- 1Science and Conservation Department, Zoomarine Algarve, Albufeira, Portugal

- 2IUCN SSC Center for Species Survival Behavior Change, Albufeira, Portugal

Background: Efforts to stem the species extinction crisis have been hampered by lack of funding. While public investment is key, private donations play an important role in wildlife conservation.

Objective: This study investigated whether persuasion techniques in bird show scripts could increase pro-conservation behavior at Zoomarine Algarve.

Methods: An initial exploratory study compared control and modified tropical bird show scripts using three persuasion strategies (“identifiable victim”, “anchoring effect”, and “bandwagon effect”), measured by conservation bracelet sales. The main study then focused on the “identifiable victim” effect, involving 116 sampling days in two conditions during summer 2023, with 148,545 visitors.

Results: The exploratory study showed the modified script unexpectedly decreased sales. The main study found no significant difference in bracelet sales between conditions (Z = -.60, p = .55).

Conclusions: This research suggests complexities of applying persuasion techniques in field experiments and underscores the need for proper evaluation for informed decisions. The study provides insights into communication barriers and factors influencing conservation engagement in zoos, underlining the importance of communicating null results for advancing scientific understanding.

1 Introduction

Zoos and aquariums serve as active sources of funding for conservation projects, either through internal operational initiatives or by directly allocating funds from their budgets (Ripple et al., 2021; Gusset and Dick, 2011; Miranda et al., 2023). To nudge the audience to contribute to conservation projects through private donations, many zoos employ carefully crafted appeals through compelling and impactful narratives, using various communication strategies, including creating urgency, personalizing causes through individual stories, and showcasing support from credible public figures (Mitchell and Clark, 2021; Spears, 2002; Hibbert, 2016).

An example of these proxy behaviors is encouraging people to purchase products or participate in events where some or all the proceeds goes towards wildlife conservation.

1.1 Zoos as platforms for conservation engagement

In an increasingly nature-disconnected urban setting, zoos and aquariums play a crucial role in fostering awareness of nature conservation and sustainability (Miller et al., 2013; Packer and Ballantyne, 2010). Through animal demonstrations, habitat displays, and educational programs, these institutions seek to heighten visitor awareness of pressing wildlife challenges while sharing success stories that highlight conservation achievements (Miranda et al., 2023; Spooner et al., 2021). Animal demonstrations commonly use narrative strategies aimed at captivating visitors and fostering connections with wildlife (EAZA, 2022), often through personalizing individual animals (Newberry et al., 2017) and conveying themes about conservation challenges and successes (Mann-Lang et al., 2016).

Beyond engaging audiences, some animal demonstrations are also linked to fundraising efforts for conservation projects by involving proxy behaviors to enhance engagement (Baumeister and Finkel, 2010). However, the effectiveness of such initiatives depends critically on understanding the social-psychological processes underlying visitor decision-making, including how social proof (the tendency to follow others’ actions) influences behavioral choices (Goldstein et al., 2008), how cognitive load (the mental effort required to process information) affects message processing (Lavie et al., 2004), and how perceived authenticity (the believability and genuineness of the message) shapes trust and engagement with conservation appeals (Saffran et al., 2020). Understanding these psychological mechanisms is essential for designing effective conservation communication strategies in zoo settings.

1.2 Persuasion techniques relevant to this study

Three persuasion techniques are particularly relevant to conservation fundraising in zoo contexts. First described by Tversky and Kahneman (1974), the anchoring effect refers to when initial information (the anchor) influences subsequent judgements or decisions. Once an anchor is established, people tend to adjust their estimates or valuations insufficiently away from it, even when the anchor is arbitrary or irrelevant. Even when the anchor is not directly related to a specific theme, it may significantly influence how people evaluate and decide about it. This effect can distort perception, leading individuals to base their decisions around the initial anchor. The anchor creates a reference point that shapes perceptions of what is appropriate, reasonable, or typical. For instance, Mackay et al. (2018) applied this principle in fisheries conservation by presenting fishermen with large reference fish sizes as anchors, which successfully discouraged retention of undersized fish and encouraged targeting of larger, reproductively viable fish due to their reproductive viability.

A second technique, closely linked to social proof or herd mentality, is the bandwagon effect (Leibenstein, 1950) which explores the human tendency to follow popular actions or opinions. Persuasion will take place when an individual is encouraged to adopt an idea or behavior because many others seem to have already done so. The underlying idea is that if others have done it, it must be advantageous for the message recipient to adhere to the idea, thereby encouraging others to follow suit (Bindra et al., 2022). In this context, Goldstein et al. (2008) conducted two field experiments to assess the impact of signage encouraging hotel guests to engage in an environmental conservation initiative. They discovered that using descriptive norms in their appeals (such as “the majority of guests reuse their towels”) was more successful than the conventional methods employed by hotels that solely emphasized environmental protection. This was a clear demonstration of the bandwagon effect, where stating the behavior of the ‘crowd’ influenced the behavior of the hotel guests.

