- 1Department of Urban Planning, School of Architecture, Southeast University, Nanjing, China

- 2Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 3Architecture College, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China

- 4Department of Urban Planning, School of Architecture, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

Research increasingly links the built environment to place attachment, with expected benefits for perceived restorativeness and resident wellbeing. Yet prior work has concentrated on macro scale attributes and provides limited evidence on how objective and perceived environments shape attachment at the micro scale of the streetscape. Few studies separate their effects or test whether residents’ emotion mediates these links. This study tests mediation between objective and perceived streetscape characteristics and place attachment and clarifies their roles in theory. We assess the distinct contributions of physical features and subjective appraisals at a unified human scale. We further examine heterogeneity by residence duration and age. The empirical design combines semantic segmentation of street level imagery with survey responses from 797 residents in Nanjing. We estimate a partial least squares structural equation model and conduct multigroup analysis to evaluate mediation and differences across groups. Results reveal that natural environment is positively related to place attachment only through emotion, with significant standardized indirect effects of 0.025** and 0.019**. The artificial environment is negatively related through both pathways, with a direct effect on place dependence of −0.203*** and an indirect effect of −0.044***. The perceived built environment shows the strongest association with attachment, with total standardized effects of 0.595*** for dependence and 0.623*** for identity. Heterogeneity analysis indicates that the attachment preferences of medium-term residents gradually shift towards the natural environment, while older adults exhibit reduced sensitivity to artificial environmental factors. Together, the findings advance micro scale attachment research and inform design that fosters belonging and wellbeing.

1 Introduction

Urban systems are shaped by globalization, cultural homogenization, and environmental volatility. These forces weaken connections between people and places and have prompted sustained inquiry across human geography, environmental psychology, and urban planning (Bonaiuto et al., 2003; Low and Altman, 1992; Relph, 1976). Within this body of work, place attachment has become a central construct that captures the emotional bond people form with particular settings and the accompanying sense of belonging to community and locale (Lewicka, 2011; Scannell and Gifford, 2010). Although intangible, place attachment functions as a valuable public good and is consistently linked to higher quality of life, greater life satisfaction, pro-environmental behavior, and broader wellbeing (Scannell and Gifford, 2017). A clear, evidence-based understanding of how to create and sustain environments that nurture strong attachment is therefore essential for urban development aimed at improving quality of life and supporting social diversity (Escolà-Gascón et al., 2023).

Recent scholarship has concentrated on delineating the determinants of place attachment and clarifying the pathways through which these determinants act together to shape it. Much of this work foregrounds sociodemographic attributes, such as length of residence and age, which has limited systematic inquiry into how the built environment contributes to attachment (Chishima et al., 2023). In the tripartite framework proposed by Scannell and Gifford (2010), the dimension of place is especially salient and is commonly differentiated into physical and social components, a distinction also emphasized by (Hidalgo and Hernández, 2001). Early studies gave primary weight to social milieu and community ties when explaining attachment (Raymond et al., 2010). More recent evidence indicates that physical attributes of place often exert stronger effects on attachment formation and maintenance (Li et al., 2019). Empirical efforts to identify objective predictors of the built environment have largely relied on macro scale measures, such as the normalized difference vegetation index, floor area ratio, and neighborhood density (Mouratidis and Poortinga, 2020). This emphasis tends to underrepresent exposures at the human scale that directly structure everyday experience, including the streetscape features encountered by pedestrians, the level of visual complexity, and micro spatial proportions that structure everyday experience in the built environment (Ewing and Handy, 2009). Furthermore, the objective built environment comprises distinct natural (e.g., vegetation, terrain, sky) and artificial (e.g., buildings, roads, vehicles) elements, each potentially contributing differently to place attachment (Sander et al., 2025). Although environmental measurement has advanced through photographic audits and expert evaluations (Li et al., 2019), current studies still do not clearly separate the distinct effects of natural and artificial elements or identify where these effects may conflict. They also fall short of capturing, in an objective and fine-grained way, the subtle perceptual qualities that emerge from micro-scale interactions in everyday settings, such as the interplay among vegetation, sky view, building massing, and street furniture, and the resulting impressions of enclosure, coherence, and visual complexity.

Second, existing theoretical accounts still fall short of a comprehensive explanation of the mechanisms through which environmental attributes cultivate place attachment, particularly when considering the potentially conflicting influences of objective environmental characteristics versus individuals’ subjective perceptions, and the crucial mediating role of emotional responses. Although substantial evidence links objective attributes of the built environment—such as the abundance of urban greenery, building scale, and distinctive landscape features—to levels of place attachment (Escolà-Gascón et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2020), much of this literature gives limited attention to the pronounced individual heterogeneity in environmental appraisals (Campbell et al., 1976). Manzo (2005) argues that experience-in-place carries greater weight than the place itself, which implies that neither objective indicators nor subjective perceptions, taken in isolation, can provide a complete account. An integrated approach that examines potential conflicts between subjective perceptions and objective realities is therefore essential for a more robust prediction of place attachment development (Chan and Li, 2022). In addition, environmental psychologists acknowledge the strong association between emotions and place attachment (Scannell and Gifford, 2010). Emotions are frequently theorized as either a constitutive subdimension of attachment or an antecedent state that enables its formation (Halpenny, 2010; Hosany et al., 2016). From this perspective, residents’ emotion translate otherwise static environmental properties into experiences with clear psychological meaning (Ariannia et al., 2024). Yet the specific pathways through which attributes of the built environment, both objective and subjectively perceived, elicit emotional reactions and then initiate, reinforce, or redirect place attachment remain only partly specified. This gap is substantive and requires focused empirical investigation.

Third, place attachment operates as a dynamic human response that varies across individuals and contexts (Lewicka, 2011). Long-term residents and short-stay tourists tend to emphasize different facets of attachment, engaging distinct cognitive and behavioral pathways (Li et al., 2023). Evidence also shows that the functional dimension of attachment exhibits a stronger association with permanent residents than with temporary visitors (Wu et al., 2019). In addition, community facilities and everyday amenities predict attachment more effectively among older adults than among younger cohorts (Sun et al., 2020). These patterns indicate that age and residential tenure may condition how people translate environmental features into attachment. There is a clear need to test whether such differences alter the strength or form of place attachment across specific environmental characteristics, so that planning and policy can be targeted to groups with distinct needs. However, empirical work that explicitly models sociodemographic heterogeneity in the link between the built environment and place attachment remains scarce. Clarifying these differential effects is essential for designing equitable urban interventions that meet the varied needs of residents across groups defined by age, residential tenure, and other social characteristics.

To address these gaps, we apply computer vision to extract micro scale, pedestrian level streetscape metrics and combine them with multidimensional survey data from 797 residents in Nanjing. We then build and evaluate a mediation model that estimates the differential effects of objective and perceived built environments on place attachment, with place related residents’ emotion as the principal mediating mechanism. Mediation paths are evaluated with partial least squares structural equation modeling. Heterogeneity is examined with multi group analysis stratified by length of residence and age. The study has three objectives. (1) Quantify the distinct contributions of objective and perceived built environments to place attachment. (2) Clarify the mediating role of place related residents’ emotion. (3) Examine how environmental sensitivities vary across groups defined by residence duration and age. The results deepen understanding of place attachment and offer practical guidance for policymakers seeking to design context-responsive urban environments.

