- Leicester School of Pharmacy, De Montfort University, Leicester, United Kingdom

Transdermal drug delivery (TDD) provides a non-invasive approach for sustained drug release. However, traditional models present limitations in capturing the dynamic interactions between drugs, skin and the environmental factors over time. The incorporation of time as a critical dimension alongside three-dimensional (3D) structures in four-dimensional (4D) modelling offers a promising solution by simulating the temporal evolution of drug diffusion and skin responses. In this review, 4D modelling refers to the computational and material-based systems that incorporate time-dependent changes whereas 4D bioprinting specifically involves fabrication of dynamic, stimuli-responsive skin constructs. Together, these approaches create temporally adaptive models which are ideal for simulating drug permeation and skin behaviour. This review will explore the potential application of 4D modelling in TDD, primarily focusing on and emphasising its capacity to predict drug permeation, release kinetics and skin interactions in response to variables such as hydration, temperature and mechanical impact. 4D bioprinting provides a more accurate depiction of real-world scenarios, enabling researchers to optimise drug formulations whilst minimising reliance on empirical testing. Despite challenges associated with cost and complexity, 4D modelling presents considerable opportunities, particularly in the advancement of personalised medicine. The integration of artificial intelligence could further enhance these models, resulting in more accurate predictions. By addressing both spatial and temporal dimensions, 4D constructs will continue to evolve and have the potential to transform TDD; particularly in the context of individualised treatment where dynamic patient-specific variables can be integrated to develop more effective and tailored treatments.

1 Introduction

Developments in technology and material science has transformed existing drug delivery methods, eliminating the limitations of traditional approaches. Transdermal Drug Delivery (TDD) is already an established route of administration that enables systemic or local drug delivery through the skin and TDD has steadily gained traction in drug delivery research due to being non-invasive, achieving various active-release kinetics and by-passing first-pass metabolism. Compared to existing routes of administration such as oral and parenteral approaches, TDD provides improved patient compliance particularly for long-term therapies. Despite these benefits, TDD presents some challenges including limitations in drug penetration, irritation and unpredictable interactions with the skins’ dynamic properties and this in turn has implications in its application (Vaseem et al., 2024).

Traditional 2D and 3D models have been extensively used to study these challenges alongside skin-drug interactions (Wang et al., 2021). While these models have significantly contributed to our understanding of the complexity of the skin, one of the biggest limitations is the inability to fully capture the dynamic nature of skin. The ever-changing barrier of human skin is continuously experiencing physiological changes which are influenced by a multitude of factors such as hydration levels, intrinsic ageing, and exposure to environmental stressors (Joshi et al., 2020; Ramezani and Mohd Ripin, 2023). This non-exhaustive list of factors plays a critical role in the efficiency of drug permeation through the skin to reach the targeted tissue. For example, dehydrated skin or a loss in moisture can result in a decrease in drug permeability in turn hindering absorption of therapeutic actives (Brito et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2023; Tapfumaneyi et al., 2025). Similarly, intrinsic and actinic ageing can modify lipid composition, collagen density and barrier function of the skin, affecting drug diffusion rate across the skin (Lee et al., 2023). In addition to this, factors and stresses such as exposure to UV radiation, air pollution and to an extent circadian rhythms can trigger biochemical-based responses which can affect skin permeability. It is these real-time physiological adaptations that 2D and 3D models fail to replicate and therefore cannot accurately represent behaviour of formulations when applied to actual human skin under various conditions.

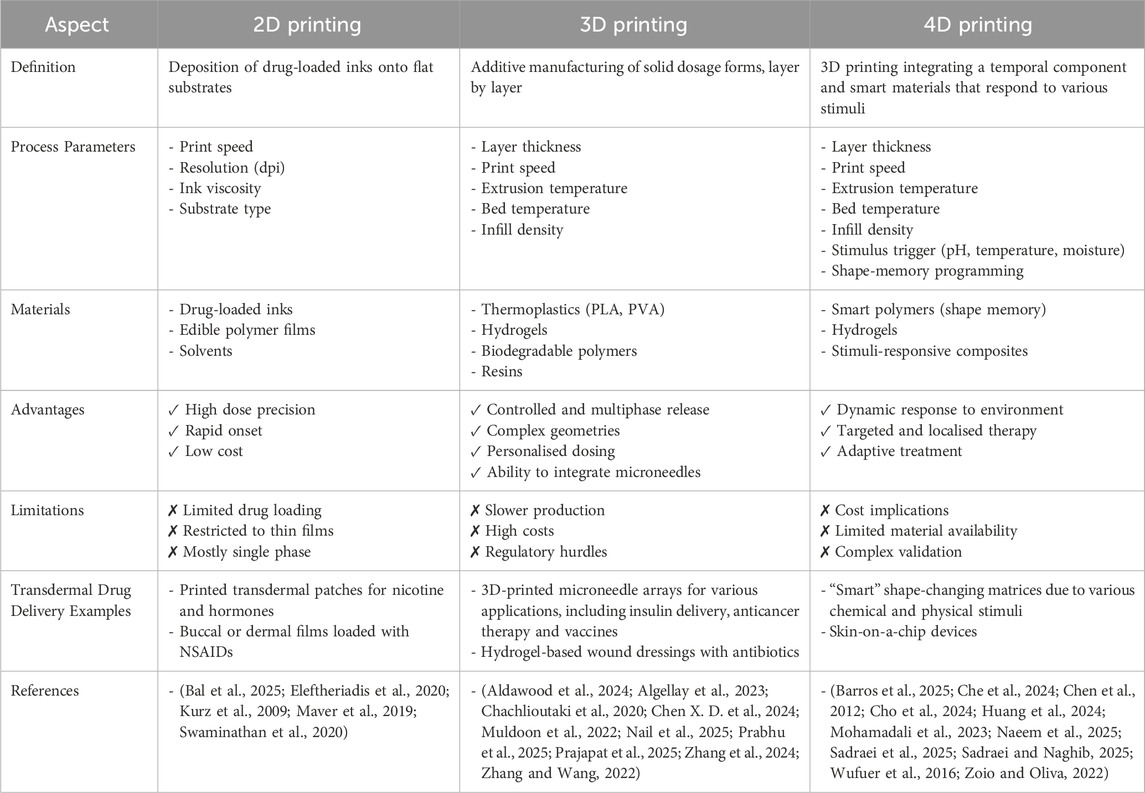

This gap in modelling highlights the need for more advanced biomimetic approaches to enhance simulation of the constant-changing characteristics of the skin to enhance the precision of TDD studies. The emergence of 4D skin models is a ground-breaking advancement, which encompasses the study of skin biology and drug delivery (Aftab et al., 2025; Alanazi et al., 2025; Gazzaniga et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2015; Vehse et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018; Zu et al., 2022). As shown in Table 1, where traditional 2D and 3D models focus predominantly on static or structurally complex representations of skin, programmable 4D constructs integrate the dimension of time and smart materials, offering dynamic adaptability. This introduction of temporal responsiveness allows scientists to observe and analyse dynamic processes like ageing, wound healing and reparation of barrier function in ways that previously have not been possible and can therefore provide deeper insights into drug diffusion rates, retention and overall efficacy (Joshi et al., 2020; Martinez-De-Anda et al., 2023). By capturing these temporal changes, 4D scaffolds portray a much more accurate simulation of how human skin behaves in real-word conditions (Martinez-De-Anda et al., 2023).

Table 1. Comparison of key features, materials and applications of 2D, 3D and 4D printing in transdermal drug delivery.

Unlike previous reviews that focus primarily on materials or printing techniques, this mini-review will show how 4D bioprinting and dynamic skin models directly advance TDD applications. The impact of these on various parameters such as release kinetics and patient-specific modelling will be evaluated while identifying current gaps in translation and proposing future research priorities.

