- 1Shandong Electric Power Engineering Consulting Institute Corp., Ltd., Jinan, China

- 2School of Civil Engineering, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China

- 3Tianjin Qiushi Intelligent Technology Corp., Ltd., Tianjin, China

- 4Department of Structural, Geotechnical and Building Engineering, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy

To address the engineering challenge of detecting fine cracks on hybrid wind turbine towers, especially against complex water seepage backgrounds, this study aims to explore optimal image segmentation strategies. The core challenges of this task lie in the severe class imbalance caused by the extremely low pixel ratio of crack targets and the visual interference from seepage areas. To this end, a dedicated dataset for this specific scenario, named HTSCD, was first constructed. Subsequently, based on the U-Net segmentation model, this study systematically compared the effects of various combinations of data processing strategies (original, tiled, tiled and augmented) and loss functions (Cross-Entropy, Weighted Cross-Entropy, Dice Loss). Furthermore, to investigate the potential performance improvement from external data, the effectiveness of transfer learning using public crack datasets and programmatically synthesized data was also evaluated. The experimental results demonstrate that the combination of the tiled and augmentated dataset strategy and the Dice Loss function is the optimal solution for this task, achieving the best balance between precision and recall. A key finding is that conventional transfer learning strategies exhibited significant “negative transfer” in this task, where the introduction of external data impaired model performance. This research not only establishes an effective baseline solution for wind tower crack detection in this specific scenario but also provides important practical insights into the limitations of transfer learning for highly specialized visual inspection tasks.

1 Introduction

With the increasing global demand for renewable energy, wind energy, as a clean and sustainable form of energy, has become increasingly important in strategic terms. Wind turbines, as the core equipment for wind energy conversion, their long-term stable operation is crucial to ensuring energy supply. The tower, as the key structure supporting the huge rotor and nacelle of the wind turbine, its structural health directly affects the safety and service life of the entire wind power generation system. In recent years, to adapt to the development trend of larger single-unit capacity and higher hub height, hybrid towers composed of a concrete structure at the bottom and a steel structure at the top have been widely applied due to their economic and structural advantages (Haar and Marx, 2015).

However, unlike traditional steel towers, the concrete part of hybrid towers is susceptible to the complex influences of various factors such as fatigue loads, temperature changes, and material shrinkage and creep during long-term service, inevitably developing surface cracks, as shown in Figure 1. These cracks are not only defects in the structural appearance but also lead to water seepage, and more importantly, may become potential channels that accelerate the corrosion of internal steel bars and reduce the structural durability. In extreme cases, tiny cracks may continue to expand and converge, developing into structural damage, thereby seriously threatening the overall stability and service safety of the tower. Therefore, regular, efficient, and accurate crack detection and evaluation of hybrid towers are crucial aspects of preventive maintenance and structural health monitoring in wind farms (Civera and Surace, 2022).

Traditional tower crack detection mainly relies on manual high-altitude operations or visual inspections using telescopes. This method is not only inefficient and costly, but also exposes inspectors to significant safety risks. More importantly, the detection results are highly susceptible to factors such as lighting conditions, observation angles, and the subjective judgment of inspectors, making it difficult to ensure the consistency and reliability of the results. In recent years, with the rapid development of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology and computer vision, the use of UAVs equipped with high-definition cameras for image collection, combined with deep learning algorithms for automated crack identification, has become a research hotspot in the field of structural health monitoring (Hu F. et al., 2025; Li et al., 2025; Kaveh and Alhajj, 2024). This technical approach provides a new solution for achieving safe, efficient, and intelligent inspection of wind turbine towers.

In the field of object detection, researchers typically use models such as the YOLO series and Faster R-CNN to locate cracks with bounding boxes. These methods are widely applied in the inspection of various large-scale infrastructure. For example, Hu F. et al. (2025) proposed an improved YOLOv5l model, which realizes the rapid identification of six different types of defects on the surface of wind turbine towers. Similarly, researchers have successfully applied Faster R-CNN to bridge crack detection (Li R. et al., 2023), and achieved efficient detection of tunnel lining cracks based on improved YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 models (Duan et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2024). However, the inherent limitation of object detection methods is that the output rectangular boxes contain a large number of background pixels, making it difficult to accurately quantify key geometric parameters of cracks such as length, width, and direction, which are crucial for evaluating the actual hazard level of cracks.

To achieve more refined crack quantification analysis, image segmentation technology has emerged. Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) represented by U-Net, DeepLabV3+, etc., can realize pixel-level crack mask prediction, providing a solid foundation for subsequent evaluations. For wind tower scenarios, Deng et al. (2024) proposed a customized network based on DeepLabV3+ to address the challenges of data imbalance and background interference. Li et al. (2025) combined attention-enhanced CNN with Structure from Motion (SfM) 3D reconstruction technology, which not only identified subtle cracks but also realized their spatial localization and parameter quantification on 3D models, forming an automated closed-loop system. To further improve segmentation accuracy, researchers have continuously explored better network architectures, such as capturing cracks of different sizes through multi-scale feature fusion (Shang et al., 2020; Zhang J. et al., 2020), improving classic architectures like U-Net++ (Sarhadi et al., 2024), or designing lightweight networks (Li et al., 2024; Depeng and Huabin, 2024) to balance accuracy and efficiency. In recent years, hybrid architectures fusing CNN and Transformer have become a new research hotspot, aiming to combine the powerful local feature extraction capability of CNN and the excellent global context modeling capability of Transformer, thereby more effectively capturing the slender and continuous morphological characteristics of cracks (Zhang et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2023).

