Abstract

Background: A majority of high profile international sporting events, including the coming 2020 Tokyo Olympics, are held in warm and humid conditions. When exercising in the heat, the rapid rise of body core temperature (Tc) often results in an impairment of exercise capacity and performance. As such, heat mitigation strategies such as aerobic fitness (AF), heat acclimation/acclimatization (HA), pre-exercise cooling (PC) and fluid ingestion (FI) can be introduced to counteract the debilitating effects of heat strain. We performed a meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of these mitigation strategies using magnitude-based inferences.

Methods: A computer-based literature search was performed up to 24 July 2018 using the electronic databases: PubMed, SPORTDiscus and Google Scholar. After applying a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 118 studies were selected for evaluation. Each study was assessed according to the intervention's ability to lower Tc before exercise, attenuate the rise of Tc during exercise, extend Tc at the end of exercise and improve endurance. Weighted averages of Hedges' g were calculated for each strategy.

Results: PC (g = 1.01) was most effective in lowering Tc before exercise, followed by HA (g = 0.72), AF (g = 0.65), and FI (g = 0.11). FI (g = 0.70) was most effective in attenuating the rate of rise of Tc, followed by HA (g = 0.35), AF (g = −0.03) and PC (g = −0.46). In extending Tc at the end of exercise, AF (g = 1.11) was most influential, followed by HA (g = −0.28), PC (g = −0.29) and FI (g = −0.50). In combination, AF (g = 0.45) was most effective at favorably altering Tc, followed by HA (g = 0.42), PC (g = 0.11) and FI (g = 0.09). AF (1.01) was also found to be most effective in improving endurance, followed by HA (0.19), FI (−0.16) and PC (−0.20).

Conclusion: AF was found to be the most effective in terms of a strategy's ability to favorably alter Tc, followed by HA, PC and lastly, FI. Interestingly, a similar ranking was observed in improving endurance, with AF being the most effective, followed by HA, FI, and PC. Knowledge gained from this meta-analysis will be useful in allowing athletes, coaches and sport scientists to make informed decisions when employing heat mitigation strategies during competitions in hot environments.

Introduction

Exercising in the heat often results in elevation in body core temperature (Tc). This is the cumulative result of more heat being produced by the working muscles than heat loss to the environment coupled with hot and/or humid environmental conditions (Berggren and Hohwu Christensen, 1950; Saltin and Hermansen, 1966). Studies have shown that an accelerated increase in Tc could impair both exercise performance (i.e. time trial) and exercise capacity (i.e., time to exhaustion) (Galloway and Maughan, 1997; Parkin et al., 1999). In ambient temperatures of 4°, 11°, 21°, and 31°C, a compromise in endurance capacity due to thermoregulatory stress was already evident at 21°C (Galloway and Maughan, 1997). Parkin et al. (1999) found that time to exhaustion was longest when cycling in ambient temperatures of 3°C (85 min), followed by 20°C (60 min) and 40°C (30 min).

Elite athletes, however, cannot avoid competing in the heat since a majority of high-profile international sporting events are often held in warm conditions. The 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing was held in average ambient conditions of 25°C with 81% relative humidity. Similarly, the 2010 Youth Olympic Games in Singapore had temperatures reaching 31°C with relative humidity between 80 and 90%. The upcoming 2020 Olympics held in Tokyo's hot and humid summer period could potentially expose athletes to one of the most challenging environmental conditions observed in the modern history of the Olympic Games, with temperatures upwards of 35°C and above 60% relative humidity. Therefore, athletes have to learn to adapt and perform in these unfavorable environments and whenever possible, incorporate mitigation strategies to counter the negative effects of heat strain to augment performance and health.

Exercise tolerance in the heat can be affected by multiple factors such as the attainment of a critically high Tc (Gonzalez-Alonso et al., 1999b), cardiovascular insufficiency (Gonzalez-Alonso and Calbet, 2003), metabolic disturbances (Febbraio et al., 1994b, 1996; Parkin et al., 1999) and reductions in central nervous system drive to skeletal muscle (Nybo and Nielsen, 2001; Todd et al., 2005). Indeed, a high Tc represents one of the key limiting factors to exercise tolerance in the heat. The development of hyperthermia has been associated with alterations in self-pacing strategies in exercise performance trials or earlier voluntary termination during exercise capacity trials (Nielsen et al., 1993; Gonzalez-Alonso et al., 1999a,b).

In order to optimize exercise tolerance in the heat, exercising individuals often employ strategies to alter Tc. There are various ways in which this can be done, such as aerobic fitness (AF) (Nadel et al., 1974; Cheung and McLellan, 1998b), heat acclimation/acclimatization (HA) (Nielsen et al., 1993; Cotter et al., 1997), pre-exercise cooling (PC) (Gonzalez-Alonso et al., 1999a,b; Cotter et al., 2001) and fluid ingestion (FI) (Greenleaf and Castle, 1971; McConell et al., 1997). These strategies have shown to be effective in improving exercise tolerance in warm conditions through various processes that include alterations in heat dissipation ability, cardiovascular stability and adaptations and changes to the body's heat storage capacity.

Being able to objectively rank these heat mitigation strategies in order of their efficacy will be particularly useful for an athlete preparing to compete in the heat. This knowledge will also be beneficial for coaches, fitness trainers and backroom staff to discern when they consider heat mitigation in warm, humid conditions. With limited amount of time and resources, an evidence-based approach to quantify the efficacy of various heat mitigation strategies will allow selection of the most effective strategy to optimize performance and health and determine the priority in which these strategies should be employed. Furthermore, no comparison of the effect of different heat mitigation strategies have been presented using a meta-analysis thus far.

Therefore, the purpose of this review was to objectively evaluate the efficacy of various heat mitigation strategies using Hedges' g. Each study was analyzed in terms of the degree to which (i) Tc was lowered at the start of exercise; (ii) the rise of Tc is attenuated; (iii) Tc is extended at the end of exercise to safe limits (McLellan and Daanen, 2012) and (iv) endurance are improved. The weighted averages of Hedges' g (Hopkins et al., 2009) were then calculated, and the various heat mitigation strategies ranked in order of effectiveness in terms of both affecting Tc measurements and endurance.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

A computer-based literature search was performed using the following electronic databases: PubMed, SPORTDiscus and Google Scholar. The electronic database was searched with the following keywords: “fitness,” “training,” “heat acclimation,” “heat acclimatization,” “precooling,” “pre-cooling,” “cold water immersion,” “cold air,” “cold room,” “cold vest,” “cold jacket,” “ice vest,” “cold fluid,” “cold beverage,” “neck collar,” “neck cooling,” “ice slurry,” “ice slush,” “fluid ingestion,” “fluid intake,” “water ingestion,” “water intake,” “fluid replacement,” “rehydration,” “thermoregulation,” “core temperature,” and “heat mitigation.” Searches were systematically performed by combining the keywords and using Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” to yield the maximum outcome of relevant studies. Where applicable, we applied filters for language (English) and species (Human). In addition, a manual citation tracking of relevant studies and review articles was performed. The last day of the literature search was 24 July 2018.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were screened and included if they met the following criteria: (i) they investigated the effect of a heat mitigation strategy on Tc in an exercise context; (ii) they were conducted in warm or hot ambient conditions of more than 20°C; and (iii) they included a control condition or a pre-intervention and post-intervention assessment. Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: (i) they reported the use of pharmacological agents to alter Tc due to ethical issues and dangers involved with its use; (ii) they were review articles, abstracts, case studies and editorials; (iii) they involved combined use of different methods; and (iv) they involved children or the elderly.

Data Extraction

The following data were extracted: participant characteristics, sample size, ambient conditions, exercise protocol, intervention method, exercise outcome and Tc measurements. Tc measurements included the type of Tc measure used, Tc at the beginning of exercise, rate of rise of Tc and Tc at the end of exercise. In studies where mean and standard deviation of Tc were not reported in the text, the relevant data was extracted using GetData Graph Digitiser (http://getdata-graph-digitizer.com). In the event that pertinent data were not available, the corresponding authors of the manuscripts were contacted. Studies with missing data that could not be retrieved or provided by the author were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Data Analysis

In the event that rate of rise of Tc was not provided in the study, it was calculated as the difference between the Tc at the end of exercise and Tc at the beginning of exercise divided by the time taken to complete the task. When studies only reported standard errors, standard deviations were calculated by multiplying the standard error by the square root of the sample size.

Standardized mean differences (Hedges' g) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also calculated for each study. This was derived using the mean Tc differences divided by the pooled standard deviation either between the control and intervention groups or between the pre-intervention and post-intervention states. A bias-corrected formula for Hedges' g for all studies was used to correct for positive and small sample bias (Borenstein et al., 2009). Weighted average of Hedges' g for each heat mitigation strategy was calculated and presented in a forest plot. A combined weighted average of Hedges' g values across all three phases for each strategy's effect on altering Tc and on endurance was also calculated, and used as the basis for ranking. The magnitude of the Hedges' g-values were interpreted as follows: < 0.20, trivial; 0.20–0.49, small; 0.50–0.79, moderate; and ≥0.80, large.

Results

Search Results

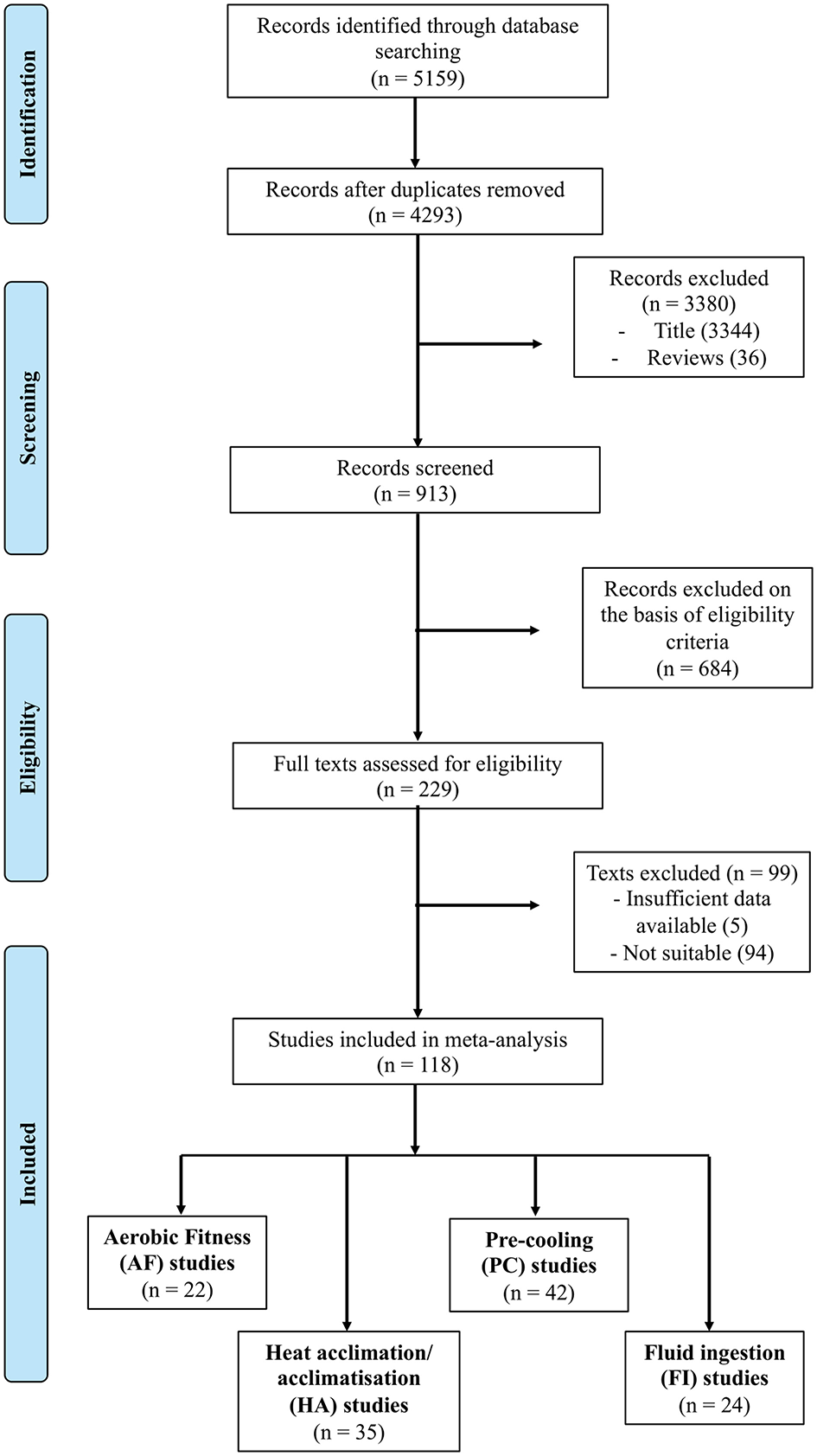

The initial identification process yielded 5159 references and after removing duplicates and screening for title and abstract, 229 full texts were obtained. Of these, based on the assessment of study relevance and the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 118 were found to be relevant and therefore included in the analysis. The number of studies found for each heat mitigation strategy is as follows: AF (n = 22), HA (n = 35), PC (n = 42), and FI (n = 24) (Figure 1). It should be noted that AF studies may incorporate effects of HA due to the environmental conditions that the AF studies are carried out in. To separate these effects, training periods for “within subjects” AF studies included were conducted at temperatures of 30°C and below. No separation based on temperature was determined for “between subjects” studies as no training was carried out for the subjects prior to the exercise test. Characteristics of the selected studies are summarized in Tables 1–4.