Lastly, the identifiable victim effect, initially identified by Thomas Schelling (1968, as cited in Small, 2015), suggests that people tend to be more emotionally responsive and generous in response to the suffering of an identifiable individual compared to an unknown person or statistical data. This effect underscores individuals’ tendency to feel greater empathy and willingness to help when they can relate to or personalize the challenging situation of a single identifiable person in need (Jenni and Loewenstein, 1997). A considerable body of research has already shown the effectiveness of the identifiable victim effect in influencing charitable behavior (for a review, see Small, 2015). For example, Small and Loewenstein (2003) found that people were more willing to compensate others who had lost money when previously identified than when they had not. This suggests that knowing the victim beforehand, even without personal information, increases people’s willingness to help. In the second experiment, they found that people contributed more to a charity when their contributions would benefit a family already selected from a list than when told the family would be selected later. Therefore, it is understandable that many fundraising campaigns exploit this technique with positive outcomes (Lee and Feeley, 2016).

However, while these persuasion techniques have been widely studied in various fields, their application to wildlife conservation is less established. Some studies, such as Mackay et al. (2018), have demonstrated success using the anchoring effect in fisheries management. To our knowledge, not many studies have explored this technique within the context of biodiversity conservation, especially with the use of non-human animals as focus (e.g., Thomas-Walters and Raihani, 2017; Perrault et al., 2015; Markowitz et al., 2013; Hart, 2011; Smith et al., 2013). A recent study by Thomas-Walters and Raihani (2017), one of the first to examine this effect in the context of donations to biodiversity conservation, presented participants with either individual identifiable animals or groups of three animals (with one in comparable pose to the solo individual) and found participants did not donate more to individual beneficiaries than to groups. This gap in the literature – and the mixed evidence regarding the applicability of the identifiable victim effect to non-human species – underscores the need for further empirical investigation in real-world conservation settings.

1.3 Study objectives

This real-world study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of integrating specific persuasion techniques into tropical bird show scripts to increase the likelihood of visitors buying conservation bracelets.

The present work comprises two sequential studies: an exploratory one aimed at pilot-testing the experimental design, followed by the main research, which was streamlined and used a single persuasion technique to influence the pro-conservation behavior of zoo visitors.

2 Methods

2.1 Study site and context

Research was conducted at Zoomarine Algarve, which offers two distinct daily shows featuring tropical birds (‘Flying Colors’ and ‘Magic Rainbow’), each lasting between 15 to 20 minutes with seating capacities of approximately 900 (Flying Colors) and 120 (Magic Rainbow) and occurring twice a day throughout the sampling period. During these shows, the trainer on stage appeals to the audience to purchase a bracelet that directly supports a conservation project (in this context, supporting the World Parrot Trust (WPT)) (see Figure 1 for a photo of the venues; see Supplementary Table S1 for the list of bird species included in each show).

The script for the Flying Colors show is set within a storytelling context, featuring the main character as a relaxed tourist exploring a jungle environment, oblivious to their environmentally unfriendly actions. Throughout the story, a jungle inhabitant will lead him towards a new mindset, aligning with nature and promoting respect for all living beings. The Magic Rainbow show takes place in a more informal setting (at the artificial beach in the park), where birds fly freely over the visitors and land on a structure/stage. Here, a trainer presents the species, highlighting their features, and discussing conservation threats.

Both shows include a highlighted moment in the scripts (approximately 5 minutes in duration) where a bracelet is either handed to a volunteer on stage (a child from the audience) (Flying Colors) or actively showcased by the trainer wearing the bracelet on their wrist (Magic Rainbow). During this moment, the scripts, voiced by the trainer, actively emphasize the possibility of purchase by the entire audience, with the proceeds going to WPT. In the Flying Colors show, this moment is further accompanied by visual emphasis (through a giant screen on stage) on the work of WPT (see Supplementary File 1 for the full original scripts of both shows).

2.2 Exploratory study

2.2.1 Design and procedure

The exploratory study tested three persuasion strategies (identifiable victim, anchor effect, and bandwagon effect) integrated into show scripts. These three techniques were chosen for their ability to be included in the current script without altering the narrative or operational dynamics, thus easing acceptance from the trainers’ perspective. We compared original condition (unmodified scripts) with adjusted condition (scripts incorporating all three techniques). The original condition scripts had been refined through daily field experience to maximize visitor engagement and donation appeal, based on audience response and trainer feedback before experimental testing began. The adjusted condition scripts represented experimental departures from this business-as-usual baseline, enabling comparative analysis of intervention impacts.

This study took place between mid-June and mid-September 2022, over 88 sampling days (43 original condition, 45 adjusted condition). Visitors were primarily families, with negligible organized groups. Each condition was applied for full days with no mixing of conditions, and condition assignment was randomly determined using the True Random Number Generator at Random.org. Historical analysis confirmed that bracelet sales showed no significant variation across days of the week during this period (Kruskal-Wallis test: H(6) = 5.08, p = .53, comparing 2019–2021 data).

The bracelets were always available in the zoo’s shops, regardless of the experimental conditions, highlighting the relevance of strategic changes to the scripts. By conducting this study in a natural setting, the researchers recognized the inevitable presence of possible confounding variables. This approach emphasized the ecological validity and practical relevance of field research in raising funds for conservation.

2.2.2 Script modifications

The adjusted condition (see Supplementary Table S2 for the relevant script excerpts) included:

- Anchoring + Bandwagon effect: “Last year, through donations of our visitors, we helped protect these birds with more than €4,000! But this year we want to go further. Can we count on your help?”