Whether it is object detection or image segmentation, the performance of deep learning models is highly dependent on large-scale, high-quality annotated datasets (Zhang M. et al., 2020). In the specific field of wind tower crack detection, it is relatively difficult to obtain sufficient real annotated data. To address the issue of data scarcity, existing studies have mainly explored two strategies. First, transfer learning and domain adaptation. This strategy aims to transfer knowledge learned from data-rich domains (source domains) to target domains with scarce data (Toldo et al., 2020). For example, models pre-trained on large public datasets (such as ImageNet) or related domains (such as ground, dam, and underwater cracks) are transferred to target tasks for fine-tuning (Fan et al., 2022; Li J. et al., 2023; Maray et al., 2023). To further reduce reliance on labeled data, more advanced paradigms such as few-shot learning have been proposed, aiming to enable models to learn to segment new crack categories with only one or a few example images (Chang et al., 2023; Tian et al., 2022). Second is synthetic data generation. This strategy uses computer graphics technology to generate a large number of virtual crack images with precise annotations to expand training data. For example, Xu et al. (2023) and Hu W. et al. (2025) generated a large number of realistic virtual crack images through high-fidelity 3D modeling and rendering technologies, and proved that mixed training with virtual and real data can significantly improve the detection performance of models in complex scenarios. In addition, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are also used to generate or translate images to expand datasets or perform unsupervised feature learning (Majurski et al., 2019). The core of these methods is to solve data quality problems caused by insufficient annotations or label noise (Song et al., 2023), thereby improving the generalization ability of the model.

In summary, although existing research has made significant progress in improving the accuracy and automation of crack detection models, there are still the following research gaps: (1) Most studies (such as Hu F. et al. (2025)) focus on the detection and classification of typical dark-colored cracks under conventional dry backgrounds, while insufficient attention is paid to the more challenging scenario of “light-colored fine cracks under water seepage backgrounds.” Due to their shallow depth and small pixel values, such cracks pose far greater challenges to the refined recognition capabilities of segmentation algorithms compared to conventional scenarios. Additionally, there is currently a lack of public dedicated datasets for this specific scenario. (2) Although strategies such as transfer learning and synthetic data have been widely discussed, the effectiveness of these general data strategies in the aforementioned highly specific scenarios with unique visual characteristics, as well as the potential risks such as “negative transfer,” have not yet been systematically verified and analyzed.

To address the aforementioned research gaps, this paper focuses on the highly challenging detection scenario of “light-colored fine cracks against a water seepage background” on the surface of hybrid tower drums of wind turbines, aiming to explore optimal data strategies and model training schemes. The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

1. Construction of a new dedicated dataset Hybrid Tower Seepage and Crack Dataset (HTSCD): Targeting the unique scenario of “light-colored fine cracks against a water seepage background” on the surface of hybrid tower drums of wind turbines, we built a pixel-level dedicated dataset containing two types of defects, “water seepage” and “cracks”, through on-site collection and detailed manual annotation. This dataset fills the gap of the lack of such samples in existing public datasets and provides a valuable benchmark for subsequent research.

2. Establishment of an effective detection benchmark scheme: By systematically comparing various data preprocessing strategies (such as block division and data augmentation) and loss functions (such as cross-entropy loss and Dice loss), we verified that the combination of “block division + data augmentation” and “Dice loss” is the optimal strategy to solve such severe class imbalance problems, providing a solid performance benchmark for this specific task.

3. Revelation of negative transfer phenomenon in specific scenarios: By introducing public datasets and programmatically generated synthetic data, we comprehensively explored the effectiveness of transfer learning strategies in this task. The experimental results reveal for the first time that in such highly specific tasks, conventional transfer learning strategies have a significant risk of negative transfer, that is, the use of external data may instead impair model performance. This finding has important warning significance and guiding value for the selection of data strategies in future related research.

2 Methodology

2.1 Research strategy and logic

The methodology of this study follows a progressive logic, aiming to systematically address two core challenges: the inherent class imbalance within the dataset and the external limitation of a limited total number of samples. To this end, we designed a two-stage experimental scheme.

Stage 1: Optimizing in-domain training to tackle the “internal challenge”. First, without introducing external data, we explored the optimal training algorithm to solve the problem of inherent data imbalance through comprehensive comparative experiments on loss functions. The experiments systematically compared representative loss functions of different strategies (such as standard cross-entropy, weighted cross-entropy, and Dice loss), aiming to find a method to maximize the potential of the existing data and establish a reliable in-domain performance benchmark.

Stage 2: Introducing external knowledge to challenge the “external limitation”. After establishing the optimal in-domain training scheme, we then explored whether introducing external knowledge could break through the bottleneck of limited sample size through transfer learning experiments. Datasets from different source domains were used for pre-training to verify the effectiveness of external general features in improving the performance of the target domain.

In summary, the two experimental stages form a rigorous successive relationship: the comparative experiments on loss functions provide a reliable performance benchmark for transfer learning, ensuring the validity of the conclusions. This systematic design enables us to clearly analyze the contributions of different strategies and provide strong conclusions for addressing the specific challenges of this study.

2.2 Construction and processing strategy of HTSCD dataset

For the complex scenario where surface cracks and water seepage coexist on the hybrid tower drum, this study first constructed a dedicated hybrid tower crack dataset called the Hybrid Tower Seepage and Crack Dataset (HTSCD). It contains 24 original images with a resolution of 4284

Figure 2. Examples of data processing strategies. (a) Crack and water seepage areas in the original high-resolution image. (b) Crack and water seepage areas in the original high-resolution image. (c) Image patches after rotation augmentation.

