- 1 University of the Free State, Disaster Management Training and Education Centre for Africa (UFS-DiMTEC), Bloemfontein, South Africa

- 2 Human Science Research Council (HSRC), Pretoria, South Africa

Introduction: Informal settlements in South Africa remain highly exposed to disasters despite continued disaster risk reduction (DRR) interventions. Khayelitsha—particularly the Barney Molokwane (BM) Section—is among Cape Town’s most flood- and fire-prone areas. Understanding vulnerability in such contexts requires frameworks capable of unpacking the interaction of exposure, susceptibility, and resilience. This study applies the Methods for the Improvement of Vulnerability Assessment in Europe (MOVE) framework to assess the drivers of vulnerability in BM Section and situates findings within comparable evidence from Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Methods: A mixed-methods design was employed, integrating household surveys with 125 randomly selected residents, transect walks, and systematic field observations. The MOVE framework structured the assessment across three components—exposure, susceptibility, and resilience. Quantitative and qualitative data were triangulated to capture settlement conditions, socio-economic factors, governance interactions, and everyday coping strategies.

Results: Vulnerability in BM Section is shaped by intersecting socio-economic, environmental, and institutional factors. Key drivers include inadequate housing, overcrowding, unemployment, poor sanitation, and infrastructure deficits. Exposure is intensified by wetland encroachment and the dismantling of protective berms. Hazardous coping practices—such as illegal electricity connections and resistance to re-blocking—reflect governance shortcomings, mistrust, and limited access to basic services rather than community unwillingness. Comparative literature shows that while wetland encroachment is context-specific, poverty and weak institutional engagement are widespread determinants of urban informal settlement vulnerability.

Discussion: The MOVE framework effectively illuminates multidimensional vulnerability but captures cultural factors and informal social safety nets less comprehensively. Findings point to the need for participatory governance approaches, including co-developed early warning systems, community-driven drainage solutions, and livelihood support mechanisms. The study demonstrates the value of structured vulnerability assessment for informing flood-risk management and climate adaptation planning in informal settlements, contributing to progress toward SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities.

1 Introduction

Informal settlements are among the most disaster-prone urban environments globally, particularly in rapidly urbanising regions of the Global South. Over one billion people now reside in such unregulated and underserved areas (Habitat for Humanity, 2025), where vulnerability emerges from the intersection of environmental exposure, socio-economic marginalisation, and governance failures (Satterthwaite et al., 2020; Dodman and Satterthwaite, 2019). Typically located on marginal land, such as wetlands and floodplains, these communities face recurring risks including flooding, fires, and disease outbreaks (Rampaul and Magidimisha-Chipungu, 2022; Archer et al., 2020). The intensification of climate-related extreme events further compounds these vulnerabilities (IPCC, 2022).

South Africa exemplifies these dynamics, with more than five million people living in informal settlements (Statistics South Africa, 2022). In Cape Town, housing shortages, high land prices, and exclusionary housing markets have entrenched urban informality (Turok et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated informal occupation through evictions and unemployment (Cirolia and Harber, 2022). Khayelitsha, one of the largest townships in the country, illustrates these challenges vividly. In the Barney Molokwane (BM) Section alone, an estimated 24,000 residents live in over 6,000 shacks (ISM, 2022). Despite the municipality’s disaster risk reduction (DRR) initiatives such as early warning systems, re-blocking projects, and flood berm construction recurring fires, floods, and sanitation-related health risks persist (Atkinson, 2024).

Recent studies suggest that top-down DRR interventions in Cape Town often encounter resistance, arising from mistrust, limited consultation, and failure to address deeper socio-economic inequalities (Bhanye J., 2025). For example, some residents dismantled flood berms for personal use, inadvertently heightening their flood risk, while re-blocking was resisted due to perceived exclusion from planning processes. Risky practices such as illegal electricity connections and waste dumping are not simply behavioural non-compliance but reflect structural neglect, limited service delivery, and precarious livelihoods (Andreasen et al., 2023; Peck et al., 2022).

While vulnerability in South African informal settlements has been widely acknowledged (Pelling et al., 2021; Archer et al., 2020), most studies focus narrowly on hazards or infrastructure deficits, with limited integration of multi-dimensional frameworks that capture exposure, susceptibility, and resilience holistically. Furthermore, little empirical work applies and critically adapts comprehensive vulnerability models, such as the MOVE framework, to informal settlement contexts in the Global South.

This study addresses this gap by applying the MOVE framework to the BM Section of Khayelitsha. Specifically, it investigates.

1. How exposure, susceptibility, and resilience interact to shape disaster vulnerability;

2. Why vulnerability persists despite targeted DRR interventions, and

3. How the MOVE framework can be adapted to highlight the socio-political and behavioural dimensions of risk in informal settlements.

When situating vulnerability analysis within a well-established but underutilised conceptual model, the study advances theoretical and empirical debates on disaster risk in South African informal settlements and contributes to the refinement of vulnerability assessment tools in Global South contexts.

2 Conceptual framework

The Methods for the Improvement of Vulnerability Assessment in Europe (MOVE) framework provides the conceptual foundation for this study. Originally developed for European hazard contexts, MOVE advances a multi-dimensional understanding of vulnerability, encompassing exposure, susceptibility, and resilience (Birkmann, 2013). Its interdisciplinary orientation allows for integration of social, economic, physical, institutional, and cultural indicators, making it adaptable to diverse contexts (Birkmann, 2013; Williams, and Webb, 2021).

In this study, MOVE is adapted to the South African informal settlement context in three ways:

Exposure is conceptualised as the physical proximity of residents and assets to hazards, assessed through settlement density, housing materials, and location in flood-prone wetlands (Andreasen et al., 2023).

Susceptibility is expanded to capture socio-economic precarity and infrastructural neglect, including unemployment, sanitation deficits, and service delivery gaps, which amplify residents’ inability to cope with hazards (Satterthwaite et al., 2020).

Resilience is reframed beyond household coping capacities to include institutional trust, participatory governance, and the role of community-driven practices in shaping adaptive strategies (Hussainzad, and Gou, 2024; Archer et al., 2020).

This contextual adaptation allows MOVE to interrogate not only material conditions but also governance dynamics and community responses, such as resistance to re-blocking and the dismantling of flood berms. These behaviours, often labelled “risky,” are reconceptualised here as embedded in deeper histories of inequality, exclusion, and contested governance (Bhanye S., 2025).