2 Advances in 4D bioprinted constructs for drug delivery applications

Conventional 2D and 3D skin models lack the capability to mimic temporal changes in barrier function, hydration, deformation and ageing. As a result, they cannot replicate dynamic drug diffusion pathways which in turn limits their predictive value in TDD research. Technological advances like 4D bioprinting can overcome these limitations.

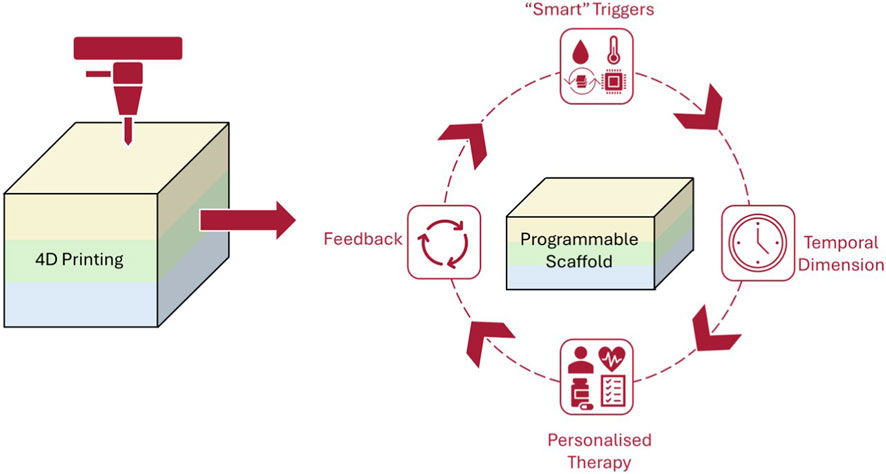

Bioprinting is an advanced manufacturing method that utilises bioinks, composed of living cells, biomaterials and growth factors, to fabricate tissue-like structures layer by layer (Mendoza-Cerezo et al., 2023; Tripathi et al., 2023). Unlike traditional printing, bioprinting aims to replicate the architecture and functionality of biological tissues, resulting in complex, stratified constructs such as skin equivalents (Dey and Ozbolat, 2020; Mendoza-Cerezo et al., 2023). As shown in Figure 1, 4D printing combines smart biomaterials and time-dependent triggers to create adaptive scaffolds for personalised models. Bioprinting also provides precise spatial control over cell placement and material composition, allowing researchers to design programmable scaffolds that mimic native skin properties. More importantly, these technological advances have direct relevance to TDD as by enabling controlled temporal changes in architecture, hydration and matrix mechanics, 4D constructs can replicate the evolving skin barrier more accurately than static 3D models. This improved biomimicry then provides opportunity to evaluate drug permeation and release behaviour under physiologically dynamic conditions, as opposed to relying solely on static end-point measurements (Ashammakhi et al., 2018; Chen J. et al., 2024; Faber et al., 2024; Noroozi et al., 2023; Shie et al., 2019).

Figure 1. Conceptual schematic of 4D printing workflow, highlighting how programmable scaffolds respond to smart triggers and temporal changes to enable dynamic and personalised therapy with integral feedback mechanisms.

2.1 Advances in 4D bioprinting techniques

2.1.1 Printing methods and process control

The evolution of bioprinting methods has considerably helped to advance 4D skin models (Aftab et al., 2025; Ashammakhi et al., 2018; Damiati et al., 2025; Gao et al., 2016; Kalogeropoulou et al., 2024; Kuang et al., 2019; Morouço et al., 2020; Noroozi et al., 2023; Yarali et al., 2024). Extrusion-based bioprinting remains the most used technique in skin modelling, predominantly due to its ability to accurately deposit highly viscous cell-laden bioinks (Ahn et al., 2023; Ghosh et al., 2025; He et al., 2025; Perez-Valle et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024). Similarly, inkjet printing is a popular approach due to high resolution and fast processing speeds; often used for patterning smaller biomolecules and cells (Arshad et al., 2020; Che et al., 2024; Ng et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2022). For more complex cell layering and spatial cellular arrangements, laser-assisted bioprinting is preferred as it offers the advantage of precise cell deposition without nozzle clogging (Chang and Sun, 2023; Douillet et al., 2022; Ishack and Lipner, 2020). For example, Douillet et al. developed fibroblast-collagen lattices with the ability to modulate cell-generated tensions within the matrix (Douillet et al., 2022). The skin-equivalent scaffolds displayed both epidermal and dermal layers and remained viable for more than 40 days. The resulting printed construct initially presented as a soft cross-linked hydrogel scaffold but over time, the fibroblasts remodelled, contracting and reorganising the matrix. Using 4D laser-printing techniques enabled real-time monitoring of the hydrogel polymerisation and cell placement; converting a static pattern into a living tissue that adapts its mechanical properties and architecture.

Using such evolved techniques enables the development of stratified skin constructs that can change and evolve overtime whilst mimicking crucial skin structural components such as dermal-epidermal junctions and microvascular networks.

2.1.2 Cellular integration and functionalisation

Arguably, the most crucial aspect of 4D modelling stems from the integration of significant cellular components such as keratinocytes and fibroblasts. By adding dynamic, time-dependent triggers that can be tuned to each patient’s cellular and extracellular matrix profile, the field of personalised medicine can be transformed (Zablotskii et al., 2016).

Cells like keratinocytes and fibroblasts are fundamental due to the role they play in epidermal and dermal function (Douillet et al., 2022). As the evolution in material science and processes continues, the inclusion of immune-based cellular components such as Langerhan cells and macrophages has enhanced the responsiveness of 4D models to stimuli related to inflammation and immunogenicity; a crucial output to evaluate with respect to drug irritation and allergenicity studies (Koti et al., 2019). By utilising patient-derived immunological components and by developing programmable scaffolds with specific stiffness, degradation rates and biochemical gradients, researchers can mimic the personalised biomechanical and signaling environment of individual skin. The ongoing integration of vascular and neuron-based elements represents the next stage toward fully functional skin equivalents.

2.2 Smart biomaterials and stimuli integration in 4D skin models

The use of advanced technologies has not been the only factor to contribute to the development of 4D models.

Unlike processes that build on static, 3D concepts to mimic the structural complexity of skin tissue, 4D bioprinting incorporates a temporal element to allow for the constant dynamic responses to external stimuli (Li et al., 2017). This innovative approach can enable skin constructs to replicate how the skin adapts to various environmental stimuli such as temperature, humidity, and mechanical impact (Kim et al., 2024; Murphy and Atala, 2014; Ramezani and Mohd Ripin, 2023; Tran et al., 2022). Whilst there has been great interest in this field, there has been limited pharmaceutics-based published works in this area (Firth et al., 2018; Trenfield et al., 2019).

2.2.1 Material innovations driving 4D bioprinting

The core of 4D bioprinting focuses on the use of “smart” biomaterials capable of responding to various stimuli and allow for time-dependent responses in the printed constructs to be captured (Alanazi et al., 2025; Chen J. et al., 2024; Chu et al., 2020; Ding et al., 2025; Mahmoud and Schulz-Siegmund, 2023; Naeem et al., 2025; Tibbits, 2014; Wang et al., 2025; Wu et al., 2025).

Hydrogels have been widely used in drug delivery systems for many years due to their high-water content and biocompatibility (Ma et al., 2024; Mohammadzadeh et al., 2025; Qutub et al., 2025; Sadraei and Naghib, 2025; Toews et al., 2025; Zöller et al., 2025). The ability to also personalise or optimise the physical properties of these “smart” materials has also made them a popular drug delivery matrix (Dai et al., 2019; Naficy et al., 2017; Narupai et al., 2021; Sadraei et al., 2025; Wu et al., 2025; Zu et al., 2022). Hydrogels can be engineered to be triggered to swell, shrink and change shape in response to environmental changes such as pH (Li et al., 2016; Mirani et al., 2017; Vijayavenkataraman et al., 2018), temperature (Abdullah and Okay, 2023; Thakur et al., 2023) or even the presence of enzymes (Ashammakhi et al., 2018; Cui et al., 2019; Nadgorny et al., 2016; Sadraei et al., 2025; Shie et al., 2019; Tran et al., 2022).

