- 1Department of Environmental Science, Natural Resources Faculty, University of Tehran, Karaj, Iran

- 2Department of Environmental Science, Natural Resources Faculty, Lorestan University, Khorramabad, Iran

- 3Pars Wildlife Guardians Foundation, Shiraz, Iran

- 4School of Forestry, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, United States

- 5Department of Forest Engineering, Forest Management Planning and Terrestrial Measurements, Faculty of Silviculture and Forest Engineering, Transilvania University of Brasov, Brasov, Romania

The Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor), the largest felid in the Middle East, is an endangered subspecies persisting in fragmented mountainous habitats across Iran, where it faces escalating threats from habitat degradation, poaching, and human–wildlife conflict. Bamu National Park (BNP), located in the southern Zagros Mountains, serves as one of the species’ last strongholds and ecological hotspot in southern Iran, yet its habitat suitability remains poorly quantified. In this study, we used a maximum entropy (MaxEnt) model to identify suitable habitat and the key environmental and anthropogenic drivers shaping the spatial distribution of Persian leopards in BNP. Presence data were derived from 42 verified leopard occurrence records collected between 2015 and 2017. Twelve predictor variables were retained out of an initial set of fifteen after multicollinearity screening, selected based on ecological theory, previous research, and expert consultation. These included topographic factors (slope, aspect, ruggedness), climatic variables (mean annual temperature and precipitation), vegetation and rangeland types, prey availability (Ovis orientalis), and human disturbance (proximity to water troughs, ranger stations, roads, and the oil refinery plant). The MaxEnt model exhibited excellent predictive performance (mean AUC = 0.959; TSS = 0.84; OR = 0.06). Distance to artificial water troughs was the most influential variable, contributing over 50% to the model’s explanatory power, followed by vegetation type and rangeland classification. Terrain ruggedness, prey availability, slope, and aspect were also important, confirming the Persian leopard’s preference for rugged, shrub-dominated landscapes with reliable prey resources. These results highlight clear conservation priorities within BNP, including the protection and careful management of core habitats surrounding anthropogenic water sources, restricting road expansion in high-suitability zones, and managing rangeland and vegetation types that support key prey populations. Beyond BNP, this study provides a replicable modeling framework to guide conservation of large carnivores in other mountainous and fragmented landscapes where apex predators face similar ecological and anthropogenic constraints.

1 Introduction

Habitat loss and fragmentation are among the leading drivers of biodiversity decline worldwide, threatening the persistence of wide-ranging carnivores that require large, connected landscapes for survival (Yuan et al., 2024). The Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor), the largest subspecies of leopard, is listed as endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List (Sanei et al., 2020; Ghoddousi and Khorozyan, 2024; Moradi et al., 2024). Once widespread across West and Central Asia, its population has undergone a dramatic decline due to habitat fragmentation, illegal hunting and poaching for pelts and other body parts (e.g., bones, claws, teeth, and whiskers) traded in regional and international markets (Parchizadeh and Adibi, 2019), retaliatory killings, and human–wildlife conflict arising from livestock depredation (Soofi et al., 2019; Khorozyan et al., 2020). The depletion of native ungulate prey, including large and medium-sized herbivores, has further exacerbated conflict by forcing leopards to hunt domestic animals and even livestock guarding dogs. This prey depletion has intensified these pressures (Shams et al., 2019; Moradi et al., 2024). In Iran, which harbors the core population of this subspecies, rapid habitat degradation, prey depletion, and expanding human activities have severely fragmented the leopard’s range, increasing local extirpation risk (Sanei et al., 2020; Jamali et al., 2024). Because these threats are spatially structured, understanding where suitable habitats persist and how they connect across human-modified landscapes is critical for long-term species conservation (Morrison and Mathewson, 2015; Almasieh et al., 2019).

Habitat suitability models (HSMs) provide a powerful framework to address this challenge by translating ecological relationships into spatially explicit conservation priorities. They produce decision-ready, map-based predictions of suitable areas, enabling managers to identify core habitats, safeguard movement corridors, and anticipate zones of potential human–wildlife overlap (Ahmadi et al., 2020; Mwaniki et al., 2025). By integrating environmental and anthropogenic variables, HSMs support evidence-based decisions on habitat protection, restoration, and the potential reintroduction of species into suitable landscapes (Jamali et al., 2024; Serva et al., 2025). For threatened felids, HSMs offer a cost-effective tool to target conservation where it is most likely to succeed (Lamichhane et al., 2024; Roshani et al., 2024). In recent years, such modeling approaches have increasingly been used to understand Persian leopard distribution, generating a growing body of knowledge on its ecological preferences and threats.

Across Iran, these studies consistently demonstrate that Persian leopard habitat suitability is shaped by a combination of topographic, climatic, and anthropogenic factors, including slope, ruggedness, water availability, vegetation structure, and human disturbance (Ebrahimi et al., 2017; Kaboodvandpour et al., 2021; Moradi et al., 2022; Jamali et al., 2024; Tavakoli et al., 2024). Rather than detailing province-specific findings, these results collectively reveal a recurring pattern: suitable habitats are patchy, rugged, and increasingly fragmented by infrastructure and settlement. However, despite this growing understanding at regional scales, fine-resolution assessments remain scarce for some of Iran’s most important leopard refuges.

One of such area is Bamu National Park (BNP), a major stronghold in southern Iran, have not yet been subject to detailed, spatially explicit habitat suitability assessments. BNP, designated as an ecological hotspot, supports one of the most significant remaining populations of the Persian leopard (Ghoddousi et al., 2008, 2010; Ahmed and Majeed, 2023). BNP’s rugged mountainous terrain, diverse vegetation mosaics, and relatively high prey densities make it a critical stronghold for the species. However, it is increasingly threatened by habitat fragmentation, overgrazing, infrastructure development, and human–wildlife conflict. Quantifying habitat suitability and the relative influence of ecological versus anthropogenic drivers within BNP is therefore essential to guide conservation priorities, identify conflict-prone areas, and sustain viable Persian leopard populations.

The Persian leopard is distributed across mountainous habitats in the Caucasus, Southwest Asia, and parts of Central Asia, spanning 11 countries (Karami et al., 2016). Iran harbors the largest remaining population and the most extensive contiguous habitat of this subspecies. The Persian leopard has become the apex felid following the regional extinction of the Asiatic lion (P. leo persica) and the Caspian tiger (P. tigris virgata) over the past seven decades (Jamali et al., 2024). However, during the last 25 years, the Persian leopard has been extirpated from many parts of its historical range, and populations elsewhere have sharply declined due to human–wildlife conflict, road mortality, prey depletion, and poaching (Soofi et al., 2022; Jamali et al., 2024; Almasieh and Mohammadi, 2025). Understanding the ecological and anthropogenic factors that drive its habitat use within strongholds like BNP is thus fundamental to regional conservation planning. To address this gap, the present study applies the maximum entropy (MaxEnt) model to predict habitat suitability for the Persian leopard in BNP, integrating topographic, climatic, ecological, and anthropogenic variables. Specifically, we aim to: (1) identify the spatial distribution of suitable Persian leopard habitats, (2) quantify the relative importance of key environmental predictors, and (3) provide spatially explicit recommendations for conservation management. The results aim to inform evidence-based conservation planning, highlight core habitats, and support targeted management interventions to mitigate human–leopard conflict in this nationally important refuge.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

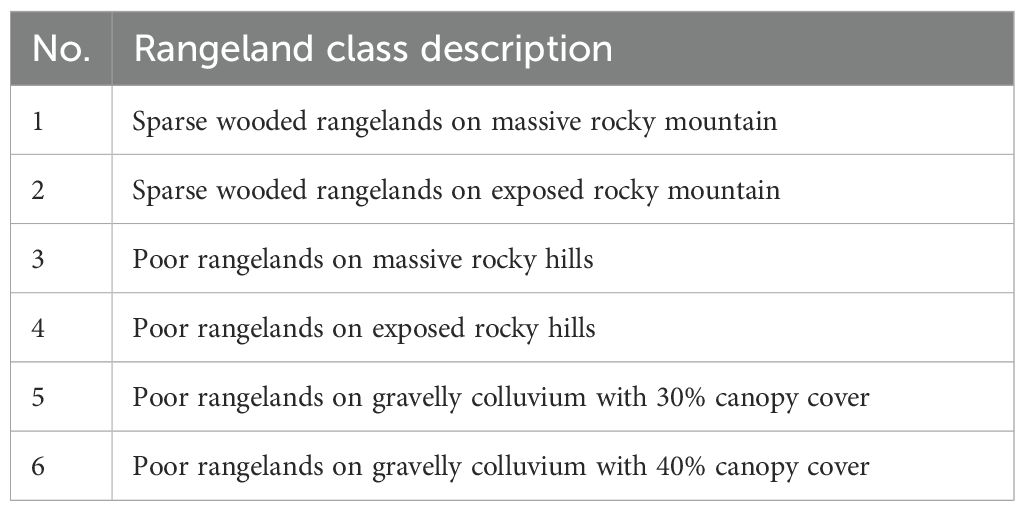

BNP, located approximately 10 km northeast of Shiraz in Fars Province, southern Iran, covers an area of 48,594 ha. Its geographic extent lies between 29°35′12″ to 29°36′24″ N latitude and 52°29′37″ to 52°54′12″ E longitude. Situated within the Zagros Mountain range, BNP features a rugged topography, with its highest elevation at Mount Bamu (2,660 m above sea level) and the lowest elevations ranging between 1,500 in the foothills to 2,660 m at Mount Bam, the park’s highest peak. The area experiences a temperate semi-arid continental climate, with an average annual precipitation of 210 mm and a mean annual temperature of 16°C (Ranjbar et al., 2016). The area vegetation is dominated by dry shrubland communities, primarily composed of almond species (Amygdalus spp.) and thorny shrubs (Crataegus spp.), interspersed with patches of steppe vegetation. BNP harbors a rich assemblage of wildlife, including goitered gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa), wild sheep (Ovis orientalis), wild goat (Capra aegagrus), and the endangered Persian leopard (P. pardus saxicolor) (Ghoddousi et al., 2008). This ecological diversity, coupled with the park’s relatively high prey densities and rugged terrain, makes it a critical refuge for the Persian leopard in southern Iran. Historically, BNP was first designated as a protected area in 1959, expanded in 1971 to 100,000 ha, and later reclassified as a national park in 1974. Due to increasing human settlement and land-use pressure near Shiraz, the park’s area was gradually reduced to its current extent of 48,594 ha (Hushmand et al., 2022). Figure 1 illustrates the geographical location of the study area.

Figure 1. Geographical location of Bamu National Park (BNP), southern Iran. The park, located approximately 10 km northeast of Shiraz in Fars Province, covers 48,594 ha within the southern Zagros Mountains (1,500–2,660 m a.s.l.). The map shows Persian leopard presence points (green circles) and main roads across the park.

2.2 Methodology

2.2.1 Determining species presence points

Previous studies suggest that at least 30 occurrence points are required to achieve reliable model performance in MaxEnt (Hemami et al., 2015; Hosseini et al., 2025). To meet this requirement, Persian leopard presence records were compiled in BNP between 2015 to 2017, combining confirmed historical detections (2015–2016) with intensive field surveys conducted in all seasons of 2017 for validation and spatial confirmation. Occurrence points were identified using multiple sources: (i) direct visual observations reported by park rangers and visitors, (ii) confirmed camera-trap photographs, and (iii) indirect evidence such as scat, tracks, and scratch marks. The geographic coordinates of each confirmed presence were recorded using GPS during the 2017 field campaigns. To ensure data reliability, all 42 occurrence records were cross-validated using ranger patrol logs, camera-trap timestamps, and GPS coordinates. Records collected within 500 m or during the same 24-hour period were screened to remove spatial or temporal duplication. Duplicate records within the same 100 × 100 m grid cell (matching the spatial resolution of the environmental layers) were also excluded. To reduce spatial sampling bias, the dataset was spatially thinned using the spThin package in R (Aiello-Lammens et al., 2015), retaining only one presence record per 1 km radius to ensure even spatial representation. Each verified point was georeferenced in ArcGIS with field-validated coordinates. The spatial resolution of 100 × 100 m was selected as an optimal scale that balances the positional accuracy of GPS- and camera-derived data (± 30 m) with the ecological grain of leopard habitat use. This resolution minimizes spatial uncertainty while capturing fine-scale environmental heterogeneity relevant to terrain, vegetation, and anthropogenic features (Jacobson et al., 2016; Farhadinia et al., 2018). Additional field information—such as elevation, topographic roughness, proximity to water resources, and presence of other wildlife—was documented for each occurrence site. In total, 42 independent occurrence points were compiled for use in the SDM. To ensure the spatial independence of the dataset, global spatial autocorrelation index Moran’s I (Tiefelsdorf and Boots, 1997) was applied to assess the spatial autocorrelation of occurrence points. Following this quality check, all 42 occurrence points were retained as reliable inputs for the MaxEnt modeling. These data were collected as part of a long-term monitoring program aimed at documenting the Persian leopard’s spatial distribution across all potential habitats in BNP.

