- 1Department of Urology, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

- 2Centre for Advance Research, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

- 3Central Research Facility, Post Graduate Institute of Child Health, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

- 4Department of Thoracic Surgery, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, India

- 5Department of Biochemistry, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

Introduction: Early prognostication in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is essential for optimizing therapy and follow-up. Epigenetic mechanisms, particularly DNA methylation, have emerged as promising biomarkers for predicting disease outcome.

Materials and Methods: A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to evaluate the prognostic significance of promoter DNA methylation in NMIBC. Comprehensive searches of PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane Library (January 2010–October 2022) identified eligible studies. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale was used for quality assessment, and pooled hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated using random-effects models.

Results: Eleven studies with 3,065 NMIBC patients were analyzed. Promoter methylation was significantly associated with poor progression-free survival (pooled hazard ratios (HR) = 2.88; 95% CI = 2.03–4.09; p < 0.0001) and recurrence-free survival (pooled HR = 2.65; 95% CI = 1.93–3.63; p < 0.0001). Although overall survival showed pathway-specific variation (pooled HR = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.36–2.60; p = 0.94), methylation of adhesion and apoptosis-related genes exhibited the strongest associations. Subgroup analyses revealed a greater prognostic impact in Asian cohorts (p < 0.0001), suggesting regional differences in epigenetic susceptibility.

Conclusion: Promoter DNA methylation constitutes a robust prognostic biomarker for recurrence and progression in NMIBC, with stronger effects in Asian populations. Standardization of validated gene panels, assay thresholds, and cross-regional prospective validation will be essential for clinical translation. Integrating methylation-based classifiers into risk stratification models could improve individualized management and long-term outcomes in NMIBC.

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the 10th most prevalent cancer, and its cases are continuously on the rise in developed and developing countries. It ranked fourth among men and 12th among women and accounts for 0.2 million deaths worldwide (1). Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is a confined form and one of the clinically significant subtypes of bladder cancer (2). After the standard treatment with transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT) followed by intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) immunotherapy, recurrence occurs in up to 60%–70% of patients, and 10%–30% disease progression to MIBC (3–5). BCG-non-responsive NMIBC presents a challenging scenario, as treatment failure necessitates radical cystectomy, a morbid procedure with impacts on quality of life (6, 7). Despite the availability of clinicopathological risk stratification tools, such as tumor grade, stage, and multiplicity, these parameters remain insufficient to predict recurrence, progression, or overall survival (OS) (8, 9). Hence, identifying reliable molecular biomarkers that can improve prognostic precision and targeted therapy in NMIBC patients is an urgent need.

Among molecular mechanisms implicated in bladder carcinogenesis, epigenetic regulation has emerged as a crucial driver of tumor development and progression (10–12). DNA methylation is extensively studied and involves the addition of a methyl group to cytosine residues within CpG islands in gene promoters, leading to transcriptional silencing (13). In bladder cancer, tumor-suppressor genes such as RASSF1A, RUNX3, CDH13, and HOXA9 have been reported to undergo promoter hypermethylation, resulting in loss of tumor-inhibitory function (14, 15). Such methylation events contribute to cell cycle dysregulation, inhibition of apoptosis, and enhanced tumor invasiveness (16, 17). Despite multiple studies exploring individual methylation biomarkers in NMIBC, the findings remain inconsistent due to variations in sample size, patient characteristics, methodologies, and analytical approaches (18). This inconsistency highlights the need for a systematic synthesis of available evidence to clarify the prognostic utility of DNA methylation in NMIBC. Therefore, the present systematic review and meta-analysis were undertaken to comprehensively evaluate the existing literature and determine the overall prognostic significance of DNA methylation in NMIBC by quantitatively analyzing its association with key clinical outcomes, recurrence-free survival (RFS), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). This study aims to establish whether DNA methylation can serve as a reliable biomarker for patient stratification and clinical decision-making in the management of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Methods

Search strategy

We followed the recommendations established by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) group in 2020. The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews has documented its registration (ID: CRD42022376063). The selected eligible articles, published between January 2010 and October 2022, were included after a comprehensive search of PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Library databases.

Various keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, including bladder cancer, urothelial cancer, carcinoma in situ, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, low-grade bladder cancer, transitional cell carcinoma, low-risk bladder cancer, methylation, and DNA methylation, were used to search the relevant literature.

Selection and eligibility criteria of the studies

The studies were selected based on following criteria: (i) articles that were published in English in scholarly journals or periodical literature; (ii) studies whose histologic type of tumor was bladder carcinoma or NMIBC; (iii) studies that investigated the association between DNA methylation or biomarkers and survival outcomes (overall survival and recurrence-free survival) of the bladder cancer patients; (iv) articles that reported the sample size, hazard ratios, and 95% CIs. However, articles were excluded from this meta-analysis if any of the following criteria were met: i) they were primary research or studies conducted on animals; (ii) meta-analyses, systematic reviews, case reports, conference proceedings, unpublished, or ongoing research; (iii) data were unavailable or insufficient; (iv) the articles were written in a language other than English; and (v) the articles were irrelevant or overlapped with other research articles. Following the elimination of duplicates, two separate reviewers, AK and MKS, evaluated the eligibility of the studies and filtered them through their abstracts and titles. This helped us achieve a higher level of dependability. Following this, the complete texts of the articles were evaluated to see whether they met the inclusion criteria and were validated for their relevance. All of the reviewers came together and reached a decision by consensus if a dispute arose.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers, AK and MKS, independently extracted and assessed study data, while a third reviewer, VS, resolved inconsistencies. Each study was assessed for clear goals, randomization methods, blinding of interventions, and participants, determining who was eligible for the intervention, giving enough information about the intervention so that it could be repeated, effect size, details of long-term follow-up and changes that lasted, analysis of confounding variables, power analysis, the definition of all outcomes, reliable measurement tools, results that could be used to measure, and appropriate statistical analysis. First author’s last name, publication year, area, study design, sample size and age, DNA methylation/biomarkers, follow-up length, association cutoff, and survival outcomes were tallied. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale was used to measure study quality (NOS). The scale has three parts: selection (0–4 points), comparability (0–2 points), and result (0–4 points) (awarded 0–3 points). The maximum NOS score was 9; ≥6 was high-quality research.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4 (RevMan 5; The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to conduct a meta-analysis of prognostic indices such OS, RFS, and PFS The link between DNA methylation and bladder cancer outcomes was determined by pooling the hazard ratios (HRs) from the included studies, together with their associated 95% CIs. The heterogeneity of the included articles was analyzed using the Cochran’s Q test and the Higgins I2 statistic. In cases where considerable heterogeneity was indicated by the Q test (p = 0.10) or the I2-test (I2 > 50%), a random-effect model (the DerSimonian–Laird technique) was used. Other than that, the Mantel–Haenszel approach (fixed-effect model) was explored.

