- 1School of Biodiversity, One Health and Veterinary Medicine, College of Medical Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

- 2Biodiversity Initiative, Houghton, MI, United States

- 3Biodiversity Research Institute, Portland, ME, United States

- 4Department of Bird Migration, Swiss Ornithological Institute, Sempach, Switzerland

- 5CIBIO—Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources—InBIO Associate Laboratory, University of Porto, Vairão, Portugal

- 6BIOPOLIS Program in Genomics, Biodiversity and Land Planning, CIBIO, University of Porto, Vairão, Portugal

- 7Department of Renewable Natural Resources, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, United States

- 8National University of Equatorial Guinea (UNGE), Malabo, Equatorial Guinea

- 9National Institute for Forestry Development and Protected Area Management (INDEFOR-AP), Bata, Equatorial Guinea

- 10College of Forest Resources and Environmental Science, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI, United States

- 11Department of Biology, University of Nebraska at Kearney, Kearney, NE, United States

- 12Field Museum, Negaunee Integrative Research Center, Chicago, IL, United States

The human population of sub-Saharan Africa is projected to triple by 2100, drastically increasing anthropogenic pressure on biodiversity. When rainforest is disturbed by anthropogenic drivers, species respond heterogeneously; these patterns have rarely been quantified for Congo rainforest fauna. Our objective was to understand how community composition changed with human disturbance—with particular interest in the guilds and species that indicate primary rainforest. At a long-term bird banding site on mainland Equatorial Guinea, we captured over 3200 birds across 6 field seasons in selectively logged secondary forest and in largely undisturbed primary forest. Our multivariate ordination indicated a significant split between primary and secondary forest communities. We caught 47% fewer birds in secondary forest overall, with Dorylus ant-followers, mixed-species flockers and terrestrial insectivores showing at least two-fold reductions. We identified 12 species that were characteristic of primary forest. Of those, 10 were strict insectivores: terrestrial insectivores (Sheppardia cyornithopsis, Illadopsis cleaveri, I. fulvescens/rufipennis), mixed-flockers (Phyllastrephus icterinus/xavieri, Elminia nigromitrata, Terpsiphone rufiventer, Pardipicus nivosus, Deleornis fraseri), ant-followers (Alethe castanea, Chamaetylas poliocephala), White-bellied Kingfisher (Corythornis leucogaster), and Blue-headed Wood Dove (Turtur brehmeri). Only the kingfisher Ispidina lecontei was captured more in secondary forest. This contributes to a growing body of Pantropical literature suggesting that insectivores living on or near the forest floor are vulnerable to rainforest degradation. Notably, few species disappeared entirely in secondary forest (unlike patterns seen in the Neotropics); rather, capture rates of 12 of 30 species (40%) were significantly reduced relative to primary forest. By understanding disturbance-sensitive guilds and species, we might identify the proximate mechanisms responsible for the loss of Afrotropical birds, thus helping to manage communities as forest disturbance continues.

1 Introduction

The Congo rainforest (herein including Lower Guinea Forest) Central Africa constitutes the second largest tract of tropical rainforest on Earth (Hardy et al., 2013) and serves as a significant global carbon sink (Baccini et al., 2012; Hubau et al., 2020). Still, Afrotropical forests are experiencing increasing rates of forest loss and disturbance, mainly driven by non-mechanized, small-scale agriculture and selective logging (Potapov et al., 2017; Tyukavina et al., 2018). These drivers are linked to the increasing human population of sub-Saharan Africa (Potapov et al., 2017; Tyukavina et al., 2018), which is projected to triple to almost 3.8 billion by the end of the 21st century (Vollset et al., 2020). Industrial logging and large-scale mechanized agriculture will also likely increase in the future, which may allow increased encroachment of smallholder agriculture into previously undisturbed areas (Tyukavina et al., 2018). Given these threats and their effects on existing forests, it is essential to address gaps in our understanding of how the region’s biodiversity responds to forest degradation. In Equatorial Guinea, most high-grade selective logging took place during the oil boom period of the 2000s and early 2010s, but primary forest loss has stabilized and is lower than in other central-African countries (Tyukavina et al., 2018). This provides a valuable opportunity to gather baseline data on tropical forest ecosystems which can then aid in their management and protection. Furthermore, it is important to understand the value of secondary forest in fostering biodiversity in the face of increased forest degradation and a changing climate (Poorter et al., 2016). In Western and Central Africa, primary forests only account for 38% of total forest area (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 2020); as such, simply protecting primary forests alone may not be a realistic or effective way to conserve biodiversity and ecosystem function (Cox and Underwood, 2011; Struhsaker et al., 2005).

Afrotropical forests are particularly important for the conservation of terrestrial biodiversity (Jung et al., 2021). Despite their designation as global biodiversity hotspots and increasing pressure from population growth (Morris, 2010; Pereira et al., 2012), Afrotropical forests are disproportionately understudied compared to the Neotropics and Asian Paleotropics (Malhi et al., 2013). For example, Di Marco et al. (2017) found that, of 2,553 articles on conservation published between 2011 and 2015, only 10% focused on the Afrotropics. Of those, most focused on large mammals and several countries were omitted completely, with little focus on other terrestrial taxa, like avifauna, which can be indicators of forest health. Tropical birds also play important roles in ecosystem functioning and services (Gray et al., 2007; Newbold et al., 2013); insectivores can control agricultural pests (Whelan et al., 2008; Ferreira et al., 2023)and frugivores can aid in seed-dispersal and germination (Şekerciolu, 2006; Wenny et al., 2011). Certain guilds—such as understory insectivores—may also act as sentinels of habitat disturbance or degradation as they show particular sensitivity to such changes in habitat conditions; however, this has rarely been investigated or quantified in the Afrotropics (Powell et al., 2015). Tropical forest birds are often used to understand the effects of forest degradation on ecological integrity, due to being a diverse, sparsely hunted, and often sensitive group, with extensive data on the morphological and ecological traits of species across communities (Şekercioğlu et al., 2012; Bregman et al., 2014). Pantropical and global literature reviews such as those of Gray et al. (2007), Newbold et al. (2013), and Bregman et al. (2014) highlight that tropical insectivores are more vulnerable than other guilds.

In general, studies from other tropical regions have shown that understory insectivores are particularly sensitive to forest fragmentation (Stouffer and Bierregaard, 1995; Robinson, 1999; Beier et al., 2002; Şekerciolu et al., 2002; Sodhi et al., 2004; Barlow et al., 2006). In regenerating secondary forests in the Amazon, understory insectivores—particularly the terrestrial insectivores—took decades longer than other avian guilds to reach densities comparable to primary forest (Powell et al., 2013). Insectivores that participate in mixed-species flocks (species that forage and move together; Winterbottom, 1943, Morse, 1970) have shown high sensitivity to habitat degradation and disturbance; in the Asian Paleotropics, mixed-flock participants are the most sensitive group to human activity along with forest and understory specialists (Lee et al., 2005; Mammides et al., 2015). In the Neotropics, the species richness, stability and size of mixed-flocks are sensitive to habitat fragmentation (Stouffer and Bierregaard, 1995; Thiollay, 1997; Develey and Stouffer, 2001; Maldonado-Coelho and Marini, 2004; Mokross et al., 2014, 2018). It is possible that African mixed-flock species could respond differently to these threats as they appear to be less stable, with participants not defending a communal territory and with more species being opportunistic flock members (McClure, 1967).

Many insectivorous birds follow swarms of predatory ants (hereafter “ant-followers”), such as Afrotropical driver ants (Dorylus spp.) or the Neotropical army ant Eciton burchellii, and feed on the organisms that flee from the swarm (Brosset, 1969; Willis and Oniki, 1978; Chesser, 1995). Swarmraiding ants are considered keystone species that have a profound impact on ecosystems, with Dorylus colonies containing up to 20 million individuals (Gotwald, 1995). Neotropical ant-following birds are often among the first guilds to disappear or decrease in richness and flock size in small forest fragments (Harper, 1989; Stouffer and Bierregaard, 1995; Roberts et al., 2000; Kumar and O’Donnell, 2007). Though the Afrotropical equivalents are less well known, a handful of studies from Africa have now found that ant-followers and terrestrial insectivores decrease in species richness or abundance in response to disturbance (Waltert et al., 2005; Peters and Okalo, 2009; Jarrett et al., 2021; Miller et al., 2021).

The overall aim of this study was to describe if and how Central African bird communities differ between primary and disturbed secondary rainforest. The primary objectives were:

● To determine the degree to which understory bird communities differ between primary and secondary forest (via ordination).

● To compare capture rates of foraging guilds and species to determine the drivers of community dissimilarity between primary and secondary forests (via mixed models).

● To identify which species are “indicators” of primary forest (via indicator species analysis). Here, we define a primary forest indicator as a species that is found significantly less frequently in secondary forest in our indicator analysis and is therefore assumed to be sensitive to human disturbance.

Based on evidence from other tropical regions (Stouffer and Bierregaard, 1995; Robinson, 1999; Beier et al., 2002; Şekerciolu et al., 2002; Sodhi et al., 2004; Barlow et al., 2006; Powell et al., 2013), we predict that the three understory insectivore guilds (terrestrial insectivores, mixed-species flockers, and ant-following birds) will have lower capture rates in secondary forest.