Another classification of “smart” materials includes shape-memory Polymers (SMPs) (Wei et al., 2017). Following deformation due to exposure to specific triggers (e.g., temperature, pH), SMPs can revert to their original configuration, making these materials advantageous in skin modelling where controlled movement and structural transformation is essential to emulate physiological skin behaviours (Alam et al., 2023; Cerbe et al., 2024; Invernizzi et al., 2018; Kalogeropoulou et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2015; Narupai et al., 2021; Pisani et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2019).

Che et al. developed an innovative approach to fabricating microneedles using hydroxybutyl methacrylated chitosan (HBC-MA) using 3D printing (Che et al., 2024). HBC-MA possesses dual temperature and photo-sensitive properties which enabled the microneedles to change dimensions when exposed to different temperatures in turn improving their mechanical strength. This will allow the chitosan-based device to load, deliver and sustain the release of small molecular drugs as well as penetrate soft tissue effectively. A novel system has also been designed that integrated pH-responsive porous “sensors” with gentamicin-loaded alginate stents (Mirani et al., 2017). This drug delivery platform enabled on demand antibiotic release where pH fluctuations triggered the release of gentamicin to target bacterial infections, demonstrating a promising approach for responsive and localised 4D-based drug delivery.

2.2.2 Dynamic environmental triggers in 4D models

In addition to smart materials, biomechanical and biochemical triggers are also becoming increasingly common in driving development of 4D models (Alanazi et al., 2025; Cabane et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2012; Ge et al., 2014; Roy et al., 2010; Talebian et al., 2019; Yin et al., 2014). Properties such as tension, elasticity and viscoelasticity must be considered during drug delivery modelling to account for the mechanical compliance of human skin (Aizarna-Lopetegui et al., 2025; Sutterby et al., 2022). These variables determine how the skin barrier deforms and recovers following stretching or compression. 4D models have the ability to incorporate external mechanical cues such as cyclic stretching or pressure to reproduce the physical exertion acting on human skin. Kaiser et al. presented a pneumatically driven skin-on-a-chip platform which coupled automated media perfusion with cyclic uniaxial compression and stretching. The scaffolds here saw an increase in the proteins associated with cell junctions in epithelial tissues (Claudin-1 and desmoplakin 1 and 2) under mechanical stimulation; highlighting stronger tight-junction and desmosome formation (Kaiser et al., 2024). Being able to assess these variables can help evaluate drug penetration under movement or during mechanical stress; an important factor often overlooked in static 3D models.

Alongside this, biochemical gradients, growth factors and signalling molecules can help set up a bioactive environment by guiding cell differentiation and immune responses to support skin behaviour on a cellular level (Imrie and Jin, 2025; Lai et al., 2025; Lai et al., 2024; Mathur et al., 2025). By integrating these dynamic stimuli in 4D constructs, it allows for more accurate predictions of inflammation, wound healing and allergic reactions in a controlled setting (Alanazi et al., 2025; Talebian et al., 2019).

2.3 Applications of 4D skin models in drug delivery

From a drug delivery perspective, the incorporation of time-dependent material and cellular responses fundamentally alters release kinetics and permeation. Temporal shifts in scaffold porosity, hydration state and mechanical stress can influence the effective diffusion coefficient within the construct and can either accelerate or delay permeation. These 4D-mediated changes can aid researchers in reviewing how formulations behave under realistic fluctuations in skin barrier function for example, by assessing temperature-responsive diffusion or hydration dependent flux.

2.3.1 Enhancing drug delivery and permeation studies

The accuracy and precision of studies involving drug permeation in transdermal research has significantly improved with the implementation of 4D skin models. Comparative studies between 4D and 2D and 3D models show that while the latter provide the foundational understandings of tissue-engineered skin constructs, they fail to take into consideration the temporal aspects required to fully simulate skin processes. Traditional 2D models cannot account for the restructure of the skin barrier following impairment whereas 4D models can actively replicate the disruptions in the skin barriers as well as the recovery phases which inherently increases the reliability of the resulting absorption data.

An example of using machine learning modelling is the development of thermo-responsive 4D constructs which were evaluated using paracetamol as a model drug (Suryavanshi et al., 2023). Physiochemical analysis of the constructs revealed high entrapment efficiency (98.11% ± 1.5%) with uniform drug distribution throughout the 4D-printed matrix. In vitro release studies demonstrated complete and rapid release of paracetamol, reaching nearly 100% within 4 h at physiological temperature.

2.3.2 Dynamic modelling of skin conditions

The ability for 4D models to exhibit real-time dynamic changes including fluctuations in hydration, temperature and pH is a key strength of such models. For example, dynamic hydration modelling can allow researchers to investigate Transepidermal Water Loss (TEWL) and how moisture loss and/or accumulation affects drug flux through the stratum corneum (Kundu et al., 2025). In a similar context, thermo-responsive materials can also help to simulate skin responses to thermal changes such as heat exposure, allowing for the study of temperature-dependent drug permeation. This responsive nature in turn allows researchers to simulate pathophysiological conditions such as eczema and inflammation which would be limited in traditional static models (Wufuer et al., 2016).

The use of 4D skin models has also extended to personalised medicine. Kapoor et al. reviewed the use of traditional 3D printing technologies with the aim to develop customised drug delivery systems which tailored to individualised patient needs (Kapoor et al., 2025).

2.3.3 Integration with microfluidic systems

More innovative techniques and methods have emerged in recent years to demonstrate the full potential of 4D systems in transdermal delivery. Integrated microfluidic systems and sensor-loaded scaffolds allow for real time monitoring of drug diffusion and skin metabolism (Zoio and Oliva, 2022). Wufuer et al. (2016) developed a microfluidic skin-on-a-chip model capable of reproducing critical physiological responses such as inflammation-induced permeability changes which allowed the continuous measurement of drug absorption without the need to extract tissue (Wufuer et al., 2016).

A pumpless microfluidic skin-on-a-chip system using a full-thickness Human Skin Equivalent (HSE) model has also been developed (Abaci et al., 2016). The ability for this approach to maintain skin barrier function for 3 weeks allowed comparative links to be made to in vivo skin permeation data and therefore make more accurate predictions of real time monitoring of drug diffusion. Similarly, Mohamadali et al. engineered a skin-on-a-chip pumpless microfluidic device with polydimethylsiloxane microchannels (Mohamadali et al., 2023). Tissue culture studies showed promising results with the microfluidic system enhancing viability of the full-thickness skin samples for at least 7 days under controlled conditions. The nature of microfluidic-based devices enables kinetic parameters such as lag time, peak flux and steady-state permeation to be measured accurately with non-invasive analysis.

The kinetic readouts generated on-chip are the most powerful and useful when paired with high-resoluton, non-invasive imaging that helps to close the loop between continuous measurements and structural validation. By coupling these microfluidic systems with advanced imaging technologies like confocal microscopy and optical coherence tomography (OCT), it also possible to visualise drug distribution in situ and tissue changes over time. Confocal laser scanning microscopy has already shown it can present high-resolution maps off fluorescent markers and marked formulations across skin layers which when coupled with microfluidic systems can enhance the accuracy of non-invasive collected data. Similarly, OCT offers non-destructive imaging of structural and functional changes during in vitro testing which can help determine chemical distribution in soft tissues ((Belsey et al., 2023).

