Abstract

We present a survey to evaluate crypto-political, crypto-economic, and crypto-governance sentiment in people who are part of a blockchain ecosystem. Based on 3,710 survey responses, we describe their beliefs, attitudes, and modes of participation in crypto and investigate how self-reported political affiliation and blockchain ecosystem affiliation are associated with these. We observed polarization in questions on perceptions of the distribution of economic power, personal attitudes towards crypto, normative beliefs about the distribution of power in governance, and external regulation of blockchain technologies. Differences in political self-identification correlated with opinions on economic fairness, gender equity, decision-making power and how to obtain favorable regulation, while blockchain affiliation correlated with opinions on governance and regulation of crypto and respondents’ semantic conception of crypto and personal goals for their involvement. We also find that a theory-driven constructed political axis is supported by the data and investigate the possibility of other groupings of respondents or beliefs arising from the data.

1 Introduction

As blockchain technology has evolved over more than a decade, cryptocurrencies and crypto-economic systems have had a growing impact on the world. Millions of people have involved themselves in crypto1: as of 2021, around 15 percent of American adults have reported owning cryptocurrency (Perrin, 2021), and many other countries have even higher adoption rates (Buchholz, 2021). The past few years have seen the growth of decentralized apps and the crypto startup industry. Correspondingly, governments are beginning to take regulatory actions. Also, even as blockchain ecosystems move towards less computationally-intensive consensus mechanisms, the ongoing environmental impact of blockchain use is huge.

Given the impact of crypto-economic activity on individuals and on shared resources, it is increasingly important to understand how its users are relating to the technology. While the hard data of cryptocurrency transactions and account balances is often publicly available by design, users’ motivations for engaging with crypto are more opaque. There is little existing data on the stated beliefs or attitudes of the variety of people using blockchain technologies. What do blockchain users believe about the economic, political, and social relevance of crypto? While there has been attention to the attitudes of the general population towards cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology (Perrin, 2021; Global State of Crypto, 2022), there is also a need to understand the beliefs of active participants of blockchain ecosystems.

Just as technologies such as the internet have been shaped by and in turn shaped social, political, and regulatory landscapes, so might crypto. But a technology is a tool used by a person: it embodies its user’s intent and mediates its user’s interactions with others and the world. Understanding who is using crypto, how they are using it, and why they are using it the way that they are is essential for understanding how it interacts with existing institutions and other social technologies. In particular, the question of governance of blockchain technology is fundamental to the theory and ideology of blockchain. The place of governance in crypto can be traced back to its earliest roots (Brunton, 2020), and remains in active tension today (Reijers et al., 2021). Understanding the motivations of its adherents becomes ever more critical as developments in crypto stretch existing organizational and institutional theories (Allen, 2019; Kavanagh and Ennis, 2020; Filippi and Santolini, 2022).

What do blockchain ecosystem participants believe about how the technology is being—or should be—developed, used, and regulated? Are there discrete types of crypto contributors, or is there a spectrum of beliefs? What specific beliefs are most relevant in distinguishing respondents between types or along axes? This work is a first step in the development of a framework for thinking about this spectrum or grouping of beliefs in crypto.

We report the results of a large-scale survey of participants in the blockchain economy. The survey was designed to shed light on respondents’ socioeconomic and sociopolitical beliefs relating to crypto, economic modes of engagement with crypto, and attitudes towards governance of blockchain technology. We describe the distributions of these responses and their relationships to self-reported political ideology and specific crypto ecosystems such as Bitcoin and Ethereum.

We also evaluate the survey instrument itself: Are the questions able to assess distinct and relevant facets of beliefs? Can we identify underlying factors which describe broader groupings of beliefs? Using factor analysis methods, we find that a political axis and corresponding typology, informed by the Pew Research Center’s Political Typology Quiz, meaningfully describes variation between respondents.

2 Background

While there is no existing political theory of crypto per se, there are substantial ethnographic studies of crypto communities (and related digital communities) that address the political dimensions of crypto. For example, ethnographic studies have informed the creation of a proposed political typology of blockchain projects (Husain et al., 2020), reflecting earlier ideas on the “intrinsic” political values of technical artifacts (Winner, 1980). In this vein, cryptocurrencies have been characterized as realizations of crypto-anarchist values such as privacy and autonomy (Chohan, 2017; Beltramini, 2021), following in the footsteps of earlier cypherpunk writings (Hughes, 1993; May 1994) as well as the original Bitcoin whitepaper (Nakamoto, 2008). Other ethnographies have described issues of on- and off-chain governance (Filippi and Loveluck, 2016) and the political motivations and cultural context of projects such as Bitcoin (Golumbia, 2016) and Ethereum (Brody and Couture, 2021).

A previous industry survey, conducted by CoinDesk in 2018, contained several questions related to politics and governance (Bauerle and Ryan, 2018; Ryan, 2018), though the questions focused more specifically on individual projects and topical questions such as reactions to SEC rulings on the securitization status of Ethereum.

Distinct from questions about political values, governance of blockchain projects—including the relationship between blockchains and traditional governments—is one of the most salient and polarizing questions in crypto, one that has led to the creation, forking, and dissolution of many projects. While we cannot recount all the major positions here (some of which are reflected in the survey itself; see “Methodology”), there is a broad distinction between approaches that emphasize on-chain governance and those that emphasize off-chain governance. A number of academic analyses have studied these different approaches to blockchain governance (Reijers et al., 2016; Zwitter and Hazenberg, 2020; Hofman et al., 2021; Honkanen et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; van Pelt et al., 2021; Alston et al., 2022), along with a vastly greater number of industry manifestos and opinion pieces (Szabo, 1996; Zamfir, 2019).

3 Methodology

3.1 Survey questions

The survey consists of 19 questions related to respondents’ crypto-related beliefs and activities, with three types of questions interspersed: those eliciting opinions about the political dimensions of crypto activity (“crypto-political”), those eliciting economics opinions (“crypto-economic”), and those eliciting attitudes about the governance of crypto projects (“crypto-governance”). All questions were multiple choice, with 2–4 possible selections, and the respondent could opt not to answer (Supplementary Table S1).

The survey questions and provided choices included both a formal portion drawing from existing political survey instruments and a more exploratory portion intended to elicit beliefs relevant to a general crypto-political typology. In particular, a few of the questions selected (Q11–13, Q15, Q19), were based on questions from Pew’s Political Typology Quiz (Nadeem, 2021) and intended to relate to political sentiment. Other questions (e.g., Q1, Q17) were developed in collaboration with a number of community members in crypto, drawing on the culture, memes, and references common in crypto. Altogether, the content was designed to elicit respondents’ primary modes of economic engagement with crypto, their political sentiment, and opinions as to how crypto communities themselves should be governed.

3.2 Construction of political “types” and identification of “axes” of belief

Our choice to identify separate “axes” of economic, political, and governance beliefs were based on discussion with community members and in analogy to existing classifications such as the traditional “left-right” political axis. For one of these, the political axis, we also leveraged our study design to group and relate questions more directly by defining a continuous construct intended to assess respondents’ crypto-political leanings. We identified a subset of questions as most relevant to political orientation, and computed a score for each participant by summing the responses to these questions (coded with values in the range (–1, 2) as described in Supplementary Table S1) in analogy to the Pew methodology (Nadeem, 2021). The lowest and highest scores on this political “axis” were designed to highlight extreme positions of collectivist and anarcho-capitalist approaches to using blockchain technology. Five discrete types were defined by thresholds in the score according to Supplementary Table S2: Crypto-anarcho-capitalist, crypto-libertarian, centrist, crypto-communitarian, and crypto-leftist; these types were developed both with definitions from the Pew typologies and with input from the community.

3.3 Recruitment

We relied on a convenience (self-selected) sample of participants in the crypto community. Participants were recruited by distributing the survey through blockchain-focused forums and listservs, conferences (LisCon and ETHDenver), social media posts, and articles published on blockchain-focused news sites.

We motivated voluntary participant engagement with two strategies. We presented the survey as a quiz that assigned respondents one out of an entertaining typology of “types” on the basis of their responses (“crypto-leftist,” “cryptopunk,” etc.) immediately upon completion of the survey. Stylized as “factions”, the crypto-political types corresponded to the political types we defined based on the Pew typology, while the crypto-economic and crypto-governance types were constructed by using thresholds to partition respondents into five ad hoc types (for more detail, see of the Supplementary Section S1.1). We also incentivized survey completion with the opportunity to receive a non-fungible token (NFT) corresponding to their assigned “type”, contingent upon their provision of a valid Ethereum wallet address or ENS name.

3.4 Analysis

To survey the overall landscape of crypto-political beliefs, we observed the distribution of choices selected by respondents. We aggregated these responses for each question, including the null response of no choice selected, and computed the margins of error for a 95% confidence interval, assuming a random sample of the population.