2 Literature review

2.1 Place attachment

Place attachment is typically understood as an emotion tie or positive bond that links an individual to a particular setting (Hidalgo and Hernández, 2001). Most scholarship conceptualizes it as a multidimensional construct that encompasses emotional, cognitive, and functional facets, rather than a single, unitary trait (Arbab, 2023; Low and Altman, 1992). Scholars from different disciplines have proposed alternative conceptualizations of place attachment, with models ranging from a single factor to four distinct dimensions (Bonaiuto et al., 2003). In environmental psychology, the most widely adopted approach specifies two components (place dependence and place identity) and extensive empirical work shows that this structure is reliable and generalizable across studies (Raymond et al., 2010). Place dependence captures the functional fit between a setting and an individual’s goals and activities, emphasizing how the setting’s resources and opportunities support goal attainment and routine pursuits (Jorgensen and Stedman, 2006). Place identity denotes the emotional and symbolic connections individuals develop with a particular setting, and it is widely viewed as the cognitive facet of place attachment that reflects the meanings and values attributed to the environment (Peng et al., 2020). Extensive empirical work across diverse cultural and geographic contexts supports this two-dimensional model, with substantial evidence from Chinese settings that affirms its reliability for analyzing human–place relationships (Boley et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2021).

Extending this two-component view, we highlight the asymmetry between objective and perceived environments and its implications for place attachment. Objective conditions provide resources and constraints, while attachment arises through appraisals and meanings (Lewicka, 2011). Because perception is shaped by attention, experience, and social context, it may diverge from audited physical qualities (Nia et al., 2017). This asymmetry implies a moderation mechanism. Residents’ emotion and attachment relate to objective features and to perceived quality on their own, yet their strength depends on the congruence between the two. When perceived quality aligns with objective provision, positive affect is reinforced and the links to place identity and dependence become stronger (Amen et al., 2023). When they diverge, as when objectively green areas are perceived as unsafe, affect may be ambivalent or negative and the association with attachment weakens despite favorable physical attributes (Taylor, 2016; Von Wirth et al., 2014). This formulation converts the proposed “conflict” into a testable prediction that congruence between objective and perceived environments conditions the pathways from setting to affect and from affect to attachment (Aziz Amen and Nia, 2018).

In addition, existing research indicates that the process of place attachment is shaped by both social context and individual characteristics, including cultural background and life stage, which together can give rise to significant heterogeneity in the ways people develop and sustain attachment to place (Guo J et al., 2024). In China, traditional society was historically rooted in an agrarian context characterized by low population mobility and a strong emphasis on neighborhood relationships (Fei et al., 1992). This social fabric is aptly captured by the traditional proverb, “A close neighbor is better than a distant relative,” which underscores a profound sense of collective responsibility and strong interdependence. By contrast, the post-reform era in China has witnessed rapid urbanization, resulting in urban landscapes marked by high-rise apartment buildings, gated communities, and an architectural and planning ethos that prioritizes efficiency over communal interaction. Such changes have the potential to erode the traditional ideals of social cohesion and close-knit communities (Lu et al., 2018). This context, therefore, provides a critical lens for interpreting the formation of place attachment within the built environment. The potentially negative impact of the contemporary urban environment on place attachment may not only reflect the disruptive capacity of these physical changes but could also reveal a deeper cultural dissonance. On the other hand, place attachment in China is not a static phenomenon; rather, it is dynamically shaped by the unique formative experiences and evolving values of different generational cohorts. The societal shift from a predominantly collectivist value system toward a more individualistic one represents a major trend in contemporary China (Sun and Wang, 2010). This transformation has profound implications for how each generation perceives and interacts with its environment.

2.2 Objective (natural vs. artificial) built environment and place attachment

Although scholarship has traditionally emphasized social determinants of place attachment, accumulating evidence indicates that physical attributes of the environment exert a substantial influence as well (Lewicka, 2011). Empirical evidence shows that the material form and design of urban environments can either promote or constrain residents’ development of place attachment (Escolà-Gascón et al., 2023). The objective built environment can be divided into natural and artificial environment, and different physical environments have different effects on place attachment and mental health (Zhu et al., 2023). Natural environment, such as vegetation and sky, are frequently linked to positive psychological outcomes, including stress reduction, attention restoration, and enhanced mental wellbeing (Ancora et al., 2022). Stress reduction theory and attention restoration theory suggest an inherent human affinity for natural elements, which can foster positive perceptions and emotional connections, thereby strengthening place attachment (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989; Ulrich, 1993; Wilson and Kellert, 1993). The impact of the artificial environment on psychological wellbeing and attachment is more complex. Well-designed artificial elements and convenient urban facilities can provide functionality, aesthetic pleasure, and opportunities for social interaction, thereby promoting the formation of local attachment (Li et al., 2021). Conversely, poorly designed or overwhelming artificial environments may induce stress, alienation, or negative perceptions, potentially undermining place attachment (Ancora et al., 2022). Taken together, prior work indicates a clear need for hypothesis-driven tests that assess how concrete features of the built environment interact with psychological processes to shape place attachment. Accordingly, we advance our first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1a. Natural environment is positively correlated to place attachment.

Hypothesis 1b. Artificial environment is negatively correlated to place attachment.

2.3 Perceived built environment and place attachment

A substantial body of research documents a consistent gap between objective indicators of the environment and residents’ subjective appraisals (Guo et al., 2021). Objective and perceived measures often capture different facets of the same setting (Orstad et al., 2016). Insights from biological vision show that the human visual system receives external stimuli, transforms them, and interprets them to construct environmental perceptions (Cao et al., 2025). This processing is filtered through prior experience, expectations, and personal values, which leads individuals to evaluate identical physical inputs in different ways (Arbab et al., 2018; Scannell and Gifford, 2010). As a result, the same physical configuration, such as an identical proportion of vegetation pixels in a streetscape image, can evoke contrasting judgments like calmness or boredom (Ogawa et al., 2024). Much of the empirical literature that links place attachment to the built environment relies on perceived conditions, and it identifies factors such as neighborhood satisfaction (Bottini, 2023), fear of crime (Brown et al., 2003), perceived neighborhood walkability (Koohsari et al., 2023), and perceived housing conditions (Chang et al., 2023) as antecedents of attachment formation. These perceived qualities contribute to an individual’s overall experience of a place, thereby imbuing a physical space with meaning and emotional significance, and thus transforming it into a “place” to which one can become attached. Accordingly, we contend that residents’ perceptions of the built environment function as a proximal antecedent to place attachment, shaping both its emergence and its strength. Building on this premise, we advance our second hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2. A more favorable perception of the built environment is positively correlated with place attachment.

2.4 Residents’ emotion as a mediating mechanism linking objective and perceived built environments to place attachment

Research on the relationship between the built environment and public emotion can be traced to the 1960s. Lynch (1964) proposed the concept of mental maps to describe how people structure and interpret urban form. Later work in emotional geographies characterizes subjective experience of place as an emotion perception that is not inherently positive or negative and that emerges from ongoing transactions between the self and the surrounding world (Davidson and Milligan, 2004). As human activities reshape urban settings, these material changes feed back into residents’ emotion states and collective mood (Yang et al., 2022). Research demonstrates that exposure to different environmental stimuli elicits varied emotional states. Empirical studies show that contact with natural settings, especially places with higher tree canopy, is associated with more positive affect (Xiang et al., 2021). In contrast, heavily engineered environments such as transport terminals and industrial production areas are consistently linked to more negative emotional responses (Cao et al., 2018). Similarly, perceived noise and dirtiness are negatively correlated with positive emotions (Yang et al., 2022). This indicates that an individual perceives their surroundings directly shapes their emotional experience within that space (Yang et al., 2024).