Overall, the shift from static 2D/3D constructs to dynamic 4D skin models gives benefits across multiple drug delivery parameters. Temperature responsive systems demonstrate approximately 2-fold increase in drug flux with a controlled 10 °C rise in skin surface temperature, consistent with documented activation energies for stratum corneum diffusion (Chen J. et al., 2024; LaCount et al., 2020). Similarly, dynamic hydration modelling indicates that permeability increases sharply above 75% relative humidity, reflecting physiologically relevant shifts in barrier function (Oftadeh et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2026). Microfluidic 4D skin-on-chip systems provide real-time kinetic outputs in turn improving accuracy in lag time estimation and steady-state permeation which are not achievable in static diffusion cells (Mohamadali et al., 2023; Zuieva et al., 2022). These measurable differences underpin the translational value of 4D models for predicting drug diffusion under real-world dynamically evolving s.

In combination, dynamic modelling (to reproduce time-dependent changes in hydration, temperature and mechanics), microfluidic systems (to capture real-time permeation kinetics) and advanced imaging (to localise drug distribution and confirm structural changes in-situ) demonstrates a predictive, patient-focused platform for TDD optimisation, linking evolving skin physiology to quantified permeation metrics, enhancing formulation optimisation for TDD.

3 Future perspectives and conclusion

Whilst the advancements highlighted in this mini-review show promise, significant challenges still exist with regards to reproducing and more specifically standardising 4D models in transdermal drug delivery. Variability in bioprinting process parameters (such as printing pressure, bioink rheology, and cell-culture timing) present reproducibility hurdles that complicate cross-laboratory comparisons (Perez-Valle et al., 2020). Current assessments of 3D skin bioprinting scrutinises the techniques and protocols required for these processes and concerns are amplified when temporal parameters are introduced. The introduction of time as another dimension adds a layer of complexity that may hinder high-throughput screening and scalability too. Cho et al. emphasised that there is a specific need for robust development protocols and validation frameworks for collation of consistent, reliable data suggesting that integration with microfluidic technologies and sensor systems could enhance throughput and real-time monitoring (Cho et al., 2024).

4D modelling goes beyond technical evolution. By adding dynamic, patient-specific factors, these models can bridge the gap between laboratory studies and clinical testing. They reduce the need for animal experiments and support ethical standards under the NC3Rs (Replacement. Reduction and Refinement). As seen in this review, 4D systems outperform traditional 3D models and simulations by capturing both spatial and time-based changes, leading to more accurate predictions of drug absorption in real-world conditions. In an ever-evolving world of technology and with the rapid emergence of artificial intelligence, the TDD remit is being revolutionised using machine learning to predict drug release and behaviour and to develop personalised drug delivery systems; combining predictive modelling with real-time monitoring (Sabbagh et al., 2025). Despite these advantages, high costs, limited scalability and unclear regulations are slowing wider adoption of these systems. Several innovations in bioprinting and 3D printing have progressed beyond preliminary research with clear differences in commercial readiness and future translational outlook (Vijayavenkataraman, 2023). Poieskin® from Poietis represents the most advanced example where a bioprinted autologous full thickness skin model has been commercialised solely for laboratory research with ongoing clinical development (Abellan Lopez et al., 2023). Similarly, L’Oreal’s bioprinted skin models have reached a stable research phase and has seen routine use for cosmetics and chemical testing; an alternative to animal testing (Girard et al., 2024). The dual-layered model has the ability to replicate the complexity of real human skin, including skin conditions, ability to heal from injury and also to tan. Full thickness skin constructs developed by Wake Forest Institute remains in the pre-clinical phase, however, there has been rapid progress in vascularisation strategies which suggests movement towards early phase clinical evaluation once reproducibility can be addressed (Jorgensen et al., 2025). At present, there are no dedicated regulations for 4D bioprinted skin-based drug delivery systems. Regulation evaluation relies on existing frameworks that govern medical devices, combination products or advanced therapy medical products, depending on material, cellular composition and intended clinical use (Demoly et al., 2021). Despite this, increased understanding of the regulations associated with 3D printed medical products, prior approval of constituent biomaterials and advances in standardisation and quality control can be expected to facilitate clinical translation of 4D bioprinting technologies in the near future. Future work in this remit depends on close collaboration between material scientists, bioengineers and regulators and should focus on combining 4D models with artificial intelligence and machine learning to improve prediction accuracy (Damiati et al., 2025; Pugliese and Regondi, 2022). Linking these systems with microfluidic platforms and imaging tools will allow non-invasive, real-time monitoring. New stimuli like biochemical gradients, circadian rhythms and immune response models could make these 4D systems more physiologically relevant.

In conclusion, while technical and regulatory challenges remain, combining 4D modelling with smart biomaterials, AI-driven analytics and integrated monitoring can reshape transdermal drug delivery. By enabling personalised, efficient, ethically responsible drug delivery strategies, 4D bioprinting and modelling represents a paradigm shift that could redefine the future of pharmaceutical development.

Author contributions

PM: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Validation, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abaci, H. E., Guo, Z., Coffman, A., Gillette, B., Lee, W. H., Sia, S. K., et al. (2016). Human skin constructs with spatially controlled vasculature using primary and iPSC-Derived endothelial cells. Adv. Healthc. Mat. 5, 1800–1807. doi:10.1002/adhm.201500936

Abdullah, T., and Okay, O. (2023). 4D printing of body temperature-responsive hydrogels based on poly(acrylic acid) with shape-memory and self-healing abilities. ACS Appl. Bio Mat. 6, 703–711. doi:10.1021/acsabm.2c00939

Abellan Lopez, M., Hutter, L., Pagin, E., Vélier, M., Véran, J., Giraudo, L., et al. (2023). In vivo efficacy proof of concept of a large-size bioprinted dermo-epidermal substitute for permanent wound coverage. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1217655. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2023.1217655

Aftab, M., Ikram, S., Ullah, M., Khan, S. U., Wahab, A., and Naeem, M. (2025). Advancement of 3D bioprinting towards 4D bioprinting for sustained drug delivery and tissue engineering from biopolymers. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 9, 285. doi:10.3390/jmmp9080285

Ahn, M., Cho, W. W., Lee, H., Park, W., Lee, S. H., Back, J. W., et al. (2023). Engineering of uniform epidermal layers via sacrificial gelatin bioink-assisted 3D extrusion bioprinting of skin. Adv. Healthc. Mat. 12, e2301015. doi:10.1002/adhm.202301015

Aizarna-Lopetegui, U., Bittinger, S. C., Álvarez, N., Henriksen-Lacey, M., and Jimenez de Aberasturi, D. (2025). Stimuli-responsive hybrid materials for 4D in vitro tissue models. Mat. Today bio. 33, 102035. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.102035

Alam, F., Ubaid, J., Butt, H., and El-Atab, N. (2023). Swift 4D printing of thermoresponsive shape-memory polymers using vat photopolymerization. NPG Asia Mater 15, 65. doi:10.1038/s41427-023-00511-x

Alanazi, B. N., Ahmed, H. A., Alharbi, N. S., Ebrahim, N. A. A., and Soliman, S. M. A. (2025). Exploring 4D printing of smart materials for regenerative medicine applications. RSC Adv. 15, 32155–32171. doi:10.1039/d5ra04410c

Aldawood, F. K., Parupelli, S. K., Andar, A., and Desai, S. (2024). 3D printing of biodegradable polymeric microneedles for transdermal drug delivery applications. Pharmaceutics 16, 237. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16020237

Algellay, M., Roberts, M., Bosworth, L., Sarker, S. D., Fatokun, A. A., and Ehtezazi, T. (2023). The use of micro-ribbons and micro-fibres in the formulation of 3D printed fast dissolving oral films. Pharmaceuticals 16, 79. doi:10.3390/ph16010079