Results

Study selection

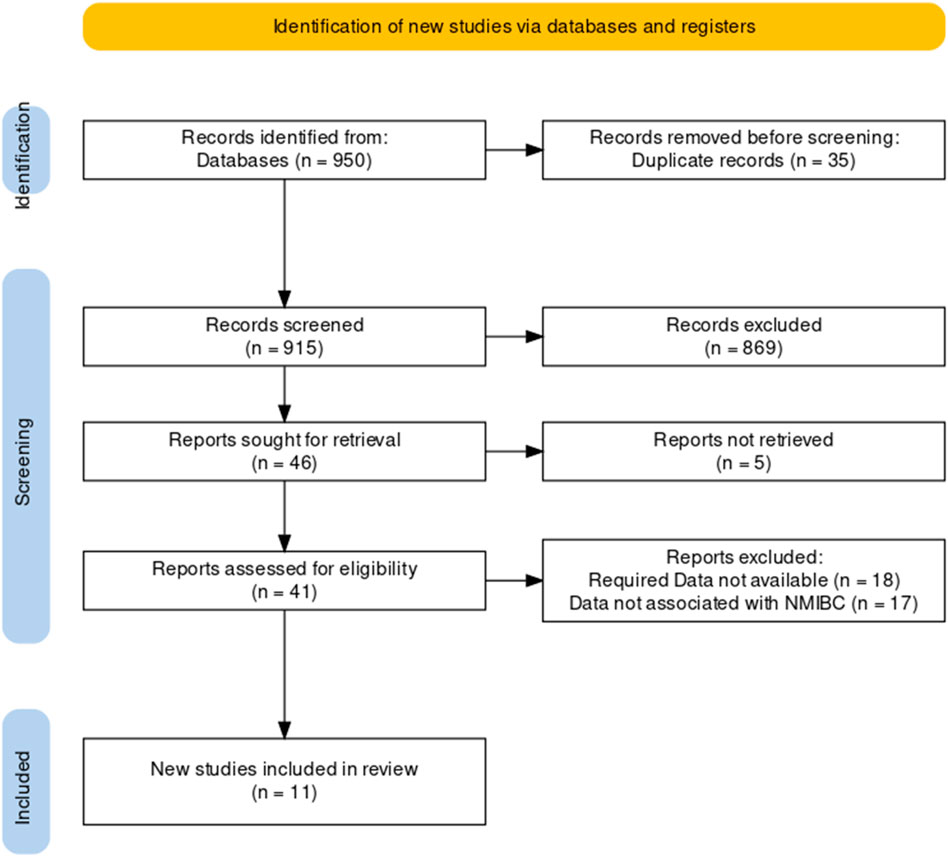

Our article search found a total of 950 articles, including duplicates and articles with incomplete data. The independent reviewer screened the articles based on their titles and abstracts, excluding 869 articles, and 5 articles were not retrieved. The full text review of the screened articles was completed, and 46 articles were assessed. As shown in Figure 1, 11 studies were considered eligible for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis (19).

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the study selection process.

Study characteristics

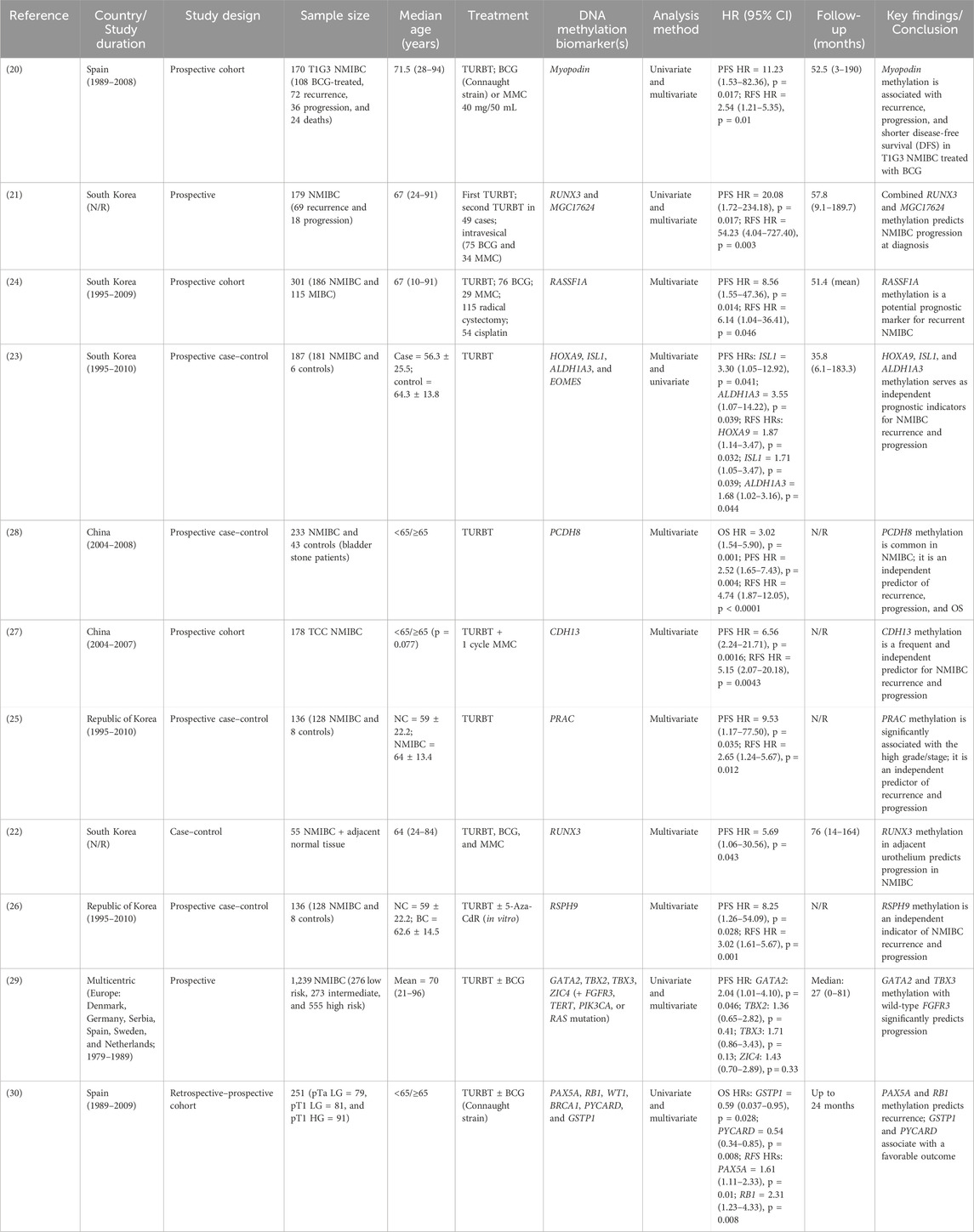

The meta-analysis includes 11 eligible articles for NMIBC with a sample size of 3,065 patients. The sample sizes range from 55 to 1,249 participants, and the participants’ ages range from 10 to 96, with follow-up periods of 3 months to 190 months. The eligible studies were considered from 2010 to 2022 (12 years) with geographic diversification and type of study focusing on NMIBC (Table 1). The prognostic outcome of the study included ten articles for PFS (20–29), nine articles on RFS (20, 21, 23–28, 30), and two articles on OS of NMIBC (28, 30). The included studies discussed various DNA methylation biomarkers for the prognosis of bladder cancer and treatment strategy.