To investigate how political self-identification and participation in specific blockchain ecosystems related to beliefs, we grouped participants by their responses to the corresponding questions. We then determined which questions displayed a statistically significant difference in the distribution of responses between these groups.

We also wanted to understand which questions were most meaningful in differentiating respondents. To this end, we first performed a check on the extent to which each question measured a distinct belief by computing the correlation between responses to different questions as Cramer’s V (a version of Pearson’s chi-squared statistic scaled to provide a measure of association). Then we used principal component analysis (PCA) to identify which of the 48 choices provided across 17 questions explained the most variance between respondents. Specifically, we looked at the component loading for each feature, i.e., contribution to the first principal component.

For use with PCA, we normalized the feature data (shifted to a mean of 0 with unit variance). Note that for questions where only two choices were provided, the alternative answer contributed with equal magnitude (though opposite sign). We omitted questions 2 and 19, relating to specific blockchain ecosystems. We also omitted answers from respondents that did not answer all questions.

We also wished to evaluate to what extent our crypto-political types, delineated from the political score we defined, corresponded with patterns in beliefs across respondents. From the PCA results, we can identify to what extent the assigned types or classes directly correlate with any of the first few components.

4 Results

4.1 Responses and respondents

Between 27 September 2021 and 4 March 2022, the survey received 3,710 responses. In 3,418 (92%) of these, all questions were answered. For questions presented to all respondents, the percentage of respondents who chose not to answer each question was between 0.5% and 1.5% across all questions. The survey took on average 8 min and 40 s to complete.

4.2 Responses to questions: Political, economic, and governance attitudes

Overall, respondents were varied in their perceptions of the distribution of economic power in crypto and their personal attitudes towards crypto. They were also split between the most common responses to two questions on the distribution of power in governance of crypto. There was somewhat more agreement on broad beliefs towards external regulation of crypto, though respondents disagreed on some of the specifics and in matters of degree. The largest majorities were observed in questions relating to the social implications of crypto.

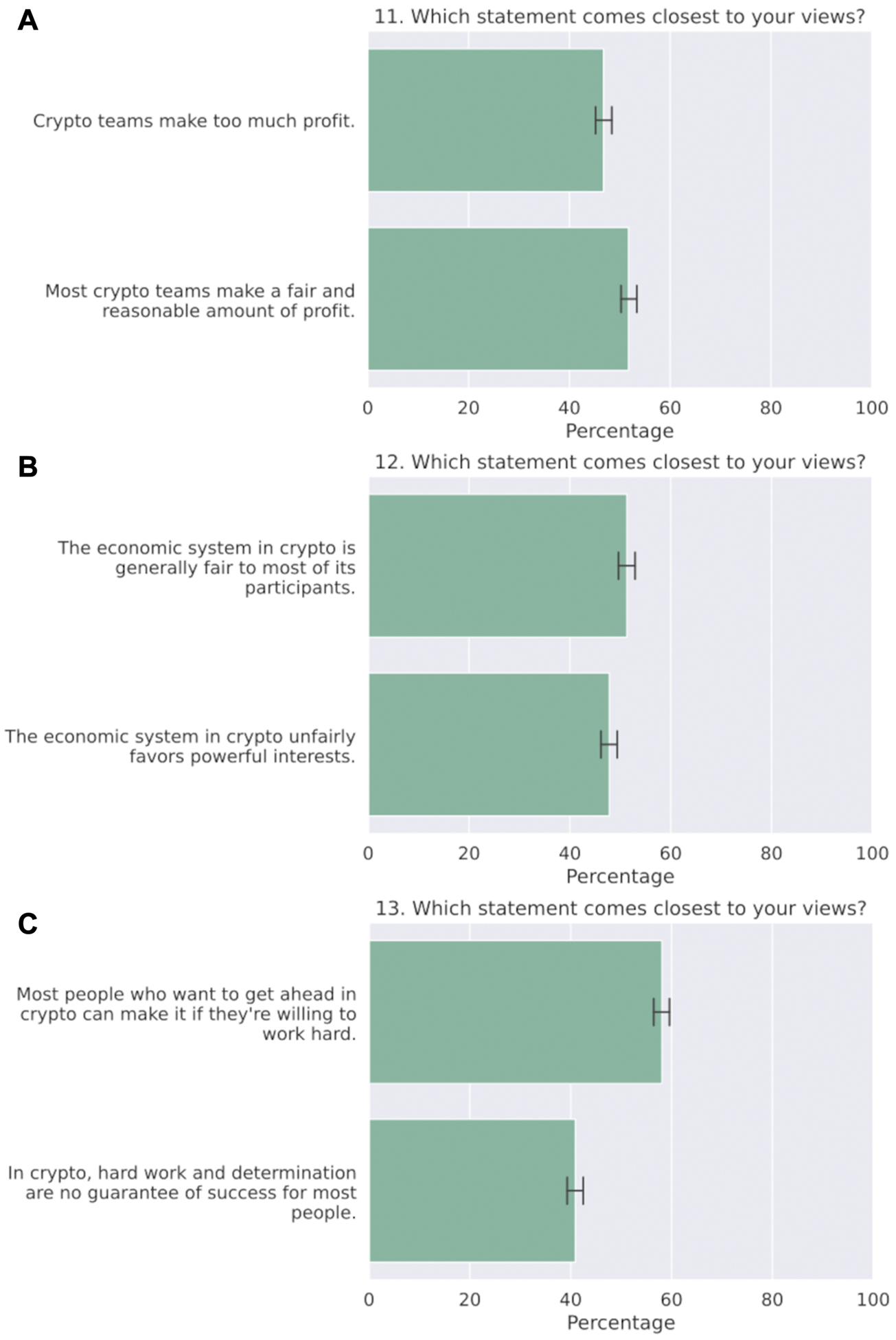

Perceptions of the distribution of economic power in crypto were closely split between the two choices provided for each question (Figure 1). By a few percentage points, a slightly higher proportion of respondents believed that most crypto teams make “a fair and reasonable amount of profit” rather than “too much profit” (Q11, Figure 1A) and that the economic system in crypto “is generally fair to most of its participants” rather than “unfairly favors powerful interests” (Q12, Figure 1B). A majority (58%) believed that “most people who want to get ahead in crypto can make it if they’re willing to work hard” (Q13, Figure 1C).

FIGURE 1

Responses to (A) question 11 (B) question 12, and (C) question 13 on perceptions of the distribution of economic power in crypto, with 95% confidence intervals. Though optimistic beliefs about the current state of crypto-economics were slightly more prevalent, dissatisfaction with the fair distribution and attainability of crypto-economic wealth was nearly as frequent.

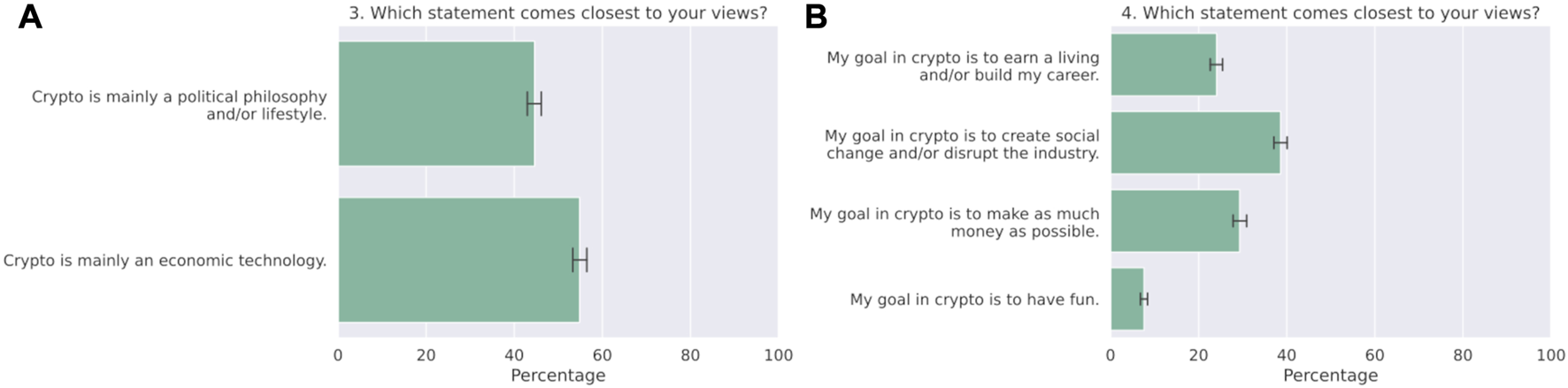

Personal attitudes towards crypto were also diverse (Figure 2). Respondents were divided on whether they regarded crypto as “mainly a political philosophy and/or lifestyle” or “mainly an economic technology”, with a slight majority favoring the latter (Q3, Figure 2A). There was no majority in respondents’ goals for their own involvement in crypto: the most common goal was “to create social change and/or disrupt the industry” (39%), followed by “to make as much money as possible” (29%) (Q4, Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2

Responses to (A) question 3 and (B) question 4 on personal attitudes towards blockchain, with 95% confidence intervals. Together, these responses show that both a desire for sociopolitical change and an interest in personal financial gain were common factors in participants’ interest in blockchain technologies.