Arshad, M. S., Shahzad, A., Abbas, N., AlAsiri, A., Hussain, A., Kucuk, I., et al. (2020). Preparation and characterization of indomethacin loaded films by piezoelectric inkjet printing: a personalized medication approach. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 25, 197–205. doi:10.1080/10837450.2019.1684520

Ashammakhi, N., Ahadian, S., Zengjie, F., Suthiwanich, K., Lorestani, F., Orive, G., et al. (2018). Advances and future perspectives in 4D bioprinting. Biotechnol. J. 13, 1800148. doi:10.1002/biot.201800148

Bal, I., Macit, M., Alasiri, A., Namli, O. C., Arshad, M. S., Ahmad, Z., et al. (2025). Engineering moxifloxacin-encapsulated liposome-enriched alginate hydrogel films. Gels 11, 448. doi:10.3390/gels11060448

Barros, N. R., Kang, R., Kim, J., Ermis, M., Kim, H. J., Dokmeci, M. R., et al. (2025). A human skin-on-a-chip platform for microneedling-driven skin cancer treatment. Mat. Today Bio 30, 101399. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2024.101399

Belsey, N. A., Dexter, A., Vorng, J. L., Tsikritsis, D., Nikula, C. J., Murta, T., et al. (2023). Visualisation of drug distribution in skin using correlative optical spectroscopy and mass spectrometry imaging. J. Control. Release 364, 79–89. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.10.026

Brito, S., Baek, M., and Bin, B. H. (2024). Skin structure, physiology, and pathology in topical and transdermal drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 16, 1403. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16111403

Cabane, E., Zhang, X., Langowska, K., Palivan, C. G., and Meier, W. (2012). Stimuli-responsive polymers and their applications in nanomedicine. Biointerphases 7, 9. doi:10.1007/s13758-011-0009-3

Cerbe, F., Sinapius, M., and Böl, M. (2024). Methodology for FDM 4D printing with thermo-responsive SMPs. Mat. Today Proc. 101, 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2022.11.440

Chachlioutaki, K., Tzimtzimis, E. K., Tzetzis, D., Chang, M. W., Ahmad, Z., Karavasili, C., et al. (2020). Electrospun orodispersible films of isoniazid for pediatric tuberculosis treatment. Pharmaceutics 12. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics12050470

Chang, J., and Sun, X. (2023). Laser-induced forward transfer based laser bioprinting in biomedical applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1255782. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2023.1255782

Che, Q. T., Seo, J. W., Charoensri, K., Nguyen, M. H., Park, H. J., and Bae, H. (2024). 4D-printed microneedles from dual-sensitive chitosan for non-transdermal drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 261, 129638. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129638

Chen, M., Huang, C., He, C., Zhu, W., Xu, Y., and Lu, Y. (2012). A glucose-responsive controlled release system using glucose oxidase-gated mesoporous silica nanocontainers. Chem. Commun. 48, 9522–9524. doi:10.1039/C2CC34290A

Chen, J., Virrueta, C., Zhang, S., Mao, C., and Wang, J. (2024). 4D printing: the spotlight for 3D printed smart materials. Mater. Today 77, 66–91. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2024.06.004

Chen, X. D., Zhang, X. Y., Zhu, H. Q., Lu, H. H., and Wang, M. (2024). Three-dimensional printing of hydrogel blend tissue engineering scaffolds with in situ delivery of anticancer drug for treating melanoma resection-induced tissue defects. J. Funct. Biomater. 15, 381. doi:10.3390/jfb15120381

Cho, S. W., Malick, H., Kim, S. J., and Grattoni, A. (2024). Advances in Skin-on-a-Chip technologies for dermatological disease modeling. J. Investigative Dermatology 144, 1707–1715. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2024.01.031

Chu, H., Yang, W., Sun, L., Cai, S., Yang, R., Liang, W., et al. (2020). 4D printing: a review on recent progresses. Micromachines (Basel) 11. doi:10.3390/MI11090796

Cui, H., Miao, S., Esworthy, T., Lee, S., Zhou, X., Hann, S. Y., et al. (2019). A novel near-infrared light responsive 4D printed nanoarchitecture with dynamically and remotely controllable transformation. Nano Res. 12, 1381–1388. doi:10.1007/s12274-019-2340-9

Dai, W., Guo, H., Gao, B., Ruan, M., Xu, L., Wu, J., et al. (2019). Double network shape memory hydrogels activated by near-infrared with high mechanical toughness, nontoxicity, and 3D printability. Chem. Eng. J. 356, 934–949. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2018.09.078

Damiati, L. A., Alsudir, S. A., Mohammed, R. Y., Majrashi, M. A., Albrahim, S. H., algethami, A., et al. (2025). 4D printing in skin tissue engineering: a revolutionary approach to enhance wound healing and combat infections. Bioprinting 45, e00386. doi:10.1016/j.bprint.2025.e00386

Demoly, F., Dunn, M. L., Wood, K. L., Qi, H. J., and André, J. C. (2021). The status, barriers, challenges, and future in design for 4D printing. Mat. Des. 212, 110193. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2021.110193

Dey, M., and Ozbolat, I. T. (2020). 3D bioprinting of cells, tissues and organs. Sci. Rep. 10, 14023. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-70086-y

Ding, A., Tang, F., and Alsberg, E. (2025). 4D printing: a comprehensive review of technologies, materials, stimuli, design, and emerging applications. Chem. Rev. 125, 3663–3771. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.4c00070

Douillet, C., Nicodeme, M., Hermant, L., Bergeron, V., Guillemot, F., Fricain, J. C., et al. (2022). From local to global matrix organization by fibroblasts: a 4D laser-assisted bioprinting approach. Biofabrication 14. doi:10.1088/1758-5090/ac40ed

Eleftheriadis, G. K., Monou, P. K., Bouropoulos, N., Boetker, J., Rantanen, J., Jacobsen, J., et al. (2020). Fabrication of mucoadhesive buccal films for local administration of Ketoprofen and lidocaine hydrochloride by combining fused deposition modeling and inkjet printing. J. Pharm. Sci. 109, 2757–2766. doi:10.1016/j.xphs.2020.05.022

Faber, L., Yau, A., and Chen, Y. (2024). Translational biomaterials of four-dimensional bioprinting for tissue regeneration. Biofabrication 16, 012001. doi:10.1088/1758-5090/acfdd0

Firth, J., Gaisford, S., and Basit, A. W. (2018). “A new dimension: 4D printing opportunities in pharmaceutics,” in 3D printing of pharmaceuticals. Editors A. W. Basit, and S. Gaisford (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 153–162. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-90755-0_8

Gao, B., Yang, Q., Zhao, X., Jin, G., Ma, Y., and Xu, F. (2016). 4D bioprinting for biomedical applications. Trends Biotechnol. 34, 746–756. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.03.004

Gazzaniga, A., Foppoli, A., Cerea, M., Palugan, L., Cirilli, M., Moutaharrik, S., et al. (2023). Towards 4D printing in pharmaceutics. Int. J. Pharm. X. 5, 100171. doi:10.1016/j.ijpx.2023.100171

Ge, Q., Dunn, C. K., Qi, H. J., and Dunn, M. L. (2014). Active origami by 4D printing. Smart Mat. Struct. 23, 094007. doi:10.1088/0964-1726/23/9/094007

Ghosh, E., Rego, G. P., Ghosh, R. N., Sahithi, V. B., Poojary, D. P., Namboothiri, P. K., et al. (2025). Advances in in situ bioprinting: a focus on extrusion and inkjet-based bioprinting techniques. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. doi:10.1007/s40883-025-00420-1

