- 1School of Agriculture, Biomedicine and Environment, La Trobe University, Bundoora, VIC, Australia

- 2Environmental Futures, School of Science, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, Australia

Global amphibian populations are declining, driven by a complex interplay of stressors including habitat destruction, climate change, pollutants, invasive species, and emergent diseases. Understanding the physiological response of amphibians to these stressors is critical, and hormones offer a powerful lens into their reproductive health and stress resilience. However, our knowledge of amphibian physiology and endocrinology remains limited, largely due to the lack of suitable non-invasive monitoring tools. Here, we present an innovative, non-invasive hormone monitoring method using small, temporary dermal patches. First, we evaluated six patch materials and two extraction techniques for their effectiveness in measuring corticosterone and testosterone. Our results indicate that patch performance varied depending on both the hormone type and extraction method. Second, to biologically validate this approach for monitoring dermal androgens, we monitored changes in testosterone levels in the Blue Mountains tree frog (Dryopsophus citropa) following the administration of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Dermal patches successfully detected biologically relevant increases in testosterone post-stimulation, confirming their utility for monitoring reproductive hormones. This novel technique provides a viable, non-invasive approach for assessing amphibian steroid hormones, creating new opportunities to advance amphibian physiological research, ecological monitoring, and conservation management.

Introduction

Amphibians are one of the most imperiled groups of animals. Global amphibian populations are disappearing at an alarming rate, with 41% of species listed as threatened (IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group, 2024). These declines are driven by several interacting stressors, such as habitat destruction, climate change, pollutants, invasive species, and emergent disease including chytridiomycosis, caused by the pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) (Luedtke et al., 2023). Protecting these vulnerable species is critical as they provide valuable ecosystem services and have important cultural and intrinsic value. There is urgent need for better monitoring tools to establish fundamental information about amphibian biology and support the success of conservation efforts.

Hormones play a key role in shaping animal reproduction and stress responses, both of which are critical to species survival. Furthermore, the endocrine signaling system can be hijacked by factors such as endocrine disrupting chemicals and other sources of pollution, and frogs are particularly vulnerable to these disruptions that can exacerbate species declines (Hayes et al., 2010). Unfortunately, we lack fundamental information about endocrinology in most amphibian species, in part due to the lack of appropriate, non-invasive monitoring tools (Santymire et al., 2018). Addressing this knowledge gap is crucial for improving conservation efforts, particularly for increasing reproductive output and the success of conservation breeding programs and for understanding the impacts of stressors, toxins, and disease (Park and Do, 2023).

Non-invasive hormone monitoring offers an ethical and effective alternative to traditional blood sampling methods and has proven valuable for enhancing conservation outcomes (Kumar and Umapathy, 2019; Schilling et al., 2022). Although these approaches have been relatively well developed for mammals, progress in amphibians has lagged behind (Trudeau et al., 2022). Urine is the main non-invasive substrate that has been used for frogs (Trudeau et al., 2022), but it can be difficult to obtain urine samples at the required sampling points and still requires manual restraint. Water sampling has also been used for amphibians, but requires transferring animals to a separate sampling container. Standardizing water-based measurements can be challenging and presents some logistical hurdles, including low concentrations of hormones. Fecal sampling, which is common in other vertebrates, has rarely been used in frogs because they defecate infrequently and samples can be difficult to find. Recent studies have demonstrated that glucocorticoids (GCs) can be measured reliably via dermal swabs from frogs (Santymire et al., 2018; Scheun et al., 2019). The approach of measuring hormones via dermal secretions holds great promise for non-invasive hormone monitoring in amphibians, and there are valuable opportunities to develop this method further. To date, this approach has only been used for monitoring GCs, leaving reproductive endocrinology largely unexplored. This gap presents a compelling opportunity to expand the toolkit—one that our study addresses through the development of a novel dermal patch method.

The aim of this project was to develop an innovative, non-invasive tool for measuring frog hormones using small, temporary dermal patches. Specifically, we aimed to: (i) compare the performance of different patch materials; (ii) compare two methods to extract steroid hormones from the patch; and (iii) demonstrate that dermal patches can be used to measure biologically relevant changes in hormone levels, specifically testosterone. By enabling researchers, wildlife managers, and conservation practitioners to easily and ethically monitor the stress and reproductive health of frogs, this tool will greatly contribute to our understanding of frog physiology and success of conservation breeding programs.

Materials and methods

Experiment 1: methodological validation

Experimental overview

For the methodological tests, we focused on two hormones that are most commonly used in the assessment of frog stress and reproductive physiology: corticosterone (Cort) and testosterone (T). We spiked patches with one of four different hormone concentrations and extracted them using two different extraction approaches (see below). For each hormone, we analyzed a total of 144 samples (6 material types x 4 spike concentrations x 2 extraction methods = 48 treatments, with 3 replicates of each treatment).

