- 1Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, United States

- 2Department of Zoology and Physiology, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, United States

- 3College of Forestry, Wildlife and Environment, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, United States

- 4High Plains American Indian Research Institute (HPAIRI), University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, United States

Introduction: As the Endangered Species Act (ESA) marks its 50th anniversary, it remains one of the most influential wildlife conservation laws globally. Designed to protect endangered species and their habitats, the ESA sets recovery benchmarks, with the ultimate goal of delisting species once these criteria are met. However, delisting has become a politically charged issue in recent decades, offering a critical case study for the long-term efficacy of the ESA. Our manuscript examines this dynamic through the lens of a high-profile case: the grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) in the Intermountain West region of the United States. We explore the complex process of species delisting, with research questions focusing on the political actors involved in grizzly bear delisting and their perspectives on the process.

Materials and methods: To address these questions, we analyzed 752 policy documents, news articles, and court rulings, extracting 2,832 quotes from key political stakeholders. Using a structural topic model and inductive thematic coding.

Results: We identified five key threads of political discourse surrounding grizzly bear delisting: scientific uncertainty, the role of regulated hunting, human-wildlife conflict, increased state-level management, and the surpassing of recovery goals. Our analysis also highlights which political actors most commonly advance these arguments and how their roles have shifted over time. Notably, elected legislators, legal advocates, and non-governmental organizations are increasingly influential in wildlife policy, overshadowing the traditional authority of executive branch officials and agency scientists.

Conclusions and recommendations: These findings underscore the importance of understanding political discourse and actor dynamics in addressing ESA policy disputes, offering insights into how the law may continue to evolve and how future conflicts might be resolved.

1 Introduction

The most important law for protecting United States (U.S.) wildlife is the Endangered Species Act (ESA) [Endangered Species Act of 1973, 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq. (1973)]. With nearly unanimous bipartisan support, the ESA was passed about 50 years ago by Senators and Representatives in the United States legislature, known as Congress, and signed by President Richard Nixon. The ESA provides a program for the conservation of threatened and endangered plants, animals, and habitats with the powers to implement the law delegated to two federal agencies: the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) for terrestrial and freshwater species and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries Service (hereafter NOAA Fisheries) for marine species (US EPA, 2013). As of 2024, the ESA protects 1,662 U.S. species and 638 foreign species, though this number frequently changes (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (n.d.)). The ESA works in addition to other important species protection laws such as the Lacey Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act to protect threatened and endangered wildlife. Given the recent 50-year anniversary and the law’s domestic and global importance, it is critical to examine key case studies of how the ESA functions to learn from, and subsequently lessen uncertainty for the next 50 years.

Before the ESA was passed, subnational jurisdictions, or state governments in the United States context, were primarily responsible for wildlife conservation and management. The implementation of legislation that put wildlife species management in the hands of federal agencies was groundbreaking in part because of tension in states in the western region of the United States over contrasting federal and state wildlife decision-making and management authority. Some western U.S. political leaders have continued to contest the federal control granted to the FWS under the ESA, arguing it infringes on local control of wildlife Nagle, 2017. One of the most contested issues that highlights the tension between federal and state-level wildlife management is the process known as delisting.

Under Section 4 of the ESA, species can be added to the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened1 Wildlife and Plants due to impairment of habitat, overutilization, disease or predation, inadequate regulatory mechanisms, or other factors imperiling its existence 16 U.S.C. § 1533 (a)(1), 2011. This addition is known as listing. As of March 2023, FWS lists 495 endangered and 249 threatened species of animals U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 2023. Once a species is listed, the FWS designates critical habitat and develops a recovery plan providing the public an opportunity to review and comment on draft plans. Once passed, recovery plans are published in the Federal Register and outline potential threats, strategies to mitigate them, and benchmarks for species recovery.

When the FWS removes species from the list, they initiate a comprehensive regulatory process known as delisting. Delisting requires extensive agency review, public participation through notice-and-comment procedures, and a determination by agency staff that threats to the species have been eliminated or sufficiently reduced. Delisting decisions require rigorous scientific assessments, focusing primarily on population dynamics, long-term demographic trends, habitat quality and availability, and the species’ ability to persist in the wild without continued protections. Ultimately, recovery and delisting of species is the goal of the ESA. Any decision to list or delist a species is based on the best available science, independent peer review of FWS decisions, public comment and participation, and, finally, judicial review Frazer, 2001. Additionally, state agencies play a crucial role by providing scientific information and participating in the review process. The high quality and reliability of the scientific information used in listing/delisting is assured in a joint policy between the FWS and NOAA Fisheries that provides criteria, procedures, and guidance for scientists and managers for the use of scientific information (Fish and Wildlife Service & National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (n.d.)). Since the inception of the ESA, 54 species have been delisted, and 56 downgraded from endangered to threatened U.S. Department of the Interior, 2021.

Despite being one of the most contentious federal laws on the books today, the ESA was passed with near universal support from both political parties, Democrats and Republicans Bean, 2009. While the ESA initially enjoyed strong bipartisan support, this consensus has eroded over the years of its implementation. While conservation and endangered species issues have been contentious for decades, in the post COVID-19 era, conservation issues have become increasingly polarized Casola et al., 2022. This polarization is especially evident in cases involving predator management under the ESA. These cases often become controversial and vitriolic, representing a flashpoint in the broader debate over endangered species protection van Eeden et al., 2021. Opposing or supporting predator conservation has become a way for politicians to, increasingly, signal their ideological commitment to various interests Chapron and López-Bao, 2014. In many cases, predator conservation is controversial because it represents social and political polarities such as urban versus rural lifestyles and livelihoods, and federal versus state power (van Eeden et al., 2021). Large predator conservation often results in tension between different groups of stakeholders with conflicting perspectives including hunters, ranchers, wildlife managers in federal and state agencies, conservation Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), and tribes Hamilton et al., 2020.

As the largest intact temperate ecosystem on earth (Lynch et al., 2008), the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) is a hotbed for conflicts around threatened predator management under the ESA Parker and Feldpausch-Parker, 2013. This controversy is exemplified by the highly publicized and divisive efforts to delist the grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) (hereafter “grizzlies”, “grizzly bear”, or “grizzly”) in this region. The grizzly is an iconic species in the GYE, symbolizing the ideological conflicts between stakeholder groups (e.g. urban versus rural, federal versus state control over wildlife) and questions about large predator survival amidst expanding populations in the American West. In 1975, grizzlies within the lower 48 states of the United States were listed as threatened by the FWS under the ESA. When the grizzly bear was listed as endangered, its habitat range had shrunk by 98%, and fewer than 1,000 bears remained in several areas in the lower 48 states. These areas, which became known as recovery areas, included the GYE, the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem, the Cabinet-Yaak Ecosystem, the Selkirk Mountains, and the North Cascades Ecosystem (Kuehl, 1993). In 1993, the FWS authored a recovery plan for grizzlies, which contained population targets and habitat conservation measures for these remaining populations.

In 2007, after conducting its review process, FWS finalized a rule to delist the grizzly bear in the GYE region as the population had grown to 700 bears, meeting the target in the recovery plan for the GYE. An environmentally focused NGO, the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, sued to challenge the delisting of the GYE population. They ultimately won their case when the federal court in Montana, and subsequently the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, overturned the 2007 delisting. The court found that food sources, such as whitebark pine, were not adequately protected to make the delisting scientifically sound. In 2017, FWS, once again, attempted to delist the GYE population of grizzlies and transfer management responsibilities to the states of Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho, who had proposed a grizzly bear hunt to follow delisting. A federal court in Montana overturned the delisting of the grizzly bear again in 2018. The court ruled that although the GYE population had recovered, the overall recovery of grizzlies throughout the Rocky Mountains was not guaranteed. When brought up in the court, there were concerns expressed about the connectivity between the GYE population and other grizzly bear populations, which is crucial for ensuring genetic diversity. Until these issues were addressed, the court determined that the grizzly bear should remain listed. This decision was appealed to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, who upheld the lower court’s decision, maintaining the grizzly bear’s protected status.

Our study aims to increase understanding about decision-maker stakeholder conflicts around the GYE grizzly bear, by analyzing themes of discourse from political actors (e.g. what are political actors saying about grizzly bear delisting) as well as the types of political actors and themes that dominate the delisting conversation. Understanding this specific ecosystem and population to ensure effective conservation is critical because the GYE is a biodiversity hotspot spanning 3 states and 22 million acres with Yellowstone National Park at the center Epstein et al., 2018. Additionally, understanding the changing perceptions of stakeholders that influence decision-making is paramount to understanding the path forward for the ESA following its recent 50-year anniversary. Our research question examines how decision-makers and other key stakeholders frame and articulate their positions about grizzly bear protection under the ESA and how those perceptions vary among political actors responsible for grizzly bear recovery. Understanding this may help in other contested predator management contexts in the American West and all over the world.

