- 1University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, United States

- 2The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States

Introduction: Supply Chain Visibility (SCV) is increasingly recognized as a critical enabler of effective material delivery, coordination, and risk management in industrial construction. However, the specific benefits of SCV and how they are perceived across stakeholder groups remain underexamined. This study provides an evaluation of SCV benefits from the perspective of owners, contractors, designers, and suppliers engaged in industrial construction projects.

Methods: Thirteen SCV benefits were identified through a detailed literature review and refined using structured expert workshops. These benefits were then evaluated through an industry survey (n = 165). The analysis used Relative Importance Index (RII) to rank the benefits, Kruskal–Wallis tests to assess between-group differences, and Percentage Agreement and Kendall’s tau rank correlation coefficient for the rank agreement analysis.

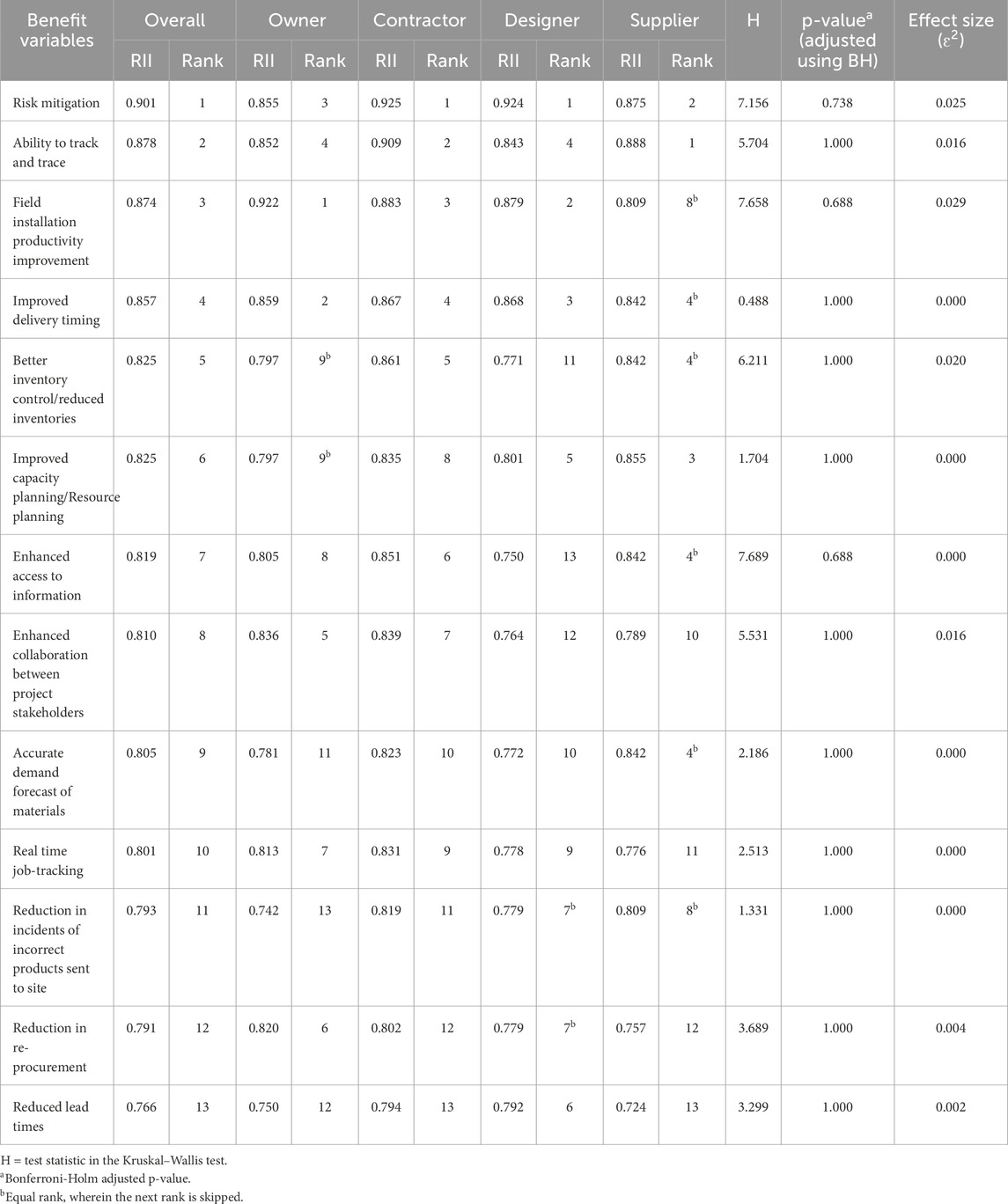

Results: The results reveal broad agreement on the top SCV benefits, including risk mitigation, ability to track and trace materials, field installation productivity improvement, and improved delivery timing. Notably, traditionally emphasized benefits like lead time reduction were ranked lower, suggesting unique visibility needs in construction compared to other industries. Kruskal–Wallis tests found no median differences between the four groups (all p > 0.05). The percentage agreement patterns and the Kendall’s tau rank correlation coefficient results indicate that contractors play a central role in aligning upstream and downstream visibility needs (Owner–Contractor, PA = 64.63%, τ-b = 0.555, adjusted p-value <0.05; Contractor–Supplier, PA = 65.47%, τ-b = 0.578, adjusted p-value <0.05).

Discussion: The benefit rankings offer construction professionals a benchmark for prioritizing and communicating SCV initiatives. The results also inform more targeted visibility strategies tailored to the roles and priorities of different stakeholder groups. This study is among the first to define and assess SCV benefits across multiple construction stakeholder groups. It contributes to theory and practice by offering a stakeholder-informed foundation for evaluating SCV in industrial construction.

1 Introduction

Supply chain visibility (SCV), commonly defined as the ability to track and monitor materials and related information across the supply chain, is widely recognized as a fundamental requirement for effective supply chain management (Goh et al., 2009). SCV is a well-established concept in the broader business and operations management literature and has been extensively studied in the contexts of manufacturing, logistics, and general supply chains (Caridi et al., 2014). Prior research has examined various aspects of SCV, including its definition (Francis, 2008), methods of measurement (Caridi et al., 2010), its impact on performance (Barratt and Oke, 2007), enabling technologies (Kim et al., 2011), operational processes that benefit from visibility (Prater et al., 2005), and organizational enablers and outcomes (Adielsson and Gustavsson, 2011; Wei and Wang, 2010). A consistent finding across this body of work is that better SCV supports informed decision-making, which in turn enhances performance across multiple dimensions of supply chain operations (Francis, 2008; Goh et al., 2009).

Industrial construction refers to the construction of capital-intensive process and energy facilities that are used for manufacturing purposes such as plants and factors (Freitas and Magrini, 2017). The types of facilities under industrial projects include chemical plants, paper mills, steel and aluminum mills, textile mills, food processing plants, pharmaceutical plants, oil and gas production facilities, power plants, manufacturing facilities, and refineries (Dumont et al., 1997). These projects are typically delivered under Engineering-Procurement-Construction (EPC) arrangements, characterized by engineered-to-order materials, appreciable prefabrication or offsite content, and complex commissioning (Barutha et al., 2021). Despite the strong foundation and demonstrated value of SCV in manufacturing and logistics, its application in construction, particularly in industrial projects, remains limited and under-researched (Dharmapalan and O’Brien, 2018). This lack of SCV implementation is notable given the high interdependence among stakeholders, the dynamic nature of construction workflows, and the prevalence of material coordination issues (Collins et al., 2017).

Unlike manufacturing, construction supply chains are temporary, multi-tiered networks that often lack shared workflows and interoperable systems (Azambuja and O’Brien, 2009). Three construction-specific visibility gaps are recurrent: (i) fragmented data flows across owners, EPC/contractors, designers, and suppliers/fabricators, which impede traceability of materials (O’Brien et al., 2017); (ii) coordination lags between offsite fabrication yards and jobsites that lead to early/late deliveries and disrupt installation sequences (Dharmapalan et al., 2022); and (iii) limited integration between contractor ERP/scheduling systems and supplier databases that delays status updates and decision-making (Bemelmans et al., 2012). These conditions indicate that SCV approaches developed for stable, repeatable production environments are insufficient when transferred to the dynamic, project-based context of construction. A key contributor to these conditions is the insufficient exchange of accurate and timely information across project stakeholders (Young et al., 2011; Zhong et al., 2017), with well-documented consequences including costly expediting, inefficient inventory control, rework, diminished quality, reduced labor productivity, and safety risks (Caldas et al., 2014; Kaming et al., 1998). Accordingly, calls for improving visibility in construction supply chains have regularly emerged.