DNA methylation biomarkers and progression-free survival (PFS) with NMIBC

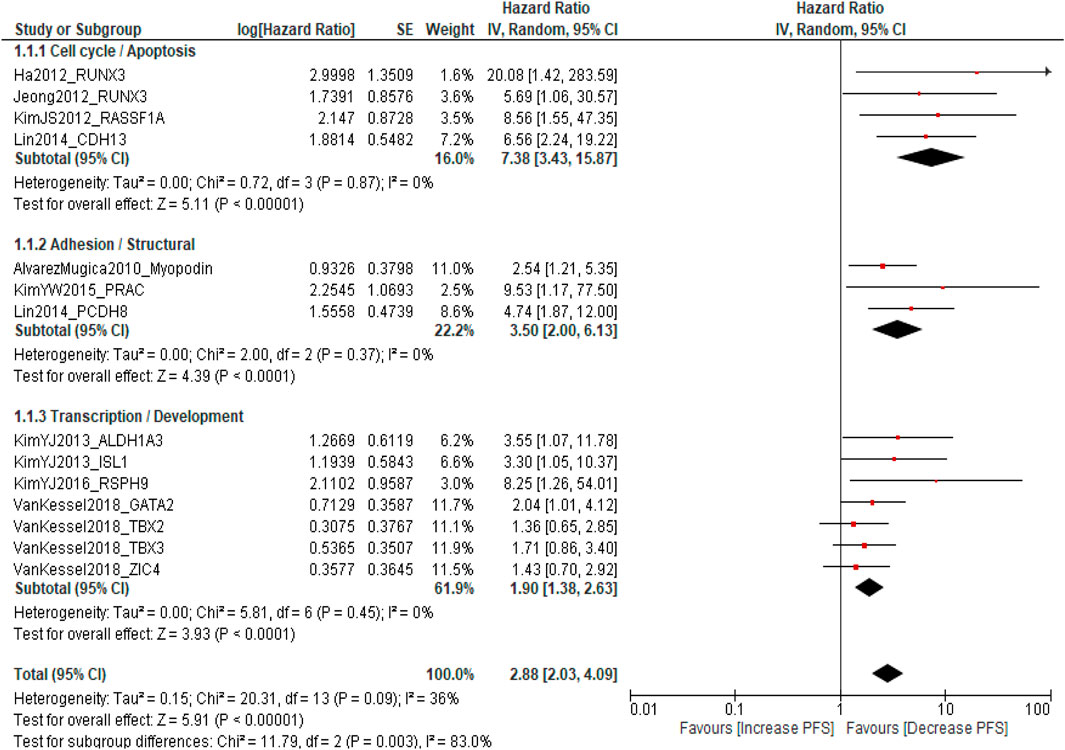

A total of ten published studies comprising 2,814 patients with NMIBC were included in the analysis evaluating the association between promoter DNA methylation and PFS. The pooled analysis demonstrated that DNA methylation was significantly associated with poorer PFS (pooled HR = 2.88; 95% CI = 2.03–4.09; p < 0.0001), indicating that patients with methylated genes had a threefold higher risk of disease progression compared with those without methylation. Overall heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 36%, p = 0.09), suggesting acceptable inter-study variability. Subgroup analysis according to molecular pathways revealed that cell cycle-/apoptosis-related genes (RUNX3, RASSF1A, and CDH13) showed the strongest association with progression (pooled HR = 7.38; 95% CI = 3.43–15.87; I2 = 0%), followed by adhesion/structural genes (Myopodin, PRAC, and PCDH8) (pooled HR = 3.50; 95% CI = 2.00–6.13; I2 = 0%) and transcription/developmental genes (ALDH1A3, ISL1, RSPH9, GATA2, TBX2, TBX3, and ZIC4) (pooled HR = 1.90; 95% CI = 1.38–2.63; I2 = 0%). A significant difference was observed among subgroups (p = 0.003), indicating pathway-specific variability in methylation effects, while sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the pooled estimates Supplementary Table S1. These findings indicate that promoter DNA methylation, particularly involving genes regulating cell cycle control, apoptosis, and cell adhesion, is consistently associated with an increased risk of progression and reduced PFS in NMIBC patients (Figure 2).

Sensitivity analysis of PFS

A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the robustness of the pooled PFS estimate. Sequential exclusion of each study from the meta-analysis yielded pooled hazard ratios ranging from 2.64 to 3.00, with moderate and stable heterogeneity (I2 = 30–44%) and consistently significant associations (all p < 0.15). Exclusive of Kim et al. (2013), ALDH1A3 and ISL1 slightly increased heterogeneity (I2 = 44%, p = 0.05) but did not materially alter the overall effect size.

These findings confirm that no individual study disproportionately influenced the pooled estimate, indicating the stability and reliability of the meta-analytic results (Supplementary Table S1).

Association between DNA methylation and recurrence-free survival (RFS)

A total of 1,771 patients with NMIBC were included in the meta-analysis evaluating the association between DNA methylation biomarkers and RFS. The pooled analysis demonstrated that DNA methylation was significantly associated with an increased risk of recurrence (pooled HR = 2.65; 95% CI = 1.93–3.63; p < 0.00001), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 49%, p = 0.04). Subgroup analysis according to molecular pathways revealed that cell cycle-/apoptosis-related genes (RUNX3, RASSF1A, CDH13, PAX5A, and RB1) showed the strongest association with recurrence (pooled HR = 3.36; 95% CI = 1.63–6.93; I2 = 70%), followed by adhesion/structural genes (Myopodin, PRAC, and PCDH8) (pooled HR = 2.69; 95% CI = 1.84–3.94; I2 = 3%) and transcription/developmental genes (HOXA9 and RSPH9) (pooled HR = 2.28; 95% CI = 1.44–3.62; I2 = 27%). A non-significant difference was observed among subgroups (p = 0.66). The findings show promoter DNA methylation of genes regulating cell cycle, apoptosis, and cell adhesion is associated with an increased recurrence risk in NMIBC (Figure 3).