To answer our research question, we adopted an adaptive multi-stakeholder governance approach. In the context of grizzly bear conservation, this approach encompasses a complex system of state and non-state institutions, which includes rules, laws, regulations, policies, social norms, and organizations involved in governing environmental resource use and/or protection Chaffin et al., 2014. The adaptive multi-stakeholder governance model includes processes to ensure all relevant political actors can engage in meaningful collaboration, integration, and make decisions that enable sustainable economic development IPCC, 2012. Drawing on this framework, our research examines decision-maker perceptions on grizzlies within government including the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, as well as sovereign tribes; alongside political actors external to government such as NGOs, journalists, and the public, who all influence decision-making. Understanding the governance rhetoric of grizzly bear management under the ESA is important because it allows us to better understand the ESA’s impact as well as how to effectively balance the preservation of the grizzlies with human needs.

2 Methods

2.1 Study lens: political actors in grizzly bear delisting

Using an adaptive multi-stakeholder governance lens, we opted for decision-making stakeholders as our unit of analysis. We use a broad definition of decision-making stakeholders that goes beyond a government employee and includes actors outside of government such as NGOs, journalists, and members of the public speaking out and encouraging changes in policy. The political actors whose perceptions on grizzly bear delisting that we analyzed included: state governors, employees in federal and state wildlife management agencies (executive branch), members of Congress (legislative branch), and people operating in the courts (judicial branch). Additionally, there are 27 tribes with historic and modern ties to Yellowstone with decision-making power and influence that were included National Park Service, 2024. In addition to political actors and tribal nations, NGOs and members of the public were included in our analysis. These actors were included because decision-makers have demonstrated a multi-stakeholder collaborative approach to GYE grizzly bear management through coordination endeavors such as the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee Epstein et al., 2018. We chose to group individuals, politicians, and agencies into executive, legislative, or judicial branches. This allowed us to examine the sentiment of statements and categories across time and between groups.

2.2 Article selection approach

To analyze themes of discourse from political actors in the GYE, we systematically reviewed policy documents, court decisions, and news articles published between 1/1/1981 and 09/05/2024. The systematic search was conducted using the U.S. Newsstream Proquest Database.

We used four different search terms with boolean operators to identify a broad stream of articles published within our analysis time frame. The first search terms, “Grizzly bear” AND “Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem” yielded 5,625 results. Of these results, 354 articles were analyzed ending up with 670 rows of coded data. Depending on how many political actors are mentioned in an article up to 15 rows of coded data could come from a single article. The search term “Grizzly bear” AND “delist”, provided 1,173 search results. 269 articles were analyzed, creating 605 coded rows of data. The term “Grizzly bear” AND “Endangered Species Act” showed 15,166 results of which we analyzed 72 articles and ended up with 303 coded rows of data. Finally, “Grizzly bear state management act” showed 19,542 results which resulted in 57 articles and 146 rows of coded data. Overall 1,683 rows of data were created and 752 articles read. “Grizzly bear” AND “Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem” as well as “Grizzly bear” AND “delist” were the most successful in terms of providing the most articles that had political actors mentioning multiple categories we were coding for. “Grizzly bear state management act” tended to have many duplicates as well as pulling articles that involved state management of other species instead of specifically grizzly bears. This occurred as well with later articles found with “Grizzly bear” AND “Endangered Species Act” which would pull articles around the ESA that did not involve grizzly bears.

2.3 Qualitative analyses

Once we determined their relevance, we categorized the articles into political actors, the stances being taken, and arguments being made for delisting grizzlies or not. With each new search term articles were screened, and those that did not take place in the United States, lacked direct reference to grizzly bears, or failed to provide relevant information pertaining to our review topic were excluded. Inclusion criteria were articles based in the United States and mentioning grizzly bears. Articles meeting these criteria were reviewed closely for eight themes developed from the literature. We chose these categories to analyze the changes in political actors’ arguments over time because they appear to be recurring themes throughout the timeline of delisting. The question categories were:

1. Does the perspective of the political actor mention the contested state of the science?

2. Do they mention the importance of keeping the current process as is?

3. Do they state whether GYE grizzlies are a distinct population (issues on genetics)?

4. Do they talk about whether the population has surpassed recovery goals or not?

5. Is an argument made about state agency capacity (or lack thereof)?

6. Are Native American perspectives mentioned?

7. Do they mention the costs of grizzly bear management, anything about grizzlies on private land or loss of habitat, or hunting grizzly bears for management?

8. Do they mention climate change affecting grizzlies?

The data were coded through an iterative process, beginning with an initial cycle of in vivo coding using a grounded theory approach, followed by a second cycle of thematic coding where statements were classified using the above eight criteria (Saldaña, 2016). In vivo coding was chosen for the first cycle to capture the speaker’s exact words, ensuring that their intent and sentiment were preserved and ensuring the eight codes were exhaustive. Grounded theory, an inductive method that allows theories and concepts to emerge directly from the data (Charmaz, 2006), was particularly well-suited for this analysis of stakeholder and policy actor comments. As patterns emerged, codes were iteratively refined through analytic memo writing and observation, either collapsing or splitting codes as necessary. The second cycle of thematic coding was then applied to group similar in vivo codes, providing a more structured framework for inputting each comment into the datasheet. This process allowed for a more focused, quantitative analysis by narrowing the number of codes while still reflecting the original sentiments. Ultimately, repeated patterns and the recurrence of similar comments enabled the consistent application of thematic codes to new data.

2.4 Topic modeling and quantitative analyses

In addition to the qualitative analysis, we quantitatively analyzed the text data from the selected articles using structural topic modeling (STM) approach to quantify how words co-occurred for each political actor category. This allowed us to measure common topics being discussed by political actors involved in grizzly bear delisting. We included default stopwords as well as a custom stopword list (get, like, one, re, said/say/says, will, grizzly/grizzlies, bear/bears) to remove uninformative words from the analysis and tokenized the text using the `SnowballC` package (Bouchet-Valat, 2023). We required each word to be used in a minimum of 10 documents to be included in topic identification. This ensured that only relevant terms contributed to the topic modeling (Roberts et al., 2019). We then determined the frequency of words in each document and created a topic model using the stm package (Roberts et al., 2019). This allowed us the most frequent topics (defined as co-occurring sets of words) across the corpus of documents. To ensure the robustness of the topic model, we ran 20 iterations using spectral initiation of the STM and a maximum of 10,000 iterations to ensure full convergence (Hosseiny Marani & Baumer, 2023).

For each of the top four topics for each political actor group, we conducted means parameterized regressions to assess the relationship between the prevalence of each identified topic. We used a means parameterization because it allowed us to directly estimate the average effect of the political actor category on the prevalence of each topic. For each topic, we used the estimateEffect function in the STM package to fit a regression model with “political actor” as the independent variable and topic prevalence as the dependent variable (Roberts et al., 2019). Political actors could include executive, legislative, judicial, tribal, NGO, journalist, or individual citizens. We compared the mean 95% confidence interval around the coefficient estimates among political actor groups to identify significant differences in the frequency of these topics for each group of political actors. Finally, we consider how the use of these topics changed over time for each political actor group using a linear regression where topic frequency was again the dependent variable and the interaction between political actor and the publication date of each article was the independent variable. We identified significant change over time as interactions with coefficient estimates that were significantly different from zero. All analyses were conducted in R, and all R code is available via GitHub (https://github.com/jwillou/grizzly_textanalysis).

3 Findings

We reviewed 752 policy documents, court decisions, and news articles about grizzly bears in the years since the species was listed in 1975. Within these documents, we were looking to identify the various types of political actors at federal, state, and local scales commenting on the issue of grizzly bear delisting. Of the documents reviewed, we found 2832 relevant statements of political actors or policy documents issued by agencies.

3.1 Quantitative findings

We analyzed text from 2832 political actor quotes, which included 1268 different words and 66,498 words in total. These were attributed to the seven political groups, with quotes from the executive branch of federal and state governments representing the majority (N=488 quotes), followed by journalists (N=360), NGOs (N=323), individuals from state or federal legislature (N=162), the public (N=107), Indigenous Peoples (N=72), and finally individuals associated with state or federal judicial branch (N=30).

Using a structural topic model, we identified four sets of words that co-occur the most frequently in these texts. They are as follows:

1: manag, state, delist, wyom, wildlif, recov, work

2: popul, speci, yellowston, endang, wildlif, list, act

3: hunt, protect, nation, feder, land, yellowston, habitat

4: peopl, conflict, human, kill, can, year, area

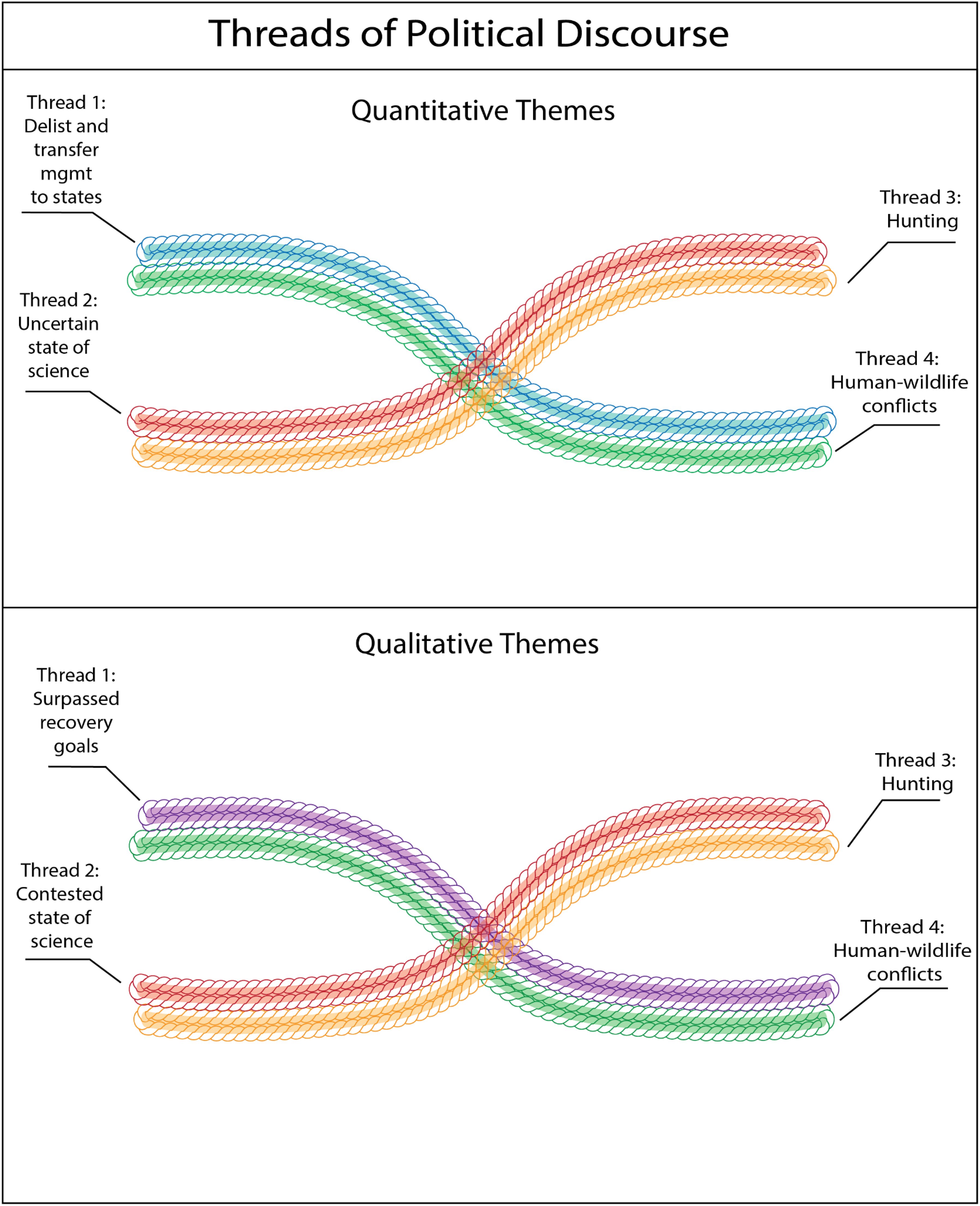

We will call these most frequent commonly occurring words “threads of political discourse.” Figure 1 below displays the threads of political discourse for our quantitative analysis and our qualitative analysis which is explained later on. Next, for each of these threads of political discourse, we looked for representative quotes from our dataset to provide examples of what these threads look like. Then we quantified the most common political actor responsible for that thread. We put representative quotes from the most frequent political actors mentioning these themes in Table 1, and our quantification of the most frequent political actors using that thread of political discourse is in Figure 2. In sum, Table 1 and Figures 1, 2 show the most common threads of political discourse around grizzly bear delisting, examples, and the actors most commonly employing those threads.

