- 1Conservation Science, Centre for Wildlife Studies, Bengaluru, India

- 2Nicholas School of Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States

- 3School of Forest, Fisheries, and Geomatics Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, United States

Biodiversity hotspots are areas of exceptional ecological value and they often coincide with high human population densities. These biodiverse areas may experience high levels of human-wildlife conflict, threatening both wildlife and local communities. While environmental education (EE) offers a promising tool for mitigating conflict, the ecological, cultural, and political diversity across hotspots poses significant challenges for designing and adapting effective EE interventions. To test whether an EE program could scale across the Western Ghats, a biodiversity hotspot in India, we developed and implemented the Wild Shaale program in government schools across three states: Goa, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu from June 2022 to February 2023. Our objective was to assess whether the program had a consistent impact across states or if regional differences influenced learning outcomes. Here, we report on data from 7381 students from 200 schools around 11 wildlife reserves with equal participation from boys and girls across the three states. We found that participation in the Wild Shaale program led to significant increases in environmental knowledge and knowledge of safety behaviors in all three states, as well as small positive shifts in most measures of environmental attitudes. We also found that there are significant differences in baseline attitudes towards wildlife and baseline levels of environmental knowledge across states. Students in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu had a more positive baseline attitude towards wildlife in general compared to Goa and students in Tamil Nadu had the lowest pre-test scores on environmental knowledge questions. Despite small regional differences, we found that Wild Shaale emerges as a scalable education program that is effective across diverse cultural, political and ecological contexts. We show that a single, adaptable EE program can be effectively scaled across diverse socio-ecological contexts.

1 Introduction

Biodiversity hotspots are regions of the world that have exceptionally high levels of biodiversity and face significant threats from human activity, such as habitat loss (Monastersky, 2014; Murali et al., 2021; Trew and Maclean, 2021). With the increasing intersection of human populations and wildlife in these hotspots, the issue of human-wildlife conflict arises, which threatens wildlife survival as well as human livelihoods (Joppa et al., 2010; Karanth and Kudalkar, 2017; Karanth and Vanamamalai, 2020).

Environmental education (EE) initiatives in biodiversity hotspots can help reduce or de-escalate conflicts by increasing adults’ and children’s awareness of environmental issues, enhancing positive attitudes toward wildlife, and providing information on safe ways to coexist with wildlife (Espinosa and Jacobson, 2012; Salazar et al., 2024, 2022). However, many biodiversity hotspots span vast geographical areas, often crossing political boundaries and encompassing diverse cultural groups (Gorenflo et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2020). This geographic, ecological and sociocultural diversity creates a fundamental challenge to EE: how can programs designed for specific local contexts be scaled effectively across such heterogeneous landscapes? A program that is impactful in one community may fail to resonate in another if it does not reflect local customs, values, or governance structures. To create effective EE programs in these areas, it is important to consider how local cultures, customs, and practices shape environmental attitudes and behaviors. In addition to ecological variation, education programs and curricula may need to be adapted to reflect the unique social and political context of different areas within a biodiversity hotspot (Joppa et al., 2010; Manfredo, 2008). Scalability or the ability to deliver consistent conservation messages while remaining responsive to local diversity, remains a critical, unresolved question. Understanding how to overcome this barrier is central to advancing EE in biodiversity hotspots.

India is home to four globally recognized biodiversity hotspots, the Himalayas, the Indo-Burma region, the Western Ghats and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The Western Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is known for its rich biodiversity. The region, covering 140,000 km2 in a 1600 km long stretch is also considered as one of the eight ‘hottest hotspots’ of global biodiversity and harbors about 121 species of mammals including populations of globally threatened ‘landscape’ species such as the Asian elephant, gaur and tiger (Penjor et al., 2024; UNESCO World Heritage Centre, n.d). Endemic and endangered species such as the lion-tailed macaque, Nilgiri tahr and Nilgiri langur are unique to this region (Myers et al., 2000; UNESCO World Heritage Centre, n.d). However, this region also harbors the highest human population density across all eight hottest hotspots (Cincotta et al., 2000) resulting in high levels of human-wildlife conflicts reported across the Western Ghats, especially along the borders of wildlife reserves (Karanth et al., 2012; Karanth and Vanamamalai, 2020; Ramesh et al., 2022).

The Western Ghats runs across six states of India: Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Each of these states is unique and differs in terms of size, population, language, culture, religious beliefs, and traditions. Relationships with animals also vary across this region. For example, Goa’s wildlife is concentrated in smaller sanctuaries such as Bhagwan Mahavir Wildlife Sanctuary and Mollem National Park. Goa’s major focus is on its marine ecosystem and hence terrestrial wildlife conservation receives less attention compared to the other states (Biodiversity in Goa, n.d; IUCN, 2016; Usmani and Ansari, 2020; WWF-India, 2016). In Goa, rapid urbanization and tourism-related pressures have led to habitat fragmentation, which also impacts wildlife conservation efforts. In the case of Karnataka, about 45% of its land areas lie within the Western Ghats making it one of the most biodiverse states in India. Karnataka also has a rich cultural history tied to its forests, with indigenous communities such as the Halakki Vakkaligas and Gowlis having unique practices enabling wildlife conservation (Balasubramanian and Sangha, 2023; Nayak, 2017; Roy et al., 2015). Tamil Nadu encompasses parts of the Nilgiri Hills within the Western Ghats. The state has a long-standing tradition of worshipping animals like elephants as sacred beings (Kalpana, 2024). Indigenous communities such as the Todas in the Nilgiri Hills also have unique cultural practices tied to wildlife preservation (Magimairaj and Balamurugan, 2017; Nair et al., 2022).

Our aim with the Wild Shaale program was to create an EE program that could be implemented in government schools across the Western Ghats. However, given the diverse cultural, linguistic, and ecological landscapes within the region, we also wanted to assess whether the program would be uniformly effective across these varying contexts. To achieve this, we developed a comprehensive EE program specifically tailored for students aged 10-13 (Salazar et al., 2024, 2022). The program incorporated regionally relevant ecological concepts and conservation themes, ensuring the content was both engaging and relevant to the Western Ghats. From 2022-2023, we implemented and evaluated the program across three states: Tamil Nadu, Goa, and Karnataka. Wild Shaale offers a particularly valuable model for exploring scalability because it was explicitly designed to be delivered across highly diverse socio-cultural and ecological contexts within a single biodiversity hotspot. The program combines a standardized curriculum focused on human–wildlife coexistence with flexible, locally relevant examples, language adaptations, and community-specific content. This hybrid structure makes Wild Shaale uniquely suited to test how environmental education programs can retain their effectiveness while scaling across regions that differ in culture, governance, and human-wildlife dynamics.

Our primary objective was to assess whether the program had a consistent impact across states or if regional differences influenced program outcomes. This evaluation enabled us to refine the program, ensuring its adaptability and effectiveness in fostering environmental awareness among young learners across the Western Ghats.

2 Methods

2.1 Program

The Wild Shaale program was launched in 2018 in Karnataka (Salazar et al., 2024, 2022). The goal was to design an EE program that could be led by an Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) within the formal school system, and scaled regionally across the Western Ghats. The program, implemented by the Centre for Wildlife Studies (CWS), was then developed and improved across three phases. After each phase, evaluation data and feedback from staff and students were used to improve the curriculum and evaluation tools, and to increase the program’s ability to expand while retaining quality (Salazar et al., 2024, 2022). In the academic year 2022-2023, the program entered its fourth phase, incorporating changes based on feedback from earlier phases. This phase also marked the expansion of the program into the states of Goa and Tamil Nadu, which are also part of the Western Ghats. In this phase, the program included four modules, each approximately 3 hours long. The modules were Our Wildlife, Our Environment, Living with Wildlife and Future of Wildlife and covered the following themes: wildlife, ecosystems, resources, conflict mitigation, and conservation. The program design was informed by the experiential learning model (ELM) (Kolb, 1984), transformative learning theory, and research on empathy building. Each module includes a mix of games, outdoor activities, art-based activities, and multimedia presentations that help students engage with the module’s theme and make connections to previous modules. Drawing on the ELM, educators lead students in hands-on experiences, encourage them to reflect on those experiences, help them connect their experiences to the real-world, and ask them to apply what they have learned in new situations (Kolb, 1984). Some games and activities also encourage students to take the perspective of wildlife, which can help build empathy (Young et al., 2018).

From its inception in 2018 till present, Wild Shaale has reached over 64,000 students across 1400 schools (Centre for Wildlife Studies, 2025).

