- Department of Architecture, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria

The success of any architectural space depends on how users perceive and experience it, particularly in arts and cultural centres, which serve as hubs for cultural expression, engagement, and tourism. These centres must reflect local architectural identity to ensure long-term cultural relevance and contribute meaningfully to sustainability goals. This study examines users’ perceptions of the benefits of neo-vernacular architecture in selected arts and cultural centres in Lagos, addressing a gap in comparative evaluations through a quantitative analysis of perceived contributions to cultural, environmental, economic, and social sustainability. Out of 120 distributed questionnaires, 110 valid responses were collected across three centres: John Randle Centre, Terra Kulture, and KAP Hub. Data analysis using the Kruskal–Wallis H test and descriptive statistics revealed that while users generally perceive neo-vernacular architecture as beneficial across cultural, economic, environmental and social dimensions, variation exists in how these benefits are expressed across contexts. The findings highlight the need to align traditional architectural expression with sustainability, with future research incorporating objective performance metrics to complement perception-based insights.

1 Introduction

Architecture is crucial in conveying a place’s cultural identity, history, and tradition. Over the last few years, awareness of the requirements for architectural design to reflect and maintain local cultural heritage has grown. Consequently, neo-vernacular architecture has emerged as a modern approach to design that combines traditional architectural principles and contemporary techniques and materials of function and construction (Rajpu and Tiwari, 2020). Rather than copying old buildings, neo-vernacular architecture reinterprets vernacular expressions as conceptual or symbolic ones with fresh form and generates buildings that reveal and reconcile heritage and modernity. Neo-vernacular architecture is not merely about aesthetics but is a philosophy of design to foster cultural continuities, sustainability of the environment, and relevance of the building to society. Nonetheless, in recent studies, it has become evident that designing neo-vernacular architecture is challenging because designers are pushed to strike a delicate balance between traditionalism and originality and to accommodate old-fashioned form to today’s uses and avoid mere superficial copying (Makhloufi et al., 2024). Such challenges are significant for public and cultural buildings, like performing and cultural centres of the arts, because architecture directly influences people’s connection to civic identity and shared memory much more than in other building types.

Lagos stands out for its deep history and vibrant artistic scene. Among its many attractions, arts and cultural centres hold a unique place. They do more than host events; they preserve and celebrate the city’s creative energy and cultural roots. These centres connect tradition with modern life, offering both locals and visitors a space to engage with the customs, stories, and identity of the region (Nemati Nasab et al., 2024). However, as the city continues to grow and modernise, its architecture is changing rapidly, with a growing awareness of the need to protect cultural identity while pursuing sustainable development. This makes the design of cultural spaces more important than ever. Neo-vernacular architecture presents a way to honour local heritage while meeting present-day needs and global environmental goals. When done thoughtfully, it can support sustainable tourism by reducing environmental harm, strengthening the local economy, and promoting cultural awareness and preservation (UNEP and UN Tourism, 2005).

How people perceive spaces of architecture, whether it is stakeholders, locals, or visitors, is crucial to neo-vernacular design success. Such perception extends beyond aesthetic superficialities; it is how people perceive spaces functionally, emotionally, and culturally (Adedayo et al., 2013). Appreciating these perceptions assists designers in producing spaces that are meaningful to different people and remain so over time. How people interpret and interact with such architecture indicates how well neo-vernacular building contributes to cultural identification and sustainable tourism aims. Research from cultural and educational environments shows that people’s perception of spaces directly influences how spaces are utilised and enjoyed, particularly with comfort, symbolic significance, and how the architectural flows (Ediae et al., 2022; Narein and Nirma, 2017; Somaratna et al., 2010). Such evidence demonstrates that perception is not personal but a crucial factor in whether or not design strategies are effective in practice.

Lagos serves as a model for assessing neo-vernacular design benefits, given its deep roots in the Yorùbá culture. Characterised by their courtyards, intricately carved wooden elements, and layouts that foster communal interaction, traditional Yorùbá structures embody a rich cultural narrative (Adeokun et al., 2013). Modern reinterpretation of these architectural features unveils innovative design possibilities that respect and preserve this legacy. Such a synthesis of historical and contemporary design enriches the user experience in the arts and cultural centres. It reinforces cultural pride, ensuring the continuity of heritage within a modern context.

Neo-vernacular architecture has gained attention in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. In the European context, Bartha (2020) highlights how contemporary designs often use symbolic aesthetics to reflect heritage and cultural memory. Over in Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia, researchers have explored how traditional architectural forms are being blended with sustainable building practices, especially in public and religious spaces, where environmental sensitivity and cultural relevance are key concerns (Chairuniza et al., 2020; Lindarto and Joel, 2019).

Similar research from Pakistan and North Africa highlights the role of vernacular references in reinforcing cultural symbolism and local identity in public spaces (Jamil et al., 2024; Makhloufi et al., 2024). Studies like Tiwari and Vij (2024) also examine the adaptation of symbolic forms in Indian temple architecture. However, most of this research prioritises formal qualities, material strategies or aesthetic narratives, with limited attention to how users perceive and engage with these spaces. Comparative studies evaluating user perceptions of neo-vernacular architecture across multiple cultural centres remain scarce. This gap makes it difficult to understand how visitors perceive and interpret such architecture’s social, cultural, economic and environmental benefits, particularly within African urban contexts. Hence, this study explores how users perceive neo-vernacular architecture’s benefits in arts and cultural centres in Lagos by addressing two key objectives. First, it identifies the benefits of neo-vernacular architecture and then evaluates the users’ perception of these benefits in selected art and Cultural Centres.

2 Literature review

2.1 Neo-vernacular architecture

Neo-vernacular architecture, as cultural sustainability, blends traditional and modern designs to create buildings that convey a unique identity without replicating the past. It involves reimagining historical references to meet modern needs and evoke desired experiences through trained architects’ deliberate and informed efforts, ensuring modern design’s adaptability, functionality and cultural resonance (Tiwari and Vij, 2024). According to Rajpu and Tiwari (2020), Neo-vernacular architecture combines the past and the present to reap a sustainable future, as the past signifies traditional and vernacular practices which could not be adopted due to evolving lifestyles. At the same time, the present signifies modern and contemporary approaches that conceal and diminish our vernacular principles by deviating from local traditions and culture and causing environmental degradation. According to Manao et al. (2022), Neo-vernacular combines traditional architectural elements with modern designs to create buildings that resonate with local culture and environmental contexts. It draws inspiration from vernacular architecture, reinterpreting traditional forms, materials, and layouts into contemporary expressions.

According to Wibawa et al. (2021) Neo-vernacular architecture is guided by five principles: Direct, Abstract, Landscape, Contemporary and Future relationships. These harmonise traditional practice of architecture and modern practice and innovations to produce usable, culturally relevant, sustainable and adaptable to future needs.

These design concepts are part of a broader global movement in which neo-vernacular architecture is a vehicle to resist globalisation’s tendency for sameness. Memmott and Davidson (2008) reveal that architecture is far more than building practice; it is influenced by societal and cultural transformation. Ahmed (2022) builds on this through the lens of Critical Regionalism, particularly in dry, hot regions where locality is crucial. By emphasising responsiveness to place, symbolic significance, and environmental responsiveness, neo-vernacular design has gone from a local issue to a worldwide design ethic.

Neo-vernacular architecture also adheres to international sustainability standards, primarily through local materials employed, passive cooling strategies, and form for energy reduction. Research by Adebamowo and Adejumo (2012) and Adenaike et al. (2020) shows how Yoruba-influenced building practice integrates shading, ventilation, and built order. This architectural strategy also extends into social and economic domains. Ridwan and Eze (2023) highlight how the contemporary reinterpretation of traditional Yoruba buildings serves as a cultural landmark to inspire civic pride and communal unity. Neo-vernacular construction is not done to sustain old buildings in their original setting. However, it is employed symbolically to draw on aspects of the past, such as form, materiality, or composition of space, to develop new buildings attuned to cultural memory for contemporary needs. This reinforces the perception of neo-vernacular construction as a multi-layered practice involving spatial symbolism, climate resilience, and communal engagement corresponding to paradigms present in global research on sustainable tourism, such as those by UNEP and UN Tourism (2005) and Agyeiwaah et al. (2017).

Though neo-vernacular architecture is regularly connected to sustainability and cultural preservation thoughts, it reflects more profound political and ideological transformations. For instance, returning to traditional styles has sometimes served to assert national identity and recover indigenous building language in postcolonial contexts. Wijetunge (2022) discusses how Sri Lankan houses embraced the “American Style” but reinterpreted it through a local filter to better express nationalist principles. In Portugal, Agarez (2014) discovered that neo-vernacular architecture in Algarve was a declaration of regional pride and a subtle rebuke of the strict rules of modernist design. Nonetheless, not all interpret this return as entirely beneficial. Critics such as Venturi and Scott Brown, through Costanzo’s (2012) lens, caution that if tradition is applied simply to decoration, what they term the “decorated shed,” the resulting composition may appear meaningful but possess no cultural or ecological depth. In these instances, traditional forms are applied for display purposes without genuine function or rational explanation. This critique is relevant to how people’s experience of buildings is understood because it reminds us that meaningful architecture must connect with how people live, not just how things appear.

2.2 Theoretical framework

This study uses Cross-Cultural Theory, Place Attachment Theory, and Critical Regionalism to explore how people perceive and experience neo-vernacular architecture in culturally grounded settings. Cross-Cultural Theory explains how architectural traditions shift and evolve through cultural exchange, reinterpretation, and adaptation. Memmott and Davidson (2008) describe architecture as a technical exercise and a cultural idiom defined by history and today’s world. From this perspective, neo-vernacular architecture is not about copying history but mixing old concepts and contemporary realities to mirror place identity. Meaning comes to it through material form and how individuals inhabit these places, navigate them, and form emotional associations over time. For this reason, user perception is crucial to knowing whether or not architecture resonates with culture or flops in practice.

Place Attachment Theory, as articulated by scholars such as Motalebi et al. (2023) and Ujang and Zakariya (2015) considers people’s emotional and symbolic relations with the spaces they inhabit. Such attachments tend to develop based on familiarity, shared memories, and further meaning people assign to a specific environment. In neo-vernacular architecture, traditional building materials or cultural symbols may help to enhance a feeling of identification and render the experience of space more significant. However, when such components tend to feel unrelated to how people live or practice their culture today, the building tends to feel remote or irrelevant. Understanding how users relate to and make sense of the surrounding architecture is important.

