- 1Department of Architectural Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Hail, Hail, Saudi Arabia

- 2Department of Architectural Engineering, University of Hail, Ha’il, Hail, Saudi Arabia

- 3Department of Architectural Engineering, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia

- 4College of Engineering, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia

- 5Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan, Egypt

Introduction: This study investigates the evolving role of university campuses in driving urban and social development, with a specific focus on Hail University in Saudi Arabia. It explores how peripheral higher education institutions can act as urban anchors that stimulate economic growth, community integration, and spatial regeneration. Particular emphasis is placed on the latent potential of campus-adjacent commercial structures—such as a hotel and shopping center—to contribute to urban sustainability and social engagement.

Methods: The research employed a mixed-methods approach, conducted during the academic year 2022–2023. Data were collected from 1,460 participants, including 292 members of the local community and 1,168 university-affiliated individuals (students, faculty, and staff). Methods included direct observational fieldwork, two structured online surveys, and semi-structured interviews. The study examined perceptions across four key dimensions: urban management, space engagement, social activities, and investment opportunities.

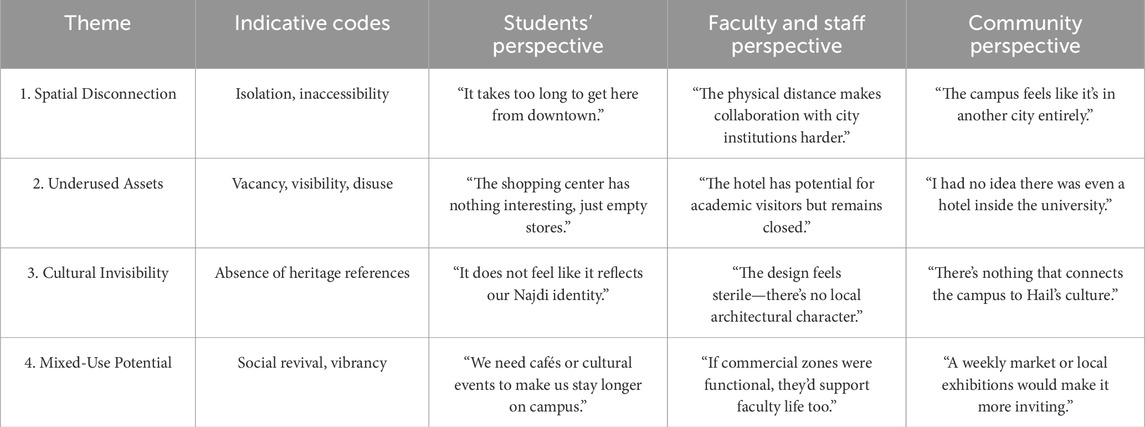

Results: Findings reveal a pronounced spatial disconnection between the university and the surrounding urban fabric, contributing to underutilization of the hotel and shopping center and limiting campus vibrancy. While stakeholders expressed interest in social engagement and improved facilities, physical isolation, weak internal connectivity, and a lack of cultural integration were cited as barriers. Statistical analysis confirmed significant variation in perceptions across stakeholder groups, and thematic coding of interviews revealed four dominant concerns: disconnection, asset underuse, cultural invisibility, and latent mixed-use potential.

Discussion and Conclusions: The study concludes with strategic recommendations to reposition peripheral university campuses as sustainable urban anchors. It proposes design, policy, and governance interventions to improve campus connectivity, activate underused commercial assets, and embed universities more effectively within local development agendas. The research contributes a conceptual model—Peripheral Campus Urban Anchoring—which may inform urban development strategies in similarly situated universities across the region, supporting Saudi Arabia’s broader Vision 2030 goals.

1 Introduction

Sustainability challenges in university campuses are a significant concern for many institutions worldwide. Universities play a pivotal role in promoting sustainability in their communities, and are expected to model environmentally conscious behavior. They also play a critical role in the development and growth of cities. As hubs of innovation, education, and research, universities can spur economic development, attract new businesses and industries, and create new opportunities for members of the surrounding community.

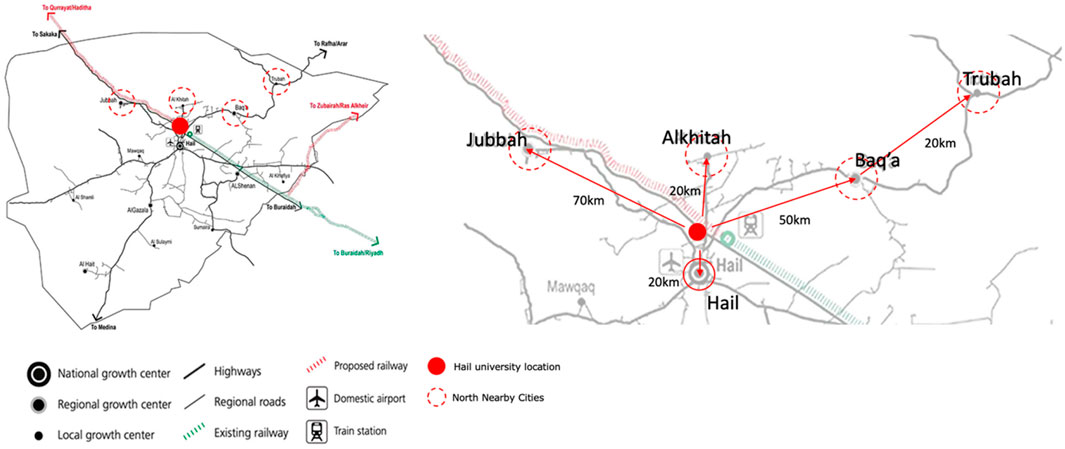

To maximize the potential benefits of university campuses and ensure sustainable growth, it’s important to consider connectivity and investment solutions not only at the campus level, but also at the community level in which the university resides. When compared to other countries, Saudi Arabia’s higher education system is relatively young. As of 2017, only five universities in the Kingdom existed more than 50 years ago, while from 1960 to 2000, the Kingdom was known to have only eight public universities, all of which were founded between 1957 and 1998. Today, however, the country is home to 28 public universities (Alghamdi, 2018). This rapid expansion of public universities in the Kingdom is evidence of the government’s efforts to increase access to higher education and promote economic growth through knowledge-based industries. The increased number of public universities in Saudi Arabia has also led to a significant increase in the number of Saudi students pursuing higher education, boosted the migration and growth of small cities, and providing numerous alternatives for Saudis within the country. More importantly, this effort to increase educational infrastructure serves to encourage diverse investment throughout the country, encourages urban renewal, and enhances the quality of life of the residents of small cities, such as the focus of this study, Hail City and its university campus.

This rapid expansion can be attributed to the actions of the Saudi Arabian government, which adopted a long-term strategic plan for higher education. The “Saudi 2030 Vision” strategic plan has sought to establish a “knowledge society” in the Kingdom by investing in Saudis, through investments in secondary, vocational, technical, and higher education. The plan aims to increase the number of Saudi students studying abroad, improve the quality of domestic education, develop sustainable educational campuses, and enhance research and innovation in various fields (Siambi, 2021). Underlying goals of the strategic include diversifying the economy and contributing to the country’s growth and development.

To determine the potential of the Hail University campus, the study will investigate residents’ perspectives regarding the campus based on four attributes of sustainable urban development: urban management, space engagement, social activities, and investment opportunities. To collect this data, we will: (1) identify local community members (social actors) and gather their opinions and feedback on campus. This data will provide valuable insights into how the campus can be further developed to meet residents’ needs and expectations, ultimately contributing to its overall sustainability and success. (2) The perceptions of faculty, staff, and the student community (daily actors) will be gathered to comprehensively understand the campus environment and identify areas for improvement. By incorporating feedback from social and daily actors, we can create a more inclusive and sustainable campus that meets the needs of all stakeholders. (3) The study will explore the connectivity and investment prospects for Hail University by developing an understanding of the campus location, existing hotel and shopping center structures in the area, and potential partnerships with local businesses to enhance the overall campus experience.

By strategically leveraging these resources, Hail University can strengthen its position as a hub for education and community engagement in the region. Thus, the study aims to provide Hail University and others with context recommendations to improve campus urban sustainability practices as well as to share potential investment opportunities and urban connectivity solutions that could benefit other nearby towns and cities within the region.

2 Literature review

The development of university campuses is an area of great interest, given the increasing importance of universities as economic and social anchors in urban areas. The literature related to sustainable university campus development has explored a variety of topics related to the greening of higher educational institutions. These topics include issues of campus urban design, urban forestry, energy efficiency, waste management, green infrastructure, transportation and food systems, student engagement, and educational programs (Leal Filho, 2015). The need for universities to become more sustainable is increasingly urgent, and institutions have begun to develop and implement a variety of innovative initiatives to address environmental and social issues on campuses (Abubakar et al., 2016; Shuqin et al., 2019). Research into these initiatives, as well as analyses of the various challenges and opportunities for university sustainability, has been ongoing for many years (Cole and Wright, 2003). Therefore, this section focuses on three things: exploring key concepts and drivers of urban development in university campuses, exploring the challenges and opportunities associated with urban development in university campuses, and identifying the previously deployed strategies that have been used to promote sustainable urban development.

Universities have traditionally played a significant role in the economic, social, and cultural development of urban areas (den Heijer and Curvelo Magdaniel, 2018; Genta et al., 2022). Universities are sources of innovation, knowledge, and intellectual capital, each of which can contribute to economic growth and job creation. Universities also attract a diverse student population, which can stimulate cultural and social activities in their neighborhoods, and contribute to the vibrancy of their surrounding urban areas. Furthermore, universities can function as catalysts for urban regeneration and renewal for cities, helping to revitalize neighborhoods in decline, and creating new opportunities for residents (Schewenius et al., 2017; Popov and Syrova, 2021). With significant impacts on the natural and built environments, university campuses are becoming complex environments. As the world’s population continues to urbanize, universities are becoming more urbanized too. Therefore, it is crucial that universities take on the responsibility of creating urban environments that are economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable.

Studies have emphasized universities’ contributions to urban economies and cultural life and researchers have faced new demands from critical urban literature to study how peripheral campuses affect uneven spatial development (Banks et al., 2020). Critical Urbanism Theory provides a framework for analyzing both the contributions of universities and their spatial location, as well as their governance structures and investment patterns (Simone, 2022), which sustain socio-spatial fragmentation in marginal or semi-rural territories such as Hail. This research expands upon existing debates by analyzing how Hail University’s distance from the city center affects both the daily life of residents and the underutilization of its infrastructure.

