- 1The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, New York, NY, United States

- 2Department of Criminal Justice Farmingdale State College (SUNY), Farmingdale State College, New York, NY, United States

Introduction: This study profiles and analyses 1,099 wildlife crime prosecutions in Kenya to understand the prevalence of crimes, species involved, arrest patterns, prosecution and sentencing outcomes.

Methods: A descriptive and temporal analysis of the data is conducted to understand trends.

Results: Findings indicate that illegal grazing offenses were the most prevalent offenses followed by trophy and bushmeat related offenses. The elephant was the species most impacted by wildlife crime. Temporal results show that wildlife crimes such as poaching, illegal grazing and extraction offences peak during dry seasons and decrease in wet seasons. Most prosecutions involved single offenders and 90% of offences brought against them returned a guilty verdict. The penalty of imprisonment or payment of a fine was the most common sentence with an average imprisonment and fine for endangered species being 4 years 11 months or 340$ and 1 year 3 months and 126$ for non-endangered species respectively. We also found evidence of crime convergence with offenders engaging in other serious crime or more than one species.

Discussion: Illegal grazing offences surpassed other offences reflecting broader land use challenges between pastoralism and conservation. The temporal variations reflect the need for adaptative enforcement to address the human – wildlife competition during dry seasons. Crime convergence together with predominance of single offender prosecutions suggests that law enforcement may disproportionately target low level players while larger and organized players remain underrepresented in prosecution outcomes. While harsher penalties for crimes involving endangered species compared to lesser penalties for non-endangered species is aligned with theprinciples of proportionality, the overall low level of fines raises questions about their deterrence given the high economic value driving wildlife crime. Strengthening the law enforcement response requires a livelihood sensitive approach, strong deterrence and sentencing that matches the harm caused by wildlife crimes.

1 Introduction

A diverse array of wildlife species that captivate the world are found in Kenya. From elephants that freely roam, giraffes that tower over everything, and big cats stalk the savannah. These species draw countless tourists who contribute about 10% to the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employing over half a million Kenyans directly (Bitok, 2019). Despite its enchanting beauty and the rigorous efforts to protect its natural treasures, Kenya faces an escalating threat - wildlife crime.

Poaching, illegal trade, and habitat destruction undermine conservation efforts and jeopardize the survival of these charismatic fauna (Leakey and Morell, 2002; Gastrow, 2011; EIA, 2016; USAID, 2017). The poaching of endangered wildlife species and their related illicit trade have drawn global attention. In the period between 2009 and 2014, Kenya was considered a primary exit point for illegal ivory from Africa. Kenya was among countries infamously labelled as the “Gang of Eight”, a term alluding to eight countries identified as the primary drivers and facilitators of illegal wildlife trade (Cruise, 2014; Otieno, 2013). To turn the tide against wildlife crime, Kenya enacted the Wildlife Conservation and Management Act in 2013 that included new offences and enhanced penalties designed to empower law enforcement in their efforts to bring poachers and traffickers to justice (Kenya, 2010; Government of Kenya, 2014; Ogutu et al., 2016; Ngetich, 2016; Karanja, 2019). Further reforms established a wildlife crimes prosecution division within the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions in 2014, which was focused on anti-corruption and anti-wildlife crime capacity building of Kenya Wildlife Service rangers, prosecutors, magistrates and judges; establishment of a wildlife forensic laboratory; and the installation of scanners and deployment of sniffer dogs at border entry points (Government of Kenya, 2013; Nuwer, 2016; Weru, 2016; Karanja and Matsui, 2018; Kenya, 2013; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2016; Wasser et al., 2022; WildlifeDirect, 2018).

This current study explores the complex web and the nature of wildlife crime in Kenya, specifically after this period of wildlife legislative changes, enhanced enforcement, and wildlife prosecution reforms in Kenya. This study analyzes the prosecution of wildlife crime offences charged in magistrate’s courts in Kenya to determine (1) the prevalence and trends in wildlife crimes; (2) wildlife species involved in prosecuted cases; (3) arrest and prosecution patterns of wildlife offenders; (4) conviction rates, and (5) sentencing outcomes of wildlife crime prosecutions.

2 Prior wildlife crime research in Kenya

Like much of Africa, Kenya is an under-researched country with scant literature available that examines crime, especially wildlife crime. Much of the research on wildlife crime has focused on its impact on conservation plans of endangered species and their impacts on the legal wildlife trade (Cheloti and Mulu, 2023). When research has focused on wildlife crime, academics have generally shown a bias to research mainly iconic endangered species, such as elephants and rhinoceroses (Milledge, 2007; Chege, 2015; Karanja and Matsui, 2018; Wasser et al., 2018).

Existing literature examining wildlife crime primarily includes reports produced by non-governmental organizations and analysis reports released by the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS). WildlifeDirect, a nonprofit organization in Kenya, carried out court surveys to measure and evaluate how effectively the new Wildlife Conservation and Management Act was being enforced by various actors by examining courtroom trials between 2014 and 2020. WildlifeDirect, while documenting courtroom trials from eighteen courts in 2014, found that only 10% of prosecutions successfully resulted into convictions, only 4% of these convictions led to imprisonment and that arrested and prosecuted offenders were mainly pleading guilty and paying the low fine penalties upon conviction (WildlifeDirect, 2020). Essentially, the law was not acting as a deterrent to wildlife crime.

Subsequent reports produced in 2018 and 2020 showed that arrests progressively increased, and convictions in wildlife crime cases increased from 44% and 98% respectively (WildlifeDirect, 2018; 2020). These reports mainly demonstrated that minor wildlife crimes were swiftly resolved with a progressive improvement in convictions and case completion. These findings were corroborated by a study conducted by Halliday et al. (2022) who examined 247 court room trial outcomes of elephant ivory-related cases between 2016 and 2019. They found that conviction rates were at 88%, but sentences in terms of fines and imprisonment were inconsistent across all major wildlife crime offences with various judges imposing differing amounts in fines and differing lengths of imprisonment.

Although existing research offers an insight into the status of wildlife crime, there remains an opportunity and need to examine underlying insights on the typology of offences, relationships between wildlife species involved, characteristics of co-offending, and the geographic distribution of crimes within Kenya. In this study, we build on WildlifeDirect’s (2018) research findings and use their dataset to further examine wildlife crime through a wider analytical lens. We chose this dataset for its completeness, as it is the only publicly available and comprehensive national dataset on wildlife crime in Kenya.

3 Methodology

In this study, we analyze the prosecution of wildlife crime offences charged before courts in Kenya to determine (1) the prevalence and trends of wildlife crimes; (2) wildlife species involved in prosecuted cases; (3) arrest and prosecution patterns of wildlife offenders; (4) conviction rates, and (5) sentencing outcomes of wildlife crime prosecutions.

3.1 Identification of cases

The study builds upon prior research and considers offences brought under the Wildlife Conservation and Management Act between the years 2018 and 2019, relating to killing of wildlife, possession of live wildlife or their parts, possession of bushmeat and the breach of protected areas offences such as illegal entry into protected areas. The data used considers wildlife crime prosecutions charged at the magistrate’s court level and excludes incidents and reports made to law enforcement that have not been brought before court for formal prosecution. Additionally, the scope of the study is limited to offences brought under the Wildlife Conservation and Management Act and excludes offences related to forest and fisheries crime which fall under the Forestry Act and Fisheries Act respectively.

