- San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, Volcano, HI, United States

In the midst of Earth’s sixth mass extinction, conservation breeding can serve as a vital component of critically endangered species recovery. The effect of an individual or pair’s breeding experience on fitness has been evaluated across numerous avian taxa, but research on how experience impacts breeding outcomes for critically endangered birds in human care is scarce. In this retrospective study, we examined whether breeding experience impacted reproductive success in a conservation breeding program (CBP) for the last remaining and critically endangered Hawaiian corvid, the ‘Alalā (Hawaiian crow, Corvus hawaiiensis). We evaluated whether experience was predictive of nest quality, clutches, fertilized eggs, and incubation. We determined that breeding experience positively impacted all reproductive stages, except for egg fertilization. Our results can be used to inform breeding pair selection, for example, pairing an Expert with an inexperienced individual may lead to better reproductive outcomes compared to pairing two Novice individuals. Broadly, our study presents an approach for quantitatively evaluating experience effects on reproduction in CBPs and showcases the value of leveraging routinely collected data to facilitate evidence-based decisions, that will lead to optimizing the conservation value of a CBP through maximizing reproductive success.

Introduction

As the world navigates its sixth mass extinction (Dirzo et al., 2022), conservationists endeavor to save species with a variety of tools. Bringing critically endangered species into human care for conservation breeding is one tool for preventing extinction (Bolam et al., 2021; Conde et al., 2011; Crates et al., 2023), but comes with numerous challenges that must be overcome to ensure species recovery goals are met (Snyder et al., 1996), with many conservation breeding programs (CBPs) unfortunately falling short of meeting their objectives (Asa et al., 2011). Given the resource-intensive and costly nature of CBPs, it is important to understand factors contributing to or limiting CBP success, with implications for guiding management decisions and assessing the conservation value of a CBP and achieving overall recovery goals. Knowledge of what works and what doesn’t with respect to optimizing CBP success can impact the allocation of resources (e.g., infrastructure for housing animals), timing of releases, and – eventually – triggering CBP exit strategies (Ruiz-Miranda et al., 2020). Of course, reproductive variation stems from a variety of factors, including genetics (Flanagan et al., 2021; Hoeck et al., 2015), personality compatibility (Flanagan et al., 2024b; Martin-Wintle et al., 2017), age (Barrett et al., 2024), and breeding experience (Breen et al., 2016; Muth and Healy, 2014). The failure of practitioner-selected breeding pairs to exhibit the necessary breeding behaviors that lead to offspring production is one significant barrier to CBP success, which is often attributed to pair incompatibility (Asa et al., 2011). Moreover, the variability in breeding outcomes among (or within) pairs in CBPs can make it difficult to reasonably estimate the number of offspring that may be produced in a breeding season and hinders educated guesses about which pairs are most likely to succeed. Thus, to begin making sensible predictions, it is important to identify the characteristics of individual birds and pairs that translate to a higher probability of reproduction, ideally with clear, tangible, and direct implications for guiding breeding pair selection, arguably one of the biggest challenges faced by CBP practitioners (Martin-Wintle et al., 2019).

Human-mediated pair selection comprises an essential prerequisite to offspring production in CBPs, and involves choosing mates based on a suite of hierarchical criteria, including maintaining founder representation, minimizing inbreeding, and considering population demographics (Hedrick et al., 2016; Hoeck et al., 2015). However, it is unfortunately not possible to avoid inbreeding entirely in small assurance populations (Flanagan et al., 2021). Indeed, managing for genetics can be a significant challenge in CBPs, especially since more optimal genetic pairings can sometimes select for individuals that are behaviorally incompatible. Thus, there are other criteria for consideration, further along the pair selection process, to optimize the likelihood of reproductive success, which may include the potential for pair compatibility (as anecdotally assessed by caretakers or with mate choice studies) (Ihle et al., 2015; Martin-Wintle et al., 2019; Munson et al., 2020), the personality composition of prospective pairs (Flanagan et al., 2024; Martin-Wintle et al., 2017), and the breeding history of individuals or established pairs. Of course, many factors determine whether pairs will breed successfully or not. In addition to targeted hypothesis-driven research interventions, CBP practitioners can leverage routinely collected data to identify factors that influence reproduction to shape breeding pair selection protocols for improved CBP productivity.

Breeding experience is one potential precursor to reproductive success (Dubey et al., 2018; Dukas, 2019), as animals learn reproductive behaviors (e.g., pair bonding and rearing offspring) that lead to an increase in fitness, which can happen through different pathways including trial-and-error (Muth and Healy, 2014) and social transmission of behaviors from conspecifics (Breen et al., 2016) or heterospecifics (Loukola et al., 2014). Moreover, the positive impact of experience on reproduction can manifest in pairs with an experienced male and female, or can be sex-dependent, where the experience of one sex is more determinant of breeding outcomes than the other (Lv et al., 2016; Peralta-Sánchez et al., 2020; Pitera et al., 2021). While previous studies have examined the effect of experience on reproductive outcomes, details regarding the specific behaviors acquired with experience are largely understudied. In the hair-crested drongo (Dicrurus hottentottus), inexperienced pairs fledged fewer offspring than experienced pairs, particularly when females were coupled with inexperienced males (Lv et al., 2016). In captive house sparrows (Passer domesticus) experience of the female was more predictive of fledging success than male experience (Peralta-Sánchez et al., 2020), whereas in the monogamous mountain chickadee (Poecile gambeli) pairs comprised of experienced males and females had heavier (presumably healthier) nestlings compared to inexperienced pairs (Pitera et al., 2021).

While findings from studies conducted in the wild can be used to inform breeding pair selection protocols for species in CBPs, relying too heavily on information about the natural mating system of wild animals may be inadequate for animals in human care, as captive environments may lead to different mating dynamics than observed in nature, with their own set of drivers of reproductive success (Price and Stoinski, 2007; Swaisgood and Schulte, 2010). Moreover, captive animals may not respond to processes or stimuli that mimic their natural systems in the same way as their wild counterparts (Bond and Watts, 1997). Similarly, it is unclear whether the impact of experience on reproduction in captivity can be extrapolated to the wild. Thus, it is important to test predictions about whether various factors, such as breeding experience, impact reproductive success of animals in human care, rather than making assumptions based on what is known about reproduction in the wild. To our knowledge, little or no work has been done to examine the role of breeding experience on reproduction within CBPs, particularly for birds. Animals, especially those that are socially monogamous, in long-running CBPs are prime candidates for conducting empirical, retrospective analyses on how breeding experience impacts reproductive success, as the breeding history of all captive-born and reared individuals is known. Conducting experience studies on non-monogamous captive species would also be valuable, but relatively challenging, since breeding attempts would be difficult, if not impracticable, to accurately track and record in polygynous or polygynandrous mating systems. If breeding experience improves reproductive success in CBPs, managers can use this information to predict and understand reproductive output at the onset of new CBPs (remaining patient for a few seasons while inexperienced birds gain experience) and develop evidence-based protocols to guide husbandry decisions.

The ‘Alalā (Hawaiian crow, Corvus hawaiiensis) is a socially monogamous species, forming long-term pair bonds in the wild (Banko et al., 2002). Nearly all surviving ‘Alalā are in human care, where the species has been undergoing intensive conservation breeding for reintroduction since 1996. The ‘Alalā unfortunately went extinct in the wild in 2002, due to a suite of overlapping threats, including habitat degradation due to ungulate grazing, introduced diseases (avian malaria and pox, and toxoplasmosis), and invasive mammalian predators such as mongoose, cats, and rats (Banko et al., 2002). Previous efforts to reintroduce the species to the wild have not resulted in any established populations to date (Greggor et al., 2025), although there are 5 free-flying birds on Maui at the time of this writing. Despite its socially monogamous mating system, a recent study of mate retention effects on ‘Alalā in human care determined that pair longevity (the cumulative number of breeding seasons together) did not influence reproduction (Barrett et al., 2024). However, both male and female age influenced various aspects of reproduction, but the extent to which the age effects were underpinned by breeding experience is unknown.

