Abstract

Numerous national associations and multiple reviews have documented the safety and efficacy of strength training for children and adolescents. The literature highlights the significant training-induced increases in strength associated with youth strength training. However, the effectiveness of youth strength training programs to improve power measures is not as clear. This discrepancy may be related to training and testing specificity. Most prior youth strength training programs emphasized lower intensity resistance with relatively slow movements. Since power activities typically involve higher intensity, explosive-like contractions with higher angular velocities (e.g., plyometrics), there is a conflict between the training medium and testing measures. This meta-analysis compared strength (e.g., training with resistance or body mass) and power training programs (e.g., plyometric training) on proxies of muscle strength, power, and speed. A systematic literature search using a Boolean Search Strategy was conducted in the electronic databases PubMed, SPORT Discus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar and revealed 652 hits. After perusal of title, abstract, and full text, 107 studies were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The meta-analysis showed small to moderate magnitude changes for training specificity with jump measures. In other words, power training was more effective than strength training for improving youth jump height. For sprint measures, strength training was more effective than power training with youth. Furthermore, strength training exhibited consistently large magnitude changes to lower body strength measures, which contrasted with the generally trivial, small and moderate magnitude training improvements of power training upon lower body strength, sprint and jump measures, respectively. Maturity related inadequacies in eccentric strength and balance might influence the lack of training specificity with the unilateral landings and propulsions associated with sprinting. Based on this meta-analysis, strength training should be incorporated prior to power training in order to establish an adequate foundation of strength for power training activities.

Introduction

In contrast to the prior myths of health concerns regarding resistance training (RT) for children (Rians et al., 1987; Blimkie, 1992, 1993; Faigenbaum and Kang, 2005), the contemporary research emphasizes the beneficial effect of youth RT for health, strength, and athletic performance (Sale, 1989; Webb, 1990; Faigenbaum et al., 1996, 2009; Falk and Tenenbaum, 1996; Payne et al., 1997; Golan et al., 1998; Hass et al., 2001; McNeely and Armstrong, 2002; Falk and Eliakim, 2003; American College of Sports Medicine, 2006; Faigenbaum, 2006; Malina, 2006; Behm et al., 2008; Granacher et al., 2016). With a properly implemented youth RT program, muscular strength and endurance can increase significantly beyond normal growth and maturation (Pfeiffer and Francis, 1986; Weltman et al., 1986; Sailors and Berg, 1987; Blimkie, 1989; Ramsay et al., 1990; Faigenbaum et al., 1996, 1999, 2001, 2002). Falk and Tenenbaum (1996) conducted a meta-analysis and reported RT-induced strength increases of 13–30% in pre-adolescent children following RT programs of 8–20 weeks. The Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP) position stand (Behm et al., 2008) indicated that the literature provided a clear positive effect for improving muscle strength. In contrast, there were far fewer RT studies that measured power capacities, which only provided small effects for adolescents and unclear effects of RT on improving power for children (Weltman et al., 1986; Faigenbaum et al., 1993, 2002, 2007b, 1996; Lillegard et al., 1997; Christou et al., 2006; Granacher et al., 2016).

The small or unclear effects of traditional strength/RT on measures of power in children in the Behm et al. (2008) review could be attributed to the few studies published up to that year that monitored proxies of power. The recent Granacher et al. (2016) review cited only three studies with girls as participants compared to 27 studies with boys but still reported small to barely moderate effects of RT on muscular power. Other factors contributing to smaller effects of traditional strength/RT on measures of power in children could be the lack of training mode specificity (Sale and MacDougall, 1981; Behm and Sale, 1993; Behm, 1995) or perhaps maturation-related physiological limitations upon power training adaptations in children. The typical strength RT protocol for children involves training 2–3 times per week (Malina, 2006), with moderate loads (e.g., 50–60% of 1RM) and higher repetitions (e.g., 15–20 reps) (Faigenbaum et al., 1996, 2009; Lillegard et al., 1997; Christou et al., 2006; Faigenbaum, 2006; Benson et al., 2007; Behm et al., 2008). According to the concept of training specificity, an effective transfer of training adaptations occurs when the training matches the task (e.g., testing, competition) (Sale and MacDougall, 1981; Behm and Sale, 1993; Behm, 1995). Since high power outputs involve explosive contractions with forces exerted at higher velocities, RT programs using low to moderate loads at slower velocities would not match power characteristics. However, recently there are a number of publications that have implemented power training programs (e.g., plyometric training) for children that would adhere to the training specificity principle. Plyometric exercises involve jumping, hopping, and bounding exercises and throws that are performed quickly and explosively (Behm, 1993; Behm et al., 2008; Cappa and Behm, 2011, 2013). With plyometric training adaptations, the neuromuscular system is conditioned to react more rapidly to the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC). Plyometric training can be safe and may improve a child's ability to increase movement speed and power production provided that appropriate training and guidelines are followed (Brown et al., 1986; Diallo et al., 2001; Matavulj et al., 2001; Lephart et al., 2005; Marginson et al., 2005; Kotzamanidis, 2006; Behm et al., 2008). Johnson et al. (2011) published a meta-analysis that only included seven studies that they judged to be of low quality. They suggested that plyometric training had a large positive effect on running, jumping, kicking distance, balance, and agility with children. Hence, further analysis is needed with a greater number of power training studies involving children and/or adolescents.

While many power activities involve shorter duration, higher intensity, explosive type contractions (anaerobic emphasis), children are reported to possess reduced anaerobic capacities (Behm et al., 2008; Murphy et al., 2014) with a lower reliance on glycolysis (Ratel et al., 2006, 2015), and lower power outputs (Falk and Dotan, 2006) compared to adults. In the recently published scoping review (Granacher et al., 2016), Granacher and colleagues were able to show small effect sizes following RT on measures of power in child athletes and moderate effect sizes in adolescent athletes. However, these authors looked at general RT effects only and did not differentiate between strength and power training programs. Moreover, only studies conducted with youth athletes were analyzed.

Thus, it was the objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate whether there are different effects following strength vs. power training on measures of muscle strength, power, and speed in trained and untrained children and adolescents. It is hypothesized that in accordance with the concept of training specificity, power training programs will provide more substantial improvements in power and speed measures than traditional strength programs with youth. Furthermore, since trained individuals would have a greater foundation of strength, we expected greater power training related effects in trained compared to untrained youth.

Methods

Search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria

This review included randomized controlled trials and controlled trials that implemented either traditional strength/resistance training or power training in youth. A literature search was performed by four co-authors separately and independently using PubMed, SPORT Discus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases. The topic was systematically searched using a Boolean search strategy with the operators AND, OR, NOT and a combination of the following keywords: (“strength training” OR “resistance training” OR “weight training” OR “power training” OR “plyometric training” OR “complex training” OR “compound training” OR “weight-bearing exercise”) AND (child OR children OR adolescent OR adolescents OR youth OR puberty OR prepuberal* OR kids OR kid OR teen* OR girl* OR boy OR boys) NOT (patient OR patients OR adults OR adult OR man OR men OR woman OR women). All references from the selected articles were also crosschecked manually by the authors to identify relevant studies that might have been missed in the systematic search and to eliminate duplicates.

Inclusion criteria (study selection)

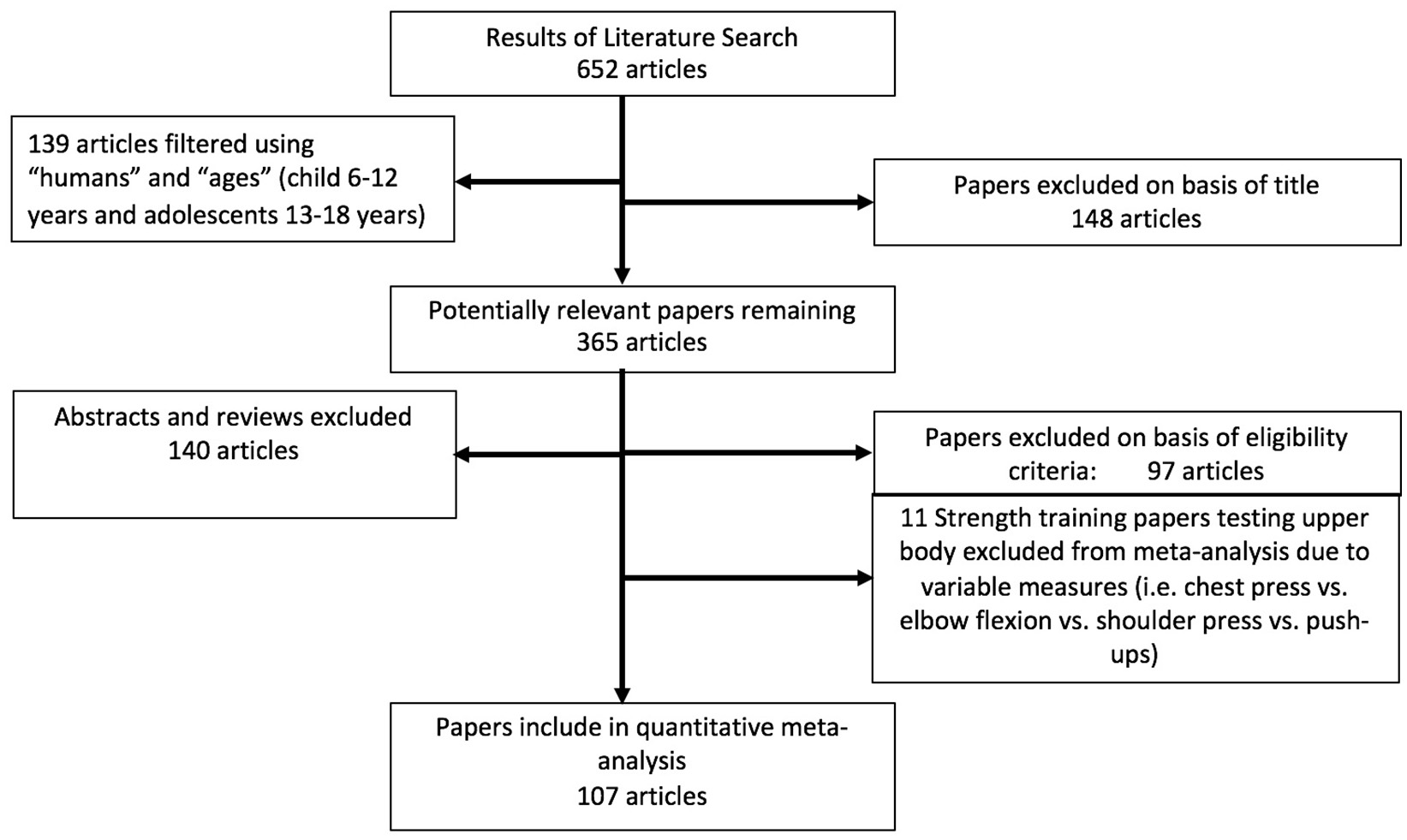

Studies investigating traditional strength/resistance training or power training in youth were included in the review if they fulfilled the following selection criteria: the study (1) was a randomized controlled trial or a controlled trial; (2) measured pre- and post-training strength [e.g., maximal loads (i.e., 1 repetition maximum: 1RM) or forces with squats, leg extension or flexion, isokinetic maximal measures], power-related [e.g., countermovement jump (CMJ), horizontal or standing long jump (SLJ)] or speed-related (e.g., 10-m sprint time) dependent variables; (3) training duration was greater than 4 weeks; (4) used healthy, untrained (i.e., physical education classes and/or no specific sport) or trained (i.e., youth athletes from different sports) youth participants under the age of 18 years; (5) was written in English and published prior to January 2017; and (6) was published in a peer-reviewed journal (abstracts and unpublished studies were excluded). Studies were excluded if precise means and standard deviations, or effect sizes were not available or if the training study combined both strength and power exercises. Our initial search resulted in 652 applicable studies (see flow chart: Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow chart illustrating the different phases of the search and study selection.

Statistical analyses

For statistical analyses, within-subject standardized mean differences of the each intervention group were calculated [SMD = (mean post-value intervention group—mean pre-value intervention group)/pooled standard deviation]. Subsequently, SMDs were adjusted for the respective sample size by using the term (1-(3/(4N-9))) (Hedges, 1985). Meta-analytic comparisons were computed using Review Manager software V.5.3.4 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008). Included studies were weighted according to the magnitude of the respective standard error using a random-effects model. A random effect model was used because the relative weight assigned to each of the studies has less impact on computed combined effect size. In other words, in the fixed effect model, one or two studies with relatively high weight can shift the combined effect size and associated confidence intervals in one particular direction, whereas in a random effect model this issue is moderated.

Further, we used Review Manager for subgroup analyses: computing a weight for each subgroup (e.g., trained vs. untrained), aggregating SMD values of specific subgroups, and comparing subgroup effect sizes with respect to differences in intervention effects across subgroups. To improve readability, we reported positive SMDs if superiority of post values compared with pre-values was found. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 and χ2 statistics. SMDs were calculated to evaluate the magnitude of the difference between traditional resistance and plyometric training according to the criterion of 0.80 large; 0.50 medium and 0.20 small (Cohen, 1988).

Results

Training program prescriptions

The descriptive statistics for the strength and power training program prescriptions are illustrated in Table 1. There were 28.5% more strength training studies within the literature review likely due to the fact that power training experiments for children began more recently (power: 1999 vs. strength: 1986 with one pediatric strength study published in 1958). Strength training studies on average had younger participants (~12 vs. 13 years), 45.2% longer duration training programs (~8 vs. 12 weeks) and implemented approximately 1 less exercise per training session. There were substantially more untrained or physical education student participants in the strength studies (i.e., strength studies with physical education and untrained: 31 vs. power studies with physical education and untrained: 6 with soccer athletes used most often (strength: 9 studies and power: 20 studies). Details of all studies in the review are depicted in Tables 2A,B.

Table 1

| No. of Studies | No. of studies with all male subjects | No. of studies with all female subjects | No. of studies with male and female subjects | Age (years) | Training frequency (sessions per week) | Training Weeks | Sets | No. of Exerc. | Reps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strength 63 (1958, and 1986–2016) | 32 | 1 | 30 | 12.37 ± 0.73 | 2.2 ± 0.52 | 12.45 ± 14.04 | 2.76 ± 1.16 | 6.15 ± 2.94 | 9.83 ± 4.08 |

| Power 52 (1999–2016) | 38 | 11 | 3 | 13.5 ± 0.86 | 2.27 ± 0.58 | 8.57 ± 4.34 | 2.15 ± 1.81 | 7.69 ± 4.94 | 9.94 ± 7.91 |

Training participants and program characteristics.

reps, repetitions; Exerc, exercises. Values provided in first four columns are sums, whereas the last six columns are means and standard deviations.

Number of studies: Strength participants: Physical Education: 15 studies, Untrained: 16 studies.

Sports: Soccer: 9 studies, Rugby: 4, Gymnasts: 2, Basketball, 2, Baseball: 2, Football: 2, Swimming, Handball, American Rowing, Judo, Wrestling, and assorted other sports or trained states.

Power participants: Physical Education: 3 studies, Untrained: 3 studies.

Sports: Soccer: 20 studies, Rugby: 4, Gymnasts: 2, Basketball, 6, Swimming: 2, Volleyball: 2, Baseball, American Football, Handball, Rowing, Judo, Wrestling, Rowing, Track, Field hockey, Tennis, and assorted other sports or trained states.