Normative beliefs about the distribution of power in governance of crypto appear to be in some tension (Figure 3). Most respondents favored a “crypto-native” approach to the governance of crypto, with 45% believing that “most or all cryptogovernance should be on-chain” and 30% believing “crypto does not need (human) governance” (Q5, Figure 3A). However, a majority of respondents believed that “a wide variety of on- and off-chain stakeholders” should have decision-making power over a blockchain (though the next most common response was “the token holders and/or node operators, i.e., voters, as determined by the protocol”) (Q16, Figure 3B). Note that while the most common responses to each of these questions are not incompatible, their coexistence indicates a possible tension in the community between maximizing on-chain governance and empowering off-chain stakeholders.

FIGURE 3

Responses to (A) question 5 and (B) question 16 on blockchain governance, with 95% confidence intervals.

Regarding external regulation of blockchain technologies, respondents were somewhat more consistent (Figure 4). A majority of respondents believed at least some good will come of government regulation of crypto, though nearly 40% asserted that “government regulation of crypto will almost always do more harm than good” (Q7, Figure 4A). In line with the above, when asked what the most important thing the crypto community can do to get more favorable regulation of cryptocurrencies from national governments, a plurality of respondents sought a cooperative relationship with government, choosing to “work hand-in-hand with regulators to identify a solution that works for both government and industry,” versus adopting an evasive approach to “adapt our technology and practices in order to minimize potential conflicts with the law” or even an antagonistic one to “mount a public pressure campaign on politicians” or to “keep doing what we’re doing, legal or not” (Q14, Figure 4B). Also, more than three-quarters of respondents believed that “having a central bank run a cryptocurrency is a bad idea” (Q8). Overall, though a majority of respondents were willing to accept or even collaborate on regulation, large minorities strongly disagreed, and distaste for direct government involvement in implementations of crypto technology was common.

FIGURE 4

Responses to (A) question 7 and (B) question 14 on external regulation of blockchain technologies, with 95% confidence intervals.

On the social implications of crypto, most respondents were in agreement, believing that blockchain and DeFi are “beneficial technologies that, on balance, will help most members of society” (Q10). Even so, more than a quarter of respondents believed that crypto “has a gender problem” (Q15). Also, around a quarter of respondents indicated privacy is “the most important feature of blockchain and crypto” (Q6).

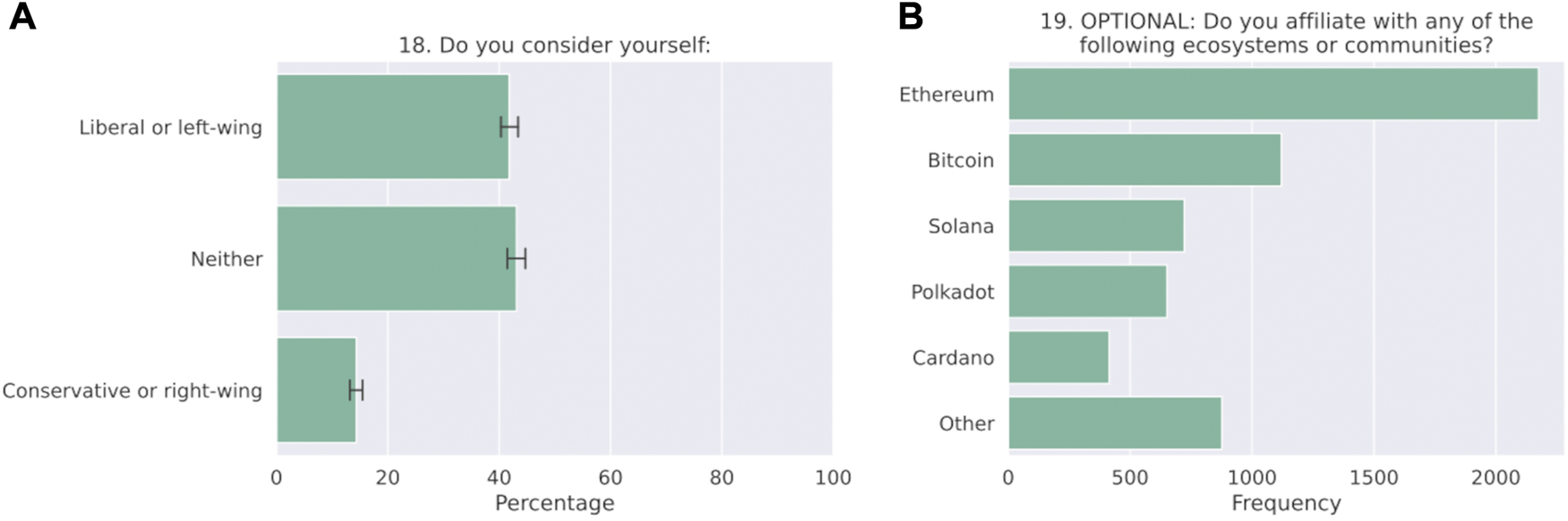

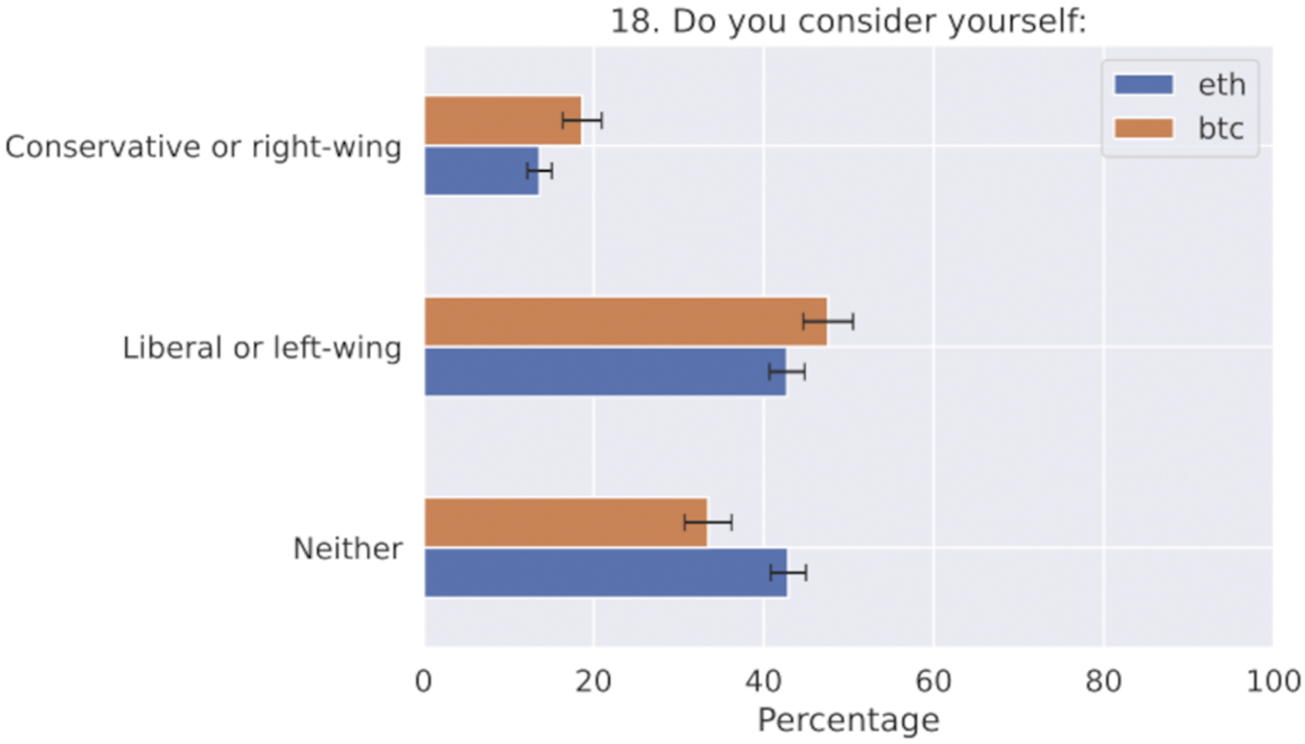

We asked two additional questions on political orientation and blockchain ecosystem affiliation (Figure 5). Only 14 percent of respondents considered themselves “conservative or right-wing” (532 respondents) with the remaining participants split equally (with no statistically significant difference) between “liberal or left-wing” (1,550) and “neither” (1,599; Q18, Figure 5A). Nearly all participants (97%) stated an affiliation with at least one blockchain ecosystem or community (Q19, Figure 5B), supporting our use of this dataset to focus on users of blockchain technology (rather than the general public). In particular, of the 3,591 respondents who indicated affiliation with at least one blockchain, 2,175 (61%) selected affiliation with Ethereum and 1,120 (31%) with Bitcoin (Figure 5B). Note that these are not mutually exclusive groups (789 indicated affiliation with both); furthermore, though a majority of respondents only specified one affiliation, less than a quarter believe that “there is one (layer 1) blockchain that is the best” (Q1). In the following two subsections, we discuss the relation of these distributions with respondents’ beliefs in more depth.

