- 1 IRIS Group, UMR 8194, CNRS, Service d’Ophtalmologie-ORL-Stomatologie, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris, France

- 2 University of Paris V, Paris, France

Piercings (body art, i.e., with jewelry) are more and more widespread. They can induce various complications such as infections, allergies, headaches, and various skin, cartilage, or dental problems, and represent a public health problem. We draw attention to possible side effects resulting from face piercing complications observed on four young adults such as eye misalignment, decreased postural control efficiency, and non-specific chronic back pain with associated comorbidity. We found that the origin was pierced jewelry on the face. Removing the jewelry restored eye alignment, improved postural control, and alleviated back pain in a lasting way. We suggest that pierced facial jewelry can disturb somaesthetic signals driven by the trigeminal nerve, and thus interfere with central integration processes, notably in the cerebellum and the vestibular nucleus involved in postural control and eye alignment. Facial piercings could induce sensory–motor conflict, exacerbate, or precipitate a pre-existing undetermined conflict, which leads pain and complaints. These findings are significant for health; further investigations would be of interest.

Introduction

Piercings (body art) are more and more widespread, and can induce various complications such as infections, allergies, headaches, various skin, cartilage, or dental problems which will lead to economic effects on health-care systems (e.g., Mayers et al., 2002; Stirn, 2003; Bone et al., 2008).

To maintain the center of body mass in equilibrium while standing, the central nervous system performs coordinated transformations of visual, vestibular and somaesthetic inputs (see lvanenko et al., 1999), and permanently generates muscular response adapted as corrective torque through the action of a feedback control system (Peterka, 2002; Todorov, 2004).

Vertical heterophoria (VH) and vertical orthophoria are respectively the presence or the absence of a relative deviation of the vertical visual axes when the retinal images are dissociated, i.e., each eye views a different image (see Amos and Rutstein, 1987). VH can be induced by eye refraction problems (Amos and Rutstein, 1987), but without refraction problems, VH of small size (<1 dpt, i.e., 0.57°) could exist indicating a perturbation of the somatosensory loops involved in postural control (Matheron and Kapoula, 2008, 2011). In subjects with VH in this normal range, postural stability was impaired relative to subjects with vertical orthophoria; the cancelation of the VH with an appropriate vertical prism improved postural stability (Matheron and Kapoula, 2008, 2011). The influence of VH was explained by among other possibilities: the colliculus superior, the brainstem nuclei, and the cerebellum receiving visual, extraocular muscles and somatosensory inputs, implied to the vestibuloocular, the vestibulospinal and the reticulospinal systems required in phoria adjustment, vertical binocular alignment, and postural control while standing (see Büttner-Ennever, 2006; Matheron and Kapoula, 2008).

We hypothesized that pierced facial jewelry disturbed somaesthetic signals driven by the trigeminal nerve, and might be related to interference in central integration processes leading to various complaints. Here, we draw attention to the possible side effects resulting from facial piercing (with jewelry) complications such as eye misalignment, decreased postural stability, and non-specific chronic back pain.

