- SAAD Scuola di Architettura e Design, Università degli studi di Camerino, Ascoli Piceno, Italy

In a Casabella editorial from a few years ago, dedicated to the recovery of existing architectural heritage, Francesco Dal Co defined restorers as a corporation that considers itself the exclusive custodian of the knowledge, capable of scientifically resolving the conflicts that each restoration operation involves. Today, the perception is that restorers practice a profession different from that of architects: more than 20 years ago: Manfredo Tafuri noted that it was possible to observe a tendency toward the separation between restoration and conservation. Although the shared idea is that architecture is the result of successive modifications and never offers a stable image, the action of alteration of the built, especially the historicized one, takes place by appealing only to the scientific nature of a rigorous method that mortifies the creative act by losing the poetic root of our discipline. This type of conviction has led the discipline of architectural restoration through the tendency to make the cognitive phase coincide with the creative phase, in which the work itself suggests the design act. The project does not alter the image of the place or of the historicized asset but activates a process of crystallization of the existing, which proclaims conservation action as the only possible way: a heroic act of resistance. In the current urban scenario characterized by the “built paradigm,” the new seems to be conceived exclusively as a derivation of the existing. Augè defined the contemporary city as an immense ruin (“city worksite”) in which the unfinished and abandoned fragments of new constructions coexist with the ruins of the city of history and the ruins of the modern city. For these reasons, does it still make sense to distinguish the restoration project of a building from the project of a building? The contribution proposes a field of research that aims at the rapprochement between two disciplinary fields, architectural design and restoration, where the poetic root of the project returns to dialogue with the cognitive action on the asset and the application of scientific criteria for the consolidation and restoration of the elements.

1 Introduction

The growth of interest that intervention on existing structures has registered in recent decades, in Europe, can be easily explained from different points of view, starting with the economic one. Only in Italy, between 2008 and 2015, all construction-related sectors recorded a variable decrease from 20% to 60%, with the only exception of the item relating to interventions on pre-existing structures (Ance, 2016). According to Donatella Fiorani, this shift in investments is, in turn, the result of the convergence of various factors, among which we recall the most incisive: the greater awareness of sustainable soil consumption, the difficulty of proceeding (for much urban and industrial architecture, with building replacement practices), the unprecedented attention to accessibility and safety practices, the needs related to energy containment and seismic improvement, the need to counteract the decommissioning and abandonment of historic buildings, and to encourage tourist use (Fiorani, 2017). The practice of building replacement, moreover, has been, in recent decades in Europe, mostly limited to a few metropolitan areas and, in any case, has a rather limited diffusion compared to what is observed in the United States, where a progressive decrease in demolitions and reconstructions can be noted. In the major cities of China, where the phenomenon is growing, or in Japan, famous for its persistent innovative and traditional methods of renovation, conservation practices have positive consequences: among these, we recall the preservation of a stratified and highly anthropized landscape, the containment of the phenomena of transformation of popular neighborhoods into prestigious residential areas, and the permanence of places and their specific identity. The scenario described had repercussions on an arrangement, now consolidated for some time, according to which “designing” aimed at the creation of the new, at the functional recovery and restyling of recent buildings, and, at the limit, at the internal reconfiguration of minor buildings. The restoration was aimed at not only monumental buildings and valuable architecture but also ancient centers and widespread historic architecture. This division inherited the legacy of the “Charter of Athens,” dating back to the 1930s, dedicated to specifying the characteristics of the city and defining the principles to be respected in the restoration of monuments (Haspel, 2010). New buildings and monuments have been, for a long time, at the two opposite ends of a large “gray area,” in which interventions have mostly been made in a manner linked to the sensitivity of the clients and individual designers. The question of the project on the pre-existence and the antagonistic position established between designers of new projects and restorers (emphasized by the concrete interests of the profession), however, opens up complex scenarios on the theoretical level of study, which involve the very conception of architecture. On the one hand, there is the subjectivity of the designer, and on the other, the objectivity of the architectural pre-existence; on the one hand, the central role of artistic intuition and the poetic value of the project, and on the other, the structuring function of scientific investigation: inspiration versus method. The extraordinary quantity of historicized buildings present in Italy has favored the affirmation of a conservation culture as a heroic act of defense of the identity of the territories against the degenerative processes, which, in the last decades of the last century, afflicted the landscape, the city, and architecture. Gradually, the widespread belief developed was that is not possible to develop a virtuous interaction between the new and the old and that the two areas should remain separate. The prevailing conviction is that the project of the new can compromise and even destroy the existing one, causing the loss of those artistic values and of the relationship between places and architecture. Although the shared idea is that architecture is the result of successive modifications and never offers a stable image (its form is shown in the present but also shows its past), the action of alteration of the built, particularly the historicized one, has increasingly directed itself toward the application of only scientific rigor of a method aimed at the substantial conservation that mortifies the creative act and makes us lose the poetic root of our discipline. Gradually, the conservative solution (favored by the proliferation of areas of protection, specific institutions, and identity associations) has given us an unchangeable city where all the elements that make up the heritage, not only historicized, have undergone a process of crystallization. The new “passion” for everything that can offer a historical or even vernacular patina has not only overcome the desire to preserve historicized components but has also been extended to include those belonging to the Modern, late Modern, and even contemporary periods. In essence, a sort of renunciation has been affirmed of those effective and courageous transformation opportunities that have remained trapped within the reassuring logic of unchangeability. Yet, the city and architecture have always functioned according to successions of unstable equilibriums. It is not possible to postulate a state of equilibrium which is immutable over time: something which corrupts the previous condition inevitably happens; something which is in opposition to the given equilibrium (an earthquake, the destructive action of atmospheric agents, a flood, or a catastrophic event).

Even if conceived and designed to (re)exist, the architecture inevitably gives way to gravity, which will always get the better of it in the end. Architecture cannot be the art of perpetual and immutable balance. Its condition of static efficiency, somewhat ephemeral, is destined to surrender to natural gravitational forces. This does not mean that it ceases to exist. According to a different configuration, defined by a different condition of balance, the architecture does not disappear but is simply transformed as if it lived a series of different balances that follow one another over time, altered and modified not only by natural processes but also by the intervention of man, who uses it and transforms it by adapting it to new needs (Romagni, 2018). After all, architecture cannot be offered as a stable and unchangeable image. Although the main purpose is its construction, it never ends in this phase: a gap is always generated, never filled and with unexpressed potential, and consequently, the inevitable end (death) will always send us back to those images; the condition of the unfinished, from which it is born. Francesco Venezia gives us an example of the construction site of an architectural structure; it is, in fact, the image of the unfinished work, but it is also, in some way, the anticipation of what will be the ruin of that architecture. The interruption of the condition of equilibrium necessarily involves a transformation that generates a more or less evident contrast with the previous condition. Architecture is always an operation of contrast: it is against nature, it is founded in the ground, it modifies the earth’s crust, and it fights against gravity. Even the city is an ecosystem which, transforming itself through architecture, proceeds by continuous contrasts. The loss of balance is the essential condition of its existence, and each event will induce variations to find a new state. Franco Purini writes that any modification of the existing can follow two alternative paths: it can be, in a harmonious way, « as an ideal continuation of the existing itself, in the sense that the territorial-landscape, urban and architectural text can be continued, in accordance with its structure, with the spatial contents that the structure expresses and with the architectural language in which it is solves » or in contrast « on the other hand, any transformation could be able at the same time to contrast and also to subvert the sense of the territorial-landscape, urban and architectural text, introducing into it divergent or even opposite values with respect to the present ones. In summary, the existent cannot be considered only as something that must be continued through the reconfirmation of the modalities of its constitution, but as an entity in constant evolution that can produce, in the limit, even radical alternatives to its own structural and formal arrangement» (Purini, 2012). From a methodological point of view, the urban development of a historic city takes place through successive transformations. However, there is a key to understanding the basis on which it is possible to trace a constant of balance, of unchangeability, in specific urban fragments that can be isolated (by characteristics) within the city. This condition essentially belongs to the language and to some morphological aspects according to which the transformations take place: if the overwriting of the signs of the city is manifested according to a planimetric reading, the urban image of these parts of the city reveals a vision somehow continuous, which seems to mark an illusory idea of stable equilibrium. The contradiction between these two antithetical readings is strongly evident in the historic urban centers. Most of the transformation processes (extensions, elevations, and closure of local streets) took place while preserving those characteristics of instantaneousness, understood as a uniform sense of appearance and intensity, as a way of offering materials to the observer, which characterize our historic centers. Continuity can be found in the architectural language and, therefore, in the analogy of the technical-morphological elements, such as the openings (in terms of shape and size), the roofs, and all those aspects that refer to the characteristics of the culture of the building.