Patch material

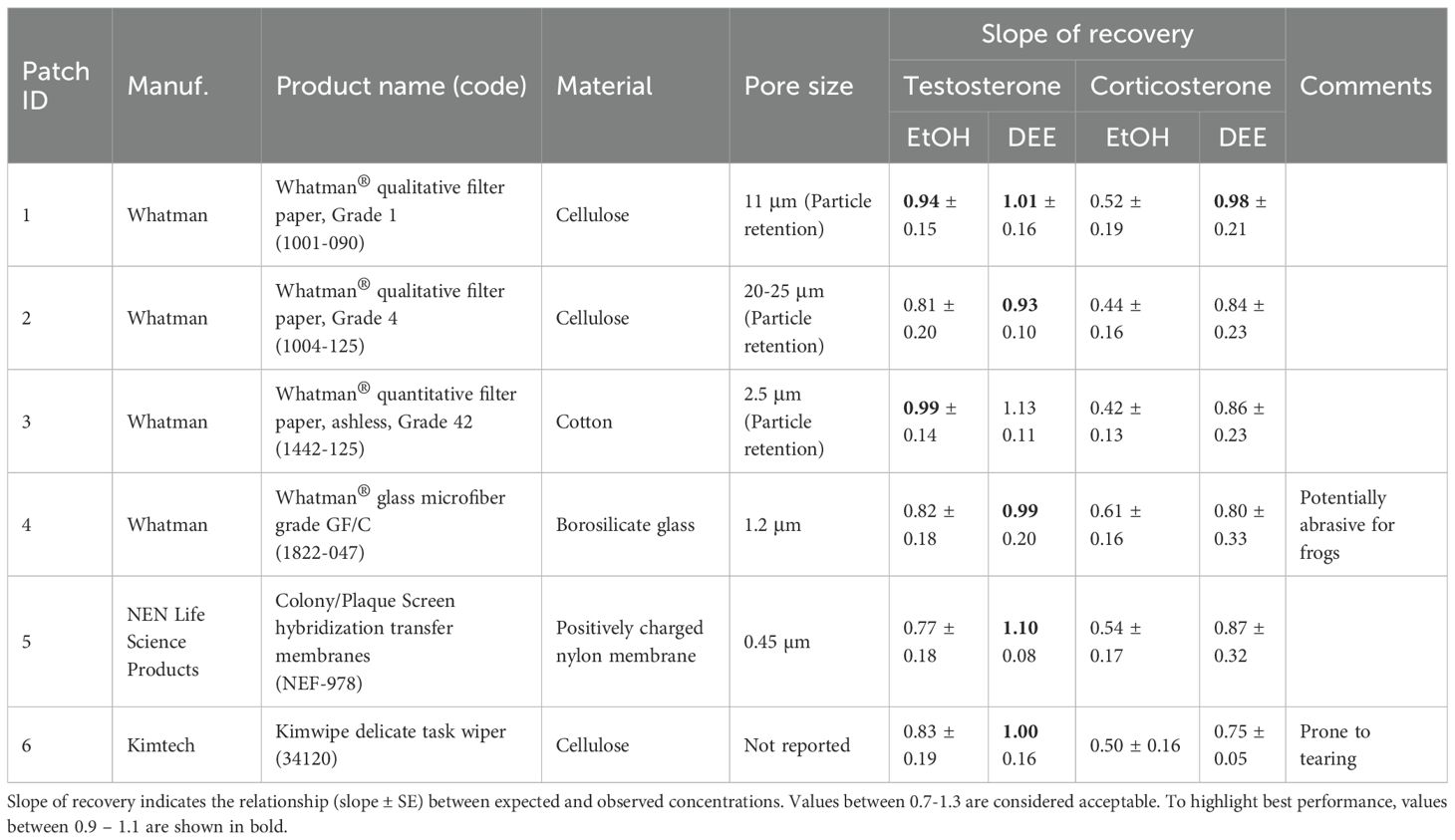

We identified six different patch materials as potential candidates for use as dermal patches, each with slightly different characteristics (Table 1). Patch size was standardized using a hole punch (6 mm diameter), which was cleaned thoroughly with 80% ethanol before and after punching discs for each patch material. Individual patches were stored in labelled 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes.

Spike-recovery test

To assess extraction efficiency and interference of the patch materials, we conducted spike-recovery trials for Cort and T. Patches were spiked with buffer (control) or with low, medium, or high concentrations of the respective hormone standards (0.1, 0.64, or 4 ng/ml). We added 10 µL of the respective solution directly onto each patch and let it dry overnight. Dried patches were stored at room temperature until extraction (<30 days).