Table 2A

| Article | Tr | Sex | Age | N | Freq | Wks | Sets | Ex | Reps | Int | Strength | Pre | SD | Post | SD | %Δ | Power | Pre | SD | Post | SD | %Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assuncao et al., 2016 | U | MF | Low rep.: 13.8 ± 0.9 | 17 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 4–6 | 4–6 RM | Low rep.: | |||||||||||

| High rep.: 13.7 ± 0.7 | 16 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 12–15 | 12–15 RM | 1 RM chest press | Effect sizes only | |||||||||||||

| 1 RM squat | Effect sizes only | |||||||||||||||||||||

| High rep.: | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 RM chest press | Effect sizes only | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 RM squat | Effect sizes only | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Benson et al., 2007 | PE | MF | 12.3 ± 1.3 | 32 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 11 | 8 | RPE 15–18 | Bench press | 29.6 | 8.2 | 41.1 | 9.5 | 38.9 | ||||||

| Bench press/kg | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 40.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Leg press | 109.2 | 39.1 | 152.1 | 43.4 | 39.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Leg press/kg | 1.9 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 36.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Blimkie, 1989 | M | 10.4 ± 0.8 | 14 | 3 | 10 | 3–5 | 6 | 10–12 | EF MVIC 100° | 14.7 | 5.3 | 18.0 | 4.8 | 22.4 | ||||||||

| Channell and Barfield, 2008 | T | M | 15.9 ± 1.2 | 21 | 3 | 8 | 3–5 | 2–4 | 3–20 | 60–100% | Squat | 144.0 | 41.6 | 161.6 | 29.3 | 12.2 | CMJ | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 3.4 |

| Power clean | 72.6 | 17.8 | 84.3 | 15.6 | 16.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Squat | 132.6 | 30.9 | 160.9 | 26.0 | 21.3 | CMJ | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 2.1 | |||||||||||

| Power clean | 69.2 | 17.8 | 70.1 | 12.9 | 1.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Chelly et al., 2009 | T | M | 17.0 ± 0.3 | 11 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 2-4 | 80–90% | Squat | 105.0 | 14.0 | 142.0 | 15.0 | 35.2 | SJ | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 9.4 |

| CMJ | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 5.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| 5 Long jump | 10.6 | 0.3 | 11.1 | 0.2 | 4.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| 5 m Velocity m/s | 3.5 | 0.2 | 3.8 | 0.1 | 7.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 40 m Max velocity m/s | 7.8 | 0.5 | 8.8 | 0.4 | 11.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Christou et al., 2006 | T | M | 13.8 ± 0.4 | 9 | 2 | 16 | 2–3 | 10 | 8–15 | 55–80% | Leg press | 102.8 | 2.5 | 163.9 | 7.4 | 59.4 | SJ | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 12.0 |

| Bench press | 36.0 | 1.6 | 55.0 | 3.1 | 52.8 | CMJ | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 20.0 | |||||||||||

| 10 m Sprint | 2.2 | 0.1 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 3.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| 30 m Sprint | 5.1 | 0.2 | 4.9 | 0.1 | 2.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Contreras et al., 2017 | T | M | 15.5 ± 1.2 | 13 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 6–12 | 6–12 RM | Front squat | 77.6 | 12.4 | 83.1 | 13.8 | 7.1 | CMJ | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 3.6 |

| T | Hip thrust | Long jump | 2.3 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 16.3 | |||||||||||||||

| 10 m Sprint | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 1.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 20 m Sprint | 3.1 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.1 | 1.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| 15.5 ± 0.7 | 11 | Front squat | 75.0 | 10.5 | 84.6 | 10.0 | 12.9 | CMJ | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 7.7 | |||||||||

| Front squat | Long jump | 2.3 | 0.2 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 1.8 | ||||||||||||||||

| 10 m Sprint | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| 20 m Sprint | 3.2 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.2 | –0.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Coskun and Sahin, 2014 | U | MF | 18 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 10–12 | 10 RM | Leg press | 27.1 | 8.6 | 42.7 | 12.6 | 57.6 | |||||||

| Dalamitros et al., 2015 | T | M | 14.8 ± 0.5 | 11 | 2 | 24 | 4 | KE PT 60 R | 196.6 | 61.6 | 209.8 | 45.8 | 6.7 | |||||||||

| KE PT 60 L | 188.5 | 47.0 | 206.4 | 44.2 | 9.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| KF PT 60 R | 102.8 | 28.7 | 108.5 | 29.0 | 5.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| KF PT 60 L | 100.7 | 28.6 | 107.5 | 29.7 | 6.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Dorgo et al., 2009 | PE | MF | 16.0 ± 1.2 | 63 | 3 | 18 | 12–28 | 10–14 | Push up | 9.7 | 1.1 | 12.6 | 1.1 | 29.9 | ||||||||

| Pull up | 7.6 | 0.9 | 12.1 | 0.9 | 59.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| dos Santos Cunha et al., 2015 | U | M | 10.4 ± 0.5 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 7 | 6–15 | 60–80% | EF 1 RM kg | 6.4 | 0.8 | 10.6 | 0.9 | 65.6 | |||||||

| EF 1 RM kg/FFM | 2.6 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 0.6 | 65.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| EF Isok 30 | 4.9 | 1.2 | 6.1 | 1.3 | 24.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| EF Isok 90 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 5.2 | 0.8 | 18.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| EF Isom 45 | 4.4 | 1.4 | 6.0 | 1.1 | 36.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| EF Isom 90 | 7.7 | 1.9 | 9.3 | 1.8 | 20.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| KE 1 RM kg | 10.8 | 1.6 | 18.7 | 2.0 | 73.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| KE 1 RM kg/FFM | 1.1 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 81.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| KE Isok 30 | 7.6 | 1.1 | 9.6 | 1.3 | 26.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| KE Isok 90 | 6.5 | 0.5 | 8.3 | 0.7 | 27.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| KE Isom 45 | 8.5 | 1.6 | 9.5 | 1.2 | 11.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| KE Isom 90 | 9.8 | 1.5 | 11.8 | 1.7 | 20.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| KE PT 60 R | 196.6 | 61.6 | 209.8 | 45.8 | 6.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| KE PT 60 L | 188.5 | 47.0 | 206.4 | 44.2 | 9.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| KF PT 60 R | 102.8 | 28.7 | 108.5 | 29.0 | 5.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| KF PT 60 L | 100.7 | 28.6 | 107.5 | 29.7 | 6.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Overhead press 10 RM | 7.5 | 2.5 | 14.1 | 3.1 | 87.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Faigenbaum et al., 1996 | U | MF | 10.8 ± 0.4 | 15 | 2 | 8 | 2–3 | 5 | 6 | 8 RM | Leg extension 6 RM | 18.0 | 1.8 | 28.0 | 4.6 | 55.6 | CMJ | 23.5 | 1.4 | 24.9 | 1.5 | 6.0 |

| Chest press 6 RM | 21.8 | 2.2 | 30.1 | 4.6 | 38.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Faigenbaum et al., 1999 | U | MF | 7.8 ± 1.4 | 15 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 11 | 6–8 | Fail | Chest press | 24.5 | 5.9 | 25.8 | 6.4 | 5.3 | ||||||

| Leg extension | 18.4 | 7.0 | 24.1 | 7.6 | 31.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| 8.5 ± 1.6 | 16 | 13–15 | Fail | Chest press | 25.7 | 9.1 | 29.9 | 9.7 | 16.3 | |||||||||||||

| Leg extension | 19.3 | 9.0 | 27.2 | 10.9 | 40.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Faigenbaum et al., 2001 | U | MF | 8.1 ± 1.6 | 44 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 6–8 | Heavy load chest press | 24.5 | 5.9 | 25.8 | 6.4 | 5.3 | |||||||

| 13-15 | Moderate load chest press | 25.7 | 9.1 | 29.9 | 9.7 | 16.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Heavy med ball chest press | 23.8 | 4.3 | 27.8 | 4.1 | 16.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Med ball chest press | 24.1 | 3.9 | 25.8 | 3.8 | 7.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Faigenbaum et al., 2002 | U | MF | 9.7 ± 1.4 | 20 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 12 | 10–15 | 10–15 RM | Chest press | 21.7 | 7.0 | 24.2 | 7.7 | 11.5 | Long jump | 129.5 | 5.6 | 139.5 | 15.6 | 7.7 |

| Leg press | 56.9 | 24.0 | 71.1 | 27.5 | 25.0 | CMJ | 22.8 | 3.9 | 24.9 | 4.5 | 9.2 | |||||||||||

| Grip strength | 35.8 | 6.9 | 38.2 | 7.4 | 6.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Faigenbaum et al., 2007a | PE | MF | 13.9 ± 0.4 | 22 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 12–15 RM | Squat 10 RM | 56.9 | 15.0 | 67.6 | 15.4 | 18.8 | Med ball throw | 356.5 | 55.1 | 368.3 | 59.1 | 3.3 |

| Bench press 10 RM | 41.1 | 9.4 | 47.4 | 10.5 | 15.3 | CMJ | 48.9 | 6.6 | 51.1 | 8.6 | 4.5 | |||||||||||

| Faigenbaum et al., 2014 | PE | MF | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 21 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 7–10 | Pull up | 7.6 | 0.9 | 10.3 | 0.9 | 35.5 | Long jump | 111.9 | 11.2 | 116.4 | 11.6 | 4.0 | |

| Push up | 1.9 | 2.5 | 31.6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Faigenbaum et al., 2015 | PE | MF | 9.5 ± 0.3 | 20 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 13 | 30–45 Sec | Push up | 11.5 | 0.9 | 15.9 | 1.8 | 38.3 | Long jump | 121.2 | 5.4 | 130.2 | 6.3 | 7.4 | |

| Faigenbaum et al., 2007b | T | M | 13.6 ± 0.7 | 14 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 10–12 | 12 RM | CMJ | 48.2 | 10.7 | 49.6 | 10.1 | 2.9 | ||||||

| Long jump | 190.0 | 23.1 | 192.2 | 25.4 | 1.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ball toss | 321.7 | 58.0 | 339.4 | 85.2 | 5.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Falk and Mor, 1996 | MF | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 14 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 15 | 15 RM | Long jump | 101.0 | 13.0 | 115.0 | 18.0 | 13.9 | |||||||

| Ball put | 233.0 | 28.0 | 244.0 | 43.0 | 4.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ferrete et al., 2014 | T | MF | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 11 | 2 | 26 | 2–4 | 6 | 6–10 | CMJ | 22.3 | 0.7 | 23.8 | 4.3 | 6.7 | |||||||

| Flanagan et al., 2002 | T | MF | 8.8 ± 0.5 | 14 | 2 | 11 | 1–3 | 8 | 10–15 | Med ball (resisted) | 321.8 | 29.9 | 336.0 | 26.0 | 4.0 | |||||||

| T | 8.6 ± 0.5 | 24 | 2 | 11 | Var | 5 | Var | Long jump (resisted) | 134.3 | 32.8 | 148.7 | 25.9 | 9.0 | |||||||||

| Med ball (BW) | 234.3 | 34.5 | 267.9 | 39.2 | 12.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Long jump (BW) | 138.5 | 21.8 | 144.8 | 16.4 | 4.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Funato et al., 1986 | PE | MF | 11.0 ± 0.3 | 20 | 3 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 100% MVIC | EF MVIC | 5.7 | ||||||||||

| EE MVIC | 17.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Gonzalez-Badillo et al., 2015 | T | M | U16: 14.9 ± 0.3 | 17 | 2 | 26 | 2–4 | 7 | 5–10 and 20 m | 40-105% | CMJ (U16) | 35.4 | 3.9 | 39.1 | 4.9 | 10.5 | ||||||

| U18: 17.8 ± 0.4 | 16 | 2 | 26 | 2–4 | 7 | 5–10 and 20 m | 40–105% | CMJ (U18) | 38.4 | 3.0 | 41.3 | 4.5 | 7.6 | |||||||||

| Gorostiaga et al., 1999 | T | M | 15.1 ± 0.7 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 40–90% | KE force | 208.0 | 29.1 | 235.8 | 41.1 | 13.4 | Throwing velocity | 71.7 | 6.7 | 74.0 | 7.0 | 3.2 | |

| SJ | 32.2 | 3.2 | 33.3 | 3.3 | 3.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| T | 15.1 ± 0.5 | KF force | 100.0 | 12.2 | 109.0 | 15.4 | 9.0 | CMJ | 34.1 | 3.1 | 35.2 | 3.6 | 3.2 | |||||||||

| Granacher et al., 2010 | PE | MF | 8.6 ± 0.5 | 17 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 10–12 | 70–80% | Isok KE 60 | 40.1 | 8.6 | 47.8 | 8.7 | 19.2 | CMJ | 21.5 | 2.6 | 22.2 | 2.7 | 3.3 |

| Isok KF 60 | 32.8 | 5.2 | 37.1 | 7.1 | 13.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Isok KE 180 | 33.1 | 5.4 | 38.3 | 6.6 | 15.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Isok KF 180 | 28.7 | 3.6 | 32.1 | 4.2 | 11.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Granacher et al., 2011b | PE | MF | 16.7 ± 0.6 | 14 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 30–40% | KE MVIC | 1501 | 404 | 1632 | 304 | 8.7 | CMJ | 27.4 | 4.5 | 29.5 | 4.9 | 7.7 |

| Ballistic | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Granacher et al., 2011a | PE | MF | 8.6 ± 0.5 | 17 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 10–12 | 70–80% | Iso KE 60 | 40.1 | 8.6 | 47.8 | 8.7 | 19.2 | CMJ | 21.5 | 2.6 | 22.2 | 2.7 | 3.3 |

| Isok KF 60 | 32.8 | 5.2 | 37.1 | 7.1 | 13.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Isok KE 180 | 33.1 | 5.4 | 38.3 | 6.6 | 15.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Granacher et al., 2014 | T | MF | 13.7 ± 0.6 | 13 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 40–50 s or 20–25 | CSTS ventral TMS | 65.5 | 37.0 | 74.7 | 39.3 | 14.0 | CSTS long jump | 187.6 | 47.4 | 189.6 | 39.0 | 1.1 | |

| 13.8 ± 0.9 | 14 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 40–50 s or 20–25 | CSTS dorsal TMS | 152.2 | 98.0 | 214.8 | 32.8 | 41.1 | ||||||||||

| CSTS lateral right TMS | 46.9 | 18.9 | 51.1 | 18.3 | 9.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| CSTS lateral left TMS | 46.5 | 20.8 | 51.4 | 18.7 | 10.5 | CSTU long jump | 201.1 | 20.0 | 207.1 | 18.8 | 3.0 | |||||||||||

| CSTU ventral TMS | 67.9 | 34.1 | 83.1 | 28.7 | 22.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| CSTU dorsal TMS | 129.9 | 55.0 | 173.3 | 20.4 | 33.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| CSTU lateral right TMS | 46.7 | 12.1 | 50.4 | 14.7 | 7.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| CSTU lateral left TMS | 201.1 | 10.3 | 51.4 | 10.6 | 8.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Hammami et al., 2016b | T | M | BPT: 12.7 ± 0.3 | 12 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 8–15 | Max | Isok KF 180 | 28.7 | 3.6 | 23.1 | 4.2 | −19.5 | BPT CMJ | 25.5 | 4.0 | 29.2 | 2.9 | 14.5 |

| PBT: 12.5 ± 0.3 | 12 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 8–15 | Max | PBT CMJ | 24.7 | 2.4 | 26.8 | 1.8 | 8.5 | |||||||||

| BPT long jump | 186.0 | 15.9 | 220.7 | 10.3 | 18.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| PBT long jump | 177.1 | 11.6 | 206.8 | 13.9 | 16.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Bench press throw | 87.9 | 16.9 | 97.5 | 21.2 | 10.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Harries et al., 2016 | T | M | 16.8 ± 1.0 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 1–6 | 10 | 3–10 | 60–90% | Squat | 127.9 | 26.4 | 171.2 | 41.2 | 33.9 | ||||||

| Bench press | 87.9 | 16.9 | 97.5 | 21.2 | 10.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Hettinger, 1958 | NR | MF | <2.9: 12.6 ± 3.8 | 9 | 1–2 | 8–23 | 1 | 2 | 1 | Max | Lower arm flexors (boys maturity <2.9) | 10.9 | 1.7 | 13.0 | 2.1 | 19.3 | ||||||

| >3.0: 12.7 ± 2.3 | 15 | Lower arm flexors (girls maturity <2.9) | 9.4 | 1.3 | 10.7 | 1.5 | 13.8 | |||||||||||||||

| Lower arm extensors (boys maturity <2.9) | 7.7 | 1.0 | 10.8 | 2.4 | 40.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lower arm extensors (girls maturity <2.9) | 6.3 | 1.3 | 8.7 | 1.3 | 38.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lower Arm Flexors (Boys Maturity >3.0) | 19.0 | 3.9 | 23.6 | 4.8 | 24.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lower arm flexors (girls maturity >3.0) | 16.2 | 3.6 | 17.3 | 3.6 | 6.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lower arm extensors (boys maturity >3.0) | 13.1 | 1.3 | 19.0 | 4.7 | 45.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lower arm extensors (girls maturity >3.0) | 10.1 | 2.1 | 12.6 | 2.4 | 24.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ignjatovic et al., 2011 | T | M | 15.7 ± 0.8 | 23 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 8–12 | 8–12 RM | 30% Bench press | 367.2 | 65.4 | 392.4 | 61.3 | 6.9 | ||||||