Figure 1

Flowchart of the study selection process.

Table 1

| Study | Ambient conditions | N = | Exercise protocol | Intervention method | Exercise outcome | Tc measure | Tc before | Tc rate of rise | Tc end |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mora-Rodriguez et al., 2010 | 36°C 25% RH 2.5 m/s airflow | 10 untrained 10 trained | EPW: Cycle at 40, 60 or 80% VO2 peak, equaled by total work | – | – | Tre | Utr: 37.6 ± 0.2°C Tr: 37.4 ± 0.2°C (S) | – | – |

| Ichinose et al., 2005 | 30°C 50% RH | 9 | EPW: 20 min cycle at pretraining 70% VO2 peak under isosmotic conditions | Cycle at 60% VO2 peak at 30°C, 50% RH for 1 hr/day for 10 days | – | Toes | Before: 36.68 ± 0.15°C After: 36.53 ± 0.18°C (S) | Before: 5.31 ± 1.17°C/h After: 4.74 ± 0.97°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Selkirk and McLellan, 2001 | 40°C 30% RH < 0.1 m/s wind speed | 6 untrained (low BF) 6 untrained (high BF) 6 trained (low BF) 6 trained (high BF) | EC: Treadmill walking at 3.5 km/h to exhaustion | – | Longer exercise times in Trlow vs Utrlow and Trlow vs. Trhigh (S) | Tre | Utrlow: 37.19 ± 0.20°C Trlow: 37.02 ± 0.20°C Utrhigh: 37.26 ± 0.37°C Trhigh: 37.10 ± 0.22°C (NS) | Utrlow: 1.20 ± 0.34°C/h Trlow: 1.27 ± 0.10°C/h Utrhigh: 1.24 ± 0.19°C/h Trhigh: 1.55 ± 0.15°C/h (CAL) | Utrlow: 38.58 ± 0.47°C Trlow: 39.48 ± 0.02°C Utrhigh: 38.78 ± 0.59°C Trhigh: 39.22 ± 0.22°C (S) |

| Periard et al., 2012 | 40°C 50% RH 4.1 m/s convective airflow | 8 untrained 8 trained | EC: Cycle to exhaustion at 60 & 75% VO2 max | – | No influence on times to exhaustion | Tre | UtrH60%: 37.0 ± 0.3°C TrH60%: 36.9 ± 0.2°C UtrH75%: 37.1 ± 0.3°C TrH75%: 36.8 ± 0.3°C (REQ) | – | UtrH60%: 39.4 ± 0.4°C TrH60%: 39.8 ± 0.3°C UtrH75%: 38.8 ± 0.5°C TrH75%: 39.3 ± 0.6°C (NS) |

| Cheung and McLellan, 1998a | 40°C 30% RH < 0.1 m/s wind speed | 7 moderately fit 8 highly fit | EC: Treadmill exercise at 3.5 km/h, 0% grade in a euhydrated state to exhaustion | – | No influence on tolerance time | Tre | MF: 36.93 ± 0.27°C HF: 36.85 ± 0.22°C (NS) | MF: 1.14 ± 0.29°C/h HF: 1.21 ± 0.27°C/h (CAL) | MF: 38.77 ± 0.27°C HF: 39.15 ± 0.18°C (NS) |

| Ichinose et al., 2009 | 25°C 45% RH | 11 | EPW: Cycle at 50% VO2 max for 30 min | Cycle at 60% VO2 max for 60 min/day, 4–5 days/week over 3 menstrual cycles at 30°C, 45% RH | – | Toes | Before: 37.27 ± 0.33°C After: 37.07 ± 0.20°C (S) | Before: 0.68 ± 0.81°C/h After: 0.80 ± 0.52°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Cheung and McLellan, 1998b | 40°C 30% RH < 0.1 m/s wind speed | 8 | EC: Treadmill heat stress test in a euhydrated state to exhaustion | Treadmill walk for 1 h, 6 days/week at 60–65% VO2 max for 2 weeks in a normothermic environment | No influence on tolerance time | Tre | Before: 37.08 ± 0.24°C After: 36.93 ± 0.34°C (NS) | Before: 1.04 ± 0.34°C/h After: 1.07 ± 0.30°C/h (CAL) | Before: 38.70 ± 0.37°C After: 38.61 ± 0.25°C (NS) |

| Wright et al., 2012 | 40°C 30% RH < 0.1 m/s wind speed | 11 untrained 12 trained | EC: Treadmill walk at 4.5 km/h, 2% incline to exhaustion | – | Longer time to exhaustion (S) | Tre | – | Utr: 1.25 ± 0.20°C/h Tr: 1.14 ± 0.28°C/h (NS) | Utr: 39.0 ± 0.3°C Tr: 39.7 ± 0.3°C (S) |

| Takeno et al., 2001 | 30°C 50% RH | 5 | EPW: 30 min cycle at 60% VO2 peak | Cycle at 60% VO2 peak for 60 min/day, 5 days/week for 2 weeks at atmospheric pressure | – | Toes | Before: 37.0 ± 0.2°C After: 36.8 ± 0.2°C (S) | Before: 2.6 ± 1.0°C/h After: 2.6 ± 0.6°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Stapleton et al., 2010 | 30°C 15% RH | 10 | EPW: 60 min cycle at a constant rate of heat production | Aerobic and resistance training for 8 weeks | – | Toes | Before: 37.10 ± 0.28°C After: 36.95 ± 0.24°C (S) | Before: 0.68 ± 1.8°C/h After: 0.56 ± 0.16°C/h (S) | – |

| Lim et al., 2009 | 35°C 40% RH | 9 normal training 9 increased training | EC: Treadmill run at 70% VO2 max to exhaustion | NT: Routine training program for 14 daysIT: 20% increase in training load for 14 days | – | Tgi | BeforeNT: 36.68 ± 0.32°C AfterNT: 36.70 ± 0.41°C BeforeIT: 36.98 ± 0.46°C AfterIT: 37.11 ± 0.39°C (NS) | BeforeNT: 3.48 ± 0.96°C/h AfterNT: 2.88 ± 1.14°C/h BeforeIT: 3.42 ± 1.20°C/h AfterIT: 3.48 ± 1.26°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Ho et al., 1997 | 36°C 20% RH | 6 young sedentary 6 young fit | EPW: 20 min cycle at 35% VO2 peak | – | – | Toes | Sedentary: 37.1 ± 0.2°C Fit: 36.9 ± 0.2°C (NS) | – | – |

| Shvartz et al., 1977 | 23°C dry bulb 16°C wet bulb < 0.2 m/s wind speed | 7 untrained 7 trained | EPW: 60 min bench stepping at 41 W | – | – | Tre | Utr: 36.9 ± 0.19°C Tr: 37.1 ± 0.31°C (NS) | Utr: 1.0 ± 0.37°C/h Tr: 1.0 ± 0.42°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Cramer et al., 2012 | 24.5°C 0.9 kPa RH 1.3 m/s air velocity | 10 unfit 11 fit | EPW: 60 min cycle at 60% VO2 max or to produce metabolic heat of 275 W/m2 | – | – | Tre | Unfit60%: 37.40 ± 0.22°C Fit60%: 37.09 ± 0.20°C UnfitBAL: 37.43 ± 0.25°C FitBAL: 37.14 ± 0.23°C(S) | UnfitBAL: 0.93 ± 0.40°C/h FitBAL: 0.95 ± 0.33°C/h (CAL) | - |

| Shvartz et al., 1974 | 21.5°C dry bulb 17.5°C wet bulb | 5 | EPW: 60 min bench-stepping at 85% VO2 max | Bench-stepping for 60 min/day for 12 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.4 ± 0.3°C After: 37.2 ± 0.2°C (S) | – | – |

| Ikegawa et al., 2011 | 30°C 50% RH | 7 | EPW: 30 min cycle at 65% VO2 peak in a euhydrated state | Cycle for 30 min/day for 5 days | – | Toes | Before: 36.74 ± 0.32°C After: 36.50 ± 0.16°C (S) | Before: 3.18 ± 0.83°C/h After: 3.06 ± 0.49°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Yamauchi et al., 1997 | 23°C 60% RH | 5 untrained 6 trained | EPW: 30 min cycle at 80 W | – | – | Ttym | Utr: 36.71 ± 0.22°C Tr: 36.50 ± 0.15°C (NS) | – | – |

| Yamazaki et al., 1994 | 25°C 35% RH | 8 untrained 9 trained | EPW: 30 min cycle at 35% VO2 max | – | – | Toes | Utr: 37.06 ± 0.30°C Tr: 37.02 ± 0.23°C (NS) | – | – |

| Gagnon et al., 2012 | 42°C 20% RH 1 m/s air speed | 8 untrained 8 trained | EPW: 120 min cycle at 120 W with fluid replacement | – | – | Toes | Utr: 36.96 ± 0.25°C Tr: 36.69 ± 0.25°C (NS) | Utr: 0.68 ± 0.30°C/h Tr: 0.82 ± 0.34°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Merry et al., 2010 | 24.3°C 50% RH 4.5 m/s wind velocity | 6 untrained 6 trained | EPW: 40 min cycle at 70% VO2 peak in a euhydrated state | – | – | Trec | Utr: 36.88 ± 0.26°C Tr: 36.56 ± 0.29°C (REQ) | – | – |

| Shields et al., 2004 | 32°C 32% RH | 7 | EPW: 45 min cycling at 40% VO2 peak | Exercise at 50% VO2 reserve for 40 min/day for 3 days per week, over 12 weeks | – | Toes | Before: 37.00 ± 0.27°C After: 36.88 ± 0.25°C (REQ) | Before: 0.69 ± 0.65°C/h After: 0.64 ± 0.89°C/h (REQ) | – |

| Smoljanic et al., 2014 | 25°C 37% RH | 7 fit 7 unfit | EPW: Run for 60 min at 60% VO2max, followed by run at fixed metabolic heat production of 640 W | – | – | Tre | – | Fit60minrun: 1.23 ± 0.37°C/h Unfit60minrun: 0.90 ± 0.30°C/h (S) Fitfixedmetheatprod: 0.86 ± 0.26°C/h Unfitfixedmetheatprod: 0.92 ± 0.32°C/h (NS) | – |

Summary of aerobic fitness studies.

RH, relative humidity; EC, exercise capacity; EP, exercise performance; EPW, exercise performance at a fixed workload; S, significant; NS, not significant; CAL, calculated values; REQ, requested values; Tre, rectal temperature; Toes, oesophageal temperature; Tgi, gastrointestinal temperature; Ttym, tympanic temperature; Utr, untrained subjects; Tr, trained subjects; BF, body fat; NT, normal training; IT, increased training; MF, moderately fit subjects; HF, highly fit subjects; AF, aerobic fitness.