Prior research points to a close alignment between residents’ emotion to place and the construct of place attachment (Manzo, 2003). At the same time, a complementary line of work argues that affect arises earlier in the causal chain, with emotional responses to settings functioning as antecedents that enable the development of attachment (Hosany et al., 2016). Empirical evidence indicates that positive feelings toward a place strengthen attachment and promote richer interactions between people and that setting (Morgan, 2010). By contrast, negative feelings are linked to weaker bonds with the place and a lower likelihood that attachment will be sustained (Hosany et al., 2016). Emotions, as residents’ emotion induced by people, events, or surroundings, can be triggered by sensory experiences of a place and may change and solidify over time, ultimately fostering place attachment (Morgan, 2010). Thus, emotion serves as a crucial psychological mechanism translating environmental inputs into the emotion bonds characteristic of place attachment.

Psychological research typically examines emotion through two complementary lenses. The categorical approach treats emotions as discrete states and is often operationalized with measures of positive affect and negative affect (Watson et al., 1988). The dimensional approach represents emotion along continuous axes of pleasure, arousal, and dominance, commonly referred to as PAD (Mehrabian and Russell, 1974). When people encounter physical settings, their internal arousal can shift toward states such as fascination or excitement, which strengthens engagement with the environment (Morgan, 2010). Building on appraisal theory and the stimulus–organism–response perspective, environmental cognitions are first appraised for relevance and control, which elicits affect that guides approach or avoidance (Vieira, 2013). Positive affect broadens attention and facilitates memory and meaning making, increasing repeated use and social interaction, which consolidates identity and dependence (Morgan, 2010). In this sense affect acts as a catalyst that converts evaluations of objective and perceived qualities into enduring attachment. If that engagement is experienced as positive, pleasurable feelings tend to recur and durable emotional bonds with the place are more likely to form (Morgan, 2010). Crucially, these emotional pathways are not solely triggered by objective built environment, an individual’s subjective perception of the built environment also elicits distinct residents’ emotion (Liu et al., 2024). These positive perceptions contribute significantly to the development and strengthening of place attachment. Building on the preceding discussion, we advance the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 3. Residents’ emotion serves as a mediating mechanism linking the objective built environment to place attachment.

Hypothesis 4. Residents’ emotion serves as a mediating mechanism linking the perceived built environment to place attachment.

2.5 Heterogeneous effects

Evidence on the influence of the built environment indicates systematic differences by length of residence and age (Li et al., 2023). Long-term residents often display stronger attachment to local physical features (Liu et al., 2020), and higher perceived garden quality is associated with greater neighborhood attachment among older adults (Guo Y et al., 2024). These patterns suggest that sociodemographic context conditions how environmental attributes and perceptions translate into attachment. Hence the effects of objective and perceived built environment, as well as emotional responses, are unlikely to be uniform across age cohorts or residence-duration groups.

Hypothesis 5. The effects of built environment elements on place attachment vary across groups defined by length of residence and age.

Based on the above findings, we ground the study in two complementary frameworks. The first is the tripartite model of place attachment, which organizes the construct into person, psychological process, and place (Scannell and Gifford, 2010). Objective built environment features fall within the place dimension. Perceived environmental qualities and residents’ emotion belong to the process dimension that links settings to attachment. The second framework is the stimulus–organism–response perspective (Vieira, 2013). In this view, objective attributes act as stimuli that shape cognitive appraisals and emotion reactions in the organism, which then manifest as attachment to place as the response. This mapping provides the conceptual basis for our hypotheses. Accordingly, we test an integrative framework in which place-related residents’ emotion mediates the effects of both objective and perceived built-environment features on place attachment (Figure 1).

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study area

Our study is set in Nanjing, China, a historic city whose cultural legacy extends for more than two millennia. The study area is a heritage-rich setting rather than a generic urban space, where layered history provides a strong basis for place attachment. We focus on two emblematic districts, the Confucius Temple precinct and East Zhonghua Gate, which together cover 2.82 square kilometers (Figure 2). The Confucius Temple, originally established during the Eastern Jin Dynasty, has served as a continuous center for Confucian worship and education, notably housing the largest imperial examination hall in ancient China. For nearly a thousand years, it has also been an important hub of commerce and remains a vibrant cultural and commercial center to this day. Integrating elements of Confucianism, urban street life, and folk customs, the area is home to nationally recognized intangible cultural heritage, such as the Qinhuai Lantern Festival, and holds significant symbolic value (Xue et al., 2025). The Zhonghua Gate, constructed during the Ming Dynasty, represents a monumental achievement in defensive architecture and is acclaimed as the world’s most complex and best-preserved castle-style gate. It stands as an enduring symbol of Nanjing’s imperial legacy and engineering ingenuity. These districts are noted for well preserved traditional Nanjing architecture and a human scale urban fabric. They are often described as living fossils of the city’s history and they continue to serve as important residential neighborhoods for local residents (Yuan et al., 2016).

3.2 Study design

3.2.1 Research flow

To examine how the built environment relates to place attachment, we implemented a three-stage design. (1) We collected pedestrian-view photographs for all public streets and open spaces in the study area with a DJI Osmo Action 3. The camera was fixed at eye level with a 125° field of view and a shooting height of 1.7 m. The images were processed with computer-vision methods to extract micro-scale environmental elements. (2) We administered an image-based questionnaire to measure place attachment, perceived built environment, residents’ emotion, and socio-demographic attributes. Respondents were residents living within 500 m of the study area, a buffer commonly used to capture environmental effects on perception and behavior (Sun et al., 2020). (3) We constructed indicators of the objective built environment from the image measures and modeled their associations with place attachment, while testing the mediating and heterogeneous pathways specified in the introduction and addressing the gaps identified there.

3.2.2 Procedure

Photograph collection points were placed at all street intersections and at 50 m intervals between intersections. At each point we photographed in four compass directions: east, south, west, and north. The final layout comprised 326 collection points and yielded 1,304 photographs (Figure 2). To ensure full spatial coverage, we used neighborhood-level stratified random sampling. Data collection spanned multiple daytime periods on both weekdays and weekends to capture user variability.

Participants were recruited in the field following two a priori eligibility rules. Individuals had to have lived within 500 m of the study area for at least 1 year, which minimized tourist responses and ensured sufficient local experience (Cheng and Kuo, 2015). They also had to be 18 years or older.

Three bilingual authors verified the accuracy of the English to Chinese translation for all questionnaire items, then reconciled wording through discussion. Authors also conducted the fieldwork. On site, the team approached potential respondents individually and explained the study. After consent and eligibility confirmation, participants received a paper questionnaire with written instructions.

Each participant evaluated one photograph only. Photographs were assigned using a pre generated randomization list within neighborhood strata. Each photograph was eligible to be evaluated by up to three different residents. The team tracked counts to enforce this cap. An image was shown for a 30 s observation period, after which the respondent completed items on residents’ emotion, perceived built environment, and place attachment in that order.