The images in the HTSCD dataset have the following significant characteristics: (1) Defect coexistence and class imbalance: The images in the dataset generally contain both cracks and water seepage defects. Among them, the water seepage area accounts for a relatively large proportion in the image, while cracks, as subtle features, account for a small proportion of pixels, with their widths mostly ranging from 2 to 5 pixels, which constitutes a serious class imbalance challenge; (2) Defect correlation: On-site surveys show that water seepage phenomena often originate from internal or external crack defects, so the two types of defects are usually spatially associated. This feature provides the possibility for the model to use the water seepage area as contextual information to infer the existence of cracks; (3) Unique visual appearance: Different from the dry and dark-colored cracks in common crack datasets, the cracks in this dataset mostly exist in wet water seepage areas. Affected by environmental factors such as wind and dust, the fillers inside the cracks make their color show the characteristic of “light-colored cracks” which are brighter than the relatively dark water seepage background, posing new challenges to traditional crack detection algorithms.

U-Net is a robust, well-understood benchmark. Unlike more complex models (e.g., Transformers) which require more data and risk overfitting on small datasets, U-Net’s relative simplicity allows us to clearly isolate and measure the effect of the data strategies themselves. Therefore, In this study, a classic U-Net is adopted as the basic segmentation model architecture, and its structure is shown in Figure 3. We chose U-Net because of its symmetric encoder-decoder structure and core skip connection design, which have been proven to be extremely effective in refined segmentation tasks such as medical images. This structure can well integrate the deep semantic information provided by the encoder with the shallow high-resolution spatial details, thereby achieving accurate positioning of the subtle crack targets in this task. To further enhance the feature extraction capability of the model and utilize the general features learned from large datasets, we use ResNet-34 pre-trained on ImageNet as the encoder backbone of U-Net. The residual connection structure of ResNet effectively solves the problem of gradient vanishing in the training of deep networks and can extract deeper and more robust image features than the original U-Net encoder.

To systematically evaluate different strategies for addressing the class imbalance problem, we designed comprehensive comparative experiments on loss functions. First, we adopted Standard Cross-Entropy (BaselineCE) as a performance benchmark to measure the model’s performance without any class balancing treatment. Subsequently, we selected representative loss functions from two mainstream technical paths for in-depth comparison: (1) Distribution-based weighting strategy: This strategy modifies the cross-entropy loss function by assigning different weights to different classes, forcing the model to focus on minority classes. The specific methods include: 1) Weighted Cross-Entropy (WCE): Using inverse frequency weighting, it is a direct weighted benchmark method; 2) Median Frequency Balanced Cross-Entropy (MedianFreqCE): Adopting a more advanced median frequency balancing strategy, which can more stably assign weights to rare classes. (2) Region-based similarity measurement strategy: This strategy directly optimizes the macro overlap between the predicted region and the real region, and is naturally robust to class imbalance in terms of quantity. Its typical representative is Dice Loss, which is derived from the Dice similarity coefficient and is very suitable for segmentation tasks of tiny objects. By comparing the three optimization strategies with the benchmark, we can clearly quantify the improvement brought by each method and explore the effectiveness of different technical paths.

