with the credential being presented is, in a sense, done by proxy: the uniqueness of the correlated subject derives from, and is supported in proportion of, the strength of the evidence supporting the binding of the credential at hand with said subject. The stronger the evidence available to support that binding, the more certain we can be that the current holder29 is the rightful identity subject and therefore she or he is unique in that position, since it is a feature of the system that (by design) a credential is bound only to one subject who is the unique legitimate holder.

To accomplish the identity functions (as per our definition), some information about the identity subject first needs to be recorded in some fashion, somewhere. That first recording is also known as registration. Registration is the key procedure in the whole identity value chain which provides the basis for uniqueness and for meeting requirement “1.” In effect, one fundamental role for any registration scheme is to reflect a basic truth about the state of the world with regard to the existence of the things to be registered. One of the basic laws (or facts) that structure the world as perceptible and comprehensible by human beings is that all the things which humans can naturally and materially observe as such exist in their original form in one instance only. For instance, a human being is located in one physical body only. Therefore, if the relevant things to be registered exist or are observable in their original form as discrete single units, then each one has to be registered only once, and has to be instantiated only as one in any given register of those things. Those entities can only exist as one in the modeled world of their kind through registration, as they exist in the original physical world: otherwise stated, to every relevant individual entity corresponds only one registration entry, under the same registration scheme30. Registering any entity more than once in the same register or database, under the same rules, as if the different instances of registration represent distinct, unrelated entities, would defeat the purpose of representing the world as it is; it would be a flawed representation of the world where the things being registered belong, which will lead to a flawed system (fraught with risk of impersonations and other fake representations)31.

As we can see, the relevant notion of uniqueness to keep in mind when defining the concept of identity is that of relational uniqueness: the uniqueness of the individual entity which any given identity is bound to as its rightful subject, and therefore the uniqueness of the relation between an identity credential and the individual entity it correlates with. In Cameron’s definition,32 the key word is “about.” How do you know for certain it is about this one and not that one, from among many potential identity subjects? By making sure you build it in such a way that it cannot be, at the same level of clarity and certainty, linked with or bound to more than one entity.

We know that, in the physical world and when it comes to the identity of human beings particularly, verification and authentication processes involve, more often than not, the physical presence of the identity subject. On the other hand however, the digital realm is characterized by the absence of the physical subject as part of the same processes and basically at all points where credentials need to be presented or claims need to be made and supported. Consequently, the challenge for identity in the digital world is broader. We must accomplish things requiring identity through digital information alone, in a sea of other digital information. And under the right conditions, a lot of those things can be done in a manner that can be as effective as, if not more effective than, what the direct action of an actual human being would accomplish in the same situation on land, and at a lower cost. As a result, identity no longer concerns only natural, embodied entities with agency; it is also, in a way, the identity of information itself.

Identity: “Who you are” vs. “What you are”

The trouble with overemphasizing uniqueness in matching identity attributes to an identity subject is that it opens the door to the confusion that leads to conflating the two, having us thinking of identity as a monolithic and complete informational representation of the identity subject. Such misleading perception then shapes expressions that lead to unreasonable expectations and inadequate mental models. The expression “Identity credentials prove who you are” sums up that misleading notion. We are now going to examine that conception as well as its assumptions, implications and limitations from different angles33.

“Who you are”—The question “Who are you?” is often used as a prompt to elicit a response that is considered to be the identity of the respondent. However, the pronoun “Who” in this context suggests an essentialist or at least a monolithic view of identity: a person is always the same as self, they are who they are, with all their facets at once, regardless of context. From that standpoint, the “who” identity is as unique as the identity subject. Based on this conception, I should strive for a single definition of who I am, of my identity, which will contain every significant aspect of my whole self, no matter how lengthy that definition may turn out. However, there is no single identity that can comprehensively represent the self, fully provide the outlines of the actual self, including meaningful dimensions of self-identity (since the above question is normally addressed to the identity subject). As a result, and contrary to the common belief whereby identity credentials prove who you are, a person’s identity credential doesn’t tell who they are, overall or in the absolute.