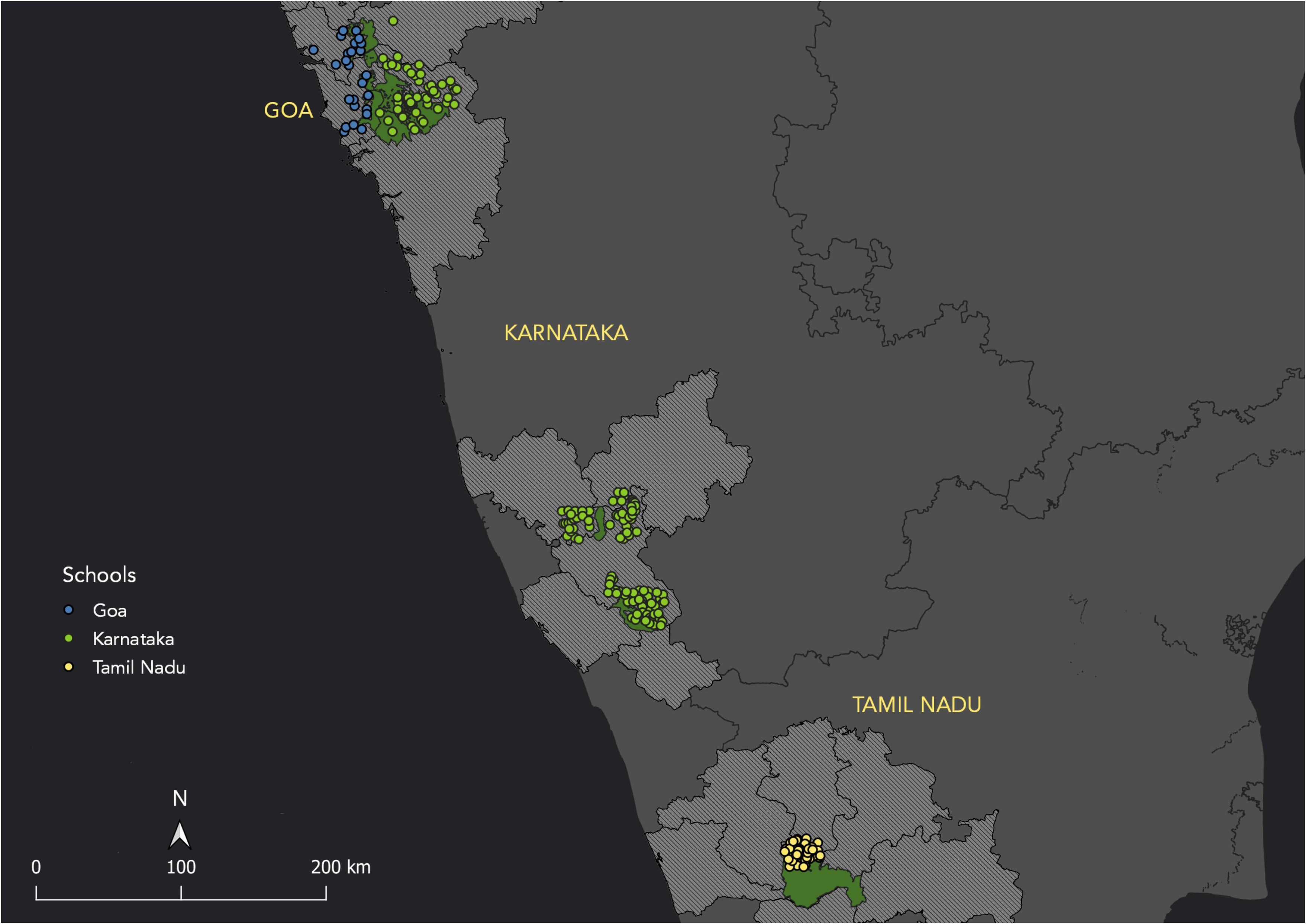

2.2 Study area

The study focused on schools located within a 20-kilometer buffer from the boundaries of 11 wildlife reserves across three states, Goa, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, that together represent a large portion of the Western Ghats biodiversity hotspot. Karnataka has the highest number of wildlife protected areas among these states. It has 5 National Parks, 36 Wildlife Sanctuaries, at least 18 Conservation Reserves and 1 community reserve (Karnataka Forest Department, 2025). A total of 7762 students from 201 schools participated in the study, although we only report data from 95.1% students who participated in both pre- and post- tests (n = 7381) schools = 200. In Karnataka, the study was carried out in 125 schools around Pushpagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Kali Wildlife Sanctuary and Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary. These reserves include a mix of high-elevation evergreen forests, riverine ecosystems, and forest-agriculture mosaics with significant human use (Bawa et al., 2007; Behera et al., 2025; Ramachandra et al., 2018). In Goa, the study was conducted in 25 schools around the six protected areas of Cotigao, Netravali, Bondla, Bhagwan Mahaveer, Mhadei and Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary, smaller but ecologically rich reserves where forest patches are closely interwoven with villages and agricultural lands (Kale et al., 2016; Ramachandra and Shivamurthy, 2023; Rege et al., 2020). In Tamil Nadu, the study focused on 51 schools around the Anamalai Wildlife Sanctuary, a landscape of tropical rainforest and plantations where elephants and large carnivores frequently interact with human settlements (Kumar et al., 2010; Sidhu et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2024).

These 11 reserves encompass a range of ecological conditions, from the moist deciduous and semi-evergreen forests of the central and southern Western Ghats to drier forest types and agroforests-dominated landscapes. They are home to diverse fauna including large carnivores such as tigers (Panthera tigris), leopards (Panthera pardus), wild dogs (Cuon alpinus), and sloth bears (Melursus ursinus) and herbivores such as elephants (Elephas maximus), gaur (Bos gaurus) and chital (Axis axis), and several endemic and threatened species. The human population in this region is equally varied and ranges from approximately 1.59 million in Goa to over 72 million in Tamil Nadu, with communities depending on agriculture, forest produce, and livestock for their livelihoods. Human-wildlife interactions, including crop damage, livestock loss, and occasional carnivore encounters, are common in many of these areas (Karanth et al., 2012; Karanth and Vanamamalai, 2020; Ramesh et al., 2022).

Minor modifications were made to the Wild Shaale curriculum to tailor the curriculum to reflect context-specific habitats, species, and conservation challenges in the three states. For example, one game that featured elephants in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka was adapted to feature a gaur in Goa because there are no elephants in Goa. This allowed for the structure to be consistent while ensuring that the species and ecosystems are locally relevant. This research was conducted in the states of Goa, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu from June 2022 to February 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map indicating the schools where Wild Shaale modules were conducted in Goa, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

2.3 Assessing program effectiveness

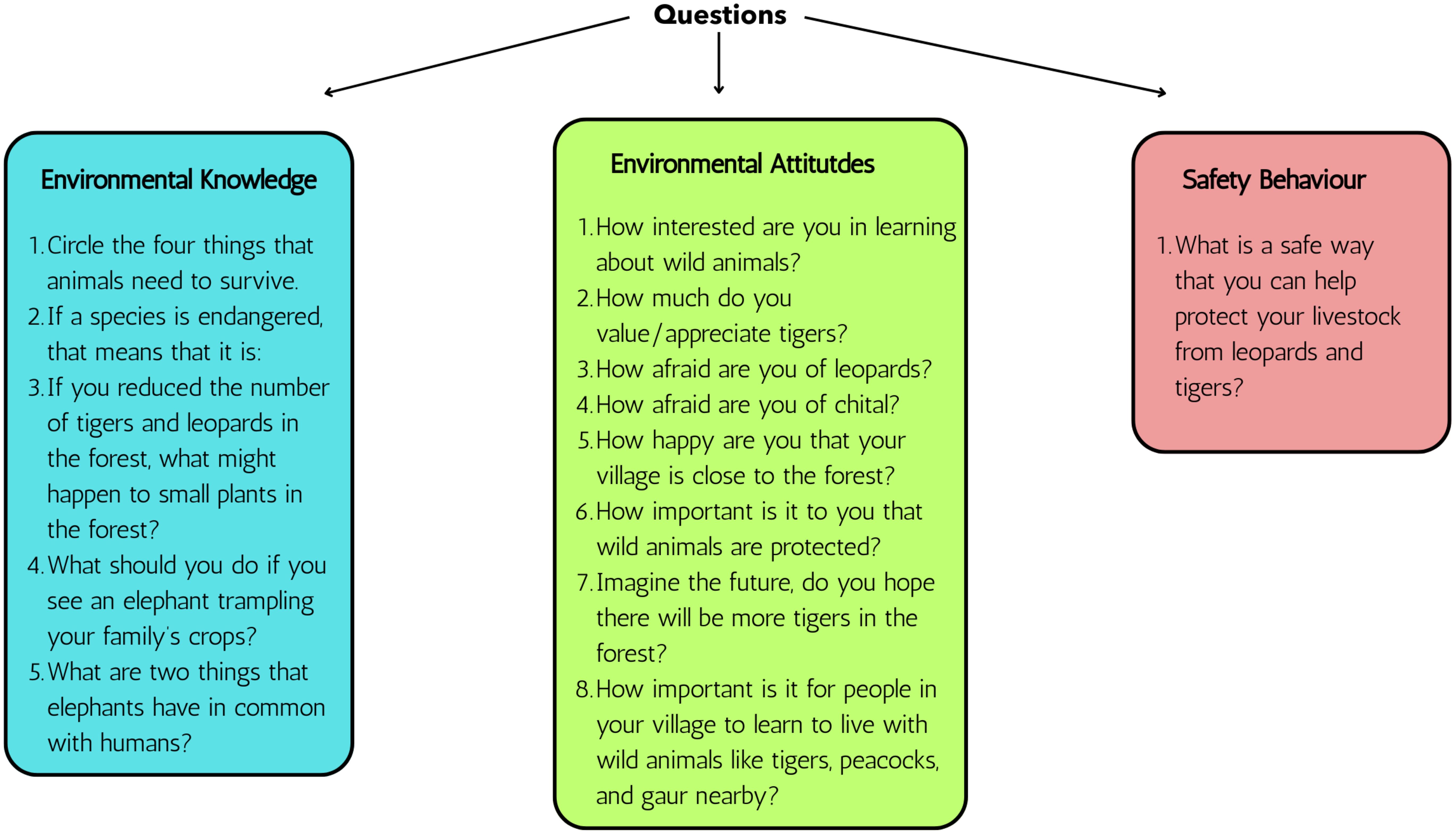

In this study, we focused on whether participation in the Wild Shaale program had a consistent impact across states. To do this, we examined whether regional differences influenced learning outcomes, including environmental literacy, knowledge of safe behaviors around wildlife, and positive attitudes toward wildlife and the environment (Figure 2). We used a survey instrument (Supporting Information S1) that was administered in the form of a written test at the beginning of the program (Week 1) and at the end of the program (Week 4). Five questions were used to assess environmental knowledge and 1 question was used to assess knowledge of safety behaviors (Figure 2). The five knowledge questions and 1 safety question are tied to different aspects of the program curriculum to test knowledge gained through the program. The eight attitude questions were selected to assess different aspects of students’ attitudes toward wildlife (e.g., interest in wildlife, value of wildlife, importance of coexistence). These questions are tied to themes covered throughout the program and were already pilot tested in a previous study (Salazar et al., 2024) in the states of Karnataka and Maharashtra. The scale was not tested using Chronbach’s alpha because it tests different aspects of children’s attitudes toward wildlife. Based on our previous pilot testing, we knew that children were unlikely to respond consistently to these questions (e.g., they could be very interested in wildlife, but not want to live near a forest). We suspect that these inconsistencies could be due to the variety of their experiences with Human Wildlife Conflict and their complex relationships with wildlife. Because of this, we report the results of each question individually. The survey was translated into three different languages, Konkani for Goa, Kannada for Karnataka and Tamil for Tamil Nadu; it was then back-translated by different staff into English to ensure accuracy (Brislin, 1970). In the classroom, all evaluation tools were read aloud by the educators to increase student comprehension (Musser and Malkus, 1994). Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Centre for Wildlife Studies, Bengaluru, India; approval number: CWS_IRB_2020_002.