- Identifiable victim: Specific mention of individual birds by name and species (e.g., “Goiaba, this beautiful blue-throated macaw”)

2.2.3 Dependent variable

The daily dependent variable was defined as the sum of the WPT bracelets sold on a given day divided by the number of visitors who attended those shows on that day. For each bracelet sold (3€), the Trust receives 1.85€. The remaining amount is the cost of production and delivery, and no profit was made by Zoomarine Algarve. Although visitors can repeat any of the shows throughout the day, such behavior is unlikely, since the range of activities and parallel shows on offer to visitors is very high. This leads to visitors choosing not to repeat shows, as previously described by the park management through internal visitor behavior studies.

2.3 Main study

Based on the exploratory study findings that showed decreased bracelet sales when multiple persuasion techniques were combined, the main study was designed to test a single intervention. This negative impact observed in the adjusted condition led to a reassessment of the study design, leading to a strategic change in the main research. We thus opted for assigning only one persuasion strategy to the main study, to simplify the message and avoid some of the confounding variables identified earlier.

Conducted one year later (June 15 to September 15, 2023), this study focused exclusively on the “identifiable victim” effect to reduce cognitive load and isolate the specific impact of individual animal identification on conservation behavior. This choice was partly due to the ease of highlighting an animal in the shows’ narratives. On the other hand, it helped to reduce the possible cognitive load to the visitor, as the scripts were slightly shorter, closer to the original ones. The procedure remained similar to the exploratory approach.

In this main study, we sought to validate the following research hypothesis: the inclusion of the “identifiable victim” effect (adjusted condition) will lead to greater emotional engagement and will lead the audience to seek more conservation support bracelets when compared to the original condition (see Supplementary File 2 for the full original scripts of both shows).

2.3.1 Design and procedure

Conducted during summer 2023 over 116 sampling days (58 per condition) with 148,545 total visitors, this study simplified messaging to reduce cognitive load and potential confounding variables.

To reinforce the “identifiable victim” effect on stage, defined here as adjusted condition, the bird’s physical presence near the trainer was highlighted by mentioning the bird’s name. In the Flying Colors show, the bird flew directly to the trainer’s hand. In the Magic Rainbow show, the bird flew to the nearest structure (perch) to the trainer. The choice of focal species (Blue-throated Macaw and Hyacinth Macaw) for the ‘identifiable victim’ was based on the balance between handling (birds comfortable with flying straight into the trainer’s hand) and conservation status. No spillover effects were expected since the time between both studies was 1 year and, according to the park’s management, the return rate of visitors is over 2 years.

2.3.2 Script modifications

The adjusted condition highlighted specific birds by name and physical presence:

- Flying Colors: “This is Goiaba (presence of bird in trainer’s hand), a blue-throated macaw. This and other species are endangered birds. Shall we help them?”

- Magic Rainbow: “Proceeds will be directly helping other birds like Papaia here, a Hyacinth Macaw, and many others threatened with extinction. Shall we help them?”

Supplementary Table S3 highlights the excerpts of the scripts, depending on each condition.

2.4 Data analysis

2.4.1 Exploratory study

A Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted, which indicated that the distribution of the dependent variable significantly deviated from normality in the adjusted condition (W (45) = .90, p = .01) (original condition: W (43) = .95, p = .07). Examination of Normal Q-Q plots also verified the lack of normality. Based on these results, the Mann-Whitney U test was chosen, as the data assumed independent samples with similar distribution shapes and was suitable for continuous data. Median with interquartile range was used to summarize the variable under study.

2.4.2 Main study

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test indicated that the distribution of the variable under study showed evidence of non-normality in the original condition (D (58) = .14, p = .01; adjusted condition: D (58) = .11, p = .09). Similarly to the exploratory study, a Mann-Whitney U test was used for the comparison between conditions, with the median and interquartile range used to summarize the variable under study.

2.5 Research ethics

Prior research approval was obtained from Zoomarine’s Science Committee (ZM_2022ID01). Given the minimal risk nature of the behavioral observation study and the impracticality of obtaining individual consent from zoo visitors, a waiver of written informed consent was granted. All procedures complied with American Psychological Association ethical principles and national data protection regulations.

3 Results

3.1 Exploratory study results

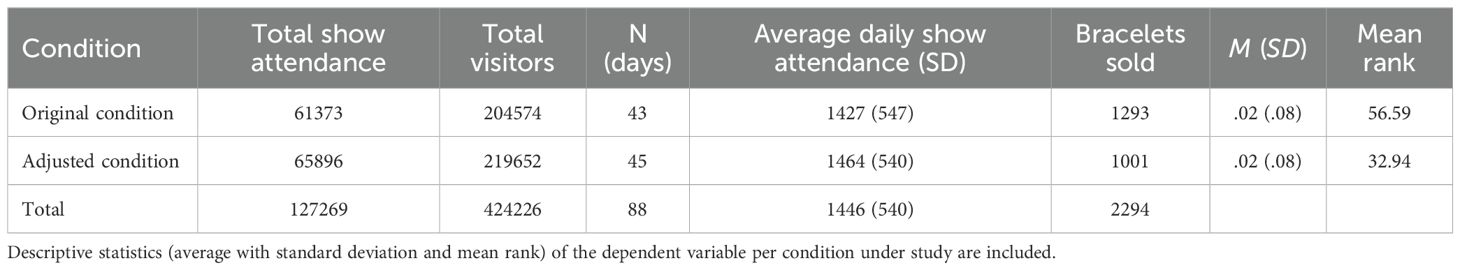

Both conditions had similar attendance throughout the study (Table 1). Contrary to our initial hypothesis, the total number of bracelets sold in the adjusted condition accounted for approximately 77% of those sold using the original scripts (Table 1).