When aligning MOVE with localised indicators, including fire incidents, waste disposal practices, and institutional engagement, this study demonstrates its applicability in informal settlements. It highlights how disaster risk emerges not only from environmental hazards but from socially produced vulnerabilities linked to systemic neglect. This adaptation strengthens the analytical scope of the MOVE framework, positioning it as a valuable tool for advancing risk governance and climate adaptation in the Global South.

Figure 1 illustrates how the MOVE framework was operationalised in this study. Physical hazards such as floods and fires were mapped to exposure, socio-economic factors such as poverty, housing quality, unemployment, and health were categorised under susceptibility, while institutional capacity and community awareness were aligned with resilience. These categories were not applied abstractly; rather, they structured the design of survey items, field observations, and transect walks. For instance, sanitation access and drainage conditions were assessed under susceptibility, while participation in disaster awareness campaigns was coded as resilience. This explicit mapping guided data collection, coding, and interpretation, ensuring analytical consistency and reducing overlap between categories. Thus, Figure 1 is not a descriptive illustration but a conceptual-operational bridge between the MOVE framework and context-specific vulnerability drivers in the BM Section.

Figure 1. A Conceptual MOVE Framework for Disaster Vulnerability in the BM Section of Khayelitsha (Source: Authors own).

This system was developed for a European socio-economic governance system, which differs from an African informal settlement, poverty-stricken, and weakly governed system. It does not fully reflect livelihood-based vulnerabilities like a lack of land tenure. The framework is limited in its consideration of colonial governance impacts and political drivers.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study area

Khayelitsha, one of South Africa’s largest townships, is located on the Cape Flats in Cape Town. It was established in 1985 as a result of forced removals during the apartheid era, originally intended to house displaced Black South Africans. Over the decades, Khayelitsha has rapidly grown, driven by rural-to-urban migration and an increased natural population. Today, it is home to an estimated 500,000 residents living in a mix of formal housing and informal settlements (Coughlan de Perez et al., 2018). Khayelitsha is located in the Western Cape, South Africa, with geographical coordinates of 34° 3′0″South, 18° 40′0″East, Latitude: −34.0229818181, Longitude: 18.6700498005 as illustrated in Figure 2.

The BM Section is a densely populated informal settlement adjacent to the Eerste River and a degraded wetland. It is highly susceptible to flooding, fires, and sanitation-related health hazards due to poor infrastructure, overcrowding, and limited service delivery (Fox et al., 2023). These conditions provided a critical case for investigating disaster vulnerability’s systemic and behavioural drivers.

3.2 Study design and methodology

This study adopted a qualitative, multi-method research design to assess disaster vulnerability in the Barney Molokwane (BM) Section of Khayelitsha, Cape Town. The design was selected to capture the complex interplay between exposure, susceptibility, and resilience as conceptualised in the Methods for the Improvement of Vulnerability Assessment in Europe (MOVE) framework. By combining household surveys, field observations, and transect walks, the study sought to triangulate findings across social, environmental, and institutional dimensions, ensuring analytical robustness.

The MOVE framework was operationalised to guide both data collection and analysis. Figure 1 illustrates how vulnerability drivers were categorised. Physical hazards, such as floods and fires, were mapped to exposure. Socio-economic factors, including poverty, poor housing, unemployment, and health, were aligned with susceptibility. Institutional capacity and community awareness informed the resilience dimension. This structure directly informed the development of research instruments. For example, questions on drainage and sanitation access were linked to susceptibility, while participation in disaster awareness campaigns and access to evacuation plans were categorised under resilience. In this way, the figure served not merely as a descriptive illustration but as a conceptual-operational bridge that structured both data gathering and coding.

3.2.1 Sampling strategy

From an estimated population of 24,000 residents, a random sample of 125 participants was selected. The rationale for this sample size was to achieve diversity across gender, age, and socio-economic characteristics while ensuring feasibility in a resource-constrained setting. Randomisation was conducted within demarcated settlement blocks to avoid bias and improve representativeness. This strategy aligns with established practices in informal settlement risk assessments, where balancing methodological rigour and logistical realities is critical (Van Niekerk and Annandale, 2013).

3.2.2 Data collection

Data was collected through the use of a questionnaire that comprised three complementary methods:

Household survey: Structured questionnaires captured socio-economic status, hazard experiences, coping strategies, and perceptions of institutional capacity.

Field observations: Direct observations were conducted on environmental and infrastructural conditions such as drainage, density, sanitation, and waste management.

Transect walks: Guided spatial assessments provided insight into settlement layout, hazard-prone zones, and localised adaptation practices.

In addition to these methods, the authors followed the Tsouni et al. (2025) methods to collect the samples based on (a) collaboration with public entities, (b) indirect communication with the general public through in-person handing out of questionnaires, and (c) direct communication with the general public during field visits and by loose-format interviews about their experiences. The multi-method design enabled the cross-validation of findings, thereby enhancing the study’s credibility and depth, consistent with disaster risk research in South African informal settlements.

3.2.3 Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of the Free State Research Ethics Committee (Ref: UFS-HSD2023/1556). The study paid particular attention to the sensitivities of working with vulnerable populations. Informed consent was obtained verbally and in writing, in participants’ preferred language. A trained translator supported inclusivity and comprehension during fieldwork. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured by assigning unique codes to participants. Researchers avoided intrusive questioning on sensitive topics such as income or health, mitigating risks of discomfort. These measures strengthened the ethical integrity of the study and safeguarded community trust.