FIGURE 5

Responses to (A) question 18 on political orientation and (B) question 19 on blockchain ecosystem affiliations, with 95% confidence intervals.

The distribution of responses for the questions not covered in this section are included in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Figures S1–S4).

4.3 Differences between respondents by self-reported political orientation

To examine the differences in opinion between the left-of-center, right-of-center, and unaligned groups, we compared the distribution of answers selected by respondents affiliated with each group (Q18). We found that perceptions of economic fairness and gender equity elicited the clearest differences between the three political orientation groups, with economic fairness especially differentiating left-of-center respondents from the other two groups. Beliefs about governance, regulation, and personal goals in crypto differentiated right-of-center respondents from the other two groups. Differences between political orientation groups were ubiquitous: all but one question had at least one statistically significant difference between the responses groups.

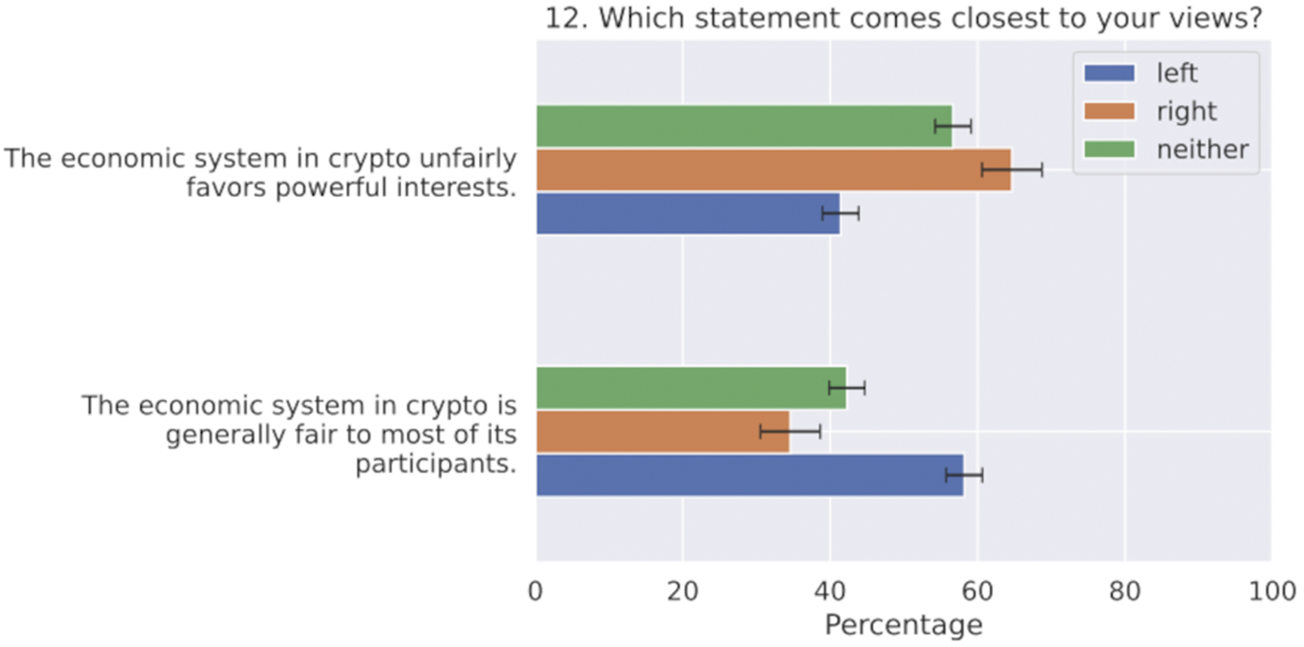

The economic fairness questions (Q11, Q12, and Q13) were among those with the greatest differentiation between the three groups. Somewhat surprisingly, unlike non-aligned and right-of-center respondents, a majority of left-of-center respondents believe that “most crypto teams make a fair and reasonable amount of profit” (Q11) and “the economic system in crypto is generally fair to most of its participants” (Q12, Figure 6). Though a majority of both right-of-center and non-aligned respondents believed instead that “the economic system in crypto unfairly favors powerful interests”, right-of-center respondents were more likely than non-aligned respondents to choose this answer (Q12). However, left-of-center respondents were more likely than right-of-center or non-aligned respondents to believe that “hard work and determination are no guarantees of success” in crypto (Q13).

FIGURE 6

Responses, grouped by self-reported political affiliation, to question 12 on crypto-economic fairness, with 95% confidence intervals. Taken together with questions 11 and 13, this distribution shows that left-of-center respondents overall held a different set of beliefs about wealth distribution and economic opportunity than other respondents.

Question 12 was one of three questions for which all three groups had a statistically different distribution of responses. Another was on gender equity: Right-of-center respondents were least likely to believe “crypto has a gender problem,” non-aligned respondents somewhat more likely, and left-of-center respondents most likely, with about half of left-of-center respondents selecting this answer (Q15). This spread shows that self-reported political alignment relates to not only economic but also social issues in the use of blockchain technology.

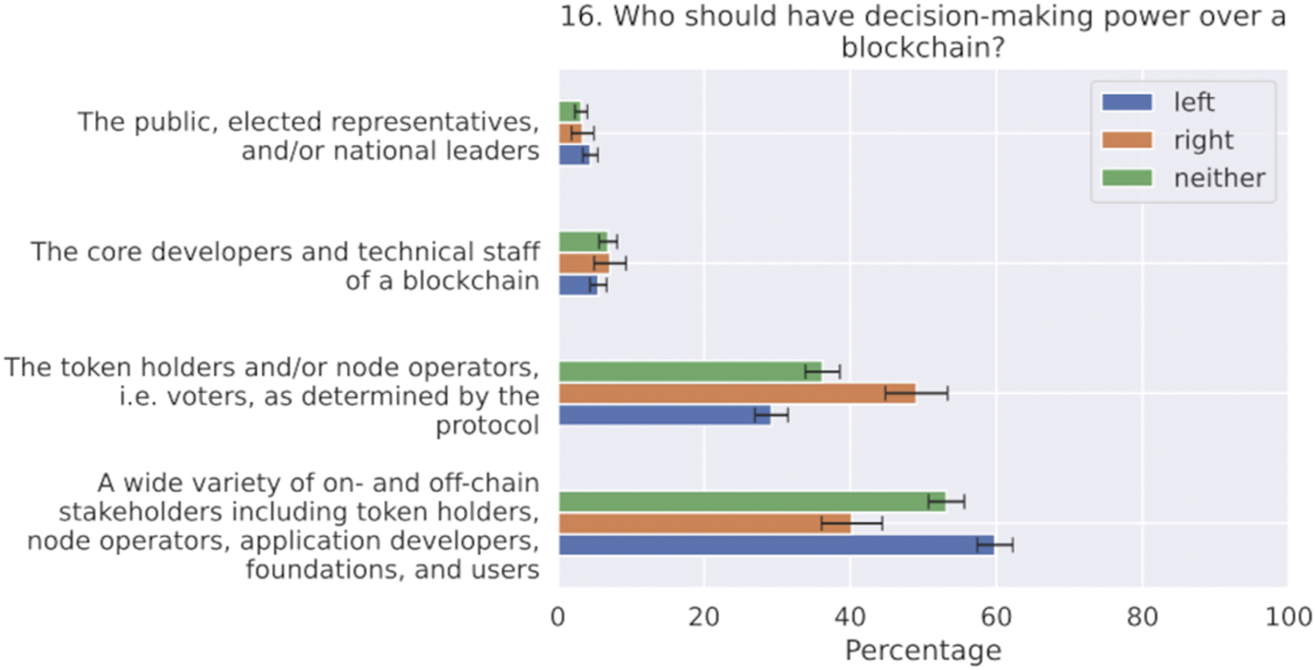

Differences also arose between the groups in the most common answer to questions on decision-making power and how to obtain favorable regulation. When asked who should hold decision-making power over a blockchain, right-of-center respondents were more likely to choose “the token holders and/or node operators” than “a wide variety of on- and off-chain stakeholders”; the reverse was true for left-of-center and non-aligned respondents, with left-of-center respondents more likely than other respondents to choose a variety of stakeholders (Q16, Figure 7). Concerning how to obtain favorable regulation, left-of-center and non-aligned respondents were most likely to choose “work hand-in-hand with regulators” out of the available choices, and more likely to do so than right-of-center respondents; In contrast, right-of-center respondents were, within confidence intervals, evenly split between three of the four available choices (Q14).