In this study, we addressed the question: Does past breeding experience influence future ‘Alalā reproductive success in human care? Moreover, we endeavored to determine if male or female experience is more determinant of reproductive outcomes. Based on previous research findings implicating a positive impact of experience on avian reproduction in other species, we predicted that breeding experience would positively impact the probability of reproductive success. Our results will be incorporated into the pair selection process in husbandry protocols to improve reproductive outcomes in the ‘Alalā CBP. Additionally, and more broadly, our study highlights the value of retrospective analyses to inform pair selection protocols for CBPs.

Methods

‘Alalā conservation breeding

‘Alalā conservation breeding is conducted at the Keauhou Bird Conservation Center (KBCC) on Hawaii Island and the Maui Bird Conservation Center (MBCC) on the island of Maui (Supplementary Figure S1). From 1996 onward, both breeding centers employed intensive avicultural methods, which included the provision of human-made, nest-like structures to facilitate egg laying (see Flanagan et al. (2023) for details) and involved the removal of clutches for artificial incubation and hand-rearing nestlings, to grow the population until it reached ~ 140 individuals in 2018. From 2018 onward, the CBP shifted to mostly parental breeding by allowing the birds to build their own nests, incubate eggs, and rear offspring to encourage birds in human care to perform breeding behaviors essential to eventual reintroduction success (although, the CBP pivoted back to intensive avicultural methods in 2023, to produce individuals for an upcoming release, and continued thereafter). Breeding pairs were selected to minimize inbreeding and maintain founder representation using pedigree-derived pairwise kinship coefficients, complemented with indicators of compatibility, pair personality composition (Flanagan et al., 2024b), or data from ongoing mate choice studies (Greggor et al., unpublished data), which include the performance of affiliative behaviors such as allopreening and allofeeding. Historically pairs were kept together for multiple seasons, as ‘Alalā is a socially monogamous species, even if they were not initially successful. However, as recent findings indicate pair longevity does not impact reproduction, practitioners can now be more proactive with re-pairing birds from unsuccessful pairs in the CBP (Barrett et al., 2024).

Reproductive outcomes

We examined the role of breeding experience on four reproductive milestones in the ‘Alalā CBP: building quality nests, producing clutches, egg fertilization, and incubating eggs to hatch date (22 days after eggs are laid). The breeding seasons used in each analysis varied, depending on the dataset being analyzed, as our data collection efforts have been modified over the years in response to adapting management strategies. The breeding stages we carefully selected to evaluate are essential to offspring production and, importantly, can be addressed by adjusting husbandry practices, with management interventions tailored to target the different stages.

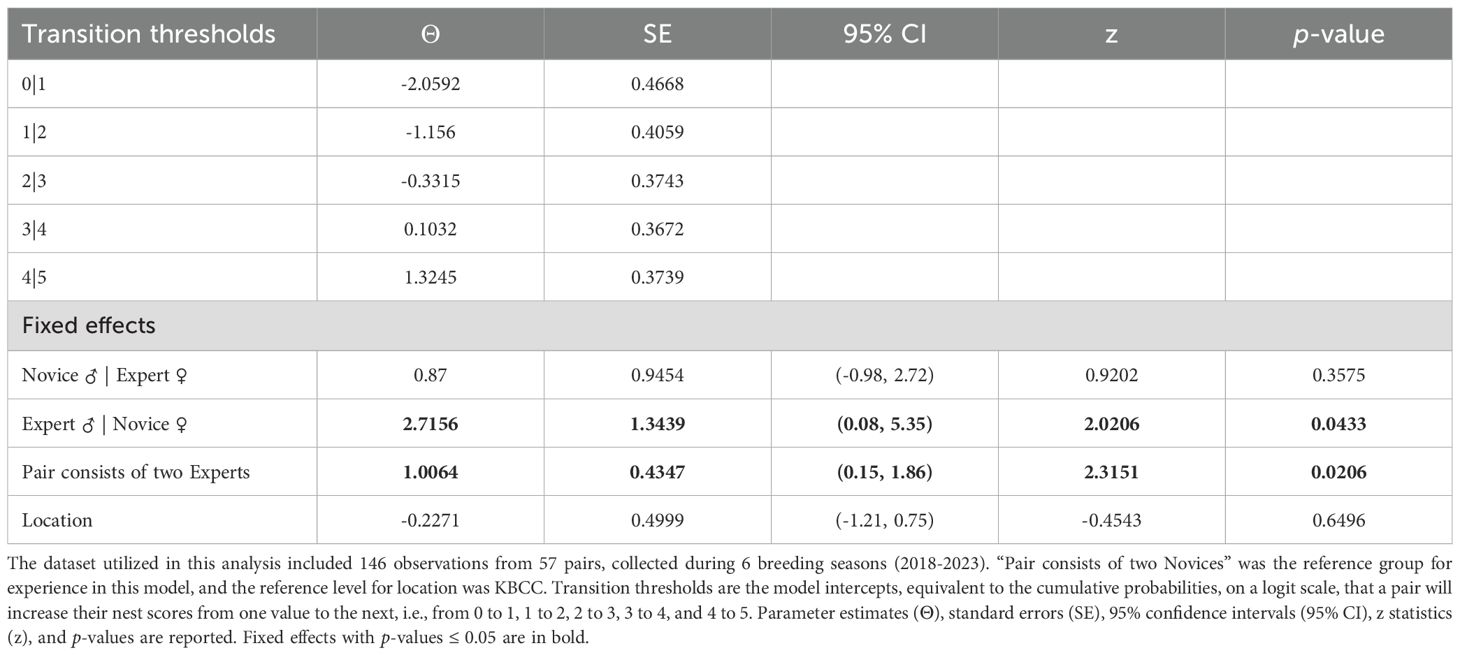

Building robust nests prior to egg laying comprises an important precursor to offspring production in the CBP, as ‘Alalā nest quality varies substantially among pairs. Over half of potential ‘Alalā offspring (eggs) are lost prior to hatch when eggs are laid in low quality nests, due to breaking, cannibalization, or ejecting eggs from the nest (Mason et al., 2024). We measured nest quality from 2018–2023 on a standardized ordinal scale from 1-5, where 1 refers to nests built by ‘Alalā with no or few sticks and a 5 corresponds to a symmetrical nest and nest cup built with both larger, and finer natural materials, respectively. Details on our nest scoring methodology are provided in Flanagan et al. (2023). All nest scores were recorded when a female laid a clutch. Breeding pairs that failed to nest build were assigned a score of 0, to include all pairs in the analysis. In some cases, breeding pairs may have been separated during the nest building process without being captured in the CBP records, but we did not observe a detectable, systematic impact of separations on our results. We utilized nest scores as an ordinal response variable, and this analysis included 146 observations from 57 pairs.