Table 1. Total number of bracelets, sampling days, total zoo visitors, and visitors attending the shows across the study period, by condition.

A Mann-Whitney U test indicated significant differences between conditions (Z = -4.35, p <.001, r = -.46), with visitors’ behavior favoring the original condition. Bracelet sales include purchases by both show attendees and non-attendees, limiting causal attribution.

The adjusted condition showed significantly lower bracelet sales than the original condition (Z = -4.35, p <.001, r = -.46), contrary to our initial expectations.

3.2 Main study results

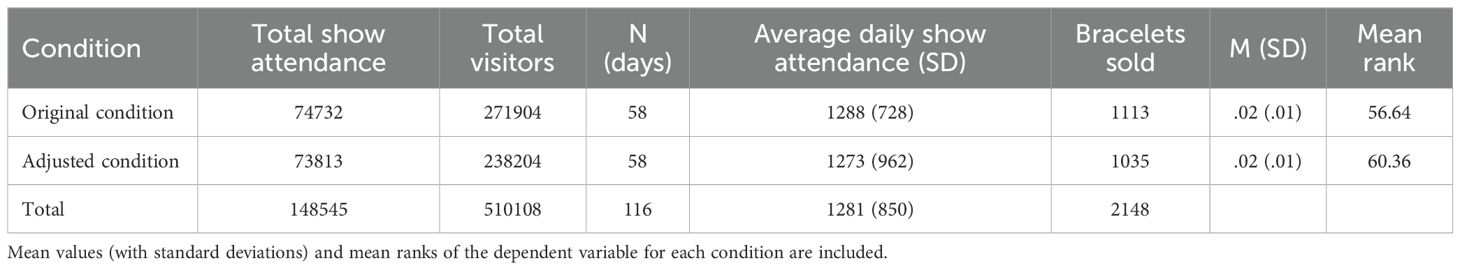

This study was conducted over a total of 116 sampling days, with 58 days allocated to original condition and 58 days to adjusted condition, during the summer period of 2023 (June to September). Similarly to the exploratory approach, each condition was applied for a full day, meaning there was no mixing of conditions on any of the sampling days. It also followed a similar approach to the exploratory approach regarding the random distribution of each condition throughout the sampling period. Mean attendance per condition was similar throughout the study (Table 2).

Table 2. Total number of bracelets, sampling days, total zoo visitors, and visitors attending the shows across the study period, by condition.

A total of 148,545 visitors were exposed to the different conditions under study, with approximately 52% corresponding to the original condition and the remaining 48% to the adjusted condition.

The Mann-Whitney U test indicated no significant difference between conditions (Z = -.60, p = .55, r = -.05), refuting our research hypothesis that the identifiable victim effect would increase pro-conservation behavior. Bracelet sales include purchases by both show attendees and non-attendees, limiting causal attribution.

A similar number of bracelets per condition was sold throughout the study (Z = -.60, p = .55, r = -.05), with a total accumulated count of 2,148 bracelets.

4 Discussion

4.1 Context and overview

Our main study aimed to increase the visitors’ pro-conservation behavior with a single persuasion effect (identifiable victim), by including an identifiable individual of a threatened bird species in the trainer’s script and physical space. This approach was grounded in substantial evidence that the identifiable victim effect increases charitable giving in human contexts (Small, 2015) and sought to test whether this effect would translate to conservation behavior when applied to living animals in zoo demonstrations. Contrary to expectations, the main study found no significant difference in bracelet sales between conditions (Z = -.60, p = .55), while the exploratory study showed decreased sales with multiple persuasion techniques combined (Z = -4.35, p <.001). This null result is consistent with the findings of Thomas-Walters and Raihani (2017), who similarly found no increase in donations when presenting individual identifiable animals versus groups. Their operationalization of the ‘identifiable victim’ (singular vs. group) may not fully capture the victimhood element essential to this technique—a limitation that may also apply to our own study, where we used visibly healthy, well-cared-for captive animals. This convergence of null and negative findings warrants careful examination of both theoretical assumptions and methodological factors that may have influenced our results.

4.2 Interpreting the null results

Exploratory studies play a key role in refining research methodologies and tools, allowing us to test the feasibility and effectiveness of the research instruments, identify potential pitfalls and assess the time and effort required for data collection and analysis. In addition, they can reveal unexpected ideas or challenges, allowing us to adjust hypotheses or research design accordingly. Despite the complexity inherent in field studies with multiple confounding variables, this research suggests that the proposed change may have led to an unexpected impact on the results. Since both conditions shared all characteristics except for the inclusion of the three persuasion techniques (identifiable victim, bandwagon effect, and anchoring), we are led to believe that the alternative script resulted in a less appealing and perhaps confusing narrative from the audience’s perspective. As the changes made in the adjusted condition generated slightly longer scripts, it might have also led to a greater cognitive load among the audience, precisely at the most relevant moment for the investigation. According to the Load Theory of Selective Attention (Lavie et al., 2004), the size of the cognitive load affects selective attention capacity: the higher the cognitive load, the poorer the performance of selective attention, meaning less mental availability for the audience to follow the narrative at the most critical moment for this study.