Image collection and the survey were conducted from June to July 2024. We distributed 852 questionnaires and obtained 797 valid responses, a 93.5% response rate. For environment level modeling we retained the subset of photographs that had complete computer vision measures and sufficient resident evaluations. This yielded 312 environments used in the structural analysis.

3.3 Measures

3.3.1 Semantic segmentation measurement

Objective elements of the built environment were derived from the pedestrian-view photographs using a combination of semantic segmentation and manual measurement, with an emphasis on micro-scale visual components (Table 1). We applied the DeepLabV3+ model to segment each image into the following classes: road, building, vegetation, terrain, sky, people, motor vehicles, and two-wheelers. Prior studies identify these classes as informative indicators of the objective built environment relevant to human perception and behavior (Ewing and Handy, 2009; Huang et al., 2024). DeepLabV3+ performs accurately and efficiently in urban scene parsing (Qi et al., 2023). Beyond semantic segmentation, we quantify visual complexity as the count of distinct landscape elements in each image (Tveit et al., 2006). Higher scores indicate a more complex and visually stimulating setting.

3.3.2 Questionnaire measurement

Place attachment was measured with a twelve item scale grounded in 2 decades of measurement research (Raymond et al., 2010). The instrument contains two dimensions, place identity and place dependence, with six items for each. Perceived built environment was assessed with a nine item questionnaire adapted from prior studies of urban environmental quality (Ogawa et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2018). The instrument contains nine items that cover key attributes, including liveliness, beauty, wealthiness, greenness, neatness, safety, and walkability (Bonaiuto et al., 2003). All items used a five point Likert scale from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree. Higher scores indicate stronger attachment or more favorable perceptions.

Residents’ emotion was captured with the Self Assessment Manikin, a validated non verbal pictorial tool that records three dimensions: valence from unhappy to happy, arousal from calm to excited, and dominance as perceived control over the situation (Bradley and Lang, 1994; Xiang et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2024).

3.4 Statistical analysis

We analyzed the relationships among variables using partial least squares structural equation modeling at the environment level. Individual responses were aggregated to image level means and each image was treated as one observation. We selected partial least squares because the model contains multiple blocks and mediating paths, the indicators depart from normality, and the effective sample size is determined by the number of environments rather than respondents (Hair et al., 2011). Analyses were conducted in SmartPLS 4.0. We first evaluated item reliability and both convergent and discriminant validity for the measurement models. We then estimated the structural model linking objective built environment, perceived built environment, residents’ emotion, and place attachment, including tests of mediation. Finally, we performed multi-group analysis to examine differences across residence-duration groups and age groups. For inference we used the nonparametric bootstrap with images as the resampling units. This procedure reflects between environment uncertainty but does not propagate the additional sampling error from one to three raters per image.

4 Results

4.1 General characteristics of the participants

A total of 797 residents completed the questionnaire anonymously and voluntarily. The sample includes 400 men and 397 women. Ages range from 18 years to 65 years or older, and most respondents, 72.1 percent, are between 18 and 44 years. Length of residence near the study area varies widely, from less than 10 years to more than 30 years. Nearly half of the sample, 49.2 percent, report living in the area between 10 and 29 years. Detailed socio-demographic characteristics are provided in Table 2.

4.2 Descriptive statistics

Table 3 reports descriptive statistics for individual-level and environmental variables. At the individual level, walkability is the only perceived built environment item with a mean clearly above the scale midpoint (95% CI 3.01–3.16). Safety (2.58–2.73) lie just below the midpoint, and greenness is lowest at 1.78–1.91. For residents’ emotion, valence centers around the midpoint (2.97–3.13), whereas arousal (2.39–2.58) and dominance (2.00–2.20) are lower. Place attachment shows narrow intervals near 12 for both dependence (11.72–12.77) and identity (11.90–12.94). At the environmental level with 312 images, buildings account for the largest share of pixels (30.94–34.32 percent), followed by vegetation (24.44–27.57 percent) and roads (17.58–18.89 percent). Visual complexity falls between 6.06 and 6.30 on the recorded scale.

4.3 Model identification, testing, and revision

The final analytical model needs to be established with exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. We conducted an exploratory factor analysis using SPSS 31 and report the results in Table 4. We applied principal component analysis with varimax rotation and obtained the total variance explained. The bartlett test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure was 0.964, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Four factors were extracted and they explained 66.233 percent of the total variance, and factor loadings below 0.45 would be excluded (Wu, 2009).

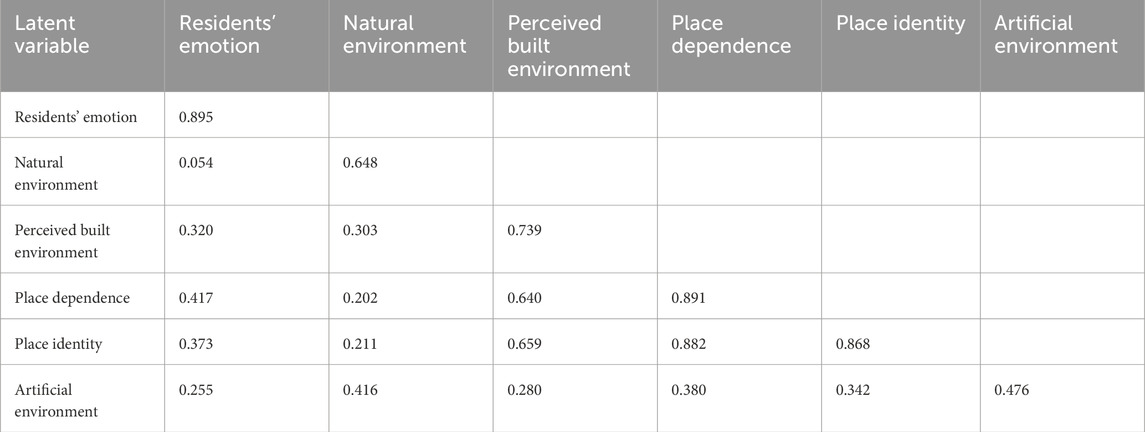

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis of the measurement model and evaluated its reliability and validity as summarized in Table 5. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability. Validity was evaluated with average variance extracted and the Fornell–Larcker criterion for discriminant validity (Table 6). We also computed variance inflation factors to check for multicollinearity. The standardized loading for the Dominance indicator was 0.457, which did not meet the inclusion threshold. After removing this indicator, the model met accepted standards. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability exceeded 0.70, and all standardized loadings were greater than 0.50. Average variance extracted ranged from 0.520 to 0.801 and was above 0.50. For each construct, the square root of its AVE was larger than its correlations with other constructs, which supports discriminant validity as shown in Table 5. All VIF values were below 5, indicating no multicollinearity in the measurement model (Hair et al., 2011).

4.4 Model fit analysis

To assess path significance and predictive performance, we applied bootstrapping and PLSpredict to obtain R2 and Q2 for each latent construct. The R2 values are 0.491 for place dependence, 0.483 for place identity, and 0.145 for residents’ emotion, which indicates acceptable explained variance. The corresponding Q2 values are 0.451, 0.458, and 0.136, all above zero and therefore supportive of predictive relevance. Model fit was further evaluated with the standardized root mean square residual. The SRMR equals 0.06, which is below the commonly used threshold of 0.08. Taken together, these indices indicate that the proposed structural model fits the data well and provides good explanatory power.