Table 2

| Study | Ambient conditions | N = | Exercise protocol | Intervention method | Exercise outcome | Tc measure | Tc before | Tc rate of rise | Tc end |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOW HUMIDITY (<50% RH) | |||||||||

| Lorenzo and Minson, 2010 | 38°C 30% RH | 12 | EP: 1 h cycling time trial | Two 45 min exposures to 40°C, 30% RH conditions for 10 days | Higher power output (S) | Tre | Before: 37.1 ± 0.3°C After: 37.0 ± 0.4°C (REQ) | – | Before: 39.5 ± 0.3°C After: 39.4 ± 0.7°C (NS) |

| Cheung and McLellan, 1998a | 40°C 30% RH < 0.1 m/s wind speed | 7 moderately fit 8 highly fit | EC: Treadmill walk at 3.5 km/h, 0% grade in a euhydrated state to exhaustion | 1 h exposures to 40°C, 30% RH conditions for 5 days/week for 2 weeks | No influence on tolerance time | Tre | BeforeMF: 36.93 ± 0.27°C AfterMF: 36.96 ± 0.28°C BeforeHF: 36.85 ± 0.22°C AfterHF: 36.74 ± 0.19°C (NS) | BeforeMF: 1.14 ± 0.29°C/h AfterMF: 1.08 ± 0.25°C/h BeforeHF: 1.21 ± 0.27°C/h AfterHF: 1.25 ± 0.20°C/h (CAL) | BeforeMF: 38.77 ±0.27°C AfterMF: 38.79 ± 0.31°C BeforeHF: 39.15 ± 0.18°C AfterHF: 39.14 ± 0.21°C (NS) |

| Nielsen et al., 1993 | 40°C 10% RH | 8 | EC: Cycling at approximately 50% VO2 max to exhaustion | 90 min exposures to 40°C, 10% RH conditions for 9–12 days | Increase in endurance time (S) | Toes | – | – | Before: 39.8 ± 0.4°C After: 39.7 ± 0.4°C (NS) |

| Horstman and Christensen, 1982 | 45°C dry bulb 23°C wet bulb | 6 men 4 women | EPW: 120 min cycle at 40% VO2 max | 2 h exposures to 45°C dry bulb, 23°C wet bulb conditions for 11 days | – | Tre | – | Beforemen: 1.5 ± 0.5°C/h Aftermen: 0.8 ± 0.2°C/h (NS) Beforewomen: 1.4 ± 0.4°C/h Afterwomen: 0.5 ± 0.0°C/h (S) | – |

| Weller et al., 2007 | 46.1°C dry bulb 17.9% RH | 8 in RA12 8 in RA26 | EPW: 60 min treadmill walk at 45% VO2 peak | 100 min exposures to 46.1°C, 17.9% RH conditions for 10 days | – | Tre | Before12: 37.20 ± 0.27°C After12: 36.95 ± 0.22°C Before26: 37.27 ± 0.15°C After12: 37.00 ± 0.13°C (S) | Before12: 1.39 ± 0.41°C/h After12: 1.17 ± 0.37°C/h Before26: 1.42 ± 0.28°C/h After12: 1.16 ± 0.21°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Shvartz et al., 1977 | 23°C dry bulb16°C wet bulb < 0.2 m/s wind speed | 7 untrained 7 trained | EPW: 60 min bench stepping at 41 W | 3 h exposures to 39.4°C dry bulb, 30.3°C wet bulb conditions for 8 days | – | Tre | BeforeUtr: 37.1 ± 0.31°C AfterUtr: 36.7 ± 0.20°C BeforeTr: 36.9 ± 0.19°C AfterTr: 36.7 ± 0.13°C (S) | BeforeUtr: 1.0 ± 0.37°C/h AfterUtr: 1.0 ± 0.27°C/h BeforeTr: 1.0 ± 0.42°C/h AfterTr: 0.9 ± 0.21°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Febbraio et al., 1994a | 40°C 20% RH | 13 | EPW: 40 min cycle at 70% VO2 max | 90 min exposures to 40°C, 20% RH conditions for 7 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.2 ± 0.4°C After: 36.8 ± 0.4°C (NS) | Before: 3.8 ± 0.8°C/h After: 3.6 ± 0.8°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Beaudin et al., 2009 | 24°C 30% RH | 8 | EC: Incremental cycling to exhaustion | 2 h passive exposures to 50°C, 20% RH conditions for 10 days | – | Toes | Before: 37.57 ± 0.23°C After: 37.32 ± 0.14°C (S) | – | – |

| Magalhaes Fde et al., 2006 | 40°C 32% RH | 6 | EPW: 60 min cycle at 50% VO2 peak | 1 h exposures to 40°C, 32% RH conditions for 9 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.2 ± 0.2°C After: 37.0 ± 0.2°C (S) | Before: 0.94 ± 0.16°C/h After: 0.88 ± 0.27°C/h (NS) | – |

| Armstrong et al., 1985 | 40.1°C 23.5% RH | 9 | EPW: 90 min treadmill walk at 5.6 km/h, 6% grade with a high or low sodium diet | 90 min exposures to 40.1°C, 23.4% RH conditions for 8 days | – | Tre | Beforelow: 37.44 ± 0.66°C Afterlow: 37.05 ± 0.30°C (S) Beforehigh: 37.25 ± 0.72°C Afterhigh: 36.97 ± 0.45°C (NS) | Beforelow: 0.85 ± 0.48°C/h Afterlow: 0.74 ± 0.26°C/h Beforehigh: 0.93 ± 0.59°C/h Afterhigh: 0.79 ± 0.36°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Watkins et al., 2008 | 39.5°C 27% RH | 10 | EPW: 30 min cycle at 75% VO2 peak | 30 min exposures to 39.5°C27% RH conditions for 7 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.2 ± 0.2°C After: 37.0 ± 0.2°C (S) | Before: 1.8 ± 0.9°C/h After: 1.8 ± 0.5°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Burk et al., 2012 | 42°C 18% RH | 21 | EC: Treadmill walk at 60% VO2 peak to exhaustion | Two 50 min exposures to 42°C, 18% RH conditions for 10 days | Increase in endurance time (S) | Tre | Before: 37.2 ± 0.2°C After: 37.0 ± 0.2°C (S) | Before: 1.7 ± 0.4°C/h After: 1.0 ± 0.3°C/h (CAL) | Before: 39.7 ± 0.4°C After: 39.7 ± 0.4°C (NS) |

| Hodge et al., 2013 | 35.3°C 40.2% RH | 8 | EPW: 90 min treadmill walk at 40% VO2 max | 90 min exposures to 35.3°C, 40.2% RH conditions for 8 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.1 ± 0.3°C After: 36.8 ± 0.4°C(REQ) | Before: 1.8 ± 0.3°C/h After: 0.7 ± 0.4°C/h (REQ) | – |

| Magalhaes Fde et al., 2010 | 40°C 45% RH | 9 | EPW: 90 min treadmill run at 50% maximal power output | 90 min exposures to 40°C, 45% RH conditions for 11 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.43 ± 0.17°C After: 37.26 ± 0.18°C (REQ) | Before: 1.05 ± 0.29°C/h After: 1.03 ± 0.23°C/h (REQ) | – |

| Racinais et al., 2012 | 44°C 44% RH | 18 | EPW: 30 min treadmill walk at 5 km/h, 1% grade | Football training in 38–43°C, 12–30% RH conditions for 6 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.37 ± 0.17°C After: 37.26 ± 0.23°C (REQ) | Before: 1.18 ± 0.51°C/h After: 1.24 ± 0.62°C/h (REQ) | – |

| Best et al., 2014 | 35°C 40% RH | 7 | EPW: 60 min cycle at 70% VO2max | 60 min cycling at 70% VO2max in 35°Cm, 40% conditions for 6 days | – | Tre | – | – | Before: 39.1 ± 0.3°C After: 38.7 ± 0.3°C (S) (Graph) |

| Dileo et al., 2016 | 45°C 20% RH | 10 | EC: Ramped running protocol until volitional fatigue | 2 × 45 min periods cycling at 50% VO2max in 45°C, 20% RH conditions for 5 days | – | Tre | Before: 36.9 ± 0.2°C After: 36.7 ± 0.2°C (NS) (Graph) | – | Before: 38.9 ± 0.6°C After: 38.7 ± 0.4°C (S) |

| Flouris et al., 2014 | 40°C 20% RH | 10 | EPW: Cycle at fixed rates of metabolic heat production equal to 300, 350 and 400 W/m2, for 30 min each | 90 min cycling at 50% VO2peak in 40°C, 20% RH for 14 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.0 ± 0.2 °C After: 36.7 ± 0.1°C (S) (Graph) | – | – |

| Gibson et al., 2015 | 40°C 28% RH | 24 | EPW: 30 min running at 9 km/h and 2% elevation | FIXED protocol: 90 min of cycling at 50% VO2peak in 40°C, 39% RH ISOCONT: Cycle at 65% VO2peak until Tre of 38.5°C reached ISOPROG: Cycle at 65% VO2peak until Tre of 38.5°C reached for first 5 days, (then until 39°C for last 5 days). STHA – Protocol above for 5 days LTHA – Protocol above for 10 days | – | Tre | Before (FIXED): 37.2 ± 0.4°C Before (ISOCONT): 37.1 ± 0.2°C Before (ISOPROG): 36.9 ± 0.4°C STHA - Before (FIXED): 36.9 ± 0.4°C Before (ISOCONT): 37.0 ± 0.2°C Bssefore (ISOPROG): 36.7 ± 0.4°C (S) LTHA - Before (FIXED): 36.9 ± 0.4°C Before (ISOCONT): 37.0 ± 0.2°C Before (ISOPROG): 36.8 ± 0.3°C (S) | Before (FIXED): 2.35 ± 0.87°C/h Before (ISOCONT): 3.21 ± 0.6°C/h Before (ISOPROG): 2.97 ± 0.4°C/h STHA – After (FIXED): 2.49 ± 1.13°C/h After (ISOCONT): 2.77 ± 0.71°C/h After (ISOPROG): 2.87 ± 0.49°C/h LTHA - After (FIXED): 2.39 ± 0.94°C/h After (ISOCONT): 2.56 ± 0.75°C/h After (ISOPROG): 2.82 ± 0.78°C/h | – |

| Racinais et al., 2015b | 34°C 18% RH | 9 | EP: 43.3 km cycling time trial | 4 h exposures to 34°C, 18% RH conditions for 2 weeks | Faster time trial (S) | Tre | – | – | Before: 40.2 ± 0.4°C After: 40.1 ± 0.4°C |

| HIGH HUMIDITY (>50% RH) | |||||||||

| Cotter et al., 1997 | 39.5°C 59.2% RH | 8 | EPW: 70 min cycle at 50% peak aerobic power | 70 min exposures to 39.5°C, 59.2% RH conditions for 6 days | – | Tac | Before: 36.83 ± 0.05°C After: 36.62 ± 0.05°C (S) | – | – |

| Fujii et al., 2012 | 37°C 50% RH < 0.2 m/s wind speed | 10 | EPW: 75 min cycle at 58% VO2 peak | Four 20 min exposures to 37°C conditions for 6 days | – | Toes | Before: 36.6 ± 0.1°C After: 36.4 ± 0.2°C (S) | – | – |

| Buono et al., 1998 | 35°C 75% RH | 9 | EPW: 2 h exercise bouts of either a treadmill walk at 1.34 m/s, 3% grade or a cycle at 75 W | Either treadmill walking at 1.34 m/s, 3% grade or cycling at 75 W in 35°C, 75% RH conditions | – | Tre | Before: 37.0 ± 0.3°C After: 36.7 ± 0.4°C (S) | Before: 1.0 ± 0.2°C/h After: 0.8 ± 0.3°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Lee et al., 2012 | 32°C dry bulb 70% RH 400 W/m2 solar radiation | 18 | EPW: Three 60 min marches on the treadmill at 4 km/h, 0% gradient in Skeletal Battle Order (SBO) or Full Battle Order (FBO) | Outdoor route marches at 4 km/h in 29°C, 80% RH conditions for 10 days | – | Tgi | BeforeSBO: 37.2 ± 0.3°C AfterSBO: 37.0 ± 0.3°C BeforeFBO: 37.1 ± 0.4°C AfterFBO: 37.0 ± 0.3°C (NS) | BeforeSBO: 0.4 ± 0.2°C/h AfterSBO: 0.4 ± 0.2°C/h BeforeFBO: 0.4 ± 0.2°C/h AfterFBO: 0.5 ± 0.2°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Kotze et al., 1977 | 32.2°C wet bulb 33.9°C dry bulb 0.4 m/s wind velocity | 4 | EPW: 4 h block stepping at an external workload after receiving placebo | 4 h exposures to 32.2°C wet bulb, 33.9°C dry bulb conditions for 10 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.5 ± 0.2°C After: 37.1 ± 0.2°C | Before: 0.5 ± 0.1°C/h After: 0.3 ± 0.1°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Kobayashi et al., 1980 | 33.5°C 60% RH | 5 | EPW: 60 min cycle at 60 to 70% VO2 max | 100 min exposures to 45 to 50°C, 30 to 40% RH conditions for 9 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.4 ± 0.2°C After: 37.0 ± 0.4°C (S) | Before: 2.0 ± 0.4°C/h After: 2.2 ± 0.5°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Saat et al., 2005 | 31.1°C 70% RH | 16 | EPW: 60 min cycle at 60% VO2 max | 60 min exposures to 31.1°C, 70% RH conditions for 14 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.35 ± 0.34°C After: 37.14 ± 0.32°C (NS) | – | – |