2.3 Transfer learning strategy

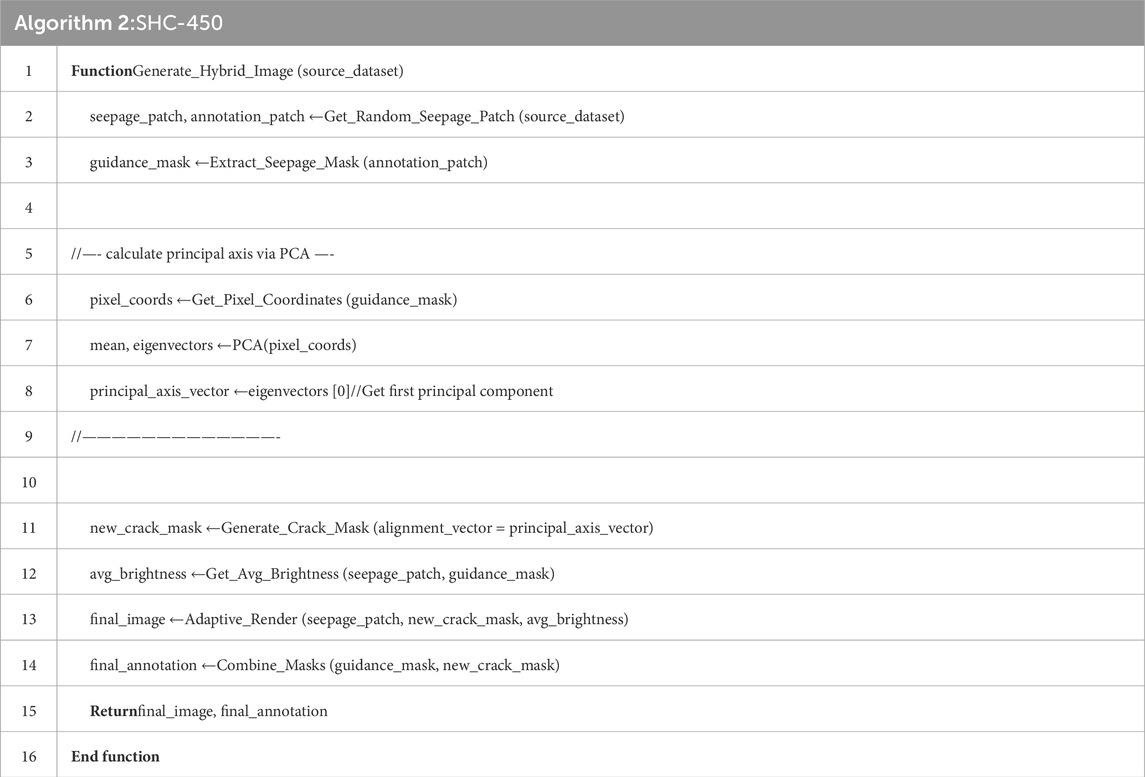

To further enhance model performance, especially to address the challenges posed by the limited sample size and unique features of the HTSCD dataset, this study introduces a transfer learning strategy. The core idea is to help the model better learn general crack features through pre-training on relevant source domain datasets, thereby achieving better performance on the target domain (HTSCD). To this end, we constructed three different types of pre-training datasets to systematically study the impact of domain gap on transfer effectiveness. The source domain pre-training data is shown in Figure 4: (1) Public crack dataset (Public-450): We collected, carefully screened, and re-annotated 450 typical concrete surface crack images from public datasets. This dataset is characterized by cracks that are mostly dark-colored, with a background of dry, non-water-seeping concrete, showing a significant domain gap from the HTSCD dataset; (2) Synthetic Light Crack dataset (SLC-450): To simulate the “light-colored crack” feature in HTSCD, we developed a programmatic generation algorithm. This algorithm first uses Perlin noise to generate subtle crack paths with random distortions and branches, simulating the natural morphology of real cracks. Subsequently, these paths are rendered as light-colored lines and superimposed on a general concrete texture background, ultimately generating light-colored crack images with a non-water-seeping background (the core algorithm pseudocode is shown in Table 1); (3) Synthetic Hybrid Crack dataset (SHC-450): This is the most targeted dataset designed to minimize the domain gap. The algorithm first extracts pure water-seeping area textures from the HTSCD dataset as the background. Then, using the improved crack generation logic based on the algorithm in Table 2, light-colored cracks associated with the seeping areas are intelligently generated within these real water-seeping regions. This generation is guided by the “principal axis direction” of the seepage patch. Specifically, for each seepage mask (guidance_mask), first extract the (x, y) coordinates of all its non-zero pixels. Then apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to this coordinate set. The resulting first principal component (i.e., the eigenvector corresponding to the largest eigenvalue) defines the “principal axis,” which represents the main orientation or elongation direction of the seepage area. The subsequent crack generation algorithm (detailed in Table 2) is then biased to create a crack path that is generally parallel to this axis. This ensures that the synthetic cracks are highly similar to the target domain in terms of color, background texture, and defect symbiosis.

Figure 4. Examples of source domain pre-training datasets. (a) Dark cracks in public-450. (b) Synthetic light-colored cracks in SLC-450. (c) Example of the synthetic dataset SHC-450, associated light-colored cracks generated on a real water seepage background.

3 Experiments and analysis

3.1 Experimental setup

To comprehensively evaluate the impact of different data strategies and loss functions on model performance, we designed twelve experimental scenarios. We trained the model using three datasets of different scales (original dataset, tiled dataset, and tiled + augmented dataset) respectively, and under each dataset configuration, we employed four loss functions (BaselineCE, WCE, MedianFreqCE, and Dice) for training. Dataset Split: To ensure a fair evaluation and strictly prevent data leakage, we first split the dataset at the original image level. The 24 original high-resolution images (HTSCD) were divided into a training set of 18 images and a validation set of 6 images. All subsequent processing (tiling and augmentation) was performed strictly within these respective splits. Due to the limited number of source images, a separate test set was not partitioned. Therefore, all final evaluation metrics reported in this paper, as well as the early stopping criterion, were calculated on this validation set. All experiments adopted the U-Net model with ResNet-34 as the encoder, implemented based on the PyTorch framework and the segmentation-models-pytorch library (Iakubovskii, 2019), and trained on a GPU with CUDA enabled. We used the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate set to 0.0001. To prevent overfitting, we set different maximum training epochs: 300 epochs for the original dataset, and 200 epochs for the tiled dataset and the tiled + augmented dataset. Meanwhile, all training adopted an early stopping strategy: training would be terminated if the overall IoU on the validation set did not improve within 40 epochs. For the tiled and augmented dataset, we used the Albumentations library for data augmentation, including random horizontal flipping, vertical flipping, and 90-degree rotation. All experiments were conducted on a computer with the following configuration: CPU: Intel Core i9-10940X, GPU: NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060, RAM: 32 GB. The software environment was: Win10, Python 3.9, PyTorch 2.7.1 + cu118, CUDA 11.7, segmentation-models-pytorch 0.5.0.

3.2 Results and discussion

To systematically evaluate the performance of different combinations of data strategies and loss functions, we conducted a comprehensive visual analysis of the results from all twelve experimental conditions. We used standard evaluation metrics in semantic segmentation tasks to measure model performance, including Intersection over Union (IoU), Precision, and Recall. In the following discussion, we will focus on analyzing the most representative IoU metric, and detailed data of all metrics under all conditions can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of detailed evaluation metrics for all twelve experimental configurations across different categories.

