- 1Department of Public Administration and Economics, Faculty of Management Sciences, Mangosuthu University of Technology, Durban, South Africa

- 2Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa

Introduction: Protected areas (PAs) are central to global biodiversity conservation as they preserve nature, ecosystems, and cultural values. In South Africa, PAs were historically governed through top-down, exclusionary models rooted in colonial legacies that prioritized ecological protection over community rights and knowledge. This approach limited local access, fostered resentment, and increased management challenges such as poaching. Subsequently, conservation discourse has shifted toward participatory governance, community-based natural resource management (CBNRM), and co-management to promote more equitable and sustainable outcomes. This study explores the extent and nature of local community participation in environmental conservation at Addo Elephant National Park in South Africa, using the lens of Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM).

Method: This was a qualitative case study research, which used purposive and convenient sampling techniques to recruit a sample of 34 participants. Interviews, focus groups and field observations were used to collect data from the participants, which was then thematically analysed.

Results: Findings reveal a tripartite model of community engagement: structured involvement through local NGOs, government-led initiatives such as the Extended Public Works Programme, and isolated voluntary actions driven by cultural values.

Discussion: While formal participation programmes provide economic incentives that mobilize participation, individual efforts, particularly among women, reflect a deep-rooted, intrinsic commitment to environmental stewardship. The study concludes that sustainable conservation requires an integrated approach that combines institutional support with recognition of informal, culturally embedded practices.

1 Introduction

Protected areas (PAs) are the cornerstone of the global efforts aimed at halting biodiversity loss and preserving ecological integrity (Starnes et al., 2021). Defined as geographically designated spaces that are recognized, dedicated, and managed through legal or other effective means to ensure the long-term conservation of nature, PAs also safeguard ecosystem services and cultural values critical to human well-being (Zafar et al., 2023). Globally, over 17% of terrestrial and 8% of marine areas are now under protection, reflecting international commitments such as the Convention on Biological Diversity’s (CBD) Aichi Targets and the more recent Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (Jani et al., 2025). Yet, despite these expansions, concerns persist regarding the social justice implications of conservation, particularly in the Global South where protected area management has often marginalized local communities (Rampheri and Dube, 2021).

Across much of the developing world, particularly in Africa, PAs have historically been established through exclusionary models that prioritized ecological preservation over human development (Foyet, 2024). These models, often rooted in colonial-era ideologies, imposed conservation from above, displacing indigenous and local populations, and undermining customary land tenure systems (Gardner and Roy, 2020). In response, a growing body of scholarship and policy advocacy has called for a shift towards more inclusive and participatory approaches to conservation, including community-based natural resource management (CBNRM), co-management, and participatory governance frameworks (Newing et al., 2024; Lees et al., 2021). These paradigms aim to reconcile biodiversity goals with social equity by recognizing local communities as legitimate stakeholders and rights-holders in conservation processes.

At the continental level, Africa presents both opportunities and challenges in advancing participatory conservation. The continent hosts a significant proportion of the world’s biodiversity, much of it within protected areas. However, conservation governance often remains constrained by historical injustices, weak institutional frameworks, and persistent socio-economic inequalities (Fada et al., 2025). While initiatives such as the African Parks Network and the Southern African Development Community’s (SADC) protocols on natural resource management seek to integrate community voices, implementation remains uneven. Many rural communities adjacent to PAs continue to face restricted access to land and resources, limited decision-making power, and insufficient benefit-sharing mechanisms, perpetuating mistrust and undermining conservation legitimacy (Domínguez and Luoma, 2020).

South Africa exemplifies these broader dynamics within a unique historical and policy context. The country’s PA system is deeply entwined with its colonial and apartheid past, where land dispossession and forced removals underpinned much of the conservation estate (Phaka, 2025). In the post-apartheid era, legal and policy frameworks such as the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act No. 57 of 2003 have sought to redress these legacies by promoting stakeholder participation, equitable benefit distribution, and environmental justice (South Africa, 2003). However, persistent tensions between conservation authorities and rural communities, particularly those historically displaced, highlight the complexities of transforming policy into practice (Isaza and Salas, 2024; Rice, 2022).

The Addo Elephant National Park (AENP), located in the Eastern Cape Province, offers a compelling case through which to examine the promises and challenges of participatory conservation in South Africa. Established in 1931 to protect a remnant elephant population, AENP has grown into one of the country’s largest and most ecologically diverse national parks (SANParks, 2022). The park encompasses multiple biomes and land uses and is surrounded by rural communities that continue to experience high levels of poverty, unemployment, and unresolved land claims (Newing et al., 2024). While participatory mechanisms are formally embedded in the park’s management structures, questions remain about their inclusiveness, efficacy, and ability to address entrenched power imbalances (Rutta, 2023).

This paper investigates the extent and nature of community participation in the governance of AENP. It explores how participatory conservation is conceptualized and implemented within the park, the degree to which local communities are able to influence decision-making, and the socio-political factors that enable or constrain meaningful engagement. Through this case study, the paper contributes to broader debates on conservation governance in post-colonial contexts, where issues of justice, equity, and representation remain at the forefront of environmental policy and practice (Heffernan, 2025). The paper is structured as follows: the next section reviews CBNRM framework; this is followed by a description of the study’s methodology. The findings section presents insights drawn from interviews, policy analysis, and field observations. The discussion then reflects on the implications for conservation practice and governance. The conclusion offers recommendations for strengthening community participation in the management of protected areas in South Africa and beyond.