Girard, F., Lajoye, C., Camman, M., Tissot, N., Berthelot Pedurand, F., Tandon, B., et al. (2024). First advanced bilayer scaffolds for tailored skin tissue engineering produced via electrospinning and melt electrowriting. Adv. Funct. Mat. 34, 2314757. doi:10.1002/adfm.202314757

He, C. F., Qiao, T. H., Wang, G. H., Sun, Y., and He, Y. (2025). High-resolution projection-based 3D bioprinting. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 3, 143–158. doi:10.1038/s44222-024-00218-w

Huang, T., Sun, Z., Heath, D. E., O’Brien-Simpson, N., and O’Connor, A. J. (2024). 3D printed and smart alginate wound dressings with pH-responsive drug and nanoparticle release. Chem. Eng. J. 492, 152117. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.152117

Imrie, P., and Jin, J. (2025). 4D bioprinting: keeping the technology alive. Macromol. Mat. Eng. 310, 2400386. doi:10.1002/mame.202400386

Invernizzi, M., Turri, S., Levi, M., and Suriano, R. (2018). 4D printed thermally activated self-healing and shape memory polycaprolactone-based polymers. Eur. Polym. J. 101, 169–176. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2018.02.023

Ishack, S., and Lipner, S. R. (2020). A review of 3-Dimensional skin bioprinting techniques: applications, approaches, and trends. Dermatol. Surg. 46, 1500–1505. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002378

Jorgensen, A. M., Gorkun, A., Mahajan, N., Willson, K., Clouse, C., Jeong, C. G., et al. (2025). Multicellular bioprinted skin facilitates human-like skin architecture in vivo. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eadf7547. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.adf7547

Joshi, S., Rawat, K., C, K., Rajamohan, V., Mathew, A. T., Koziol, K., et al. (2020). 4D printing of materials for the future: opportunities and challenges. Appl. Mat. Today 18, 100490. doi:10.1016/j.apmt.2019.100490

Kaiser, K., Bendixen, S. M., Sørensen, J. A., and Brewer, J. R. (2024). From static to dynamic: the influence of mechanotransduction on skin equivalents analyzed by bioimaging and RNAseq. Mat. Today Bio 25, 101010. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2024.101010

Kalogeropoulou, M., Díaz-Payno, P. J., Mirzaali, M. J., van Osch, G. J. V. M., Fratila-Apachitei, L. E., and Zadpoor, A. A. (2024). 4D printed shape-shifting biomaterials for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Biofabrication. doi:10.1088/1758-5090/ad1e6f

Kapoor, D. U., Pareek, A., Uniyal, P., Prajapati, B. G., Thanawuth, K., and Sriamornsak, P. (2025). Innovative applications of 3D printing in personalized medicine and complex drug delivery systems. iScience 28, 113505. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2025.113505

Kim, J., D A, G., Debnath, P., and Saha, P. (2024). Smart multi-responsive biomaterials and their applications for 4D bioprinting. Biomimetics 9, 484. doi:10.3390/biomimetics9080484

Koti, P., Muselimyan, N., Mirdamadi, E., Asfour, H., and Sarvazyan, N. A. (2019). Use of GelMA for 3D printing of cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. J. 3D Print. Med. 3, 11–22. doi:10.2217/3dp-2018-0017

Kuang, X., Roach, D. J., Wu, J., Hamel, C. M., Ding, Z., Wang, T., et al. (2019). Advances in 4D printing: materials and applications. Adv. Funct. Mat. 29, 1805290. doi:10.1002/adfm.201805290

Kundu, D., Jayaraman, A., and Sen, C. K. (2025). Clinical measurement of transepidermal water loss HHS public access. Adv. Wound Care (New Rochelle). doi:10.1089/wound.2024.0148

Kurz, A., Farlow, M., and Lefèvre, G. (2009). Pharmacokinetics of a novel transdermal rivastigmine patch for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 63, 799–805. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02052.x

LaCount, T. D., Zhang, Q., Hao, J., Ghosh, P., Raney, S. G., Talattof, A., et al. (2020). Modeling temperature-dependent dermal absorption and clearance for transdermal and topical drug applications. AAPS J. 22, 70. doi:10.1208/s12248-020-00451-2

Lai, J., Liu, Y., Lu, G., Yung, P., Wang, X., Tuan, R. S., et al. (2024). 4D bioprinting of programmed dynamic tissues. Bioact. Mat. 37, 348–377. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2024.03.033

Lai, J., Xiong, T., Chen, S., Zhou, Z., Liu, J., Yang, B., et al. (2025). Facile single-nanocomposite 4D bioprinting of dynamic hydrogel constructs with thickness-controlled gradient. Adv. Sci. 12, e09449. doi:10.1002/advs.202509449

Lee, D. H., Lim, S., Kwak, S. S., and Kim, J. (2023). Advancements in skin-mediated drug delivery: mechanisms, techniques, and applications. Adv. Healthc. Mat. 13, e2302375. doi:10.1002/adhm.202302375

Li, H., Go, G., Ko, S. Y., Park, J. O., and Park, S. (2016). Magnetic actuated pH-responsive hydrogel-based soft micro-robot for targeted drug delivery. Smart Mat. Struct. 25, 027001. doi:10.1088/0964-1726/25/2/027001

Li, Y. C., Zhang, Y. S., Akpek, A., Shin, S. R., and Khademhosseini, A. (2017). 4D bioprinting: the next-generation technology for biofabrication enabled by stimuli-responsive materials. Biofabrication 9, 012001. doi:10.1088/1758-5090/9/1/012001

Liu, Y., Li, Y., Yang, G., Zheng, X., and Zhou, S. (2015). Multi-stimulus-responsive shape-memory polymer nanocomposite network cross-linked by cellulose nanocrystals. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 7, 4118–4126. doi:10.1021/am5081056

Ma, X., Sekhar, K. P. C., Zhang, P., and Cui, J. (2024). Advances in stimuli-responsive injectable hydrogels for biomedical applications. Biomater. Sci. 12, 5468–5480. doi:10.1039/D4BM00956H

Mahmoud, D. B., and Schulz-Siegmund, M. (2023). Utilizing 4D printing to design smart gastroretentive, esophageal, and intravesical drug delivery systems. Adv. Healthc. Mat. 12, 2202631. doi:10.1002/adhm.202202631

Martinez-De-Anda, A. A., Rodríguez-Salvador, M., and Castillo-Valdez, P. F. (2023). The attractiveness of 4D printing in the medical field: revealing scientific and technological advances in design factors and applications. Int. J. Bioprint. doi:10.36922/ijb.1112

Mathur, V., Agarwal, P., Kasturi, M., Varadharajan, S., Devi, E. S., and Vasanthan, K. S. (2025). Transformative bioprinting: 4D printing and its role in the evolution of engineering and personalized medicine. Discov. Nano 20, 118. doi:10.1186/s11671-025-04230-w

Maver, T., Mohan, T., Gradišnik, L., Finšgar, M., Kleinschek, K. S., and Maver, U. (2019). Polysaccharide thin solid films for analgesic drug delivery and growth of human skin cells. Front. Chem. 7, 217. doi:10.3389/fchem.2019.00217

Mendoza-Cerezo, L., Rodríguez-Rego, J. M., Macías-García, A., Marcos-Romero, A. C., and Díaz-Parralejo, A. (2023). Evolution of bioprinting and current applications. Int. J. Bioprint. 9. doi:10.18063/ijb.742

Mirani, B., Pagan, E., Currie, B., Siddiqui, M. A., Hosseinzadeh, R., Mostafalu, P., et al. (2017). An advanced multifunctional hydrogel-based dressing for wound monitoring and drug delivery. Adv. Healthc. Mat. 6, 1700718. doi:10.1002/adhm.201700718