3.2 Data collection

Kenya lacks a centralized and accessible database that compiles and aggregates court records. As a result, court monitors under the Eyes in the Courtroom Project, a partnership between WildlifeDirect and the Judiciary Training Institute, physically visited one hundred and thirteen magistrate court stations administered by the Judiciary of Kenya during the months of January and February of 2020 (Kahumbu et al., 2018). They obtained access to the main case file registers that record all criminal cases registered from 1st of January 2018 and 31st December 2019 and extracted 1,099 wildlife crime court cases relating to 2,025 persons charged for various wildlife crime offences.

3.3 Data extraction

In this study, we extracted data about the; (1) accused person, (2) court case, and (3) offence level. Information on the accused persons included nationality, date of arraignment, identity, legal representation (with or without legal counsel), bail and bond details, and the arresting authority. Information on the court case included data on the number of accused persons, as well as the number and type of wildlife species involved. Lastly, data on offences included the nature of prosecuted offence, the nature of plea taken (guilty or not guilty), the outcome of prosecution (conviction, acquittal or withdrawal), and the sentencing outcomes (jail, fine, probation or community service orders).

3.4 Data coding

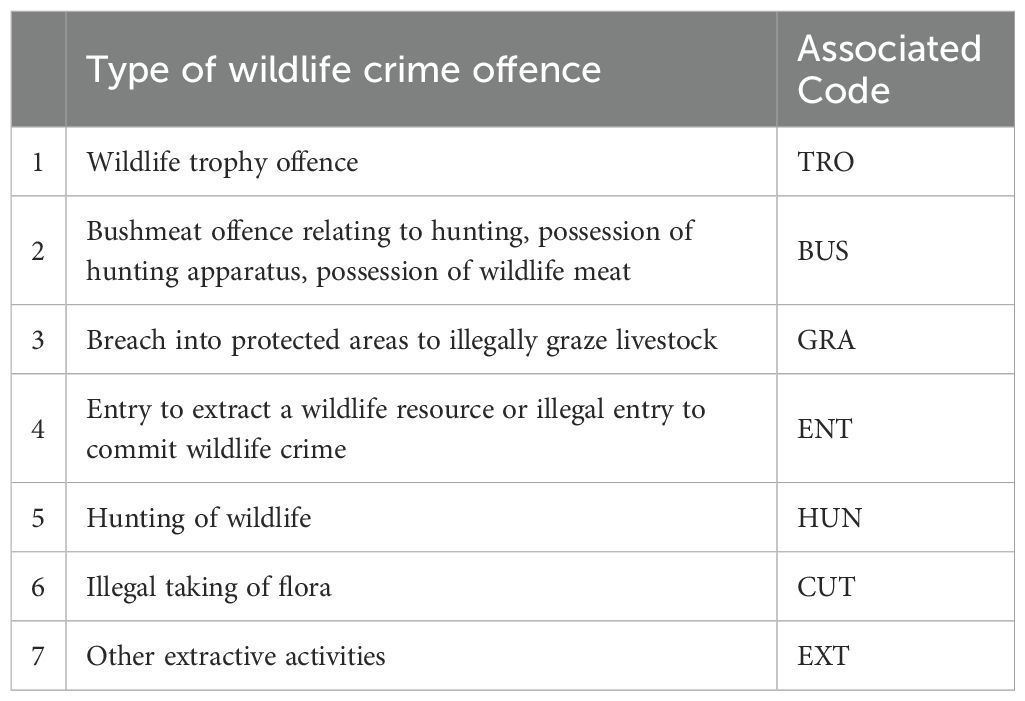

Data was collected from court cases and coded by; (a) individuals prosecuted in a case; (b)the location of the incident by town; (c) wildlife product or species involved in a case; (d) outcome of prosecution either acquittal, withdrawal, or conviction; and (e) sentencing outcome. The type of offence charged was coded depending on what type of wildlife crime it is as in Table 1 below.

After the data collection and coding, we performed statistical, spatial, and temporal analyses of prosecuted wildlife crime cases using STATA 17 and ArcGIS Pro. The descriptive statistics showed trends at the case, offense, and accused person’ levels. Specifically, these analyses focus on examining the distribution of offenders, locations of arrest, wildlife species involved, typology of offending, prosecution outcomes such as conviction and acquittal, and judicial outcomes such fines, imprisonment, community service, and probation.

4 Results of analysis

4.1 Characteristics of accused persons

This study findings indicate that bail and bond was offered to most of the accused persons, but only 3.7% of them could post bail and 10.7% of the suspects were released on secured bonds. About 93% of all accused persons were male, and only 0.3% of all accused persons had legal representation at the time of arraignment and took a plea for a wildlife offence.

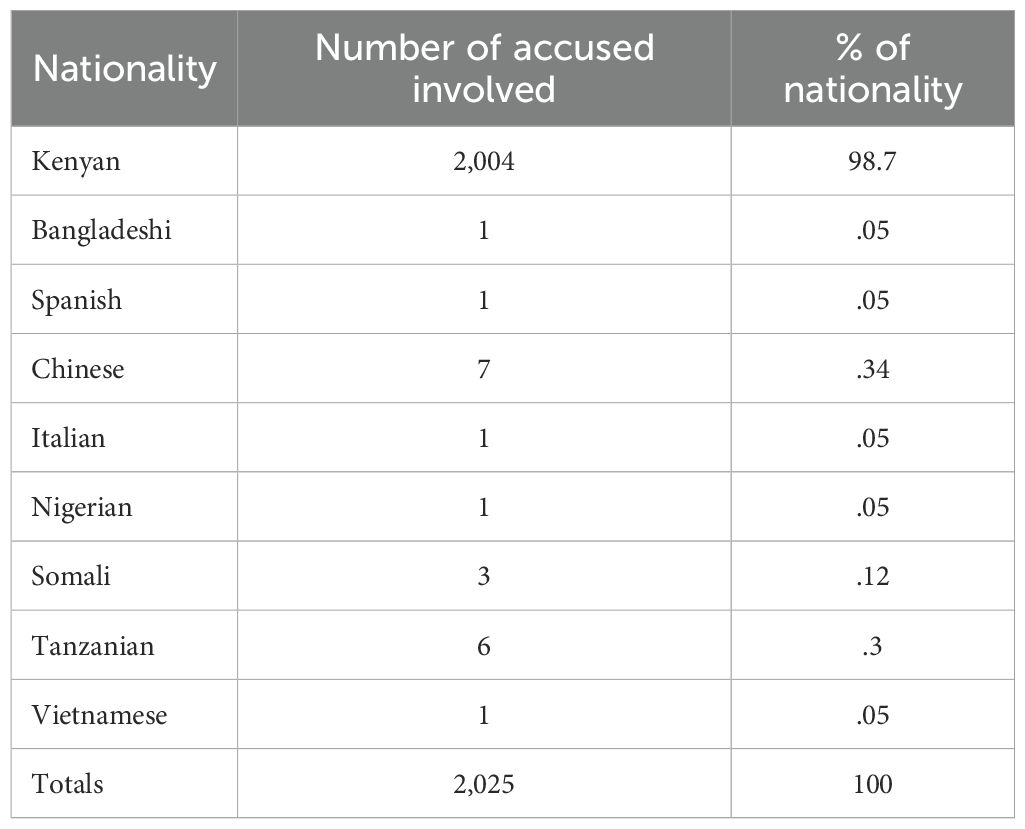

Table 2 shows information on the nationality of all 2,025 accused persons. About 98.7% were Kenyan and foreigners accounting for the remaining 1.3%.