![Forest plot showing hazard ratios for different studies on cell cycle, adhesion, and transcription. Subgroup analysis includes apoptosis, structural, and development categories. Hazard ratios with confidence intervals are represented with red squares and black lines, while pooled estimates are shown with diamonds. The plot suggests overall effects favor increased relapse-free survival (RFS) with a total hazard ratio of 2.65 [1.93, 3.63].](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1679974/or-19-1679974-HTML-r1/image_m/or-19-1679974-g003.jpg)

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the pooled hazard ratios for RFS according to molecular pathway subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis for recurrence-free survival

A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the pooled estimate for RFS. Sequential exclusion of each study produced pooled hazard ratios ranging from 2.43 to 3.10, with moderate and consistent heterogeneity (I2 = 32–54%) and sustained statistical significance (p ≤ 0.10). Exclusion of Ha et al. (2012), RUNX3 slightly reduced the pooled hazard ratio (HR = 2.43; 95% CI = 1.87–3.16) and heterogeneity (I2 = 32%), suggesting a minor influence of this study on inter-study variability. However, the overall direction and magnitude of association remained unchanged. These findings confirm that no individual study disproportionately influenced the meta-analytic outcome, indicating the stability and reliability of the association between promoter DNA methylation and shorter RFS in NMIBC (Supplementary Table S2).

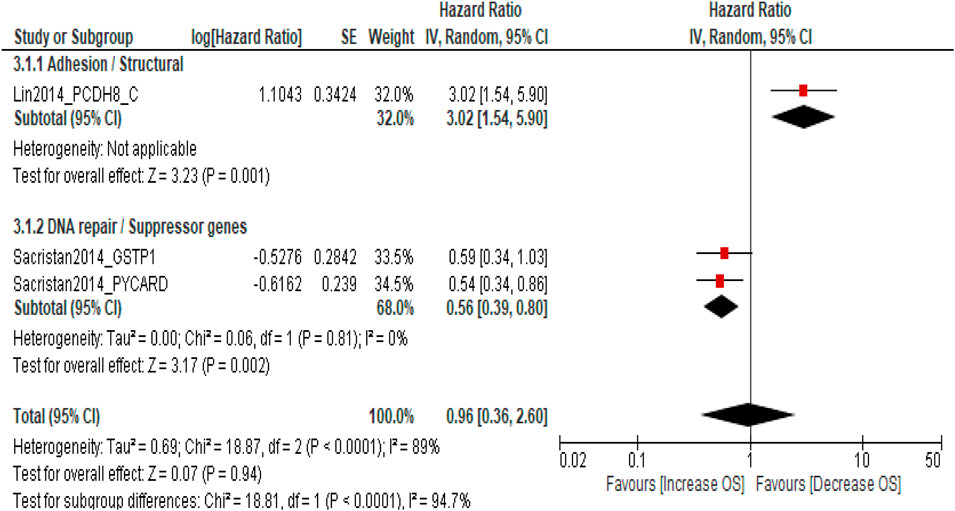

Overall survival (OS)

Three studies involving 484 patients with NMIBC evaluated the association between DNA methylation biomarkers and OS. The pooled meta-analysis showed no significant association between promoter methylation and OS (pooled HR = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.36–2.60; p = 0.94), with high heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 89%). Subgroup analysis by molecular pathway revealed contrasting trends: adhesion/structural genes (PCDH8) were associated with poorer OS (HR = 3.02; 95% CI = 1.54–5.90; p = 0.001), whereas DNA repair/suppressor genes (GSTP1 and PYCARD) were linked to a favorable prognosis (pooled HR = 0.56; 95% CI = 0.39–0.80; p = 0.002). However, the difference between subgroups was statistically significant (p < 0.0001), indicating marked pathway-specific heterogeneity. The results suggest individual gene pathways may influence OS differently; the overall pooled estimate does not demonstrate a consistent survival impact of DNA methylation in NMIBC (Figure 4). Sensitivity analysis was not performed as only three studies were available, and the pooled estimate was not statistically significant. The limited number of studies and high heterogeneity (I2 = 89%) preclude a reliable robustness assessment for this outcome.

Figure 4. Forest plot showing pooled hazard ratios (HRs) for overall survival (OS) according to molecular pathway subgroups.

Subgroup analysis by geographical region

To evaluate geographical variability in the prognostic role of DNA methylation, subgroup analyses were performed for PFS, RFS, and OS. The pooled HR for PFS was significantly higher in Asian cohorts (HR = 5.36; 95% CI = 3.40–8.45; p < 0.00001) than in European cohorts (HR = 1.78; 95% CI = 1.30–2.44; p = 0.0003), indicating a stronger prognostic effect of promoter methylation in Asian populations (p < 0.0001, I2 = 36%). A similar pattern was observed for RFS, where Asian studies (HR = 2.68; 95% CI = 2.05–3.50; p < 0.00001) demonstrated a greater effect than European studies (HR = 1.85; 95% CI = 1.35–2.54; p = 0.0001), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 54%) but consistent direction of association across regions.

In contrast, OS showed divergent results, with European cohorts suggesting a protective association for unmethylated promoters (HR = 0.56; 95% CI = 0.39–0.80; p = 0.002) and the single Asian study indicating higher mortality with methylation (HR = 3.02; 95% CI = 1.54–5.90; p = 0.001). These findings highlight region-specific differences potentially driven by genetic, environmental, and methodological factors, underscoring the need for globally representative and standardized validation of methylation biomarkers in NMIBC prognostication (Supplementary Figures S1–S3).