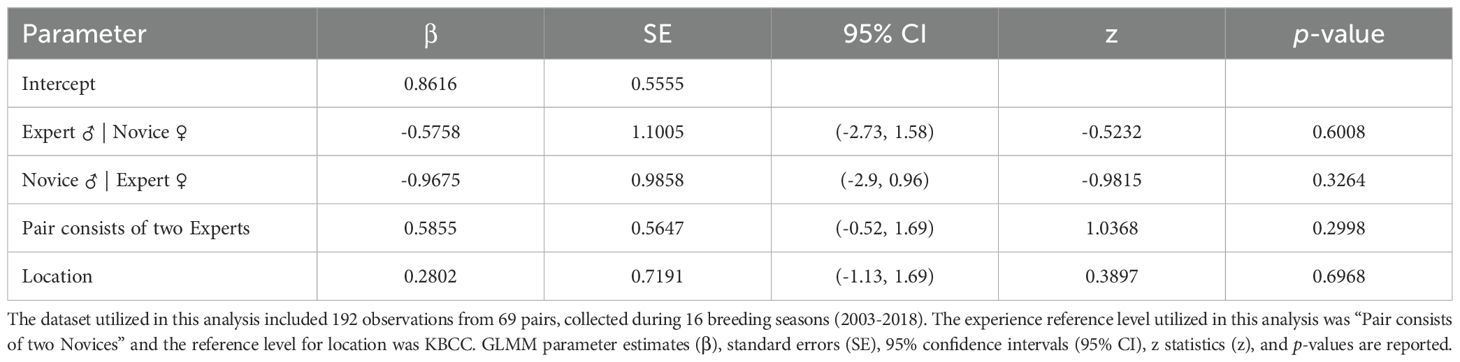

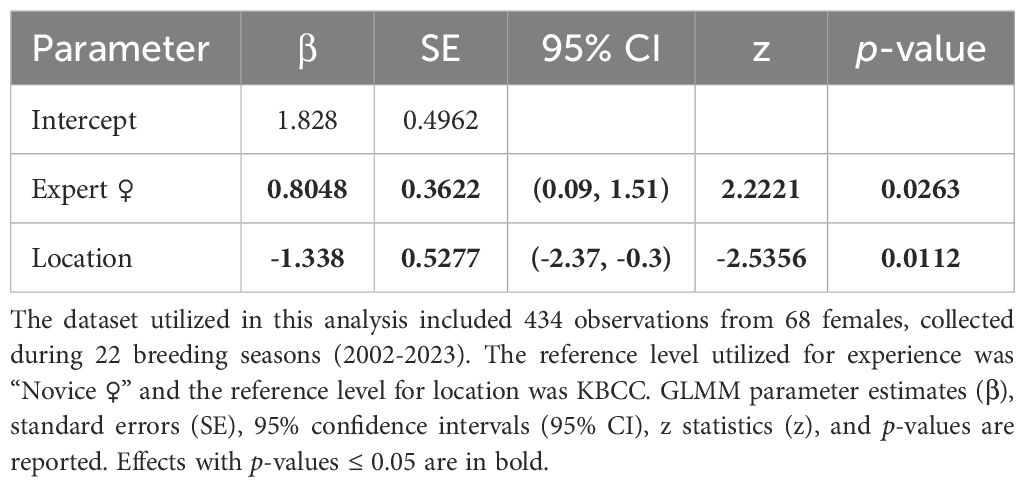

Our clutch production and egg fertilization data were curated from CBP records on all ‘Alalā eggs laid, both of which were included as binary response variables in our analysis (i.e., whether clutches and fertile eggs were produced per breeding season). Reproductive activities were monitored by closed circuit television (CCTV) and in person to determine if, and when, a clutch was laid. Our clutch production analysis included years where most eggs were at least partially artificially incubated (2002-2014; 2016-2017), as well as years where most eggs were fully parent-incubated (2015; 2018-2023) (N = 434 observations from 68 females). For our fertilization analysis, which only included pairs that produced a minimum of one egg per breeding season, we used data from breeding seasons when most eggs were candled for visual signs of fertilization (2003-2018) (N = 192 observations from 69 pairs), unless egg loss (e.g., due to breaking) occurred prior to candling. Our clutch and fertilization analyses were limited to breeding seasons with a minimum of two breeding pairs. We did not always confirm the number of eggs laid per clutch, nor candle all eggs for visual signs of fertilization, particularly when females were incubating eggs, to minimize human disturbance which appeared to have a negative effect in the wild (Banko and Banko, 1980), and not all nests were on CCTV. Moreover, many females were provided with facsimile eggs in years when we removed eggs from the nest for artificial incubation, to prevent females from laying an excessive number of clutches, which artificially influenced the number of clutches laid and eggs produced per clutch. Thus, robustly assessing experience effects on clutch size or the total number of fertile eggs laid was not possible in our study.

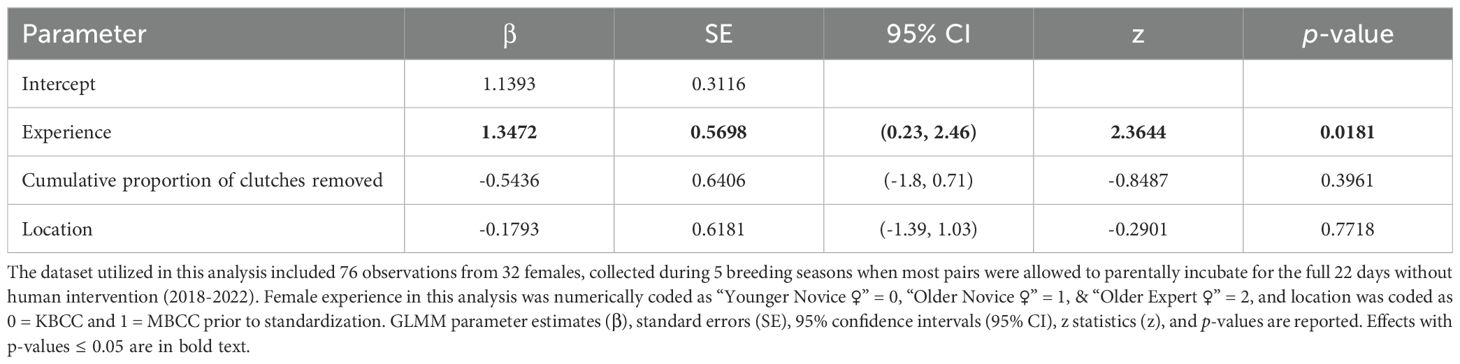

We conducted the egg incubation analysis with data collected from 2018–2022 on lay dates, egg disposition, as well as any terminal events associated with each egg, including whether an egg was broken, eaten, or ejected from the nest prior to 22 days of incubation or whether eggs hatched. This analysis included 76 observations from 32 females. We limited this analysis to eggs laid in nests that have been deemed as adequate for mitigating egg loss (with nest scores ≥ 4) (Mason et al., 2024), to focus the analysis on eggs lost due to incubation behavior. To calculate the incubation duration of each egg, we subtracted the lay date from the date of terminal events. Incubation duration was subsequently used to determine if females incubated their eggs for at least 22 days after lay (or if it hatched, slightly prior to 22 days) (1 = yes, 0 = no), which was utilized as the response variable in our incubation analysis. While males have been occasionally observed incubating eggs or otherwise assisting females at the nests (e.g., allofeeding), females take the predominant role, so we did not include male experience in the egg incubation analysis.

Generally, a small proportion of pairs have parent-incubated hatches in each year (< 0.3), so we did not have a sufficient dataset to reliably estimate the effect of experience on hatching or other downstream reproductive stages, such as nestling survival to fledge.

Experience metrics

With detailed CBP records on each bird’s breeding history, we determined whether birds entered each breeding season as an inexperienced (“Novice”) or experienced (“Expert”) breeder across each reproductive stage examined, based on whether individuals had demonstrated success at each stage in one, or more, previous seasons (also see Supplementary Table S1). While ‘Alalā can engage in breeding attempts at 2–3 years old, there has been notable variation in the onset of breeding behavior in the CBP, yielding data that includes inexperienced breeders of much greater age (Supplementary Figures S2-S5), allowing us to disentangle the effects of age versus experience. To account for potential age effects in our assessment of breeding experience, in a way that also facilitated the interpretability of our results, all birds included in the study were classified as “Younger” (2–3 years old) or “Older” (4–12 years old) and these two categorical age classes were combined with the breeding experience classes (Novice or Expert) resulting in four age-experience categories for analysis: Younger Novice, Younger Expert, Older Novice, or Older Expert, which changed throughout the dataset as birds aged or gained experience over time. Birds ≥ 13 years old show signs of decreased reproductive output (Barrett et al., 2024), so we excluded these individuals from the study. Our nest building and fertilization analyses tested the importance of breeding experience at the pair-level, but our clutch production and incubation analyses examined female experience only. Utilizing the Expert/Novice categories in our study was preferable to continuous measures of experience (e.g., the total number of seasons with experience) as it allowed for exploring experience effects without compromising model stability and maximized the interpretability of our results. Determining whether individuals or pairs are Experts, Novices, or a combination thereof, also comprises a metric that is easily accessible in CBP records, as opposed to re-evaluating each bird’s cumulative breeding successes prior to each season to inform pair selection. Thus, this approach avoids introducing additional complexity with respect to translating our results into actionable insights, hopefully better bridging the gap between science and practice, to maximize uptake.