Extraction methods

We compared two methods to extract steroid hormones from the patches. The first method was an “ethanol extraction”, which is commonly used in non-invasive hormone monitoring to extract steroid hormones from solid matrices (Palme et al., 2013). For this method, 200 µL of 80% ethanol was added to each tube containing spiked patches. Tubes were vortexed and place on a rocking shaker overnight. The following day, the patch was removed and discarded, and the extracts were stored at -20 °C until analysis.

The second method was a diethyl-ether (“DEE”) extraction, which is typically used in plasma steroid analysis (liquid: liquid extraction) to separate steroids from interfering substances (Taves et al., 2011). For the DEE extraction, 100 µL of ultrapure water was added to each tube containing the patch, followed by 1 mL of diethyl-ether. Tubes were vortexed for 30 seconds and left to stand for 5 minutes to allow phase separation. To isolate the solvent layer, tubes were placed in a -80 °C freezer for 5 minutes, freezing the aqueous portion. The upper solvent layer, containing the steroids, was transferred to a clean 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube. This procedure was then repeated a second time. The combined solvent was dried overnight. Prior to analysis, dried samples were reconstituted with 20 µL of 100% ethanol and 150 µL of assay buffer.

Hormone assays

Hormone concentrations were quantified using T and Cort enzyme immunoassays (Arbor Assays® ISWE Testosterone Mini-Kit - product # ISWE001 and Arbor Assays® ISWE Corticosterone Mini-Kit - product # ISWE007; Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). Assays were run according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates were coated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Arbor Assays, USA, A009) for the testosterone assay, and donkey anti-sheep IgG (Arbor Assays, USA, A010) for the corticosterone assay. To run the assays, plates were washed and loaded with 50 μL of standard, control, or sample, followed by 50 μL of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate and 50 μL antibody solution. Plates were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature, washed and loaded with 100 μL TMB solution. The color reaction was stopped and optical density was quantified using a 450 nm measurement filter (620 nm reference filter; SPECTROstar Nano plate reader, BMG LABTECH, Ortenberg, Germany). Inter-assay coefficients of variation for high and low controls were 8.4% and 4.2% for the testosterone assay, and 6.5% and 2.2% for the corticosterone assay. Intra-assay coefficients of variation were <10% (T: 5.9% and 4.7%; Cort: 9.9% and 8.8%) for high and low controls respectively.

Experiment 2: biological validation for testosterone

Animals

The Blue Mountains tree frog, Dryopsophus citropa is a medium-sized (47-62mm svl) tree frog species with an IUCN conservation status of ‘least concern’, though populations have declined in parts of the species’ range in southeastern Australia. On the 8th of November 2024 (between 20:00-22:00hrs), a total of eight male L. citropa were collected from a natural population located within Darkes Forest, Dharawal National Park approximately 60 km south of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Males were located by tracking their vocalizations and collecting each male by hand from its advertisement position on rocks fringing a permanent stream. All males captured were observed broadcasting advertisement calls and exhibited darkened nuptial pads, indicating that they were reproductively mature. Latex examination gloves were worn at all times during handling and changed between individuals. Immediately after capture, frogs were housed in individual ventilated plastic containers (9cm D x 5cm H), containing 10 laboratory tissues (Kimwipe, Kimtech) wetted with 25 ml of distilled water. Frogs were transported to a field station located within 20 km where they were held on an 18 °C/22 °C night/day temperature cycle and natural photoperiod.

hCG injection and patch application

At the field station, frogs were weighed to the nearest 0.01 grams and then rested for approximately 24-hours without handling. On the 10th of November, 2024 at 07:00 hours, males were individually removed from housing and a patch consisting of a 6 mm circle of sterile filter paper (Filtech 10 µm qualitative filter paper, cat no. 1893-055) was applied to the central dorsal surface (Figure 1) using sterile forceps (cleaned in 80% ethanol between applications). Patches remained on the frogs’ skin for exactly 60 seconds before being removed and placed in a prelabelled Eppendorf tube. After the patch was removed, each male was administered 20 IU/g body mass human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, Chorulon®) diluted in 100 µL of Simplified Amphibian Ringer (SAR; 113 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 3.6 mM NaHCO3). The hormone type and administration protocols used were based on previously established methods for anurans (Silla et al., 2019; Silla and Langhorne, 2022), with the specific dose chosen based on an established protocol used routinely for another Australian hylid, the Booroolong frog (Litoria booroolongensis) (Hobbs et al., 2023). Hormones were administered via subcutaneous injection into the dorsal lymph sac using ultra-fine 30-guage syringes. Following hormone administration, males were removed from housing every 2-hours for a 12-hour period for the collection of spermic urine samples via a glass microcapillary tube (Silla et al., 2019). Following spermic urine collection (Silla unpublished data) at the 6- and 12-hour time point post hormone administration, dermal patches were applied to each male according to the procedures described above. The timing of the collection was chosen to reflect basal concentrations (0 h; prior to hormone administration), peak response (6 h post hormone administration) and when concentrations were expected to start declining (12 h post hormone administration). Patches were refrigerated for 24 h before being stored at -20 °C until analysis.