Critical Regionalism, influenced by writers such as Kenneth Frampton, Alexander Tzonis, and Liane Lefaivre, champions architecture grounded in local culture and sensitive to climate but resisting globalisation’s homogenising effects (Ahmed, 2022). Although it has much in common with neo-vernacular architecture and values climate sensitivity, cultural responsiveness, and historical reference, Frampton also cautions against “sentimental regionalism,” reusing cultural symbols without regard to their richer social or ecological connotations. User perception is again key: exposing whether a building truly engages with context or superficially imitates tradition. User perception sits at the heart of these theories, not by reference but as physical proof of whether a building effectively reflects cultural identity and delivers a meaningful experience.

2.3 Neo-vernacular architecture as a modern interpretation of Yorùbá culture

Neo-vernacular architecture redefines traditional concepts and reshapes them for contemporary contexts to sustain cultural memory and accommodate today’s requirements. An example is the Yorùbá courtyard, previously a prominent feature of traditional residences. It is often reimagined today as an atrium or common area in urban layouts, yet retaining its cultural and ecological function and occurring in tighter urban contexts (Adedokun, 2014). Art and symbolic ornament also significantly contribute to delivering an expression of identity. Such motifs related to Yorùbá civilisation, like the ideal of Orí (destiny), are being incorporated in fresh designs to link past and present (Akande, 2020; Opoko et al., 2016). Jolaoso et al. (2019) underscore that reimagining these vanishing components is crucial for retaining Yorùbá legacy in present-day architecture.

Sustainability and environmental issues are also important in neo-vernacular architecture, primarily when traditional materials such as bamboo or compressed soil blocks are combined with contemporary building technology. Such decisions facilitate designs that are both culturally and environmentally relevant (Olaniyi et al., 2020). By reinterpreting disappearing components of Yorùbá architecture, for example, symbolic or construction elements, designers can sustain cultural significance in ways both relevant and meaningful today (Jolaoso et al., 2019). Traditional climate passive features such as cross-ventilation, insulating walls, and using plants and green areas are also reformulated to achieve today’s energy and environmental requirements (Adebamowo and Adejumo, 2012; Adenaike et al., 2020; Olojede, 2012).

They reflect global principles of passive sustainability and place-centred design evident in climate adaptation and tourism policies (UNEP and UN Tourism, 2005; Agyeiwaah et al., 2017). They demonstrate how neo-vernacular architecture is culturally relevant and adheres to today’s global climate resilience and sustainable building standards, as such designs help turn public spaces into cultural landmarks, creating environments that locals can feel proud of and visitors find engaging (Ridwan and Eze, 2023). This balance between cultural expression and public appeal ties into wider global conversations around heritage-driven development, where architecture supports economic growth and cultural exchange, scholars like Obradović et al. (2021) and Budeanu et al. (2016) connect this to broader ideas of social sustainability and inclusive cities.

2.4 Benefits of neo-vernacular architecture

2.4.1 Sustainable tourism

Sustainable tourism ensures tourism supports both people and the planet now and, in the future, bringing together environmental care, economic opportunity, and social wellbeing so that everyone involved, tourists, locals, businesses, and ecosystems, benefits in a lasting way. The United Nations (1987) defines sustainability as meeting present needs without putting future generations at risk, and this idea also carries over into tourism. As UNEP and UN Tourism (2005) point out that sustainable tourism means managing tourism’s impact on communities, the environment, and the economy while providing rich and meaningful experiences for visitors. In this way, it is not just about conservation but also balance, fairness, and long-term value for everyone involved.

Sustainable tourism’s environmental aspect aims to sustain natural resources and minimise damage to ecosystems while promoting activities for sustainable conservation in the long term. Agyeiwaah et al. (2017) emphasise the sustainability of resources by conserving water, minimising wastage, and enhancing energy efficiency. Likewise, Blancas and Lozano-Oyola (2022) point to biodiversity conservation and curbing pollution as primary objectives. This aspect also prioritises services like clean water and clean air and seeks to sustain them so that tourism may benefit without depleting what nature offers. Addressing climate change is also an integral part of it. Budeanu et al. (2016) risk analysis and plans are advised to sustain and recover tourism’s exposure to environmental challenges. In practice, Lee et al. (2021) demonstrate how Taiwan’s eco-resorts do so by utilising resources efficiently and establishing robust tracking mechanisms for protecting the environment. Furthering this discourse, Sholanke and Oyeyipo (2023) explore how Nigerian art museums use design like daylighting, energy-saving LED fixtures, and smart lighting controls to lower energy use and improve indoor conditions. These examples show how smart design choices in cultural buildings can actively support sustainability goals.

The social dimension emphasises community involvement, cultural preservation, and social wellbeing. Community engagement ensures that locals actively participate in tourism planning, fostering social equity and ownership (Budeanu et al., 2016; Agyeiwaah et al., 2017). Cultural preservation safeguards tangible and intangible heritage, maintaining traditional knowledge and authenticity, as demonstrated by Bhutan’s tourism policies (Reinfeld, 2003). Practical applications, such as participatory planning and capacity-building programs, strengthen community engagement and improve quality of life by creating jobs, supporting local businesses, and enhancing infrastructure (Obradović et al., 2021). Education and awareness promote responsible behaviour among tourists and empower locals to advocate for their rights, ensuring tourism contributes positively to community development and cultural preservation.

The economic dimension ensures that tourism activities support local economies while maintaining long-term financial viability. Sustainable tourism prioritises local economic development by supporting small businesses and creating diverse employment opportunities, enhancing economic resilience (Agyeiwaah et al., 2017; Blancas and Lozano-Oyola, 2022). Investment in infrastructure, such as transportation and waste management, benefits residents and tourists. At the same time, economic diversification reduces reliance on traditional sectors by introducing eco-tourism and cultural experiences, as well as theoretical perspectives, such as those by Fu et al. (2024), emphasise financial sustainability and equitable income distribution, while practical frameworks by Kurniati and Nurini (2024) highlight the importance of supporting entrepreneurship and monitoring economic impacts. As seen in Italian regions, a study by Antolini et al. (2024) stated that an integrated approach combines multi-dimensional assessments and policy integration to address resource allocation and long-term planning challenges. By balancing these elements, the economic dimension promotes resilience, equity, and inclusivity, ensuring tourism catalyses sustainable economic and social transformation.

2.4.2 Cultural preservation

Cultural heritage preservation ensures that cultural knowledge and traditions are transmitted from one generation to the next. It can be achieved through proper documentation and archiving, facilitating cultural education via museums, libraries, and digital repositories. Community involvement and community-based programs also empower local communities to manage cultural assets (Mekonnen et al., 2022). Furthermore, government laws and policies are essential for protecting cultural heritage, Indigenous rights, traditional knowledge, and cultural sites (Hiswara et al., 2023).

Heritage, as stated by Olaniyan et al. (2024), is the collective representation of a people’s history, values, and traditions, shaped by internal and external influences. It embodies cultural identity and historical narratives and serves diverse roles, from preserving traditions to inspiring future generations. Heritage entails legacies from the past, what we live with today and what we pass on to future generations (Mekonnen et al., 2022). Heritage is a unique and irreplaceable asset that is critical to tourism, and this can be done by respecting heritage locations' original features, cultural significance, and historical context rather than altering them for tourist appeal. Preserving the true essence of heritage allows for meaningful experiences while ensuring these resources are protected for future generations (Vu Hoang, 2021).

3 Research methodology

This study aimed to evaluate users’ perceptions of the benefits of neo-vernacular architecture in selected arts and cultural centres. This was achieved with a survey administered through a structured questionnaire. The research surveys were conducted between December 2024 and January 2025, focusing on users of these cultural centres in Lagos. The study population were the stakeholders in the three selected cultural centres: the John Randle Centre for Yorùbá Culture & History, Terra Kulture and KAP Hub.

A purposive non-probability sampling method was used to select the centres based on two key criteria: cultural significance and architectural relevance to neo-vernacular design. Due to the dynamic nature of visitor attendance at these centres, a pilot study was conducted to estimate the total daily user population across the selected centres, and it was determined to be 170 users per day at all centres. 120 questionnaires were distributed across all centres after calculating the sample size using Taro Yamane’s formula; 110 were returned: 47 from the John Randle Centre, 33 from Terra Kulture and 30 from KAP Hub.

The questionnaire was divided into sections (A–E). Section A assesses the social-demographic characteristics of the respondents; Section B addresses cultural sustainability; Section C addresses environmental sustainability; Section D addresses economic sustainability; Section E addresses Social Sustainability.

Content validity of the questionnaire was ensured by aligning the items with the research objectives. The instrument was developed through a literature review on neo-vernacular architecture, user perception, and sustainability. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha, which measured the internal consistency of each item across the three case studies. Results showed acceptable to excellent reliability, with alpha values ranging from 0.718 to 0.934, confirming that the grouped items reliably captured each construct.

However, the John Randle Centre exhibited a notably lower Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.558 in the economic sustainability dimension. This can be attributed to several contextual and design-related factors. The centre only recently reopened to the public, which may have limited users’ exposure to its revenue-generating initiatives. As such, respondents may have lacked the direct experience or observational basis to evaluate their economic contributions confidently. In addition, several questionnaire items in the economic sustainability section, particularly those related to local employment, artisan visibility, cultural events, and community economic benefits, may have required familiarity with the centre’s internal operations or programming that casual visitors may not possess. For example, questions about whether local artisans were supported or whether the centre contributed to economic development might have been interpreted differently depending on how observant or informed the respondent was. This likely introduced response variability, thereby reducing internal consistency within this section. Nonetheless, the data from John Randle remains valuable for exploratory interpretation. The lower reliability reflects the centre’s transitional state and visitors’ limited familiarity with its economic role. These findings offer a valuable point of reflection for future assessments as the centre matures and its economic impact becomes more visible and measurable.

Descriptive statistics summarised socio-demographic data and user perceptions across sustainability dimensions. Normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests, with results indicating non-normal distribution. Consequently, the Kruskal–Wallis H test was employed to assess differences in perception across the three centres. Where significant differences were found, post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Conover, Dunn, and Tukey–Kramer (Nemenyi) tests, with adjustments made through the Holm (FWER) and Benjamini–Hochberg (FDR) methods to ensure the validity and reliability of multiple comparisons.