2 The worksite city

The relationship between the past and present seems to be contradictory in some ways (even if similar): on the one hand, as suggested by Augè, the comparison with the historical ruin is an aesthetic temporal experience of absolute time which refers to the past and which, therefore, retrospectively recognizes the ruin as a function of history. On the other hand, accepting the contemporaneity of architecture and the complexity of the modern city implies a reflection that points in the opposite direction: toward the future. In fact, very often, the urban dynamics do not interact actively with the historic ruin, almost excluding it from the transformation processes and producing oases around which the city is constituted or marginalized. This aspect no longer concerns only monuments and historic centers but is also extending to post-industrial buildings or unfinished structures of the contemporary age: while the historical monuments are, in fact, invested almost exclusively by the flows of the tourism industry, the others are left to their own destiny in the suburbs of cities or cut out within the urban settlements. In any case, both seem extraneous to the city; it does not absorb them. On the contrary, it almost rejects them, despite being an integral and structural part of it. We continually see the formation of historical ruins and contemporary rubble whose inevitable destiny is being abandoned rather than being attacked, used, inhabited, and transformed. It seems that the romantic ruin (the ones of Ruskin’s sublime) is countered by a sort of opposite ruin which, due to the temporal contraction with which the transformations take place, is, in fact, already a ruin. It is as if the historic building was falling into ruin and the contemporary rubble was already born ruin. This conflictual co-presence characterizes the large construction site of the contemporary city (Ugolini, 2010). Again, according to Marc Augè, the contemporary city seems to be a continuous construction site in which we see the simultaneous presence of construction and destruction in the conflictual relationship between contemporary time and historical time: the incessant rhythm of the first contrasts with the slow and inexorable time of the second ones (Augè, 2004). The sum of the various occasions of scarce or complete non-use of historical ruins and contemporary ruins are not exceptional episodes in the urban settlements but are a recognizable and structural characteristic of the city. If the city of the present had chosen the Koolhaasian junkspace as the result of modernity, the contemporary ruins can be considered the descriptive paradigm of the changing urban landscape in which it equally coexists with the historical ruin in the same space. Augè’s extreme description, according to which everything is already built and is the subject of a conservation process that prevents the possibility of transformation to the new demands of the contemporary world, enhances the affirmation of this scientific method of enslavement to the existing and proclaims the growing affirmation of the related professional figures. The architectural project and its poetic roots are relegated to a cosmetic role in the processes of direction and control of the transformations of the city and of the architecture. If we then identify the idealized urban scenario as an immense ruin (in which recently built unfinished and abandoned fragments coexist with the ruins of history and the ruins of the late Modern period) and if everything exists in its condition of non-use, does it still make sense to distinguish the restoration project of an urban portion or a building from the architectural project?

3 Interaction methods and devices

Intervention in the existing should represent an unavoidable condition that invests many of the areas of creativity in which we see the need to redefine the traditional categories of intervention. In architecture, for example, the growing complexity constituted by the presence of large quantities of “unfinished” and “ruins” on the territory makes it necessary to rethink those ancient devices for manipulating the built environment whose objectives no longer coincide with the new needs. A first consideration concerns the risk of confusing terms and actions already in use and strongly applied to the existing operations such as “restoration” (defined as an activity linked to the maintenance and conservation of a historic artefact), “reuse” (as the reuse of ancient material in more recent constructions), and “recycling” (as the reuse of waste materials and transformation of the raw material into a finished product); these are applied to the historical ruin or the recently built, unfinished, or decommissioned, hardly defining anything specific, and they often coexist. The application of the concept of “recycling” appears more complex and is still difficult to define when it invests in urban settlements and systems built with the intention of being able to regenerate them with more complex operations of reconstruction and regeneration (Romagni, 2016a).

4 A multidisciplinary point of view

An incursion, for example, in the musical field, can be useful for understanding the progression of the transformation intervention with respect to an existing asset, building, or piece of music. An interesting example can be represented by the “recycling” operation, understood as the reuse of waste materials and transformation of the raw material into a finished product. It is a type of action that has a lot in common with the idea of music remix: it literally means re-modification. It is an art of recombination of elements coming from different sources that are mixed together to create a new composition. Observing the musical production derived from the practice of remix in recent years, we can distinguish different forms of modification with an increasing character of alteration: a first form of remix that we could define as “extensive”; it is that one which starts from a piece and creates a longer version through the introduction of instrumental parts to make it more mixable with other pieces. The original composition (or the original asset) is clearly recognizable but undergoes slight variations of extensions of parts characterized by different rhythms and sounds that can be easily combined with parts of other songs. A different form of remix, “reflexive,” can be the one that involves the addition or subtraction of material from the song or from the starting object. We act by introducing new elements or removing significant parts without losing the essence, quality, and recognizability of the original piece: parts of material are added or deleted, but the original traces are largely left intact to be recognizable. Proceeding with an even higher level of modification, we speak of a “selective” remix. This type of intervention contests and modifies the aura of the original autonomy of the piece while maintaining the name of the product: it acts on the deconstruction of the piece or of the asset, leaving the title as the only recognizable thing of the original, preserving the authorship. To be clear, in musical terms, this type of remix can always count on the “authorship” of the original song. Extended to other cultural fields, this type of remix consists in conceiving a sort of second level or meta level in which the source is declared but hardly recognizable. We must know and intuit that we are listening to a remix of something pre-existing to avoid considering the composition as entirely new with the risk of becoming plagiarized. The authorship of the work will be shared by the original author and the remixer. In the book “Remix Theory: The Aesthetics of Sampling,” Eduardo Navas defines a fourth form of “regeneration” remix that moves beyond music. Like the other forms of remix, it makes the original sources of material evident, but unlike these, it does not necessarily use references or samples to validate their cultural form. The elements are selected according to their functionality and reassembled toward something totally new. In essence, he selects parts from different pieces and recomposes them in a new way without being able to maintain the original sense of the “original body” but only allowing to intuit fragments recomposed in a new form. This marks a split of authorship that frees itself from that of the original author, becoming a new subjective work closely linked to the cultural recognition of the new author: the remixer (Navas, 2012). The “regenerative” remix is more powerful as it works as a link of recycled material that has value only when it continues to circulate: it defines a process, a “cycle,” which, instead of responding exclusively to the need to recognize cultural forms, becomes a programmatic and aesthetic tool.

5 Cognitive phase vs. creative phase

This incursion into the musical field is useful for us to understand the critical issues that arise in terms of recognizability of the original asset and authorship when we intervene with the intention of modifying an urban environment or an existing architecture. Despite the difficulty with which we are forced to accept what we can define as the “built paradigm” in which architecture, for the first time in history, seems to be able to be conceived as a derivative of the existing, the action of the “project on project” (of creative and not just technical research) takes on a deeper and more incisive meaning by claiming the ambition to act as a model of a new possible strategy for dealing with (all) architecture: overcoming the ideological impasse of conservation and pushing beyond the confines of the discipline of restoration by activating a series of recycling actions capable of triggering new relationships and attributing new meanings to the existing architecture and its context. If we had to think about how the architecture of historicized urban parts has been intervened in the last few decades, we can only see the exclusive action of conservation both in terms of new urban and architectural relationships. Renato Bocchi notes how, almost always, in the interventions on the architecture of our historic centers, we saw the passage through the traditional formulas of architectural replacement or restoration (Bocchi, 2013). Yet, the need to adapt the existing to the new needs of improving the living conditions, fruition, and protection of urban spaces and architectures makes it necessary to conceive more complex operations than simple recovery: strategies which allow, on an urban scale, to redefine new and more complex systems relational and, on the architectural scale, to operate degrees of “increasing alteration” to guarantee the multiple levels of adaptation and a real re-functionalization even if not typologically compatible. The comparison with the new mobility systems, the connections to the environmental systems, the escape strategies, and the quality of the public spaces amplify the range of action of the project by seeking new relationships at the surrounding scale. In the same way, the impossibility of pursuing exclusively “compatible” re-functionalization makes more articulated and complex levels of alteration of the existing structure necessary than conservative restoration. Francesco dal Co, in a Casabella editorial a few years ago, dedicated to the recovery of the existing, defined the restorers as a corporation that considers itself the exclusive custodian of the knowledge of some techniques capable of scientifically resolving the conflicts that each restoration intervention entails (Dal Co, 2013). In fact, the common belief is that restorers and specialized engineers practice a profession different from that of architects. It is a distinction already noted more than 20 years ago by Manfredo Tafuri, who noted that it was possible to observe a tendency toward the separation between restoration (also understood as a search for a poetic value in the intervention on the existing) and conservation understood as an exclusively specialist operation (Baglione and Pedretti, 1991). Ernesto Nathan Rogers makes a distinction between “specialist” architects and “total” architects, claiming the need to reinsert the partial intervention, on a small scale, within the quality of the highest scale of control of the entire architectural organism (Rogers, 2014). It is a need manifested not only by the “planning” architects but also by the “restoring” architects. Claudio Varagnoli, for example, advocates the search for a unity of method between restoration and design to highlight the importance of the evocative power of the project (Varagnoli, 2007). Yet, the reassuring affirmation of the discipline of architectural restoration has led to the application of a method according to which the cognitive and creative phases have become so close that they are no longer distinguishable: the cognitive phase has assumed such a strong importance on the basis of which it is the work itself that suggests the design act.