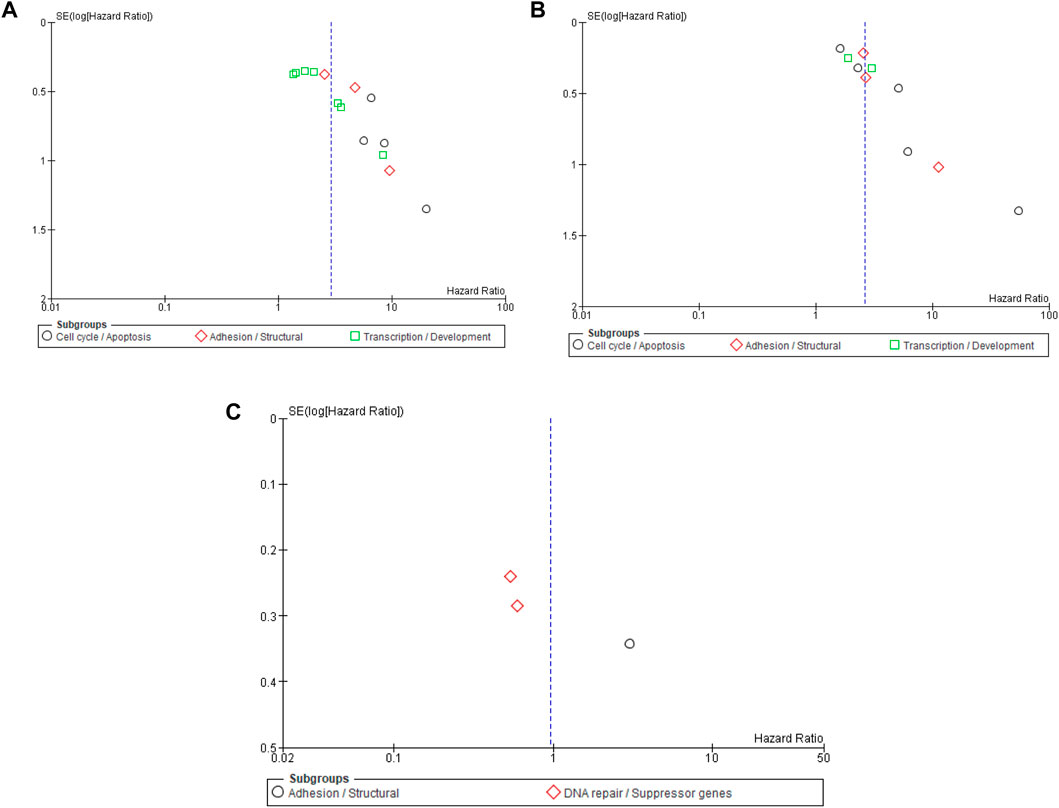

Publication bias

Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plot symmetry and Egger’s regression analysis for PFS, RFS, and OS (Figures 5A–C). Funnel plots for PFS and RFS displayed mild asymmetry, suggesting potential small-study effects, whereas the OS plot showed marked asymmetry, likely due to the limited number of included studies. Egger’s regression confirmed evidence of small-study effects for PFS (intercept = 2.73, 95% CI 1.64–3.82, p = 0.00015) and RFS (intercept = 2.48, 95% CI 1.41–3.56, p = 0.00070), indicating possible publication bias favoring studies with significant findings. Egger’s testing was not performed for OS because the small number of studies (n < 10) renders such analyses unreliable. In addition to regional influences, publication bias was assessed using geographical subgroup funnel plots for PFS, RFS, and OS. For PFS (Supplementary Figure S4), mild right-sided asymmetry was noted, with Asian studies showing higher hazard ratios and smaller standard errors, while European studies clustered symmetrically around the central axis, suggesting greater homogeneity. For RFS (Supplementary Figure S5), the distribution appeared largely symmetrical across both regions, indicating minimal small-study effects. In contrast, the OS funnel plot (Supplementary Figure S6) demonstrated notable asymmetry, mainly reflecting the limited number of studies rather than true regional bias.

Figure 5. (A) Funnel plot for the risk bias in DNA methylation biomarkers and progression-free survival (PFS). (B) Funnel plot for the risk bias in DNA methylation biomarker and recurrence-free survival (RFS). (C) Funnel plot for the risk bias in DNA methylation biomarkers and overall survival (OS).

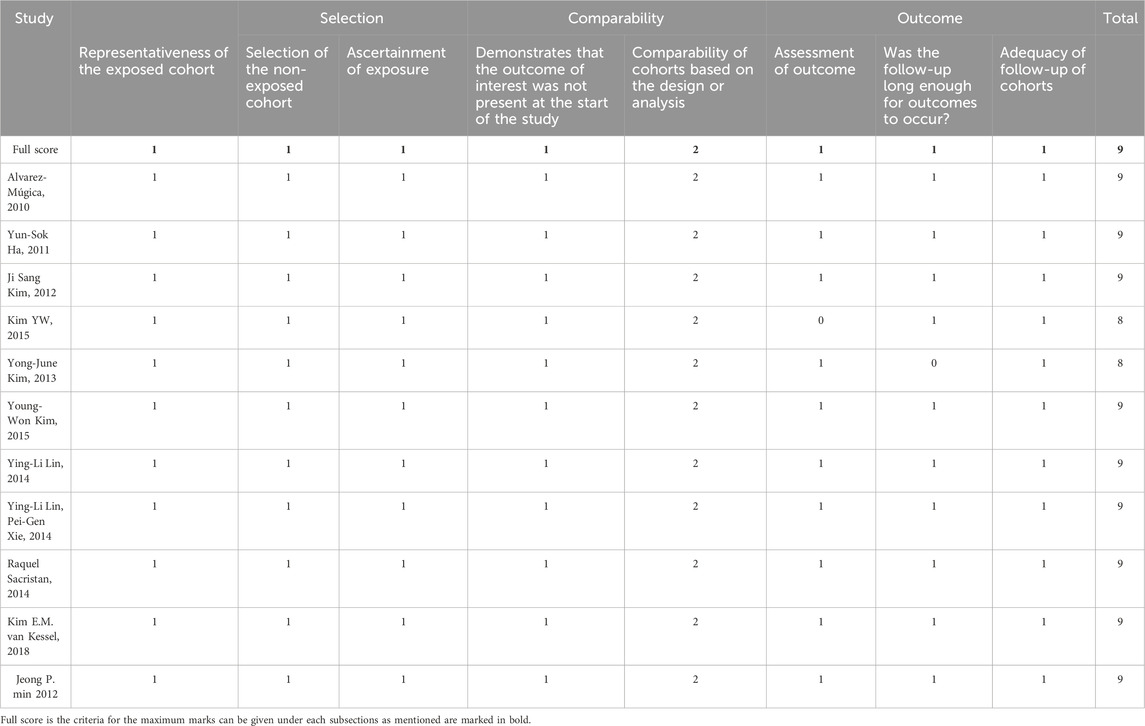

Quality assessment

The Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) was used for the quality assessment of the included studies; see Table 2. The included studies scored 7–9, which implies the quality of the eligible studies was high (31).