4 Results

4.1 John Randle Centre for Yorùbá Culture and History

The John Randle Centre for Yorùbá Culture and History, as shown in Figure 1, built to celebrate the past, present and future of the Yorùbá culture, lies at the heart of Onikan, consisting of Freedom Park, the National Museum of Lagos, and the Tafawa Balewa Square, a cultural quarter on Lagos Island in southwest Nigeria, is a cultural attraction that honours the Yorùbá people of Nigeria with stories, myths, and traditions of Yorùbá heritage, offering immersive experiences, from the dynamism of Yorùbá festivals to the rich visual culture of Yorùbá history and ancestry (Ralph Appelbaum Associates, n.d.; Singh, 2023).

Figure 1. View of the John Randle Centre. Source: (Ralph Appelbaum Associates, n.d.).

Before its regeneration, the John Randle Centre was built in 1928 as a swimming pool for Lagosians to learn how to swim due to the frequent drownings. A memorial hall was built in 1955 to honour John Randle’s memory. Due to neglect, these facilities became run-down and in disrepair. This led to a restoration project to repair the pool and memorial hall, as well as build a community centre with an exhibition hall.

The design and architectural expression of the centre are deeply rooted in the values and principles of Yorùbá culture, transforming them into visual metaphors. Located on a historically significant site, the architecture pays homage to its history and context, reflecting the Yorùbá belief in the interconnectedness of humans and nature. The building emerges from the ground as an extension of the landscape, reinforcing its cultural significance. The John Randle Centre for Yorùbá Culture and History occupies the site of the former Memorial Hall, and visitors enter the complex through a space beneath a rising monolith, which also serves as a gateway. The curving, ascending structure incorporates architectural elements that symbolise concepts from Yorùbá culture. Notably, the building tilts forward by nine degrees, representing Yorùbá progressiveness. The metal screen facade encasing the structure is a visual metaphor for Yorùbá craftsmanship, showcasing traditional skills such as fabric weaving, hair braiding, basket weaving, and metal forging art forms that still endure. Although Adobe was not structurally feasible for the project, concrete with a Tyrolean finish was used to evoke the texture and memory of traditional Yorùbá settlements (Singh, 2023).

The centre is structured around two primary buildings: the Museum building and the Memorial building, as shown in Figure 2. The Museum Building is intentionally designed with minimal windows to create a controlled atmosphere suited for its exhibits, which showcase Yorùbá heritage through immersive displays. On the other hand, the memorial building houses essential visitor facilities, including a ticketing and information area, offices, restrooms, a restaurant, a pool and an arcade game space. Large verandas extend the building’s usability, providing outdoor seating and relaxation areas. Beyond the built environment, the centre incorporates diverse outdoor spaces, including a green roof, bleacher stands, and a mini outdoor theatre, which serves as a venue for public events and cultural programming. These spaces are active during festive occasions such as Christmas and Children’s Day celebrations, contributing to the centre’s role as a dynamic community hub.

Figure 2. View of John Randle centre showing Yorùbá craftsmanship in metal work. Source: (Ralph Appelbaum Associates, n.d.).

4.2 Terra Kulture

Terra Kulture Arts and Studios was founded in 2003 by Mrs. Bolanle Austen-Peters as an educational and cultural hub promoting Nigerian languages, arts, and heritage. Noticing a gap in institutions that truly supported and celebrated the country’s cultural identity, she created Terra Kulture to offer a space where Nigerians and visitors could engage with the richness of local traditions. Over its first 11 years, the centre became a cultural hotspot, hosting over 200 art exhibitions, 135 stage plays, and 65 book readings. Its language classes also attracted over 10,000 participants, including many schoolchildren. Beyond performances and exhibitions, Terra Kulture expanded to include a Nigerian language and craft school, a reading and documentation centre, a local cuisine lounge, an art gallery, and the Terra Arena, its dedicated multipurpose theatre space. In 2009, it took another bold step by launching the Terra Kulture Auction House, one of just two in the country, regularly organising art auctions in Lagos and Abuja to support Nigerian artists and collectors further (Terra kulture, n.d.).

Terra Kulture’s layout is built to offer a rich, all-in-one cultural experience, combining spaces for art, theatre, food, and leisure. As guests enter, they enter an area with a restaurant, bar, and kitchen, setting a lively, welcoming tone for the visit. A gracefully curved staircase leads to the bookshop, art gallery, and administrative offices. The gallery showcases seasonal exhibitions of renowned Nigerian artists, allowing visitors to engage with and purchase authentic local artworks. The interior design incorporates reclaimed wood from the site, enhancing its aesthetic appeal while promoting eco-conscious architectural choices. Lush plants and vegetation further elevate the ambience, reinforcing a connection to nature. The restaurant, AKO by Terra, serves an exquisite menu of local Nigerian dishes, offering guests a culinary journey through Nigeria’s diverse flavours.

Behind the main building is the 400-seat Terra Arena, a state-of-the-art theatre space equipped with modern backstage facilities, dressing rooms, a waiting area, VIP seating, and additional offices. A long corridor with large windows ensures ample natural lighting while contributing to an inviting and immersive atmosphere. This theatre has hosted high-profile productions and artists, playing a pivotal role in the revival of live theatre in Nigeria.

Beyond its indoor attractions, Terra Kulture offers outdoor relaxation, as shown in Figure 3 and cultural event spaces. These areas are adorned with lush greenery and vibrant floral arrangements, which beautifully complement the centre’s signature bright orange façade, creating a serene yet dynamic setting. Even when no live performances are scheduled, the restaurant and outdoor spaces maintain a lively atmosphere, making the venue an ongoing hub for social and cultural engagement.

Figure 3. View of Terra Kulture. Source: (Terra kulture, n.d.).

Terra Kulture’s thoughtfully planned spatial organisation and diverse cultural offerings provide an immersive and enriching experience, celebrating Nigerian arts, cuisine, and heritage. The centre’s fusion of traditional aesthetics with contemporary functionality solidifies its position as a leading destination for cultural appreciation and artistic expression in Nigeria.

4.3 KAP Hub

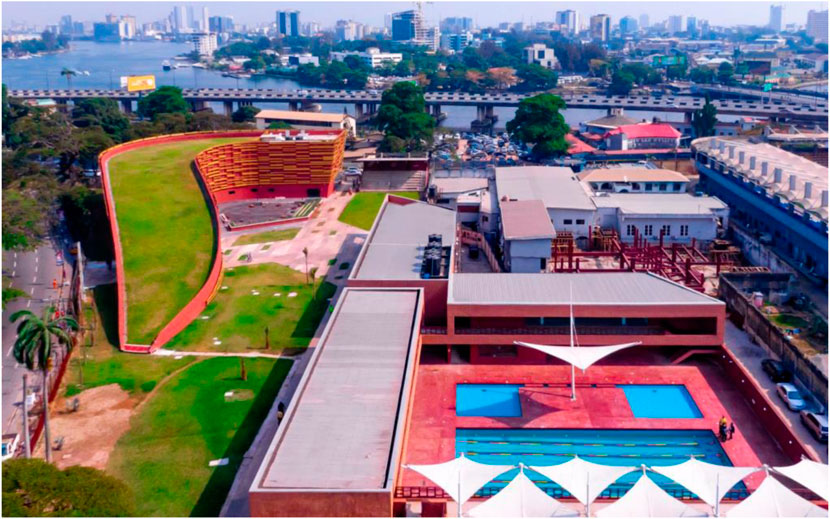

KAP Hub, short for Kunle Afolayan Production Hub, as shown in Figure 4, is a dynamic cultural centre founded by renowned filmmaker Kunle Afolayan in Lagos, Nigeria. Established in 2020, it serves as a creative hub for entertainment, film production, education, and hospitality under the umbrella of Golden Effects Services Limited. The hub houses KAP Motion Pictures, responsible for producing acclaimed films like Mokalik and Citation; KAP Film & Television Academy, which offers hands-on training in filmmaking; KAP Cinemas, a 120-seat premium cinema for screenings and events; KAP Television, a platform showcasing content from Afolayan’s productions; and KAP Sound Stage Studio, a soundproof facility for film shoots, stage plays, and exhibitions. The Afefeyéyé Restaurant & Bar mixes African and international dishes in a lively, relaxed atmosphere and stays open even after KAP Hub closes. The Hub reflects Afolayan’s passion for cultural heritage and creative growth, bringing film, art, and education together in one cohesive space (Kap Hub, 2020).

Figure 4. View of Kap Hub. Source: (BellaNaija, 2020).

The site comprises three separate buildings, each designed for a specific purpose to support the work of artists, staff, and visitors alike. At the entrance, murals of well-known Nigerian heroes and actors greet you, setting the tone for a space rooted in cultural pride. However, one downside is the lack of dedicated parking, meaning most people must park along the roadside. Within the complex, you will find the central administrative offices, KAP Studio for film production, and the Afefeyeye Restaurant & Bar.

The ground floor of the administrative building includes the reception, waiting area, open and private offices, and a kitchen, serving as the hub for managing the centre’s diverse activities. Adjacent to this is KAP Studio, featuring a soundstage with a control room, green room, changing rooms, and WC, creating a fully functional space for performances and film production. Additionally, Ire Clothings and Media Bookstore are in the same structure, offering visitors access to literature and fashion inspired by Nigerian culture. A metal staircase leads to the post-production unit, constructed from repurposed shipping containers, where students engage in video editing and media training. This container-based structure aligns with sustainability efforts. At the top level, the Afefeyeye rooftop bar offers a relaxing social space with open views, attracting young professionals and creatives.

The third building houses the Afefeyeye Restaurant & Bar, which offers an exquisite selection of rich African cuisine, with reclaimed wood interiors enhancing the centre’s commitment to eco-conscious design. Above the restaurant, the Afefeyeye rooftop bar is an open-air relaxation spot, leading to the 120-seat cinema, expanding the centre’s entertainment offerings. KAP Hub thrives as an economic and cultural hub, sustained by the cinema, restaurant, and outdoor gathering spaces, which ensure a constant flow of activity. While the adaptive reuse of materials, such as the shipping container section, contributes to sustainability, refining the cohesion between traditional and contemporary elements could further strengthen its architectural identity and functionality.