Statistical analyses

We conducted our statistical analyses in R (R Core Team, 2023). We used mixed models to test for the effects of experience on nest quality, clutch production, egg fertilization, and incubation with pair (or female identity) as a random effect in each model, to account for multiple observations from the same pair or female across different breeding seasons. We also included year as a random effect in all models, but 0 variance was associated with year in our analyses of nest quality, clutch production, and incubation, so it was ultimately removed from those models. While not of direct interest in our study, we included facility (KBCC and MBCC) as a covariate in our analyses to account for differences between sites. We did not attempt to include facility as a random effect because reliable variance estimates require > 2 levels within random effects (Gelman and Hill, 2007; Harrison et al., 2018).

The experience metrics utilized in each analysis varied as described below (but see Supplementary Table S1 for an at-a-glance overview of the data and parameters included in each model). An ordinal cumulative linked mixed model (CLMM) from the ordinal package (Christensen, 2018) was used to test whether experience impacted nest quality scores. The effect of experience on clutch production, egg fertilization, and egg incubation was tested with generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs), conducted with the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015). Model assumptions of the CLMM and GLMMs were tested with the ordinal (Christensen, 2018) and DHARMa (Hartig, 2022) packages, respectively.

We initially used the age-experience classes of pairs (e.g., coupling a Younger Novice ♂ with an Older Expert ♀ and so on) or individual females (e.g., Older Expert ♀ vs. Younger Novice ♀, etc.) as categorical fixed effects in the analyses of nest building, clutch production, and egg fertilization, but, in addition to issues with model convergence, there were too few observations in some of the age-experience classes established for each pair or individual. Moreover, removing the age-experience classes with too few observations did not resolve convergence issues. Thus, as an alternative to the age-experience classes in these models, we focused these analyses on the experience metrics only, i.e., whether pairs were comprised of two Novices, whether pairs contained an Expert male or Expert female (coupled with a Novice partner), or whether pairs consisted of two Experts (or Expert vs. Novice females only, for clutch production). However, we were able to use the female age-experience classes as the fixed effect in the incubation model without issue, after standardization (see below). While this means we were unable to include age-experience effects or interaction terms in our mixed models for nest building, clutch production, and fertilization, we conducted visual assessments based on summary statistics of the data to look for patterns with age and experience effects on each of the reproductive stages examined, by comparing the proportion of pairs in each age-experience class that achieved each reproductive milestone. Because the removal of clutches by caretakers for artificial incubation comprised a process regularly experienced by some females included in our study, we also tested whether the cumulative proportion of clutches removed over each female’s lifetime impacted the probability that females would successfully incubate eggs for 22 days. The cumulative proportion of clutches removed was calculated by taking the sum of clutches removed ÷ clutches laid over each female’s lifetime, up to each focal season in the analysis. It is important to note that the proportion of clutches removed per female may overlook some potentially important inter-individual differences relevant to experience, but, we were unable to utilize total clutches laid and total clutches removed for artificial incubation as separate fixed effects in our incubation model, as these two variables were highly correlated (both with variance inflation factors > 5) (Fox and Weisburg, 2019). As the proportion of clutches removed from each female was included in this analysis, in addition to female experience and site, we numerically coded the female age-experience classes as Younger Novice ♀ = 0, Older Novice ♀ = 1, and Older Expert ♀ = 2 (there were no Younger Expert ♀s in the dataset) and coded site as KBCC = 0, MBCC = 1, so that we could standardize all fixed effects with the rescale function from the arm package (Gelman and Su, 2018), prior to running the incubation analysis, to obtain meaningful effect size estimates from this model.