2 Community-based natural resource management framework

This section examines key themes shaping community-based environmental conservation in South Africa, with particular emphasis on their alignment with the theoretical and practical underpinnings of CBNRM. As a decentralized and participatory framework, CBNRM repositions local communities as central actors in natural resource stewardship, directly challenging top-down conservation models that have historically marginalized rural and indigenous populations. It emphasizes equity, empowerment, and the fair distribution of benefits in the governance of protected areas (Jani et al., 2025). The discussion is organized around four interrelated themes:resource appropriation and control, state authority, participatory conservation models, and the core principles of CBNRM, which collectively frame the analysis of AENP as a contested site of governance and evolving community participation.

2.1 Appropriation and control of natural resources: a foundational CBNRM tension

CBNRM has been a prominent feature of the Southern African conservation landscape for the past 25 to 30 years (Cassidy, 2021). At its core, CBNRM asserts that ownership or meaningful control over natural resources must reside, at least in part, with local communities (Heffernan, 2025). Under this model, communities are not peripheral stakeholders but central actors in the utilization, management, and stewardship of natural resources (Ramaano, 2025). Ongoing debates around natural resource appropriation underscore the importance of both distributive and procedural justice, determining who has access, how decisions are made, and who ultimately benefits (Isaza and Salas, 2024). Sibanda (2024) argues that equitable resource use frameworks must integrate ecological sustainability with governance legitimacy, while Zafar et al. (2023) emphasize prioritizing those most dependent on natural resources, in line with CBNRM’s commitment to livelihood security and risk reduction. The effectiveness of CBNRM models is closely tied to the clarity, security, and contextual relevance of tenure arrangements. Meyer (2022) highlights that local socio-cultural dynamics significantly influence participation, and Blackie (2023) adds that conservation is most successful when communities feel a genuine sense of ownership and responsibility toward their environment. These principles are particularly pertinent in the South African context, where historical dispossession and unresolved land claims continue to shape community attitudes and engagement with conservation initiatives.

2.2 Participatory conservation in protected areas: shifting from separation to reconnection

CBNRM stands in direct contrast to traditional conservation models that separate people from nature. Its central aim is to ensure the equitable distribution of costs, benefits, decision-making authority, and management responsibilities (Fada et al., 2025). In theory, this inclusive approach seeks to alleviate poverty while promoting ecological sustainability (Heffernan, 2025). In contrast, top-down paradigms, such as fortress conservation or biodiversity offsetting, often exclude communities from land access and decision-making processes. These exclusionary practices can provoke resistance and undermine long-term conservation outcomes (Newing et al., 2024). CBNRM aligns more closely with the ‘reconnection’ approach, which regards local communities as indispensable conservation partners (Nustad, 2020). It draws upon local ecological knowledge, cultural values, and historical ties to the land (Adeyanju et al., 2021). In South Africa, a legacy of displacement in the name of conservation has bred deep mistrust, particularly in historically marginalized regions such as the Eastern Cape. Within this context, participatory frameworks must go beyond mere inclusion to enable communities to actively shape conservation objectives and practices. This study interrogates how these principles are operationalized around AENP, and whether current approaches reflect genuine community empowerment or tokenistic consultation.

2.3 Models of participatory conservation: community conservation and collaborative management

CBNRM is conceptually grounded in both community conservation and collaborative management, though these models differ significantly in how power and authority are distributed.

2.3.1 Community conservation

Community conservation prioritizes customary governance systems and local ecological knowledge, advocating for resource control to reside primarily with community groups. This approach aligns closely with the CBNRM principle of inclusive, accountable governance. Studies by Jani et al. (2025) and Foyet (2024) show that local communities often manage resources sustainably under customary regimes. However, efforts to formalize these systems face bureaucratic, racial, and institutional barriers, particularly in South Africa, where participation often means compliance rather than co-decision-making (Musavengane and Kloppers, 2020).

2.3.2 Collaborative management

Collaborative management arrangements often reflect a hybrid governance model, where communities co-manage resources with state entities. Although this can improve resource outcomes, power imbalances persist. Government agencies typically retain final authority, and community roles are limited to implementation rather than governance (Rutta, 2023). As Rice (2022) notes, such arrangements may clash with indigenous norms and perpetuate exclusion. In South Africa, CBNRM aims to rectify these disparities through formal guidelines that define rights, benefit-sharing mechanisms, and participatory governance structures.

2.4 The role of the state: from custodian to partner in CBNRM

CBNRM challenges the traditional notion that the state is the sole legitimate steward of natural resources. While many global frameworks assume that state sovereignty is essential for resource protection (Lees et al., 2021), critics argue this model often marginalizes local actors and reinforces inequalities (Zafar et al., 2023). In South Africa, where land and resource rights remain deeply contested, state dominance over conservation areas can result in conflict, exclusion, and socio-economic disparity, particularly in historically dispossessed communities. The shift toward CBNRM in South Africa reflects an attempt to balance state oversight with local autonomy. It demands a redefinition of the state’s role, not as the primary actor, but as a facilitator of community empowerment, capacity-building, and equitable governance (South Africa, 2003). This reorientation is particularly relevant for protected areas such as AENP, where enduring inequalities persist despite formal commitments to inclusion.