2.2.2 Habitat modeling using MaxEnt software

Habitat suitability was modeled using MaxEnt version 3.4.4, which applies the Maximum Entropy principle to predict species distributions based on presence-only data (Phillips et al., 2006). MaxEnt has been widely recognized as one of the most robust SDM approaches, particularly when working with limited presence records (Elith et al., 2011; Comia-Geneta et al., 2024). The software estimates habitat suitability by contrasting environmental conditions at species occurrence locations with those available across the study area, thereby generating a probability surface of suitable habitat. To assess the relative contribution of each environmental predictor, a Jackknife test was performed (Phillips et al., 2006; Baldwin, 2009), allowing the identification of the most influential variables shaping Persian leopard distribution. MaxEnt determines the optimal probability distribution between species occurrence points and predictor variables under the constraint of maximum entropy and generalizes this relationship across the entire study area to produce a continuous habitat suitability map (Ahmadi et al., 2023).

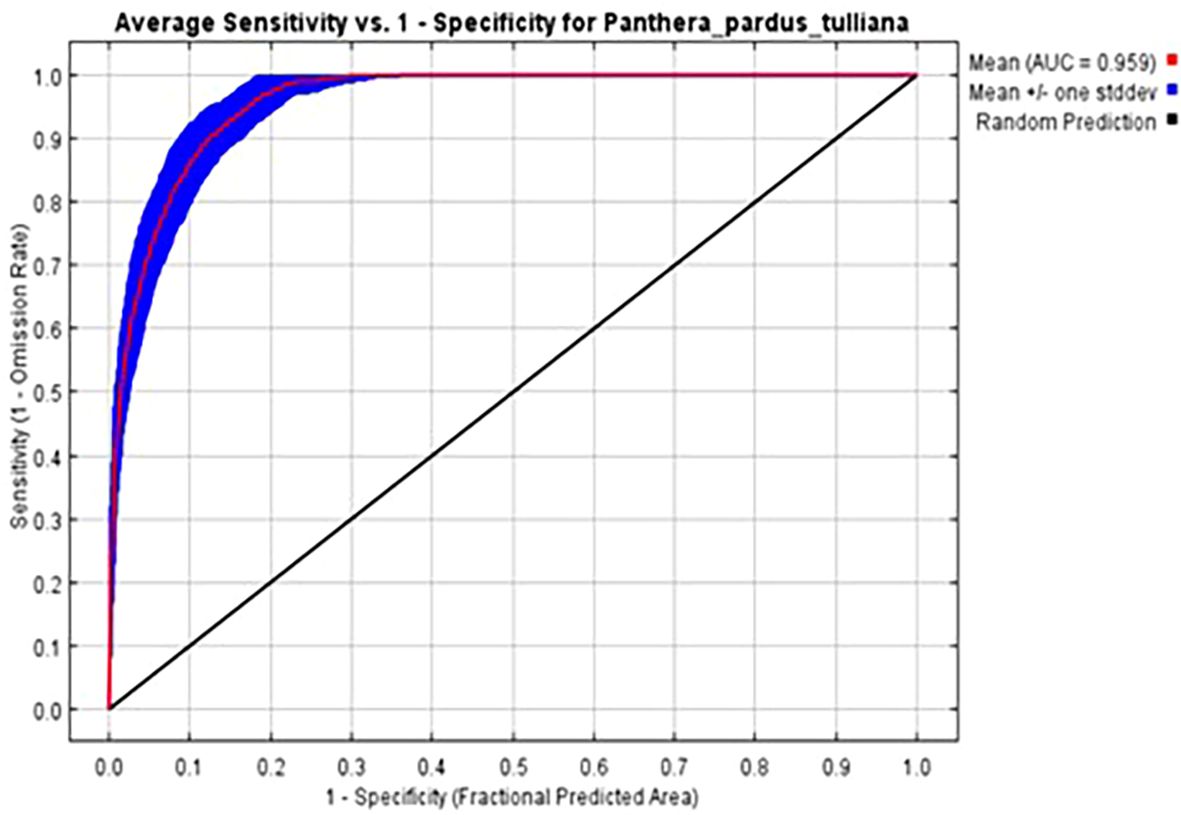

In this study, 70% of the occurrence points were randomly assigned for model training, while the remaining 30% were reserved for independent testing, following common SDM validation procedures (Vesali et al., 2017). Model performance was evaluated using the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) metric (Omidi et al., 2010; Shams et al., 2019). An AUC value of 0.5 indicates random model performance, while values between 0.7–0.8 suggest a good model, 0.8–0.9 indicate excellent performance, and values above 0.9 reflect outstanding predictive capacity (Farhadinia and Akbari, 2007). The final habitat suitability map ranged from 0 (unsuitable) to 1 (highly suitable), where higher values denote greater suitability for the Persian leopard (Karami et al., 2016). Additionally, composite layers of prey species distributions were integrated to calculate distances to key ecological resources, ensuring that both environmental and biotic factors were incorporated into the modeling framework.

2.2.3 Environmental variables

A total of 15 environmental variables were selected for modeling Persian leopard habitat suitability in BNP. The selection was based on ecological theory, findings from previous studies, and consultation with 19 experts, each holding at least a Master of Science degree and possessing an average of 15 years of professional experience in Persian leopard ecology, wildlife management, or conservation biology (Table 1). These variables encompassed topographic features, climatic conditions, vegetation characteristics, prey availability, and anthropogenic disturbance factors, ensuring a comprehensive representation of both environmental and human influences on Persian leopard habitat suitability.

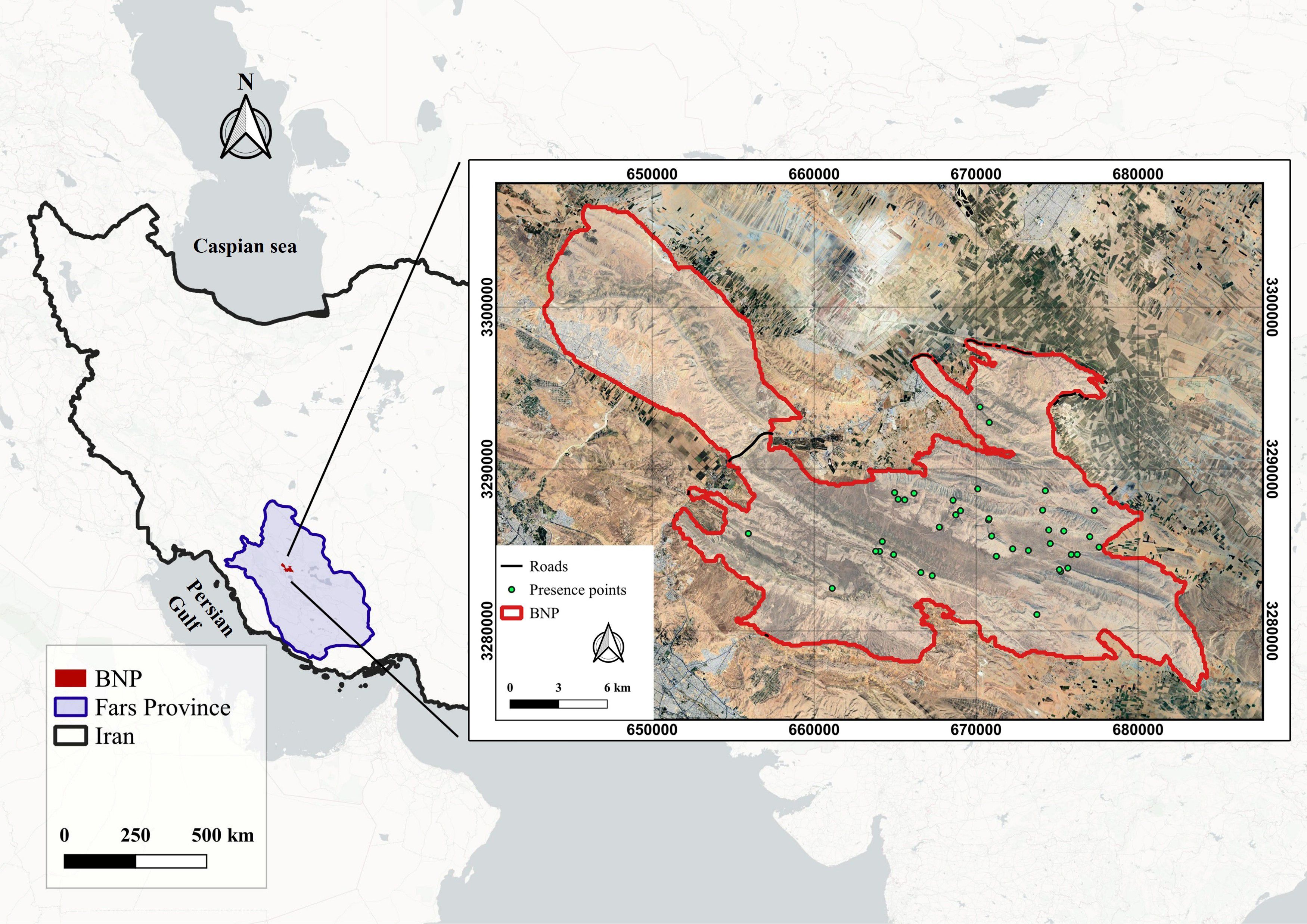

Table 1. Environmental variables used for Persian leopard habitat suitability modeling in Bamu National Park (BNP).