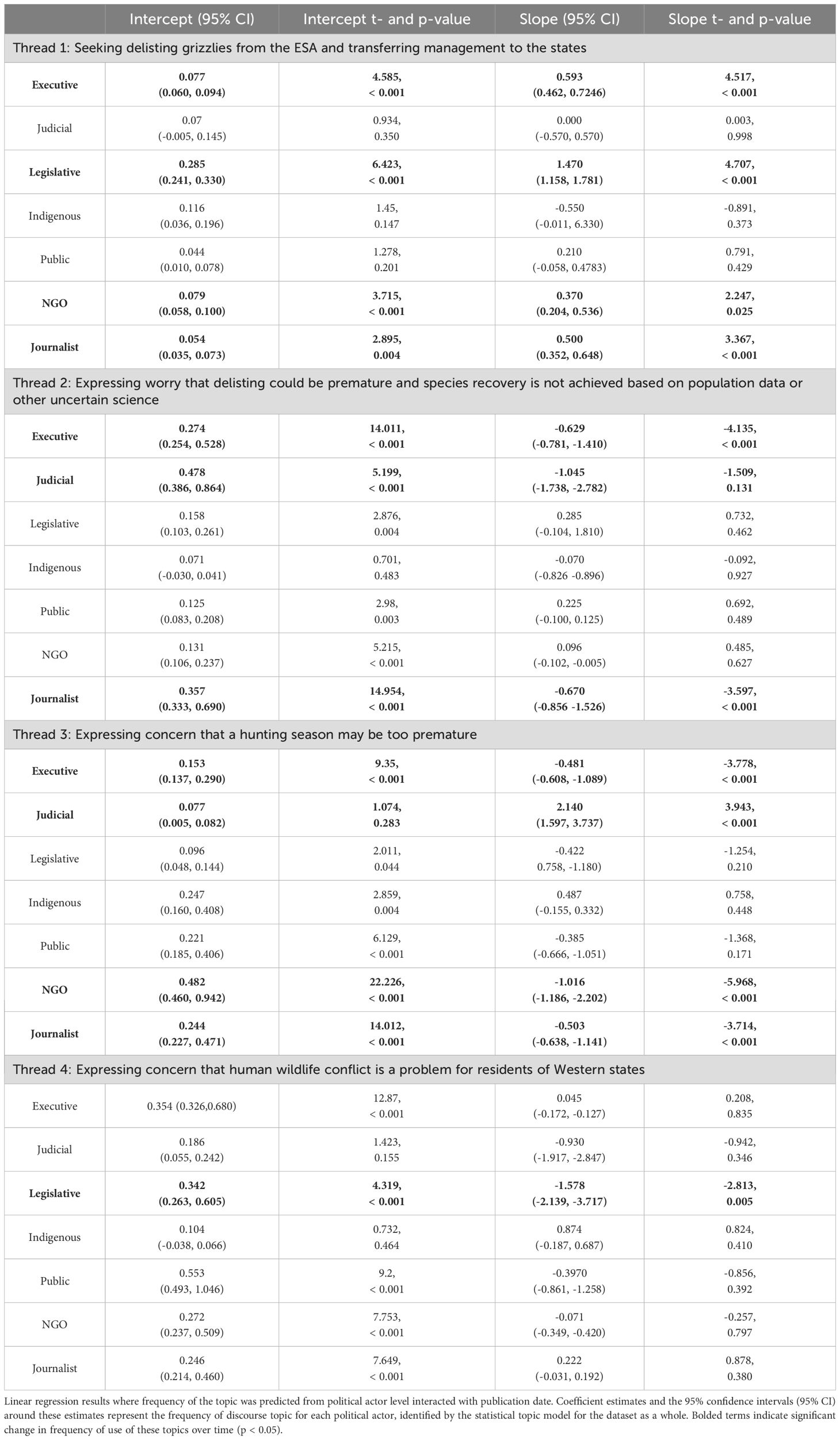

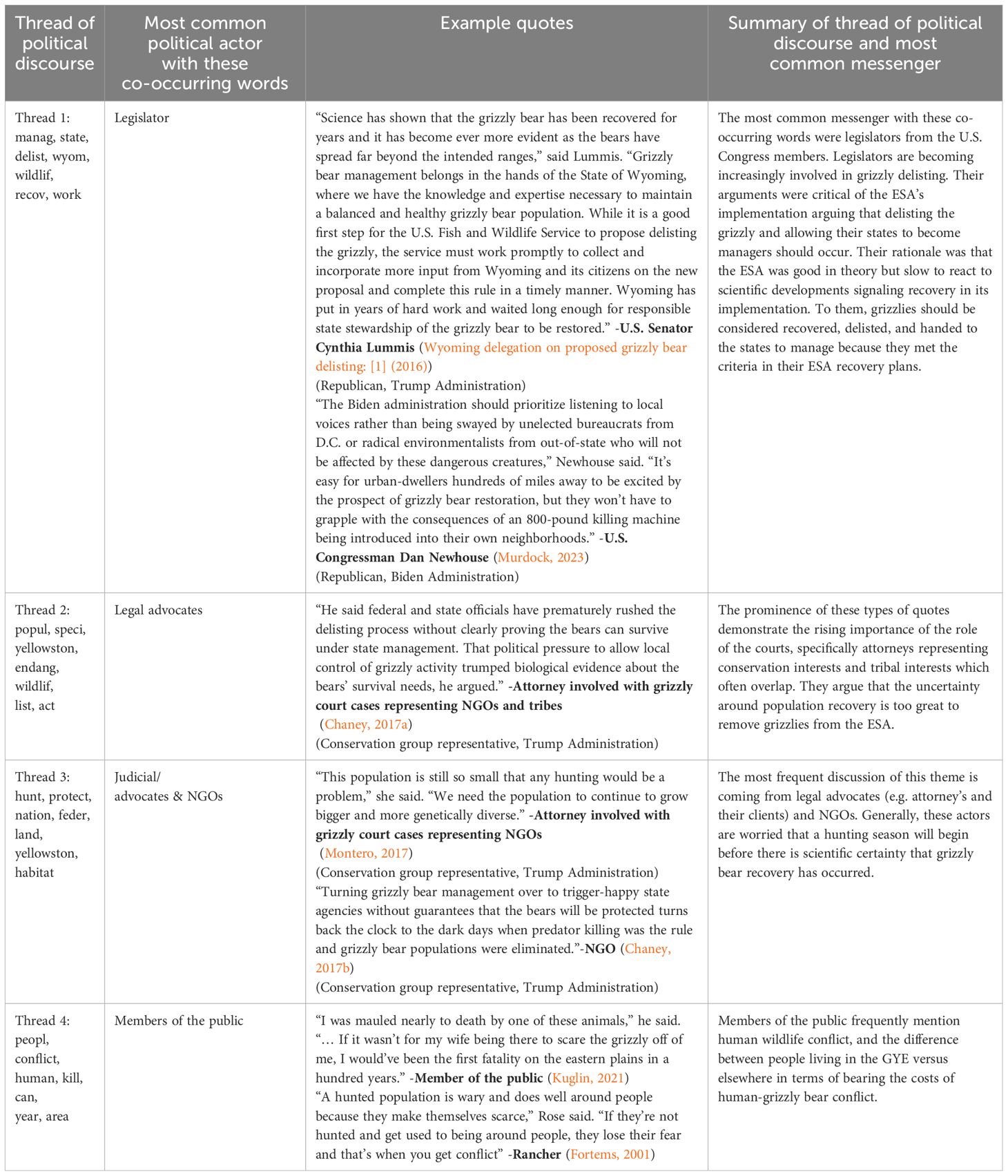

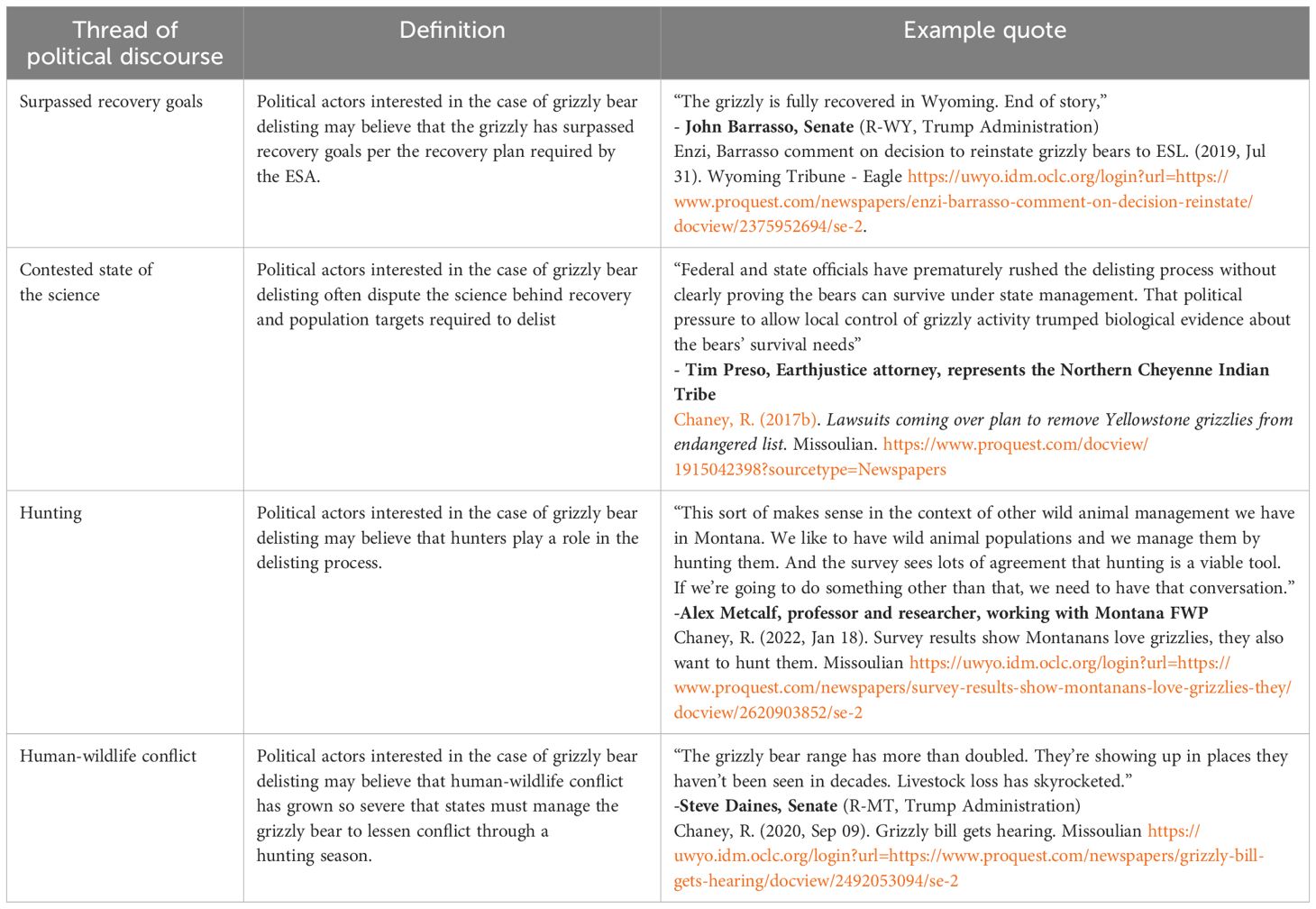

Table 1. Threads of political discourse: Co-occurring words with their most frequent political actor to show example quotes.

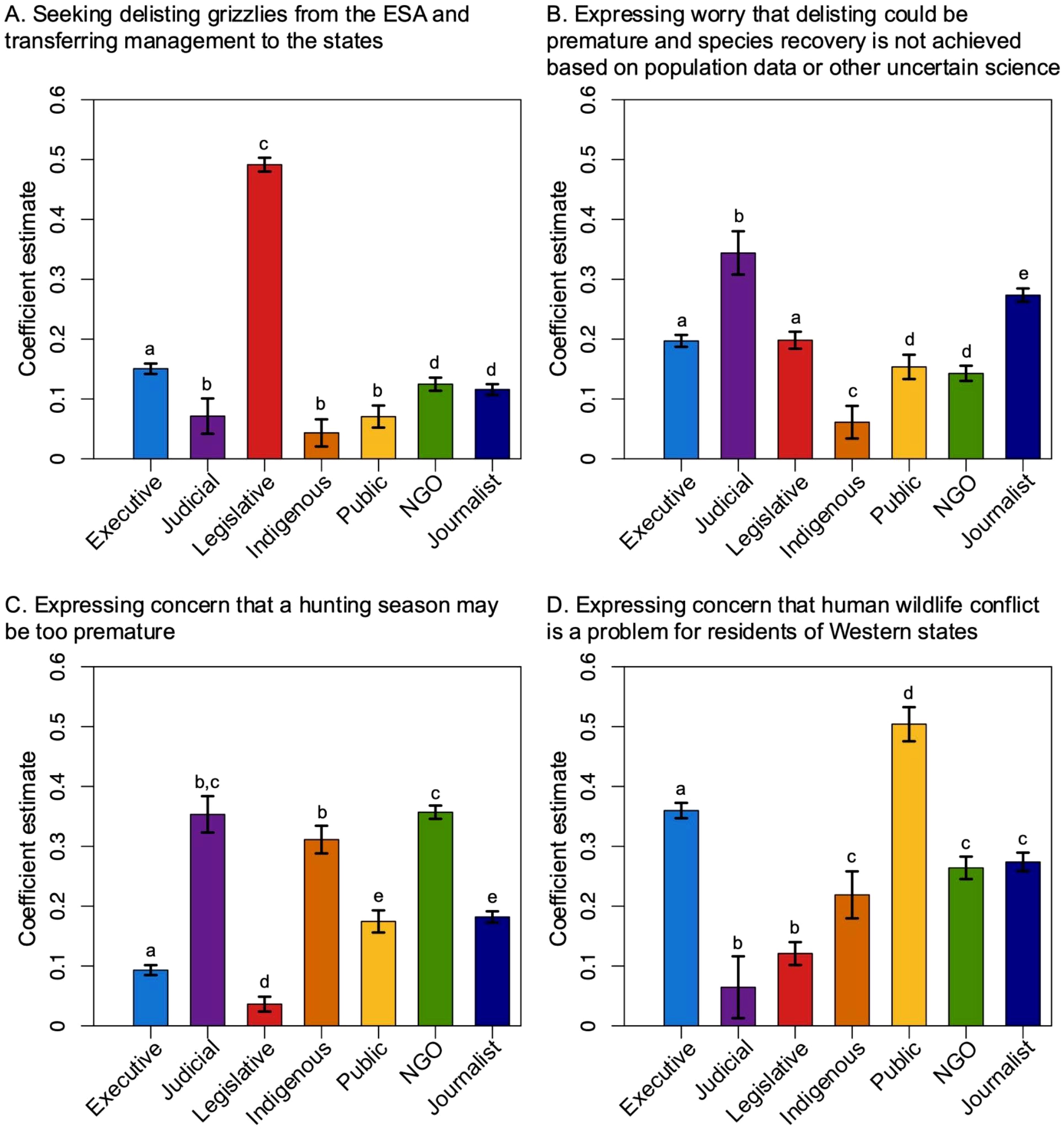

Figure 2. Predicted frequency of use of the four most common topics by political actor, derived from means parameterization regression. The bars represent the predicted mean frequency of the use of each topic (i.e. the coefficient estimate from the regression) for each political actor and confidence intervals around each bar indicate the 95% confidence interval around these mean frequencies. Letters above the bars denote statistically significant differences among political actors. Each panel (A–D) denotes the frequency of the statistical topic where the model identified co-occurring words for the dataset as a whole, and panels are labeled by the qualitative interpretation of these themes.