Results

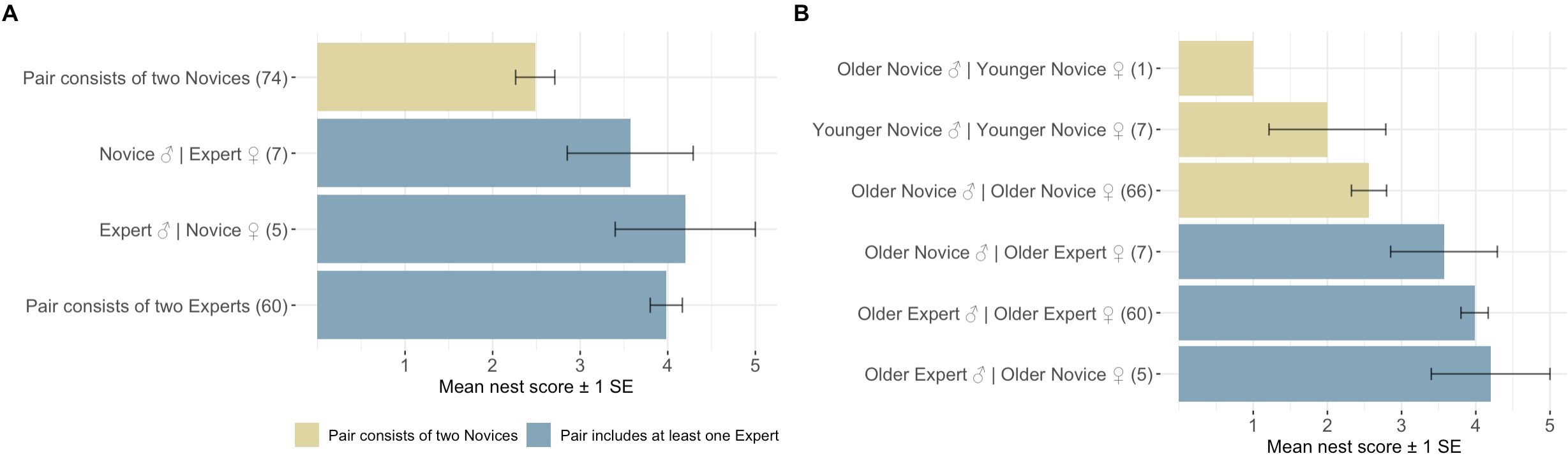

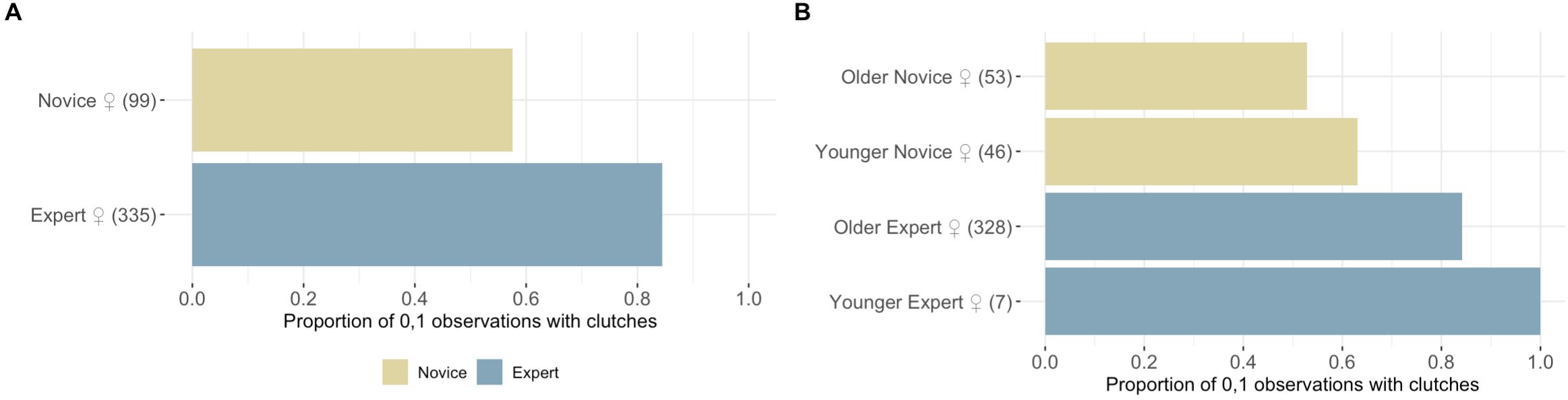

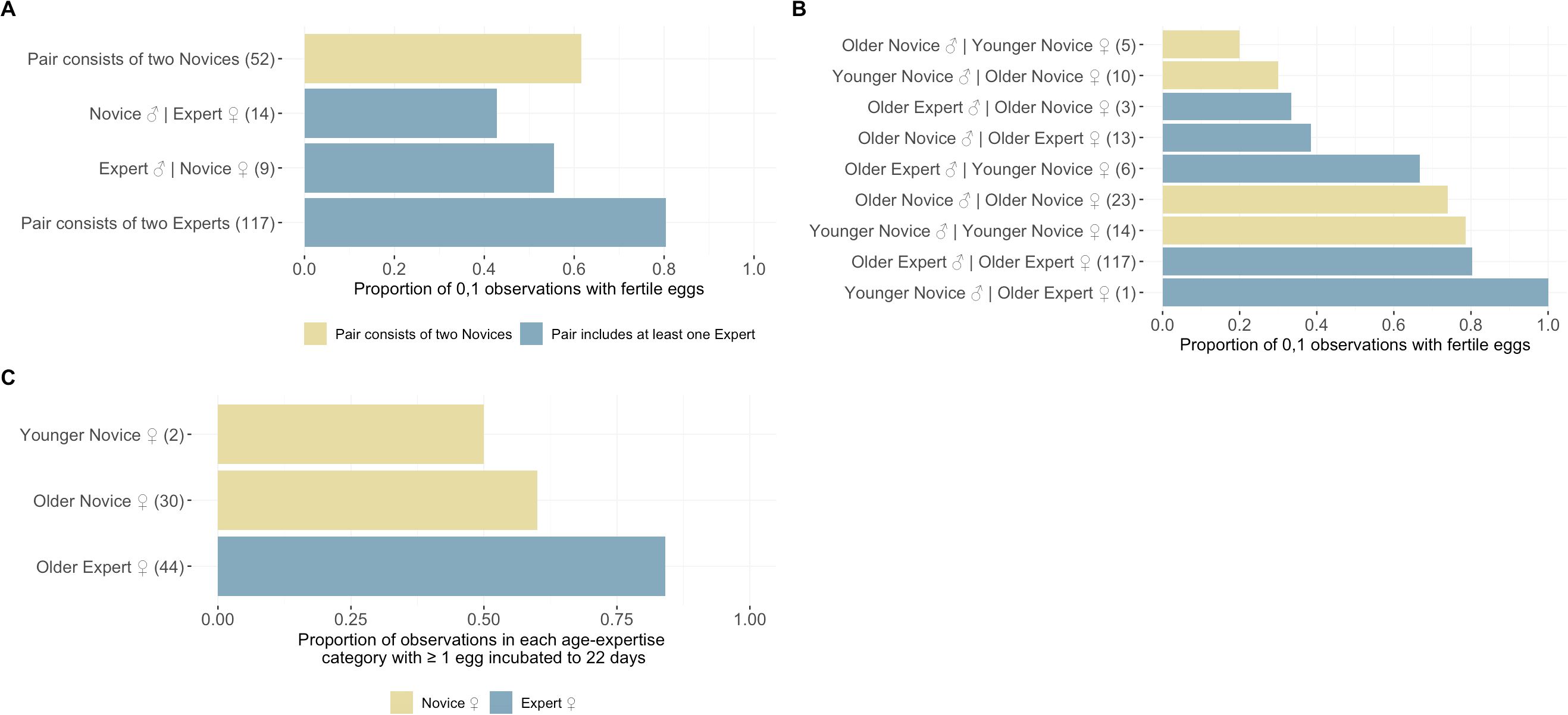

Our results suggest breeding experience positively impacted the probability of ‘Alalā reproductive success with respect to building quality nests, clutch production, and egg incubation; however, we failed to detect an effect of pair experience on egg fertilization (Tables 1–4, Figures 1–3). Pairs comprised of two Experts and pairs with an Expert male and Novice female achieved significantly higher nest scores compared to pairs of two Novices (Table 1, Figure 1A). Pairs with an Expert female and Novice male also achieved higher nest scores compared to pairs comprised of two Novices, but this difference was statistically insignificant (Table 1). We also determined that Expert females were more likely to produce clutches (Table 2, Figure 2A) and incubate eggs for 22 days compared to their Novice counterparts (Table 4, Figure 3C). In addition, females were more likely to lay at KBCC than MBCC (Table 2). We did not find an effect of clutch removal on a female’s ability to incubate eggs for 22 days in seasons with a focus on parental (over artificial) incubation (Table 4). We also did not see any systematic trends with age and experience in the datasets that were used in the models that did not directly incorporate age (Figures 1B-3B); thus, there were no obvious signs that age confounded our findings regarding the effect of experience on reproduction detected.

Table 2. Results from the GLMM evaluating whether female experience was predictive of clutch production.

Table 4. Results from the GLMM evaluating whether pair experience, age and the cumulative proportion of clutches removed for artificial incubation over each female’s lifetime influenced the ability of females to incubate eggs to 22 days.

Figure 1. (A) Mean nest scores achieved by pairs containing two novices, one expert, or two experts. These were the experience categories used in the CLMM analysis of nest quality. (B) Mean nest scores achieved across the age-experience classes, assigned to each pair, showing no clear systematic trends with age.

Figure 2. Role of experience and age on clutch production. (A) Clutch production by Novice ♀ and Expert ♀ groups. (B) The proportion of observations with clutches across the age-experience classes assigned to each female included in our analysis, showing a clear pattern with female experience, but no clear systematic trends with age.

Figure 3. Role of experience and age on egg fertilization. (A) The overall proportion of observations with fertilized eggs among the pair experience groups used in the GLMM of egg fertilization. (B) The proportion of observations with fertilized eggs across the age-experience classes assigned to each female included in our analysis showing no clear systematic trends with experience or age. (C) The overall proportion of observations with eggs incubated among the female age-experience groups. Female experience in this analysis was numerically coded as “Younger Novice ♀” = 0, “Older Novice ♀” = 1, & “Older Expert ♀” = 2 to facilitate standardization with the cumulative proportion of clutches removed prior to running the GLMM analysis.

Discussion

We determined that breeding experience is associated with a greater probability of building quality nests, clutch laying, and incubating eggs to the expected hatch date, supporting our prediction that breeding experience would translate to better reproductive outcomes in the ‘Alalā CBP. When working with critically endangered species, it is generally not advisable to conduct experimental manipulations. As such, we did not have data on experienced males or females being randomly paired with inexperienced birds available for analysis. But our study nevertheless offers robust and useful insights for management. Our results are broadly consistent with evidence that suggests experience increases fitness in nonhuman animals (Dukas, 2019) and align with previous studies concerning the effect of breeding experience on the avian reproductive cycle, particularly in socially monogamous species (e.g., Lv et al., 2016; Peralta-Sánchez et al., 2020; Pitera et al., 2021). To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study to examine the role of breeding experience on reproductive outcomes in a CBP, using experience metrics that are based on each individual’s breeding history, rather than age alone, as a proxy for experience. Our results offer clear, direct, and tangible implications for guiding decisions regarding pair selection.

Our finding regarding the importance of pair experience on building quality nests suggests that nest building is shaped by learning in ‘Alalā, as has been found in many other taxa (reviewed in Breen et al., 2016) and male ‘Alalā have an important role in nest building. In male southern masked weaverbirds (Ploceus velatus), nest building behaviors changed with experience, leading to smaller nests being constructed by more experienced males (Walsh et al., 2010). In captivity, first-year male Village weavers (Ploceus cucullatus) built looser nests compared to older, more experienced males (Collias and Collias, 1964) and male zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) used less flexible nest materials after gaining experience with nest building (Bailey et al., 2014), adjusting the way they inserted materials into nest boxes with improved dexterity (Muth and Healy, 2014).

