- 1Department of Chemical, Physical, Mathematical and Natural Sciences, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy

- 2e.INS- Ecosystem of Innovation for Next Generation Sardinia, Spoke 09 Environment, Sardinia, Italy

- 3Department of Architecture, Design and Urban Planning, University of Sassari, Alghero, Italy

- 4National Biodiversity Future Center (NBFC), Palermo, Italy

Invasive alien species represent an increasing threat to biodiversity conservation at both the species and ecosystem levels. Damages caused by invasive alien plants are more impactful when acting in areas of particular concentration of endemic species, such as biodiversity hotspots. In the Mediterranean Basin, one of the global biodiversity hotspots, the effects of alien plant invasions are well studied, especially in coastal environments. However, a lack of investigation on the effect of the coastal salt gradient on the interactions between native and alien plants seems to exist. Here, we explored the impact of the eradication of the invasive clonal plants referred to as Carpobrotus sp. pl. on vascular plant richness and diversity along a salinity coastal gradient in a dune system located in northern Sardinia (Italy). In the study area, we established three belts from the sea, each 50 m deep: at each belt, we eradicated Carpobrotus sp. pl. in 10 1 × 1 m plots; another 10 plots were controls with high coverage of Carpobrotus sp. pl., and another 10 plots were controls without Carpobrotus sp. pl. Since it was already demonstrated that soil salinity in dunes is negligible, we also measured sea aerosol salinity at each belt. We found that aerosol salinity was 0.0322 mg/cm2/day, corresponding to 1,174 kg/ha/year. In this paper, we show that belt was always a highly significant factor in all analyses we carried out, meaning that there were significant differences among the three belts for all the response variables investigated (bare soil and vegetation cover, number of species m−2, and Shannon index). This was especially true in those plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were eradicated. Our results show that the distance from the sea should always be considered when planning eradication actions, because the salinity gradient strongly influences the vegetation’s initial successional dynamics after the elimination of the alien plants.

1 Introduction

Invasive species are one of the five main drivers causing recent global anthropogenic biodiversity loss (Cowie et al., 2022; Jaureguiberry et al., 2022) and are the second most common threat associated with species that have gone completely extinct since AD 1500 (Bellard et al., 2016).

The alarming introduction, establishment, and spread process of invasive alien plants (IAPs) created (and is still producing) negative impacts on the ecosystems by threatening native communities’ richness and diversity, distribution, persistence, and ecosystem stability, both locally and globally (e.g., Blumenthal, 2005; Acosta et al., 2007; Pyšek et al., 2010; Ricciardi et al., 2013; Novoa et al., 2014; Bellard et al., 2016; Campoy et al., 2016; Lazzaro et al., 2019, 2020a, b; Giulio et al., 2020). In addition, they could cause serious economic, social, health, and political problems (Shine, 2007; Pimentel, 2011; Simberloff et al., 2013; Haubrock et al., 2021; Zenni et al., 2021).

These threats are mainly due to the biological and/or ecological characteristics of IAPs (fast-growing, clonal traits, high seed production, phytochemical release, life-history traits, ability to colonize open spaces quickly) and also to the invasibility of the invaded habitats (Blumenthal, 2005; Callaway et al., 2008; Roiloa et al., 2015; Campoy et al., 2016; Roiloa, 2019; Campoy et al., 2022; Assaeed et al., 2020; Portela et al., 2021; Rodríguez et al., 2021; Portela et al., 2022a, b).

Non-native plant invasion is imputable to globalization and human pressures that act both directly and indirectly (Thuiller et al., 2006; Rodríguez-Labajos et al., 2009; Pyšek et al., 2010; van Kleunen et al., 2015; Giulio et al., 2020; Portela et al., 2022a, b), causing native biodiversity and habitat loss mostly in coastal areas and island ecosystems (van der Maarel and van der Maarel-Versluys, 1996; Zedda et al., 2010; Bacchetta et al., 2012; Acosta et al., 2007; Fried et al., 2014; Lazzaro et al., 2020a, b; Giulio et al., 2020, 2021; Cerrato et al., 2023). The impact of IAPs is particularly strong on Mediterranean islands (Thompson, 2020), and the amount of alien taxa on total flora in large Mediterranean islands varies from 6.7% for Crete to 17.4% for Sardinia (Médail, 2017). The effects caused by IAPs are more impactful when acting in areas of particular concentration of endemic species, such as biodiversity hotspots and threatened habitats.

In the last decades, several programs were developed to monitor the establishment and spread of the alien plant propagules (Acosta et al., 2007; Bacchetta et al., 2012; Fois et al., 2020; Lazzaro et al., 2020a, b; Portela et al., 2021, 2022, b) and to promote ad hoc international and national legislation, studies, actions, policies, and strategies (Acosta et al., 2008; Farris et al., 2013; Maccioni et al., 2019, 2020; Giulio et al., 2020; Lazzaro et al., 2020a, b; Pagad et al., 2022), for example through EU LIFE programs (e.g., Braschi et al., 2015; Acunto et al., 2017; Celesti-Grapow et al., 2017; Buisson et al., 2020; Cossu et al., 2022).

One of the most threatening IAP groups in Mediterranean coastal environments is the genus Carpobrotus N.E.Br. (Aizoaceae), mat-forming trailing succulent perennial herbs native to South Africa, highly threatening Mediterranean coastal areas, including cliffs and sand dune systems, due to their tolerance to stress factors such as salinity, drought, and excess light (Campoy et al., 2018). Indeed, among the plant traits favoring invasions in harsh environments, stress tolerance to salinity is invoked as one of the key factors, not only for Carpobrotus species (El Kenany et al., 2025).

Carpobrotus taxa are capable of downregulating the activity of fast vacuolar channels when exposed to a saline environment (Zeng et al., 2018). This ability greatly enhances germination and growth responses of Carpobrotus species to salinity (Weber and D’Antonio, 1999), because salt stimulates shoot elongation at low or moderate salt concentrations (Varone et al., 2017). Furthermore, tolerance to salinity by these species is also exhibited in short- and long-distance dispersal of seeds and propagules transported by seawater (Souza-Alonso et al., 2020).

Control and eradication measures for Carpobrotus species in Mediterranean coastal environments include physical removal with long-term monitoring and restoration of soil conditions and elimination of the seed bank (Campoy et al., 2018; Souza-Alonso et al., 2018; Munné-Bosch, 2024). This point seems to be crucial because Carpobrotus species cause significant changes to pH, enzymatic activities, nutrients, salinity, and moisture content, altering the germination process of native and invasive plants (Novoa and González, 2014; Novoa et al., 2014), increasing fungal and microbial biomass, and altering soil microbial structure (Badalamenti et al., 2016). Experimental studies demonstrated that living Carpobrotus removal is a better eradication method than removal of living Carpobrotus and litter, because leaving its litter in place reduces soil erosion and leads to higher native plant species recolonization (Chenot et al., 2018).

Considering the pivotal role that biotic and abiotic gradients play on the spatial arrangement of plant communities on Mediterranean coastal dunes (Ruocco et al., 2014; Cusseddu et al., 2016; Angiolini et al., 2018; Maccioni et al., 2021) and the poor attention that these gradients received in Carpobrotus removal programs, this research explored the effects of the eradication of the invasive clonal plants referred to as Carpobrotus sp. pl. on vascular plant richness and diversity along a salinity coastal gradient in a dune system located in northern Sardinia (Italy). Specifically, we aimed at 1) characterizing the coastal gradient by measuring the sea aerosol salinity deposition (since it was already shown that soil salinity in coastal dunes is negligible, see Maccioni et al., 2021) and 2) measuring vascular plant species richness and diversity in three different treatments (invaded by Carpobrotus sp. pl., invaded but eradicated, not invaded plots) along a coastal gradient.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Carpobrotus sp. pl.

The taxonomic identity of clonal invader IAPs in Europe belonging to the genus Carpobrotus was debated (Bagella et al., 2025). European floras generally recognize two species: Carpobrotus acinaciformis (L.) L.Bolus and Carpobrotus edulis (L.) N.E.Br., but their tendency to hybridize often complicates identification and taxonomic assignment (Suehs et al., 2001, 2004; Novoa et al., 2013; Bagella et al., 2025). This is why here we refer to this complex of species and hybrids as Carpobrotus sp. pl. Both species and their hybrids occupy similar coastal dune habitats and display comparable adaptation and impacts (Verlaque et al., 2011; Campoy et al., 2016, 2018; Vieites-Blanco et al., 2020; Lazzaro et al., 2020a, b; Bagella et al., 2025). These plants are sometimes harvested from the wild for their medicinal uses and edible fruit, while they are also cultivated both as ornamental plants and for their ability to stabilize sandy soils.

In Europe, the clonal invaders referred to as Carpobrotus sp. pl. were introduced in 1680 for ornamental purposes and sand dune stabilization. These neophyte species were first reported in Sardinia (Italy) in 1899 (Camarda et al., 2016; Campoy et al., 2016, 2018). Their invasiveness is due to biological and ecological characteristics, such as large seed production, fast clonal growth, high plasticity of clonal growth organs, survival to dryness and high salt conditions, rooting capacity of crawling stems, and high tolerance to trampling (Camarda et al., 2016; Roiloa, 2019; Campoy et al., 2016, 2018, 2022).

2.2 Study area

Sardinia, the second largest island in the Mediterranean Basin, is a meso hotspot of plant biodiversity (Cañadas et al., 2014) in the context of the Tyrrhenian Islands macro hotspot (Médail and Quézel, 1999; Myers et al., 2000): with 1.897 km of coastline, the 8% of its surface is considered of high value for plant diversity conservation as well (Bacchetta et al., 2012; Marignani et al., 2014; Farris et al., 2018; Fois et al., 2020), hosting ca. 15% of endemic plants on a flora of 2,300–2,500 taxa (Médail, 2017; Fois et al., 2022).