We would expect most discourse around grizzly bear delisting to take place in the branch of government where its management authority is located, the executive branch. Our findings contradict those expectations suggesting the rise in importance of other political actors, namely legal advocates and NGOs. The threads of political discourse in Table 1 above can be summarized as Thread 1) political actors seeking delisting grizzlies from the ESA and transferring management to the states, Thread 2) political actors expressing worry that delisting could be premature and species recovery is not achieved based on population data or other uncertain science, Thread 3) political actors expressing concern that a hunting season may be too premature, and Thread 4) political actors expressing concern that human-wildlife conflict is a problem for residents of Western states. The most frequent political actors employing Thread 1 (delisting should occur and states takeover management) are not agency scientists, but rather legislators in Congress. The most frequent political actors expressing Threads 2-3 (concern over premature delisting and species recovery as well as over a possible hunting season) are the courts and NGOs. It is members of the public most frequently expressing concern that human-wildlife conflict is intensifying for Thread 4. Not one of the threads was most commonly deployed by the executive branch of government, where grizzly bear management authority is vested.

We also considered how the threads in political discourse changed over time, focusing on which political actors deployed these threads of discourse more often (Table 2). For Thread 1 (delisting should occur and states should take over management), the largest increase in use over time was by legislative actors, with an increase approximately three times greater than the increase in use observed for executive political actors (who typically hold decision-making power over wildlife issues), NGOs, and journalists (Table 2). This shows how elected lawmakers in Congress are seizing a more prominent role in these political conversations than might be expected from the executive branch. Conversely, judicial actors showed no significant engagement with this thread, maintaining a near-zero frequency throughout the entire period. Members of the public, as well as Indigenous actors, specifically did engage with this thread although there was no significant change in the frequency of their use of this thread over time.

For Thread 2, which focused on the concern that delisting is too premature, the executive, judicial branch, and journalists decreased the frequency of using this thread over time. We observed the largest decrease in use amongst legal advocates (e.g. attorneys speaking on behalf of their clients), with a decrease approximately twice the decrease of the executive branch and journalists (Table 2). This trend may suggest a shift in focus by the judicial and executive branches to other topics. In contrast, the decline in journalist engagement with this thread could reflect a broader shift in public or media interest in the topic of delisting and species recovery. Actors from the legislative branch, NGOs, and the public expressed initial concern but showed no significant change in their involvement over time. This suggests a consistent level of concern among these groups, indicating that for them, the issue remains relevant and unresolved.

Thread 3 focused on concerns over a possible premature hunting season, with significant changes in the use of this theme by the executive and judicial branches, NGOs, and journalists. Over time, actors associated with the executive branch, NGOs, and journalists decreased their reliance on this thread, with NGOs showing nearly twice the decline observed in journalists and the executive branch (Table 2). Conversely, judicial actors began with a similar frequency of reliance on this thread, but their use increased over time, showing more than twice the magnitude of increase compared to the decreased frequency seen in the executive branch, NGOs, and journalists. Overall, this suggests that concerns over grizzly bear hunting are becoming more prominent in court discussions, while the focus from the executive branch, NGOs, and journalists has waned.

Finally, considering concerns about intensifying human-wildlife conflict (Thread 4), the legislative branch was the only significant political actor showing a change in the frequency of use of this thread. Over time, legislative actors’ engagement with this thread decreased significantly, suggesting a reduced focus on human-wildlife conflict in legislative discussions (Table 2). This decline stands out compared to the relatively stable trends observed in other actors.

3.2 Qualitative findings

Using inductive reasoning and grounded theory methods, we found an additional 11 threads of political discourse common in political actors’ statements on grizzly bear delisting. Including this qualitative analysis allowed us to extrapolate less frequent, or more nuanced statements from the documents than the quantitative analysis provided. The complete table A.1 is located in the appendix. The four most commonly deployed threads of political discourse are outlined with examples in Table 3 below. These themes include perceptions that grizzlies may have already surpassed recovery goals, concerns over human-wildlife conflict, perspectives on hunters’ roles in management, and the contested state of some aspects of recovery science.

Table 3. Most widely used four threads of discourse among political actors found through qualitative coding of statements.

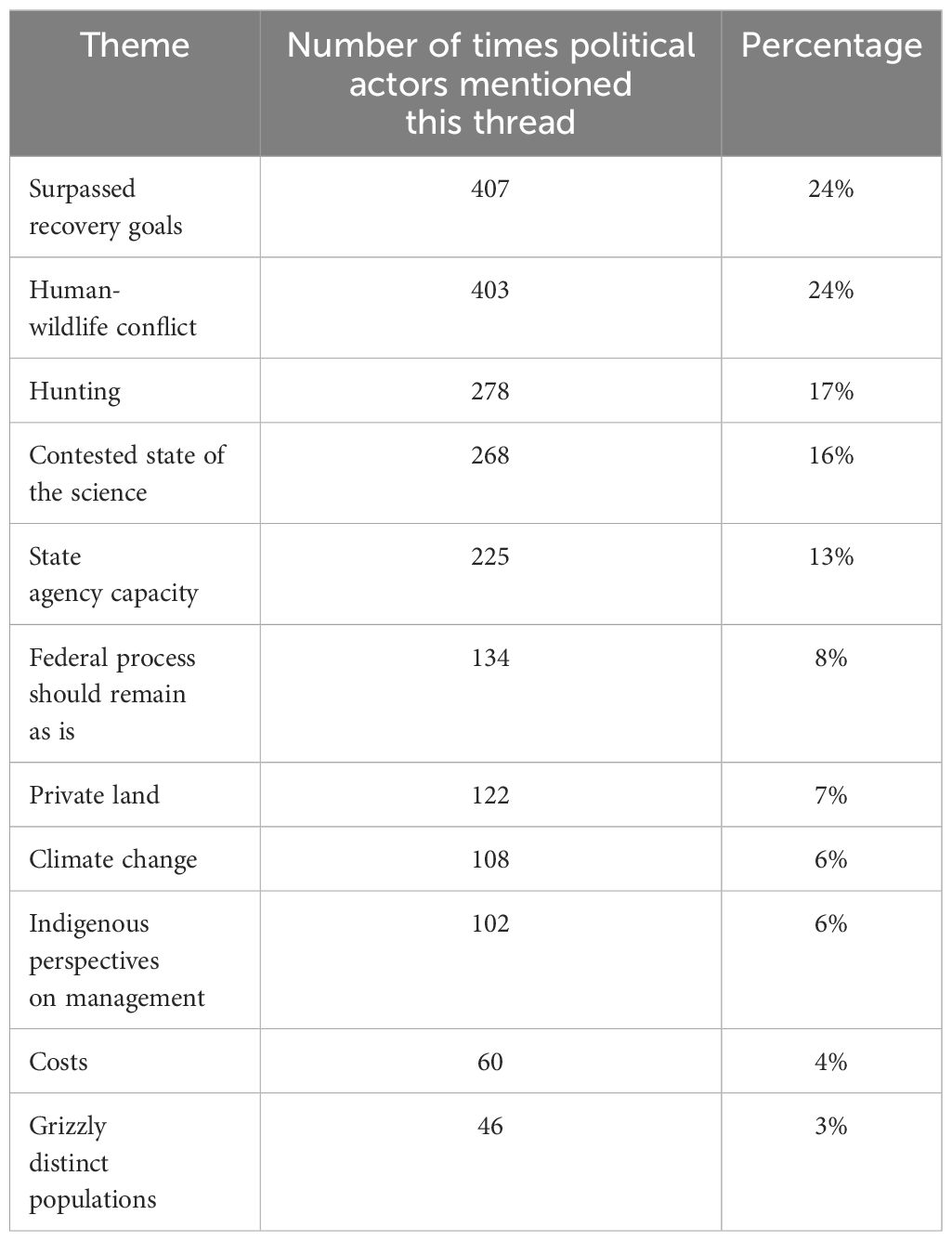

Table 4 below shows that the most frequently appearing threads in our qualitative data were grizzlies surpassing recovery goals (24%), human-wildlife conflict issues (24%), the possible use of hunting seasons as a management tool (17%), and the contested state of the science behind recovery and management (16%).

Table 4. Frequency of appearance of threads of political discourse amongst quotes from political actors.