2 Methods

2.1 Study area

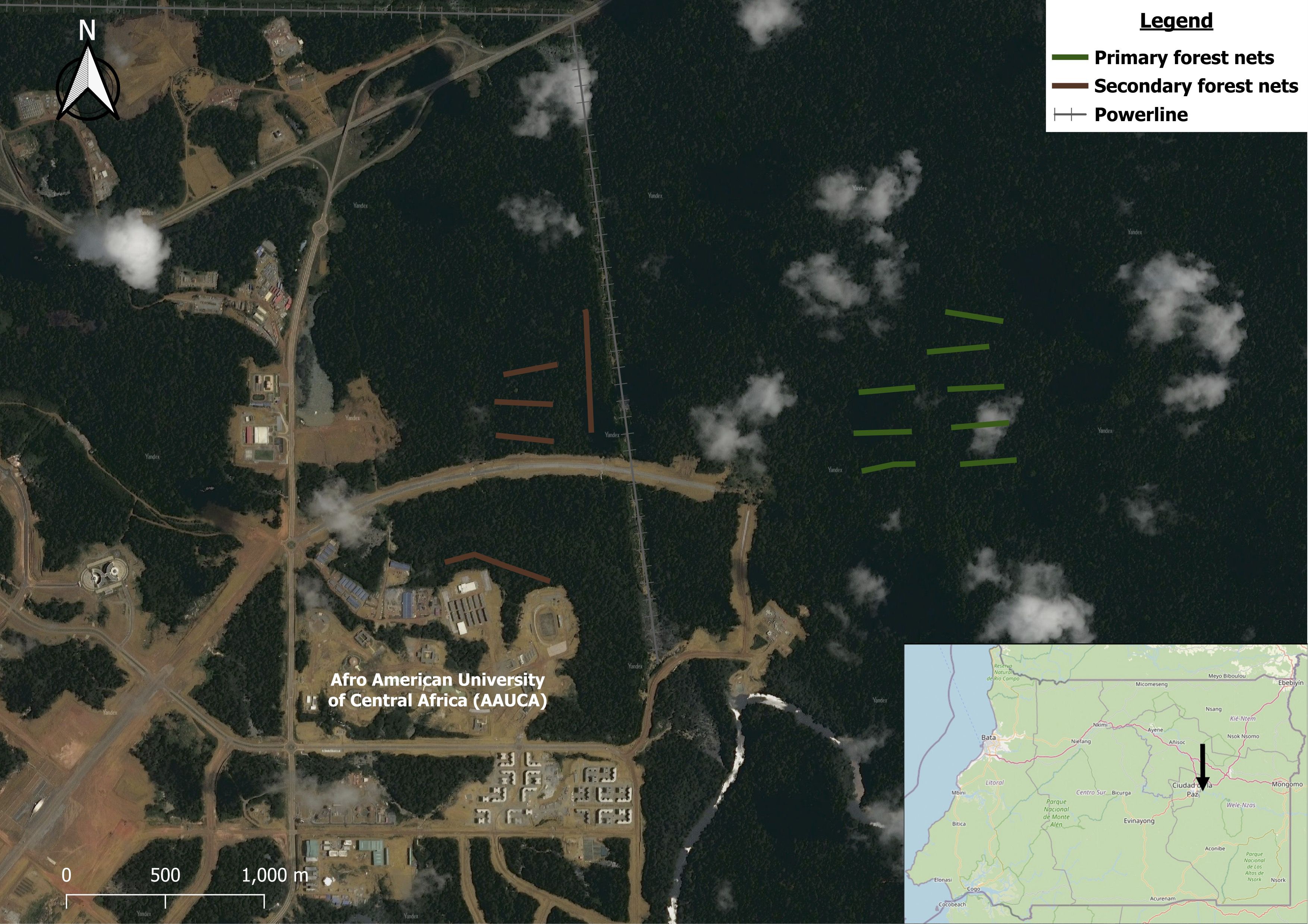

We carried out this research in lowland rainforest adjacent to the city of Ciudad de la Paz on the border between the Wele-Nzas and Centro Sur provinces of mainland Equatorial Guinea. Our study sites consisted of two ca. 70 ha plots in tall, closed canopy forest within walking distance of the AfroAmerican University of Central Africa (Figure 1). The plots have revealed no recent evidence of forest elephants during our work (i.e., no footprints, no camera trap images), but otherwise the full complement of Central African mammal fauna exist on the immediate landscape (Murai et al., 2013; DeGroot, 2024). The primary forest plot is in minimally disturbed primary forest that was lightly selectively logged through the 20th century and as late as the 1980s. Effectively all the lowland tropical rainforest in Equatorial Guinea has been at least lightly selectively logged, so we believe this primary forest plot to represent a reasonable baseline. The primary forest plot lies in the northernmost portion of a continuous block of several hundred thousand hectares of forest, broken only by a handful of lightly traveled roads; the closest road to this plot lies 500 m to the west. The secondary forest plot remains closed-canopy forest, but has been regularly selectively logged for decades, with the last harvests (especially of Okume Aucoumea klaineana) occurring in about 2017. Most of the secondary forest plot was isolated in the 2000s during the construction of the new capital city: by 4lane paved roads to the north and west, a large (~50 m wide) dirt road to the south, and high-voltage power lines to the east (~30 m wide gap with regularly trimmed vegetation ~2–3 m tall); this effectively created a forest fragment of ~250 ha with considerable edge habitat and regenerating canopy gaps (Andrews, 1990; Strevens et al., 2008). Canopy height above our nets was similar between the two plots where we netted, including average canopy height (primary: 14.1 ± 0.5 m SE; secondary 14.1 ± 0.4 m SE), and height of emergent trees (primary: 27 ± 0.9 m SE; secondary 27 ± 0.7 m SE); canopy cover and visibility through the understory were slightly higher in the primary plot (canopy cover: primary: 88 ± 1.3 m SE; secondary 83 ± 2.2 m SE; visibility: primary: 9.5 ± 0.5 m SE; secondary 7.5 ± 0.4 m SE)—which were probably a result of dense treefall gaps that were recovering from selective logging.

Figure 1. Distribution of net lanes in primary and secondary forest near Ciudad de la Paz, Equatorial Guinea. Satellite imagery: “Yandex Satellite 2022”sourced from https://core-sat.maps.yandex.net/tiles?l=sat&v=3.1025.0&x={x}&y={y}&z={z}&scale=1&lang=ru_RU using plugin “quick maps” in QGIS version 3.38.2. The inset map shows the field site location within continental Equatorial Guinea. © OpenStreetMap contributors, available under the Open Database License (see https://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright).

2.2 Data collection

We sampled understory birds using mist-nets between 2016–2023 during the sunny dry season (December–February/March), as well as once in July 2022 (the cloudy dry season). We did not sample during the rainy season due to the impracticality and animal welfare issues of carrying out fieldwork/mist-netting in heavy rain. Mist-net lanes (hereafter “lanes”) run in one morning was our sample unit; these lanes consisted of linear transects of typically 20 nets (12 x 2.5 m, 36-mm mesh; Figure 1). The number of nets per lane varied somewhat due to logistical constraints, treefall gaps etc; the mean number of nets per lane was 21.29 ± 0.99 SE. We ran eight lanes in the primary forest plot (N = 160 nets); this locality accounted for 11,070 mist-net hours (hours of operation x no. mistnets). In the secondary forest plot, we ran five net lanes (N = 145 nets), which accounted for 8807 mist-net hours. These differences in net lane length and effort between plots were accounted for during the modelling (see below). We sampled each net lane for two consecutive days each year and approximately six hours per day from ca. 06h30–12h30. The number of net lanes that we sampled on any given day was dependent on the number of field crew present. We adjusted effort when faced with poor weather conditions (e.g., heavy rain). Net lanes were separated by at least 200 m to facilitate spatial independence (Hill and Hamer, 2004).

Three genera had species pairs that were challenging to identify in the hand to species level were lumped at the genus level; ongoing genetic analysis will aid future efforts. These three pairs were Phyllastrephus icterinus/xavieri (Icterine/Xavier’s Greenbul), Criniger calurus/ndussumensis (Redtailed/White-bearded Greenbul), and Illadopsis fulvescens/rufipennis (Brown/Pale-breasted Illadopsis). For ease of communication, these species pairs are included when referring to “species” throughout. Prior to any analysis, we removed all same-day recaptures of individuals (identified via band number) from the dataset.

2.3 Statistical analysis

2.3.1 Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling

To visualize bird community differences between forest types, we conducted a nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination analysis using the function “metaMDS” from the package “vegan” (Oksanen et al., 2020) in R (R Core Team, 2022). Raw count values were logtransformed to reduce spurious results driven by rare and/or hyper-abundant species. Species with less than five observations were removed from the dataset. We used Bray-Curtis distance estimates. A PERMANOVA was then conducted on the NMDS output using the function “adonis” from the package “vegan” (Oksanen et al., 2020) to determine if primary and secondary forest bird communities were significantly different.

2.3.2 Generalized linear mixed models

To determine if captures rates differed significantly between the primary and secondary forest plots, we fitted generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) to the data in R version 4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022). In these analyses, we included only our focal, species, which we defined as those caught >10 times such that statistical models were likely to converge. We classified these species into guilds (Table 1) based on diet composition obtained from EltonTraits1.0 (Wilman et al., 2014), field observations, and species accounts in Birds of the World (Billerman et al., 2022).