Mohamadali, M., Ghiaseddin, A., Irani, S., Amirkhani, M. A., and Dahmardehei, M. (2023). Design and evaluation of a skin-on-a-chip pumpless microfluidic device. Sci. Rep. 13, 8861. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-34796-3

Mohammadzadeh, V., Atapour-Mashhad, H., Shahvali, S., Salehi, B., Shaban, M., Shirzad, M., et al. (2025). Hydrogels as advanced drug delivery platforms for cancer immunotherapy: promising innovations and future outlook. J. Nanobiotechnology 23, 545. doi:10.1186/s12951-025-03613-6

Morouço, P., Azimi, B., Milazzo, M., Mokhtari, F., Fernandes, C., Reis, D., et al. (2020). Four-dimensional (Bio-)printing: a review on stimuli-responsive mechanisms and their biomedical suitability. Appl. Sci. Switz. doi:10.3390/app10249143

Muldoon, K., Song, Y., Ahmad, Z., Chen, X., and Chang, M. W. (2022). High precision 3D printing for micro to nano scale biomedical and electronic devices. Micromachines (Basel) 13, 642. doi:10.3390/mi13040642

Murphy, S. V., and Atala, A. (2014). 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 773–785. doi:10.1038/nbt.2958

Nadgorny, M., Xiao, Z., Chen, C., and Connal, L. A. (2016). Three-dimensional printing of pH-Responsive and functional polymers on an affordable desktop printer. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 8, 28946–28954. doi:10.1021/acsami.6b07388

Naeem, A., Yu, C., Zhou, L., Xie, Y., Weng, Y., Huang, Y., et al. (2025). Shape memory hydrogels in tissue engineering: recent advances and challenges. Bioact. Mat. 54, 215–247. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2025.08.009

Naficy, S., Gately, R., Gorkin, R., Xin, H., and Spinks, G. M. (2017). 4D printing of reversible shape morphing hydrogel structures. Macromol. Mat. Eng. 302, 1600212. doi:10.1002/mame.201600212

Nail, A., Liu, H., Meng, D., Zhu, L., Guo, X., Li, C., et al. (2025). 3D-printed insulin/GOx-loaded ZIF-8 microneedles via hydrogen-bond-enhanced photopolymerization for transdermal drug delivery. Surfaces Interfaces 72, 107005. doi:10.1016/j.surfin.2025.107005

Narupai, B., Smith, P. T., and Nelson, A. (2021). 4D printing of multi-stimuli responsive protein-based hydrogels for autonomous shape transformations. Adv. Funct. Mat. 31, 2011012. doi:10.1002/adfm.202011012

Ng, W. L., Yeong, W. Y., and Naing, M. W. (2017). Polyvinylpyrrolidone-based bio-ink improves cell viability and homogeneity during drop-on-demand printing. Materials 10. doi:10.3390/ma10020190

Noroozi, R., Arif, Z. U., Taghvaei, H., Khalid, M. Y., Sahbafar, H., Hadi, A., et al. (2023). 3D and 4D bioprinting technologies: a game changer for the biomedical sector? Ann. Biomed. Eng. 51, 1683–1712. doi:10.1007/s10439-023-03243-9

Oftadeh, R., Azadi, M., Donovan, M., Langer, J., Liao, I. C., Ortiz, C., et al. (2023). Poroelastic behavior and water permeability of human skin at the nanoscale. PNAS Nexus 2, pgad240. doi:10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad240

Perez-Valle, A., Amo, C. D., and Andia, I. (2020). Overview of current advances in extrusion bioprinting for skin applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1–28. doi:10.3390/ijms21186679

Pisani, S., Genta, I., Modena, T., Dorati, R., Benazzo, M., and Conti, B. (2022). Shape-memory polymers hallmarks and their biomedical applications in the form of nanofibers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 1290. doi:10.3390/ijms23031290

Prabhu, A., Baliga, V., Shenoy, R., Dessai, A. D., and Nayak, U. Y. (2025). 3D printed microneedles: revamping transdermal drug delivery systems. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 15, 436–454. doi:10.1007/s13346-024-01679-7

Prajapat, M., Gholap, A. D., Shinde, S., Padhiyar, D., Butani, S., Shah, S., et al. (2025). 3D printing technology in microneedles: an emerging era in transdermal drug delivery. Hybrid. Adv. 10, 100447. doi:10.1016/j.hybadv.2025.100447

Pugliese, R., and Regondi, S. (2022). Artificial intelligence-empowered 3D and 4D printing technologies toward smarter biomedical materials and approaches. Polym. (Basel) 14, 2794. doi:10.3390/polym14142794

Qutub, M., Tatode, A., Taksande, J., Premchandani, T., Umekar, M., Hussain, U. M., et al. (2025). Stimuli-responsive supramolecular hydrogels for paclitaxel delivery: progress and prospects. Aspects Mol. Med. 5, 100062. doi:10.1016/j.amolm.2024.100062

Ramezani, M., and Mohd Ripin, Z. (2023). 4D printing in biomedical engineering: advancements, challenges, and future directions. J. Funct. Biomater. 14, 347. doi:10.3390/jfb14070347

Rossi, A., Pescara, T., Gambelli, A. M., Gaggia, F., Asthana, A., Perrier, Q., et al. (2024). Biomaterials for extrusion-based bioprinting and biomedical applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 12, 1393641. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2024.1393641

Roy, D., Cambre, J. N., and Sumerlin, B. S. (2010). Future perspectives and recent advances in stimuli-responsive materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 35, 278–301. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2009.10.008

Sabbagh, F., Zakrzewska, A., Rybak, D., Król, J., Abdi, A., Nakielski, P., et al. (2025). Transdermal drug delivery systems powered by artificial intelligence. Adv. Healthc. Mat. 14, e03030. doi:10.1002/adhm.202503030

Sadraei, A., and Naghib, S. M. (2025). 4D printing of physical stimuli-responsive hydrogels for localized drug delivery and tissue engineering. Polym. Rev. 65, 104–168. doi:10.1080/15583724.2024.2427184

Sadraei, A., Naghib, S. M., and Rabiee, N. (2025). 4D printing chemical stimuli-responsive hydrogels for tissue engineering and localized drug delivery applications – part 2. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 22, 491–510. doi:10.1080/17425247.2025.2466768

Shie, M. Y., Shen, Y. F., Astuti, S. D., Lee, A. K. X., Lin, S. H., Dwijaksara, N. L. B., et al. (2019). Review of polymeric materials in 4D printing biomedical applications. Polym. (Basel) 11. doi:10.3390/polym11111864

Suryavanshi, P., Wang, J., Duggal, I., Maniruzzaman, M., and Banerjee, S. (2023). Four-dimensional printed construct from temperature-responsive self-folding feedstock for pharmaceutical applications with machine learning modeling. Pharmaceutics 15, 1266. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15041266

Sutterby, E., Thurgood, P., Baratchi, S., Khoshmanesh, K., and Pirogova, E. (2022). Evaluation of in vitro human skin models for studying effects of external stressors and stimuli and developing treatment modalities. VIEW 3, 20210012. doi:10.1002/VIW.20210012

Swaminathan, S., Strasinger, C., Kelchen, M., Carr, J., Ye, W., Wokovich, A., et al. (2020). Determination of rate and extent of scopolamine release from transderm scōp® transdermal drug delivery systems in healthy human adults. AAPS PharmSciTech 21, 117. doi:10.1208/s12249-020-01658-4

Talebian, S., Mehrali, M., Taebnia, N., Pennisi, C. P., Kadumudi, F. B., Foroughi, J., et al. (2019). Self-healing hydrogels: the next paradigm shift in tissue engineering? Adv. Sci. 6, 1801664. doi:10.1002/advs.201801664