Looking at the main study’s results, we did not find any increase in demand for bracelets with the adjusted script, thus not validating our research hypothesis. Nevertheless, and opposed to the results from the exploratory study, we did not find a significant decrease in purchasing between conditions. This absence of effect is consistent with the study by Thomas-Walters and Raihani (2017) mentioned earlier. It is, nevertheless, important to note that the experimental design of the present study, involving two different bird shows (Flying Colors and Magic Rainbow) and two species of birds used as ‘identifiable victims’ (Blue-throated Macaw and Hyacinth Macaw), may have introduced additional unexpected variables. Although we have not found significant differences between conditions overall, future analyses could consider the study as a 2x2 design (type of script x show/bird species) to explore any interactions or potential differences.

Null results can still play a crucial role in avoiding redundancy in future research paths, while at the same time stimulating collective progress. A recent systematic review of behavioral interventions in a biodiversity conservation context found that the vast majority published studies reported positive effects, whilst only a few reported negative or mixed effects (Thomas-Walters et al., 2023). This lack of reporting non-positive effects can contribute to a bias in the literature, potentially leading to incorrect assumptions or ineffective strategies being pursued (Page et al., 2022; Munafò and Neill, 2016).

4.3 Methodological considerations

The decision to test various persuasion techniques together in the exploratory study was motivated by the desire to maximize the potential for behavior change. However, this approach has made it difficult to isolate the effect of each individual technique. Testing each technique separately would have given us a clearer perspective on their individual efficacy, although this may not be as applicable in real-world contexts.

Furthermore, the use of these techniques has revealed some limitations. For example, using an aggregate donation amount (4,000€) as an anchor may not have effectively translated into individual decision-making about purchasing a 3€ bracelet. Similarly, this aggregate amount, when considered in relation to the overall number of visitors, may have unintentionally contributed to a non-participation norm, potentially undermining the intended bandwagon effect. This implementation failure means we cannot conclude that the anchoring effect itself is ineffective in zoo conservation contexts - only that our particular operationalization, which conflated anchoring with social proof elements, was flawed. Testing each technique separately would have provided clearer insights, though this may be less applicable to real-world contexts where multiple persuasion elements naturally co-occur. A narrative focused on the individual contribution of each visitor (rather than the aggregate) could more effectively leverage the fundamentals of both effects being tested.

The implementation of the identifiable victim effect, although novel in its use of living animals, may have been less impactful than expected. Asking visitors to help “other birds such as” those they had seen, rather than the specific individuals present (who were clearly well-protected and cared for), may have diluted this effect. Importantly, our null results do not necessarily indicate that the identifiable victim effect is ineffective in conservation contexts broadly. They may rather suggest that the specific implementation using visibly healthy, well-cared-for captive animals cannot effectively establish the ‘victim’ framing essential to this technique. The cognitive dissonance created by asking visitors to help animals that appear thriving may fundamentally undermine the mechanism. Future research should test whether the identifiable victim effect works when using images or videos of wild animals clearly in distress or need.

Additionally, variation in script delivery or trainer engagement across performances could have introduced uncontrolled differences between conditions. As no formal monitoring of implementation fidelity was conducted, inconsistencies in message timing, emphasis, or delivery style may have affected visitor responses. Ensuring and documenting high consistency in trainer delivery, potentially via audio/video recording or checklist observation, is recommended for future intervention studies.

By altering the script composition and without the organic flow that enables more genuine dialogue from the trainers, might have led to a lack of perceived authenticity from the audience. The influence of authenticity on message perception is well known (Burton, 2020) and is indeed crucial in how the message is received and in the perception of the communicator’s trustworthiness (Saffran et al., 2020). When the message is not perceived as authentic, the recipient might discredit it, rendering the appeal ineffective, thus partly justifying the observed decrease in our results. To overcome this, it is recommended that in future studies, the scripts for any conditions under study be thoroughly rehearsed beforehand, as this may lead to a more natural delivery, thereby enhancing the authenticity of the message.

Another aspect that may have affected the receptivity of the adjusted condition is the fact that these scripts did not mention the process of buying the bracelet but rather the opportunity to donate in exchange for the bracelet. This seemingly simple word change might have led to confusion in interpretation, conditioning the audience’s behavior. Mentioning buying, as it is a daily established behavior, has a more streamlined and direct mental processing than appealing for a donation in exchange for the bracelet. Routine actions, such as buying a product, are executed with minimal conscious consideration and are frequently automatic, whereas less frequent activities, like making donations, may necessitate more intentional thought and decision-making (Martin and Morich, 2011; Fiske and Taylor, 1991; Johnson et al., 1988). This additional cognitive processing may have created a barrier to action, particularly in the brief time frame of the show’s fundraising appeal. The framing of the transaction itself—independent of the persuasion techniques being tested—may have inadvertently reduced engagement.

Finally, it is also important to consider the context of this study. Although the bird shows lasted around 15 to 20 minutes, the pitch for the expected effect was relatively brief, lasting only about 5 minutes. Moreover, the sale of bracelets was not limited to the bird show participants but was available to all zoo visitors. Future studies could benefit from implementing direct sales of bracelets immediately after the shows and exclusively on-site (at the stadiums). This approach would allow for a more effective evaluation of the effect under study.

4.4 Implications for conservation fundraising

Behavior change studies based on field experiments are fundamental to evaluating the effectiveness of small changes in programs and interventions. The implementation of subtle adjustments in strategic programs with the belief that these changes will have a positive impact or, at the very least, will not cause harm, can be misleading. As suggested by this research, without rigorous and systematic evaluation of adjustments in real-world contexts, one could easily overlook whether implemented changes produce the desired results or inadvertently have negative consequences.