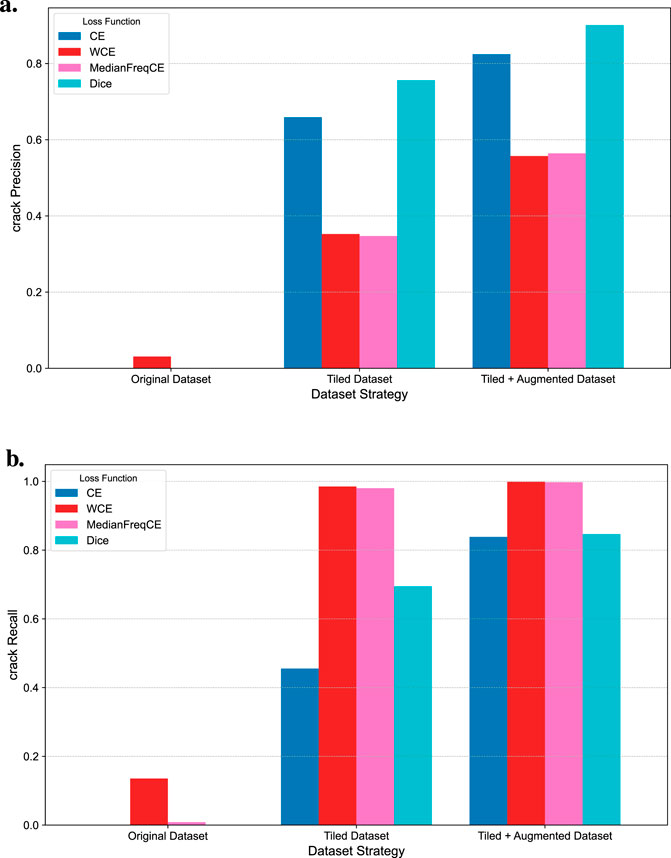

As the category with the lowest pixel proportion and the greatest recognition difficulty, the segmentation accuracy of cracks is the core for measuring model performance. Figure 5a shows the comparison of Intersection over Union (IoU) for the crack category under all working conditions. First, the data processing strategy is the most critical factor affecting performance. The model performance shows a significant stepwise improvement as the dataset progresses from “original” to “block-based”, and then to “block-based + augmentation”. On the original dataset with the smallest amount of data, the performance of all models is unsatisfactory; among them, only the Weighted Cross-Entropy (WCE) has a slight ability to recognize cracks, but its performance is also very poor, while other loss functions completely fail.

When the data strategy was switched to tiled and tiled + augmentated, the performance of all models achieved a qualitative leap. Among these two data strategies, the Dice loss showed the strongest performance, reflecting its advantage in handling fine-grained segmentation tasks. A notable phenomenon is that the performance of the two distribution-weighted strategies (WCE, MedianFreqCE) was not as good as that of the untreated standard cross-entropy (BaselineCE). This indicates that in this task, simple class weighting strategies may instead have negative effects when the amount of data is relatively sufficient. Further observation reveals that on the tiled + augmentated dataset with the most sufficient data, the performance gap between standard cross-entropy and Dice loss has narrowed. This suggests that the standard cross-entropy model relies on a large amount of data to learn features in imbalanced classes and can also achieve good results when the data volume is sufficient. However, the Dice loss demonstrated more stable and superior performance across different data scales.

In contrast to the hard-to-identify crack categories, the segmentation task for seepage areas is relatively simple due to their more distinct features and larger areas. As shown in Figure 5b, using only the tiled dataset strategy, models with all loss functions achieved very high seepage-IoU (generally above 0.8), indicating that the models can easily learn the features of seepage areas. On this basis, further using the tiled + augmentated dataset strategy, although the performance improved slightly, the improvement effect was limited. This result shows that for simple features like seepage, the basic data blocking strategy is sufficient to achieve high recognition accuracy, and the marginal benefit brought by additional data augmentation is not significant.

Figure 6 provides an in-depth comparison of the precision and recall of each model in the crack category. For the latter two dataset strategies (tiled, tiled + augmentated), the trend of precision is highly consistent with IoU, with Dice loss and standard cross-entropy performing better. However, the recall metric presents a completely different picture: the two cross-entropy losses based on distribution weighting (WCE, MedianFreqCE) achieved nearly perfect recall (close to 1.0).

Figure 6. Comparison of precision and recall for the crack category under all experimental conditions. (a) Precision. (b) Recall.

This phenomenon reveals the essential differences in optimization objectives among various loss functions. The weighting strategy significantly increases the penalty for misclassifying minority classes (cracks), forcing the model to become extremely “sensitive” and tend to judge any suspected features as cracks. This strategy successfully “identifies all” almost all real cracks, thereby achieving a very high recall rate. However, its cost is the introduction of a large number of false positives, leading to a significant drop in its precision rate, which is also reflected in the poor overall performance in the IoU metric.

This trade-off between precision and recall highlights two different engineering use cases. On one hand, for tasks aiming for automated quantification and minimizing overall error, the Dice loss (which seeks to maximize regional overlap) provides the best balance. From this perspective, excessive false alarms (like those from WCE) would unnecessarily increase manual review costs. On the other hand, in safety-critical applications like structural monitoring, high recall is a “safety baseline” where the primary goal is to ensure no defect is missed (minimizing false negatives). From this perspective, the WCE model could serve as an excellent “pre-screening tool” or “alarm system.” Its objective is to conservatively flag all potential anomalies for subsequent expert verification. Therefore, the choice of loss function should depend on the specific engineering objective: Dice Loss for balanced assessment, and WCE for conservative pre-screening.

To further explore the dynamic performance of loss functions on the optimal dataset (tiled + augmentated), we plotted the training curves of the validation set’s crack IoU, as shown in Figure 7. The figure clearly demonstrates the differences in training dynamics among various loss functions. The IoU curve of the Dice loss is the most superior; it not only rises the fastest and most stably but also tends to flatten out in the later stages of training, reaching the highest IoU value, showing good convergence. In contrast, although the curve of the standard cross-entropy (BaselineCE) generally shows an upward trend, it exhibits severe oscillations throughout the training process, indicating instability in its training. The curves of the two weighted cross-entropy strategies (WCE, MedianFreqCE), although relatively stable, converge to a low performance level very early, far inferior to the final performance of the Dice loss and standard cross-entropy.

Figure 7. Validation set crack IoU curves of different loss functions on the tiled + augmented dataset.

Based on the comprehensive analysis above regarding IoU, the trade-off between precision and recall, and training convergence, it can be concluded that for the unique “light-colored crack” detection task in this study, the strategy of “tiled + augmentated” combined with the “Dice loss function” for model training is the optimal configuration in practical applications. This combination not only achieves the best performance in core evaluation metrics but, more importantly, effectively balances precision and recall. It can maximize the identification of real cracks while controlling the false positive rate at a low level, which is crucial for reducing subsequent manual review costs and improving the overall efficiency of the automated detection process.

