- 1Department of Architecture, Islamic Azad University of Shahrekord, Shahr-e Kord, Iran

- 2Department of Architecture, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

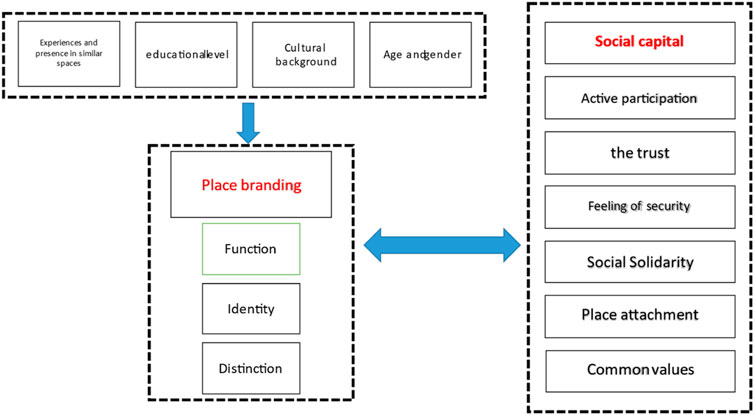

The aim of this study is to investigate the impact of neighborhood branding in increasing its social capital. The issue of social capital at the neighborhood scale is one of the most important components of quality and for achieving various aspects of sustainability in human life in urban societies. Examining the background of this issue shows that paying attention to the potential of place branding as an essential and effective component in increasing the social capital in neighborhoods has not been seriously studied. This study aims to know the components and measures of place branding that can significantly impact increasing social capital. The conceptual model of this research has been tested in 13 neighborhoods of Ahvaz city and using the opinions of 663 residents of these neighborhoods. The research results show that social capital in neighborhoods is directly related to the brand of those neighborhoods. This study is limited to metropolises with diversity of architecture and diversity of texture and social structure in Iran. The results show that place branding with a coefficient of 0.77 has the highest impact on social values. The impact of place branding on social solidarity, social security, social participation, and place-belonging is equal to 0.61, 0.55, 0.39, and 0.33, respectively.

Introduction

The increasing growth of urbanization and changes in the nature and complexity of issues have caused inefficiency of planning and management on a macro scale. This has made the necessity of paying attention to the lower levels and having a “bottom–up” view more evident to solve urban problems sustainably because in the smallest urban unit, i.e., the neighborhood, the dimensions of life are the most comprehensive and comprehensive attention seems inevitable. In this regard, paying attention to local funds is especially required in urban planning and design. Therefore, understanding the mechanism and role of social capital to realize the goal of reducing tasks and delegating responsibilities to institutions provides the basis for expansion of social capital in order to increase social and cultural interactions and connections at the local level in order to get help from citizens in achieving sustainable development. It is one of the main goals of the present research study.

Urban neighborhoods are one of the micro and tangible centers for forming cultural identities and social affiliations. Local values and norms, often in the form of confrontational relationships, strengthen the sense of social belonging, according to which, in the structure of urban neighborhoods, the role of social capital as a set of norms, informal values, customary rules, and moral obligations, where interaction is formed in them and facilitates social relations (Furlan, 2015; Granie, et al.,2014; Huang, 2006). Therefore, human development is considered one of the main pillars of sustainable social development (Yeganeh, 2020). Social capital also undergoes numerous changes in urban neighborhoods due to physical, economic, technological, and social changes. Branding is a powerful tool that can produce and reproduce social capital in neighborhoods. The purpose of this study is to examine the various components of location branding at the neighborhood scale on the manner and amount of production and reproduction of social capital (Kavaratzis and Ashworth, 2005; Decline, 2010; Dinnie, 2011).

The urban brand is an essential asset for sustainable urban development and the difference between places. Urban branding is a phenomenon wherein cities need to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage in globalization and pave the way for promotion of social capital at the neighborhood level (Bahari et al., 2331: 112). In recent decades, extensive studies have been conducted on the role of cities as a driver of innovation and economic and social growth, and there is a tendency to pursue branding, re-branding, renovation, and urban renewal strategies (Altman and Setha 1992; Anguelovski and Martínez, 2014). These activities are considered an integral part of urban management and development. They are considered not only in the physical equipment of urban infrastructure but also in the development of psychological processes and creation of a distinct image and identity of the city and neighborhood (Lee, 2013; Rainisto, 2013). By emphasizing the core values, this concept introduces the place, neighborhood, and city as a lasting product in the national and international arena by introducing images and spatial attractions into a prominent and tangible identity (Sanchez, 2004; Sriram, Mersha, Herron, 2007).

Urban experts in defining the urban brand believe that the concept of the urban brand, on the other hand, is a combination of local symbols and values, historical identity, urban culture, social and ethnic characteristics, monuments and monuments, national and international relations, attractions and facilities (Kemmis, 1995; Kearney, 2006; Landry, 2006), and regional and even brand persons (Steven, 2005). Combining these blends presents a picture of the city that competes with other cities in terms of inland and overseas requirements and ultimately maximizes interactions, social capital, and citizenship interests. The process of creating a city image in branding requires the participation of many individuals and groups; obtaining different opinions is a practical approach to creating a city image (Alexander 1979; Abbaszadeh et al., 2012).

The neighborhood unit with a limited scale and location is a significant source of social capital. Since place belonging in the scale of neighborhood and neighborhood unit is always one of the essential place scales, branding of the neighborhood unit will increase the level of place attachment and increase social capital. Various studies and reviews have been carried out on other scales. However, the importance of the neighborhood scale is of great necessity for using the inner potentials of the neighborhoods to increase place attachment and social capital.

In previous research studies, the focus of studies in the social capital field is based on cultural aspects and architectural morphology, and the symbolic and identity concept of neighborhoods has been investigated to a great extent. However, the expansion of new concepts, including branding at the neighborhood scale and recognition of important and influential indicators, is new and innovative. This research aims to identify how place branding affects different dimensions and components of the social capital in localities with different types and characteristics (Figure 1).

Literature

Social capital

The concept of social capital has been further explored in research derived from the studies of Jane Jacobs, Robert Pantam, James Coleman, and Hudson as the first research efforts. Social capital includes social connections, attitudes, norms, and institutions that contribute to societal wellbeing, for instance, through giving us a sense of belonging. Social capital is defined as the values and properties, such as social interaction, mutual trust and understanding, and shared vision and norms, which allow organizational members to work toward a goal successfully (Ayse. et al., 2022). It is recognized as a multidimensional construct consisting of structural, relational, and cognitive capital (Fraser and Naquin. 2022). The local community is the most suitable bed for achieving social richness so that social patterns can measure the textures of urban neighborhoods. In the process of moving from the traditional concept of urban planning, traditional concepts are derived, which are inherently derived from sciences such as sociology, and the explanation of problems related to identity characteristics and attachment to neighborhoods goes through the refinement of concepts such as social capital. The definition of social capital in this study is simply a set of processes that result from social actions and can be used to meet individual personal and general needs and improve their quality of life (Pongponrat et al., 2018; Yeganeh and Kamalizadeh, 2018).