The project does not alter the image but activates a process of crystallization of the existing, which proclaims the action of conservation as the only possible way: a heroic act of resistance. However, if the need to intervene on the existing no longer concerns the architectural monuments of history, the centers with a strong character of intensity, instantaneousness, and immediacy, but extends to a large part of the territory, we need to go beyond Brandi’s technique of restoration, which tends to atrophy the creative act. It is necessary to seek those forms of “compensation” as added value, following the path traced by great masters such as Carlo Scarpa in the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona (1956–64) or by Franco Albini in the museum layout for the Palazzo Bianco in Genoa (1949–51). We all (and it could not be otherwise) share the importance of knowledge in any field of research and design. From knowledge, we understand the real values, the reasons for the transformations, the state of conservation, and what is authentic and what is not. It is an exciting exploration which, however, must represent a first step toward coherent but innovative project ideas. The clear split between these two ways of being an architect has come out in recent decades. There are numerous examples of architects who, in Italy, starting from the 1930s and after the war, dealt with the theme of juxtaposing the new with the old. It is enough to recall the intervention by Ambrogio Annoni for the church of San Vincenzo in Galliano (1934), the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona by Carlo Scarpa, or the museum installations by Franco Albini for the Palazzo Bianco (1949–51) and the Palazzo Rosso (1952–62) in Genoa. Approaching the contemporary context, we can recall the intervention for the Castello di Rivoli by Andrea Bruno (1978–86); the Gibellina Museum by Francesco Venezia (1981–87); the houses of S. Michele in Borgo in Pisa by Massimo Carmassi (1985–2002); the Medici stables of the villa of Poggio Caiano by Franco Purini, Laura Thermes, Francesca Barbagli, and Piero Baroni; the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena; and the layout of the archaeological museum by Guido Canali (2003). We can also mention the work of Werner Tscholl with the projects for the Reichenberg Tower (2000) and for Castel Firmiano (2003–2006). Even more evident in Europe is the search for a virtuous relationship between old and new that we find in all the work of important design studios such as that of Nieto and Sobejano. Conservation through an operation of a philological nature that preserves the material consistency and the formal characteristics of the existing architectural organism minimizes the risks of compromising the value of the asset. The wish to alter, to act through the creative act on the existing asset, on the other hand, brings the danger of compromising, of making the value of the new prevail over the old, of making the original values of the work no longer perceptible. This implies the assumption, by the architect, of greater responsibilities in which the choices and judgments of a subjective nature require a high level of sensitivity and preparation. It is, therefore, necessary to consider compositional tools capable of playing a control action, of activating an alarm of “creative excess,” toward a restoration project that does not give up on building a virtuous dialectic between old and new and toward a real adaptation and re-functionalization of the opera. Claudia Conforti identifies in the control of the interaction and mutual necessity of three design actions, measuring, grafting, and composing, the possibility of defining a “unit of method” that allows a virtuous relationship between the architectural project and the restoration project (Conforti, 2015). Giovanni Battista Cocco and Caterina Giannattasio summarize the meaning of the three terms: «“Measuring” has several meanings: first of all it refers to a dimensional fact, referring both to the building on which work is done and to the weight that the contemporary project assumes on it; but it also means evaluating, therefore, expressing a judgment on the values of the factory to guide the intervention and, at the same time keep it within the right limits; and it also means commensurate, or compare the work with other works to recognize their values and, in the presence of gaps, to include the structure and form of the missing text. “Grafting” is the term which constitutes a point of passage between knowledge and action. Of predominantly botanical derivation, it underlines the bond that, in the imaginative process, is established between Ancient and New to create a new work and, in some cases, to give it a new life. “Composing” means relating a set of elements chosen to build a homogeneous fact and such that each part that constitutes it finds its greater expressiveness in the whole; in this sense, “composing” finds meaning not only in its formal dimension (in which several objects or figures make up a new shape or figure) but also in its cultural character, which refers to the construction of a unity of thought, around a given or imagined theme, starting from a series of needs, expectations and limits of a community» (Cocco and Giannattasio, 2017). It is possible to define some architectural design devices that allow us to formulate intervention strategies that enhance the autonomy and clear recognition between the preserved part and the design intervention by defining relationship criteria and control of the increasing level of alteration: the archetype, the joint, and the fragment.

6 The archetypes: The zero degree of the existing

The intervention on the existing with the aim of reactivating the life cycle of an architectural project on the basis of new contemporary needs opens up a question related to the strategies that the architectural project must seek in the relationship between the existing building and its insertion into the context. Redefining the functional program of an architectural project always translates into the modification of its spatial characteristics: it means altering a given condition through architectural devices that are able to respond to a new need for use and control and, at the same time, the new relationships that are established between the existing material and the new at all scales of the project, from the detail to the urban character. However, it is impossible to define a single intervention strategy due to the fact that the architectural heritage is very varied and characterized by different building typologies in terms of space, structure, and integration into the urban settlements. This complexity can be investigated by developing a synthesis process which, similar to the methods for solving mathematical problems, can lead the question back to a known datum for developing an analysis aimed at recognizing possible strategies for the existing. It means to operate a conceptual deconstruction of architecture to arrive at a limit condition, coinciding with the archetype (Marras, 2013), in order to operate a reading that puts the spatial characters into a system with the tectonic aspects of the architectural artefact. By making this synthesis, we can implement a simplification aimed at recognizing two basic archetypal categories that define the existing architectural heritage: the enclosure and the frame. Although this is a simplification that does not take into account very complex and less common situations, the vast majority of architectural realities present in the urban settlements belong to these two categories. On the one hand, the enclosure is the archetypal form that mainly describes the historical architecture, widespread in the original parts of the cities, characterized by the load-bearing masonry as structural typology (Strappa, 1995). On the other hand, the frame is the constructive principle that characterizes the most recent architectural production and which involves both the field of residential construction and a large part of the industrial and public architecture (Cao, 2016). Bringing the forms of the existing back to the limited condition of the archetype represents a useful condition for determining the transformation potential of an artifact and allows to understand what possible alterations the project can produce through an action on the elements that the archetype possesses by its nature (Marras, 2013). Just as the process of degradation and disintegration brought about by time leads architecture back to its essential nature (to the form of its archetype) (Romagni, 2016b), the operation of synthesis of existence toward its zero degree is configured as an action of subtraction, aimed at bringing the artefact back to its original condition by revealing the most intimate truth of its conception and revealing its structural idea. In this condition, architecture reveals its capability to transform itself and generate relationships with the new parts and with the context. In all the case studies described in the following sections, it is clear how this action of subtraction is configured as a preparatory act for the construction of dialogue strategies between the existing and the new, constituting the starting point of a process which allows postulating compositional principles and strategies aimed at redefining the physical relationships between the old material and the new and between the built architecture and the surrounding space.