Such a concept (Critical Urbanism Theory) refers to universities that promote sustainable development in the built environment. The goals of the theory are to minimize negative impacts on the natural environment, conserve resources, and create a healthy and productive environment for the university community (Bassett, 2015). Sustainable university campuses take an integrated approach that incorporates economic, social, and environmental considerations. Because of its high-density buildings, large population, and full-featured facilities, the typical university campus may be considered a “small-scale city” and typically plays an important role in the city (Guerrieri et al., 2019; Wibowo, 2019). Currently, there is a growing focus on the environmental impact of university campuses (Srivanit and Hokao, 2013). They are hubs of innovation, research, sustainability initiatives, and a hub for new ideas related to urban renewal strategies (Brinkhurst et al., 2011). Thus, a crucial aspect of creating a sustainable university is considering the impact of the university on its surrounding built environment.

University campuses worldwide are increasingly incorporating investments in retail offerings such as shopping centers, hotels, and marketplaces to increase social engagement in their communities (Mohrman et al., 2008; Perera et al., 2016). Theoretical research indicates that students and staff base their evaluations of university quality and satisfaction on their combined assessment of the university experience. Place-based ‘identity theory’ and ‘satisfaction alignment’ models indicate that universities that integrate well into their surrounding urban environments through accessible infrastructure, social amenities, and economic relationships develop ‘dual attachment’ between the university’s campus and the surrounding city. The connection between university and city has an impact on personal assessments of quality of life, institutional loyalty, and each individual’s sense of belonging. The research by Gümüş et al. (2020) demonstrates that urban vibrancy together with mobility options and neighborhood cohesion directly impact student satisfaction at academic institutions, particularly in peripheral or suburban locations. The planning of campuses must take into account city dynamics, because it is the dynamics of a city that most directly determine user satisfaction. This research investigates how Hail University’s physical layout and its social connections with the City of Hail affect both community members’ views of the university as well as university users’ level of satisfaction.

This approach not only strengthens the university’s relationship with its surroundings, but it also creates new opportunities for local businesses and residents. By integrating commercial ventures into their campuses, universities can provide a more vibrant and dynamic environment for their students and faculty. These new developments offer a range of amenities and services that can enhance the quality of life on campus, from shopping and dining options to entertainment venues and recreational facilities. In addition, these investments can help to generate revenue for the university, which can be used to support academic programs and research initiatives. At the same time, integrated commercial ventures can also serve as catalysts for economic growth in the surrounding community, providing job opportunities and driving local development (Leon et al., 2018). Ultimately, this trend toward commercialization represents an exciting opportunity for universities to engage with their communities in new and innovative ways, while also fostering greater collaboration between academia and industry.

The concept of peripheral urbanization, which Caldeira (2017) and Ganapati (2021) explored, describes how cities expand through unplanned development in areas on the periphery, peripheral areas without proper infrastructure or integration into the urban ‘center’. The spatial development patterns of Hail University and similar institutions create fragmented urban environments. The placement of peripheral campuses outside city centers leads to the formation of isolated enclaves instead of integrated urban spaces. The present study assists in addressing existing knowledge gaps about peripheral campuses by using empirical methods to study how spatial separation impacts both community involvement and internal social unity.

As a result of changing societal values, universities are taking steps to reduce their carbon footprint by implementing sustainable practices such as using renewable energy sources (solar, wind, etc.), promoting waste reduction and recycling, and encouraging the use of within campus public transportation or biking (Freestone et al., 2021; Mallen et al., 2020). For example, Wesbrook Village is a multi-use neighborhood developed by the University of British Columbia (UBC). The project consists of a mix of residential, commercial, and recreational space. The university has also worked with local businesses to develop a vibrant retail community, which has increased social engagement on campus (Brenman, 2013; Girling, 2015). Another example, this one in Europe, the University of Warwick has constructed the Warwick Retail Park, a shopping center with various shops, restaurants, and leisure facilities. The university has also partnered with a local hotel chain to provide visitors with lodging, further encouraging social engagement on campus (Dyson, 2004). These efforts not only benefited the environment, they also contributed to the wellbeing of the campus community. They promoted sustainable practices, contributed to the local economy, promoted local procurement, and enhanced the campus experience, among other outcomes.

According to Stacey Swearingen White (2014), campus sustainability plans in the US address various topics, reflecting the innovative approaches to sustainability of colleges and universities. These plans focus on operational elements, such as greenhouse gas emissions, waste reduction, recycling, and transportation. Academic topics are also crucial, but degree programs and coursework are more prevalent. Some schools promote a “living laboratory” approach, integrating teaching and research efforts through campus systems. Community engagement and regional considerations contribute to these plans.

There are several drivers of urban development on university campuses. One of the main drivers, according to Magdaniel (2013), is the need to accommodate the growing demand for higher education. As the number of students attending universities continues to increase, universities are expanding their physical infrastructure to meet this demand. This expansion can lead to the construction of new buildings, provision of new services and new amenities, all of which can contribute to the development of urban areas. A complex interplay of environmental responsibility, educational opportunity, social concern, cost-effectiveness, reputation building, compliance, alumni engagement, research potential, and global collaboration drives the desire to create a more sustainable campus. Universities contribute to their immediate community and set an example for future generations by prioritizing sustainability in urban development (Popov and Syrova, 2021; Mohammed et al., 2022). Also, universities are increasingly adopting sustainable practices, such as green building design, energy efficiency, and waste reduction, which can have a positive impact on the environment and contribute to the development of sustainable urban areas (Mallen et al., 2020). However, Bolshakov (2019) stated that such an expansion to campuses comes with many challenges; while keeping sustainable approaches in mind in the early stages of development can result in long-term benefits, they may be costly to implement.

One of the challenges of university-driven sustainable development, argues Thaise Way (2016), is the need to balance the competing demands of various stakeholders, such as students, faculty, staff, and local communities. In this context, a case study related to student satisfaction in Turkey demonstrates that the level of satisfaction of students’quality of life develops through student perceptions of city infrastructure, accessibility, and urban amenities. The authors demonstrate that city–university integration strongly affects student educational and social experiences, especially in mid-sized and peripheral cities (Yazgan, 2022). The research objectives of our study align with this insight because we examine how Hail’s urban environment affects students’ perceptions of university structure, value, and functionality.

The recently proposed campus-city interface theories demonstrate that successful integration depends more on permeability and accessibility and spatial legibility than on proximity (MacKinnon et al., 2022; Kleibert et al., 2021; Melhuish, 2022). The theories indicate that universities need to operate as ‘anchor institutions’ in order to drive regional development, particularly in cities lacking other economic powerhouses. The Hail case study demonstrates how the underutilization of facilities, including the shopping center and hotel, indicates a general mismatch between campus resources and regional development requirements.

Thus, stakeholder engagement is crucial in ensuring that the needs and interests of all parties are considered in the planning and development of university campuses. Furthermore, effective stakeholder engagement can also lead to the creation of a more inclusive and sustainable campus environment that benefits everyone (Mohammed and Ukai, 2022). It is therefore important for universities to prioritize stakeholder engagement in their decision-making processes.

Another challenge is the potential for gentrification and displacement of residents. As university campuses expand, they may displace existing residents, leading to the loss of affordable housing and the disruption of communities (Marrone et al., 2018). Therefore, universities must be mindful of the impact of their development on the surrounding communities and work to mitigate these impacts.

3 Methodology

Observation techniques are systematic and structured methods for gathering information about people, objects, events, or phenomena by directly observing and recording their behavior, interactions, and characteristics (Lofland, 2022). Thus, observation techniques entail carefully observing and documenting behaviors, actions, and events in their natural environments. They can provide valuable insights, particularly when researchers are attempting to comprehend real-time behaviors, contexts, and dynamics (Farid, 2022).

This study’s methodology and design are framed by a review of the main body of literature that defines sustainable university campuses. The primary examination of the study objectives is divided into two phases of quantitative evaluation. The first phase is an evaluation of the campus location and the opportunity to develop the existing investments (the shopping center and hotel) based on the following attributes: management (using indicators such as vision, policy, planning, and commitments), engagement (using indicators such as attitude, knowledge, awareness, and willingness to change), and urban settings (using indicators such as location, physical accessibility, flexibility, and space utilization). The second phase is a two themed, analysis-based online survey administered on the target local community, a urvey that is developed based on the findings of the first phase evaluation. This phase is supported by the survey deployed to the Hail community’s daily users (faculty, staff, and students), gathering information about their thoughts, perspectives, and experiences in relation to the research objectives. In this phase we deployed unstructured observation. This approach allowed the researchers to be more flexible, able to note a broader range of behaviors and interactions without the limitation of predefined categories.

3.1 Hail campus as a case study

Hail University is an institution endowed with a large land area, an area of ten square kilometers, of which the university currently only uses 39%. To allow for the provision of constructive insights and suggestions, the study only collected insights regarding the campus location in relation to the city and the existing opportunities as potential sustainable investments for the Hail campus. Consequently, the hotel and shopping center structures are used as case opportunities to illustrate how sustainable and urban development strategies can improve the quality of work/education and social/communal engagement on campus, as well as to provide the administrative staff of Hail University with an opportunity to invest in urban development alternatives, as these cases may have a higher reinvestment potential.