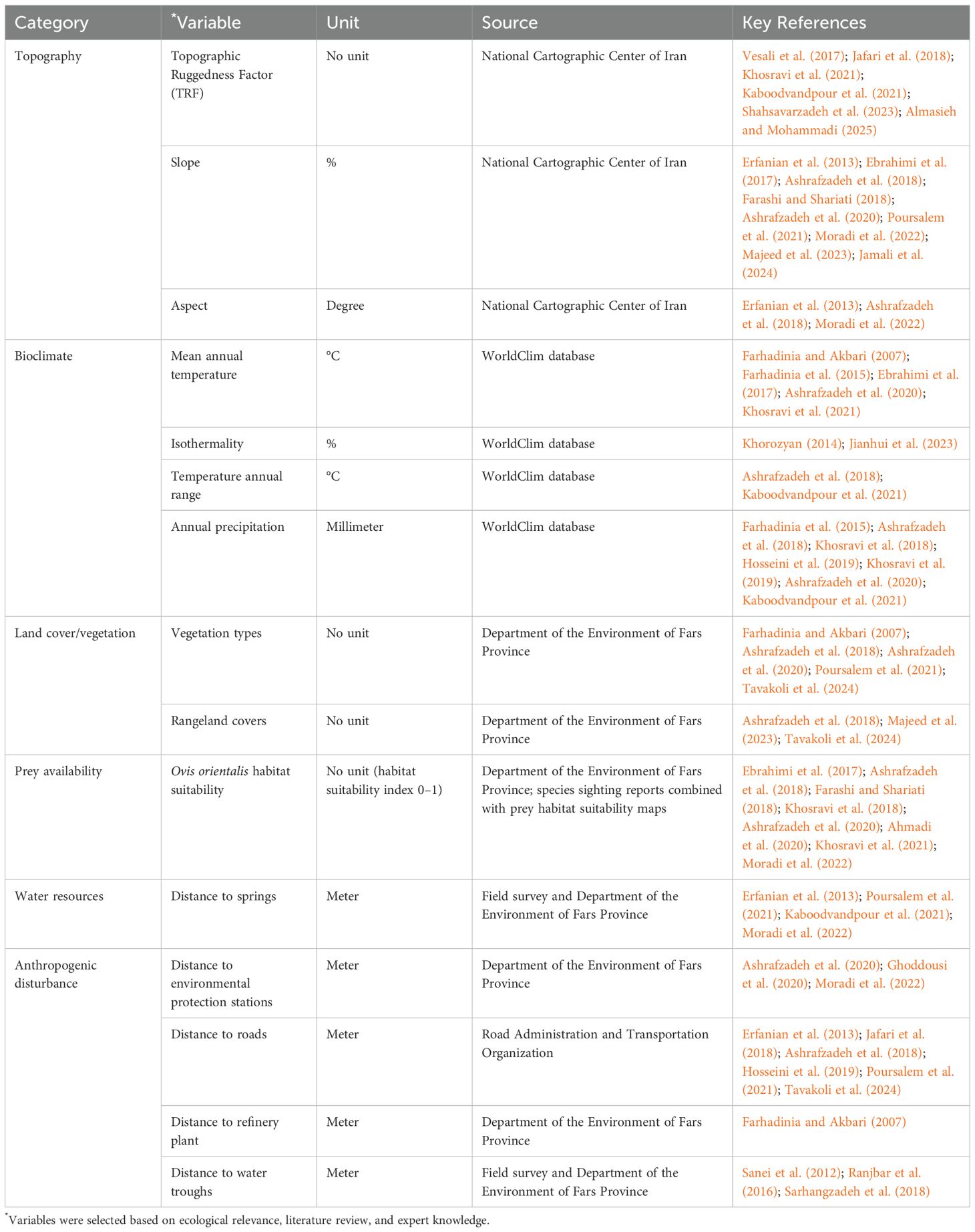

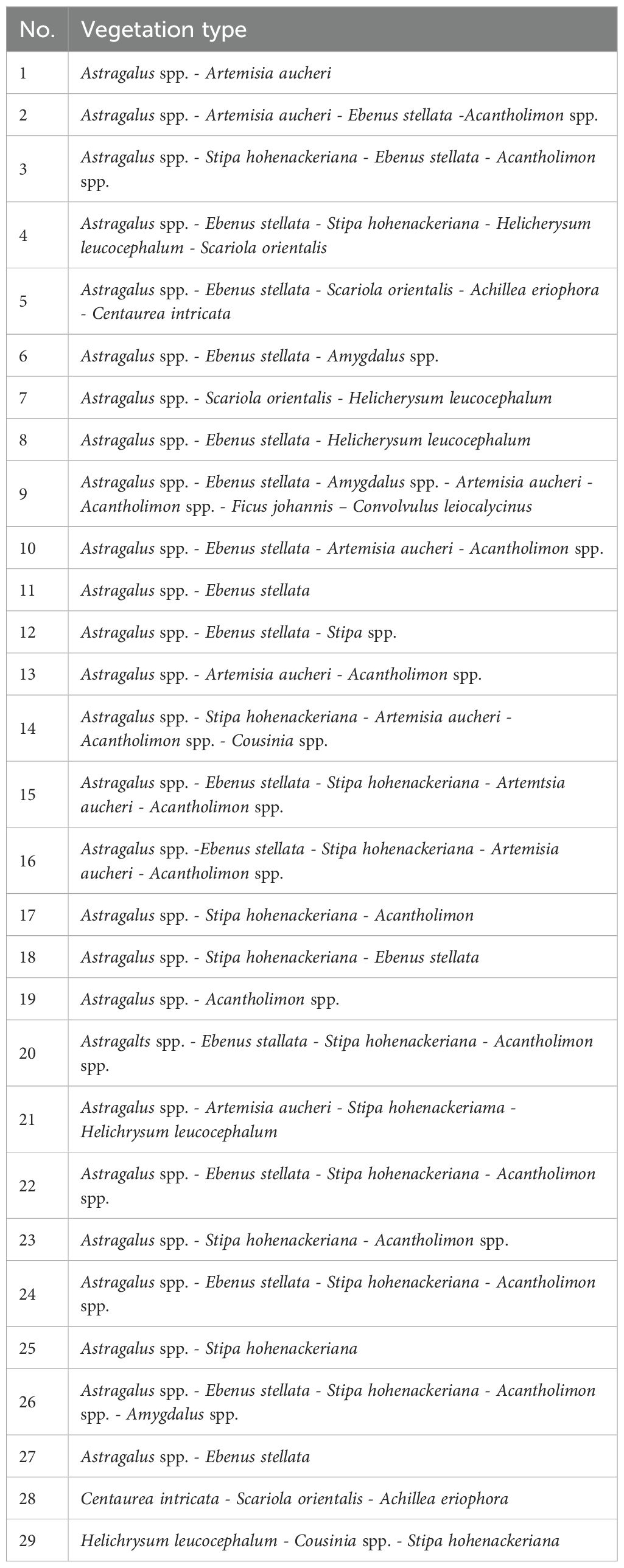

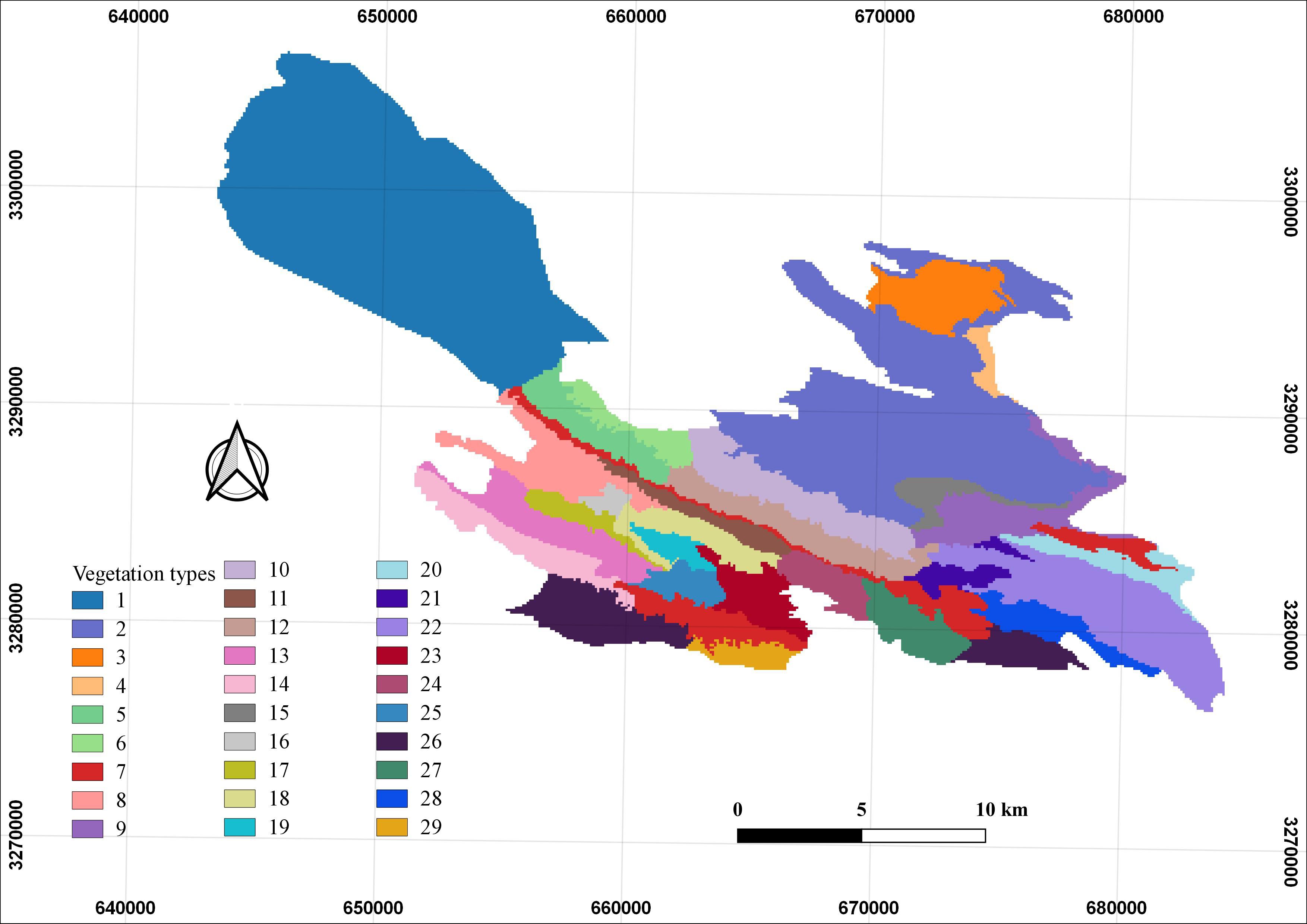

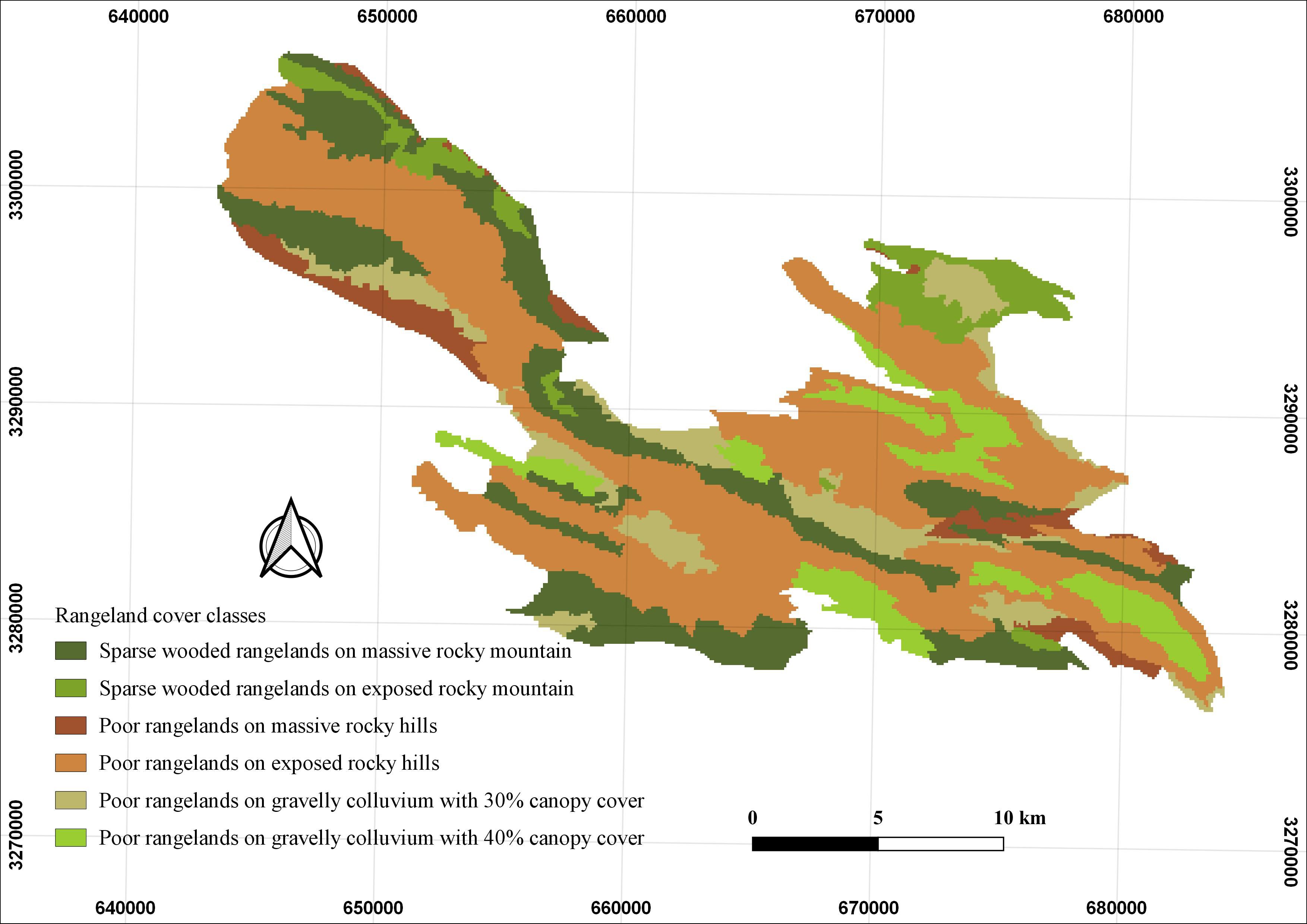

Topographic variables (Table 1), including slope, aspect, and topographic ruggedness factor (TRF), were derived from a 1:50,000 digital elevation model (DEM) provided by the National Cartographic Center of Iran and processed using ArcMap 10.8. Four bioclimatic variables—mean annual temperature (bio1), isothermality (bio3), annual temperature range (bio7), and annual precipitation (bio12)—were obtained from the WorldClim database (Fick, 2017). Land use and land cover were mapped using datasets from the Department of the Environment of Fars Province, based on 2016 satellite imagery, which corresponds closely to the 2015–2017 period of Persian leopard occurrence records. Using the 2016 dataset minimized temporal discrepancies and ensured that land cover conditions were representative of the landscape during the monitoring period. These data identified 28 distinct vegetation types (Table 2, Figure 2) and six rangeland covers (Table 3, Figure 3) within the study area. Although minor local land-use changes may have occurred after 2017 (e.g., expansion of grazing lands or small-scale development), their effect on model performance is likely negligible given the limited extent of such modifications in BNP. Prey availability (Table 1) was represented by a habitat suitability layer for wild sheep (Ovis orientalis), the principal natural prey of the Persian leopard in BNP. Other potential prey species such as wild goat (Capra aegagrus) or goitered gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa) were excluded because consistent spatial data on their distributions were unavailable for the study area. The wild sheep layer was selected due to its broad spatial coverage and ecological representativeness as a key prey species across the park. The layer was constructed by combining field-based sighting records collected by the Department of the Environment of Fars Province between 2015 and 2017 with an independently developed MaxEnt-based prey suitability map using topographic, vegetation, and water proximity variables. The resulting raster layer represented continuous prey suitability values ranging from 0 (unsuitable) to 1 (highly suitable) and was used as a biotic predictor in the leopard habitat model. Locations of springs (natural water sources) and artificial water troughs (anthropogenic sources) were mapped through direct field surveys, while the locations of environmental protection stations, an oil refinery plant, and roads were obtained from the Department of the Environment and Iran’s Road Administration and Transportation Organization. Euclidean distance layers were then generated for all anthropogenic features using ArcMap (Ver. 10.8) to quantify their proximity to Persian leopard presence points.