On the other hand, by changing the pattern of life in neighborhoods, local social communication and face-to-face and direct exchanges that have led to formation of the local social capital have been reduced, and social trust and civic participation, as the two main components of social capital, have diminished (Fraser et al., 2021; Fraser and Naquin, 2022). According to various studies conducted in the neighborhood, most people barely know their neighbors and have the least amount of social contact with their neighbors. Urban neighborhoods, as an intermediary between the city and citizens and as the central nuclei of social currents over time, have played a crucial role in shaping and organizing urban affairs. Providing daily services has induced a sense of belonging, identity, and richness of social relations (Monteil et al., 2020; Zare et al., 2022).

Social capital is used as a theoretical basis for examining the social status of the neighborhood. Moreover, based on that, the existing capacities in the neighborhood can be identified and considered more carefully. Local social capital can be described in terms of the following aspects:

A. Neighborhood social capital as a multilevel structure: social capital in this section can be defined as multilevel interconnections between network-based resources to be used effectively. Mutual trust in the form of networks formed within the neighborhood for neighborhood management and planning. It can lead to creating a multilevel social structure of citizens in the neighborhood and ultimately make it easier to manage neighborhood affairs.

Therefore, social capital in the neighborhood tries to gain citizens’ trust by creating a multilevel structure and developing participatory management and planning in the neighborhood. This aspect of social capital is a structural social capital, and organizations, institutions, and networks have a decisive role in its formation.

B. Neighborhood social capital as a platform for the use of local capacities: social capital creates different forms in the use of local capacities due to different dimensions and aspects and different forces. Recent research on social capital also emphasizes certain forms of social capital. It can apply social and political values and norms to all communities, just as cultural and socio-economic backgrounds shape individuals’ perceptions of social capital, so these backgrounds identify and present social capital needs. It presents the characteristics of neighborhoods with a high degree of social capital in the form of four things: people will feel that they are part of the neighborhood; they feel useful and valuable, and their ability to participate in the neighborhood is strengthened; they know themselves and feel safe in it; many networks of interactions between people are formed.

C) Social capital as a tool to strengthen appropriate neighborhood policies: planning policies can be defined at the national and significant levels and implemented at the local level with a participatory planning approach by neighborhood residents. People should be used in their implementation. The basic domains of social capital based on the said concepts and approaches can be in the form of empowerment, participation, participatory activities, and public goals and objectives to support networks; pay attention to the values and norms of society and trust as an element; strengthen and protect appropriate neighborhood policies in social capital and belonging and environmental safety; and renovation and improvement of worn-out urban tissues. The strength of these indicators among the residents of worn-out tissues can function as a facilitator and create a better ground for the success of renovation programs. However, its weakness can be considered a deterrent and negative consequence in implementing such projects.

D) Social capital as a planning tool: one neighborhood planning characteristic is based on attention to social and human capital. The formation and accumulation of these capitals require a neighborhood-oriented structure in management and planning. In centralist structures based on a traditional perspective, general and inflexible divisions of social capital, i.e., networks of cooperation and mutual trust are not formed (He et al., 2021). Neighborhood planning emphasizes that neighborhood residents, through the shared and long experience of living in an environment, can identify many of the needs and necessities of their daily lives and, in coordination with senior management, help create sustainable urban neighborhoods (Sakhaei, Yeganeh, Afhami, 2022). It has more time and space on a local scale. In terms of planning, decentralization, and transfer of affairs to local and micro levels and moving toward a self-governing system, local planning and management are other significant characteristics that can be desirably implemented in cities by relying on social capital (Hikichi et al., 2020; Yeganeh, 2020).

Place branding

Urban branding is a way to increase urban attraction and an essential factor of urban cognition and identity (Rainisto, 2013; Zarei and Yeganeh, 2018). An urban brand is a complex combination of the audience’s inferences and mental images of a city and its citizens, living space, business space, and tourist attractions. In other words, “urban branding” is a comprehensive and long-term strategy along with the city’s urban development strategy and economic development strategy, consisting of a series of integrated strategies, processes, and activities (Anton and Lawrence, 2016).

Finally, it promotes the city’s reputation among other cities, increases its competitive capabilities, and improves the lives of citizens. Urban branding refers to activities that aim to turn a place into a destination (Ryan, 2005; Shafter et al., 2000; Yeganeh, 2020). Contrary to popular belief that destination brand building is known only in communication, destination branding is the identification, organization, and coordination between all available variables that affect the image of the destination brand (Sosik et al., 2012; Taylor, 2000; Tuan, 1977; Zare et al., 2022).

Place branding is sometimes used interchangeably with place marketing, which competes to attract tourists, visitors, investors, citizens, and other cities’ internal resources (Avraham and Ketter, 2008). In other words, the urban brand provides the image of the place, which emphasizes the unique features of the city so that the city can compete with other competitors. The process of urban branding is also a sequential process (Dinnie, 2011). Urban branding can be one of the most important factors for its success (Chin, 1998; Lee and Kim,1999). In accordance with their characteristics and capabilities on the one hand and the needs and requirements of the future world on the other hand, to brand consciously and systematically, conscious branding will give new identity to cities in the future (Avraham and Ketter, 2008; Braun and Zenker, 2010; Yeganeh and Kamalizadeh, 2018).

In the lifestyle of local residents (lee, 2013), branding is based on representations and perception of images. As a result of this thinking, they concluded that the landmark place is considered an imaginary city consisting of a set of images and representations under the brand name (Appleyard, 1979; CABE, 2003). Urban and neighborhood branding is an effective tool for development of cities, and on a smaller scale, neighborhoods. In fact, it increases the distinction and success of living places and the value of social capital and social, cultural, political and, consequently, absorption and development. Investment, tourism boom, technology transfer, etc., are affected. Branding, above all, is in place along with increasing and reproducing social capital (Manzo, 2005; Manzo, 2006; Lefebvre, 2009; Lewicka, 2011). The formation of entrepreneurship and urban social capital can be considered the most important fields of place marketing and urban branding (Newman, 1972; Marcus, 1974; Portes, 1998; Perkins et al., 2002; Yeganeh, 2015). Today, globalization and development of urban systems and local governments has accelerated the process of production of social capital in neighborhoods and urban branding.