3.2.4 Analytical framework

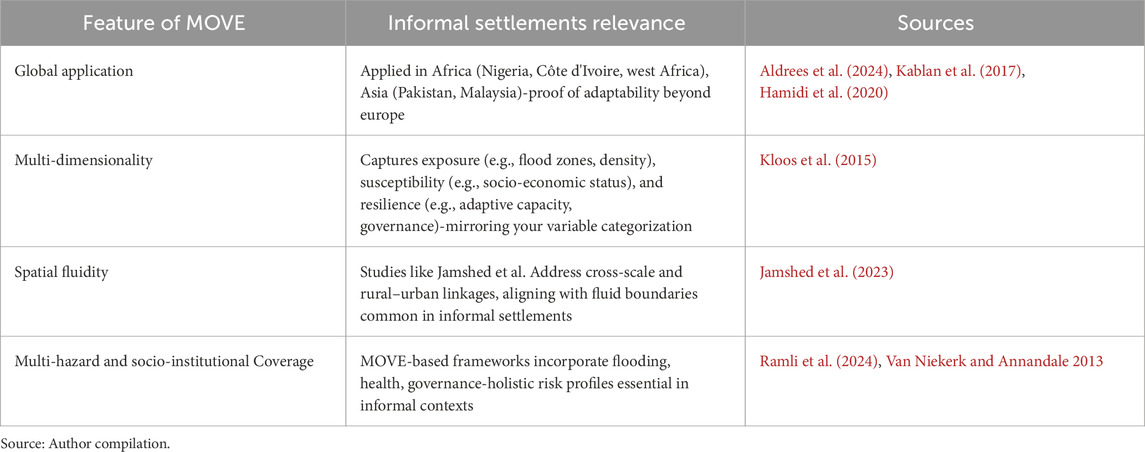

The MOVE framework’s adaptability and multidimensionality provided the foundation for analysis. Table 1 demonstrates its relevance for informal settlement contexts in the Global South. The framework’s ability to integrate exposure, susceptibility, and resilience across physical, socio-economic, and institutional dimensions mirrors the heterogeneous vulnerabilities of the BM Section. For instance, sanitation and waste disposal were analysed under susceptibility, while risk awareness and community participation were coded under resilience. This systematic categorisation ensured analytical rigour and comparability with similar studies in Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Pakistan, Malaysia, and South Africa (Kablan et al., 2017; Aldrees et al., 2024).

Table 1. MOVE framework suitability for assessing vulnerability in informal settlements (Global South).

4 Results and discussion

This section presents and interprets the study’s findings using the MOVE (Methods for the Improvement of Vulnerability Assessment in Europe) framework, emphasising the interconnection between exposure, susceptibility, and resilience. The study applies this lens to understand how community behaviours, structural vulnerabilities, and disaster risk reduction (DRR) interventions intersect in the BM Section of Khayelitsha.

4.1 Exposure: physical proximity to hazards and environmental conditions

The BM Section faces extreme environmental challenges due to its proximity to wetlands and the Eerste River. Communities adjacent to these areas experience heightened flood risks, particularly as wetland loss and encroachment from settlement expansion leave them vulnerable (Gulbin et al., 2019). This is also supported by Wang et al. (2023), who argue that an increasing number of people are relocating away from flood-affected areas, such as those in the Middle East. However, this is not the case in African countries, as poverty and proximity to economic benefits increase, people are impelled to reside in flood-prone areas illegally. Such a situation contributes to exposure to the hazard. During the rainy season, flooding becomes a frequent issue. The study findings highlighted that 50% of respondents are regularly exposed to flooding. This vulnerability can be attributed to the inadequate drainage infrastructure common in rapidly expanding informal settlements, where dense urbanisation exacerbates the risk and impact of flood events, as highlighted in previous studies by Ramadan et al. (2025) and Dube et al. (2022). Furthermore, the high density observed in these settlements, combined with the use of flammable materials such as wood and tin, increases fire hazards, with informal settlements in South Africa recording a disproportionately high occurrence of shack fires due to open flames, unsafe electrical connections, and combustible construction materials (Walls et al., 2020; Walls et al., 2019). The study findings reveal that 42% of respondents had experienced fire incidents directly or indirectly, aligning with national statistics that indicate an average of 10 shack fires per day and approximately 4,000 annual fire incidents in these vulnerable communities (IFRC-DREF, 2025). Through observations, the study found dense arrangements of dwellings coupled with limited accessibility for emergency services, and the absence of early warning systems contribute to the rapid spread and devastating impact of such fires, highlighting the critical need for improved safety measures and infrastructure in these areas. This finding is corroborated by the findings of Adiba (2023), whose study in Dakar equally revealed some of these vulnerabilities experienced in South Africa.