6.1 The alterations of the archetypes: The relationship between the shell and structure

If the structural aspect influences the relational properties of the architecture, the link between the structure and the shell establishes the substantial difference between the archetype of the enclosure and the frame: in the first case, in fact, the tectonic component (made up of continuous structural elements) and the shell coincide by establishing a condition of unavoidable reciprocity. In the second case, there is a hierarchy between the two components in which the distinction between the structural system and the shell is manifested, which are autonomous and potentially unrelated (Gritti, 2016). However, in addition to the static function, the tectonic conception of an architectural organism also has an important value from a compositional and expressive point of view. This reflection can be conducted by investigating the ways and means according to which the architectural artifact manifests itself and therefore communicates: to the condition that holds together the structural question and the shell in the paradigm of the enclosure is also added the role of expressive value of the architecture itself. There is, therefore, a plurality of meanings which, through an indissoluble bond, concentrates the triple role of bearing, containing, and communicating in the element of the wall. Therefore, the wall, the unitary element of the enclosure, also becomes a vehicle of figurative values and expressive meanings (Benevolo, 2006). Returning to the example proposed by Venturi of the Palazzo dei Capitani in Ascoli Piceno, it is easy to identify in the element of the wall the place where the signs of the transformation are deposited, where the characters of history and its overwritings manifest themselves clearly by becoming a vehicle of memory and of narration (Venturi, 2010). Furthermore, in addition to the static meaning, the masonry of the enclosure also has the role of communicating its materiality and consistency: the support element is heavy, it is firm, and its thickness communicates solidity and stability. The alteration of the masonry support can reveal its consistency and its thickness: when the continuity of the wall is compromised (by making new openings and invalidating the continuity of the enclosure or by compensating for the rips caused due to the state of deterioration), we can act on the exaltation or denial of this fact. It is interesting to note how this logic crosses the history of architecture, starting from classicism, where the proportions of the Doric column returned an image of stability made even more evident by the shape of the capital, the release point of the strengths. Just like all early Christian Byzantine and Romanesque architecture, it is characterized by the figurative strength of the wall, capable of isolating the earthly world from the spiritual dimension contained in the internal space (Benevolo, 2006). Developing a strategy for the alteration of historical architecture characterized by the presence of a perimeter wall structure implies the need to work on this support by contaminating it, interrupting it, and violating it, with the signs and forms of new architectural elements (Figures 1, 2).

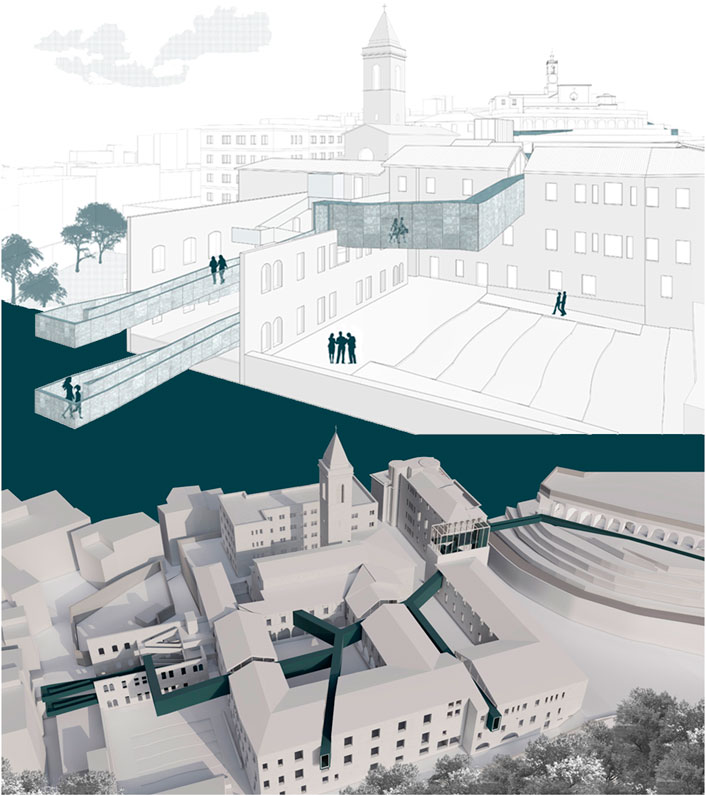

FIGURE 1. Didactic work from the Laboratory of Urban Planning held by Prof. L. Romagni, SAAD Unicam, 2017–18. Case study: Trisugno, Ascoli Piceno, Italy. Students: Ludovica Crispi and Rita Pettinari.

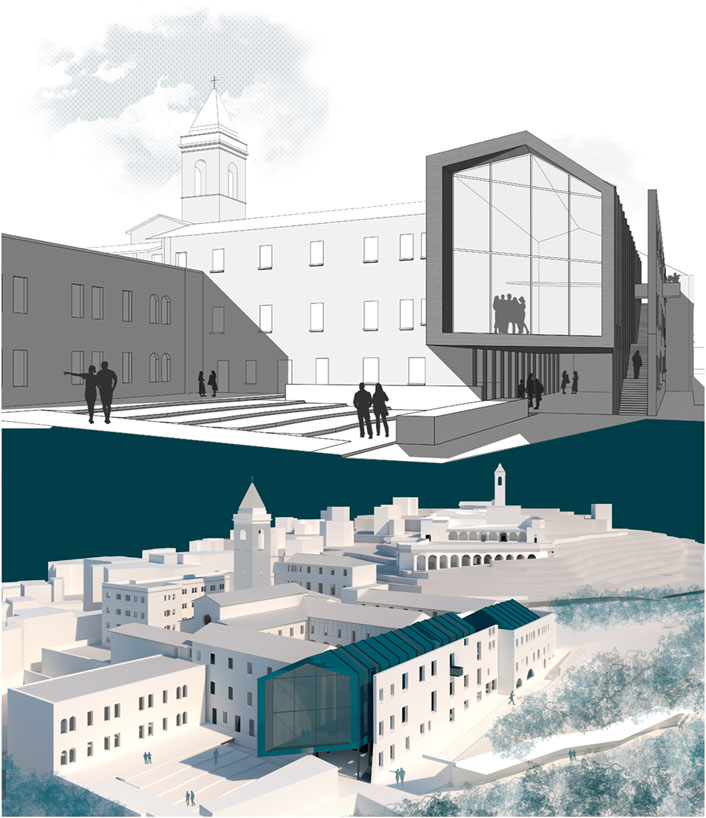

FIGURE 2. Didactic work from the bachelor thesis workshop “Grafting” held by Prof. L. Romagni, SAAD Unicam, 2021. Case study: Sant’Angelo Magno complex, Ascoli Piceno, Italy. Student: Anna Diomedi.

A clear example of this strategy can be found in the Dovecote Studio in Suffolk (United Kingdom), where architects Haworth and Tompkins have inserted an autonomous structure in corten iron inside a ruined Victorian dovecote to host an atelier for artists. The existing masonry confirms the identity of the historic building and builds a virtuous relationship with the new element inserted inside. Another possible typological alteration, referring to the manipulation of the shell in the archetype of the enclosure, concerns the theme of the roof: in almost all cases, this element represents exclusively a connecting element, a component whose sole function is to close the container horizontally and protect it internally from external agents (Ponti, 2015). This condition opens up many possibilities for intervention that allow the roof to be reconsidered no longer just as a limit between inside and outside but as a potential space that can be used to satisfy new needs (Figure 3). There are many examples that have investigated this theme and strategies in a different way, such as the project in Sheffield by the Project Orange group: an example of how the covering element, from a simple surface, is transformed into a three-dimensional container resting on the pre-existing. Similarly, in the project for the CaixaForum in Madrid by Herzog and de Meuron, the corten volume, placed on top of the old building, generates a new spatiality that overturns the traditional concept of roofing. In a different way, in the market of S. Caterina in Barcelona, Miralles and Tagliabue seek a different perception of the interior through the introduction of a completely autonomous roof detached from the existing body. Observing the archetype of the frame, we can see how, in addition to being a regulating element of the space through the imposition of its geometric matrix, this also represents a compositional and aesthetic principle. The experience of the Modern gives us many examples that highlight the use of the module as an absolute value in technological and expressive terms (Moneo, 2004). If, for the enclosure, the possibilities of alteration pass through the violation of the wall or the reformulation of the covering element, the frame can figure out multiple solutions and strategies of alteration. According to the principles postulated by Le Corbusier on the concepts of plan and free facade, the frame has a more flexible nature that allows to interpret the structural apparatus and the shell as distinct systems, offering a higher degree of freedom than the enclosure model (Grimaldi, 2016).