To more intuitively demonstrate the effectiveness of the optimal strategy, we conducted a visual comparison of the segmentation results, as shown in Figure 8. Figure 8a displays the original image containing light-colored cracks, with a complex background texture and weak crack features. Figure 8b is the corresponding ground truth label. Figure 8c shows the prediction results of the baseline model (trained on the original dataset using standard cross-entropy). It can be seen that this model can hardly identify complete cracks, and even the recognition of water seepage is poor, with serious missed detections. In contrast, Figure 8d presents the prediction results of our proposed best model (trained on the tiled + augmented dataset using Dice loss). This model successfully identified most of the cracks, and its predicted mask not only highly matches the real cracks in morphology but also maintains good continuity. This striking contrast strongly proves that the combination of the tiled + augmented data strategy and “Dice loss” can significantly improve the model’s ability to capture subtle cracks in complex backgrounds.

Figure 8. Visual comparison of segmentation results between the best model and the baseline model. (a) Original image. (b) Ground truth. (c) Prediction from the baseline model (original dataset + standard cross-entropy). (d) Prediction from the best model (tiled augmented dataset + dice loss).

4 Transfer learning experiments and analysis

4.1 Experimental setup

To verify the effectiveness of the transfer learning strategy described in Section 2.4, we adopted the standard paradigm of “pre-training - fine-tuning”. For the three pre-training datasets, we used the U-Net model (ResNet-34 encoder) and the Dice loss function for 80 rounds of pre-training. Subsequently, the pre-trained model weights were loaded, and 150 rounds of fine-tuning were performed on the target dataset HTSCD (tiled but not augmented version).

We specifically chose an unenhanced dataset for fine-tuning, mainly based on two considerations: first, this can significantly save computing resources, enabling us to efficiently evaluate and compare the effects of various pre-training strategies; second, it constructs a more rigorous testing environment, aiming to verify whether the features learned from pre-training are robust enough to achieve effective knowledge transfer with limited data in the core target domain.

4.2 Results and discussion

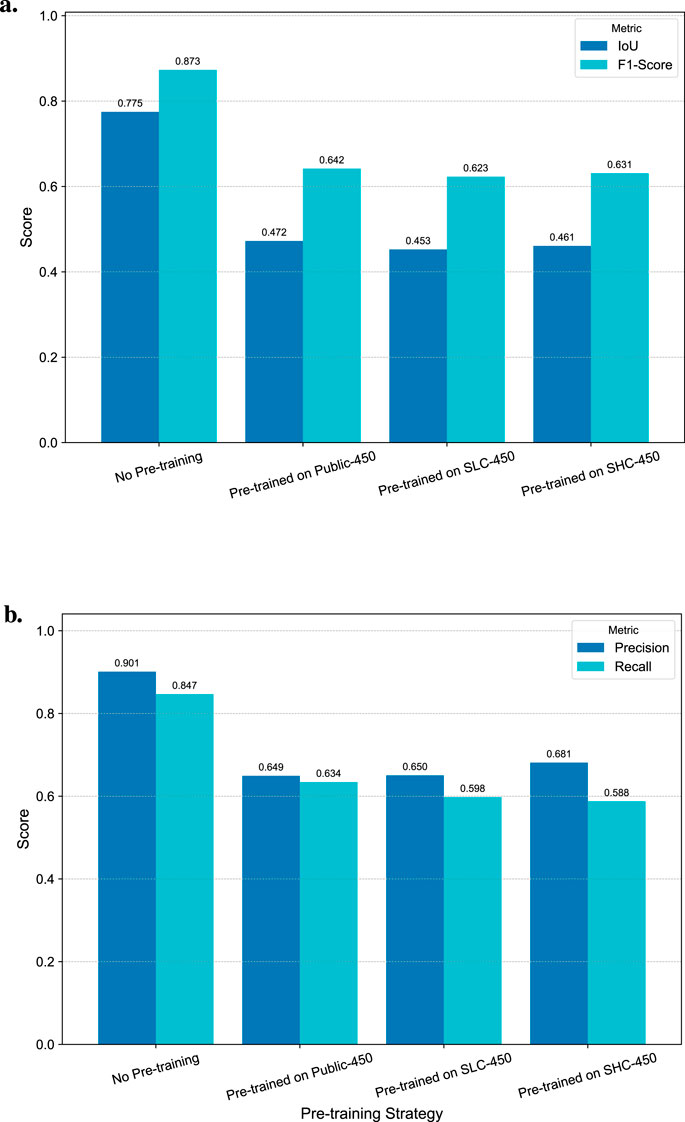

To evaluate the effectiveness of different transfer learning strategies, we conducted a comparison of the results from three pre-training strategies with a baseline model that was trained from scratch on the same tiled and non-augmented dataset.

As shown in Figure 9, the final evaluation results of the transfer learning experiment are contrary to expectations. The baseline model trained from scratch on the unenhanced target dataset in blocks achieved the highest crack IoU. All three pre-training strategies not only failed to bring performance improvements, but their final IoU was even lower than that of the baseline model, indicating that significant “negative transfer” occurred in this task.

Figure 9. Comparison of IoU, F1-Score, precision, and recall for the crack category, contrasting various transfer learning strategies with the baseline model. (a) IoU and F1-score. (b) Precision and recall.

Among the three pre-training strategies, pre-training using the Public-450 public dataset achieved relatively the best results, but still fell short of the baseline. What is more surprising is that the two synthetic datasets (SLC-450 and SHC-450) designed to simulate the characteristics of the target domain performed even worse. Among them, the SHC-450 dataset, which was carefully designed to minimize domain differences, had the worst performance among all strategies.