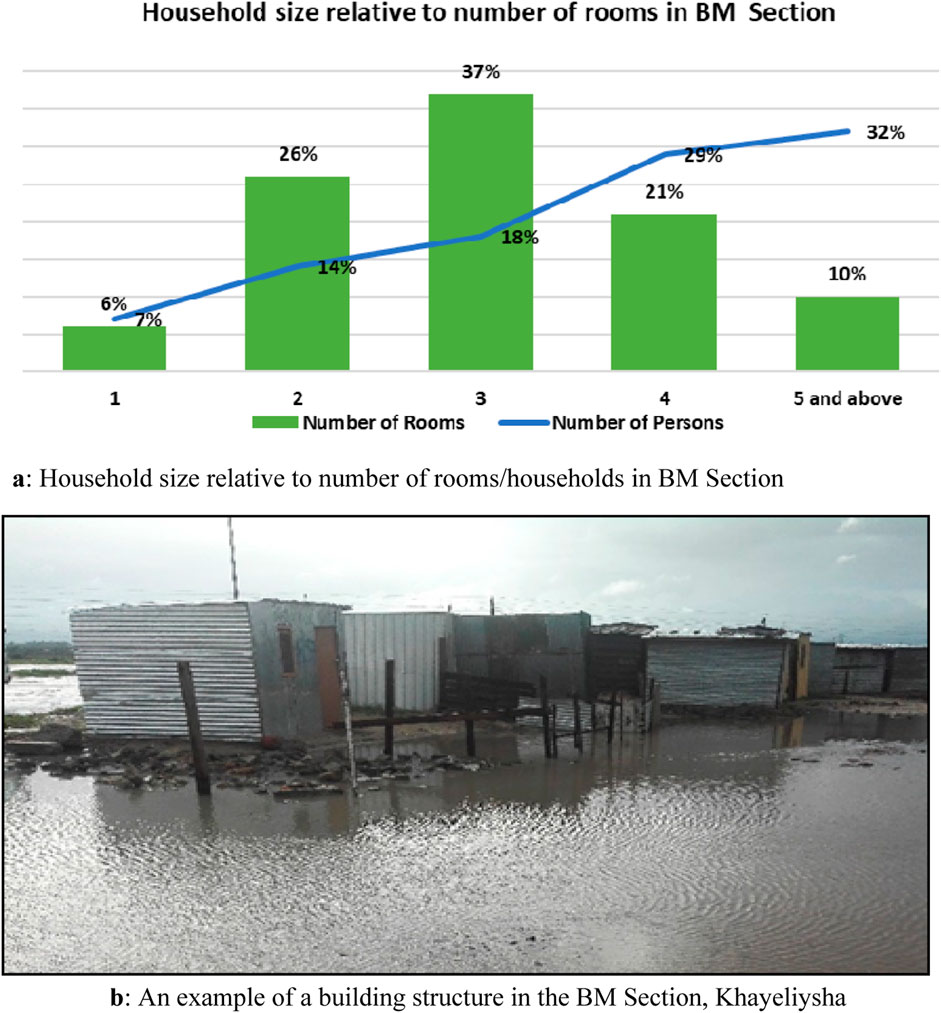

Data from the study further illustrates how overcrowding within limited living spaces exacerbates vulnerability to environmental hazards in the BM Section. As shown in Figure 3a, most households (37%) occupy dwellings with only three rooms, while a substantial portion (26%) live in two-room homes. Despite these limited room numbers, household size increases with fewer rooms, with 32% of respondents in households of five or more people. This inverse relationship between available space and household size reflects high levels of overcrowding, a known factor that intensifies exposure to disasters. In flood-prone and fire-prone environments such as Khayelitsha, overcrowded conditions limit mobility, impede emergency response access, and increase the likelihood of fire spread or flood impact. When combined with flammable construction materials and poor drainage infrastructure, these conditions create highly combustible and flood-vulnerable micro-environments (Figure 3b). Therefore, the intersection of inadequate housing, high household density and building positions/conditions significantly contributes to residents' exposure to environmental risks in informal settlements.

Figure 3. (a) Household size relative to number of rooms/households in BM Section. (b) An example of a building structure in the BM Section, Khayeliysha.

4.2 Susceptibility: socio-economic insecurity and infrastructure deficits in BM section Khyelistsha, Cape Town

The BM Section in Khayelitsha, Cape Town, is susceptible to disasters driven by intertwined socio-economic insecurity and infrastructure deficits. The study findings reveal that 54% of respondents were unemployed, while 43% of residents earn less than R2,000 per month. These finding highlights severe financial constraints that hinder investments in safer housing and disaster mitigation measures, thereby reinforcing the community’s susceptibility. Infrastructure inadequacies exacerbate vulnerability, with 94% lacking private sanitation and 62% resorting to burning or dumping waste due to the absence of formal waste management. This creates pervasive health and environmental risks, as noted in a study by Raphela and Matsididi (2025), who state that floods have a socioeconomic impact on communities, including degradation of water quality. These conditions facilitate the spread of waterborne and vector-borne diseases, consistent with the findings from studies by Weimann and Oni (2019) and Sverdlik (2011), linking poor sanitation and overcrowding in informal settlements to heightened infectious disease prevalence and compromised immune responses.

In the BM Section of Khayelitsha, 66% of the respondents depend on unsafe (illegal) electrical connections. Combined with overcrowded dwellings (Figure 3a), this significantly heightens the risk of fire and injury, illustrating a multi-dimensional risk profile typical of informal settlements. This observation aligns with findings from Antonellis et al. (2022) and Williams-Bruinders, (2019), highlighting similar safety concerns in densely populated areas. Also, studies by Petrie et al. (2019) and Nanima and Durojaye (2020) have highlighted that poor housing quality, marked by minimally insulated, insecure informal structures and the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with Cape Town’s harsh climatic conditions, led to increased crime vulnerability. This finding echoes the evidence of a study conducted by Habitat for Humanity (2025) connecting inadequate shelter to worsened physical and mental health outcomes in impoverished communities in Cape Town. These physical deficiencies are manifestations of deeper structural inequalities and governance failures, where insufficient service delivery and exclusionary urban policies perpetuate socio-spatial marginalisation and residents' entrenched vulnerability (Ndabezitha et al., 2024). These interlinked socio-economic and infrastructural factors create a landscape of chronic risk and disaster susceptibility, underscoring the urgent need for integrated, participatory, and equity-focused interventions to enhance resilience in the BM Section and similar informal settlements globally (Amegavi et al., 2025; Mugisha et al., 2025; García and Martínez-Román, 2025).

The income and employment data further underscore the socio-economic precarity contributing to disaster susceptibility in the BM Section. As illustrated in Figure 4a, 43% of respondents earn less than R2,001 per month, with only 1% reporting earnings above R10,000. This income distribution reflects widespread poverty, which limits households' capacity to invest in resilient infrastructure, secure insurance, or recover after disaster events. Similarly, Figure 4b reveals that more than half of respondents (54%) are unemployed, while an additional 22% rely on part-time work, and only 12% are employed full-time or on contracts. These employment patterns indicate unstable and insecure livelihoods, leaving many residents economically vulnerable and dependent on informal survival strategies. These conditions compound residents' susceptibility by constraining their ability to access basic services, relocate from high-risk areas, or implement individual-level risk reduction measures. These findings reinforce the need for integrated interventions that address infrastructural deficiencies and the underlying economic fragilities that perpetuate disaster vulnerability in informal settlements.

This finding, therefore, highlights that disaster vulnerability in the BM informal settlement is not solely a consequence of environmental exposure but is rooted in systemic social and political inequities that must be addressed comprehensively to reduce disaster risks effectively.

4.3 Resilience: risk awareness, behavioural dynamics, and institutional gaps

The persistent challenges in enhancing resilience within the BM Section of Khayelitsha highlight significant deficiencies in community risk awareness, behavioural dynamics, and institutional engagement, despite implementing numerous disaster risk reduction (DRR) initiatives. Research by Fox et al. (2023) and Tsebe (2020) indicates that informal settlement communities in Cape Town face considerable obstacles, primarily stemming from limited community participation and a prevailing distrust in DRR strategies. This scepticism diminishes the effectiveness of interventions aimed at mitigating disaster risks. Motsumi and Nemakonde (2024) further illustrate that institutional inadequacies, characterised by opaque communication and neglecting to integrate indigenous knowledge, perpetuate a culture of risk-prone behaviours within these communities.

The data collected for this study reveals an interesting paradox, as approximately 70% of residents acknowledge DRR strategies such as fire and flood awareness campaigns. Still, there remains a pervasive scepticism about their effectiveness. This attitude is deeply rooted in a historical context of mistrust and perceived governmental neglect. Tsebe (2020) presents a poignant example through the city’s re-blocking initiative, which sought to enhance access to services and improve emergency response in informal settlements. However, this initiative met widespread resistance, reflecting profound community fears regarding potential displacement and inadequate consultation. Such resistance underscores a significant challenge confronting top-down DRR interventions, particularly in informal settings where technical strategies falter without the support of robust participatory frameworks. This theme, echoed in the wider body of empirical research on urban informal contexts (Zuma, 2022; Kunguma, 2020), demonstrates that while awareness of DRR initiatives exists, the scepticism surrounding government-led efforts ultimately undermines community engagement and resilience.