4.2 Characteristics of species involved

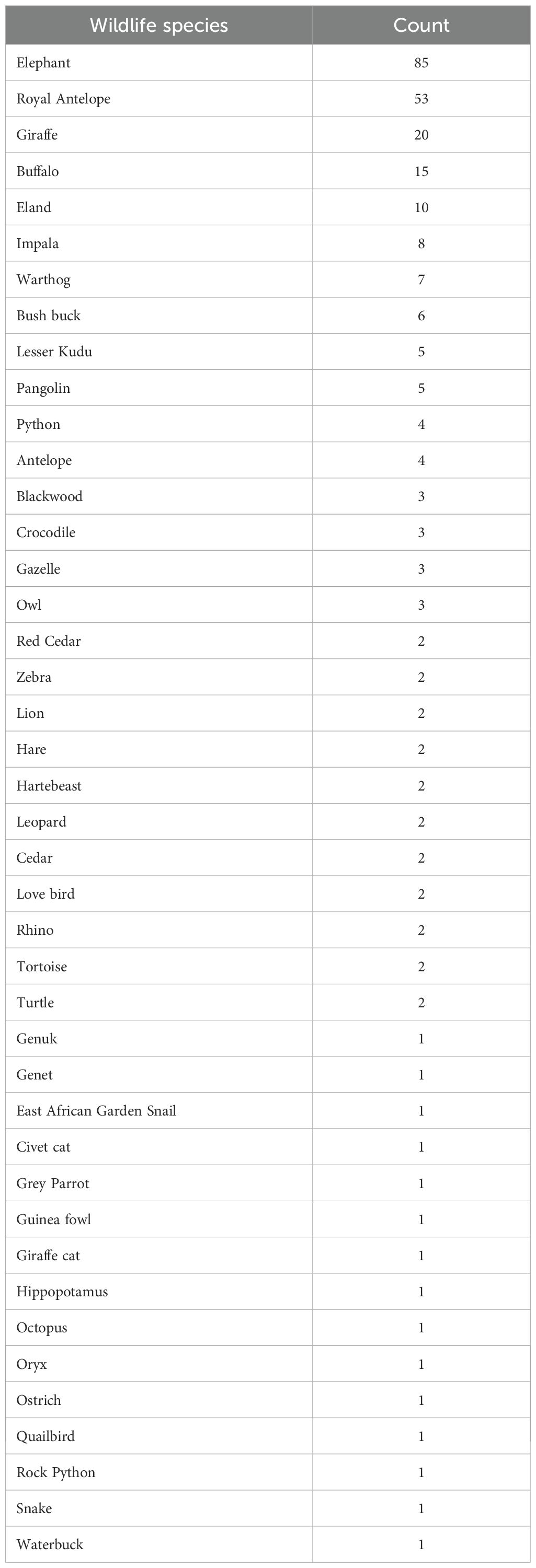

Wildlife crime impacted a variety of species. Table 2 shows that elephants are involved in the highest number of incidents or observations (n=85) which is over 1.5 times higher than the second species on the list, i.e. the royal antelope (n=53). The royal antelope and giraffes had relatively high number compared to all other species as represented in Table 3 below. Many other species have relatively few incidents or observations. The cumulative percentage shows that a small number of species account for most incidents/observations.

4.3 Characteristics of arrests

4.3.1 Analysis of arresting authority

Most of the arrests were made by the main law enforcement agencies, with Kenya Wildlife Service accounting for most of the arrests (98.7%, 1,394 arrests), National Police Service - 497 arrests, and Kenya Forestry Service - 25 arrests. Other arrests were originated by Sabuk, Lentille, Oljogi, Oserian and Aquila Conservancies and forwarded to Kenya Wildife Service.

4.3.2 Analysis of arrest locations

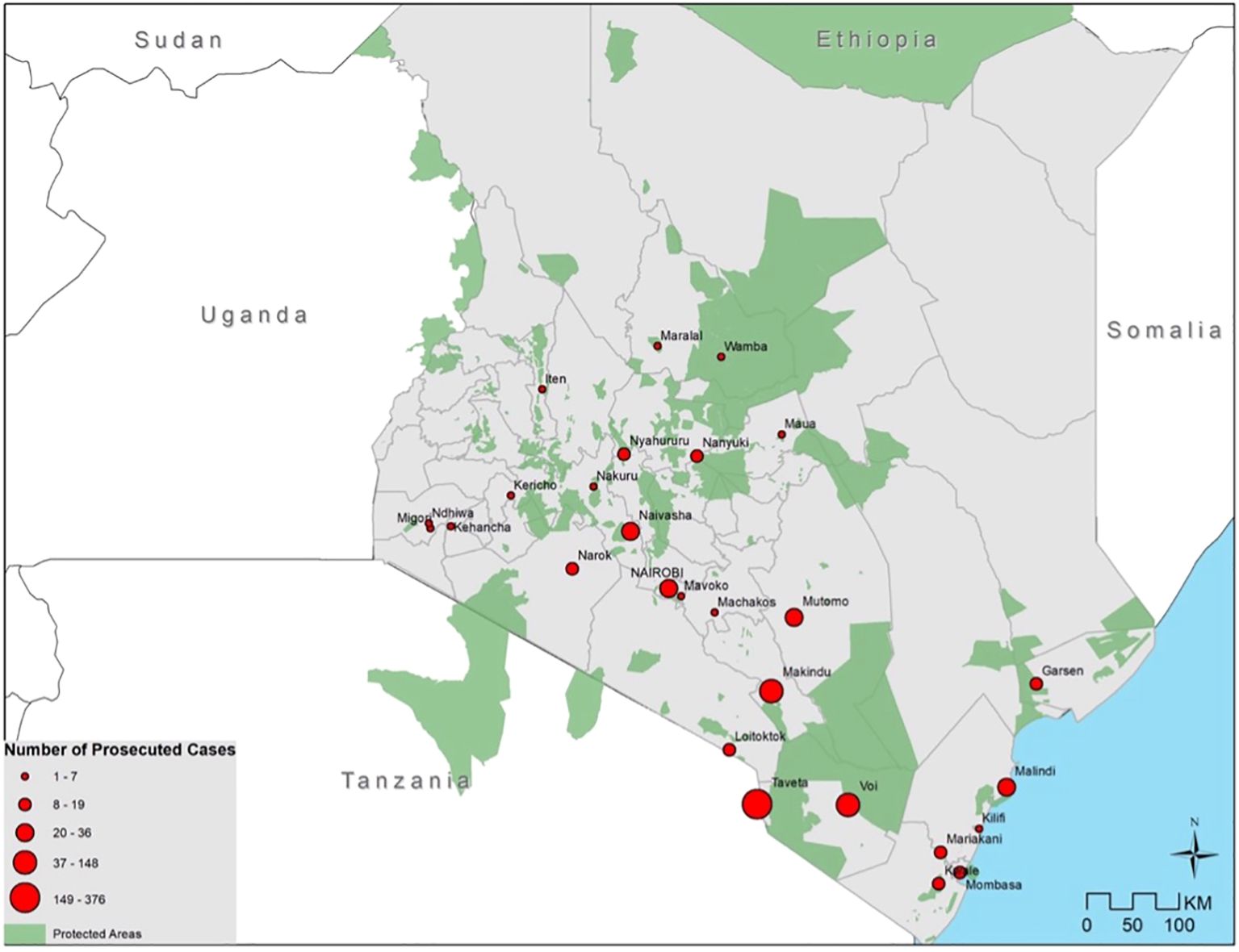

The location of arrests was spatially mapped to identify the locations with prevalence of wildlife crimes in Figure 1 below.