FIGURE 7

Responses, grouped by self-reported political affiliation, to question 16 on decision-making power, with 95% confidence intervals. Together with question 14, this distribution indicates that right-of-center respondents were more likely than other respondents to hold beliefs aligned with minimizing external influence on blockchain governance and development.

Other statistically significant differences occurred in the distribution of responses, where one of the three groups differed from the other two. Right-of-center respondents were most likely to choose “make as much money as possible” as their goal and less likely to select “create social change and/or disrupt the industry”; the reverse was true for left-of-center and non-aligned respondents (Q4). However, left-of-center respondents were less likely than others to believe crypto needs to prioritize “building art and community” to grow (Q9). Also, a smaller proportion of left-of-center respondents than other respondents believed that privacy is “the most important feature of blockchain” (Q6). Left-of-center respondents were less likely to believe that “crypto does not need (human) governance,” while non-aligned respondents were less likely to believe “however crypto governs itself, it should also be regulated by the government” (Q5). Left-of-center respondents were also more polarized on government regulation: they were less likely to believe it “can do some good,” and more likely to believe it is either “critical to protect the public interest” or “will always do more harm than good” (Q7).

4.4 Differences between respondents by Bitcoin and Ethereum affiliation

At present, dynamics in the crypto community are largely driven by actors in two ecosystems: Bitcoin and Ethereum. To examine differences in opinion between the 61% of respondents affiliated with Ethereum and the 31% (non-exclusive) affiliated with Bitcoin, we compared the distribution of answers selected by respondents affiliated with each of the two blockchains. We found an overall quite similar distribution of responses regardless of affiliation, with a few statistically significant differences arising in beliefs about cryptogovernance, the semantics of the term crypto, personal goals in crypto, and stated political orientation.

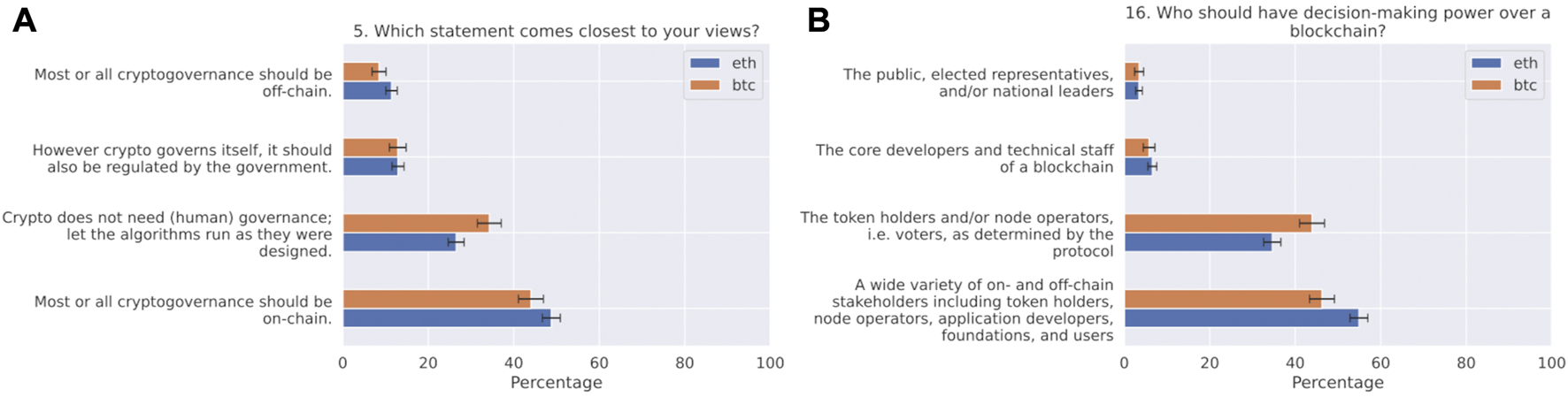

Governance and regulation of crypto were a key topic distinguishing Bitcoin affiliates from Ethereum affiliates (Figure 8). Bitcoin affiliation was associated with a higher likelihood of believing that “crypto does not need (human) governance” (Q5, Figure 8A) and that “token holders and/or node operators” should have decision-making power over a blockchain, whereas Ethereum was associated with “a wide variety of on- and off-chain stakeholders” (Q16, Figure 8B). Somewhat surprisingly, Bitcoin affiliation was also associated with a higher likelihood of believing that government regulation of crypto “can do some good” (Q7), although there was no statistically significant difference in opinions on how to obtain favorable regulation (Q14). Thus, it appears that Bitcoin affiliation is associated with a higher rate of wanting to maximize on-chain governance but also of tolerance of external regulation, perhaps in particular that which “can help force blockchains to become more decentralized,” as is included in the wording of question 7.

FIGURE 8

Responses, grouped by blockchain affiliation, to (A) question 5 and (B) question 16 on blockchain governance, with 95% confidence intervals. These distributions indicate that Bitcoin affiliates were more likely to favor a narrow definition of governance and its participants.

Respondents’ semantic conception of crypto and their personal goals for their involvement also had some relation to blockchain affiliation: Bitcoin affiliation was associated with a higher likelihood of believing “crypto is mainly an economic technology” (Q3) and identifying with the statement “my goal in crypto is to make as much money as possible” (Q4). Ethereum affiliation was associated with a higher likelihood of believing that “the economic system in crypto unfairly favors powerful interests” (Q12) and that “crypto has a gender problem” (Q15).

For question 18 on political orientation, Bitcoin affiliation correlated with a higher likelihood of selecting “conservative or right-wing” and lower likelihood of selecting “neither” (Figure 9). There was no statistically significant difference between the proportions of respondents who chose “liberal or left-wing”. Given that we were interested in analyzing blockchain affiliation separately from stated political orientation, we additionally checked for the strength of association between Q18 and a reduced version of Q19 with the options “Bitcoin”, “Ethereum”, and “Neither” (not mutually exclusive). Cramer’s V was low (less than 0.15) for all combinations of responses, indicating at most very weak association between the two questions (Supplementary Figure S5). This gives us confidence that Bitcoin and Ethereum affiliation were not strongly associated with stated political orientation.

FIGURE 9

Responses, grouped by blockchain affiliation, to question 18 on self-reported political affiliation, with 95% confidence intervals. While there was a statistically significant difference between affiliates of the two blockchains in identifying as right-of-center or non-aligned, Cramer’s V indicates that the strength of association between blockchain affiliation and political orientation was low.

4.5 Validation of survey instrument

To assess any correlations between responses to different questions, we computed the correlation matrix for all pairs of questions (Supplementary Figure S6). Of the 153 unique pairs, most showed little if any association (V < 0.1); the strength of association was weak for 52 questions (0.1≤V < 0.3), and one question pair related to wealth distribution (Q11–Q12) showed a moderate strength of association (0.33). The prevalence of weak or no association between distinct questions supports our assertion that each question addresses a distinct facet of a respondent’s beliefs or actions. This allows us to assess the relative importance of the specific statements provided in the answer choices to explain differences between respondents.

4.6 Feature selection and factor analysis

To identify the beliefs which most contributed to explaining variance between respondents and to test our hypothesis, we computed the PCA vectors for individual choices (features) and examined the first principal component. Beliefs above a threshold of magnitude 0.18, corresponding to the loading each response would have if all questions contributed equally to the component, were labeled as important. The features with the largest contributions to the first principal component were the following (listed in descending order of importance).

- “The economic system in crypto unfairly favors powerful interests.” (Q12)

- “Crypto has a gender problem.” (Q15)

- “Government regulation of crypto will almost always do more harm than good.” (Q7)

- “[I consider myself] liberal or left-wing.” (Q18)

- “Crypto teams make too much profit.” (Q11)

- “In crypto, hard work and determination are no guarantee of success for most people.” (Q13)

- “However crypto governs itself, it should also be regulated by the government.” (Q5)

- “Blockchain and DeFi are predatory technologies that, on balance, will harm most members of society.” (Q10)

All three questions relating to wealth distribution and economic fairness (Q11–13) contributed more to explaining variance than most other questions. Polarized opinions on government regulation (Q5 and Q7) and one specific political affiliation (Q18) also featured here. Altogether, 5 of the 8 questions that we had coded as defining an axis of political belief had a large contribution to this leading component.