Figure 1. Adult male Blue Mountains tree frog, Dryopsophus citropa with dermal patch applied. Photo courtesy of Aimee Silla.

Hormone analysis

To extract T metabolites, 100 µL of 60% ethanol was added to each tube containing the dermal patches. Tubes were vortexed and placed on a rocking shaker overnight. The following day, the patch was removed and discarded, and the extracts were stored at -20 °C until analysis.

We chose ethanol for this extraction procedure because the recovery slope between expected and observed hormone concentrations from experiment 1 fell within the acceptable range and was comparable to DEE for the selected patch type (Table 1). Ethanol offers several advantages over DEE, including lower environmental impact, shorter processing time, and greater applicability across different contexts, including field-based extractions. To minimize potential interference with the antibody, we reduced the ethanol concentration to 60%. The dermal patch extracts were analyzed using the T assay and methodology described above. The assay was biochemically validated in our lab by demonstrating parallelism between serial dilutions of a pooled sample and the standard curve. Final T concentrations are expressed as nanograms of T per patch. All samples were run on the same plate.

Data analysis

Experiment 1: methodological validation

To compare the performance of the different patch materials and extraction methods we fitted linear models using R package lme4 (Bates et al., 2015). Separate models were run for each hormone (testosterone and corticosterone). Hormone concentration was modelled as a function of the interaction between patch material and spike concentration, as well as extraction type. Hormone concentrations were log transformed prior to analysis to meet model assumptions of normality and heterogeneity of variance.

In addition, linear regression was used to evaluate the relationship between expected and observed hormone concentrations. This analysis was run separately for each patch type, hormone, and extraction method combination. A slope of 1 indicates perfect agreement between expected and observed values, indicating no interference or matrix effect. However, slopes of 0.7 – 1.3 are generally acceptable (Hunt et al., 2019).

Experiment 2: Biological validation for testosterone

To analyze changes in dermal testosterone concentrations following hCG injection, we fitted linear mixed effects models using R package lme4 (Bates et al., 2015). Testosterone concentrations were modelled as a function of sample time (hours after hormone stimulation). Animal ID was included as a random effect to account for repeated measures from individuals. Hormone concentrations were log transformed prior to analysis to meet model assumptions of normality and heterogeneity of variance.