2.5 Core principles of CBNRM in South Africa

CBNRMin South Africa is underpinned by four interrelated principles that seek to harmonize biodiversity conservation with socio-economic development (South Africa, 2003). These principles are rooted in the recognition that conservation must deliver tangible, culturally relevant, and lasting benefits to the communities who live closest to and often bear the greatest costs for protecting natural resources.

2.5.1 Livelihood security and risk reduction

CBNRM initiatives must actively support diverse and context-specific livelihoods, ensuring that conservation efforts do not exacerbate poverty or vulnerability, particularly among marginalized rural populations. In South Africa, where rural communities frequently face high levels of unemployment, food insecurity, and land degradation, conservation strategies must be designed to enhance household resilience to both economic shocks and environmental stressors such as drought, soil erosion, and climate variability (Meyer, 2022). For example, integrating conservation with sustainable agriculture, eco-tourism, and small-scale enterprises can provide alternative income streams while promoting environmental stewardship. Livelihood security in this context also requires reducing risks associated with land tenure insecurity, limited access to markets, and political marginalization (Khan and Sultana, 2020). Thus, CBNRM calls for policies that are responsive to local socio-economic realities and adaptable to changing conditions.

2.5.2 Resource enhancement for long-term benefit

Sustainability is a core aim of CBNRM, which emphasizes the stewardship of natural capital including land, water, forests, and biodiversity, as a foundation for long-term community development (Heffernan, 2025). Conservation initiatives must therefore go beyond protection to promote active enhancement of ecosystems through restoration, controlled harvesting, and traditional resource management practices (Foyet, 2024). To achieve this, clear and enforceable rules must govern the allocation of use rights, prevent over-exploitation, and ensure that future generations benefit from conserved resources. These rules must be developed through participatory processes, reflecting local knowledge systems and ensuring legitimacy among stakeholders. In the South African context, where land restitution claims and unresolved tenure disputes persist, secure resource access is essential for incentivizing conservation and avoiding conflict (Adeyanju et al., 2021).

2.5.3 Inclusive and accountable governance

CBNRM requires governance systems that are inclusive, transparent, and responsive to the needs and aspirations of all stakeholders, especially historically marginalized groups (Ramaano, 2025). Effective governance involves shared decision-making power between state agencies, local authorities, NGOs, and community-based organizations, with mechanisms in place for accountability and recourse. In South Africa, this means confronting structural inequalities that limit participation, such as bureaucratic complexity, limited education, and the legacy of apartheid land dispossession (Jani et al., 2025). Recognizing customary leadership and local governance institutions is vital, but safeguards must also be in place to prevent elite capture and ensure that youth, women, and other vulnerable groups are genuinely represented (Fada et al., 2025; Newing et al., 2024). Strengthening local capacity for governance through training, institutional support, and equitable access to information, is a critical enabler of sustainable and democratic conservation.

2.5.4 Tangible and equitable returns

Participation in conservation must result in visible, meaningful, and fairly distributed benefits for the communities involved (Foyet, 2024). These benefits may take multiple forms, including employment opportunities, income from tourism or natural resource use, improved infrastructure, spiritual and cultural enrichment, and strengthened social cohesion (Cassidy, 2021). In the absence of such returns, communities may become disillusioned, disengaged, or even resistant to conservation efforts, especially where they perceive that the state or private actors reap disproportionate rewards (Heffernan, 2025). Equitable benefit-sharing mechanisms must therefore be institutionalised, with clear criteria for how revenues and opportunities are distributed among different community members (Sibanda, 2024). Furthermore, benefits should not be purely economic; CBNRM also values non-material rewards such as the restoration of cultural ties to ancestral land and increased recognition of indigenous knowledge systems (Newing et al., 2024). In summary, CBNRM provides a normative and practical framework for restructuring conservation around principles of justice, empowerment, and ecological stewardship. By applying this lens toAENP, this study seeks to understand whether and how the park’s governance practices embody or fall short of CBNRM ideals.

3 Research methodology

This study is grounded in an interpretivist epistemology, which views reality as socially constructed and best understood through individuals’ lived experiences and local knowledge. This approach aligns with the CBNRM framework by emphasizing community perceptions, power dynamics, and participatory environmental governance. A qualitative case study design was used to explore the nature and extent of community participation in conservation efforts around AENP. This design allowed for an in-depth, context-sensitive investigation of the complex relationships between local communities, state institutions, and conservation authorities. The case study approach was chosen because of its strength in illuminating nuanced social processes, particularly where the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly defined (Yin, 2014). AENP represents a site of evolving governance, shaped by competing historical, political, and ecological forces, making it ideal for a grounded, exploratory study.