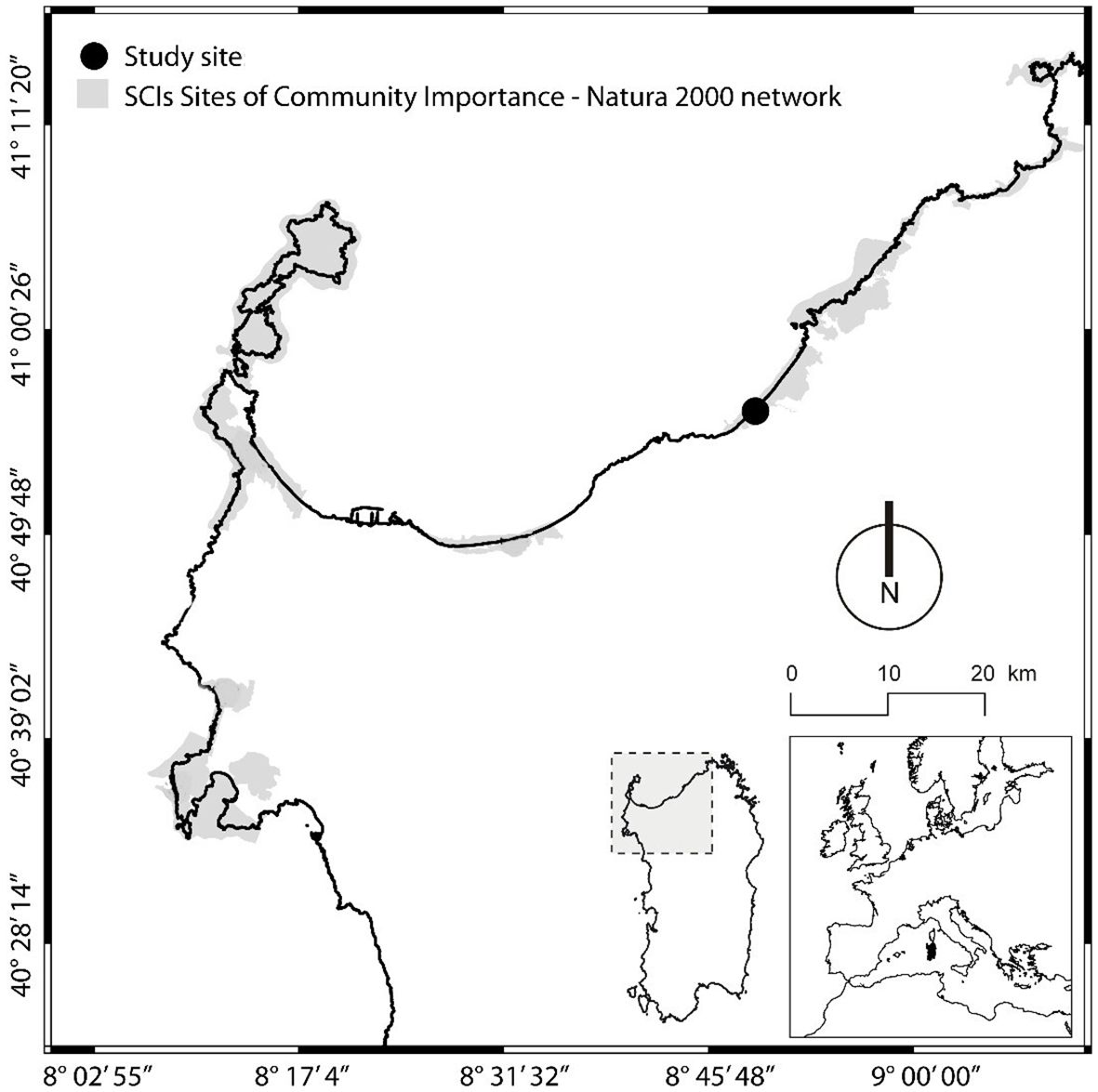

The study site was located in a sandy coastal area in Northern Sardinia, named Li Junchi in the municipality of Badesi (40°56′27.87″N; 8°49′6.94″E; Figure 1), and falls within the Natura 2000 site (code ITB010004): it is characterized by a typical Mediterranean macrobioclimate, with prolonged summer drought and mild winter, Mediterranean Pluviseasonal Oceanic bioclimate, and Upper Thermo-Mediterranean, Upper Dry, Weak Semi-Hyper Oceanic Isobioclimate (Canu et al., 2015; Bazzato et al., 2021). Soil salinity in the study area is very low and has been measured over the course of 1 year, ranging between 0.01 and 0.06 g/L (Maccioni et al., 2021).

Figure 1. Location of the study area and sampling site named Li Junchi in the northern coast of Sardinia (Italy).

Li Junchi, composed of granitic sand and with an average elevation of 5 m a.s.l., hosts the vegetation of the psammophile, thermo-Mediterranean Sardinian geosigmetum of the coastal dune systems, referred to as the vegetation classes Cakiletea, Ammophiletea, Helichryso-Crucianelletea, Tuberarietea guttatae, and Quercetea ilicis (Bacchetta et al., 2009; Farris et al., 2017). The coastal psammophilous vegetation is highly specialized because it is strongly influenced by abiotic gradients (e.g., marine aerosol, as its effect decreases from the sea to the back-dune habitat) (Cusseddu et al., 2016; Giulio et al., 2020; Maccioni et al., 2021). Previous studies demonstrated experimentally that these dune plant communities are organized hierarchically, structured by sand-binding foundation species on the fore dune, sand burial in the middle dune, and increasingly successful seedling recruitment, growth, and competitive dominance in the back dune (Cusseddu et al., 2016).

2.3 Aerosol salinity

Since we previously found soil salinity values to be very low at Sardinian dunes, including Li Junchi (Maccioni et al., 2021), here, we sampled aerosol salinity. The wind data for the preliminary characterization of the site were obtained from the Regional Environment Agency of Sardinia - Meteoclimatic Department.

In this study, considering the spatial distribution patterns of habitats and plant communities on the coastal dune (Cusseddu et al., 2016), the area was divided into three belts: starting from the shoreline, belt 1 (0–50 m), belt 2 (51–100 m), and belt 3 (101–150 m). To measure aerosol salinity, we built salt spray collectors to intercept the sea salt aerosol. They consist of a 50-cm metal tube, a 90°-angle elbow PVC pipe connector, and a plastic bottleneck, where a Whatman® 42.98% cellulose filter was inserted, having a diameter of 47 mm and 2.5 μm minimum particle retention. Three salt spray-detecting devices were positioned at each belt (defined as above for the whole sampling design), with their cellulose filters facing the shoreline, at a height of approximately 15 cm from the dune surface. Aerosol salinity was sampled in 2023 at five times (time 1 = March; time 2 = April; time 3 = May; time 4 = July; time 5 = October) at each belt and after 14 days of filter positioning at each time. Three measurements were taken at each combination of time × belt. Overall, we took 45 samples to determine sea salt aerosol in the study area.

The aerosol salinity captured by the salt spray collectors was analyzed at the Laboratory of Aquatic Ecology of the University of Sassari. The filters were analyzed by a bench conductivity meter of the Thermo Electron Corporation brand, model Orion 150+. The samples were placed in Falcon-type tubes, diluted in 40 mL of distilled water, and shaken for 10 min to facilitate the filter disintegration and salt passage in solution. Salinity was calculated using an indirect method starting from the solution conductivity expressed in μS cm−1 at 25°C, according to Rice et al. (2017), so that the salinity values in PSU corresponded approximately to g salt/1 L solution.

Then, a proportion was applied for calculating the salt quantity (mg) deposited on the filter surface (17.3406 cm2). Finally, averaging for the total number of days of exposure of the cellulose filter on the dune, the amount of deposited salt on the filter was referred to the daily unit and to the area unit (1 cm2), to obtain a measure of mg/cm2/day.

We do not expect any tidal influence on soil and aerosol salinity, because in the Mediterranean Basin, the average tidal height is approximately 20–30 cm only (Fenu et al., 2013).

2.4 Effects of eradication on species richness and community diversity

The Carpobrotus sp. pl. eradication experiment started in November 2022 and ended in June 2023. The monitoring was carried out at three different times: December 2022 (time 1), March 2023 (time 2), and June 2023 (time 3). Also, for this experiment, the area was divided into three belts previously described. To evaluate the eradication effects of Carpobrotus sp. pl. on the biodiversity of psammophilous plant communities, at each belt, we established 30 fixed plots, each with an area of 1 m2. Overall, there were 90 fixed plots. According to the treatments, the 30 fixed plots per belt were divided into 10 plots without Carpobrotus sp. pl. (absence of Carpobrotus: Ab-C), 10 plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (eradication of Carpobrotus: Er-C) using mechanical removal, and 10 plots with a high density of Carpobrotus sp. pl. (presence of Carpobrotus: Pr-C). Therefore, each data series of 10 plots × treatment × belt × time has been identified by a univocal alpha-numerical code, containing in the first position an indication of the time (T1, T2, or T3); in the second, the belt (B1, B2, or B3); and in the last position, one of the abovementioned treatment codes (Ab-C, Er-C, or Pr-C).

Each fixed plot, in turn, has been divided into 100 small squares (each of them with an area of 10 cm2). For each time and plot, vascular plant richness and diversity and the total vegetation and bare soil cover were measured, by giving to each species a value ranging from 1 to 100 (each small square of 10 cm2 with the presence of a given species had a value of 1). Later, with the cover values, we calculated the Shannon–Weaver index H′ (Shannon and Weaver, 1949).

2.5 Statistical analyses

Three-way ANOVAs were used to assess significant differences in the Shannon and Weaver index, richness, total vegetation, and bare soil cover, between different treatments (three treatments—factor 1), distances from the sea (three belts—factor 2), and time (three times—factor 3). All factors were considered orthogonal and fixed. The ANOVAs were followed by the consequent Fisher’s least significant difference post hoc test (p < 0.05). All the statistical analyses were carried out using Minitab® Statistical Software Version 22.4.0.

3 Results

3.1 Aerosol salinity

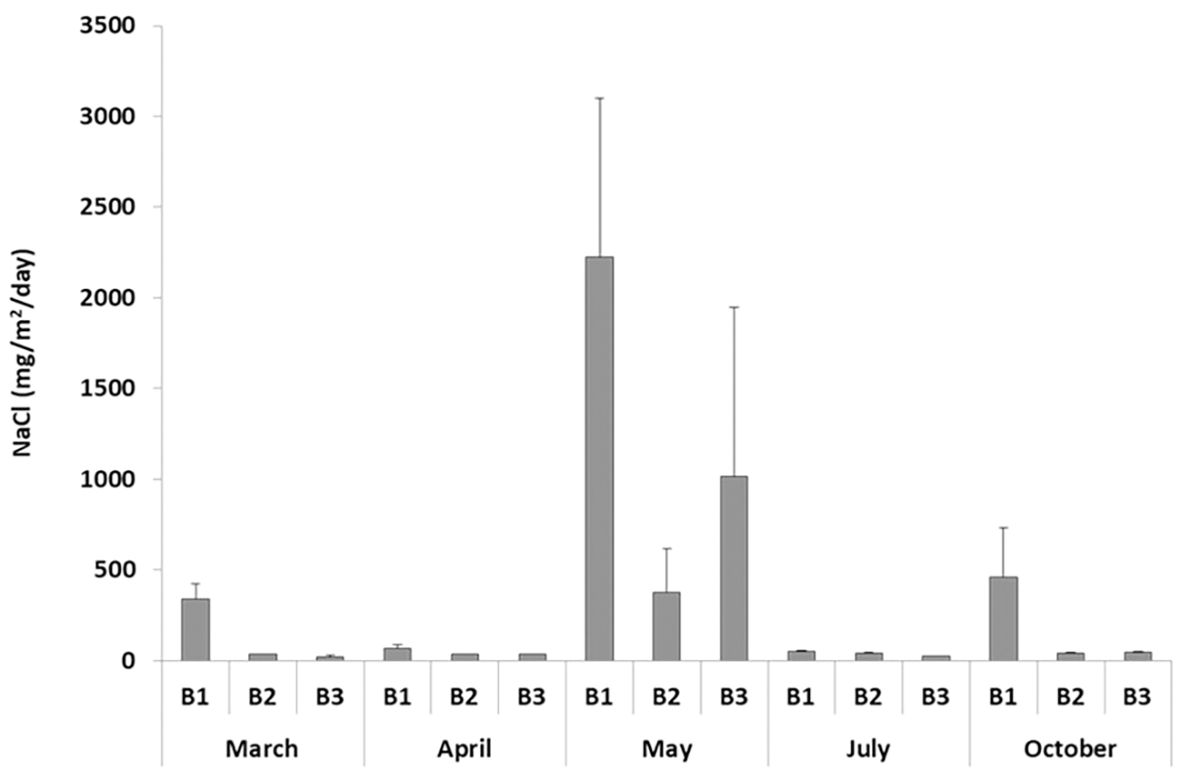

The dune system investigated is characterized by substantial uniformity with respect to wind exposure. During 2023, in the study area, the average wind intensity was 4.7 m/s, the prevailing wind direction was W-N-W, with an annual percentage of the wind blowing in this direction of 17.4%. In the study area, we found an average aerosol salinity deposition of 0.0322 mg/cm2/day. The salinity varied greatly among monthly measurements, ranging from 0.0041 mg/cm2/day in time 4 (July) to 0.1205 mg/cm2/day in time 3 (May). Interestingly, belt 3 showed a daily salt deposition of 228.53 mg/m2/day, higher than the 106.54 mg/m2/day measured at belt 2 (Figure 2). These data mean an average annual salt deposition of 1.174 kg/ha/year in the first 150 m of the studied dune system, with relevant differences among the three belts (2298.7 kg/ha/year at belt 1; 388.87 kg/ha/year at belt 2; 834.13 kg/ha/year at belt 3).