While past studies proposed various information technologies (IT)-based solutions to enable better information sharing (Ala-Risku and Kärkkäinen, 2006), their adoption and implementation in field settings remain slow and inconsistent (Li et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2016). One potential barrier to the successful implementation of SCV is the construction industry’s limited understanding of the specific project-level benefits associated with SCV (CII, 2018). Studies also indicate that a lack of structured understanding regarding these benefits hamper managerial decision-making and stakeholder engagement (Ekanayake et al., 2022), ultimately hindering investments in enabling technologies that could improve project performance (O’Brien et al., 2017). For instance, Ekanayake et al. (2022) emphasize that the construction industry’s understanding of SCV’s benefits is critical for fostering resilience against disruptions and improving project outcomes, and that stakeholders must first recognize how information sharing enhances not only their own performance but that of other partners within the supply chain (Ekanayake et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2023).

The goal of the study is to address this gap by examining the perceived benefits of SCV in industrial construction projects. Building on prior work by Dharmapalan et al. (2021a), which introduced the concept and current state of SCV in this context, the study aims to quantitatively assess the benefits of SCV from the perspective of key supply chain stakeholders. For the purposes of this study, the focal stakeholder groups are owners/operators, EPC/contractors, designers/engineers, and suppliers/fabricators. Specifically, it seeks to identify and define the benefits associated with SCV relevant to industrial construction and to explore how these benefits are perceived across the four stakeholder groups in the supply chain.

2 Literature review

2.1 Theoretical framework for SCV

Supply chain visibility (SCV) originated in the broader supply chain management and logistics literature and has multidisciplinary roots (Fawcett et al., 2007). The authors therefore adopt two complementary primary lenses to explain when and why SCV yields benefits in industrial projects. First, using Resource-Based View (RBV), the authors conceptualize SCV as an inter-organizational capability assembled from data assets (e.g., clean master data, interoperable schemas), partner-specific IT interfaces, and organizational routines (exception management, cross-tier coordination). As such, SCV can be valuable, rare, and difficult to imitate (Grant, 1991; Wernerfelt, 1984). Next, Information Processing Theory (IPT) clarifies when SCV pays off: as uncertainty, interdependence, and equivocality rise in multi-tier networks, organizations require richer, timelier, and more lateral information flows. SCV meets that need by improving information quality (accuracy, timeliness, relevance) and decision readiness (e.g., track-and-trace, delivery status, capacity signals, field/installation feedback) (Barratt and Oke, 2007; Goh et al., 2009). Together, RBV provides the capability logic (who can realize value and where), and IPT provides the performance logic (information-fit under uncertainty). While IPT and RBV remain the primary lenses that motivate the lines of inquiry and frame the analysis, the authors acknowledge Institutional (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983) and Relational considerations (Dyer and Singh, 1998) as contextual/sensitizing influences on adoption and emphasis and use them to interpret selected patterns.

2.2 SCV in industrial construction projects

Building on the multi-theoretic framing above, industrial construction presents a high-uncertainty, high-interdependence setting in which the information-processing need (IPT) is acute and the payoffs to a routinized visibility capability (RBV) are potentially large. Industrial construction projects increasingly rely on off-site or modular construction methods, wherein fabrication and value-added activities traditionally performed on-site are transferred to controlled factory settings. This approach has been widely adopted to mitigate on-site challenges such as space constraints, permitting delays, weather conditions, and labor availability, while simultaneously reducing waste, improving quality, and enhancing schedule certainty (Haas and Fagerlund, 2002; Han et al., 2012). Execution, however, depends on precise coordination across owners/operators, EPC/contractors, designers/engineers, suppliers/fabricators, logistics providers, and site teams, each contributing to the flow of materials from specification to installation (Hu et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2019). The smooth transfer of components across this fragmented network depends on the timely exchange of accurate and relevant information regarding material status. The availability of this information across the supply chain, enabling informed and coordinated decision-making, is referred to as SCV (Dharmapalan et al., 2021b).

To gain a thorough understanding of SCV and related research in the construction sector, a systematic scoping review was conducted using the Scopus database. The initial search strategy targeted publications focusing on SCV and information sharing within construction by applying the following keywords to article titles, abstracts, and keywords: (“Supply Chain Visibility” OR “SCV” OR “Information Sharing”) AND (“Construction” OR “Construction Industry” OR “Industrial Construction”). The search was refined to include only peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers published in English, with duplicates and non-relevant sources removed.

Several studies in the construction field have emphasized the importance of SCV and highlighted the risks of limited visibility. For instance, Ala-Risku et al. (2010) demonstrated through a case study in the telecom sector how aligned metrics and incentives between project management and supply chain actors are critical to enabling SCV. In a more comprehensive effort, Koc and Gurgun (2021) conducted a content analysis and stakeholder workshop to identify 135 risks across the construction supply chain lifecycle, 16 of which directly related to inadequate information sharing and limited visibility at various phases. Recent construction-relevant studies locate visibility at the center of resilience, sustainability, and offsite integration, linking traceability and inter-tier coordination to disruption management (Iqbal et al., 2024), circular material flows (Iqbal et al., 2025a; 2025b), and energy-efficient supply chains (Iqbal et al., 2023) in industrialized and prefabricated contexts. Iqbal et al. (2023), for instance, highlight that strong supplier coordination, transparent information exchange, and top management support are critical success factors for energy-efficient supply chains. While their focus is on sustainability outcomes, the underlying mechanism of visibility across supply chain tiers closely aligns with SCV principles. Their findings further validate the growing recognition of SCV as a foundational capability for sustainable and performance-driven supply chain design.

Research that analyzes explicitly SCV in the construction industry is limited (Dharmapalan and O’Brien, 2018). Dharmapalan et al. (2021a) identified and defined 79 essential information items that must be shared between project stakeholders to improve visibility in industrial construction supply chains. In another study, Dharmapalan et al. (2021b) evaluated the status of visibility for the leading supply chain stakeholders (owners, contractors, designers, and suppliers) at common supply chain locations and material types used on industrial construction projects. An example finding of the study was that owner, contractor, and designer groups have less than adequate visibility at kitting site, tier-2 supplier location, and transportation compared to supplier groups who have adequate to extremely high visibility. These asymmetries motivate the focus on how SCV benefits are perceived by each role. These benefits of SCV, as cited in the literature, are reviewed next.

2.3 Benefits of SCV

In line with the theories above, the study defines SCV benefits as observable improvements that arise when decision-quality information reduces uncertainty and coordination loss (IPT) and enables superior deployment of resources and routines (RBV). Since the benefits of SCV are primarily due to effective information sharing, a targeted search was performed to capture research specifically addressing benefits to SCV or information sharing in the construction contexts. This search included combinations of keywords such as (“Supply Chain Visibility” OR “Information Sharing”) AND (“Benefits” OR “Advantages” OR “Opportunities”) AND (“Construction Industry” OR “Construction Sector”), restricted to titles, abstracts, and keywords.

Despite the practical importance of SCV in construction, the literature remains relatively limited, with most available studies reporting isolated or context-specific benefits, often focused on technology implementation or material tracking use cases. For instance, Akcay et al. (2017) traced the flow of structural steel information from design through erection to illustrate how poor visibility impedes performance. In terms of tools, a substantial body of literature has focused on using information technologies (IT) to enhance visibility. These include applications of RFID (Song et al., 2006), GPS-enabled tracking (Caldas et al., 2006), and integrated RFID–GPS systems (Torrent and Caldas, 2009) for tracking engineered materials on site. Similar technologies have been applied to monitor prefabricated components at off-site yards (Ergen and Akinci, 2008), demonstrating the potential for real-time visibility across spatially distributed supply chains. While some of these studies report project-level benefits such as process automation, reduced material handling errors, and productivity gains (Dharmapalan and O’Brien, 2018), their focus is largely on the benefits of implementing specific IT systems, rather than on the broader benefits of SCV itself.

Owing to limited depth of research on SCV benefits within the construction industry, the authors extended the literature review to the broader supply chain management and logistics domain, where SCV concepts and associated benefits have been studied more extensively. These studies reveal a wide range of SCV outcomes that span strategic, tactical, and operational levels. Kembro et al. (2014) identified four aspects of information sharing, as part of a study to explore the theoretical lenses used in literature to understand information sharing in supply chains. One of the aspects focused on the ‘why’ aspect or positive effects of sharing of information. Their review highlighted benefits including improved forecasts, reduced inventory levels, improved long-term relationships due to better coordination of processes, enhanced planning, and decision-making in the supply chain. In another study, Kembro and Selviaridis (2015) investigated demand-related information sharing across multiple supply chain tiers and classified the perceived benefits at strategic, tactical, and operational levels. Reported advantages included optimal capacity utilization, increased productivity, reduced inventory buffers, and better risk management. Other empirical studies confirm these findings. Corbett and Tang (1999) and Gavirneni et al. (1999), in their respective studies, found that information sharing enables tighter coordination of material movements, improved price and order planning, and more efficient inventory management.