Table 2. Vegetation types identified in Bamu National Park (BNP) based on dominant species composition.

Figure 2. Vegetation types identified in Bamu National Park (BNP), southern Iran. The map illustrates 29 vegetation types classified based on dominant species composition (see Table 2 for details).

Figure 3. Rangeland cover classes identified in Bamu National Park (BNP), southern Iran. The map illustrates six rangeland classes based on physiographic and canopy characteristics (see Table 3 for descriptions).

2.3 Multicollinearity assessment and model configuration

To address potential multicollinearity among environmental predictors, pairwise Pearson correlation analysis was conducted. Three variable pairs showed high correlation coefficients (r > 0.7): bio1 vs. bio12, bio3 vs. bio7, and distance to environmental protection stations vs. distance to water troughs. To reduce redundancy and ensure statistical independence among variables, bio1, bio7, and distance to environmental protection stations were excluded from the final analysis. All environmental layers were resampled to a spatial resolution of 100 × 100 m and imported into MaxEnt alongside the species occurrence data. Following best practices, 70% of the presence points were randomly selected for model training, while the remaining 30% were used for model testing and validation (Elith et al., 2011). The MaxEnt algorithm was selected because it is well-suited to presence-only data and small sample sizes (Hernandez et al., 2006; Elith et al., 2006; Pearson et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2025). Comparative studies show it often performs favorably or similarly to regression-based (GLM) and machine‐learning (Random Forest) approaches when appropriately tuned (e.g., Luna-Aranguré and Vázquez-Domínguez, 2021; Hosseini et al., 2022); however, algorithm performance ultimately depends on data conditions and modeling context.

We acknowledge that MaxEnt can be sensitive to sampling bias and spatial autocorrelation, which may artificially inflate model accuracy if left uncorrected (Kramer-Schadt et al., 2013; Phillips, 2017). To minimize this potential bias, we applied spatial thinning of occurrence data (1 km radius) and excluded background points overlapping presence locations, ensuring balanced environmental representation across the study area.

The MaxEnt model was configured to run for a maximum of 500 iterations, using 1,000 background points, and was repeated 100 times to ensure robustness and account for variability in predictions (Elith et al., 2011; Merow et al., 2013; Phillips, 2017). The 1,000 background points were randomly generated within the boundary of Bamu National Park to represent the full range of available environmental conditions. Because the occurrence data were collected systematically across the park through a well-distributed monitoring program, restricting background points by survey effort was not necessary. To ensure spatial independence, background points located within grid cells containing presence records were excluded prior to model calibration. Model settings included a regularization multiplier of 1.0 and five feature classes (linear, quadratic, product, threshold, and hinge), following recommendations by Phillips and Dudík (2008) and Merow et al. (2013). These default parameters were retained because they provide a balanced trade-off between model complexity and predictive performance when sample sizes are moderate (Elith et al., 2011). Model convergence was confirmed through preliminary testing of multiple runs with different random seeds, which yielded consistent response patterns. To classify habitat suitability, the 10th percentile training presence threshold was applied to the continuous MaxEnt output. This thresholding method is widely used in presence-only models to minimize overprediction while accounting for potential location uncertainty in a small number of training records (Liu et al., 2005; Pearson et al., 2007). In addition to the AUC, the model’s predictive performance was evaluated using the True Skill Statistic (TSS) and the omission rate (OR), both calculated from the test dataset (Allouche et al., 2006). TSS was computed as sensitivity + specificity – 1, and OR as the proportion of known presences incorrectly predicted as unsuitable. To improve model generalization and minimize potential bias from a single random split, a k-fold cross-validation approach (k = 5) was applied. In each iteration, 80% of the occurrence data were used for training and 20% for testing. Mean AUC, TSS, and omission rate across folds were used to evaluate model robustness and ensure consistent predictive performance (Roberts et al., 2017).

3 Results

3.1 Model evaluation

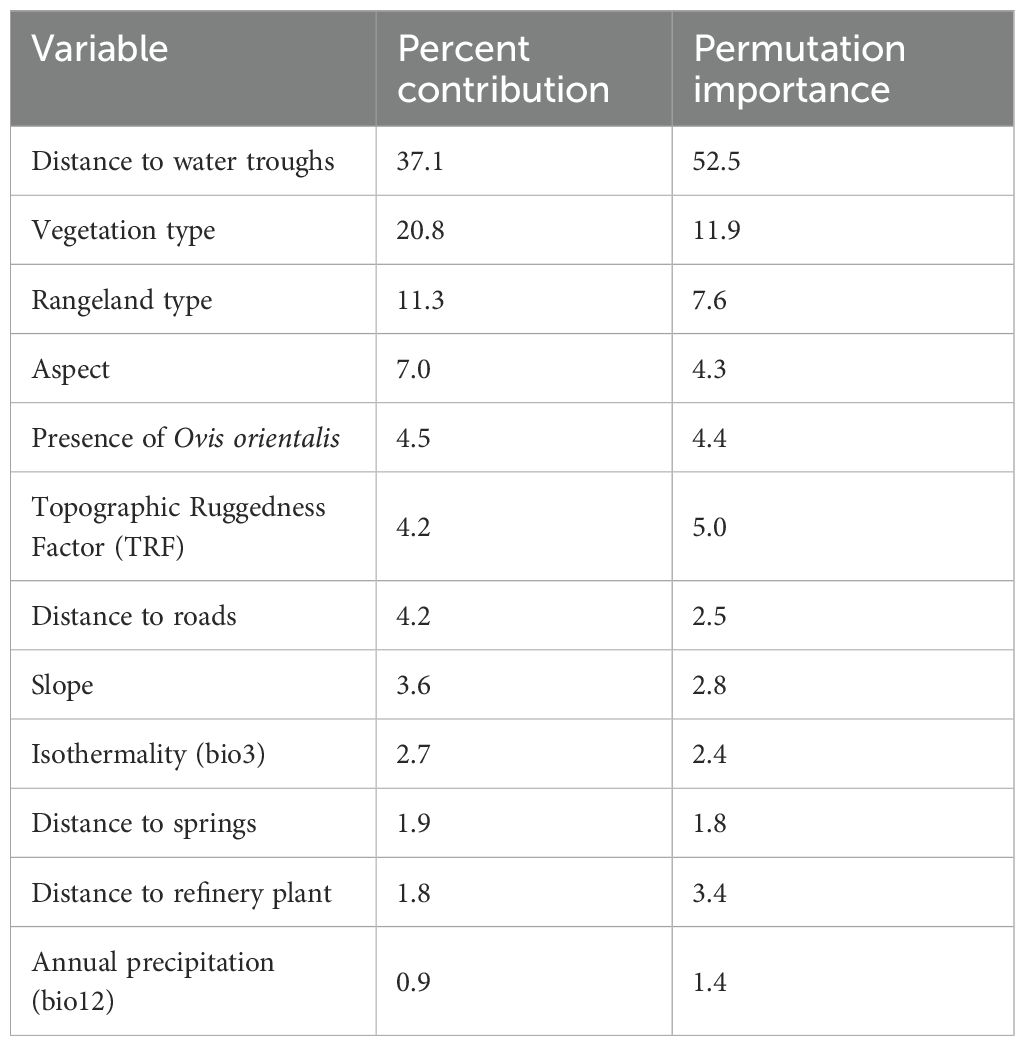

The MaxEnt model demonstrated consistently strong predictive performance across all five cross-validation folds. Mean evaluation metrics indicated excellent model reliability, with an average AUC of 0.959 (p = 0.01), a TSS of 0.84, and an OR of 0.06, collectively indicating high discrimination ability and no evidence of overfitting. This result confirms the model’s strong discriminatory power, with a high level of agreement between predicted suitability and species presence. The high consistency among cross-validation folds further supports the robustness and stability of the model prediction (Figure 4). Table 4 presents the percent contribution of each environmental variable to the model. The most influential predictor was distance to water troughs, followed by vegetation type, rangeland class, aspect, and the habitat suitability of Ovis orientalis. Together, distance to water troughs and vegetation type accounted for 64.4% of the total variable contribution, indicating their dominant role in shaping Persian leopard habitat distribution within the park. Additional predictors such as TRF, rangeland classification, and prey availability, highlighting the combined influence of topography, vegetation structure, and biotic interactions in determining suitable habitats for this endangered carnivore.

Figure 4. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and Area Under the Curve (AUC) value for the MaxEnt model predicting Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) habitat suitability in Bamu National Park (BNP). The mean AUC value of 0.959 (shown in red) indicates excellent model performance. Blue shading represents the standard deviation across 100 replicates, and the black diagonal line denotes random prediction.

Table 4. Percent contribution and permutation importance of environmental variables used in the MaxEnt model for predicting Persian leopard (P. pardus saxicolor) habitat suitability in Bamu National Park (BNP).

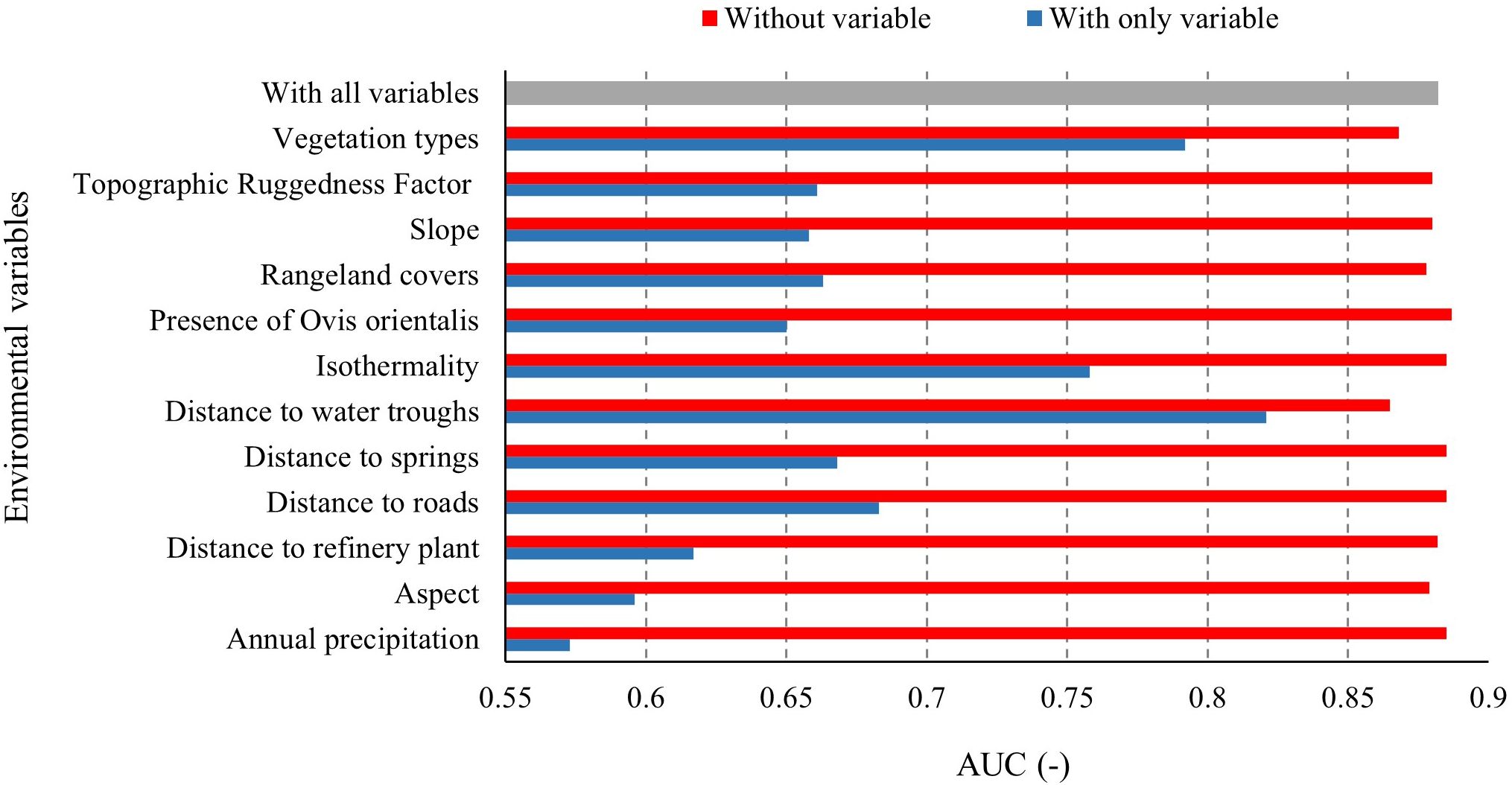

The importance of environmental variables in developing the Persian leopard distribution model was evaluated using the Jackknife test (Figure 5). The results, based on AUC values derived from the test data, are presented in Figure 5. In the figure, blue bars indicate the model’s AUC when trained using each variable individually, reflecting the independent predictive power of each variable. The results show that distance to water troughs had the highest AUC when used alone, suggesting it provides the most informative and independently valuable contribution to the model. Green bars represent the model’s AUC when all variables except the one in question are included. The removal of distance to water troughs led to the largest decline in model performance, indicating that this variable contains unique information not captured by others. Thus, distance to water troughs was identified as the most influential environmental variable in predicting Persian leopard habitat suitability.