| Patterson et al., 2004 | 39.8°C 59.2% RH | 6 | EPW: 90 min cycle at ~44% Wpeak | 90 min exposures to 40°C, 60% RH conditions for 16 days | – | Toes | Before: 36.97 ± 0.20°C After: 36.74 ± 0.14°C (REQ) | Before: 1.27± 0.15°C/h After: 1.04± 0.31°C/h (REQ) | – |

| Garrett et al., 2009 | 35°C 60% RH | 10 | EPW: 90 min cycling at 40% peak power output | 90 min exposures to 40°C, 60% RH conditions for 5 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.05 ± 0.37°C After: 36.95 ± 0.26°C (REQ) | Before: 1.03± 0.41°C/h After: 0.90± 0.31°C/h (REQ) | – |

| Garrett et al., 2012 | 35°C 60% RH | 8 | EPW: 10 min rowing at 30% peak power output, followed by 10 min rowing at 60% peak power output | 90 min exposures to 39.5°C, 60% RH conditions for 5 days | – | Tre | Before: 37.33 ± 0.16°C After: 37.28 ± 0.28°C (REQ) | Before: 2.04± 0.82°C/h After: 1.38± 0.98°C/h (REQ) | – |

| James C. A. et al., 2017 | 32°C 60% RH | 10 | EP: 5 km running time trial | 90 min exposures to 37°C, 59% RH conditions for 5 days | Faster time trial time (S) | Tre | Before: 36.97 ± 0.33°C After: 36.83 ± 0.32°C (S) | – | |

| James et al., 2018 | 32°C 60% RH | 9 | EP: 5 km running time trial | 90 min exposures to 37°C, 60% RH conditions for 5 days | Faster time trial time (S) | Tre | Before: 37.12 ± 0.22°C After: 37.03 ± 0.23°C (NS) | Before: 5.41 ± 0.91°C/h After: 5.56 ± 0.25°C/h (CAL) | Before: 39.34 ± 0.3°C After: 39.16 ± 0.44°C (S) |

| Willmott et al., 2016 | 30°C 60% RH | 14 | EP: 5 km running time trial | STHA: 45 min cycling at 50% VO2peak at 35°C, 60% RH once for 4 daysTDHA: 45 min cycling at 50% VO2peak at 35°C, 60% twice daily for 2 days | No influence on time trial time. | Tre | STHA - Before: 37.5 ± 0.4°C After: 37.3 ± 0.3°C (NS) TDHA – Before: 37.4 ± 0.3°C After: 37.3 ± 0.2°C (NS) (Graph) | STHA - Before: 38.69 ± 0.38°C After: 38.53 ± 0.45°C (NS) TDHA – Before: 38.59 ± 0.37°C After: 38.52 ± 0.5°C (NS) (Graph) | |

| Brade et al., 2013 | 35°C 60% RH | 10 | EPW: 70 min repeat sprint protocol | 32–48 min cycling exposure at 35°C, 60% RH conditions for 5 days | No influence on performance | Tgi | Before: 37.0 ± 0.4°C After: 36.9 ± 0.3°C | Before: 1.54 ± 0.48°C/h After: 1.37 ± 0.36°C/h (CAL) | Before: 38.8 ± 0.4°C After: 38.5 ± 0.3°C |

| Zimmermann et al., 2018 | 35°C 50% RH | 8 | EP: 800 kJ cycling time trial | 60 min cycling at 50% VO2peak at 35°C, 49% RH conditions for 10 days (5 days on, 2 off, 5 days on) | Faster cycling time | Tgi | Before: 36.9 ± 0.3°C After: 36.7 ± 0.4°C | Before: 3.23 ± 1.31 °C/h After: 3.57 ± 1.04°C/h | Before: 39.0 ± 0.8°C After: 38.9 ± 0.5°C |

Summary of heat acclimation/acclimatization studies.

RH, relative humidity; EC, exercise capacity; EP, exercise performance; EPW, exercise performance at a fixed workload; S, significant; NS, not significant; CAL, calculated values; REQ, requested values; Graph, graph-extracted values; Tre, rectal temperature; Toes, oesophageal temperature; Tac, auditory canal temperature; Tgi, gastrointestinal temperature; MF, moderately fit subjects; HF, highly fit subjects; STHA, Short term Heat acclimation and acclimatization (HA); TDHA, Twice daily HA; LTHA, Long term HA.

Table 3

| Study | Ambient conditions | N = | Exercise protocol | Intervention method | Exercise outcome | Tc measure | Tc before | Tc rate of rise | Tc end |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COLD WATER IMMERSION | |||||||||

| Kay et al., 1999 | 31.4°C 60.2% RH | 7 | EP: 30 min self-paced cycling time trial | CON: 30 min rest INT: Whole body water immersion for 58.6 min | Greater distance covered (S) | Tre | – | – | CON: 38.7 ± 0.3°C INT: 38.4 ± 0.5°C (NS) |

| Booth et al., 1997 | 32°C 60% RH | 8 | EP: 30 min running time trial | CON: No cooling INT: Cold water immersion for 60 min before exercise | Greater distance covered (S) | Tre | CON: 37.4 ± 1.1°C INT: 36.7 ± 0.3°C (S) | – | CON: 39.6 ± 0.6°C INT: 38.9 ± 0.6°C (NS) |

| Tsuji et al., 2012 | 37°C 50% RH | 10 | EC: Cycle at 50% VO2 peak to exhaustion | CON: 25 min immersion in 35°C water INT: 25 min immersion in 18°C water | Longer time to exhaustion (S) | Toes | CON: 36.9 ± 0.3°C INT: 36.1 ± 0.3°C (S) | – | – |

| Gonzalez-Alonso et al., 1999b | 40°C 19% RH | 7 | EC: Cycle at 60% VO2 max to exhaustion | CON: 30 min immersion in 36°C water INT: 30 min immersion in 17°C water | Longer time to exhaustion (S) | Toes | CON: 37.4 ± 0.3°C INT: 35.9 ± 0.5°C (S) | CON: 3.7 ± 0.1°C/h INT: 4.0 ± 0.1°C/h (CAL) | CON: 40.2 ± 0.3°C INT: 40.1 ± 0.3°C (NS) |

| Yeargin et al., 2006 | 27°C | 15 | EP: 2 mile time trial | CON: No cooling (mock treatment)INT: 12 min immersion in 14°C water during recovery | Shorter run time (S) | Tre | CON: 37.82 ± 0.54°C INT: 37.39 ± 0.77°C (S) | – | CON: 38.87 ± 0.50°C INT: 38.59 ± 0.58°C (S) |

| Barr et al., 2011 | 49°C 12% RH | 8 | EPW: 20 min treadmill walk at 5 km/h, 7.5% grade | CON: No coolingINT: 15 min hand/forearm immersion during recovery | – | Tgi | CON: 38.3 ± 0.2°C INT: 38.0 ± 0.2°C (S) | CON: 2.7 ± 0.8°C/hINT: 2.4 ± 1.1°C/h(CAL) | – |

| Wilson et al., 2002 | 21.3°C 22.4% RH | 8 | EPW: 60 min cycle at 60% VO2 max | CON: 30 min immersion in 35°C waterINT: 30 min immersion in 18°C water | – | Tre | CON: 36.81 ± 0.25°C INT: 36.14 ± 0.51°C (S) | – | – |

| Smith et al., 2013 | 21.6°C 20% RH | 10 | EC: Incremental treadmill protocol beginning at 2.7 km/h, 10% grade | CON: No cooling INT: 24 min immersion in 23°C water | Shorter time to exhaustion (S) | Tgi | CON: 37.1 ± 0.4°C INT: 36.6 ± 0.3°C (S) | CON: 2.0 ± 1.1°C/h INT: 1.2 ± 1.4°C/h (CAL) | CON: 37.6 ± 0.4°C INT: 36.9 ± 0.3°C (S) |

| Duffield et al., 2010 | 33°C 50% RH | 8 | EP: 40 min cycling time trial | CON: No cooling INT: 20 min lower body immersion in 14°C water | Greater mean power (S) | Tre | CON: 37.6 ± 0.3°C INT: 37.7 ± 0.3°C (REQ) | – | CON: 39.0 ± 0.4°C INT: 38.9 ± 0.3°C (REQ) |

| Siegel et al., 2012 | 34.0°C 52% RH | 8 | EC: Treadmill run at first ventilatory threshold to exhaustion | CON: No cooling INT: 30 min immersion in 24°C water | Longer time to exhaustion (S) | Tre | CON: 37.11 ± 0.28°C INT: 37.14 ± 0.34°C (REQ) | CON: 2.88 ± 0.96°C/h INT: 2.28 ± 1.56°C/h (CAL) | CON: 39.48 ± 0.36°C INT: 39.48 ± 0.34°C (NS) |

| Hasegawa et al., 2006 | 32°C 80% RH | 9 | EPW: 60 min cycle at 60% VO2 max | CON: No cooling INT: 30 min immersion in 25°C water | – | Tre | CON: 37.36 ± 0.15°C INT: 36.80 ± 0.30°C (REQ) | CON: 1.76 ± 0.21°C/h INT: 1.85 ± 0.48°C/h (REQ) | – |

| Castle et al., 2006 | 34°C 52% RH | 12 | EPW: 40 min intermittent cycling sprint protocol | CON: No cooling INT: 20 min immersion in 18°C water | More work done (S) | Tre | CON: 37.5 ± 0.1°C INT: 37.1 ± 0.1°C (S) (Graph) | CON: 2.3 ± 0.3°C/h INT: 2.0 ± 0.4°C/h (CAL) | CON: 39.0 ± 0.1°C INT: 38.4 ± 0.1°C (S) (Graph) |

| Clarke et al., 2017 | 32°C 47% RH | 8 | EPW: 90 min treadmill run at 65% VO2 max | CON: 60 min rest INT: 60 min immersion in 20°C water | – | Tre | CON: 36.7 ± 0.3°C INT: 35.7 ± 0.9°C (S) (Graph) | CON: 1.5 ± 0.3°C/h INT: 2.1 ±°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.9 ± 0.5°C INT: 38.8 ± 0.5°C (NS) (Graph) |

| Lee et al., 2018 | 32°C 47% RH | 8 | EPW: 90 min treadmill run at 65% VO2max | CON: 60 min rest INT: 60 min immersion in 20°C water | – | Tre | CON: 36.7 ± 0.3°C INT: 35.7 ± 0.9°C (S) (Graph) | CON: 1.56 ± 0.45°C/h INT: 2.15 ± 0.72°C/h (S) | CON: 38.9 ± 0.5°C INT: 38.9 ± 0.5°C |

| Skein et al., 2012 | 31°C 33% RH | 10 | EPW: 50 min self-paced intermittent sprint exercise protocol | CON: 15 min rest INT: 15 min immersion in 10°C water | Longer total sprint time (S) | Tgi | CON: 37.3 ± 0.2°C INT: 36.8 ± 0.4°C (S) (Graph) | – | CON: 38.9 ± 0.5°C INT: 38.7 ± 0.7°C (NS) (Graph) |

| Stevens et al., 2017 | 33°C 46% RH | 9 | EP: 5 km self-paced running time trial | CON: No cooling INT: 30 min immersion in 23–24°C water | Faster running time (S) | Tre | CON: 37.3 ± 0.3°C INT: 36.7 ± 0.4°C (S) (Graph) | CON: 3.8 ± 0.3°C/h INT: 4.7 ± 0.3°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.9 ± 0.3°C INT: 38.6 ± 0.4°C (S) (Graph) |

| COLD AIR EXPOSURE | |||||||||

| Lee and Haymes, 1995 | 24°C 51–52% RH | 14 | EC: Treadmill run at 82% VO2 max to exhaustion | CON: 30 min rest in a 24°C, 53% RH room INT: 33 min rest in a 5°C, 68% RH room | Longer time to exhaustion (S) | Tre | – | CON: 3.86 ± 0.51°C/h INT: 3.76 ± 0.54°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.02 ± 0.46°C INT: 37.86 ± 0.53°C (NS) |

| Olschewski and Bruck, 1988 | 18°C 50% RH | 6 | EC: Cycling with a constant increase in workload to exhaustion | CON: No cooling INT: Double cold air exposure before starting exercise | Longer time to exhaustion (S) | Toes | – | – | CON: 38.94 ± 0.34°C INT: 38.64 ± 0.27°C (S) |