4.5 Structural model analysis

4.5.1 Direct, indirect, and total effects

Table 7 and Figure 3 reports the direct, indirect, and total effects with residents’ emotion as the mediator. For place identity, the direct path from perceived built environment is 0.578 and the total effect is 0.623, both p < 0.001. For place dependence, the direct path is 0.537 and the total effect is 0.595, p < 0.001. By comparison, the artificial environment has negative total effects of −0.192 on place identity and −0.247 on place dependence, each supported by significant negative indirect paths through residents’ emotion. The natural environment shows small positive indirect effects; the total effect on place dependence is 0.081 (p < 0.05), whereas the total effect on place identity is positive but not significant. In substantive terms, the total influence of perceived environmental quality is about 3.2 times the magnitude of the artificial environment for identity (0.623 versus 0.192 in absolute value) and about 2.4 times for dependence (0.595 versus 0.247). Model explanatory power is moderate for the two attachment constructs and modest for residents’ emotion. The adjusted R squared is 0.486 for place identity with a 95 percent confidence interval of 0.438–0.541, 0.495 for place dependence with a 95 percent confidence interval of 0.446–0.548, and 0.146 for residents’ emotion with a 95 percent confidence interval of 0.102–0.198. These magnitudes indicate that improving perceived environmental quality is more strongly associated with attachment than comparable changes in objective features, while artificial elements tend to erode attachment.

Table 7. Estimated direct, indirect, and total effects of objective and perceived built environments on place attachment via residents’ emotion.

4.6 Multi-group analysis

Table 8 shows that the effects of environmental factors on place attachment differ by length of residence. The perceived built environment remains the strongest positive predictor in every group, which means improvements in perceived cleanliness, safety, and walkability are likely to increase attachment regardless of how long residents have lived in the area. The natural environment is positively related to attachment only among residents with a moderate length of residence. This suggests that greening or nature-based amenities are most consequential once residents have had time to engage with local spaces but before long-term habituation sets in. Artificial elements show negative associations with attachment across all groups, and this erosion is most pronounced for the moderate-residence group. In practical terms, remediation of intrusive artificial features such as traffic burden, visual clutter, or noise is especially important during the consolidation stage of settlement.

Table 8. The total impact of the objective and perceived built environment on place attachment, grouped by residence duration.

Table 9 presents the multi-group analysis results stratified by age. The perceived built environment shows a strong and stable positive association with attachment for younger, middle-aged, and older residents alike, indicating that design and management actions that enhance perceived quality are broadly beneficial. Natural elements display weak and non-significant associations across ages, implying that greening by itself is unlikely to shift attachment without concurrent improvements in perceived quality. The negative association of artificial elements with attachment is largest among younger residents and diminishes with age. This pattern implies that reducing adverse artificial features has the greatest payoff for younger cohorts, while older residents appear less sensitive to these conditions or may offset them through established routine.

Table 9. The total impact of the objective and perceived built environment on place attachment, grouped by age.

5 Discussion

5.1 Main findings

This study evaluates how objective and perceived features of the built environment differentially shape place attachment and clarifies the mediating role of residents’ emotion. It also examines heterogeneity by residence duration and age. Specifically, natural environment shows a significant positive total effect on place dependence to partially support H1a. For H1b, artificial environment demonstrates significant negative direct and total effects on both place dependence and place identity. H2 is strongly supported, with perceived built environment exhibiting robust positive direct and total effects on both dimensions of place attachment. H3 and H4 are supported, as both objective and perceived built environment show significant indirect effects on place attachment through the mediation of residents’ emotion. Finally, H5 is partially supported. Significant variations in the impact of natural environment on place attachment are observed across residence duration groups. For artificial environment, significant age-based heterogeneity is found, with younger residents showing stronger negative impacts. Perceived built environment effects are consistently strong and positive across all demographic groups. These findings accord with the view that attachment is a subjective psychological bond. Perceptions and emotions are the proximal drivers of attachment, and objective features influence attachment mainly by shaping those perceptions and emotions. Within the tripartite model, perceived quality and affect lie in the psychological process that links person and place. Under a stimulus–organism–response view, objective features operate as stimuli that generate appraisals and emotions, which then relate to attachment.

5.2 The differential effect of objective and perceived built environment on place attachment

Our findings emphasize the distinct roles of objective and perceived built environment in shaping place attachment. Regarding the objective built environment, the direct effects of natural environment are not significant. This suggests that the inherent qualities of natural landscapes may be associated with functional attachment via positive emotions (Ancora et al., 2022; Sander et al., 2025), while their link to the symbolic meaning or self-identification with a place might be less direct in the urban context. This may be because natural elements (e.g., parks, street trees, a view of the sky) are often fragmented and exist in constant competition with overwhelming artificial stimuli like traffic, noise, and buildings (Feng et al., 2024). Therefore, such features may be less strongly associated with residents’ direct attachment to the local area. Conversely, the artificial environment consistently demonstrated a detrimental impact on both place dependence and place identity. This aligns with previous research indicating that dense, artificial, or traffic-congested environments can induce stress, reduce perceived safety, and diminish overall environmental quality, which are in turn associated with weaker place attachment (Qi et al., 2023).

The overwhelming strength of the perceived environment’s direct positive effect on place attachment suggests that the psychological experience of a place (including its perceived beauty, safety, walkability, and liveliness) is the most proximate determinant of whether a resident forms a meaningful connection to it. This pattern suggests the formation of attachment relates less to objective physical characteristics and more to cognitive and emotional interpretations of those characteristics. This may be due to the fact that place attachment is fundamentally an emotional bond based on the personal meaning we assign to our surroundings, and these subjective feelings form the true basis of our connection to a place (Lewicka, 2011; Von Wirth et al., 2016). Furthermore, the difference in the impact of objective and perceived built environments on place attachment may be due to the fact that the objective environment is the raw physical reality, while the perceived environment is a subjective, meaningful interpretation of reality filtered through personal experiences and needs. Consequently, our attachment appears more strongly associated with this personal interpretation than by the objective facts themselves (Chang et al., 2023).

5.3 Mediating effects of the residents’ emotion

This study demonstrates that residents’ emotion is an important mediating factor in the relationship between the built environment and place attachment. Both natural and artificial environment exert significant indirect effects on place attachment through residents’ emotion. For natural environment, this operates primarily through an emotional pathway and is associated with higher place dependence. This can be attributed to the natural environment evoke positive residents’ emotion and restorative experiences (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989; Ulrich, 1993). For artificial environment, the significant negative mediation via emotion suggests that these elements are linked to negative residents’ emotion, directly contributing to weaker attachment. This highlights that the emotion quality of human-environment interactions is a crucial mechanism in place attachment formation (Ariannia et al., 2024; Manzo, 2005). Similarly, the positive association of perceived built environment on place attachment is also significantly mediated by residents’ emotion. This indicates that when residents perceive their environment positively (e.g., as beauty, safety, or greenness), these perceptions elicit positive emotions, which in turn reinforce their attachment to the place (Liu et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2024). The consistent and strong mediation by emotion across objective and perceived built environment underscores its central role in translating physical environment and experiences into the emotion bonds that constitute place attachment.