Figure 2. Aerosol salinity (mg/m2/day + SE) at Li Junchi (Sardinia, Italy), measured at three belts (belt 1 = 0–50 m from the sea, belt 2 = 51–100 m, and belt 3 = 101–150 m), at five times in 2023 (time 1 = March, time 2 = April, time 3 = May, time 4 = July, and time 5 = October). Three measurements were taken at each combination of time × belt.

3.2 Total vegetation and bare soil cover

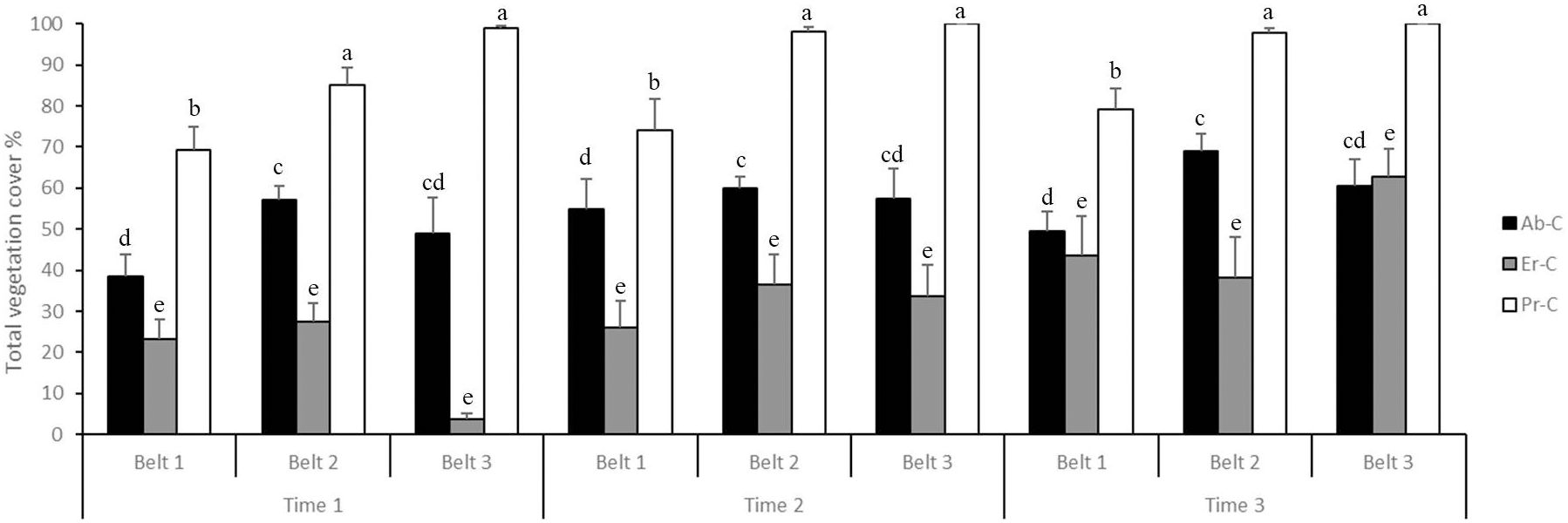

Overall, the total vegetation cover percentage was 59.05% and ranged from a minimum value of 3.8% (T1B3Er-C) to a maximum value of 100% (T2B3Pr-C and T3B3Pr-C).

The percentage of total vegetation cover (Figure 3) was higher at time 3 (66.76%) and time 2 (60.13%) and lower at time 1 (50.27%); it was higher in belt 2 (63.29%) and in belt 3 (62.89%) and lower in belt 1 (50.98%). Lastly, it was found to be higher in Pr-C (89.19%), medium in Ab-C (55.11%), and lower in Er-C (32.86%).

Figure 3. Total vegetation cover (% + SE) at the coastal dune ecosystem Li Junchi (Sardinia, Italy), measured at three belts (belt 1 = 0–50 m from the sea, belt 2 = 5 1–100 m, and belt 3 = 101–150 m), at three times (time 1 = December 2022, time 2 = March 2023, and time 3 = June 2023) and 30 fixed 1 m2 plots per belt, that were divided into 10 plots without Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Ab-C), 10 plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (Er-C), and 10 plots with a high density of Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Pr-C). Means that do not share a letter are significantly different.

In particular, in the plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (Er-C), the total vegetation cover (%) always increased from time 1 to time 2 and time 3: in belt 1 from 23.30% to 26.20% and 43.70%, respectively; in belt 2 from 27.40%, to 36.60% and 38.30%, respectively; and in belt 3 from 3.80%, to 33.70% and 62.70%, respectively (Figure 3).

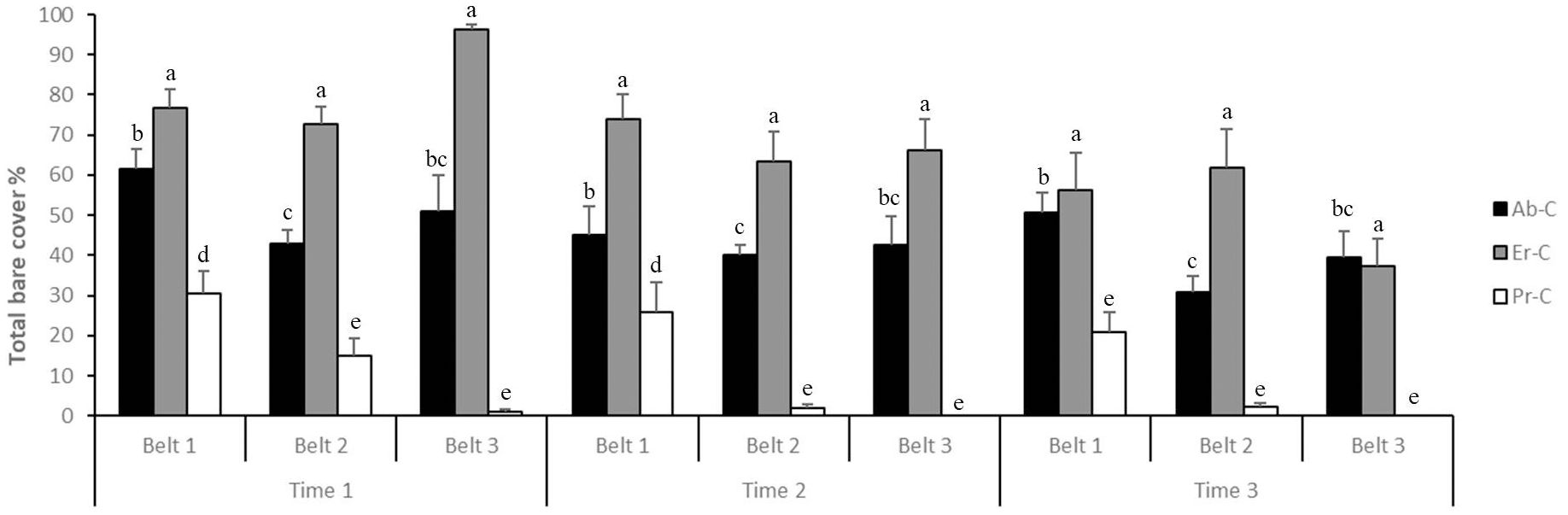

Overall, the bare soil cover percentage was on average 40.95% and ranged from a minimum value of 0.00% (T2B3Pr-C and T3B3Pr-C) to a maximum value of 96.20% (T1B3Er-C).

Specifically (Figure 4), the bare soil cover decreased from time 1 to time 2 and time 3 (49.73%, 39.87%, and 33.24%, respectively); it also decreased from belt 1 (49.02%) to belt 2 (36.71%) and belt 3 (37.11%). Lastly, it reached its maximum average in Er-C plots (67.14%), averaged in Ab-C plots (44.89%), and reached its minimum average in Pr-C (10.81%).

Figure 4. Bare soil cover (% + SE) at the coastal dune ecosystem Li Junchi (Sardinia, Italy), measured at three belts (belt 1 = 0–50 m from the sea, belt 2 = 51–100 m, and belt 3 = 101–150 m), at three times (time 1 = December 2022, time 2 = March 2023, and time 3 = June 2023) and 30 fixed 1 m2 plots per belt, that were divided into 10 plots without Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Ab-C), 10 plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (Er-C), and 10 plots with a high density of Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Pr-C). Means that do not share a letter are significantly different.

In all plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (Er-C), bare soil cover always decreased from time 1 to time 2 and time 3: in belt 1, from 76.70% to 73.80% and 56.30%, respectively; in belt 2, from 72.60% to 63.40% and 61.70%, respectively; in belt 3, from 92.20% to 66.30% and 37.30%, respectively (Figure 4).