| COLD VEST OR ICE VEST | |||||||||

| Stannard et al., 2011 | 24–26°C 29–33% RH | 8 | EP: 10 km running time trial | CON: Wearing a t-shirt INT: Wearing a cooling vest for 30 min before time trial | No influence on run time | Tgi | CON: 37.7 ± 0.72°C INT: 37.3 ± 0.73°C (NS) | – | – |

| Arngrimsson et al., 2004 | 32°C 50% RH | 17 | EP: 5 km running time trial | CON: Wearing a t-shirt INT: Wearing an ice vest for 38 min before time trial | Shorter run time (S) | Toes | CON: 37.4 ± 0.4°C INT: 37.1 ± 0.5°C (S) | – | CON: 39.8 ± 0.4°C INT: 39.7 ± 0.4°C (REQ) |

| Kenny et al., 2011 | 35°C 65% RH | 10 | EPW: 120 min treadmill walk at 3 miles/h, 2% grade | CON: NBC suit without ice vest INT: NBC suit with ice vest | – | Toes | CON: 36.88 ± 0.13°C INT: 36.94 ± 0.25°C (NS) | CON: 1.08 ± 0.22°C/h INT: 0.90 ± 0.24°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Bogerd et al., 2010 | 29.3°C 80% RH | 8 | EPW: 60 min cycle at 65% VO2 peak | CON: No coolingINT: Wearing an ice vest for 45 min before exercise | – | Tre | CON: 37.0 ± 0.2°C INT: 37.1 ± 0.2°C (NS) | CON: 2.1 ± 0.54°C/h INT: 2.0 ± 0.54°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Barr et al., 2011 | 49°C 12% RH | 8 | EPW: 20 min treadmill walk at 5 km/h, 7.5% grade | CON: No cooling INT: Wearing an ice vest for 15 min during recovery | – | Tgi | CON: 38.3 ± 0.2°C INT: 38.2 ± 0.1°C (NS) | CON: 2.7 ± 0.8°C/h INT: 2.7 ± 0.4°C/h (CAL) | - |

| Quod et al., 2008 | 34.3°C 41.2% RH | 6 | EP: 40 min cycling time trial | CON: No cooling INT: Wearing a cooling jacket for 40 min before exercise | No influence on cycling time | Tre | – | – | CON: 39.6 ± 0.4°C INT: 39.7 ± 0.5°C (REQ) |

| Brade et al., 2014 | 35°C 60% RH | 12 | EPW: 70 min repeat sprint protocol | CON: No cooling INT: Wearing a cooling jacket for 30 min before exercise | No influence on performance | Tgi | CON: 37.0 ± 0.4°C INT: 36.9 ± 0.3°C | CON: 1.6 ± 0.3°C/h INT: 1.7 ± 0.3°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.9 ± 0.3°C INT: 38.9 ± 0.5°C |

| Castle et al., 2006 | 34°C 52% RH | 12 | EPW: 40 min intermittent cycling sprint protocol | CON: No cooling INT: Wearing an ice vest for 20 min before exercise | More work done (S) | Tre | CON: 37.5 ± 0.1°C INT: 37.3 ± 0.1°C (NS) (Graph) | CON: 2.3 ± 0.3°C/h INT: 2.3 ± 0.5°C/h (CAL) | CON: 39.0 ± 0.1°C INT: 38.8 ± 0.2°C (NS) (Graph) |

| Faulkner et al., 2015 | 35°C 51% RH | 10 | EPW: 1 h cycling time trial at 75% Wmax | CON: No cooling INTCOLD: Wearing a frozen cooling garment for 30 min before exercise INTCOOL: Wearing a cooling garment saturated in 14°C water for 30 min before exercise | Faster time trial for COLD (S) No influence on performance for COOL | Tgi | CON: 36.7 ± 0.4°C INTCOLD: 36.5 ± 0.3°C INTCOOL: 36.7 ± 0.6°C (NS) | CON: 1.9 ± 0.3°C/h INTCOLD: 2.2 ± 0.2°C/h INTCOOL: 1.9 ± 0.4°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.6 ± 0.5°C INTCOLD: 38.7 ± 0.4°C INTCOOL: 38.6 ± 0.5°C (NS) |

| COLD FLUID INGESTION | |||||||||

| Byrne et al., 2011 | 32°C dry bulb 60% RH 3.2 m/s air velocity | 7 | EP: 30 min self-paced cycling time trial | CON: 37°C fluid INT: 2°C fluid | Greater distance covered (S) | Tre | – | – | CON: 38.6 ± 0.5°C INT: 38.1 ± 0.3°C (NS) |

| Lee et al., 2008 | 35.0°C 60% RH | 8 | EC: Cycle at 65% VO2 peak to exhaustion | CON: Warm drink (37°C) INT: Cold drink (4°C) | Longer time to exhaustion (S) | Tre | CON: 36.8 ± 0.3°C INT: 36.4 ± 0.3°C (S) | CON: 3.0 ± 0.2°C/h INT: 2.9 ± 0.2°C/h (REQ) | CON: 39.4 ± 0.4°C INT: 39.5 ± 0.4°C (REQ) |

| ICE SLURRY INGESTION | |||||||||

| Siegel et al., 2012 | 34.0°C 52% RH | 8 | EC: Treadmill run at first ventilatory threshold to exhaustion | CON: Warm fluid (37°C) INT: Ice slurry mixture (−1°C) | Longer time to exhaustion (S) | Tre | CON: 37.11 ± 0.28°C INT: 36.70 ± 0.31°C (REQ) | CON: 2.88 ± 0.96°C/h INT: 3.60 ± 1.20°C/h (CAL) | CON: 39.48 ± 0.36°C INT: 39.76 ± 0.36°C (S) |

| Siegel et al., 2010 | 34.0 ± 0.2°C 54.9 ± 5.9% RH | 10 | EC: Treadmill run at first ventilatory threshold to exhaustion | CON: Cold water (4°C) INT: Ice slurry (−1°C) | Longer time to exhaustion (S) | Tre | CON: 36.87 ± 0.11°C INT: 36.55 ± 0.16°C (REQ) | CON: 3.00 ± 0.72°C/h INT: 3.24 ± 0.48°C/h (CAL) | CON: 39.05 ± 0.37°C INT: 39.36 ± 0.41°C (S) |

| Stanley et al., 2010 | 34°C 60% RH | 10 | EP: Perform a set amount of work in as fast a time as possible | CON: Cold liquid beverage (18.4°C) INT: Ice-slush beverage (−0.8°C) | No influence on cycle time | Tre | CON: 37.4 ± 0.2°C INT: 37.0 ± 0.3°C (S) | – | CON: 39.1 ± 0.4°C INT: 39.0 ± 0.5°C (NS) |

| Yeo et al., 2012 | 28.2°C wet bulb globe temperature | 11 | EP: 10 km outdoor running time trial | CON: Ambient temperature drink (30.9°C) INT: Ice slurry (-1.4°C) | Faster performance time (S) | Tgi | CON: 37.2 ± 0.3°C INT: 36.9 ± 0.3°C (REQ) | – | CON: 39.8 ± 0.4°C INT: 40.2 ± 0.6°C (S) |

| Brade et al., 2014 | 35°C 60% RH | 12 | EPW: 70 min repeat sprint protocol | CON: No cooling INT: Ice slurry (0.6°C) | No influence on performance | Tgi | CON: 37.0 ± 0.4°C INT: 36.9 ± 0.4°C | CON: 1.6 ± 0.3°C/h INT: 1.8 ± 0.3°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.9 ± 0.3°C INT: 39.0 ± 0.4°C |

| Burdon et al., 2013 | 32°C 40% RH | 10 | EP: 4 kJ/kg BM cycling time trial | CON: Thermoneutral drink (37°C) INT: Ice slurry (−1°C) | Improved cycle time | Tre | CON: 36.9 ± 0.2°C INT: 36.8 ± 0.3°C (NS) (Graph) | CON: 5.3 ± 0.1°C/h INT: 6.2 ± 0.2°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.7 ± 0.1°C INT: 38.7 ± 0.3°C (NS) (Graph) |

| Gerrett et al., 2017 | 31°C 41% RH | 12 | EPW: 31 min self-paced intermittent running protocol | CON: Water (23°C) INT: Ice slurry (0.1°C) | No influence on distance covered | Tgi | CON: 37.2 ± 0.2°C INT: 36.7 ± 0.4°C (S) (Graph) | CON: 3.3 ± 0.2°C/h INT: 3.7 ± 0.3°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.9 ± 0.3°C INT: 38.6 ± 0.3°C (NS) (Graph) |

| James et al., 2015 | 32°C 62% RH | 12 | EC: Running with increase workload till exhaustion | CON: No cooling INT: Ice slurry (−1°C) | Tre | CON: 37.21 ± 0.31°C INT: 36.94 ± 0.31°C (S) (Graph) | CON: 1.11 ± 0.29°C/h INT: 1.38 ± 0.26°C/h (NS) | CON: 39.03 ± 0.45°C INT: 38.96 ± 0.55°C (NS) | |

| Stevens et al., 2016 | 33°C 46% RH | 11 | EP: 5 km self-paced running time trial | CON: No cooling INT: Ice slurry (−1°C) | No influence on running time | Tre | CON: 37.2 ± 0.4°C INT: 36.9 ± 0.3°C (S) | CON: 4.4 ± 0.2°C/h INT: 4.9 ± 0.2°C/h (CAL) | CON: 39.12 ± 0.25°C INT: 39.04 ± 0.28°C (NS) |

| Takeshima et al., 2017 | 30°C 80% RH | 10 | EC: Cycle at 55% peak power output to exhaustion | CON: No cooling INT: Ice slurry (−1°C) | Longer run time (S) | Tre | CON: 37.5 ± 0.3°C INT: 37.1 ± 0.2°C (S) | CON: 2.0 ± 0.2°C/h INT: 2.1 ± 0.2°C/h (CAL) | CON: 39.2 ± 0.3°C INT: 39.2 ± 0.3°C (NS) |

| Zimmermann and Landers, 2015 | 33°C 60% RH | 9 | EPW: 72 min intermittent sprint protocol | CON: Water (25°C) INT: Ice slurry (−0.5°C) | No influence on performance | Tgi | CON: 36.7 ± 0.4°C INT: 36.0 ± 0.4°C (S) (Graph) | – | CON: 38.2 ± 0.4°C INT: 37.8 ± 0.4°C (NS) (Graph) |

| Zimmermann et al., 2017a | 35°C 50% RH | 10 | EPW: 60 min cycling at 55% VO2peak | CON: Water INT: Ice slurry | – | Tgi | CON: 36.7 ± 0.3°C INT: 36.2 ± 0.1°C (S) (Graph) | CON: 1.3 ± 0.3°C/h INT: 1.5 ± 0.1°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.0 ± 0.3°C INT: 37.7 ± 0.2°C (S) (Graph) |

| Zimmermann et al., 2017b | 35°C 50% RH | 10 | EP: 800 kJ cycling time trial | CON: Water INT: Ice slurry | No influence on cycling time | Tgi | CON: 37.1 ± 0.4°C INT: 36.4 ± 0.4°C (S) | CON: 1.8 ± 0.3°C/h INT: 2.5 ± 0.2°C/h (CAL) | CON: 39.0 ± 0.5°C INT: 39.0 ± 0.4°C (NS) (Graph) |

Summary of pre-event cooling studies.

RH, relative humidity; EC, exercise capacity; EP, exercise performance; EPW, exercise performance at a fixed workload; S, significant; NS, not significant; CAL, calculated values; REQ, requested values; Graph, graph-extracted values; Tre, rectal temperature; Toes, oesophageal temperature; Tgi, gastrointestinal temperature; CON, control; INT, intervention.