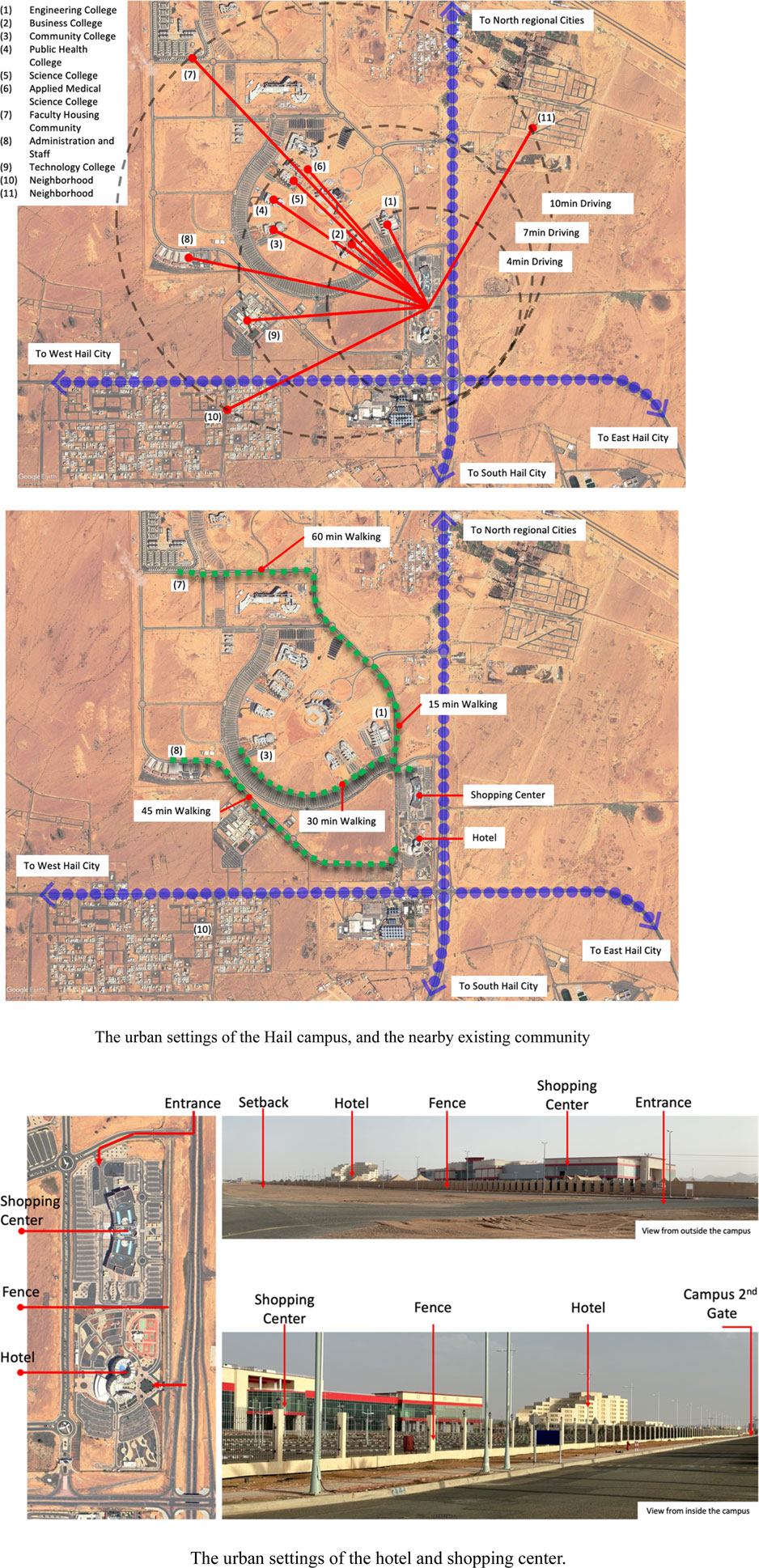

The multi-scale spatial mapping of Hail University and its surrounding urban context shows that the campus is geographically isolated from the city center, which is more than 16 km away and is also isolated from the nearest established residential clusters, which are approximately 10 km away (Figure 1). The urban perimeter of Hail highlights the peripheral nature of the campus and the lack of direct urban continuity. This spatial detachment supports previous critiques about limited accessibility and reduced social integration between the university and the city fabric.

Figure 1. Hail University campus location within the city and the hotel and shopping center structures.

While the emphasis of the study is focused on the urban settings and social activates of the campus proper, we believe that including the hotel and the shopping center within the scope of the study provides a vital discussion opportunity and is fundamental for two reasons. First, the hotel is situated in a rural area and is within the boundaries of the Hail campus, separating it from Hail city’s urban context. Furthermore, the hotel is the region’s only five-star establishment, making it a significant accommodation landmark. However, due to its remote location from the city’s urban core, the hotel experiences low occupancy, which is attributed to the general lack of urban activities in the surrounding area. This is arguably due to the hotel’s 32 km distance (28min drive) from Hail International Airport, and 16 km distance (18min drive) from Hail’s city center. This distance is considered ‘far away’ for the mid-city Hail residents. This perception is exacerbated by the presence of decent hotel alternatives within the city’s more densely populated urban areas. Second, the shopping center is a pre-existing structure, located only 150m from the hotel. While this is true, several issues arise related to the shopping center, including its existing fencing and its lack of a direct connection with the hotel. Also, the shopping center is a relatively isolated structure within the campus, having limited accessibility, and lacks urban and greenery features. As a result, the shopping center is bounded and has seen little investment due to its remote location, lack of benefit from the hotel’s guests, and its lack of direct access from inside the campus.

Although the goal of the study does not specifically include examining these two cases in depth, part of the study’s main objectives do include developing an understanding of the campus and collecting various actors’ opinions regarding the campus and how they perceive these two prominent proximate structures. The study aims to drive the discussion of how to prudently incorporate the two structures into campus life. The study also aims to explore sustainable urban solutions that incorporate the two structures, offering strategic investment opportunities for the Hail University administration to foster a thriving social life within the campus.

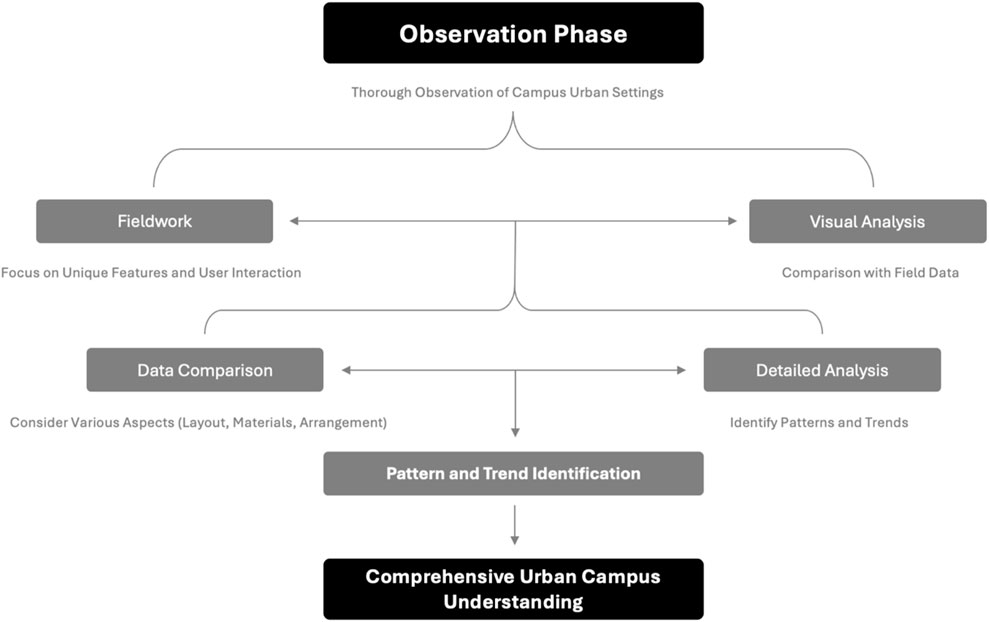

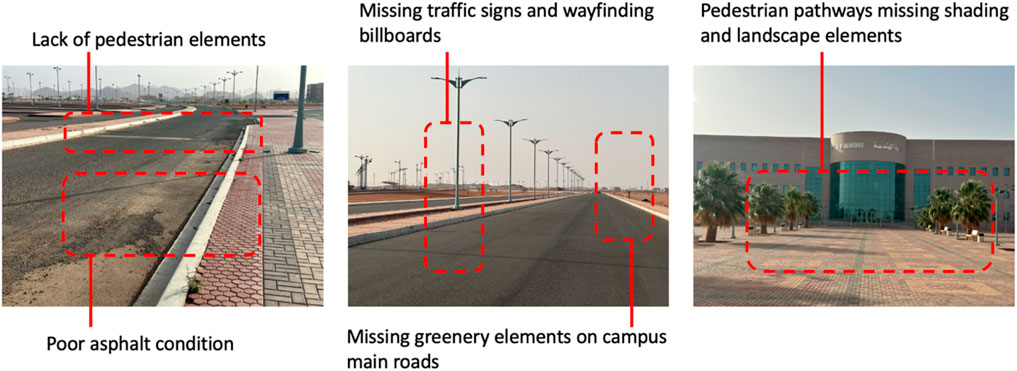

3.2 Observation

The process of collecting data for this study involved thorough observation of the campus’s urban settings, which was achieved through fieldwork and visual analysis. During the observation, particular attention was paid to identifying unique features and design elements present in the campus architecture and how daily users interact with campus facilities. The observation phase made use of a visual urban audit framework proposed by Lofland (2022), which considers walkability, green infrastructure, shading, signage, spatial connectivity, and accessibility. Considering these perspectives provides a structured and repeatable approach. The framework also considers aspects of the built environment, such as the campus layout, the materials used in construction, and the arrangement of different architectural elements. The objective is to comprehensively understand the urban campus settings by employing a thoughtful data collection and analysis approach.

Observations took place during four consecutive weekdays from 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. to record peak and off-peak activity across different parts of the campus. The observers employed standardized checklists and spatial mapping tools to record recurring behavioral patterns, accessibility constraints, user densities, and spatial interactions in both open and enclosed environments. The data collection used structured templates, which enabled pattern recognition and coding during the analysis phase. The observed data were then compared with the fieldwork to gain a comprehensive understanding of the campus’s architectural characteristics. Following the observation phase, the data were analyzed to identify patterns and trends (Figure 2).

3.3 Fieldwork and visual analysis

The conduct of visual analysis is a crucial step in developing an understanding of the campus’s urban settings and enables the triangulation of the data collected during the observation phase, enriching our understanding of the campus’s urban fabric. This visual analysis process entails a careful and detailed examination of the architecture through various visual tools, such as photography or digital rendering. These methods allows the study to capture and analyze the formal qualities, materials, layout, and patterns present in the campus design. By closely scrutinizing these visual aspects, we gain valuable insights into how the campus buildings interact with their surrounding environment, neighboring structures, and both the inner and outer spaces. This analysis sheds light on the campus’s overall integration with its surroundings and helps to understand the spatial relationships between different buildings and their surroundings. Through fieldwork and visual analysis, we can better comprehend the campus’s design principles and the impact of its settings on the overall urban context.