The most important and frequently appearing thread, that of GYE grizzlies surpassing recovery goals in their recovery plan, occurred in 24% of political actor statements. The greatest number of statements discussing recovery goals were made by state and federal agency staff in the executive branch of government (40% of coded statements). A representative statement of this type was made by Lynn Scarlett, the Deputy Secretary of the Interior (Independent, appointed by George W. Bush) who said, “There is simply no way to overstate what an amazing accomplishment this is,” (Boxall, 2007) speaking about recovery of the GYE grizzly bear population. Her statement refers to the 700 grizzlies in the GYE, a population target that exceeds the recovery plan. Wildlife managers sort the 1700 grizzlies of the Intermountain West into distinct population segments that can be delisted. The distinct population segment in Idaho’s Selkirk Mountains for example has not yet met its delisting criteria as far as its population targets are concerned. Similarly, the director of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC) stated, “There are challenges because we’re not doing recovery anymore - we’re doing management” (Chaney, 2017a). A third representative statement comes from a U.S. Forest Service manager who said, “What we’re seeing is a wonderfully rapid population growth of grizzlies in the area [The ecosystem is] being overwhelmed by the population expansion. There’s a lot of science behind that” (Chaney, 2018b).

The thread of human-wildlife conflict occurred in 24% of political actor statements, with 35% of these statements made by agency staff in the executive branch of government. Agency managers cite the following as the major sources of human-wildlife conflict, “railroad collisions, car collisions, hunter/recreationist encounters and management actions where grizzlies have been killed after preying on livestock or other human food supplies.” A representative perspective from agency managers typically describes how grizzly bear managers used to focus on recovery and now focus on avoiding human-wildlife conflict. An example from Governor Gianforte’s office (Republican, Montana) “As grizzly bear numbers have grown [this] has led to increased conflicts with communities, livestock producers and landowners. We worked on grizzly bear recovery for decades. We were successful and switched to a focus on conflict management years ago” (Governor’s Office, 2021). While agency staff are most frequently discussing human-wildlife conflict, as expected, 8% of statements came from legislators at the federal or state level. Historically, representatives and senators have not weighed in on the science of wildlife management but that is changing. A representative comment comes from Republican Senator Mike Enzi, “As the grizzly bear population has increased in Wyoming, so has the danger to livestock, property, and humans. That is why it was so important that management of the species had been turned over to the state” (Sen. Enzi Issues Statement on Federal Court Decision to Return Grizzly Bears to Endangered Species List, 2018).

The thread of hunting as a management tool appeared in 17% of statements. The two most common political actors discussing hunting as management were NGOs (21% of statements) and journalists (36% of statements). Amongst NGO political actors, they generally held the view that when grizzlies are delisted and their management returned to the states, that ultimately those consequences would be negative. A representative quote is as follows, “It’s disheartening that the federal government may strip protections from these treasured animals to appease trophy hunters and the livestock industry [they] can’t be trusted to make science-based wildlife decisions. Our nation’s beloved grizzlies deserve better” (Diaz, 2023). By contrast, agency managers’ views are summarized by the following representative quote by those who see hunting as a management strategy, “Regulated hunting is not only a pragmatic and cost-effective tool for managing populations at desired levels; it also generates public support, ownership of the resource and funding for conservation as well as greater tolerance for some species such as large predators that may cause safety concerns and come in conflict with certain human uses” (Hughes, 2018). Similarly, another representative quote on hunting as management describes what that process would look like, “Under the conservation plans [hunting] would be highly regulated, and the number of allowable kills each year would be calculated on the previous year’s population and mortality figures. Most years that number will not exceed the low double digits and more likely would be in the single digits or even zero. With meticulous management and monitoring, the grizzly should be able to survive and thrive” (Grizzly Bears Should Survive Being Delisted, 2016).

The fourth most commonly mentioned theme was the contested state of the science of delisting, with the largest portion of these statements coming from NGOs (32%). Often, NGO employees argued that agency personnel were delisting not for scientific reasons but for political reasons. A representative quote on this topic from an NGO employee working on delisting, “Plans for delisting are taking their cues from politics, not what is best for the bear” (Wilkinson, 1999). Other statements in this theme of unsettled science had to do with the perception amongst NGO stakeholders that hunting grizzly bears would result in a practice that some NGOs consider akin to slaughter. A representative statement is as follows, “The wolf slaughter that’s happening in Montana right now demonstrates how poorly equipped Montana decision-makers are to decide the fate of these majestic species, whether grizzlies or wolves. Given Gov. Gianforte’s bloodlust for wolves, and now grizzlies, the federal government should deny this scientifically and legally illegitimate and ethically unfounded request to strip the endangered status of grizzlies” (Chaney, 2021). Other NGO criticisms of unsettled science looked at the process of delisting, as not adequately including public comment, or allowing for the delisting of distinct population segments rather than waiting until all locations with grizzly had recovered. The latter being a strategy that, in the words of an NGO stakeholder views grizzlies as a “meta-population that’s connected to be a recovered population. A few isolated pockets in a few locations is not feasible” (Chaney, 2018a).

Executive branch stakeholders from federal and state agencies also frequently weighed in on debates over how settled the science behind delisting was and is. While the following quote is from a legislator, it represents views held by those in the executive branch that the science is settled on recovery and that states should be allowed to manage grizzlies following delisting. The representative quote is as follows:

“The grizzly bear has successfully recovered in Wyoming. The state of Wyoming should be able to move forward with management of the bear. This judge’s decision demonstrates exactly why the Endangered Species Act must be modernized. “The good work Wyoming, and other states, are doing to protect and manage species should have an opportunity to succeed. The grizzly bear delisting shouldn’t be undone by the courts. Even the Obama administration determined that the grizzly should be delisted. I will continue to work to make sure that management of the grizzly remains with Wyoming.” (Wyoming Senator John Barasso, Republican)

4 Discussion

To summarize our most important findings, the quantitative analysis found four of the most common threads of political discourse around grizzly delisting (alongside the most frequent political actor deploying this thread indicated in parentheses). These include Thread 1 that states ought to manage populations after delisting (legislators), there is some uncertain science around recovery (judicial/courts), hunting raises additional uncertainties (judicial/courts and NGOs), and intense human-wildlife conflict concerns among local communities (members of the public). Our four most important threads of political discourse according to our qualitative analysis include Thread 1 that recovery goals have been surpassed (executive), Thread 2 that there is contested science around recovery, Thread 3 that hunters may or may not be the right way to enact management (NGOs/journalists), and Thread 4 intense human-wildlife conflict concerns (executive). The threads of political discourse that emerged from the qualitative analysis aligned with the quantitative analysis, with the exception of Thread 1. In the quantitative analysis, the first thread pertained to delisting and turning management of populations over to states. Conversely, in the qualitative analysis, the first thread was also in favor of delisting, but because recovery goals have been surpassed.

One of the most important findings here is that elected legislators, not agency scientists in the executive branch, are one of the most prominent sources of political discourse around bear delisting. Beginning in the 20th century, scientists and managers in the agencies of the executive branch were the most important actors in wildlife decision-making Keiper, 2004. We find that increasingly legislators are engaging with science, and using that to recommend that agencies in their states be handed the power to manage grizzlies. This is a significant finding, especially when understanding the historic timeline of the discourse of delisting. It is widely understood that legislators are increasingly weighing in on wildlife management decisions going all the way back to the Sagebrush Rebellion populism that began in the 1970s Thompson, 2016. Indeed, the most famous example of Congress intervening in the ESA was through its unprecedented delisting of gray wolves in 2011 through an unorthodox rider attached to a budget Barringer and Broder, 2011. Our data shows individual representatives and senators’ involvement in delisting under the ESA is a significant political trend that is increasing in importance. This is seen through the number of articles appearing in searches and an increasing number of individual actors becoming more vocal and getting media coverage of it, leading to a more politicized conversation as well as increased political involvement. This suggests that federal and state managers in the executive branch must be better equipped to deal with lawmaker input and public discourse around science from lawmakers than they have been in the past.

Because the branch of government where scientific expertise is held, which employs thousands of scientists, is traditionally the executive branch (agencies), there too lie the channels of communication between scientists and managers Keiper, 2004. The legislative branch is regarded as the “most democratic” branch of government in the U.S. system, and its increasing role in scientific disputes in policy shows that there is a need for scientific advice that is great but poorly met Keiper, 2004. The agency that was designed to provide scientific advice to Congress, the Office of Technology Assessment, was dismantled decades ago, suggesting new connections between scientists and legislators are urgently needed especially in the field of wildlife science. Likewise, studies of other large predators suggest that political identity plays a large role in people’s willingness to accept certain management of large predators Hamilton et al., 2020. Our findings show more than anything that scientists’ responsibility to be neutral and objective could cause their perspectives and preferences to be overshadowed by popular political discourse. Large predators are highly politicized and so agency managers (federal and state) may need to explore ways to engage with political discourse, and develop strategies to overcome politicization. While administrations change, and different agency leaders are appointed–some with differing agendas–developing engagement strategies, and ensuring political voices have relevant scientific information, becomes more important than ever.