The theoretical literature on social capital and place branding

Social capital is considered a community asset that can be considered in various ways in planning. Social capital refers to specific processes among people’s organizations, which are jointly formed in an atmosphere of trust and lead to mutual social benefits (Proshansky et al., 1983; Ramyar, 2011). Social capital is defined as the quality of social relationships such as trust, shared norms, and values that emerge from the heart of social groups and increase social organizations, participation, and collective action for common goals (Rapoport, 1982; Ratcliffe and Korpela, 2016). Social capital emphasizes that there is little experience with social capital on a micro scale, while its impact will be more pronounced on these scales. Scientists emphasize the role of social capital in low-income and poor societies. However, there is less knowledge about how it works in societies known at the national and national levels, often more so than on the micro and neighborhood scales. The main part of this shortcoming in micro and neighborhood scales is the ambiguity of this concept and lack of a clear definition of it in this scale (Riger, and Lavrakas,1981; Rivlin, 1982).

Materials and methods

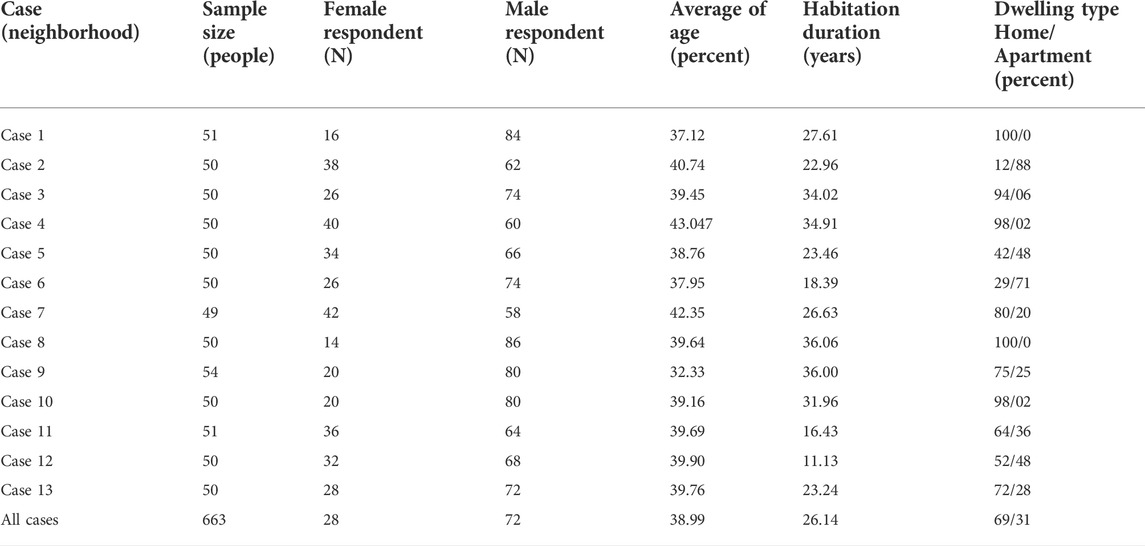

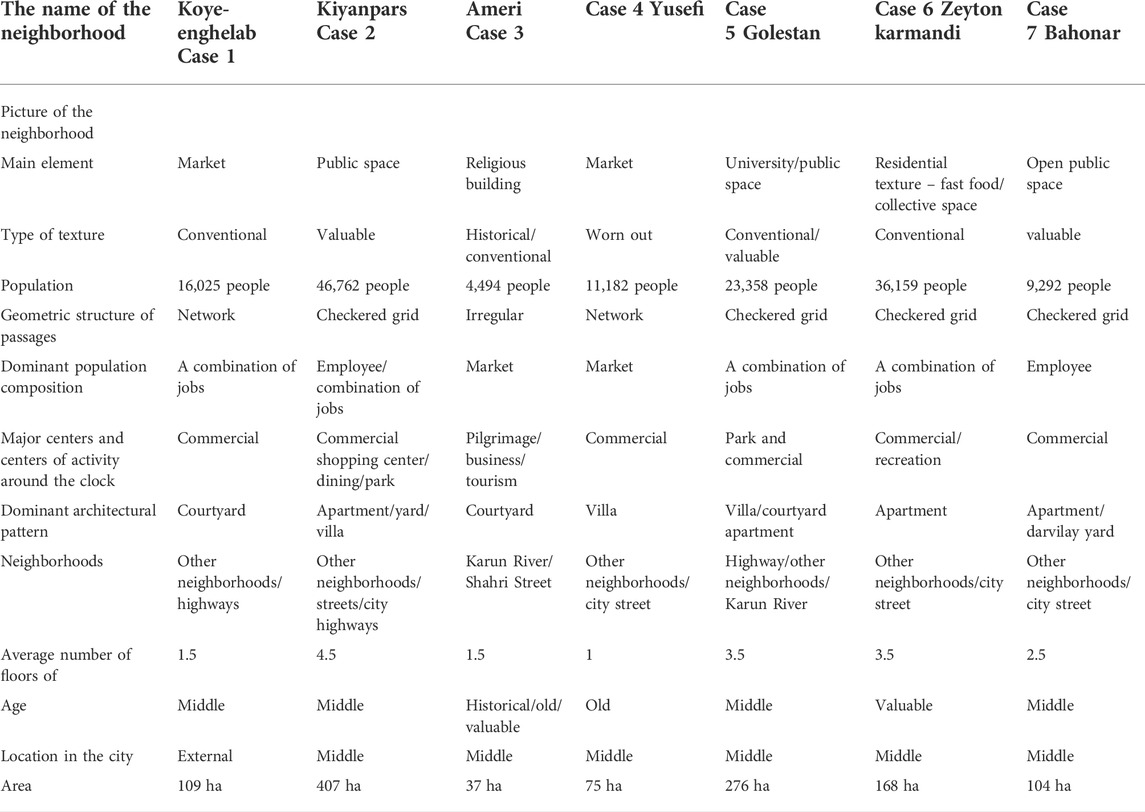

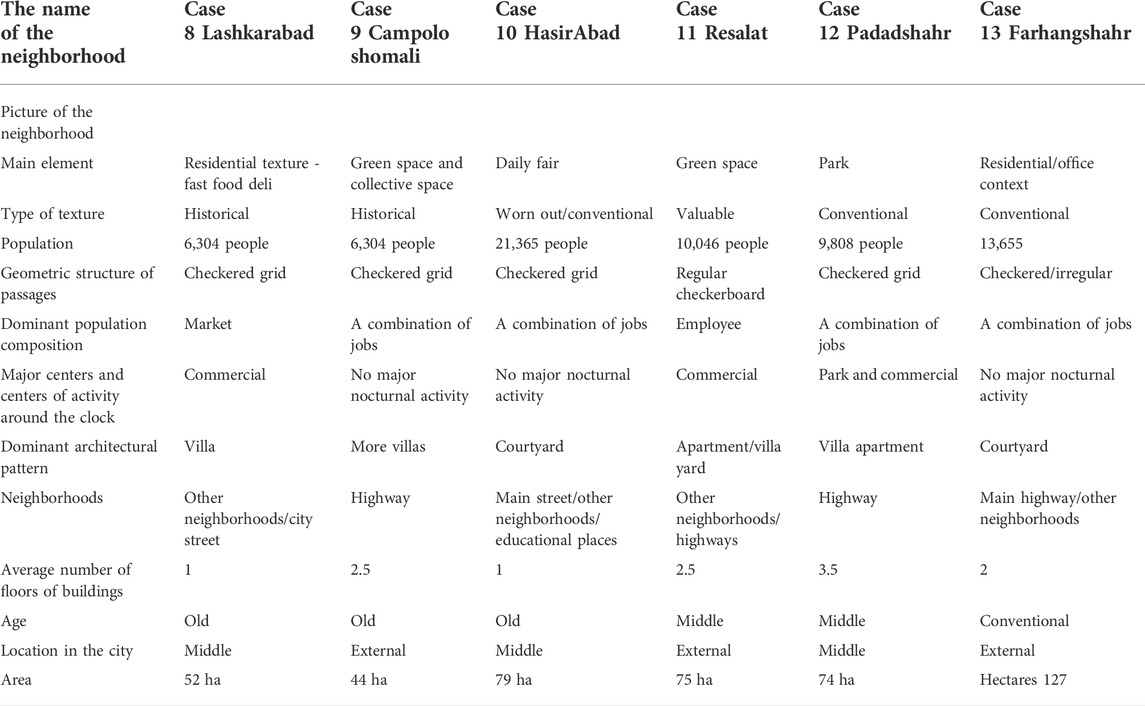

The research method is a survey with questionnaire tools (Jacobs, 1961; Fornel and Lacker., 1981; Kang, 2006). Also, field and documentary studies have been conducted. A conceptual model has been proposed based on the theoretical foundations and frameworks related to place branding and quality of the architectural body. A closed questionnaire has been designed based on the indicators, concepts, and variables used in the conceptual model. The case study conducted in this study is of thirteen neighborhoods of Ahvaz in Iran selected by considering the parameters affecting the typology of neighborhoods such as neighborhood structure, type of neighborhood center, neighborhood economic level, hierarchy of passage