Figure 5. Results of the Jackknife test showing the relative importance of environmental variables in the Persian leopard habitat suitability model. Bars represent the model performance (AUC) when each variable is used in isolation (blue), omitted from the model (red), or included with all variables (gray).

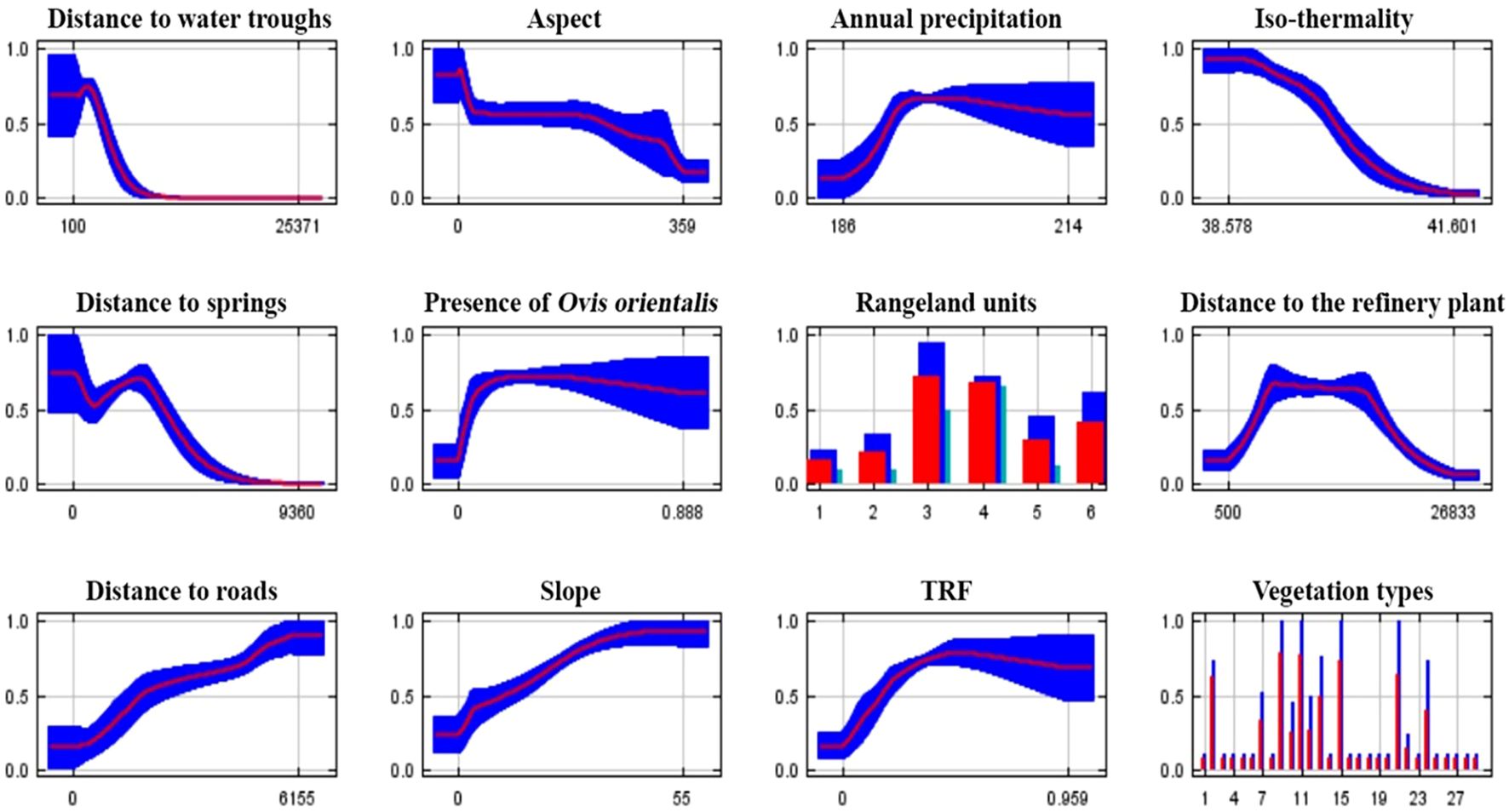

In the present study, species response curves to environmental variables were also examined (Figure 6). These curves illustrate how the predicted probability of species presence changes as individual variables vary, while all other variables are held at their mean values. The y-axis represents the probability of suitable conditions, based on the logistic output of the model, and the x-axis indicates the range of values for each variable. The red curve denotes the average response across all model runs, while the blue shading (or two-tone shading for categorical variables) represents one standard deviation from the mean. Among the environmental variables analyzed, distance to water troughs had the strongest influence on predicted habitat suitability. Suitability sharply declined with increasing distance, with the highest probability of occurrence found within 2,000 meters. Isothermality (bio3) exhibited a unimodal response: suitability peaked at intermediate values around 39%, with lower suitability observed at both extremes. For vegetation types, categories 9, 11, and 15 were associated with the highest predicted suitability, suggesting these vegetation communities offer favorable structural or ecological conditions for Persian leopards. The response to distance from roads showed a consistent positive trend, with suitability increasing as distance increased—peaking beyond 5,000 meters. The distance to springs response followed a three-phase pattern: a decline in suitability with increasing distance up to ~1,000 m, a brief peak between 1,000 and 2,500 m, and a subsequent decline beyond 3,000 m. Regarding rangeland cover, units 3 and 4—defined as poor rangelands on massive rocky hills and exposed rocky slopes, respectively—showed the highest predicted suitability. In contrast, unit 1 (sparsely wooded rangelands on massive rocky mountains) exhibited the lowest predicted suitability for Persian leopard occurrence.

Figure 6. Response curves showing the effect of environmental variables on the predicted habitat suitability for the Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor). The red line represents the mean response across all MaxEnt model replicates, while the blue shading indicates one standard deviation. For continuous variables, the x-axis shows the range of variable values; for categorical variables, bars represent different vegetation and rangeland classes. These curves illustrate the species’ sensitivity to key variables such as distance to water troughs, vegetation type, isothermality, and distance to roads.

3.2 Habitat suitability map

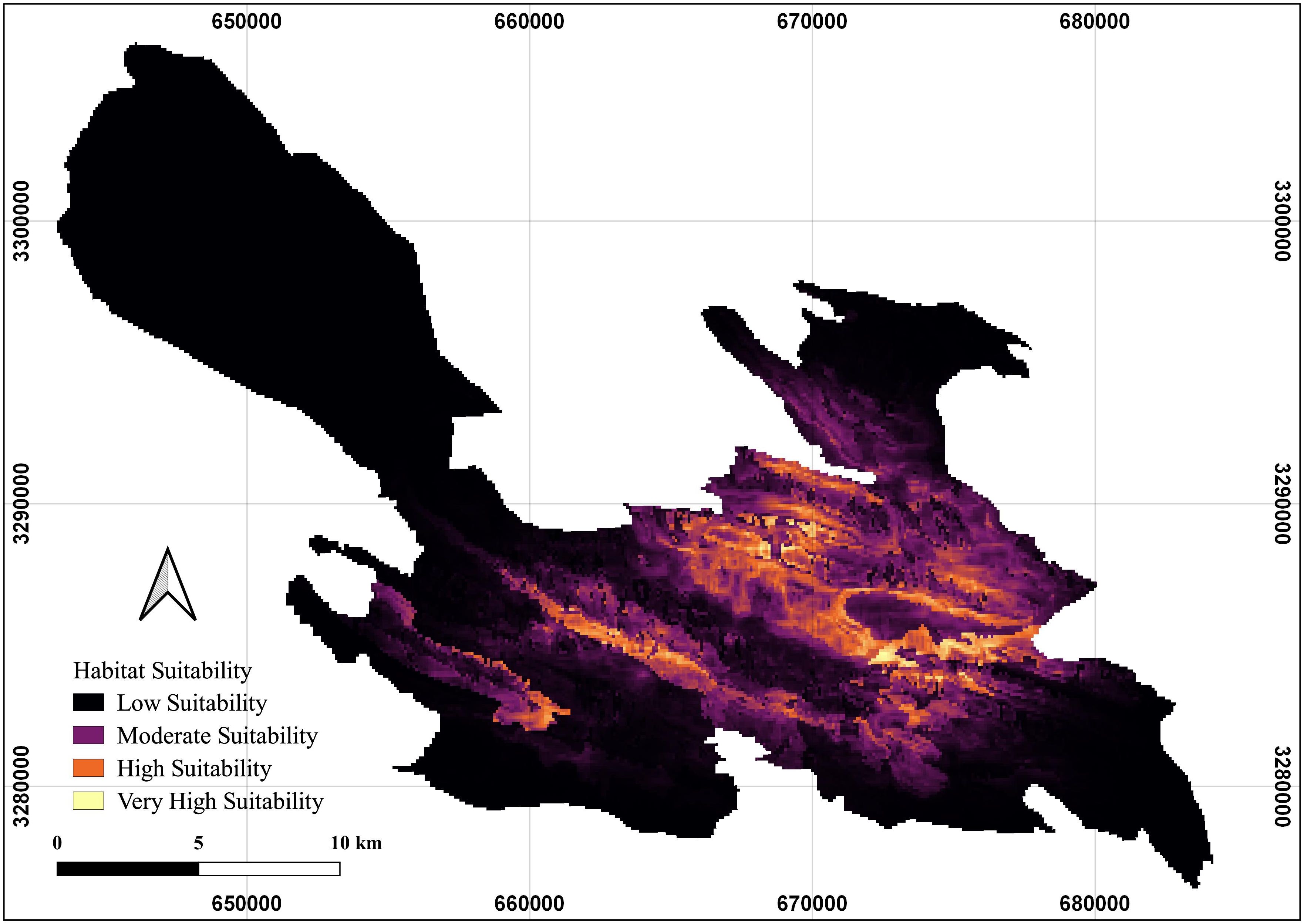

Following the identification of key environmental variables and analysis of species response curves, a habitat suitability map for the Persian leopard in BNP was generated (Figure 7). The map illustrates the spatial variation in predicted suitability, with a color gradient ranging from low (dark blue) to high (bright yellow). High-suitability habitats are concentrated along the central and southeastern ridgelines and upper valleys of BNP, particularly in rugged terrain characterized by steep slopes and proximity to artificial water troughs and prey-rich rangelands. These areas represent optimal environmental conditions for leopard presence, providing cover, prey accessibility, and reduced human disturbance. In contrast, low-suitability zones are mainly distributed in the northwestern and peripheral lowlands of the park, where flatter terrain, sparse vegetation, and greater proximity to roads or human activity reduce habitat quality. This spatial pattern emphasizes the ecological importance of the park’s central mountainous core as a conservation priority for sustaining the Persian leopard population.

Figure 7. Predicted habitat suitability map for the Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in Bamu National Park (BNP), southern Iran.

4 Discussion

4.1 Model evaluation

The distribution of animal species in natural ecosystems is shaped by a combination of environmental factors aligned with their ecological requirements and tolerance ranges. Identifying the key drivers of species distributions is essential not only for locating suitable habitats but also for informing restoration efforts and conservation planning (Sun et al., 2024; Thammanu et al., 2021). The high AUC value obtained from the MaxEnt model indicates excellent predictive performance for identifying suitable habitats for the Persian leopard in the study area. These results demonstrate the model’s strong ability to discriminate between favorable and unfavorable areas for the species. Moreover, the substantial overlap between the training and test datasets further supports the reliability of the model’s predictions. These findings are consistent with previous studies (Ebrahimi et al., 2017; Jafari et al., 2018; Rozhnov et al., 2020; Majeed et al., 2023; Shahsavarzadeh et al., 2023; Jamali et al., 2024), which also reported strong performance of MaxEnt in modeling Persian leopard distribution. The results affirm that MaxEnt is well-suited for modeling this species’ habitat preferences and aligns closely with observed ecological patterns. Similarly, Majeed et al. (2023) found that MaxEnt reliably predicted the potential effects of climate change on the Persian leopard’s distribution in Iran, reinforcing the model’s applicability for conservation planning under changing environmental conditions.

Beyond felids, MaxEnt has also demonstrated strong performance in modeling habitat suitability for other mammals, including the goitered gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa; Khosravi et al., 2016), tiger (Panthera tigris; Agrawal and Awasthi, 2024), North-Chinese leopard (Panthera pardus japonensis; Yang et al., 2025), Himalayan brown bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus; Hosseini et al., 2022), brown bear (Ursus arctos; Acarer, 2024), and Asian elephant (Elephas maximus; Budhathoki et al., 2023). These studies collectively confirm the model’s versatility across taxa, underscoring its reliability for large-mammal conservation under diverse ecological settings.