3.1 Research site

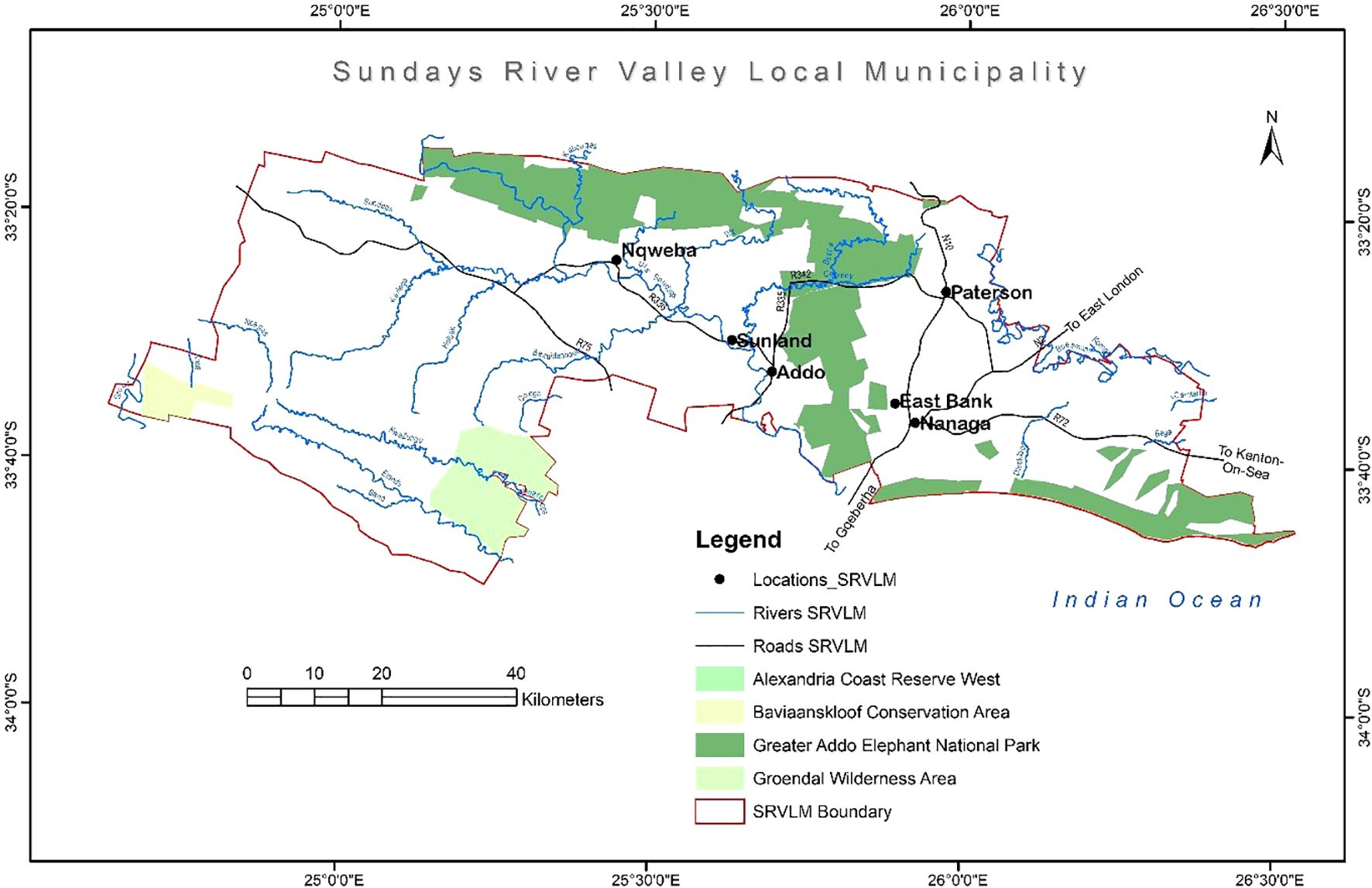

This study was conducted in and around AENP, situated in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. AENP is one of the country’s largest and most ecologically diverse protected areas and serves as a flagship conservation site under the management of South African National Parks (SANParks). Its historical expansion has been accompanied by the displacement of local communities, unresolved land restitution claims, and persistent tensions between conservation priorities and local development needs (Giddy and Rogerson, 2023). Research activities were carried out both within the park and in four adjacent communities, Sunland, East Bank, Paterson, and Nanaga, which were purposefully selected due to their geographic proximity and socio-economic interdependence with AENP. These settlements are marked by high levels of poverty, unemployment, and underdevelopment, yet they also exhibit strong social cohesion, active customary leadership structures, and historical connections to the land now under conservation (Mlungu and Kwizera, 2020). The choice of AENP as a case study is grounded in its complex socio-political context and its relevance to the principles of CBNRM. The park’s contested governance landscape and proximity to marginalized communities make it a critical site for examining how CBNRM is operationalized in practice, and whether it promotes meaningful community participation, equitable benefit-sharing, and sustainable conservation outcomes. Figure 1 below is a basic location map that depicts AENP and the surrounding communities where the research was conducted.

Figure 1. Basic map of the addo elephant national park and the surrounding communities where the research was conducted.

3.2 Sampling strategy

A combination of non-probability sampling techniques was used to recruit participants. Convenient sampling was applied to select participants from the AENPand surrounding communities, focusing on individuals who were readily accessible and willing to participate. To gain insights from stakeholders with specific knowledge and institutional roles, purposive sampling was employed to identify and recruit key informants from relevant government departments, AENP management, the local municipality, and the traditional leadership structures. A total of 34 participants comprised the study sample. This included 4 government officials from the Department of Tourism, Environmental Affairs and Economic Development; the Department of Public Works and Infrastructure; the Department of Rural Development and Agrarian Reform; and the AENP. Additionally, 26 community members were drawn from the four settlements surrounding the park, along with 2 local traditional leaders and 2 ward councillors representing adjacent communities. This sampling approach ensured the inclusion of a diverse range of perspectives, from institutional decision-makers to grassroots community members.