The same analysis can be done for the remaining principal components. The features with the largest component loading for the next two principal components are “Privacy is the most important feature of blockchain and crypto” (Q6) for the second principal component and “Crypto is mainly a political philosophy and/or lifestyle” (Q3) for the third. These choices, and their corresponding questions, are therefore among the more salient in explaining variance between respondents.

Altogether, however, the variance explained by only the first few components was relatively low (21% for the first three components) and less than 10% was explained by the first component alone. Taken together with weak associations between questions as described in Supplementary Section S4.5, this implies that the number of latent variables required to describe respondents’ beliefs is large. Indeed, factor analysis using PCA and feature agglomeration yielded a null result, meaning that features did not cluster into a few interpretable groupings (see the Supplementary Section S1.3). Even so, we find that the first principal component axis corroborates a theory-first constructed axis, as described in the following section.

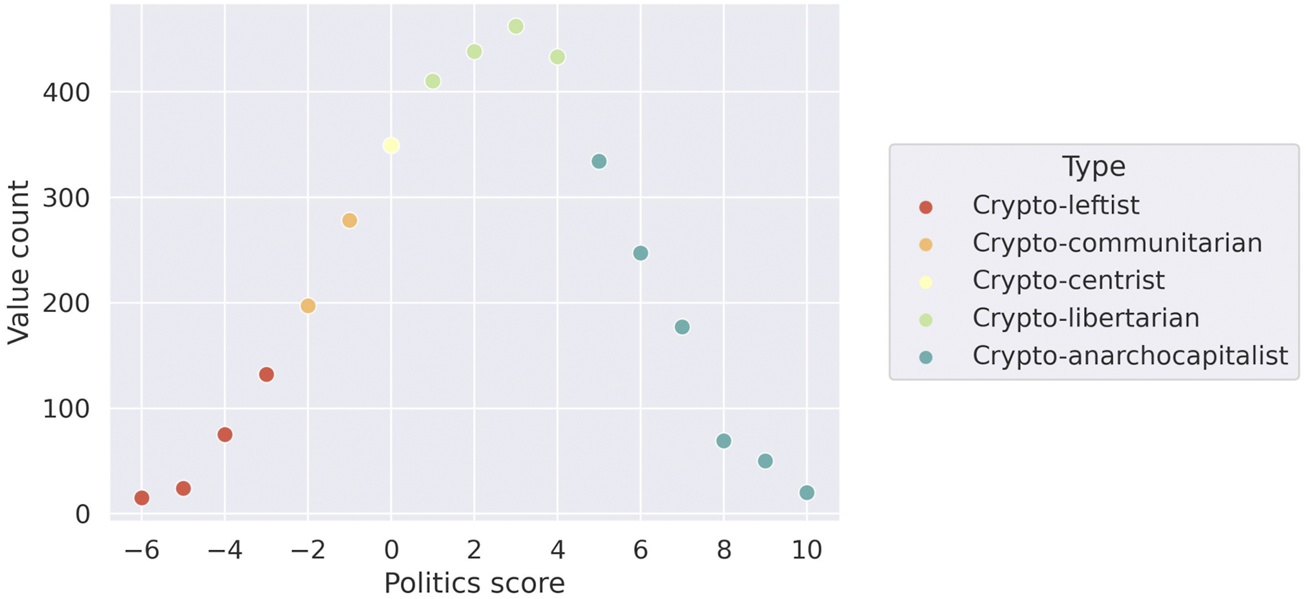

4.7 Validation of constructed crypto-political axis

For each respondent, a political score was calculated using the values in Supplementary Table S1 and a type was assigned according to the score thresholds described in Supplementary Table S2. The feature selection and factor analysis results can be used to evaluate the validity of this constructed crypto-political axis.

The distribution of scores and types assigned to participants who completed the survey is shown in Figure 10. On the left-of-center side, 20% of respondents were identified as “crypto-communitarian” or “crypto-leftist”, while 9% of respondents were given the “crypto-centrist” label. The most commonly assigned type was the “crypto-libertarian” types, with nearly half of respondents receiving this designation; overall, right-of-center types (“crypto-libertarian” and “crypto-anarcho-capitalist”) dominated with 71% of respondents. This distribution is unimodal, low skewness, and centered around the median possible score. However, because the range of possible scores was not centered around zero, we find that a majority of respondents were labeled as crypto-politically “right-of-center”. For a summary of how this distribution differed with political self-identification and blockchain affiliation, of the Supplementary Section S1.2.

FIGURE 10

Distribution of assigned crypto-political scores and corresponding sentiment types. Despite a 14% minority of respondents identifying as ideologically conservative or right-wing, our measure placed 71% in the right-of-center libertarian and anarchocapitalist categories.

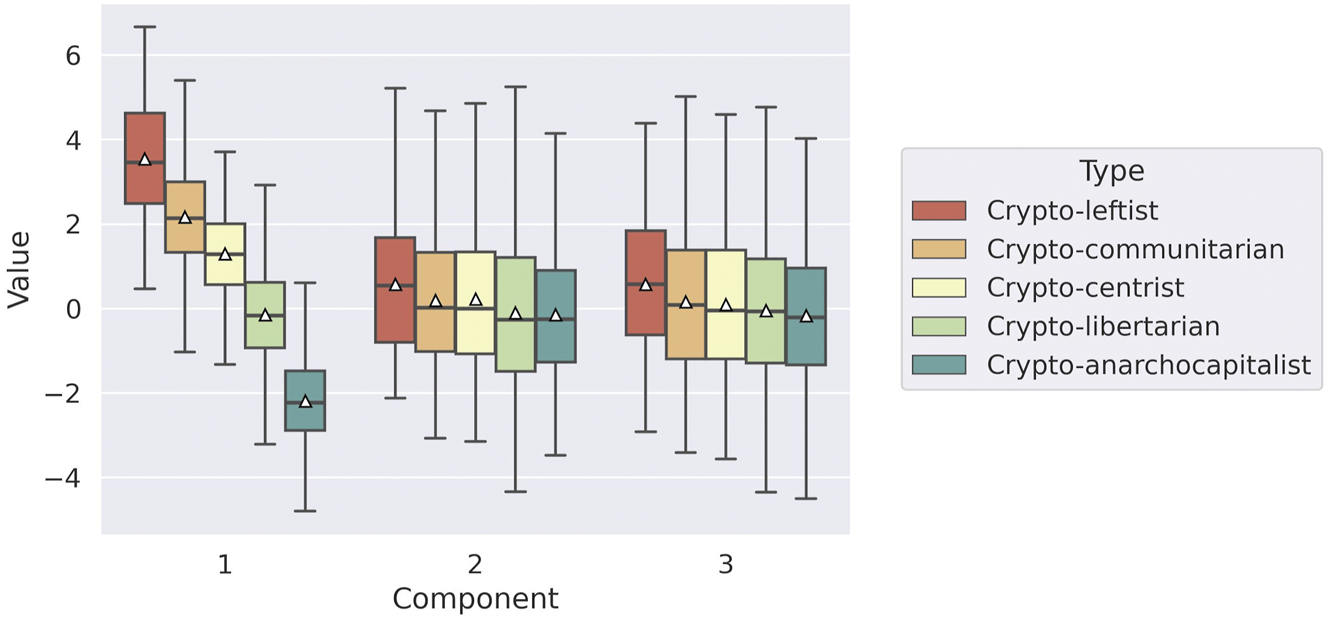

Partitioning the respondents by the types we identified for them, and plotting them in the first three PCA components, we find, again, that the first principal component succeeds at capturing the political dimension of respondent variation, while the next two components are less informative (Figure 11). The low overlap between the interquartile ranges for adjacent types indicates that the continuous construct we defined and the defined types which discretize it help to explain differences between respondents’ beliefs. Thus, the constructed political axis seems to reflect true variation in the population and may be of use in future work characterizing the ideological structure of the crypto community.

FIGURE 11

Box plots showing the distribution of values for each political type along each of the first three principal components produced by PCA, with the mean scores indicated by a white triangle. There is essentially no overlap between crypto-leftist and crypto-ancap types for component 0.

5 Discussion

Though optimistic beliefs about the current state of cryptoeconomics were slightly more prevalent, the survey responses indicate nearly as much dissatisfaction with the fair distribution and attainability of cryptoeconomic wealth. Both a desire for sociopolitical change and an interest in personal financial gain were common factors in participants’ interest in blockchain technologies. Respondents generally were optimistic about the social potential of blockchain technology, with some having reservations about its gender equity and some focusing on its privacy implications. Overall, though a majority of respondents were willing to accept or even collaborate on regulation, large minorities strongly disagreed, and distaste for direct government involvement in implementations of crypto technology was common.