4.4 Section A: socio-demographic characteristics

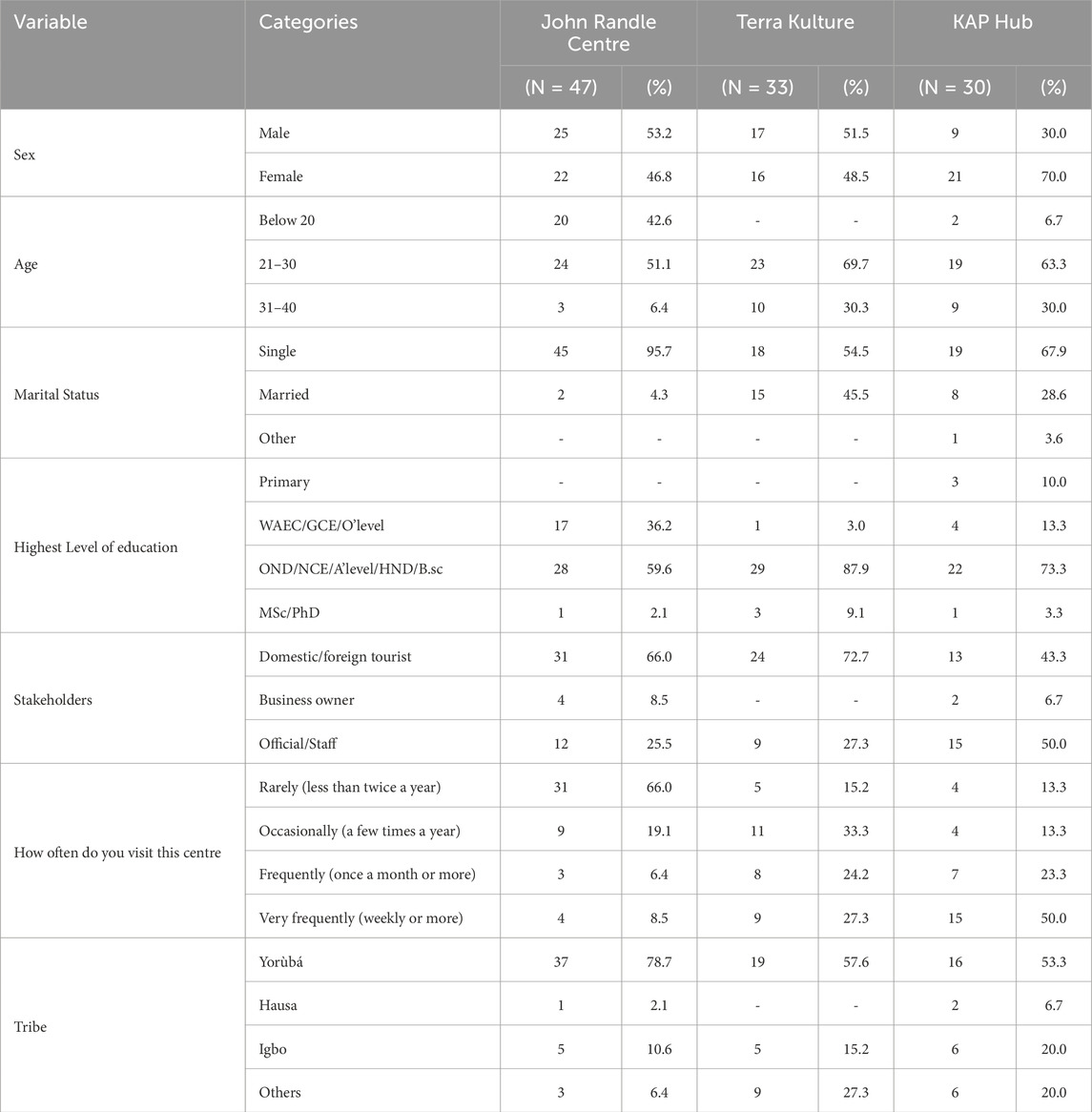

The socio-demographic profile across the three cultural centres, John Randle Centre, Terra Kulture, and KAP Hub in Table 1 reveals a youthful, educated, and culturally diverse user base, each venue showcasing unique engagement dynamics.

At John Randle Centre, the respondents (N = 47) were a balance of gender, with a slight male majority (53.2%). Most youth, over 93%, were under 30, and those below 20 (42.6%) and those aged 21–30 (51.1%). 95.7% were single, and nearly 60% held a tertiary qualification, suggesting a young, educated population exploring cultural offerings. The stakeholders were dominated by tourists (66%), followed by staff/officials (25.5%), while visitation was generally low, with 66% reporting rare visits. Most of the audience was Yorùbá (78.7%), with very few people from other ethnic groups.

Terra Kulture drew a more engaged but similarly youthful crowd. Of the 33 respondents, the gender split was nearly equal (51.5% male, 48.5% female). 69.7% fell within the 21–30 age range, with 54.5% single and 88% having at least a diploma or degree, marking it as a hub for educated young adults. Tourists again dominated (72.7%), and while 27.3% of users were staff/officials, no business owners were recorded. Visitation here was more frequent, with over 51% attending monthly or more, indicating higher engagement. The ethnic profile was slightly more varied: Yorùbá (57.6%), Igbo (15.2%), and a notable 27.3% from other groups, reflecting diversity.

KAP Hub, in contrast, stood out mainly with a female audience of 70% and a striking level of engagement; half of its 30 respondents visited weekly or more. Most of its users were aged 21–30 (63.3%), and 67.9% were single, maintaining the youth-heavy trend across centres. Tertiary education was dominant (73.3%), with a small share (3.3%) holding postgraduate degrees. Unlike the other centres, KAP Hub attracted the highest proportion of staff/officials (50%), while tourists comprised 43.3%, and business owners remained a minority (6.7%). This centre had more ethnic diversity. Yorùbá people comprised 53.3% of the respondents, while Igbo and other groups comprised 20%, and Hausa comprised 6.7%. This shows the centre attracts people from across the country.