3.3 Data collection

Multiple qualitative data collection techniques were employed to enhance the richness and credibility of the findings. Semi-structured interviews were used with government and park officials to explore policy frameworks, institutional practices, and perceptions of community engagement. On the other hand, unstructured interviews were held with traditional leaders and ward councillors to facilitate open-ended discussions on local governance, land rights, and conservation-related challenges. In addition, focus group discussions were conducted with community members to capture their collective experiences, attitudes, and levels of involvement in conservation activities. Non-participant observation was also conducted within the park and surroundings community spaces, which provided contextual understanding of community-park interactions and the socio-spatial dynamics of conservation. The triangulation of these methods allowed the researcher to validate findings across different data sources and to gain a more holistic understanding of the research problem.

3.4 Data analysis

All qualitative data collected through interviews, focus groups, and observation were subjected to thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke’s (2023) six-step approach: familiarization, coding, theme development, review, definition, and reporting. Transcripts were read multiple times to identify patterns, contradictions, and recurring themes related to participation, governance, benefits, and challenges under the CBNRM framework. Themes were then interpreted through the lens of CBNRM principles, with attention to how local understandings of natural capital, governance, and social dynamics influence conservation outcomes. NVivo software was used to organize data and support transparency in coding.

4 Research findings

This study aimed to explore the nature of local participation in environmental conservation aroundAENP. Three main themes emerged from the data analysis.

4.1 Participation through CBNRM

The findings indicate that the participatory conservation approach implemented in AENP aligns with the principles of CBNRM. This form of participation is characterised by administrative functions being primarily managed by local Non Governmental Organisations (NGOs) affiliated with the park and other nearby conservation institutions. The study reveals that local communities are central to conservation efforts, while NGOs play a supporting role by overseeing administrative responsibilities. The following quotations support these conclusions:

“…. we participate in environmental management as a community and we do this together with Wild Foundation as the prominent one as well as other hotels, lodges and B&Bs that support this cause (Community member 1).

The evidence confirms that participatory conservation around AENP follows a CBNRM model. Community respondents consistently described long-standing, locally organised conservation practices:

“…. there are various community conservation practices [CBNRM] that are available in all the local communities around the national park. These have been in existence since I was born. They were even there before the democratic government was formed” (Community member 7).

Focus-group participants added that “practically every family” is involved directly or indirectly in these initiatives. Traditional leaders echoed this view, emphasising their role in guiding and coordinating community efforts:

“As traditional leaders, we are mandated to guide our people on environmental management. Our community-based groups propose ideas, clearing trails, managing vegetation, organising clean-ups, and we collaborate with nearby companies and hotels to advance the conservation agenda.” (Traditional authority 1)

A second traditional authority highlighted the influence of tourism businesses:

“The hotels in this area know what needs to be done to keep the environment attractive to tourists. They meet with local people and teach them how to protect it.” (Traditional authority 2)

Park management likewise acknowledged CBNRM as official policy:

“Local people and organisations are authorised to manage the environment around the park just as we do. We encourage them to partner with private organisations. Fortunately, a buffer zone separates the park from settlements, so even if local efforts falter, the park’s core remains protected.” (Park Manager)

The evidence confirms that environmental governance around AENP fits the model of CBNRM. Although management is formally shared between local residents and park authorities, decision-making is largely driven by institutional actors, especially NGOs, tourism enterprises, and government agencies, leaving communities with limited influence over conservation priorities. This dynamic accords with the broader literature on collaborative resource governance. Genuine or perceived ownership motivates community stewardship (Blackie, 2023), and people invest more effort when they believe they hold tangible control rights (Jani et al., 2025). Yet the state retains ultimate authority over natural resources, shaping what activities can occur (Adeyanju et al., 2021). Consequently, management practices around AENP skew toward institutional rather than community objectives, a pattern also observed by Musavengane and Kloppers (2020).

4.2 Participation through government programmes

Participatory conservation around AENP is significantly shaped by state-sponsored programmes, most notably the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP). Originally established to address structural unemployment, the EPWP has evolved into a critical mechanism for advancing both environmental protection and community development, thereby aligning with key principles of CBNRM in South Africa. Local governance structures play a pivotal role in facilitating EPWP enrolment. As one ward councillor emphasized:

“As a ward councillor … I oversee participation through the EPWP. This two-in-one initiative reduces unemployment and enhances environmental conservation.” (Ward Councillor 1)

Another ward councillor elaborated on the program’s strategic implementation, noting the emergence of collaborative proposals between communities and local NGOs, which often outline specific conservation-related tasks:

“The EPWP has sparked real interest. We’ve groomed local leaders who now work with NGOs to identify the best ways to conserve the environment for tourism.” (Ward Councillor 2)