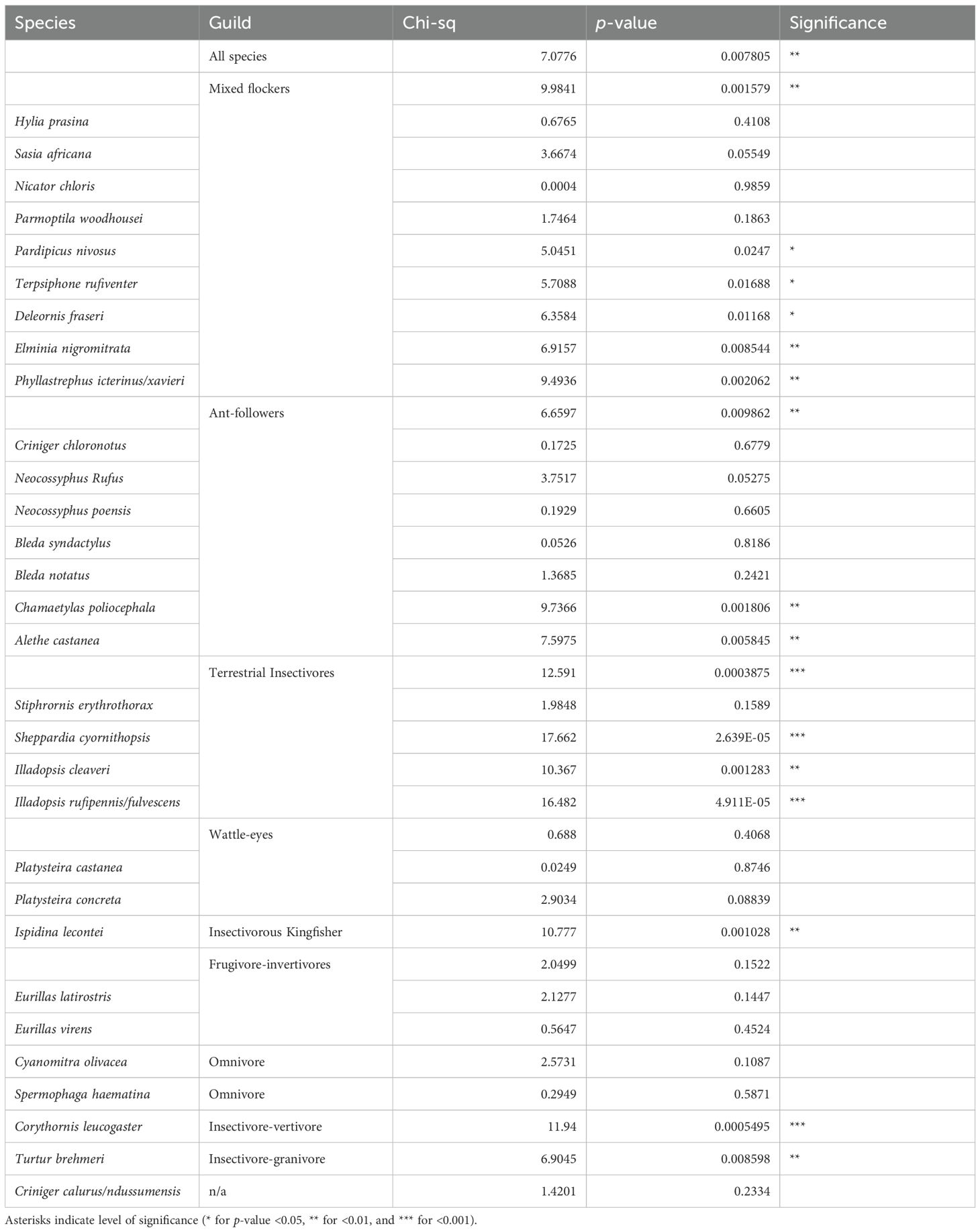

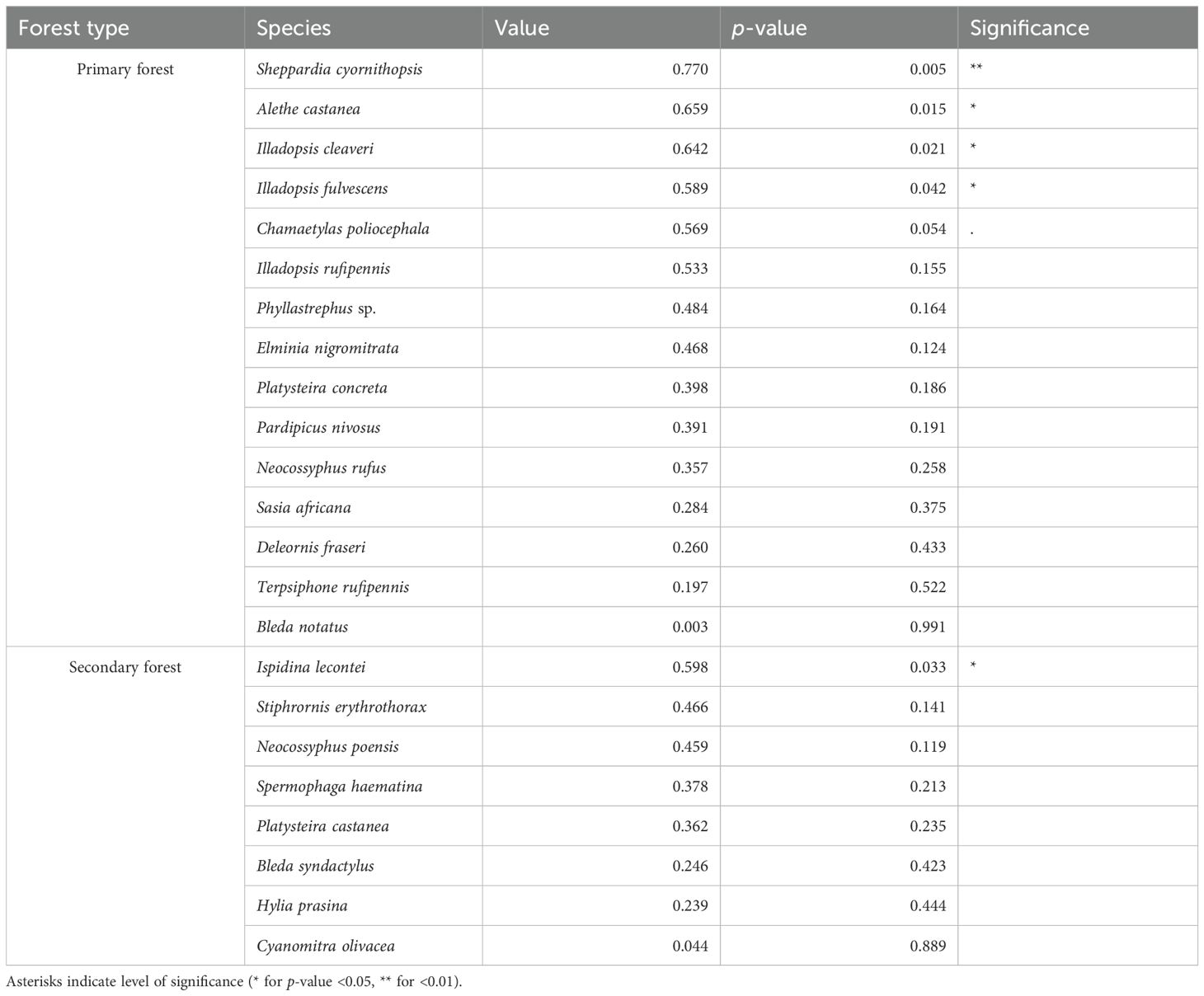

Table 1. Summary of the results of model selection for the guilds and species analysed—specifically the chi-squared value and p-value obtained from comparison, via likelihood ratio test, of models with and without forest type as an explanatory variable. A p-value of <0.05 indicates that the model containing forest type is the better fit. In nearly all cases of a significant difference between forest types, capture rate was higher in primary forest; the lone exception was Ispidina lecontei, which showed the opposite pattern.

We fitted separate models to the data for each guild and species, using the package glmmTMB (Brooks et al., 2017), with a negative binomial distribution to account for overdispersion in count data. For each model, we used number of captures per net lane/per day (“capture rate”) as the response variable. “Forest type” (primary vs secondary) and “Day” were included in the models as fixed effects. “Day” refers to day 1 vs day 2 of back-to-back sampling at each net lane within each field season—to account for the typical ~30% decline in capture rates that banders see on the second consecutive netting day in the same location (L.L.P., J.D.W. pers obs.). Field season was included as a random effect to account for inter-annual variation and net lane was included as a random effect to account for variation associated to specific lane location.

In addition to the random effect of net lane, we sought to further account for potential spatial autocorrelation between lanes by applying a penalty for lanes located near other net lanes using the “offset” function in the GLMM. In other words, we adjusted the baseline level of the response variable to be lower for lanes close to other lanes that were less spatially independent, and higher for more spatially isolated lanes. To appropriately calibrate this offset at the correct spatial scale (i.e., the scale at which birds move), we first used our georeferenced recapture data to quantify the maximum distance that individual birds typically moved. Across individuals, the mean maximum distance between recaptures was 238 ± 25 m 95% CI. From this, we conservatively took the high end of the 95% CI (263 m) and used it to draw a 263 m “buffer zone” around each net lane. For each net lane, the number of other net lanes that fell within its buffer zone (i.e., the amount of overlap) was used to create a proportion (1/overlap), which was used as the offset. Using this method, individual net lanes that were closest to each other and had more overlap with the buffer were penalized most by the offset as they had a lower baseline level for the response variable. An offset for net hours per net lane per day was also included to account for varying effort among lanes. For each guild and species, backwards stepwise model selection was carried out using likelihood ratio tests. In two cases, the random effect of field season had to be removed from models to facilitate model convergence. Thus, for Turtur brehmeri and Hylia prasina, inter-annual variation is not accounted for in the results.

2.3.3 Indicator analysis

We conducted an indicator species analysis using the package “indicspecies” (De Cáceres and Legendre, 2009) to identify the species that were significantly associated with primary and secondary forest. This test allowed us to determine the ecological “preferences” of species among a set of alternative site groups (i.e., sites within each forest type) and to associate their species distribution patterns with these groups of sites (De Cáceres and Legendre, 2009). Hence, these species can be considered as proxies to evaluate community integrity within each forest type. We calculated the association index value (“r.g”) using 10,000 permutations and standardized captures by per 1000 mist-net hours. This analysis did not include data from the most recent field season.

3 Results

We captured 2090 individuals in primary forest during 11,070 net hours (0.19 birds per net hour) and 1133 individuals in secondary forest during 8807 net hours (0.13 birds per net hour). Of the 78 species captured, 22 were exclusively caught in primary forest and 15 were exclusively caught in secondary forest (Supplementary Table S1). We calculated the Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index for each plot, which was roughly equal between the two (H’ = 2.98 in primary and H’ = 2.89 in secondary). We carried out statistical analyses for 30 focal species caught more than 10 times (37% of all species caught and 95.5% of all captures). All species were caught in both forest types, except for Ispidina lecontei (African Dwarf Kingfisher), which was caught exclusively in secondary forest (although we did detect this species visually on several occasions in the primary forest plot). Only three individuals of three species—Spermophaga haematina (Western Bluebill), Indicator maculatus (Spotted Honeyguide), and Eurillas latirostris (Yellow-whiskered Greenbul)—moved between primary and secondary forest plots. The species not included in our analyses (i.e., those captured less than 10 times) likely included canopy or mid-story species (such as Pogoniulus atroflavus, I. maculatus, and Stelgidillas gracilirostris) as well as a few migrant species. Considering only these focal species, we had 1999 captures in primary forest and 1078 captures in secondary forest.