Providing opportunities for birds in CBPs to learn is likely vital for supporting better outcomes, leading to the preservation of natural behaviors, development of skills important for post-release survival and reproduction, and counteracting the negative effects of life in captivity (Clark et al., 2023). The diversity, function, and learning mechanisms driving the construction of nests by avian species is only beginning to be understood (Healy et al., 2023). Understanding how these factors contribute to the making of a good nest for each species in human care promises to improve CBP outcomes. At our facilities, we intend to provide all pairs with abundant and diverse nest material options (sticks, grasses, coconut fibers, etc.) and multiple nest platforms (Flanagan et al., 2023), which supports varied learning opportunities with different materials. In our study, two Experts (or Expert males with Novice females) more often constructed high quality nests than when two Novices were paired, demonstrating that these experiences contribute to learning. Future behavioral research would be important to evaluate the effects of experience on the development of nest building behaviors in males and females in a way that would allow for clearly quantifying the contribution of each sex to nest building. Birds can also learn from their failures. Indeed, predictions from models and empirical evidence support the hypothesis that birds should shift to a new nesting location following reproductive failure (Ibáñez-álamo et al., 2015; Switzer, 1993). While birds in human care do not face the same stressors as their wild counterparts (from predation and lack of food, for instance), future work could evaluate whether nest building improves after moving pairs to a different aviary.

In our study, experienced ‘Alalā females were more likely to produce a clutch than inexperienced females, and females were more likely to lay at KBCC, perhaps because for most of the duration of the CBP, birds with higher reproductive output were preferentially housed at this facility where there is a larger number of aviaries that are most optimal for holding pairs. Findings from the few other species examined have been mixed. Clutch size was unaffected by parent experience in house sparrows (Passer domesticus) (Peralta-Sánchez et al., 2020) and hair-crested drongos (Dicrurus hottentottus) (Lv et al., 2016), whereas experienced mountain chickadee females (Poecile gambeli) produced larger clutches than inexperienced females (Pitera et al., 2021). While it is possible that clutch size may be influenced by experience in ‘Alalā, we did not consistently confirm the number of eggs in nests due to the increased likelihood of human disturbance resulting in negative outcomes in this species (Banko and Banko, 1980). The mechanisms underpinning why and how female experience influenced clutch production in our study are unclear. Perhaps experienced females are more likely to produce clutches because of physiological and behavioral improvements to the reproductive system mediated by altered hormonal regulation. Alternatively, selection may be favoring individuals better adapted to captivity, making them more likely to produce clutches and resulting in differential reproductive success. Clutch production in experienced birds may also be a downstream consequence of improved nesting behavior, which may promote hormonal readiness for egg production (Healy et al., 2023).

We were unable to detect an effect of experience on egg fertilization, a disappointing finding given that fertilization rates are low (<50%) in the ‘Alalā (Hoeck et al., 2015) and other avian CBPs (Assersohn et al., 2021) despite high reproductive success of ‘Alalā in the wild (Banko and Banko, 1980). However, we observed a general pattern in the raw data suggesting that assortative mating (pairs consisting of two Novices or two Experts) may lead to a higher probability of fertilization (Figure 3B). Research involving the effect of experience on egg fertilization is limited, so there are few studies for direct comparison. Parental experience in zebra finches (T. guttata) was associated with the amount of sperm reaching the fertilization site (Hurley et al., 2020). In kākāpō (Strigops habroptilus) populations that were translocated to predator-free island sanctuaries, copulation experience (the total number of previously observed copulations) had no effect on fertilization (Digby et al., 2023). In a captive colony of African penguins (Spheniscus demersus), inexperienced individuals were as successful at the fertilization stage as experienced breeders, but hatching nestlings required attaining additional experience or finding an experienced mate; however, age was used as the experience metric for penguins, as opposed to a proven track record of previous reproductive success (Borecki et al., 2024). The fact that breeding experience did not enhance fertilization in ‘Alalā is consistent with the slow rate of improvement in reproductive output for this CBP (Flanagan et al., 2023). Animal care practitioners often may work on the premise that birds will improve through learning and experience, which may become an obstacle to trialing other management interventions to achieve desired outcomes. In the case of the ‘Alalā, we will need to focus on other factors that may improve egg fertility, such as mate compatibility (Flanagan et al., 2024b), social environment (Flanagan et al., 2020, 2025), and enclosure characteristics (Flanagan et al., 2024a).

By contrast, we found that experience did influence incubation behavior, as experienced females were more likely to incubate eggs for 22 days compared to inexperienced females. Parental incubation increases survival and fitness of ‘Alalā compared to individuals that were incubated and hatched in artificial incubators (Flanagan et al., 2021; Hoeck et al., 2015), underscoring the importance of promoting parental incubation behavior. This is a positive result, and therefore we can expect the number of experienced females to increase over time. Research to better understand the role of parental experience on incubation behaviors in CBPs is lacking, but, in the wild, more experienced females exhibit incubation behaviors that are superior to those of their inexperienced counterparts (Williams et al., 2020). Typically warmer temperatures are associated with better nest outcomes, such as greater hatching success (Hepp et al., 2006) and fledgling survival (Berntsen and Bech, 2016; Hepp and Kennamer, 2012). Parental experience may be an important determinant of optimal temperature maintenance during incubation. Experienced female hooded warblers (Setophaga citrina) selected nest sites in warmer microclimates and shortened the time spent off their nests during foraging bouts on colder mornings compared to inexperienced females (Williams et al., 2020). While long foraging bouts are unnecessary for ‘Alalā and other birds in human care, learning in captivity may influence a female’s incubation proficiency, including temperature maintenance and egg turning. Future work in the ‘Alalā CBP could deploy sensors to compare nest temperatures and turning rates between experienced and inexperienced females to better understand how experience shapes incubation behavior. However, there may be a limit to a female’s ability to maintain egg temperatures in captivity, due to the inherent lack of abundance and diversity of nest site microclimates in an aviary setting. It would also be valuable to better understand how male ‘Alalā interact with females at the nest, which could have consequences for incubation. For example, some males tend to displace incubating females from the nest or otherwise interfere with incubation (personal observation).

Future investigations that simultaneously explore behavioral compatibility (Alverson et al., 2023; Spoon et al., 2006), genetics and genomics (Hoeck et al., 2015; Kyriazis et al., 2025; Sutton et al., 2018), and experience (Lv et al., 2016; Peralta-Sánchez et al., 2020; Pitera et al., 2021), could provide a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that drive variation in breeding outcomes. Moreover, we were unable to meaningfully assess the impact of previous breeding experience on nestling rearing and survival due to sample size limitations (too few data to compare Novice to Expert breeders), although, we acknowledge that exploring post-hatch outcomes would yield valuable insights into the potential benefits of experience on later stages of the reproductive cycle.

This study is part of a broader effort to uncover the husbandry factors that govern successful reproduction in the ‘Alalā conservation breeding program while waiting to achieve the primary goal of releasing individuals to the wild. With a series of retrospective studies, we have examined the role that genetics (Flanagan et al., 2021; Hoeck et al., 2015), captive housing and social management arrangements (Flanagan et al., 2025, 2020), personality composition of pairs (Flanagan et al., 2024b), pair duration (Barrett et al., 2024), and nest quality (Mason et al., 2024) play in reproductive outcomes. Each of these studies moves us a step closer to zeroing in on the most important drivers of reproductive success, although to date few of these variables have yielded large statistical effect sizes, and have been characterized by a substantial amount of statistical noise. Rather than a smoking gun or a silver bullet, we find our research program better characterized as an aggregation of marginal gains, with each new study providing real but small incremental improvements in our ability to manage the species for successful reproduction. The present study adds to this knowledge, allowing practitioners to better gauge which pairs will be successful, and underscoring the importance of providing opportunities for learning, at least for some phases of the reproductive cycle. Specifically, our study suggests that birds with experience are more likely to succeed reproductively than inexperienced birds of various ages. Thus, whenever possible, we recommend that practitioners endeavor to pair inexperienced birds with experienced partners to increase the probability of reproductive success. Making pair selection decisions based on the birds’ breeding experience has the important advantage of being relatively straightforward and easy to implement, as the experience of all individual birds in the ‘Alalā CBP (and presumably other CBPs) is known. Moreover, our results suggest that providing captive birds with every opportunity to engage in breeding behaviors provides them with the experience needed to attain reproductive success, which also has inherent benefits to animal welfare. Allowing animals to express and develop normal behavior patterns prior to release in the wild is vital to the ultimate goal of post-release success (Shier, 2016) and the ‘Alalā CBP has developed a suite of husbandry interventions to promote species-specific behaviors, such as foraging, antipredator, and reproductive behavior to facilitate post-release survival and reproduction (Flanagan et al., 2023; Greggor et al., 2021, 2018; Sabol et al., 2022). More broadly, our study models an approach for quantitatively evaluating the effect of experience on reproduction in a socially monogamous avian species. In addition, our study showcases the value of leveraging routinely collected CBP data to facilitate evidence-based decisions that will help optimize the conservation value of a CBP by expediting the process to identify and implement interventions that will enhance reproductive outcomes and support population growth.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this study are available upon reasonable request. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee as part of the ongoing ‘Alalā conservation breeding program. ‘Alalā conservation breeding is presently conducted under U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service permit ES060179-7, State of Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources permit WL21-08, and San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance IACUC 22-011. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. RS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Marisla Foundation, Dr. and Mrs. Richard Robbins representing the Max and Yetta Karasik Family Foundation, and anonymous donors provided financial support to conduct studies to improve conservation breeding outcomes. Care of ‘Alalā was conducted with financial support by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, State of Hawai’i Division of Forestry and Wildlife, anonymous donors, and San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and its funding sources. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government, or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation or its funding sources.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere appreciation for current and former ‘Alalā conservation breeding program team members, who contributed to the long-term datasets utilized in this study. We would also like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, which helped to improve our manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