Discussion

This comprehensive meta-analysis, encompassing 3,065 patients from 11 studies, systematically evaluated the prognostic role of DNA methylation biomarkers in NMIBC. The findings provide robust evidence that promoter DNA methylation is significantly associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including reduced PFS and RFS, while its association with OS appears pathway-specific. These results underscore the crucial role of epigenetic dysregulation in driving NMIBC heterogeneity and highlight the clinical potential of methylation-based biomarkers for personalized risk stratification. The pooled hazard ratio for PFS (HR = 2.88; 95% CI = 2.03–4.09; p < 0.0001) and RFS (HR = 2.65; 95% CI = 1.93–3.63; p < 0.00001) demonstrates a consistent, nearly threefold increase in risk of disease progression and recurrence among patients with promoter-hypermethylated genes. These associations were particularly strong for cell cycle-/apoptosis-related genes (RUNX3, RASSF1A, and CDH13), suggesting that epigenetic silencing of key regulatory checkpoints facilitates early tumor recurrence and progression. RUNX3 methylation leads to impaired TGF-β signaling and cell cycle arrest, while RASSF1A inactivation disrupts Ras/Raf-mediated apoptosis and microtubule stability (32). Similarly, CDH13, a calcium-dependent adhesion molecule, maintains epithelial integrity, and its methylation enhances invasion and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (33). The uniform directionality across studies and subgroups (I2 = 0%) reinforces the biological validity of these associations. These data establish that DNA methylation serves as an independent, reproducible determinant of disease progression in NMIBC (20, 24, 27). Genes linked to adhesion and structural regulation (Myopodin, PRAC, and PCDH8) were also significantly associated with reduced PFS and RFS, indicating that epigenetic disruption of cell–cell adhesion and cytoskeletal architecture contributes to early tumor dissemination (34). Myopodin methylation, frequently observed in recurrent tumors, correlates with impaired actin organization and metastatic potential. Similarly, PCDH8 acts as a cell adhesion molecule and tumor suppressor, and its hypermethylation promotes detachment, invasion, and reduced survival (35). The identification of these adhesion-associated genes highlights the multifaceted role of methylation in NMIBC biology, encompassing not only proliferative signaling but also spatial and structural deregulation.

Although the pooled estimate for OS was not statistically significant (HR = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.36–2.60; p = 0.94), the subgroup analysis revealed marked pathway-specific divergence. Methylation of adhesion/structural genes such as PCDH8 correlated with poorer OS (HR = 3.02; 95% CI = 1.54–5.90; p = 0.001), consistent with their established tumor-suppressive role. Conversely, methylation of DNA repair and suppressor genes (GSTP1 and PYCARD) appeared protective (HR = 0.56; 95% CI = 0.39–0.80; p = 0.002), a paradoxical finding that may reflect compensatory methylation of stress-response genes or differing treatment sensitivities. The significant heterogeneity between pathways (p < 0.0001; I2 = 89%) underscores that the prognostic relevance of methylation is gene- and context-dependent rather than uniformly deleterious. These nuanced results echo recent genomic and epigenomic classifications of NMIBC that emphasize pathway-specific molecular evolution rather than a single linear progression model. The interplay between methylation and known oncogenic mutations such as FGFR3, TERT, and HRAS further refines our understanding of NMIBC pathogenesis. Activating FGFR3 mutations, present in up to 70% of low-grade NMIBC, are frequently accompanied by CpG methylation of cell cycle regulators, compounding proliferative signaling (36). Van Kessel et al. demonstrated that combined FGFR3 mutation and GATA2/TBX3 methylation defines a low-grade molecular subset with distinct recurrence trajectories (29). Similarly, TERT promoter mutations synergize with hypermethylation of telomere-maintenance genes (hTERT, PCDH17, TWIST1, and OTX1) to enhance immortalization and genomic instability (37, 38). The present meta-analysis reinforces that methylation signatures should be interpreted in conjunction with driver mutations to achieve optimal prognostic accuracy.

The immunological dimension of methylation-mediated tumor behavior is another critical consideration. Epigenetic silencing of antigen-presentation and interferon-responsive genes promotes immune evasion, potentially influencing BCG responsiveness. The CD3+ and CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were independently associated with reduced recurrence risk (OR = 5.8 and OR = 3.9, respectively) (39, 40). The density of CD103+CD8+ cells in the tumor–stroma interface correlated strongly with improved RFS, suggesting that methylation status shapes the immune landscape and immunotherapeutic response (41). Integrating immune markers with methylation profiling may therefore enhance risk prediction and therapeutic tailoring, particularly in the era of checkpoint inhibitors and intravesical immunotherapy (42). The emergence of liquid-biopsy methylation assays represents a transformative advance in NMIBC monitoring. Urinary methylation panels such as Bladder EpiCheck™ and AssureMDx have achieved sensitivity exceeding 80% and AUC values approaching 0.9 for recurrence detection (43, 44). More recently, assays targeting methylated GHSR, MAL, SOX1-OT, and HIST1H4F loci have demonstrated comparable diagnostic accuracy in multi-institutional validation cohorts (45). These non-invasive platforms enable real-time surveillance and complement cystoscopy, potentially reducing procedural burden while maintaining diagnostic fidelity. The strong correlation between tissue and urinary methylation profiles supports the translational relevance of our findings, suggesting that promoter hypermethylation markers could soon be integrated into clinical follow-up algorithms. Although regional subgroup analysis revealed stronger prognostic effects of promoter methylation in Asian NMIBC cohorts (HR = 5.36) than in European cohorts (HR = 1.78), this likely reflects genetic, epigenetic, and environmental differences influencing methylation susceptibility and tumor biology. These findings highlight the need for multi-ethnic validation using standardized assays for global applicability (46, 47).

The biological rationale linking methylation and clinical outcome is increasingly supported by integrated multi-omics approaches. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing and methylome clustering have delineated reproducible epigenetic subtypes of NMIBC characterized by differential BCG responses, recurrence rates, and immune microenvironment composition (48). These subtypes correspond to distinct transcriptional states driven by chromatin remodeling and histone modification, implying that DNA methylation functions as both a biomarker and a driver of tumor evolution. Our subgroup findings, which highlight pathway-specific methylation effects on progression and survival, resonate strongly with these broader integrative models. The modest funnel plot asymmetry and significant Egger’s intercepts observed for PFS and RFS (p < 0.001) suggest the presence of small-study effects, potentially reflecting publication bias toward positive findings. However, sensitivity analyses demonstrated that exclusion of any single study did not materially alter the pooled estimates, confirming the robustness of the associations. Variation in detection platforms (MSP, qMSP, and pyrosequencing), cutoff thresholds, and clinical endpoints may explain residual heterogeneity. Future studies employing standardized methylation quantification, unified definitions of recurrence and progression, and multi-gene predictive panels will be critical for translating these findings into clinically actionable tools.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrates that promoter DNA methylation emerges as a robust prognostic biomarker in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, with methylated cases showing a nearly threefold higher risk of recurrence and progression. Although overall survival effects were pathway-specific, stronger associations were observed in Asian cohorts, highlighting regional epigenetic variability. Standardization of validated gene panels, quantitative thresholds, and reproducible assays, combined with multi-ethnic prospective validation, will be critical for clinical translation. Integrating methylation-based classifiers into existing European Association of Urology and American Urological Association prognostic models may substantially improve individualized risk stratification and guide therapy selection in NMIBC.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

VS: Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AK: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft. AS: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review and editing. DS: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. MJ: Data curation, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – review and editing. AP: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. AK is thankful to the University Grants Commission for the Senior Research Fellowship [Ref No. 16–6 (December, 2017)/2018(NET/CSIR)], and MS is thankful to the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, for the award of a Senior Research Fellowship [Ref No. 3/1/2 (1)/URO/2022-NCD-II].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/or.2025.1679974/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Siegel, RL, Miller, KD, Fuchs, HE, and Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin (2022) 72(1):7–33. doi:10.3322/caac.21708