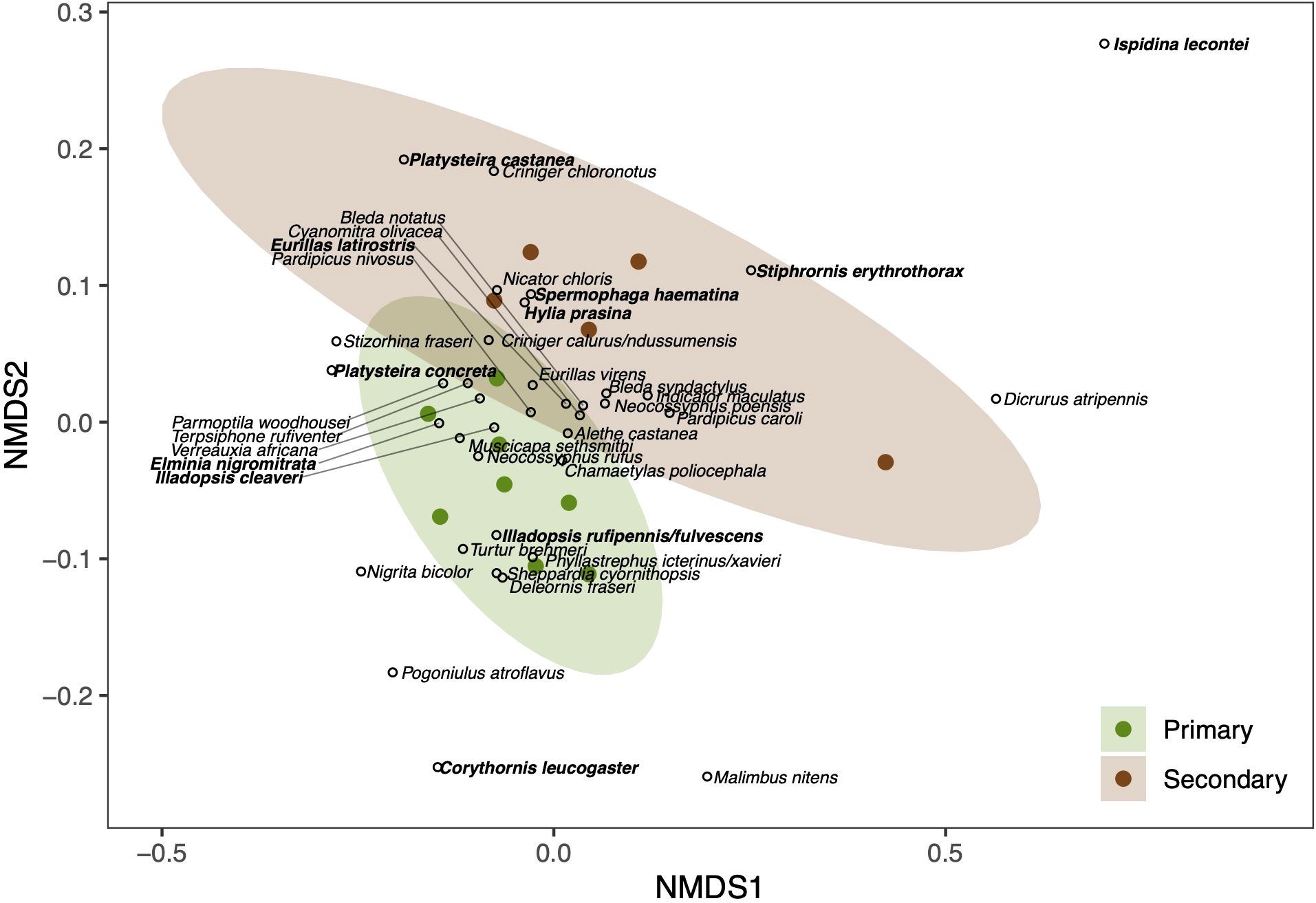

Despite a broad overlap in species composition and canopy cover between forest types, our NMDS ordination indicated that the community composition in primary forest was significantly different from that of secondary forest (F= 5.6936, P= 0.0035, R2 = 0.34106, Figure 2). Alethe castanea (Firecrested Alethe), Chamaetylas poliocephala (Brown-chested Alethe), and Illadopsis cleaveri (Blackcap Illadopsis) were central to the primary forest NMDS ellipse, suggesting that they were most representative of the primary forest community. Hylia prasina (Green Hylia), Platysteira castanea (Yellow-bellied Wattle-eye), and Spermophaga haematina (Western Bluebill) were central representatives of secondary forest.

Figure 2. Ordination plot using non-metric multidimensional scaling that significantly separates the community into species representing primary forest and those representing secondary forest. Each open dot represents a species, and the ellipses represent the 95% confidence interval about the estimate in multivariate space. Bolded species names indicate species significant at the 5% level.

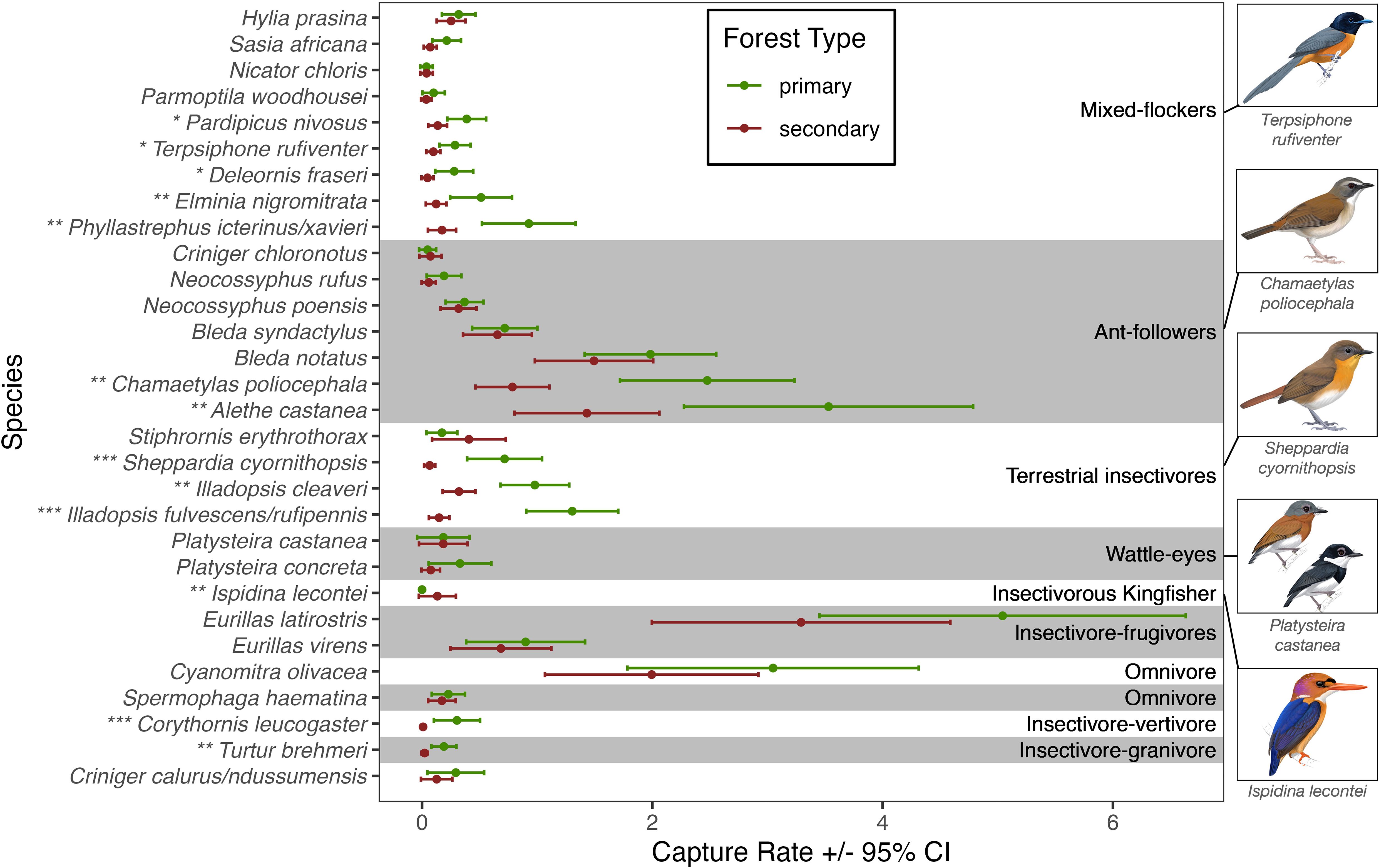

Based on a GLMM that included all species, capture rates were 47.3% lower in secondary forest overall. When modeling guild-level differences using GLMMs, we estimated that ant-followers, terrestrial insectivores and mixed-flockers had significantly higher capture rates in primary than in secondary forest, with 1.9-, 3.3-, and 2.8-times increases, respectively (Table 1). Wattle-eyes showed no significant difference in capture rate between forest types.

Several insectivorous species appeared to be driving the guild-level trends (Table 1, Figure 3). Of the ant-followers, Alethe castanea and Chamaetylas poliocephala were captured ca. 2.5 and 3 times more frequently, respectively, in primary forest than in secondary forest. Conversely the antfollowers Bleda notatus (Lesser Bristlebill), Bleda syndactylus (Red-tailed Bristlebill), Neocossyphus poensis (White-tailed Ant-Thrush), N. rufus (Red-tailed Ant-Thrush), and Criniger chloronotus (Eastern Bearded Greenbul) showed no such difference.

Figure 3. Capture rates of focal species in primary and secondary rainforest in Equatorial Guinea, based on the output of mixed models. Asterisks indicate significantly different capture rates between primary and secondary (* for p-value <0.05, ** for <0.01, and *** for <0.001). A p-value of <0.05 indicates that the model containing forest type was the better fit. Capture rate refers to number of birds captured per net lane (mean 21.29 nets per lane) per ~6 hour morning of netting. Artwork by Faansie Peacock, commissioned by Biodiversity Initiative.