network, architectural style and pattern, location in the urban context, and clusters and classifications of neighborhoods presented. Based on these clusters, several neighborhoods were randomly selected in proportion to the number of samples in each cluster. The number of people interviewed in the neighborhood is proportional to the selected population. The general characteristics of the respondents in the interview and survey are given in the table below (Table 1). The statistical population includes citizens and residents in the study neighborhoods and experts in this field, which experts use to validate indicators and measure the proposed indicators of the statistical population of citizens and residents used. The statistical population of the study consists of the neighborhoods of Ahvaz. The number of samples is 663 for citizens, 20 for experts, and 6 for six neighborhoods.

The selection of neighborhoods is targeted and clustered. Neighborhoods are classified based on demographic, physical, and age characteristics and placement in the middle or central core or around the city. The number of clusters is 6. Based on the frequency of each neighborhood, 13 samples have been selected. Individual sample size is 663. There were limitations regarding the number of samples for the neighborhood analysis unit and the interviewed people. Regarding people, cultural restrictions made interviewing women and the elderly less viable, and the COVID-19 situation made people less willing to give interviews. In the sample of neighborhoods, due to the presence of common characteristics in some neighborhoods, the diversity in the number of clusters for the neighborhoods was not complete.

The questionnaire was completed so that people over 18 in each household were part of the statistical population. Based on population and gender, one person from each household was randomly selected and questioned. The questions are closed and are on the Likert scale.

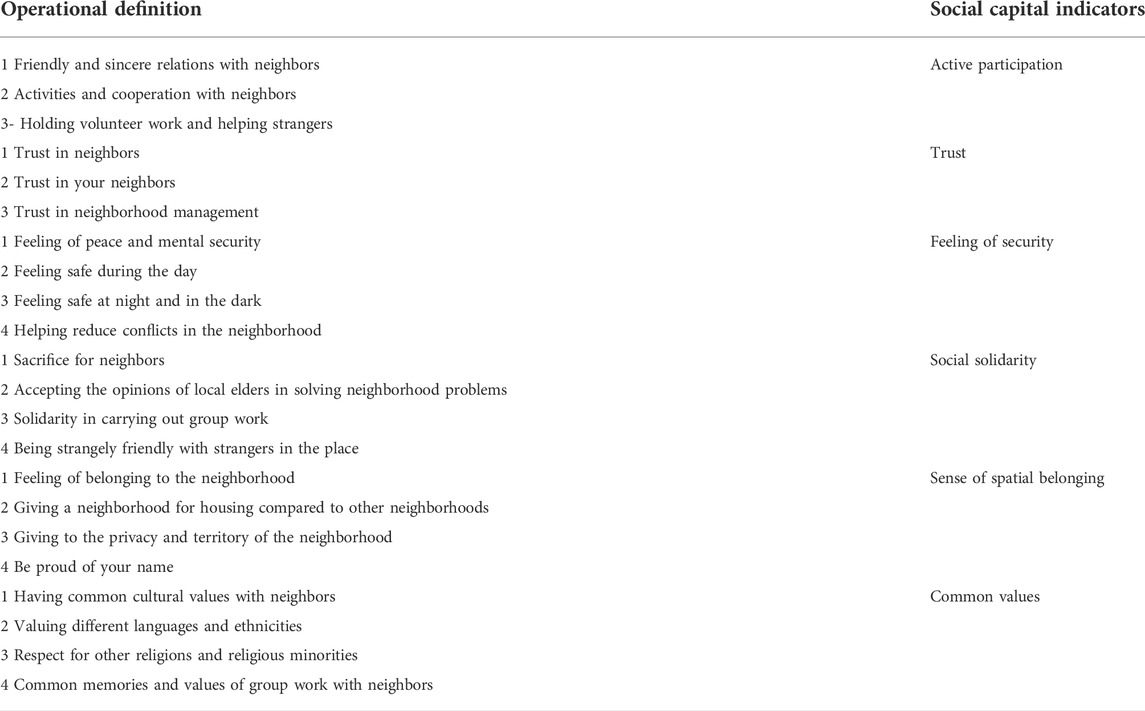

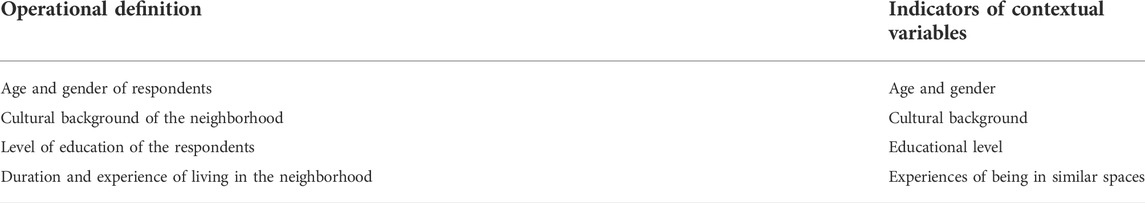

The parameters asked in the questionnaire include the following (Tables 1–3):