4.5 Section B: cultural sustainability

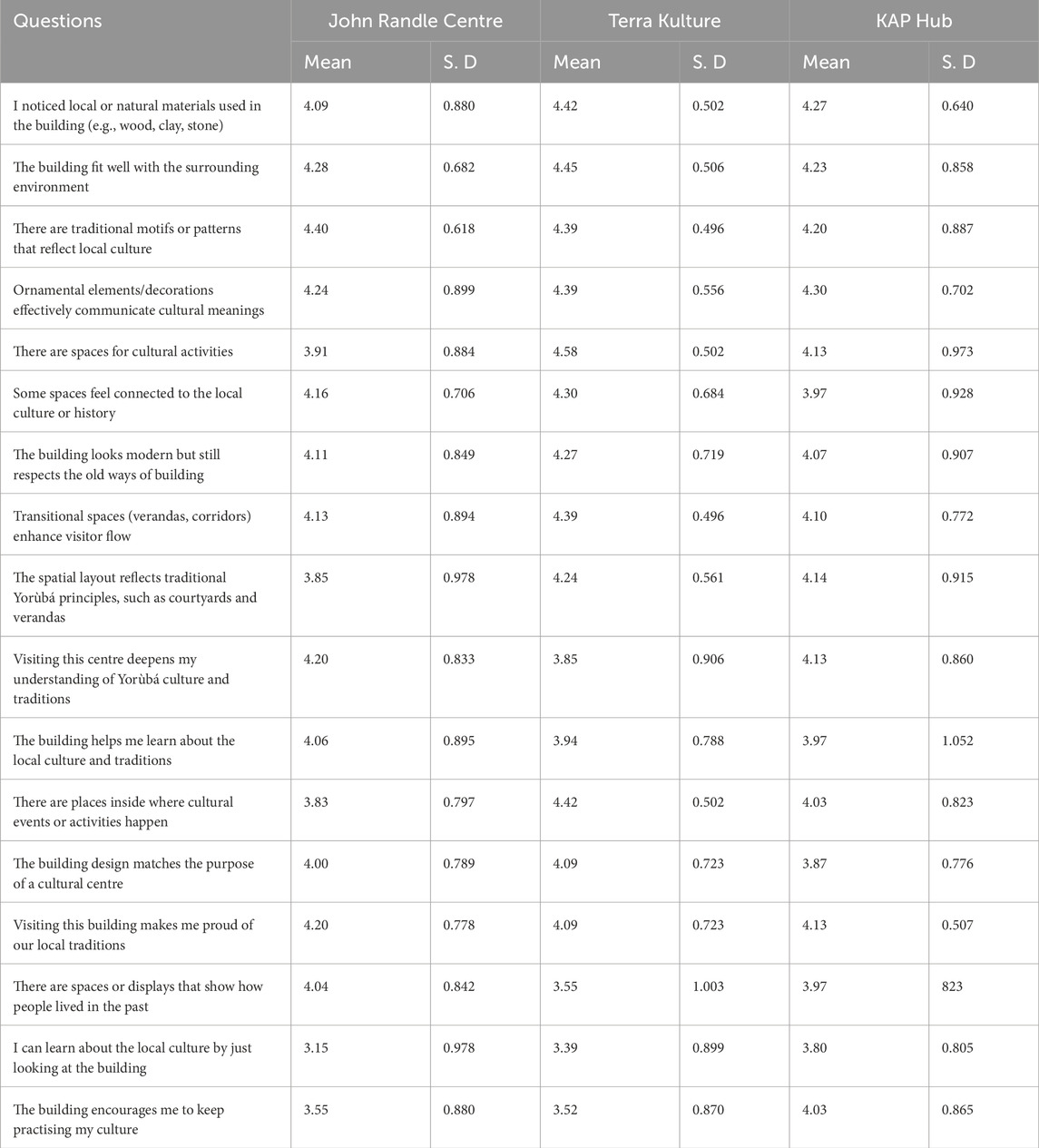

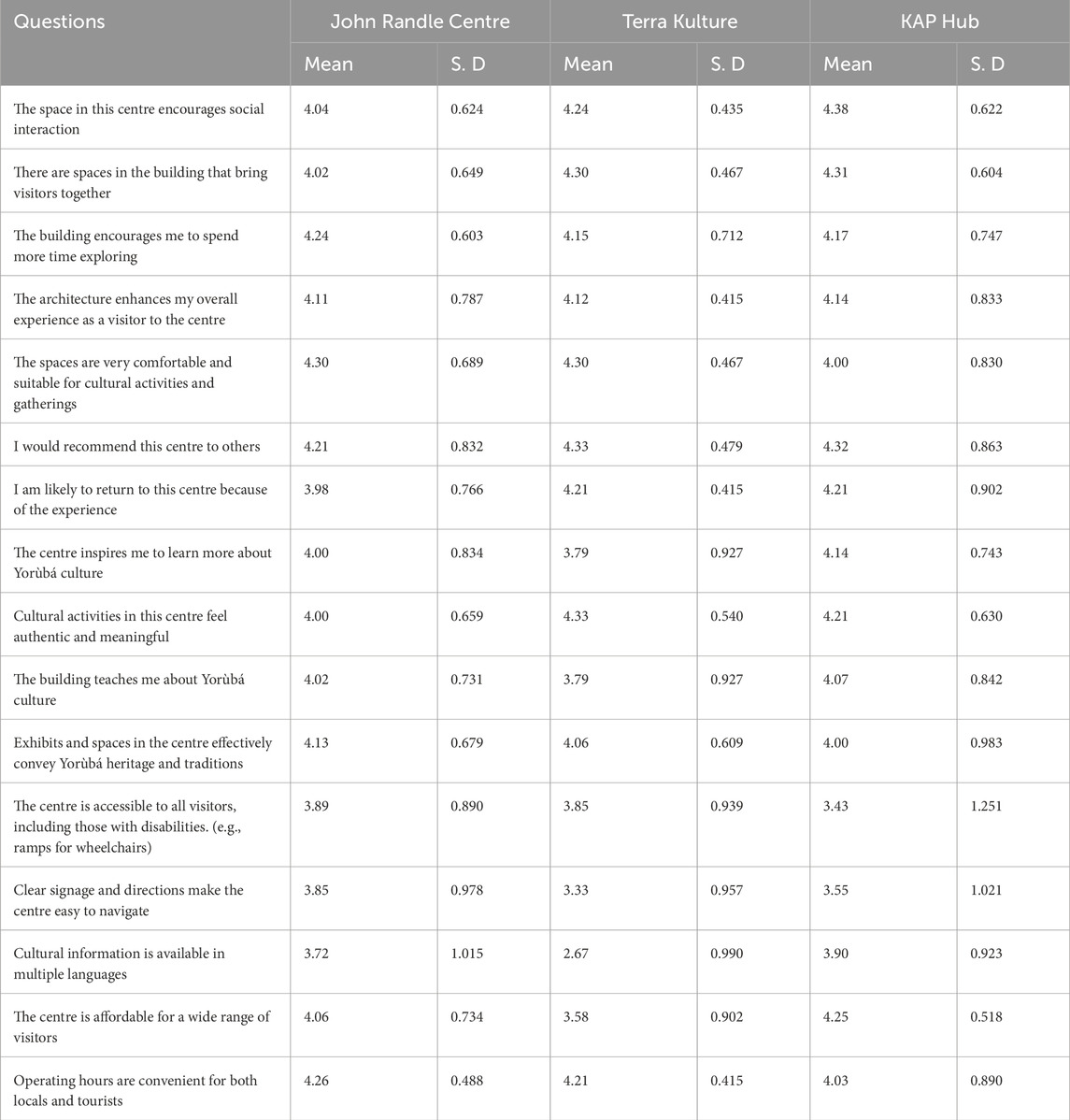

Table 2 presents an analysis of cultural sustainability as perceived by users of three arts and cultural centres in Lagos: the John Randle Centre, Terra Kulture, and KAP Hub. Cultural sustainability reflects the extent to which architectural design communicates, preserves, and promotes cultural identity, particularly Yorùbá heritage and responses were based on participants’ observations and experiences within the centre.

In the John Randle Centre, respondents recognised using local and natural materials such as wood, reinforcing a sense of place. The building was also perceived as harmoniously integrated with its surroundings, enhancing users' cultural experience. Traditional motifs and ornamental features were noted for successfully communicating cultural meanings, as symbolic aesthetics were meaningfully integrated within the design. While users acknowledged the presence of transitional spaces such as verandas and corridors, elements that align with traditional Yorùbá spatial architecture, the spatial layout did not portray a strong resemblance to Yorùbá architecture. Courtyards were present, and visitors felt that the architecture contributed positively to their understanding of Yorùbá culture through the museum showcase, with many expressing a sense of pride in local traditions. However, respondents were divided on the building’s ability to educate users about culture through its form. Although the architecture respected traditional building methods, the centre relied heavily on programmatic content, such as exhibitions or events, to fully express its cultural mission.

Terra Kulture had the highest score in terms of cultural sustainability, with users reporting a high satisfaction with the available spaces for cultural activities, showing that the centre functions as a vibrant space for cultural expression through shows, theatre and dance. Natural materials such as wood, stone, etc., were evident in the centre, reinforcing its cultural resonance. Traditional motifs and transitional spatial elements (corridors and verandas) reflecting Yorùbá design principles were also recognised. Despite its strengths, some respondents felt that Terra Kulture’s design could do more to inspire individual cultural practice through educational workshops.

KAP Hub’s cultural sustainability score was a balance between contemporary expression and traditional expression. Users highlighted the presence of materials such as wood and sculptures, and noted that the building was well integrated into its surroundings. Decorative and symbolic elements such as patterns and motifs were evident in the design, enhancing its cultural identity. The spatial arrangement of the building reflected Yorùbá design patterns through the use of verandas and courtyards for a clear transitional movement between areas. Users felt these elements contributed meaningfully to their understanding of Yorùbá traditions. KAP Hub was the only centre where many users indicated that the design actively encouraged them to continue practising their culture, implying a stronger personal connection fostered through the architectural experience. Although some participants noted that the building did not fully communicate cultural lessons, most highlighted the centre’s role in evoking cultural memory and reinforcing identity through form and function.

4.5.1 Summary of cultural sustainability

Cultural sustainability across the different sites varied, with the John Randle Centre being strongest regarding material authenticity and cultural pride, but it had less prominent traditional layout components. Terra Kulture had strengths in functional cultural engagement, with many events and performance spaces, but slightly fewer symbols of indigenous presence. KAP Hub had the most balanced form, material, and symbolism connections with any of the centres. However, it achieved this in such a way as to produce a culturally sustainable space for reflection and for active cultural practice to occur. These results demonstrate the significance of building design as a context for cultural programs and an active participant in retaining and transmitting indigenous cultures.

4.6 Section C: environmental sustainability

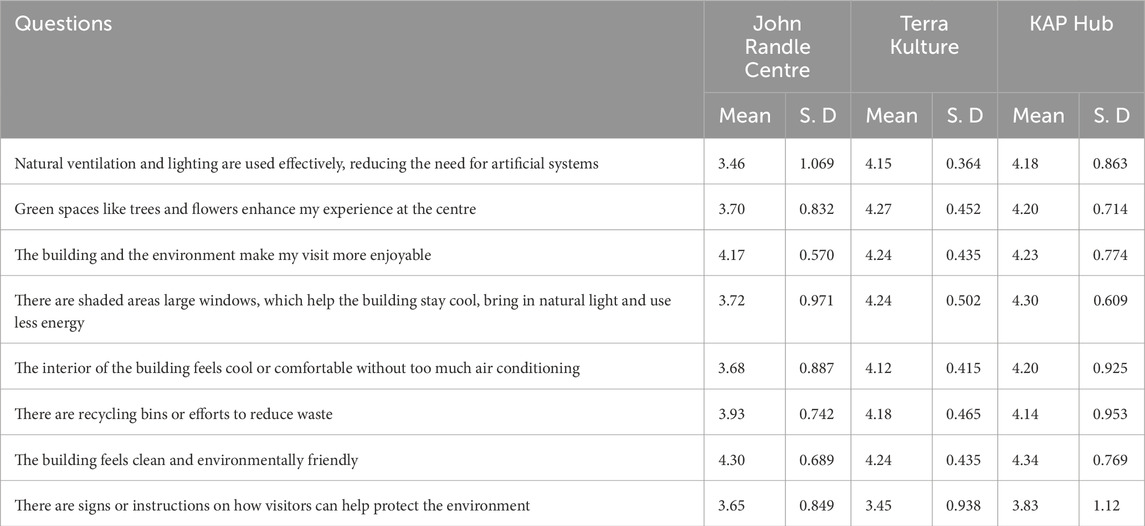

Table 3 present an analysis of Environmental sustainability as perceived by users of three arts and cultural centres in Lagos: the John Randle Centre, Terra Kulture, and KAP Hub. Environmental sustainability reflects how building design and operational plans facilitate energy efficiency, indoor environmental quality, connection to natural elements, Landscape, waste management, and visitor involvement in sustainability practices.

Respondents viewed the John Randle Centre as a clean and green environment that enhances their experience with its extensive green roof and native plants, connecting the users to nature. Building features such as large windows and shaded areas were identified to enhance natural lighting and cooling. Passive measures, such as natural ventilation, were rated medium, with thermal comfort well rated, mainly because of reliance on mechanical ventilation systems. Recycling was dominant and identified by users, demonstrating an operational drive for waste reduction. Environmental communication was lower for the centre by scores, with visitors perceiving they had no clear signage or direction on how they could contribute to sustainability for their visit.

At Terra Kulture, users strongly agreed with the centre’s environmental sustainability measures. Greenery and natural features, such as wooden chairs, tables, and bamboo-patterned ceilings, contributed to aesthetic appeal and visitor comfort. Natural cooling and daylighting were promoted by using large windows and shaded outdoor spaces, minimising unnecessary air-conditioning usage. The centre was considered clean and green and ran well on an operational level. Nonetheless, like the John Randle Centre, environmental signage or visitor guidance was scored lowest, as minimal efforts were made to educate or engage visitors on sustainable practice. While Terra Kulture successfully integrates environmental sustainability into physical building design, it could better engage visitor awareness and behaviour change.

Users of KAP Hub recognised the centre’s use of passive design strategies, such as natural ventilation and lighting, which contributed to reduced reliance on mechanical cooling and enhanced occupant comfort. The presence of greenery was positively received and contributed to an inviting atmosphere. Architectural features such as large windows and shaded spaces were integral to the building’s ability to maintain a comfortable indoor climate while minimising energy consumption. The centre was described as clean and environmentally friendly, reinforcing its sustainable image. However, despite visible recycling bins and waste reduction efforts, respondents did not strongly emphasise these features, suggesting a lack of awareness. Environmental signage and visitor engagement in sustainability practices also received relatively low scores.