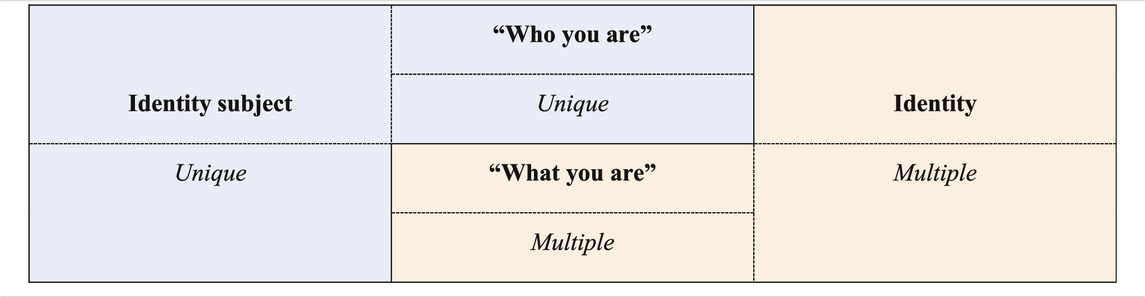

“What you are”—Instead of “Who you are,” we contend that your identity is rather “What you are.” The pronoun “What” here introduces a clear rift between the actual subject and their identity. Humans don’t naturally see themselves as a “What,” that is, as being intrinsically a collection of things, so it is clear that the “What” (identity) is of a different nature from the “You” (the identity subject.) For that reason, identity does not have to be as unique as the identity subject, and it isn’t (Table 2). Moreover, contrary to the phrase “Who I am” which may suggest that I have a single and universal identity, the phrase “What I am” is more apt to suggest the need for a context. Because I cannot reduce my whole self to things, exclusively, I will have to think of the things that are more relevant to represent such self of mine with, here and now or in any given context.

“Who you are, 2.0”—Under some circumstances, it could make sense to ask the question “Who are you?” as the adequate prompt to elicit identity. Those circumstances are not generally invoked when people paraphrase identity as being or proving “who you are,” which is why I am labeling this iteration of the phrase as version number 2.0. The predicate that identity credentials prove who you are can only be accurate with the following caveat: here, the pronoun “Who” does not refer to the first-order instance of the identity subject (i.e., for example, the embodied human being for human subjects). In fact, the question “Who are you?” becomes the equivalent of “Which one are you from among this group of entities we already have some knowledge about?”34 Put another way: “We know something about each one of this set of people or entities, and to the extent that you are one of them, tell us: which one is you? That is, who, based on the few things we know about you already”. (What we know about them, for us that is who they are). Only when the question addresses an entity that is supposed to be part of a collection of entities about whom some amount of identifying information is already known does the who-question become not only relevant but adequate. Moreover, the only optimal scenario for this is that the question is being asked by the identity authority with whom the subject has been registered or maintains an account, or by its agents or any other entity authorized to interoperate with the concerned registration system, either in order to gain a full view of the information that defines who the subject is within the concerned system or in order to verify just a piece of information needed to make a decision about the subject. Normally, only transactions that would need to be recorded for whatever reason or would require an update with the subject’s account or file should call for the who-question.

The mental model stemming from the who-question might also, to some extent, be explained by the following fact. Historically, identity verifiers have been first and foremost agents of the issuing authority (law enforcement officers, civil servants and other public administration agents, etc). For those verifiers, an identity holder is only a collection of information they keep on the actual entity holding that identity, that is, as an information record, a file, or a database entry, along with the respective contents of those artifacts, including relevant historical data such as past changes, plus whatever else is required by design, based on the purpose of the identity system at hand. To the extent that there is a tool or a mechanism (part of which is a token put in the hands of every registered individual) which enables the issuer and subsequent authorized verifiers to find and retrieve the proper record pertaining to every individual whose claims they might need to assess for veracity in order to make a decision, then such a tool or mechanism qualifies as having an identity capability, as it enables them to find “who you are” in the system or in the mass of several records—in the sense of which record is yours, which one represents you in there.

In other words, under conditions where there is no prior contact with potential identity subjects35 and where the purpose is to offer a general explanation of the notion of identity, the who-question does not work adequately. However, from the empirical standpoint of identity management,36 it works in contexts where identity subjects have first been registered; the “Who” is adequate for a system of accounts, or registered individuals bound to existing accounts by authenticating procedures. Short of that pre-requisite, and keeping it simple while still striving for accuracy, the right question translating identity from the general, theoretical standpoint of identity management is “What are you?” rather than “Who are you?” Overall, “Who you are” is either the actual you, meaning the physical life identity subject, or the registered version of you, that physical life identity subject, in a given system. Either way, “Who you are” is unique. Whereas “What you are” is multiple, depending on the context, just as is identity (Table 2).