Researchers have also suggested benefits as a result of high SCV. Chopra (2019) pointed out that in order to improve synchronization of the supply chain, information visibility regarding sales and operations planning must be shared. Visibility, in this case, helps to reduce the bullwhip effect, whereby small fluctuations in demand become amplified upstream in the supply chain. SCV reduces this variability by providing real-time demand signals and improving forecast accuracy (Dejonckheere et al., 2004; Kaipia and Hartiala, 2006; Lee and Whang, 2000). In turn, this enables more reliable production and procurement planning, as well as more responsive replenishment strategies (Premus and Sanders, 2008; Sahin and Robinson, 2002).

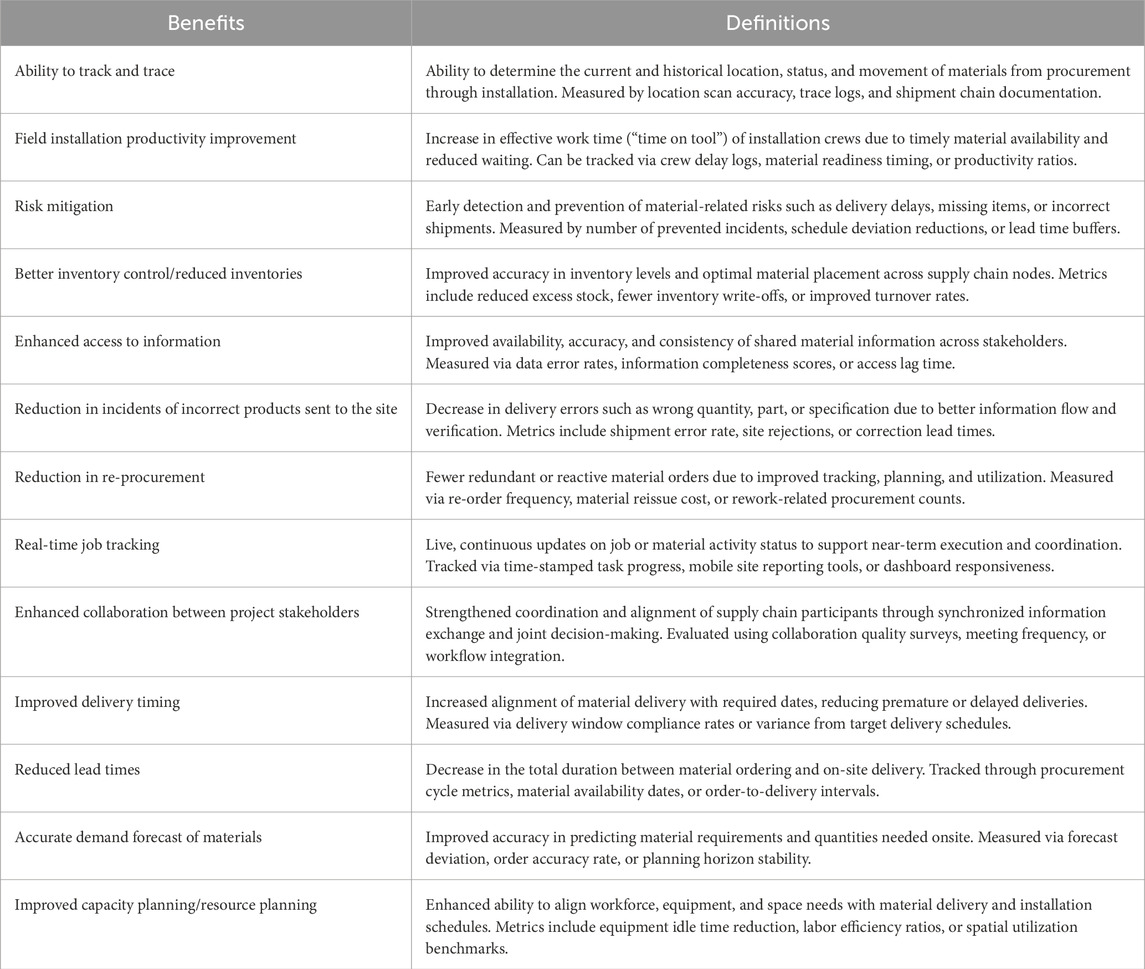

Additional benefits cited in the literature include better responsiveness (Armistead and Mapes, 1993), improved planning and replenishment (Patterson et al., 2004), more accurate demand forecasting, shortened lead times, improved inventory quality, and enhanced capacity planning and product quality (Huang and Gangopadhyay, 2004; Kaipia and Hartiala, 2006; Petersen et al., 2005). Other benefits documented include more accurate demand forecast, capacity planning and control, reduced lead times, improved capacity planning and control, and improved quality of products (Armistead and Mapes, 1993; Kaipia and Hartiala, 2006). Other researchers have also reported similar benefits in different contexts. Table 1 presents 16 benefits of SCV based on a thorough review of peer-reviewed articles and after accounting for duplicates and overlaps.

2.4 Research gap and questions

While SCV has been extensively studied in the broader supply chain and logistics literature, its application and investigation within the construction domain, particularly in industrial construction, remains underdeveloped. Existing construction studies emphasize technology exemplars rather than the broader, role-specific benefits of SCV. Moreover, there is limited understanding whether key stakeholder groups—owners, contractors, designers, suppliers—prioritize the same benefits or differ in ways that matter for implementation. This study addresses these gaps by empirically prioritizing SCV benefits for industrial construction and by comparing perceptions across roles guided by IPT’s information-fit logic and RBV’s capability logic. The research is driven by three questions:

RQ1 – Which SCV benefits are most important in industrial construction?

RQ2 – How do SCV benefit priorities differ across stakeholder groups (owners, contractors, designers, suppliers)?

RQ3 – To what extent is there alignment or divergence in benefit rankings across groups, and what operational factors may explain these differences?

To answer these questions, the study identifies and defines a construction-specific set of SCV benefits through literature review and Delphi-informed expert workshops, assesses their importance using the Relative Importance Index (RII) overall and by stakeholder group, test for statistical differences using the Kruskal–Wallis method, and evaluates intergroup alignment using percentage agreement and Kendall’s tau correlation coefficient. The next section details the methodology adopted to achieve these objectives.

3 Research methods

The research process involved identifying and defining SCV benefits for industrial construction, measuring the SCV benefits using a survey questionnaire, and analyzing the solicited survey data to assess and compare benefit perceptions.

3.1 Identification and definition of SCV benefits

The first phase involved compiling a list of SCV benefits through a review of supply chain and logistics literature (results in literature review section above). However, since these benefits were originally developed for manufacturing and general SCM contexts, translation for construction-specific application was necessary. To achieve this, the authors conducted structured workshops with a North American expert panel consisting of 18 professionals: four owners, nine contractors, two designers, and three suppliers. These experts had extensive experience (average = 15 years, range = 5–30 years) in managing supply chains for industrial projects in sectors such as petrochemical, power, pharmaceutical, and manufacturing. Workshops followed the protocol of Gibson and Whittington (2010), which supports refinement and consensus through facilitated interaction.

The workshops followed a Delphi-informed structure in which panelists individually reviewed each benefit, then participated in group discussions to reach consensus on their definitions, redundancies, and terminology. To strengthen construct validity, retention of the benefits was governed by explicit criteria: (i) literature prevalence (items repeatedly reported in peer-reviewed studies); (ii) construction relevance and project-level observability; (iii) clarity and non-overlap (benefits represent outcomes and exclusion of antecedents such as “IT integration” and consolidation of duplicates); (iv) understandable and can be rated by owners, contractors, designers, and suppliers; and (v) parsimony (set of distinct benefits that still captures all the meaningful ways SCV creates value). This iterative process led to the consolidation and refinement of the benefit list to 13 distinct, construction-relevant SCV benefits (Table 2). Each benefit was assigned a definition grounded in both literature and industry terminology to ensure clarity and consistency across survey respondents.

3.2 Measurement of SCV benefits

The second phase focused on measuring how industrial construction stakeholders perceive the importance of the 13 defined SCV benefits. To accomplish this, the authors developed and administered a structured survey using Qualtrics survey software targeting the key stakeholder groups: owners, contractors, designers, and suppliers.