The wildlife crimes are most concentrated in Taveta, Voi, Malindi, Makindu, Naivasha, Mutomo and Nairobi towns. These towns border major protected areas, such as the Tsavo National Park (Voi, Taveta, Mutomo, and Makindu), the Nairobi National Park (Nairobi), and the Aberdares National Park (Naivasha). Taveta accounted for 34% of the cases and cumulatively, 14% of all the towns (n=8), experienced 80% of all the arrests, with the top four towns being Taveta (376), Makindu (148), Voi (146), and Butali (102).

4.4 Characteristics of offences and prosecutions

4.4.1 Nature of offending

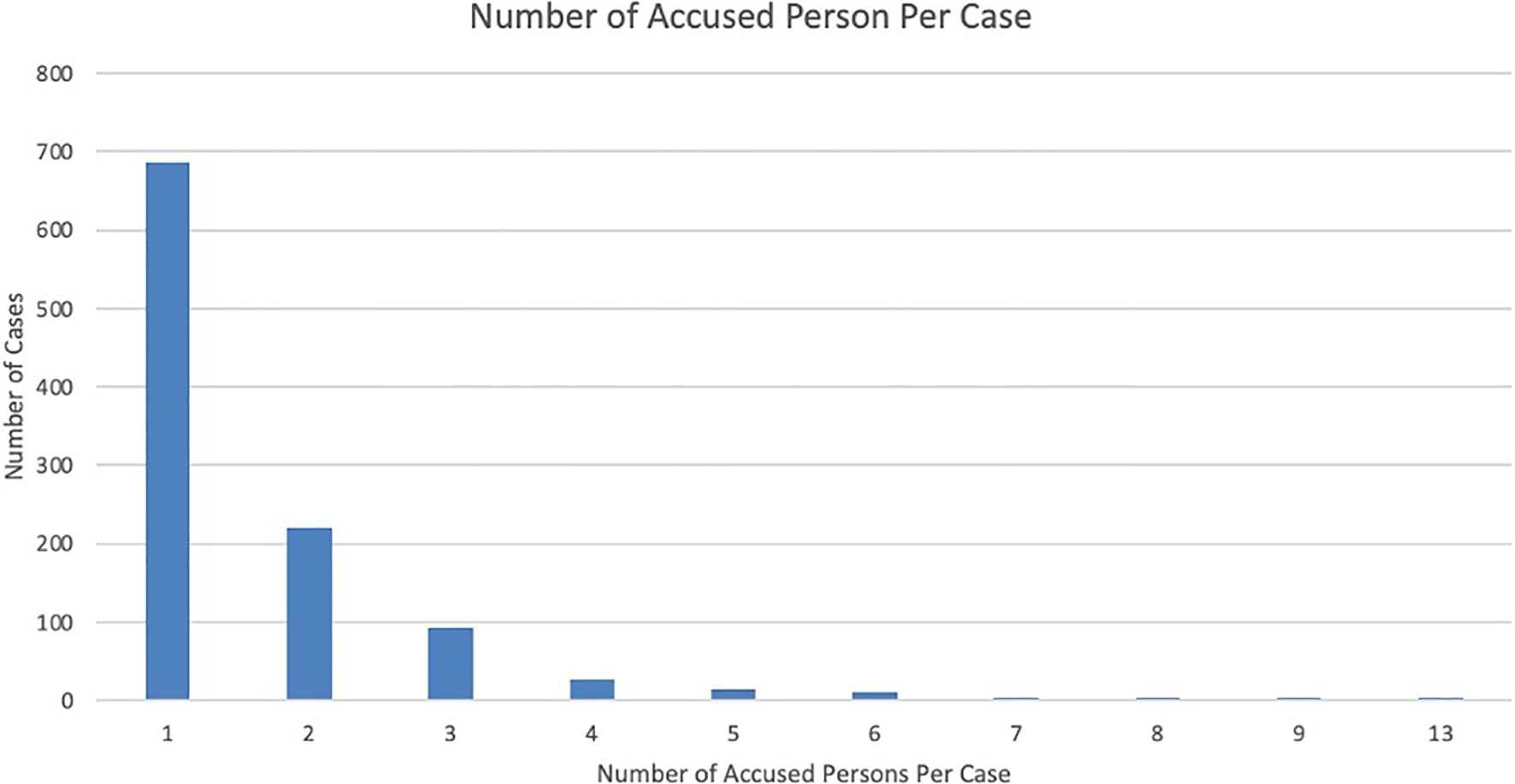

687 cases involved a single accused person, 220 cases involved two accused persons, 93 cases involved 3 accused persons, 40 cases involved 4 accused persons, 26 cases involved 5 accused persons and 14 cases involved six accused persons and 28 cases involved seven or more accused individuals in a single case as shown in Figure 2.

4.4.2 Type of prosecuted offences

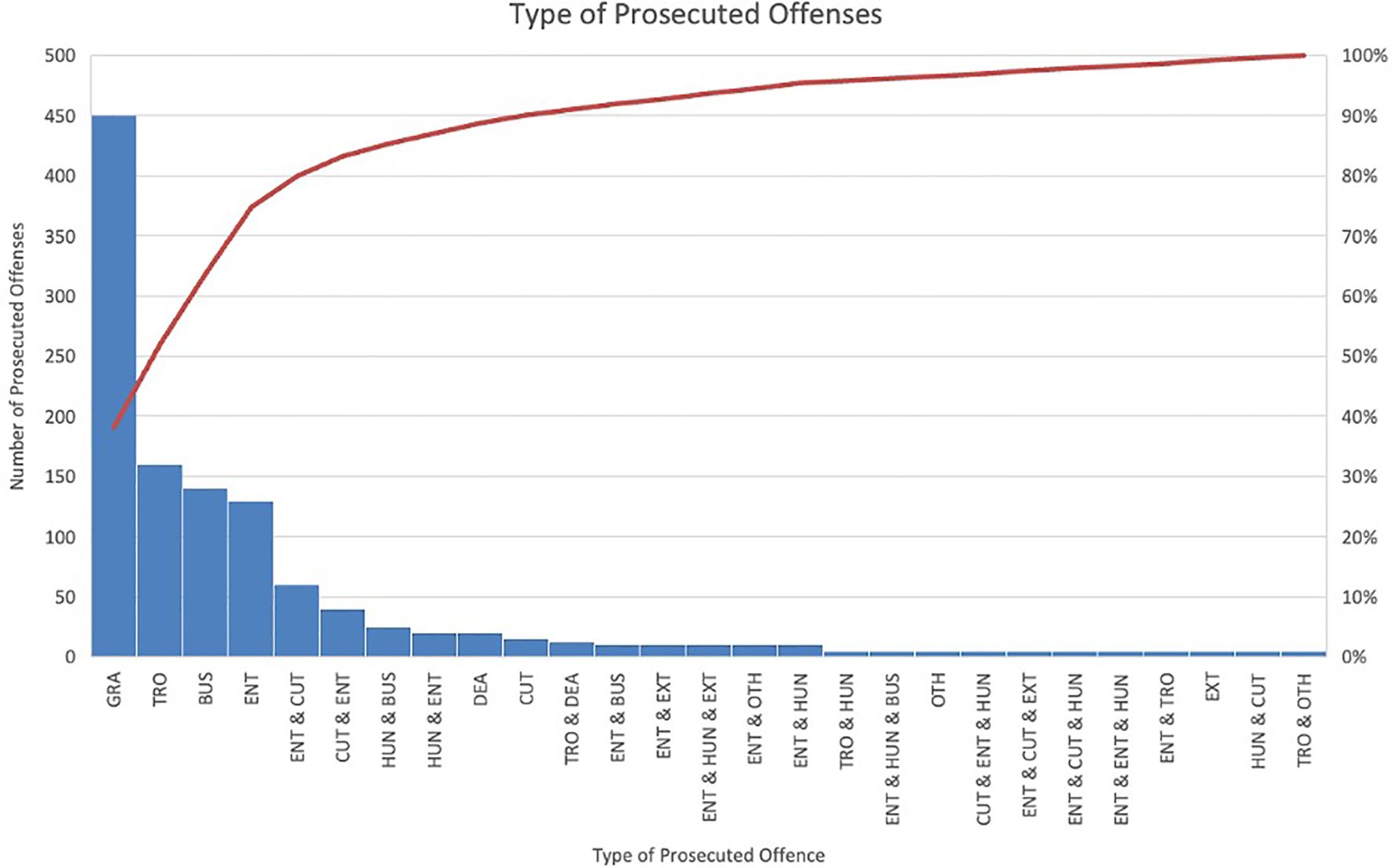

Each decision to charge an offence by a prosecutor is shown in Figure 3 below.