A number of corollaries can be drawn from this. First, identity properly understood as “Who you are” (version 2.0) is built out of “What you are” which implies “potentially all what you may be”; one is made of a subset of the elements of the other. In other words, the “Who” is a function of the “What” in such a way that the scope of the “Who” is directly proportional to the wider scope of the “What” it is made of.

Second, the what-question has the advantage of dual relevance: it can be used in contexts with prior registration or existing accounts as well as (and even more appropriately so) in contexts where there are none. On the one hand, in contexts where knowledge of the subject is available prior to the current encounter, the things that will be sought after with the what-question, the things to be discovered in the instance of the subject at hand, would consist of the specific values taken in that instance by the parameters of the scheme used to form that prior knowledge about the subject. On the other hand, the what-question indicates that we already acknowledge that we are in the realm of representations, although that is the only thing we know. We know nothing, specifically, about the model of representation applicable in the context at hand—either because the subjects have never registered with us or we are completely foreign to any accounts they may have anywhere else. And in that case, the context will dictate what is relevant to defining the identity subject candidate, the parameters needed for the model of representation relevant to the entity seeking to know (and that is what happens at any registration with a new system).

And lastly, an important corollary of that distinction between mental models pertaining to “Who” and to “What” is that many identity transactions may be conducted without prior registration or setting up accounts for the identity subject. Tokens (including identity credentials used as such) are enough to handle some transactions with an individual, as those transactions don’t require reading or capturing every piece of identity information available nor do they need to be recorded but just to be carried out to conclusion at once. In the physical world for example, there are many situations where we conduct identity transactions only based on “what we are” of pertinence in the situation at hand, without the need to open an account. As a customer in a place of public accommodation, the staff might need to identify me at some point in the process, not at the level of who I am but simply at the level of what I am. For instance, I have booked an alley at a bowling facility: “customer for lane X just requested an extension for their game time and we have received the extra payment and confirmed the extension.” Or when I want to get some liquor at the store while in the United States, I show my identity credential to the cashier just so they can check my age status—that I am at least 21 and, as a consequence, they are authorized by regulations to sell me liquor (while I show an ID, here it only plays the role of a token for the proof that I am at least 21, nothing more.) No account needs to be set up or maintained in either case, because those entities do not need to care about who I am; we simply need to exchange necessary information transactionally and the business is done. In digital environments, because everything is done through exchange of information, it is even more critical to recognize the importance of the what-model and to enable related scenarios to be handled as such, as opposed to treating every transaction or interaction that requires the slightest bit of identifying information as if it pertains to the who-model.

Trust

Just like identity, trust is a concept of notable interest to both philosophy (Baier 1986; Baier 1994) and management (Barney and Hansen 1994; Wicks et al., 1999). It is a recurring theme in discussions relating to identity management systems such as the Sovrin Network, particularly with regard to the governance mechanisms that surround the technical system, which are designed to nurture trust,37 at least in part.

To begin, let us be clear about one thing. There is no sense to a human being trusting a thing like, say, a stone (and obviously, a stone can’t trust anyone, or anything, for that matter). Trust cannot apply to something that is not capable of any behavior. And something that behaves, one way or another, is either endowed with at least its own volition, or is made by or of other beings endowed with at least their own volition,38 who then enable or shape the behavior of that thing. Either way, trust may apply. In the end—and at least in the context of identity management systems—trust comes from human beings and applies to human beings, or to something human beings are involved in one way or the other. Let us consider these two orientations in turn.

The first relates to trust from the standpoint of interpersonal relationships. Human beings get trained to trust, or to reserve their trust, mainly through these relationships; that is the context where most people first experience trust, as a personal state of mind or sentiment. To trust a person, one has to make the determination or decide for oneself whether that person is worthy of trust, based on any available information deemed useful for that purpose, including their own or other people’s previous experience with the person to be trusted. Here, trust fully is a human sentiment and a subjective experience.