RS declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2025.1671345/full#supplementary-material

References

Alverson D. P., Martin M. S., Hebebrand C. T., Greggor A. L., Masuda B., and Swaisgood R. R. (2023). Designing a mate choice program: Tactics trialed and lessons learned with the critically endangered honeycreeper, ‘akikiki (Oreomystis bairdi). Conserv. Sci. Pract. doi: 10.1111/csp2.12923

Asa C. S., Traylor-Holzer K., and Lacy R. C. (2011). Can conservation-breeding programmes be improved by incorporating mate choice? Int. Zoo Yearb. 45, 203–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1090.2010.00123.x

Assersohn K., Marshall A. F., Morland F., Brekke P., and Hemmings N. (2021). Why do eggs fail? Causes of hatching failure in threatened populations and consequences for conservation. Anim. Conserv. 24, 540–551. doi: 10.1111/acv.12674

Bailey I. E., Morgan K. V., Bertin M., Meddle S. L., and Healy S. D. (2014). Physical cognition: birds learn the structural efficacy of nest material. Proc. R. Soc B Biol. Sci. 281, 20133225. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.3225

Banko P. C., Ball D. L., and Banko W. E. (2002). Hawaiian crow (Corvus hawaiiensis). Birds North Am. doi: 10.2173/bna.648

Banko P. C. and Banko W. E. (1980). History of Endemic Hawaiian Birds. Part I Population Histories-Species Accounts (Honolulu, HI: Forest Birds: Hawaiian Raven/Crow ('Alalā).

Barrett L. P., Flanagan A. M., Masuda B., and Swaisgood R. R. (2024). The influence of pair duration on reproductive success in the monogamous ‘Alalā (Hawaiian crow, Corvus hawaiiensis). Front. Conserv. Sci. 5. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2024.1303239

Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., and Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Software 67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Berntsen H. H. and Bech C. (2016). Incubation temperature influences survival in a small passerine bird. J. Avian Biol. 47, 141–145. doi: 10.1111/jav.00688

Bolam F. C., Mair L., Angelico M., Brooks T. M., Burgman M., Hermes C., et al. (2021). How many bird and mammal extinctions has recent conservation action prevented? Conserv. Lett. 14, 1–11. doi: 10.1111/conl.12762

Bond M. and Watts E. (1997). “Recommendations for infant social environment,” in Orangutan Species Survival Plan Husbandry Manual. Ed. Sodaro C. (Brookfield Zoo, Chicago: Chicago Zoological Society), 77–78.

Borecki P., Rosenberger J., Mucha A., and Partyka A. (2024). Breeding behavior analysis in a large captive colony of African penguins (Spheniscus demersus) and its implications for population management and conservation. Sci. Rep. 14, 3589. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-54105-w

Breen A. J., Guillette L. M., and Healy S. D. (2016). What can nest-building birds teach us? Comp. Cogn. Behav. Rev. 11, 83–102. doi: 10.3819/ccbr.2016.110005

Christensen R. H. B. (2018). ordinal - Regression Models for Ordinal Data (R package version). Available online at: http://www.cran.r-project.org/package=ordinal/ (accessed October 14, 2025).

Clark F. E., Greggor A. L., Montgomery S. H., and Plotnik J. M. (2023). The endangered brain: actively preserving ex-situ animal behaviour and cognition will benefit in-situ conservation. R. Soc Open Sci. doi: 10.1098/rsos.230707

Collias E. C. and Collias N. E. (1964). The development of nest-building behavior in a weaverbird. Auk 81, 42–52. doi: 10.2307/4082609

Conde D. A., Flesness N., Colchero F., Jones O. R., and Scheuerlein A. (2011). An emerging role of zoos to conserve biodiversity. Science 80-, 1390–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1200674

Crates R., Stojanovic D., and Heinsohn R. (2023). The phenotypic costs of captivity. Biol. Rev. 98, 434–449. doi: 10.1111/brv.12913

Digby A., Eason D., Catalina A., Lierz M., Galla S., Urban L., et al. (2023). Hidden impacts of conservation management on fertility of the critically endangered kākāpō. PeerJ 11, e14675. doi: 10.7717/peerj.14675

Dirzo R., Ceballos G., and Ehrlich P. R. (2022). Circling the drain: the extinction crisis and the future of humanity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc B Biol. Sci. 377, 0378. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2021.0378

Dubey A., Saxena S., Mishra G., and Omkar (2018). Mating experience influences mate choice and reproductive output in an aphidophagous ladybird, Menochilus sexmaculatus. Anim. Biol. 68, 247–263. doi: 10.1163/15707563-17000128

Dukas R. (2019). Animal expertise: mechanisms, ecology and evolution. Anim. Behav. 147, 199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2018.05.010

Flanagan A. M., Masuda B., Bailey H., and Swaisgood R. R. (2025). Don’t stand so close: social crowding negatively impacts reproduction in an endangered, territorial hawaiian bird. Anim. Conserv. 28, 1–11. doi: 10.1111/acv.13017

Flanagan A. M., Masuda B., Grabar K., Barrett L. P., and Swaisgood R. R. (2024a). An enclosure quality ranking framework for terrestrial animals in captivity. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 278, 106378. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2024.106378

Flanagan A. M., Masuda B., Grueber C. E., and Sutton J. T. (2021). Moving from trends to benchmarks by using regression tree analysis to find inbreeding thresholds in a critically endangered bird. Conserv. Biol. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13650

Flanagan A. M., Masuda B., Komarczyk L., Kuhar A., Farabaugh S., and Swaisgood R. R. (2023). Adapting conservation breeding techniques using a data-driven approach to restore the ‘Alalā (Hawaiian crow, Corvus hawaiiensis ). Zoo Biol. 42, 834–839. doi: 10.1002/zoo.21794

Flanagan A. M., Petelle M. B., Greggor A. L., Masuda B., and Swaisgood R. R. (2024b). Evaluating the role of caretaker-rated personality traits for reproductive outcomes in a highly endangered Hawaiian corvid. Anim. Conserv. 27, 554–565. doi: 10.1111/acv.12931

Flanagan A. M., Rutz C., Farabaugh S., Greggor A. L., Masuda B., and Swaisgood R. R. (2020). Inter-aviary distance and visual access influence conservation breeding outcomes in a territorial, endangered bird. Biol. Conserv. 242, 108429. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108429

Fox J. and Weisburg S. (2019). car: An R Companion to Applied Regression (Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.).

Gelman A. and Hill J. (2007). Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Model (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press).

Gelman A. and Su Y. (2018). arm: Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models (R package version 1.10-1). Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=arm (accessed October 14, 2025).