Results

Experiment 1: methodological validation

Patch material

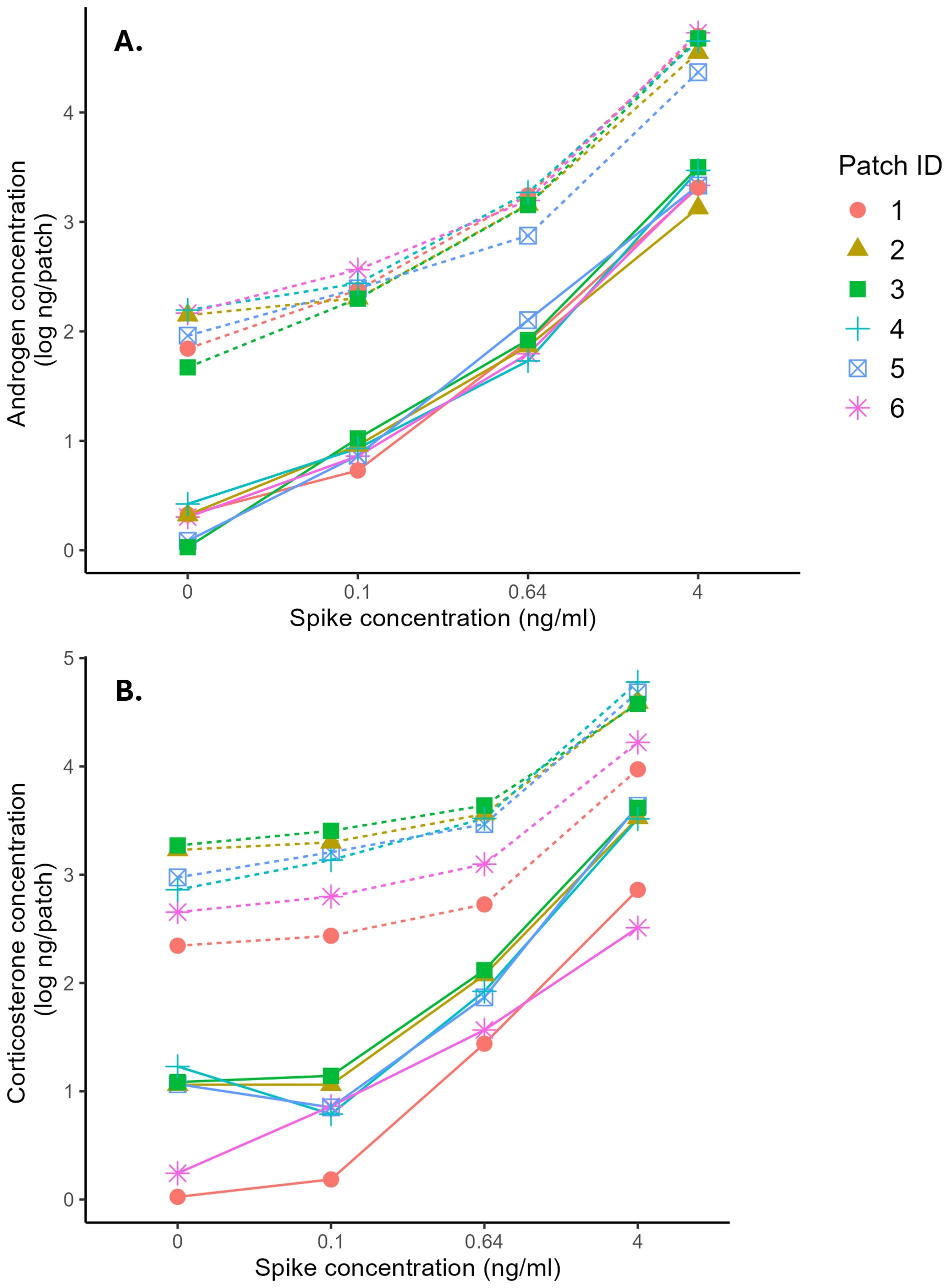

Across all patch types, measured hormone concentrations generally increased as the spike concentration increased (Figure 2). The interaction between patch material and spike concentration was not statistically significant for either hormone, indicating that there was not sufficient evidence that the slopes were significantly different across patch types, at least for the range of concentrations tested (Testosterone: F15,119 = 1.04, p = 0.42; Corticosterone: F15,115 = 0.06, p = 1.0; Figure 1). However, based on the linear regression between expected and observed concentrations for each patch type, slopes varied considerably, even if they were all generally positive (Table 1). Whatman ® Grade 1 filter paper was the most consistent, with the recovery slope closest to 1.0 across hormones and extraction methods.

Figure 2. Relationship between expected and observed androgen concentration (A) and corticosterone concentration (B) from patches extracted with ethanol (dashed line) or diethyl-ether (solid line).

Extraction method

Extraction method significantly influenced hormone recovery, with ethanol yielding significantly higher hormone concentrations for both testosterone and corticosterone (Testosterone: F1, 119 = 1147.63, p <0.001; Corticosterone: F1, 115 = 91.56, p <0.001; Figure 1). However, based on the linear regression analysis, DEE extractions consistently produced steeper slopes than ethanol extractions for both hormones (Table 1), indicating better discrimination of spike concentrations. However, the magnitude of this difference varied across patch types.

Spike recovery

We observed notable differences between the two hormones, with testosterone generally performing better on the spike-recovery test (Table 1; Figure 1). For testosterone, all recovery slopes fell between the suggested range of 0.7 – 1.3 (Hunt et al., 2019), regardless of patch type or extraction method. For corticosterone, extraction method seemed to have a bigger effect. With the ethanol extraction, the corticosterone recovery slopes were unacceptably low, with the highest slope being 0.61. However, with the DEE extraction, the slopes for all patch types were within the accepted range.