| 40% Bench press | 405.3 | 71.8 | 432.0 | 68.1 | 6.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| 50% Bench press | 455.9 | 84.5 | 475.0 | 77.1 | 4.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| 60% Bench press | 503.0 | 86.6 | 526.8 | 82.0 | 4.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Kotzamanidis et al., 2005 | T | M | 17.1 ± 1.1 | 11 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 3-8 | 8,6,3 RM | Half squat | 140.5 | 15.6 | 154.5 | 15.7 | 10.0 | Squat jump | 25.7 | 3.1 | 26.2 | 3.5 | 1.9 | |

| Step up | 65.5 | 7.6 | 76.4 | 7.1 | 16.7 | 40 cm DJ | 18.4 | 5.5 | 18.9 | 5.5 | 2.6 | |||||||||||

| Leg curl | 53.6 | 6.7 | 62.3 | 5.6 | 16.1 | CMJ | 27.2 | 3.4 | 27.5 | 3.3 | 0.9 | |||||||||||

| 30 m Sprint | 4.3 | 0.2 | 4.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lloyd et al., 2016 | PE | M | Pre-PHV: 12.7 ± 0.3 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 10 RM | Pre-PHV squat jump | 22.3 | 4.9 | 24.8 | 4.6 | 11.2 | ||||||

| Post-PHV: 16.3 ± 0.3 | 10 | Post-PHV squat jump | 32.4 | 5.0 | 34.6 | 5.1 | 6.8 | |||||||||||||||

| Pre-PHV 10 m sprint | 2.3 | 0.2 | 2.2 | 0.2 | 4.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Post-PHV 10 m sprint | 1.9 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 5.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Pre-PHV 20 m sprint | 3.4 | 0.3 | 3.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Post-PHV 20 m sprint | 2.8 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 3.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lubans et al., 2010 | U | MF | 15.0 ± 0.7 | F: 37 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 8–12 | RPE 15–18 | Girls (bench press) FW | 49.9 | 13.0 | 62.0 | 11.9 | 24.2 | ||||||

| E: 41 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 8–12 | RPE 15–18 | Girls (incline leg press) FW | 173.6 | 47.2 | 234.3 | 50.5 | 35.0 | ||||||||||

| Girls (bench press) ET | 50.5 | 15.2 | 56.5 | 14.5 | 11.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Girls (incline leg press) ET | 181.4 | 53.3 | 283.6 | 64.3 | 56.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Boys (bench press) FW | 31.2 | 6.2 | 36.4 | 6.7 | 16.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Boys (incline leg press) FW | 144.8 | 34.2 | 191.0 | 51.3 | 31.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Boys (bench press) ET | 31.7 | 7.2 | 35.9 | 7.1 | 13.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Boys (incline leg press) ET | 156.2 | 20.0 | 186.2 | 30.1 | 19.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Moore et al., 2013 | T | M | 16.0 ± 2.0 | 14 | 3 | 20 | 3 | 20 | Low | Posterior shoulder endurance test | 30.0 | 14.0 | 88.0 | 36.0 | 193.3 | |||||||

| Moraes et al., 2013 | U | M | 15.5 ± 0.9 | 14 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 10–12 | 10–12 RM | Bench press | 40.6 | 6.1 | 48.3 | 7.2 | 19.0 | Long jump | 137.1 | 22.6 | 139.8 | 21.5 | 2.0 |

| Leg press | 231.4 | 39.3 | 435.7 | 37.0 | 88.3 | CMJ | 29.4 | 6.0 | 30.8 | 6.0 | 4.8 | |||||||||||

| Muehlbauer et al., 2012 | PE | M | 16.8 ± 0.8 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 4–6 | 7 | 10 | 30–40% | Boys leg press MVIC | 1786 | 319 | 1912 | 280 | 7.0 | Boys CMJ | 31.1 | 2.2 | 33.3 | 2.9 | 7.1 |

| F | 16.6 ± 0.5 | 8 | Girls leg press MVIC | 1287 | 329 | 1639 | 325 | 27.3 | Girls CMJ | 24.6 | 3.7 | 26.7 | 4.1 | 8.5 | ||||||||

| Negra et al., 2016 | T | M | 12.8 ± 0.2 | 13 | 2 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 8–12 | 40–60% | Squat | 102.0 | 25.2 | 127.8 | 15.2 | 25.3 | Long jump | 1.7 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 15.5 |

| CMJ | 24.1 | 4.6 | 29.8 | 3.4 | 23.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ozmun et al., 1994 | U | MF | 10.5 ± 0.6 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 7–10 | 10 RM | Isok EF | 27.8 | ||||||||||

| Isot EF | 22.6 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Piazza et al., 2014 | T | M | 12.0 ± 1.8 | 19 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 12 RM | Squat jump | 427.1 | 35.3 | 440.1 | 28.0 | 3.0 | ||||||

| CMJ | 449.7 | 34.5 | 481.3 | 30.8 | 7.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Pikosky et al., 2002 | 11.0 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 15 | 15 RM | Chest press | 22.7 | 1.5 | 25.1 | 1.7 | 10.6 | |||||||||

| KE | 18.6 | 2.4 | 31.1 | 3.2 | 67.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Pesta et al., 2014 | U | M | 15.3 ± 1.0 | 13 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 12 | KE MVIC | 1245 | 226 | 1329 | 225 | 6.8 | Squat jump | 31.5 | 3.6 | 35.9 | 5.9 | 14.0 | |

| CMJ | 33.5 | 4.4 | 37.8 | 5.8 | 12.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Prieske et al., 2016 | T | M | 16.6 ± 1.1 | 20 | 2–3 | 9 | 2–3 | 5 | 15–20 | Trunk flexors MVIC | 657 | 92 | 681 | 89 | 3.7 | CMJ | 36.0 | 3.4 | 35.5 | 3.2 | –1.4 | |

| (Stable) | Trunk extensors MVIC | 603 | 98 | 644 | 93 | 6.8 | 20 m Sprint | 3.0 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | ||||||||||

| Prieske et al., 2016 | T | M | 16.6 ± 1.0 | 19 | 2–3 | 9 | 2–3 | 5 | 15–20 | Trunk flexors MVIC | 624 | 99 | 617 | 97 | –1.1 | CMJ | 34.0 | 3.4 | 34.3 | 2.7 | 0.9 | |

| (Unstable) | Trunk extensors MVIC | 591 | 67 | 614 | 115 | 3.8 | 20 m Sprint | 3.0 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | ||||||||||

| Ramsay et al., 1990 | U | M | 9–11 | 13 | 3 | 20 | 3–5 | 6 | Failure | 70–85% | Bench press | 34.6 | ||||||||||

| Leg press | 22.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Isok PT EF | 25.8 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Isok PT KE | 21.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Rhea et al., 2008 | 17.4 ± 2.1 | 32 | 1–3. | 12 | 4 | 5 | 5–10 | 75–85% | CMJ (W) | 928.3 | 229.1 | 1145.4 | 285.9 | 23.4 | ||||||||

| Riviere et al., 2017 | T | M | 17.8 ± 0.9 | Traditional: 8 | 2 | 6 | 3–6 | 6 | 2–4 | 70–90% | Bench press | 105.6 | 23.3 | 110.6 | 24.7 | 4.7 | ||||||

| Variable: 8 | Bench press | 95.6 | 9.6 | 100.6 | 10.9 | 5.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Rodriguez-Rosell et al., 2016 | 12.6 ± 0.5 | 15 | 2 | 6 | 2–3 | 4 | 4–8 | 45–60% | Squat (U 13) | 38.6 | 17.9 | 57.2 | 15.9 | 48.2 | 10 m Sprint (U13) | 1.9 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 3.2 | ||

| 14.6 ± 0.5 | 14 | Squat (U 15) | 64.0 | 14.5 | 81.7 | 16.6 | 27.7 | 20 m Sprint (U13) | 3.4 | 0.1 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 2.7 | |||||||||

| CMJ (U13) | 26.6 | 4.3 | 29.8 | 3.9 | 12.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 m Sprint (U15) | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| 20 m Sprint (U15) | 3.1 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.1 | 1.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| CMJ (U15) | 32.4 | 5.2 | 35.7 | 6.1 | 10.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Sadres et al., 2001 | MF | 9.2 ± 0.3 | 27 | 2 | 84 | 1–4 | 3–6 | 5–30 | 30–70% | KE | 18.0 | 5.0 | 31.3 | 7.0 | 73.9 | |||||||

| KF | 9.0 | 4.0 | 16.8 | 4.5 | 86.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Sander et al., 2013 | T | M | 13.1 | 18 | 2 | 104 | 5 | 5 | 4–10 | 4–10 RM | Back squat | 25.0 | 9.6 | 90.0 | 13.5 | 260.0 | ||||||

| Front squat | 21.4 | 8.5 | 81.4 | 14.4 | 280.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Santos and Janeira, 2012 | T | M | 14.5 ± 0.6 | 15 | 3 | 10 | 2–3 | 6 | 10–12 | 10 RM | Med ball throw 3 kg | 3.4 | 0.4 | 3.7 | 0.4 | 7.6 | ||||||

| Squat jump | 24.8 | 3.3 | 27.9 | 4.0 | 12.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| CMJ | 33.3 | 4.3 | 36.7 | 4.2 | 10.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Depth jump | 34.8 | 4.1 | 38.1 | 4.3 | 9.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Sarabia et al., 2015 | T | M | 15.0 ± 1.0 | 11 | 2 | 11 | 3–6 | 2 | Half Squat | 627.9 | 183 | 685.1 | 182 | 9.1 | CMJ | 31.2 | 3.6 | 32.5 | 2.3 | 4.1 | ||

| Bench press | 328.0 | 42 | 341.1 | 49 | 4.0 | Squat jump | 28.5 | 3.6 | 31.2 | 2.3 | 9.6 | |||||||||||

| Med ball throw | 9.4 | 1.0 | 10.6 | 1.0 | 13.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Sewall and Micheli, 1986 | NR | MF | 10–11 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 50–100% | Isom KE | 19.8 | 24.1 | 21.7 | ||||||||

| Isom KF | 12.6 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Isom SE | 16.3 | 21.2 | 30.1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Isom SF | 5.8 | 7.7 | 32.8 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Siegel et al., 1989 | U | MF | 8.4 ± 0.5 | 50 | 3 | 12 | Var | Var | Var | Var | Boys (N = 26) | |||||||||||

| Cable flexion | 11.4 | 2.3 | 11.3 | 2.3 | –0.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Cable extension | 12.7 | 2.5 | 12.6 | 2.5 | –0.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Handgrip right | 13.4 | 3.1 | 14.9 | 3.3 | 11.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Handgrip left | 12.8 | 3.2 | 14.0 | 3.2 | 9.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Chin up | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 58.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Girls (N = 24) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cable flexion | 11.2 | 1.7 | 11.8 | 1.9 | 5.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Cable extension | 10.1 | 2.3 | 9.3 | 2.0 | –7.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Handgrip right | 10.5 | 2.0 | 11.9 | 2.7 | 13.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Handgrip left | 9.9 | 2.1 | 11.3 | 2.6 | 14.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Chin up | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 50.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Steele et al., 2017 | U | MF | 14.0 ± 1.0 | 17 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 4–6 | 4–6 RM | Bench press | 31.4 | 7.0 | 36.0 | 2.8 | 14.6 | ||||||

| U | MF | 14.0 ± 1.0 | 16 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 12–15 | 12–15 RM | Bench press | 30.9 | 7.0 | 35.3 | 2.8 | 14.2 | |||||||

| Teng et al., 2008 | 14.0 ± 1.0 | 12 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 10 | Isok KF | 54.0 | 18.0 | 57.0 | 16.0 | 5.6 | ||||||||||

| Isok KE | 106.0 | 20.0 | 118.0 | 26.0 | 11.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Tran et al., 2015 | T | MF | 14.0 ± 1.1 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 5–12 | Isom mid thigh pull | 12.7 | CMJ | 5.7 | |||||||||

| Tsolakis et al., 2004 | U | M | 11.8 ± 0.8 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 10 RM | Isom EF | 85.1 | 8.3 | 100.2 | 8.4 | 17.7 | ||||||

| Isot EF | 3.2 | 1.6 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 24.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Velez et al., 2010 | PE | MF | 16.1 ± 0.2 | 13 | 3 | 12 | 2–3 | 12 | 10–15 | 10 RM bench press | 42.0 | 19.2 | 49.5 | 19.8 | 17.9 | |||||||

| 10 RM seated row | 61.5 | 21.9 | 71.0 | 24.7 | 15.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 RM shoulder press | 38.0 | 21.3 | 49.3 | 4.7 | 29.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 RM squat | 105.0 | 33.5 | 152.1 | 52.8 | 44.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Weakley et al., 2017 | T | M | 16.9 ± 0.4 | 35 | 1 | 12 | 5 | Squat | 77.4 | 32.6 | 96.0 | 18.6 | 24.0 | 10 m Sprint | 1.9 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.1 | –0.5 | |||

| Bench press | 68.5 | 12.8 | 75.2 | 10.6 | 9.8 | 40 m Sprint | 5.8 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |||||||||||

| CMJ | 33.8 | 5.2 | 36.2 | 5.6 | 0.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Weltman et al., 1986 | T | M | 8.2 ± 1.3 | 16 | 3 | 14 | 10 | 30 sec | KF 30°·s | 19.5 | 5.4 | 24.1 | 7.5 | 23.6 | Long jump | 124.8 | 14.3 | 128.6 | 19.2 | 3.0 | ||

| KF 90°·s | 16.2 | 3.8 | 19.6 | 6.3 | 21.0 | CMJ | 21.1 | 4.8 | 23.3 | 3.4 | 10.4 | |||||||||||

| KE 30°·s | 26.9 | 10.3 | 33.5 | 12.2 | 24.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| KE 90°·s | 23.6 | 9.1 | 28.0 | 13.1 | 18.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| EF 30°·s | 11.3 | 3.7 | 14.6 | 5.5 | 29.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| EF 90°·s | 10.1 | 4.0 | 13.8 | 5.7 | 36.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| EE 30°·s | 11.5 | 3.3 | 15.2 | 3.6 | 32.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| EE 90°·s | 11.2 | 3.2 | 13.3 | 3.3 | 18.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Wong et al., 2010 | M | 13.5 ± 0.7 | 28 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 7–10 | 5–15 | CMJ | 55.5 | 6.6 | 58.8 | 7.3 | 5.9 | ||||||||

| 10 m Sprint | 2.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 4.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| 30 m Sprint | 4.9 | 0.3 | 4.7 | 0.3 | 2.2 |

Strength type resistance training program descriptions.

%Δ, Percent change from pre-test to post-test; BPT, balance training before plyometric training; BW, bodyweight; cm, centimeter; CMJ, counter movement jump; CSTS, core strength training on stable surface; CSTU, core strength training on unstable surface; EE, elbow extension; EF, elbow flexor; ET, elastic tubing; Ex, exercises; FFM, fat free mass; Freq, frequency; FW, free weight; Int, intensity; Isok, isokinetic; Isom, isometric; Isot, isotonic; KE, knee extension; KF, knee flexion; kg, kilogram; m, meter; Med, Medicine; Mod, moderate; MVIC, maximal voluntary isometric contraction; N, number of participants; PBT, plyometric training before balance training; PE, physical education students; PHV, peak height velocity; Post, post-test; Power, power measures; Pre, pre-test; PT, peak torque; Reps, repetitions; RM, repetition maximum; RPE, rating of perceived exertion; s, second; SD, standard deviation; Strength, strength measures; T, trained youth; TMS, trunk muscle strength; Tr, training status; U, untrained youth; Var, varied; Wks, weeks.