The survey instrument included a cover page with a definition of SCV and the 13 benefit, followed by two sections: Section 1 was a general section that collected respondent’s background information (title, work experience, and company category). Section 2 asked the respondents to rate the 13 benefit variables on a four-point Likert scale (1 = Not a benefit, 2 = Minor benefit, 3 = Moderate benefit, 4 = Extreme benefit). This format was chosen to avoid midpoint bias and encourage directional responses, consistent with recommendations from Weijters et al. (2010), who found that even-numbered scales reduce agreement bias and better differentiate respondent opinions in certain contexts. While midpoint omission may increase the cognitive load for ambivalent respondents, the format was appropriate given the nature of the evaluative task, which required participants to reflect on clear benefit outcomes rather than subjective preferences. Similar 4-point scales have been used in civil engineering and construction research to support clearer prioritization and simplify subsequent ranking analyses (Assaf et al., 1995; Cafiso et al., 2021; Khoja and Danylenko, 2024).

The survey was piloted with the same expert panel to validate clarity and survey usability before wider distribution. To mitigate confirmation bias from panel reuse, the structured workshops were restricted to content validation (translation to construction terminology, definition clarity, redundancy removal, construction terminology) and the pilot responses were not included in the analytic dataset.

Following the pilot test, the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas at Austin (IRB ID: STUDY00000907). The questionnaire was distributed electronically over 6 months using snowball sampling, starting with the industry expert panel who shared it with contacts in the industrial construction sector, who then forwarded it within their networks. This method was appropriate given the specificity of the target population (Patton, 2014; Salganik and Heckathorn, 2004).

3.3 Analysis of SCV benefit perceptions

3.3.1 Relative importance index (RII)

The relative importance index (RII) (Equation 1) was calculated to rank the 13 benefits in terms of their perceived importance. The Relative Importance Index (RII) transforms ordinal four-point Likert responses into normalized [0–1] scores and derive rankings commonly reported in construction management research (El-Gohary and Aziz, 2013; Gündüz et al., 2013):

where

3.3.2 Stakeholder comparison using Kruskal–Wallis test and Kendall’s tau rank correlation coefficient

To identify and compare the benefits for leading supply chain participants, the survey data was segmented by stakeholder type. This involved, first, assessing the rankings and importance level of the benefits using the above RII method for the owner, contractor, designer, and supplier groups separately.

The Kruskal–Wallis (KW) test was used to check if statistically significant differences existed between the viewpoints of the four groups regarding the 13 benefits. KW is appropriate for multiple group comparison analysis when the groups have unequal sample sizes, have non-normal data within them, and the dependent variable scale is not continuous (Ramsey and Schafer, 2012). With 13 KW tests at α = 0.05, the chance of at least one false positive under the global null is about 49%. To control any false positives, the p-values are adjusted using Bonferroni Holm (Ramsey and Schafer, 2012). Also, in the event where a Kruskal–Wallis test yielded p < 0.05, Dunn’s post hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment is conducted.

To evaluate consensus between stakeholder groups, benefit rankings were compared using Rank Agreement Analysis, as applied in construction studies (Okpala and Aniekwu, 1988; Sony et al., 2021; Zhang, 2005). The method calculates the Percentage Agreement (PA) between two stakeholder groups as calculated using Equation 2:

Where PD is the percentage disagreement and is defined by Equation 3. RAF is the rank agreement factor (Equation 4) and shows the average absolute difference in ranking the benefit variables between the two groups. RAFmax (maximum rank agreement factor) is defined as the maximum absolute difference between all N variables’ rankings; when the two groups are in complete disagreement, they ranked variables in opposite orders. RAFmax is given by Equation 5. Ri1 and Ri2 are the ith variable ranks in group 1 and 2, N is the number of variables, and j = N-i+1.

To complement the descriptive PA results, the agreement between rankings of the groups was checked using the Kendall’s tau rank correlation coefficient (Field, 2009; Schaeffer and Levitt, 1956). Kendall’s tau-b is a non-parametric test that measures the strength and direction of the association between two ranked variables, especially when the data set has many tied ranks (Kendall, 1948). Specifically, pairwise concordance of the 13 ranked benefits was tested using Kendall’s τ-b with Bonferroni-Holm adjustment for multiple comparisons. All analyses were conducted in SPSS Statistics V26.0.

4 Results and discussion

This section presents the findings of the study. Quantitative results are supplemented by practical insights gathered from the expert panel to contextualize the findings.

4.1 Benefits of SCV for industrial construction

Through the structured, Delphi-based workshop process, this study identified and defined a set of 13 benefit variables associated with supply chain visibility (SCV) in industrial construction. The iterative process drew on multiple rounds of expert input to refine the benefit list, ensuring that each variable reflected both theoretical grounding and practical relevance to real-world project environments.

The panel, composed of representatives from key stakeholder groups—owners, contractors, suppliers, and designers—brought diverse insights informed by direct experience managing procurement, logistics, and supply chain operations in industrial construction. Their collective input helped tailor the benefit variables to the specific operational and informational dynamics of industrial projects, which differ markedly from other sectors such as manufacturing or retail.

As a result, the finalized list of 13 SCV benefit variables captures a wide range of performance outcomes. These benefits were operationalized through clear, expert-vetted definitions to support consistency in interpretation and evaluation. The full list of benefits and their definitions is provided in Table 2. Together, these variables offer a structured framework for assessing how improved visibility contributes to project and supply chain performance in industrial construction.

For the industry survey, a total of 218 responses were received from across North America. The item prompts for the 13 benefit ratings were not mandatory. Consequently, there was some item-level missingness for the core variables. For each item, the missing responses for that item were dropped for that item only (the same respondent could still be used for other items where they answered). Of the respondents who provided profile data (n = 165), 32 were owners (19.4%), 61 contractors (37.0%), 35 designers (21.2%), and 37 suppliers (22.4%), all with industrial construction experience. The average respondent had 21 years of experience (range = 1–50 years), and all stakeholder group samples met the minimum recommended size for subgroup analysis (n ≥ 30) (Ott and Longnecker, 2015).

4.2 Overall importance of SCV benefits

The frequency of each rating for the SCV benefits is presented in Table 3. The Relative Importance Index (RII) was calculated for each benefit to determine perceived importance. Table 4 reports RII scores, importance level, and rankings overall and by stakeholder group.

The first research question focused on identifying the top ranked SCV benefits. The top four ranked benefits across all respondents were: 1. Risk mitigation (RII = 0.901), 2. Ability to track and trace (RII = 0.878), 3. Field installation productivity improvement (RII = 0.874), and 4. Improved delivery timing (RII = 0.857). These four have also been reported as moderate to extreme benefits by at least 90% of the respondents (Table 3). Consistent with IPT, the highest-ranked payoffs are those that most directly reduce uncertainty and coordination loss: risk mitigation, track-and-trace, field-installation productivity, and delivery timing (Table 4). Risk mitigation being the most important benefit is in agreement with a survey that was conducted of nearly 400 supply chain executives worldwide (Butner, 2007). 70% of supply chain executives ranked visibility as their top challenge, citing risk management as more important than cost control or client demand responsiveness.

The ability to track and trace was ranked second, reflecting its central role in enabling real-time material status updates across the supply chain. This results supports the findings of Ergen and Akinci (2008) and Young et al. (2011), who emphasized that enhanced visibility improves traceability of materials. This traceability, in turn, supports timely material delivery, which contributes directly to field installation productivity, ranked third. Grau et al. (2009) demonstrated that on-time delivery leads to improved “time on tools” for field crews, enhancing schedule adherence and crew efficiency. Improved delivery timing, ranked fourth, is a direct result of better forecasting and material coordination. This aligns with broader findings from energy-efficient and green construction logistics research. Iqbal et al. (2024) and Iqbal et al. (2023) contend that timely material tracking is not only a productivity enabler but also foundational to reducing energy waste, transport redundancies, and environmental footprint in prefabricated and industrialized projects. The recent review by Razak et al. (2023) reinforces this, identifying traceability as a key enabler of supply chain resilience due to its impact on timely delivery and risk prevention. Conceptually, this ordering aligns with Information Processing Theory: more timely and reliable information reduces uncertainty, stabilizes sequencing and replenishment decisions, and yields downstream productivity gains.