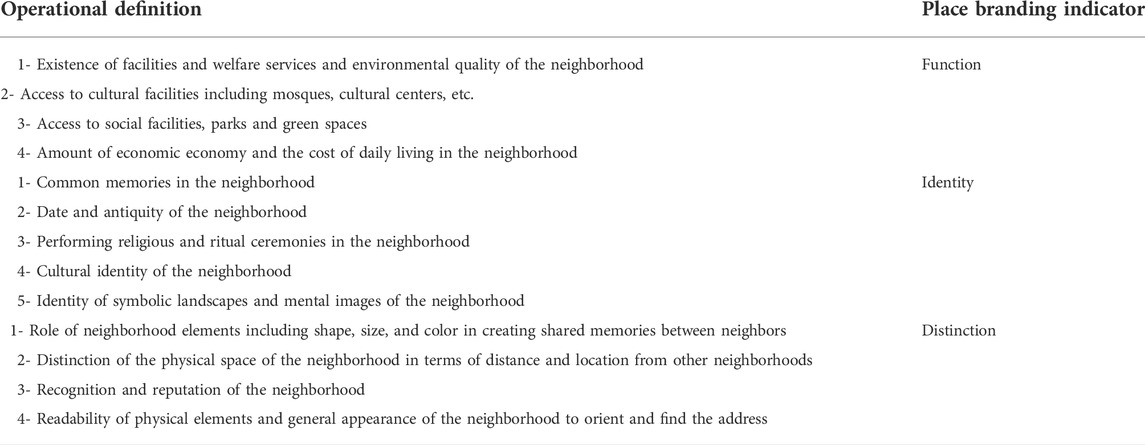

TABLE 2. Operational definition of indicators related to the location branding variable (Source: Authors)

Data analysis includes 1– correlation and regression analysis of data; 2– description of data includes grouping based on the general characteristics of the respondents, anatomy of the main variables, and description of the general characteristics of the respondents (Table 4).

Introduction of case examples

Ahvaz is one of the metropolises of Iran, located in the central part of Ahvaz city. The population of this city is approximately 1,200,000, and it is the seventh most populous city in Iran. Ahvaz has many bridges; for this reason, it is known as the city of bridges. Ahvaz, with an area of 18,650 ha, is considered the fourth largest city in Iran. Karun River, the most water-rich river in Iran, originates from Zardkooh and enters Ahvaz, dividing the city into eastern and western parts. The Ahvaz oil field, the largest oil field in Iran and the third largest in the world, is located within the city.

Introducing the studied neighborhoods in Ahvaz

1 – North Camploo and 2 – South Camploo (Revolution Alley): the Camploo neighborhood is located in the southwestern part of Ahvaz. This neighborhood is from the north with Andimeshk–Ahvaz road street; from the east with Quds boulevard, Quds square, Lashkar street, 15 Khordad square, Enghelab street, and Abu Muslim street, which is also known as Kemplo north; and from the south with 68 m street. Noor Street and Alhadi Street are limited to the south, and Hashemi Boulevard and 22 Bahman Boulevard from the west. 3 – Kianpars neighborhood: Kianpars neighborhood is located in the central part of Ahvaz city, and the essential places of Kianpars can be named as Sesame restaurant cafe, Fast food restaurant, Cactus restaurant, and Bermuda pizza. 4 – Ameri neighborhood: Ameri neighborhood in the southeast of Ahvaz city is located adjacent to the neighborhoods of Zaytoun Kargari, Asiabad, Bagh-e Sheikh, Khorramkushk, Karun houses, Symmetry Street, and a 24-m street. One of the important places of this place is the holy shrine of Ali Ibn Mahziar of Ahvaz. 5 – Yousefi neighborhood: Yousefi neighborhood is located in the southeastern part of Ahvaz city. This neighborhood is limited to Farzipour Street and Javadalameh Boulevard from the south and is adjacent to Padadshahr, Zibashahr, Fatemieh alleys, and Karun houses. Essential places in this neighborhood include a pure olive restaurant, daily market, and protein sales. 6 – Golestan neighborhood: Golestan neighborhood is located in the southern part of Ahvaz. Essential places in this neighborhood include Tiara Restaurant, Ghori Park, Bustan Park, Saadi Park, Haj Rahim Restaurant, Chika Cafe Restaurant, Persepolis Restaurant, Tariana Restaurant, Tiam Restaurant, Fast Food Restaurant, and Golestan Peach Park. 7. Zaytoun Neighborhood Karmandi: Zaytoun Karmandi neighborhood is located in the eastern part of Ahvaz city, and the important places of this neighborhood are Olive Park, Mahziar City Center, Olive Shopping Center, Koohrang Restaurant, and Olive Center Park. 8 – Bahonar Alley: One of the essential places in this neighborhood includes Vahdat Game City Park, Laden Park, Laleh Park, Atlas Park, Paprok Restaurant, Mahalla Park, and Mohammad Rasoolullah Library of Maskan and Sepah Banks. 9 – Lashkarabad neighborhood: It is located in the south of Ahvaz city, and among the important places of this neighborhood, we can mention Lashkarabad park, restaurant cafe, Atlantis restaurant cafe, flame falafel, Tanakura clothing, and shoe stores. 10. Hasirabad: It is located in the southeastern part of Ahvaz city. This neighborhood is bounded by Karun Street from the north, Shahrdari Street 20 m from the south, a 16-m side-street and Bavi Street from the south, and Nawab Safavi Boulevard and Velayat Square from the west. It is adjacent to the municipality. 11 – Resalat neighborhood: Resalat neighborhood is located in the southeastern part of Ahvaz. Essential places in this neighborhood include Maryam Park, Resalat neighborhood, Steel Industries neighborhood park, Bozhneh sanitary ware factory restaurant, and a set of wedding halls. 12. Padadshahr neighborhood: it is located in the southeastern part of Ahvaz city. The places of this neighborhood include Sorena Restaurant and Fast Food, Helion Restaurant, Sangak Bakery, Bridge Car Replacement Centers, Javad Al-A’meh Grand Mosque, and Hirad City Center Shopping Center. 13. Farhangshahr Neighborhood: located southwest of Ahvaz. The important places in this neighborhood include Malek Ashtar Park, Farhangshahr Neighborhood Park, Farhangshahr Neighborhood Park, Farhangshahr Neighborhood Park, Pamchal Restaurant, Astara Restaurant Cafe, Islamic Azad University of Ahvaz Branch, Payame Noor University, and Jihad Daneshgahi.