5.4 Heterogeneity by residence duration and age

The results indicate a dynamic link between the built environment and place attachment. For residence duration, the natural environment showed a significantly stronger association with both dependence and identity among residents with moderate tenure (10–30 years) than among newer residents (less than 10 years). This suggests that the appreciation and functional reliance on natural elements for place attachment may develop or become more pronounced after a certain period of establishment in a neighborhood (Anton and Lawrence, 2014). The consistently negative impact of the artificial environment across all duration groups implies that negative aspects of urban settings, such as traffic or noise, remain a persistent factor regardless of how long one has lived in the area. The strong, stable positive effect of perceived built environment across all groups highlights the enduring importance of positive subjective environmental appraisals for all residents.

Furthermore, younger residents (18–44 years) showed a significantly stronger negative association with artificial environment compared to middle-aged and older residents. This heightened sensitivity among younger adults may be attributed to their greater responsiveness to urban stressors such as noise and crowding. Additionally, younger generations are generally more geographically mobile and may form place attachments that are more contingent on instrumental considerations, including economic opportunities, lifestyle amenities, and perceptions of environmental aesthetics or functional quality, rather than enduring social bonds or long-term residence. In contrast, for older adults, place attachment tends to deepen with age and is often grounded in long-term residency, the accumulation of personal and historical memories, and established social networks, all of which contribute to a sense of stability and belonging. Consequently, older residents show no significant association with the objective built environment in shaping their place attachment.

6 Conclusion

This study advances theory on place attachment by identifying and testing the mediating channels through which objective and perceived features of the built environment shape attachment. The analysis incorporates heterogeneity across residence duration and age groups and clarifies how environmental stimuli influence attachment through emotion processing, which can strengthen or weaken bonds depending on the states evoked. The results show that perceived built environment has a strong and direct positive effect on both place identity and place dependence. While the objective natural environment showed positive indirect effects on place dependence mediated by emotion, the objective artificial environment demonstrated negative direct and indirect effects on both place dependence and identity. Residents’ emotion consistently emerged as a crucial mediator, translating environmental characteristics and subjective perceptions into attachment bonds. Significant demographic heterogeneity was observed, with the natural environment’s impact varying by residence duration and the artificial environment’s impact differing by age. This study addresses a key gap by clarifying how micro-scale environmental stimuli translate into place attachment, offering actionable insights for urban planning aimed at fostering human-place connections by creating environments that are perceptually positive and dominated by natural elements. These findings give policymakers an evidence base to ensure that diverse perceived experiences guide inclusive placemaking.

6.1 Implication and limitation

This study advances the theoretical framework by empirically demonstrating that place-related residents’ emotion mediates the associations linking objective built-environment attributes, distinguished into natural and artificial components, and perceived built-environment appraisals to place attachment. The results indicate that environmental characteristics influence attachment behaviors significantly through emotional responses elicited by both objective features and subjective perceptions. The perceived built environment shows the largest total effects on attachment, exceeding the natural environment and the magnitude of the artificial environment’s negative effects. This pattern suggests that improving perceived safety, cleanliness, walkability, and related qualities is likely to yield larger gains in attachment than comparable increases in greenery unless greening also improves perceived quality. Evidence of dynamic heterogeneity across residential tenure and age indicates that social and environmental interactions evolve over time and influence how people internalize their surroundings. Analytical attention should therefore focus on temporal processes and on how these processes condition the integration of environmental exposures with individual appraisals. Emphasizing the characteristics of specific groups offers a useful lens for explaining how the built environment translates into place attachment and provides a basis for more targeted planning and policy.

To strengthen place attachment, urban planning should enhance the built environment by integrating natural features and carefully managing artificial elements. For instance, enhancing the presence and quality of natural environment is supported by its positive emotional mediation. In parallel, adverse impacts from man made features can be reduced through speed management on streets and the use of green buffers that attenuate noise and visual intrusions. Residents with longer tenure may benefit from neighborhood social hubs that build attachment to place. Because perceived environmental quality consistently matters, initiatives that improve how people experience their surroundings should aid all residents. Given the effect sizes noted above, interventions that demonstrably raise perceived quality should be prioritized when resources are limited. Focusing on micro scale upgrades to streetscapes and public spaces is also practical for planners, since fine grained interventions are typically faster to implement and less costly than large scale schemes. Such micro-level interventions offer actionable and scalable pathways to fostering a greater sense of belonging.

This study has limitations. First, the cross-sectional design can identify associations but cannot establish causality. Future work should employ longitudinal data, repeated cross-sections, or quasi-experimental strategies to establish causal pathways. Second, our analysis is restricted to the most prominent historic districts in Nanjing, which limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader urban context. Extending the sampling frame to additional neighborhoods would improve external validity. Third, the coverage of features is necessarily selective. The objective measures rely on visual street view imagery, primarily capturing traffic and modern artificial classes, and may underrepresent culturally or aesthetically valued artificial elements while omitting nonvisual stimuli such as noise and smells. Future studies should incorporate multisensory and finer semantic indicators, examine additional sociodemographic moderators such as sex, and use interpretable models to identify effect thresholds across scales. We were unable to identify threshold ranges for the built-environment elements. Future work should employ richer metrics and interpretable machine learning to estimate the specific effect ranges of objective built-environment features on place attachment across multiple geographic scales. Fourth, our estimands are at the micro environment level and individual ratings were aggregated to image level means. This choice reduces within image variation, can introduce measurement error and residual dependence given one to three raters per image, and does not permit individual level interpretation. Future work should use multilevel or cross classified models with more raters per image to model clustering and measurement error. Fifth, because each photograph received one to three ratings, averaging these scores creates unequal reliability across images. Estimating the model with unweighted image means and an image-only bootstrap may understate variability and obscure heterogeneity. Future work should apply precision weighting and multilevel models with cluster-aware resampling that accounts for both images and raters.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

ZQ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Resources. WL: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review and editing, Supervision. YW: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (Program No. 2025JC-YBMS-373); Social Science Foundation Program of Shaanxi (Program No. 2025J003); China Scholarship Council (Program No. 202406090214).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbuil.2025.1727570/full#supplementary-material

References

Amen, M. A., Afara, A., and Nia, H. A. (2023). Exploring the link between street layout centrality and walkability for sustainable tourism in historical urban areas. Urban Sci. 7 (2), 67. doi:10.3390/urbansci7020067

Ancora, L. A., Blanco-Mora, D. A., Alves, I., Bonifacio, A., Morgado, P., and Miranda, B. (2022). Cities and neuroscience research: a systematic literature review. Front. Psychiatry 13, 983352. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.983352

Anton, C. E., and Lawrence, C. (2014). Home is where the heart is: the effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. J. Environ. Psychol. 40, 451–461. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.10.007

Arbab, P. (2023). Place identification process: a structural equation modeling of the relationship between humans and the built environment. GeoJournal 88 (4), 4009–4029. doi:10.1007/s10708-023-10844-3

Arbab, P., Azizi, M. M., and Zebardast, E. (2018). Place-identity formation in new urban developments of Tehran metropolis. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 144 (2), 05018010. doi:10.1061/(asce)up.1943-5444.0000446