3.4 Survey

In surveys, information is gathered from a sample of people using forms and online polls. Surveys are frequently used in social science research because they can produce both quantitative and qualitative data (Adhya, 2008). Quantitative data provide numerical information that can be analyzed statistically, while qualitative data provide more detailed and subjective insights into people’s opinions and experiences (Raikhel and Zobova, 2022). Surveys are an efficient way to collect data from a large number of people, and the study’s methodology ensured that the sample was representative of the population studied.

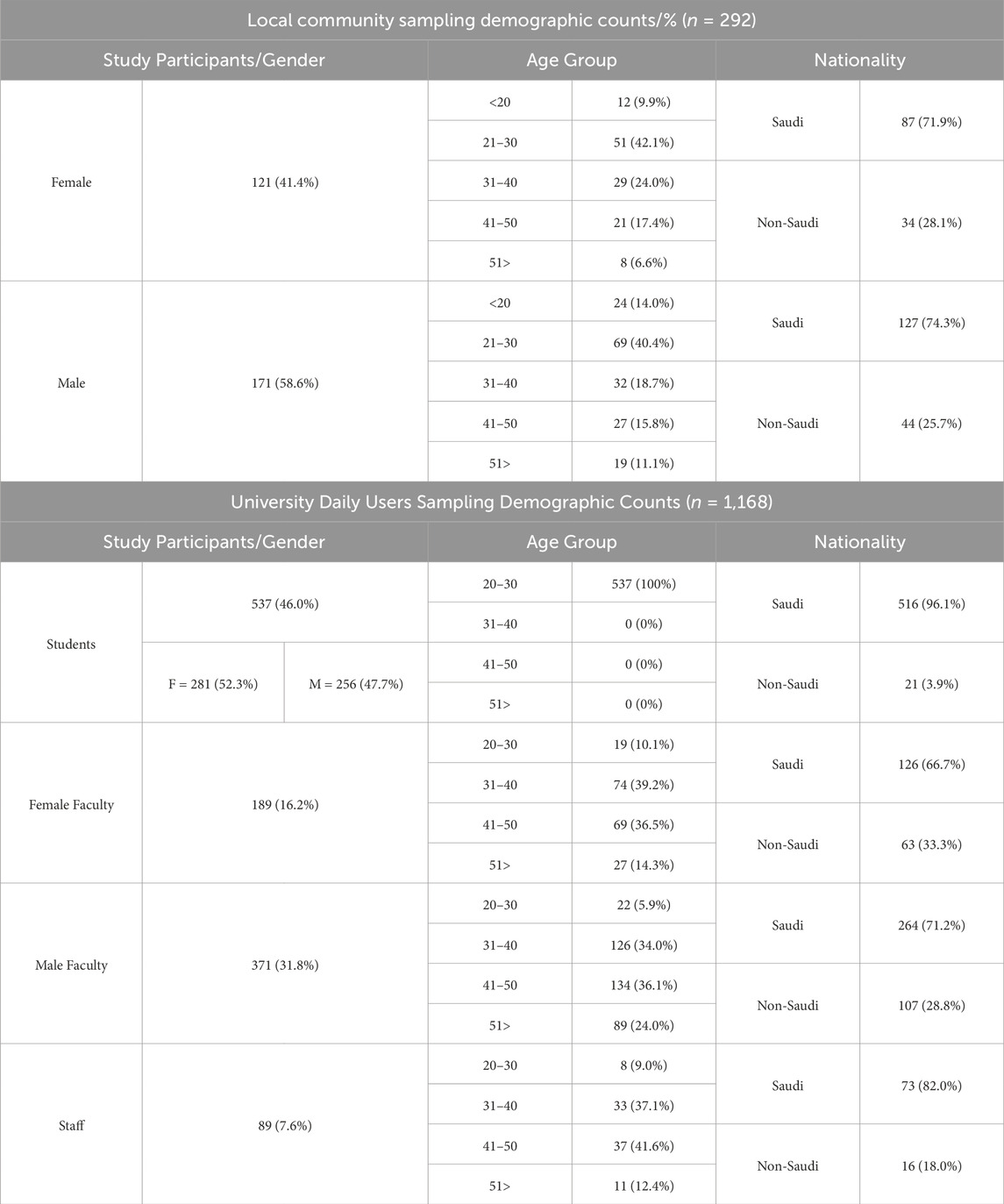

The study employed a ‘stratified convenience’ sampling approach. The ‘local community’ survey included (n = 292) participants who came from different geographic areas of Hail City to represent northern, central, and southern regions of the city and included people who had knowledge of, or lived near, the campus. The ‘university community’ survey (n = 1,168) used a ‘proportional stratification by group’ approach (groups: students, faculty, staff) and collected responses through open calls via university email and in-person invitations at major campus buildings. Each survey was structured around predefined indicators and Likert-scale descriptors were used to measure agreement levels.

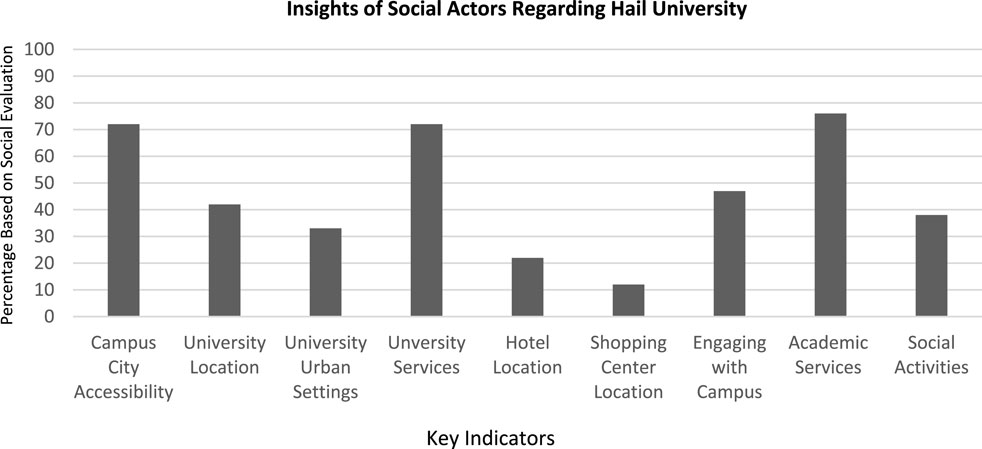

Two thematic analysis-based online surveys were deployed to develop a better understanding of predefined indicators related the Hail University (Table 1). The first survey targeted the local community to identify insights related to their opinion related to nine key indicators: campus-city accessibility, university location, university urban settings, university services, hotel location, shopping center location, and university social activities. The second survey targeted daily actors (faculty, staff, and students) with the goal of developing an understanding of the perceptions of daily users of the campus around eleven indicators: transportation, campus legibility, social activities, facilities, accessibility, safety, comfort, academic services, hotel-campus interaction, and shopping center-campus interaction. Both themes are intended to develop a better understanding of how the local community and campus daily users perceive and use the university campus.

To analyze the relationship between demographic groups and perception patterns, the survey data were subjected to both descriptive and inferential statistical analysis. Cross-tabulations were conducted to examine differences across participant types (students, faculty, local community) concerning satisfaction with key campus facilities and services. A chi-square (χ2) test of independence was applied to test for statistically significant associations between categorical variables, such as facility satisfaction and user type. Additionally, Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were calculated to assess linear relationships between continuous variables such as proximity to campus and reported level of campus engagement. These analyses were performed using SPSS statistical analysis software (v.26), with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05. The results offer insight into whether spatial access and demographic factors influence participants’ perceptions and levels of engagement with university infrastructure.

3.5 Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with members of the local community as well as the community of daily users of the university to gain insight into how Hail University can better engage with the surrounding community, how it can elevate the university community’s on-campus social life, and develop recommendations for investment and improvement opportunities.

Regarding social actors (the local community), a number of questions were asked to gain insight into opinions on various campus issues: (1) perspective regarding Hail university as an educational institution, (2) opinion regarding the campus urban setting, (3) perceptions of the hotel and its location, and (4) perceptions of the shopping center and its location. Also, locals were asked about other indicators such as location, physical accessibility, flexibility, and space utilization.

Regarding campus daily actors (university faculty, staff, and students), questions were more targeted to developing an understanding of the current status of campus social life and economic feasibility: (1) How important is having a vibrant social life on campus? (2) How satisfied are the users with the variety of social activities available on campus? (3) What users think about having the shopping center as the university social hub? (4) Is the shopping center structure possible for reinvestment? Also, daily users were asked about other variables such as: (1) the location of the campus within the city in terms of transportation and accessibility, (2) the campus overall urban settings, (3) integration and connectivity among various buildings, (4) their opinion regarding the hotel and its location, (5) the shopping center and its location, (5) and their willingness to stay on the campus.

4 Results: Hail urban campus and social activities

The perspective of social and daily actors on the Hail University campus is an important area of investigation with significant implications for academic institutions, surrounding neighborhoods, and the region’s prosperity. University campuses are dynamic and multifaceted environments that promote the exchange of knowledge, culture, and innovation. They do, however, intersect with the lived experiences and socio-economic fabric of the local community. This section investigates the various perspectives on Hail University’s urban and social activities held by members of the local community and the campus community. We can understand the complex relationship between universities and their surrounding communities by delving into their perspectives on economic impact, community engagement, social integration, and campus urban settings. The goal is to provide insights that will in turn inform strategies and policies that result in harmonious and mutually beneficial partnerships between Hail University, regional authorities, private and public investors, and the local community.

4.1 Investment opportunity in hail campus

The hotel and the shopping center are situated in a way that makes connecting to the campus from both the outside and inside possible (Figure 3). They are visible from the outside and close to a major road, making them suitable for investment. However, the current fenced structure presents a problem, as the only current entrance to them is from inside the campus. Due to the controlled-access environment, this design may cause private and public investors to hesitate to rent out these structures. On the other hand, the shopping center can be reached within 5 minutes of walking from most university locations, including the engineering college. The shopping center structure is still closed and fenced off from all activity, so accessibility between it and the university community is still a concern. Thus, the lack of proper pedestrian walkways, paths for micromobility users1, as well as safe crossing points along the busy road leading to the shopping center poses a safety risk for students. The university authorities must take the necessary measures to ensure safe and convenient access to the shopping center for the university community.

Figure 3. Hail University campus location within the city and the hotel and shopping center structures. Source: the authors.