In this study, 13 neighborhoods of Ahvaz in southern Iran have been studied (Tables 5, 6)

Findings and discussion

Analysis of the effect of contextual variables on the components of social capital

The levels of education, age, and place of residence have been studied as the three main underlying variables in this study. It significantly affects the social capital parameters with a somewhat significant coefficient. Age has little effect on the components of social capital. However, this effect is minimal and positive. The history of living in a place significantly impacts trust and social participation, solidarity, common values, and a sense of spatial belonging. Living in a place has a more negligible effect on increasing the amount of social capital. However, the most significant impact of living history is related to common values of social solidarity and trust. The effect of the place of residence on the components of social capital is between one-tenth and nineteen percent. The level of education hurts some components of social capital and positively affects some others, although this effect is minimal. Removing the common values of social participation and trust has a negative effect. The impact factor is, on average, negative three hundred percent. Also, the effect of education on spatial belonging is a positive and tiny sense of security and in the positive range is three hundred percent. Belonging and common values show that all components are positively correlated. At the level of significance, i.e., zero, all results have the necessary validity. On average, the sense of spatial belonging is somewhat equally correlated with other components. However, the data show that the sense of belonging has the slightest degree of correlation with social participation.

Correlation of social capital components

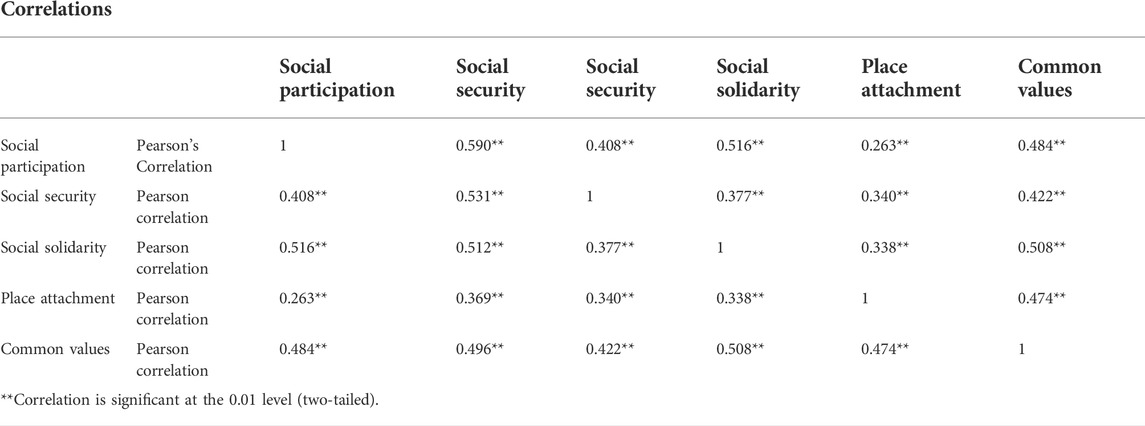

Examining the correlation table between the components of social capital, i.e., social participation, social trust, social security, social correlation, sense of spatial belonging, and common values shows that all components are positively correlated (Table 7). At the level of significance, i.e., zero, all results have the necessary validity. On average, the sense of spatial belonging is somewhat equally correlated with other components. However, the data in the table show that the sense of belonging has the slightest degree of correlation with social participation.

The correlation table between measures related to social capital shows that social participation and social security have a correlation of 0.59, which is the highest positive correlation. Also, the correlation coefficient between all components is positive. The correlation coefficient of social participation with social solidarity is also equal to 0.516. The correlation between social solidarity and common values is equal to 0.508. The rest of the correlations are lower than the median in the fuzzy scale.

Regression analysis of identity function and differentiation on social capital

Relevant regression tables show that the width of the origin for the linear graph between the parameters related to branding, i.e., the function of differentiation and identity with social capital is high. The maximum width of the origin or consistency is related to the function. Alternatively, beta related to function is much lower than that of differentiation and identity. This issue shows that social capital, as a dependent variable, has the most significant impact in the first place of identity and the next stage of differentiation (Table 8).

The effectiveness of function is much less compared to that of the other two items. The details of the regression data show three factors.

The regression data table (Table 9) shows the most causal relationship between identity and social capital. Next, distinction shows the most causal relationship with social capital. Also, relationship performance has a low level of meaning with social capital. It should be noted that in all samples, the significance level is zero (Sig=0.00), which is entirely significant. The formulas related to the relationship between performance, identity, and personality with social capital are as follows:

Social Capital = 3.1 + 0.17* Function

Social Capital = 2.12 + 0.17* Identity

Social Capital = 2.11 + 0.17* Distinction

In the aforementioned linear graphs, the width is positive from the origin, and the highest value is related to the linear regression relationship between the performance and social capital.

Y=Constant + B* X

Based on the linear regression formula, the cause-and-effect relationship between social capital and place branding is according to the following formula. Therefore, place branding has a factor of 0.5 on social capital. It can be said that this linear relationship is quite significant, considering the significance level (Sig=0.00).

Social Capital = 1.8 + 0.5* Place Branding.

Branding regression on social capital components

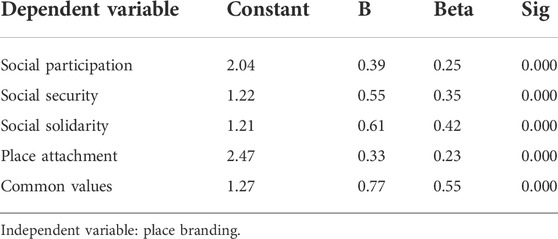

The branding regression table (Table 10) on the components of social capital, i.e., social participation, social trust, social security, social correlation, sense of spatial belonging, and shared values shows that place branding has the most significant impact on increasing the sense of spatial affiliation. Social trust has common values of social participation and social cohesion. It should be noted that the degree of impact on the following components is reduced as follows.

Y=Constant + B* X

Social participation = 2.04 + 0.39* Place Branding.

Social security = 1.22 + 0.55* Place Branding.

Social solidarity = 1.21 + 0.61* Place Branding.

Social attachment = 2.47 + 0.33* Place Branding

Social values = 1.27 + 0.77* Place Branding

The aforementioned linear relationships show that place branding has the most significant impact on social values and social solidarity. The amount of this effect is higher than the average. Place branding is also slightly more effective than the average on social security. Considering the significance level (Sig = 0.00), it can be said that this linear relationship is quite significant. The highest slope of the width from the origin for the linear graphs is related to the linear relationship between place branding and social attachment, that means that without place branding, the level of social attachment is acceptable.

Conclusion

Place branding is a recent approach to urban development. This approach is considered a powerful tool for urban development. Investigating and analyzing the branding of places in neighborhoods was studied through physical elements. The role of the three dimensions of branding, namely, the functions of identity and differentiation as its main criteria was studied separately. Identity and differentiation are the most powerful dimensions of branding places. Particular neighborhoods can cover their weaknesses related to identity and physical differentiation on an unusual activity such as a particular type of food or fast food or a very distinctive and unique activity in a place. The place branding index increases significantly in neighborhoods with identity and physical differentiation.