Another important trend our data illustrate is that the role of the courts in shaping political discourse is growing. In other words, the number of cases being brought to the courts by both conservation, and delisting advocates, is increasing. This is especially important because threads of political discourse from legal advocates are the primary source of uncertainty concerning the recovery science and whether limited, regulated hunting seasons will be palatable to the public, who all get a say in contested wildlife decisions. The major source of uncertainty brought up in the courts concerning science has to do with a technical consideration: genetics. Analysis of genetic data is highly technical and is not an area that many political actors hold expertise in, including managers in agencies and even agency scientists (Cook & Sgrò, 2017; Kelly, 2010). The most recent delisting in 2017, overturned by the courts after challenges from environmental NGOs, focused on the need to translocate grizzly bears from different locations. This translocation action is meant to increase the number of genetic variants present in these populations because genetic variation is otherwise expected to decline in the absence of natural corridors that connect populations (Christie and Knowles, 2015; Lamka and Willoughby, 2024; Lowe and Allendorf, 2010). To facilitate these and other actions, an innovative coordination organization, the IGBC was formed back in 1983 with the ultimate goal of delisting of the grizzly (Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee, 2016. In its 2024 Conservation Strategy, a core policy document to support GYE grizzly recovery, the IGBC commits political actors to address genetic connectivity issues in a coordinated way. The activities of the IGBC suggest that multi-stakeholder groups such as this, focused on working across scales, agencies, and stakeholder groups, is a notable pathway ahead when navigating complex technical issues like population genetics change over time.

Another notable finding was that the courts were often an important avenue for voicing the perspectives of the tribes. A representative tribal stakeholder perspective is as follows, expressed and coded as both courts and Indigenous: “The grizzly is foundational to many Indigenous cultures,” said Rain Bear Stands Last, who assisted plaintiffs with the lawsuit and is the executive director of the Global Indigenous Council, a body of Indigenous tribes from around the world” Fazio, 2020. The Biden-Harris Administration has taken some of the most important steps in recent history to ensure greater tribal inclusion and participation in decision-making over many issues including natural resources and wildlife management Department of the Interior, 2023. But, because co-stewardship and co-management have a long way to go with tribal inclusion, our research suggests that the primary way for tribes to enact political discourse around grizzlies has been through the court system. Many tribes have a relationship with grizzly bears and have lived alongside them not only in the GYE but historically on the Great Plains. Tribal members commonly assert that their connection with grizzlies is not taken into account when it comes to delisting or management and that political systems are not set up to take this connection seriously in decision-making.

Other similar research on the case of the grizzly that conducted a similar analysis of stakeholder quotes found that major themes related to governance between 1998-2009 included the need for policy reform, questions over the purpose of the ESA itself, authority or district of authority, concerns over scientific uncertainty, and climate change Parker and Feldpausch-Parker, 2013. Our research builds on Parker and Feldpausch-Parker (2013) by focusing solely on adaptive multi-stakeholder governance (whereas they also examine ethics and identity) and expanding the timespan for analysis of political discourse. Similar to Parker and Feldpausch-Parker (2013), we found that concerns over scientific uncertainty are still present today, with uncertainty over genetic exchange and the use of hunting as a management strategy being the most important. The political actors raising questions about science are primarily NGOs through lawsuits, therefore raising questions in the courts.

Other research on multi-stakeholder governance of predators suggests that to manage them effectively, 1) stakeholder analysis, 2) consultation and engagement, and 3) ongoing monitoring of how stakeholders interact and develop management strategies Hovardas, 2018. Our research contributes to the third phase of multi-stakeholder governance of predators, or ongoing monitoring of how interactions are occurring. Seeing who is deploying political discourse around delisting can help for a more structured interaction between stakeholder groups over time and possible solutions to ongoing disputes around science and management Hovardas, 2018. Globally, one of the key ways that stakeholders can move towards more collaborative solutions with large carnivores is to increase dialogue, which in turn can increase trust and help define shared goals Salvatori et al., 2021. Increased dialogue and trust can facilitate shared sets of knowledge that are co-produced, rather than a situation with oppositional groups of stakeholders working off of completely different information as our data suggests is happening today with some of the disputed recovery science. While the co-production of knowledge is a necessary step in minimizing disputes, we acknowledge that it will not fix all of the challenges surrounding endangered species delisting, as some decisions are made due to differing core values and motivations of stakeholders and decision-makers.

As with most research, there are limitations to the methods used. In this research, one limitation is the distribution of voices in popular media. For example, not all scientific agencies are at liberty to take a political stance when it comes to grizzly delisting. Therefore, there may be a lack of representation in the media of agency scientists in comparison to other actors. Additionally, certain political actors (in the legislative branch) tended to be the most vocal and used delisting as a political platform. In doing this, these actors may be more represented in the media. This limitation was minimized by the inclusion of agency policy documents in the review. These documents allow agency scientists to state their perspectives. Future research could build upon this idea, and potential limitation, by comparing the political discourse presented in media articles to the discourse and positions presented in policy documents.

5 Conclusion

The political complexity surrounding the delisting of species under the ESA highlights the evolving nature of wildlife conservation in the United States. Our study, centered on the grizzly bear delisting in the iconic GYE, illustrates how political actors, discourse threads, and shifting power dynamics shape policy outcomes. The increasing influence of legislators, legal advocates, and non-governmental organizations, alongside scientific uncertainty and state-level demands for greater control, underscores the challenges of balancing species recovery with public and political expectations. As delisting becomes an increasingly contentious issue, understanding the motivations and arguments of various political actors is crucial for the long-term success of the ESA. While the ESA used to be handled by political actors like agency scientists in the executive branch, this is no longer the case. Our findings suggest that future efforts to resolve policy disputes will require more nuanced engagement with the political landscape surrounding species conservation. We suggest science experts (e.g., from wildlife ecology, human dimensions, or other related fields) consider our findings the next time they receive a request for comment from a communication outlet. By understanding both the perspectives of scientists and political entities, policymakers and stakeholders can navigate the complexities of delisting in an informed manner. This will help to ensure that conservation objectives are met while addressing broader societal concerns about highly politicized wildlife species.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. BA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TF: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TaS: Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. TeS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JW: Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision. KD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Aiden “Hunter” Sulak for assistance in coding the data for this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2025.1508158/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ Endangered species are in danger of extinction throughout their range while threatened species are likely to become endangered (16 U.S.C. § 1532 (6) & (20).

References

16 U.S.C. § 1533 (a)(1) (2011). “Endangered species act. Section 4,” in Determination of endangered species and threatened species. Available at: https://www.fws.gov/laws/endangered-species-act/section-4 (Accessed October 8, 2024).

Barringer F., Broder J. (2011). Rocky mountain wolf removed from endangered list by congress—The new york times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/13/us/politics/13wolves.html (Accessed October 5, 2024).

Bean M. J. (2009). The endangered species act. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1162, 369–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04150.x

Bouchet-Valat M. (2023). SnowballC: Snowball Stemmers Based on the C ‘libstemmer’ UTF-8 Library. R package version 0.7.1. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=SnowballC (Accessed October 5, 2025).

Boxall B. (2007). Grizzlies no safer than average bears (Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles Times). Available at: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2007-mar-23-na-bears23-story.html (Accessed October 8, 2024).

Casola W. R., Beall J. M., Nils Peterson M., Larson L. R., Brent Jackson S., Stevenson K. T. (2022). Political polarization of conservation issues in the era of COVID-19: An examination of partisan perspectives and priorities in the United States. J. Nat. Conserv. 67, 126176. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2022.126176

Chaffin B., Gosnell H., Cosens B. (2014). A decade of adaptive governance scholarship: Synthesis and future directions. Ecol. Soc. 19. doi: 10.5751/ES-06824-190356

Chaney R. (2017a). Grizzly committee works on outreach as bear sightings rise. Missoula, MT: The Missoulian. Available at: https://missoulian.com/news/local/grizzly-committee-works-on-outreach-as-bear-sightings-rise/article_53714774-dd73-5e42-a9e1-c0050d0d9546.html (Accessed October 8, 2025).

Chaney R. (2017b). Lawsuits coming over plan to remove Yellowstone grizzles from endangered list. Missoula, MT: The Missoulian. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1915042398/abstract/B7570977544E4EF2PQ/1 (Accessed October 8, 2025).

Chaney R. (2018a). Record roadkill: Grizzly bears probe limits of highway tolerance. Missoula, MT: The Missoulian. Available online at: https://missoulian.com/news/local/record-roadkill-grizzly-bears-probe-limits-of-highway-tolerance/article_70da58b5-a343-54e6-86e0-41974fa8b7bd.html (Accessed October 8, 2025).

Chaney R. (2018b). Grizzly bear managers ponder Endangered Species Act plans after court setback. Missoula, MT: The Missoulian. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2228445281/citation/3466908D1DFD46BBPQ/1 (Accessed October 8, 2025).

Chaney R. (2021). Gianforte petitions for grizzly delisting. Missoula, MT: The Missoulian. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2607087116/citation/BAAE249AB51F4632PQ/1 (Accessed October 8, 2025).

Chapron G., López-Bao J. V. (2014). Conserving carnivores: politics in play. Science 343, 1199–1200. doi: 10.1126/science.343.6176.1199-b

Charmaz K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: SAGE publications.