4.2 Environmental determinants of Persian leopard habitat

Among the environmental variables analyzed, distance to water troughs emerged as the most influential predictor of Persian leopard distribution, contributing more than one-third of the total model gain and causing the largest drop in AUC when excluded in the Jackknife test. This strong effect suggests that artificial water sources serve as critical attractants for both the Persian leopard and its prey, particularly in arid and semi-arid landscapes such as BNP. The observed decline in habitat suitability with increasing distance from water troughs—most notably beyond 2,000 m—highlights the species’ reliance on areas with proximate, reliable water access. This finding is consistent with broader regional studies. Almasieh and Mohammadi (2025) also identified distance to water resources as the most significant factor influencing leopard distribution in the central plains of Iran, where limited rainfall and the scarcity of permanent rivers force leopards to depend more on artificial water points.

Similarly, Poursalem et al. (2021) reported distance to water as the second most important predictor of habitat suitability for the species in southwestern Iran, which shares similar climatic conditions with our study area. Likewise, natural water bodies perform a comparable ecological function in our landscape. Rivers not only provide drinking water but also enhance hunting opportunities due to higher prey abundance and diversity along riparian corridors (Kaboodvandpour et al., 2021). Therefore, whether artificial (water troughs) or natural (river systems), proximity to consistent water resources is a key determinant of Persian leopard habitat selection, underscoring the species’ dependence on water-associated habitats for survival and successful predation.

This relationship can be further understood by considering the hydrographic and management context of BNP. BNP lies within the southern Zagros Mountains and experiences a semi-arid climate with a mean annual rainfall of approximately 250 mm (Attarod et al., 2016), resulting in limited permanent surface water. Most streams in the park are ephemeral, flowing only after seasonal rains during winter and spring. A few perennial springs—such as Tang-e-Hana, Tang-e-Bostanak, and Garmab—provide year-round water in central and southeastern valleys. To offset seasonal shortages, the Department of the Environment has installed several artificial water troughs across the park since the early 2000s. These troughs, constructed of concrete or metal and supplied by groundwater or piped storage tanks, are mainly located near ranger stations and mid-elevation valleys, both inside and along the park boundary. They serve as critical dry-season water sources for wildlife, attracting herbivores and, consequently, large predators such as the Persian leopard. However, their proximity to managed or grazed areas may also increase the potential for human–wildlife interactions. Regular maintenance and seasonal refilling of these troughs are currently part of BNP’s management strategy to sustain wildlife populations during prolonged droughts. From a conservation perspective, optimizing the spatial placement and monitoring of these artificial sources is crucial to balance their ecological benefits with the risk of conflict or overdependence by wildlife.

The strong influence of artificial water troughs on habitat suitability may, however, partially reflect the spatial clustering of ranger patrol routes and camera traps around these accessible locations, introducing potential sampling bias. Nevertheless, water availability remains a genuine ecological driver in arid ecosystems, where both natural and artificial sources act as focal points for prey concentration and thermoregulation, thereby indirectly increasing predator activity (Farhadinia et al., 2018). The observed response likely represents an interaction of both ecological dependence and sampling proximity. Future research should aim to disentangle these effects through systematic camera placement across different habitat types and independent validation using telemetry data. Beyond Iran, similar environmental determinants have been reported across leopard populations in both Asia and Africa. In the Indian subcontinent, leopards often concentrate in rugged terrain near reliable water sources and prey-rich zones, while avoiding areas of intense human disturbance (Odden et al., 2014; Gupta et al., 2021). Comparable patterns have been observed in Nepal, where proximity to natural water bodies and moderate vegetation cover enhances leopard occurrence, underscoring the species’ dependence on both prey and cover for successful hunting (Maharjan, 2016). In African savannas and semi-arid systems, water and prey availability remain equally important, but anthropogenic pressures—particularly roads, poaching, and livestock presence—emerge as primary constraints on leopard persistence (Jacobson et al., 2016; Swanepoel et al., 2013). Collectively, these studies highlight the remarkable ecological flexibility of leopards across their range; nevertheless, they consistently emphasize that prey accessibility, water proximity, and low human disturbance are universal prerequisites for maintaining viable populations. The results from BNP thus align with global evidence, illustrating how even adaptable carnivores remain vulnerable to resource limitation and human encroachment.

Vegetation type was the second most important variable, with the highest suitability associated with vegetation classes 9, 11, and 15. These communities, dominated by plant species such as Astragalus, Amygdalus–Artemisia aucheri, and Stipa hohenackeriana, likely support favorable structural conditions and forage resources for key prey species like Ovis orientalis and Capra aegagrus. This indirect association reinforces the idea that Persian leopard presence is tightly coupled with prey availability, which in turn is shaped by specific vegetation assemblages. The combined explanatory power of “distance to water troughs” and “vegetation type” accounted for 64.4% of the model’s predictive contribution, indicating that a mix of anthropogenic and ecological drivers governs habitat suitability in BNP. These findings are consistent with studies from other parts of the Persian leopard’s range (e.g., Thakur, 2024; Moradi et al., 2022), emphasizing the central role of water availability and habitat structure in shaping the spatial ecology of this endangered carnivore. Importantly, the strong influence of water troughs—an anthropogenic feature—suggests that human-modified elements of the landscape may inadvertently support Persian leopard habitat use, but also highlight the need to manage such features carefully to balance wildlife support and conflict mitigation. The significance of vegetation type as the second most influential predictor also provides actionable guidance for habitat restoration and management in BNP. Vegetation classes associated with higher suitability—particularly those dominated by Amygdalus–Artemisia aucheri and Stipa hohenackeriana—should be prioritized for conservation and rehabilitation, as these communities support the forage base of key prey species (Ovis orientalis and Capra aegagrus). Restoration strategies should focus on controlling overgrazing, reducing shrubland degradation, and promoting native shrub–grass assemblages that enhance both prey availability and structural cover for ambush hunting. Similar terrestrial carnivore studies have emphasized vegetation structure as a critical determinant of predator distribution (e.g., Heck and Crowder, 1991; Ismaili et al., 2024). Comparable findings have been reported for large mammals, where heterogeneous shrub–grass mosaics promote coexistence between large predators and their prey (Rather et al., 2020). Aligning BNP’s vegetation management with these ecological principles could simultaneously restore degraded rangelands, increase prey densities, and support the long-term persistence of the Persian leopard population.

Rangeland cover emerged as the third most influential factor shaping Persian leopard habitat suitability. The MaxEnt model revealed that units 3 and 4—classified as poor rangelands on massive rocky hills and exposed rocky slopes—had the highest predicted suitability. These rugged, remote landscapes likely offer reduced human disturbance and support higher densities of wild prey such as Capra aegagrus and Ovis orientalis (Farhadinia and Akbari, 2007), thereby increasing their attractiveness to Persian leopards. In contrast, unit 1 (sparsely wooded rangelands on massive Rocky Mountains) showed the lowest suitability, which may reflect lower prey availability or greater exposure to human activity.

Similarly, Khosravi et al. (2019) reported that rangelands—particularly grassland habitats—were the second most influential predictor of Persian leopard suitability in central Iran, underscoring the species’ strong association with open, rugged landscapes that combine prey availability with limited human disturbance. Ecologically, this pattern illustrates the Persian leopard’s adaptive use of semi-arid, structurally heterogeneous rangelands as functional refugia, where topographic complexity and patchy shrub cover provide both concealment and visibility essential for ambush predation (Hayward and Kerley, 2008). Such areas also allow individuals to reduce direct encounters with humans and livestock-guarding dogs, facilitating their persistence even in human-modified environments (Jacobson et al., 2016; Farhadinia et al., 2018). This adaptability highlights the ecological flexibility of the Persian leopard, enabling its continued occupancy across Iran’s fragmented rangeland ecosystems where forest habitats have declined or become heavily disturbed.

In this study, prey availability was also identified as an important variable influencing habitat suitability. The primary prey species for the Persian leopard include Capra aegagrus, Ovis vignei, and Ovis orientalis (Karami et al., 2016). Our results indicate a positive correlation between habitat suitability and the presence of Ovis orientalis, consistent with the findings of Farashi and Shariati (2018). This relationship also implicitly supports the results of Jafari et al. (2018), who reported a decline in habitat suitability as the distance to prey increased. Similarly, Khosravi et al. (2021) found that prey availability was the most influential predictor of Persian leopard distribution in Isfahan and Yazd provinces in central Iran. Ebrahimi et al. (2017) reported comparable results at the national scale, highlighting the central role of prey abundance in determining Persian leopard habitat suitability across Iran. Collectively, these findings suggest that leopard distribution is strongly shaped by bottom-up ecological processes, where the spatial availability of prey governs habitat use, movement patterns, and ultimately, the persistence of the species in human-dominated landscapes.

TRF also ranked among the most influential predictors, reinforcing the importance of topographic complexity for Persian leopard persistence. This finding is consistent with previous studies that used various roughness indices—such as vector ruggedness measure (VRM), topographic ruggedness index (TRI), and elevation variance—and consistently identified rugged terrain as critical for Persian leopard habitat (e.g., Vesali et al., 2017; Kaboodvandpour et al., 2021; Khosravi et al., 2021; Shoaee et al., 2017). Rugged areas may offer better cover, hunting opportunities, and lower risk of human encounter. Our results confirm that Persian leopards favor topographically complex landscapes, where ecological conditions align with both their behavioral ecology and prey availability. From an ecological perspective, such terrain functions as a natural refuge—reducing hunting pressure and human accessibility—while simultaneously enhancing ambush success and prey encounter rates, making topographic heterogeneity a key prerequisite for long-term population persistence.

Suitability increased consistently with distance from roads, reaching maximum values beyond 5,000 m—indicating that Persian leopards actively avoid road-adjacent areas, likely due to elevated disturbance and mortality risks. This pattern was evident in BNP, where aside from a major highway bisecting the park’s western corridor, roads are primarily concentrated along the northeastern and southeastern margins. The species’ apparent avoidance of these areas underscores the importance of road-free zones for conservation planning. This avoidance behavior reflects both direct threats—such as vehicle collisions (Naderi et al., 2018) and poaching access (Farhadinia et al., 2009)—and indirect impacts including habitat fragmentation, altered prey movement, and increased human presence, emphasizing that road expansion without proper mitigation could severely compromise leopard movement, genetic exchange, and long-term survival.

Anthropogenic features such as artificial water troughs and roads create a complex ecological trade-off for Persian leopards, acting simultaneously as attractants and risk-prone habitats. Water troughs enhance prey aggregation and provide essential hydration in arid environments but may also increase the likelihood of human–wildlife encounters near managed sites. Similarly, while certain roads can facilitate movement along landscape edges, they primarily elevate mortality risk through vehicle collisions, poaching access, and habitat fragmentation. These contrasting effects highlight the need for strategic landscape planning—maintaining water access for wildlife while minimizing road expansion and disturbance in key habitats (Clements et al., 2014; Naderi et al., 2018).

The response to distance from springs followed a nonlinear, three-phase curve: initial suitability declined with increasing distance, followed by a brief peak between ~1,000 and 2,500 m, and a subsequent decline beyond 3,000 m. This suggests that Persian leopards may favor intermediate distances from springs—balancing access to natural water sources with reduced exposure to human activity, which is often concentrated near springs. Ecologically, this pattern reflects an adaptive trade-off in leopard spatial behavior, where individuals remain close enough to springs to access water and prey, yet far enough to minimize encounters with pastoralists, livestock, and potential persecution—highlighting springs as both ecological hotspots and potential conflict zones within arid landscapes.

The results indicated that steep slopes play a significant role in determining suitable habitats for the Persian leopard, primarily due to the species’ preference for rugged and mountainous terrain. Topography (particularly slope) strongly influences the distribution of both predator and prey species, making it a key ecological factor shaping wildlife presence. This is especially relevant for the Persian leopard, as many of its primary prey species, including Ovis orientalis, occupy steep, mountainous regions. Consequently, the Persian leopard’s dependence on these prey species enhances the desirability of such habitats, highlighting slope as a critical variable in modeling habitat suitability. Beyond prey availability, steep landscapes may also provide reduced human accessibility, enhanced stalking cover, and elevated vantage points—factors that collectively improve hunting success and lower mortality risk. This suggests that slope functions not merely as a physical attribute but as a multifunctional ecological refuge that supports both predator survival and hunting efficiency (Jacobson et al., 2016; Farhadinia et al., 2018).

Isothermality exhibited a unimodal relationship with habitat suitability, peaking at approximately 39%, with reduced suitability observed at both lower and higher values. This pattern suggests that Persian leopards may favor thermally stable environments characterized by moderate diurnal temperature ranges. Such conditions likely optimize energetic efficiency for both leopards and their prey, reducing thermal stress while maintaining sufficient daily temperature variation to support diverse vegetation and prey communities, thereby enhancing overall habitat quality.

Model predictions highlight several priority zones within BNP that warrant focused conservation attention. The northeastern and southeastern sectors—particularly the Tang-e-Hana, Tang-e-Bostanak, and Garmab rangelands—showed the highest habitat suitability for the Persian leopard, corresponding to areas of high prey availability and stable water access. These regions are also characterized by relatively low human density and limited road intrusion, making them suitable for targeted conservation action. Management efforts should prioritize these zones for intensified anti-poaching patrols, installation of remote monitoring systems, and protection of key water resources to reduce conflict and maintain ecological connectivity between core habitats.