Grazing (GRA) offense has the highest number of cases (n=451), significantly more than any other offense type, suggesting it is a major issue. Trophy-related offences (TRO) is the second most common offense type (n=164), followed by bushmeat (BUS) (n=139) and illegal entry into national parks ENT (n=133). The steep increase at the beginning of the orange line indicates that a few offense types account for a large proportion of the cases. As the line flattens out, it shows that the remaining offense types contribute progressively smaller portions to the total cases.

Trophy-related offences were categorized as either dealing offences (relating to trading or processing wildlife products) or possession offences (constructive possession of wildlife products). Findings show that of the 164 TRO offences, 21 (13%) were dealing offences (DEA), and 143 (87%) offences related to possession offences. Figure 3 also shows that some offences were prosecuted together with other offences in the same case. Although accounting for few occurrences, 48 offences involved illegal entry (ENT) and cutting vegetation (CUT), illegal entry (ENT), illegal hunting (HUN) and extraction (EXT).

4.5 Characteristics of judicial outcomes

After the close of the prosecution case, 1,481 offences returned a guilty verdict; 136 offences were withdrawn by the prosecution, and 28 offences returned an acquittal verdict.

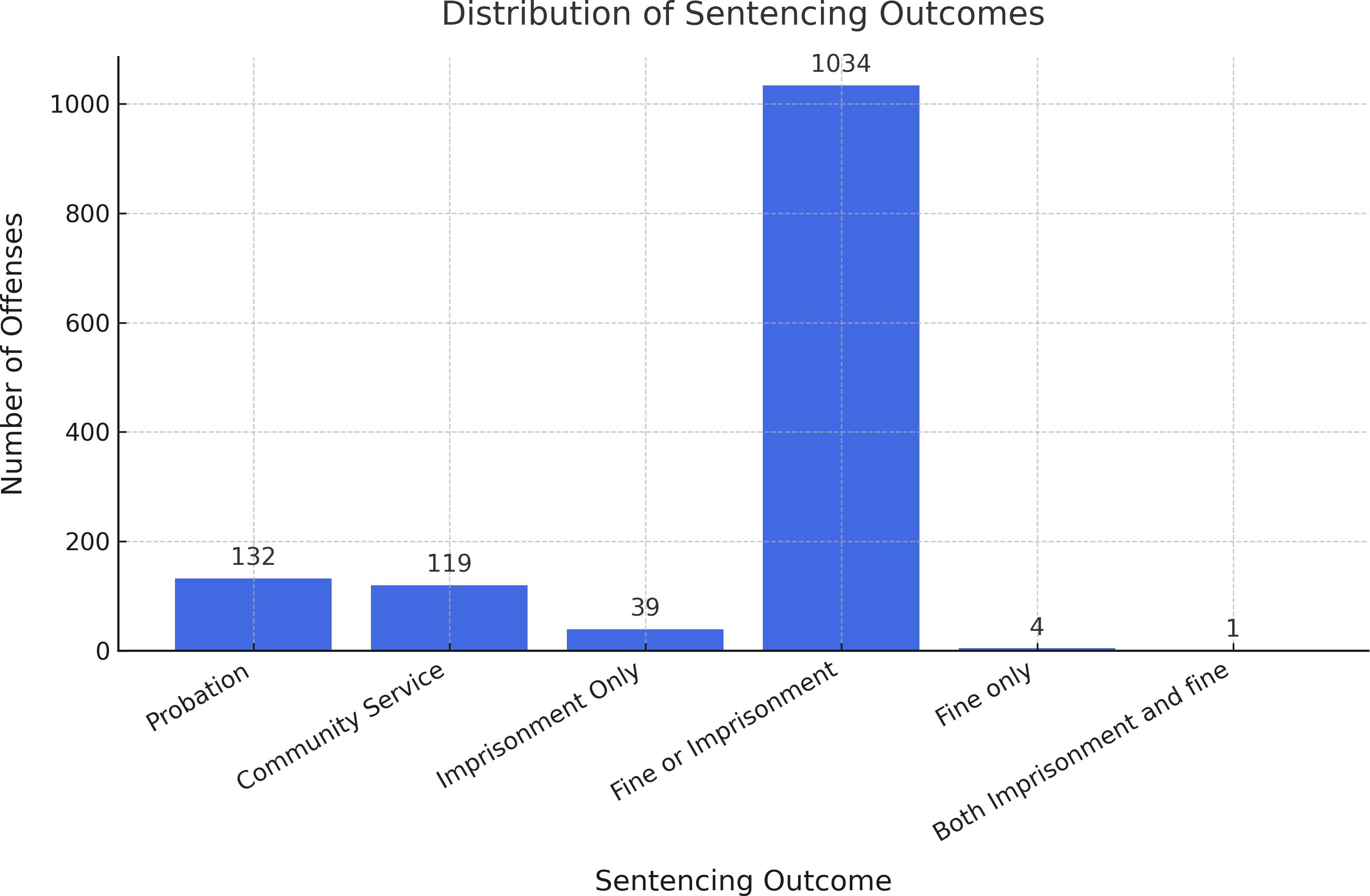

The most common and prevalent sentencing outcome is where convicts were offered either “Fine or imprisonment,” penalty with 1,034 occurrences as shown in Figure 4. 73% of these fine penalties were paid and convicted offenders avoided imprisonment. This sentencing outcome is over 10 times higher than the second and third most common sentencing outcomes, i.e. “probation” (n=132) and “community service” (n=119) instances. Sentences involving both a penalty of “imprisonment and fine” and just the payment of a “fine” are quite rare, recording only one (1) and four (4) instances, respectively. The penalty of imprisonment or payment of a fine resulted in an average imprisonment and fine for endangered species of 4 years 11 months or 340$ and 1 year 3 months and 126$ for non-endangered species respectively.