Drawing from that experience, to trust a person is to be inclined to believe that they will behave as we expect. However, expecting a villain to behave badly, and then they do, does not quite imply that the villain is a trusted fellow, in the way people think of a person they trust. Trust does not just result from a recurring confirmation of what is expected of someone; it implies a positive valence in that it is supposed to result in positive outcomes from the point of view of the trusting person. People we trust are not just consistent and somewhat predictable regarding the issues we trust them on, but their consistent and predictable behavior generally goes in the direction of what is sound, good or desirable from our point of view (which may not necessarily be what is good in the absolute or what is commonly good). We trust someone when we think they will consistently do what we believe is the right thing to do in a given set of circumstances, even though they might be aware of other options available for a different course of action. The implication is that if they were to have total control over something of significant interest or value to us and they know how that thing is supposed to be handled or how best to handle it (from the standpoint of that interest or value), we do not worry because we are confident that they will handle it properly. Therefore, in cases of interpersonal or direct relationships, we expect that, at least in normal circumstances, they will most likely behave in a way that aligns with our interest as long as they are aware of that interest.

At this point of the discussion, we might want to acknowledge that the notion of trust implies some amount of risk, as it transpires from Barney and Hansen (1994) definition of trust as “the mutual confidence that no party to an exchange will exploit another’s vulnerabilities.” There is an aspect of the prisoner dilemma here, facing the risk of having one’s vulnerabilities being exploited by the other party while we bet on the contrary by protecting their vulnerabilities. The same idea of risk attached to trust has been elaborated on by Nickel and Vaesen (2012).

Sovrin Network uses blockchain technology which is claimed to enable us to do away with having to rely on third parties in order to successfully conclude transactions over the network. In that sense, blockchain is reputed to enable systems that do not need to resort to trust at any point, and yet they work reliably well (Antonopoulos 2014; Werbach 2016). From the perspective of the cryptocurrency world where blockchain is foundational and algorithm reigns, trust is like a last-resort device. People would trust only because they have to—when there is no better solution available to them. That would be better if they could avoid trusting, for trusting still implies that we rely on someone else’s moral compass, consistency of character, sense of duty or sheer discretion to rise to the level of the trust we are placing in them and related expectations. And of course, there always is a risk they might not rise to the occasion.

And as part of the response to that claim about blockchain as a technology for trust-ridden systems, distinction has been made between trust and confidence whereby blockchain qualifies as “a confidence machine” (De Filippi et al., 2020) while it would be, in a way, trust-incompatible. From that angle, trust is based on a personal belief or on a value judgement and as such, it cannot be objectively assessed. There is nothing deterministic about trust, whereas confidence stems from some deterministic mechanism, the workings of which can be objectively controlled. For instance, algorithms and computation methods involved in a blockchain-based process will yield the same result every time they apply to the same inputs, all things being equal. Anyone with the adequate knowledge (which is publicly available) can check the process and verify that it has followed the appropriate methods and rules, or use available evidence to the contrary to challenge the result. Short of the latter, people can have confidence in the system and its outputs. In such a context, no one needs to trust anyone, as trusting any entity would imply that the latter has an exclusive, superior access or knowledge, which places such entity in a unique position to both attend to the system and address the concerns of the parties to the exchange as well as any issues that may arise between them.

The dimension of mutual care in Barney and Hansen (1994) definition above may imply that trust happens among equal parties (i.e., peers), or parties that can stand on equal footing. However, while trust is typically a personal sentiment, it turns out to be a human inclination that can be extended from trusting other humans to trusting human collectives, such as organizations and even institutions, as well as to trusting technical systems with less human involvement on a direct and continuous basis.

This leads us to the second orientation of trust which is applicable to “something human beings are involved in one way or the other.” Organizations, institutions and technical systems are designed by human beings to operate in a certain way. Moreover, the business and operations of those structures are also conducted with the participation of human beings who strive to cooperate with one another by following agreed-upon procedures, all of which involves their worldview or belief system shaping, in turn, their intentions and behaviors. As a result, those collective entities and systems can more or less be trusted, or not at all, depending on their features and the way the people in charge handle their business, etc.