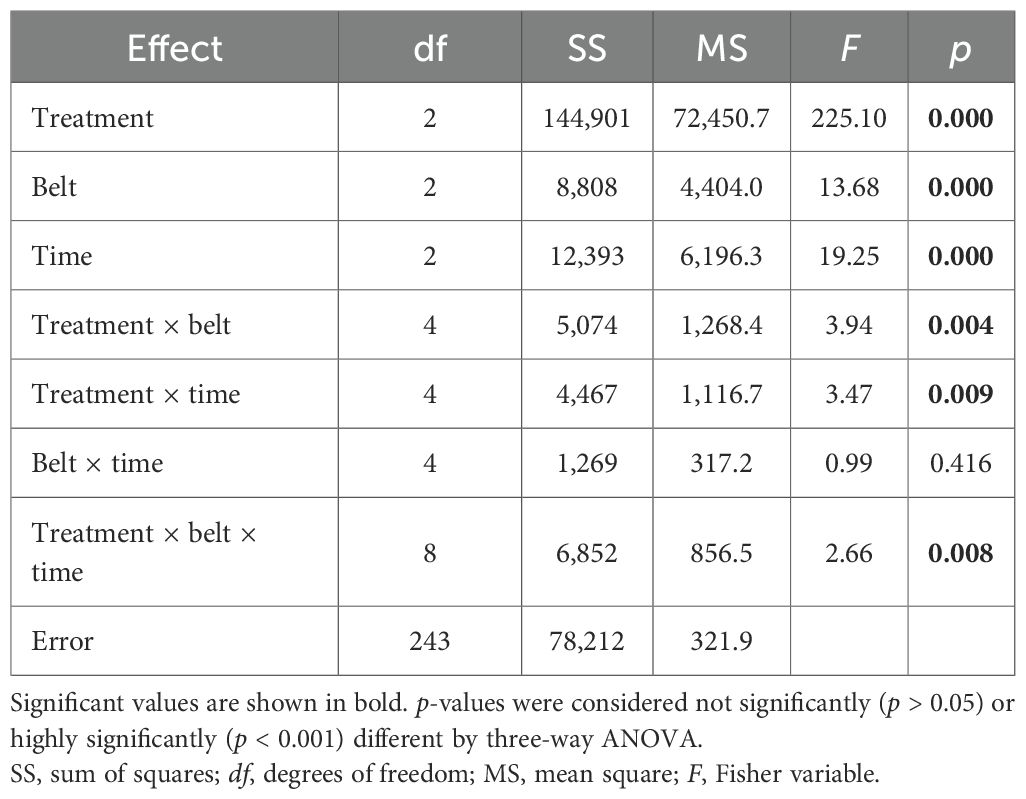

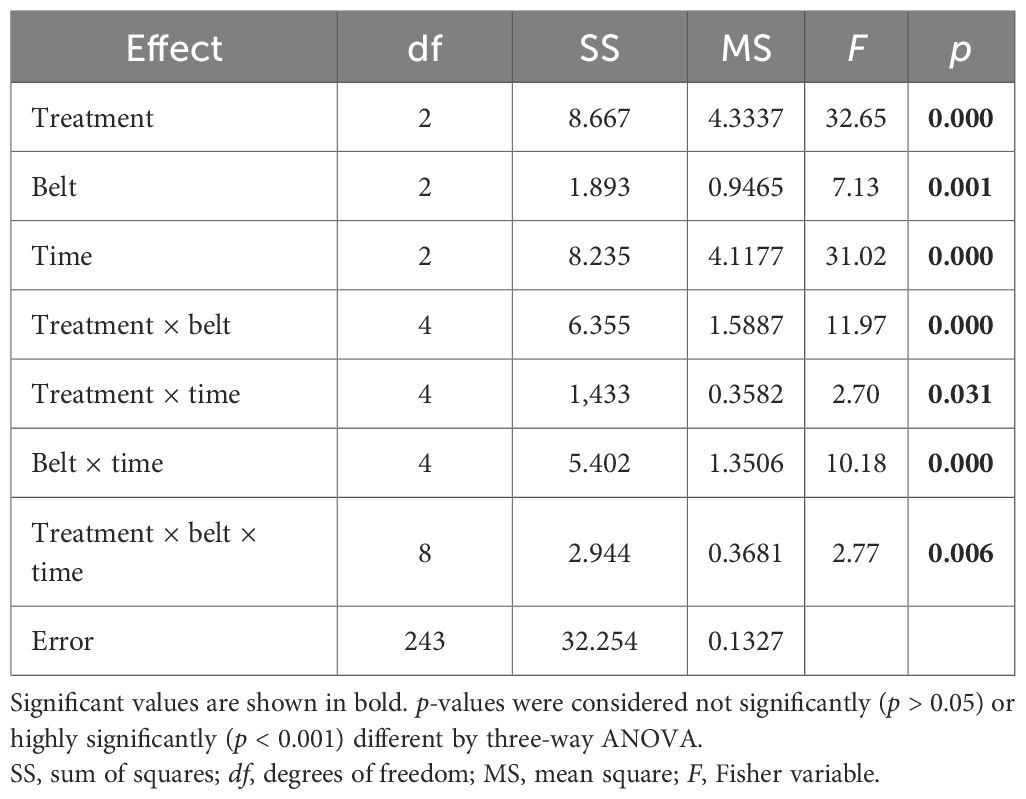

Three-way ANOVA for the total vegetation cover and bare soil cover (Table 1) showed that all factors and their interactions have a strong impact, except for belt × time (not significantly; p > 0.05). Fisher’s least significant difference post hoc test for the treatment factor showed significant differences between bare soil cover and vegetation cover in Er-C treated plots, in the plots with a high density of Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Pr-C), and in the plots without Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Ab-C)—in each belt at any time.

Table 1. Three-way ANOVA, testing the differences in the bare soil cover (%) and the total vegetation cover (%) at the coastal dune ecosystem Li Junchi (Sardinia, Italy), between three belts (belt 1 = 0–50 m from the sea, belt 2 = 51–100 m, and belt 3 = 101–150 m), at three times (time 1 = December 2022, time 2 = March 2023, and time 3 = June 2023) and three treatments—30 fixed 1 m2 plots per belt, that were divided into 10 plots without Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Ab-C), 10 plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (Er-C), and 10 plots with a high density of Carpobrotus sp. pl., and their interactions.

3.3 Effects of eradication on species richness and community diversity

In the 270 field surveys carried out, we surveyed a list of 57 vascular plants (Supplementary Materials 1). Of these plants, 25 were annuals, and the rest were perennials; the majority of the taxa were of Mediterranean or Mediterranean-Atlantic chorotype, but five were endemic to Sardinia, Sardinia, and Corsica or the Tyrrhenian area [Anchusa crispa Viv. subsp. maritima (Vals.) Selvi & Bigazzi; Astragalus thermensis Vals.; Galium verrucosum Huds. subsp. halophilum (Ponzo) Lambinon; Helichrysum italicum subsp. tyrrhenicum (Bacch., Brullo et Giusso) Herrando, J.M. Blanco, L. Sáez & Galbany and Silene nummica Vals.]; two can be considered of phytogeographical relevance [Armeria pungens (Link) Hoffmanns. & Link and Ephedra distachya L.]; and three were alien taxa [Acacia saligna (Labill.) H.L.Wendl., Carpobrotus sp. pl., and Pinus halepensis Mill.].

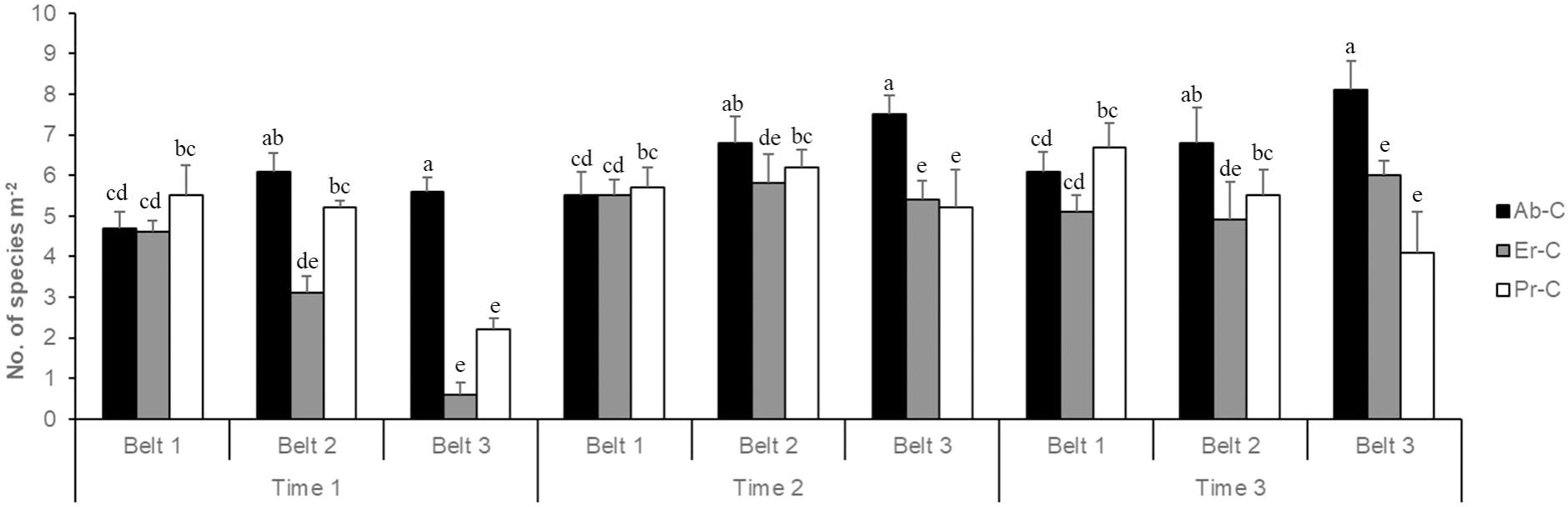

On average, we found 5.35 species m−2, with a minimum value of 0.6 species m−2 (T1B3Er-C) and a maximum value of 8.1 species m−2 (T3B3Ab-C).

Overall, the average number of species was lower at time 1 (4.18 species m−2) and higher at time 2 (5.96 species m−2) and time 3 (5.92 species m−2); it was lower in belt 3 (4.97 species m−2) and higher in belt 1 (5.49 species m−2) and belt 2 (5.60 species m−2) (Figure 5). Finally, the number of species was higher in Ab-C (6.36 species m−2), average in Pr-C (5.14 species m−2), and lower in Er-C (4.56 species m−2).

Figure 5. Number of vascular plant species (+SE) at the coastal dune ecosystem Li Junchi (Sardinia, Italy), measured at three belts (belt 1 = 0–50 m from the sea, belt 2 = 51–100 m, and belt 3 = 101–150 m), at three times (time 1 = December 2022, time 2 = March 2023, and time 3 = June 2023) and 30 fixed 1 m2 plots per belt, that were divided into 10 plots without Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Ab-C), 10 plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (Er-C), and 10 plots with a high density of Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Pr-C). Means that do not share a letter are significantly different.

In particular, in all plots where the Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (Er-C), the number of species increased through time: in belt 1, it was 4.60 species m–2 at time 1, 5.50 species m−2 at time 2, and 5.10 species m−2 at time 3; in belt 2, it increased from time 1 (3.10 species m−2) to time 2 (5.80 species m−2) and slightly decreased at time 3 (4.90 species m−2); lastly, in belt 3, it markedly increased from time 1 (0.60 species m−2) to time 2 (5.40 species m−2) and time 3 (6.00 species m−2) (Figure 5).

Three-way ANOVA for the number of species (Table 2) showed that all factors and their interactions have a strong effect, except for treatment × time and treatment × belt × time (not significant; p > 0.05). Fisher’s least significant difference post hoc test for the treatment factor revealed significant differences in the number of species between Er-C and the other two treatments in belt 2 at all three times; however, in belt 3 at all times, a significant difference was shown between Er-C and Ab-C. Finally, in belt 1, at any time, no significant differences in the number of species were recorded between Er-C and the other two treatments.

Table 2. Three-way ANOVA, testing the differences in the number of species at the coastal dune ecosystem Li Junchi (Sardinia, Italy), between three belts (belt 1 = 0–50 m from the sea, belt 2 = 51–100 m, and belt 3 = 101–150 m), at three times (time 1 = December 2022, time 2 = March 2023, and time 3 = June 2023) and three treatments—30 fixed 1 m2 plots per belt, that were divided into 10 plots without Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Ab-C), 10 plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (Er-C), and 10 plots with a high density of Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Pr-C), and their interactions.