These remarks highlight the EPWP’s role as an entry point for community leadership development and conservation awareness, consistent with CBNRM’s emphasis on local empowerment, capacity building, and inclusive stewardship in natural resource governance. From a policy perspective, provincial government officials echoed the programme’s importance. A representative from the Department of Tourism, Environmental Affairs and Economic Development explained how the department supports Sector Education and Training Authority (SETA) -accredited environmental training, directly linking education to employability within conservation sectors:

“… our department believes that humankind starts with conservation of the environment. As a result, we have various service providers that are contracted by the Department … to induct people into different unit standard courses under the Sector Education and Training Authorities (SETAs). These are mainly in line with community environmental conservation. They give local people knowledge, and those who participate through the courses have high chances of being employed through EPWP.” (Government Official 1)

Additionally, the Department of Rural Development and Agrarian Reform plays a complementary role by allocating discretionary grants through NGOs, allowing rural communities to conceptualize and implement their own environmental management projects. According to one official:

“… the surrounding rural communities to AENP participate in environmental management through the grants that we provide to them through the NGOs and service providers around them … These individuals and organisations support themselves through environmental conservation, and many have made significant contributions.” (Government Official 2)

These accounts collectively underscore how government programmes incentivize and professionalize community-based conservation, delivering dual dividends. These include tangible environmental benefits, such as biodiversity protection and ecological restoration; as well as livelihood security, through job creation, capacity development, and expanded access to financial capital. This dual mandate is consistent with global trends, where governments have played a pivotal role in establishing and supporting protected areas (Isaza and Salas, 2024), often by fostering multi-stakeholder conservation partnerships (Ramaano, 2025; Heffernan, 2025). In the South African context, the EPWP and related support mechanisms directly reflect CBNRM principles. For example, principle 2 promotes environmental stewardship for present and future generations, echoed in the training and employment of youth in conservation activities, whilst principle 5 emphasizes the need for effective policies and laws implemented by legitimate local organisations, a role increasingly played by community-based NGOs funded through state channels. Thus, the EPWP and associated programmes around AENP are not merely stop-gap employment measures; they constitute a decentralized model of conservation governance grounded in the values of inclusion, empowerment, and sustainability that lie at the heart of CBNRM.

4.3 Isolated individual participation

The study also found that local communities engage in isolated, individual efforts toward environmental conservation. These actions are voluntary and occur independently of any formal management organisation or coordinated institutional framework. In this regard, the focus group revealed that:

“…. women have a connectedness to the natural environment whether paid or voluntary. In our communities, there are a lot of women who are involved in environmental conservation. One of the people even has a garden where she grows flowers and trees. That is done absolutely without any payment.” (Community member 4).

Participants engaged in environmental management primarily out of a personal appreciation and affection for the natural environment. As one focus group participant remarked:

“…. this area is beautiful and is the only place in Southern Africa which has hundreds of elephants. I just thank God for having this beauty of nature and it is my responsibility as a local community member to sustain it. I try by every means to maintain natural vegetation; I clear trails and I also clean run-off water drains so that we don’t experience floods when it rains” (Community member 9).

The findings revealed that the management of AENP actively supported individual participation in environmental protection and played a key role in facilitating these efforts. Conservation initiatives typically originate within the park and gradually extend to surrounding communities through targeted information-sharing and outreach activities. In this regard, the Park Manager noted:

“…. All the conservational efforts that you see being done by the local communities are a brainchild of the national parks programme. We started with these empowerment programmes where we empowered local communities to help preserve the environment. We then opened our floors to invite other organisations to help us do this. At the end, this has become a culture in the communities around the national park, and for that we are very grateful” (Parks Manager).

These observations were corroborated by an official from the Department of Tourism, Environmental Affairs, and Economic Development, who stated:

“…. we have various principles of CBNRM which encourage local community members to participate in environmental management. We understand that people may not have the same feelings and knowledge about conserving the areas around the national parks, but we appreciate the efforts of those who do it without being influenced by any organisation” (Government official 1).

Concurring, traditional authorities characterized individual environmental conservation as a socio-cultural practice, rooted in social constructionism and embedded in communal values and norms.

“…. the duty of us as traditional authorities is to make sure that we create harmony among people as they undergo different processes in environmental conservation. We work together with the local community members and the organisations around us” (Traditional authority 1).

Traditional authorities believed that the notion of environmental conservation is passed down from generation to generation through socialisation. They maintain that environmental protection has existed even before the establishment of the AENP. Overall, the findings indicate that individual participation may be self-motivated or influenced by various external forces. These findings align with the existing literature. Fada et al. (2025) and Ramaano (2025) emphasize that clear ownership of natural resources fosters accountability and assigns responsibilities to resource holders. In the case of the AENP area, this recognition of ownership encouraged local communities to take responsibility for their customary tenure systems and actively participate in environmental conservation efforts. Regarding the involvement of external stakeholders, such as national parks and government agencies, Phaka (2025) argues that institutional interventions are essential. They enable local communities to benefit from principles of social justice by promoting equality, ethical resource distribution, and, most importantly, fairness (Meyer, 2022). Furthermore, the management of natural resources is viewed as a cultural responsibility shared by all community members (Cassidy, 2021). This notion is reinforced by Principle 7 of CBNRM, which underscores the importance of strong local leadership, particularly the role of traditional authorities, in cultivating and sustaining an ethic of conservation at the individual level.