Despite the shopping center’s proximity to the university, its closure and fencing off of all activity are major concerns for accessibility between it and the university community. Even though most locations within the university are within walking distance from the shopping center, the center did not benefit from providing the university community with easy access to various amenities such as restaurants, shops, and entertainment venues. The shopping center closure has led to increased alternative socializing options around the university, including local markets, coffee shops, and small businesses. These other nearby options offered more convenience than the campus’s current amenities, which has led the campus community to leave immediately when they have the opportunity. As such, despite the shopping center’s current inaccessibility, many options are still available for university authorities to explore urban renewal to boost community engagement with the campus.

These two examples showcase an opportunity for how Hail University can successfully incorporate business investments into its campuses to promote social engagement. Hail University can create thriving communities that benefit both the institution and the surrounding environment by fostering partnerships with local businesses and developing multi-use spaces. By partnering with local businesses, Hail University can create a network of support that benefits not only the university, but also the community as a whole. This can be achieved by offering students internships and job opportunities, collaborating on research projects, and providing resources for community events. In addition, developing multi-use spaces on campus can encourage social engagement and create a sense of community among students, faculty, and staff. These spaces can be used for various purposes, such as hosting events, meetings, and workshops. Hail University can become a hub for innovation and social change in the region by investing in these initiatives.

By delving into local and daily community perspectives on economic impact, community engagement, social integration, and campus urban settings, we can better understand the complex relationship between universities and their surrounding communities. Hail University can encourage its daily community to participate in campus activities by raising awareness, making it simple to get involved, offering incentives, collaborating with the local community, and providing leadership opportunities. As a result, local and daily community perceptions of Hail University’s campus are gathered and thoroughly discussed in order to gain a better understanding of how they perceive and use the university campus.

As a result, the spatial assessment of the urban configuration of Hail University focuses on campus circulation, land use distribution, and the physical relationship between educational clusters and the commercial/hospitality zone. Despite the urban radial alignment, direct observation reveals significant spatial fragmentation, as indicated by long walking distances and the absence of shaded pedestrian/micromobility corridors linking the academic blocks to the service zone.

The 10-min driving distances to adjacent urban neighborhoods further highlight the campus’s vehicular dependence and the lack of urban porosity. Although the hotel and shopping center are located at a prominent junction within the campus, their accessibility remains constrained due to surrounding fencing, wide setbacks, and underdeveloped interfaces.

These spatial and visual barriers explain the underutilization reported in survey responses and observations, as the service buildings fail to function as active nodes of social or economic exchange. Direct observation underscores the need for spatial activation strategies such as interface redesign, permeability enhancement, and mixed-use programming to reintegrate these critical assets into the campus’s daily life.

4.2 Local community (social actors) perceptions

'Place’ represents cultural and social elements from which people draw references in order to construct their sense of ‘self.’ Administrators should also use location to manipulate personal identity, culture, and create a livable place (Lewicka, 2008). As a result, in order to ensure the success of any project, social actors must participate and play multiple roles in the production of goods, services, and accommodations through interactions with other actors in various contexts (Lamb and Kling, 2003). This participatory approach not only enhances the effectiveness of the project but also promotes a sense of ownership and community engagement. By involving social actors in decision-making processes, Hail University administrators can ensure that the projects meet the needs and desires of the local community.

Although this concept can be complex in the context of educational campuses, most university administrators are likely to focus on the educational aspects. Thus, we contend that these two structures (the hotel and shopping center) should be viewed as public structures and social hub opportunities to ensure their success. Several local communities, for example, stated that they had not heard of, or were unaware of, the hotel’s activities during interviews. More strikingly, they are unaware of the shopping center structure’s existence or that the structure near the hotel is in fact a shopping center. Locals described having no interaction with the university or rarely traveling to the university’s location. This limits their awareness of the urban development on that side of the city. This insight supports Lamb and Kling’s argument that the hotel and shopping center should provide more than merely an accommodation and shopping experience in order to engage visitors. Thus, it is important for the university’s administration to create a sense of community and offer unique experiences that will attract visitors who may not have any direct affiliation with the university, through the use of the hotel and shopping center structures. This can be achieved, for example, through hosting events, providing recreational activities, and investing in community services.

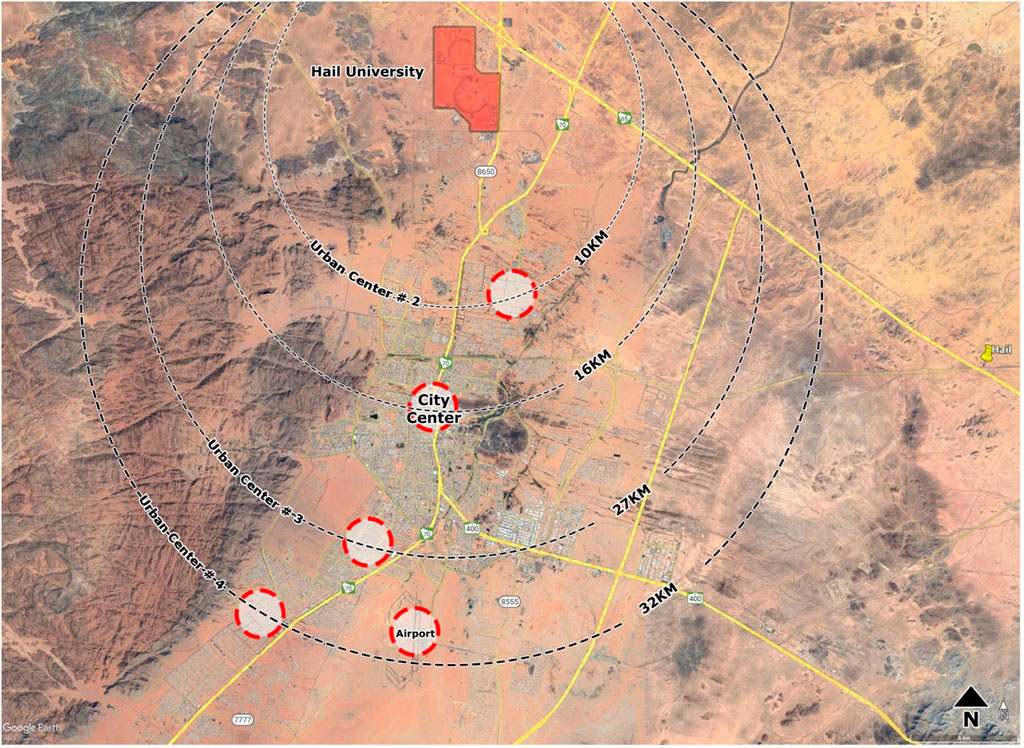

The spatial configuration of Hail University in relation to major urban nodes across the City of Hail presented in (Figure 4) showcases that urban Center #2, for example, which is located closest to the university—is still 10 km away, limiting the potential for spontaneous or routine urban interaction. Conversely, the City Center and Airport, located 16–27 km from campus, underscore the infrastructural and psychological distance that separates the university from the city’s economic and cultural hubs. The map highlights the broader challenge of integrating peripheral educational infrastructure into the city’s urban metabolism. It further supports thematic findings of spatial disconnection, limited footfall, and underutilized campus facilities, reinforcing the need for mobility strategies, land-use interventions, and policy instruments that can reposition Hail University as a regional anchor within a fragmented urban system.

Figure 4. Current Hail urban center in relation to the University’s campus location. Source: the authors.

This insight supports the conclusion of previous studies such as (Dober, 2000; Strange and Banning, 2001) that the quality of the physical environment of university campuses is one of the most influential factors in local community engagement and place development. The findings of these studies suggest that investing in improving campus infrastructure and facilities can positively impact the surrounding community and contribute to the development of a sense of place, positioning the campus to be not only viewed as an educational specific place, but also as an urbanized hub that welcomes and invites different actors.

As a result, a survey was distributed to the Hail community to gather their opinions on the campus’s current state. Accessibility, location, urban settings, services, hotel location, shopping center location, and social activities were the seven indicators surveyed. Additionally, a number of interviews were conducted to supplement the survey in order to gather more information about the results and gain a deeper understanding of how the community views and values Hail University (Figure 5). The results of the survey and interviews provided valuable insights into the perception of Hail University by the community. The survey reveals that the community is generally satisfied with the academic quality and student services offered by Hail University. However, there are concerns about the location of the university, the hotel, and the shopping center, which are seen as less convenient than those of other universities in Saudi Arabia.

The survey’s findings indicate that despite the campus’ accessibility from the city, the local population still does not think the University’s location is practical. This is due to placement of the campus, high in the north of the city, far from the most densely populated urban areas. What’s more, Hail City’s urban growth is more concentrated in the south. This issue exemplifies why locals think the hotel’s location is inappropriate because most hotel guests prefer to be close to urban activities. The hotel’s isolation from the city, according to several interviewees, is the reason for its low occupancy. Furthermore, the hotel’s lack of accessibility to public transportation contributes to its low occupancy rate. Guests who do choose to stay at the hotel often complain about the inconvenience of having to drive long distances to reach popular tourist destinations. Despite these challenges, the hotel management has made efforts to attract guests by offering shuttle services and partnering with local tour companies. However, these initiatives have not been enough to significantly boost occupancy rates.

For the hotel to thrive, the university administration may need to consider redeveloping the shopping center structure or investing in more convenient entertainment options for its guests. Until then, it will continue to struggle with low occupancy rates and a reputation for being too isolated from urban activities. Overall, the survey and interviews provided a comprehensive understanding of how Hail University is perceived by its community and highlighted areas where improvements could be made to better meet their needs and expectations.