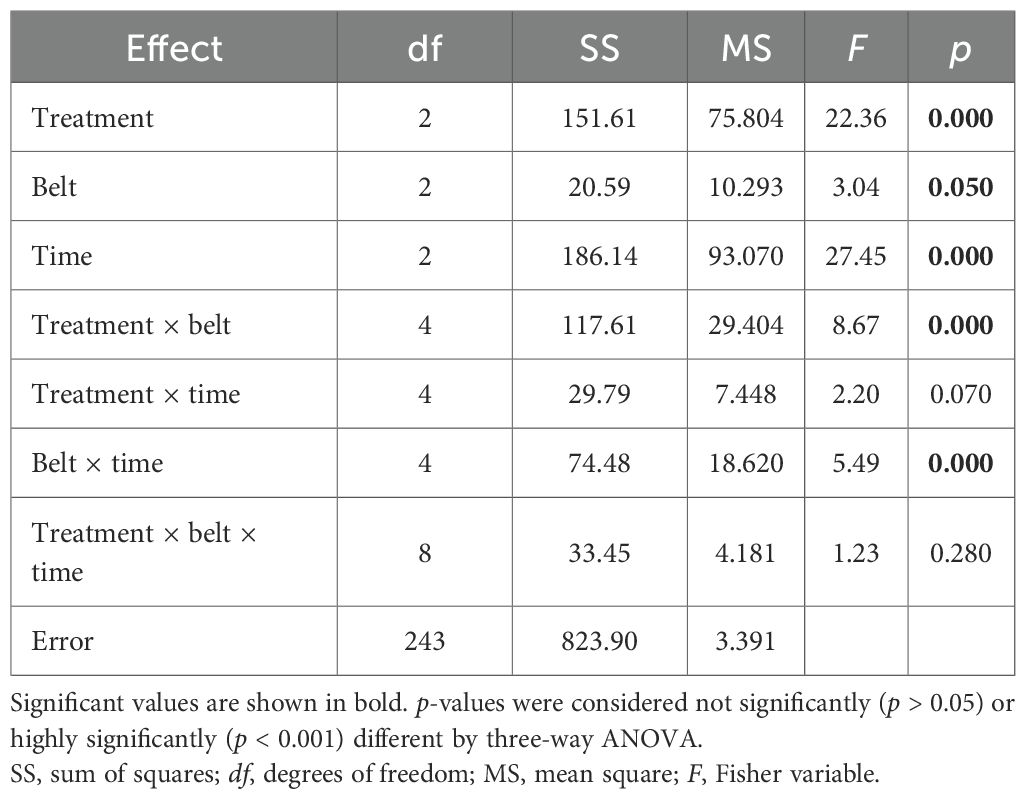

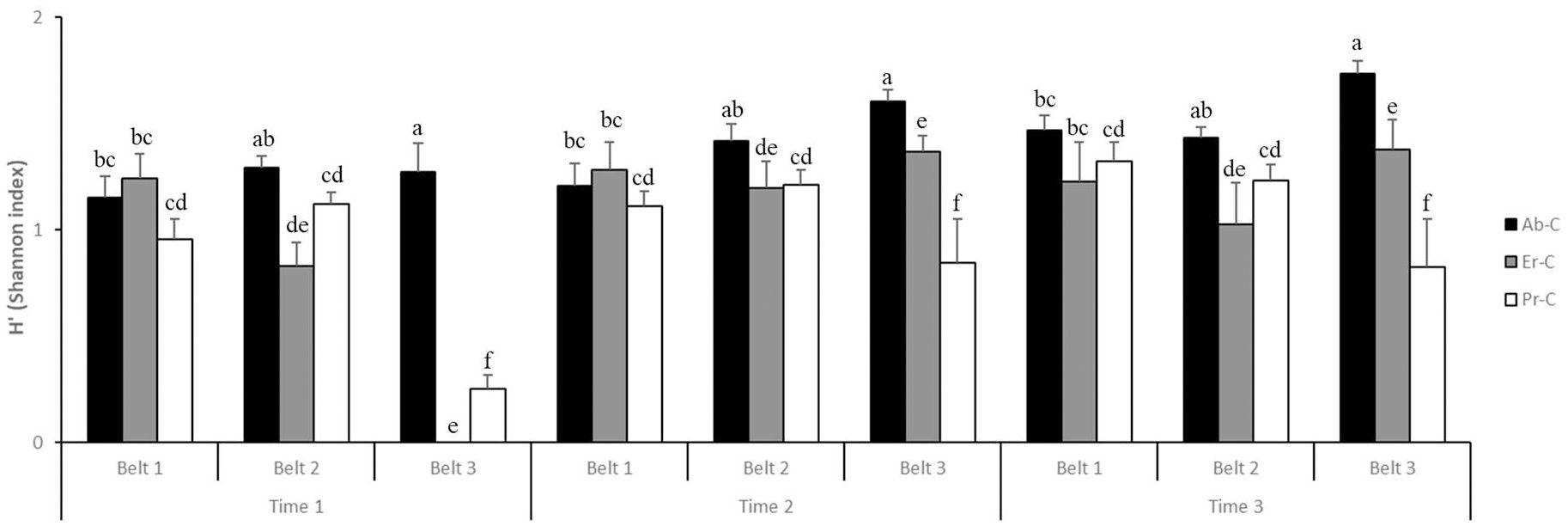

The Shannon and Weaver’s diversity index (H′) was on average 1.15 and varied from a minimum average value of 0.00 (T1B3Er-C) to a maximum average value of 1.73 (T3B3Ab-C).

H′ was higher at time 3 (1.29) and time 2 (1.25) and lower at time 1 (0.90); it was higher in belt 1 (1.22) and in belt 2 (1.20) but lower in belt 3 (1.03) (Figure 6). Lastly, it was found to be higher in Ab-C (1.40) and in Er-C (1.06); it was lower in Pr-C (0.99).

Figure 6. Shannon and Weaver’s diversity index (H′ + SE) at the coastal dune ecosystem Li Junchi (Sardinia, Italy), measured at three belts (belt 1 = 0–50 m from the sea, belt 2 = 51–100 m, and belt 3 = 101–150 m), at three times (time 1 = December 2022, time 2 = March 2023, and time 3 = June 2023) and 30 fixed 1 m2 plots per belt, that were divided into 10 plots without Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Ab-C), 10 plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (Er-C), and 10 plots with a high density of Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Pr-C). Means that do not share a letter are significantly different.

In particular, in all areas where the Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (Er-C), in belt 1, the H′ remained constant from time 1 to time 2 to time 3 (1.24, 1.28, and 1.23, respectively); in belt 2, it increased from time 1 (0.83) to time 2 (1.20) and decreased at time 3 (1.03) (Figure 6). Lastly, in belt 3, it increased from time 1 to time 2 and time 3 (0.00, 1.37, and 1.38, respectively).

Three-way ANOVA for Shannon and Weaver’s diversity index (H′; Table 3) showed that all factors and their interactions have a strong impact. Fisher’s least significant difference post hoc test for the treatment factor showed significant differences in H′ between Er-C and the other two treatments in belt 2 at all three times; however, in belt 3 at all times, a significant difference was shown between Er-C and Ab-C. Finally, in belt 1, at any time, no significant differences in H′ were recorded between Er-C and the other two treatments.

Table 3. Three-way ANOVA, testing the differences in the Shannon and Weaver’s diversity index (H′) at the coastal dune ecosystem Li Junchi (Sardinia, Italy), between three belts (belt 1 = 0–50 m from the sea, belt 2 = 51–100 m, and belt 3 = 101–150 m), at three times (time 1 = December 2022, time 2 = March 2023, and time 3 = June 2023) and three treatments—30 fixed 1 m2 plots per belt, that were divided into 10 plots without Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Ab-C), 10 plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. have been eradicated (Er-C), and 10 plots with a high density of Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Pr-C), and their interactions.

4 Discussion

Invasive alien plant management is an efficient tool that helps to prevent the extinction, loss, or degradation of native biodiversity and habitats (Ruffino et al., 2013; Buisson et al., 2020). Even if the eradication of IAPs in Mediterranean-type ecosystems brings considerable benefits to the invaded environments (Brunel et al., 2013; García-de-Lomas et al., 2014; Chenot et al., 2018; Buisson et al., 2020), it is often considered a challenge, because of their very efficient invasive strategy, due to a combination of propagule pressure and the establishment of long-term seed banks (Munné-Bosch, 2024). Therefore, removal, eradication, and control measures of IAPs should be planned and achieved in combination with the knowledge of plant community succession and ecology at a fine-resolution spatial and temporal scales. However, to our knowledge, it seems that in Mediterranean coastal habitats, whose fine-resolution functioning is already well known (Cusseddu et al., 2016), the effects of the coastal salt gradient on IAP eradication were never taken into account previously (Chenot et al., 2018; Buisson et al., 2020; Lazzaro et al., 2020a, b; Fos et al., 2021; Misuri et al., 2024).

In this paper, we first measured the amount of aerosol salty spray deposited per year, because it is a good descriptor of the sea-inland gradient (in contrast to the salt content in sandy soils, see Maccioni et al., 2021): it seems that very few attempts were made previously to measure aerosol salt deposition (Donnelly and Pammenter, 1983; Rozema et al., 1983; Griffiths, 2006). To our knowledge, this is the first time that salt deposition caused by marine aerosol was measured in situ at Mediterranean coastal environments. At the three belts of the study area, we measured an average daily salt deposition of 0.322 mg NaCl/cm2, with relevant differences among months, but always with higher values measured at the vegetation belt closer to the seashore. Other authors already quantified the wind action in central Mediterranean dunes (Carboni et al., 2011; Fenu et al., 2013), but to understand the ecology of psammophilous plants, it is important to measure salt deposition on their leaves (Griffiths, 2006), because it seems to play a major role in selecting the species able to live on dunes (Rozema et al., 1983), also in combination with the mechanical damage caused by wind (Donnelly and Pammenter, 1983) and the effect of burial (Gormally and Donovan, 2010). The values of salt deposition we detected correspond to an average of 1,174 kg NaCl/ha/year in the whole dune system (0–150 m from the seashore), which is comparable to the 1,460 kg NaCl/ha/year measured by Rozema et al. (1983) in the island of Schiermonnikoog (North Sea) at 53°29′21″N, 6°12′07.92″E. Interestingly, our approach consisting in separated measures for the three belts allowed us to highlight that the first belt of vegetation from the seashore (0–50 m) receives nearly the double of the average salt deposition (ca. 2,300 kg NaCl/ha/year), which corresponds to ca. 6 times the amount of NaCl received by the second belt (51–100 m from the seashore: ca. 390 kg NaCl/ha/year) and 2.75 times the amount of NaCl received by the third belt (101–150 m from the seashore: 834 kg NaCl/ha/year). These data are relevant to understand the differences in species assemblages and plant communities previously observed on Mediterranean dunes (Molina et al., 2003; Angiolini et al., 2013; Ruocco et al., 2014; Cusseddu et al., 2016; Angiolini et al., 2018; Maccioni et al., 2021) and the differences in species richness and diversity we measured in this eradication experiment.