Christie M. R., Knowles L. L. (2015). Habitat corridors facilitate genetic resilience irrespective of species dispersal abilities or population sizes. Evolutionary Appl. 8, 454–463. doi: 10.1111/eva.12255

Cook C. N., Sgrò C. M. (2017). Aligning science and policy to achieve evolutionarily enlightened conservation. Conserv. Biol. 31, 501–512. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12863

Department of the Interior (2023). Biden-harris administration takes steps to increase co-stewardship opportunities, incorporate indigenous knowledge, protect sacred sites (Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior). Available at: https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/biden-harris-administration-takes-steps-increase-co-stewardship-opportunities (Accessed October 5, 2024).

Diaz J. (2023). “U.S. Considers lifting protections for grizzly bears near two national parks,” in The New york times (New York, NY: New York Times Company). Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2772038950/citation/DACA90EC56874ABCPQ/1 (Accessed October 5, 2024).

Endangered Species Act of 1973, 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq (1973). Available at: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1531.

Epstein K., Smutko L. S., Western J. M. (2018). From “Vision” to reality: emerging public opinion of collaborative management in the greater yellowstone ecosystem. Soc. Natural Resour. 31, 1213–1229. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2018.1456591

Fazio M. (2020). “Grizzly bears around Yellowstone can stay on endangered species list, court rules,” in The salt lake tribune. (Salt Lake City, Utah: The Salt Lake Tribune). Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2422954004/citation/3799811A7A774A43PQ/1 (Accessed October 5, 2024).

Fish and Wildlife Service & National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (n.d) 02-110-24 policy for information standards under the endangered species act. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1994-07-01/html/94-16022.htm.

Fortems C. (2001). Bear necessities: Taking stock of grizzlies in the Cascades. (Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada: Kamloops Daily News). Available at: https://uwyo.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/bear-necessities-taking-stock-grizzlies-cascades/docview/358314528/se-2 (Accessed: October 5, 2024).

Frazer G. (2001). Testimony of Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species, Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior, before the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, Subcommittee on Fisheries, Wildlife, and Water on Listing and Delisting Processes of the Endangered Species Act on Listing and Delisting Processes of the Endangered Species Act | (Washington D.C.: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. FWS.Gov). Available at: https://www.fws.gov/testimony/listing-and-delisting-processes-endangered-species-act (Accessed October 8, 2024).

Governor’s Office (2021). Gov. Gianforte: montana petitioning federal government to delist NCDE grizzly bears (Helena, MT: State of Montana Newsroom). Available at: https://news.mt.gov/Governors-Office/Gov-Gianforte-Montana-Petitioning-Federal-Government-to-Delist-NCDE-Grizzly-Bears (Accessed: October 5, 2024).

Grizzly bears should survive being delisted (2016). Carlsbad Current - Argus. https://uwyo.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/grizzly-bears-should-survive-being-delisted/docview/2198696869/se-2.

Hamilton L. C., Lambert J. E., Lawhon L. A., Salerno J., Hartter J. (2020). Wolves are back: Sociopolitical identity and opinions on management of. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2, e213. doi: 10.1111/csp2.213

Hosseiny Marani A., Baumer E. P. S. (2023). A review of stability in topic modeling: metrics for assessing and techniques for improving stability. ACM comput (56(5: Surv.). doi: 10.1145/3623269

Hovardas T. Ed. (2018). Large Carnivore Conservation and Management: Human Dimensions (1st ed.). (London, UK: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781315175454

Hughes T. (2018). Fate of 22 grizzly bears up to judge’s decision. Should trophy hunters be allowed to kill? USA today. Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2264394583/citation/8D047002261D4975PQ/1 (Accessed October 8, 2024).

Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC) (2016). About us—Interagency grizzly bear committee (IGBC). Available online at: https://igbconline.org/about-us/ (Accessed October 5, 2024).

IPCC (2012). Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaption: Special report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press).

Keiper A. (2004). Science and congress. New Atlantis 7, 19–50. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43152145.

Kelly R. P. (2010). The use of population genetics in endangered species act listing decisions comment. Ecol. Law Q. 37, 1107–1158. doi: 10.15779/Z38255P

Kuehl B. L. (1993). Conservation oglbiations under the endangered species act: A case study of the yellowstone grizzly bear Vol. 64 (University of Colorado Law Review), 607.

Kuglin T. (2021). Bill grapples with expanding grizzly bear territory. (Billings, MT: The Billings Gazette). Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2479913438/citation/2A6BB2F38E84157PQ/1 (Accessed October 5, 2024).

Lamka G. F., Willoughby J. R. (2024). Habitat remediation followed by managed connectivity reduces unwanted changes in evolutionary trajectory of high extirpation risk populations. PloS One 19, e0304276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0304276

Lowe W. H., Allendorf F. W. (2010). What can genetics tell us about population connectivity? Mol. Ecol. 19, 3038–3051. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04688.x

Lynch H. J., Hodge S., Albert C., Dunham M. (2008). The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: challenges for regional ecosystem management. Environ. Manage. 41, 820–833. doi: 10.1007/s00267-007-9065-3

Montero D. (2017). THE NATION; U.S. @ to lift some grizzly protections; Conservationists and tribes decry the move delisting the bear in Yellowstone park (Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles Times). Available at: https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-grizzly-bears-20170623-story.html (Accessed October 5, 2024).

Murdock J. (2023). Third try to repopulate grizzlies. (Billings, MT: The Billings Gazette). Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2874652983/citation/5A048838B55F418APQ/1 (Accessed October 5, 2024).

Nagle J. C. (2017). “The original role of states in the endangered species act,” in Idaho law review, vol. 52. (Moscow, Idaho: Idaho Law Review). Available at: https://case.edu/law/sites/case.edu.law/files/2019-10/The%20Original%20Role%20of%20States%20in%20the%20Endangered%20Species%20Act%20%282017%2C%2041%20p.%29.pdf (Accessed October 8, 2024).

National Park Service (2024). Tribal affairs & Partnerships—Yellowstone national park (U.S. National park service). Available online at: https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/management/tribal-affairs.htm (Accessed October 8, 2024).

Parker I. D., Feldpausch-Parker A. M. (2013). Yellowstone grizzly delisting rhetoric: An analysis of the online debate. Wildlife Soc. Bull. - Rec. Set Up In Error 37, 248–255. doi: 10.1002/wsb.251

Roberts M. E., Stewart B. M., Tingley D. (2019). stm: an R package for structural topic models. J. Stat. Software 91, 1–40. doi: 10.18637/jss.v091.i02

Saldaña J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3E [Third edition]) (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications).

Salvatori V., Balian E., Blanco J. C., Carbonell X., Ciucci P., Demeter L., et al. (2021). Are large carnivores the real issue? Solutions for improving conflict management through stakeholder participation. Sustainability 13 (8), 4482. doi: 10.3390/su13084482

Sen. Enzi Issues Statement on Federal Court Decision to Return Grizzly Bears to Endangered Species List (2018). US Fed News Service, Including US State News https://uwyo.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/wire-feeds/sen-enzi-issues-statement-on-federal-court/docview/2111948425/se-2 (Accessed October 5, 2024).

Thompson J. T. (2016). The first Sagebrush Rebellion: What sparked it and how it ended. Available online at: https://www.hcn.org/articles/a-look-back-at-the-first-sagebrush-rebellion (Accessed October 5, 2024).

US EPA (2013) Summary of the endangered species act [Overviews and factsheets]. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-endangered-species-act.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (2021). U.S. Fish and wildlife service proposes delisting 23 species from endangered species act due to extinction. Available online at: https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/us-fish-and-wildlife-service-proposes-delisting-23-species-endangered-species-act-due (Accessed October 5, 2024).

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (n.d). The endangered species act at 50: More important than ever. Available at: https://www.fws.gov/library/collections/endangered-species-act-50-more-important-ever (Accessed December 3, 2024).

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (2023). Listed species summary (Boxscore). Available online at: https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/report/boxscore (Accessed October 5, 2024).

van Eeden L. M., Rabotyagov S., Kather M., Bogezi C., Wirsing A. J., Marzluff J. (2021). Political affiliation predicts public attitudes toward gray wolf (Canis lupus) conservation and management. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 3, e387. doi: 10.1111/csp2.387

Wilkinson T. (1999). Grizzly roars back from brink. (Boston, Massachusetts: The Christian Science Monitor). Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1023771864?sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers (Accessed October 8, 2024).

Keywords: endangered species, Endangered Species Act (ESA), public policy & governance, Grizzly bear (Ursus arctos), carnivore management and policy

Citation: Mollett S, Wheeler I, Asay B, Holbrook J, Furland T, Manire H, Miranda Paez A, Scearce SS, Spoonhunter T, Stoellinger T, Willoughby JR and Dunning KH (2025) Delisting the Grizzly bear from the Endangered Species Act: shifting politics and political discourse in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6:1508158. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1508158

Received: 08 October 2024; Accepted: 25 February 2025;

Published: 16 April 2025.

Edited by:

Barry Noon, Colorado State University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Mollett, Wheeler, Asay, Holbrook, Furland, Manire, Miranda Paez, Scearce, Spoonhunter, Stoellinger, Willoughby and Dunning. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kelly H. Dunning, a2VsbHkuZHVubmluZ0B1d3lvLmVkdQ==

Sofia Mollett1

Sofia Mollett1 Iree Wheeler

Iree Wheeler Janna R. Willoughby

Janna R. Willoughby Kelly H. Dunning

Kelly H. Dunning