Although our results were null, they provide valuable insights into the complexities of behavior change interventions for wildlife fundraising. These findings highlight the need for careful consideration of how persuasion techniques are implemented and interpreted in specific contexts, particularly when dealing with non-human species.

4.5 Future research opportunities

Looking ahead, conducting this research allows for a critical retrospective look to identify future research opportunities.

While animal demonstrations typically address biodiversity, animal behaviors, and biological adaptations (Kimble, 2014; Spooner et al., 2021), our intervention focused specifically on the fundraising appeal portion. The brief duration of this appeal (approximately 5 minutes) within shows lasting 15–20 minutes may have limited its effectiveness, particularly given that demonstrations often need to balance entertainment, education, and calls to action (Price et al., 2015; Alba et al., 2017). Future research might consider how to better integrate conservation appeals throughout the entire presentation, allowing for a more natural build-up of emotional connection before the fundraising request.

Furthermore, while many zoos successfully use demonstrations to encourage audience engagement in conservation initiatives, our results suggest that the method of delivery and timing of such appeals may be crucial factors. The challenge lies in maintaining the authenticity and educational value of the presentation while effectively incorporating fundraising elements.

Considering the potential influence of cognitive load on the perception of the final conservation message, future research could focus on including the call to action at earlier stages of the show, thus testing the possibility of cognitive fatigue. Following on from the Thomas-Walters and Raihani (2017) study, testing the effect of using charismatic vs non-charismatic species on donations could yield some further insights.

Another aspect to consider is studying the impact of using specimens for the “identifiable victim” whose appearance does not project beauty and health (attributes not often associated with the concept of “victim”). Alternatively, if opting for such individuals, testing whether the use of accompanying videos or images showing their distress can influence the perception of the overall message would be valuable. Finally, exploring alternative communication strategies, such as one that has happened in the past with WPT, which emphasizes matching donations from an external funder, could be interesting for studying the impact on the visitors’ willingness to donate for conservation.

4.6 Study limitations

Several methodological limitations warrant consideration when interpreting these findings. The study’s statistical power may be insufficient to detect meaningful effects given the complex field setting and low bracelet sales rates (approximately 2% of visitors), suggesting the null results could reflect inadequate sensitivity rather than true absence of effects. Post-hoc power analyses confirmed this concern: our study achieved only 8.2% power to detect the observed effect size (d = .10). A priori analyses demonstrated that detecting this small effect would require approximately 1,645 days per condition—nearly 28 times our sample size. Our study was adequately powered only for medium effects (d ≥.5), requiring 67 days per condition, while small but potentially meaningful effects (d = .3) would require approximately 184 days per condition.

The field context included numerous uncontrolled variables—visitor demographics, weather conditions, and seasonal patterns—that were not statistically modeled, potentially affecting both internal validity and generalizability. Additionally, systematic measurement of trainer script adherence, delivery consistency, or visitor attention levels was not conducted, complicating attribution of effects solely to script modifications. These identified limitations provide a roadmap for future studies to implement more robust experimental controls and measurement approaches when investigating behavioral change interventions in naturalistic settings.

The use of bracelet sales as dependent variable represents an indirect behavioral proxy that may be influenced by factors unrelated to conservation motivation, including price sensitivity and purchasing convenience, without capturing actual conservation attitudes or intentions. A further limitation - and perhaps the most significant methodological constraint - is that bracelet sales data could include purchases made by visitors who did not attend the shows, potentially diluting any effect of the script interventions on actual show attendees. Without tracking which bracelet purchasers actually attended the shows, we cannot definitively attribute sales patterns to script modifications. This indirect measurement of pro-conservation behavior makes it challenging to isolate the impact of the script changes on specifically targeted show audiences versus general zoo visitors.

Given that Zoomarine Algarve receives hundreds of thousands of visitors annually, and a substantial proportion may not attend the bird shows (particularly on high-attendance days when shows may reach capacity), the causal link between script content and bracelet purchases remains uncertain. Future studies should track bracelet sales linked directly to show participation, through point-of-sale inquiries or venue-specific sales locations, or supplement behavioral data with surveys to better attribute purchases to experimental interventions. This limitation requires particular caution in interpreting our findings and necessitates the tentative language used throughout our results discussion.

The study’s context specificity—conducted at a single Portuguese zoo with specific shows and species—limits broader applicability to other zoo settings or visitor populations.

Future research should incorporate mixed-effects modeling of contextual variables, systematic trainer performance assessment, and triangulated outcome measures including visitor surveys to address these limitations. These constraints do not invalidate the findings but emphasize the need for cautious interpretation and context-specific replication before implementing similar interventions elsewhere.

4.7 Implications for policy and practice in zoos

Zoo managers seeking to optimize conservation fundraising appeals should adopt systematic evaluation approaches before implementing messaging changes. Our findings suggest that well-intentioned modifications can produce unintended effects, though definitive causal attribution is limited by our study design. This underscores the importance of controlled testing with rigorous tracking mechanisms rather than intuitive program adjustments.

Managers should consider piloting alternative framings through small-scale experiments. For social proof approaches, descriptive norms must be carefully calibrated to visitor context. Rather than stating aggregate amounts that may inadvertently signal low individual participation rates, managers might test messages emphasizing current visitor engagement: “Many families visiting today have chosen to support conservation” or “Visitors like you have helped fund three rescue operations this month.” Such framings maintain social proof benefits while avoiding non-participation norms.