Although it was already demonstrated that not only stress gradients influence above- and belowground plant traits and plant–plant interactions (Bricca et al., 2023; La Bella et al., 2024) but also the variation in local abiotic conditions can explain differences in invasibility within a local environment, and intermediate levels of natural disturbance and stress offer the best conditions for spread of alien species (Carboni et al., 2011). Surprisingly, the variations of vegetation cover and species richness and diversity after Carpobrotus sp. pl. removal in relation to the distance from the sea (and the salt gradient) in Mediterranean coastal dunes were never tested. In this paper, we show that belt was always a highly significant factor in all analyses we carried out, meaning that there were significant differences among the three belts for all the response variables investigated (bare soil and vegetation cover, number of species m−2, and Shannon index). This was especially true in those plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were eradicated.

As expected, the vegetation cover was higher in the mid and back dunes and lower in the fore dune; in contrast, the bare soil cover was higher in the fore dune and lower in the mid and back dunes. Carpobrotus sp. pl. had a negative effect on bare soil, with vegetation cover on average 90% in the invaded plots and 55% in those not invaded. However, more importantly, the short-term recovery of natural vegetation was faster at the back dune (from 3.8% at time 1 to 62.7% at time 3) than in the fore dune (from 23.3% at time 1 to 43.7% at time 3). It is noteworthy that at belt 1 and belt 3, at time 3, the percentage cover of the total vegetation in the plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were eradicated reached roughly the same values as the control plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were absent (Figure 3). Therefore, despite numerous previous papers claiming that long-term monitoring activity is essential to ensure an efficient and successful ecological restoration (Brunel et al., 2013; Chenot et al., 2018; Souza-Alonso et al., 2018; Buisson et al., 2020), here, we should underline how natural vegetation cover recovered to undisturbed levels after less than 1 year from Carpobrotus sp. pl. removal.

The same was not true for the number of species: in the plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were eradicated, the number of species significantly increased from time 1 to time 2 (the slight reduction at belts 1 and 2 from time 2 to time 3 was due to annual species drying up from spring to summer); however, at time 3, the number of species in the plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were eradicated was still lower than the control plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were absent (Figure 5). Through time, the differences in the number of species among plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were eradicated and those where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were absent were higher from the sea to inland. In fact, at belt 1, the open areas not occupied by Carpobrotus sp. pl. at time 1 averaged 30.6%, allowing native species to be present, whereas at the same time, the open areas not occupied by Carpobrotus sp. pl. in belt 3 averaged 1.1%, making it difficult for native plants to grow. As expected from previous research, the number of species per area increased from belt 1 to belt 3 (Figure 5).

Interestingly, not only the number but also the type of species showed some interesting variations. Even if the short time of the survey did not allow us to collect useful data on perennials re-colonizing the plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were eradicated, some annual species exhibited peculiar patterns: for example, Silene nummica was mainly present at times 2 and 3 in the plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were absent in belt 3; at the same time, Sonchus oleraceus L., a nitrophilous species, was mainly present in the plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were eradicated in belt 3. To note, Chenot et al. (2018) also detected that the composition of the vegetation 10 months after applying their experimental treatments was biased in favor of native pioneer species, some of which were the same present at our study area [Sonchus bulbosus (L.) N.Kilian & Greuter subsp. bulbosus, S. oleraceus, and Lotus cytisoides L.], and Lazzaro et al. (2023) found that improvements in native vegetation cover were driven by nitrophilous species in their experimental plots treated with mulching sheets.

Differences in the Shannon index among belts were striking, especially for those plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were eradicated. On average, H′ was significantly lower at belt 3 than at belts 1 and 2, because belt 3 was the one with higher Carpobrotus sp. pl. cover and lower bare soil cover. As expected, the overall H′ of the whole dune system increased from time 1 to time 2 and time 3. Most interestingly, the variation of H′ through time in the plots where the Carpobrotus sp. pl. were eradicated was significantly different among the belts. In fact, while at belt 1, the H′ remained constant from time 1 to time 3, at belt 2, it slightly increased from time 1 to time 3. Instead, at belt 3, the increase of H′ in the plots where Carpobrotus sp. pl. were eradicated was very great from time 1 to time 2 and time 3 (Figure 6).

Since Carpobrotus sp. pl. invasion acts throughout the process of replacement and exclusion of native species, rather than coexistence (Lazzaro et al., 2023), eradication and monitoring measures are urgently needed. Even if the amount of removal experiences in Mediterranean coastal habitats is great, we underline the need for a detailed monitoring of the effects of the eradication through the coastal gradient. Other authors previously found that the plant community recovering in Mediterranean coastal sites quickly reached a composition and structure similar to that of non-invaded coastal vegetation, although some slow-growing native species were underrepresented after years (Buisson et al., 2020). However, here, we show how the variation of the response variables through time greatly depends on the distance from the sea. This is especially true for vascular plant diversity (here expressed as the Shannon index H′), whereas the increase in species richness recovered more slowly than diversity, because during the first year after Carpobrotus sp. pl. removal, the species recovery was mainly driven by native annual pioneer species, especially the nitrophilous ones, because of the particular soil conditions of the plots invaded by Carpobrotus sp. pl (Badalamenti et al., 2016). However, even if our study duration is excellent for capturing the initial recovery and the response of pioneer/annual species, the limitation is that it is a bit short to assess the full recovery of the native perennial plant community: long-term monitoring is necessary to confirm if this positive initial trend leads to a stable, restored perennial community.

In conclusion, here we show that the first vegetation close to the sea (fore dune), characterized by high salt spray deposition, even when invaded by Carpobrotus sp. pl., maintains a relevant percentage of bare soil, allowing native species to persist also in invaded patches. Contrarily, in the middle and especially the back dunes, more suitable for Carpobrotus sp. pl., open spaces for the native species are scarce or absent, and the need for active eradication and restoration actions is crucial. Our findings are in accordance to Cusseddu et al. (2016), who demonstrated experimentally that Mediterranean sand dune plant communities are organized hierarchically, structured by sand binding foundation species on the fore dune, sand burial in the middle dune, and increasingly successful seedling recruitment, growth, and competitive dominance in the back dune, and confirm that environmental gradients shape fine-scale community composition and alien distribution patterns on coastal dunes (Griffiths, 2006; Gormally and Donovan, 2010; Carboni et al., 2011; La Bella et al., 2024) and therefore should not be overlooked when planning eradication and monitoring of IAPs in coastal Mediterranean environments. However, our conclusions refer to the data collected in a restricted geographical area of Sardinia without replications in other similar coastal ecosystems in the same region and, therefore, cannot be generalized without implementing further studies following other Carpobrotus sp. pl. eradication interventions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. SD: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work has been developed within the framework of the project e.INS- Ecosystem of Innovation for Next Generation Sardinia (cod. ECS 00000038) funded by the Italian Ministry for Research and Education (MUR) under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) - MISSION 4 COMPONENT 2, “From research to business” INVESTMENT 1.5, “Creation and strengthening of Ecosystems of innovation” and construction of “Territorial R&D Leaders”, CUP J83C21000320007 for AM and EF.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Luisa Canopoli, Marco Cossu, Valeria Cubeddu, Elisabetta Cucca, Valentina Murru, Stefania Pisanu, David Roazzi, Arianna Russu, and Debora Terrosu for their help in fieldwork. The authors are grateful to the reviewers who kindly reviewed the first version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2025.1730419/full#supplementary-material

References

Acosta A., Carranza M. L., Ciaschetti G., Conti F., Di Martino L., D’Orazio G., et al. (2007). Specie vegetali esotiche negli ambienti costieri sabbiosi di alcune regioni dell’Italia Centrale. Webbia. 62, 77–84. doi: 10.1080/00837792.2007.10670817

Acosta A., Carranza M. L., Di Martino L., Frattaroli A., Izzi C. F., and Stanisci A. (2008). “Patterns of native and alien plant species occurrence on coastal dunes in Central Italy,” in the plant invasions: human perception, ecological impacts and management. Eds. Tokarska-Guzik B., Brock J. H., Brundu G., Child L., Daehler C. C., and Pyšek P. (Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, NL), 235–248.

Acunto S., Bacchetta G., Bordigoni A., Cadoni N., Cinti M. F., Duràn Navarro M., et al. (2017). The LIFE+ project RES MARIS – recovering endangered habitats in the Capo Carbonara marine area, Sardinia (LIFE13 NAT/IT/000433): first results. Plant Sociol. 54, 85–95. doi: 10.7338/pls2017541S1/11

Angiolini C., Bonari G., and Landi M. (2018). Focal plant species and soil factors in Mediterranean coastal dunes: an undisclosed liaison? Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 211, 248−258. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2017.06.001

Angiolini C., Landi M., Pieroni G., Frignani F., Finoia M. G., and Gaggi C. (2013). Soil chemical features as key predictors of plant community occurrence in a Mediterranean coastal ecosystem. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 119, 91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2012.12.019

Assaeed A. M., Al-Rowaily S. L., El-Bana M. I., Hegazy A. K., Dar B. A., and Abd-ElGawad A. M. (2020). Functional traits plasticity of the invasive herb argemone ochroleuca sweet in different arid habitats. Plants. 9, 1268. doi: 10.3390/plants9101268

Bacchetta G., Bagella S., Biondi E., Farris E., Filigheddu R., and Mossa L. (2009). Vegetazione forestale e serie di vegetazione della Sardegna (con rappresentazione cartografica alla scala 1:350.000). Fitosociol. 46, 3–82.

Bacchetta G., Farris E., and Pontecorvo C. (2012). A new method to set conservation priorities in biodiversity hotspots. Plant Biosyst. 146, 638–648. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2011.642417

Badalamenti E., Gristina L., Laudicina V. A., Novara A., Pasta S., and La Mantia T. (2016). The impact of Carpobrotus cfr. acinaciformis (L.) L. Bolus on soil nutrients, microbial communities structure and native plant communities in Mediterranean ecosystems. Plant Soil. 409, 19–34. doi: 10.1007/s11104-016-2924-z

Bagella S., Bulai I. M., Malavasi M., and Orrù G. (2025). A theoretical model of plant species competition: The case of invasive Carpobrotus sp. pl. and native Mediterranean coastal species. Ecol. Inform. 87, 103070. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2025.103070

Bazzato E., Rosati L., Canu S., Fiori M., Farris E., and Marignani M. (2021). High spatial resolution bioclimatic variables to support ecological modelling in a Mediterranean biodiversity hotspot. Ecol. Model. 441, 109354. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2020.109354

Bellard C., Cassey P., and Blackburn T. M. (2016). Alien species as a driver of recent extinctions. Biol. Lett. 12, 20150623. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0623

Blumenthal D. (2005). Interrelated causes of plant invasion. Science. 310, 243–244. doi: 10.1126/science.1114851

Braschi J., Ponel P., Krebs É., Jourdan H., Passetti A., Barcelo A., et al. (2015). Éradications Simultanées Du Rat Noir (Rattus rattus) Et Des Griffes De Sorcière (Carpobrotus spp.) Sur L’île De Bagaud (Parc National De Portcros, Provence, France): Résultats préliminaires des conséquences sur les communautés d’arthropodes Revue d’Ecologie (Terre et Vie), Vol. 70. 91–98, Suppt 12 « Espèces invasives ».