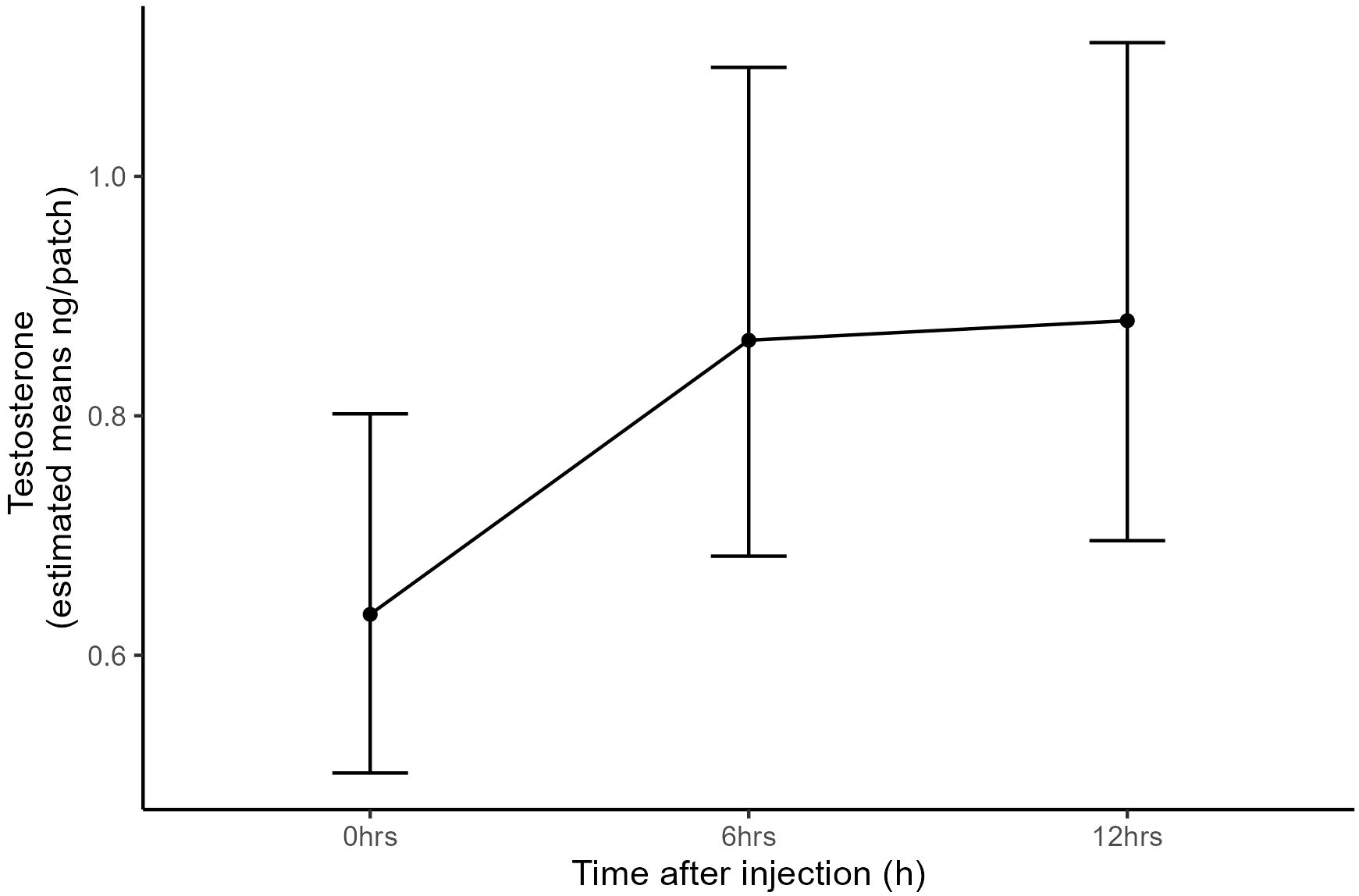

Experiment 2: biological validation for testosterone

Following hCG administration, dermal testosterone levels rose significantly above levels at time 0 (F2, 14 = 6.21, p = 0.01; Figure 3). After 6 h, concentrations were 1.4-fold higher, and at 12 h, concentrations were 1.5-fold above baseline.

Figure 3. Effect of hCG administration on dermal testosterone measurements. Data represent estimated marginal means and error bars represent standard error.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to validate non-invasive dermal patches for monitoring adrenocortical and reproductive steroids in amphibians. Although previous studies have used dermal patches to administer exogenous glucocorticoids to amphibians (Wack et al., 2010), this approach has not been used to measure endogenous steroid hormones. We present both biochemical and biological validation of this innovative technique. This method provides a valuable non-invasive tool for researchers, wildlife managers and conservation practitioners to assess stress and reproductive health in amphibians.

We evaluated six different patch materials to assess their effectiveness in extracting steroid metabolites and to determine the extent of interference introduced by the patch itself. These materials varied in composition and pore size. While hormone recovery and slope estimates differed across materials, we found no significant effect of patch type on overall extraction efficiency. However, slope analysis revealed that some patch materials offered better discrimination between spike concentrations, with performance varying by both extraction method and hormone type. Overall, Whatman Grade 1 performed the most consistently (i.e., recovery slopes closest to 1) across tests.

For testosterone analysis, all patch materials and extraction methods showed acceptable performance, with recovery slopes between 0.7 – 1.3. Therefore, patch selection may be informed by practical considerations, such as adherence to the frog and material availability, rather than analytical performance.

In contrast, the choice of extraction method significantly influenced corticosterone measurements. Whatman 1 performed best with DEE extraction, while none of the patches yielded optimal results with ethanol. Ethanol extractions produced poor recovery slopes between expected and observed corticosterone concentrations, with values falling below the acceptable range. These findings suggest that ethanol may introduce greater interference, compromising assay accuracy. Ethanol is a polar protic solvent that readily co-extracts interfering substances such as proteins, lipids and salts, which can lead to matrix effects. In contrast, no interference was detected with DEE extractions, likely due to the removal of interfering compounds during the extraction process. DEE is commonly used in plasma steroid analysis because of its ability to isolate steroids from interfering substances (Taves et al., 2011). The solvent effect was more pronounced for corticosterone than testosterone, which could be due to differences in steroid polarity and susceptibility to matrix effects. Corticosterone, being more polar, is prone to co-extraction with interfering substances and therefore more vulnerable to assay disruption (Makin et al., 2010).