Additional Citations for Table 2A are found in the text reference list (Hettinger, 1958; Funato et al., 1986; Sewall and Micheli, 1986; Weltman et al., 1986; Blimkie, 1989; Ozmun et al., 1994; DeRenne et al., 1996; Gorostiaga et al., 1999; Sadres et al., 2001; Flanagan et al., 2002; Pikosky et al., 2002; Tsolakis et al., 2004; Drinkwater et al., 2005; Benson et al., 2007; Faigenbaum et al., 2007a, 2014, 2015; Channell and Barfield, 2008; Rhea et al., 2008; Teng et al., 2008; Chelly et al., 2009; Dorgo et al., 2009; Lubans et al., 2010; Velez et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2010; Ebada, 2011; Granacher et al., 2011a,b, 2014, 2015; Ignjatovic et al., 2011; Muehlbauer et al., 2012; Santos and Janeira, 2012; Moore et al., 2013; Moraes et al., 2013; Sander et al., 2013; Coskun and Sahin, 2014; Ferrete et al., 2014; Pesta et al., 2014; Piazza et al., 2014; Dalamitros et al., 2015; Gonzalez-Badillo et al., 2015; dos Santos Cunha et al., 2015; Sarabia et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2015; Eather et al., 2016; Harries et al., 2016; Lloyd et al., 2016; Negra et al., 2016; Prieske et al., 2016; Rodriguez-Rosell et al., 2016; Contreras et al., 2017; Steele et al., 2017; Weakley et al., 2017).

Table 2B

| Article | Tr | Sex | Age | N | Freq | Wks | Sets | Ex | Reps | Int | Strength | Pre | SD | Post | SD | % Δ | Power | Pre | SD | Post | SD | % Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alves et al., 2016 | U | MF | 10.9 ± 0.5 | 45 | 2 | 8 | 2–3 | 6 | 4–8 | 1 kg Ball throw | 3.6 | 0.6 | 3.8 | 0.6 | 5.6 | |||||||

| 3 kg Ball throw | 2.2 | 0.4 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 9.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Single leg jump | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 7.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| CMJ | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Arabatzi, 2016 | U | MF | 9.3 ± 0.6 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 8–12 | CMJ | 18.8 | 0.5 | 21.0 | 0.5 | 11.7 | |||||||

| Drop Jump | 20.7 | 0.4 | 22.7 | 0.5 | 9.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Attene et al., 2015 | T | F | 14.9 ± 0.9 | 18 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 6 | CMJ | 26.9 | 3.6 | 30.0 | 3.7 | 11.3 | |||||||

| Squat jump | 22.7 | 3.2 | 26.2 | 3.6 | 15.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Borges et al., 2016 | T | M | 5 m Sprint | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 3.9 | ||||||||||||||

| 30 m Sprint | 4.2 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Buchheit et al., 2010 | T | M | 14.5 ± 0.5 | 8 | 1 | 10 | 4–6 | 4–6 | 10 m | 1.9 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.5 | ||||||||

| 30 m | 4.7 | 0.3 | 4.6 | 0.2 | 1.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| CMJ | 35.4 | 7.8 | 40.6 | 8.8 | 14.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Chaabene and Negra, 2017 | T | M | LPT: 12.7 ± 0.2 | 13 | 2 | 8 | 5–6 | 10–15 | LPT: 5 m sprint | 1.19 | 0.04 | 1.1 | 0.06 | –7.5 | ||||||||

| HPT: 12.7 ± 0.3 | 12 | 2 | 8 | 9–13 | 12–15 | HPT: 5 m sprint | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.16 | 0.09 | –3.3 | |||||||||||

| LPT: 30 m sprint | 4.98 | 0.12 | 4.84 | 0.17 | –2.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| HPT: 30 m sprint | 5.17 | 0.34 | 5.03 | 0.34 | –2.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Chelly et al., 2015 | T | M | 11.9 ± 1.0 | 14 | 4 | 10 | 3–10 | 6 | 3–10 | Squat jump | 0.2 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 14.3 | |||||||

| CMJ | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 8.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Drop jump | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 13.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Cossor et al., 1999 | T | M | 11.7 ± 1.2 | 19 | 3 | 20 | 2 | 15 | 10–15 | |||||||||||||

| Vertical jump | 199.7 | 65.8 | 212.5 | 59.1 | 6.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| de Hoyo et al., 2016 | T | M | SQ: 18 ± 1.0 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 1–3 | 8 | 2–3 | CMJ | 35.5 | 4.3 | 37.9 | 3.6 | 6.8 | |||||||

| RS: 17 ± 1.0 | 20 m Sprint | 3.0 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| PL: 18 ± 1.0 | 50 m Sprint | 6.6 | 0.2 | 6.5 | 0.3 | 1.4 | ||||||||||||||||

| Diallo et al., 2001 | M | 12.3 ± 0.4 | 10 | 3 | 10 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| CMJ | 29.2 | 3.9 | 32.6 | 3.4 | 11.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Squat jump | 27.3 | 4.0 | 29.3 | 3.3 | 7.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Running velocities 20 m (m/sec) | 5.6 | 0.1 | 5.7 | 0.2 | 2.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Faigenbaum et al., 2007b | T | M | 13.4 ± 0.9 | 13 | 2 | 6 | 1–2 | 10–12 | 6–10 | VJ | 43.1 | 8.4 | 46.5 | 9.2 | 7.9 | |||||||

| Long jump | 181.1 | 25.9 | 191.9 | 28.5 | 6.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| 9.1 m sprint | 2.2 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ball toss | 319.2 | 96.9 | 358.4 | 85.2 | 12.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Faigenbaum et al., 2009 | PE | MF | 9.0 ± 0.9 | 40 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 12–14 | 6 | Curl up | 29.1 | 10.7 | 31 | 9.9 | 6.5 | Long jump | 132.0 | 27.5 | 139.9 | 27.0 | 6.0 | |

| 1 | 8 | Push up | 4.6 | 5.6 | 8.7 | 9.5 | 89.1 | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Fernandez-Fernandez et al., 2016 | T | M | 12.5 ± 0.3 | 30 | 5 | 8 | 2–4 | 6–8 | 10–15 | CMJ | 30.1 | 4.3 | 32.0 | 4.1 | 6.3 | |||||||

| 5 m Sprint | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 5.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 20 m Sprint | 3.5 | 0.2 | 3.4 | 0.2 | 3.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Long jump | 184.0 | 11.7 | 200.0 | 17.3 | 8.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Medicine ball throw | 626.0 | 91.6 | 680.0 | 114 | 8.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Granacher et al., 2015 | T | M | 15.0 ± 1.0 | 12 | 2 | 8 | 3–5 | 16 | 5–8 | CMJ IPT | 44.1 | 4.4 | 46.1 | 3.8 | 4.5 | |||||||

| CMJ SPT | 41.1 | 4.2 | 46.4 | 4.9 | 12.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Drop jump IPT | 28.9 | 3.9 | 31.2 | 3.2 | 7.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Drop jump SPT | 27.2 | 4.2 | 30.2 | 2.5 | 11.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 m Sprint IPT | 1.9 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 157.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 m Sprint SPT | 1.9 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 2.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 30 m Sprint IPT | 4.4 | 0.2 | 4.4 | 0.2 | –0.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| 30 m Sprint SPT | 4.5 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 0.3 | 1.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Hall et al., 2016 | T | F | 12.5 ± 1.7 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 1~4 | 20 | 1–6 | CMJ | 43.5 | 6.1 | 45.3 | 5.8 | 4.1 | |||||||

| Hammami et al., 2016b | T | M | BPT: 12.7 ± 0.3 | 12 | 2 | 8 | 1~3 | 10 | 8–15 | CMJ BPT | 25.5 | 4.0 | 29.2 | 2.9 | 14.5 | |||||||

| PBT: 12.5 ± 0.3 | CMJ PBT | 24.7 | 2.4 | 26.8 | 1.8 | 8.5 | ||||||||||||||||

| Long jump BPT | 186.0 | 15.9 | 220.7 | 10.3 | 18.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Long jump PBT | 177.1 | 11.6 | 206.8 | 13.9 | 16.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10-m Sprint BPT | 2.1 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 4.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 m Sprint PBT | 2.1 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 9.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| 30-m Sprint BPT | 5.1 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 0.3 | 2.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| 30 m Sprint PBT | 5.1 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 2.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Hammami et al., 2016a | T | M | 15.7 ± 0.2 | 15 | 2 | 8 | 4–10 | 4 | 7–10 | Dom leg PT (N–m) | 41 | 7 | 46 | 7 | 12.2 | 5 m Sprint | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 7.3 | |

| Hewett et al., 1996 | T | F | 15.0 ± 0.6 | 11 | 3 | 6 | 16 | NonDom leg PT (N–m) | 37 | 7 | 46 | 8 | 24.3 | |||||||||

| Kotzamanidis et al., 2005 | T | M | 17.0 ± 1.1 | 12 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 3–8 | 8,6,3 RM | Half squat | 140.4 | 15.5 | 154.5 | 15.7 | 10.0 | Squat jump | 25.7 | 3.1 | 26.2 | 3.5 | 1.9 | |

| Step up | 65.5 | 7.6 | 76.4 | 7.1 | 16.7 | DJ40 | 18.4 | 5.5 | 18.9 | 5.5 | 2.6 | |||||||||||

| Leg Curl | 53.6 | 6.7 | 62.3 | 5.6 | 16.1 | CMJ | 27.2 | 3.4 | 27.5 | 3.3 | 0.9 | |||||||||||

| 30-m running speed | 4.3 | 0.2 | 4.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Kotzamanidis, 2006 | U | M | 11.1 ± 0.5 | 15 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 10 m speed (s) | 2.3 | 0.2 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 2.2 | |||||||||

| 30 m speed (s) | 5.7 | 0.1 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 3.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vertical jump | 23.0 | 4.5 | 31.0 | 4.1 | 34.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| King and Cipriani, 2010 | T | M | FP: 15.1 ± 0.9 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 3–10 | Vertical jump FP | 68.1 | 67.3 | –1.1 | |||||||||

| SP: 15.2 ± 1.1 | 10 | Vertical Jump SP | 67.2 | 63.6 | –5.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lephart et al., 2005 | T | F | 14.5 ± 1.3 | 14 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 10 | Quads PT 60°/s (%BW) | 211.8 | 45.2 | 227.6 | 23.9 | 7.5 | ||||||||

| Hams PT 60°/s (%BW) | 106.3 | 32.6 | 112.7 | 14.4 | 6.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Quads PT 180°/s (%BW) | 128.5 | 22.9 | 147.2 | 18.1 | 14.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Hams PT 180°/s (%BW) | 88.4 | 23.7 | 83.6 | 16.3 | –5.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Hip abd isom PT (%BW) | 169.4 | 34.1 | 165.5 | 35.6 | –2.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lloyd et al., 2012 | GE9 | M | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 20 | 2 | 4 | 2–4 | 5 | 3–10 | Hopping reactive index | ||||||||||||

| GE 12 | 12.3 ± 0.3 | 22 | GE9 | 0.90 | 0.25 | 0.90 | 0.24 | 0.0 | ||||||||||||||

| GE 15 | 15.3 ± 0.3 | 20 | GE12 | 0.91 | 0.24 | 1.01 | 0.26 | 11.0 | ||||||||||||||

| GE15 | 1.46 | 0.28 | 1.52 | 0.26 | 4.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lloyd et al., 2016 | PE | M | 12.7 ± 0.3 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 3–10 | 10 m sprint pre-PHV | 2.3 | 0.2 | 2.2 | 0.2 | 4.3 | |||||||

| 16.4 ± 0.2 | 10 | 20 m sprint pre-PHV | 3.4 | 0.2 | 3.3 | 0.2 | 2.9 | |||||||||||||||

| Squat jump pre-PHV | 24.6 | 4.9 | 28.3 | 4.6 | 15.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 m sprint post-PHV | 1.9 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 47.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| 20 m sprint post-PHV | 2.7 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 3.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Squat jump post-PHV | 32.3 | 6.4 | 32.7 | 6.3 | 1.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Marques et al., 2013 | T | M | 13.4 ± 1.4 | 26 | 2 | 6 | 2–6 | 8 | 8–30 | CMJ | 7.7 | |||||||||||

| 30 m Sprint | 1.7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Martel et al., 2005 | T | F | 15.0 ± 1.0 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 2–5 | Isok PT Quad 60° | 108 | 29 | 120 | 25 | CMJ | 33.4 | 4.7 | 37.1 | 4.5 | 11.0 | ||

| PT Hamstrings 60° | 69 | 13 | 79 | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||

| PT Quad 180° | 61 | 17 | 69 | 21 | ||||||||||||||||||

| PT Hamstrings 180° | 48 | 13 | 56 | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Marta et al., 2014 | M | 10.8 ± 0.4 | 76 | 2 | 8 | 2–6 | 8 | 3–30 | 1 kg Ball throw T1 | 333.5 | 355.7 | 6.7 | ||||||||||

| 3 kg Ball throw T1 | 213.3 | 233.2 | 9.3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Standing long Jump T1 | 126.8 | 133.8 | 5.6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| CMJ T1 | 21.4 | 22.6 | 5.5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 20 m Sprint T1 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 2.5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 kg Ball throw T2 | 370.2 | 387.5 | 4.7 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3 kg Ball throw T2 | 240.7 | 256.3 | 6.5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Standing long Jump T2 | 121.4 | 127.0 | 4.6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| CMJ T2 | 20.9 | 22.0 | 5.1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 20 m Sprint T2 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 1.8 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Matavulj et al., 2001 | T | M | 15–16 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| DJ 50 cm | 11 | DJ 50 cm | 0.3 | DJ 50 cm | 4.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| DJ 100 cm | 11 | DJ 100 cm | 0.03 | DJ 100 cm | 5.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| McCormick et al., 2016 | T | F | ||||||||||||||||||||

| FP | 16.3 ± 0.7 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 6 | CMJ FP | 48.3 | 5.4 | 50.1 | 5.3 | 3.8 | |||||||||

| SP | 15.7 ± 0.7 | 7 | CMJ SP | 47.7 | 7.1 | 52.6 | 9.4 | 10.3 | ||||||||||||||

| Standing long Jump FP | 176.9 | 18.5 | 187.1 | 14.2 | 6.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Standing long Jump SP | 177.9 | 30.1 | 191.9 | 29.1 | 7.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Meylan and Malatesta, 2009 | T | M | 13.3 ± 0.6 | 14 | 2 | 8 | 2–4 | 4 | 6–12 | 1–5 | SJ | 30.1 | 4.1 | 30.5 | 3.2 | 0.6 | ||||||

| CMJ | 34.6 | 4.4 | 37.2 | 4.5 | 7.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 m Sprint | 1.96 | 0.07 | 1.92 | 0.1 | 2.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Michailidis et al., 2013 | T | M | 10.7 ± 0.7 | 24 | 2 | 12 | 2–4 | 4 | 5–10 | 10 RM Squat | 30 m Sprint | –3.0 | ||||||||||

| CMJ | 27.6 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| SJ | 23.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| DJ | 15.9 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Moran et al., 2016 | T | M | 12.6 ± 0.7 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5–10 | CMJ Pre-PHV | 28.0 | 4.0 | 28.1 | 4.0 | 0.4 | ||||||||

| 14.3 ± 0.6 | 8 | CMJ Mid-PHV | 32.5 | 6.0 | 32.8 | 3.7 | 0.9 | |||||||||||||||

| 10 m Sprint Pre-PHV | 2.3 | 0.1 | 2.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 m Spring mid-PHV | 2.2 | 0.2 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 2.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| 30 m Sprint pre-PHV | 5.5 | 0.3 | 5.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| 30 m Sprint mid-PHV | 5.0 | 0.3 | 4.9 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Noyes et al., 2012 | T | F | 14–17 | 57 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 17 | 5 | VJ | 26.2 | 12.3 | 28.5 | 12.0 | 8.8 | |||||||

| 18 m Sprint | 3.5 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Noyes et al., 2013 | T | F | 15.0 ± 1.0 | 62 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 17 | 5 | 37 m Sprint | 6.1 | 0.4 | 6.0 | 0.4 | 2.0 | |||||||