Bricca A., Sperandii M. G., Acosta A. T., Montagnoli A., La Bella G., Terzaghi M., et al. (2023). Above-and belowground traits along a stress gradient: trade-off or not? Oikos. 2023, e010043. doi: 10.1111/oik.10043

Brunel S., Brundu G., and Fried G. (2013). Eradication and control of invasive alien plants in the Mediterranean Basin: towards better coordination to enhance existing initiatives. EPPO Bull. 43, 290–308. doi: 10.1111/epp.12041

Buisson E., Braschi J., Chenot-Lescure J., Hess M. C. M., Vidaller C., Pavon D., et al. (2020). Native plant community recovery after Carpobrotus (ice plant) removal on an island. results 10-year project. Appl. Veg. Sci. 24, e12524. doi: 10.1111/avsc.12524

Callaway R. M., Cipollini D., Barto K., Thelen G. C., Hallett S. G., Prati D., et al. (2008). Novel weapons: invasive plant suppresses fungal mutualists in America but not in its native Europe. Ecology. 89, 1043–1055. doi: 10.1890/07-0370.1

Camarda I., Cossu T. A., Carta L., Brunu A., and Brundu G. (2016). An updated inventory of the non-native flora of Sardinia (Italy). Plant Biosyst. 150, 1106–1118. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2015.1115438

Campoy J. G., Acosta A. T. R., Affre L., Barreiro R., Brundu G., Buisson E., et al. (2018). Monographs of invasive plants in Europe: Carpobrotus. Bot. Lett. 165, 440–475. doi: 10.1080/23818107.2018.1487884

Campoy J. G., Retuerto R., and Roiloa S. R. (2016). Resource-sharing strategies in ecotypes of the invasive clonal plant Carpobrotus edulis: specialization for abundance or scarcity of resources. J. Plant Ecol. 10, 681–691. doi: 10.1093/jpe/rtw073

Campoy J. G., Sobral M., Carro B., Lema M., Barreiro R., and Retuerto R. (2022). Epigenetic and phenotypic responses to experimental climate change of native and invasive Carpobrotus edulis. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.888391

Cañadas E. M., Fenu G., Peñas J., Lorite J., Mattana E., and Bacchetta G. (2014). Hotspots within hotspots: Endemic plant richness, environmental drivers, and implications for conservation. Biol. Conserv. 170, 282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.12.007

Canu S., Rosati L., Fiori M., Motroni A., Filigheddu R., and Farris E. (2015). Bioclimate map of sardinia (Italy). J. maps. 11, 1–8. doi: 10.1080/17445647.2014.988187

Carboni M., Santoro R., and Acosta A. T. R. (2011). Dealing with scarce data to understand how environmental gradients and propagule pressure shape fine-scale alien distribution patterns on coastal dunes. J. Veg. Sci. 22, 751–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2011.01303.x

Celesti-Grapow L., Abbate G., Baccetti N., Capizzi D., Carli E., Copiz R., et al. (2017). Control of invasive species for the conservation of biodiversity in Mediterranean islands. The LIFE PonDerat project in the Pontine Archipelago, Italy. Plant Biosyst. 151, 795–799. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2017.1353553

Cerrato M. D., Cortés-Fernández I., Ribas-Serra A., Mir-Rosselló P. M., Cardona C., and Gil L. (2023). Time pattern variation of alien plant introductions in an insular biodiversity hotspot: the Balearic Islands as a case study for the Mediterranean region. Biodivers. Conserv. 32, 2585–2605. doi: 10.1007/s10531-023-02620-z

Chenot J., Affre L., Gros R., Dubois L., Malecki S., Passetti A., et al. (2018). Eradication of invasive Carpobrotus sp.: effects on soil and vegetation. Restor. Ecol. 26, 106–113. doi: 10.1111/rec.12538

Cossu T. A., Lozano V., Spano G., and Brundu G. (2022). Plant invasion risk in the marine protected area of Tavolara (Italy). Plant Biosyst. 156, 1358–1364. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2022.2048279

Cowie R. H., Bouchet P., and Fontaine B. (2022). The sixth mass extinction: fact, fiction or speculation? Biol. Rev. 97, 640–663. doi: 10.1111/brv.12816

Cusseddu V., Ceccarelli G., and Bertness M. (2016). Hierarchical organization of a Sardinian sand dune plant community. PeerJ. 4, e2199. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2199

Donnelly F. A. and Pammenter N. W. (1983). Vegetation zonation on a Natal coastal sand-dune system in relation to salt spray and soil salinity. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2, 46–51. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4618(16)30144-9

El Kenany E. T., El-Keblawy A., and Shaltout S. K. (2025). Effects of soil salinity on nodulation and growth of non-native (Neltuma juliflora and Prosopis pallida) and native (Prosopis cineraria) seedlings in the arid deserts of the United Arab Emirates. Plant Ecol. 226, 957–968. doi: 10.1007/s11258-025-01543-9

Farris E., Canopoli L., Cucca E., Landi S., Maccioni A., and Filigheddu R. (2017). Foxes provide a direct dispersal service to Phoenician junipers in Mediterranean coastal environments: ecological and evolutionary implications. Plant Ecol. Evol. 150, 117–128. doi: 10.5091/plecevo.2017.1277

Farris E., Carta M., Circosta S., Falchi S., Papuga G., and de Lange P. (2018). The indigenous vascular flora of the forest domain of Anela (Sardinia, Italy). Phytokeys. 113, 97–143. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.113.28681

Farris E., Pisanu S., Ceccherelli G., and Filigheddu R. (2013). Human trampling effects on Mediterranean coastal dune plants. Plant Biosyst. 147, 1043–1051. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2013.861540

Fenu G., Carboni M., Acosta A. T. R., and Bacchetta G. (2013). Environmental factors influencing coastal vegetation pattern: New Insights from the Mediterranean Basin. Folia Geobot. 48, 493–508. doi: 10.1007/s12224-012-9141-1

Fois M., Farris E., Calvia G., Campus G., Fenu G., Porceddu M., et al. (2022). The endemic vascular flora of sardinia: A dynamic checklist with an overview of biogeography and conservation status. Plants. 11, 601. doi: 10.3390/plants11050601

Fois M., Podda L., Médail F., and Bacchetta G. (2020). Endemic and alien vascular plant diversity in the small Mediterranean islands of Sardinia: Drivers and implications for their conservation. Biol. Conserv. 244, 108519. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108519

Fos M., Sanz B., and Sanchis E. (2021). Carpobrotus management in a Mediterranean sand dune ecosystem: minimum effective glyphosate dose and an evaluation of tarping. J. Ecol. Eng. 22, 57–66. doi: 10.12911/22998993/138871

Fried G., Laitung B., Pierre C., Chagué N., and Panetta F. D. (2014). Impact of invasive plants in Mediterranean habitats: disentangling the effects of characteristics of invaders and recipient communities. Biol. Invasions 16, 1639–1658. doi: 10.1007/s10530-013-0597-6

García-de-Lomas J., Dana E. D., Gimeno D., García-Morilla J., and Ceballos G. (2014). Control de uña de león (Carpobrotus spp.; Aizoaceae) en la Isla de Tarifa. Rev. Soc Gad. Hist. Nat. 8, 31–41.

Giulio S., Acosta A. T. R., Carboni M., Campos J. A., Chytrý M., Loidi J., et al. (2020). Alien flora across European coastal dunes. Appl. Veg. Sci. 00, 1–11. doi: 10.1111/avsc.12490

Giulio S., Pinna L. C., Carboni M., Marzialetti F., and Acosta A. T. R. (2021). Invasion success on European coastal dunes. Plant Sociol. 58, 29–39. doi: 10.3897/pls2021581/02

Gormally C. L. and Donovan L. A. (2010). Responses of Uniola paniculata L. (Poaceae), an essential dune-building grass, to complex changing environmental gradients on the coastal dunes. Estuaries Coast. 33, 1237–1246. doi: 10.1007/s12237-010-9269-2

Griffiths M. E. (2006). Salt spray and edaphic factors maintain dwarf stature and community composition in coastal sandplain heathlands. Plant Ecol. 186, 69–86. doi: 10.1007/s11258-006-9113-8

Haubrock P. J., Cuthbert R. N., Tricarico E., Diagne C., Courchamp F., and Gozlan R. E. (2021). ““The recorded economic costs of alien invasive species in Italy”,” in The economic costs of biological invasions around the world, vol. 67 . Eds. Zenni R. D., McDermott S., García-Berthou E., and Essl F. (Sofia, Bulgaria: NeoBiota), 247–266. doi: 10.3897/neobiota.67.57747

Jaureguiberry P., Titeux N., Wiemers M., Bowler D. E., Coscieme L., Golden A. S., et al. (2022). The direct drivers of recent global anthropogenic biodiversity loss. Sci. Adv. 8, 45. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abm9982

La Bella G., Acosta A. T., Jucker T., Bricca A., Ciccarelli D., Stanisci A., et al. (2024). Below-ground traits, rare species and environmental stress regulate the biodiversity–ecosystem function relationship. Funct. Ecol. 38, 2378–2394. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.14649

Lazzaro L., Bolpagni R., Barni E., Brundu G., Blasi C., Siniscalco C., et al. (2019). Towards alien plant prioritization in Italy: methodological issues and first results. Plant Biosyst. 153, 740–746. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2019.1640310

Lazzaro L., Bolpagni R., Buffa G., Gentili R., Lonati M., Stinca A., et al. (2020a). Impact of invasive alien plants on native plant communities and Natura 2000 habitats: State of the art, gap analysis and perspectives in Italy. J. Environ. Manage. 274, 111140. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111140

Lazzaro L., Mugnai M., Ferretti G., Giannini F., Giunti M., and Benesperi R. (2023). (Not) sweeping invasive alien plants under the carpet: results from the use of mulching sheets for the control of invasive Carpobrotus spp. Biol. Invasions. 25, 2583–2597. doi: 10.1007/s10530-023-03059-7

Lazzaro L., Tondini E., Lombardi L., and Giunti M. (2020b). The eradication of Carpobrotus spp. in the sand-dune ecosystem at Sterpaia (Italy, Tuscany): indications from a successful experience. Biol. 75, 199–208. doi: 10.2478/s11756-019-00391-z

Maccioni A., Canopoli L., Cubeddu V., Cucca E., Dessena S., Morittu S., et al. (2021). Gradients of salinity and plant community richness and diversity in two different Mediterranean coastal ecosystems in NW Sardinia. Biodivers. Data J. 9, e71247. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.9.e71247

Maccioni A., Santo A., Falconieri D., Piras A., Farris E., Maxia A., et al. (2020). Phytotoxic effects of Salvia rosmarinus essential oil on Acacia saligna seedling growth. Flora. 269, 151639. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2020.151639

Maccioni A., Santo A., Falconieri D., Piras A., Manconi M., Maxia A., et al. (2019). Inhibitory effect of rosemary essential oil, loaded in liposomes, on seed germination of Acacia saligna, an invasive species in Mediterranean ecosystems. Botany. 97, 283–291. doi: 10.1139/cjb-2018-0212