Despite low rates of respondents’ self-identification with “conservative or right-wing” politics, we observed a prevalence of right-of-center crypto-political types. A broadly similar distribution was observed in a CoinDesk report published in 2018 (Ryan, 2018). The discrepancy between general political self-identification and our crypto-specific labeling bears further investigation. It may relate to an association of the term “conservative” with social conservatism, whereas crypto-libertarianism, the crypto-political type we found to be most common, emphasizes a form of economic libertarianism. Furthermore, the connotations of “conservative” and “liberal” vary significantly by geographic region, so the question may have been interpreted differently across respondents based on their country of residence.

The correlation of the constructed political axis with the first principal component–a commonly-used, well-validated axis–suggests a primacy of political variation in explaining patterns of responses. Furthermore, the existence of differences in the distribution of beliefs between self-identified political orientations indicates that traditional political ideologies have some bearing on how participants relate to blockchain technology. For example, the “left-of-center” group articulated distinct beliefs about economic opportunity, fairness of wealth distribution, privacy, and the growth of crypto (Q11–13, Q6, and Q9), suggesting that left-of-center respondents are more likely to apply more community-oriented multi-stakeholder values to the blockchain ecosystem. The “non-aligned” group, on the other hand, articulated distinct beliefs about gender equity and government regulation (Q15 and Q5), suggesting this group is more clearly defined by lower trust in existing government institutions2. This lower approval of government regulation suggests that those who identified as neither left-of-center nor right-of-center are more likely to position themselves as separate from existing political and governance systems entirely. It also aligns with variation we identified in attitudes about blockchain governance. Differences in opinion between maximizing on-chain governance and empowering off-chain stakeholders seem to map onto broader political attitudes about the role of government in citizens’ lives, with greater tolerance of state governments aligning with increased openness to a role for off-chain processes in blockchain governance.

We are interested in understanding the extent to which the characteristics of developers and users of specific blockchains are distinctive of each blockchain. Critics like David Golumbia have argued that Bitcoin, both in its design and ideological constitution, is principally a conservative movement interested strictly in Bitcoin’s record of gaining value (Golumbia, 2016). Those observations were not made in opposition to Ethereum or any other blockchain, although Ethereum had been live for a year at the time of Golumbia’s writing. Our findings indicate that in fact, there are few differences between Bitcoin and Ethereum users. However, differences in technical implementation between Bitcoin and Ethereum may relate to differences in opinion on their governance. Unlike Bitcoin, which has limited support for transactions other than money transfers, Ethereum as an infrastructure enables the developing and building of various applications and projects. The broader set of use cases for Ethereum may lead its users to believe a broader set of stakeholders should be involved in its governance. Furthermore, Ethereum affiliation was associated with a greater sensitivity to perceived socioeconomic inequity, which may relate to differences in how the blockchains are used alongside other technology. In Ethereum ecosystems, users linking their own blockchain activity to other personally-identifying information, such as Discord handles or Twitter accounts, is not uncommon; more research is needed to understand whether lower rates of anonymity relate to greater awareness of actual or perceived social demographics.

Communities organized around crypto are proving to be a laboratory for new ways that humans can organize collective action, but are not operating in a historical vacuum: It appears that some patterns observed in early users of other internet technologies have arisen or continue to appear in the blockchain context as well. To complement this sociological work, further anthropological research could shed some light on the extent to which the economic and political beliefs held by participants in crypto echo the ideologies of two earlier movements: the cryptographic hacker and open-source software communities. The distribution of responses relating to fair rewards for developer teams and the utility of hard work and in crypto indicates that meritocratic values are prevalent; meritocracy may play a similar role in blockchain ecosystems, themselves often open source, as it has in prior open source and hacker communities (Gabriella Coleman, 2013; Dunbar-Hester, 2019). Privacy has been at the forefront of concerns in the development of internet technologies since the cypherpunks (Hughes, 1993) and remains prevalent in blockchain (Brunton, 2020). Further research is needed to understand how these values compare to those of open-source software communities and early adopters of the internet or how they may have changed over time as cryptocurrencies become more mainstream.

6 Limitations

6.1 Survey methodology

Selection bias may arise given that the random sample assumption is limited by how the survey was distributed. In particular, since the survey was opt-in, people with stronger and potentially more extreme opinions may have been more motivated to complete the survey. Also, the survey was made available only in English, and so is likely not representative of the full geographic distribution of users of blockchain technologies. Presentation of some preliminary findings prior to finalizing data collection may also have influenced some respondents. Additionally, we do not have a guarantee of uniqueness of each respondent; moreover, the two recruitment strategies we used may have motivated respondents to provide multiple responses.

In choosing the wording of each question and answer choice, we made an effort to mitigate response bias. Still, we have identified some limitations in interpreting questions based on the wording of the questions. Q5 may have had an insufficient distinction between the two most commonly-selected choices. In answering Q14, respondents who selected “Keep on doing what we’re doing” may have rejected the premise of the question rather than believed this was a way to achieve the stated goal. Additionally, while we intended Q15 to refer to perceptions of gender inequity in participation or compensation within crypto, the wording of the choices may have been too vague.

Further demographic information would be valuable context for interpreting some questions. Future work could include a question on the geographic location of respondents, where local regulations and political attitudes would inform a more detailed analysis of questions on national government regulation and political affiliation. This affects several of our design choices, and interacts with our approach to political types. Interpretation of question 18 on political self-identification, and of the assigned political types, is similarly limited by differences in how terms such as “liberal” and “conservative” are understood across the world. For example, given our international audience, the location of a political “center” along a left-right axis can vary greatly by country, with those in the “center” in the United States, where the Pew Research Center typology was developed, being most similar in ideology to those who might be identified on the “right” or “left” in other parts of the world. Future work will be more careful in basing analysis of such a global phenomenon on instruments calibrated to a single country, shallowly by grouping respondents by country or region, or more substantively by explicitly modeling more fundamental country-level differences in received political spectra. Such deeper work may help us account for those counter-intuitive results that defy familiar American political alignments, such as our finding that left-of-center respondents are more likely than those right-of-center to believe that the crypto ecosystem is fair to participants (see Q10–Q12).

Going further, the political types that we introduced to motivate participation in the survey will require more formal development and elaboration in future work. We did not validate it with self-reports, and our attempts to support it through data-driven analysis (reported in the Supplement) only supported it in the broadest strokes. For this reason, we did not base any deeper contingency table or interaction analysis on our types, despite our access to a sample large enough to justify such analyses.

6.2 Analysis

To be able to use PCA for the discrete data, we one-hot encoded specific choices. While PCA is generally better suited to continuous data than Boolean data, we find that in this context the results were cleanly interpretable. We also chose not to include null responses as an additional coded choice for feature selection or factor analysis. While this does result in using only a subset of the responses and potentially removing relevant information about respondents’ beliefs, it prevents the null responses from receiving artificially high importance due to their relative rarity and bypasses the difficulty in interpreting the null response.

7 Conclusion

In this work, we have introduced a new survey of blockchain users’ political, economic, and governance opinions with respect to crypto. Based on 3,710 survey responses, we find that users were spread across a variety of perceptions of the distribution of economic power, normative beliefs about the distribution of power in governance, and opinions on the role of external regulation of crypto, though they were broadly in agreement that crypto has a net-positive impact on the world. Equal numbers of respondents self-identified as liberal or non-aligned, while only about a third as many respondents self-identified as conservative; this self-reported political affiliation was associated with differences in opinions on most questions, but especially on economic fairness, decision-making power, and how to obtain favorable regulation. In contrast, we observed few differences in opinions between respondents affiliated with Bitcoin and with Ethereum, except on issues of blockchain governance and regulation and on personal attitudes towards crypto. While the full field of beliefs elides neat interpretation in terms of underlying factors, we found that the existence of a political dimension was supported both by a theory-driven construct and by a common, well-validated analytical method (PCA).

While this dataset is an important step towards understanding the distribution of crypto users’ beliefs about blockchain technology and its utility, open questions remain as to why users believe what they do about crypto and how their beliefs match up with reality. For example, considering the question of who should have decision-making authority over a blockchain: Is the large-minority opinion that token-holding voters should control a blockchain underlied by a belief that minimizing human input to governance will make it more efficient and less flawed? Is there a disconnect between the common normative beliefs of what should be happening in cryptogovernance and which types of stakeholders actually can and do participate in governance of major blockchains? Obtaining an accurate understanding of the economic functions that blockchain fulfills for its users and the extent to which users are polarized on key issues of blockchain governance could help developers, lawmakers, and regulators of blockchain technology act more effectively.