Materials and Methods

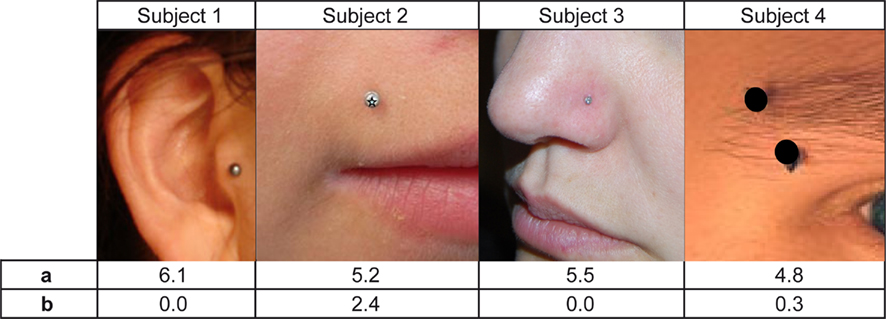

Four subjects wearing facial jewelry pierced in eyebrow, tragus, upper lip, and nose (Figure 1) retained our attention; they suffered from non-specific chronic back pain with an additional comorbidity such as dizziness, headache, or eyestrain known in non-specific chronic back pain (Von Korff et al., 2003; Hagen et al., 2006), associated with a VH (Matheron and Kapoula, 2011). They did not wear glasses, so there were no prismatic effects and thus no induced vertical eye deviation. Vision was normal with no history of strabismus, double vision, nor any other manifest ocular disease. Medical consultation and complementary examination (e.g., radiographic imaging, magnetic resonance imaging, or blood analysis) did not report any findings (anatomical, neuropathy, or rheumatism).

Figure 1. Pierced jewelry on the face of each subject. Pain score evaluated with a subjective analogical scale on the first day before the jewelry was removed (A), and when each subject was checked on average 3 weeks later without the jewelry (B).

Pain was evaluated using a subjective visual analogical scale of 10 cm (0–10, “0” as no pain and “10” as the extreme of pain; Huskisson, 1974) validated for chronic pain (Price et al., 1983). See Figure 1.

Vertical heterophoria was detected, and measured for all the subjects as less than 0.57° with the Maddox Rod Test, combined with an appropriate prism value, which is one of the most appropriate tests (Wong et al., 2002).

Postural performance during quiet standing was investigated through the center of pressure (CoP) displacements recorded using a force platform (principle of strain gage) consisting of two dynamometric clogs (TechnoConcept, Céreste, France). The excursions of the CoP were measured over a period of 25.6 s while the subjects looked at a target, a letter “x” (angular size = 1°), 200 cm away at eye level; the equipment contained an Analog–Digital converter of 16 bits and the sampling frequency of the CoP was 40 Hz. The subjects wore a special spectacle into which one could easily insert or not a vertical prism, and were placed barefoot on the force platform. They stood in a quiet upright and standardized position (feet placed side by side, forming a 30° angle with heels separated 4 cm). They were asked to look at the “x” target in the straight ahead position.

The conditions were: (1) with jewelry: eyes open, eyes open with a prism to cancel the VH, and eyes closed; (2) jewelry removed: eyes open and eyes closed. A check was done on average 3 weeks later, the conditions were eyes open and eyes closed. Each testing condition over the period of 25.6 s was done twice and was counterbalanced, and data averaged.

The investigation adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional human experimentation committee, the “Comité de Protection des Personnes” Ile de France, in Paris. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after the nature of the procedure had been explained.