Marignani M., Bacchetta G., Bagella S., Caria M. C., Delogu F., Farris E., et al. (2014). Is time on our side? Strengthening the link between field efforts and conservation needs. Biodivers Conserv. 23, 421–431. doi: 10.1007/s10531-013-0610-5

Médail F. (2017). The specific vulnerability of plant biodiversity and vegetation on Mediterranean islands in the face of global change. Reg. Environ. Change. 17, 1775–1790. doi: 10.1007/s10113-017-1123-7

Médail F. and Quézel P. (1999). Biodiversity Hotspots in the Mediterranean Basin: setting global conservation priorities. Conserv. Biol. 13, 1510–1513. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.98467.x

Misuri A., Siccardi E., Mugnai M., Benesperi R., Giannini F., Giunti M., et al. (2024). Evidence of short-term response of rocky cliffs vegetation after removal of invasive alien Carpobrotus spp. NeoBiota. 94, 127–143. doi: 10.3897/neobiota.94.120644

Molina J. A., Casermeiro M. A., and Moreno P. S. (2003). Vegetation composition and soil salinity in a Spanish Mediterranean coastal ecosystem. Phytocoenologia. 33, 475–494. doi: 10.1127/0340-269X/2003/0033-0475

Munné-Bosch S. (2024). Achieving the impossible: Prevention and eradication of invasive plants in Mediterranean-type ecosystems. Trends Plant Sci. 29, 437–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2023.11.007

Myers N., Mittermeier R. A., Mittermeier C. G., da Fonseca G. A. B., and Kents J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature. 403, 853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501

Novoa A. and González L. (2014). Impacts of Carpobrotus edulis (L.) NE Br. on the germination, establishment and survival of native plants: a clue for assessing its competitive strength. PloS One 9, e107557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107557

Novoa A., González L., Moravcová L., and Pyšek P. (2013). Constraints to native plant species establishment in coastal dune communities invaded by Carpobrotus edulis: Implications for restoration. Biol. Cons. 164, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.04.008

Novoa A., Rodríguez R., Richardson D., and González L. (2014). Soil quality: a key factor in understanding plant invasion? The case of Carpobrotus edulis (L.) N.E.Br. Biol. Invasions 16, 429–443. doi: 10.1007/s10530-013-0531-y

Pagad S., Bisset S., Genovesi P., Groom Q., Hirsch T., Jetz W., et al. (2022). Country compendium of the global register of introduced and invasive species. Sci. Data. 9, 391. doi: 10.1038/s41597-022-01514-z

Pimentel D. (2011). Biological invasions. economic and environmental costs of alien plant, animal, and microbe species (Florida, Boca Raton: CRC Press).

Portela R., Barreiro R., Alpert P., Xu C. Y., Webber B. L., and Roiloa S. R. (2022a). Comparative invasion ecology of Carpobrotus from four continents: responses to nutrients and competition. J. Plant Ecol. 16, rtac034. doi: 10.1093/jpe/rtac034

Portela R., Barreiro R., and Roiloa S. R. (2021). Effects of resource sharing directionality on physiologically integrated clones of the invasive Carpobrotus edulis. J. Plant Ecol. 14, 884–895. doi: 10.1093/jpe/rtab040

Portela R., Barreiro R., and Roiloa S. R. (2022b). Effects of sand burial in integrated clonal systems of the invasive Carpobrotus edulis. Bot. Lett. 169, 205–212. doi: 10.1080/23818107.2021.2003238

Pyšek P., Jarošik V., Hulme P. E., Kühn I., Wild J., and Winter M. (2010). Disentangling the role of environmental and human pressures on biological invasions across Europe. PNAS. 107, 12157–12162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002314107

Ricciardi A., Hoopes M. F., Marchetti M. P., and Lockwood J. L. (2013). Progress toward understanding the ecological impacts of non-native species. Ecol. Monogr. 83, 263–282. doi: 10.1890/13-0183.1

Rice E. W., Baird R. B., and Eaton A. D. (2017). Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 23rd (Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, Water Environment Federation).

Rodríguez J., Lorenzo P., and González L. (2021). Phenotypic plasticity of invasive Carpobrotus edulis modulates tolerance against herbivores. Biol. Invasions. 23, 1859–1875. doi: 10.1007/s10530-021-02475-x

Rodríguez-Labajos B., Binimelis R., and Monterroso I. (2009). Multi-level driving forces of biological invasions. Ecol. Econ. 69, 63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.08.022

Roiloa S. R. (2019). Clonal traits and plant invasiveness: The case of Carpobrotus N.E.Br. (Aizoaceae). PPEES. 40, 125479. doi: 10.1016/j.ppees.2019.125479

Roiloa S. R., Campoy J. G., and Retuerto R. (2015). Understanding the role of clonal integration in biological invasions. Ecosistemas. 24, 76–83. doi: 10.7818/ECOS.2015.24-1.12

Rozema J., Bijwaard P., Prast G., and Bruekman R. (1983). Ecophysiological adaptations of coastal halophytes from foredunes and salt marshes. Vegetatio 62, 499–521. doi: 10.1007/BF00044777

Ruffino L., Krebs E., Passetti A., Aboucaya A., Affre L., Fourcy D., et al. (2013). Eradications as scientific experiments: progress in simultaneous eradications of two major invasive taxa from a Mediterranean island. Pest Manage. Sci. 71, 189–198. doi: 10.1002/ps.3786

Ruocco M., Bertoni D., Sarti G., and Ciccarelli D. (2014). Mediterranean coastal dune systems: which abiotic factors have the most influence on plant communities? Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci. 149, 213−222. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2014.08.019

Shannon C. E. and Weaver W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press).

Shine C. (2007). Invasive species in an international context: IPPC, CBD, European Strategy on Invasive Alien Species and other legal instruments. EPPO Bullet. 37, 103–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2338.2007.01087.x

Simberloff D., Martin J.-L., Genovesi P., Maris V., Wardle D. A., Aronson J., et al. (2013). Impacts of biological invasions: what’s what and the way forward. Trends Ecol. Evol. 28, 58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.07.013

Souza-Alonso P., Guisande-Collazo A., Lechuga-Lago Y., and González L. (2018). The necessity of surveillance: medium-term viability of Carpobrotus edulis propagules after plant fragmentation. Plant Biosyst. 153, 736–739. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2018.1539043

Souza-Alonso P., Lechuga-Lago Y., Guisande-Collazo A., Rodríguez D. P., Porto G. R., and Rodríguez L. G. (2020). Drifting away. Seawater survival and stochastic transport of the invasive Carpobrotus edulis. Sci. Total Environ. 712, 135518. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135518

Suehs C. M., Affre L., and Médail F. (2004). Invasion dynamics of two alien Carpobrotus (Aizoaceae) taxa on a Mediterranean island: I. Genetic diversity and introgression. Heredity 92, 31–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800374

Suehs C. M., Médail F., and Affre L. (2001). “Ecological and genetic features of the invasion by the alien Carpobrotus plants in Mediterranean island habitats,” in in the Plant invasions: species ecology and ecosystem management. Eds. Brundu G. J., Camarda L., Child L., and Wade M. (Backhuys Publishers, Leiden), 145–158.

Thompson J. D. (2020). Plant evolution in the Mediterranean: insights for conservation (New York: Oxford University Press).

Thuiller W., Richardson D. M., Rouget M., Proches S., and Wilson J. R. U. (2006). Interactions between environment, species traits, and human uses describe patterns of plant invasions. Ecology. 87, 1755–1769. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1755:IBESTA]2.0.CO;2

van der Maarel E. and van der Maarel-Versluys M. (1996). Distribution and conservation status of littoral vascular plant species along the European coasts. J. Coast. Conserv. 2, 73–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02743039

van Kleunen M., Dawson W., Essl F., Pergl J., Winter M., Weber E., et al. (2015). Global exchange and accumulation of non-native plants. Nature. 525, 100–103. doi: 10.1038/nature14910

Varone L., Catoni R., Bonito A., Gini E., and Gratani L. (2017). Photochemical performance of Carpobrotus edulis in response to various substrate salt concentrations. S. Afr. J. Bot. 111, 258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2017.03.035

Verlaque R., Affre L., Diadema K., Suehs C. M., and Médail F. (2011). Unexpected morphological and karyological changes in invasive Carpobrotus (Aizoaceae) in Provence (S-E France) compared to native South African species. C. R. Biol. 334, 311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2011.01.008

Vieites-Blanco C., Retuerto R., Lado L., and Lema M. (2020). Potential distribution and population dynamics of Pulvinariella mesembryanthemi, a promising biocontrol agent of the invasive plant species Carpobrotus edulis and C. aff. acinaciformis. Entomol. Gen. 40, 173–185. doi: 10.1127/entomologia/2020/0758

Weber E. and D’Antonio C. M. (1999). Germination and growth responses of hybridizing Carpobrotus species (Aizoaceae) from coastal California to soil salinity. Am. J. Bot. 86, 1257–1263. doi: 10.2307/2656773

Zedda L., Cogoni A., Flore F., and Brundu G. (2010). Impacts of alien plants and man-made disturbance on soil-growing bryophyte and lichen diversity in coastal areas of Sardinia (Italy). Plant Biosyst. 144, 547–562. doi: 10.1080/11263501003638604

Zeng F., Shabala S., Maksimović J. D., Maksimović V., Bonales-Alatorre E., Shabala L., et al. (2018). Revealing mechanisms of salinity tissue tolerance in succulent halophytes: a case study for Carpobrotus rossi. Plant Cell Environ. 41, 2654–2667. doi: 10.1111/pce.13391

Zenni R. D., Essl F., García-Berthou E., and McDermott S. M. (2021). “The economic costs of biological invasions around the world,” in The economic costs of biological invasions around the world, vol. 67 . Eds. Zenni R. D., McDermott S., García-Berthou E., and Essl. F. (Sofia, Bulgaria: NeoBiota), 1–9. doi: 10.3897/neobiota.67.69971

Keywords: Carpobrotus acinaciformis (L.) L.Bolus, Carpobrotus edulis (L.) N.E.Br., psammophilous vegetation and flora, biological invasion, invasive species management, short-term recovery, invasive species eradication, aerosol salinity

Citation: Maccioni A, Dessena S, Morittu S, Padedda BM and Farris E (2025) Effects of the coastal salt gradient on the removal of the invasive clonal plants Carpobrotus sp. pl. (Aizoaceae) in a Mediterranean dune ecosystem. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6:1730419. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1730419

Received: 22 October 2025; Accepted: 25 November 2025; Revised: 20 November 2025;

Published: 15 December 2025.

Edited by:

David W. Inouye, University of Maryland, United StatesReviewed by:

Rodolfo Gentili, University of Milano-Bicocca, ItalyAngela Stanisci, University of Molise, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Maccioni, Dessena, Morittu, Padedda and Farris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alfredo Maccioni, YWxmcmVkb21hY2Npb25pODdAZ21haWwuY29t

†ORCID: Alfredo Maccioni, orcid.org/0000-0002-9266-9523

Bachisio Mario Padedda, orcid.org/0000-0002-0988-5613

Emmanuele Farris, orcid.org/0000-0002-9843-5998

Alfredo Maccioni

Alfredo Maccioni Simone Dessena1

Simone Dessena1 Bachisio Mario Padedda

Bachisio Mario Padedda Emmanuele Farris

Emmanuele Farris