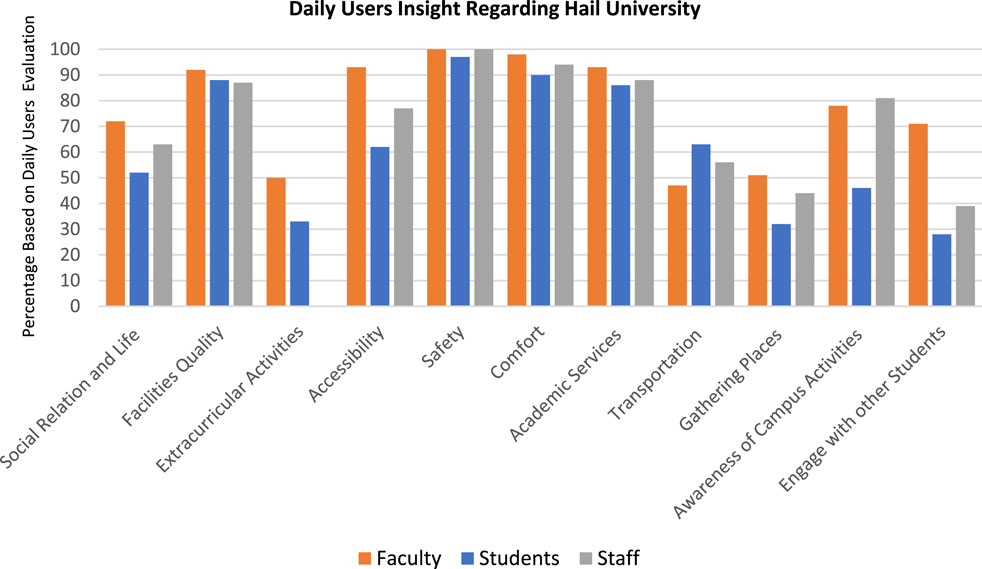

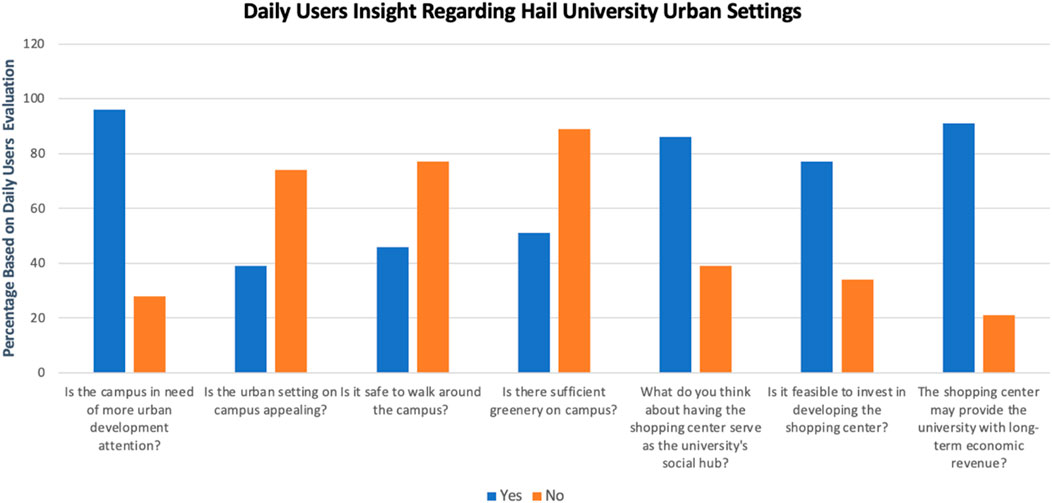

4.3 Faculty, staff, and student (daily actors) perceptions

The faculty, staff, and students of Hail University have a significant influence on shaping the university’s campus social experience. First and foremost, faculty members can set the tone for the classroom environment, which can in turn affect the social dynamics of the campus. By creating a welcoming and inclusive classroom culture, faculty members can help to foster a sense of community among students and encourage respectful and productive dialogue, as they are often involved in advising and mentoring students, providing opportunities for students to develop their academic skills, career goals, and socially engage with university activities. During an interview with a number of university faculty members, the faculty asserted that the colleges and supporting organizations within the campus need to elevate the social activities and experiences on campus (Figure 6). They also asserted that the connectivity among various college buildings is weak and having no social/commercial hub inside the campus lessens the social bond among faculty/staff and students. While asked about the shopping center structure, they asserted that the neglect of quick action to effectively operate the center leads them and the students to find alternatives outside campus to socialize during break times. They believe that there is an economic opportunity for the shopping center that the university administrators need to consider. Given the number of workers and students combined that could make use of the shopping center could generate stable revenue for the shopping center at least 5 days a week. In addition, the center could function as a social/commercial hub that encourages students to stay longer on campus.

In contrast, a number of staff members asserted that an environment that is hostile or unsupportive can have a negative impact on the social experience of students, making it more difficult for them to feel connected to their peers and to the larger campus community. As a result, the staff members asserted that, for example, the majority of students still have difficulty finding their way on the campus, have no knowledge about college activities, and do not know the location of various campus services. The staff members believe this is due to the campus’s current lack of urban areas, its lack of any meaningful social hub, as well as its lack of suitable pedestrian (and micromobility) pathways between the various structures on campus. Staff members mentioned the King Saud University in Riyadh as a local example, where that university has what is called the “main hall.” This hall is an inspiring, vast, open, communal courtyard space that is linked to various colleges, and a wide variety of social and commercial activities are conducted in the main hall. This is an important component of Hail University that simply does not currently exist. A similar facility could be developed by remodeling the shopping center structure and constructing more inviting pedestrian/micromobility connections with various nearby colleges.

During an interview with Hail students, we asked the students what they thought is the most important aspect of social life on a university campus? They identified having a sense of community as a crucial element of university social life. A sense of community creates a feeling of belonging, and will help students feel connected to the university. Also, having a variety of social events and activities is needed to allow them to explore their interests and meet other students. This is a significant finding, as one of the surprising insights of the study is that several students confirmed that they mostly do not know other students from other departments or colleges and rarely engage with students from other colleges. When asked about the reason for not interacting or even meeting students from other colleges, the students agreed that a hub that provides them with social activities beyond the educational aspect of university life is missing from Hail University, which limits their interaction with other students beyond interaction in the classroom.

Brinkhurst et al. (2011) found similar results when they noted that top-down sustainability initiatives in North American campuses are unlikely to succeed without grassroots, student-led social life initiatives. The lack of a social nucleus at Hail University is similar to the situation of other campuses where structural limitations limit community bonding opportunities unless they are intentionally designed through urban form and policy. That is why, for example, the Architectural Engineering Department of Hail University, initiated community service opportunities and fostered student activities to drive student participation, encouraged students to volunteer at campus events or participate in social activities to help students bridge the gap between students and faculty. These actions helped to create a more collegial and welcoming campus culture. This approach has been proven to increase student retention rates and overall student satisfaction with their department/college experience. By fostering a sense of community and belonging, students are more likely to thrive academically and experience higher levels of personal satisfaction.

However, students asserted challenges they face when it comes to social life on campus. For example, students have noticed that sometimes they have a hard time finding events that interest them. It can be difficult to navigate the various clubs and organizations in their department, this was an especially common experience for first-year students. Students asked for more events that are specifically designed to help students connect with each other. More importantly, students identified the issue of missing spaces and places within the campus that facilitate communal activities for students. Thus, the survey results (see Figure 7) reveal that social and communal life, facilities quality, extracurricular activities, accessibility, safety, comfort, academic services and transportation affect student inclusion at university campuses.

To explore potential associations between user type and satisfaction levels, cross-tabulation was performed comparing student, faculty, and local community responses regarding the perceived value of campus facilities. A chi-square test (χ2 = 13.42, p < 0.01) revealed a significant association between user category and satisfaction with the shopping center. Students rated it more negatively (68% unsatisfactory) than faculty (52%) or local respondents (41%). These patterns suggest differentiated expectations and awareness levels based on daily exposure to the campus environment. Similarly, a Pearson correlation (r = 0.46, p < 0.01) was found between respondents’ reported ease of access to the campus and their level of perceived campus engagement, confirming spatial proximity as a predictor of user satisfaction.

These findings align with what (Gümüş et al., 2020) and (Yazgan, 2022) evaluated in Turkey, as they noticed that students at campuses located in peripheral areas with no urban life tend to be less satisfied. This demonstrates that students need both close physical distance and social connections between their university and the city to become actively engaged. The results of this study indicate that Hail University’s low student engagement and dull campus environment stem from its insufficient urban integration. Thus, students themselves are significant actors in shaping the university campus experience. They contribute to the intellectual and cultural vibrancy of the campus through their participation in academic and extracurricular activities. Students are often at the forefront of creating a sense of community on campus, through their involvement in clubs and organizations, their participation in social events, and their engagement with the broader community through service and outreach activities.

As a result, staff members, including administrative, technical, and support staff, are responsible for creating a supportive and welcoming environment for students. They help to ensure that campus facilities are well-maintained, that campus events are well-organized and executed, and that students have access to the resources they need to succeed. Additionally, staff members play a crucial role in fostering a sense of community on campus by organizing social events, supporting student organizations, and providing opportunities for students to engage with one another and with the larger community. Overall, the university campus experience is shaped by the collective efforts of its daily users (faculty, staff, and students) each of whom brings unique perspectives, talents, and contributions to the table. Thus, a successful campus experience requires collaboration and mutual respect among all members of the university community.

5 Discussion

After delving into the study of Hail University as a case, there are a few issues with sustainable investment at the University, particularly investments in the campus, the hotel, and the shopping center locations within the city. The high cost of sustainable investments, such as greenery areas, maintenance, or renewable energy systems, can be expensive to implement and require long-term commitments in an area that is considered rural (Figure 8). Another difficulty is the requirement for stakeholder involvement, as sustainable investments need the support and agreement of many parties, including local businesses, students, staff, local governments, and local communities. Therefore, it is necessary to invest in effective stakeholder engagement strategies that encourage involvement, transparency, and accountability.

Developing sustainable university campuses is not without its challenges, but there are also adequate opportunities. The potential for Hail University to become the anchor zone between the south and north areas of the region is one of the most significant opportunities. Hail University can advance the sustainability agenda and encourage social urban growth and practices through its research, teaching, and outreach initiatives. Another opportunity is for Hail University to work with businesses, local governments, and civil society groups to improve the quality of the area around the campus and create sustainable urban environments. The university can collaborate with local organizations to advance sustainable development in the region, including private investment and the promotion of urban activities close to the campus.

Thus, a variety of approaches can be used to develop sustainable university campuses. Urban sustainability education should be included in the curriculum, for example. Hail University can include urban sustainability concepts in courses in a variety of subject areas, including business, engineering, and the social sciences. Students may adopt sustainable behaviors and practices as a result of becoming more knowledgeable of sustainability approaches and best practices.

Adopting sustainable urbanization practices is another tactic. Hail University has the capacity to create buildings that are water- and energy-efficient, for instance, as well as an urbanized campus that is sustainable. This, in our opinion, is feasible given the close proximity of the University’s various college structures and the vast, empty spaces within those structures that are still undeveloped and available for such a concept. Through a design that supports indoor environmental quality, such as offering accessibility between various structures, mobility, social engagements, natural lighting, and ventilation, the campus may be rethought as a sustainable work-education living experience.