Figure 2. The list of questions asked to evaluate the different aspects of children’s knowledge and attitudes towards wildlife and ecosystems. The question asking about fear of chital (spotted deer) was included to check whether students were reading the questions carefully; we anticipated that they would be less afraid of chital than leopards.

2.4 Statistical analysis

We assessed changes in attitude after the Shaale module by performing ordinal logistic regression of attitudes with Likert scale answers (Salazar, 2022) as response variables and pre-and post- sessions as predictor variables for each state. We also measured the baseline attitudes of students of each state, where we performed additional ordinal logistic regression analysis, with Likert scale answers as response variables and state as predictor variables. For the environmental knowledge questions (5 questions), we built a logistic regression model. The response variable was binary, with whether the student gave a correct answer or not and the state and session (pre or post) were predictor variables, including an interaction term between the two. In this manner, we evaluated the difference in responses across states as well as whether the teaching of Wild Shaale module improved student scores. For the open-ended question on safety of livestock, we analyzed the student responses for correct phrases used, and as in the environmental knowledge questions, built a logistic regression model, with binary response variable, with state and session as predictor variables, including interaction term. We then built a logistic regression model with response variable as correct or incorrect response and state and the session as predictor variables, as well as the interaction term. All analyses were done in the R studio (RStudio Team, 2016). The regressions were done using the MASS package (Venables and Ripley, 2002) and ordinal package (Christensen, 2024), followed by pairwise analysis using the Emmeans package (Lenth et al., 2025) in R studio. The plots were visualized using the ggplot package (Wickham, 2016) in R.

3 Results

We report on data from 7381 students across the three states, with 1511 from Goa (20.4%), 3766 from Karnataka (51%) and 2104 from Tamil Nadu (28.4%). The students were between the ages of 10–13 and ranged from 5th to 7th grade. We covered 25 schools in Goa, 124 schools in Karnataka and 51 in Tamil Nadu. There was equal participation of boys and girls in all three states (Girls = 49.9% in Goa, 51.1% in Karnataka and 48.9% in Tamil Nadu).

Participation in the Wild Shaale program led to measurable improvements across all domains (e.g., environmental attitudes, knowledge, and safety behaviors) in all three states. At the same time, variation in baseline knowledge and attitudes and in the magnitude of gains highlights that while the program’s core content is broadly effective, its impact is also shaped by local contexts. These findings show that the Wild Shaale program is scalable across diverse settings and emphasize the need for context-specific refinements to maximize its effectiveness.

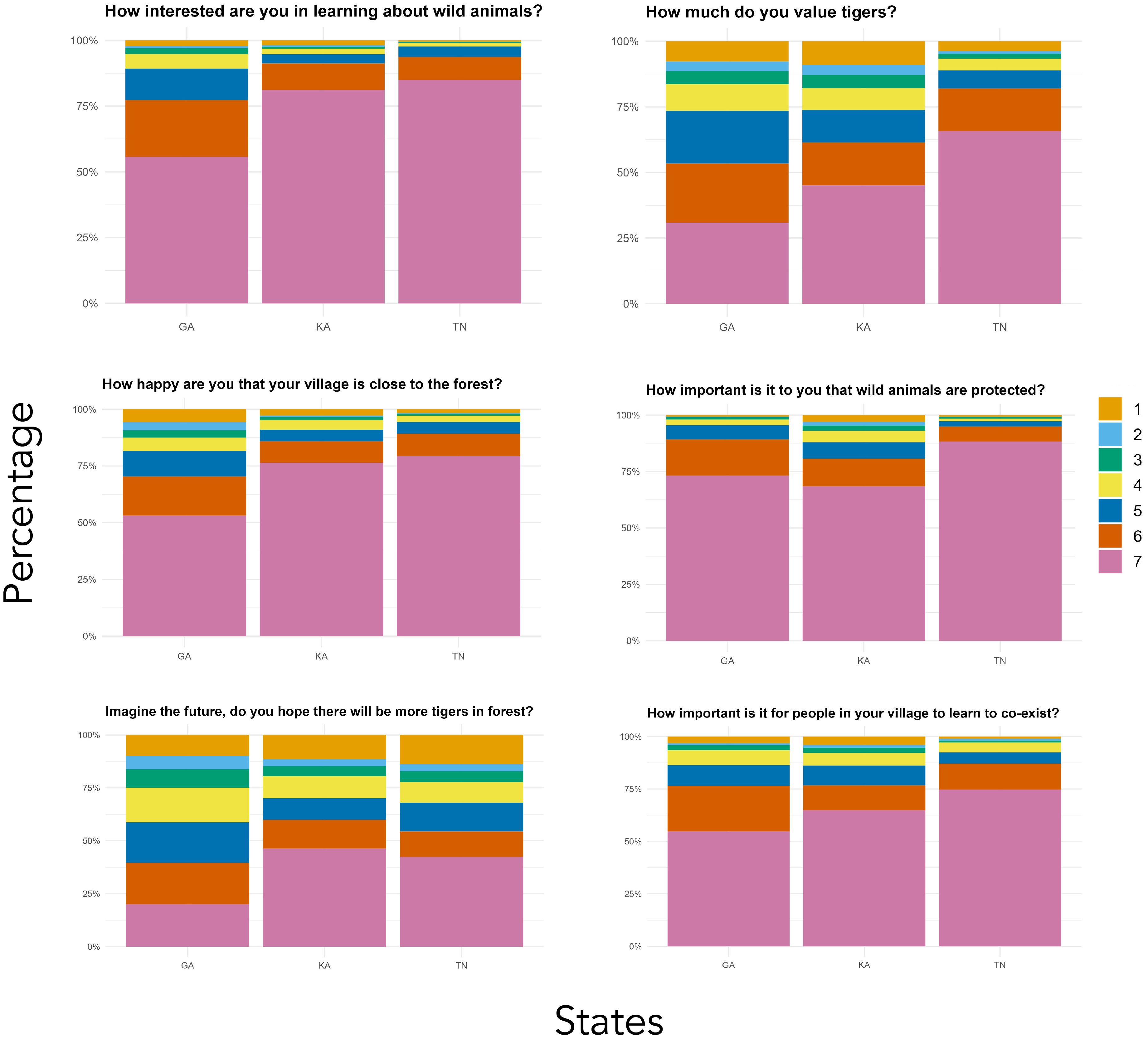

3.1 Environmental attitude analysis

To assess environmental attitudes, eight questions were provided to the students where they had to respond with a 7-point scale ranging from not at all to very much, indicated by circles of increasing size. Across states, almost all measures of children’s attitudes toward wildlife shifted in a positive direction after participation in the Wild Shaale modules. In Goa, responses to all eight attitude questions shifted significantly in a positive direction, with the strongest shift in responses to three questions: “How much do you value tigers?”, “Do you hope there will be more tigers in the future?” and “Would you be interested in learning more about wild animals?” (Supplementary Table S2). Interestingly, for Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, there was a small negative shift in response to the question “How happy are you that your village is close to the forest?” (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). In Tamil Nadu for the post session, there was also a small negative shift in response to this question “How important is it to you that wild animals are protected?” compared to the pre-session (Supplementary Table S4). It is important to note that all the differences between pre and post sessions, although statistically significant, have limited practical significance because the effect sizes were very small (Supplementary Tables S2, S3, S4).