Results

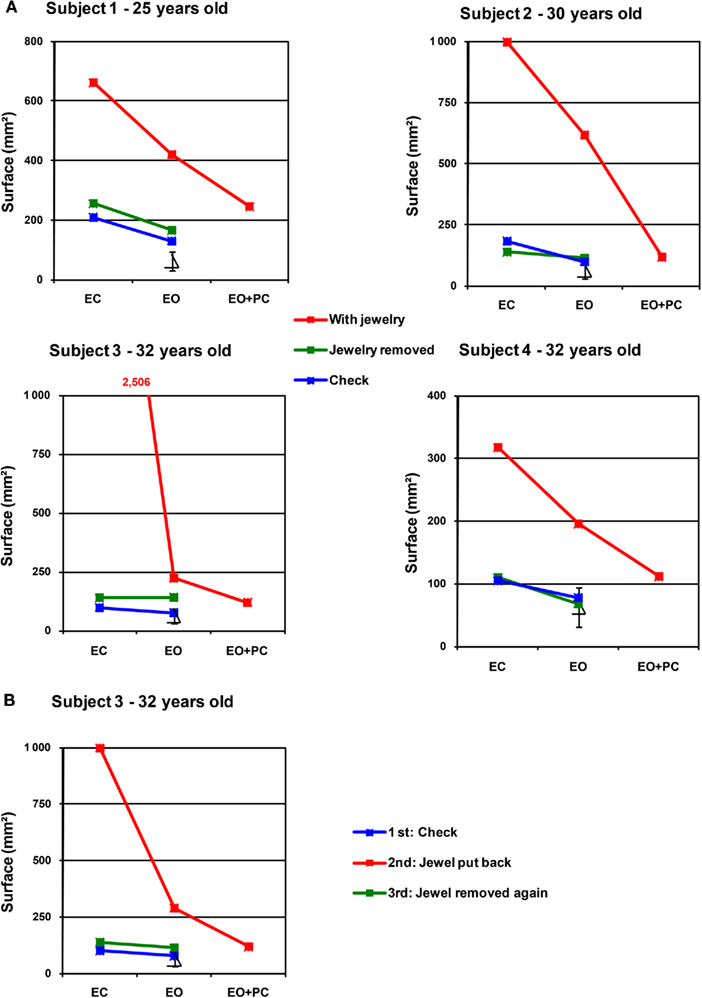

Here, we presented the body sway area (mm2), the parameter known for reporting on postural stability (e.g., Tagaki et al., 1985; Vuillerme et al., 2008). See Figure 2. For all cases, postural stability (Figure 2A) was strongly lower when eyes were closed, indicating a strong visual dependency for body stabilization. Yet the values with eyes open were still higher than corresponding values of healthy subjects with eyes open. When an appropriate prism canceled the VH, postural stability increased further approaching normal values (Matheron and Kapoula, 2008). More surprising, removal of jewelry immediately improved postural stability and restored eye alignment. The difference between eyes open and eyes closed conditions became smaller. Subjects were advised to remove the jewelry permanently. Three weeks later, back pain had either diminished or ceased entirely (Figure 1). Postural stability tended toward normal. Interestingly, one subject then agreed to put the jewelry back in temporarily (Figure 2B). Five minutes later, VH was found, postural stability decreased. When the jewelry was removed again, postural stability improved.

Figure 2. (A) Reporting on postural stability, means of the surface area of the center of pressure excursions (mm2) for each subject for each condition with jewelry, when jewelry is removed and when on average 3 weeks later the check is done. Eyes open (EO), eyes closed (EC), and EO with a prism to cancel the vertical heterophoria (EO + PC). Triangle symbols indicate EO control data from the study of Matheron and Kapoula (2008) of healthy subjects with vertical orthophoria, and with no jewelry or back pain. (B) Results for Subject 3 who agreed to put the jewelry back on temporarily during the second session.

Discussion

The results of four cases are of course not sufficient to generalize, but suggest that piercings could thus create more complications than those currently described in literature; we found binocular misalignment, reduced postural control efficiency, and non-specific chronic back pain. To our knowledge, aside from our conference abstract (Matheron and Kapoula, 2009), and that of Zanchetta et al. (2009) reporting on the influence of lingual piercing on postural control, the lack of studies on such from piercings in literature is surprising. Indeed, jewelry in body piercings is widespread, psychological, sociological, or culturally dependent, for instance nasal piercing is very frequent in India (for review, see Stirn, 2003). Maybe because body pierced jewelry is so common and the link to numerous side effects (beyond immediate pain, local infection, or other skin modifications as necrosis) has not yet sufficiently been established, its detrimental role remains underestimated.

For face pierced jewelry, it is important to emphasize that trigeminal primary afferent neurons and their sensory receptors provide information for the perception of the orofacial region, and contribute to various types of sensorimotor integration (Capra and Dessem, 1992; Shankland, 2000) such as postural control while quiet standing (Gangloff et al., 2000; Gangloff and Perrin, 2002). These afferences project to the cerebellum, the reticular formation, and the vestibular nucleus (see Capra and Dessem, 1992) which are located at the base of the spinal motor neurons and oculomotor efferents (see Büttner-Ennever, 2006). Previous studies reported that VH could indicate a conflict between somaesthetic signals, here produced by jewelry in the trigeminal territory, involved in sensorimotor loops required in postural control (Matheron and Kapoula, 2008, 2011). Persistent conflict between vision and somaesthetic cues could lead to non-specific chronic back pain (McCabe et al., 2005; Matheron and Kapoula, 2011), modify perception, or even induce pain and unpleasant sensations in healthy subjects (McCabe et al., 2005, 2007). This novel observation can be understood in this context. The next step is to investigate the influence of piercings on the face, and other body parts in a larger number of cases. For instance, experimental studies of postural control in quiet stance are needed before and after body pierced jewelry. Postural control is also the basis for body stability during movements and gait (Gurfinkel et al., 1995). Furthermore, postural control is involved in the control of body segment orientation and body stabilization, which is a prerequisite for perception and action (Amblard et al., 1985). Investigations on movement performance, eye–hand or eye–foot coordination would be of interest, as well as studies with eye movement recordings and visual stereoscopic tests, because small VH can alter vergence eye movements, stereopsis depth perception, and distance evaluation (see Saladin, 1995, 2005). We hope that this preliminary study will stimulate research in these fields.