These approaches must be considered because the university community is dissatisfied with the current situation, based on the data gathered about campus social activities and urban settings (Figure 9). The majority of survey responses indicate that the shopping center structure might be the best place to replace this missing social hub, so members of the community do see room for improvement. Also, the campus is located in a rural area with nearly no urban activities nearby, which requires campus users to travel long distances between sessions. For instance, students concurred that the campus does not support student exchange and that it is difficult for them to get together for social gatherings, study sessions, or relaxation breaks between classes, which drives them to leave campus immediately when there are no classes. These findings suggest that Hail University should make sustainable investments to improve social interactions among its daily users because, at the moment, even the local residents do not interact with the campus. These facts help us understand why the shopping center is vacant, and why the hotel suffers from a low occupancy rate. Currently, these two structures are isolated, neglected, and do not benefit from the campus activities and the enormous number of potential customers on campus.

The coded thematic insights in (Table 2) show how different actor groups (students, faculty, and community members) have unique perspectives that simultaneously (and paradoxically) converge and diverge. The comparative matrix shows that all three groups share frustrations about spatial disconnection and underused infrastructure but also reveal specific expectations about cultural identity and mixed-use revitalization. These patterns are essential for developing context-sensitive design and planning strategies.

The explanations that consistently came up when the Hail University Planning and Projects Department was asked to explain why the shopping center is vacant, is its remote location the sparsely populated urban settings of the campus and the surrounding areas, as well as other key issues regarding the shopping center’s design. As a result, upgrading the shopping center’s structure, using it to more directly serve the university community, and connecting the shopping center to the nearby hotel is probably the best course of action, given the situation. Additionally, even though the campus is to the north and far from Hail City’s dense population, an opportunity arises to support the growth of the surrounding neighborhoods. The shopping center may be positioned as a shoping destination for people who live north of the university, a shorter travel distance compared to shopping in Hail’s city center. This is a reasonable proposition because the campus is well-connected to major roads and is in close proximity to these north and northeast towns, which will be the best shopping option for those residents when developed (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Hail campus as a potential investment anchor for nearby northern towns. Source: the authors.

The challenges identified in this study are consistent with the findings of Abubakar et al. (2016) in their study of the University of Dammam, where they found that stakeholder engagement and sustainable development are limited by administrative fragmentation and low external participation. Like Hail University, the lack of integration with local authorities delayed sustainability efforts, which highlights the need for collaborative planning in campus urban development.

Having said that, plans are in place to renovate and open up the shopping center to the public in the future. The proposed renovations include adding more entrances and exits, as well as urbanely connecting the center with nearby colleges. This would not only make it easier for the university community to access the shopping center, but it would also increase the accessibility of the shopping center for commuters and residents in the surrounding area. Additionally, there are opportunities for incorporating more green spaces and outdoor seating areas into the design, creating a more inviting atmosphere for outside visitors and daily users. These future renovations, if made, would not only improve accessibility between the daily community and the shopping center, but also greatly enhance the overall experience for anyone who visits, as well as provide an economic boost to the surrounding area.

As a result, Hail University should make use of this opportunity to encourage public-private partnerships. It may be possible to collaborate with regional authorities like the Hail Municipality and Hail Region Development Authority, nonprofit organizations like the Saudi Life Quality Program, and private sector organizations to create sustainable infrastructure, increase the level of services provided, improve the area’s quality of life, and offer amenities that support flexible and lasting work/educational engagement that will eventually provide a boost to the north aeras of Hail region, enabling them to thrive.

Overall, the develoment of socially-engaging and sustainable campuses are critical goals for universities in the twenty-first century. Hail University can achieve its goals by incorporating sustainability into the curriculum, implementing sustainable building practices, promoting sustainable transportation options, and providing more inclusive, social urban settings. Taking these factors into consideration, Hail University can develop a campus that is both environmentally friendly and beneficial to all regional parties involved.

In line with the outcomes of the Wesbrook Place model at UBC (Girling, 2015), embedding commercial hubs into peripheral university campuses is an effective way to enhance walkability and increase student retention on campus. The Hail shopping center, if redeveloped following this precedent, could serve as a social-commercial nucleus that strengthens both the university’s internal vibrancy as well as its external engagement.

While this study highlights how Hail University can serve as a development driver for urban areas, it also reveals the potential dangers of peripheral campus designs. Public investment in these types of campuses in other countries has typically worsened spatial inequality because the investment focuses on distant locations that remain inaccessible to most people while ignoring central urban areas. Studies shed light on how the decentralization of knowledge-based institutions may unintentionally lead to urban service fragmentation and restricted mobility opportunities for lower-income populations (Addie, 2020). The current isolation of the Hail campus from Hail’s urban center threatens to maintain social exclusion patterns that currently exist because educational and cultural assets will remain mostly available only to mobile, higher-income users.

Moreover, while this paper envisions a campus-led regeneration scenario, alternative outcomes must be critically examined. Without deliberate governance reforms and spatial integration strategies, investments in the Hail campus could lead to land speculation, gentrification near future transit corridors, and the privatization of public goods. As (Pinto, 2023) suggests, planning optimism must be tempered with an understanding of power dynamics, implementation gaps, and the unintended consequences of design interventions. Therefore, policy options such as phased development, transit-oriented design, community land trusts, and formal community advisory boards should be explored to ensure that the benefits of the university’s growth following investment are distributed equitably. These pathways align with principles of inclusive urbanism and long-term territorial sustainability.

Aesthetics aside, effective campus design shapes the interactions and experiences of its daily users (students, faculty, and staff). To create a vibrant social environment that promotes collaboration, interaction, engagement, and connectivity between campus buildings, minimum urban quality of life principles are required in order to ensure a functional campus layout, principles such as:

• Pedestrian and Micromobility Pathways: Connectivity and accessibility can be improved through the development of well-defined pedestrian and micromobility pathways connecting various campus buildings. The robust network of paths should be wide enough to accommodate large groups of people, with interesting contours. To improve the quality of the experience (avoiding motor vehicle noise and exhaust fumes), the pathways should be as separate from roadways as possible. For ease of use, the pathways should make use of smooth surfaces (or crushed gravel fines) and gradual inclines (although, not completely flat). Pathways should be strategically designed to encourage people to stroll, gather, and interact with one another and the surrounding environment, fostering spontaneous social interactions. For safety and to encourage diverse use, the pathways should include a separated micromobility (bicycle, ebike, and electric scooter) path adjacent to the pedestrian path (Sandt, 2019). Enabling micromobility devices on the pathways will effectively shorten the distances between colleges/buildings and between the shopping center and colleges as travel times between points will be reduced by 67%–75%2.

• Micromobility Parking and Charging: To encourage the use of micromobility devices, adequate space should be provided at each of the colleges/buildings and the shopping center for micromobility users to secure their bikes, ebikes, and scooters. The ability to charge devices should also be provided.

• Green Spaces: The redesign should incorporate lush green spaces throughout the campus, providing areas for relaxation, study, and socialization. Lawns, gardens, and small wooded areas are examples of these types of spaces. A mix of native and ornamental plants improves the visual appeal while also promoting sustainability and biodiversity.

• Open Areas: Quality of life can be improved by designating open spaces for larger gatherings, events, and play (informal sports) such as amphitheaters, plazas, and central squares, to facilitate organized activities such as performances, exhibitions, festivals, and informal sports matches (football, frisbee, etc.). These spaces should be easily accessible from various buildings, encouraging cross-disciplinary social (and professional) interaction.

• Outdoor Furniture: Personal interaction may be encouraged by strategically placing outdoor furniture along pathways and within green spaces, such as benches, seating clusters, and picnic tables. The furniture should be both comfortable and long-lasting, and it should be able to accommodate both individuals and groups. This encourages the daily community to spend time outside studying, socializing, and meeting informally.

• Shading Solutions, Night Lighting, and Drinking Fountains: Given the importance of providing sun protection in such a setting, encouraging outdoor activities must include shading solutions, such as pergolas, shade sails, and tree canopies. These structures not only improve comfort but also create inviting outdoor spaces, even in hot weather. Shade elements placed correctly can define and encourage the use of spaces. Adequate lighting at night will encourage evening use of the pathways. Strategic placement of drinking fountains can provide needed refreshment to the community.

• Wayfinding and Signage: Clear wayfinding signage is required to guide individuals to various destinations throughout the campus. Effective signage facilitates navigation while also encouraging people to explore, discover, and participate in various social activities. Large maps at key access points can help new students and visitors navigate the campus, shopping center, hotel, etc.

• Sustainability Initiatives: It is critical for long-term success to ensure that the design aligns with sustainable practices. This includes the use of locally-sourced materials where possible, energy-efficient lighting, and water-saving landscaping techniques. This dedication to sustainability benefits the campus environment and is consistent with the values of today’s university vision.

By promoting these urban techniques, it is possible to transform the Hail University campus into a thriving social hub where students, faculty, staff, and the local community engage, connect, and collaborate with one another. Thoughtful urban design that focuses on connectivity, greenery, comfort, and adaptability can foster a setting that not only enriches the educational experience but also promotes a sense of community and belonging.