Table 4

| Study | Ambient conditions | N = | Exercise protocol | Intervention method | Exercise outcome | Tc measure | Tc before | Tc rate of rise | Tc end |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUHYDRATED STATE WITH LOW FLUID/AD LIBITUMvs. HIGH FLUID INTAKE | |||||||||

| Marino et al., 2004 | 31.3°C 63.3% RH 2 m/s wind speed | 8 | EC: Cycle at 70% peak power output to exhaustion | CON: Fluid replacement equal to half the sweat rate INT: Fluid replacement equal to sweat rate | No influence on cycling time | Tre | CON: 38.7 ± 0.4°C INT: 38.6 ± 0.5°C (REQ) | – | CON: 39.0 ± 0.4°C INT: 38.8 ± 0.6°C (NS) |

| Dugas et al., 2009 | 33°C 50% RH | 6 | EP: 80 km cycling time trial | CON: Fluid ingested to replace 33% of weight lost INT: Fluid ingested to replace 100% of weight lost | No influence on cycling time | Tre | CON: 36.8 ± 0.1°C INT: 36.9 ± 0.2°C (NS) | – | CON: 39.2 ± 0.5°C INT: 38.9 ± 0.4°C (NS) |

| Montain and Coyle, 1992a | 33°C 50% RH 2.5 m/s wind speed | 8 | EPW: 2 h cycle at a power output equal to 62–67% maximal oxygen consumption | CON: Small (50%) fluid replacement INT: Large (80%) fluid replacement | – | Toes | CON: 37.01 ± 0.20°C INT: 37.01 ± 0.26°C (REQ) | CON: 0.60 ± 0.14°C/h INT: 0.47 ± 0.18°C/h (REQ) | – |

| McConell et al., 1997 | 21°C 43% RH | 7 | EPW: 2 h cycle at 60% VO2 peak | CON: 50% fluid replacement INT: 100% fluid replacement | – | Tre | CON: 37.2 ± 0.2°C INT: 37.1 ± 0.2°C (REQ) | CON: 0.8 ± 0.3°C/h INT: 0.7 ± 0.1°C/h (REQ) | – |

| Bardis et al., 2017 | AD: 31.4 ± 0.5°C PD: 31.7 ± 0.4°C (NS) 6.4 m/s | 10 | EPW: 3 sets of 5 km cycling at 50% maximal power output followed by 5 km cycling all out at 3% grade (Total 30 km) | CON: ad libitum water intake INT: Fluid ingested to replace 100% of fluid lost via sweating | Faster cycling speed (S) | Tgi | CON: 37.4 ± 0.1°C INT: 37.6 ± 0.2°C (NS) (Graph) | – | CON: 38.7 ± 0.4°C INT: 38.4 ± 0.4°C (S) (Graph) |

| James L. J. et al., 2017 | 34°C 50% RH 0.3–0.4 m/s | 7 | EPW: 15 min cycling performance test | CON: Fluid replacement to induce 2.5% body mass loss INT: Fluid replacement to replace sweat loss | More work completed (S) | Tgi | CON: 37.0 ± 0.2°C INT: 37.2 ± 0.3°C (Graph) | CON: 6.8 ± 1.8°C/h INT: 4.4 ± 2.3°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.7 ± 0.5°C INT: 38.3 ± 0.5°C |

| Périard et al., 2014 | 37°C 33% RH | 10 | EPW: 20 min tennis match | CON: ad libitum water intake INT: Fluid ingested to match 70% of sweat loss | – | CON: 37.8 ± 0.3°C INT: 37.7 ± 0.3°C (NS) (Graph) | CON: 4.8 ± 1.75°C/hINT: 4.5 ± 2.0°C/h(CAL) | CON: 39.4 ± 0.5°C INT: 39.2 ± 0.6°C (NS) | |

| EUHYDRATED STATE WITH NO FLUID VS. HIGH FLUID INTAKE | |||||||||

| Marino et al., 2004 | 31.3°C 63.3% RH 2 m/s wind speed | 8 | EC: Cycle at 70% peak power output to exhaustion | CON: No fluid replacement INT: Fluid replacement equal to sweat rate | Longer time to exhaustion (S) | Tre | CON: 38.8 ± 0.4°C INT: 38.6 ± 0.5°C (NS) | – | CON: 39.2 ± 0.4°C INT: 38.8 ± 0.6°C (NS) |

| Hargreaves et al., 1996 | 20–22°C | 5 | EPW: 2 h cycle at 67% VO2 peak | CON: No fluid ingested INT: Ingestion of fluid to prevent loss of body mass | – | Tre | CON: 36.7 ± 0.2°C INT: 36.7 ± 0.4°C (NS) | CON: 0.9 ± 0.3°C/h INT: 0.6 ± 0.3°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Armstrong et al., 1997 | 33°C 56% RH 0.1 m/s air speed | 10 | EPW: 90 min treadmill walk at 5.6 km/h, 5% grade | CON: No water intake INT: ad libitum water intake | – | Tre | – | CON: 0.7 ± 0.2°C/h INT: 0.6 ± 0.2°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Robinson et al., 1995 | 20°C 60% RH 3 m/s air speed | 8 | EP: 60 min cycle to achieve greatest possible distance | CON: No fluid ingested INT: Ingestion of fluid to replace approximate sweat loss | Less distance covered (S) | Tre | CON: 36.8 ± 0.3°C INT: 36.5 ± 0.6°C (NS) | – | CON: 38.6 ± 0.6°C INT: 38.1 ± 0.6°C (NS) |

| Fallowfield et al., 1996 | 20°C | 8 | EC: Treadmill run at 70% VO2 max to exhaustion | CON: No fluid ingested INT: Fluid replacement before and during exercise | Longer time to exhaustion (S) | Tre | – | – | CON: 38.8 ± 1.1°C INT: 39.1 ± 0.6°C (NS) |

| Coso et al., 2008 | 36°C 29% RH 1.9 m/s airflow | 7 | EPW: 120 min cycle at 63% VO2 max | CON: No fluid ingested INT: Ingestion of mineral water | – | Tre | CON: 37.6 ± 0.3°C INT: 37.6 ± 0.3°C (NS) | CON: 0.9 ± 0.2°C/h INT: 0.6 ± 0.2°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Cheung and McLellan, 1997 | 40°C 30% RH | 8 | EC: Either a light (3.5 km/h, 0% grade) or a heavy (4.8 km/h, 4% grade) treadmill walk to exhaustion | CON: No fluid replacement INT: Fluid replacement | Longer time to exhaustion (S) for light exercise | Tre | CONlight: 36.89 ± 0.29°C INTlight: 36.85 ± 0.28°C (NS) CONheavy: 36.88 ± 0.21°C INTheavy: 36.94 ± 0.27°C (NS) | CONlight: 1.19 ± 0.46°C/h INTlight: 1.15 ± 0.32°C/h (CAL) CONheavy: 1.88 ± 0.32°C/h INTheavy: 1.76 ± 0.42°C/h (CAL) | CONlight: 38.74 ± 0.68°C INTlight: 38.90 ± 0.40°C (NS) CONheavy: 38.71 ± 0.43°C INTheavy: 38.69 ± 0.62°C (NS) |

| Munoz et al., 2012 | 33°C 30% RH | 10 | EP: 5 km running time trial | CON: No rehydration INT: Oral rehydration | No influence on performance time | Tre | CON: 37.78 ± 0.41°C INT: 37.57 ± 0.31°C (NS) | – | CON: 39.19 ± 0.45°C INT: 38.97 ± 0.36°C (NS) |

| Kay and Marino, 2003 | 33.2°C 63.3% RH | 7 | EP: 60 min cycle to achieve greatest possible distance | CON: No fluid ingested INT: Fluid ingested to prevent any change in body mass | No influence on distance cycled | Tre | – | – | CON: 38.9 ± 0.5°C INT: 38.7 ± 0.4°C (NS) |

| Dugas et al., 2009 | 33°C 50% RH | 6 | EP: 80 km cycling time trial | CON: No fluid ingested INT: Fluid ingested to replace 100% of weight lost | No influence on cycling time | Tre | CON: 36.8 ± 0.2°C INT: 36.9 ± 0.2°C (NS) | – | CON: 39.2 ± 0.4°C INT: 38.9 ± 0.4°C (NS) |

| Hasegawa et al., 2006 | 32°C 80% RH | 9 | EPW: 60 min cycle at 60% VO2 max | CON: No water intake INT: Water ingestion at 5 min intervals | – | Tre | CON: 37.37 ± 0.15°C INT: 37.37 ± 0.16°C (REQ) | CON: 1.77 ± 0.22°C/h INT: 1.39 ± 0.27°C/h (REQ) | – |

| Gagnon et al., 2012 | 42°C 20% RH 1 m/s air speed | 8 untrained 8 trained | EPW: 120 min cycle at 120 W | CON: No fluid replacement INT: Fluid replacement | – | Toes | CONUT: 37.23 ± 0.57°C INTUT: 36.96 ± 0.25°C CONT: 36.80 ± 0.28°C INTT: 36.69 ± 0.25°C (NS) | CONUT: 0.74 ± 0.28°C/h INTUT: 0.70 ± 0.18°C/h CONT: 1.20 ± 0.25°C/h INTT: 0.81 ± 0.24°C/h (CAL) | – |

| Montain and Coyle, 1992b | 33°C 50% RH 2.5 m/s wind speed | 8 | EPW: 2 h cycle at a power output equal to 62–67% maximal oxygen consumption | CON: No fluid replacement INT: Large (80%) fluid replacement | – | Toes | CON: 36.99 ± 0.36°C INT: 37.01 ± 0.26°C (REQ) | CON: 0.84 ± 0.24°C/h INT: 0.47 ± 0.18°C/h (REQ) | – |

| McConell et al., 1997 | 21°C 43% RH | 7 | EPW: 2 h cycle at 60% VO2 peak | CON: No fluid replacement INT: 100% fluid replacement | – | Tre | CON: 37.1 ± 0.2°C INT: 37.1 ± 0.2°C (REQ) | CON: 1.0 ± 0.2°C/h INT: 0.7 ± 0.1°C/h (REQ) | – |

| Wall et al., 2015 | 33°C 40% RH 32 km/h | 10 | EPW: 25 km cycling time trial | CON: No fluid replacement INT: 100% fluid replacement | No influence on cycling time | Tre | CON: 37.1 ± 0.2°C INT: 37.0 ± 0.2°C (NS) (Graph) | CON: 2.6 ± 0.5°C/h INT: 2.49 ± 0.53°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.9 ± 0.3°C INT: 38.7 ± 0.3°C (S) (Graph) |

| Wittbrodt et al., 2015 | 32°C 65% RH | 12 | EPW: 50 min cycling at 60% VO2peak | CON: No fluid intake INT: 100% fluid replacement | – | Tre | CON: 37.0 ± 0.3°C INT: 36.8 ± 0.8°C (NS) (Graph) | CON: 1.4 ± 0.7°C/h INT: 1.0 ± 1.3°C/h (CAL) | CON: 38.2 ± 0.5°C INT: 37.6 ± 0.7°C (S) (Graph) |

| Trangmar et al., 2015 | 35% 50% RH | 8 | EC: Cycling at 60% VO2max until volitional exhaustion | CON: No fluid intake INT: Fluid intake to replace body mass loss | Shorter exercise duration (S) | Tgi | CON: 37.4 ± 0.1°C INT: 37.3 ± 0.1°C (NS) | – | CON: 38.7 ± 0.1°C INT: 38.2 ± 0.2°C (S) |

| HYPOHYDRATED STATE WITH NO FLUID vs. HIGH FLUID INTAKE | |||||||||

| Armstrong et al., 1997 | 33°C 56% RH 0.1 m/s air speed | 10 | EPW: 90 min treadmill walk at 5.6 km/h, 5% grade | CON: No water Intake INT: ad libitum water intake | – | Tre | – | CON: 1.2 ± 0.2°C/h INT: 0.7 ± 0.2°C/h (CAL) | – |

Summary of fluid ingestion studies.

RH, relative humidity; EC, exercise capacity; EP, exercise performance; EPW, exercise performance at a fixed workload; S, significant; NS, not significant; CAL, calculated values; REQ, requested values; Graph, graph-extracted values; Tre, rectal temperature; Toes, oesophageal temperature; Tgi, gastrointestinal temperature; CON, control; INT, intervention.

Effect of Heat Mitigation Strategies on Tc

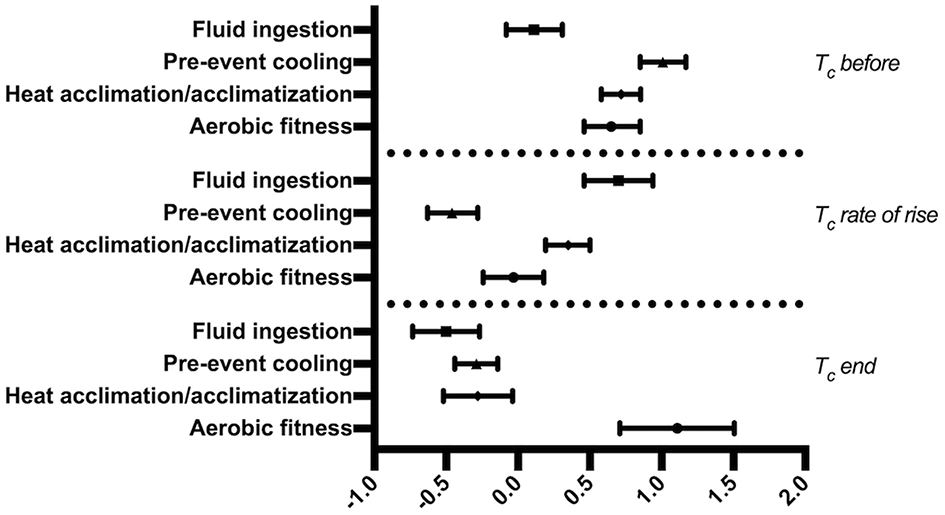

PC was found to be the most effective in the lowering of Tc before exercise (Hedge's g = 1.01; 95% Confidence Intervals 0.85–1.17; Figure 2). A moderate effect on lowering of Tc before exercise was observed for HA (0.72; 0.58 to 0.86) and AF (0.65; 0.46 to 0.85) while FI (0.11; −0.08 to 0.31) only exhibited a trivial effect on lowering Tc before exercise.