Each extraction method offers distinct advantages. Ethanol extraction is faster, generates no hazardous waste, has a lower environmental impact, is safer and does not require high-energy equipment such as fume hoods or freezers (Alder et al., 2016; Prat et al., 2016). It is also more accessible in many locations and can be performed in the field, making it suitable for studies with limited resources. However, the interference introduced by the ethanol must be accounted for to ensure reliable results. Furthermore, a high percentage of alcohol can interfere with assay performance and should be taken into consideration. We found that 60% ethanol provided acceptable results for the biological validation. In contrast, DEE extractions may be preferable when minimizing interference is critical and sensitivity at low concentrations is important. DEE extraction may be best for species that produce protein-based toxins which could interfere with hormone measurements. Additionally, DEE-extracted samples can be stored at room temperature and reconstituted prior to analysis, offering logistical benefits without the need for energy-intensive storage. Analytical validation must be completed for each species and solvent.

Although dermal patches have not previously been tested, dermal swabs have been biologically validated and demonstrate that dermal secretions can be used to monitor glucocorticoid levels in amphibians (Santymire et al., 2018; Scheun et al., 2019). However, to our knowledge there has been no biological validation of dermal reproductive hormones to date. In this study, we show that dermal patches can detect biologically relevant changes in testosterone concentrations. Dryopsophus citropa stimulated with hCG showed elevated dermal testosterone levels at 6 hours and 12 hours post-stimulation compared to baseline levels, providing evidence that dermal patches are suitable for monitoring changes in reproductive steroids.

Dermal patches offer several advantages over the previously validated dermal swab technique. In docile species, this approach could improve animal welfare by eliminating the need for handling, offering a rapid, fully non-invasive method for hormone monitoring. Using a consistent patch size provides a more standardized approach for defining the sampling area, in contrast to swabbing where the swabbing area may vary between handlers. The patch method also reduces the amount of non-sample material present in the extraction (i.e., thin piece of filter paper instead of larger cotton swab and stick), potentially minimizing interference and allowing for more sensitive hormone measurements. This technique shows strong potential for broader application, though species-specific validations are necessary, and adaptations may be required to optimize the patch placement, size and duration.

The development of this approach offers a valuable opportunity to gain novel insights into amphibian biology. In particular, the validation of a non-invasive testosterone assay is an exciting step forward in advancing our understanding of reproductive biology, especially given the predominant focus on glucocorticoids in previous research. This approach can be used to map reproductive endocrinology of amphibians, optimize assisted breeding protocols for conservation breeding programs, examine reproductive status of wild animals, and identify how different factors impact reproductive biology.

Our findings demonstrate that dermal patches are a viable, non-invasive tool for monitoring biologically relevant changes in amphibian steroid hormones. We show while patch material does not greatly affect hormone measurements, the extraction method does, particularly for corticosterone. Ethanol extractions yield higher hormone concentrations, whereas DEE extractions provide better isolation of steroid hormones from interfering substances. Importantly, our validation of dermal testosterone levels following hCG stimulation confirms the suitability of this technique for monitoring reproductive hormones. Expanding the scope to include a broader range of hormone profiles (e.g. testing estrogen and progesterone), as well as conducting multi-species validations and field trials, will further demonstrate the potential of this innovative tool in advancing ecological monitoring and conservation management of amphibians.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: The data presented in the study are deposited in the Figshare data repository, available at doi: 10.26181/30689984.

Ethics statement

Blue Mountains tree frogs were collected under NSW Department of Planning and Environment’s Scientific Licence SL102771. Experimental procedures involving these study animals were approved by the University of Wollongong’s Animal Ethics Committee, protocol number AEPR231. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. EN: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. KF: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the La Trobe University Rapid Synergy grant awarded to KF and by the Australian Research Council, Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE210100812) awarded to AS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Professor Phillip Byrne during field collections of the Blue Mountains tree frogs used in the present study. Thanks also to Ian LaPat for being the catalyst for this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alder C. M., Hayler J. D., Henderson R. K., Redman A. M., Shukla L., Shuster L. E., et al. (2016). Updating and further expanding GSK’s solvent sustainability guide. Green Chem. 18, 3879–3890. doi: 10.1039/C6GC00611F

Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., and Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Software 67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Hayes T. B., Khoury V., Narayan A., Nazir M., Park A., Brown T., et al. (2010). Atrazine induces complete feminization and chemical castration in male African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 4612–4617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909519107