While artificial water troughs play an important role in sustaining wildlife populations during prolonged dry periods, they also present a management dilemma. Concentrating prey and predators around artificial water points may increase the likelihood of livestock depredation and human–wildlife conflict near grazing areas and ranger stations. These artificial features can act as ecological attractants but also as conflict hotspots when located near pastoral zones. To balance these trade-offs, water provisioning should be spatially planned—favoring placement in core conservation zones while limiting access in human-dominated areas—and coupled with community-based monitoring and conflict mitigation programs (Valeix et al., 2010; Stein et al., 2020).

4.3 Research limitations and future directions

Although this study applied a rigorous modeling framework, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the relatively small number of verified occurrence records (n = 42) may constrain model generalization; however, this limitation was addressed through spatial thinning using the spThin package (Aiello-Lammens et al., 2015), k-fold cross-validation (k = 5), and multiple evaluation metrics (AUC, TSS, and OR), all of which minimized sampling bias and overfitting. Second, a potential source of circularity may arise from partial overlap between the environmental variables used in the Persian leopard model and those used to generate the prey suitability layer for Ovis orientalis. Although the prey layer was based on an independent dataset of field-verified observations, shared predictors such as vegetation type, elevation, and slope could have introduced minor bias. Future work should incorporate direct prey occurrence or abundance data from field surveys, camera traps, or distance sampling to avoid this issue. Third, the environmental variables were static and represent long-term averages, which may not fully capture temporal variability in vegetation, resource availability, or anthropogenic disturbance. While this is a common simplification in species distribution modeling, incorporating dynamic time-series data (e.g., NDVI or seasonal productivity indices) could provide deeper insight into temporal habitat dynamics and seasonal movements. Beyond these limitations, future studies should also integrate dynamic environmental drivers such as climate variability and land-use change to project habitat shifts and optimize adaptive management. The strong influence of water availability observed in this study suggests that managing both artificial and natural water sources can serve as a critical conservation lever. Incorporating these spatially explicit findings into regional conservation policy will help enhance ecological connectivity, reduce conflict risk, and strengthen the long-term persistence of the Persian leopard in Iran’s fragmented landscapes.

Despite these constraints, the methodological safeguards applied in this study—particularly spatial bias correction, cross-validation, and multi-metric evaluation—enhance confidence in the robustness and ecological validity of the results.

5 Conclusions

Our MaxEnt modeling of Persian leopard (P. pardus saxicolor) habitat suitability in BNP revealed that water accessibility, vegetation type, and terrain features are the most influential factors shaping the species’ distribution. Specifically, distance to water troughs and vegetation type jointly accounted for over 64% of the model’s predictive contribution. This finding highlights the importance of maintaining water sources and structurally diverse vegetation communities—particularly types 9, 11, and 15 (Table 2, Figure 2), which support preferred prey such as Ovis orientalis and Capra aegagrus. Additional predictors such as topographic ruggedness, distance from roads, and rangeland units with rocky, less accessible substrates further show the Persian leopard’s reliance on undisturbed, topographically complex environments. These spatial patterns affirm the species’ ecological dependence on remote, prey-rich habitats, and provide fine-scale insights that improve upon earlier regional-scale models.

From a conservation planning perspective, our results provide a practical framework to guide site-specific management actions in and around BNP. High-suitability zones identified in this study should be prioritized for protection, particularly those with limited anthropogenic pressure and strong connectivity potential. Because Persian leopards regularly range beyond the protected area, effective coexistence with nearby communities is critical. Management strategies should therefore include community engagement initiatives, such as improved livestock husbandry practices (e.g., predator-proof corrals), compensation or insurance schemes for depredation losses, and early-warning or rapid-response systems to mitigate conflict. Linking the spatial predictions from this study with the distribution of surrounding settlements and their dominant land uses will further enable targeted intervention and long-term coexistence planning.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Research Ethics committees of Lorestan University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

FS: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation. AF: Investigation, Writing – original draft. PS: Visualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology. GGM: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. AD: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. MVM: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. SMMS: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acarer A. (2024). Brown bear (Ursus arctos L.) distribution model in Europe. Šumarski List 148, 1–12. doi: 10.31298/sl.148.5-6.4

Agrawal P. and Awasthi R. K. (2024). Species distribution modelling (SDM) of Panthera tigris and prediction of suitability of habitats based on its presence locations and environmental variables. Int. J. Sci. Res. 1496), 115–133. doi: 10.21275/SR25530145547

Ahmadi M., Farhadinia M. S., Cushman S. A., Hemami M.-R., Nezami Balouchi B., Jowkar H., et al. (2020). Species and space: A combined gap analysis to guide management planning of conservation areas. Landscape Ecol. 35, 1505–1517. doi: 10.1007/s10980-020-01033-5

Ahmadi M., Hemami M. R., Kaboli M., and Shabani F. (2023). MaxEnt brings comparable results when the input data are being completed; Model parameterization of four species distribution models. Ecol. Evol. 13, e9827. doi: 10.1002/ece3.9827

Ahmed S. H. and Majeed S. I. (2023). Population estimate and conservation status of the Persian Leopard, Panthera pardus tulliana, in the Bamo and Khoshk Mountains in Kurdistan Region, northern Iraq. Zoology Middle East 69, 79–86. doi: 10.1080/09397140.2023.2200091

Aiello-Lammens M. E., Boria R. A., Radosavljevic A., Vilela B., and Anderson R. P. (2015). spThin: an R package for spatial thinning of species occurrence records for use in ecological niche models. Ecography 38, 541–545. doi: 10.1111/ecog.01132

Allouche O., Tsoar A., and Kadmon R. (2006). Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J. Appl. Ecol. 43, 1223–1232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01214.x

Almasieh K. and Mohammadi A. (2025). Assessment of habitat fragmentation for grey wolf and Persian leopard in some Iranian desert landscapes. Sci. Rep. 15, 32182. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-17644-4

Almasieh K., Rouhi H., and Kaboodvandpour S. (2019). Habitat suitability and connectivity for the brown bear (Ursus arctos) along the Iran-Iraq border. Eur. J. Wildlife Res. 65, 57. doi: 10.1007/s10344-019-1295-1

Ashrafzadeh M., Khosravi R., Adibi M., Taktehrani A., Wan H., and Cushman S. A. (2020). A multi-scale, multi-species approach for assessing the effectiveness of habitat and connectivity conservation for endangered felids. Biol. Conserv. 245, 108523. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108523

Ashrafzadeh M. R., Naghipour A. A., Haidarian M., and Khorozyan I. (2018). Modeling the response of an endangered flagship predator to climate change in Iran. Mammal Res. 64, 39–51. doi: 10.1007/s13364-018-0384-y

Attarod P., Rostami F., Dolatshahi A., Sadeghi S. M. M., Amiri G. Z., and Bayramzadeh V. (2016). Do changes in meteorological parameters and evapotranspiration affect declining oak forests of Iran? J. For. Sci. 62, 553–561. doi: 10.17221/83/2016-JFS

Baldwin R. (2009). Use of maximum entropy modeling in wildlife research. Entropy, 11 (4), 854–866. doi: 10.3390/e11040854

Budhathoki S., Gautam J., Budhathoki S., and Jaishi P. P. (2023). Predicting the habitat suitability of Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) under future climate scenarios. Ecosphere 14, e4678. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.4678

Clements H. S., Tambling C. J., Hayward M. W., and Kerley G. I. (2014). An objective approach to determining the weight ranges of prey preferred by and accessible to the five large African carnivores. PloS One 9, e101054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101054

Comia-Geneta G., Reyes-Haygood S. J., Salazar-Golez N. L., Seladis-Ocampo N. A., Samuel-Sualibios M. R., Dagamac N. H. A., et al. (2024). Development of a novel optimization modeling pipeline for range prediction of vectors with limited occurrence records in the Philippines: a bipartite approach. Modeling Earth Syst. Environ. 10, 3995–4011. doi: 10.1007/s40808-024-02005-3

Ebrahimi A., Farashi A., and Rashki A. (2017). Habitat suitability of Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in Iran in future. Environ. Earth Sci. 76, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12665-017-7040-8

Elith J., Graham C. H., Anderson R. P., Dudík M., Ferrier S., Guisan A., et al. (2006). Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29, 129–151. doi: 10.1111/j.2006.0906-7590.04596.x

Elith J., Philips S. J., Hastie T., Dudík M., Chee Y. E., and Yates C. J. (2011). A statistical explanation of MAXENT for ecologists. Diversity Distributions 17, 43–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4642.2010.00725.x

Erfanian B., Mirkarimi S. H., Mahini A. S., and Rezaei H. R. (2013). A presence-only habitat suitability model for Persian leopard Panthera pardus saxicolor in Golestan National Park, Iran. Wildlife Biol. 19, 170–178. doi: 10.2981/12-045

Farashi A. and Shariati M. (2018). Evaluation of the role of the national parks for Persian leopard (Panther pardus saxicolor, Pocock 1927) habitat conservation (case study: Tandooreh National Park, Iran). Mammal Res. 63, 425–432. doi: 10.1007/s13364-018-0370-4

Farhadinia M. S., Ahmadi M., Sharbafi E., Khosravi S., Alinezhad H., and Macdonald D. W. (2015). Leveraging trans-boundary conservation partnerships: Persistence of Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in the Iranian Caucasus. Biol. Conserv. 191, 770–778. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.08.027

Farhadinia M. S. and Akbari H. (2007). Ecology and status of the caracal, Caracal caracal, (Carnivora: Felidae), in the Abbasabad Naein Reserve, Iran. Zool. Midd 41, 5–10. doi: 10.1080/09397140.2007.10638221

Farhadinia M. S., Johnson P. J., Macdonald D. W., and Hunter L. T. (2018). Anchoring and adjusting amidst humans: ranging behavior of Persian leopards along the Iran-Turkmenistan borderland. PloS One 13, e0196602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196602

Farhadinia M. S., Mahdavi A., and Hosseini-Zavarei F. (2009). Reproductive ecology of the Persian Leopard, Panthera pardus saxicolor, in Sarigol National Park, northeastern Iran: (Mammalia: Felidae). Zoology Middle East 48, 13–16. doi: 10.1080/09397140.2009.10638361

Fick S. (2017). WorldClim 2: new 1km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatology 37, 4302–4315. doi: 10.1002/joc.5086

Ghoddousi A., Bleyhl B., Sichau C., Ashayeri D., Moghadas P., Sepahvand P., et al. (2020). Mapping connectivity and conflict risk to identify safe corridors for the Persian leopard. Landscape Ecol. 35, 1809–1825. doi: 10.1007/s10980-020-01062-0

Ghoddousi A., Hamidi A. K., Ghadirian T., Ashayeri D., and Khorozyan I. (2010). The status of the endangered Persian leopard Panthera pardus saxicolor in Bamu National Park, Iran. Oryx 44, 551–557. doi: 10.1017/S0030605310000827

Ghoddousi A., Hamidi A. H. K., Ghadirian T., Ashayeri D., Moshiri H., and Khorozyan I. (2008). The status of the persian leopard in Bamu National Park, Iran. Cat News 49, 10–13. doi: 10.1017/S0030605310000827

Ghoddousi A. and Khorozyan I. (2024). Panthera pardus ssp. tulliana (amended version of 2023 assessment) (IUCN, Gland, Switzerland: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species), e.T15961A259040841. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2023-1.RLTS.T15961A50660903.en

Gupta V. D., Areendran G., Raj K., Ghosh S., Dutta S., and Sahana M. (2021). “Assessing habitat suitability of leopards (Panthera pardus) in unprotected scrublands of Bera, Rajasthan, India,” in Forest resources Resilience and Conflicts (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Ltd & Academic Press), 329–342. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-822931-6.00026-5

Hayward M. W. and Kerley G. I. (2008). Prey preferences and dietary overlap amongst Africa's large predators. South Afr. J. Wildlife Res. 38, 93–108. doi: 10.3957/0379-4369-38.2.93

Heck K. Jr. and Crowder L. B. (1991). “Habitat structure and predator—prey interactions in vegetated aquatic systems,” in Habitat structure: the physical arrangement of objects in space (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht), 281–299. doi: 10.1007/978-94-011-3076-9_14

Hemami M. R., Esmaeili S., and Soffianian A. R. (2015). The prediction of the distribution of Asian cheetah, Persian leopard, and brown bear in response to environmental variables in Isfahan Province. Appl. Ecol. 4, 51–564. doi: 10.18869/acadpub.ijae.4.13.51

Hernandez P. A., Graham C. H., Master L. L., and Albert D. L. (2006). The effect of sample size and species characteristics on performance of different species distribution modeling methods. Ecography 29, 773–785. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-7590.2006.04700.x

Hosseini S. P., Amiri M., and Senn J. (2022). The effect of environmental and human factors on the distribution of Brown bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus) in Iran. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 20, 153–170. doi: 10.15666/aeer/2001_153170

Hosseini M., Farashi A., Khani A., and Farhadinia M. S. (2019). Landscape connectivity for mammalian megafauna along the Iran-Turkmenistan-Afghanistan borderland. J. Nat. Conserv. 52, 125735. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2019.125735

Hosseini N., Mostafavi H., and Ghorbanpour M. (2025). The future range of two Thymus daenensis subspecies in Iran under climate change scenarios: MaxEnt model-based prediction. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 72, 717–734. doi: 10.1007/s10722-024-01998-1

Hushmand F., Karimiyan A. A., Elmi M. R., and Azimzadeh H. R. (2022). A study of land cover changes in Bamu national park within three time ranges from 1987 to 2011. Desert Ecosystem Eng. 4, 75–86.