Figure 2

Forest plot of Hedges' g weighted averages of heat mitigation strategies effect on Tc at different points.

Rate of rise of Tc during exercise was most attenuated by FI (0.70; 0.46 to 0.94), followed by HA (0.35; 0.19 to 0.50). AF (−0.03; −0.24 to 0.18) showed a trivial effect on the rate of rise of Tc while PC (−0.46; −0.63 to −0.28) did not appear to be as effective in lowering the rate of rise of Tc.

AF (1.11; 0.71 to 1.51) exhibited a large effect on extending the limit of Tc at the end of exercise. However, HA (−0.28; −0.52 to −0.04), PC (−0.29; −0.44 to −0.14), and FI (−0.50; −0.74 to −0.27) did not seem as effective in extending the Tc limit at the end of exercise.

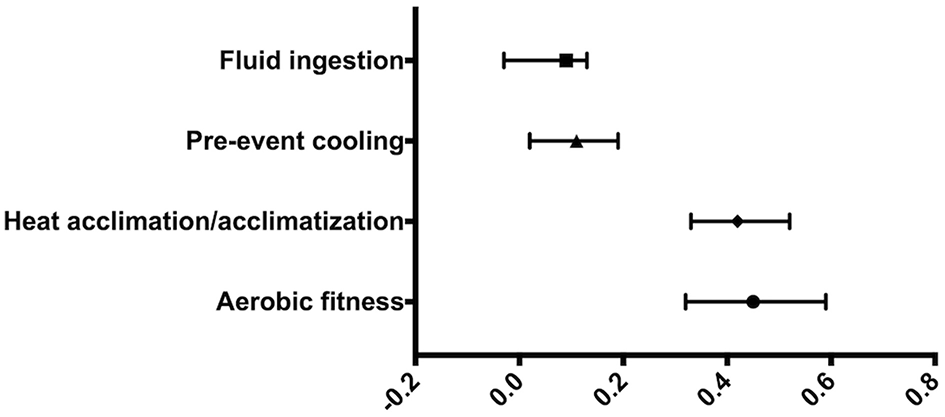

In combination, AF was found to be the most effective at favorably altering Tc (0.45; 0.32 to 0.59), followed by HA (0.42; 0.33 to 0.52), PC (0.11; 0.02 to 0.19) and FI (0.09; −0.03 to 0.13) (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Forest plot of combined Hedges' g weighted averages of heat mitigation strategies.

In addition, AF studies included both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies. We sought to determine if there was an effect on Tc variables when comparing “between subjects” and “within subjects” studies. We found that effect sizes were comparable with “between subjects” AF studies (0.45; 0.28 to 0.61) and “within subjects” AF studies (0.38; 0.14 to 0.61). The large overlap in CIs suggest that the inclusion of both study types did not have significantly different effects on Tc variables.

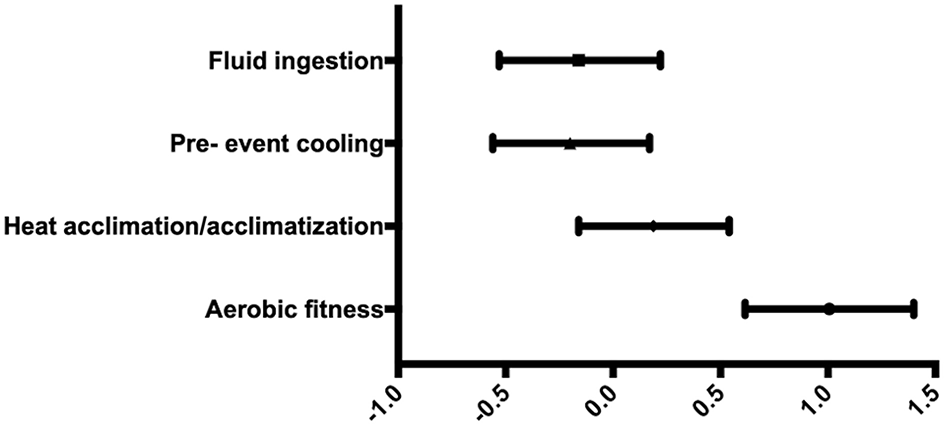

Effect of Heat Mitigation Strategies on Endurance

Of the 118 articles selected and used for analysis of the strategies based on effects on Tc, 45 studies also included measurements of endurance. The number of studies for each heat mitigation strategy is as follows: AF (n = 5), HA (n = 7), PC (n = 24), and FI (n = 9).

We observed that AF was the most effective in improving endurance (1.01; 1.40 to 0.61), followed by HA (0.19; −0.16 to 0.54), FI (−0.16; −0.53 to 0.22), and PC (−0.20; −0.56 to 0.17) (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Forest plot of Hedge's g weighted averages of heat mitigation strategies on endurance.

Discussion

This meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the efficacy of different heat mitigation strategies. Our main findings suggest that AF was most effective in altering Tc, followed by HA, PC and FI. A secondary objective was to evaluate the effect of these strategies on endurance. We observed that aerobic fitness was again the most beneficial, followed by heat acclimation/acclimatization, fluid ingestion and pre-cooling. It is noteworthy that the ranking of the effectiveness of the heat mitigation strategies on favorably altering Tc is similar to their effectiveness in improving endurance (Table 5).

Table 5

| Combined Hedge's g weighted averages effect on Tc | Rank | Combined Hedge's g weighted averages effect on performance and/or capacity | Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Fitness | 0.45 | 1 | 1.01 | 1 |

| Heat acclimation/acclimatization | 0.42 | 2 | 0.19 | 2 |

| Pre-exercise cooling | 0.11 | 3 | −0.20 | 4 |

| Fluid ingestion | 0.09 | 4 | −0.16 | 3 |

Ranking of heat mitigation strategies based on Hedges' g weighted averages.

Aerobic Fitness

Individuals with a higher aerobic fitness have been shown to have a lower pre-exercise Tc at rest (Selkirk and McLellan, 2001; Mora-Rodriguez et al., 2010). Aerobic fitness also enhances heat dissipation by lowering the threshold Tc at which both skin vasodilation and sweating occur (Nadel et al., 1974; Ichinose et al., 2009). Kuwahara et al. (2005) found that sweat rates of trained individuals were significantly higher than that of untrained individuals over a 30 min cycling exercise and that the onset of sweating occurred earlier on in the exercise as well. Higher aerobic fitness has also shown to cause an increase in skin blood flow (Fritzsche and Coyle, 2000). The combination of these two effects will lower Tc by enhancing heat dissipation during exercise in the heat. In addition, a greater aerobic fitness elicits a higher Tc attained at the end of exercise (Cheung and McLellan, 1998b; Selkirk and McLellan, 2001). This is corroborated by studies in marathon runners, where highly aerobically trained individuals were able to tolerate greater end Tc without any pathophysiological effects (Maron et al., 1977; Byrne et al., 2006). However, it should be noted that the ability to extend the limit of Tc at the end of exercise may pose as a double-edged sword, as highly motivated individuals may continue to exercise past the limits of acceptable Tc which could cause higher rates of exertional heat related illnesses occurring.

Heat Acclimation/Acclimatization

Heat acclimation/acclimatization refers to the physiological adaptations that occur as a result of prolonged, repeated exposure to heat stress (Armstrong and Maresh, 1991). It is noteworthy that the magnitude and duration of the heat acclimation/acclimatization protocols are important considerations in the development of the above physiological adaptations (Tyler et al., 2016). Previous meta-analysis and studies have shown that effects on cardiovascular efficiency and Tc may be achieved in protocols lasting less than 7 days, while thermoregulatory adaptations and improvements in endurance capacity and performance may require up to 14 days. For the benefits to be maximized, protocols longer than 2 weeks may also be considered (Armstrong and Maresh, 1991; Pandolf, 1998; Tyler et al., 2016). Heat acclimation/acclimatization has been shown to effectively reduce pre-exercise body temperature (Nielsen et al., 1993; Cotter et al., 1997). The physiological adaptations also observed include decreased heart rate (Harrison, 1985; Lorenzo and Minson, 2010), increased cardiac output (Harrison, 1985; Nielsen, 1996) and plasma volume (Mitchell et al., 1976; Lorenzo and Minson, 2010). Most significantly, cutaneous vasodilation occurs at a lower Tc threshold, together with an increase in skin blood flow (Roberts et al., 1977). The onset of sweating also occurs at a lower Tc threshold, resulting in increased sweat rates during exercise (Cotter et al., 1997; Cheung and McLellan, 1998a). Taken together, this helps to reduce the rate of rise of Tc during exercise due to increased cardiovascular efficiency and heat dissipation mechanisms.

However, for tropical natives, heat acclimatization does not lead to more efficient thermoregulation. In a study by Lee and colleagues (Lee et al., 2012), military soldiers native to a warm and humid climate were asked to undergo a 10 day heat acclimatization programme. Although there was an increase in work tolerance following acclimatization, no significant cardiovascular or thermoregulatory adaptations were found. These observations could suggest that thermoregulatory benefits of heat acclimatization are minimized in tropical natives, possibly due to the “partially acquired heat acclimatization status from living and training in a warm and humid climate” (Lee et al., 2012). Alternatively, thermoregulatory benefits from heat acclimatization may also be minimized in tropical natives due to modern behavioral adaptations such as the usage of air conditioning in living spaces and the avoidance of exercise during the hottest periods of the day that reduce the environmental heat stimulus experienced (Bain and Jay, 2011). In addition, evaporative heat loss through sweating is compromised with high relative humidity and therefore results in a higher rate of rise of Tc during exercise (Maughan et al., 2012).

It is also noteworthy that heat acclimation/acclimatization encompasses aerobic fitness as well. In most protocols, there is some form of training in the simulated laboratory settings or in the natural environmental settings. Few studies have attempted to separate the effects of heat acclimation from aerobic fitness. A study by Ravanelli et al. (2018) showed that a greater maximum skin wittedness occurred at the end of aerobic training in temperate conditions (22°C, 30% relative humidity), and this was further augmented by heat acclimation in a hot and humid condition (38°C, 65% relative humidity). This suggests that studies that include aerobic training in the heat acclimation/acclimatization protocols may have had their thermoregulatory effects augmented. However, as there have been few studies that have isolated the effects of heat acclimation/acclimatization from aerobic training or compared exertional vs. passive exposure to heat in heat acclimation/acclimatization protocols, it would be difficult to isolate the effects of heat acclimation/acclimatization from aerobic fitness.

Pre-exercise Cooling

The main intention of pre-exercise cooling is to lower Tc before exercise to extend heat storage capacity in hope to delay the onset of fatigue and in this review, we have observed pre-exercise cooling to be most effective in this aspect compared to the other heat mitigation strategies. For comprehensive reviews on pre-exercise cooling (see Marino, 2002; Quod et al., 2006; Duffield, 2008; Jones et al., 2012; Siegel and Laursen, 2012; Wegmann et al., 2012; Ross et al., 2013). The various pre-exercise cooling methods include cold water immersion (Booth et al., 1997; Kay et al., 1999), cold air exposure (Lee and Haymes, 1995; Cotter et al., 2001), cold vest (Arngrimsson et al., 2004; Bogerd et al., 2010), cold fluid ingestion (Lee et al., 2008; Byrne et al., 2011), and ice slurry ingestion (Siegel et al., 2010; Yeo et al., 2012).

Largely, the methods above have been shown to be effective in lowering Tc pre-exercise, which could consequently reduce thermal strain and therefore enhance endurance performance. Apart from lowering Tc pre-exercise, ice slurry ingestion has shown to increase Tc at the end of exercise. In both laboratory and field studies, Tc was higher at the end of exercise with ice slurry. In the laboratory study by Siegel et al. (2010) oesophageal temperature was higher by 0.31°C, and in the field study by Yeo et al. (2012), gastrointestinal temperature was higher by 0.4°C with the ingestion of ice slurry. Siegel et al. (2010) suggested that the ingestion of ice slurry may have affected thermoreceptors present causing a “physiologically meaningful reduction in brain temperature.” In addition, ice slurry ingestion may have potentially attenuated any afferent feedback that would have resulted in central reduction in muscle activation, allowing tolerance of a greater thermoregulatory load (Lee et al., 2010).