For authenticity concerns, managers should ensure adequate trainer preparation time for any script modifications. Natural delivery appears critical for message credibility. Additionally, timing considerations suggest testing conservation appeals at different show segments rather than only at conventional endpoints, potentially reducing cognitive fatigue effects.

Future program evaluation should incorporate randomized assignment of conditions across days or weeks, with clear dependent variables that directly link to conservation outcomes. Managers should also consider venue-specific factors: immediate bracelet availability at show locations, staff training consistency, and seasonal visitor composition all influence intervention effectiveness.

Most importantly, zoo professionals should embrace null results as valuable program information. Failed interventions provide crucial data about visitor psychology and can prevent costly organization-wide implementation of ineffective strategies. Establishing internal evaluation protocols that document both successful and unsuccessful conservation communication attempts will contribute to evidence-based practice development across the zoo community.

This evidence-driven approach transforms conservation messaging from intuitive practice into systematic behavioral intervention, ultimately serving both institutional fundraising goals and broader wildlife conservation objectives.

5 Conclusion

Field experiences are essential for a more comprehensive understanding of the human decision-making process, considering the complex interaction of factors that influence choices in everyday life and, more relevantly in this context, in the decision-making process to support conservation efforts. While not all experiences prove effective, testing and reporting unsuccessful strategies contribute to improving basic knowledge in behavior change. Finally, for scientific knowledge to advance, it is crucial to share the findings of those studies where the results were null or negative. This allows other researchers to learn from experiments, gain further insights and avoid unnecessary and costly repetition. Although the study’s limitations - particularly the inability to definitively associate bracelet sales with show attendance – prevent us from drawing causal conclusions about the specific techniques used, our findings highlight the critical importance of a rigorous experimental design in the study of conservation-focused behavioral change. The value of this work does not reside in definite conclusions on specific persuasion techniques but rather illustrates the methodological challenges inherent to field experiments and the need for transparent reporting, both on methodological limitations and on null results.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Zoomarine's Science Committee (ZM_2022ID01). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

JN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. KL: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. IC: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Magic Rainbow and Flying Colors teams for their willingness and professionalism to implement the methodological design in the field. The authors would also like to express gratitude to Diogo Veríssimo for his help in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript to enhance the manuscript’s linguistic precision and stylistic coherence.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2025.1701972/full#supplementary-material

References

Alba A. C., Leighty K. A., Pittman Courte V. L., Grand A. P., and Bettinger T. L. (2017). A turtle cognition research demonstration enhances visitor engagement and keeper-animal relationships. Zoo Biol. 36, 243–249. doi: 10.1002/zoo.21373

Baumeister R. F. and Finkel E. J. (2010). Advanced social psychology: The state of the science (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Bindra S., Sharma D., Parameswar N., Dhir S., and Paul J. (2022). Bandwagon effect revisited: A systematic review to develop future research agenda. J. Business Res. 143, 305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.085

Burton J. D. (2020). How scripted is this going to be?“ Raters’ Views of authenticity in speaking-performance tests. Lang. Assess. Q. 17, 244–261. doi: 10.1080/15434303.2020.1754829

EAZA (2022). EAZA Standards for the Accommodation and Care of Animals in Zoos and Aquaria (Amsterdam: European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, Amsterdam).

Goldstein N. J., Cialdini R. B., and Griskevicius V. (2008). A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J. Consumer Res. 35, 472–482. doi: 10.1086/586910

Gusset M. and Dick G. (2011). The global reach of zoos and aquariums in visitor numbers and conservation expenditures. Zoo Biol. 30, 566–569. doi: 10.1002/zoo.20369

Hart P. S. (2011). One or many? The influence of episodic and thematic climate change frames on policy preferences and individual behavior change. Sci. Communication 33, 28–51. doi: 10.1177/1075547010366400

Hibbert S. (2016). “Charity communications: Shaping donor perceptions and giving,” in The Routledge Companion to Philanthropy. Eds. Jung D., Phillips S., and Harrow J. (Routledge, London), 102–116.

Jenni K. and Loewenstein G. (1997). Explaining the identifiable victim effect. J. Risk Uncertainty 14, 235–257. doi: 10.1023/A:1007740225484

Johnson E. J., Payne J. W., and Bettman J. R. (1988). Information displays and preference reversals. Organizational Behav. Hum. Decision Processes 42, 1–21. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(88)90017-9

Kimble G. (2014). Children learning about biodiversity at an environment centre, a museum and at live animal shows. Stud. Educ. Eval. 41, 48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.09.005

Lavie N., Hirst A., De Fockert J. W., and Viding E. (2004). Load theory of selective attention and cognitive control. J. Exp. Psychology: Gen. 133, 339–354. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.133.3.339

Lee S. and Feeley T. H. (2016). The identifiable victim effect: A meta-analytic review. Soc. Influence 11, 199–215. doi: 10.1080/15534510.2016.1216891

Leibenstein H. (1950). Bandwagon, snob, and Veblen effects in the theory of consumers’ demand. Q. J. Econ 64, 183–207. doi: 10.2307/1882692

Mackay M., Jennings S., van Putten E. I., Sibly H., and Yamazaki S. (2018). When push comes to shove in recreational fishing compliance, think ‘nudge’. Mar. Policy 95, 256–266. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.05.026