Some benefits commonly emphasized in manufacturing literature, such as reduced lead times, were ranked lower in the current study (overall RII = 0.766; rank = 13). This discrepancy mirrors earlier findings by Kaipia and Hartiala (2006), who highlighted reduced lead time as a central SCV benefit in stable manufacturing systems. However, the expert panel in this study noted that industrial construction often deals with engineered-to-order (ETO) materials, which have more variable and project-specific lead times, limiting SCV’s impact on this metric. In ETO settings, lead time is driven by design maturation, approvals, and bespoke fabrication constraints; visibility helps manage risk but cannot fully compress these structural drivers, so respondents prioritize uncertainty reduction over absolute time compression.

Reduction in re-procurement was also ranked low despite its relevance to material efficiency. According to panel members, this may be due to the multifactorial causes of rework. For example, late design changes or field conditions, which SCV cannot directly address. This is consistent with Somapa et al. (2018), who emphasized that visibility’s operational benefits depend on the quality, completeness, and contextual relevance of shared information, not just access.

4.3 Comparison of SCV benefits across stakeholder type

The next research question inquired whether owners, contractors, designers, and suppliers weighed the SCV benefits differently. An analysis of stakeholder-specific rankings (Table 4) revealed broad alignment with the overall RII-based ranking of top four SCV benefits, particularly among the owner, contractor, and designer groups. For owners, the top four benefits were field installation productivity improvement, improved delivery timing, risk mitigation, and ability to track and trace. Contractors rated 12 out of 13 benefits in the “High” importance category.

Designers were more selective, with only five benefits meeting the high-importance threshold, but their top-rated benefits—risk mitigation, ability to track and trace, field productivity improvement, and improved delivery timing are consistent with overall trends. One notable exception was the designer group’s relatively higher ranking of lead time reduction, which contrasted with its lower ranking among other groups. This divergence may reflect designers’ upstream position in the supply chain and their need to align design outputs with procurement schedules. As noted by Burmeister and Liang (2016), upstream visibility is essential for triggering accurate downstream planning, especially in fragmented, multi-tiered project networks.

Suppliers prioritized a distinct set of benefits. Their top-ranked benefit was ability to track and trace, followed by risk mitigation and improved capacity/resource planning. Interestingly, several benefits were tied at rank 4: Improved delivery timing, Better inventory control/reduced inventories, Enhanced access to information, and Accurate demand forecast of materials. Notably, field installation productivity improvement was ranked lower by suppliers than by other stakeholders. This finding is consistent with Iqbal et al. (2025a), Iqbal et al. (2025b), who highlight the importance of early-stage forecasting and supplier engagement for reducing procurement waste and inventory mismatches in high-turnover construction logistics chains. It reinforces why suppliers place high value on demand visibility even if downstream stakeholders under-prioritize it. From an economic/governance perspective, suppliers operate under capacity, batch, and procurement constraints that make demand visibility central to their economics (O’Brien and Fischer, 2000). Accurate forecasts lower changeover and overtime costs, stabilize procurement of raw materials, and reduce the risk of undesirability, benefits that accrue directly to suppliers even before materials ship. The expert panel echoed this as well: forecasting information quality and alignment are more critical than frequency of updates, consistent with Somapa et al. (2018).

Across groups, risk mitigation consistently appeared in the top three, the foundational purpose of SCV viz. to enhance visibility, reduce uncertainty, and support proactive risk management across the supply chain (Christopher and Lee, 2004; Faisal et al., 2006). Track-and-trace was also universally valued, though the expert panel pointed out that the required granularity differs by role. For instance, owners often need milestone-level status; contractors need item-level data for installation planning and sequencing. This tiered need for information is consistent with findings by Lamming et al. (2001), who discussed differentiated visibility thresholds across supply chain tiers. Inventory-related benefits were assigned greater importance by contractors and suppliers, which is expected given their direct roles in managing laydown yards and delivery logistics. Contractors and suppliers bear working-capital, storage, and obsolescence risks; improved visibility reduces buffers, double-handling, and premium freight. Owners, by contrast, optimize schedule assurance and often prefer “just-in-case” buffers to protect commissioning dates, so inventory savings are less salient (Ballard and Howell, 1998). Overall, these findings indicate that perceived SCV value is role-contingent: stakeholders prioritize the visibility signals that most directly reduce the operational uncertainties they personally manage. This role-contingent emphasis is consistent with RBV: each group focuses on the kind of visibility that helps them the most, based on what they do, what they have, and the decisions they need to make.

The Kruskal–Wallis tests revealed no statistically significant median differences (BH adjusted p > 0.05) among the four stakeholder groups for any of the 13 benefit variables (Table 4). The effect sizes were very small (ɛ2 ≈ 0.00–0.03). Since no tests were significant, no post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted. Also, the statistical non-significance in this case indicates similarity in group-level medians but does not capture ranking variation. Accordingly, any cross-group variations discussed above are descriptive rather than inferential.

4.4 Rank agreement analysis between stakeholders

The third research question investigated alignment in rankings between stakeholder pairs. The rank agreement results using percentage agreement (PA) analysis as well as the Kendall’s tau-b test are depicted in Table 5.

The results showed the highest PA for Owner–Contractor (64.63%) and Contractor–Supplier (65.47%). Kendall’s tau-b confirmed statistically significant concordance for both pairs (Owner–Contractor τ-b = 0.555, adjusted p = 0.045; Contractor–Supplier τ-b = 0.578, adjusted p = 0.045). These patterns likely reflect the frequent and operationally intensive interactions between these groups, particularly during procurement, material delivery, and field installation. Strong alignment between these roles is consistent with the findings of Zhang et al. (2023), who noted that high-dependency interfaces foster synchronized expectations about visibility outcomes. The findings also underscore the contractor’s intermediary role bridging upstream strategic intent and downstream execution. This is consistent with the idea of a focal ‘system integrator’ coordinating information across tiers—an orchestration role long noted in operations management on integrators in vertically disaggregated value chains (Parker et al., 2002). This concentration of agreement at contractor-centered interfaces corresponds with IPT and RBV: information fit is easiest to achieve where integrative capability and dense information flows co-locate.

Conversely, the agreement was lowest for Owner–Supplier (PA = 31.70%) and Designer–Supplier (PA = 36.58%), with non-significant tau-b (0.162; adjusted p = 0.910 for both). These weaker dyads likely reflect limited direct interaction and divergent expectations between stakeholders who operate at different points in the supply chain. For example, suppliers are typically engaged during execution or late procurement, while owners and designers are focused on early planning and strategic oversight. The patterns align with the prior findings of Kembro and Selviaridis (2015), who found that the depth, frequency, and type of stakeholder interaction strongly influence alignment in visibility expectations. This interpretation also aligns with recent findings by Choi and O’Brien (2025), who reported that suppliers are often engaged too late to influence upstream choices in projects, despite having the potential to add significant value. The observed disagreement between owners and suppliers highlights a key opportunity for SCV improvement through more inclusive planning and alignment across stakeholder tiers.

5 Significance and implications

5.1 Theoretical implications

The study contributes to the construction supply chain management literature by providing an empirically grounded, stakeholder-informed assessment of SCV benefits specific to industrial construction. While prior research has emphasized the value of SCV in manufacturing and logistics, this study extends those insights to the project-based, multi-actor context of construction where visibility needs, decision timelines, and roles differ considerably.

The findings confirm that SCV benefits are widely recognized across stakeholder groups, with high RII rankings for risk mitigation, ability to track and trace, improved delivery timing, and field installation productivity improvement. However, the observed differences in benefit prioritization highlight that SCV is experienced and valued differently depending on proximity to material flows and planning responsibilities. For instance, contractors and suppliers emphasized inventory control and resource planning, while designers placed greater weight on lead time reduction, an upstream concern. These patterns reinforce the idea that SCV, while conceptually unified, is experienced differently depending on proximity to material flow and task interdependence. This role-contingent pattern aligns with Information Processing Theory (SCV as uncertainty reduction tailored to the information needs of each role) (Goh et al., 2009; Somapa et al., 2018) and the Resource-Based views (SCV as a capability that enables sensing, coordination, and rapid reconfiguration where the task demands it most) (Barratt and Oke, 2007).

The contractor’s bridging role, evidenced by significant Owner–Contractor and Contractor–Supplier concordance corresponds with Information Processing Theory. Specifically, the alignment pattern is consistent with Winch’s (Winch, 2006) information-processing view of construction projects as temporary coalitions of firms in which the main contractor functions as the central systems integrator: aggregating, translating, and routing visibility signals across tiers. The lower owner–supplier agreement is consistent with Institutional perspective (Wei and Wang, 2010), where sparse early engagement and differing accountability organizations limit data sharing and alignment. Together, SCV in construction emerges not as a flat data layer but as a layered, interaction-dependent capability shaped by organizational roles and governance.