As mentioned, recent studies (Stirn, 2003; Laumann and Derick, 2006) have reported that body piercing as body art, i.e., with jewelry, has a high incidence of medical complications. Here we report central complications possibly related to induced sensory–motor conflicts. As previously proposed, prolonged sensory–motor conflict could exacerbate pain and other symptoms, or could act after an undetermined precipitating event on a pre-existing conflict, or as a precipitating event in the trigeminal territory (Matheron and Kapoula, 2011). Health professionals and researchers should be aware of the possible side effects of piercings, i.e., impaired motor control, body pain, and additional comorbidity – known in chronic back pain (Von Korff et al., 2003; Hagen et al., 2006) including postural disorders (Gagey et al., 1980; Da Cunha, 1987), and the presence of VH (Amos and Rutstein, 1987; Scheiman and Wick, 1994), and heterophoria. Epidemiological and longitudinal studies of such side effects would be of interest.

Conclusion

Body piercings with jewelry, at least on the face, could more or less rapidly induce other complaints than the medical complications described in the relevant literature; we report here body pain, impaired postural control, and vertical eye misalignment (heterophoria). If these side effects were confirmed in a larger population, health professionals need to deal with them taking into account sociological and psychological aspects as recommended by Stirn (2003). We hope this study of a few cases could stimulate further experimental and clinical research to complete the investigation on risk factors linked to body piercing, and lead to public health recommendations and prevention. More knowledgeable clinicians could thus better inform patients thus helping to reduce possible future complaints.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mildred Aknin and Suzanna Pacaut for English revision, and thank the reviewers for their stimulating and constructive comments.

References

Amblard, B., Crémieux, J., Marchand, A. R., and Carblanc, A. (1985). Lateral orientation and stabilization of human stance: static versus dynamic visual cues. Exp. Brain Res. 61, 21–37.

Amos, F. J., and Rutstein, R. P. (1987). “Vertical deviation,” in Diagnosis and Management in Vision Care, ed. F. J. Amos (Amsterdam, NY: Butterworths), 515–583.

Bone, A., Ncube, F., Nichols, T., and Noah, N. D. (2008). Body piercing in England: a survey of piercing at sites other than earlobe. BMJ 336, 1426–1428.

Capra, N. F., and Dessem, D. (1992). Central connections of trigeminal primary afferent neurons: topographical and functional considerations. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 4, 1–52.

Gagey, P. M., Baron, J. B., and Ushio, N. (1980). Introduction to clinical posturology. Agressologie 21, 119–123.

Gangloff, P., Louis, J. P., and Perrin, P. P. (2000). Dental occlusion modifies gaze and posture stabilization in human subjects. Neurosci. Lett. 293, 203–206.

Gangloff, P., and Perrin, P. P. (2002). Unilateral trigeminal anaesthesia modifies postural control in human subjects. Neurosci. Lett. 330, 179–182.

Gurfinkel, V. S., Ivanenko, Y. P., Levik, Y. S., and Babakova, I. A. (1995). Kinesthetic reference for human orthograde posture. Neuroscience 68, 229–243.