| VJ 2 Step | 40.7 | 8.9 | 42.1 | 8.3 | 3.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| CMJ | 32.9 | 6.7 | 32.6 | 25.8 | –0.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Noyes et al., 2012 | T | F | 14.5 ± 1.0 | 34 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 17 | 5–25 | Sit-up (reps) | 37.7 | 5.3 | 40.5 | 5.9 | 7.4 | CMJ | 40.1 | 7.1 | 41.5 | 4.5 | 3.5 | |

| Pereira et al., 2015 | T | M | 14.0 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 8–20 | CMJ | 26.9 | 4.5 | 32.3 | 9.0 | 20.1 | |||||||

| Medicine ball throw | 7.5 | 15.2 | 7.9 | 14.3 | 5.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Piazza et al., 2014 | T | F | 11.9 ± 1.0 | 18 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 10 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| SJ | 410.4 | 41.6 | 421.5 | 28.4 | 2.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| CMJ | 457.2 | 30.6 | 485.0 | 33.8 | 6.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Potdevin et al., 2011 | T | M | 14.3 ± 0.2 | 12 | 2 | 6 | 2–10 | 13 | 4–12 | CMJ | 28.9 | 4.8 | 32.5 | 4.2 | 12.2 | |||||||

| SJ | 26.2 | 3.8 | 31.1 | 4.9 | 18.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2013 | T | M | 13.2 ± 1.8 | 38 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 10 | CMJ | 27.0 | 5.8 | 4.3 | |||||||||

| 20 m Sprint | 4.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2014 | T | M | 13.2 ± 1.8 | 38 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 10 | High | CMJ | 26.7 | 4.7 | 2.2 | ||||||||

| 20 m Sprint | 4.39 | 0.48 | 3.7 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2015a | T | M | 11.6 ± 2.7 | 12 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 5–10 | 30 m sprint | 6.0 | 0.6 | 6.5 | |||||||||

| CMJ | 30.5 | 9.3 | 15.4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Horizontal jump | 153.0 | 4.1 | 14.6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2015b | M | NPPT: 13.0 ± 2.1 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 5 | Vert CMJ w/arms | |||||||||||||

| PPT: 12.8 ± 2.8 | 8 | 2 | 5–10 | NPPT | 28.5 | 10.4 | 10.9 | |||||||||||||||

| PPT | 27.9 | 8.7 | 16.6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Horz CMJ w/arms | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| NPPT | 163.0 | 42.6 | 4.6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| PPT | 160.0 | 27.9 | 7.9 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Right leg horiz CMJ w/arms | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| NPPT | 138.0 | 35.3 | 2.8 | |||||||||||||||||||

| PPT | 138.0 | 27.7 | 13.5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Left leg horiz CMJ w/arms | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| NPPT | 136.0 | 42.9 | 14.1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| PPT | 134.0 | 27.0 | 21.2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Maximal kicking velocity | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| NPPT | 68.3 | 15.4 | 5.7 | |||||||||||||||||||

| PPT | 67.1 | 16.3 | 10.1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 10 m sprint time | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| NPPT | 2.6 | 0.4 | 0.9 | |||||||||||||||||||

| PPT | 2.7 | 0.3 | 1.6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ramírez-Campillo et al., 2015c | T | M | BG: 11.0 ± 2.0 | 12 | 2 | 6 | 2–3 | 6 | 5–10 | CMJ: | ||||||||||||

| UG: 11.6 ± 1.7 | 16 | BG | 31.1 | 2.0 | 18.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| BUG: 11.6 ± 2.7 | 12 | UG | 29.5 | 4.3 | 7.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| BUG | 30.5 | 9.3 | 15.4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Horizontal CMJ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BG | 166 | 33 | 17.4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| UG | 153 | 22 | 8.9 | |||||||||||||||||||

| BUG | 153 | 41 | 14.6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Maximal kicking velocity | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BG | 59.2 | 18.4 | 8.4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| UG | 59.9 | 10.8 | 14.0 | |||||||||||||||||||

| BUG | 61.8 | 19.6 | 12.0 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 30 m Sprint | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BG | 5.7 | 0.5 | –3.2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| UG | 6.1 | 0.4 | –6.2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| BUG | 6.0 | 0.6 | –6.5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Rosas et al., 2016 | T | M | 12.3 ± 2.3 | 21 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 4–8 | CMJ | 31.7 | 9.0 | 4.3 | ||||||||||

| Horizontal jump | 159.0 | 35.7 | 6.1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Santos and Janeira, 2012 | T | M | 15.0 ± 0.5 | 14 | 2 | 10 | 2–4 | 6 | 6–15 | Squat jump | 25.2 | 3.5 | 29.2 | 4.1 | 15.8 | |||||||

| CMJ | 30.3 | 4.3 | 34.5 | 5.0 | 13.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Medicine ball throw | 3.4 | 0.4 | 3.9 | 0.4 | 14.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Santos et al., 2012 | U | M | 13.3 ± 1.0 | 30 | 2 | 8 | 1–5 | 7–8 | 3–8 | GR Group | ||||||||||||

| CMJ | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 4.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Long jump | 1.5 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 4.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 kg Medicine ball throw | 7.5 | 1.7 | 8.2 | 1.6 | 8.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| 3 kg Medicine ball throw | 4.7 | 1.0 | 5.1 | 1.1 | 9.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| 20 m | 4.5 | 0.5 | 4.1 | 0.4 | 10.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| GCOM group | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| CMJ | 29.8 | 0.1 | 31.6 | 0.1 | 6.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Long jump | 1.7 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 4.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 kg Medicine ball throw | 7.3 | 1.6 | 7.6 | 1.7 | 4.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| 3 kg Medicine ball throw | 4.6 | 1.1 | 5.1 | 1.2 | 11.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 20 m | 4.4 | 0.6 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 13.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Skurvydas et al., 2010 | M | 10.3 ± 0.3 | 13 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 30 | MVIC | 79.4 | 22.1 | 86.6 | 23.1 | 9.1 | CMJ | 24.1 | 3.8 | 32.8 | 5.1 | 36.1 | ||

| Skurvydas and Brazaitis, 2010 | M | 10.2 ± 0.3 | 13 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 30 | Girls | 21.8 | 3.3 | 29.9 | 3.8 | 37.7 | ||||||||

| Sohnlein et al., 2014 | T | M | 13.0 ± 0.9 | 12 | 2 | 16 | 2–5 | 9 | 6–16 | Max | 10 m Sprint | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 2.2 | ||||||

| 30 m Sprint | 4.4 | 0.2 | 4.3 | 0.1 | 2.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| 5 m Sprint | 1.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 3.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| 20 m Sprint | 3.2 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.1 | 3.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Szymanski et al., 2007 | T | M | 15.4 ± 1.1 | 25 | 3 | 12 | 2 | 7 | 6–10 | Dom TRS | 17.1 | Standing long jump | 2.3 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 7.3 | |||||

| NonDom TRS | 18.3 | Medicine ball hitter's throw | 10.6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Parallel squat (kg) | 106.3 | 23.4 | 145 | 27.7 | 26.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Bench press (kg) | 71.7 | 15.9 | 86.1 | 15.2 | 16.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Thomas et al., 2009 | T | M | 17.3 ± 0.4 | 12 | 2 | 6 | Chu's | 5 m Sprint | ||||||||||||||

| DJ trained | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| CMJ trained | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 m Sprint | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| DJ trained | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 1.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| CMJ trained | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| 20 m Sprint | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| DJ trained | 3.1 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 1.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| CMJ trained | 3.2 | 0.1 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Witzke and Snow, 2000 | PE | F | 14.6 ± 0.5 | 25 | 3 | 12 | 2–3 | Str:7 | 8–12 | 5–15% BW | Leg strength | 96 | 19.9 | 107.7 | 17.3 | 16.7 | Leg power | 392.0 | 82.0 | 445.0 | 91.0 | 13.5 |

| 24 | 2–3 | Plyo: 5–20 | 2–20 | mod-high |

Power (plyometric) resistance training program descriptions.

%Δ, percent change from pre-test to post-test; BPT, balance training before plyometric training; BW, bodyweight; cm, centimeter; CMJ, counter movement jump; DJ, drop jump; Dom, dominant; Ex, exercises; FP, frontal plane; Freq, frequency; GCOM, combined resistance training and endurance; GR, resistance training alone; Int, intensity; IPT, plyometric training on unstable surface; Isok, isokinetic; Isom, isometric; kg, kilogram; m, meter; Mod, moderate; MVIC, maximal voluntary isometric contraction; N, number of participants; Nm, newton meter; NonDom, non-dominant; NPPT, no plyometric training; PBT, plyometric training before balance training; PE, physical education students; Pre, pre-test; PHV, peak height velocity; PL, plyometric; Post, post-test; Power, power measures; PPT, plyometric training; Reps, repetitions; RS, resisted sprinting; s, second; SD, standard deviation; SJ, squat jump; SP, sagittal plane; SPT, plyometric training on stable surface; SQ, squat; ST, Strength; Strength, strength measures; T, trained youth; Tr, training status; TRS, torso rotational strength; U, untrained youth; Wks, weeks.

Additional Citations for Tables 2A,B are found in the text reference list (Hewett et al., 1996; Cossor et al., 1999; Witzke and Snow, 2000; Diallo et al., 2001; Matavulj et al., 2001; Martel et al., 2005; Szymanski et al., 2007; Meylan and Malatesta, 2009; Thomas et al., 2009; Buchheit et al., 2010; King and Cipriani, 2010; Skurvydas and Brazaitis, 2010; Skurvydas et al., 2010; Potdevin et al., 2011; Santos and Janeira, 2011; Lloyd et al., 2012; Noyes et al., 2012, 2013; Santos et al., 2012; Marques et al., 2013; Michailidis et al., 2013; Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2013, 2015a,b; Marta et al., 2014; Piazza et al., 2014; Sohnlein et al., 2014; Attene et al., 2015; Chelly et al., 2015; Pereira et al., 2015; Alves et al., 2016; Arabatzi, 2016; Borges et al., 2016; de Hoyo et al., 2016; Fernandez-Fernandez et al., 2016; Hall et al., 2016; McCormick et al., 2016; Moran et al., 2016; Rosas et al., 2016).