Also, neighborhood social capital shows a direct relationship with the brand of those neighborhoods. They have a readable neighborhood center, architectural style, specific symbols, and signs of familiar and natural infrastructure green and blue indexes, including communication bridges, indexes of antiquity and originality, neighborhood system, hierarchy in pedestrian and pedestrian access, and legibility of space, which are essential components in becoming a brand. It is not a place, but its branding can increase the amount of social capital. Identity branding and physical differentiation have the most significant impact on increasing social capital. The functional aspect of place branding also can promote social capital in neighborhoods. This issue is most effective when neighborhoods do not have many identities and physical differentiations by focusing on a specific function by attracting people from other neighborhoods and cities. They find a society that, in turn, leads to promotion of social capital.

The most causal relationship is between identity and social capital. Next, distinction shows the most causal relationship with social capital. Also, relationship performance has a low level of meaning with social capital. Place branding has the most significant impact on social values and social solidarity. The amount of this effect is higher than the average. Place branding is also slightly more effective than the average on social security.

Polytheist social values are at the heart of social relations and arise from them. With the presence of social identity, security, cohesion, participation, and trust between people and management are achieved. Every space is identity-giving, and identity-giving becomes the basis for comfort and tranquility of the environment. Many of the city’s problems and injuries are caused by lack of common values, collective mentality, and collective understanding.

The neighborhood, as the main element that forms the structure of urban spaces, needs to be improved and have consistent values and characteristics to play a more constructive role. Neighborhoods with individual characteristics, specific features, and different spatial distinctions can have many qualities. One of the essential social and cultural qualities in providing, producing, and promoting common values is creating a collective mentality among the neighborhood residents.

Common values give a common understanding of the neighborhood, collective, and common experiences, and as a result, add to the quality of neighborhood life and urban life.

The results of this research showed that in the neighborhoods where there is a kind of identity and uniqueness in terms of architecture and body, in the neighborhoods where symbolic elements and special signs make the main identity of the neighborhood, and in the neighborhoods that have a distinct and special appearance, it dominates the neighborhood, it gets a unique symbolic and physical distinction from other neighborhoods, and as a result, it leads to formation and strengthening of common values.

The correlation between these components related to common values shows that all components are positively correlated. However, the amount of this correlation varies and includes very low to high values. Also, the degree of correlation between the factors that make up the spatial differentiation of the neighborhood is somewhat average. All relationships and correlation coefficients between components are constant and co-directional, meaning that one necessarily causes the other components to increase and decrease. In areas where the level of education is much higher, it decreases from the common level among people. This issue is related to individualistic superiority and insufficient recognition of each other’s values and attitudes. Regardless of the age and age of people in different neighborhoods, there are enough common values between people. In other words, common values are not very dependent on age, although they are not unaffected either. Also, with the increase of the residence time of people in a neighborhood, the commonalities and social values between people increase relatively.

The limitation of this research was the limited access to respondents in a wide and balanced range due to the coronavirus and lack of cooperation of all people.

It seems that further studies can be carried out in various cities with different architectural and identity characteristics and branding so that the impact of the amount and diversity of branding on social capital at the locality scale will be more evident.

The scale of the results of this study with related research, including the measurement of social capital in the city of Mashhad, shows that the level of prosperity of neighborhoods has a direct relationship with social capital. Moreover, even though in this research, an exact comparison was not made between the amount of social capital and the level of prosperity of the neighborhoods, a comparison based on evidence shows that the results of this research are compatible with other metropolises of Iran.

Also, the age and originality of the neighborhoods have a significant impact in this field. The research conducted in the neighborhoods of Isfahan and Tabriz shows that name, authenticity, and age are some of the most critical components of social capital. The results of those research studies can also be seen in the city’s neighborhoods under our study.

Cities that are memorable and travel destinations in people’s minds have high social capital, and the research conducted in Isfahan city; Kashan, Shiraz shows that being a brand of a city increases the amount of identity transmitted by its neighborhoods and increases social capital and in the current research, the neighborhoods that are tourist destinations have the characteristics of branding and a high level of social capital.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Tarbiat Modares University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MR: data collection, visitation, manuscript draft, and data analysis. MY: conceptualization, methodology, and final editing. MB: editing and methodology.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbaszadeh, S., Amani, M. M., Khazra Azar, H., SariBeigloo, J., and Ghasem., P. (2012). Introduction to the PLS structural equation modeling method and its application in the Behavioral Sciences. Tehran: Urmia University Press. [In Persian].

Altman, I., and Setha, L. (1992). Human behavior and environments: Advances in theory and research, Vol. 12. New York: Plenum Press. Place attachment.

Anguelovski, I., and Martínez, A. J. (2014). The ‘Environmentalism of the Poor’ revisited: Territory and place in disconnected glocal struggles. Ecol. Econ. 102, 167–176. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.04.005

Anton, C. E., and Lawrence, C. (2016). The relationship between place attachment, the theory of planned behaviour and residents’ response to place change. J. Environ. Psychol. 47, 145–154. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.05.010

Appleyard, D. (1979). “Inside vs. outside: The distortions of distance,” in Institute of urban and regional development (University of California). Working paper 307.

Avraham, E., and Ketter, E. (2008). Media strategies for marketing places in crisis: Improving the image of cities, countries, and tourist destinations. Butterworth Heinemann.

Ayse, H. O., Tarim, M., Delen, D., and Zaim, S. (2022). Social capital and organizational performance: The mediating role of innovation activities and intellectual capital. Healthc. Anal. 2, 100046. doi:10.1016/j.health.2022.100046

Braun, E., and Zenker, S. (2010). Towards an integrated approach for place brand management. Sweden: 50th European Regional Science Association CongressJönköping.

Decline, J. (2010). A Shared Vision on City Branding in Europe http://www.eurocities.eu.

Falahat, M. S. (2006). The concept of sense of place and its constituent elements. Art. Bull. 26, 66–57. [In Persian].

Fornel, C., and Lacker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistic. J. Mark. Res. 28, 39–50.

Fraser, T., and Naquin, N. (2022). Better together? The role of social capital in urban social vulnerability. Habitat Int. 124, 102561. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2022.102561

Fraser, T., Aldrich, D. P., and Page-Tan, C. (2021). An analysis of social media use and neighbor-assisted debris removal in houston following hurricane harvey. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 63, 102450. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102450

Furlan, R. (2015). Liveability and social capital in west bay, the new business precinct of doha. Arts Soc. Sci. J. 6, 116.