5.2 Practical implications

For practitioners, the results provide clear direction on where SCV efforts can be most impactful. Benefits such as risk mitigation, ability to track and trace, improved delivery timing, and field installation productivity improvement are seen as high-value outcomes that justify investment in visibility strategies. These can serve as a benchmark for project teams and supply chain managers when prioritizing SCV-related initiatives. In practice, this implies prioritizing event-based status data (for risk detection), item-level traceability (for coordination), and schedule-linked material milestones (for field productivity).

The alignment in benefit perceptions between contractors and both owners and suppliers highlight the contractor’s central role in SCV implementation. SCV solutions focused on contractor-led procurement, logistics, and field coordination are likely to gain traction due to this embedded alignment. Actionably, owners can designate contractors as “visibility integrators,” tasking them to orchestrate shared data standards, milestone definitions, and exception-management workflows with upstream suppliers and designers. However, the low agreement between owners and suppliers signals a need for greater coordination, earlier supplier engagement, and shared planning processes. Early-involvement protocols (e.g., design-assist windows, joint forecasting, and contract clauses for data interfaces) can close this gap.

Beyond operational improvements, the study highlights SCV as a mechanism for changing long-standing cultural barriers in the construction industry. By showing how visibility leads to measurable performance gains, the findings provide an evidence base to overcome reluctance around information sharing, especially in environments where trust and contractual boundaries have traditionally limited transparency. This supports governance moves such as including minimum data-sharing requirements, role-specific dashboards, and performance-based incentives for timely, accurate data.

Achieving the full benefits of SCV, however, requires more than technology. It demands a shift from dyadic relationships to a system-wide, network-oriented model, where all stakeholders, owners, contractors, designers, suppliers are part of a shared visibility framework. This includes not only digital integration but also non-technological enablers such as leadership commitment, standardized data protocols, role-specific training, and inter-organizational governance. Where feasible, owners should specify data standards and interface requirements at contract award, and contractors should operationalize them through supplier onboarding, data quality checks, and issue-response service level agreements.

6 Conclusion

Supply chain visibility (SCV) is a critical capability for improving coordination, risk management, and productivity in industrial construction projects. This study advances the understanding of SCV by addressing three lines of inquiry: the relative importance of SCV benefits in industrial construction, cross-stakeholder differences in the SCV benefits, and the extent of alignment or divergence in the SCV benefit rankings across stakeholder groups. Across all respondents, risk mitigation, ability to track and trace, field installation productivity, and improved delivery timing consistently ranked as the top priorities. These results suggest a broad recognition of SCV’s strategic and operational value across the industrial construction supply chain. For all the SCV benefits, no significant median differences were found across owners, contractors, designers, and suppliers for any of the 13 benefits (Kruskal–Wallis, adj. p > 0.05); with designers placing higher priority on lead-time reduction and suppliers emphasizing track-and-trace and capacity/resource planning. Regarding alignment in ranking between stakeholder pairs, agreement is strongest for owner–contractor and contractor–supplier (PA ≈ 65%, τ-b ≈ 0.56–0.58; adj. p-value<0.05) and weakest for owner–supplier and designer–supplier, underscoring the contractor’s bridging role.

This study makes three primary contributions to the field. First, it provides a quantitative, stakeholder-informed foundation for evaluating SCV benefits in the construction sector. Second, it refines and contextualizes benefit definitions, enabling more consistent basis for future research studies. Third, it offers comparative insights across stakeholder roles, helping to inform both policy and practice related to visibility initiatives. From a practical standpoint, the benefit rankings offer a benchmark for prioritizing SCV investments, aligning communication strategies, and designing role-specific implementation plans. They also point to the importance of coordinated action across supply chain tiers, particularly leveraging contractors’ central role in aligning upstream and downstream partners. Anchored in IPT and RBV, the study supports an account of SCV as a capability that improves information-processing fit under project uncertainty, yielding broad cross-role consensus with role-specific accents and the strongest alignment at contractor-centered interfaces.

While this study was carefully designed, some limitations must be acknowledged. The use of perception-based survey data introduces potential for bias based on role, experience, or context. While this study emphasizes external validity via a large, role-diverse sample, future work should triangulate perceived benefits with qualitative cases and archival performance metrics (e.g., before/after SCV deployments, interview-based process tracing, or digital-twin simulations) to strengthen construct validity and replicability. Additionally, the dataset reflects the North American industrial construction and a mix of process/energy sectors. As such, sectoral and regional effects were not controlled, which may limit generalizability to other regions and sectors. Future research should aim to validate and expand these findings through international studies, stratified sampling by sector, qualitative investigations, and longitudinal tracking of SCV implementation outcomes. Although the study interpreted the observed patterns through established theoretical lenses, these mechanisms were not directly tested in this study; future work should directly measure capability maturity and institutional pressures to test whether they moderate the IPT/RBV relationships observed here. Furthermore, future studies could assess SCV in terms of specific dimensions of information quality such as accuracy, accessibility, relevance etc., thereby offering a more granular view of where breakdowns occur. It is also recommended to investigate the gap between stakeholders’ ideal information needs and what is currently transmitted through prevailing IT tools and workflows. Such findings would clarify how well existing systems are aligned with visibility goals and role-specific decision-making.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas at Austin. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

VD: Visualization, Software, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review and editing, Investigation. WO: Validation, Resources, Project administration, Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review and editing, Investigation. DM: Project administration, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition, Resources.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Construction Industry Institute (CII) and is based on the project titled Improved Integration of the Supply Chain in Materials Planning and Work Packaging—Research Team (RT)344.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adielsson, F., and Gustavsson, E. (2011). Applying supply chain visibility-a study at a company in the paper and pulp industry.

Akcay, E. C., Ergan, S., and Arditi, D. (2017). Modeling information flow in the supply chain of structural steel components. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 23, 753–764. doi:10.3846/13923730.2017.1281841

Ala-Risku, T., and Kärkkäinen, M. (2006). Material delivery problems in construction projects: a possible solution. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 104, 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2004.12.027

Ala-Risku, T., Collin, J., Holmström, J., and Vuorinen, J.-P. (2010). Site inventory tracking in the project supply chain: problem description and solution proposal in a very large telecom project. Supp Chain Mnagmnt 15, 252–260. doi:10.1108/13598541011040008

Armistead, C., and Mapes, J. (1993). The impact of supply chain integration on operating performance. Logist. Inf. Manag. 6, 9–14. doi:10.1108/09576059310045907

Assaf, S. A., Al-Khalil, M., and Al-Hazmi, M. (1995). Causes of delay in large building construction projects. J. Manag. Eng. 11, 45–50. doi:10.1061/(asce)0742-597x(1995)11:2(45)

Azambuja, M., and O’Brien, W. (2009). “Construction supply chain modeling: issues and perspectives,” in Construction supply chain management handbook (FL: CRC Press Taylor and Francis Group), 2.1–2.31.

Ballard, G., and Howell, G. (1998). “What kind of production is construction,” in Proc. 6 Th annual conf. Int’l. Group for lean construction, 13–15.

Barratt, M., and Oke, A. (2007). Antecedents of supply chain visibility in retail supply chains: a resource-based theory perspective. J. Operations Manag. 25, 1217–1233. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2007.01.003

Barutha, P. J., Jeong, H. D., Gransberg, D. D., and Touran, A. (2021). Evaluation of the impact of collaboration and integration on performance of industrial projects. J. Manag. Eng. 37, 04021037. doi:10.1061/(asce)me.1943-5479.0000921

Bemelmans, J., Voordijk, H., and Vos, B. (2012). Supplier-contractor collaboration in the construction industry: a taxonomic approach to the literature of the 2000-2009 decade. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 19, 342–368. doi:10.1108/09699981211237085

Bowersox, D. J., Closs, D. J., and Stank, T. P. (2000). Ten mega-trends that will revolutionize supply chain logistics. J. Bus. Logist. 21, 1.

Burmeister, C., and Liang, Y. (2016). Information exchange between a retailer and its supplier: types of information, benefits, and challenges in information exchange.