Muscle power (jump) measures

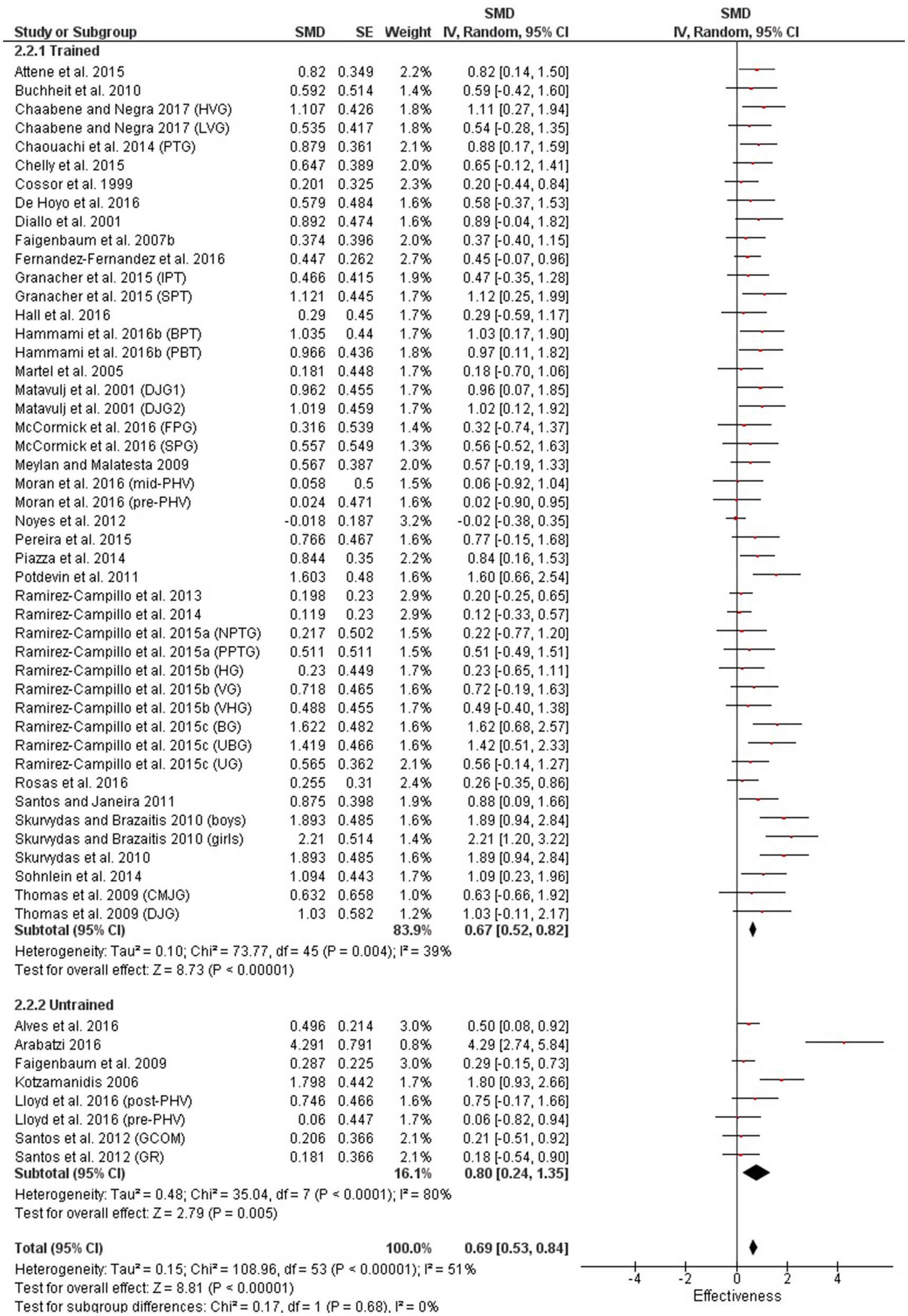

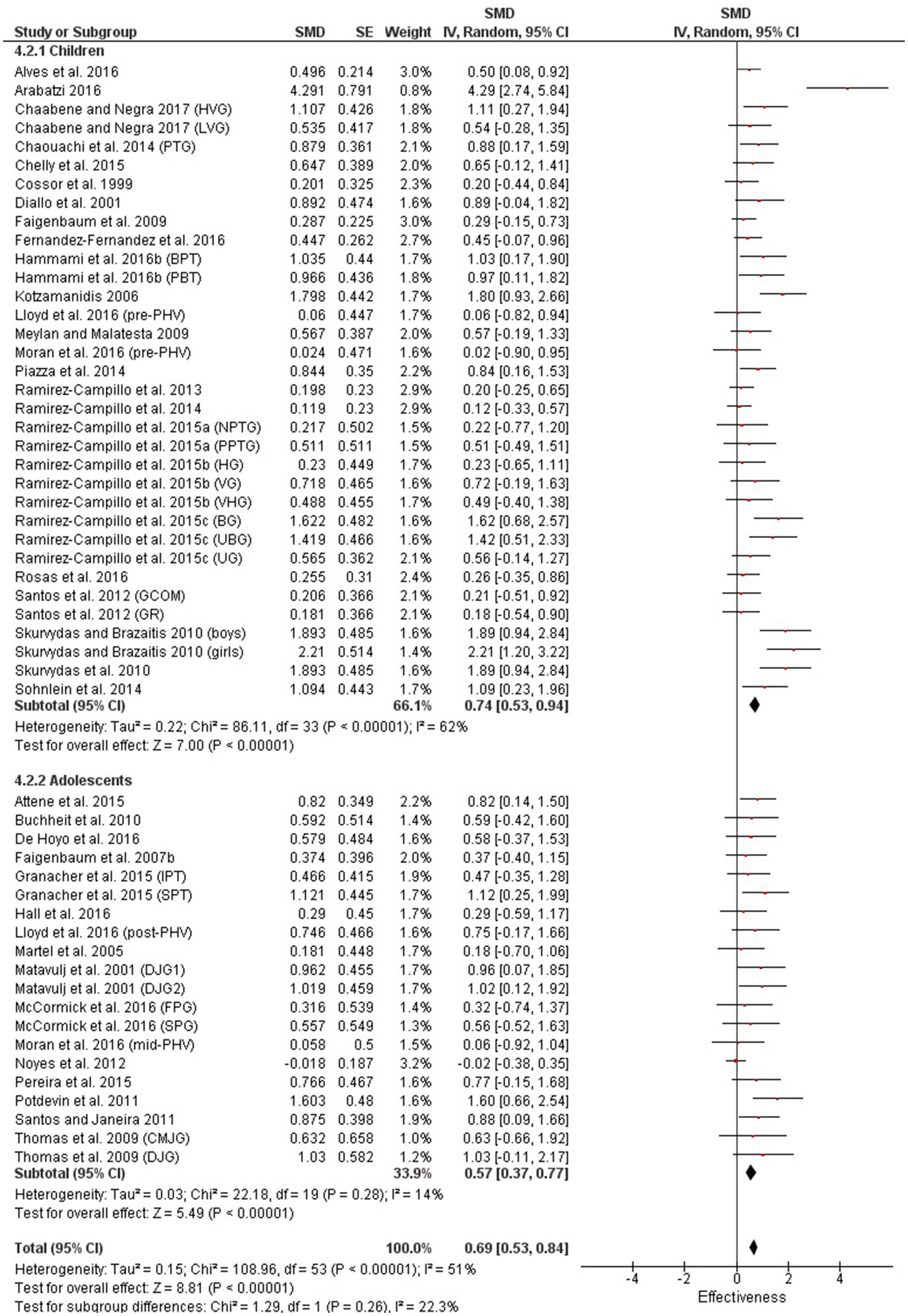

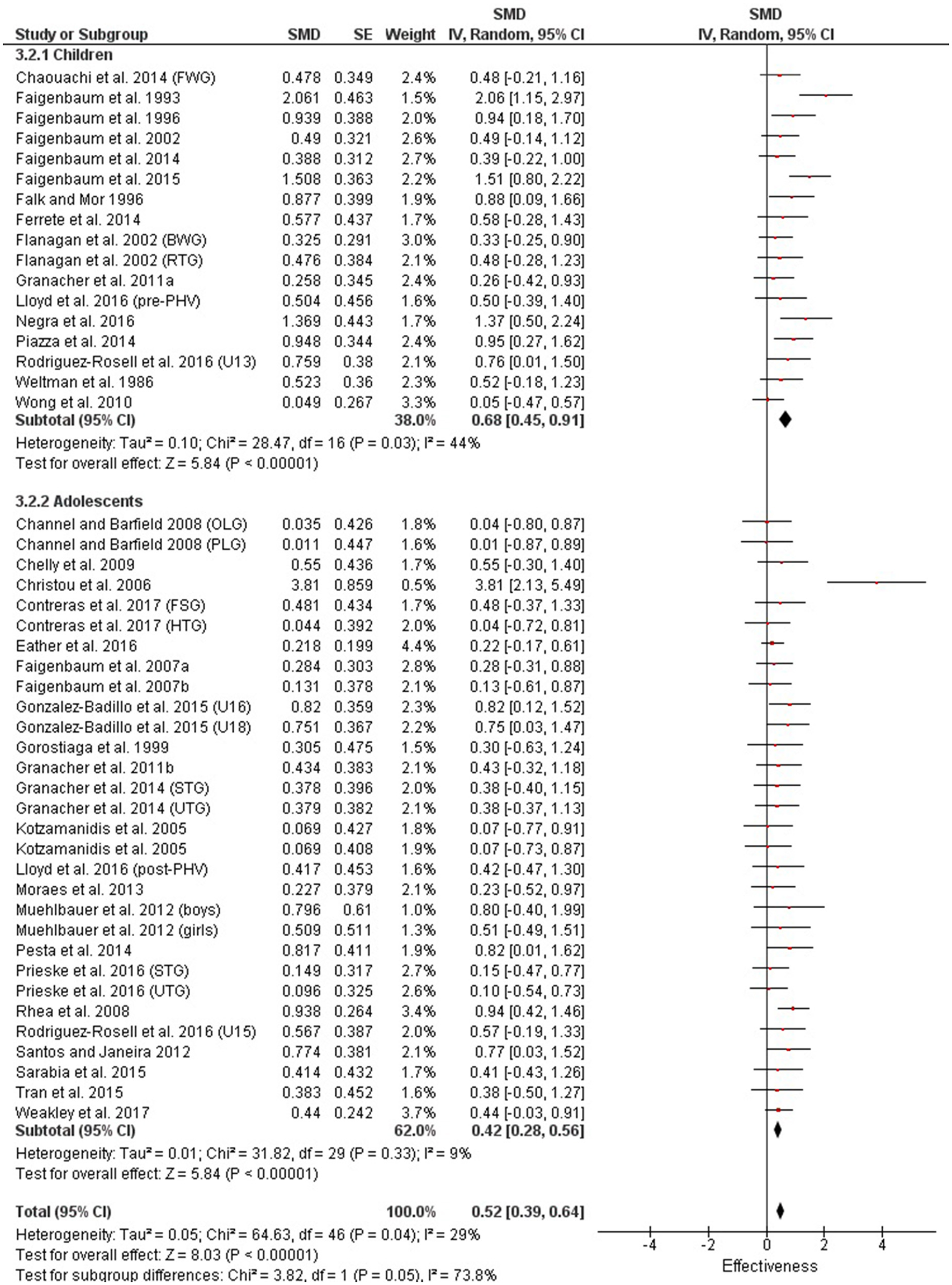

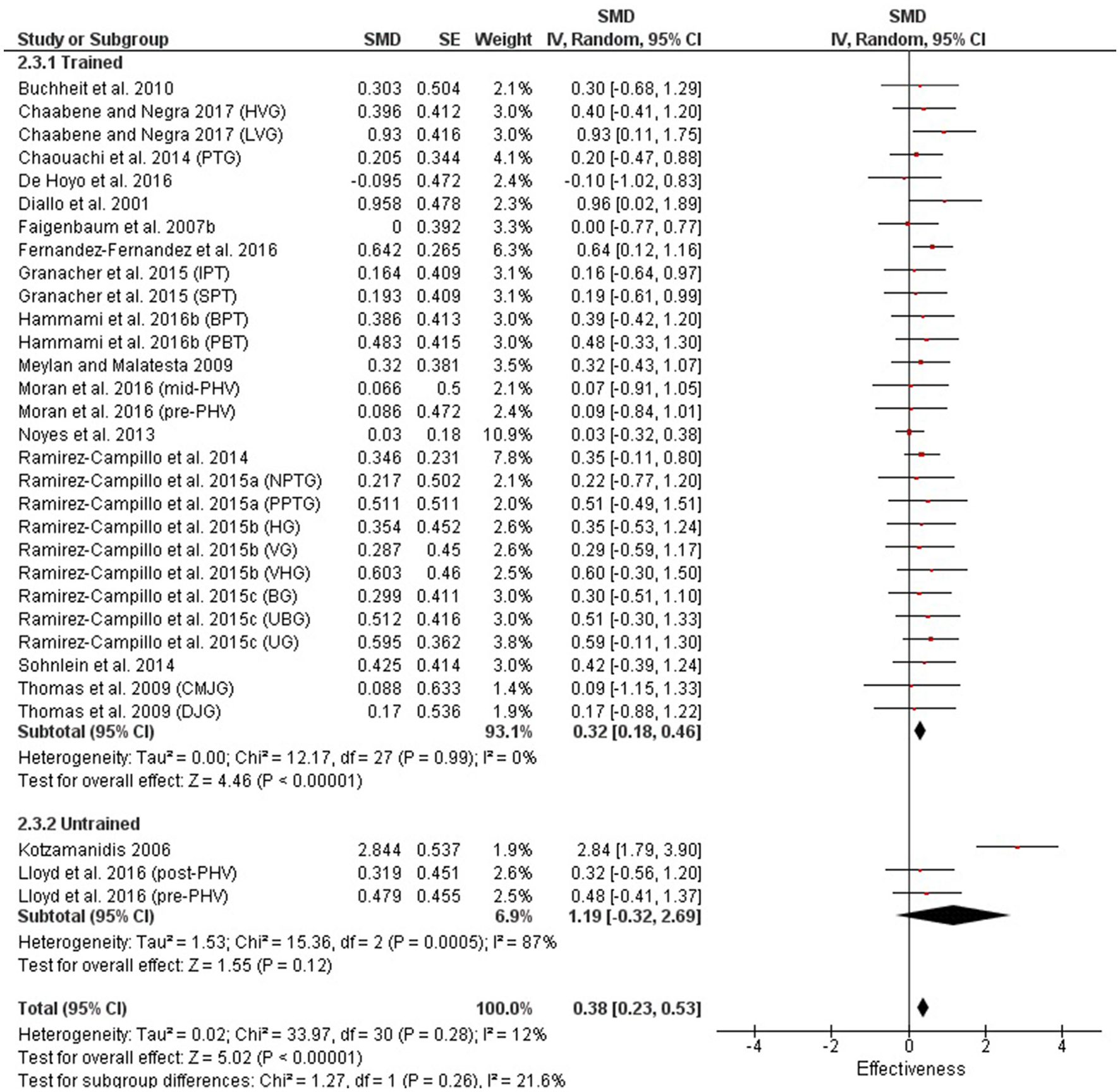

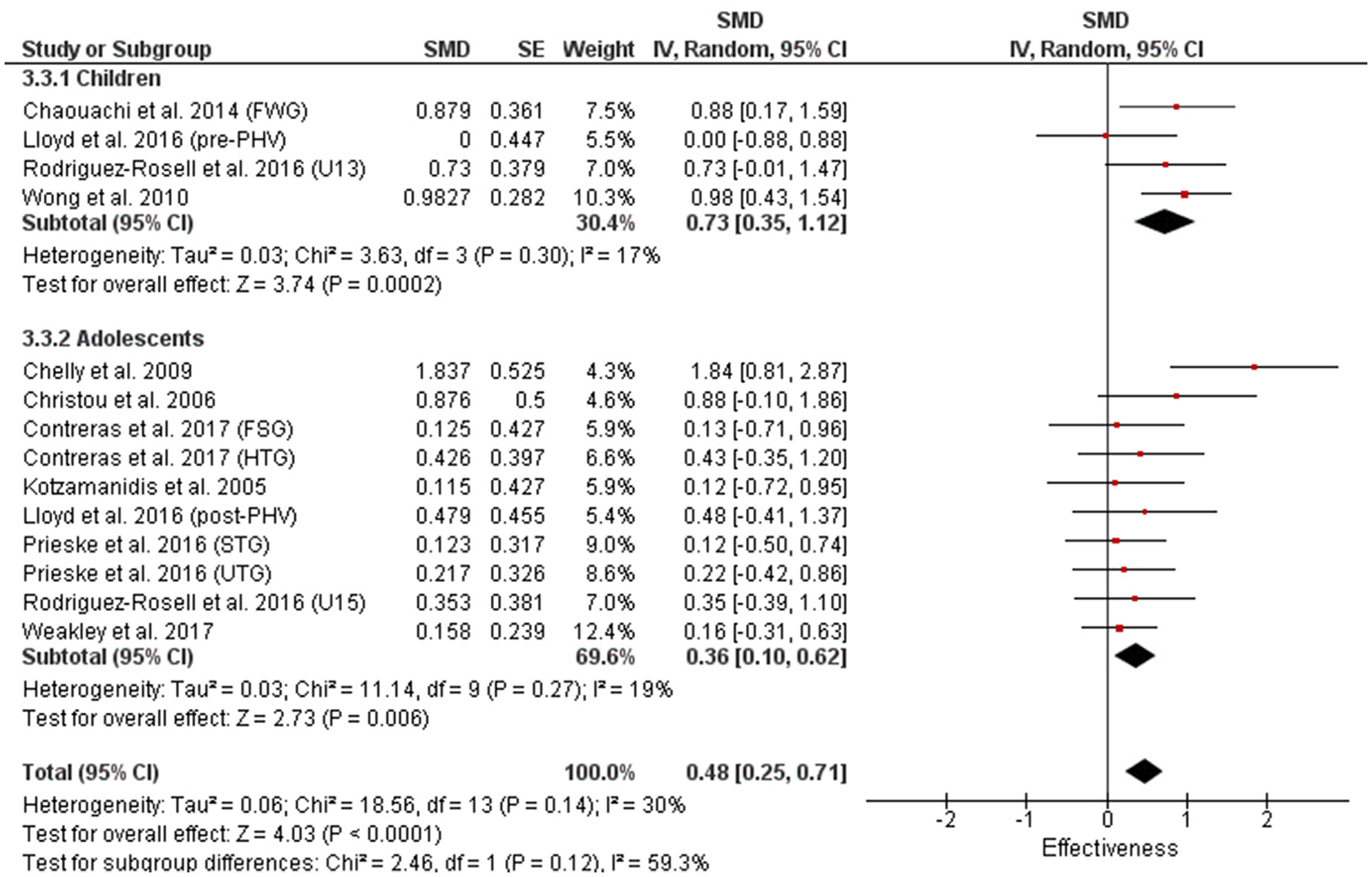

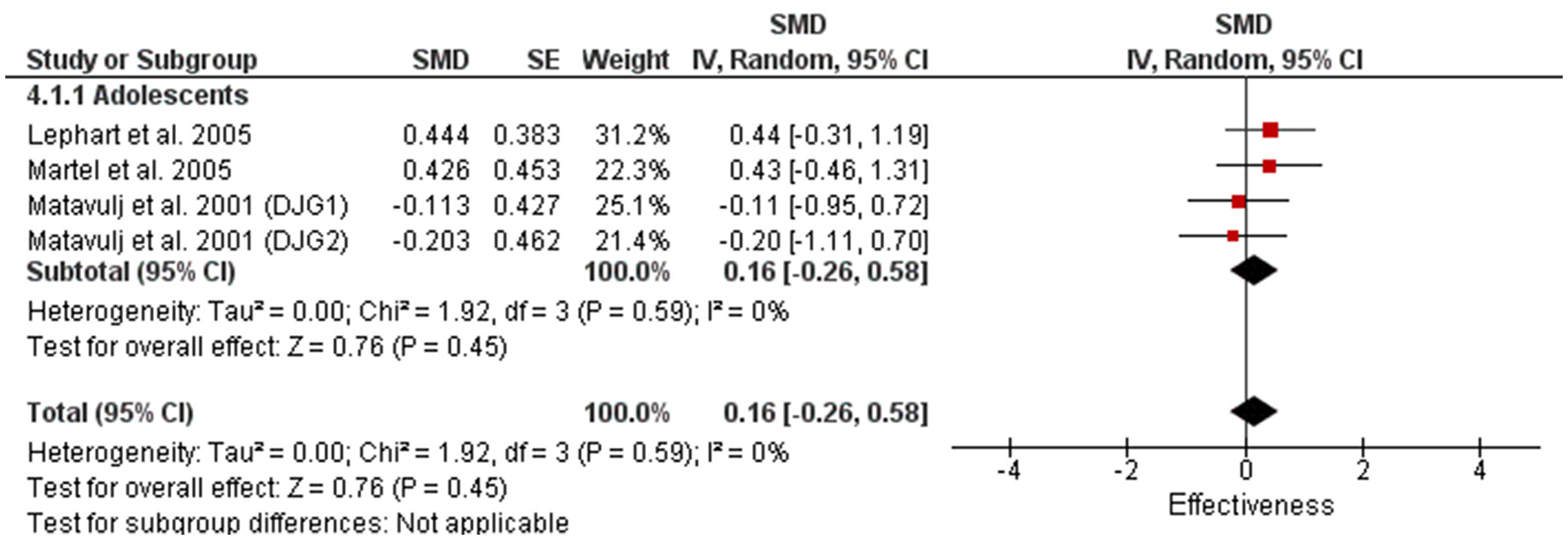

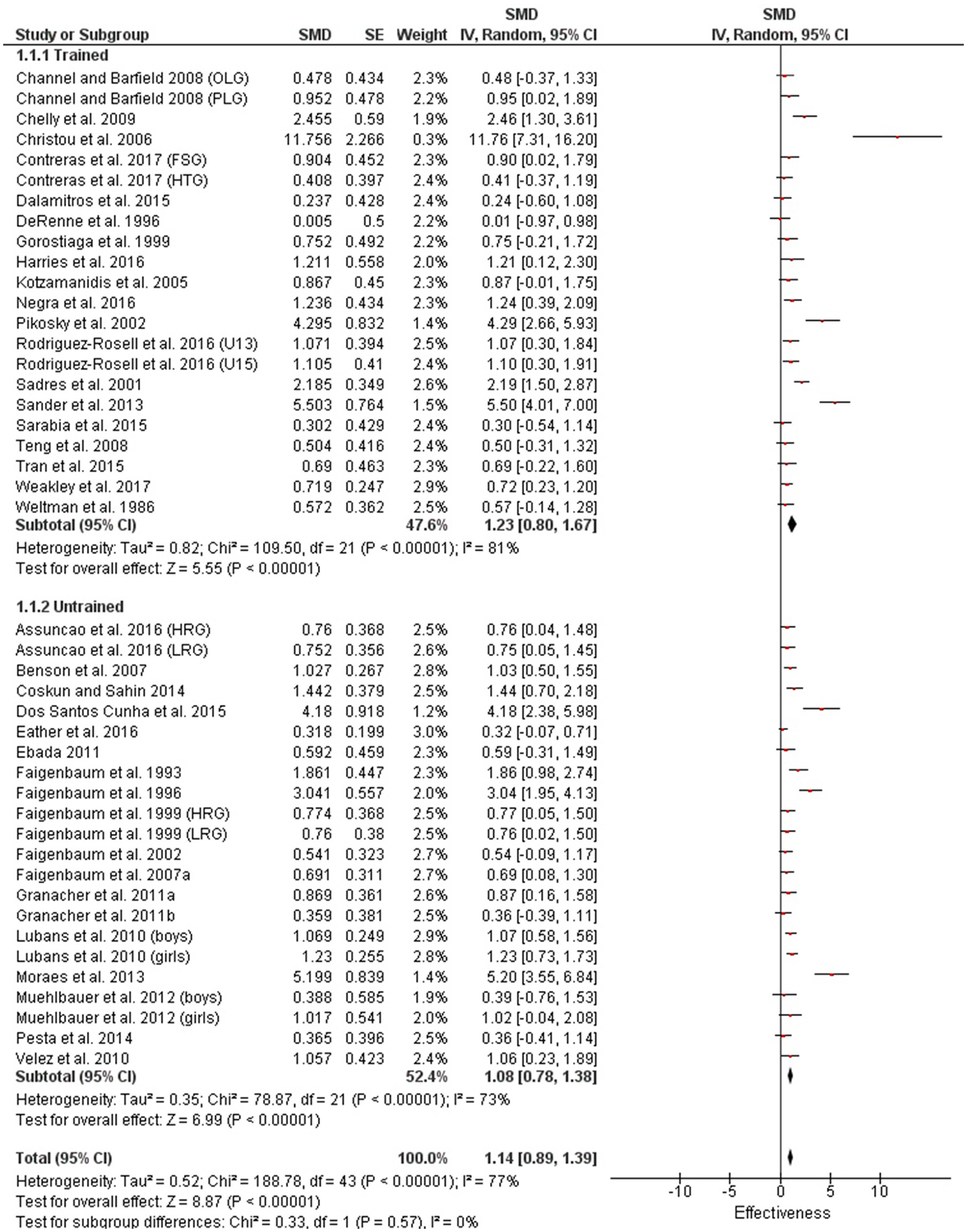

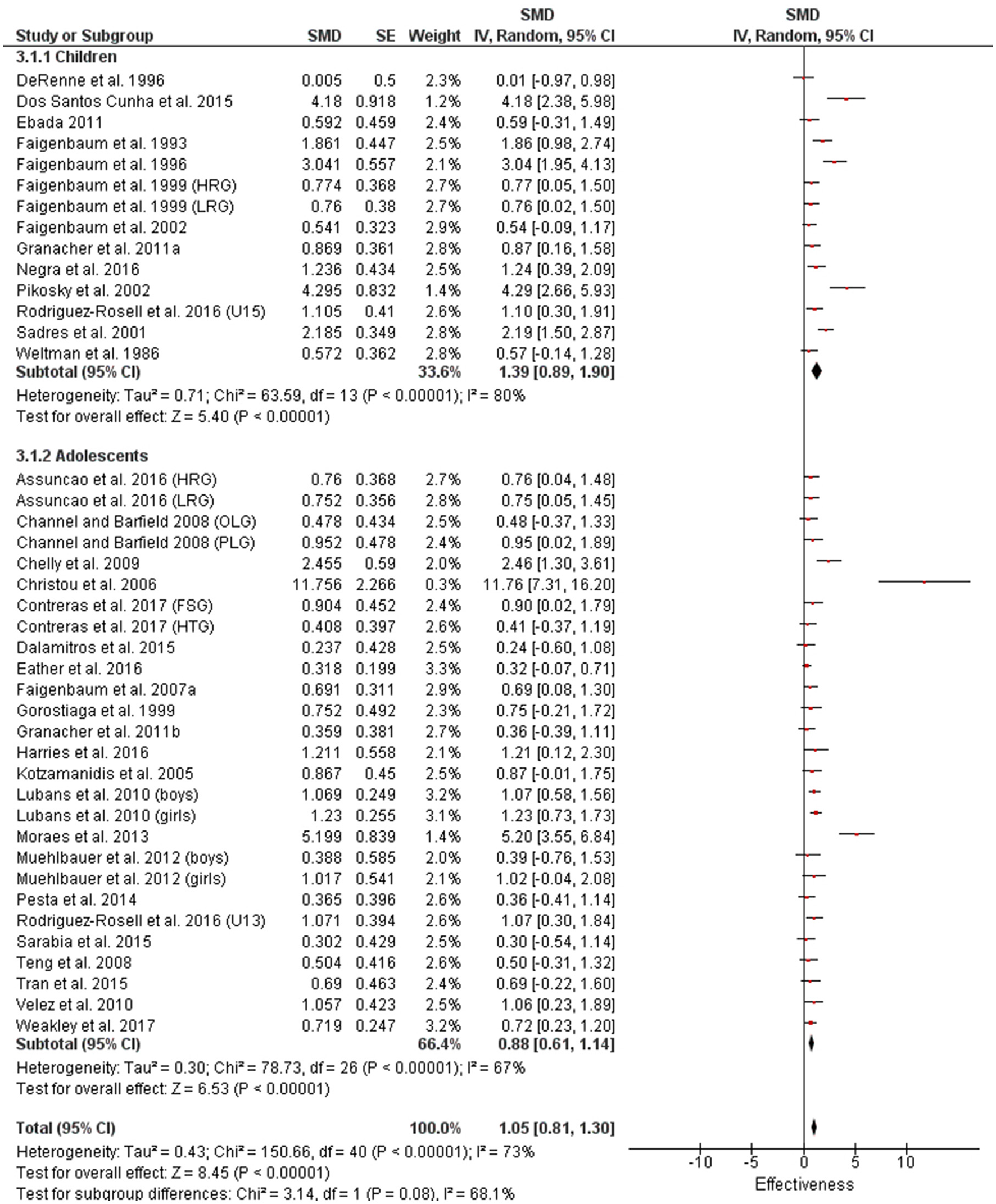

Table 3 shows that power (plyometric) training studies provided higher magnitude changes in jump performance than strength training studies. In terms of general descriptors, power training studies exceeded strength training studies with trained (moderate vs. small), untrained (large vs. moderate)(Figures 2, 4) and adolescent (moderate vs. small) populations (Figures 3, 5). For the overall or general results (Figures 2, 4) as well as with children (Figures 3, 5), the descriptive classifications were the same (moderate magnitude improvements), although the precise SMDs values were higher with power training. When comparing specific populations (power and strength training combined), untrained individuals (moderate to large magnitude) experienced greater jump height gains than trained participants (small to moderate). Similarly, with training groups combined, children experienced larger jump height gains than adolescents, although the descriptive classification only differed with strength training (moderate vs. small), but not power training.

Table 3

| General | Trained vs. | Untrained | Children vs. | Adolescents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power training effects on jump measures | 0.69 Moderate | 0.67 Moderate | 0.80 Large | 0.74 Moderate | 0.57 Moderate |

| Strength training effects on jump measures | 0.53 Moderate | 0.48 Small | 0.61 Moderate | 0.68 Moderate | 0.42 Small |

| Power training effects on sprint measures | 0.38 Small | 0.32 Small | 1.19 * Large | 0.47 Small | 0.13 Trivial |

| Strength training effects on sprint measures | 0.48 Small | 0.45 Small | 0.57 * Moderate | 0.73 Moderate | 0.36 Small |

| Power training effects on lower body strength measures | 0.16** Trivial | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 0.16** Trivial |

| Strength training effects on lower body strength measures | 1.14 Large | 1.23 Large | 1.08 Large | 1.39 Large | 0.88 Large |

Summary of meta-analysis results.

Shaded row values illustrate higher magnitude changes compared to the corresponding measure. Bolded values illustrate higher magnitude changes for untrained vs. trained participants. Bolded and underlined values indicate higher magnitude changes for children vs. adolescents.

3 studies met inclusion criteria;

4 studies met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 2