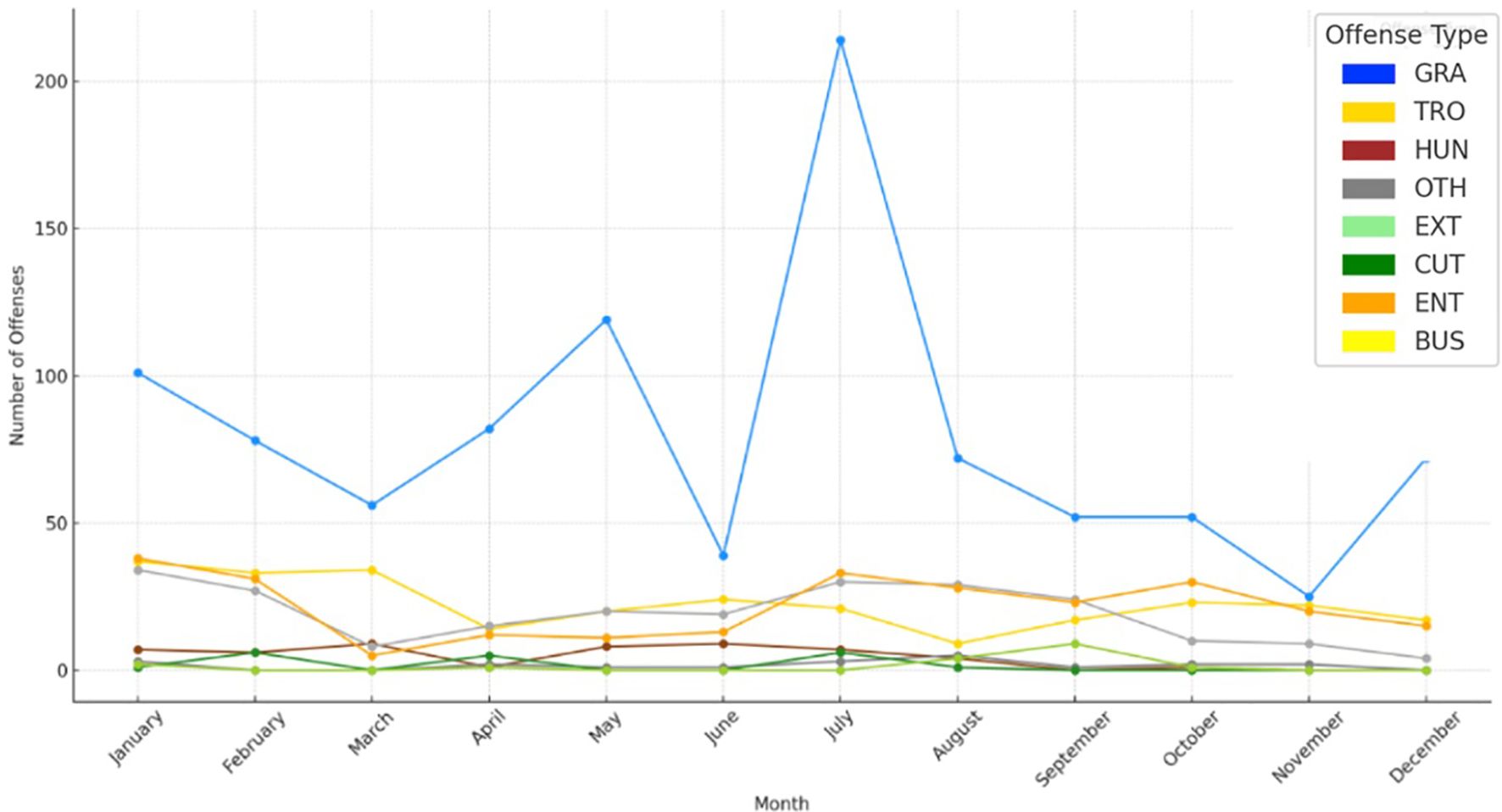

4.6 Temporal results

Throughout the year, wildlife-related offenses fluctuated, with some categories more prominent than others as shown in Figure 5. GRA offenses were consistently high, peaking significantly during January, December, May and June. TRO offenses were also frequent, though generally less so than GRA, with occasional increases in activity in January, July and October. ENT and CUT offenses appeared more sporadically, with increases in activity in April, July and October, while BUS offenses related to bush meat showed a noticeable rise in March, July and October.

5 Discussion of analysis

In this study we examined 1,099 court cases to understand wildlife crime offending patterns and characteristics, including the profile of offenders, the wildlife species involved, charges brought forward by the prosecution, and sentencing outcomes. We found that elephants are involved in the highest number of incidents or observations – with a count significantly higher than other species; elephants were followed in frequency by the royal antelope and giraffes. Additionally, this study shows evidence of multiple prosecuted offences in similar transactions with some offenses relating to more than one wildlife species. This finding aligns with the existing research on convergence of crimes and specialization of wildlife crime offenders (Anagnostou and Doberstein, 2022). This relationship between species poached and trafficked together indicates a multiple species convergence typology in wildlife crime. This is consistent with research in typologies of crime that has found that that wildlife offenders often poach or traffic different species in similar transactions, means and methods to maximize their rewards (ELI and JJCJ, 2023; Anagnostou and Doberstein, 2022; WJC, 2021).

The temporal analysis indicates that illegal grazing (GRA) offenses dominate most months, with significant peaks in January, December, May and June. The high number of breaches into protected areas to illegally graze livestock indicates a critical issue during these months. This is a finding consistent with studies that show increased incidences of entry in national parks to graze livestock during dry seasons, especially into Tsavo & Chyulu National Parks (Kioko et al., 2012; Maina and Nzengya, 2021). Livestock grazing might be driven by the scarcity of pasture outside protected areas, especially during these months that also intersect with Kenya’s hot and dry seasons (Waweru and Oloiloboo, 2013). Trophy-related offenses show consistent activity throughout the year, with notable peaks in January, July and October. Bushmeat offences show steady occurrences each month and spikes in March, July and October. Illegal entry offences (ENT) peak in April, July and October, while hunting and extraction offenses have minimal activity with occasional spikes. These offenses have relatively low occurrences, suggesting these activities are less influenced by seasonal changes and are more sporadic.

The findings related to the locations of arrests show that Taveta, Makindu, Butali, Voi, Butali, Mutomo, Naivasha, Nairobi, Malindi, and Loitoktok had most arrests, and cumulatively accounted for over 80% of the arrests, indicating that a small number of towns account for a large portion of the total wildlife crimes. This finding aligns with the “law of crime concentration” which is an empirical observation that argues that crime concentrates at very small units of geography (Weisburd et al., 2012). This also aligns with crime pattern theoretical propositions and research that asserts that crimes, especially wildlife crimes, are not normally distributed and are geographically clustered and concentrated (Kurland et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021).

Many of the prosecuted cases involved multiple accused individuals, which might indicate coordination among offenders. However, the prosecution did not utilize legal tools that draw on conspiracy or organized crime charges. This is a missed opportunity in addressing the structured and potentially syndicated – based nature of wildlife offending. The examination of prosecution outcomes show that prosecuted offences returned a 90% conviction rate, with 7% offences withdrawn and 3% of the offences returning an acquittal. It is important to note that almost 84% of these outcomes related only to illegal grazing (GRA) offences.

The analysis of average imprisonment terms and fines for each offence shows that judicial officers were imposing lower sentences than those set in law. Imprisonment terms and fines were on average 60% and 47% lower respectively than those prescribed in the Wildlife Act. These low penalties do not create a strong deterrence to crime. These minimum penalties are set to guide judicial officers on the minimum punishment expected in law. Potential explanations found in a few cases show that judicial officers are departing from sentencing provisions in the Wildlife Act and applying provisions of the Community Service Orders Act, No. 10 of 1998 which allow judicial officers to sentence convicted offenders to lower sentences in public interest or the interests of justice.

The fact that only 0.3% of accused persons in wildlife crime cases secured legal representation is deeply concerning. It raises serious questions about access to justice, fair trial rights, and whether these individuals fully understand the charges against them or the legal consequences they might face upon conviction. Given the complexity of wildlife laws and the severe penalties often involved, the lack of legal representation could potentially lead to wrongful convictions and disproportionately harsh sentences since accused persons may not know how to understand and navigate the criminal trial process. In addition, a 68% rate of guilty pleas upon arraignment reflects a significant portion of cases being resolved without the need for a formal trial. None of these pleas were negotiated by the prosecution, which implies accused persons would rather plead guilty and face a sentence rather than challenge the evidence in court which has broad implications for the efficiency and perception of the criminal justice system. Without legal advice, an accused person may be more likely to plead guilty, even if there might be viable defenses, because they might not fully understand their options or the legal proceedings (Peay and Player, 2018; Erentzen et al., 2021).