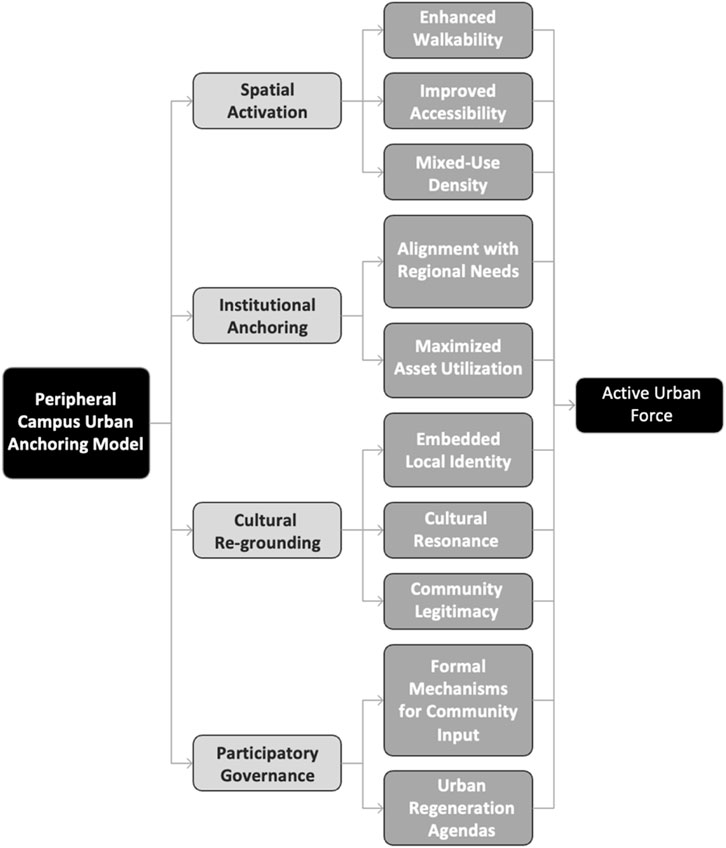

Finally, the study introduces Peripheral Campus Urban Anchoring as a conceptual framework to enhance the theoretical understanding of campus urbanism and regional development. The model demonstrates how peripheral university campuses can function as integrated urban anchors through specific spatial, institutional, and social interventions based on Hail University’s empirical data (Figure 11). The model rests on four interconnected pillars.

1. Spatial Activation: Enhancing walkability and micromobility, accessibility, and mixed-use density to counteract peripheral isolation.

2. Institutional Anchoring: Aligning campus facilities with regional needs (e.g., conferences, hospitality, retail) to maximize asset utilization.

3. Cultural Re-grounding: Embedding local identity (e.g., Najdi heritage) in campus design to foster cultural resonance and community legitimacy.

4. Participatory Governance: Establishing formal mechanisms for community input in university planning and urban regeneration agendas.

The model expands existing research on non-metropolitan campus-led development (Addie, 2020; Biswas, 2025) while extending critical urban theories by understanding peripheral campuses as both marginal spaces and potential high impact catalysts for both community building and economic development. The model transforms university space from an educational container into an active urban force that connects central and peripheral areas.

6 Recommendations and implications

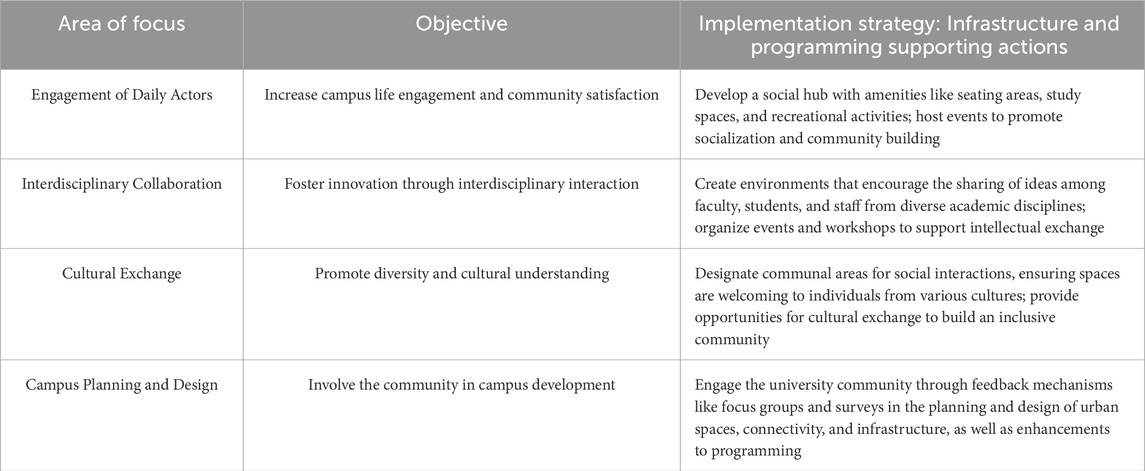

A key component of the overall student experience (and student perceptions of university quality) is the social side of university life. Social interactions aid in the growth of interpersonal abilities, and the fostering of friendships. However, Hail University must develop plans and make prudent investments in its infrastructure in order to foster a vibrant social life on campus. The creation of a social hub that is specially tailored for campus daily actors is one strategy the study suggests for promoting social interactions and improving campus life. The creation of a social hub has the potential to benefit both the university community and the (northern) residents of Hail. Therefore, this study suggests four areas of focus to enhance Hail University’s campus infrastructure and programming (Table 3).

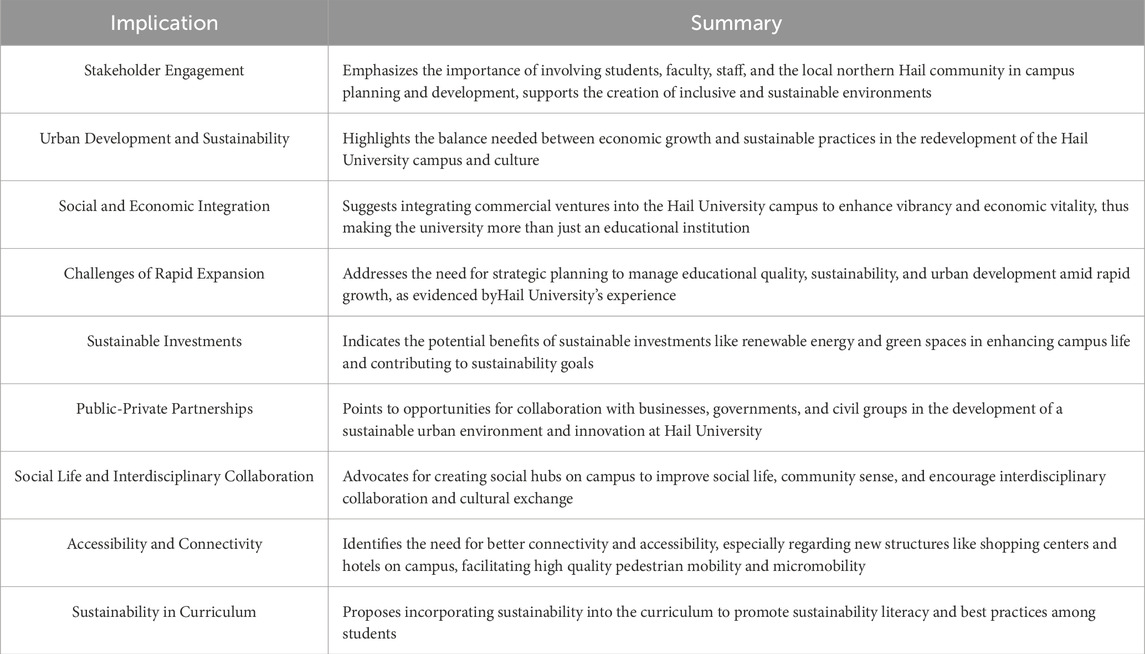

Table 3. Summary of recommendations to enhance Hail University’s campus infrastructure and programming.

The implications outlined in (Table 4) propose a strategy to improve the quality of university campus life, with a specific emphasis on four key domains. The primary objective is to enhance participation among individuals who engage in daily activities by creating a central location that provides a wide range of facilities and chances for social interaction. This will ultimately cultivate a feeling of inclusion and overall satisfaction within the community. Furthermore, it fosters interdisciplinary collaboration by establishing physical environments that facilitate the exchange of ideas among diverse academic disciplines, thereby cultivating a dynamic intellectual community. Furthermore, the design of communal areas within the campus environment significantly emphasizes fostering cultural exchange. This is achieved by creating spaces conducive to social interaction, thereby promoting diversity and inclusion among campus community members. Finally, it promotes the active engagement of the campus community in the strategic development and architectural layout of the university’s urban areas, guaranteeing that these spaces align with the community’s requirements and desires, thereby improving connectivity and infrastructure. The implications collectively aim to foster a dynamic, flourishing, and all-encompassing campus milieu that facilitates social interaction, advancement, and continuous education.

This study emphasizes the importance of reimagining Saudi university campuses, and Hail University in particular, as not only educational institutions, but also hubs of social, cultural, and economic engagement. Developing and implementing strategies that promote collaboration, shared resources, and mutual benefits is critical to achieving a more harmonious relationship between faculty, staff, and students of Hail University as well as with the surrounding northern Hail community. Also, the study provides a comprehensive view of the challenges and opportunities in developing a sustainable university campus, emphasizing the importance of stakeholder engagement, sustainable urban development, social and economic integration, and the creation of vibrant community spaces.

Furthermore, addressing the campus community’s concerns about currently inadequate infrastructure and social spaces is critical for the holistic development of future generations and the long-term success of the university. Thus, establishing a social hub and refining the urban settings of the university campus can greatly improve the social lives of the members of the university and the inhabitants of northern Hail by encouraging a sense of community, interdisciplinary cooperation, and cross-cultural exchange. The study took the example of Hail University’s shopping center redevelopment as an example of how the university can accommodate the various needs of its daily users and contribute to an active and welcoming campus community by carefully considering the shopping center as social hub’s design, location, and programming. However, strategies such as adopting a comprehensive urban renewal plan for an area with a high potential to be a suburban zone by connecting the various northern towns and villages with Hail City are the goal, with Hail University serving as the anchor zone, growing in importance over time in the region.

7 Conclusion

Urban development in university campuses is an area of growing importance, given the increasing role of universities as economic and social anchors in urban areas. This study reveals a significant disconnect between the Hail University campus and its local communities, as well as dissatisfaction among its daily community members about the university’s inadequate infrastructure and the need for more vibrant social spaces. The study also highlights the need for Hail University to reevaluate its priorities and foster a more inclusive environment for both the daily community and the larger community by gathering and evaluating community perceptions.

Thus, both locals and the daily community are encouraging the university to provide more connectivity across the urban settings of Hail University’s campus. This desire stems from various factors, including a lack of community integration, inadequate infrastructure, and a lack of vibrant social spaces. The local community prefers a more inclusive approach that goes beyond educational impact, focusing on meaningful engagement and collaboration with the university. Similarly, the daily community wants a campus environment that promotes a sense of belonging, provides convenient amenities, and encourages interaction with the surrounding community. To address these concerns, Hail University must engage stakeholders proactively, conduct needs assessments, and prioritize the development of vibrant, inclusive, and sustainable campus environments. Hail University can create spaces that not only cater to the academic needs of students, but also positively contribute to the broader community, fostering a mutually beneficial relationship for all stakeholders by embracing a collaborative and holistic approach.