Mann-Lang J. B., Ballantyne R., and Packer J. (2016). Does more education mean less fun? A comparison of two animal presentations. Int. Zoo Yearbook 50, 155–164. doi: 10.1111/izy.12114

Markowitz E. M., Slovic P., Västfjäll D., and Hodges S. D. (2013). Compassion fade and the challenge of environmental conservation. Judgment Decision Making 8, 397–406. doi: 10.1017/S193029750000526X

Martin N. and Morich K. (2011). Unconscious mental processes in consumer choice: Toward a new model of consumer behavior. J. Brand Manage. 18, 483–505. doi: 10.1057/bm.2011.10

Miller L. J., Zeigler-Hill V., Mellen J., Koeppel J., Greer T., and Kuczaj S. (2013). Dolphin shows and interaction programs: benefits for conservation education? Zoo Biol. 32, 45–53. doi: 10.1002/zoo.21016

Miranda R., Escribano N., Casas M., Pino-del-Carpio A., and Villarroya A. (2023). The role of zoos and aquariums in a changing world. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 11, 287–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-050622-104306

Mitchell S. L. and Clark M. (2021). Telling a different story: How nonprofit organizations reveal strategic purpose through storytelling. Psychol. Marketing 38, 142–158. doi: 10.1002/mar.21429

Munafò M. and Neill J. (2016). Null is beautiful: on the importance of publishing null results. J. Psychopharmacol. 30, 585–585. doi: 10.1177/02698811166388

Newberry M. G. III, Fuhrman N. E., and Morgan A. C. (2017). Naming “animal ambassadors“ in an educational presentation: Effects on learner knowledge retention. Appl. Environ. Educ. Communication 16, 223–233. doi: 10.1080/1533015X.2017.1333051

Packer J. and Ballantyne R. (2010). The role of zoos and aquariums in education for a sustainable future. New Dir. adult continuing Educ. 2010, 25–34. doi: 10.1002/ace.378

Page M. J., Sterne J. A., Higgins J. P., and Egger M. (2022). “Investigating and Dealing with Publication Bias and Other Reporting Biases,” in Systematic Reviews in Health Research: Meta-Analysis in Context. Eds. Egger M., Higgins J. P. T., and Smith G. D. (Wiley), 74–90.

Perrault E. K., Silk K. J., Sheff S., Ahn J., Hoffman A., and Totzkay D. (2015). Testing the identifiable victim effect with both animal and human victims in anti-littering messages. Communication Res. Rep. 32, 294–303. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2015.1089857

Price A., Boeving E. R., Shender M. A., and Ross S. R. (2015). Understanding the effectiveness of demonstration programs. J. Museum Educ. 40, 46–54. doi: 10.1080/10598650.2015.11510832

Ripple K. J., Sandhaus E. A., Brown M. E., and Grow S. (2021). Increasing AZA-accredited zoo and aquarium engagement in conservation. Front. Environ. Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.594333

Saffran L., Hu S., Hinnant A., Scherer L. D., and Nagel S. C. (2020). Constructing and influencing perceived authenticity in science communication: Experimenting with narrative. PloS One 15, e0226711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226711

Small D. A. (2015). “On the psychology of the identifiable victim effect,” in Identified versus statistical lives: an interdisciplinary perspective. Eds. Cohen I. G., Daniels N., and Eyal N. M. (Oxford University Press, Oxford), 13–23.

Small D. A. and Loewenstein G. (2003). Helping a victim or helping the victim: Altruism and identifiability. J. Risk Uncertainty 26, 5–16. doi: 10.1023/A:1022299422219

Smith R. W., Faro D., and Burson K. A. (2013). More for the many: The influence of entitativity on charitable giving. J. Consumer Res. 39, 961–976. doi: 10.1086/666470

Spears L. A. (2002). Persuasive techniques used in fundraising messages. J. Tech. Writing Communication 32, 245–265. doi: 10.2190/BE4V-QJNC-Q97H-DFXN

Spooner S. L., Jensen E. A., Tracey L., and Marshall A. R. (2021). Evaluating the effectiveness of live animal shows at delivering information to zoo audiences. Int. J. Sci. Education Part B 11, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/21548455.2020.1851424

Thomas-Walters L., McCallum J., Montgomery R., Petros C., Wan A. K., and Veríssimo D. (2023). Systematic review of conservation interventions to promote voluntary behavior change. Conserv. Biol. 37, e14000. doi: 10.1111/cobi.14000

Thomas-Walters L. and Raihani N. J. (2017). Supporting conservation: The roles of flagship species and identifiable victims. Conserv. Lett. 10, 581–587. doi: 10.1111/conl.12319

Keywords: identifiable victim, donation, conservation, zoo, persuasion techniques, bird shows

Citation: Neves J, Leong K and Correia I (2025) Beyond success stories: learning from behavioral interventions in zoo conservation fundraising. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6:1701972. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1701972

Received: 09 September 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025; Revised: 20 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Jeffrey Skibins, East Carolina University, United StatesReviewed by:

Kevin Kerr, University of Guelph, CanadaAlegria Olmedo, Fauna and Flora International, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Neves, Leong and Correia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joao Neves, anBjbmV2ZXNAZ21haWwuY29t

Joao Neves

Joao Neves Kristina Leong1

Kristina Leong1