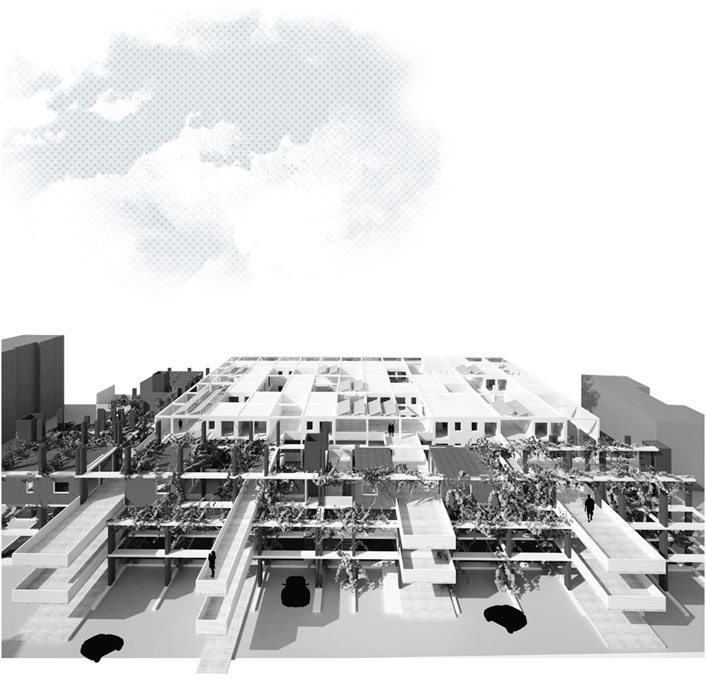

FIGURE 3. Didactic work from the bachelor thesis workshop “Grafting” held by Prof. L. Romagni, SAAD Unicam, 2021. Case study: Sant’Angelo Magno complex, Ascoli Piceno, Italy. Student: Mirco Ghitarrari.

We can distinguish two opposite conditions through which the image of the frame can reveal itself and communicate. The first case is about the design possibilities allowed by the autonomy of the shell: relating directly to the outside, this element can play the fundamental role of expressive means of architecture and can be conceived in a completely autonomous way among the pre-existing frame which assumes the less relevant role (Moneo, 2004). The image of architecture is increasingly becoming a fundamental aspect within the project, and the role of the envelope is a fundamental factor in building a system of relationships with a strong scenographic and communicative vocation (Purini, 2001).

In a different way, the renunciation of the shell device also assigns to the structural composition of the frame the aesthetic value of the architectural object, making it (in this condition) analogous to the archetype of the enclosure, where the tectonic component is not released from the figurative restitution of architecture. The architectural production of the last century offers us important examples in which the conception of the structural frame also acquires an aesthetic value. Starting from the project for the Farnsworth House up to the American examples of skyscrapers, Mies Van der Rohe reveals the structural truth of the system by eliminating the opacity of the shell and reaffirming the regular founding matrix even in the detailed components (Venezia, 2011). We can say that there are two antithetical intervention strategies: on the one hand, the frame acts as a support for the shell device, which plays the role of revealing expressive values, and on the other, a mode that seeks the formal and aesthetic qualities of the frame in its geometric matrix.

6.2 The alterations of the archetypes: The relationship between the inside and outside

Further consideration can be made by investigating the relationship that the tectonic nature of architecture allows to establish with the external space. The enclosure, due to its structural continuity, establishes a clear difference between inside and outside and describes a certain perimeter, generating a condition of inclusion. In the opposite way, the frame, made up of punctiform elements, dissolves this limit by becoming totally permeable and defining a direct continuity between what is inside and what is outside. Starting from these characteristics, we can state that the enclosure describes a perimeter, while the frame defines an ambit. The relationship with the outside determined by the structural conception of architecture can also be further investigated in the different definition of the way to touch the ground, where the distinctive features of the two archetypal typologies examined emerge further. To the strong limit described by the enclosure (defined by a continuous structure) corresponds a conception of architecture strongly rooted in the ground (Di Domenico, 1998). On the contrary, the grid of the frame maintains a less binding relationship with the ground by leaning on it in a punctual manner. On the one hand, therefore, there is a closure toward the outside (the enclosure), and on the other, the permeability (the frame). It is also interesting to note how, by inverting the terms of the analysis process, the empty space takes different meanings and values in relation to the built system to which it is opposed. We know that architecture, as a system made up of walls, diaphragms, attics, and roofs, has the ability to define its reciprocal (the void). According to its structural conception, the enclosure is a device that can generate a vacuum, obtained by difference among the closed system of its perimeter which establishes its shape. This feature is easily found in the system of open spaces and squares that identifies the historic Italian settlements, where the principle of the enclosure emerges with force and influences the structure of the urban form. On the other hand, the situation determined by the typology of the frame is different. The certain limit that the enclosure generates is canceled, and the frame, conceived as a spatial grid, does not have the strength to build a defined space but has the capability to measure it by imposing its geometric matrix, which is also virtually projected the outside. It defines a potential rhythm, and it becomes the metric of space and, therefore, its measure (Cao, 2016).

On the basis of these analyses aimed at defining the nature of the archetype in the relationship between internal and external space, we can investigate the possibilities of alteration of these devices toward the construction of new relationships with empty space, reconfiguring the urban meaning of the existing. For what concerns the alteration of the enclosure, the most interesting aspect is represented by the manipulation of the masonry, by making cuts and subtractions, renouncing the continuity defined by the contact between open space and structure. The empty space can penetrate through the pre-existence which, while maintaining its structural connotations, is reinterpreted by generating a new physical continuity with the context on which it stands (Figure 4). One of the most emblematic examples of this operation is represented by the cut generated on the basement of the pre-existing building in the project for the CaixaForum by Herzog and de Meuron. The structure, made up of continuous load-bearing masonry (and therefore referred to as the archetype of the enclosure), is raised from the ground, redefining the bond relationship with the ground and producing a total permeability between the building and the square in front. A further way of reworking the relationship between enclosure and empty space is constituted by the definition of a device that has the function of mediating the passage between the outside and the inside: an architectural element capable of generating a sort of filter space between the open environment (the void) and the interior described into the enclosure.