4.6.1 Summary of environmental sustainability

In each of these centres, architectural and operational practices establish effectively a standard of environmental sustainability based on cleanliness, integration of green spaces and passive building elements, enhancing natural lighting and ventilation. However, common weaknesses emerged around visitor engagement and education, with environmental signage and behavioural guidance consistently underperforming.

These findings reveal that while physical design and maintenance contribute positively to environmental quality, arts and cultural centres must extend their sustainability agenda beyond infrastructure. Active communication strategies and user involvement are critical to transforming passive environmental features into shared responsibility and more meaningful, sustainable practice.

4.7 Section D: economic sustainability

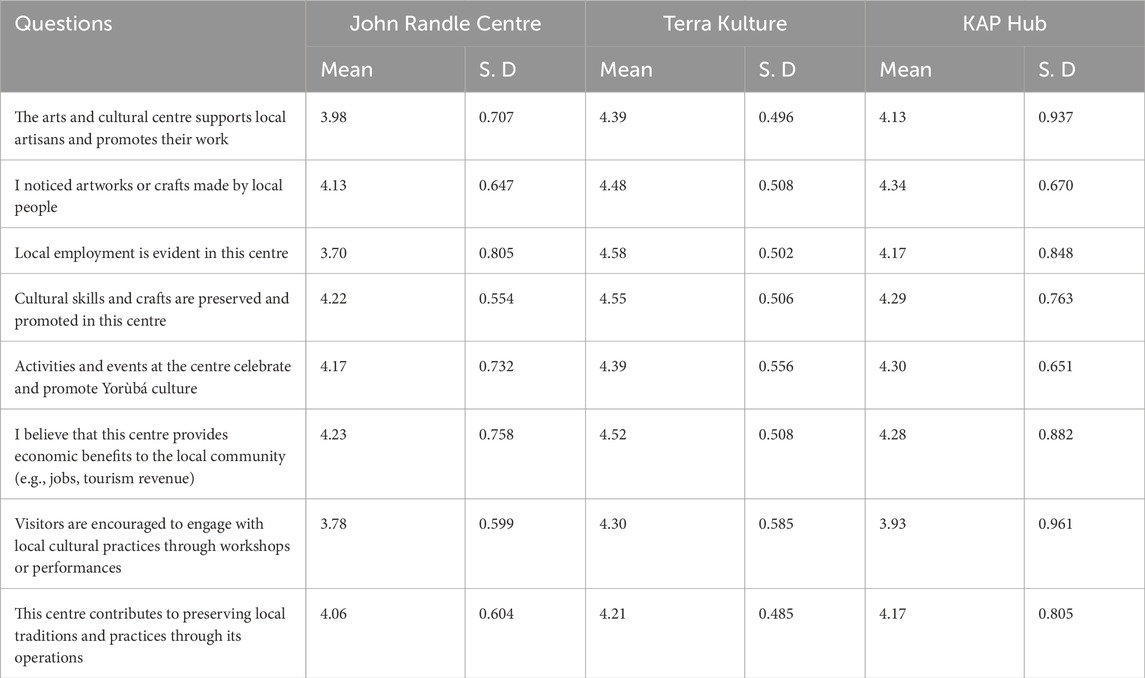

Table 4 examines user perceptions of economic sustainability at the John Randle Centre, Terra Kulture, and KAP Hub. Economic sustainability shows how these centres support local artisans, preserve cultural skills, foster employment, and contribute to the broader local economy.

Respondents recognised the John Randle Centre as a place evident with local artisans, with many noticing visible displays of locally crafted artworks, affirming that indigenous creativity is showcased and economically supported. Users strongly agreed that the centre actively preserves and promotes cultural crafts and skills, reinforcing its role in sustaining cultural heritage as a living economic resource. Events and activities celebrating Yorùbá culture were highlighted as necessary, functioning not only as cultural expressions but as economic drivers that engage visitors and empower local communities. Despite these positive views, the perception of local employment was somewhat moderate, suggesting that while locals are engaged, the extent or visibility of employment opportunities might not be fully apparent. Visitor engagement through workshops or performances was rated positively, but there is room to deepen participatory experiences. Overall, users believed the centre generates tangible economic benefits for the community via job creation, tourism revenue, and cultural commerce, positioning it as an active agent of economic empowerment rather than a mere cultural showcase.

At Terra Kulture, users strongly affirm the centre’s role in improving the local economy and cultural sector. The highest ratings concerning visible local employment underscore the centre’s contribution to job creation. Similarly, users noted the prominent presence of locally made artworks and the centre’s efforts to preserve and promote cultural skills, confirming a supportive environment for local artisans and creatives. Respondents also agreed that Terra Kulture delivers economic benefits to the surrounding community through tourism and employment. The centre’s events and programming were recognised for celebrating Yorùbá culture, further linking cultural promotion with economic sustainability. Visitor engagement opportunities such as workshops and direct interaction with cultural practices were rated positively but less strongly, suggesting that while economic and cultural support is evident, there remains potential to enhance interactive and immersive experiences that connect visitors more deeply with local traditions.

Users at KAP Hub similarly perceived the centre as a vital contributor to economic sustainability through support of local artisans and visible promotion of their crafts, enriching the visitor experience while providing income and recognition for local artists. The centre was seen as a source of local employment and an essential venue for preserving cultural skills and Yorùbá traditions through festivals, exhibitions, and performances. Respondents agreed that KAP Hub supports the local economy by generating tourism revenue and creating jobs. However, engagement with visitors through participatory cultural workshops or hands-on demonstrations was low, indicating an area for growth in fostering active visitor involvement. This presents an exciting opportunity for KAP Hub to deepen cultural connections and enhance economic impact through experiential tourism in the future.

4.7.1 Summary of economic sustainability

Across all three centres, users consistently acknowledged that economic sustainability is strongly tied to supporting local artisans, preserving cultural crafts, and providing employment opportunities. The centres are viewed not merely as exhibition spaces but as dynamic engines of economic activity, intertwining cultural heritage with community livelihood.

Nonetheless, interactive visitor engagement through workshops, performances, and participatory events emerged as the weakest link, suggesting that enhancing these experiential opportunities could unlock greater economic and cultural benefits. By fostering deeper visitor involvement, the centres can amplify their role as sustainable economic and cultural hubs in Lagos.

4.8 Section E: social sustainability

In Table 5 Respondents generally perceive the John Randle Centre as a vibrant social hub, where architecture and spatial design encourage visitors to connect and engage. The centre’s layout and atmosphere support exploration and meaningful social encounters, making it more than just a place to observe culture, but a place to experience community. Comfortable gathering spaces are valued highly, serving as suitable venues for cultural events and social interaction. Visitor loyalty is strong, reflected in their willingness to recommend the centre and return for future visits. While cultural activities are seen as authentic and meaningful, enriching visitors’ understanding of Yorùbá culture, some aspects of accessibility, such as provisions for people with disabilities and clarity in signage, could be improved. Additionally, multilingual cultural information is limited, suggesting room to broaden the centre’s reach. Nonetheless, the affordability and convenient operating hours ensure that the centre remains accessible to a broad audience.

The data from Terra Kulture reveals a strong communal atmosphere, with users feeling that the centre fosters social interaction and connection. The building’s design promotes comfort and functionality, supporting a range of cultural gatherings and encouraging visitors to immerse themselves in the space. While respondents generally feel positive about the authenticity of cultural activities, there is slightly less certainty about the centre’s role in explicitly educating visitors about Yorùbá heritage, pointing to potential enhancements in interpretive and interactive features. Accessibility measures and multilingual information received moderate ratings, indicating that while the centre mainly accommodates, improvements could help serve a more diverse visitor base. Affordability is reasonable, yet some barriers to access remain.

At KAP Hub, respondents affirm that the centre is an engaging social space, where architecture and communal areas naturally facilitate visitor interaction and cultural exchange. The centre’s ambience supports extended visits and fosters curiosity about Yorùbá culture, with cultural activities perceived as authentic and meaningful. High levels of visitor satisfaction are evident in the strong likelihood of recommendations and repeat visits. However, there are some gaps in inclusivity, especially for disabled visitors, who may find access and navigation challenging due to unclear signage and limited support features. The lack of multilingual cultural materials could also make it harder for non-local audiences to engage fully. These issues highlight the potential for KAP Hub to improve its social accessibility, demonstrating the centre’s commitment to inclusivity and diversity.

4.8.1 Summary of social sustainability

Across the three centres, social sustainability was evident through intentional spatial planning and culturally sensitive programming. The John Randle Centre stood out for its inclusive design and ability to accommodate communal activities and increase cultural understanding through its museum and heritage centre. However, users recorded some limitations in signage and wayfinding. Terra Kulture proved extensive user satisfaction by providing comfortable and sociably engaging spaces; yet, its potential for conducting more engaging and inclusive cultural teaching could also be explored further. KAP Hub exhibited a dynamic atmosphere that resonated well with users. However, challenges related to accessibility and language inclusivity were present.

These findings highlight that social sustainability extends beyond physical infrastructure to encompass how diverse users perceive, inhabit, and understand spaces. While each centre reflects an effort to support community interaction and cultural continuity, advancing equity will require deliberate strategies, such as inclusive design interventions and multilingual content, to ensure broader and more meaningful participation. This underscores the urgency and importance of this goal in the context of social sustainability.

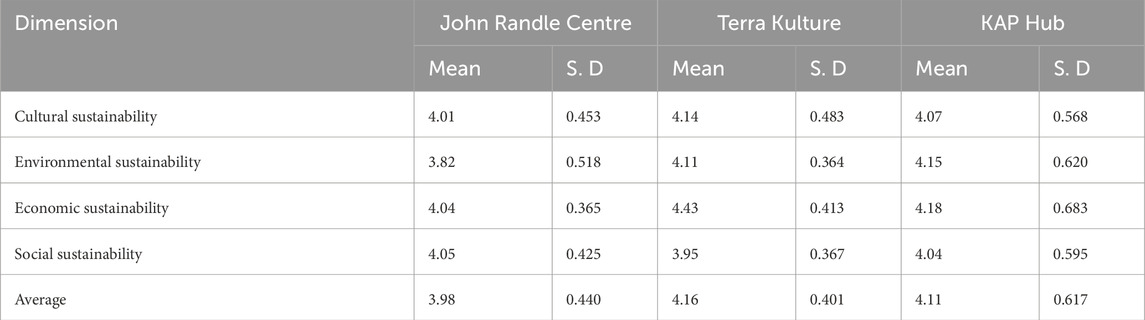

4.9 Aggregate score category

Table 6 the comparative analysis of user perceptions across the three selected arts and cultural centres. It highlights their strengths in how neo-vernacular architecture contributes to perceived cultural, social, economic, and environmental benefits as reflected in the mean scores.