In addition, practitioners should consider the magnitude of pre-exercise cooling strategies being employed. Large volumes of ice slurry/cold water ingestion may blunt heat loss pathways by limiting sweat gland activity. This would reduce evaporative heat loss which may counteract to cause a greater heat storage and higher Tc during exercise which would be unfavorable (Ruddock et al., 2017). However, it should be noted that this potentially negative effect of ice slurry/cold water ingestion may be a greater concern in dry environments as compared to humid environments. In hot and humid environments, despite reductions in evaporative heat loss potential, actual evaporation may not be reduced, and ice slurry/cold water ingestion would still be beneficial in reducing body heat storage. This is due to the attainment of the maximum evaporation potential anyway, and any additional sweat generated would drip off the skin in hot and humid environments (Jay and Morris, 2018). Numerous studies also support the effectiveness of pre-exercise ice slurry/cold water ingestion in lowering Tc and demonstrate that this profile is continued during exercise (Lee et al., 2008; Siegel et al., 2010, 2012; Byrne et al., 2011; Yeo et al., 2012).

The effectiveness of pre-cooling as a strategy in altering Tc may be limited as it is mostly done acutely before exercise. As such, its benefit may not be able to be sustained throughout the exercise duration. To counteract this limitation, considerations can be made to consider per/mid-exercise cooling. Whilst not discussed in the present meta-analysis, previous reviews have shown that per/mid-exercise cooling may be as effective in enhancing exercise performance in hot environments (Bongers et al., 2015, 2017).

Fluid Ingestion

Fluid ingestion is a common strategy used to reduce thermoregulatory strain in the heat. Many studies have shown that when fluid is ingested during exercise, exercise capacity and performance are enhanced (Fallowfield et al., 1996; Cheung and McLellan, 1997; Marino et al., 2004). A more controversial issue is the optimal amount of fluid to be consumed during exercise. Two dominant viewpoints exist—the first is that athletes should prevent fluid loss of >2% body mass (Sawka et al., 1985; Montain and Coyle, 1992a; Sawka and Coyle, 1999; Casa et al., 2010), while the other recommends drinking ad libitum (Noakes, 1995; Beltrami et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2011) due to an increased prevalence of exercise associated hyponatremia, commonly referred to as water intoxication (Noakes, 1995). Even in warm conditions where sweat rates are high, the behavioral drive to ingest fluids could exceed the physiological sweat loss (Lee et al., 2011).

This review analyzed the effects of a (i) low fluid/ad libitum vs. high fluid intake and (ii) no fluid vs. high fluid intake on Tc. All participants began exercise in a euhydrated state. Dugas et al. (2009) found that ad libitum drinking while cycling replaces approximately 55% of fluid losses., while Daries et al. (2000) found that ad libitum drinking during a treadmill run replaces approximately 30% of fluid losses. Hence in this evaluation, a fluid intake trial replacing closest to ~45% of fluid losses was chosen to represent the low fluid/ad libitum condition. It should also be stated that the results in trials in which the control state was no fluid intake may have exaggerated the results of fluid ingestion seen in this meta-analysis. This is especially so when we consider that it is impractical during a competition event to avoid drinking. As such, future hydration studies should consider avoiding a “No fluid” control state.

Ideally, individuals should begin their exercise in a euhydrated state. This could be achieved by drinking 6 mL of water per kg body mass for 2–3 h pre-exercising in a hot environment (Racinais et al., 2015a). During exercise, fluid is largely loss through sweating. Sweat rates may vary depending on individual characteristics, environmental conditions and heat acclimation/acclimatization status (Cheuvront et al., 2007). Practitioners should therefore consider determining their sweat rate prior to exercising in a hot environment to determine the amount of rehydration or fluid intake that is necessary to reduce physiological strain and optimize performance, without increasing body weight. Considerations can also be made to include supplementation with sodium (Casa, 1999; Sawka et al., 2007) and glucose (von Duvillard et al., 2007; Burke et al., 2011).

Practical Implications

Logically, employing a combination of all the different heat mitigation strategies would be most beneficial in extending an athlete's heat storage capacity and in optimizing exercise performance in the heat. However, due to time and resource constraints, it may not be practical for athletes and coaches to employ all these strategies for competition. By knowing which heat mitigation strategy is most effective, an informed decision can be made. Strategies such as aerobic fitness and heat acclimation/acclimatization have to be conducted months and weeks respectively before competition in order to reap its benefits. On the other hand, strategies such as pre-exercise cooling and fluid ingestion can be done immediately before or during competition. Practicality and comfort should be the main focus when deciding which heat mitigation strategy to employ. For example, pre-exercise cooling methods such as cold water immersion may be effective in lowering Tc before exercise begins. However, it may be cumbersome to set up a cold water bath especially during outdoor field events. Furthermore, being immersed in a cold water bath may be an uncomfortable experience for some athletes, and may cool the muscles prior to the event and hence is not practical to be used prior to competition (Quod et al., 2006; Ross et al., 2013). It is noteworthy that there could be inter-individual differences when employing each of these heat mitigation strategies. Athletes and coaches are advised to experiment with these strategies during training before deciding on the appropriate strategy to employ during competition. Finally, the importance of the usage of heat mitigation strategies when competing in hot and humid environments cannot be stressed enough. From this meta-analysis, we have shown that aerobic fitness is the most effective heat mitigation strategy. However, this does not understate the importance of a combination of heat mitigation strategies, nor does it reflect that should an athlete be aerobically fit, other heat mitigation strategies are not necessary. In the 15th International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) World Championships held in Beijing (China), mean and maximal temperatures were anticipated to be 26° and 33°C respectively, with relative humidity of ~73%. Despite the expected hot and humid conditions, only 15% of athletes reported having specifically prepared for these conditions. Of these, females and athletes with previous history of exertional heat illnesses (EHI) were more likely to adopt heat mitigation strategies (Périard et al., 2017). Although <2% experienced EHI symptoms, athletes should be more aware of the potential benefits of using one or more heat mitigation strategies in the lead up to competitions in hot and humid environments. As global temperatures continue to rise, the importance of such heat mitigation strategies in enhancing performance and in reducing the likelihood of EHI cannot be understated.

Limitations

The methodology of using a meta-analysis to evaluate effectiveness of different strategies is not without limitation. Publication and language restriction bias may have affected the number of studies that could be included in the analysis. As such, care was taken to ensure to control for such biases, such as a manual tracking of review articles to ensure that studies that were relevant but that did not show up in the initial search of the databases could be included as well. The heterogeneity of the included studies was also controlled for by statistical analysis. In addition, due to the practical difficulty in blinding the participants to the heat mitigation strategy being employed, any beneficial effect arising from the placebo effect could not be eliminated.

This meta-analysis also did not include behavioral alterations that could be undertaken as a mitigation strategy against exertional heat stress. Taking regular breaks during exercise is an effective way to minimize heat strain by preventing an excessive rise of Tc and increasing exercise tolerance in the heat (Minett et al., 2011). Individuals should also avoid exercising during the hottest part of the day. Alternatively, several shorter sessions of exercise can be performed rather than having a single long session, to reduce hyperthermia, while maintaining the quality of the exercise session (Maughan and Shirreffs, 2004). When exercising in the heat, an important consideration is to ensure that the material in the clothing does not prevent the evaporation of sweat from the skin (Maughan and Shirreffs, 2004). Furthermore, black and dark-colored clothing absorb more heat and should not be worn when exercising in the heat. For a review of the thermal characteristics of clothing (see Gonzalez, 1988; Parsons, 2002). One reason for the exclusion is that there is often time pressure to complete a task or race as fast as possible and/or in certain attire that does not permit behavioral alteration during competitions. There are also few studies that looked at the effect of behavioral alterations on endurance that fulfilled our inclusion criteria, which did not allow for the calculation of an effect size to compare effectively with the other heat mitigations strategies.

Although these limitations should be accounted for, this is the first meta-analysis to compare several different heat mitigation strategies and their effects on Tc and endurance. As such, this meta-analysis could provide the information necessary to allow for more informed decision making by coaches, athletes and sports scientists during exercise in hot and/or humid environments.

Conclusion

In conclusion, aerobic fitness was found to be the most effective heat mitigation strategy, followed by heat acclimation/acclimatization, pre-exercise cooling and lastly, fluid ingestion. The similarity in ranking between the ability of each heat mitigation strategy to favorably alter Tc and affect endurance suggest that alteration of heat strain may be a key limiting factor that contributes to endurance. This analysis has practical implications for an athlete preparing for competition in the heat and also allows coaches and sport scientists to make a well-informed and objective decision when choosing which heat mitigation strategy to employ.

Statements

Author contributions

SA and PT realized the research literature. SA, PT, and JL contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

Funds received for open access publication fees were obtained from Defence Innovative Research Program Grant No. 9015102335, Ministry of Defence, Singapore.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

ArmstrongL. E.CostillD. L.FinkW. J.BassettD.HargreavesM.NishibataI.et al. (1985). Effects of dietary sodium on body and muscle potassium content during heat acclimation. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol.54, 391–397.

2

ArmstrongL. E.MareshC. M. (1991). The induction and decay of heat acclimatisation in trained athletes. Sports Med.12, 302–312.

3

ArmstrongL. E.MareshC. M.GabareeC. V.HoffmanJ. R.KavourasS. A.KenefickR. W.et al. (1997). Thermal and circulatory responses during exercise: effects of hypohydration, dehydration, and water intake. J. Appl. Physiol.82, 2028–2035. 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.6.2028

4

ArngrimssonS. A.PetittD. S.StueckM. G.JorgensenD. K.CuretonK. J. (2004). Cooling vest worn during active warm-up improves 5-km run performance in the heat. J. Appl. Physiol.96, 1867–1874. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00979.2003

5

BainA. R.JayO. (2011). Does summer in a humid continental climate elicit an acclimatization of human thermoregulatory responses?Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.111, 1197–1205. 10.1007/s00421-010-1743-9

6

BardisC. N.KavourasS. A.AdamsJ. D.GeladasN. D.PanagiotakosD. B.SidossisL. S. (2017). Prescribed drinking leads to better cycling performance than ad libitum drinking. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.49, 1244–1251. 10.1249/mss.0000000000001202

7

BarrD.ReillyT.GregsonW. (2011). The impact of different cooling modalities on the physiological responses in firefighters during strenuous work performed in high environmental temperatures. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.111, 959–967. 10.1007/s00421-010-1714-1

8

BeaudinA. E.CleggM. E.WalshM. L.WhiteM. D. (2009). Adaptation of exercise ventilation during an actively-induced hyperthermia following passive heat acclimation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol.297, R605–R614. 10.1152/ajpregu.90672.2008

9

BeltramiF. G.Hew-ButlerT.NoakesT. D. (2008). Drinking policies and exercise-associated hyponatraemia: is anyone still promoting overdrinking?Br. J. Sports Med.42:796. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.047944

10

BerggrenG.Hohwu ChristensenE. (1950). Heart rate and body temperature as indices of metabolic rate during work. Arbeitsphysiologie14, 255–260.

11

BestS.ThompsonM.CaillaudC.HolvikL.FatseasG.TammamA. (2014). Exercise-heat acclimation in young and older trained cyclists. J. Sci. Med. Sport17, 677–682. 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.10.243

12

BogerdN.PerretC.BogerdC. P.RossiR. M.DaanenH. A. (2010). The effect of pre-cooling intensity on cooling efficiency and exercise performance. J. Sports Sci.28, 771–779. 10.1080/02640411003716942

13

BongersC. C.HopmanM.EijsvogelsT. M. (2017). Cooling interventions for athletes: an overview of effectiveness, physiological mechanisms, and practical considerations. Temperature4, 60–78. 10.1080/23328940.2016.1277003

14

BongersC. C. W. G.ThijssenD. H. J.VeltmeijerM. T. W.HopmanM. T. E.EijsvogelsT. M. H. (2015). Precooling and percooling (cooling during exercise) both improve performance in the heat: a meta-analytical review. Br. J. Sports Med.49, 377–384. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092928

15

BoothJ.MarinoF.WardJ. J. (1997). Improved running performance in hot humid conditions following whole body precooling. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.29, 943–949.

16

BorensteinM.HedgesL. V.HigginsJ. P. T.RothsteinH. R. (2009). Introduction to Meta-Analysis.West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

17