2. Cassell, A, Yunusa, B, Jalloh, M, Mbodji, MM, Diallo, A, Ndoye, M, et al. Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a review of the current trend in Africa. World J Oncol (2019) 10(3):123–31. doi:10.14740/wjon1210

3. Singh, MK, Jain, M, Shyam, H, Shankar, P, and Singh, V. Associated pathogenesis of bladder cancer and SARS-CoV-2 infection: a treatment strategy. Virusdisease (2021) 32(4):613–5. doi:10.1007/s13337-021-00742-y

4. Singh, V, Singh, MK, Jain, M, Pandey, AK, Kumar, A, and Sahu, DK. The relationship between BCG immunotherapy and oxidative stress parameters in patients with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol Semin Original Invest (2023) 41:486.e25–486.e32. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2023.09.008

5. Jain, M, Mishra, A, Singh, MK, Shyam, H, Kumar, S, Shankar, P, et al. Immunotherapeutic and their immunological aspects: current treatment strategies and agents. Natl J Maxill Surg (2022) 13(3):322–9. doi:10.4103/njms.njms_62_22

6. Claps, F, Pavan, N, Ongaro, L, Tierno, D, Grassi, G, Trombetta, C, et al. BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: current treatment landscape and novel emerging molecular targets. Int J Mol Sci (2023) 24(16):12596. doi:10.3390/ijms241612596

7. Singh, V, Singh, MK, Kumar, A, Sahu, DK, Jain, M, Pandey, AK, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers for prognosis in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Clin Biochem (2024) 2024. doi:10.1007/s12291-024-01187-y

8. Kumar, S, Singh, V, Singh, MK, and Sankhwar, SN. Management of metastatic renal cell carcinoma in a tertiary care hospital. Cureus (2023) 15(2):e35623. doi:10.7759/cureus.35623

9. Kumar, A, Singh, MK, Singh, V, Shrivastava, A, Sahu, DK, Bisht, D, et al. The role of autophagy dysregulation in low and high-grade nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: a survival analysis and clinicopathological association. Urol Oncol Semin Original Invest (2024) 42:452.e1–452.e13. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2024.07.017

10. Kumar, A, Singh, VK, Singh, V, Singh, MK, Shrivastava, A, and Sahu, DK. Evaluation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) and tumor protein P53 (TP53) as independent prognostic biomarkers in high-grade non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cureus (2024) 16(7):e65816. doi:10.7759/cureus.65816

11. Singh, MK, Singh, V, and Kumar, A. 101P survival analysis and clinicopathological correlation with molecular classification in BCG-Nonresponsive Ta-T1 bladder cancer. ESMO Open (2025) 10:104262. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.104262

12. Singh, MK, Singh, V, and Kumar, A. 285P genetic variation of the inflammatory cytokine interleukin 17 in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Ann Oncol (2024) 35:S1515. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2024.10.305

13. Jang, HS, Shin, WJ, Lee, JE, and Do, JT. CpG and Non-CpG methylation in epigenetic gene regulation and brain function. Genes (Basel) (2017) 8(6):148. doi:10.3390/genes8060148

14. Bilgrami, SM, Qureshi, SA, Pervez, S, and Abbas, F. Promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes correlates with tumor grade and invasiveness in patients with urothelial bladder cancer. SpringerPlus (2014) 3:178. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-3-178

15. Singh, V, Madeshiya, AK, Ansari, NG, Singh, MK, and Abhishek, A. CYP1A1 gene polymorphism and heavy metal analyses in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer: an explorative case-control study. Urol Oncol Semin Original Invest (2023) 41:355.e9–355.e17. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2023.04.022

16. Hervouet, E, Cheray, M, Vallette, FM, and Cartron, PF. DNA methylation and apoptosis resistance in cancer cells. Cells (2013) 2(3):545–73. doi:10.3390/cells2030545

17. Poojary, SS, and Singh, MK. Chapter 3 - tumor cell metabolism and autophagy as therapeutic targets. In: D Kumar, and S Asthana, editors. Autophagy and metabolism. Academic Press (2022). p. 73–107.

18. Oyaert, M, Van Praet, C, Delrue, C, and Speeckaert, MM. Novel urinary biomarkers for the detection of bladder cancer. Cancers (2025) 17(8):1283. doi:10.3390/cancers17081283

19. Haddaway, NR, Page, MJ, Pritchard, CC, and McGuinness, LA. PRISMA2020: an R package and shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev (2022) 18(2):e1230. doi:10.1002/cl2.1230

20. Alvarez-Mugica, M, Cebrian, V, Fernandez-Gomez, JM, Fresno, F, Escaf, S, and Sanchez-Carbayo, M. Myopodin methylation is associated with clinical outcome in patients with T1G3 bladder cancer. J Urol (2010) 184(4):1507–13. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.085

21. Ha, YS, Kim, JS, Yoon, HY, Jeong, P, Kim, TH, Yun, SJ, et al. Novel combination markers for predicting progression of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Int J Cancer (2012) 131(4):E501–7. doi:10.1002/ijc.27319

22. Jeong, P, Min, BD, Ha, YS, Song, PH, Kim, IY, Ryu, KH, et al. RUNX3 methylation in normal surrounding urothelium of patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: potential role in the prediction of tumor progression. Eur J Surg Oncol (2012) 38(11):1095–100. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2012.07.116

23. Kim, YJ, Yoon, HY, Kim, JS, Kang, HW, Min, BD, Kim, SK, et al. HOXA9, ISL1 and ALDH1A3 methylation patterns as prognostic markers for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: array-based DNA methylation and expression profiling. Int J Cancer (2013) 133(5):1135–42. doi:10.1002/ijc.28121

24. Kim, JS, Chae, Y, Ha, YS, Kim, IY, Byun, SS, Yun, SJ, et al. Ras association domain family 1A: a promising prognostic marker in recurrent nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Clin genitourinary Cancer (2012) 10(2):114–20. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2011.12.003

25. Kim, YW, Yoon, HY, Seo, SP, Lee, SK, Kang, HW, Kim, WT, et al. Clinical implications and prognostic values of prostate cancer susceptibility candidate methylation in primary nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Dis Markers (2015) 2015:1–6. doi:10.1155/2015/402963

26. Kim, YJ, Kang, HW, Seo, SP, Jang, H, Kim, T, Kim, WT, et al. RSPH9 methylation pattern as a prognostic indicator in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol (2016) 195(4):e1131. doi:10.3892/or.2015.4409

27. Ma, JG, Xie, PG, and Ma, JG. Aberrant methylation of CDH13 is a potential biomarker for predicting the recurrence and progression of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Med Sci Monitor (2014) 20, 1572–7. doi:10.12659/msm.892130