Terra Kulture records the highest average aggregate score (4.16), with its strongest performance in economic sustainability (4.43). This reflects the centre’s successful integration of cultural enterprise, local employment, and support for creative industries through its multifunctional programming. The result suggests that Terra Kulture is a leading example of how cultural infrastructure can be leveraged for economic development within a tourism and heritage context.

KAP Hub follows closely with an average of 4.11, achieving its highest environmental (4.15) and economic sustainability (4.18) scores. The high environmental rating reflects the centre’s conscious incorporation of eco-friendly design elements such as passive cooling and landscape integration, while maintaining strong economic performance through support for local artisans and creative professionals. KAP Hub demonstrates a balanced approach to sustainability, with relatively consistent scores across all four dimensions.

With an average score of 3.98, John Randle Centre performs strongest in social (4.05) and economic sustainability (4.04). The high social sustainability rating indicates user satisfaction with the centre’s ability to facilitate community engagement, knowledge-sharing, and interaction. Cultural sustainability also received favourable ratings, though environmental sustainability scored the lowest relative to the other dimensions, indicating potential for improvement in ecological practices and visitor education.

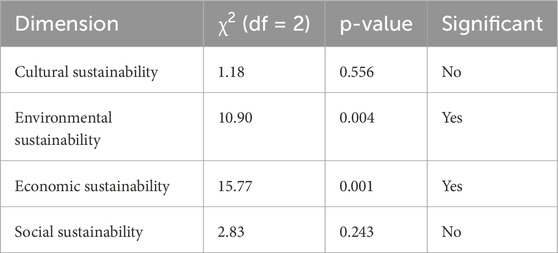

4.10 Non-parametric inferential statistics

A Kruskal–Wallis H test was conducted for each sustainability dimension to determine whether the observed differences in mean perception scores across the three cultural centres were statistically significant. Prior normality tests (Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov) confirmed that the data violated the assumption of normal distribution (p < 0.05), thereby justifying the use of non-parametric methods.

These results in Table 7 show statistically significant differences in user perceptions only in environmental and economic sustainability across the three centres. The differences in mean scores were not statistically significant for cultural and social sustainability.

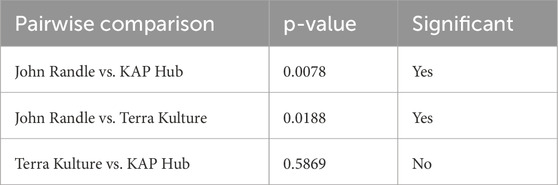

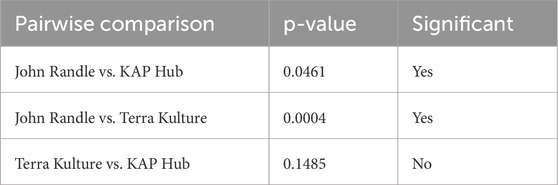

Since statistically significant differences were observed in the environmental and economic sustainability dimensions, post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Conover, Dunn, and Tukey–Kramer (Nemenyi) tests. To control Type I error, P-values were adjusted using Holm’s Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) and the Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) methods, as shown in Tables 8, 9.

Post-hoc pairwise tests consistently revealed significant differences between the John Randle Centre, KAP Hub, and Terra Kulture (p < 0.05 across Conover, Dunn, and Nemenyi methods). However, no significant difference was observed between Terra Kulture and KAP Hub, indicating that users perceived similar levels of environmental sustainability in both centres, while John Randle’s was notably distinct.

Post-hoc pairwise tests consistently revealed significant differences between John Randle Centre, KAP Hub, and Terra Kulture (p < 0.05 across Conover, Dunn, and Nemenyi methods). However, no significant difference was observed between Terra Kulture and KAP Hub, indicating that users perceived similar levels of economic sustainability in both centres, while John Randle’s was notably distinct.

5 Discussion

The Kruskal–Wallis H test revealed statistically significant differences in users’ perceptions of economic and environmental sustainability across the three centres. At the same time, the social and cultural dimensions showed no significant variation. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons confirmed that Terra Kulture and KAP Hub were rated significantly higher than the John Randle Centre in economic and environmental terms, with no notable difference between the leading centres. These findings were consistent with the aggregate mean scores, offering a broader perspective on each centre’s sustainability profile.

Terra Kulture recorded the highest average score (4.16), with its strongest performance in economic sustainability (4.43). This likely reflects the centre’s multifunctional infrastructure, as it combines cultural programming such as exhibitions, performances, and film screenings with income-generating components such as a theatre, bookstore, restaurant, and art gallery. Terra Kulture supports local employment, tourism, and creative enterprise by integrating commerce and culture, contributing to users’ positive economic evaluations.

KAP Hub followed closely with an overall score of 4.11, receiving its highest rating in environmental sustainability (4.15). Users responded favourably to its form, passive cooling, and landscape integration elements that align with climate-responsive strategies found in neo-vernacular architecture.

Although the John Randle Centre received the lowest overall score (3.98), it was rated highest in social sustainability (4.05), suggesting users value its role in fostering communal experiences. While its environmental sustainability was rated least (3.82), users responded positively to aspects such as natural lighting, green spaces, and thermal comfort, pointing out missing elements like recycling bins and signage promoting environmentally conscious behaviour. To address these gaps, cultural centres should consider utilising interpretive signage to highlight features like passive ventilation, local materials, or sustainable construction techniques. Marked recycling stations and interactive programmes, such as guided sustainability tours or exhibitions, could also enhance environmental awareness and engagement.

On the economic dimension, respondents recognised features that promote local artisans, celebrate Yoruba culture, and contribute to job creation and tourism. These perceptions highlight the value of combining cultural programming with economic opportunity to enhance positive economic sustainability outcomes. However, a lower score at the John Randle centre suggests opportunities to strengthen economic impact. Cultural hubs can enhance this by showcasing more visible artworks and products made by local artisans, offering artist-in-residence programmes, or creating dedicated spaces for cultural workshops and performances. Promoting these features more clearly may increase user perception of the centre’s economic relevance and strengthen local creative economies.

Regarding social sustainability, responses were consistently positive across all three centres, with users appreciating spatial layouts that encourage interaction, cultural learning, and authentic engagement with Yoruba heritage. Still, some items, such as affordability, accessibility for persons with disabilities, and multilingual cultural information, revealed variation in user satisfaction. To address these, cultural centres should prioritise inclusive design features such as ramps, affordable ticketing, and expanded operating hours. Adding multilingual guides, tactile exhibits, or audio-visual storytelling rooted in Yoruba culture would further enhance cultural accessibility and engagement, especially for tourists and diverse user groups.

Although all three centres incorporate neo-vernacular elements such as symbolic motifs, spatial layouts inspired by traditional architecture, and the use of local materials, only Terra Kulture and KAP Hub appear to extend these principles into integrated, performative systems that deliver tangible sustainability outcomes. These findings suggest that neo-vernacular architecture must move symbolic or aesthetic gestures and embody operational sustainability across economic, environmental, and social dimensions.

For architects and policymakers, the findings highlight the importance of aligning cultural authenticity with functional performance. Neo-vernacular design should be approached as a medium for heritage expression and a platform for delivering measurable benefits, such as energy efficiency, economic vitality, and social inclusivity. By connecting architectural identity to functional strategies like waste-conscious infrastructure, local economic integration, and inclusive programming, cultural centres can amplify the impact of their neo-vernacular approach.

While perceptual data provides valuable user insight, the study’s reliance on subjective responses introduces limitations that may be influenced by visitor familiarity or exposure. Additionally, the absence of longitudinal data constrains the ability to assess evolving perceptions over time. While this study is grounded in user perceptions and quantitative data, future research would benefit from triangulating these findings with interviews, economic impact reports, and in-depth case studies to strengthen interpretative validity. Mixed-method approaches integrating performance metrics such as energy use, artisan revenue, and program frequency with user feedback would provide a more comprehensive evaluation of neo-vernacular architecture’s long-term impact on cultural infrastructure.

6 Conclusion

This study examined user perceptions of sustainability across three arts and cultural centres in Lagos, John Randle Centre, Terra Kulture, and KAP Hub, through neo-vernacular architecture. The findings affirm that while all three centres contribute meaningfully to sustainable cultural tourism, they do so in distinct ways. Terra Kulture was perceived most favourably due to its commercial-cultural hybrid model that supports economic sustainability. KAP Hub demonstrated a balanced sustainability profile, with strengths in environmental and economic sustainability. In contrast, despite lower environmental ratings, the John Randle Centre was noted for its strong capacity to foster community engagement and social cohesion.

These outcomes underscore the diverse ways neo-vernacular strategies are interpreted and operationalised. However, the reliance on perceptual data presents inherent limitations, as subjective, situational, or temporal factors often shape user experiences. To strengthen the evidence base, future research should integrate objective performance metrics, such as energy efficiency, spatial adaptability, and programmatic outcomes, to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of neo-vernacular design. Such a mixed-methods approach would support a more comprehensive understanding of how traditional architectural principles can be reimagined to deliver cultural meaning and measurable sustainability within contemporary urban environments.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

FJ: Supervision, Writing – review and editing. CE: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude for the assistance extended by the Covenant University Centre for Research, Innovation, and Discovery (CUCRID) in facilitating the publication of this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author(s) verify and take full responsibility for the use of generative AI in the preparation of this manuscript. Generative AI tools were used to support the writing process to help organise ideas, improve clarity, and refine the flow of the manuscript. All key ideas, research design, data analysis, and interpretations are original and fully developed by the authors.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adebamowo, M., and Adejumo, T. (2012). “Environmental harmony and the architecture of ‘place’ in Yoruba urbanism,” in Design and nature VI. WIT Press.