Except for Stiphrornis erythrothorax (Orange-breasted Forest Robin), all species of terrestrial/nearground insectivores had significantly higher capture rates in primary than in secondary forest; eleventimes higher for Sheppardia cyornithopsis (Lowland Akalat), nine-times higher for Illadopsis fulvescens/rufipennis, and three-times higher for Illadopsis cleaveri.

Of the mixed-flockers, Phyllastrephus icterinus/xavieri, Elminia nigromitrata (Dusky Crested Flycatcher), Pardipicus nivosus (Buff-spotted Woodpecker), Terpsiphone rufiventer (Red-bellied Paradise-Flycatcher), and Deleornis fraseri (Fraser’s Sunbird) all had significantly higher capture rates in primary forest (five, four, three, three, and six times higher, respectively). The remaining mixed-flockers showed no significant differences in capture rates between habitats. Turtur brehmeri (13/15 captures in primary), a species that consumes both invertebrates and seeds, and Corythornis leucogaster (White-bellied Kingfisher; 26/27 captures in primary), a species that consumes invertebrates and fish or small ectotherms, both had significantly higher capture rates in primary forest. Ispidina lecontei was the only species for which we found significantly higher capture rates in secondary forest (Table 1, Figure 3).

The indicator species analysis showed that Sheppardia cyornithopsis, Illadopsis cleaveri, and Illadopsis fulvescens (terrestrial insectivores) as well as Alethe castanea (an ant-follower) were significant indicators of primary forest. One species (Ispidina lecontei) was a significant indicator of secondary forest (Table 2).

Table 2. Results from the indicator species analysis for the 23 bird species present in the primary and secondary forest; association index value of 1 suggests a strong association with a given forest type.

4 Discussion

4.1 Interpretation of results

Despite the superficial similarity of species richness between our two focal forests, the avian community responded substantially to forest disturbance in terms of relative abundances and community composition. We regularly caught more birds in the primary forest overall: we caught 85% more birds in the primary forest with just 26% more effort; correcting for effort, we caught 46% more birds in primary forest (Supplementary Table S1). Terrestrial insectivores, ant-followers, and mixed-flockers had higher captures rates in primary than in secondary forests, as did Turtur brehmeri (insectivoregranivore) and Corythornis leucogaster (insectivore-vertivore). Terrestrial insectivores appeared to be the guild most sensitive to disturbance, as indicated by the magnitude of differences in capture rates and the proportion of species driving the trend (4/5). Considering the mixed models, ordination and indicator analysis, the species that appear most representative of primary forest are the antfollowers Alethe castanea and Chamaetylas poliocephala as well as the terrestrial insectivores Sheppardia cyornithopsis, Illadopsis cleaveri and Illadopsis fulvescens/rufipennis. The insectivorous kingfisher Ispidina lecontei appears to be the lone representative of secondary forest.

There could be several mechanisms behind the response of terrestrial insectivores to disturbance and habitat degradation. Arthropod availability may be lower in secondary forest, although we cannot say this for certain as we did not measure arthropod abundance in this study. Hypothetically, arthropod availability in general may even be higher in secondary forests or may vary climatically (as Wolfe et al., 2025 suggest), for example due to a dry El Niño year, as was the case in 2016. Further investigation of arthropod abundance at our study site is ongoing, and exploration of seasonal variation would be valuable in future work (see section 4.2). Alternatively, or additionally, foraging tactics may be impacted due to changes in vegetation and light intensity or edge effects from fragmentation (Barlow et al., 2002; Laurance et al., 2002; Powell et al., 2015). For example, a denser understory in secondary forest due to increased light may make it harder for terrestrial insectivores to move along the forest floor and use specialized foraging tactics, as seen with understory insectivores in Australian tropical forests (Pavlacky et al., 2015). Stouffer et al. (2021) noted that, due to their foraging habits, Amazonian terrestrial insectivores are more restricted to specific microhabitats than other insectivores such as ant-followers. At that same site, terrestrial insectivores selected cooler microclimates (Jirinec et al., 2022b), likely exhibiting thermal niche tracking. Further, terrestrial insectivores selected forest microhabitats with denser canopy cover during the dry season (Jirinec et al., 2022a). These results suggest that microclimate warming and homogenization in degraded and fragmented forest may limit the occupancy of secondary forest by terrestrial insectivores. Again in Amazonia, Stouffer and Bierregaard (1995) found that insectivorous guilds declined in abundance and diversity after timber harvest. Additionally, they found that terrestrial insectivores did not show marked recovery over time. Our secondary forest plot could essentially be considered a ~250 ha fragment, being effectively isolated by roads and a powerline, as opposed to the primary plot which is within continuous forest. Powell et al. (2013) showed in the same system as that of Stouffer and Bierregaard (1995) that terrestrial insectivores in secondary forest fragments took the longest to recover to pre-isolation capture rates, with a projected recovery time of 61 years compared to 26 years for all 10 foraging guilds studied. Although the commonly captured terrestrial insectivores in our Afrotropical site may have broader foraging strategies than those in Amazonia and are not strictly confined to a particular stratum (for example Illadopsis fulvescens sometimes forages up to 12 m from the ground (Collar and Robson, 2020), they still rank among the most terrestrial species in Afrotropical forests. Disconcertingly, the impacts of forest degradation on terrestrial insectivores seen in our results may be an under-estimation of the reality. Stouffer et al. (2021) found that even in a vast block of undisturbed, continuous primary forest in the Amazon, the abundance of terrestrial insectivores was significantly lower compared to several decades prior. These concerning trends could partly be attributed to the effects of global climate change (Wolfe et al., 2025), raising the question of whether the baseline against which we are comparing is itself representative of a healthy ecosystem.

Of our focal terrestrial insectivores, the near-ground Sheppardia cyornithopsis showed the strongest contrast in capture rates between primary and secondary forest—just 10 of 83 captures were in the secondary forest (Supplementary Table S1). Sheppardia cyornithopsis typically perch 0.5–2 m from the ground and forage for insects by sallying or by sally-gleaning to the ground or tree trunks (Collar, 2020), a foraging strategy that may be inhibited by dense understories. This would reflect the findings of Arcilla et al. (2015), who found that insectivores that foraged by sallying were more sensitive to logging in the Upper Guinean Forest. Also, among terrestrial insectivores, we found that all three secretive, near-ground insectivores in the genus Illadopsis were quite sensitive to disturbance: I. cleaveri, and I. rufipennis/fulvescens both had significantly higher capture rates in primary than in secondary forest (only 28 of 97 captures and 16 of 115 captures were in secondary forest, respectively). Thus, Illadopsis may act as good indicators of changing habitat conditions and quality of tropical forest habitat in Lower Guinea Forests. We define the term “indicators” above, and consider the limitations of generalizing this in section 4.2. Unfortunately, it is very challenging to morphologically distinguish between I. fulvescens and I. rufipennis, so we grouped the two for this analysis. Similar field identification issues apply to two flocking greenbul genera: Phyllastrephus icterinus/xavieri and Criniger ndussumensis/calurus. In all three cases of difficult-to-distinguish species, the behaviors and natural histories of these congeners are quite similar (Borrow and Demey, 2014; Billerman et al., 2022), so it is reasonable to expect similar patterns of sensitivity to disturbance. Further research using molecular markers and multiple, fine-scale morphological measurements is ongoing and will aid species-specific conclusions for these six species in the future (Billerman et al., 2022).

Capture rates of the ant-followers were driven by the terrestrial Muscicapids, Alethe castanea and Chamaetylas poliocephala, both of which are often found foraging together and likely have similar natural histories and are regular followers of driver ants (genus Dorylus; Peters and Okalo, 2009; Craig, 2022; Rodrigues, 2024). The decline of ant-followers in secondary forest is likely driven by the abundance of driver ant swarms (Peters and Okalo, 2009). In the Neotropics, army ants (Eciton burchellii) and ant-following birds are sensitive to habitat degradation and fragmentation (Harper, 1989; Stouffer and Bierregaard, 1995; Roberts et al., 2000; Kumar and O’Donnell, 2007). Among the few to work on ant-following birds in Africa, Peters et al. (2008) and Peters and Okalo (2009) found that, in Kenya, ant-following birds were limited by the abundance of Dorylus wilverthi driver ants in fragmented landscapes (again, our secondary forest plots is effectively a forest fragment). Further, the presence of more disturbance-tolerant driver ants D. molestus did not compensate for D. wilverthi declines, suggesting that even subtle changes in driver ant communities can drive declines in specialized ant-followers. Similar mechanisms could be driving ant-follower declines at our site, possibly due to reduced foraging opportunities for birds. This could result from overall declines in arthropod prey or driver ant abundance and swarming rates due to increasingly drier conditions. Climatic factors may have an impact (Wolfe et al., 2025), as the driver ants may be exposed to higher temperatures and lower humidities in secondary forests. Alternatively, our site likely contains three main species of swarming Dorylus driver ants (Max P.G.T. Tercel, unpublished data), and these may have species-specific responses to disturbance. For example, Peters and Okalo (2009) found that specialized ant-followers were more dependent on D. wilverthi, which had more stable activity independent of humidity levels than D. molestus. The driver ants at our study site remain poorly understood, but future studies should focus on the distribution, behavior and foraging ecology of driver ant species in West and Central Africa, as well as their connection with forest degradation and declines of ant-following birds. The effective isolation of our secondary forest plot by roads and power lines may also contribute to the lower capture rates of ant-followers seen in secondary forest, as the thermal tolerances of Dorylus ants may prevent their movement into disturbed (sunny) areas. Jirinec et al. (2022b) found that light intensity (and corresponding heat) in areas of natural disturbance from treefall reached over 40 times that of the forest interior. However, it is not clear if low vegetation found under the power lines (2–3m as of 2023) or nocturnal movements could compensate for these impediments in our study area.