Power training effects on jump measures for trained and untrained subjects. Positive SMD values indicate performance changes from pre to post related to training effects, while negative SMDs are indicative of non-effective changes from pre to post. SMD, Standardized mean difference expresses the size of the intervention effect relative to the variability observed in that study. SE, Standard Error. Weight, proportional weight or contribution of each study to the overall analysis.

Figure 3

Power training effects on jump measures for children and adolescents. Positive SMD values indicate performance changes from pre to post related to training effects, while negative SMDs are indicative of non-effective changes from pre to post. SMD, Standardized mean difference expresses the size of the intervention effect relative to the variability observed in that study. SE, Standard Error. Weight, proportional weight or contribution of each study to the overall analysis.

Figure 4

Strength training effects on jump measures for trained and untrained subjects. Positive SMD values indicate performance changes from pre to post related to training effects, while negative SMDs are indicative of non-effective changes from pre to post. SMD, Standardized mean difference expresses the size of the intervention effect relative to the variability observed in that study. SE, Standard Error. Weight, proportional weight or contribution of each study to the overall analysis.

Figure 5

Strength training effects on jump measures for children and adolescents. Positive SMD values indicate performance changes from pre to post related to training effects, while negative SMDs are indicative of non-effective changes from pre to post. SMD, Standardized mean difference expresses the size of the intervention effect relative to the variability observed in that study. SE, Standard Error. Weight, proportional weight or contribution of each study to the overall analysis.

Sprint speed measures

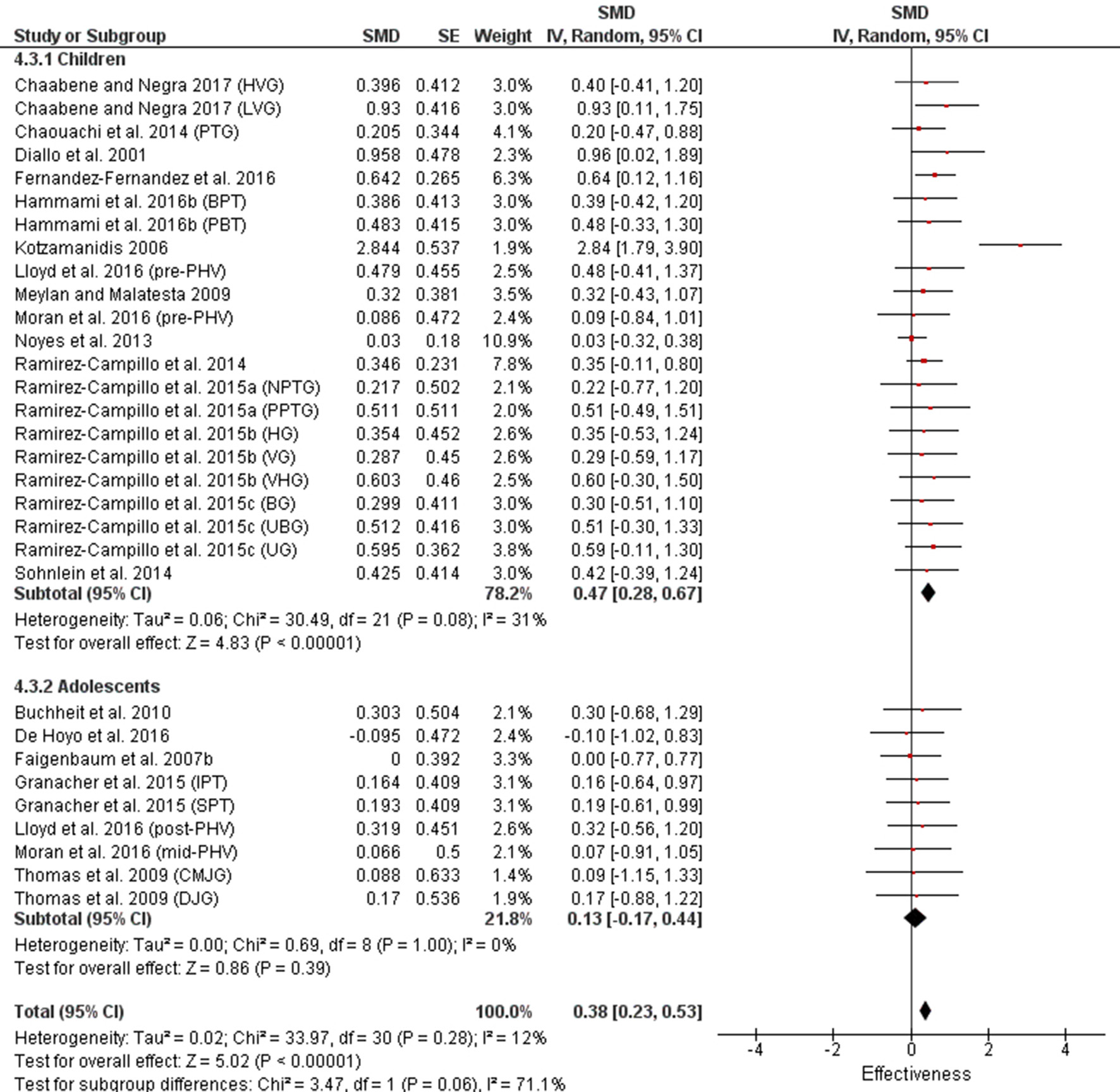

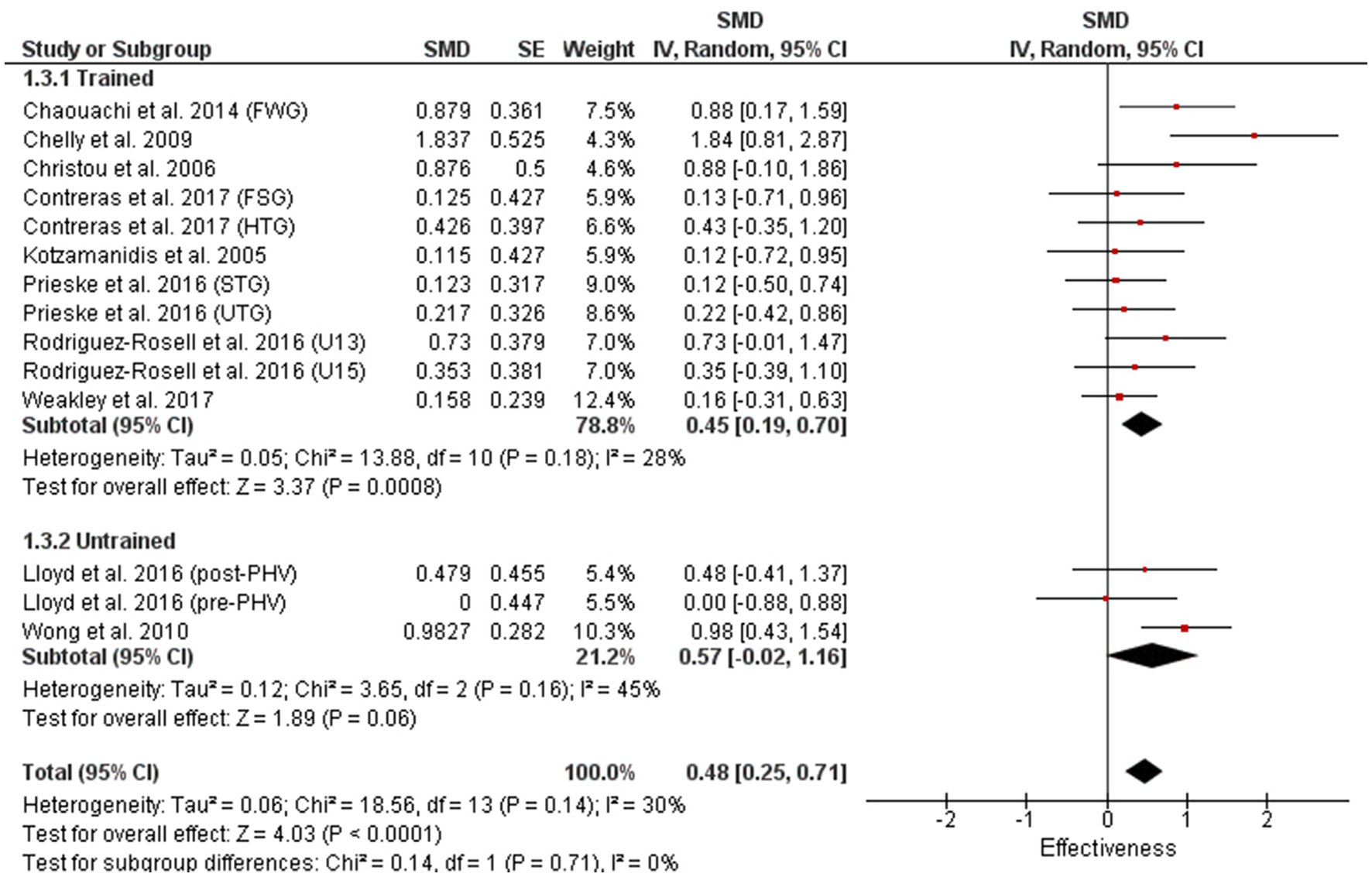

In contrast to power (jump) results, strength training studies tended to provide better sprint time results than power training (Table 2). However, it was only in the children and adolescent strength vs. power training comparison where the descriptive classifications for strength training exceeded power training with moderate vs. small and small vs. trivial classifications, respectively (Figures 7, 9). In contrast, power training (only 3 measures) provided a greater magnitude change than strength training (30 measures) with untrained populations demonstrating a large vs. moderate improvement in sprint time (Figures 6, 8). Again, similar to power (jump) measures, untrained and child populations had greater magnitudes and descriptors than trained and adolescents respectively for both strength and power training.