Adedayo, O., Ayuba, P., and Audu, H. I. (2013). User perception of location of facilities in public building design in selected cities in Nigeria. Archit. Res. 2013, 62–67. doi:10.5923/j.arch.20130304.02

Adedokun, A. (2014). Incorporating traditional architecture into modern architecture: case study of Yoruba traditional architecture. Available online at: http://www.ajournal.co.uk/HSpdfs/HSvolume11(1)/HSVol.11%20(1)%20Article%204.pdf (Accessed August 8, 2024).

Adenaike, F. A., Opoko, A. P., and Oladunjoye, K. G. K. (2020). A documentation review of Yoruba Indigenous architectural morphology. Int. J. Afr. Asian Stud. doi:10.7176/JAAS/66-05

Adeokun, C. O., Ekhaese, E. N., and Isaacs-Sodeye, F. (2013). “Space use patterns and building morphology in Yoruba and Benin domestic architecture: a study of two cultures in South-West Nigeria,” in Proceedings of the ninth international space syntax symposium. Editor Y. O. Kim, H. T. Park, and K. W. Seo (Seoul, South Korea: Sejong University Press).

Agarez, R. C. (2014). Regionalism, Modernism and Vernacular Tradition in the Architecture of the Algarve, Portugal, 1925-1965. ABE J. Archit. Beyond Europe. doi:10.4000/abe.4132

Agyeiwaah, E., McKercher, B., and Suntikul, W. (2017). Identifying core indicators of sustainable tourism: a path forward? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 24, 26–33. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2017.07.005

Ahmed, S. (2022). Critical regionalist approach to architecture: lessons to be learnt from three case studies from Karachi. J. Archit. Plan. King Saud Univ. 34 (1). doi:10.33948/JAP-KSU-34-1-5

Akande, A. (2020). Manifestations of Orí (Head) in traditional Yorùbá architecture. IAFOR J. Cult. Stud. 5 (2), 5–19. doi:10.22492/ijcs.5.2.01

Antolini, F., Terraglia, I., and Cesarini, S. (2024). Integrating multiple data sources to measure sustainable tourism in Italian regions. Socio-Economic Plan. Sci. 95, 101959. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2024.101959

Bartha, B. (2020). Neo-vernacular architectural and furnishing patterns of Europe concepts for value-adding in contemporary design. 16.

BellaNaija (2020). Kunle Afolayan has a new production company & film academy. Let Him Take You on a Tour. Lagos, Nigeria: BellaNaija. Available online at: https://www.bellanaija.com/2020/06/kunle-afolayan-kap-hub/ (Accessed June 15, 2020).

Blancas, F. J., and Lozano-Oyola, M. (2022). Sustainable tourism evaluation using a composite indicator with different compensatory levels. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 93, 106733. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106733

Budeanu, A., Miller, G., Moscardo, G., and Ooi, C.-S. (2016). Sustainable tourism, progress, challenges and opportunities: an introduction. J. Clean. Prod. 111, 285–294. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.027

Chairuniza, C., Hartanti, N. B., and Topan, M. A. (2020). Net-zero energy building application in Neo- vernacular architecture concept. Int. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 9(03), 2056–2060. Available online at: https://www.ijstr.org/research-paper-publishing.php?month=mar2020.

Costanzo, D. (2012). Venturi and scott brown as functionalists: Venustas and the decorated shed (in Wolkenkuckucksheim—Cloud Cuckoo-Land: international journal of architectural theory). 17, 9–25.

Ediae, O. J., Abeng, F. J., and Egbudom, J. C. (2022). User experience of architectural promenade in art and cultural centres in Calabar, Crossriver State, Nigeria. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1054 (1), 012029. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1054/1/012029

Fu, M., Huang, S., and Ahmed, S. (2024). Assessing the impact of green finance on sustainable tourism development in China. Heliyon 10 (10), e31099. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31099

Hiswara, A., Aziz, A. M., and Pujowati, Y. (2023). Cultural preservation in a globalized world: strategies for sustaining Heritage. West Sci. Soc. Humanit. Stud. 1 (03), 98–106. doi:10.58812/wsshs.v1i03.250

Jamil, M., Shahzad, K., and Mustafa, A. (2024). Paradigm shift of construction techniques from vernacular to Neo—Vernacular in villages to sustain climate change. Pak. Soc. Sci. Rev. 8 (2). Article 2. doi:10.35484/pssr.2024(8-II-S)07

Jolaoso, B., Mai, , Umaru, A., and Bello, A. (2019). An evaluation of vanishing features of Yoruba traditional residential architecture in the 21st century. Archiculture 2, 22–23.

KapHub (2020). Our history. KapHubNews. Available online at: https://kaphubnews.com/?page_id=4668 (Accessed February 23, 2025).

Kurniati, R., and Nurini, N. (2024). Sustainable tourism in cultural heritage areas: dualism between economy and environmental preservation. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1394 (1), 012008. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1394/1/012008

Lee, T. H., Jan, F. H., and Liu, J. T. (2021). Developing an indicator framework for assessing sustainable tourism: evidence from a Taiwan ecological resort. Ecol. Indicat. 125, 107596. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107596

Lindarto, D., and Joel, P. (2019). Application of neo vernacular architecture in tongging agrotourism planning. J. Koridor 10 (2), 79–84. doi:10.32734/koridor.v10i2.1351

Makhloufi, S., Meliouh, F., Hamel, K., Nasri, M., Ghanemi, F., and Sekhri, A. (2024). Integrating tradition and modernity: a critical examination of neo-vernacular architecture in Algeria’s arid regions. South Fla. J. Dev. 5 (12), e4799. doi:10.46932/sfjdv5n12-037

Manao, A., Fitri, R., and Novalinda, (2022). The design of the south nias cultural center with a neo-vernacular approach. INFOKUM 10 (03). Available online at: https://infor.seaninstitute.org/index.php/infokum/article/view/797

Mekonnen, H., Bires, Z., and Berhanu, K. (2022). Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Herit. Sci. 10 (1), 172. doi:10.1186/s40494-022-00802-6

Memmott, P., and Davidson, J. (2008). Exploring a cross-cultural theory of architecture. Traditional Dwellings Settlements Rev. 19 (2), 51–68. Availble online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41758527.

Motalebi, Gh., Khajuei, A., and Fanaei Sheykholeslami, F. (2023). The effective factors on place attachment in residential environments. Int. J. Hum. Cap. Urban Manag. 8 (3). doi:10.22034/IJHCUM.2023.03.06

Narein, P., and Nirma, S. (2017). Good reading light: visual comfort perception and daylight integration in library spaces. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321719388_Good_Reading_Light_Visual_Comfort_Perception_and_Daylight_Integration_in_Library_Spaces (Accessed February 22, 2024).

Nemati Nasab, M. R., Sattari Sarbangholi, H., Pakdelfard, M. R., and Jamali, S. (2024). Evaluating the urban cultural spaces based on environmental quality components case study: tabriz city. Int. J. Nonlinear Analysis Appl. 15 (9). doi:10.22075/ijnaa.2023.31466.4635

Obradović, S., Stojanović, V., Kovačić, S., Jovanovic, T., Pantelić, M., and Vujičić, M. (2021). Assessment of residents’ attitudes toward sustainable tourism development—a case study of Bačko Podunavlje Biosphere Reserve, Serbia. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 35, 100384. doi:10.1016/j.jort.2021.100384

Olaniyan, O. M., Egunjobi, F. B., and Adegoke, A. (2024). African traditional arts and ornamentation in the architecture of the cultural centre ibadan. Environ. Technol. Sci. J. 14, 9–15. doi:10.4314/etsj.v14i2.2

Olaniyi, M. M., Ismail, A. I., and Aderinola, O. F. (2020). Synthesis of modern construction methods and local building materials: a drive to revive Yoruba vernacular architecture. Int. J. Afr. Asian Stud. doi:10.7176/JAAS/65-04

Olojede, H. T. (2012). Yorùbá notion of the environment. ResearchGate. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384668915_Yoruba_Notion_of_the_Environment (Accessed July 31, 2025).

Opoko, A., Adeokun, C., and Oluwatayo, A. (2016). Art in traditional African domestic architecture: its place in modern housing and implications for the training of architects. New Trends Issues Proc. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2, 675–678. doi:10.18844/prosoc.v2i1.1010

Rajpu, Y., and Tiwari, S. (2020). Neo- vernacular architecture: a paradigm shift. Palarch’s J. Archaeol Egypt/Egyptology 17 (9). Available online at: https://archives.palarch.nl/index.php/jae/article/view/5523.

Ralph Appelbaum Associates (n.d.). John Randle Centre for Yoruba culture & history. Ralph Appelbaum associates. Available online at: https://raai.com/project/john-randle-centre-for-yoruba-culture-history/ (Accessed December 21, 2024).

Reinfeld, M. A. (2003). Tourism and the politics of cultural preservation: a case study of Bhutan. J. Public Int. Aff. 14, 125–143.

Ridwan, O., and Eze, C. J. (2023). Incorporation of traditional Yoruba architecture in the design of a contemporary art gallery in Abeokuta, Ogun State. J. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Des. Available online at: https://hummingbirdjournals.com/jaeed/article/view/76 (Accessed December 15, 2024).

Sholanke, A. B., and Oyeyipo, F. J. (2023). Appraisal of lighting strategies for achieving environmental sustainability in selected art museums and galleries in Nigeria. Civ. Eng. Archit. 11 (6), 3811–3825. doi:10.13189/cea.2023.110641

Singh, A. (2023). SI.SA reimagines museum design to highlight Yoruba culture and heritage. Available online at: https://www.stirworld.com/see-features-si-sa-reimagines-museum-design-to-highlight-yoruba-culture-and-heritage (Accessed December 21, 2024).

Somaratna, S. D., Peiris, C. N., and Jayasundara, C. (2010). User expectation verses user perception of service quality in University libraries: a case study.

Terra kulture (n.d.). About Terra kulture arts and studios limited. Terra Kult. Available online at: https://terrakulture.com/about-us/ (Accessed January 13, 2025).

Tiwari, S., and Vij, M. (2024). Adaption of neo-vernacular architecture in contemporary temples in India: insights from selected case studies. Int. Soc. Study Vernac. Settlements 11 (8), 1–23. doi:10.61275/ISVSej-2024-11-08-01