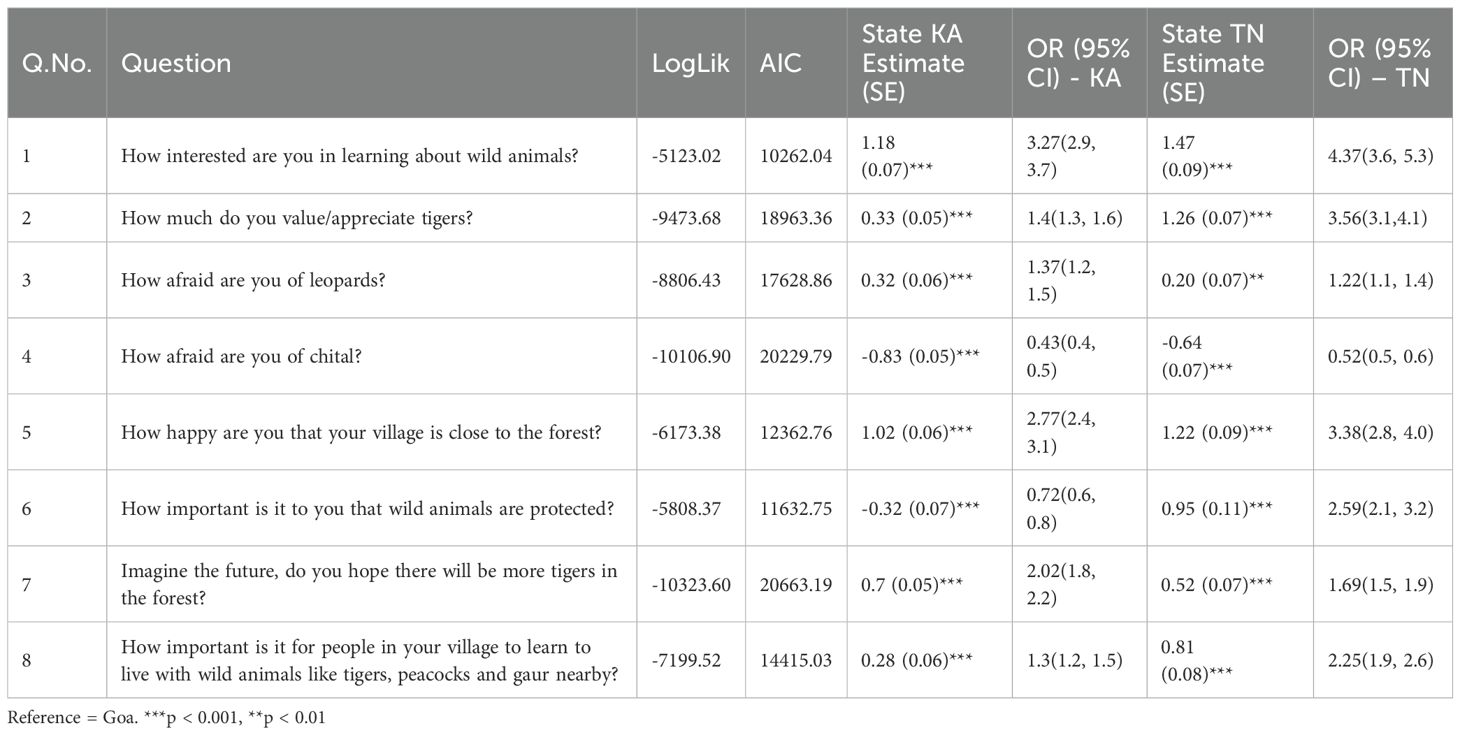

In addition to analyzing how attitudes shifted from pre- to post-, we examined baseline attitudes that children have towards wildlife and how this varies across states. To do this, we performed an ordinal logistic regression analysis with the Likert scale answer as the response variable and state as the predictor variable. This was followed by a pairwise comparison to understand the differences between all three states.

Overall, we found that Karnataka and Tamil Nadu seemed to have a more positive baseline attitude towards wildlife in general compared to Goa (Figure 3; Table 1; Supplementary Table S1). This was more pronounced in questions such as “How interested are you in learning about wild animals”, “How happy are you that your village is close to the forest?”, “How much do you value/appreciate tigers?” and “Imagine the future, do you hope there will be more tigers in the forest?”. For example, for the question, “How interested are you in learning about wild animals”, more than 75% students responded with 7 (most positive response) on the Likert scale in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, whereas only about 55% students responded with 7 in Goa. Similarly for the question, “How much do you value tigers?”, only about 25% students from Goa responded with 7 on Likert scale while this was about 45% for Karnataka and 65% for Tamil Nadu. These findings align with the regression coefficients, which showed significantly higher odds of more positive responses in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu compared to Goa (Table 1; Supplementary Table S1). Students in Tamil Nadu had exceptionally positive responses to two questions with about 80% students responding with 7 for the question, “How interested are you in learning about wild animals” and about 65% students responding with a very positive 7 for the question “How much do you value tigers?”, where students from Karnataka also had only 45% respond with 7 (Figure 3; Tables 1, S1).

Figure 3. The responses of students to 6 attitude-based questions, where the students responded to the question on a 7-point likert scale from 1-7, with 1 being not all to 7 being very much. The responses are shown for each state, Goa (GA), Karnataka (KA) and Tamil Nadu (TN) in the pre-survey session.