Figure 6

Power training effects on sprint measures for trained and untrained subjects. Positive SMD values indicate performance changes from pre to post related to training effects, while negative SMDs are indicative of non-effective changes from pre to post. SMD, Standardized mean difference expresses the size of the intervention effect relative to the variability observed in that study. SE, Standard Error. Weight, proportional weight or contribution of each study to the overall analysis.

Figure 7

Power training effects on sprint measures for children and adolescents. Positive SMD values indicate performance changes from pre to post related to training effects, while negative SMDs are indicative of non-effective changes from pre to post. SMD, Standardized mean difference expresses the size of the intervention effect relative to the variability observed in that study. SE, Standard Error. Weight, proportional weight or contribution of each study to the overall analysis.

Figure 8

Strength training effects on sprint measures for trained and untrained subjects. Positive SMD values indicate performance changes from pre to post related to training effects, while negative SMDs are indicative of non-effective changes from pre to post. SMD, Standardized mean difference expresses the size of the intervention effect relative to the variability observed in that study. SE, Standard Error. Weight, proportional weight or contribution of each study to the overall analysis.

Figure 9

Strength training effects on sprint performance for children and adolescents. Positive SMD values indicate performance changes from pre to post related to training effects, while negative SMDs are indicative of non-effective changes from pre to post. SMD, Standardized mean difference expresses the size of the intervention effect relative to the variability observed in that study. SE, Standard Error. Weight, proportional weight or contribution of each study to the overall analysis.

Muscle strength measures

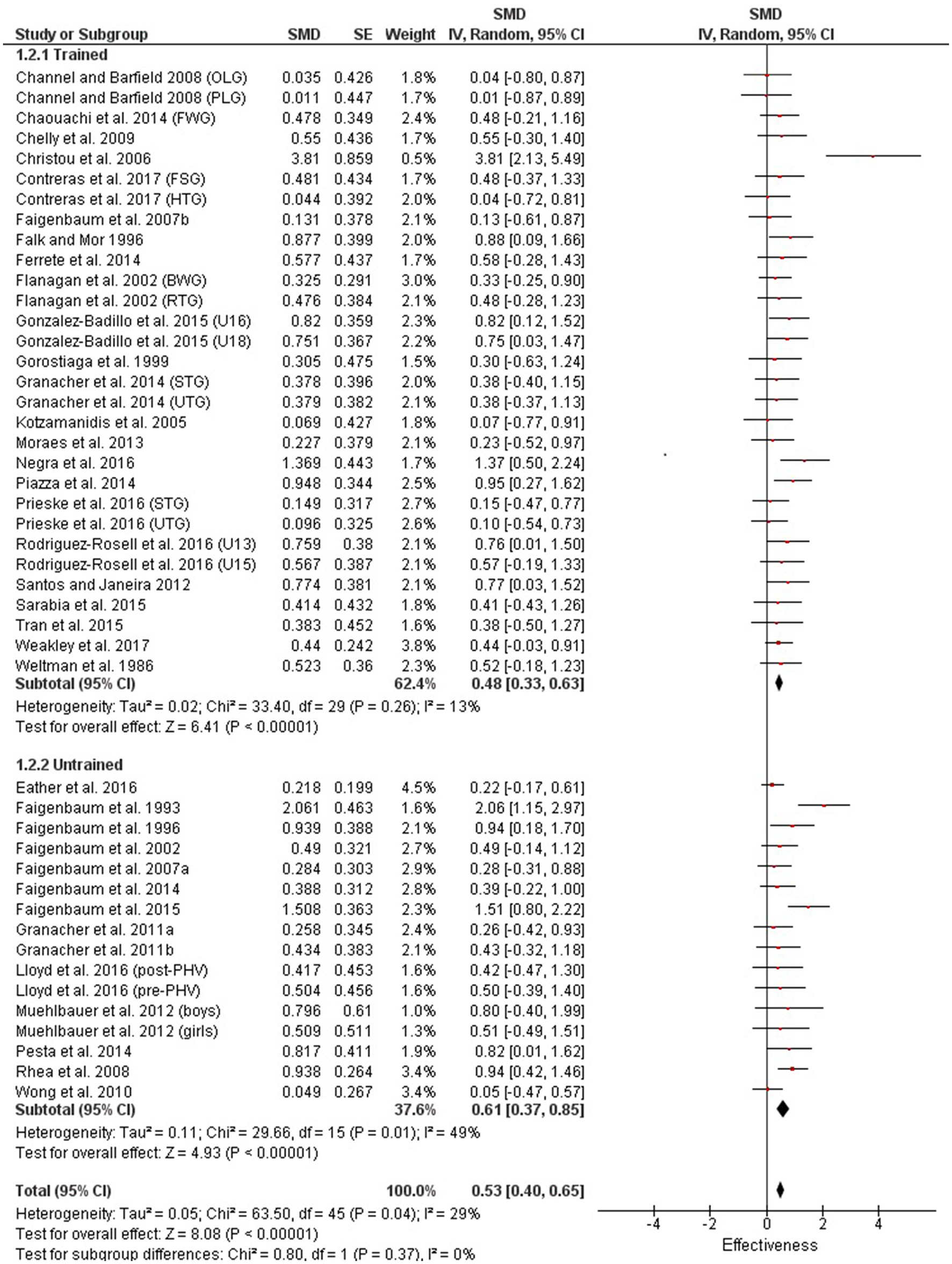

There were very few power training studies that measured lower body strength with no studies that utilized children or differentiated between trained and untrained individuals (Figure 10). The 4 power training measures within our review used adolescents with only a trivial magnitude improvement compared to large magnitude improvements in all categories (0.88–1.35) with the 45 strength training measures (Figures 11, 12).

Figure 10

Power training effects on lower body strength for adolescents only. Positive SMD values indicate performance changes from pre to post related to training effects, while negative SMDs are indicative of non-effective changes from pre to post. SMD, Standardized mean difference expresses the size of the intervention effect relative to the variability observed in that study. SE, Standard Error. Weight, proportional weight or contribution of each study to the overall analysis.

Figure 11

Strength training effects on lower body strength for trained and untrained subjects. Positive SMD values indicate performance changes from pre to post related to training effects, while negative SMDs are indicative of non-effective changes from pre to post. SMD, Standardized mean difference expresses the size of the intervention effect relative to the variability observed in that study. SE, Standard Error. Weight, proportional weight or contribution of each study to the overall analysis.

Figure 12

Strength training effects on lower body strength for children and adolescents. Positive SMD values indicate performance changes from pre to post related to training effects, while negative SMDs are indicative of non-effective changes from pre to post. SMD, Standardized mean difference expresses the size of the intervention effect relative to the variability observed in that study. SE, Standard Error. Weight, proportional weight or contribution of each study to the overall analysis.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that compared the effects of strength vs. power training on measures of muscle strength, power, and speed in trained and untrained youth. The most pertinent findings of the present study were the tendencies for training specificity with power measures (power training more effective than strength training), but a lack of training specificity with sprint measures (strength training more effective than power training) with youth. Thirdly, strength training exhibited uniformly large magnitude changes to lower body strength measures, which contrasted with the generally trivial, small and moderate magnitude training improvements of power training upon lower body strength, sprint and jump power measures, respectively. Furthermore, untrained youth displayed more substantial improvements in jump and sprint measures with both power and strength training compared to trained youth.

The greater magnitude improvements in power measures with power vs. strength training corresponds with the training specificity principle (Sale and MacDougall, 1981; Behm, 1988, 1995; Behm and Sale, 1993). Training specificity dictates that training adaptations are greater when the training mode, velocities, contraction types and other training characteristics most closely match the subsequent activity, sport or tests. The higher speed and power movements associated with power training would be expected to provide more optimal training adaptations for explosive type jump measures. Power training (e.g., plyometrics) can improve youth's ability to increase movement speed and power production (Behm et al., 2008). Chaouachi et al. (2014) reported similar findings when they compared training programs that involved two types of power training (Olympic weight lifting and plyometric) and traditional RT. In accordance with the present review and the concept of training specificity, both plyometric and Olympic weight lifting in the Chaouachi study provided greater magnitude improvements in CMJ than traditional RT.

It should be noted though, that while the numerical SMD values for power training exceeded strength training for power measures, the descriptor categorization overall was the same: moderate for both power and strength training. Thus, while it is conceded that power training demonstrates a numerical advantage over strength training for power measures (e.g., jump performance), the relative extent or degree of superiority was not overwhelming. The relative magnitude of improvement with power training (moderate to large: 0.6–0.8) for power measures (e.g., jumps) did not match the training specific extent or consistency of improvements associated with strength training on lower body strength (uniformly large: 0.88–1.35). Hence, the training specific response of strength training (strength training effects on strength measures) was consistently more substantial than the power training specific response (power training effects on jump power measures). Furthermore, power training specificity did not extend to another power and speed related measure: sprint speed.

Strength training magnitudes of change exceeded power training for sprint measures (exception of untrained participants). These findings contradict the long-held concept of training specificity (Sale and MacDougall, 1981; Behm, 1988, 1995; Behm and Sale, 1993). Slower, more deliberate movements of traditional RT would not be expected to provide optimal training adaptations for sprint measures that involve higher speed, stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) type activities. Again, similar findings were reported by Chaouachi et al. (2014) who found that traditional RT provided superior training adaptations compared to both Olympic weight lifting and plyometric training for 5 and 20 meter sprints. However, Radnor et al. (2017) reported contradictory results to the present meta-analysis with plyometric training and combined strength and plyometric training providing more positive responders than strength training alone for sprint velocity. The Radnor study incorporated school aged boys (not specifically trained) whereas the present review included both highly trained athletes and untrained youth. Similar to Radnor and colleagues, untrained youth in this meta-analysis participating in power training had greater magnitude improvements in sprint measures than trained athletes or the mean results of both populations.

One of the main factors contributing to optimal sprint performance is the capacity to generate a high rate of muscular force (Aagaard et al., 2002; Cronin and Sleivert, 2005; Cormie et al., 2007). Sprint actions employ stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) actions that involve the sequential combination of eccentric and concentric muscle contractions (Komi, 1986). SSC based actions tend to promote greater concentric force outputs when there is a rapid and efficient storage and transfer of elastic energy from the eccentric to the concentric phases (Cavagna et al., 1968; Bosco et al., 1982a,b; Cormie et al., 2010). Elastic and contractile (e.g., increased time for muscle activation, pre-load effect, muscle-tendon interaction, stretch reflexes) components affect maximal power output (Cavagna et al., 1968; Ettema et al., 1990; Lichtwark and Wilson, 2005; Avela et al., 2006). These mechanical and reflexive contributions occur over a short duration and thus the transition from eccentric to concentric phases must be brief (McCarthy et al., 2012). Reaction forces from sprints and hurdle jumps can generate reaction forces of ~4–6 times the individual's body mass (Mero et al., 1992; Cappa and Behm, 2011). Since the predominant jump measures were from bilateral CMJ and squat jumps, the ground reaction forces upon each limb would have been substantially lower (typically ½) than with high speed sprinting (with unilateral landings) (Dintiman and Ward, 2003; Cappa and Behm, 2011). The training specific related power (jump height) improvements seen with power training in this review would not necessitate similar eccentric strength capacities compared to the reaction forces experienced with sprinting. An individual who lacks sufficient eccentric strength must accommodate the eccentric forces by absorbing those forces over a longer time period, which would nullify the advantages of SSC actions (Miyaguchi and Demura, 2008). The lack of sprint training specificity with youth might be attributed to a lack of foundational eccentric (and likely concentric) strength. The effectiveness of traditional RT with youth sprinting would lie in its ability to build this essential strength component allowing youth to take advantage of the SSC mechanical and reflexive power amplification. Plyometric training would not be effective with any individual (youth or adult) who must absorb reaction forces over a prolonged period and thus cannot efficiently transfer the eccentric forces to the concentric power output.

The CMJ, drop, squat and other jumps evaluated in this meta-analysis all involved bilateral take-offs and landings. In contrast, sprinting is a series of rapid, unilateral landings and propulsions which would place greater challenges on the balance capabilities of the individual. Balance is another important contributor to SSC and sprint performance especially in youth (Hammami et al., 2016a). Balance affects force, power output and movement velocity (Anderson and Behm, 2005; Drinkwater et al., 2007; Behm et al., 2010a,b). Since balance and coordination are not fully mature in children (Payne and Isaacs, 2005), the effectiveness of plyometric training could be adversely affected. Hammami et al. (2016a) reported large-sized correlations between balance measures and proxies of power with youth (r = 0.511–0.827). These correlation coefficients were greatest with the more mature post-peak height velocity (PHV) youth, suggesting that the poorer postural control of the less mature pre-PHV and PHV youth had negative consequences upon power output. Similarly, significant positive correlations between maximum speed skating performance and a static wobble board balance test were reported in youth under 19 years of age (Behm et al., 2005). Thus, plyometric training activities are positively augmented with greater balance or postural control. For example, when 4 weeks of balance training was incorporated prior to 4 weeks of plyometric training the training outcomes were significantly better with youth than in the reverse order (Hammami et al., 2016b). Hence, the combination of inadequate strength and balance would inhibit positive sprint training adaptations associated with plyometric training with youth. In conflict with the training specificity principle, traditional RT may be more beneficial for promoting sprint adaptations in youth since it can build a foundation of strength upon which youth can take greater advantage of the SSC. Furthermore, the use of free weight or ground based strength/RT would be highly recommended for youth in order to emphasize initial balance adaptations (Behm et al., 2008, 2010a,b).

The only exception to the strength training advantage for sprint performance was with untrained participants with strength training providing moderate benefits (0.57) compared to large benefits (1.19) with plyometric training. However, upon closer inspection, there were only 3 measures each available for the untrained strength and plyometric training participants vs. 11 and 30 measures for the trained strength and plyometric trained participants, respectively. Hence, with such a sparsity of measures, one must be cautious about interpreting the robustness of this specific result for the untrained youth population.