In the context of technical systems, particularly identity management systems or infrastructures such as the Sovrin Network, we start from a place of power imbalance, as the end user is an individual facing the system. Under normal conditions of use, there is no balance, not even close, between the vulnerabilities of the individual user facing the system (including those who run it and the way it is ran) and the vulnerabilities of the system facing the user39. Differences include the fact that the system-side:

• Operates at an impersonal (institutional) level while the user operates at a personal level;

• Is a steward of user’s resources, some very personal ones at that, with no comparable reciprocal function;

• Has the capacity to adversely impact resources and interests of the user;

• Has more control, more leverage over the relationship;

As a result, one may conclude that there is a vulnerability asymmetry: no equivalence can be established between the two sides with regard to the extent of vulnerability they are exposed to in the relationship. Therefore, if trust is of any relevance here, that can only be asymmetrical trust (which would be a different concept altogether.) One party doesn’t particularly need to trust the other, only the other does—either because the former has no vulnerabilities or if they do, it doesn’t take being in a relationship with them to exploit those vulnerabilities (they are potentially available to anyone with some capacity to exploit, as it happens by computer hacking and virus attacks). In such cases, it is normal that the system-side uses other levers and takes additional steps to create and foster trust from the user-side in the relationship. Two sets of elements contribute to addressing that asymmetry:

1) Policy provisions and rules that take care of the interest of the user and which the system-side commits to abide by;40

2) The system-side is public-facing, meaning it is potentially accountable to the public, even if such accountability is voluntary or done under a regime of self-regulation.

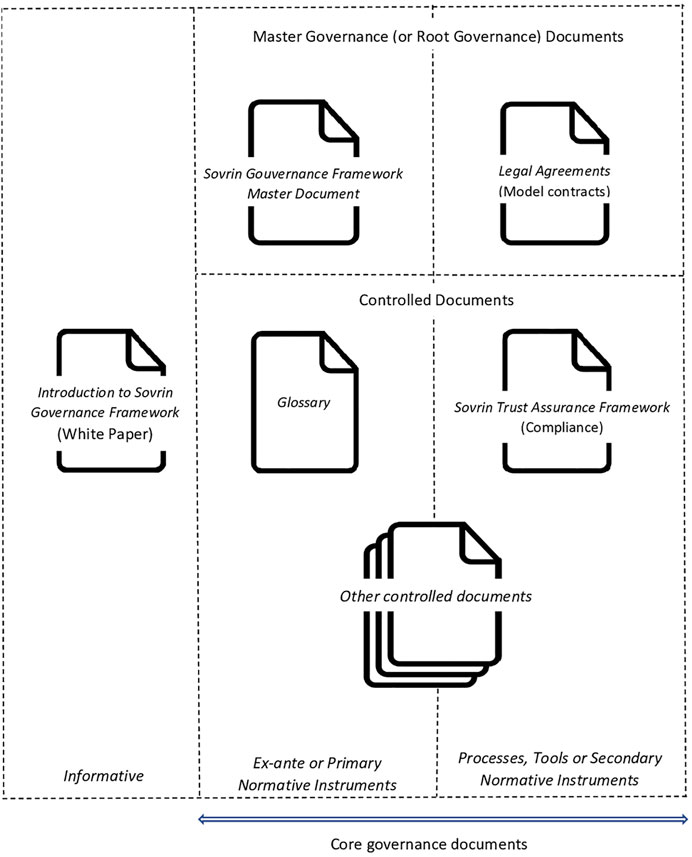

Regarding the case presented in this paper, it might be useful to note that the Sovrin Governance Framework was initially called a “Trust Framework” which might indicate that the main virtue of having these governance frameworks is to foster trust, to bring the users to trusting or, if you will, to being confident in the system as well as to bring the stakeholders to trusting each other. How?—In other words, how is the point 1) above addressed in the context of the Sovrin infrastructure?

First, by developing the SSI principles and letting the user know the values that have guided the design of the system, are infused into it, and shape its operations. The goal is to help the user recognize that those principles and underpinning values (along with the features they lend to the system) lead to outcomes that align with the user’s best interest. Second, by demonstrating through experience and over time that the system is working as designed and as expected, according to requirements that derive from its guiding principles and values.

All that is true, except that it is incomplete: the reader should read again and systematically replace the word “system” by “ecosystem,” as it isn’t just that the technical system needs to be designed (by people) following requirements and bringing about features that inspire trust. People, along with the institutions they enact, intervene on a continuous basis beyond design, from implementation to operations, including by using a host of non-technical mechanisms, in order for the system to achieve its goal and produce desired outcomes while meeting customers’ and users’ expectations. Beyond the technical system, that is what we mean by ecosystem.