Other recent studies from the Afrotropics have also shown sensitivity of ant-followers to human landuse. For example, Ocampo-Ariza et al. (2019) identified an extinction threshold for ant-following birds at 24% forest cover along a disturbance gradient, with the most sensitive species disappearing below 52% cover. Jarrett et al. (2021) found that ant-followers were captured at least three times more commonly in primary forest (including our study site) compared to well-shaded cocoa plantations. Further, Miller et al. (2021) found that insectivores on Bioko Island—particularly antfollowers including Alethe castanea—showed reduced capture rates along roads relative to forest interiors at low elevation. Further, our own preliminary fieldwork carried out in 2014 in Nsork National Park (230 captures in 17 lanes of 6 nets), about 65km southeast of our study site, resulted in Alethe castanea being captured 11 times in primary forest and 3 times in secondary. Another of our primary forest indicators, Sheppardia cyornithopsis was captured 3 times in primary forest in Nsork but never in secondary (site description in Cooper et al., 2016; capture data unpublished). Indeed, the scope of this Nsork study was small, but together with other studies from the region, largely helps to corroborate the findings in our study here. Useful future work on ant-followers could include investigation of home range sizes and whether this contributes fragmentation sensitivity as is the case for ant-following birds in the Neotropics (Ferraz et al., 2007).

The effects of forest degradation on mixed-flock species shown in our results were practically as stark as those for ant-followers and terrestrial insectivores. Five of seven focal species showed significantly more captures in primary forest, with the largest effect sizes found in the flycatcher E. nigromitrata and the greenbul P. icterinus/xavieri. In contrast, Powell et al. (2013) found that in Amazon rainforest recovering from fragmentation, mixed-flock species were relatively quick to reach pre-isolation capture rates in comparison to sensitive guilds such as terrestrial insectivores. There are few mixed-flock studies from the Afrotropics (but see Cordeiro et al., 2015, 2022), thus most of our understanding of mixed-flock systems is from the Neotropics. There, species richness, and size and stability of flocks, decreases with forest fragment size and increases with mean vegetation height, with flocks being reluctant to cross open roads or enter open areas (Stouffer and Bierregaard, 1995; Thiollay, 1997; Develey and Stouffer, 2001; Maldonado-Coelho and Marini, 2004; Mokross et al., 2018). Also, flock interaction networks are sensitive to fragmentation and increasing proportions of secondary forest (Mokross et al., 2014). In Asia mixed-species flocks are sensitive to human-land use and are particularly dependent on the flock leader species (Lee et al., 2005; Mammides et al., 2015). These ecological dynamics are poorly known and ripe for future investigation with Afrotropical mixed-flockers.

The only species we captured significantly more often in secondary forest was the insectivorous kingfisher Ispidina lecontei. These kingfishers are generally found in secondary forest, at forest edges, as well as in other open areas such as forest clearings. They forage by diving from a low perch and catching their prey in flight or on the ground (Woodall, 2020). This species was also caught more often in cocoa plantations than in mature forest in Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea, corroborating our findings (Jarrett et al., 2021).

Several previous studies have found that nectarivores, frugivores and granivores tend to be positively affected by forest degradation (Waltert et al., 2005; Holbech, 2009), probably due to the increased light levels promoting the production of flowers, fruit and grains. We captured relatively few members of these guilds so had little power to test these predictions in the Afrotropics. These low capture numbers were likely due (at least partly) to a bias against the capture of species that are typically located in the canopy or in between stratum, as these species are less likely to be captured in mist-nets. This applies not only to frugivores but any species that are not exclusive to lower strata. A reliable comparison of capture rates between primary and secondary forest for such species would require additional surveying using other methods such as point counts and acoustic surveys. The dove Turtur brehmeri (an insectivore-granivore) was captured significantly less in secondary forest. Three widespread, common and versatile species—Eurillas latirostris (Yellow-whiskered Greenbul), Eurillas virens (Little Greenbul) and Cyanomitra olivacea (Olive Sunbird)—showed no significant differences in capture rate between primary and secondary forest. Future studies should use point counts and acoustic recording devices to properly evaluate the responses of these guilds to forest degradation.

Finally, we provide strong evidence that overall, fewer birds are captured in secondary forest (47.3% less), with few species appearing to disappear entirely; rather, many were simply caught much less frequently. The species that did disappear entirely from primary forest were all caught less than ten times, suggesting the pattern in those less-captured species is driven by sample size. This pattern hints that the local extirpation of many of these species may be more gradual in Central Africa compared to Amazonia, where the most sensitive species often disappear entirely with disturbance (Stouffer et al., 2021). However, it is important to note that our study only compares two study plots, and only by pairing our results with those from other similar studies (see above) can we begin to determine if our results are broadly generalizable. We speculate that this potential difference in sensitivity from Amazonian birds may have to do with biogeographical context: Amazonian birds have spent at least the last 2.6 million years (i.e., through the Pleistocene) evolving in a vast expanse of tropical rainforest (Bush, 1994; Rull, 2008); conversely, their African counterparts have had to adapt (or not) to the repeated Pleistocene ebb and flow of rainforest and savanna on their continent (Maley, 1996; Voelker et al., 2010). African rainforests may have shrunk into a few isolated refugia dozens of times during this epoch—creating an evolutionary filter unlikely to favor the rainforestrestricted species. An alternative, but not mutually exclusive explanation is that these differences could have derived from the management history of the secondary forest. The secondary forest at our site was repeatedly selectively logged and fragmented by roads and a powerline-cut (the powerline left ~2–3m vegetation underneath), and left many large trees and a closed canopy within the plot; in contrast, the secondary forest at the Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project—where much Amazonian research was performed, regrew from abandoned clearcuts that once created hard barriers to animal movement (e.g., Stouffer et al., 2021). Future work should carefully consider the effect of secondary forest management and fragmentation per se when quantifying effects on the bird community.

4.2 Study limitations and further research

There are several limitations to this study which could impact interpretation of the results, and present avenues to explore further in future research. Firstly, we only carried out sample collection in the dry seasons due to practical and ethical considerations, as explained in Section 2.2. Future work could examine patterns across seasons and climatic variables, potentially using different methods such as point counts. We catch negligible numbers of Palearctic migrants at our study site but work across seasons could help us adjust for local seasonal movements and intra-Africa migrants. Our study also only consisted of two plots, meaning that our ability to generalize our findings hinges on comparisons to other studies as discussed above. For similar reasons and because we only sampled two habitat types, we limited in making inferences about species as potential “indicators”. The methods that we used (mist-netting at near-ground level) also present limitations and potential bias in the species caught. Canopy species (such as certain frugivorous—especially hornbills—and nectarivorous species) and large ground-dwelling birds (e.g., francolins) are surely under-represented in our samples, and so we cannot make reliable conclusions about these groups. Future work using additional methods such as point counts or acoustic surveys would allow for further investigation of these species. We collected much acoustic data while netting but due to logistical constraints, we did not analyze those data here. Our net lanes were separated by at least 200m, which certainly reduced spatial autocorrelation (Hill and Hamer, 2004), but did not eliminate it as some individuals could certainly travel farther than this distance. However, we believe we appropriately accounted for this autocorrelation by systematically decreasing the influence of especially autocorrelated net lanes in our analysis (see methods). Further, we also grouped some morphologically similar species that could not be distinguished in the field (e.g. Phyllastrephus icterinus and P. xavieri). DNA barcoding combined with high resolution morphological data be a useful tool to avoid any potential dilution of species-specific effects. Finally, although we have proposed and discussed potential mechanisms driving the patterns seen here, we did not measure variables such as arthropod abundance, microhabitat vegetation structure, or environmental variables (temperature, light intensity etc.), thus would be valuable to explore these hypothetical drivers in future studies.

4.3 Conservation and management

Overall, our study indicates that the threat posed by forest degradation may be disproportionately high for certain bird guilds, such as terrestrial insectivores, ant-followers, and mixed-species flockers. Given that deforestation rates are still extremely high in the Congo Basin, it is essential to improve our understanding of consequences for biodiversity and potential mitigation measures. For example, 1,899,000 hectares of forest per year were removed between 2015–2020 in Western and Central Africa (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 2020), The species and guilds that we have identified here as being particularly sensitive could potentially act as indicator species for forest quality in this region with their absence. However, further study across other sites and habitats are needed to investigate this further. The absence of these “indicators” signals a loss of habitat quality that could negatively impact not only birds, but the entire ecosystem upon which they depend (e.g. keystone Dorylus ants). Other research supports our findings with respect to indicator species, most of which have ranges that extend across much of Central Africa, so we believe our results are mostly generalizable across a poorly studied region. Future work should focus on determining what specific mechanism is driving these declines, be that climate food availability, vegetation and microhabitat structure, depredation risk, light regime, or a combination of these. Further work on demography (see Nikolaou et al., 2024 in this Research Topic) would allow investigation beyond capture rates to understand population dynamics and thus infer habitat quality among forest types. With the knowledge of the sensitive species presented here and a better understanding of the mechanisms for these declines, concrete conservation actions can be taken to mitigate the negative anthropogenic effects of continuous forest degradation and disappearance.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: FigShare, https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Data_for_analysis_in_Barrie_et_al_2025_/29114960.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (17-18.W.06-A.) at Humboldt State University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

EB: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BK: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CJ: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DF: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PR: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SLM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SEM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AA: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. CA: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. KB: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration. JC: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JW: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology. LP: Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. LLP was supported by Durham University, a Marie Curie award and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 854248 during the preparation of this manuscript. EB was supported by The University of Glasgow during the preparation of this manuscript. For their financial support, we thank donors to our Kickstarter campaign, Stonehill Education, The Polistes Foundation, National Geographic, The University of Glasgow (IBAHCM), and the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank INDEFOR-AP – particularly director Don Fidel Esono – for facilitating permissions and logistics. We thank Bioko Biodiversity Protection Program for their logistical support as well as AAUCA and UNICON for allowing us to use their facilities adjacent to the research plots. We thank Heidi Ruffler, the Universidad Nacional de Guinea Ecuatorial and the US Embassy in Malabo for various contributions. We thank, Joris Wiethase, Andrew Weigardt, Amancio Motive, Jose Rufino Mitogo Ada, Laura Torrent, Matthew “Di-hydrogen Monoxide” Brooks, Miguel Angel Fuentes Rosúa, Henry Pollock, Phil C Stouffer, George V.N. Powell and many others for their banding and trail-cutting contributions in the field. We thank Doumnbia and Rama for their help with housing and logistics. We thank Panagiotis Nikolaou for producing and contributing the map in Figure 1. Finally, we give our thanks (akiba) to the Fang communities who allowed us access to their local forests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2025.1504350/full#supplementary-material