Cafiso, S., Pappalardo, G., and Stamatiadis, N. (2021). Observed risk and user perception of road infrastructure safety assessment for cycling mobility. Infrastructures 6, 154. doi:10.3390/infrastructures6110154

Caldas, C., Torrent, D., and Haas, C. (2006). Using global positioning system to improve materials-locating processes on industrial projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 132, 741–749. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2006)132:7(741)

Caldas, C. H., Menches, C. L., Reyes, P. M., Navarro, L., and Vargas, D. M. (2014). Materials management practices in the construction industry. Pract. Periodical Struct. Des. Constr. 20, 04014039. doi:10.1061/(asce)sc.1943-5576.0000238

Caridi, M., Crippa, L., Perego, A., Sianesi, A., and Tumino, A. (2010). Measuring visibility to improve supply chain performance: a quantitative approach. Benchmarking An Int. J. 17, 593–615. doi:10.1108/14635771011060602

Caridi, M., Moretto, A., Perego, A., and Tumino, A. (2014). The benefits of supply chain visibility: a value assessment model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 151, 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.12.025

Chen, Y., Okudan, G. E., and Riley, D. R. (2010). Sustainable performance criteria for construction method selection in concrete buildings. Autom. Constr. 19, 235–244. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2009.10.004

Choi, S., and O’Brien, W. J. (2025). Material suppliers’ perspective on collaboration in industrial construction projects. Front. Built Environ. 11, 1567594. doi:10.3389/fbuil.2025.1567594

Christopher, M., and Lee, H. (2004). Mitigating supply chain risk through improved confidence. Int. J. Phys. Distribution and Logist. Manag. 34, 388–396. doi:10.1108/09600030410545436

CII (2018). Improved integration of the supply chain in materials planning and work packaging part I: visibility (No. RT 344). Austin, TX: Construction Industry Institute.

Collins, W., Parrish, K., and Gibson Jr, G. E. (2017). Development of a project scope definition and assessment tool for small industrial construction projects. J. Manag. Eng. 33, 04017015. doi:10.1061/(asce)me.1943-5479.0000514

Corbett, C. J., and Tang, C. S. (1999). “Designing supply contracts: contract type and information asymmetry,” in Quantitative models for supply chain management (Springer), 269–297.

Dejonckheere, J., Disney, S. M., Lambrecht, M. R., and Towill, D. R. (2004). The impact of information enrichment on the bullwhip effect in supply chains: a control engineering perspective. Eur. J. operational Res. 153, 727–750. doi:10.1016/s0377-2217(02)00808-1

Dharmapalan, V., and O’Brien, W. J. (2018). Benefits and challenges of automated materials technology in industrial construction projects. Proc. Institution Civ. Engineers-Smart Infrastructure Constr. 171, 144–157. doi:10.1680/jsmic.19.00009

Dharmapalan, V., O’Brien, W. J., and Morrice, D. (2021a). Defining supply chain visibility for industrial construction projects. Front. Built Environ. 7, 1–16. doi:10.3389/fbuil.2021.651294

Dharmapalan, V., O’Brien, W. J., Morrice, D., and Jung, M. (2021b). Assessment of visibility in industrial construction projects: a viewpoint from supply chain stakeholders. Constr. Innov. 21, 782–799. doi:10.1108/ci-07-2020-0114

Dharmapalan, V., O’Brien, W. J., and Morrice, D. J. (2022). Defining and assessing visibility enablers in the industrial construction supply chain. J. Manage. Eng. 38, 04022024. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0001047

DiMaggio, P. J., and Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 48, 147–160. doi:10.2307/2095101

Dumont, P. R., Gibson Jr, G. E., and Fish, J. R. (1997). Scope management using project definition rating index. J. Manag. Eng. 13, 54–60. doi:10.1061/(asce)0742-597x(1997)13:5(54)

Dyer, J. H., and Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23, 660. doi:10.2307/259056

Ekanayake, E., Shen, G., Kumaraswamy, M., Owusu, E. K., and Xue, J. (2022). Capabilities to withstand vulnerabilities and boost resilience in industrialized construction supply chains: a Hong Kong study. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 29, 3809–3829. doi:10.1108/ecam-05-2021-0399

El-Gohary, K. M., and Aziz, R. F. (2013). Factors influencing construction labor productivity in Egypt. J. Manag. Eng. 30, 1–9. doi:10.1061/(asce)me.1943-5479.0000168

Ergen, E., and Akinci, B. (2008). Formalization of the flow of component-related information in precast concrete supply chains. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 134, 112–121. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2008)134:2(112)

Faisal, M. N., Banwet, D. K., and Shankar, R. (2006). Supply chain risk mitigation: modeling the enablers. Bus. Process Manag. J. 12, 535–552. doi:10.1108/14637150610678113

Fawcett, S. E., Osterhaus, P., Magnan, G. M., Brau, J. C., and McCarter, M. W. (2007). Information sharing and supply chain performance: the role of connectivity and willingness. Supply Chain Manag. An Int. J. 12, 358–368. doi:10.1108/13598540710776935

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS: (and sex and drugs and rock “n” roll). Third. ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Ltd.

Francis, V. (2008). Supply chain visibility: lost in translation? Supply Chain Manag. An Int. J. 13, 180–184. doi:10.1108/13598540810871226

Freitas, L. A. R. U., and Magrini, A. (2017). Waste management in industrial construction: investigating contributions from industrial ecology. Sustainability 9, 1251–17. doi:10.3390/su9071251

Gavirneni, S., Kapuscinski, R., and Tayur, S. (1999). Value of information in capacitated supply chains. Manag. Sci. 45, 16–24. doi:10.1287/mnsc.45.1.16

Ghoddousi, P., Poorafshar, O., Chileshe, N., and Hosseini, M. R. (2015). Labour productivity in Iranian construction projects. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 64, 811–830. doi:10.1108/ijppm-10-2013-0169

Gibson, G. E., and Whittington, D. A. (2010). Charrettes as a method for engaging industry in best practices research. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 136, 66–75. doi:10.1061/(asce)co.1943-7862.0000079

Goh, M., De Souza, R., Zhang, A. N., He, W., and Tan, P. S. (2009). “Supply chain visibility: a decision making perspective,” in Industrial electronics and Applications, 2009. ICIEA 2009. 4th IEEE conference on (IEEE), 2546–2551.

Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: implications for strategy formulation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 33, 114–135. doi:10.2307/41166664

Grau, D., Caldas, C. H., Haas, C. T., Goodrum, P. M., and Gong, J. (2009). Assessing the impact of materials tracking technologies on construction craft productivity. Automation Constr. 18, 903–911. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2009.04.001

Gündüz, M., Nielsen, Y., and Özdemir, M. (2013). Quantification of delay factors using the relative importance index method for construction projects in Turkey. J. Manag. Eng. 29, 133–139. doi:10.1061/(asce)me.1943-5479.0000129

Haas, C., and Fagerlund, W. (2002). “Preliminary research on prefabrication, pre-assembly, modularization and off-site fabrication in construction,” in Construction industry institute. University of Texas at Austin.

Han, S., Al-Hussein, M., Al-Jibouri, S., and Yu, H. (2012). Automated post-simulation visualization of modular building production assembly line. Automation Constr. 21, 229–236. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2011.06.007

Hu, X., Chong, H.-Y., Wang, X., and London, K. (2019). Understanding stakeholders in off-site manufacturing: a literature review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 145, 03119003. doi:10.1061/(asce)co.1943-7862.0001674

Huang, Z., and Gangopadhyay, A. (2004). A simulation study of supply chain management to measure the impact of information sharing. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. (IRMJ) 17, 20–31. doi:10.4018/irmj.2004070102

Huang, Y.-F., Phan, V.-D.-V., and Do, M.-H. (2023). The impacts of supply chain capabilities, visibility, resilience on supply chain performance and firm performance. Adm. Sci. 13, 225. doi:10.3390/admsci13100225

Iqbal, M., Ma, J., Ahmad, N., Ullah, Z., and Hassan, A. (2023). Energy-efficient supply chains in construction industry: an analysis of critical success factors using ISM-MICMAC approach. Int. J. Green Energy 20, 265–283. doi:10.1080/15435075.2022.2038609

Iqbal, M., Waqas, M., Ahmad, N., Hussain, K., and Hussain, J. (2024). Green supply chain management as a pathway to sustainable operations in the post-COVID-19 era: investigating challenges in the Chinese scenario. Bus. Process Manag. J. 30, 1065–1087. doi:10.1108/bpmj-05-2023-0381

Iqbal, M., Fan, Y., Ahmad, N., and Ullah, I. (2025a). Circular economy solutions for net-zero carbon in China’s construction sector: a strategic evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 504, 145398. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2025.145398

Iqbal, M., Wang, Z., Ahmed, N., and Ahmad, M. (2025b). From waste to treasure: transforming construction waste into concrete masonry blocks: challenges and solutions for environmental sustainability in emerging economies. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag., 1–28. doi:10.1108/ecam-01-2025-0080

Kaipia, R., and Hartiala, H. (2006). Information-sharing in supply chains: five proposals on how to proceed. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 17, 377–393. doi:10.1108/09574090610717536