Eventually, De Filippi et al. (2020) reach the same conclusion that trust needs to be brought back in blockchain-based systems, as they always involve human components. In any case, whether trust is needed or not is not a “either … or” question; we might just need to identify and distinguish the elements that lend themselves to confidence and the elements that might use trust41.

This concludes our review of the key concepts of identity, credential and trust. In the next section, we will expound on self-sovereign identity as an architectural level view of which the Sovrin Network will later be studied as a case.

Self-Sovereign Identity Architecture

Self-sovereign identity is not a particular digital identity technology. Rather, it is a vision that is captured, at best, through principles which ultimately outline a model for the technology to instantiate42. The term “sovereignty” here (which, in fact, should never be separated from “self”) does not interfere with the sovereignty of nation-states or any similar authority, in any way. The phrase expresses the need to fill a gap, which is: regardless of any external authority and whatever administrative identity they may claim to define for individuals they can control, every human being should enjoy the right to hold an identity, including the capability to make one for themselves if need be (especially if no other option is available to them). SSI doesn’t provide a particular solution as to what technology or system to use; it simply ensures that identity capability is available to anyone who needs or wants to use it, without trade-offs on their agency or autonomy, particularly in the digital realm. The result is a set of tools that enable identity management to be truly decentralized in order to empower the autonomy of the identity subject. They empower every identity owner to have control over their identifiers and their identity data, and to be able to securely share any of that with legitimate verifiers or any other party they may decide to transact with. This structurally puts them on par (making them peers) with the other party in any identity-related transaction, whoever that is, and in subsequent decision-making processes regarding the use of their identity data43. This decentralization comes with a conceptual dislocation—and a rebalancing—of authority as an exclusive source of truth and decision from the identity system toward the identity subject.

While it is true that “user-centric identity” design has already shifted the focus on the user in the recent past, it still did not give the user much autonomy and agency within the data exchange mechanism, particularly because the portability of the credentials was relatively limited as it required some level of pre-arrangement (e.g., federation) between issuers and potential relying parties, which the user has no control over. SSI further shifts toward full portability and, subsequently, toward user autonomy in their identity transactions. Through the latter, users can build relationships around their identity as it suits them. With SSI, users hold and manage their identity credentials using digital wallets, vaults or any other secure data store, and use them to prove a variety of claims to legitimate verifiers (legitimate in the eye of the claim-maker, that is, the credential holder), whenever they deem the circumstances warrant it. In this context there is no authority that is the sole source of validity for the user’s digital identity. Rather, validity stems from an interplay between the credential holder, the issuer of the credential and the cryptographic infrastructure which contributes to enable trust.