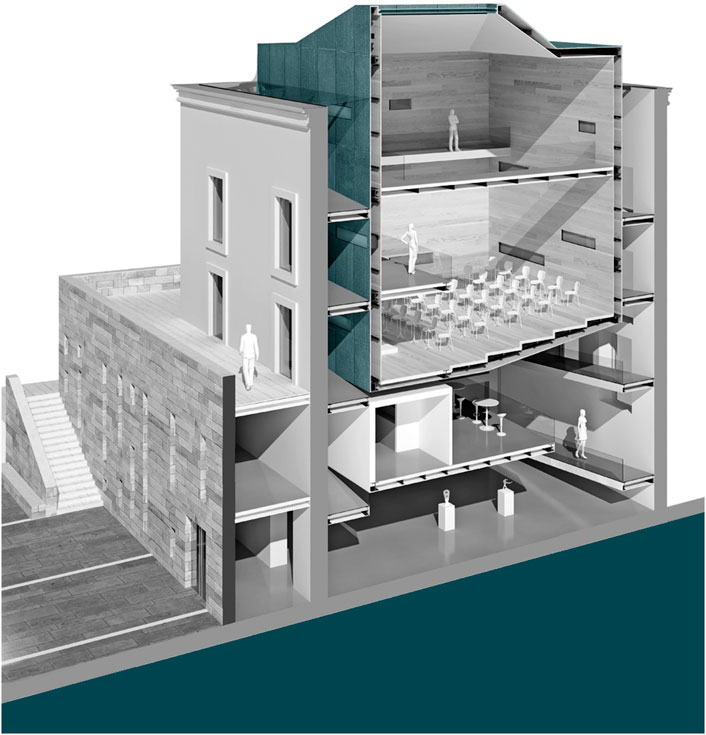

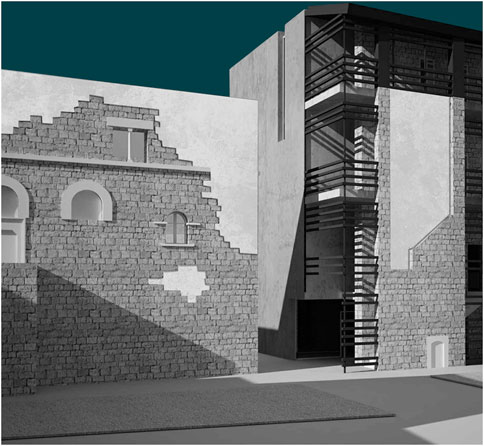

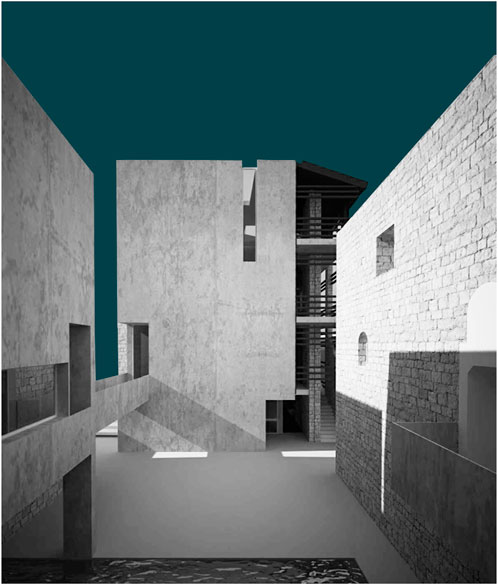

FIGURE 4. Didactic work from the bachelor thesis workshop “Grafting” held by Prof. L. Romagni, SAAD Unicam, 2021. Case study: Sant’Angelo Magno complex, Ascoli Piceno, Italy. Student: Francesco Gatti Venturini.

In the early years of the 20th century, Walter Benjamin expressed the concept of space in between, identifying it in the element of the threshold as a physical area in which change and passage are understood (Spirito, 2015). This intermediate zone represents the point of tangency between exterior and interior, the physical and conceptual element that describes the transition between inside and outside. Manipulating and designing the shape of the threshold represents a useful tool for redefining and altering the relationship that the shape of the enclosure imposes between the outside and the inside. This spatial device, although not referring to interventions on pre-existing contexts, has distant origins, and the examples can be found in the classical architecture: the typology of the temple, for example, is characterized by a central cell (which precisely identifies the enclosure) surrounded by a peristyle which performs the same function of filter space between the inside (the naos) and the outside. We could say, in extreme, that the form of the temple is solved by the ancestral and archetypal figure of the enclosure and that the element of the colonnade, performs as an intermediate space capable of mediating the passage between the outside and the inside, between the void and the built, between the sacred and the profane. In this sense, applying a filter device to the enclosure necessarily translates into the hybridization with elements of different nature and structural characteristics. If the enclosure identifies a close border, the intermediate space must necessarily be produced by an architectural device that makes permeability and continuity with the outside by altering the continuous and closed structure of the enclosure.

An example that clarifies this strategy can be found in the Town Hall Hotel 5 project by RARE Architects, where the pre-existence is wrapped in a differently perforated skin that allows visual continuity with the outside world, which is always diverse and complex. The distance between the skin and the pre-existing architecture defines the filter space, which mediates the closing relationship of the historic wall with the external space, also functioning as an entrance element on the ground floor and as a living space when the distance is large enough to allow it. It is a strategy analogous to the relationship between the structure and the independent shell: an action of juxtaposition of elements with different characteristics compared to the pre-existence that serves as a support. The possible alteration of the relationship between inside and outside in the archetype of the enclosure needs to define a system capable of mediating this relationship or even canceling it (as highlighted in the example of the CaixaForum), introducing a more or less clear-cut and passing from a closed system to one characterized by different degrees of permeability. For what concerns the archetype of the frame, this relationship takes on different connotations. As described earlier, the frame has the characteristics of permeability and continuity that put the external space in communication with the internal one, and the entity of this capacity is defined by the design of the shell. Being potentially independent of the support structure of the frame, the manipulation of its degree of opacity represents the parameter that allows to formulate different types of relationships between exterior and interior: the greater the transparency, the more direct and stronger this relationship will be (Lambertucci, 2013). In its essential condition, when the frame is physically manifested, we could say that the shell does not actually exist (Purini, 2001). In this way, the architecture reveals its minimal conception, the contact between the external void and the interior is total, and its permeable nature is enhanced by renouncing to build an internal space (Figures 5, 6). In the opposite way, the question of the internal/external relationship can be addressed by recognizing the frame as the generating element of the empty space. As a result of its structural conception, in fact, it is organized according to a regular structure which establishes an ideal matrix (even before being physical) that can be replicated outward: the geometry of the frame is projected outward, defining the structure of the empty space, in which the alignments of the matrix become the lines according to which the composition of the open space develops, and the geometric regularity constitutes the measure of the design of the ground and its elements.

FIGURE 5. Master thesis project “Riciclo di uno scheletro urbano: ex palazzo di Vetro, Ancona,” 2013–14. Student: Letizia Camilletti. Supervisor: Prof. U. Cao. Co-Supervisor: Prof. L. Romagni.

FIGURE 6. Didactic work from the bachelor thesis workshop “Scheletri archittonici” held by Prof. L. Romagni, SAAD Unicam, 2014. Case study: ERAP complex in Pennile di Sotto quarter, Ascoli Piceno, Italy. Student: Oana Claudia Iacob.

7 The fragment: Graft on the existing

If the first act in the process of building the relationship between ancient and new coincides with an action of deconstruction focused on the first term of the binomial, the insertion of the new into the existing prefigures an additive-type action. The compositional operation that best describes this type of action is grafting (Zucchi, 2014). It is a practice that presents many analogies with the natural sciences and, in particular, with botany: there is a host organism (the pre-existence) which is altered, with different entities, each time according to the needs, by an “alien” element that interacts with it. Pre-existence and grafting dialogue and function together, forming a unicum with a new identity and its own characteristics defined by the combination of very different and contrasting elements (Giannattasio, 2017). While generating a condition of unity as a whole, the parts that make up the grafting operation continue to be independently recognizable: the pre-existence retains its original founding characteristics which clearly differ from the new element that contaminates it. It is not a question of building a hybrid, which does not presuppose the juxtaposition between an existing body and a new one, but rather a genetic manipulation between two different species that conform to a unicum in which the two parts are no longer recognizable (Giannattasio, 2017). Continuing the analogies with the world of natural sciences, the practice of grafting shows greater analogies with the concept of parasite (Marini, 2008), defined as a differential operator of change which maintains its linguistic and spatial autonomy but is, at the same time, linked to it by a state of necessity. However, unlike the parasite, the practice of grafting presupposes a condition of mutual necessity: the pre-existing element and the host collaborate and make use of each other. In fact, if the graft does not bring lymph to the graft, it fails. So, in architecture, if the new does not feed the old, the project has not fully achieved its meaning (Giannattasio, 2017). On the basis of these specifications, the compositional operation of the graft in architectural terms takes place through the device of the fragment which, by its etymological definition, is characterized as part of a unitary entity (Ghersi, 2006). The fragment is, therefore, a term that identifies a double meaning that refers both to the single object and to the unitary figure that it generates in the juxtaposition with other fragments of the same or different nature. Configuring itself as a punctual entity, it retains its identity independently of the whole, and it is an integral and necessary part of the whole without compromising the integrity of the pre-existence (Figures 7–9). An emblematic case that describes the use of the device of the fragment is offered by the intervention of David Closes for the convent of San Francisco de Sampedor in Spain. The compromise of the wall enclosure, operated with the grafting of a perfectly recognizable shape (the auditorium), breaks the continuity of the pre-existence and reconfigures, through overwriting, the image of the original building in its main front. In a different way, the fragment is used by Markus Scherer and Walter Dietl as a design element to reconceive the distribution system of the Fortezza di Fortezza in Bolzano. The pre-existing body of the building is, first, brought back to its original condition by removing the recent constructions, emphasizing the materiality of the imposing masonry that characterizes it. Subsequently, the manufacture is grafted with the introduction of some precise elements: two towers in reinforced concrete containing the lift systems and light-metal walkways that reconfigure the image of the front of the fort overlooking the water. In both cases, the overall image of the pre-existence is not affected in its entirety, and the interventions are limited to the introduction of recognizable fragments placed in specific points, declined as autonomous devices in their figurative nature but which interact virtuously with the existing.