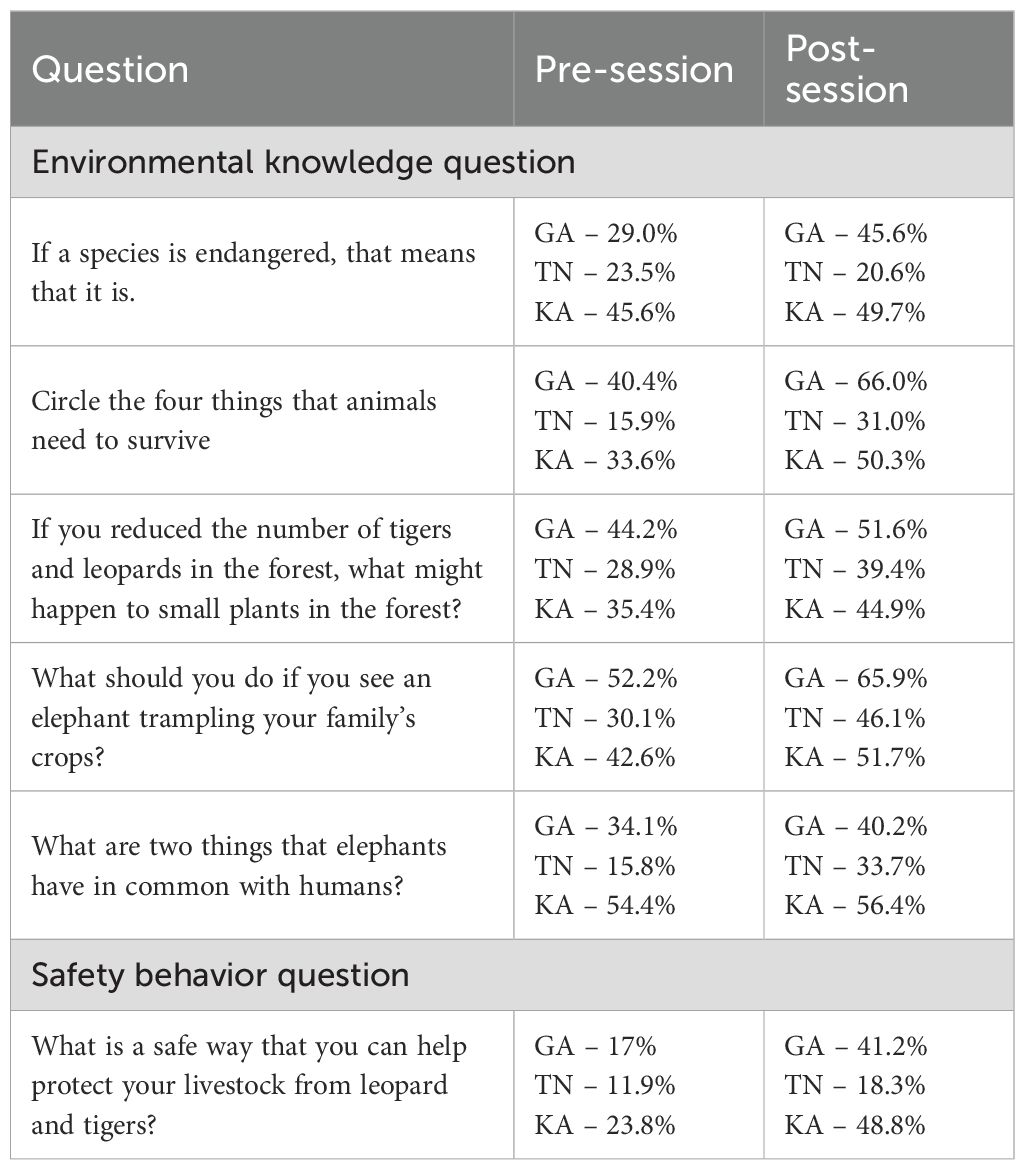

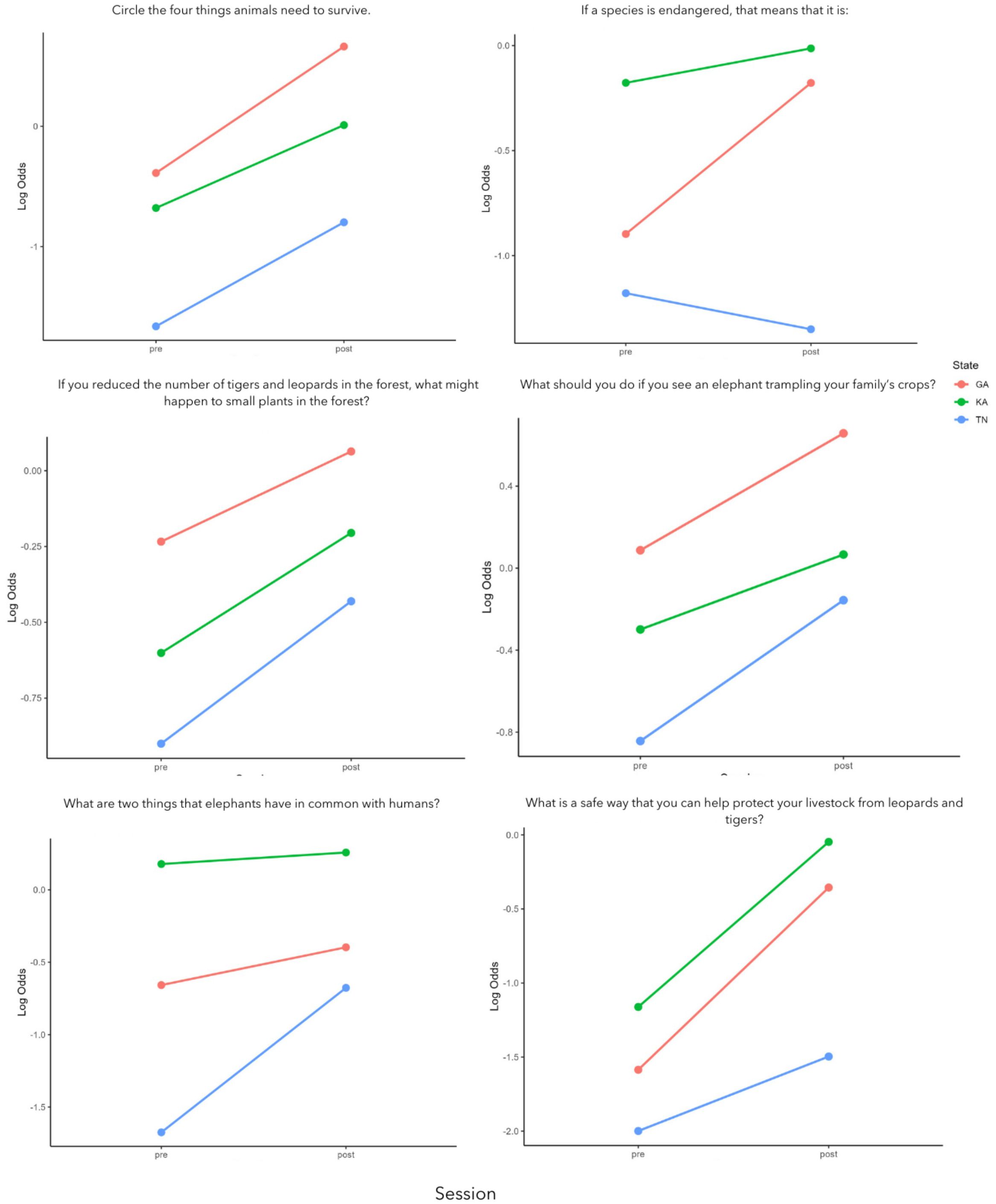

3.2 Environmental knowledge question analysis

We analyzed the basic understanding students have about ecological concepts by asking five knowledge-based multiple-choice questions. In general, there were significantly more correct responses on the post-test than the pre-test across questions and states, indicating that the Wild Shaale modules were effective in teaching children about ecological and environmental concepts (Figure 4; Tables 2; Supplementary Table S5). To demonstrate this, we have reported simple percentages of correct answers from pre- to post- (Table 2) and as well as the odds ratio or the odds of a correct response being given post-session compared to pre-session (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S5). To understand differences in baseline knowledge across states, we also compared the odds of a correct response being given in the pre-session between states (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 4. Pairwise comparisons of predicted probabilities (expressed as odds ratios) across states and sessions. For Question, “Circle the four things that animals need to survive.”, within-state comparisons between post and pre revealed significant increases in all three states: GA (OR = 2.86, p < 0.0001), KA (OR = 1.99, p < 0.0001), and TN (OR = 2.38, p < 0.0001). In the pre-session, GA participants had higher odds than TN (OR = 3.58, p < 0.0001) and KA (OR = 1.34, p = 0.0001). KA also had higher pre-session odds than TN (OR = 2.68, p < 0.0001). For Question, “If a species is endangered, that means that it is:”, within-state pre–post comparisons showed a significant increase in GA (OR = 2.05, p < 0.0001) and KA (OR = 1.18, p = 0.0051), but not in TN (OR = 0.84, p = 0.1923). Pre-session, KA had higher odds than TN (OR = 2.72, p < 0.0001) and GA (OR = 0.49, p < 0.0001); GA also had higher odds than TN (OR = 1.33, p = 0.0031). For Question, “If you reduced the number of tigers and leopards in the forest, what might happen to small plants in the forest?”, within-state comparisons between post and pre revealed significant increases in all three states: GA (OR = 1.35, p = 0.0007), KA (OR = 1.49, p < 0.0001), and TN (OR = 1.6, p < 0.0001). In the pre-session, GA participants had higher odds than TN (OR = 1.95, p < 0.0001) and KA (OR = 1.44, p = 0.0001). KA also had higher pre-session odds than TN (OR = 1.35, p < 0.0001). For the Question: “What should you do if you see an elephant trampling your family’s crops?”, within-state pre–post comparisons showed a significant increase in GA (OR = 1.77, p < 0.0001), KA (OR = 1.44, p < 0.0001) and TN (OR = 1.99, p < 0.0001). Pre-session, GA had higher odds than TN (OR = 2.54, p < 0.0001) and KA (OR = 1.47, p < 0.0001); KA also had higher odds than TN (OR = 1.71, p < 0.0001). For the Question: “What are two things that elephants have in common with humans?”, within-state comparisons between post and pre revealed significant increases in all three states: GA (OR = 1.3, p = 0.007), and TN (OR = 2.71, p < 0.0001) but not KA (OR = 1.1, p =0.52). In the pre-session, KA participants had higher odds than TN (OR = 6.38, p < 0.0001) and GA (OR = 0.43, p < 0.0001). GA also had higher pre-session odds than TN (OR = 2.77, p < 0.0001). For the Question: “What would be a safe way to protect the livestock against tigers and leopards?”, within-state pre–post comparisons showed a significant increase in GA (OR = 3.42, p < 0.0001), KA (OR = 3.05, p < 0.0001), and TN (OR = 1.65, p < 0.0001). Pre-session, KA had higher odds than TN (OR = 2.31, p < 0.0001) and GA (OR = 0.65, p < 0.0001); GA also had higher odds than TN (OR = 1.51, p = 0.0002).

The only instance where there was not an increase in knowledge from pre- to post- was in Tamil Nadu for the question “If a species is endangered, that means that it is.” In this instance, students responded with the least number of correct responses in the pre session (23.5%), which surprisingly decreased even further for the post session (20.6%), but this was not a significant change (OR = 0.84, p = 0.1923). In contrast, the logistic regression analysis showed that post sessions had more correct responses for Goa and Karnataka (Figure 4).

When it came to the question “Circle the four things that animals need to survive?”, we observed students in Goa had the most correct answers (pre session - 40.4%, post session - 66%). Tamil Nadu students had the least correct responses in pre session (15.9%) which increased significantly in the post session (31%) (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S5).

Students in Goa were most likely to correctly answer the question “If you reduced the number of tigers and leopards in the forest, what might happen to small plants in the forest?”, (pre session - 44.2%, post session - 51.6%). While Tamil Nadu students had the least number of correct responses in pre session (28.9%), this increased in the post session (39.4%) (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S5).

With respect to the question “What should you do if you see an elephant trampling your family’s crops?” students in Goa had the highest number of correct responses (pre session - 52.2%, post session - 65.9%). Tamil Nadu had the least number of correct responses in pre session (30.1%), which did show an increase in the post session (46.1%) (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S5).

For the question “What are two things that elephants have in common with humans?”, Karnataka had the most correct responses from students (pre session - 54.4%, post session - 56.4%). Students responded with least correct responses for pre-session in Tamil Nadu (15.8%), however, they improved significantly in the post session (33.7%) (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S5).

Taken together, these results show that while all states demonstrated learning gains, the magnitude of improvement varied according to baseline levels. Goa students consistently performed best on knowledge questions, whereas Tamil Nadu students started with the lowest scores but made notable relative gains after the intervention.

3.3 Safety behavior analysis

Students were asked open ended questions on what would be a safe way to protect the livestock from tigers and leopards. Their responses were analyzed to find correct phrases and each student was given 1 (for a correct response) or 0 (for an incorrect response). Following this a logistic regression analysis was done where whether they gave a correct response or not (binary variable) was the response variable and the state and session (pre or post) were predictor variables.

As expected, we found that the students tended to give more correct responses in the post session compared to the pre session across all states (GA (OR = 3.42, p < 0.0001), KA (OR = 3.05, p < 0.0001), and TN (OR = 1.65, p < 0.0001) (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S5). The states were different from each other in the number of correct responses in the pre-session, with Karnataka having the greatest number of correct responses in pre-session (23.8%), followed by Goa (17%) and then Tamil Nadu (11.9%). The correct responses increased significantly in the post session for all three states, Karnataka (48.8%), Goa (41.2%) and Tamil Nadu (18.3%), although the increase was the least pronounced for Tamil Nadu (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S5).

These differences suggest that while the program successfully improved safety knowledge across all states, regional variation in baseline understanding influenced the extent of post-program gains. Karnataka students, who began with stronger safety knowledge, also showed the highest overall gains, whereas Tamil Nadu students, starting from the lowest baseline, made smaller absolute gains.

3.4 Interest in environmental topics

When asked what topic they would like to learn more about, the most popular answer among students in Goa and Tamil Nadu was Tigers (27.3% in Goa and 50% in Tamil Nadu). In Karnataka, the most popular answer was Elephants (15%).

4 Discussion

We found that participating in the Wild Shaale program resulted in a significant increase in students’ environmental literacy and knowledge of safe behaviors across Goa, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. Changes in attitudes, while less pronounced, also showed similar trends across the three states. This indicates that it is possible to scale an environmental education program across a culturally and geographically biodiverse hotspot with small adaptations to local contexts. However, while the overall trends were similar, there were notable differences between states, such as finding that students in Tamil Nadu had the lowest pre-test scores on environmental knowledge questions, compared to the other states. We also found significant differences in students’ baseline attitudes toward wildlife across the different states. Students in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu reported more positive baseline attitudes towards wildlife than students in Goa, although baseline attitudes were generally positive across all three states. We did not find a major shift in attitudes toward wildlife after students participated in the Wild Shaale program. This might be due to their highly positive baseline attitudes, which left little room for growth, or to the fact that environmental attitudes may be relatively stable and therefore more difficult to influence through short interventions (Gifford and Sussman, 2012; Kaiser et al., 2014).