5 Discussion

The study found that participatory conservation practices around AENP exemplify the principles of CBNRM, where local communities play a pivotal role in environmental stewardship. These practices are operationalised through a range of formal and informal mechanisms, reflecting both institutional engagement and grassroots agency. While communities are positioned as central actors in conservation, the coordination and implementation of initiatives are largely driven by local NGOs and conservation agencies affiliated with the park. These institutions facilitate training, provide resources, and offer technical support, thereby playing an enabling role in community participation.

One of the most significant government-supported mechanisms for participation identified in the study is the EPWP. The EPWP offers temporary employment opportunities in environmental management tasks, such as alien vegetation removal, erosion control, and park maintenance. By linking conservation work with income generation, the programme serves as a practical response to the socio-economic needs of the surrounding communities. Interviews with government officials and community members revealed that monetary compensation remains the dominant incentive driving local participation in conservation. This finding suggests that, while conservation may not always stem from intrinsic environmental values, it is nonetheless effectively mobilised through economic interventions. This aligns with broader critiques of incentive-based conservation models, which argue that sustainability is more achievable when livelihood security and environmental goals are simultaneously addressed (Heffernan, 2025; Jani et al., 2025).

Beyond institutional programmes, the research also uncovered a less formal but equally significant layer of environmental engagement: isolated, voluntary participation by individuals. This form of participation, while not embedded within any structured management system, reflects deep-seated cultural and ethical values related to land, nature, and community well-being. Focus group discussions, particularly those conducted with women, revealed that many community members engage in environmental practices such as preventing illegal dumping, planting indigenous trees, and protecting water sources, not because they are paid to do so, but because they view it as a personal or communal responsibility. These actions, though less visible in official reports, are crucial for fostering a broader culture of conservation and should be recognised and supported in future policy planning.

Together, these findings demonstrate that participatory conservation around AENP is multifaceted. On one hand, it is shaped by formal structures that provide resources and incentives; on the other, it is sustained by informal, culturally rooted practices that reveal a longstanding relationship between people and their environment. Importantly, the coexistence of these pathways suggests that effective conservation strategies should not only focus on institutional frameworks but also nurture local values and voluntary action. Strengthening the linkages between formal and informal participation, through capacity-building, inclusive governance, and recognition of traditional knowledge, could enhance the long-term sustainability of conservation efforts in the region.

6 Conclusion

This study has highlighted the multifaceted nature of participatory conservation practices among communities surrounding AENP, demonstrating how environmental stewardship is shaped by both institutional mechanisms and grassroots agency. By examining the principles and application of CBNRM, the research reveals that conservation is not a singular, top-down process, but rather a dynamic interplay between structured programmes and informal community action. Institutional actors, particularly local NGOs and the government through the EPWP, have played a critical role in enabling and incentivizing conservation participation. These formal structures provide communities with essential resources, skills, and employment opportunities, linking environmental objectives with socio-economic benefits. However, the study also found that economic incentives, while effective in mobilizing participation, often overshadow deeper environmental consciousness, indicating the need for balanced strategies that address both livelihood and ecological imperatives.

Equally important are the voluntary, culturally motivated conservation efforts undertaken by individuals within these communities. These actions, though often unrecognized in formal conservation frameworks, reflect a deep-rooted ethic of care for the environment. Particularly among women, voluntary efforts to protect local ecosystems illustrate a form of environmental engagement that is both personal and communal, rooted in tradition, social norms, and everyday experience. In sum, the study concludes that successful participatory conservation in contexts like AENP depends on the integration of formal, incentive-based programmes with the recognition and support of informal, culturally embedded practices. To enhance the long-term sustainability of conservation initiatives, policymakers and practitioners must foster inclusive approaches that build community capacity, acknowledge traditional ecological knowledge, and create enabling environments for both structured and autonomous forms of participation. Only by embracing this dual approach can conservation efforts be truly participatory, equitable, and resilient.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Fort Hare Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ZG: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. NH: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adeyanju S., O’connora A., Addoahb T., Bayalac E., Djoudid H., Moombee K., et al. (2021). Learning from community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) in Ghana and Zambia: lessons for integrated landscape approaches. Int. For. Rev. 23, 273–297. doi: 10.1505/146554821833992776

Blackie I. R. (2023). “Community-based natural resources management and poverty reduction,” in Handbook on Tourism and Conservation. Eds. Mbaiwa J. E., Kolawole O. D., Hambira W. L., and Mogende E. (Northampton: Elgaronline), 237–248. doi: 10.4337/9781839106071.00025

Braun V. and Clarke V. (2023). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int. J. Transgender Health 24, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

Cassidy L. (2021). Power dynamics and new directions in the recent evolution of CBNRM in Botswana. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 3, 1–8. doi: 10.1111/csp2.205

Domínguez L. and Luoma C. (2020). Decolonising conservation policy: how colonial land and conservation ideologies persist and perpetuate indigenous injustices at the expense of the environment. Land 9 (65), 1–22. doi: 10.3390/land9030065

Fada S. J., Omotoriogun T. C., Owusu E. H., Danmallam B. A., Alhassan A. R., and Akintunde E. A. (2025). Hippo conservation in West Africa: conflicts, co-existence and rural communities’ Empowerment. Afr. J. Geographical Sci. 6, 89–94. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.15700286

Foyet M. (2024). Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) in southern Africa: history, principles, evolution and contemporary challenges. Namibian J. Environ. 9, 1–15. Available online at: https://nje.org.na/index.php/nje/article/view/volume9-foyet.