The behaviours exhibited by community members, such as reliance on open flames for cooking and heating due to inconsistent or exorbitant electricity access, alongside unsafe electrical connections and inappropriate waste disposal practices, are not merely products of ignorance; rather, they reflect constrained choices within an environment defined by socio-economic precarity. This reality is compounded by disillusionment with externally imposed solutions (Pienaar, 2021; Kanyinji, 2015). These behavioural patterns elucidate the systemic issues that extend beyond the inadequacies of awareness campaigns, fundamentally linking risk mitigation to broader socio-economic and infrastructural deficits. These institutional shortcomings arise from a lack of consistent and transparent engagement with residents, which undermines social ownership and community agency, elements critically recognised in disaster resilience scholarship as necessary for effective DRR (Onyeagoziri, 2020; Waddell, 2016). This implies that advancing resilience in the BM Section will necessitate a paradigm shift towards community-driven, culturally responsive DRR approaches that harmonise technical, social, and political dimensions of vulnerability and capacity. This suggestion aligns with evidence from emergent literature advocating for the decolonisation of risk governance and the empowerment of grassroots initiatives as essential for transforming vulnerability into adaptive resilience (Agyemang, 2025; Pal, 2025). To foster enduring disaster risk reduction, moving beyond hegemonic, technocratic frameworks towards pluralistic governance that prioritises trust, co-production, and social cohesion is imperative.

The above findings from the BM Section of Khayelitsha highlight that disaster vulnerability cannot be understood in isolation through exposure, susceptibility, or resilience alone. Rather, these dimensions intersect to create a compounded risk environment in which physical, socio-economic, and institutional factors reinforce one another. Within the MOVE framework, vulnerability emerges as a multi-dimensional condition in which exposure to hazards, social and economic susceptibility, and low resilience collectively determine disaster outcomes. This highlights the limitations of fragmented interventions that target single drivers of risk without addressing their systemic interconnections.

For instance, the high exposure to floods and fires in the BM Section is inextricably linked to the socio-economic realities of unemployment, poverty, and inadequate infrastructure (Williams and Zacheous, 2022). Residents' reliance on unsafe energy sources or informal waste disposal methods cannot be dismissed as individual risk behaviours, they are symptomatic of broader structural deficits that heighten susceptibility and limit the adoption of safer practices. At the same time, weak resilience, characterised by mistrust in state-led initiatives and a lack of participatory governance, further amplifies exposure and susceptibility (Kunguma and Skinner, 2017). Dismantling flood berms and rejecting re-blocking plans are not isolated acts of resistance but reflect deeper social tensions between communities and institutions, underscoring the centrality of governance and trust in shaping resilience.

This interconnectedness illustrates that disaster vulnerability in the BM Section is cumulative and path-dependent. Exposure to environmental hazards is worsened by socio-economic deprivation, while both are entrenched by institutional shortcomings that curtail adaptive capacity. The MOVE framework proves valuable in capturing these dynamics by revealing how vulnerabilities are layered across physical, social, and institutional domains. Importantly, this analysis underscores the inadequacy of technocratic, top-down disaster risk reduction approaches that neglect the lived realities of residents. Therefore, building resilience in informal settlements requires integrated, community-centred strategies that acknowledge the complexity of vulnerability and move beyond narrow technical fixes toward systemic transformation.

While the results are highly specific to the BM Section, they resonate with broader patterns observed across informal settlements in the Global South. Similar vulnerabilities have been reported in West Africa, where inadequate drainage and poverty amplify flood exposure (Rentschler et al., 2022; Alves et al., 2020; Kablan et al., 2017), in South Asia, where insecure tenure and overcrowding heighten both flood and fire risks (Anwar and Sur, 2021) and in Latin America, where deficient infrastructure and social inequality shape chronic disaster vulnerability (García and Martínez-Román, 2025; Lavell et al., 2023). These underscore that poverty, unemployment, poor housing quality, and limited service delivery represent generalised drivers of vulnerability across informal settlements worldwide. At the same time, some challenges identified in Khayelitsha are more place-specific, such as the settlement’s location on degraded wetlands and the dismantling of flood berms, which reflect unique socio-ecological and governance dynamics in Cape Town. Distinguishing between universal drivers and context-specific features strengthens this case study’s contribution to comparative debates on urban informality, vulnerability, and adaptation.

It should equally be noted that while climate change is often blamed for the rising incidence of floods, understanding flood risk requires a systems lens that considers multiple, interconnected drivers (Dlamini et al., 2024). Findings from studies by Fivos Sargentis et al. (2024) and Andreadis et al. (2022) demonstrate that urban expansion into floodplains, driven by increased impervious surfaces and poor spatial planning, plays a primary role in intensifying flood hazards alongside climate-related factors. This highlights that floods are not merely natural disasters but outcomes of complex interactions between human and environmental systems. Recognising risk in all its dimensions, climatic, ecological, social, and infrastructural, is therefore essential for designing adaptive and equitable urban resilience strategies.

5 Lessons learned from the study

This study presents a case study of an informal settlement. From the BM Section case study several lessons can be learnt that can inform urban flood risk reduction in other informal settlement contexts:

First, the study highlight that community participation is essential for effective flood management. Resistance to re-blocking and the dismantling of berms illustrate that technical interventions fail when residents are excluded from decision-making. Co-production of flood mitigation strategies builds trust, ensures local relevance, and enhances long-term sustainability.

Secondly, structural vulnerabilities amplify flood risk. From poor drainage, insecure housing, and overcrowding in the BM Section, intensifying exposure to flooding. Settling building standards, upgrading basic infrastructure, particularly sanitation and drainage systems, is a prerequisite for reducing hazard impacts in flood-prone settlements.

Also, the study highlights that livelihood insecurity drives risky coping strategies. Illegal electricity connections and waste dumping are not simply acts of non-compliance but adaptive responses to poverty and exclusion. Addressing socio-economic precarity through livelihood support can reduce reliance on unsafe practices that exacerbate flood vulnerability.

While awareness campaigns exist, limited trust undermines their effectiveness. Lessons from BM Section highlight the need for culturally attuned, locally embedded early warning mechanisms that are credible to residents and linked to actionable evacuation options. Also, weak institutional engagement and mistrust were central to low resilience in BM Section. Building transparent, inclusive governance structures is critical for scaling up flood preparedness and adaptation in informal settlements worldwide.

These lessons underline that urban flood risk reduction in informal settlements cannot be achieved through infrastructure investment alone but requires integrated approaches that link technical measures with social equity, livelihood security, and participatory governance.