Greggor A. L., Masuda B., Gaudioso-Levita J. M., Nelson J. T., White T. H., Shier D. M., et al. (2021). Pre-release training, predator interactions and evidence for persistence of anti-predator behavior in reintroduced `alalā, Hawaiian crow. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 28, e01658. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01658

Greggor A. L., Masuda B., Sheppard J., Flanagan A. M., Nelson J., Berry L., et al. (2025). Balancing evidence and reducing uncertainty in the evaluation of reintroduction outcomes in A’lalā, the Hawaiian crow. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 62, e03673. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2025.e03673

Greggor A. L., Vicino G. A., Swaisgood R. R., Fidgett A., Brenner D., Kinney M. E., et al. (2018). Animal welfare in conservation breeding: applications and challenges. Front. Vet. Sci. 5. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00323

Harrison X. A., Donaldson L., Correa-Cano M. E., Evans J., Fisher D. N., Goodwin C. E. D., et al. (2018). A brief introduction to mixed effects modelling and multi-model inference in ecology. PeerJ 6, e4794. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4794

Hartig F. (2022). DHARMa - Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level / Mixed) (R package version 0.4.6). Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DHARMa (accessed October 14, 2025).

Healy S. D., Tello-Ramos M. C., and Hébert M. (2023). Bird nest building: visions for the future. Philos. Trans. R. Soc B Biol. Sci. 378, 0–3. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0157

Hedrick P. W., Hoeck P. E. A., Fleischer R. C., Farabaugh S., and Masuda B. M. (2016). The influence of captive breeding management on founder representation and inbreeding in the ‘Alalā, the Hawaiian crow. Conserv. Genet. 17, 369–378. doi: 10.1007/s10592-015-0788-z

Hepp G. R. and Kennamer R. A. (2012). Warm is better: incubation temperature influences apparent survival and recruitment of wood ducks (Aix sponsa). PloS One 7, e47777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047777

Hepp G. R., Kennamer R. A., and Johnson M. H. (2006). Maternal effects in Wood Ducks: incubation temperature influences incubation period and neonate phenotype. Funct. Ecol. 20, 308–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01108.x

Hoeck P. E. A., Wolak M. E., Switzer R. A., Kuehler C. M., and Lieberman A. A. (2015). Effects of inbreeding and parental incubation on captive breeding success in Hawaiian crows. Biol. Conserv. 184, 357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.02.011

Hurley L. L., Rowe M., and Griffith S. C. (2020). Reproductive coordination breeds success: the importance of the partnership in avian sperm biology. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 74, 3. doi: 10.1007/s00265-019-2782-9

Ibáñez-álamo J. D., Magrath R. D., Oteyza J. C., Chalfoun A. D., Haff T. M., Schmidt K. A., et al. (2015). Nest predation research: Recent findings and future perspectives. J. Ornithol. 156, S247–S262. doi: 10.1007/s10336-015-1207-4

Ihle M., Kempenaers B., and Forstmeier W. (2015). Fitness benefits of mate choice for compatibility in a socially monogamous species. PloS Biol. 13, e1002248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002248

Kyriazis C. C., Venkatraman M., Masuda B., Steiner C. C., Cassin-Sackett L., Crampton L. H., et al. (2025). Population genomics of recovery and extinction in Hawaiian honeycreepers. Curr. Biol. 35, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.04.078

Loukola O. J., Laaksonen T., Seppänen J.-T., and Forsman J. T. (2014). Active hiding of social information from information-parasites. BMC Evol. Biol. 14, 32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-32

Lv L., Komdeur J., Li J., Scheiber I. B. R., and Zhang Z. (2016). Breeding experience, but not mate retention, determines the breeding performance in a passerine bird. Behav. Ecol. 27, 1255–1262. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arw046

Martin-Wintle M. S., Shepherdson D., Zhang G., Huang Y., Luo B., and Swaisgood R. R. (2017). Do opposites attract? Effects of personality matching in breeding pairs of captive giant pandas on reproductive success. Biol. Conserv. 207, 27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.01.010

Martin-Wintle M. S., Wintle N. J. P., Díez-León M., Swaisgood R. R., and Asa C. S. (2019). Improving the sustainability of ex situ populations with mate choice. Zoo Biol. 38, 119–132. doi: 10.1002/zoo.21450

Mason L. L. K., Masuda B., Swaisgood R. R., and Flanagan A. M. (2024). Nest quality predicts the probability of egg loss in the critically endangered ‘Alalā (Corvus hawaiiensis). Zoo Biol. doi: 10.1002/zoo.21849

Munson A. A., Jones C., Schraft H., and Sih A. (2020). You’re just my type: mate choice and behavioral types. Trends Ecol. Evol. 35, 823–833. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2020.04.010

Muth F. and Healy S. D. (2014). Zebra finches select nest material appropriate for a building task. Anim. Behav. 90, 237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.02.008

Peralta-Sánchez J. M., Colmenero J., Redondo-Sánchez S., Ontanilla J., and Soler M. (2020). Females are more determinant than males in reproductive performance in the house sparrow Passer domesticus. J. Avian Biol. 51, e02240. doi: 10.1111/jav.02240

Pitera A. M., Branch C. L., Sonnenberg B. R., Benedict L. M., Kozlovsky D. Y., and Pravosudov V. V. (2021). Reproduction is affected by individual breeding experience but not pair longevity in a socially monogamous bird. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 75, 101. doi: 10.1007/s00265-021-03042-z

Price E. E. and Stoinski T. S. (2007). Group size: Determinants in the wild and implications for the captive housing of wild mammals in zoos. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 103, 255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2006.05.021

R Core Team (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Version 4.3.1 (“Beagle Scouts”) (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed October 14, 2025).

Ruiz-Miranda C. R., Vilchis L. I., and Swaisgood R. R. (2020). Exit strategies for wildlife conservation: why they are rare and why every institution needs one. Front. Ecol. Environ. 18, 203–210. doi: 10.1002/fee.2163

Sabol A. C., Greggor A. L., Masuda B., and Swaisgood R. R. (2022). Testing the maintenance of natural responses to survival-relevant calls in the conservation breeding population of a critically endangered corvid (Corvus hawaiiensis). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 76, 21. doi: 10.1007/s00265-022-03130-8

Shier D. M. (2016). “Manipulating animal behavior to ensure reintroduction success,” in Conservation Behavior: Applying Behavioral Ecology to Wildlife Conservation and Management. Eds. Berger-Tal O. and Saltz D. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge), 275–304.

Snyder N. F. R., Derrickson S. R., Beissinger S. R., Wiley J. W., Smith T. B., Toone W. D., et al. (1996). Limitations of captive breeding in endangered species recovery. Conserv. Biol. 10, 338–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10020338.x

Spoon T. R., Millam J. R., and Owings D. H. (2006). The importance of mate behavioural compatibility in parenting and reproductive success by cockatiels, Nymphicus hollandicus. Anim. Behav. 71, 315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.03.034

Sutton J. T., Helmkampf M., Steiner C. C., Bellinger M. R., Korlach J., Hall R., et al. (2018). A high-quality, long-read De Novo genome assembly to aid conservation of Hawaii’s last remaining crow species. Genes (Basel). 9, 393. doi: 10.3390/genes9080393

Swaisgood R. R. and Schulte B. A. (2010). “Applying knowledge of mammalian social organization, mating systems and communication to management,” in Wild Mammals in Captivity. Eds. Kleiman D. G., Thompson K. B., and Baer C. K. (University of Chicago Press, Chicago).

Switzer P. V. (1993). Site fidelity in predictable and unpredictable habitats. Evol. Ecol. 7, 533–555. doi: 10.1007/BF01237820

Walsh P. T., Hansell M., Borello W. D., and Healy S. D. (2010). Repeatability of nest morphology in African weaver birds. Biol. Lett. 6, 149–151. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0664

Keywords: animal behavior, animal cognition/learning, captive propagation, aviculture, endangered birds

Citation: Flanagan AM, Masuda B and Swaisgood RR (2025) Breeding experience improves reproductive outcomes in an avian conservation breeding program. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6:1671345. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1671345

Received: 22 July 2025; Accepted: 31 October 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

David R Breininger, University of Central Florida, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Flanagan, Masuda and Swaisgood. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: A. M. Flanagan, YWxmbGFuYWdhbkBzZHp3YS5vcmc=

A. M. Flanagan

A. M. Flanagan B. Masuda

B. Masuda R. R. Swaisgood

R. R. Swaisgood