As with all research, we faced some limitations. Firstly, we relied on secondary data collected from court cases aggregated and catalogued by Kenya’s Judiciary. We anticipated data quality issues and performed data cleaning to correct errors and missing data. Secondly, we acknowledge that we are using data from court cases relating to only reported incidents. We do not have the benefit of unreported wildlife crime cases. Nevertheless, this data remains the only comprehensive and publicly accessible dataset that we can draw meaningful and reliable conclusions from.

Wildlife crime is emerging as a critical concern especially due to the organized crime elements involved. Even more unique, unlike other crimes, is the notion that once wildlife is poached, the animal species is often long dead before we can bring the accused person to justice. This makes crime prevention a paramount conservation priority. To meet this need, it is imperative to consider crime science approaches availed by environmental criminology to devise targeted interventions. A key framework for prevention of crime that emerges from environmental criminology is Situation Crime Prevention (SCP). This framework is based on three crime prevention theories; (a) the rational choice perspective, (b) the routine activities approach, and (c) the geometry of crime theory, and seeks to reduce crime opportunities by increasing the risk of detection and reducing rewards in the immediate environment that potential offenders find themselves in (Clarke, 1983; Cornish and Clarke, 2003).

SCP focuses on reducing the opportunities for crime rather than attempting to change the underlying motivations of offenders in five main ways broken down in twenty-five different prevention techniques. The potential to design simple and yet effective preventative measures is the main attractiveness of SCP (Huisman and Van Erp, 2013), with dominant research showing the utility of SCP in preventing various forms of wildlife crime (Huisman and Van Erp, 2013; Pires and Moreto, 2011; Lemieux and Clarke, 2009), Petrossian, 2012; 2015; Kurland et al., 2017; Delpech et al., 2021).

SCP strategy potentially offers Kenya a formalized method of combating wildlife crime by making offenses riskier, more burdensome, and less rewarding. By the application of the five SCP fundamental strategies—increasing the effort, increasing the risks, reducing the rewards, reducing provocations, and removing excuses—some proposals for crime prevention are set out below.

5.1 Increasing the extent of effort required to offend against wildlife

Law enforcement could implement strategies that it more difficult for criminals to conduct illegal activities. This can be done by strengthening security in protected areas, bolstering border control, and reinforcing inspections at major transit points (airports, seaports, and borders) to monitor for smuggling of wildlife products.

5.2 Increasing the chances of detection and arrest

Wildlife offenders are more likely to act where they think they can get away with crime and thereby, increasing their likelihood of being caught is a good way of deterring crime. This can be done by increasing cooperation between law enforcement agencies, local communities, and informants to improve intelligence gathering on poaching operations. Also, rewarding local communities to act as the “eyes and ears” of conservation organizations in reporting suspicious behavior and providing whistleblower mechanisms that support unanimous and protected cooperation.

5.3 Reducing the rewards of wildlife crime

If poaching and trafficking are less profitable, fewer criminals will be motivated to commit these offenses. Interventions could involve activities that undermine illegal markets and increase sanctions against buyers and sellers of illegal wildlife products, transporting, shipping, clearing and forwarding companies.

5.4 Reducing stimuli that drive wildlife crime

Reducing factors that drive individuals towards illegal activities can reduce offenses. This can potentially be solved through poverty alleviation schemes that incorporate ecosystem service payments or sharing of tourism revenue. Communities who are benefiting from wildlife would be more invested in the protection of the same wildlife. For example, in relation to illegal grazing, communities can be sensitized on use of designated grazing banks. It can also be achieved by solving human-wildlife conflict by implementing compensation schemes for death and injury or for farmers whose livestock or crops are being destroyed by wildlife to prevent revenge or retaliatory killings of wildlife.

5.5 Removing excuses for involvement in wildlife crime

Elimination of excuses based on ignorance and necessity will be a deterrent to crime. It can be done through sensitization and awareness of communities, traders, shippers and transporters and tourists regarding the legal and ethical implications of wildlife crime (Didarali et al., 2022). Moreover, policy makers should aim to pass clear, enforceable laws that have no loopholes would-be criminals may exploit to escape.

6 Conclusion

In this study, we sought to explore the profile of prosecuted offenses, co-offending features, convergence of wildlife crimes, offense typology, prosecution, and sentence outcomes with respect to wildlife offenses in Kenya. We established the complexity of wildlife offenses as they related to offenders and type of wildlife involved. Our assessment demonstrates that wildlife crime in Kenya is not a singular event, but an intricate activity with connections to other forms of criminality posing economic and social vulnerability, and institution-based challenges.

Follow-up studies can employ the environmental criminology framework to extend this spatial-temporal trend identified in this study. Having the knowledge of where, when, and how these crimes are occurring can help develop targeted prevention programs. Empirically driven studies proposing evidence-based solutions will help place Kenya back on the conservation prosperity path. To counter wildlife crime, Kenya must move beyond reactive enforcement to proactive, integrated, and intelligence-led responses. More inter-agency coordination, improved judicial consistency, and increased community participation are necessary. In addition, coordination, multi-sectoral action, and a sustained effort are the only means by which the country can safeguard its unmatched biodiversity for future generations.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MS: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. GP: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anagnostou M. and Doberstein B. (2022). Illegal wildlife trade and other organised crime: A scoping review. Ambio 51 (7), 1615–1631. doi: 10.1007/s13280-021-01675-y

Bitok K. (2019). Sustainable tourism and economic growth nexus in Kenya: Policy implications for post-COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tourism. Entrepreneurship. 2), 123–138. doi: 10.35912/joste.v1i2.209/

Chege R. W. (2015). The illegal trade in wildlife resources and the implication for international security: A case of poaching of ivory in Kenya (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya).

Cheloti B. M. and Mulu F. (2023). Assessing the scope and impact of wildlife trade and poaching in Kenya: Conservation, enforcement, and socioeconomic dimensions. J. Afr. Interdiscip. Stud. 7*, 177–188.

Clarke R. V. (1983). Situational crime prevention: Its theoretical basis and practical scope. Crime. Justice. 4, 225–256. doi: 10.1086/449090

Cornish D. B. and Clarke R. V. (2003). Opportunities, precipitators and criminal decisions: A reply to Wortley’s critique of situational crime prevention. Crime. Prev Stud. 16, 41–96.

Cruise A. (2014). The notorious Gang of 8: The countries most responsible for the deaths of elephants. Conservation Action Trust. Available online at: https://www.conservationaction.co.za/the-notorious-gang-of-8-the-countries-most-responsible-for-the-deaths-of-elephants/ (Accessed 22nd June 2022).

Delpech D., Borrion H., and Johnson S. (2021). Systematic review of situational prevention methods for crime against species. Crime. Sci 10, 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s40163-020-00138-1

Didarali Z., Kuiper T., Brink C. W., Buij R., Virani M. Z., Reson E. O., and Santangeli A. (2022). Awareness of environmental legislation as a deterrent for wildlife crime: A case with Masaai pastoralists, poison use and the Kenya Wildlife Act. Ambio. 51 (7), 1632–1642. doi: 10.1007/s13280-021-01695-8

Earth League International and John Jay College of Criminal Justice (2023). Environmental crime convergence: A new framework for understanding transnational environmental crime. Earth League International, New York. Available from: https://earthleagueinternational.org/environmental-crime-convergence/ (Accessed August 2023).