Ismaili R. R. R., Peng X., Li Y., Ali A., Ahmad T., Rahman A. U., et al. (2024). Modeling habitat suitability of snow leopards in Yanchiwan National reserve, China. Animals 14, 1938. doi: 10.3390/ani14131938

Jacobson A. P., Gerngross P., Lemeris J. R. Jr., Schoonover R. F., Anco C., Breitenmoser-Würsten C., et al. (2016). Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range. PeerJ 4, e1974. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1974

Jafari A., Zamani-Ahmadmahmoodi R., and Mirzaei I. (2018). Persian leopard and wild sheep distribution modeling using the Maxent model in the Tang-e-Sayad protected area, Iran. Mammalia 83, 84–96. doi: 10.1515/mammalia-2016-0155

Jamali F., Amininasab S. M., Taleshi H., and Madadi H. (2024). Ensemble forecasting of Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) distribution and habitat suitability in south-western Iran. Wildlife Res. 51, WR23010. doi: 10.1071/WR23010

Jianhui G. O. N. G., Yibin L. I., Ruifen W. A. N. G., Chenxing Y. U., Jian F. A. N., and Kun S. H. I. (2023). MaxEnt modeling for predicting suitable habitats of snow leopard (Panthera uncia) in the mid-eastern Tianshan Mountains. J. Resour. Ecol. 14, 1075–1085. doi: 10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2023.05.018

Kaboodvandpour S., Almasieh K., and Zamani N. (2021). Habitat suitability and connectivity implications for the conservation of the Persian leopard along the Iran–Iraq border. Ecol. Evol. 11, 13464–13474. doi: 10.1002/ece3.8069

Karami M., Ghadirian T., and Faizolahi K. (2016). The atlas of the mammals of Iran (Tehran, Iran: Department of the Environment of Iran).

Khorozyan I. (2014). Morphological variation and sexual dimorphism of the common leopard (Panthera pardus) in the Middle East and their implications for species taxonomy and conservation. Mamm. Biol. 79, 398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.mambio.2014.07.004

Khorozyan I., Ghoddousi S., M. S., and Waltert M. (2020). Studded leather collars are very effective in protecting cattle from leopard (Panthera pardus) attacks. Ecol. Solutions Evidence 1, e12013. doi: 10.1002/2688-8319.12013

Khosravi R., Hemami M. R., and Cushman S. A. (2018). Multispecies assessment of core areas and connectivity of desert carnivores in central Iran. Diversity Distributions 24, 193–207. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12672

Khosravi R., Hemami M.-R., and Cushman S. A. (2019). Multi-scale niche modeling of three sympatric felids of conservation importance in central Iran. Landscape Ecol. 34, 2451–2467. doi: 10.1007/s10980-019-00900-0

Khosravi R., Hemami M., Malakoutikhah S., Ashrafzadeh M., and Cushman S. A. (2021). Prey availability modulates predicted range contraction of two large felids in response to changing climate. Biol. Conserv. 255, 109018. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109018

Khosravi R., Hemami M. R., Malekian M., Flint A., and Flint L. (2016). Maxent modeling for predicting potential distribution of goitered gazelle in central Iran: the effect of extent and grain size on performance of the model. Turkish J. Zoology 40, 574–585. doi: 10.3906/zoo-1505-38

Kramer-Schadt S., Niedballa J., Pilgrim J. D., Schröder B., Lindenborn J., Reinfelder V., et al. (2013). The importance of correcting for sampling bias in MaxEnt species distribution models. Diversity Distributions 19, 1366–1379. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12096

Lamichhane S., Pathak A., Gurung A., Karki A., Rayamajhi T., Khatiwada A., et al. (2024). Are wild prey sufficient for the top predators in the lowland protected areas of Nepal? Ecol. Evol. 14, e70387. doi: 10.1002/ece3.70387

Liu C., Berry P. M., Dawson T. P., and Pearson R. G. (2005). Selecting thresholds of occurrence in the prediction of species distributions. Ecography 28, 385–393. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-7590.2005.03957.x

Luna-Aranguré C. and Vázquez-Domínguez E. (2021). Of pandas, fossils, and bamboo forests: ecological niche modeling of the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) during the Last Glacial Maximum. J. Mammalogy 102, 718–730. doi: 10.1093/jmammal/gyab033

Maharjan B. (2016). Geo-spatial analysis of habitat suitability for common leopard (Panthera pardus) in Shivapuri Nagarjun National Park, Nepal. University of Salzburg, Austria.

Majeed K. A., Khwarahm N. R., and Ahmed S. H. (2023). Predicting the geographical distribution of the Persian leopard, Panthera pardus tulliana, a rare and endangered species. J. Nat. Conserv. 76, 126505. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2023.126505

Merow C., Smith M. J., and Silander J. A. Jr. (2013). A practical guide to MaxEnt for modeling species' distributions: what it does, and why inputs and settings matter. Ecography 36, 1058–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.07872.x

Moradi A., Ahmadi A., Toranjzar H., and Shams-Esfandabad B. (2022). Modeling the Habitat Suitability of Persian Leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in the Conservation Areas of Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province, Iran. Ecopersia 10, 109–119.

Moradi A., Ahmadi A., Toranjzar H., and Shams-Esfandabad B. (2024). Survey of attitudes of human local communities of conservation areas of Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province toward Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor). Rangeland Ecol. Manage. 93, 24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.rama.2023.11.003

Morrison M. L. and Mathewson H. A. (2015). Wildlife habitat conservation: Concepts, challenges and solutions (Baltimore, Maryland, USA: Johns Hopkins University press), 185.

Mwaniki M. W., Ngigi M. M., Kuria B. T. O., and Mwungu C. M. (2025). Habitat suitability modelling for the African buffaloes in Northern Kenya using an ensemble approach. Environ. Monit. Assess. 197, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10661-025-14296-9

Naderi M., Farashi A., and Erdi M. A. (2018). Persian leopard's (Panthera pardus saxicolor) unnatural mortality factors analysis in Iran. PloS One 13, e0195387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195387

Odden M., Athreya V., Rattan S., and Linnell J. D. (2014). Adaptable neighbours: movement patterns of GPS-collared leopards in human dominated landscapes in India. PloS One 9, e112044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112044

Omidi M., Kaboli M., and Karami M. (2010). Analyzing and modeling spatial distribution of leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in Kolahghazi National Park, Isfahan Province of Iran. J. Env. Sci. Tech 12, 137–148.

Parchizadeh J. and Adibi M. A. (2019). Distribution and human-caused mortality of Persian leopards Panthera pardus saxicolor in Iran, based on unpublished data and Farsi gray literature. Ecol. Evol. 9, 11972–11978. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5673

Pearson R. G., Raxworthy C. J., Nakamura M., and Townsend Peterson A. (2007). Predicting species distributions from small numbers of occurrence records: a test case using cryptic geckos in Madagascar. J. Biogeography 34, 102–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01594.x

Phillips S. J. (2017). A Brief Tutorial on Maxent (AT&T Research). Available online at: http://biodiversityinformatics.amnh.org/open_source/maxent/ (Accessed June 17, 2023).

Phillips S. J., Anderson R., and Schapire R. (2006). Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 190, 231–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026

Phillips S. J. and Dudík M. (2008). Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 31, 161–175. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-7590.2008.5203.x

Poursalem S., Amininasab S. M., Zamani N., Almasieh K., and Mardani M. (2021). Modeling the distribution and habitat suitability of Persian leopard Panthera pardus saxicolor in Southwestern Iran. Biol. Bull. 48, 319–330. doi: 10.1134/S1062359021030122

Ranjbar H., Moshtaghi M., Omouyan I., and Jamali Mansh A. (2016). Modeling the distribution of goitered gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa) in Bamu National Park using the MaxEnt entropy method. J. Anim. Environ. Res. 8, 17–24.

Rather T. A., Kumar S., and Khan J. A. (2020). Multi-scale habitat modelling and predicting change in the distribution of tiger and leopard using random forest algorithm. Sci. Rep. 10, 11473. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68167-z

Roberts D. R., Bahn V., Ciuti S., Boyce M. S., Elith J., Guillera-Arroita G., et al. (2017). Cross-validation strategies for data with temporal, spatial, hierarchical, or phylogenetic structure. Ecography 40, 913–929. doi: 10.1111/ecog.02881

Roshani, Rahaman M. H., Masroor M., Sajjad H., and Saha T. K. (2024). Assessment of habitat suitability and potential corridors for Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) in Valmiki Tiger Reserve, India, using MaxEnt model and Least-cost modeling approach. Environ. Modeling Assess. 29, 405–422. doi: 10.1007/s10666-024-09966-w

Rozhnov V. V., Pshegusov R. H., Hernandez-Blanco J. A., Chistopolova M. D., Pkhitikov A. B., Trepet S. A., et al. (2020). MaxEnt modeling for predicting suitable habitats in the North Caucasus (Russian part) for Persian leopard (P. ciscaucasica) based on GPS data from collared and released animals. Izvestiya Atmospheric Oceanic Phys. 56, 1090–1106. doi: 10.1134/S0001433820090212

Sanei A., Mousavi M., Mousivand M., and Zakaria M. (2012). “Assessment of the Persian leopard mortality rate in Iran,” in Proceedings from UMT 11th International Annual Symposium on Sustainability Science and Management (University Malaysia Terengganu, Terengganu, Malaysia), 1458–1462.

Sanei A., Teimouri A., Ahmadi Fard G., Asgarian H. R., and Alikhani M. (2020). “Introduction to the Persian Leopard national conservation and management action plan in Iran,” in Research and Management Practices for Conservation of the Persian Leopard in Iran (Springer International Publishing, Cham), 175–187. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-28003-1_8

Sarhangzadeh J., Karimian A. A., and Akbari H. (2018). Prediction leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) habitat suitability in Kouh-e-Bafgh Protected Area. J. Anim. Environ. 10, 1–8.

Serva D., Bernabò I., Cittadino V., Romano A., Cerasoli F., Biondi M., et al. (2025). Modeling habitat suitability and connectivity for the sole endemic genus of Italian vertebrate: present and future perspectives. Front. Zoology 22, 8. doi: 10.1186/s12983-025-00562-6

Shahsavarzadeh R., Hemami M. R., Farhadinia M. S., Fakheran S., and Ahmadi M. (2023). Spatially heterogeneous habitat use across distinct biogeographic regions in a wide-ranging predator, the Persian leopard. Biodiversity Conserv. 32, 2037–2053. doi: 10.1007/s10531-023-02590-2

Shams A., Nezami B., Rayehani B. S., and Shams Esfandabad. B. (2019). Climate change and its effects on Asiatic cheetah suitable habitats in center of Iran (Case study: Yazd Province). J. Anim. Environ. 11, 1–12.

Shoaee A., Gholipour M., Rezaei H., and Yarmohammadi Babrbarestani S. (2017). Assess habitat suitability Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor, Pocock 1927) based on maximum entropy method (Maxent) during the summer and fall in the National Park Tandooreh, Iran. J. Anim. Environ. 9, 21–30.

Soofi M., Ghoddousi A., Zeppenfeld T., Shokri S., Soufi M., Egli L., et al. (2019). Assessing the relationship between illegal hunting of ungulates, wild prey occurrence and livestock depredation rate by large carnivores. J. Appl. Ecol. 56, 365–374. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.13266

Soofi M., Qashqaei A. T., Mousavi M., Hadipour E., Filla M., Kiabi B. H., et al. (2022). Quantifying the relationship between prey density, livestock and illegal killing of leopards. J. Appl. Ecol. 59, 1536–1547. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.14163

Stein A. B., Athreya V., Gerngross P., Balme G., Henschel P., Karanth U., et al. (2020). Panthera pardus (amended version of 2019 assessment). IUCN Red List Threatened Species 2020. Gland, Switzerland.

Sun R., Liu K., Huang W., Wang X., Zhuang H., Wang Z., et al. (2024). Global distribution prediction and ecological conservation of basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) under integrated impacts. Global Ecol. Conserv. 56, e03310. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2024.e03310

Swanepoel L. H., Lindsey P., Somers M. J., Van Hoven W., and Dalerum F. (2013). Extent and fragmentation of suitable leopard habitat in South Africa. Anim. Conserv. 16, 41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2012.00566.x

Tavakoli M., Ahmadi M., Malekian M., and Mohammadi A. R. (2024). Assessing habitat suitability and connectivity for the Persian leopard in the Dena conservation complex. Iranian J. Appl. Ecol. 13, 41–54. doi: 10.47176/ijae.13.4.8533