Granie, M. A., Brenac, T., Montel, M. C., Millot, M., and Coquelet, C. (2014). Influence of built environment on pedestrian's crossing decision. Accid. Analysis Prev. 67, 75–85. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2014.02.008

He, L., Howes.Aitchison, D. D., J. C., Lau, A., and Conradson, D. (2021). How do post-disaster policies influence household-level recovery? A case study of the 2010-11 canterbury earthquake sequence, New Zealand. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 60, 102274. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102274

Hikichi, H., Aida, J., Matsuyama, Y., Tsuboya, T., Kondo, K., and Kawachi, I. (2020). Community-level social capital and cognitive decline after a natural disaster: A natural experiment from the 2011 great east Japan earthquake and tsunami. Soc. Sci. Med. 257, 111981. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.057

Huang, L. S. (2006). A study of outdoor interactional spaces in high-rise housing. Landsc. Urban Plan. 78 (3), 193–204. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.07.008

Kang, B. (2006). Effects of open spaces on the interpersonal level of resident social capital: A comparative case study of urban neighborhoods in guangzhou, China. A dissertation submitted to the office of graduate studies of Texas A&M university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD.

Kavaratzis, M., and Ashworth, G. J. (2005). City branding: An effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick? Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 96 (5), 506–514.

Kearney, Anne R. (2006). Residential development patterns and neighborhood satisfaction. Impacts of density and nearby nature. Environ. Behav. 38 (1), 112–139. doi:10.1177/0013916505277607

Kemmis, D. (1995). The good city and the good life: Renewing the sense of community. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Lee, J. N., and Kim, Y. G. (1999). Effect of partnership quality on IS outsourcing success: Conceptual framework and empirical validation. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 15 (4), 29–61. doi:10.1080/07421222.1999.11518221

Lee, T. H. (2013). Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. 1 (34), 37–46. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2012.03.007

Lefebvre, H. (2009). “State, space, world, selected essays,” in Neil brenner and stuart elden, translated by gerald moore, neil brenner, and stuart elden (Minneapolis, United States: University of Minnesota Press).

Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 31 (3), 207–230. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

Manzo, L. C. (2005). For better or worse: Exploring multiple dimensions of place meaning. J. Environ. Psychol. 25 (1), 67–86. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.01.002

Manzo, L. C., and Perkins, D. D. (2006). Finding Common Ground: The Importance of place attachment to community participation and planning. J. Plan. Literature 20 (4), 335–350. doi:10.1177/0885412205286160

Marcus, C. C. (1974). “The house as a symbol of self,” in Designing for human behavior. Editors J. Lang, C. Burnette, W. Moleski, and D. Vachon (Stroudsburg, PA: Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross).

Monteil, C., Simmons, P., and Hicks, A. (2020). Post-disaster recovery and sociocultural change: Rethinking social capital development for the new social fabric. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 42, 101356. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101356

Perkins, D. D., Joseph, H., and Paul, W. S. (2002). Community psychology perspectives on social capital theory and community development practice. J. Community Dev. Soc. 33 (1), 33–52. doi:10.1080/15575330209490141

Pongponrat, K., and Ishii, K. (2018). Social vulnerability of marginalized people in times of disaster: Case of Thai women in Japan tsunami 2011. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 27, 133–141. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.09.047

Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 24, 1–24. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

Proshansky, H. M., Fabian, A., and Kaminoff, R. (1983). Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. J. Environ. Psychol. 3 (1), 57–83. doi:10.1016/s0272-4944(83)80021-8

Rainisto, S. K. (2013). Success factors of place marketing: A study of place marketing practices in northern europe and the United States. Winter Park, United States: Helsinki University of Technology.

Rapoport, A. (1982). The meaning of the Built environment (A nonverbal communication approach). Tucson, Arizona: niversity of Arizona Press.

Ratcliffe, E., and Korpela, K. M. (2016). Memory and place attachment as predictors of imagined restorative perceptions of favourite places. J. Environ. Psychol. 48, 120–130. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.09.005

Riger, S., and Lavrakas, P. J. (1981). Community ties: Patterns of attachment and social interaction in urban neighborhoods. Am. J. Community Psychol. 9 (1), 55–66. doi:10.1007/bf00896360

Rivlin, L. (1982). Group membership and place meanings in an urban neighborhood. J. Soc. Issues 38 (3), 75–93. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1982.tb01771.x

Ryan, R. (2005). Exploring the effects of environmental experience on attachment to urban natural areas. Environ. Behav. 37 (1), 3–42. doi:10.1177/0013916504264147

Sakhaei, H., Yeganeh, M., and Afhami, R. (2022). Quantifying stimulus-affected cinematic spaces using psychophysiological assessments to indicate enhanced cognition and sustainable design criteria. Front. Environ. Sci. 302. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.832537

Sanchez, R. (2004). Conceptual analysis of brand architecture and relationships within product categories. J. Brand Manag. 11 (3), 233–247. doi:10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540169

Shafter, C. S., Lee, B. K., and Turner, S. (2000). A tale of three greenway trails: User perceptions related to quality of life. Landsc. Urban Plan. 49 (3), 163–178. doi:10.1016/s0169-2046(00)00057-8

Sosik, J. J., Gentry, W. A., and Chun, J. U. (2012). The value of virtue in the upper echelons: A multisource examination of executive character strengths and performance. Leadersh. Q. 23 (3), 367–382. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.08.010

Sriram, V., Mersha, T., and Herron, L. (2007). Drivers of urban entrepreneurship: An integrative model. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 13 (4), 235–251. doi:10.1108/13552550710760012

Taylor, M. (2000). Communities in the lead: Power, organisational capacity and social capital. Urban Stud. 37 (5–6), 1019–1035. doi:10.1080/00420980050011217

Tuan, Y. F. (1977). Space and place: The perspective of experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Yeganeh, M. (2020). Conceptual and theoretical model of integrity between buildings and city. Sustain. Cities Soc. 59, 102205. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2020.102205

Yeganeh, M. (2015). “Educating designing an architectural model based on natural principles and criteria,” in International conference new perspectives in science education. 2015.

Yeganeh, M., and Kamalizadeh, M. (2018). Territorial behaviors and integration between buildings and city in urban public spaces of Iran’s metropolises. Front. Archit. Res. 7 (4), 588–599. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2018.06.004

Zare, Z., Yeganeh, M., and Dehghan, N. (2022). Environmental and social sustainability automated evaluation of plazas based on 3D visibility measurements. Energy Rep. 8, 6280–6300. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.04.064

Keywords: identity, function, distinction, the trust, social solidarity and social participation 100/0

Citation: Ramezi M, Yeganeh M and Bemanian M (2022) The role of place branding in promoting social capital in urban areas (case study: Ahvaz, Iran). Front. Built Environ. 8:889139. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2022.889139

Received: 03 March 2022; Accepted: 22 August 2022;

Published: 15 September 2022.

Edited by:

Jianxiang Huang, Tianjin University, ChinaReviewed by:

Mengdi Guo, Tianjin University, ChinaP Ravi Prakash, Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur, India

Copyright © 2022 Ramezi, Yeganeh and Bemanian. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mansour Yeganeh, eWVnYW5laEBtb2RhcmVzLmFjLmly

Mansour Ramezi1

Mansour Ramezi1 Mansour Yeganeh

Mansour Yeganeh