One of the most positive outcomes of the Wild Shaale program was the consistent and statistically significant improvement in students’ environmental knowledge and knowledge of safe behaviors around wildlife from pre- to post-. It is notable that for environmental knowledge questions, students from Tamil Nadu provided fewer correct answers in the pre-test compared to those from the other two states. This is particularly interesting given the higher positive attitude towards wildlife that Tamil Nadu students demonstrated. A positive attitude toward wildlife does not always correlate with accurate knowledge about wildlife. Studies have shown that attitudes often emerge through informal interactions with animals or cultural practices, whereas accurate knowledge requires structured learning (Castillo-Huitrón et al., 2024; Liordos et al., 2017; Young et al., 2018). In Tamil Nadu, students may exhibit strong emotional connections to wildlife but lack detailed factual understanding. Several factors may explain this result, one of which could be educational gaps in localized wildlife knowledge.

While environmental education is compulsory in India in the formal education system, a review found that there is variability between states as to how EE is infused in textbooks and that there is still little active learning in natural environments (Sharma and Menonn, n.d). When our Wild Shaale educators reviewed textbooks across the states they work in, they also found that environmental topics tended to be broad - focusing on issues such as climate change and pollution - rather than local wildlife knowledge. Similar studies have revealed that limited emphasis on wildlife education in school curricula can result in lower baseline knowledge among students. Research in Malaysia showed that younger students had significantly less wildlife knowledge due to gaps in their syllabus, which only introduced biodiversity topics at later stages of education (Arumugam et al., 2019). A study of rural children’s knowledge and attitudes toward wildlife in the nearby state of Kerala found that children had limited recognition of local mammal species, apart from species that are regularly publicized by the media (Binoy et al., 2021). Their knowledge of conservation issues facing these species was also low.

The small shift in attitudes from pre- to post- may be partly due to a ‘ceiling effect’ where baseline scores leave little room for growth (Ernst and Theimer, 2011). We found a similar ceiling effect in our previous evaluation of the Wild Shaale program (Salazar et al., 2024). In Goa, where baseline attitudes were slightly less positive than in other states, there were small but significant positive shifts in attitudes in response to questions such as “How much do you value tigers?”, “Do you hope there will be more tigers in the future?” and “Would you be interested in learning more about wild animals?”. However, the effect sizes of these differences were very small. It would be interesting to test whether a longer program with more immersive time in nature or hands-on experiences with wildlife would result in a larger positive shift in attitudes. Dosage, which includes the duration and intensity of a program, can influence program outcomes (Wheaton et al., 2018). While the relationship between dosage and environmental attitudes is complicated, some studies suggest that longer programs and direct experiences in the outdoors are correlated with more positive increases in environmental attitudes (Dettmann-Easler and Pease, 1999; Rickinson, 2001). A study conducted at the Ohio Wildlife Centre showed that children’s attitudes and willingness to co-exist with local species improved significantly after participating in animal encounter programs and that these effects persisted over time (Jerger et al., 2022).

Some of the differences we found across states from pre- to post- could be due in part to the differences between educators. Each state had a different team of educators implementing the program. While all educators participated in the same training and were supposed to implement a standardized curriculum, differences in program delivery, facilitator emphasis and teaching style may have influenced our results. Future studies could explore whether there is an educator effect on program outcomes. Notably, for one knowledge-based question, students in Tamil Nadu had fewer correct responses in the post-session compared to the pre-session. This unexpected result could reflect differences in how the concept was conveyed and understood, variation in facilitator emphasis, or even differences in student attention during those sessions.

In addition, our evaluation captures only immediate, short-term changes measured shortly after the program’s completion. This limits our ability to assess whether changes in knowledge and attitudes persist over time or translate into behavioral outcomes. Future research should incorporate long-term follow-up assessments and, where possible, behavioral measures to better understand the lasting impacts and real-world relevance of environmental education programs like Wild Shaale.

In the future, it would also be interesting to explore whether children who participate in the Wild Shaale program pass on knowledge to their parents or to other members of their families and communities. For instance, children who participated in similar initiatives were found to influence their families and communities by promoting coexistence practices (Jerger et al., 2022; Liu and Green, 2024). A study conducted in the Republic of Seychelles showed that the environmental knowledge of parents was positively influenced by their children’s participation in wetland-based education through local wildlife clubs (Damerell et al., 2013). Similarly, a study in Australia showed that EE programs led to children discussing environmental issues at home and thereby influenced the knowledge and behavior of their parents (Ballantyne et al., 2001). In a Costa Rican village, students and their parents showed significant gains in knowledge after the students participated in a one-month environmental education program about scarlet macaw conservation; interestingly, they also transmitted course information to their neighbors (Vaughan et al., 2003). Future research on the Wild Shaale program could explore whether there are long-term changes in attitudes among participants and whether the program results in intergenerational knowledge transfer.

Although there were significant differences in baseline attitudes toward wildlife between states, it is promising that baseline attitudes were highly positive overall. This could be due to cultural and religious values related to wildlife. For example, many communities in these states revere animals like elephants and tigers as symbols of divinity or cultural heritage, which may positively influence children’s baseline attitudes towards wildlife (Bist et al., 2002; Nair et al., 2020; Sharma and Kumar, 2021). Many communities in the Western Ghats also have a long history of living alongside wildlife. Adults in a community near two protected areas in Tamil Nadu had largely positive attitudes toward wildlife conservation, despite experiencing high levels of human-wildlife conflict (Karanth and Ranganathan, 2018). In areas like this, where attitudes toward wildlife are already very positive, it may be more important for programs like Wild Shaale to focus on environmental literacy and knowledge of safe behaviors around wildlife.

The differences we observed in baseline attitudes toward wildlife across states could be due to a multitude of factors, including frequency of interactions with wildlife, level of exposure to conservation efforts and hyper local variability in cultural attitudes towards wildlife. Karnataka and Tamil Nadu have higher densities of wildlife and more intact wildlife habitat left than Goa, which could explain why students in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu have more positive baseline attitudes (CEPF, 2016; Goa Forest Department, 2023; MadhuSudan et al., 2015). The three southern states of Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala are home to a large share of India’s threatened endemic species, accounting for 51% of the country’s species threat abatement score (Chaudhary et al., 2022). This biodiversity richness, combined with recent conservation initiatives, may increase awareness and positive attitudes toward wildlife conservation in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu compared to Goa. For example, Tamil Nadu has focused on sensitization programs in villages near sanctuaries and national parks to mitigate human-wildlife conflict, which may have contributed to more positive attitudes among children (Kanagavel et al., 2013). In Karnataka, the presence of large, interconnected forest landscapes enhances opportunities for communities to interact with wildlife (Jayadevan et al., 2020; Karanth and Vanamamalai, 2020; Nayak et al., 2020). Karnataka has undertaken significant efforts to protect wildlife through initiatives like expanding protected areas and connecting fragmented forests to create unbroken habitats. In 2019, Karnataka expanded the Sharavathi Valley protected area to create a sanctuary dedicated to the endangered lion-tailed macaque. The state has also worked on securing elephant corridors like Kollegal (Edayarhalli-Doddasampige) corridor to provide safe passage for over a thousand elephants, minimizing human-wildlife conflict. These measures not only aid conservation but also raise awareness among local populations about the importance of wildlife preservation (Daniels et al., 1993; Sarmah, 2019).

Unlike Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, which are home to extensive forested areas (16.13% for Karnataka and 16.4% in Tamil Nadu (Forest Survey of India, 2021)) and significant wildlife reserves, Goa has relatively smaller and fragmented wildlife habitats. Studies have shown that proximity to natural habitats and time spent in nature fosters a stronger connection and more positive attitudes towards the environment (Soga and Gaston, 2016). Goa’s rapid urbanization and tourism-driven economy (Sutheeshna, 2021; World Bank, 1998) may result in children spending more time in urban settings with less exposure to nature (Chawla, 2020). Children in urban areas tend to have lower awareness and appreciation for wildlife due to reduced interaction with natural environments compared to rural counterparts (Mariki, 2016; Strife and Downey, 2009). Added to this, conservation efforts in Goa often prioritize marine biodiversity, mangroves, and coastal ecosystems due to their ecological significance and economic value for tourism and fisheries (Usmani and Ansari, 2020; WWF-India, 2016). This focus might overshadow terrestrial wildlife conservation efforts, leading to lower engagement with land-based species among children.

The differences we observed in baseline attitudes toward wildlife may also be attributed to the complex interplay of cultural, social, and political differences across states. Studies in other countries have demonstrated differences in attitudes toward wildlife across cultural groups in the same region. In Qatar, a study compared attitudes towards five threatened animal species among diverse cultural groups, including Western, South East Asian, Middle Eastern and Sub-Saharan African populations, living in the same geographic area. The study found significant cultural differences in liking and endorsement of government protection for these species. For example, Western and South East Asian participants showed more positive attitudes than participants from the Arabian Gulf region, despite living in the same environment (Bruder et al., 2022). Another study conducted in China with two ethnic groups, The Yi and the Mosuo, showed that, in spite of residing in the same geographic area, the Mosuo people demonstrated more positive attitudes towards wildlife conservation than the Yi, highlighting the role that cultural factors play in shaping conservation perspectives (Yang et al., 2010).

Our findings also highlight several policy implications for the design and implementation of large-scale environmental education programs in biodiversity hotspots. First, when scaling across states or regions, it is important to adapt program delivery to local cultural and ecological contexts while maintaining core curricular consistency. Policies that enable flexible, region-specific content adaptation, while ensuring a shared framework of learning objectives, are likely to be more effective than strictly standardized approaches. Second, investment in educator training and ongoing support is critical. Since we found potential variation in outcomes across states that may relate to differences among educators, state-level education departments and conservation agencies should consider establishing training and mentoring systems for environmental educators, ensuring program fidelity and quality at scale. Finally, long-term monitoring and evaluation should be incorporated into policy frameworks. Mandating follow-up assessments would allow programs like Wild Shaale to track not only short-term knowledge gains but also longer-term shifts in attitudes and behaviors. Embedding such evaluation mechanisms within existing education policy could help governments and NGOs better allocate resources and improve program designs.