Although our research found only a few instances where affiliation with a specific blockchain was associated with differences in beliefs, further research is needed to better understand whether specific architectures or ecosystems within crypto (including newer chains, Layer 2 protocols, or even large DAOs) differ in the values or goals embedded in them. Future interdisciplinary work could shed some light on the extent to which participants have common understandings of core signifiers such as decentralization and autonomy (Schneider, 2019), as well as the broader question of why differences between ecosystems may exist.

Our findings represent a temporal snapshot of ecosystems that are continuously evolving in response to fluctuating cryptocurrency markets and changing regulatory environments. Given that our work takes inspiration from the long-running Pew political survey, we see the need for a regular survey of cryptopolitical sentiment, with an added demographic panel. By identifying what stays constant and what changes over time across–and within–ecosystems, a recurring survey could facilitate the description and comparison of ideologies and modes of participation in crypto as it evolves.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7689912. We have created a global persistent link to a Zenodo archive that includes both the dataset and this code: https://zenodo.org/record/7742328#.ZBRHx-zML9E.

Author contributions

LK conducted data analysis and wrote the manuscript. SF advised on methodology and advised on the manuscript. JT designed and deployed the survey instrument and advised on the manuscript.

Funding

LK and JT were supported by grants from the Filecoin Foundation and from One Project.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Michael Zargham for technical discussion, Ann Brody for qualitative discussion, and Tyler Sullberg and Nathan Schneider for feedback on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbloc.2023.1125088/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^Throughout the text, we use the term “crypto” to encompass blockchain technologies such as cryptocurrencies and the communities and ideologies which drive their development and use.

2.^We refer in this work to respondents who chose to identify as neither left-of-center nor right-of-center as “non-aligned”. We choose this term in contrast to a term such as “apolitical” in a nod to ideas of political agnosticism developed by ethnographers in observing open-source communities (Gabriella Coleman, 2013).

References

1

AllenD. W. E. (2019). Entrepreneurial exit: Developing the cryptoeconomy.”,” in Blockchain economics: Implications of distributed ledgers: Markets, communications networks, and algorithmic reality (Rochester, NY: World Scientific), 197–214. Avaliable At: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3139122.

2

AlstonE.LawW.MurtazashviliI.WeissM. (2022). Blockchain networks as constitutional and competitive polycentric orders. J. Institutional Econ.18 (5), 707–723. 10.1017/s174413742100093x

3

BauerleN.RyanP. (2018). CoinDesk releases Q2 2018 state of blockchain report CoinDesk. Avaliable At: https://www.coindesk.com/business/2018/07/25/coindesk-releases-q2-2018-state-of-blockchain-report/.

4

BeltraminiE. (2021). The cryptoanarchist character of Bitcoin’s digital governance. Anarch. Stud.29 (2), 75–99.

5

BrodyA.CoutureS. (2021). Ideologies and imaginaries in blockchain communities: The case of Ethereum. Can. J. Commun.46 (3), 19. 10.22230/cjc.2021v46n3a3701

6

BruntonF. (2020). Digital cash: The unknown history of the anarchists, utopians, and technologists who created cryptocurrency. Princeton, New Jersey, United States: Princeton University Press.

7

BuchholzK. (2021). These are the countries where cryptocurrency use is most common world economic forum. Avaliable At: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/02/how-common-is-cryptocurrency/.

8

ChohanU. W. (2017). Cryptoanarchism and cryptocurrencies. Avaliable At: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3079241.

9

Dunbar-HesterC. (2019). Hacking diversity. Princeton University Press. Avaliable At: https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691182070/hacking-diversity.

10

FilippiD.LoveluckB. (2016). The invisible politics of Bitcoin: Governance crisis of a decentralized infrastructure. Internet Policy Rev.5 (4), 427. 10.14763/2016.3.427

11

FilippiD.SantoliniP. (2022). Extitutional theory: Modeling structured social dynamics beyond institutions SSRN scholarly paper. Avaliable At: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4001721.

12

ColemanE. G. (2013). Coding freedom: The ethics and aesthetics of hacking. Princeton University Press.

13

Global State of Crypto (2022). Gemini. Gemini. Avaliable At: https://www.gemini.com/state-of-us-crypto.

14

GolumbiaD. (2016). The politics of Bitcoin: Software as right-wing extremism. U of Minnesota Press.

15

HofmanD.DuPontQ.WalchA.BeschastnikhI. (2021). ““Blockchain governance: De facto (x)or designed?”,” in Building decentralized trust: Multidisciplinary perspectives on the design of blockchains and distributed ledgers (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 21–33. 10.1007/978-3-030-54414-0_2

16

HonkanenP.NylundM.WesterlundM. (2021). Organizational building blocks for blockchain governance: A survey of 241 blockchain white papers. Front. Blockchain4, 613115. 10.3389/fbloc.2021.613115

17

HughesE. (1993). A cypherpunk’s manifesto. Avaliable At: https://www.activism.net/cypherpunk/manifesto.html.

18

HusainS. O.FranklinA.RoepD. (2020). The political imaginaries of blockchain projects: Discerning the expressions of an emerging ecosystem. Sustain. Sci.15 (2), 379–394. 10.1007/s11625-020-00786-x

19

KavanaghD.EnnisP. J. (2020). Cryptocurrencies and the emergence of blockocracy. Inf. Soc.36 (5), 290–300. 10.1080/01972243.2020.1795958

20

LiuY.LuQ.ZhuL.PaikH. Y.StaplesM. (2021). A systematic literature review on blockchain governance. J. Syst. Softw.197, 111576. 10.1016/j.jss.2022.111576

21

MayT. C. (1994). The cyphernomicon: Cypherpunks FAQ and more. Avaliable At: https://nakamotoinstitute.org/static/docs/cyphernomicon.txt.

22

NadeemR. (2021). Beyond red vs. Blue: The political typology Pew research center. Avaliable At: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/11/09/beyond-red-vs-blue-the-political-typology-2/.

23

NakamotoS. (2008). “Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Avaliable At: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf.

24

PerrinA. (2021). 16% of Americans say they have ever invested in, traded or used cryptocurrency Pew research center. Avaliable At: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/11/11/16-of-americans-say-they-have-ever-invested-in-traded-or-used-cryptocurrency/.

25

ReijersW.O’BrolcháinF.HaynesP. (2016). Governance in blockchain technologies & social contract theories. Ledger1, 134–151. 10.5195/ledger.2016.62

26

ReijersW.WuismanI.MannanM.De FilippiP.WrayC.Rae-LooiV.et al (2021). Now the code runs itself: On-chain and off-chain governance of blockchain technologies. Topoi40 (4), 821–831. 10.1007/s11245-018-9626-5

27

RyanP. (2018). “Left, right and center: Crypto isn’t just for libertarians anymore CoinDesk. Avaliable At: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2018/07/27/left-right-and-center-crypto-isnt-just-for-libertarians-anymore/.

28

SchneiderN. (2019). Decentralization: An incomplete ambition. J. Cult. Econ.12 (4), 265–285. 10.1080/17530350.2019.1589553

29

SzaboN. (1996). Smart contracts: Building blocks for digital markets. EXTROPY J. Transhumanist Thought18, 2.

30

van PeltR.JansenS.BaarsD.OverbeekS. (2021). Defining blockchain governance: A framework for analysis and comparison. Inf. Syst. Manag.38 (1), 21–41. 10.1080/10580530.2020.1720046

31

WinnerL. (1980). Do artifacts have politics?” Daedalus, winter 1980. MIT Press.

32

ZamfirV. (2019). “Against szabo’s law, for A new crypto legal system crypto law review (blog). Avaliable At: https://medium.com/cryptolawreview/against-szabos-law-for-a-new-crypto-legal-system-d00d0f3d3827.

33

ZwitterA.HazenbergJ. (2020). Decentralized network governance: Blockchain technology and the future of regulation. Front. Blockchain3, 12. 10.3389/fbloc.2020.00012

Summary

Keywords

cryptopolitics, cryptoeconomics, blockchain governance, cryptocurrency users, survey research

Citation

Korpas LM, Frey S and Tan J (2023) Political, economic, and governance attitudes of blockchain users. Front. Blockchain 6:1125088. doi: 10.3389/fbloc.2023.1125088

Received

15 December 2022

Accepted

14 March 2023

Published

24 March 2023

Volume

6 - 2023

Edited by

Quinn Dupont, York University, Canada

Reviewed by

Carsten Sorensen, London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom

Darcy W. E. Allen, RMIT University, Australia

Peter Chow-White, Simon Fraser University, Canada

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Korpas, Frey and Tan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joshua Tan, joshua.z.tan@gmail.com

This article was submitted to Blockchain Economics, a section of the journal Frontiers in Blockchain

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.