References

Andrews A. (1990). Fragmentation of habitat by roads and utility corridors: A review. Aust. Zool. 26, 130–141. doi: 10.7882/AZ.1990.005

Arcilla N., Holbech L. H., and O’Donnell S. (2015). Severe declines of understory birds follow illegal logging in Upper Guinea forests of Ghana, West Africa. Biol. Conserv. 188, 41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.02.010

Baccini A., Goetz S. J., Walker W. S., Laporte N. T., Sun M., Sulla-Menashe D., et al. (2012). Estimated carbon dioxide emissions from tropical deforestation improved by carbon-density maps. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 182–185. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1354

Barlow J., Haugaasen T., and Peres C. A. (2002). Effects of ground fires on understorey bird assemblages in Amazonian forests. Biol. Conserv. 105, 157–169. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00177X

Barlow J., Peres C. A., Henriques L. M. P., Stouffer P. C., and Wunderle J. M. (2006). The responses of understorey birds to forest fragmentation, logging and wildfires: An Amazonian synthesis. Biol. Conserv. 128, 182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.028

Beier P., Van Drielen M., and Kankam B. O. (2002). Avifaunal collapse in West African forest fragments. Conserv. Biol. 16, 1097–1111. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.01003.x

Billerman S. M., Keeney B. K., Rodewald P. G., and Schulenberg T. S. (2022). Birds of the World (Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology).

Borrow N. and Demey R. (2014). Birds of Western Africa. 2nd ed. (London: Christopher Helm, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc).

Bregman T. P., Sekercioglu C. H., and Tobias J. A. (2014). Global patterns and predictors of bird species responses to forest fragmentation: Implications for ecosystem function and conservation. Biol. Conserv. 169, 372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.11.024

Brooks M. E., Kristensen K., Nan Benthem K. J., Magnusson A., Berg C. W., Nielsen A., et al. (2017). glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. The R Journal 9, 378–400. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2017-066

Brosset A. (1969). La vie sociale des oiseaux dans une forêt équatoriale du Gabon. Biol. Gabonica 5, 29–69.

Bush M. B. (1994). Amazonian speciation: A necessarily complex model. J. Biogeogr. 21, 5. doi: 10.2307/2845600

Chesser R. T. (1995). Comparative diets of obligate ant-following birds at a site in Northern Bolivia. Biotropica 27, 382. doi: 10.2307/2388923

Collar N. (2020). “Lowland Akalat (Sheppardia cyornithopsis),” in Birds of the World. Eds. del Hoyo J., Elliott A., Sargatal J., Christie D., and de Juana E. (Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell Lab of Ornithology). doi: 10.2173/bow.lowaka1.01

Collar N. and Robson C. (2020). “Brown Illadopsis (Illadopsis fulvescens), version 1.0,” in Birds of the World. Eds. del Hoyo J., Elliott A., Sargatal J., Christie D. A., and de Juana E. (Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell Lab of Ornithology). doi: 10.2173/bow.broill1.01

Cooper J. C., Powell L. L., and Wolfe J. D. (2016). Notes on the birds of Equatorial Guinea, including nine first country records. Bull. Afr. Bird Club 23, 152–163. doi: 10.5962/p.310083

Cordeiro N. J., Borghesio L., Joho M. P., Monoski T. J., Mkongewa V. J., and Dampf C. J. (2015). Forest fragmentation in an African biodiversity hotspot impacts mixed-species bird flocks. Biol. Conserv. 188, 61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.050

Cordeiro N. J., Rovero F., Msuha M. J., Nowak K., Bianchi A., and Jones T. (2022). Two antfollowing bird species forage with three giant sengi (Rhynchocyon) species in East Africa. Biotropica 54, 590–595. doi: 10.1111/btp.13101

Cox R. L. and Underwood E. C. (2011). The importance of conserving biodiversity outside of protected areas in mediterranean ecosystems. PLoS ONE 6, e14508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014508

Craig A. J. F. K. (2022). African birds as army ant followers. J. Ornithol. 163, 623–631. doi: 10.1007/s10336-022-01987-0

De Cáceres M. and Legendre P. (2009). Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology 90, 3566–3574. doi: 10.1890/08-1823.1

DeGroot T. L. (2024). Assessing Tropical Mammal Diversity and Distribution Using Noninvasive Methods (Houghton, Michigan: Michigan Technological University). doi: 10.37099/mtu.dc.etdr/1773

Develey P. F. and Stouffer P. C. (2001). Effects of roads on movements by understory birds in mixed-species flocks in central Amazonian Brazil. Conserv. Biol. 15, 1416–1422. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2001.00170.x

Di Marco M., Chapman S., Althor G., Kearney S., Besancon C., Butt N., et al. (2017). Changing trends and persisting biases in three decades of conservation science. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 10, 32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2017.01.008

Ferraz G., Nichols J. D., Hines J. E., Stouffer P. C., Bierregaard R. O., and Lovejoy T. E. (2007). A large-scale deforestation experiment: effects of patch area and isolation on amazon birds. Sci. (1979) 315, 238–241. doi: 10.1126/science.1133097

Ferreira D. F., Jarrett C., Wandji A. C., Atagana P. J., Rebelo H., Maas B., et al. (2023). Birds and bats enhance yields in Afrotropical cacao agroforests only under high tree-level shade cover. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 345, 108325. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2022.108325

Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (2020). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020. (Rome: FAO).

Gotwald W. H. (1995). Army ants: the biology of social predation. (Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell University Press).

Gray M. A., Baldauf S. L., Mayhew P. J., and Hill J. K. (2007). The response of avian feeding guilds to tropical forest disturbance. Conserv. Biol. 21, 133–141. doi: 10.1111/j.15231739.2006.00557.x

Hardy O. J., Born C., Budde K., Daïnou K., Dauby G., Duminil J., et al. (2013). Comparative phylogeography of African rain forest trees: A review of genetic signatures of vegetation history in the Guineo-Congolian region. Comptes Rendus. Géosci. 345, 284–296. doi: 10.1016/j.crte.2013.05.001

Harper L. H. (1989). The persistence of ant-following birds in small amazonian forest fragments. Acta Amazon. 19, 249–263. doi: 10.1590/1809-43921989191263

Hill J. K. and Hamer K. C. (2004). Determining impacts of habitat modification on diversity of tropical forest fauna: the importance of spatial scale. J. Appl. Ecol. 41, 744–754. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-8901.2004.00926.x

Holbech L. H. (2009). The conservation importance of luxuriant tree plantations for lower storey forest birds in south-west Ghana. Bird Conserv. Int. 19, 287. doi: 10.1017/S0959270909007126

Hubau W., Lewis S. L., Phillips O. L., Affum-Baffoe K., Beeckman H., Cuní-Sanchez A., et al. (2020). Asynchronous carbon sink saturation in African and Amazonian tropical forests. Nature 579, 80–87. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2035-0

Jarrett C., Smith T. B., Claire T. T. R., Ferreira D. F., Tchoumbou M., Elikwo M. N. F., et al. (2021). Bird communities in African cocoa agroforestry are diverse but lack specialized insectivores. J. Appl. Ecol. 58, 1237–1247. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.13864

Jirinec V., Elizondo E. C., Rodrigues P. F., and Stouffer P. C. (2022a). Climate trends and behavior of a model Amazonian terrestrial insectivore, black-faced antthrush, indicate adjustment to hot and dry conditions. J. Avian Biol. 2022, e02946. doi: 10.1111/jav.02946

Jirinec V., Rodrigues P. F., Amaral B. R., and Stouffer P. C. (2022b). Light and thermal niches of ground-foraging Amazonian insectivorous birds. Ecology 103, e3645. doi: 10.1002/ecy.3645

Jung M., Arnell A., de Lamo X., García-Rangel S., Lewis M., Mark J., et al. (2021). Areas of global importance for conserving terrestrial biodiversity, carbon and water. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1499–1509. doi: 10.1038/s41559-021-01528-7

Kumar A. and O’Donnell S. (2007). Fragmentation and elevation effects on bird–army ant interactions in neotropical montane forest of Costa Rica. J. Trop. Ecol. 23, 581–590. doi: 10.1017/S0266467407004270

Laurance W. F., Lovejoy T. E., Vasconcelos H. L., Bruna E. M., Didham R. K., Stouffer P. C., et al. (2002). Ecosystem decay of amazonian forest fragments: a 22-year investigation. Conserv. Biol. 16, 605–618. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.01025.x

Lee T. M., Soh M. C. K., Sodhi N., Koh L. P., and Lim S. L.-H. (2005). Effects of habitat disturbance on mixed species bird flocks in a tropical sub-montane rainforest. Biol. Conserv. 122, 193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2004.07.005

Maldonado-Coelho M. and Marini M.Â. (2004). Mixed-species bird flocks from Brazilian Atlantic Forest: the effects of forest fragmentation and seasonality on their size, richness and stability. Biol. Conserv. 116, 19–26. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00169-1

Maley J. (1996). The African rain forest – main characteristics of changes in vegetation and climate from the Upper Cretaceous to the Quaternary. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section B. Biol. Sci. 104, 31–73. doi: 10.1017/S0269727000006114

Malhi Y., Adu-Bredu S., Asare R. A., Lewis S. L., and Mayaux P. (2013). African rainforests: past, present and future. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 368, 20120312. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0312

Mammides C., Chen J., Goodale U. M., Kotagama S. W., Sidhu S., and Goodale E. (2015). Does mixed-species flocking influence how birds respond to a gradient of land-use intensity? Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 282, 20151118. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1118

McClure H. E. (1967). Composition of mixed species flocks in lowland and sub montane forests of Malaya. Wilson Bull. 79, 131–154.