FIGURE 7. Didactic work from the Laboratory of Urban Planning held by Prof. L. Romagni, SAAD Unicam, 2020–21. Case study: San Benedetto del Tronto, Ascoli Piceno, Italy. Student: Roberto Crivellari.

FIGURE 8. Didactic work from the Laboratory of Urban Planning held by Prof. L. Romagni, SAAD Unicam, 2020–21. Case study: San Benedetto del Tronto, Ascoli Piceno, Italy. Students: Giorgia Felicioni and Mary Losani.

FIGURE 9. Master thesis project “Riqualificazione del borgo di Bellante (TE). Nuovi percorsi, la porta e le mura storiche,” 2012–13. Student: Stefano Angeloni. Supervisor: Prof. L. Romagni.

8 The joint: The measure of the separation between the old and new

As a consequence of what has been said, it is possible to develop a reflection by bringing the relationship between the ancient and the new in terms of intervals and distances. By interval, we mean the distance that is generated by the juxtaposition between the ancient material of the existing and the new architectural devices clearly recognizable (for technologies and materials) (Cellini, 2016) through the operation of the grafting. The modulation of this distance is the key element which determines the type of dialectical relationship and the spatial quality it produces, and the design device capable of regulating it is the joint, defined as the technical, ideological, and compositional space of separation which determines a first form of relationship with the ancient.

It is a distance that highlights the temporal and historical passage between the epoch of origin and the contemporary, a sort of pause that condenses and fills, through the void, the gap of the past by relating it to the present. The joint is, therefore, configured as a device that facilitates the reading of an architectural work: its observation allows the understanding of the stratification of signs and of the material and temporal difference of which the architecture is made. The entity of this distance can range from the infinitesimal measure, which due to its size, does not have the strength to generate a habitable space (De Vita, 2015), up to very wide intervals capable of producing new and different architectural and urban relationships between the two components. As in the case of the musical remix, the interpretation of the joint as a tool for controlling the relationship between old and new can take place through the definition of possible distances, which, starting from the knowledge of the moments of greatest historical expression of the artifact, are able to define actions with a hierarchy of increasing alteration capable of healing the gaps and the broken (in the order: “extensive remix,” “reflexive remix,” “selective remix,” and “regenerative remix”). Proceeding according to a scalar progression, we can identify different configurations of the joint according to the distance it produces: line, thickness, or slight detachment, habitable space, and urban relationship. If the distance is zero, the joint does not actually exist, and the contact between the old material and the new takes place physically through a line: in this condition, the recognition of the parts is entrusted almost exclusively to the different use of the materials and, possibly, to calibrated shifts that highlight what exists from the new intervention (Figure 10). We can observe how the use of the joint declined as a contact element enhances the difference between the old and new in the attempt to reconstruct the original form that Carlos Quevado adopts in the restoration of the Castle of Matrera in Spain or as in the restoration carried out by 2tr Architetti of the Church of Sant’Antonio in Santa Flora, where the ruins of the complex are enhanced through the arrangement of white cement slabs in contact with the masonry apparatus, in which the joint/line emerges by difference of material granularity. On the other hand, when the distance produced by the juxtaposition between old and new materials is regulated by a greater depth, the joint takes the form of a thickness or a detachment: while continuing to establish physical contact with the existing, it can be used to enhance the autonomy of the grafting elements or to introduce passages of reduced dimensions where to place paths or technical elements. There are numerous examples available: Carlo Scarpa, in his works, was able, more than any other, to reach a profoundly poetic condition in the use of this device. A significant example can be found in the contact between the existing building and the thickness of the large perforated concrete slab that emerges from the facade of the Gavina showroom in Bologna in 1961. Among the most recent works, Nieto Sobejano (one of the Spanish design studios that mostly deals with the aspects of the relationship between old and new), in the restoration project of the Castle of La Luz in Las Palmas, Spain, bring out the historic wall, its materiality, and consistency, through the contrast determined by the contact with the abstract white walls that form the background in the internal spaces. In this case, the joint takes on a further meaning: it becomes the modulation device of the light that penetrates inside through the void produced by the detachment between the elements and the paths. Proceeding in this progression, we can identify a different form of interval that is generated when the distance, expanding further, produces a physical detachment between the old and the new in order to define a usable space. Depending on the size of the interval, the joint functions as a device capable of configuring different spatialities suitable for hosting strategic functions or intermediate areas between the two conditions: paths, exhibition spaces, or areas of introduction to specific sectors (Figures 11, 12). Taking the work of Nieto Sobejano as a reference again, we observe how this condition becomes characteristic in the expansion project of the San Telmo Museum in San Sebastian, where the new volume, built to contain new functions and support the sloping ground behind it, departs from the pre-existing through an interval that configures the distribution path. Similarly, in the expansion project of the Moritzburg Museum in Halle in Germany, the distance between the original masonry and the new metal roof generates a transparent pause that enhances the difference between the parts and allows the light to highlight the fluid articulation of the new internal spaces. The resulting spatialities are characterized by very strong contrasts that configure suggestive spatial conditions which comprise the most representative functions of the building. Increasing the distance, we arrive at the most extreme condition of the use of the joint device, described by the condition in which the interval that is generated between the new and the old assumes relevance on the urban level. The proximity that exists between the project and the pre-existence can go beyond the boundaries of the context in which the existing is located and establishes a dialectical relationship at a distance without losing meaning and continuing to exist in a dialogic relationship. Bernard Tschumi’s project for the New Acropolis Museum in Athens is an emblematic case: the relationship that is generated between the intervention and the illustrious pre-existence of the Parthenon is determined by the reworking of the temple building in a contemporary key. The museum seeks a relationship through a precise correspondence of alignments and positions: in particular, in the reciprocal rotation of the temple on the top of the Acropolis recalled through the angle that forms between the base and the superimposed building of the museum. The transparency of the shell allows visual continuity with the Parthenon and builds a mutual dialogue that develops at a distance. Although the condition of non-proximity prevents physical contact between the ancient and the new, the relationship that is established continues to be very intense and, in any case, certainly tangible. Whether it is a joint, a portion of a building, or a territorial area, the gap produced by the distance between new and old always represents an interstitial condition: regardless of its shape or size, it is, in fact, an intermediate situation, a void between the various elements, which relates objects of a temporal nature and different materials (Cellini, 2016). The definition of this type of void/pause through its capability to put the ancient trace in communication with the present time, whether it is a fragment or an intact artefact, determines the interpretative key and the value of the alteration project of the existing. Crossing or observing the different typologies of this contact space means understanding the architecture and recognizing the parts by difference, in a condition of proximity and reciprocity between new and old that is always evident. The necessary confrontation with the existing requires the ability to formulate design strategies for the relationship between old and new that define architectural devices capable of using the old material as an element to be re-signified also through the exaltation of diversity. Therefore, if the result of the project of manipulation of the existing is identified in the relationship between the ancient material and the new, it is useful to understand the devices and strategies that the architectural project puts in place in order to produce typological alterations, a set of relationships that necessarily confronts the nature of the existing (without necessarily supporting it or vice versa corrupting it) and with its essential characteristic features.

FIGURE 10. Didactic work from the Laboratory of Urban Planning held by Prof. L. Romagni, SAAD Unicam, 2017–18. Case study: Trisugno, Ascoli Piceno, Italy. Students: Ludovica Crispi and Rita Pettinari.

FIGURE 11. Didactic work from the bachelor thesis workshop “Grafting” held by Prof. L. Romagni, SAAD Unicam, 2021. Case study: Sant’Angelo Magno complex, Ascoli Piceno, Italy. Student: Lorenzo Bruni.

FIGURE 12. Didactic work from the Laboratory of Urban Planning held by Prof. L. Romagni, SAAD Unicam, 2017–18. Case study: Trisugno, Ascoli Piceno, Italy. Students: Ludovica Crispi and Rita Pettinari.