Our study demonstrates that Wild Shaale is a scalable education program that is effective across diverse cultural, political and ecological contexts in the Western Ghats biodiversity hotspot. With over 32 million children (0–13 years of age; projections from Ministry of Education, 2023) living in the six states that include the Western Ghats biodiversity hotspot, the scalability of EE programs is critical to make these programs accessible to more students. Programs like Wild Shaale can play an important role in conservation by increasing local environmental literacy and maintaining or improving positive attitudes toward wildlife. Importantly, they can also help supplement more generalized environmental knowledge with information specific to particular ecosystems or hotspots.

5 Conclusions

This study evaluated the effectiveness and scalability of the Wild Shaale environmental education program across three Indian states in the Western Ghats. We found consistent gains in knowledge among participating students, with one exception for one question in one state. While these differences may reflect contextual and educator-related factors, the overall pattern demonstrates that structured, school-based EE can be implemented effectively at scale.

At the same time, our findings underscore several limitations. The evaluation design was short-term, without follow-up to test persistence of change. Educator variability likely contributed to state-wise differences, and the program was assessed primarily through immediate pre- and post-session comparisons. Future research should incorporate long-term tracking and experimental designs that better isolate educator and contextual effects. Despite these caveats, this study highlights important lessons for policy and practice. Scaling EE programs across diverse regions requires balancing standardized content with cultural and ecological adaptation, strengthening educator training and support, and embedding monitoring and evaluation into education policy. Programs like Wild Shaale provide a promising model for large-scale environmental education, with the potential to improve coexistence between people and wildlife in biodiversity hotspots worldwide.

Data availability statement

The raw data presented in this article are not readily available because it contains sensitive interview information and personal details of children. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Centre for Wildlife Studies, Bengaluru, India; approval number: CWS_IRB_2020_002. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

KK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SU: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Software. GS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We would like to thank our donors Axis Bank, HCL Foundation, Manipal Foundation, National Geographic Society, Rainmatter Foundation, Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, Rolex, Sundaram Finance, Tiger Global Foundation, United States Fish and Wildlife Services (grant number: F19AP00354) and Wild Elements Foundation for financially supporting this program. The authors declare that this study received funding from Axis bank. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Goa, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu Government Education Departments. We would also like to thank all the educators and field team members, Nitya Satheesh, Ganesh Honwad, Sahil Pimpale, Mahesh Kumar, Nikhil Jambhale, Soumya Sharada, Ronil Gosavi, Shravani Mangeshkar, Shivani Deshpande, Nandhini M., Prakash G., N. Pradeep Kumar, Selvalakshmi O., Vaishali S.P., Mohana Kumar, Vipritha V.Y., Niranjan Natesh, Vikshita Vinayak, Vaibhavi Ganesh and Kaushik Bhandary for conducting the Shaale sessions in the schools.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2025.1659491/full#supplementary-material

References

Arumugam K. A., Ismail N. H. S., Shohaimi S., and Annavi G. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of wildlife educational program on knowledge, attitude and awareness among three selected secondary school students in Perak, Malaysia. Int. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. Res. 2, 176–189.

Balasubramanian M. and Sangha K. K. (2023). Valuing ecosystem services applying indigenous perspectives from a global biodiversity hotspot, the Western Ghats, India. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2023.1026793

Ballantyne R., Fien J., and Packer J. (2001). Program effectiveness in facilitating intergenerational influence in environmental education: lessons from the field. J. Environ. Educ. 32, 8–15. doi: 10.1080/00958960109598657

Bawa K. S., Joseph G., and Setty S. (2007). Poverty, biodiversity and institutions in forest-agriculture ecotones in the Western Ghats and Eastern Himalaya ranges of India. Agriculture Ecosyst. Environment Biodiversity Agric. Landscapes: Investing without Losing Interest 121, 287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2006.12.023

Behera D., Menon M D., Wilson V. K., and Ayyappan N. (2025). Tree diversity, community structure and aboveground biomass of a lowland dipterocarp forest of Western Ghats, India. Trees Forests People. 22, 101048. doi: 10.1016/j.tfp.2025.101048

Binoy V. V., Kurup A., and Radhakrishna S. (2021). The extinction of experience in a biodiversity hotspot: rural school children’s knowledge of animals in the Western Ghats, India. Curr. Sci. 121, 313–316. doi: 10.18520/cs/v121/i2/313-316

Biodiversity in Goa (n.d). (Goa Foundation). Available online at: https://goafoundation.org/biodiversity-in-goa/ (Accessed 7.3.25).

Bist S. S., Cheeran J. V., Choudhury S., Barua P., and Misra M. K. (2002). The Domesticated Asian elephant in India (Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).

Brislin R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cultural Psychol. 1, 185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301

Bruder J., Burakowski L. M., Park T., Al-Haddad R., Al-Hemaidi S., Al-Korbi A., et al. (2022). Cross-cultural awareness and attitudes toward threatened animal species. Front. Psychol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.898503

Castillo-Huitrón N. M., Naranjo E. J., Santos-Fita D., Peñaherrera-Aguirre M., Prokop P., Cisneros R., et al. (2024). Influence of human emotions on conservation attitudes toward relevant wildlife species in El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Biodivers Conserv. 33, 2423–2439. doi: 10.1007/s10531-024-02863-4

CEPF (2016). Final Assessment of the Western Ghats Biodiversity Hotspot: Consolidation of the Ecosystem Profile (Arlington, Virginia, USA: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund).

Chaudhary A., Mair L., Strassburg B. B. N., Brooks T. M., Menon V., and McGowan P. J. K. (2022). Subnational assessment of threats to Indian biodiversity and habitat restoration opportunities. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 054022. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac5d99

Chawla L. (2020). Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: A review of research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People Nat. 2, 619–642. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10128

Christensen R. H. B. (2024). ordinal: Regression Models for Ordinal Data. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ordinal.

Cincotta R. P., Wisnewski J., and Engelman R. (2000). Human population in the biodiversity hotspots. Nature 404, 990–992. doi: 10.1038/35010105

Damerell P., Howe C., and Milner-Gulland E. J. (2013). Child-orientated environmental education influences adult knowledge and household behaviour. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 15016. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/8/1/015016

Daniels R. J. R., Chandran M. D. S., and Gadgil M. (1993). A strategy for conserving the biodiversity of the uttara kannada district in south India. Environ. Conserv. 20, 131–138. doi: 10.1017/S0376892900037620

Dettmann-Easler D. and Pease J. L. (1999). Evaluating the effectiveness of residential environmental education programs in fostering positive attitudes toward wildlife. J. Environ. Educ. 31, 33–39. doi: 10.1080/00958969909598630

Ernst J. and Theimer S. (2011). Evaluating the effects of environmental education programming on connectedness to nature. Environ. Educ. Res. 17, 577–598. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2011.565119

Espinosa S. and Jacobson S. K. (2012). Human-wildlife conflict and environmental education: evaluating a community program to protect the andean bear in Ecuador. J. Environ. Educ. 43, 55–65. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2011.579642

Forest Survey of India (2021). India State of Forest Report 2021 (Dehradun, India: Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, Dehradun).

Gifford R. and Sussman R. (2012). “Environmental Attitudes,” in The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology. Ed. Clayton S. D. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199733026.013.0004

Goa Forest Department (2023). Inventorisation of Faunal Resources (Goa, India: Department of Forests, Government of Goa).

Gorenflo L. J., Romaine S., Mittermeier R. A., and Walker-Painemilla K. (2012). Co-occurrence of linguistic and biological diversity in biodiversity hotspots and high biodiversity wilderness areas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 8032–8037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117511109

IUCN (2016). . Governance of Natural Resources: Uncovering Tensions and Synergies between Human Rights and Conservation (Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature).

Jayadevan A., Nayak R., Karanth K. K., Krishnaswamy J., DeFries R., Karanth K. U., et al. (2020). Navigating paved paradise: Evaluating landscape permeability to movement for large mammals in two conservation priority landscapes in India. Biol. Conserv. 247, 108613. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108613

Jerger A. D., Acker M., Gibson S., and Young A. M. (2022). Impact of animal programming on children’s attitudes toward local wildlife. Zoo Biol. 41, 469–478. doi: 10.1002/zoo.21702

Joppa L. N., Loarie, Scott R., and Nelson A. (2010). Measuring population growth around tropical protected areas: current issues and solutions. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 3, 117–121. doi: 10.1177/194008291000300201

Kaiser F. G., Brügger A., Hartig T., Bogner F. X., and Gutscher H. (2014). Appreciation of nature and appreciation of environmental protection: How stable are these attitudes and which comes first? Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 64, 269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2014.09.001

Kale M. P., Chavan M., Pardeshi S., Joshi C., Verma P. A., Roy P. S., et al. (2016). Land-use and land-cover change in Western Ghats of India. Environ. Monit Assess. 188, 387. doi: 10.1007/s10661-016-5369-1

Kalpana ச (2024). Elephants (Elephas maximus) and the malasar tribes of tamil nadu. Int. J. Tamil Lang. Literary Stud. 6, 31–45. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10590686

Kanagavel A., Pandya R., Sinclair C., Prithvi A., and Raghavan R. (2013). Community and conservation reserves in southern India: status, challenges and opportunities. J. Threatened Taxa. 5, 5256–5265. doi: 10.11609/JoTT.o3541.5256-65

Karanth K. K., Gopalaswamy A. M., DeFries R., and Ballal N. (2012). Assessing patterns of human-wildlife conflicts and compensation around a central Indian protected area. PloS One 7, e50433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050433

Karanth K. K. and Kudalkar S. (2017). History, location, and species matter: insights for human–wildlife conflict mitigation from India. Hum. Dimensions Wildlife 22, 331–346. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2017.1334106

Karanth K. K. and Ranganathan P. (2018). Assessing human–wildlife interactions in a forest settlement in sathyamangalam and mudumalai tiger reserves. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 11, 1940082918802758. doi: 10.1177/1940082918802758

Karanth K. K. and Vanamamalai A. (2020). Wild seve: A novel conservation intervention to monitor and address human-wildlife conflict. Front. Ecol. Evol. 8. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2020.00198

Karnataka Forest Department (2025). Annual Report 2024–25 (April 2024 to March 2025) (Bengaluru, Karnataka, India: Government of Karnataka).