6 Study limitations, conclusion and recommendations

6.1 Study limitations

Although the study contributes to existing literature, several limitations to the study must be acknowledged. First, while the sample of 125 respondents provided sufficient diversity to capture key patterns of vulnerability in BM Section, the relatively small size limits the generalisability of the findings to Khayelitsha as a whole. The results should therefore be interpreted as illustrative of systemic drivers of vulnerability rather than statistically representative of all informal settlements in Cape Town.

A further limitation lies in the absence of detailed spatial visualization, such as flood hazard or risk maps and satellite imagery, to illustrate settlement proximity to floodplains. Due to data and resource constraints, generating or sourcing such spatial data was not feasible within the current scope. Future research could incorporate these elements to strengthen the spatial context and visual representation of flood risk in informal settlements.

Although the MOVE framework proved valuable in structuring the analysis of exposure, susceptibility, and resilience, its application also revealed certain limitations in capturing context-specific dimensions of vulnerability. The model was unable to capture cultural factors, such as norms around collective coping, and informal safety nets, such as savings groups, kinship networks, and community-led emergency responses, were not easily accommodated within the framework’s categories. These elements are often equally important to how households navigate risk in informal settlements but were only indirectly observed in this study.

Finally, the study’s focus on one settlement, (the BM Section), emphasises place-based dynamics, such as wetland encroachment and resistance to re-blocking, which may not apply uniformly to other urban contexts. Notwithstanding, the study highlights and offer insights that remain relevant beyond the local case.

6.2 Conclusion and recommendations

This study applied the MOVE framework to examine disaster vulnerability in the BM Section of Khayelitsha and found that risk is multi-dimensional, shaped not only by physical exposure to floods and fires but also by socio-economic precarity, infrastructural deficits, and weak institutional engagement. Vulnerability persists because interventions remain fragmented and technocratic, overlooking the cumulative interplay between exposure, susceptibility, and resilience. The dismantling of berms, rejection of re-blocking, and persistence of risky practices are not simply behavioural failings but reflections of constrained choices and entrenched mistrust in government processes. Disaster vulnerability in Khayelitsha is therefore less temporary than a structural reality embedded in urban inequality and exclusion. Addressing this challenge requires integrated and participatory approaches that move beyond technical fixes. Resilience can only be strengthened through transparent governance, inclusive settlement upgrading, and livelihood support that reduces reliance on unsafe coping strategies. Risk communication must evolve into sustained, two-way engagement that values local knowledge and fosters community ownership of DRR initiatives. Finally, aligning municipal and national policies is critical to prioritise informal settlements in resilience planning with adequate resources and accountability mechanisms. Recognising vulnerability as systemic and cumulative, this study underscores the need for community-centred, equity-driven interventions that can transform informal settlements from sites of chronic disaster risk into spaces of adaptive resilience.

Beyond contributing to vulnerability theory, the findings of this study hold practical implications for urban flood risk management. The identification of inadequate drainage and settlement encroachment on wetlands highlights the urgency of investing in low-cost, community-maintained drainage improvements that are co-designed with residents to ensure uptake and sustainability. Similarly, evidence of weak trust in municipal initiatives underscores the importance of participatory early warning systems that are co-produced with communities, communicated in local languages, and linked to feasible evacuation options. The persistence of hazardous coping strategies, such as illegal electrical connections, further demonstrates that structural interventions must be paired with livelihood support and social safety nets to reduce reliance on unsafe practices. By translating vulnerability analysis into actionable priorities for early warning, drainage upgrading, and community-based adaptation, this study illustrates how informal settlement case studies can inform flood preparedness and mitigation strategies in comparable contexts globally.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of the free state ethics committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

OK: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. LA: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review and editing. IP: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. WL: Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adiba, M. A. (2023). Cause of repetitive fire disaster in informal settlements and the importance of community based disaster risk mitigation doctoral dissertation. Dhaka, Bangladesh: BRAC University.

Agyemang, F. (2025). Legal and policy perspectives on public participation and disaster risk management in South African cities. J. Local Gov. Res. Innovation 6, a259. doi:10.4102/jolgri.v6i0.259

Aldrees, A., Mohammed, A., Dan’azumi, S., and Abba, S. I. (2024). Frequency-based flood risk assessment and mapping of a densely populated Kano city in Sub-Saharan Africa using MOVE framework. Water 16 (7), 1013. doi:10.3390/w16071013

Alves, B., Angnuureng, D. B., Morand, P., and Almar, R. (2020). A review on coastal erosion and flooding risks and best management practices in West Africa: what has been done and should be done. J. Coast. Conservation 24 (3), 38. doi:10.1007/s11852-020-00755-7

Amegavi, G. B., Nursey-Bray, M., and Suh, J. (2025). Advancing social equity in urban resilience planning: challenges and opportunities. J. Environ. Plan. Manag., 1–21. doi:10.1080/09640568.2025.2463558

Andreadis, K. M., Wing, O. E., Colven, E., Gleason, C. J., Bates, P. D., and Brown, C. M. (2022). Urbanizing the floodplain: global changes of imperviousness in flood-prone areas. Environ. Res. Lett. 17 (10), 104024. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac9197

Andreasen, M. H., Agergaard, J., Allotey, A. N. M., Møller-Jensen, L., and Oteng-Ababio, M. (2023). Built-in flood risk: the intertwinement of flood risk and unregulated urban expansion in African cities. Urban Forum 34, 385–411. doi:10.1007/s12132-022-09478-4

Antonellis, D., Hirst, L., Twigg, J., Vaiciulyte, S., Faisal, R., and Spiegel, M. (2022). “A comparative study of fire risk emergence in informal settlements in Dhaka and cape town,”. London: Royal Academy of Engineering.

Anwar, N., and Sur, M. (2021). Climate change, urban futures, and the gendering of cities in south Asia.

Archer, D., Satterthwaite, D., Colenbrander, S., Dodman, D., Hardoy, J., Mitlin, D., et al. (2020). Building resilience to climate change in informal settlements. One Earth 2 (2), 143–156. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.202.02.002

Atkinson, C. L. (2024). Informal settlements: a new understanding for governance and vulnerability study. Urban Sci. 8 (4), 158. doi:10.3390/urbansci8040158

Bhanye, J. (2025a). A review study on community-based flood adaptation in informal settlements in the global south. Discov. Sustain. 6 (1), 595. doi:10.1007/s43621-025-01449-6

Bhanye, S. (2025b). Adapting from below: flooding, informality, and the power of community resilience. Available online at: https://communities.springernature.com/posts/adapting-from-below-flooding-informality-and-the-power-of-community-resilience.