9 Alterations: Observation on the conflict between old and new

The question of the pre-existing project and the sometimes antagonistic position established between designers of the new and restorers is entering a phase of redefinition. If the discipline of restoration had to deal with the project of recovery of pre-existing historical buildings with the aim of safeguarding their objectivity, the confused extension of the concept of historicity to a large part of the building is making it irreplaceable for any project of urban and architectural transformation. This is mortifying for the architectural project and its poetic roots, which are systematically set aside in favor of the application of a scientific method based on the exaltation of the various fields of knowledge: history, the state of conservation of the elements, and the application of technical devices of recovery. But what is a historic building today? Italian law defines a building between 50 and 70 years old as historic, regardless of its formal aesthetic qualities. To intervene in an architectural structure with these temporal characteristics, there is a need for particular procedures, safeguards, and specific clearances aimed at guaranteeing its conservation. However, in a city that is now completely built, everything is more than 50 years old: historic architecture, the Modern and Late Modern buildings, and even those that we could define as contemporary coexist in a condition of potential crystallization. Consequently, all projects for the transformation of the architectural and urban heritage of our cities and our landscape should fall within the specific competence of restorers and structural engineering. The “Cronocaos” exhibition created by OMA/Rem Koolhaas, presented for the first time on the occasion of the 2010 Venice Biennale (expanded and replicated at the New Museum in New York in 2011), starts from the reflection that 12% of the world’s heritage falls under different regimes of conservation and protection (natural or cultural), raising the need for a reflection to “find a shape for the future of our memory.” According to Koolhaas, the goal is not to propose a better theory of conservation but to return to reflecting on the existing, on the integration of the past with the present, on the need for a renovation of rules and cultural background regarding the theme of “preservation.”. In the contemporary world, the increase in the feeling of nostalgia is corresponding to a dangerous reduction of memory: currently, in fact, the nostalgic ostentation of respect for the past is at its maximum, but the awareness that its conservation has been a sign of radical transformation from the very beginning is minimal. Although the theme is not new, going back to talking about the past and conservation in this historical moment (in which the intersection between the tendencies of destruction and preservation are compromising any possible perception of the linear evolution of the city over time) becomes more appropriate than ever. We do not want to question the of the transformative project through the in-depth investigation of all areas of knowledge. Just as it remains evident that in contexts of extraordinary historical value, in which the integrity of the whole configures a linguistic unity that might not allow the expression of a contemporary contrasting language with ease, it will be necessary to intervene with the right measure of the cultural, dimensional and linguistic. We do not want to theorize the compromise of the supreme identities of untouchable cities such as Venice or Florence, despite the controversy over the outcome of the competition for the new exit of the Uffizi Gallery representing a sign of widespread concern, but to reformulate intervention categories with increasing degree of transformability according to the real identity value of the original asset to any historical period it belongs to: a theme that captures the attention of the most important traditional architecture magazines. Casabella, for example, or the digital platforms of architectural images have been busy for some time, publishing mostly foreign projects of quality reuse, restoration, and renovation projects, which would not even be possible in Italy due to the impending corpus of regulations and constraints. “Archaeology and restoration,” “ruins and conservation,” “new meanings for past places,” and “buildings from buildings” are titles both intriguing and demoralizing, confirming the fact that today, we need to look at what is happening in various European contexts to understand how to implement the project on the existing and reluctantly thinking back to the golden age of the great masters, Scarpa among others, when Italy was the destination of pilgrimages from everywhere (Archilovers, 2012). Over the years, the practice of crystallizing conservation has drastically expanded from ancient monuments to entire landscapes, so, today, everything we inhabit is potentially safeguardable. General criteria that are unclear and too vague make “freezing the old and blocking the new” the most reassuring option. Gio Ponti, in 1957, recognized a single possible idea of tradition: «transforming things; time is measured only by the transformation of things: where there is no time, there is no history» (Ponti, 1957).

Italy has, therefore, not always been immobile: « Save to destroy, destroy to save yourself; in times of apocalypse the extremes meet, the opposites are equal. The only rescue is once again the destruction, the total sterilization of that organism which, born to be the home of man, has become his prison and finally a sepulcher» (Archilovers, 2012). On the contrary, the hot extremism of Superstudio led to the photomontages of the series “Salvation of the Italian historic centers” of 1972, which illustrate their controversial position with regard to the policy of safeguarding historic centers and the landscape, and in particular, of the major historic Italian cities and their monuments. However, then, what are the possible spaces to focus on a new and virtuous relationship between the existing and the project? Where to find this new space? The city, the territory as a whole, so densely built and overwritten by fragments of historicity, modernity, and contemporaneity, offers itself as a place for necessary experimentation. Then, especially in Italy, urban centers not only can but must become the palimpsests where to prolong that ceaseless work that history has always operated on its buildings: annexing, intersecting, superimposing, and cutting out volumes, stratifications, and, therefore, narratives, in the previous plot. A method of intervention on the existing should be promoted, declaring the time of the project, by referring to an ideal of sincerity toward the flow of history, without the fear of inserting highly contemporary objects in the pre-existence, which becomes the scene of new spatial and conceptual tensions. In the research we are carrying out in the School of Architecture and Design of Ascoli Piceno, University of Camerino, through didactic experiments, publications, and opportunities for discussion with organizations and institutions, we have tried to explore an abacus of elements and strategies, capable of directing the construction of a project that redefines a virtuous relationship between old and new. Opportunities are offered by the reinterpretation of some formal elements to which to attribute new meanings and values to make the elements of innovation recognizable, enhancing the virtuous separation with the pre-existence. From the opportunities offered by the contact element, the joint (in its different shapes and dimensions, line, thickness, and distance), we have moved on to analyze some compositional strategies applicable to the archetypal condition of the existing: the enclosure and the frame. On these elements, actions, such as grafting, subtracting, or less usual operations difficult to ascribe to precise categories, offer themselves as a tool for investigating the relationship between the shell and structure, between inside and outside, between old and new. Yet, the skillful incursion of the “fragment” to configure new non-mimetic overwritings, as a means to search for typological alterations, are not necessarily compatible. The logic of alteration, recognized as a possible way for the re-functionalization of the existing architecture, acts on these relationships by modifying (or even subverting) them in order to establish new relationships more suited to the needs of a city in constant transformation. This fact poses the question of how the measure of the new, and therefore, the entity that the intervention on the existing must respect and assume in order not to compromise the identity of the asset. This area of research aims for the rapprochement between the two disciplinary areas of architectural design and restoration, where the poetic root of the project dialogues with the cognitive action on the asset and the application of scientific criteria for consolidating and restoring the elements. It is, therefore, worth remembering Bruce Mau and the 23rd point of his “Incomplete Manifesto for Growth”: «step on someone’s shoulders. If you get carried away by the results of those who preceded you, you can go further. and the panorama is much better» Monisteri, 2018.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

LR conceived the presentation idea and supervised the findings of this work. He investigated the chapter “1 Introduction,” chapter “2 The worksite city,” chapter “3 Interaction methods and devices,” chapter “4 A multidisciplinary point of view,” chapter “5 Cognitive phase vs. creative phase,” and chapter “9 Alterations: Observation on the conflict between old and new.” SP investigated the chapter “6 The archetypes: The zero degree of the existing,” chapter “7 The Fragment: Graft on the existing,” and chapter “8 The Joint: The measure of separation between old and new.” All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ance (2016). Osservatorio congiunturale sull’industria delle costruzioni. in XXIV Rapporto Congiunturale Previsionale del Cresme 2016. Available at: http//www.ance.it/docs/docDownload.aspxçid=28869.

Archilovers (2012). Archilovers. Available at: https://www.archilovers.com/stories/1340/cronocaos-e-il-futuro-del-passato.html (Accessed January 11, 2023).

Baglione, C., and Pedretti, B. (1991). “Intervista a Manfredo Tafuri. Storia, conservazione, restauro,” in Casabella n.580, 23–26.

Bocchi, R. (2013). “Dal riuso al riciclo,” in Strategie architettonico urbane per le città in tempo di crisi. Editors S. Marini, and V. Santangelo (Roma: Aracne), 185–190. Viaggio in Italia.

Cao, U. (2016). “Scheletri rianimati,” in Re-Cycle Italy n.21 Scheletri riciclo di strutture incompiute. Editors U. Cao, and L. Romagni (Ariccia: Aracne editrice), 80. «The cities and the Italian and Mediterranean landscape are today invaded by building wrecks, above all industrial warehouses but also office buildings or residences. They are architectural skeletons, constructions in which the interruption of the construction process has determined an unfinished condition characterized by the dominant presence of the structural frame.».