Miller S. C., Wiethase J. H., Motove Etingue A., Franklin E., Fero M., Wolfe J. D., et al. (2021). Interactive effects of elevation and newly paved road on avian community composition in a scientific reserve, Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Biotropica 53, 1646–1663. doi: 10.1111/btp.13014

Mokross K., Potts J. R., Rutt C. L., and Stouffer P. C. (2018). What can mixed-species flock movement tell us about the value of Amazonian secondary forests? Insights from spatial behavior. Biotropica 50, 664–673. doi: 10.1111/btp.12557

Mokross K., Ryder T. B., Côrtes M. C., Wolfe J. D., and Stouffer P. C. (2014). Decay of interspecific avian flock networks along a disturbance gradient in Amazonia. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 281, 20132599. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2599

Morris R. J. (2010). Anthropogenic impacts on tropical forest biodiversity: a network structure and ecosystem functioning perspective. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 365, 3709–3718. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0273

Morse D. H. (1970). Ecological aspects of some mixed-species foraging flocks of birds. Ecol. Monogr. 40, 119–168. doi: 10.2307/1942443

Murai M., Ruffler H., Berlemont A., Campbell G., Esono F., Agbor A., et al. (2013). Priority areas for large mammal conservation in Equatorial Guinea. PloS One 8, e75024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075024

Newbold T., Scharlemann J. P. W., Butchart S. H. M., Şekercioğlu Ç.H., Alkemade R., Booth H., et al. (2013). Ecological traits affect the response of tropical forest bird species to land-use intensity. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 280, 20122131. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2131

Nikolaou P., Krochuk B. A., Rodrigues P. F., Brzeski K., Mufumu S. L., Malanza S. E., et al. (2024). Insights on avian life history and physiological traits in Central Africa: ant-following species have young-dominated age ratios in secondary forest. Front. In Conserv. Sci. 6. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1504320

Ocampo-Ariza C., Denis K., Njie Motombi F., Bobo K. S., Kreft H., and Waltert M. (2019). Extinction thresholds and negative responses of Afrotropical ant-following birds to forest cover loss in oil palm and agroforestry landscapes. Basic Appl. Ecol. 39, 26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2019.06.008

Oksanen J., Blanchet F. G., Friendly M., Kindt R., Legendre P., McGlinn D., et al. (2020). vegan: Community Ecology Package. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (Accessed March 31, 2025).

Pavlacky D. C., Possingham H. P., and Goldizen A. W. (2015). Integrating life history traits and forest structure to evaluate the vulnerability of rainforest birds along gradients of deforestation and fragmentation in eastern Australia. Biol. Conserv. 188, 89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.10.020

Pereira H. M., Navarro L. M., and Martins I. S. (2012). Global biodiversity change: the bad, the good, and the unknown. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 37, 25–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ042911-093511

Peters M. K., Likare S., and Kraemer M. (2008). Effects of habitat fragmentation and degredation on flocks of African ant-following birds. Ecol. Appl. 18, 847–858. doi: 10.1890/071295.1

Peters M. K. and Okalo B. (2009). Severe declines of ant-following birds in African rainforest fragments are facilitated by a subtle change in army ant communities. Biol. Conserv. 142, 2050–2058. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.03.035

Poorter L., Bongers F., Aide T. M., Almeyda Zambrano A. M., Balvanera P., Becknell J. M., et al. (2016). Biomass resilience of Neotropical secondary forests. Nature 530, 211–214. doi: 10.1038/nature16512

Potapov P., Hansen M. C., Laestadius L., Turubanova S., Yaroshenko A., Thies C., et al. (2017). The last frontiers of wilderness: Tracking loss of intact forest landscapes from 2000 to 2013. Sci. Adv. 3, e1600821. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600821

Powell L. L., Cordeiro N. J., and Stratford J. A. (2015). Ecology and conservation of avian insectivores of the rainforest understory: A pantropical perspective. Biol. Conserv. 188, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.03.025

Powell L. L., Stouffer P. C., and Johnson E. I. (2013). Recovery of understory bird movement across the interface of primary and secondary Amazon rainforest. Auk 130, 459–468. doi: 10.1525/auk.2013.12202

R Core Team (2022). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed September 2, 2024).

Roberts D. L., Cooper R. J., and Petit L. J. (2000). Flock characteristics of ant-following birds in premontane moist forest and coffee agroecosystems. Ecol. Appl. 10, 1414. doi: 10.2307/2641295

Robinson W. D. (1999). Long-term changes in the avifauna of Barro Colorado Island, Panama, a tropical forest isolate. Conserv. Biol. 13, 85–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.97492.x

Rodrigues P. F. (2024). The Behavioral Specialization of African Ant-following Birds on Dorylus Driver Ants. Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge (LA. doi: 10.31390/gradschool_dissertations.6530

Rull V. (2008). Speciation timing and neotropical biodiversity: the Tertiary–Quaternary debate in the light of molecular phylogenetic evidence. Mol. Ecol. 17, 2722–2729. doi: 10.1111/j.1365294X.2008.03789.x

Şekerciolu Ç.H. (2006). Increasing awareness of avian ecological function. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.05.007

Şekerciolu Ç.H., Ehrlich P. R., Daily G. C., Aygen D., Goehring D., and Sandí R. F. (2002). Disappearance of insectivorous birds from tropical forest fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 263–267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012616199

Şekerciolu Ç.H., Primack R. B., and Wormworth J. (2012). The effects of climate change on tropical birds. Biol. Conserv. 148, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.10.019

Sodhi N. S., Liow L. H., and Bazzaz F. A. (2004). Avian extinctions from tropical and subtropical forests. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35, 323–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.112202.130209

Stouffer P. C. and Bierregaard R. O. (1995). Use of amazonian forest fragments by understory insectivorous birds. Ecology 76, 2429–2445. doi: 10.2307/2265818

Stouffer P. C., Jirinec V., Rutt C. L., Bierregaard R. O., Hernández-Palma A., Johnson E. I., et al. (2021). Long-term change in the avifauna of undisturbed Amazonian rainforest: ground-foraging birds disappear and the baseline shifts. Ecol. Lett. 24, 186–195. doi: 10.1111/ele.13628

Strevens T., Puotinen M., and Whelan R. (2008). Powerline easements: ecological impacts and contribution to habitat fragmentation from linear features. Pacific Conserv. Biol. 14, 159. doi: 10.1071/PC080159

Struhsaker T. T., Struhsaker P. J., and Siex K. S. (2005). Conserving Africa’s rain forests: problems in protected areas and possible solutions. Biological Conservation 123, 45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2004.10.007

Thiollay J. M. (1997). Disturbance, selective logging and bird diversity: a Neotropical forest study. Biodivers. Conserv. 6, 1155–1173. doi: 10.1023/A:1018388202698

Tyukavina A., Hansen M. C., Potapov P., Parker D., Okpa C., Stehman S. V., et al. (2018). Congo Basin forest loss dominated by increasing smallholder clearing. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat2993. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat2993

Voelker G., Outlaw R. K., and Bowie R. C. K. (2010). Pliocene forest dynamics as a primary driver of African bird speciation. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 19, 111–121. doi: 10.1111/j.14668238.2009.00500.x

Vollset S. E., Goren E., Yuan C.-W., Cao J., Smith A. E., Hsiao T., et al. (2020). Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 396, 1285–1306. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30677-2

Waltert M., Bobo K. S., Sainge N. M., Fermon H., and Mühlenberg M. (2005). From forest to farmland: habitat effects on Afrotropical forest bird diversity. Ecol. Appl. 15, 1351–1366. doi: 10.1890/04-1002

Wenny D. G., DeVault T. L., Johnson M. D., Kelly D., H. Sekercioglu C., Tomback D. F., et al. (2011). The need to quantify ecosystem services provided by birds. Auk 128, 1–14. doi: 10.1525/auk.2011.10248

Whelan C. J., Wenny D. G., and Marquis R. J. (2008). Ecosystem services provided by birds. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1134, 25–60. doi: 10.1196/annals.1439.003

Willis E. O. and Oniki Y. (1978). Birds and army ants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 9, 243–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.09.110178.001331

Wilman H., Belmaker J., Simpson J., de la Rosa C., Rivadeneira M. M., and Jetz W. (2014). EltonTraits 1.0: Species-level foraging attributes of the world’s birds and mammals. Ecology 95, 2027–2027. doi: 10.1890/13-1917.1

Winterbottom J. M. (1943). On woodland bird parties in Northern Rhodesia. Ibis 85, 437–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.1943.tb03857.x

Wolfe J. D., Luther D. A., Jirinec V., Collings J., Johnson E. I., Bierregaard R. O., et al. (2025). Climate change aggravates bird mortality in pristine tropical forests. Sci. Adv. 11, eadq8086. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adq808

Keywords: Afrotropics, rainforest, disturbance, ant-following birds, insectivorous birds, mixed species flocks, understory insectivores, primary and secondary forest

Citation: Barrie EM, Krochuk BA, Jarrett C, Ferreira DF, Rodrigues PF, Mufumu SL, Malanza SE, Akele AEN, Alene CEE, Brzeski KE, Cooper JC, Wolfe JD and Powell LL (2025) Specialized insectivores drive differences in avian community composition between primary and secondary forest in Central Africa. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6:1504350. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1504350

Received: 30 September 2024; Accepted: 30 April 2025;

Published: 10 June 2025.

Edited by:

Natalia Ocampo-Peñuela, University of California, Santa Cruz, United StatesReviewed by:

Matthias Waltert, University of Göttingen, GermanyElise Sivault, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, France

Copyright © 2025 Barrie, Krochuk, Jarrett, Ferreira, Rodrigues, Mufumu, Malanza, Akele, Alene, Brzeski, Cooper, Wolfe and Powell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eleanor M. Barrie, ZWxsaWViMzk1QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Eleanor M. Barrie

Eleanor M. Barrie Billi A. Krochuk

Billi A. Krochuk Crinan Jarrett

Crinan Jarrett Diogo F. Ferreira

Diogo F. Ferreira Patricia F. Rodrigues

Patricia F. Rodrigues Susana Lin Mufumu2,8

Susana Lin Mufumu2,8 Jacob. C. Cooper

Jacob. C. Cooper Jared D. Wolfe

Jared D. Wolfe Luke L. Powell

Luke L. Powell