Ariannia, N., Naseri, N., and Yeganeh, M. (2024). Cognitive-emotional feasibility of the effect of visual quality of building form on promoting the sense of place attachment (case study: cultural iconic buildings of Iran’s contemporary architecture). Front. Archit. Res. 13 (1), 37–56. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2023.10.002

Aziz Amen, M., and Nia, H. A. (2018). The dichotomy of society and urban space configuration in producing the semiotic structure of the modernism urban fabric. Semiotica 2018 (222), 203–223. doi:10.1515/sem-2016-0141

Boley, B. B., Strzelecka, M., Yeager, E. P., Ribeiro, M. A., Aleshinloye, K. D., Woosnam, K. M., et al. (2021). Measuring place attachment with the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS). J. Environ. Psychol. 74, 101577. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101577

Bonaiuto, M., Fornara, F., and Bonnes, M. (2003). Indexes of perceived residential environment quality and neighbourhood attachment in urban environments: a confirmation study on the city of Rome. Landsc. Urban Plan. 65 (1-2), 41–52. doi:10.1016/s0169-2046(02)00236-0

Bottini, L. (2023). The role of neighborhood quality in predicting place attachment: results from ITA.LI, a newly established nationwide Italian panel survey. Cities 143, 104632. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2023.104632

Bradley, M. M., and Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion: the self-assessment mannequin and the semantic differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 25 (1), 49–59. doi:10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9

Brown, B., Perkins, D. D., and Brown, G. (2003). Place attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: individual and block levels of analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 23 (3), 259–271. doi:10.1016/s0272-4944(02)00117-2

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., and Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cao, X., MacNaughton, P., Deng, Z., Yin, J., Zhang, X., and Allen, J. (2018). Using Twitter to better understand the spatiotemporal patterns of public sentiment: a case study in Massachusetts, USA. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15 (2), 250. doi:10.3390/ijerph15020250

Cao, Y., Yang, P., Xu, M., Li, M., Li, Y., and Guo, R. (2025). A novel method of urban landscape perception based on biological vision process. Landsc. Urban Plan. 254, 105246. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2024.105246

Chan, E. T. H., and Li, T. E. (2022). The effects of neighbourhood attachment and built environment on walking and life satisfaction: a case study of Shenzhen. Cities 130, 103940. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2022.103940

Chang, J., Lin, Z., Vojnovic, I., Qi, J., Wu, R., and Xie, D. (2023). Social environments still matter: the role of physical and social environments in place attachment in a transitional city, Guangzhou, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 232, 104680. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104680

Cheng, C.-K., and Kuo, H.-Y. (2015). Bonding to a new place never visited: exploring the relationship between landscape elements and place bonding. Tour. Manag. 46, 546–560. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.006

Chishima, Y., Minoura, Y., Uchida, Y., Fukushima, S., and Takemura, K. (2023). Who commits to the community? Person-community fit, place attachment, and participation in local Japanese communities. J. Environ. Psychol. 86, 101964. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.101964

Davidson, J., and Milligan, C. (2004). Embodying emotion sensing space: introducing emotional geographies. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 5 (4), 523–532. doi:10.1080/1464936042000317677

Escolà-Gascón, Á., Dagnall, N., Denovan, A., Maria Alsina-Pagès, R., and Freixes, M. (2023). Evidence of environmental urban design parameters that increase and reduce sense of place in Barcelona (Spain). Landsc. Urban Plan. 235, 104740. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104740

Ewing, R., and Handy, S. (2009). Measuring the unmeasurable: urban design qualities related to walkability. J. Urban Des. 14 (1), 65–84. doi:10.1080/13574800802451155

Fei, X., Hamilton, G. G., and Zheng, W. (1992). From the soil: the foundations of Chinese society. Oakland: University of California Press.

Feng, L., Wang, J., Liu, B., Hu, F., Hong, X., and Wang, W. (2024). Does urban green space pattern affect green space noise reduction? Forests 15 (10), 1719. doi:10.3390/f15101719

Guo, Y., Wang, B., Li, W., and Xu, H. (2024). Deciphering the impacts of environmental perceptions on place attachment from the perspective of place of origin: a case study of rural China. Appl. Geogr. 162. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2023.103165

Guo, J., Yanai, S., and Xu, G. (2024). Community gardens and psychological well-being among older people in elderly housing with care services: the role of the social environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 94, 102232. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2024.102232

Guo, Y., Liu, Y., Lu, S., Chan, O. F., Chui, C. H. K., and Lum, T. Y. S. (2021). Objective and perceived built environment, sense of community, and mental wellbeing in older adults in Hong Kong: a multilevel structural equation study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 209, 104058. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104058

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19 (2), 139–152. doi:10.2753/mtp1069-6679190202

Halpenny, E. A. (2010). Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: the effect of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 30 (4), 409–421. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.04.006

Hidalgo, M. C., and HernÁNdez, B. (2001). Place attachment: conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 21 (3), 273–281. doi:10.1006/jevp.2001.0221

Hosany, S., Prayag, G., Van Der Veen, R., Huang, S., and Deesilatham, S. (2016). Mediating effects of place attachment and satisfaction on the relationship between tourists’ emotions and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 56 (8), 1079–1093. doi:10.1177/0047287516678088

Huang, X., Wang, S., Yang, D., Hu, T., Chen, M., Zhang, M., et al. (2024). Crowdsourcing geospatial data for earth and human observations: a review. J. Remote Sens. 4, 0105. doi:10.34133/remotesensing.0105

Jorgensen, B. S., and Stedman, R. C. (2006). A comparative analysis of predictors of sense of place dimensions: attachment to, dependence on, and identification with lakeshore properties. J. Environ. Manage 79 (3), 316–327. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.08.003

Kaplan, R., and Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: a psychological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koohsari, M. J., Yasunaga, A., Oka, K., Nakaya, T., Nagai, Y., and McCormack, G. R. (2023). Place attachment and walking behaviour: mediation by perceived neighbourhood walkability. Landsc. Urban Plan. 235, 104767. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104767

Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: how far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 31 (3), 207–230. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

Li, S.-m., Mao, S., and Du, H. (2019). Residential mobility and neighbourhood attachment in Guangzhou, China. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 51 (3), 761–780. doi:10.1177/0308518x18804828

Li, X., Li, Z., Jia, T., Yan, P., Wang, D., and Liu, G. (2021). The sense of community revisited in Hankow, China: combining the impacts of perceptual factors and built environment attributes. Cities 111, 103108. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2021.103108

Li, J., Luo, J., Deng, T., Tian, J., and Wang, H. (2023). Exploring perceived restoration, landscape perception, and place attachment in historical districts: insights from diverse visitors. Front. Psychol. 14, 1156207. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1156207

Liu, Q., Wu, Y., Xiao, Y., Fu, W., Zhuo, Z., van den Bosch, C. C. K., et al. (2020). More meaningful, more restorative? Linking local landscape characteristics and place attachment to restorative perceptions of urban park visitors. Landsc. Urban Plan. 197, 103763. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103763

Liu, Z., Abd Malek, M. I. B., Harun, N. Z. B., Ja`afar, N. H. B., Song, Y., Tang, Y., et al. (2024). How do streetscape visual components affect public perception in post-renewed neighborhoods: a case study in Chengdu. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 24, 1–18. doi:10.1080/13467581.2024.2399684

Low, S. M., and Altman, I. (1992). “Place attachment: a conceptual inquiry,” in Place attachment (Springer), 1–12.