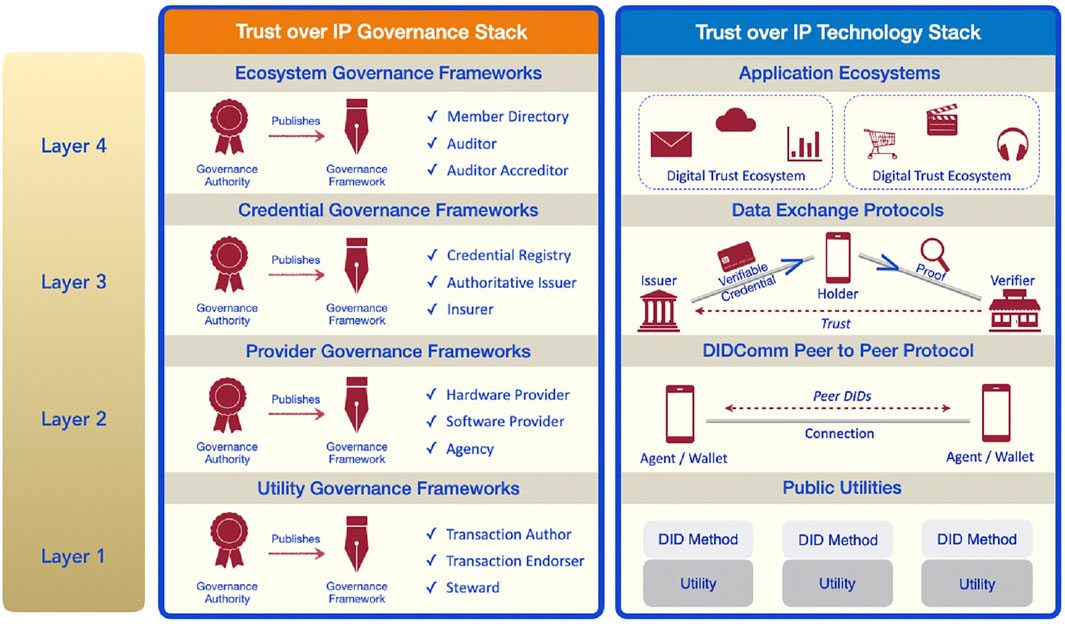

The infrastructure design that has been developed to achieve this is referred to as Trust over Internet Protocol (ToIP). In the remainder of this section, we will examine the technical aspects of the infrastructure as well as the human and social processes which are intended to enable trust over this infrastructure. The ToIP stack includes four layers (Res.ToIP, 2020; Res.GitH.0289 2019) along two dimensions which I am calling the Technology Lane and the Governance Lane. The entire architecture is structured along the four layers in the Technology Lane (the technology stack). Let us first examine the layers in the technology lane before turning to the governance lane.

The Trust Over IP Technology Stack

The technology lane of the Trust over IP architecture assembles four layers starting with the utilities layer at the bottom, each one enabling the next one at the top (Figure 1). They are all described as follows.

FIGURE 1. Architecture of the Trust over IP (ToIP) stack. (Source: Trust over IP Foundation https://trustoverip.org/).

Layer 1: Public Utilities

In the ToIP framework, “utility” is the name given to the system used to anchor a cryptographic root of trust. That system can be any type of distributed database or file system, or any other system which can fill that function (such as a distributed hash table (DHT), a blockchain or distributed ledger, etc.). The technical generic name for those utilities is “verifiable data registry” systems. The W3C defines verifiable data registry as follows44:

A role a system might perform by mediating the creation and verification of identifiers, keys, and other relevant data, such as verifiable credential schemas, revocation registries, issuer public keys, and so on, which might be required to use verifiable credentials. Some configurations might require correlatable identifiers for subjects. Example verifiable data registries include trusted databases, decentralized databases, government ID databases, and distributed ledgers. Often there is more than one type of verifiable data registry utilized in an ecosystem.

In addition, this layer includes the methods for generating and verifying decentralized identifiers (DIDs). As a W3C standard, DIDs, are a new type of globally unique identifier which is adapted to the distributed systems at the foundation of the ToIP stack. DIDs hold four core properties: they are permanent (once assigned to an entity, the DID is a persistent identifier for that entity and cannot be reassigned); resolvable (it resolves to a DID document which is a data structure describing the public keys and service endpoints necessary to engage in secure interactions with the DID subject); cryptographically verifiable (the content of the DID document enables a DID subject to prove cryptographic control over a DID); and decentralized (being cryptographically generated and verified, a DID does not require a centralized registration authority like other resource identifiers such as phone numbers, IP addresses, or domain names)45.

Layer 2: DIDComm Peer-to-Peer Protocol

DIDComm is a protocol providing a collection of secure messaging standards. These standards cryptographically enable secure communication between two software agents46 either directly edge-to-edge or via intermediate cloud agents, which is why DIDComm protocol is also referred to as agent-to-agent protocol. Sovrin identity owners, for instance, must have an agent in the cloud and one on any personal device they use for their Sovrin identity transactions. Agents are the basis for peer-to-peer relationships in the infrastructure. Credentials are not stored in the registries at Layer 1. Rather, software agents are used to provide identity owners with a place (such as a digital wallet) to hold and manage their credentials and private keys, either directly by themselves or in a delegated fashion (e.g., in the case of guardianship). Agents communicate with other agents directly for DID and credential sharing, using signed and encrypted messaging.

Layer 3: Data Exchange Protocols

Layer 3 determines how the issuer’s agent issues credentials to the credential holder, how the credential verifier requests information from the credential holder, and how the credential holder presents a proof of information from their credentials that the verifier can trust. However, before all of this happens, the issuer must register a credential definition and a public DID to the data registry so that a verifier can look up the definition and collect the cryptographic bits that will enable the verifier to ascertain the fidelity47 and the provenance of the credential48. The issuer may also add revocation registries and schema definitions to the utilities in Layer 1 which are used in the credential exchange. Layer 3 is where humans use the system and create the trusted interactions that are only technically enabled in the first two layers.

Layer 4: Application Ecosystems