EIA (2016). Time for action: End the criminality and corruption fuelling wildlife crime. London: Environmental Investigation Agency. https://eia-international.org (Accessed May 21, 2022).

Erentzen C., Schuller R. A., and Clow K. A. (2021). Advocacy and the innocent client: Defence counsel experiences with wrongful convictions and false guilty pleas. Wrongful. Conv. L. Rev. 2, 1. doi: 10.29173/wclawr40

Gastrow P. (2011). *Termites at work: Transnational organized crime and state erosion in Kenya* (New York: International Peace Institute).

Government of Kenya (2013). The Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions Act. Nairobi: National Council for Law Reporting. https://www.kenyalaw.org/ (Accessed May 21, 2022).

Government of Kenya (2014). The Wildlife Conservation and Management Act, No. 47 of 2013. Nairobi: National Council for Law Reporting. Available online at: https://www.kenyalaw.org/ (Accessed May 21, 2022).

Halliday A., Jayanathan S., Kahumbu P., Karani J., and Morrison M. (2022). Process and outcomes of ivory-related trials in Kenya 2016–2019. Pachyderm 63, 55–71. doi: 10.69649/pachyderm.v63i.498

Kahumbu P., Karani J., Halliday A., and WildlifeDirect (2018). Eyes in the courtroom: An analysis of Kenya’s response to wildlife crime (Courtroom Monitoring Report, 2016–2017). WildlifeDirect. Available from: https://wildlifedirect.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Eyes-in-the-Courtroom-2016-2017.pdf (Accessed July 2022).

Huisman W. and Van Erp J. (2013). Opportunities for environmental crime: A test of situational crime prevention theory. Br. J. Criminol. 53, 1178–1200. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azt036

Karanja D. W. (2019). Assessment of the factors that have led to increased poaching activities in Kenya (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya).

Karanja J. M. and Matsui K. (2018). Synergy issues for rhinoceros conservation and protection in Kenya. Int. J. Environ. Sci Dev. 9, 336–340. doi: 10.18178/ijesd.2018.9.11.1125

Kenya L. O. (2013). The constitution of Kenya: 2010 (Chief Registrar of the Judiciary, Nairobi, Kenya), 22–29.

Kioko J., Kiringe J. W., and Seno S. O. (2012). Impacts of livestock grazing on a savanna grassland in Kenya. J. Arid. Land. 4, 29–35. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1227.2012.00029

Kurland J., Pires S. F., McFann S. C., and Moreto W. D. (2017). Wildlife crime: a conceptual integration, literature review, and methodological critique. Crime. Sci 6, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s40163-017-0066-0

Leakey R. and Morell V. (2002). Wildlife wars: My fight to save Africa’s natural treasures (New York: Macmillan).

Lemieux A. M. and Clarke R. V. (2009). The international ban on ivory sales and its effects on elephant poaching in Africa. Br. J. Criminol. 49, 451–471. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azp030

Maina P. M. and Nzengya D. M. (2021). Perceptions of smallholder farmers towards ban on livestock grazing in the Mount Kenya West Protected Forest, Kenya. Journal of African Interdisciplinary Studies 5 (6), 96–114.

Milledge S. (2007). Illegal killing of African rhinos and horn trade 2000–2005: The era of resurgent markets and emerging organized crime. Pachyderm 43, 96–107. doi: 10.69649/pachyderm.v43i.131

Ngetich F. C. (2016). An assessment of the role of prosecution authorities in combating poaching and wildlife trafficking in Kenya (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya).

Nuwer R. (2016). Kenya Sets Ablaze 105 Tons of Ivory (Nairobi, Kenya: National Geographic). Available online at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/160430-Kenya-record-breaking-ivory-burn:~:text=The%20record%2Dsetting%20burn%20is,its%20trade%20should%20be%20banned (Accessed June 24, 2022).

Ogutu J. O., Piepho H. P., Said M. Y., Ojwang G. O., Njino L. W., Kifugo S. C., et al. (2016). Extreme wildlife declines and concurrent increase in livestock numbers in Kenya: What are the causes? PloS One 11, e0163249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163249

Otieno J. (2013). CITES threatens sanctions on ‘Gang of Eight’ over poaching, illegal ivory trade. Available online at: http://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/news/East-Africa-joins-the-infamous-Gang-of-Eight-over-poaching/ (Accessed 9 October 2021).

Peay J. and Player E. (2018). Pleading guilty: Why vulnerability matters. Modern. Law Rev. 81, 929–957. doi: 10.1111/1468-2230.12374

Petrossian G. A. (2012). The decision to engage in illegal fishing: An examination of situational factors in 54 countries. Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University-Graduate School-Newark.

Petrossian G. A. (2015). Preventing illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing: A situational approach. Biol. Conserv. 189, 39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.005

Pires S. F. and Moreto W. D. (2011). Preventing wildlife crimes: Solutions that can overcome the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 17, 101–123.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2016). World Wildlife Crime Report: Trafficking in protected species. Vienna: United Nations. https://www.unodc.org/ (Accessed May 21, 2022).

USAID (2017). Interagency Agreement to support wildlife conservation and combat wildlife crime (Accessed June 21, 2022).

Wasser S. K., Torkelson A., Winters M., Horeaux Y., Tucker S., Otiende M. Y., et al. (2018). Combating transnational organized crime by linking multiple large ivory seizures to the same dealer. Sci Adv. 4, eaat0625. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat0625

Wasser S. K., Wolock C. J., Kuhner M. K., Brown J. E., Morris C., Horwitz R. J., et al. (2022). Elephant genotypes reveal the size and connectivity of transnational ivory traffickers. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 371–382. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01267-6

Waweru F. K. and Oleleboo W. L. (2013). Human-wildlife conflicts: The case of livestock grazing inside Tsavo West National Park, Kenya. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 3 (19), 60–68. Available online at: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/33067646/LEBOO_PUBLICATION-libre.pdf (Accessed April 2022).

Weisburd D., Groff E. R., and Yang S. M. (2012). The criminology of place: Street segments and our understanding of the crime problem. Oxford University Press.

Weru S. (2016). *Wildlife protection and trafficking assessment in Kenya*. TRAFFIC Report. Available online at: http://www.trafficj.org/publication/16_Wildlife_Protection_and_Trafficking_Assessment_Kenya.pdf (Accessed June 14, 2022).

WildlifeDirect (2018). On the Right Path. An examination of wildlife crime courtroom trials in Kenya. Available online at: https://wildlifedirect.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Eyes-in-the-Courtroom-Report-2016-2017.small_.pdf (Accessed July 18, 2022).

WildlifeDirect (2020). Crimes against wildlife and environment: Kenya’s legal response to wildlife, forestry, and fisheries crime. Available online at: https://wildlifedirect.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/WildlifeDirect-4th-Eyes-in-the-Courtroom-Report-2018-2019-1.pdf (Accessed June 14, 2022).

Keywords: wildlife crime, wildlife prosecutions, environmental crimes, endangered species, Kenya

Citation: Riungu J, Sosnowski M and Petrossian GA (2025) Profiling prosecuted wildlife crimes in Kenya. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6:1626061. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1626061

Received: 09 May 2025; Accepted: 08 September 2025;

Published: 16 October 2025.

Edited by:

Paul Scholte, Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zuzammenarbeit GIZ GmbH, Sierra LeoneCopyright © 2025 Riungu, Sosnowski and Petrossian. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jim Riungu, anJpdW5ndUBqamF5LmN1bnkuZWR1

Jim Riungu

Jim Riungu Monique Sosnowski

Monique Sosnowski Gohar A. Petrossian

Gohar A. Petrossian