J. Birkmann (2013). Measuring vulnerability to natural hazards: towards disaster resilient societies. 2nd edn. (Tokyo: United Nations University Press).

Coughlan de Perez, E., van Aalst, M., Bischiniotis, K., Mason, S., Nissan, H., Pappenberger, F., et al. (2018). Global predictability of temperature extremes. Environ. Res. Lett. 13 (5), 054017. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aab94a

Cirolia, L. R., and Harber, J. (2022). Urban statecraft: the governance of transport infrastructures in African cities. Urban Stud. 59 (12), 2431–2450. doi:10.1177/00420980211028106

Dlamini, S., Nhleko, B., and Ubisi, N. (2024). Understanding socioeconomic risk and vulnerability to climate change-induced disasters: the case of informal settlements in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J. Asian Afr. Stud., 00219096241275398. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11910/23676 (Accessed November 26, 2025).

Dodman, D., and Satterthwaite, D. (2019). Responding to climate change in contexts of urban poverty. Environ. and Urbanization 31 (1), 3–10. doi:10.1177/0956247819830004

Dube, K., Nhamo, G., and Chikodzi, D. (2022). Flooding trends and their impacts on coastal communities of Western Cape province, South Africa. GeoJournal 87 (Suppl. 4), 453–468. doi:10.1007/s10708-021-10460-z

Fivos Sargentis, G., Ioannidis, R., Kougkia, M., Benekos, I., Iliopoulou, T., Dimitriadis, P., et al. (2024). Do floods attack cities or cities invade flood plains? Case study: athens, Greece. Int. Conf. Eng. Appl. Sci. Optim., 216–224. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-92044-8_21

Fox, A., Ziervogel, G., and Scheba, S. (2023). Strengthening community-based adaptation for urban transformation: managing flood risk in informal settlements in cape town. Local Environ. 28 (7), 837–851. doi:10.1080/13549839.2021.1923000

García, I., and Martínez-Román, L. (2025). Participatory land planning, community land trusts, and managed retreat: transforming informality and building resilience to flood risk in Puerto Rico’s Caño martín peña. Land 14 (3), 485. doi:10.3390/land14030485

Gulbin, S., Kirilenko, A. P., Kharel, G., and Zhang, X. (2019). Wetland loss impact on long term flood risks in a closed watershed. Environ. Science and Policy 94, 112–122. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2018.12.032

Habitat for Humanity (2025). The effects of housing poverty in South Africa. Atlanta, Georgia, USA: United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Available online at: https://habitat.org.za/effects-housing-poverty-south-africa/ (Accessed July 07, 2025).

Hamidi, A. R., Wang, J., Guo, S., and Zeng, Z. (2020). Flood vulnerability assessment using MOVE framework: a case study of the northern part of district Peshawar, Pakistan. Natural hazards 101 (2), 385–408.

Hussainzad, E. A., and Gou, Z. (2024). Climate risk and vulnerability assessment in informal settlements of the Global South: a critical review. Land 13 (9), 1357. doi:10.3390/land13091357

IFRC-DREF Final Report (2025). South africa_fire. Available online at: https:///C:/Users/lumso/Downloads/South%20Africa%20-%20Fire%20-%20DREF%20Final%20Report%20(MDRZA014).pdf (Accessed July 08, 2025).

IPCC (2022). in Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental Panel on climate change. (Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press), 3056. doi:10.1017/9781009325844

Jamshed, A., Rana, I. A., Birkmann, J., McMillan, J. M., and Kienberger, S. (2023). A bibliometric and systematic review of the methods for the improvement of vulnerability assessment in europe framework: a guide for the development of further multi-hazard holistic framework. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 15 (1), 1–11.

Kablan, M. K. A., Dongo, K., and Coulibaly, M. (2017). Assessment of social vulnerability to flood in urban Côte d’ivoire using the MOVE framework. Water 9 (4), 292. doi:10.3390/w9040292

Kloos, J., Asare-Kyei, D., Pardoe, J., and Renaud, F. G. (2015). Towards the development of an adapted multi-hazard risk assessment framework for the West Sudanian savanna zone.

Kunguma, O. (2020). South African disaster management framework: assessing the status and dynamics of establishing information management and communication systems in provinces. Bloemfontein, 1–289. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.10978.86728

Kunguma, O., and Skinner, J. (2017). Mainstreaming media into disaster risk reduction and management, South Africa. Disaster Adv. 10 (7), 1–11. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318272639_Mainstreaming_media_into_disaster_risk_reduction_and_management_South_Africa (Accessed November 26, 2025).

Lavell, A., Chávez Eslava, A., Barros Salas, C., and Miranda Sandoval, D. (2023). Inequality and the social construction of urban disaster risk in multi-hazard contexts: the case of Lima, Peru and the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Urbanization 35 (1), 131–155. doi:10.1177/09562478221149883

Motsumi, M. M., and Nemakonde, L. D. (2024). A framework to integrate indigenous knowledge into disaster risk reduction to build disaster resilience: insights from rural South Africa. Disaster Prev. Manag. An Int. J. 33 (6), 73–85. doi:10.1108/dpm-08-2024-0220

Mugisha, J., Uwayezu, E., Babere, N. J., and Kombe, W. J. (2025). Fostering neighbourhood social–ecological resilience through land readjustment in rapidly urbanising cities in Sub-Saharan Africa: the case of Nunga in Kigali, Rwanda. Urban Sci. 9 (5), 171. doi:10.3390/urbansci9050171

Nanima, R., and Durojaye, E. (2020). The socio-economic rights impact of COVID-19 in selected informal settlements in Cape Town.

Ndabezitha, K. E., Mubangizi, B. C., and John, S. F. (2024). Adaptive capacity to reduce disaster risks in informal settlements. Jàmbá-Journal Disaster Risk Stud. 16 (1), 1488. doi:10.4102/jamba.v16i1.1488

Onyeagoziri, O. J. (2020). Resilience in disasters: a case study of an informal settlement in the Western Cape of South Africa.