This series of negative results reveals deep-seated challenges in domain adaptation for this task, likely stemming from two coupled effects. First, a critical limitation is our small fine-tuning dataset (from N = 24 images). The observed performance drop likely includes ‘fine-tuning failure’—where the target data is insufficient to provide effective gradients to adapt the pre-trained model. Second, even beyond the data-scale issue, significant underlying domain gaps are also critical factors: (1) The Public-450 (dark cracks) has vast feature differences; (2) The synthetic data (SLC/SHC) cannot reproduce complex real-world noise; and (3) The real-image textures in Public-450 (despite the domain gap) may still be more robust than ‘pure’ synthetic data. With the current data scale, these two effects, ‘fine-tuning failure’ and ‘true negative transfer’, are difficult to disentangle, which is a key study limitation.

To further verify this conclusion, we also analyzed the performance on the relatively simple ‘seepage’ category, as shown in Figure 10. The results indicate that, similar to the performance on the ‘crack’ category, the baseline model without pre-training achieved the best performance in terms of IoU and F1-Score. All transfer learning strategies led to a slight decline in performance. This result further confirms the core finding of this study: for the highly specific HTSCD dataset, even for relatively easily identifiable features, in-domain training from scratch is superior to the conventional pre-training-fine-tuning paradigm.

Figure 10. Comparison of IoU and F1 scores on the seepage category between different transfer learning strategies and baseline models.

In summary, the transfer learning exploration in this study has drawn an important conclusion: For the segmentation task with highly specific features (light-colored fine cracks in a humid background) in the HTSCD dataset, conventional transfer learning strategies (whether using general public datasets or programmatically synthesized data) are difficult to achieve success. This highlights the necessity of acquiring more high-quality in-domain annotated data for this specific scenario or developing more advanced domain adaptation technologies.

5 Conclusion and limitations

5.1 Conclusion

This study investigated segmentation strategies for fine, light-colored cracks on hybrid wind turbine towers, a task complicated by water seepage and severe class imbalance. Our key conclusions are:

1. Data Strategy is Essential. A ′tiled and augmented’ data strategy was the single most critical factor, proving essential for enabling the model to segment fine cracks from a limited set of original high-resolution images.

2. Dice Loss is Optimal. For this specific class imbalance problem, the Dice loss function provided the best solution, achieving a superior balance between precision and recall compared to standard or weighted cross-entropy methods.

3. Transfer Learning Limitations. Under our specific setup (U-Net and N = 24 dataset), all tested transfer learning strategies (using public or synthetic data) resulted in ‘negative transfer.’ This highlights that for this highly specific, low-data task, in-domain data augmentation was a more effective strategy than the tested pre-training paradigms.

In summary, this study establishes an effective baseline for this task using a U-Net with a ‘tiled + augmented’ data strategy and Dice Loss. Our results provide a key practical insight: for highly specific, low-data visual tasks, robust in-domain data augmentation can be a more reliable strategy than standard transfer learning, which showed negative transfer in our setup.

5.2 Limitations and future work

Although this study has achieved positive results, there are still some limitations that deserve further exploration in future work:

1. Dataset size: The number of original images in this study is limited (24 images). Although the training set has been expanded through data augmentation, larger-scale and more diverse real-scene images will help to further improve the generalization ability and robustness of the model. More importantly, as discussed in Section 4.2, the small sample size introduces ambiguity to the ‘negative transfer’ result (it may be confounded with ‘fine-tuning failure’)

2. Fidelity of synthetic data: The experimental results show that the currently procedurally generated synthetic data are not sufficient to fully simulate the complex image features of the real world. In the future, more advanced generation technologies such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) or diffusion models can be explored to create more realistic in-domain training data.

3. Domain adaptation technology: To address the problem of transfer learning failure, more advanced Domain Adaptation technologies can be studied in the future, aiming to directly reduce the feature distribution difference between the source domain and the target domain, rather than just relying on pre-training.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

ZZ: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. KX: Resources, Writing – review and editing. WJ: Investigation, Software, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. ST: Writing – original draft, Validation. GL: Supervision, Writing – review and editing. JX: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the Project of Research on Safety Intelligent Monitoring and Evaluation of Ultra-high Wind Turbine Steel/Hybrid Tower Tubes (2025GKF-0536) and 111 Project (B20039).

Conflict of interest

Authors ZZ and KX were employed by Shandong Electric Power Engineering Consulting Institute Corp., Ltd.

Author WJ was employed by Tianjin Qiushi Intelligent Technology Corp., Ltd.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author JX declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Chang, Z., Lu, Y., Ran, X., Gao, X., and Wang, X. (2023). Few-shot semantic segmentation: a review on recent approaches. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 18251–18275. doi:10.1007/s00521-023-08758-9

Chen, X., Li, D., Liu, M., and Jia, J. (2023). CNN and transformer fusion for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. Remote Sens. 15, 4455. doi:10.3390/rs15184455

Civera, M., and Surace, C. (2022). Non-destructive techniques for the condition and structural health monitoring of wind turbines: a literature review of the last 20 years. Sensors Basel, Switz. 22, 1627. doi:10.3390/s22041627

Deng, J., Hua, L., Lu, Y., Song, Y., Singh, A., Che, J., et al. (2024). Crack analysis of tall concrete wind towers using an ad-hoc deep multiscale encoder-decoder with depth separable convolutions under severely imbalanced data. Struct. Health Monit. 24, 3561–3579. doi:10.1177/14759217241271000

Depeng, W., and Huabin, W. (2024). MFFLNet: lightweight semantic segmentation network based on multi-scale feature fusion. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83, 30073–30093. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-16782-z

Duan, S., Zhang, M., Qiu, S., Xiong, J., Zhang, H., Li, C., et al. (2024). Tunnel lining crack detection model based on improved YOLOv5. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 147, 105713. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2024.105713