Hobbs R. J., Upton R., Calatayud N. E., Silla A. J., Daly J., McFadden M. S., et al. (2023). Cryopreservation cooling rate impacts post-thaw sperm motility and survival in Litoria booroolongensis. Animals 13, 3014. doi: 10.3390/ani13193014

Hunt K. E., Robbins J., Buck C. L., Bérubé M., and Rolland R. M. (2019). Evaluation of fecal hormones for noninvasive research on reproduction and stress in humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 280, 24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2019.04.004

IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2024). Amphibian conservation action plan: A status review and roadmap for global amphibian conservation. Eds. Wren S., Borzée A., Marcec-Greaves R., and Angulo A. (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature). doi: 10.2305/QWVH2717

Kumar V. and Umapathy G. (2019). Non-invasive monitoring of steroid hormones in wildlife for conservation and management of endangered species—A review. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 57, 307–314.

Luedtke J. A., Chanson J., Neam K., Hobin L., Maciel A. O., Catenazzi A., et al. (2023). Ongoing declines for the world’s amphibians in the face of emerging threats. Nature 622, 308–314. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06578-4

Makin H. L. J., Honour J. W., Shackleton C. H. L., and Griffiths W. J. (2010). “General methods for the extraction, purification, and measurement of steroids by chromatography and mass spectrometry,” in Steroid Analysis. Eds. Makin H. L. J. and Gower D. B. (Springer Netherlands), 163–282. doi: 10.1023/b135931_3

Palme R., Touma C., Arias N., Dominchin M. F., and Lepschy M. (2013). Steroid extraction: Get the best out of faecal samples. Veterinary Med. Austria 100, 238–246.

Park J.-K. and Do Y. (2023). Current state of conservation physiology for amphibians: major research topics and physiological parameters. Animals 13, 3162. doi: 10.3390/ani13203162

Prat D., Wells A., Hayler J., Sneddon H., McElroy C. R., Abou-Shehada S., et al. (2016). CHEM21 selection guide of classical- and less classical-solvents. Green Chem. 18, 288–296. doi: 10.1039/C5GC01008J

Santymire R. M., Manjerovic M. B., and Sacerdote-Velat A. (2018). A novel method for the measurement of glucocorticoids in dermal secretions of amphibians. Conserv. Physiol. 6:coy008. doi: 10.1093/conphys/coy008

Scheun J., Greeff D., Medger K., and Ganswindt A. (2019). Validating the use of dermal secretion as a matrix for monitoring glucocorticoid concentrations in African amphibian species. Conserv. Physiol. 7, coz022. doi: 10.1093/conphys/coz022

Schilling A.-K., Mazzamuto M. V., and Romeo C. (2022). A review of non-invasive sampling in wildlife disease and health research: what’s new? Animals 12, 1719. doi: 10.3390/ani12131719

Silla A. J. and Langhorne C. J. (2022). “Protocols for hormonally induced spermiation, and the cold storage, activation, and assessment of amphibian sperm,” in Reproductive Technologies and Biobanking for the Conservation of Amphibians (Melbourne, Australia: Csiro Publishing).

Silla A. J., McFadden M. S., and Byrne P. G. (2019). Hormone-induced sperm-release in the critically endangered Booroolong frog (Litoria booroolongensis): Effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone and human chorionic gonadotropin. Conserv. Physiol. 7:coy080. doi: 10.1093/conphys/coy080

Taves M. D., Ma C., Heimovics S. A., Saldanha C. J., and Soma K. K. (2011). Measurement of steroid concentrations in brain tissue: methodological considerations. Front. Endocrinol. 2. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2011.00039

Trudeau V., Raven B., Pahuja H., and Narayan E. (2022). “Hormonal control of amphibian reproduction,” in Reproductive Technologies and Biobanking for the Conservation of Amphibians (Melbourne, Australia: CSIRO Publishing), 49–68.

Keywords: non-invasive, androgen, steroid, hormone, amphibian, endocrinology, conservation physiology

Citation: Dimovski AM, Silla AJ, Nimmo E and Fanson KV (2025) Validation of dermal patches as a non-invasive tool for monitoring amphibian steroid hormones. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6:1700943. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1700943

Received: 08 September 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025; Revised: 10 November 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Elizabeth W. Freeman, George Mason University, United StatesReviewed by:

Lara Metrione, South-East Zoo Alliance for Reproduction & Conservation (SEZARC), United StatesSaeid Panahi Hassan Barough, Texas State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Dimovski, Silla, Nimmo and Fanson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alicia M. Dimovski, QS5EaW1vdnNraUBsYXRyb2JlLmVkdS5hdQ==

Alicia M. Dimovski

Alicia M. Dimovski Aimee J. Silla

Aimee J. Silla Emily Nimmo1

Emily Nimmo1 Kerry V. Fanson

Kerry V. Fanson