Hagen, E. M., Svensen, E., Eriksen, H. R., Ihlebaek, C. M., and Ursin, H. (2006). Comorbid subjective health complaints in low back pain. Spine 31, 1491–1495.

Laumann, A. E., and Derick, A. J. (2006). Tattoos and body piercings in the United States: a national data set. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 55, 413–421.

lvanenko, Y. P., Grasso, R., and Lacquaniti, F. (1999). Effect of gaze on postural responses to neck proprioceptive and vestibular stimulation in humans. J. Physiol. 519, 301–314.

Matheron, E., and Kapoula, Z. (2008). Vertical phoria and postural control in upright stance in healthy young subjects. Clin. Neurophysiol. 119, 2314–2320.

Matheron, E., and Kapoula, Z. (2009). Piercings, phories verticales et stabilité posturale: rapport de cas. Neurophysiol. Clin. 39, 254–255.

Matheron, E., and Kapoula, Z. (2011). Vertical heterophoria and postural control in nonspecific chronic low back pain. PLoS ONE 6, e18110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018110

Mayers, L. B., Judelson, D. A., Moriarty, B. W., and Rundell, K. W. (2002). Prevalence of body art (body piercing and tattooing) in university undergraduates and incidence of medical complications. Mayo Clin. Proc. 77, 29–34.

McCabe, C. S., Cohen, H., and Blake, D. R. (2007). Somaesthetic disturbances in fibromyalgia are exaggerated by sensory motor conflict: implications for chronicity of the disease? Rheumatology 46, 1587–1592.

McCabe, C. S., Haigh, R. C., Halligan, P. W., and Blake, D. R. (2005). Simulating sensory–motor incongruence in healthy volunteers: implications for a cortical model of pain. Rheumatology 44, 509–516.

Peterka, R. J. (2002). Sensorimotor integration in human postural control. J. Neurophysiol. 88, 1097–1118.

Price, D. D., McGrath, P. A., Rafii, A., and Buckingham, B. (1983). The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 17, 45–56.

Scheiman, M., and Wick, B. (1994). Clinical Management of Binocular Vision, Heterophoric, Accommodative and Eye Movement Disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 405–440.

Stirn, A. (2003). Body piercing: medical consequences and psychological motivations. Lancet 361, 1205–1215.

Tagaki, A., Fujimura, E., and Suehiro, S. (1985). “A new method of statokinesigram area measurement. Application of a statistically calculated ellipse,” in Vestibular and Visual Control on Posture and Locomotor Equilibrium, eds M. Igarashi and O. Black (Bâle: Karger), 74–79.

Von Korff, M., Crane, P., Lane, M., Miglioretti, D. L., Simon, G., Saunders, K., Stang, P., Brandenburg, N., and Kessler, R. (2003). Chronic spinal pain and physical-mental comorbidity in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Pain 113, 331–339.

Vuillerme, N., Bertrand, R., and Pinsault, N. (2008). Postural effects of the scaled display of visual foot center of pressure feedback under different somatosensory conditions at the foot and the ankle. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 89, 2034–2036.

Keywords: piercing, back pain, trigeminal path, vertical heterophoria, postural instability

Citation: Matheron E and Kapoula Z (2011) Face piercing (body art): choosing pleasure vs. possible pain and posture instability. Front. Physio. 2:64. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00064

Received: 14 June 2011; Paper pending published: 15 July 2011;

Accepted: 02 September 2011; Published online: 21 September 2011.

Edited by:

Mikko Paavo Tulppo, Verve, FinlandReviewed by:

Rita Stagni, University of Bologna, ItalyVirve Koljonen, Helsinki University Hospital, Finland

Copyright: © 2011 Matheron and Kapoula. This is an open-access article subject to a non-exclusive license between the authors and Frontiers Media SA, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and other Frontiers conditions are complied with.

*Correspondence: Eric Matheron, IRIS Group, UMR 8194, CNRS, Service d’Ophtalmologie-ORL-Stomatologie, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, 20 rue Leblanc, 75908 Paris Cedex 15, France. e-mail:bWF0aGVyb25Ad2FuYWRvby5mcg==