Fan, X., Cao, P., Shi, P., Chen, X., Zhou, X., and Gong, Q. (2022). An underwater dam crack image segmentation method based on multi-level adversarial transfer learning. Neurocomputing 505, 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.07.036

Haar, C., and Marx, S. (2015). Design aspects of concrete towers for wind turbines. J. South Afr. Institution Civ. Eng. 57, 30–37. doi:10.17159/2309-8775

Hu, F., Leng, X., Ma, C., Sun, G., Wang, D., Liu, D., et al. (2025). Wind turbine surface crack detection based on YOLOv5l-GCB. Energies 18, 2775. doi:10.3390/en18112775

Hu, W., Liu, X., Zhou, Z., Wang, W., Wu, Z., and Chen, Z. (2025). Robust crack detection in complex slab track scenarios using STC-YOLO and synthetic data with highly simulated modeling. Automation Constr. 175, 106219. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2025.106219

Iakubovskii, P. (2019). Segmentation models pytorch. Available online at: https://github.com/qubvel/segmentation_models.pytorch.

Kaveh, H., and Alhajj, R. (2024). Recent advances in crack detection technologies for structures: a survey of 2022-2023 literature. Front. Built Environ. 10, 1321634. doi:10.3389/fbuil.2024.1321634

Li, J., Lu, X., Zhang, P., and Li, Q. (2023). Intelligent detection method for concrete dam surface cracks based on two-stage transfer learning. Water 15, 2082. doi:10.3390/w15112082

Li, R., Yu, J., Li, F., Yang, R., Wang, Y., and Peng, Z. (2023). Automatic bridge crack detection using unmanned aerial vehicle and faster R-CNN. Constr. Build. Mater. 362, 129659. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129659

Li, B., Chu, X., Lin, F., Wu, F., Jin, S., and Zhang, K. (2024). A highly efficient tunnel lining crack detection model based on mini-unet. Sci. Rep. 14, 28234. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-79919-6

Li, B.-L., Feng, C.-Q., Wei, S.-H., and Liu, Y.-F. (2025). Concrete wind turbine tower crack assessment based on drone imaging using computer vision and artificial intelligence. Adv. Struct. Eng. 28, 3121–3140. doi:10.1177/13694332251344664

Majurski, M., Manescu, P., Padi, S., Schaub, N., Hotaling, N., Simon, C., et al. (2019). “Cell image segmentation using generative adversarial networks, transfer learning, and augmentations,” in 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16-17 June 2019 (IEEE), 1114–1122.

Maray, N., Ngu, A. H., Ni, J., Debnath, M., and Wang, L. (2023). Transfer learning on small datasets for improved fall detection. Sensors 23, 1105. doi:10.3390/s23031105

Sarhadi, A., Ravanshadnia, M., Monirabbasi, A., and Ghanbari, M. (2024). Using an improved u-net++ with a t-max-avg-pooling layer as a rapid approach for concrete crack detection. Front. Built Environ. 10, 1485774. doi:10.3389/fbuil.2024.1485774

Shang, R., Zhang, J., Jiao, L., Li, Y., Marturi, N., and Stolkin, R. (2020). Multi-scale adaptive feature fusion network for semantic segmentation in remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 12, 872. doi:10.3390/rs12050872

Song, H., Kim, M., Park, D., Shin, Y., and Lee, J.-G. (2023). Learning from noisy labels with deep neural networks: a survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 34, 8135–8153. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3152527

Tian, Z., Lai, X., Jiang, L., Liu, S., Shu, M., Zhao, H., et al. (2022). “Generalized few-shot semantic segmentation,” in 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA (IEEE), 11553–11562.

Toldo, M., Maracani, A., Michieli, U., and Zanuttigh, P. (2020). Unsupervised domain adaptation in semantic segmentation: a review. Technologies 8, 35. doi:10.3390/technologies8020035

Xu, J., Yuan, C., Gu, J., Liu, J., An, J., and Kong, Q. (2023). Innovative synthetic data augmentation for dam crack detection, segmentation, and quantification. Struct. Health Monit. 22, 2402–2426. doi:10.1177/14759217221122318

Xu, H., Wang, M., Liu, C., Li, F., and Xie, C. (2024). Automatic detection of tunnel lining crack based on mobile image acquisition system and deep learning ensemble model. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 154, 106124. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2024.106124

Zhang, J., Lin, S., Ding, L., and Bruzzone, L. (2020). Multi-scale context aggregation for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 12, 701. doi:10.3390/rs12040701

Zhang, M., Zhou, Y., Zhao, J., Man, Y., Liu, B., and Yao, R. (2020). A survey of semi- and weakly supervised semantic segmentation of images. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53, 4259–4288. doi:10.1007/s10462-019-09792-7

Zhang, E., Shao, L., and Wang, Y. (2023). Unifying transformer and convolution for dam crack detection. Automation Constr. 147, 104712. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104712

Keywords: class imbalance, crack segmentation, hybrid tower, loss functions, negative transfer, structural health monitoring, wind turbine

Citation: Zhang Z, Xing K, Jiang W, Tang S, Lacidogna G and Xu J (2025) Study on segmentation of fine cracks with water seepage on hybrid towers of wind turbines. Front. Built Environ. 11:1723943. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2025.1723943

Received: 13 October 2025; Accepted: 30 November 2025;

Published: 19 December 2025.

Edited by:

Yong Huang, Harbin Institute of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Qiang Chen, Southeast University, ChinaKun Wu, Civil Aviation University of China, China

Yang Yu, Western Sydney University, Australia

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Xing, Jiang, Tang, Lacidogna and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jie Xu, anh1QHRqdS5lZHUuY24=

Zhenli Zhang1

Zhenli Zhang1 Giuseppe Lacidogna

Giuseppe Lacidogna Jie Xu

Jie Xu