28. Lin, YL, Wang, YL, Ma, JG, and Li, WP. Clinical significance of protocadherin 8 (PCDH8) promoter methylation in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. J Exp and Clin Cancer Res (2014) 33(1):68. doi:10.1186/preaccept-1759254111327153

29. van Kessel, KEM, van der Keur, KA, Dyrskjot, L, Algaba, F, Welvaart, NYC, Beukers, W, et al. Molecular markers increase precision of the european association of urology non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer progression risk groups. Clin Cancer Res (2018) 24(7):1586–93. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-17-2719

30. Sacristan, R, Gonzalez, C, Fernández-Gómez, JM, Fresno, F, Escaf, S, and Sánchez-Carbayo, M. Molecular classification of Non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer (PTa low-grade, pT1 low-grade, and pT1 high-grade subgroups) using methylation of tumor-suppressor genes. J Mol Diagn (2014) 16(5):564–72. doi:10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.04.007

31. Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol (2010) 25(9):603–5. doi:10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

32. Lee, SH, Hyeon, DY, Yoon, SH, Jeong, JH, Han, SM, Jang, JW, et al. RUNX3 methylation drives hypoxia-induced cell proliferation and antiapoptosis in early tumorigenesis. Cell Death and Differ (2021) 28(4):1251–69. doi:10.1038/s41418-020-00647-1

33. Rubina, K, Maier, A, Klimovich, P, Sysoeva, V, Romashin, D, Semina, E, et al. T-Cadherin (CDH13) and non-coding RNAs: the crosstalk between health and disease. Int J Mol Sci (2025) 26(13):6127. doi:10.3390/ijms26136127

34. Katto, J, and Mahlknecht, U. Epigenetic regulation of cellular adhesion in cancer. Carcinogenesis (2011) 32(10):1414–8. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgr120

35. Yu, H, Jiang, X, Jiang, L, Zhou, H, Bao, J, Zhu, X, et al. Protocadherin 8 (PCDH8) inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Med Sci Monitor (2020) 26:e920665. doi:10.12659/msm.920665

36. Noeraparast, M, Krajina, K, Pichler, R, Niedersüß-Beke, D, Shariat, SF, Grunwald, V, et al. FGFR3 alterations in bladder cancer: sensitivity and resistance to targeted therapies. Cancer Commun (London, England) (2024) 44(10):1189–208. doi:10.1002/cac2.12602

37. Chiba, K, Lorbeer, FK, Shain, AH, McSwiggen, DT, Schruf, E, Oh, A, et al. Mutations in the promoter of the telomerase gene TERT contribute to tumorigenesis by a two-step mechanism. Science (2017) 357(6358):1416–20. doi:10.1126/science.aao0535

38. Heidenreich, B, and Kumar, R. TERT promoter mutations in telomere biology. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res (2017) 771:15–31. doi:10.1016/j.mrrev.2016.11.002

39. Gabrielson, A, Wu, Y, Wang, H, Jiang, J, Kallakury, B, Gatalica, Z, et al. Intratumoral CD3 and CD8 T-cell densities associated with relapse-free survival in HCC. Cancer Immunol Res (2016) 4(5):419–30. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.cir-15-0110

40. Wang, B, Wu, S, Zeng, H, Liu, Z, Dong, W, He, W, et al. CD103+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes predict a favorable prognosis in urothelial cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol (2015) 194(2):556–62. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2015.02.2941

41. Hewavisenti, R, Ferguson, A, Wang, K, Jones, D, Gebhardt, T, Edwards, J, et al. CD103+ tumor-resident CD8+ T cell numbers underlie improved patient survival in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer (2020) 8(1):e000452. doi:10.1136/jitc-2019-000452

42. Ke, HL, Lin, J, Ye, Y, Wu, WJ, Lin, HH, Wei, H, et al. Genetic variations in glutathione pathway genes predict cancer recurrence in patients treated with transurethral resection and bacillus calmette-guerin instillation for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Ann Surg Oncol (2015) 22(12):4104–10. doi:10.1245/s10434-015-4431-5

43. Witjes, JA, Morote, J, Cornel, EB, Gakis, G, van Valenberg, FJP, Lozano, F, et al. Performance of the bladder EpiCheck methylation test for patients under surveillance for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: results of a multicenter, prospective, blinded clinical trial. Eur Urol Oncol (2018) 1(4):307–13. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2018.06.011

44. Ferro, M, La Civita, E, Liotti, A, Cennamo, M, Tortora, F, Buonerba, C, et al. Liquid biopsy biomarkers in urine: a route towards molecular diagnosis and personalized medicine of bladder cancer. J personalized Med (2021) 11(3):237. doi:10.3390/jpm11030237

45. Beijert, IJ, van den Burgt, Y, Hentschel, AE, Bosschieter, J, Kauer, PC, Lissenberg-Witte, BI, et al. Bladder cancer detection by urinary methylation markers GHSR/MAL: a validation study. World J Urol (2024) 42(1):578. doi:10.1007/s00345-024-05287-5

46. Kim, E, Zucconi, BE, Wu, M, Nocco, SE, Meyers, DJ, McGee, JS, et al. MITF expression predicts therapeutic vulnerability to p300 inhibition in human melanoma. Cancer Res (2019) 79(10):2649–61. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-18-2331

47. Weeber, F, Ooft, SN, Dijkstra, KK, and Voest, EE. Tumor organoids as a pre-clinical cancer model for drug discovery. Cell Chem Biol (2017) 24(9):1092–100. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.06.012

Keywords: bladder cancer, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, prognostic markers, DNA methylation biomarkers, predictive factor

Citation: Singh V, Singh MK, Kumar A, Shrivastava A, Sahu DK, Jain M and Pandey AK (2025) DNA methylation as prognostic factors in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol. Rev. 19:1679974. doi: 10.3389/or.2025.1679974

Received: 05 August 2025; Accepted: 31 October 2025;

Published: 25 November 2025.

Edited by:

Luca Guarnera, Policlinico Tor Vergata, ItalyReviewed by:

Mounia Bensaid, Hôpital, MoroccoHina Sultana, University of North Carolina System, United States

Copyright © 2025 Singh, Singh, Kumar, Shrivastava, Sahu, Jain and Pandey. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vishwajeet Singh, ZHJ2aXNod2FqZWV0NjhAZ21haWwuY29t

†These authors contributed equally and shared second authorship

Vishwajeet Singh

Vishwajeet Singh Mukul Kumar Singh

Mukul Kumar Singh Anil Kumar

Anil Kumar Ashutosh Shrivastava

Ashutosh Shrivastava Dinesh Kumar Sahu

Dinesh Kumar Sahu Mayank Jain

Mayank Jain Anuj Kumar Pandey

Anuj Kumar Pandey