Tapfumaneyi, P., Phan, K., Huang, Y., Sodsri, K., Namjoshi, S., Maibach, H., et al. (2025). Solute–vehicle–skin interactions and their contribution to pharmacokinetics of skin delivery. Pharmaceutics 17, 764. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics17060764

Thakur, V., Singh, R., Kumar, R., and Gehlot, A. (2023). 4D printing of thermoresponsive materials: a state-of-the-art review and prospective applications. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 17, 2075–2094. doi:10.1007/s12008-022-01018-5

Tibbits, S. (2014). 4D printing: multi-material shape change. Archit. Des. 84, 116–121. doi:10.1002/ad.1710

Toews, P. M., Velraj, A., and Bates, J. S. (2025). Stimuli-responsive hydrogels, their mass transfer, intermolecular interactions, and applications in biomedical devices. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 20, 66. doi:10.1186/s40712-025-00283-y

Tran, T. S., Balu, R., Mettu, S., Roy Choudhury, N., and Dutta, N. K. (2022). 4D printing of hydrogels: innovation in material design and emerging smart systems for drug delivery. Pharmaceuticals 15, 1282. doi:10.3390/ph15101282

Trenfield, S. J., Awad, A., Madla, C. M., Hatton, G. B., Firth, J., Goyanes, A., et al. (2019). Shaping the future: recent advances of 3D printing in drug delivery and healthcare. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 16, 1081–1094. doi:10.1080/17425247.2019.1660318

Tripathi, S., Mandal, S. S., Bauri, S., and Maiti, P. (2023). 3D bioprinting and its innovative approach for biomedical applications. MedComm (Beijing) 4, e194. doi:10.1002/mco2.194

Vaseem, R. S., D’Cruz, A., Shetty, S., Vardhan, A., Shenoy, S. R., Marques, S. M., et al. (2024). Transdermal drug delivery systems: a focused review of the physical methods of permeation enhancement. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 14, 67–85. doi:10.34172/apb.2024.018

Vehse, M., Petersen, S., Sternberg, K., Schmitz, K. P., and Seitz, H. (2014). Drug delivery from poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate scaffolds produced by DLC based micro-stereolithography. Macromol. Symp. 346, 43–47. doi:10.1002/masy.201400060

Vijayavenkataraman, S. (2023). 3D bioprinting: challenges in commercialization and clinical translation. J. 3D Print. Med. 7. doi:10.2217/3dp-2022-0026

Vijayavenkataraman, S., Yan, W.-C., Lu, W. F., Wang, C.-H., and Fuh, J. Y. H. (2018). 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs for regenerative medicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 132, 296–332. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.004

Wang, Y., Miao, Y., Zhang, J., Wu, J. P., Kirk, T. B., Xu, J., et al. (2018). Three-dimensional printing of shape memory hydrogels with internal structure for drug delivery. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 84, 44–51. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2017.11.025

Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Aghda, N. H., Pillai, A. R., Thakkar, R., Nokhodchi, A., et al. (2021). Emerging 3D printing technologies for drug delivery devices: current status and future perspective. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 174, 294–316. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2021.04.019

Wang, Y., Yuan, X., Yao, B., Zhu, S., Zhu, P., and Huang, S. (2022). Tailoring bioinks of extrusion-based bioprinting for cutaneous wound healing. Bioact. Mat. 17, 178–194. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.01.024

Wang, C., Hu, C., Cheng, H., Qi, W., Wang, L., Wu, T., et al. (2024). A programmable handheld extrusion-based bioprinting platform for in situ skin wounds dressing: balance mobility and customizability. Adv. Sci. 11, e2405823. doi:10.1002/advs.202405823

Wang, Z., Zhang, Z., and Kuang, X. (2025). Recent advances in polymer 4D printing: 3D printing techniques, smart material design, and healthcare applications. Smart Mat. Med. 6, 305–333. doi:10.1016/j.smaim.2025.09.001

Wei, M., Gao, Y., Li, X., and Serpe, M. J. (2017). Stimuli-responsive polymers and their applications. Polym. Chem. 8, 127–143. doi:10.1039/c6py01585a

Wu, W., Wang, J., and Li, G. (2025). 3D/4D printing of stimuli-responsive polymers in biomedical engineering: materials, stimulations, and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 166, 101071. doi:10.1016/j.mser.2025.101071

Wufuer, M., Lee, G. H., Hur, W., Jeon, B., Kim, B. J., Choi, T. H., et al. (2016). Skin-on-a-chip model simulating inflammation, edema and drug-based treatment. Sci. Rep. 6, 37471. doi:10.1038/srep37471

Yarali, E., Mirzaali, M. J., Ghalayaniesfahani, A., Accardo, A., Diaz-Payno, P. J., and Zadpoor, A. A. (2024). 4D printing for biomedical applications. Adv. Mater. 36, e2402301. doi:10.1002/adma.202402301

Yin, R., Wang, K., Du, S., Chen, L., Nie, J., and Zhang, W. (2014). Design of genipin-crosslinked microgels from concanavalin A and glucosyloxyethyl acrylated chitosan for glucose-responsive insulin delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 103, 369–376. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.12.067

Yu, J., Xie, F., Gong, X., Chen, D., Niu, Y., Ping, Z., et al. (2026). 4D-Printed dual-functional hydrogels breaking the trade-off between rapid kinetics and ultrahigh water uptake for atmospheric water harvesting. Adv. Mater., e16698. doi:10.1002/adma.202516698

Zablotskii, V., Polyakova, T., Lunov, O., and Dejneka, A. (2016). How a high-gradient magnetic field could affect cell life. Sci. Rep. 6, 37407. doi:10.1038/srep37407

Zhang, Y., and Wang, C. (2022). Recent advances in 3D printing hydrogel for topical drug delivery. MedComm - Biomaterials Appl. 1, mba2.11. doi:10.1002/mba2.11

Zhang, B., Zhang, W., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Y.-F., Hingorani, H., Liu, Z., et al. (2019). Self-healing four-dimensional printing with an ultraviolet curable double-network shape memory polymer system. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 11, 10328–10336. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b00359

Zhang, S., Sims, J., Mehochko, I., Zolovick, R., Kwak, T., and Staples, A. (2024). Design and characterization of 3D-printed hollow microneedle arrays for transdermal insulin delivery. AIP Adv. 14, 065234. doi:10.1063/5.0204216

Zoio, P., and Oliva, A. (2022). Skin-on-a-Chip technology: microengineering physiologically relevant in vitro skin models. Pharmaceutics 14, 682. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics14030682

Zöller, K., To, D., and Bernkop-Schnürch, A. (2025). Biomedical applications of functional hydrogels: innovative developments, relevant clinical trials and advanced products. Biomaterials. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2024.122718

Zu, S., Wang, Z., Zhang, S., Guo, Y., Chen, C., Zhang, Q., et al. (2022). A bioinspired 4D printed hydrogel capsule for smart controlled drug release. Mat. Today Chem. 24, 100789. doi:10.1016/j.mtchem.2022.100789

Keywords: 4D printing, bioprinting, skin-on-a-chip, smart biomaterials, stimuli-responsive materials, transdermal delivery

Citation: Mehta P (2026) Advancing transdermal drug delivery through 4D bioprinting and dynamic skin modelling. Front. Drug Deliv. 6:1753384. doi: 10.3389/fddev.2026.1753384

Received: 24 November 2025; Accepted: 21 January 2026;

Published: 03 February 2026.

Edited by:

Zeeshan Ahmad, The University of Manchester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Leila Pakzad, Lakehead University, CanadaChristos Gioumouxouzis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Copyright © 2026 Mehta. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Prina Mehta, cHJpbmEubWVodGFAZG11LmFjLnVr

Prina Mehta

Prina Mehta