Kaming, P., Holt, G., Kometa, S., and Olomolaiye, P. O. (1998). Severity diagnosis of productivity problems - a reliability analysis. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 16, 107–113. doi:10.1016/s0263-7863(97)00036-7

Kazaz, A., Manisali, E., and Ulubeyli, S. (2008). Effect of basic motivational factors on construction workforce productivity in turkey. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 14, 95–106. doi:10.3846/1392-3730.2008.14.4

Kembro, J., and Selviaridis, K. (2015). Exploring information sharing in the extended supply chain: an interdependence perspective. Supply Chain Manag. An Int. J. 20, 455–470. doi:10.1108/scm-07-2014-0252

Kembro, J., Selviaridis, K., and Näslund, D. (2014). Theoretical perspectives on information sharing in supply chains: a systematic literature review and conceptual framework. Supply Chain Manag. An Int. J. 19, 609–625. doi:10.1108/scm-12-2013-0460

Khoja, A., and Danylenko, O. (2024). Charting climate adaptation integration in smart building rating systems: a comparative study. Front. Built Environ. 10, 1333146. doi:10.3389/fbuil.2024.1333146

Kim, K. K., Ryoo, S. Y., and Jung, M. D. (2011). Inter-organizational information systems visibility in buyer–supplier relationships: the case of telecommunication equipment component manufacturing industry. Omega 39, 667–676. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2011.01.008

Klein, R., and Rai, A. (2009). Interfirm strategic information flows in logistics supply chain relationships. Mis Q. 33, 735–762. doi:10.2307/20650325

Koc, K., and Gurgun, A. P. (2021). Stakeholder-associated life cycle risks in construction supply chain. J. Manag. Eng. 37, 04020107. doi:10.1061/(asce)me.1943-5479.0000881

Lamming, R. C., Caldwell, N. D., Harrison, D. A., and Phillips, W. (2001). Transparency in supply relationships: concept and practice. J. Supply Chain Manag. 37, 4–10. doi:10.1111/j.1745-493x.2001.tb00107.x

Lee, H. L., and Whang, S. (2000). Information sharing in a supply chain. Int. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 1, 79–93. doi:10.1504/ijmtm.2000.001329

Lee, H. L., So, K. C., and Tang, C. S. (2000). The value of information sharing in a two-level supply chain. Manag. Sci. 46, 626–643. doi:10.1287/mnsc.46.5.626.12047

Li, H., Chan, G., Wong, J. K. W., and Skitmore, M. (2016). Real-time locating systems applications in construction. Automation Constr. 63, 37–47. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2015.12.001

Lotfi, Z., Mukhtar, M., Sahran, S., and Zadeh, A. T. (2013). Information sharing in supply chain management. Procedia Technol. 11, 298–304. doi:10.1016/j.protcy.2013.12.194

Luo, L., Qiping Shen, G., Xu, G., Liu, Y., and Wang, Y. (2019). Stakeholder-associated supply chain risks and their interactions in a prefabricated building project in Hong Kong. J. Manag. Eng. 35, 05018015. doi:10.1061/(asce)me.1943-5479.0000675

O’Brien, W. J., and Fischer, M. A. (2000). Importance of capacity constraints to construction cost and schedule. J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 126, 366–373. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2000)126:5(366)

O’Brien, W., Young, S., and Dharmapalan, V. (2017). IMM: automated materials identification, locating and tracking technology – case studies. Austin, Texas.

Okpala, D. C., and Aniekwu, A. N. (1988). Causes of high costs of construction in Nigeria. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 114, 233–244. doi:10.1061/(asce)0733-9364(1988)114:2(233)

Parker, G., Edward, G., and Anderson, Jr. (2002). From buyer to integrator: the transformation of the supply chain manager in the vertically disintegrating firm. Prod. Operations Manag. 11, 75–91. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2002.tb00185.x

Patnayakuni, R., Rai, A., and Seth, N. (2006). Relational antecedents of information flow integration for supply chain coordination. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 23, 13–49. doi:10.2753/mis0742-1222230101

Patterson, K. A., Grimm, C. M., and Corsi, T. M. (2004). Diffusion of supply chain technologies. Transp. J., 5–23. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20713571.

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research and evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Sage publications.

Petersen, K. J., Ragatz, G. L., and Monczka, R. M. (2005). An examination of collaborative planning effectiveness and supply chain performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 41, 14–25. doi:10.1111/j.1055-6001.2005.04102002.x

Prater, E., Frazier, G. V., and Reyes, P. M. (2005). Future impacts of RFID on e-supply chains in grocery retailing. Supply Chain Manag. An Int. J. 10, 134–142. doi:10.1108/13598540510589205

Premus, R., and Sanders, N. R. (2008). Information sharing in global supply chain alliances. J. Asia-Pacific Bus. 9, 174–192. doi:10.1080/10599230801981928

Ramsey, F., and Schafer, D. (2012). The statistical sleuth: a course in methods of data analysis. Cengage Learning.

Razak, G. M., Hendry, L. C., and Stevenson, M. (2023). Supply chain traceability: a review of the benefits and its relationship with supply chain resilience. Prod. Plan. Control 34, 1114–1134. doi:10.1080/09537287.2021.1983661

Sahin, F., and Robinson, E. P. (2002). Flow coordination and information sharing in supply chains: review, implications, and directions for future research. Decis. Sci. 33, 505–536. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5915.2002.tb01654.x

Salganik, M. J., and Heckathorn, D. D. (2004). 5. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 34, 193–240. doi:10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00152.x

Schaeffer, M. S., and Levitt, E. E. (1956). Concerning Kendall’s tau, a nonparametric correlation coefficient. Psychol. Bull. 53, 338–346. doi:10.1037/h0045013

Shi, Q., Ding, X., Zuo, J., and Zillante, G. (2016). Mobile internet based construction supply chain management: a critical review. Automation Constr. 72, 143–154. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2016.08.020

Somapa, S., Cools, M., and Dullaert, W. (2018). Characterizing supply chain visibility–a literature review. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 29, 308–339. doi:10.1108/ijlm-06-2016-0150

Song, J., Haas, C., and Caldas, C. (2006). Tracking the location of materials on construction job sites. J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 132, 911–918. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2006)132:9(911)

Sony, M., Antony, J., Mc Dermott, O., and Garza-Reyes, J. A. (2021). An empirical examination of benefits, challenges, and critical success factors of industry 4.0 in manufacturing and service sector. Technol. Soc. 67, 101754. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101754

Torrent, D., and Caldas, C. (2009). Methodology for automating the identification and localization of construction components on industrial projects. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 23, 3–13. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0887-3801(2009)23:1(3)

Wei, H.-L., and Wang, E. T. (2010). The strategic value of supply chain visibility: increasing the ability to reconfigure. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 19, 238–249. doi:10.1057/ejis.2010.10

Weijters, B., Cabooter, E., and Schillewaert, N. (2010). The effect of rating scale format on response styles: the number of response categories and response category labels. Int. J. Res. Mark. 27, 236–247. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2010.02.004

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Manag. J. 5, 171–180. doi:10.1002/smj.4250050207

Winch, G. M. (2006). Towards a theory of construction as production by projects. Build. Res. Inf. 34, 154–163. doi:10.1080/09613210500491472

Young, D., Haas, C., Goodrum, P., and Caldas, C. (2011). Improving construction supply network visibility by using automated materials locating and tracking technology. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 137, 976–984. doi:10.1061/(asce)co.1943-7862.0000364

Zhang, X. (2005). Critical success factors for public–private partnerships in infrastructure development. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 131, 3–14. doi:10.1061/(asce)0733-9364(2005)131:1(3)

Zhang, X., Liu, T., Rahman, A., and Zhou, L. (2023). Blockchain applications for construction contract management: a systematic literature review. J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 149, 03122011. doi:10.1061/(asce)co.1943-7862.0002428

Keywords: supply chain visibility, information sharing, industrial construction, stakeholder perspectives, construction supply chains

Citation: Dharmapalan V, O’Brien WJ and Morrice D (2025) Benefits of visibility in industrial construction projects: supply chain stakeholders’ perspectives. Front. Built Environ. 11:1698777. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2025.1698777

Received: 04 September 2025; Accepted: 31 October 2025;

Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Rehan Masood, Otago Polytechnic, New ZealandReviewed by:

Muzaffar Iqbal, Dalian Maritime University, ChinaXichen Chen, Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand

Copyright © 2025 Dharmapalan, O’Brien and Morrice. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vineeth Dharmapalan, dmluZWV0aEBoYXdhaWkuZWR1

Vineeth Dharmapalan

Vineeth Dharmapalan William J. O’Brien

William J. O’Brien Douglas Morrice2

Douglas Morrice2