Kolb D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall).

Kumar M. A., Mudappa D., and Raman T. R. S. (2010). Asian elephant elephas maximus habitat use and ranging in fragmented rainforest and plantations in the anamalai hills, India. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 3, 143–158. doi: 10.1177/194008291000300203

Lenth R. V., Banfai B., Bolker B., Buerkner P., Giné-Vázquez I., Herve M., et al. (2025). Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans.

Liordos V., Kontsiotis V. J., Anastasiadou M., and Karavasias E. (2017). Effects of attitudes and demography on public support for endangered species conservation. Sci. Total Environ. 595, 25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.241

Liu J. and Green R. J. (2024). Children’s pro-environmental behaviour: A systematic review of the literature. Resources Conserv. Recycling 205, 107524. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2024.107524

Liu J., Yong D. L., Choi C.-Y., and Gibson L. (2020). Transboundary frontiers: an emerging priority for biodiversity conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 35, 679–690. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2020.03.004

MadhuSudan M. D., Sharma N., Raghunath R., Baskaran N., Bipin C. M., Gubbi S., et al. (2015). Distribution, relative abundance, and conservation status of Asian elephants in Karnataka, southern India. Biol. Conserv. 187, 34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.04.003

Magimairaj D. and Balamurugan D. S. (2017). Socio economic status and issues of toda tribes in Nilgiris district: A study. Int. J. Advanced Res. Dev. 2, 104–106.

Manfredo M. J. (2008). “Norms: social Influences on Human Thoughts About Wildlife,” in Who Cares About Wildlife? Social Science Concepts for Exploring Human-Wildlife Relationships and Conservation Issues. Ed. Manfredo M. J. (Springer US, New York, NY), 111–139. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77040-6_5

Mariki S. B. (2016). Pupils awareness and attitudes towards wildlife conservation in two districts in Tanzania. Asian J. Humanities Soc. Stud. 4, 142–150.

Monastersky R. (2014). Biodiversity: Life – a status report. Nat. News 516, 158. doi: 10.1038/516158a

Murali G., Gumbs R., Meiri S., and Roll U. (2021). Global determinants and conservation of evolutionary and geographic rarity in land vertebrates. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe5582. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe5582

Musser L. M. and Malkus A. J. (1994). The children’s attitudes toward the environment scale. J. Environ. Educ. 25, 22–26. doi: 10.1080/00958964.1994.9941954

Myers N., Mittermeier R. A., Mittermeier C. G., da Fonseca G. A. B., and Kent J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501

Nair R., Dhee, Patil O., Surve N., Andheria A., Linnell J. D. C., et al. (2020). Sharing spaces and entanglements with big cats: the warli and their waghoba in maharashtra, India. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2021.683356

Nair K. L., Sneha B., and Sunny G. (2022). Cultural documentation and collection development: toda tribes of nilgiris. cjad 6, 1–32. doi: 10.21659/cjad.62.v6n200

Nayak A. D. (2017). Culture of haalakki vokkaligas-A special reference in uttar kannada district. Int. J. History Cultural Stud. 3, 27–31. doi: 10.20431/2454-7654.0301003

Nayak R., Karanth K. K., Dutta T., Defries R., Karanth K. U., and Vaidyanathan S. (2020). Bits and pieces: Forest fragmentation by linear intrusions in India. Land Use Policy 99, 104619. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104619

Penjor U., Kaszta Z. M., Macdonald D. W., and Cushman S. A. (2024). Identifying umbrella and indicator species to support multispecies population connectivity in a Himalayan biodiversity hotspot. Front. Conserv. Sci. 5. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2024.1306051

Ramachandra T. V. and Shivamurthy V. (2023). Ecohydrological footprint and climate trends in lotic ecosystems of central western ghats. Water 15, 3169. doi: 10.3390/w15183169

Ramachandra T. V., Vinay S., Bharath S., and Shashishankar A. (2018). Eco-hydrological footprint of a river basin in western ghats. Yale J. Biol. Med. 91, 431–444.

Ramesh T., Kalle R., Milda D., Gayathri V., Thanikodi M., Ashish K., et al. (2022). Drivers of human-megaherbivore interactions in the eastern and western ghats of southern India. J. Environ. Manage. 316, 115315. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4061753

Rege A., Punjabi G. A., Jathanna D., and Kumar A. (2020). Mammals make use of cashew plantations in a mixed forest–cashew landscape. Front. Environ. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2020.556942

Rickinson M. (2001). Learners and Learning in Environmental Education: A critical review of the evidence. Environ. Educ. Res. 7, 207–320. doi: 10.1080/13504620120065230

Roy S., Hegde H. V., Bhattacharya D., Upadhya V., and Kholkute S. D. (2015). Tribes in Karnataka: Status of health research. Indian J. Med. Res. 141, 673–687. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.159586

Salazar G., Ramakrishna I., Satheesh N., Mills M., Monroe M. C., and Karanth K. K. (2022). The challenge of measuring children’s attitudes toward wildlife in rural India. Int. Res. Geographical Environ. Educ. 31, 89–105. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2021.1897339

Salazar G., Satheesh N., Ramakrishna I., Monroe M. C., Mills M., and Karanth K. K. (2024). Using environmental education to nurture positive human–wildlife interactions in India. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 6, e13096. doi: 10.1111/csp2.13096

Sarmah D. (2019). Wildlife Management in karnataka: A forester’s Perspective (Chennai, India: Notion Press).

Sharma S. and Kumar R. (2021). Sacred groves of India: repositories of a rich heritage and tools for biodiversity conservation. J. For. Res. 32, 899–916. doi: 10.1007/s11676-020-01183-x

Sharma P. K. and Menon S. (n.d). Compulsory environmental Education in INDIA - A Case Study (Washington DC, USA: Global Environmental Education Partnership).

Sidhu S., Raman T. R. S., and Mudappa D. (2015). Prey abundance and leopard diet in a plantation and rainforest landscape, Anamalai Hills, Western Ghats. Curr. Sci. 109, 323–330.

Singh R., Negi R., Gonji A. I., Sharma N., and Sharma R. K. (2024). Past shadows and gender roles: Human-elephant relations and conservation in Southern India. J. Political Ecol. 31, 604–623. doi: 10.2458/jpe.2834

Soga M. and Gaston K. J. (2016). Extinction of experience: the loss of human–nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 14, 94–101. doi: 10.1002/fee.1225

Strife S. and Downey L. (2009). Childhood development and access to nature. Organ Environ. 22, 99–122. doi: 10.1177/1086026609333340

Sutheeshna B. S. (2021). “Tourism, urbanization and Spatial Reorganization: Some Reflections on Tourism Development in Goa, India,” in Reflections on 21st Century Human Habitats in INDIA: Felicitation Volume in Honour of Professor M. H. Qureshi. Eds. Jaglan M. S. and Rajeshwari (Springer, Singapore), 219–242. doi: 10.1007/978-981-16-3100-9_9

Trew B. T. and Maclean I. M. D. (2021). Vulnerability of global biodiversity hotspots to climate change. Global Ecol. Biogeography 30, 768–783. doi: 10.1111/geb.13272

UNESCO World Heritage Centre (n.d). Western Ghats (UNESCO World Heritage Centre). Available online at: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1342/ (Accessed 7.3.25).

Usmani S. M. P. A. and Ansari Z. A. (2020). Status of Coastal marine biodiversity of goa and challenges for sustainable management - an overview. J. Ecophysiology Occup. Health. 20, 222–231. doi: 10.18311/jeoh/2020/25771

Vaughan C., Gack J., Solorazano H., and Ray R. (2003). The effect of environmental education on schoolchildren, their parents, and community members: A study of intergenerational and intercommunity learning. J. Environ. Educ. 34, 12–21. doi: 10.1080/00958960309603489

Wheaton M. A., Kannan S. S., and Ardoin N. M. (2018). The Concept of Dosage in Environmental and Wilderness Education (No. Environmental Literacy Brief Volume 4) (Stanford University: Social Ecology Lab).

Wickham H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 2nd ed (New York, New York, USA: Springer International Publishing). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4

World Bank (1998). Tourism and the Environment Case Studies on Goa, India and the Maldives (Washington, DC: The World Bank).

Yang N., Zhang E., and Chen M. (2010). Attitudes towards wild animal conservation: a comparative study of the Yi and Mosuo in China. Int. J. Biodiversity Science Ecosystem Serv. Manage. 6, 61–67. doi: 10.1080/21513732.2010.509630

Keywords: environmental education, Western Ghats, Wild Shaale, conservation education, experiential learning, human-wildlife conflict, India, biodiversity hotspot

Citation: Karanth KK, Unnikrishnan S and Salazar G (2025) From classrooms to conservation: scaling environmental education across India’s Western Ghats. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6:1659491. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1659491

Received: 04 July 2025; Accepted: 30 October 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Thomas H. Beery, Kristianstad University, SwedenReviewed by:

Claudia Marcia Lyra Pato, University of Brasilia, BrazilSepti Kurniasih, Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Karanth, Unnikrishnan and Salazar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sruthi Unnikrishnan, c3J1dGhpLnVubmlrcmlzaG5hbkBjd3NpbmRpYS5vcmc=

Krithi K. Karanth

Krithi K. Karanth Sruthi Unnikrishnan

Sruthi Unnikrishnan Gabby Salazar

Gabby Salazar