Gardner L. and Roy T. (2020). “Colonialism and the environment,” in The Economic History of Colonialism (Bristol University Press, Bristol, UK). doi: 10.51952/9781529207651.ch008

Giddy J. K. and Rogerson J. M. (2023). Linking state-owned nature-based tourism assets for local small enterprise development in South Africa. Studia Periegetica 3, 107–127. doi: 10.58683/sp.597

Heffernan A. (2025). A call for wildlife conservation policy evolution: climate change and community-based natural resource management. Climate Dev. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2025.2491540

Isaza A. S. and Salas P. P. (2024). Community perception on the development of rural community-based tourism amid social tensions: A Colombian case. Community Dev. 55, 123–137. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2023.2204441

Jani V., Webb N. L., and de Wit (2025). “Natural resources-based conflicts in rural Zimbabwe,” in Contestations over Natural Resources in the Mid-Zambezi Vallley. Eds. Matanzima J., Chandambuka P., and Helliker K. (Routledge, New York).

Khan N. A. and Sultana N. (2020). Natural resource management: an approach to poverty reduction. Springer Nat. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69625-6_111-1

Lees C. M., Rutschmann A., Santure A. W., and Beggs J. R. (2021). Science-based, stakeholder-inclusive and participatory conservation planning helps reverse the decline of threatened species. Biol. Conserv. 260, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109194

Meyer M. (2022). Conservation and livelihood impact of community-based natural resource management in Namibia’s Zambezi Region, doctoral thesis (Germany: Bonn University).

Mlungu F. and Kwizera A. S. (2020). Assessment of the socio-economic impacts of Tourism on three rural communities neighbouring Addo Elephant National Park, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Afr. J. Hospitality Tourism Leisure 9(1), 1–19.

Musavengane R. and Kloppers R. (2020). Social capital: An investment towards community resilience in the collaborative natural resources management of community-based tourism schemes. Tourism Manage. Perspect. 34, 100654. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100654

Newing H., Brittain S., BuChadas A., del Giorgio O., Grasham C. F., Ferritto R., et al. (2024). ‘Participatory’ conservation research involving indigenous peoples and local communities: Fourteen principles for good practice. Biol. Conserv. 296, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110708

Nustad K. G. (2020). Notes on the political ecology of time: Temporal aspects of nature and conservation in a South African World Heritage Site. Geoforum 111, 94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.03.002

Phaka F. M. (2025). Wildlife in vernacular as a means for an inclusive environmental sector and community engagement in South Africa. Environ. Commun. 19, 74–86. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2024.2395889

Ramaano A. I. (2025). Toward tourism-oriented community-based natural resource management for sustainability and climate change mitigation leadership in rural municipalities. J. Humanities Appl. Soc. Sci. 7, 107–131. doi: 10.1108/JHASS-07-2024-0099

Rampheri M. B. and Dube T. (2021). Local community involvement in nature conservation under the auspices of Community-Based Natural Resource Management: A state-of-the-art review. Afr. J. Ecol. 59, 799–808. doi: 10.1111/aje.12801

Rice W. S. (2022). Exploring common dialectical tensions constraining collaborative communication required for post-2020 conservation. J. Environ. Manage. 316, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115187

Rutta E. W. (2023). Rural women vulnerability to human-wildlife conflicts: Lessons from villages near Mikumi National Park, Southeast Tanzania. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 15. doi: 10.5897/IJBC2023.1582

SANParks (2022). Addo Elephant National Park Management Plan 2022–2032 (Pretoria: South African National Parks).

Sibanda N. (2024) in Eco-Social Contracting for Environmental Justice: Assessing the Effectiveness of Community-Based Natural Resource Management, A paper prepared for the UNRISD Global Policy Seminar for a New Eco-Social Contract, Bonn, Germany, 29–30 August 2023.

South Africa (2003). National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act, No. 57 of 2003 (Pretoria: Government Gazette).

Starnes T., Beresford A. E., Buchanan G. M., Lewis M., Hughes A., and Gregor R. D. (2021). The extent and effectiveness of protected areas in the UK. Global Ecol. Conserv. 30, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01745

Keywords: environmental conservation, community participation, community-based natural resource management, collaborative management, participatory conservation, protected areas, inclusive and accountable governance

Citation: Gotyi ZG and Handi N (2025) Exploring community participation in environmental conservation: insights from Addo Elephant National Park in South Africa. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6:1646126. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1646126

Received: 12 June 2025; Accepted: 28 July 2025;

Published: 15 August 2025.

Edited by:

David Jennings, Defenders of Wildlife, United StatesReviewed by:

Tanyaradzwa Mundoga, Kingsway Campus, South AfricaJephias Mapuva, Midlands State University, Zimbabwe

Copyright © 2025 Gotyi and Handi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zamikhaya Gladwell Gotyi, Z290eWkuemFtaWtoYXlhQG11dC5hYy56YQ==

Zamikhaya Gladwell Gotyi

Zamikhaya Gladwell Gotyi Nontle Handi2

Nontle Handi2