Lu, T., Zhang, F., and Wu, F. (2018). Place attachment in gated neighbourhoods in China: evidence from Wenzhou. Geoforum 92, 144–151. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.04.017

Manzo, L. C. (2003). Beyond house and haven: toward a revisioning of emotional relationships with places. J. Environ. Psychol. 23 (1), 47–61. doi:10.1016/s0272-4944(02)00074-9

Manzo, L. C. (2005). For better or worse: exploring multiple dimensions of place meaning. J. Environ. Psychol. 25 (1), 67–86. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.01.002

Mehrabian, A., and Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Morgan, P. (2010). Towards a developmental theory of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 30 (1), 11–22. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.07.001

Mouratidis, K., and Poortinga, W. (2020). Built environment, urban vitality and social cohesion: do vibrant neighborhoods foster strong communities? Landsc. Urban Plan. 204, 103951. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103951

Nia, H. A., Atun, R. A., and Rahbarianyazd, R. (2017). Perception based method for measuring the aesthetic quality of the urban environment. Open House Int. 42 (2), 11–19. doi:10.1108/ohi-02-2017-b0003

Ogawa, Y., Oki, T., Zhao, C., Sekimoto, Y., and Shimizu, C. (2024). Evaluating the subjective perceptions of streetscapes using street-view images. Landsc. Urban Plan. 247, 105073. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2024.105073

Orstad, S. L., McDonough, M. H., Stapleton, S., Altincekic, C., and Troped, P. J. (2016). A systematic review of agreement between perceived and objective neighborhood environment measures and associations with physical activity outcomes. Environ. Behav. 49 (8), 904–932. doi:10.1177/0013916516670982

Peng, J., Strijker, D., and Wu, Q. (2020). Place identity: how far have we come in exploring its meanings? Front. Psychol. 11, 294. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00294

Qi, Z., Duan, J., Su, H., Fan, Z., and Lan, W. (2023). Using crowdsourcing images to assess visual quality of urban landscapes: a case study of Xiamen Island. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110793. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110793

Raymond, C. M., Brown, G., and Weber, D. (2010). The measurement of place attachment: personal, community, and environmental connections. J. Environ. Psychol. 30 (4), 422–434. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.08.002

Sander, M., Klimesch, A., Samaan, L., Kühn, S., Augustin, J., and Ascone, L. (2025). Natural vs. built visual urban landscape elements around the home and their associations with mental and brain health of residents: a narrative review. J. Environ. Psychol. 104, 102559. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2025.102559

Scannell, L., and Gifford, R. (2010). Defining place attachment: a tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 30 (1), 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.09.006

Scannell, L., and Gifford, R. (2017). The experienced psychological benefits of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 51, 256–269. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.04.001

Sun, J., and Wang, X. (2010). Value differences between generations in China: a study in Shanghai. J. Youth Stud. 13 (1), 65–81. doi:10.1080/13676260903173462

Sun, Y., Fang, Y., Yung, E. H. K., Chao, T.-Y. S., and Chan, E. H. W. (2020). Investigating the links between environment and older people’s place attachment in densely populated urban areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 203, 103897. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103897

Taylor, Z. (2016). The New American suburb: poverty, race and the economic crisis. URBAN Des. Int. 23 (1), 64–65. doi:10.1057/s41289-016-0001-0

Tveit, M., Ode, A., and Fry, G. (2006). Key concepts in a framework for analysing visual landscape character. Landsc. Res. 31 (3), 229–255. doi:10.1080/01426390600783269

Vieira, V. A. (2013). Stimuli–organism-response framework: a meta-analytic review in the store environment. J. Bus. Res. 66 (9), 1420–1426. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.05.009

von Wirth, T., Grêt-Regamey, A., and Stauffacher, M. (2014). Mediating effects between objective and subjective indicators of urban quality of life: testing specific models for safety and access. Soc. Indic. Res. 122 (1), 189–210. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0682-y

von Wirth, T., Grêt-Regamey, A., Moser, C., and Stauffacher, M. (2016). Exploring the influence of perceived urban change on residents’ place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 46, 67–82. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.03.001

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., and Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect - the panas scales. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 54 (6), 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Wilson, E. O., and Kellert, S. R. (1993). The biophilia hypothesis. Washington: Island Press, 73–137.

Wu, M. (2009). Structural equation model: operation and application of AMOS. Chongqing: Chongqing University Press.

Wu, R., Huang, X., Li, Z., Liu, Y., and Liu, Y. (2019). Deciphering the meaning and mechanism of migrants’ and locals’ neighborhood attachment in Chinese cities: evidence from Guangzhou. Cities 85, 187–195. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2018.09.006

Xiang, L., Cai, M., Ren, C., and Ng, E. (2021). Modeling pedestrian emotion in high-density cities using visual exposure and machine learning: tracking real-time physiology and psychology in Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 205, 108273. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108273

Xue, Q., Yang, J., Zhang, J., and Liu, X. (2025). Analysis of the renewal of Nanjing Confucius temple block based on fold theory. GeoJournal 90 (4), 157. doi:10.1007/s10708-025-11418-1

Yang, L., Marmolejo Duarte, C., and Martí Ciriquián, P. (2022). Quantifying the relationship between public sentiment and urban environment in Barcelona. Cities 130, 103977. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2022.103977

Yang, S., Dane, G., van den Berg, P., and Arentze, T. (2024). Influences of cognitive appraisal and individual characteristics on citizens’ perception and emotion in urban environment: model development and virtual reality experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 96, 102309. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2024.102309

Yuan, F., Gao, J., and Wu, J. (2016). Nanjing-an ancient city rising in transitional China. Cities 50, 82–92. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2015.08.015

Zhang, F., Zhou, B., Liu, L., Liu, Y., Fung, H. H., Lin, H., et al. (2018). Measuring human perceptions of a large-scale urban region using machine learning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 180, 148–160. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.08.020

Zhu, D., Jia, Z., and Zhou, Z. (2021). Place attachment in the Ex-situ poverty alleviation relocation: evidence from different poverty alleviation migrant communities in Guizhou Province, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 75, 103355. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2021.103355

Keywords: place attachment, objective built environment, perceived built environment, residents’ emotion, mediating effects

Citation: Qi Z, Lan W and Wang Y (2025) Differential effects of objective and perceived environments on place attachment with emotion mediation: a case study in Nanjing, China. Front. Built Environ. 11:1727570. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2025.1727570

Received: 18 October 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025;

Published: 12 December 2025.

Edited by:

Shixian Luo, Southwest Jiaotong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Hourakhsh Ahmad Nia, Alanya University, TürkiyeMeng Meng Li, Harbin Institute of Technology, China

Parsa Arbab, University of Tehran, Iran

Aurora De Jesús Mejía-Castillo, Universidad Veracruzana, Mexico

Vicenta Reynoso-Alcántara, Universidad Veracruzana, Mexico

Copyright © 2025 Qi, Lan and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenlong Lan, bGFud2VubG9uZ0B4YXVhdC5lZHUuY24=

Zhuoxu Qi

Zhuoxu Qi Wenlong Lan

Wenlong Lan Yu Wang

Yu Wang