Pal, S. (2025). Rethinking resilience and vulnerability in adaptation studies. Südasien-Chronik-South Asia Chron. 14, 251–276. doi:10.18452/31523

Peck, A. J., Adams, S. L., Armstrong, A., Bartlett, A. K., Bortman, M. L., Branco, A. B., et al. (2022). A new framework for flood adaptation: introducing the flood adaptation hierarchy. Ecol. Soc. 27 (4), 5–15. doi:10.5751/ES-13544-270405

Pelling, M., Chow, W. T. L., Chu, E., Dawson, R., Dodman, D., Fraser, A., et al. (2021). A climate resilience research renewal agenda: learning lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for urban climate resilience. Climate and Development 14 (7), 617–624. doi:10.1080/17565529.2021.1956411

Petrie, B., Rawlins, J., Engelbrecht, F., and Davies, R. (2019). Vulnerability and hazard assessment report. Elaboration of a Climate Change Hazard, Vulnerability and Risk Assessment Study to the benefit of the City of Cape Town. One World Sustainable Investments. Cape Town.

Pienaar, J. C. V. (2021). Assessing emergency response mechanisms to informal settlement fires in Cape Town.

Ramadan, M. S., Almurshidi, A. H., Razali, S. F. M., Ramadan, E., Tariq, A., Bridi, R. M., et al. (2025). Spatial decision-making for urban flood vulnerability: a geomatics approach applied to Al-Ain City, UAE. Urban Clim. 59, 102297. doi:10.1016/j.uclim.2025.102297

Ramli, M.W.A., Alias, N.E., Mohd Yusof, H., Abdul Wahab, Y.F., Sa'adi, Z., and Abd Rahman, A. (2024). Multi-hazard, multidimensional disaster risk validation in selangor's three urban districts, Malaysia. Geomatics, natural hazards and risk 15 (1), 2413683.

Rampaul, K., and Magidimisha-Chipungu, H. (2022). Gender mainstreaming in the urban space to promote inclusive cities. J. Transdiscipl. Res. S. Afr. 18 (01), 1–9. doi:10.4102/td.v18i1.1163

Raphela, T. D., and Matsididi, M. (2025). The causes and impacts of flood risks in South Africa. Front. Water Hum. Syst. 6, 1524533. doi:10.3389/frwa.2024.1524533

Rentschler, J., Salhab, M., and Jafino, B. A. (2022). Flood exposure and poverty in 188 countries. Nat. Communications 13 (1), 3527. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-30727-4

Satterthwaite, D., Archer, D., Colenbrander, S., Dodman, D., Hardoy, J., Mitlin, D., et al. (2020). Building resilience to climate change in informal settlements. One Earth 2 (2), 143–156. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2020.02.002

Statistics South Africa (2022). Census 2022: census of population and housing. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. Available online at: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=16716.

Sverdlik, A. (2011). Ill-health and poverty: a literature review on health in informal settlements. Environ. Urbanisation 23 (1), 123–155. doi:10.1177/0956247811398604

Tsebe, E. S. M. (2020). “Re-blocking informal settlements: investigating the hazard and risk reduction strategy for Langaville,” in City of Ekurhuleni, South Africa (Masters dissertation, University of the Free State).

Tsouni, A., Sigourou, S., Pagana, V., Tsoutsos, M. C., Dimitriadis, P., Sargentis, G. F., et al. (2025). Multiparameter flood risk assessment and management planning at high spatial resolution in the Region of Attica, Greece. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observation Remote Sens. 18, 25966–25979. doi:10.1109/jstars.2025.3613569

Turok, I., Scheba, A., and Visagie, J. (2020). Social housing and spatial inequality in South African cities. UE-AFD Research Facility on Inequalities Policy Brief, July. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11910/15670.

Van Niekerk, D., and Annandale, E. (2013). Utilising participatory research techniques for community-based disaster risk assessment. Int. J. Mass Emergencies and Disasters 31 (2), 160–177. doi:10.1177/028072701303100203

Waddell, J. (2016). A nodal governance approach to understanding the barriers and opportunities for disaster governance: a case study on flood governance in an informal settlement in Cape Town, South Africa.

Walls, R. S., Eksteen, R., Kahanji, C., and Cicione, A. (2019). Appraisal of fire safety interventions and strategies for informal settlements in South Africa. Disaster Prev. Manag. An Int. J. 28 (3), 343–358. doi:10.1108/dpm-10-2018-0350

Walls, R., Cicione, A., Pharoah, R., Zweig, P., Smith, M., and Antonellis, D. (2020). Fire safety engineering guideline for informal settlements: towards practical solutions for a complex problem in South Africa. Pretoria: UE-AFD Research Facility on Inequalities/Human Sciences Research Council.

Wang, N., Sun, F., Koutsoyiannis, D., Iliopoulou, T., Wang, T., Wang, H., et al. (2023). How can changes in the human-flood distance mitigate flood fatalities and displacements? Geogr. Res. Lett. 50 (20), e2023GL105064. doi:10.1029/2023gl105064

Weimann, A., and Oni, T. (2019). A systematised review of the health impact of urban informal settlements and implications for upgrading interventions in South Africa, a rapidly urbanising middle-income country. Int. Journal Environmental Research Public Health 16 (19), 3608. doi:10.3390/ijerph16193608

Williams, B. D., and Webb, G. R. (2021). Social vulnerability and disaster: understanding the perspectives of practitioners. Disasters 45 (2), 278–295. doi:10.1111/disa.12422

Williams, J. J., and Zacheous, A. A. (2022). An evaluation of urbanisation challenges experienced in the Low-Income Areas of Khayelitsha. Cape Town, South Africa.

Williams-Bruinders, L. E. I. Z. E. L. (2019). The social sustainability of low-cost housing: the role of social capital and sense of place. Gqeberha: Nelson Mandela University.

Keywords: disaster risk reduction, informal settlements, MOVE framework, disaster vulnerability, community resilience

Citation: Kunguma O, Awah LS, Petersen I and Lunga W (2025) Assessing disaster vulnerability in an informal settlement of Cape Town, South Africa, through the MOVE framework. Front. Built Environ. 11:1693836. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2025.1693836

Received: 27 August 2025; Accepted: 18 November 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

G.-Fivos Sargentis, National Technical University of Athens, GreeceReviewed by:

Theano Iliopoulou, National Technical University of Athens, GreecePanayiotis Dimitriadis, National Technical University of Athens, Greece

Juliet Akola, Mangosuthu University of Technology, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Kunguma, Awah, Petersen and Lunga. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olivia Kunguma, a3VuZ3VtYW9AdWZzLmFjLnph

Olivia Kunguma

Olivia Kunguma Lum Sonita Awah

Lum Sonita Awah Ilona Petersen

Ilona Petersen Wilfred Lunga

Wilfred Lunga