- 1Programa de Pós Graduação em Psicologia, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, Brazil

- 2Departamento de Psicologia Social e do Desenvolvimento, Programa de Pós Graduação em Psicologia, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, Brazil

The present study aimed to develop and provide validity evidence for the Dog–Human Attachment Scale (DHAS), designed to assess dogs’ attachment styles toward their caregivers. Content validity of the proposed items was confirmed by experts. To examine the internal structure of the instrument, data from 1,014 Brazilian dogs were analyzed based on owner responses to the DHAS, with 713 cases used for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and 301 for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Parallel analysis and exploratory factor analysis revealed a three-factor structure: Anxiety, Avoidance, and Insecurity, capturing distinct aspects of canine attachment. The CFA supported the adequacy of the three-factor model. Test–retest procedures demonstrated good temporal stability. Evidence of internal structure validity was found, including acceptable composite reliability and ordinal McDonald’s omega coefficients for all three factors, as well as no evidence of differential item functioning (DIF) across guardian gender. Finally, latent profile analysis based on participants’ scores on the three dimensions identified an optimal three-profile solution in the sample, corresponding to insecure-anxious (16.2%), disorganized (47.3%), and insecure-avoidant (36.5%) attachment styles. These findings highlight the utility of the DHAS in distinguishing variations in dog–human attachment patterns. The instrument offers a reliable and valid tool for advancing research and clinical practice, contributing to a deeper understanding of how attachment mechanisms shape canine emotional regulation and behavior in relation to caregivers and influence the quality of the human–dog relationship.

1 Introduction

Attachment theory has increasingly been applied to interspecies relationships, including the human–dog bond (de Souza et al., 2025a). Theoretical and empirical advances over the past two decades suggest that the emotional bond between dogs and their human caregivers may encompass key features of attachment, including proximity-seeking, distress during separation, and differential responses to the caregiver versus unfamiliar individuals (Mariti et al., 2013; Nagasawa et al., 2009; Palmer and Custance, 2008; Prato-Previde et al., 2003; Solomon et al., 2019; Topál et al., 1998).

The attachment functions of secure base and safe haven have been extensively observed in the relationship between dogs and their human caregivers (Cimarelli et al., 2021; Gácsi et al., 2013; Mariti et al., 2013; Palmer and Custance, 2008). These functions reflect distinct yet complementary aspects of attachment: the secure base enables the individual to explore the environment with confidence, supported by the presence of the attachment figure, while the safe haven becomes salient in situations involving stress or perceived threat, prompting the animal to seek proximity and comfort (Bowlby, 1969).

These behaviors emerge and stabilize over time, shaped by factors such as the caregiver’s emotional availability and consistency, as well as the dog’s previous experiences (Borrelli et al., 2022; Cimarelli et al., 2021; Völter et al., 2023). Such patterns suggest that dogs, like humans, display individual differences in attachment-related behaviors, potentially reflecting broader affective and relational tendencies.

Foundational studies, such as that of Topál et al. (1998), and subsequent research have adapted Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) (Ainsworth et al., 1978) to investigate attachment behaviors in dogs, providing strong empirical support for the application of attachment theory in this context. More recently, however, there have been efforts to develop alternative methods, particularly caregiver-report instruments, that offer greater flexibility and scalability while capturing the emotional and behavioral dynamics of the dog–human attachment bond (Riggio et al., 2021).

In line with these developments, the present study introduces the Dog–Human Attachment Scale (DHAS), a caregiver-report measure grounded in attachment theory but specifically developed from the perspective of canine behavior and everyday interactions with humans. The scale aims to identify dimensions of attachment that reflect individual differences in canine anxiety, insecurity or avoidance related behaviors across contexts such as separation, potentially stressful situations, and social engagement.

Attachment theory posits that the organization of early affective experiences within caregiving relationships gives rise to distinct regulatory strategies, manifesting as identifiable attachment patterns. Initially delineated in the context of infant–caregiver interactions via the SSP (Ainsworth et al., 1978), these patterns, secure, insecure-anxious (ambivalent), insecure-avoidant, and later, disorganized (Main and Solomon, 1986), reflect the dyadic calibration between proximity-seeking, effective comfort-seeking under stress, and affect regulation in response to separation and reunion. These attachment styles have since been extended to adult relationships and, more recently, to interspecific bonds.

A growing body of research suggests that dogs may also exhibit behavioral patterns consistent with the classical attachment styles in their relationships with human caregivers (Konok et al., 2015, 2019; Mariti et al., 2013; Palmer and Custance, 2008; Riggio et al., 2021; Solomon et al., 2019; Topál et al., 1998). In this sense, dogs with secure attachments tend to display greater exploratory behavior by using their guardians as a secure base and show lower stress reactivity by seeking them as a safe haven, whereas insecurely attached dogs may exhibit increased proximity seeking, heightened vigilance, or signs of distress during separations (Cimarelli et al., 2021; Konok et al., 2015; Topál et al., 1998).

Strategies for assessing attachment styles in dogs have largely drawn from instruments developed for humans, particularly children, and can be broadly categorized into direct behavioral observations and report-based questionnaires. In humans, key observational methods include the SSP (Ainsworth et al., 1978) and the Attachment Q-Sort (Waters and Deane, 1985), while analogous procedures have been adapted for dogs, focusing on responses to separation and reunion in unfamiliar contexts (Mariti et al., 2013; Palmer and Custance, 2008; Solomon et al., 2019; Topál et al., 1998). More recently, naturalistic, home-based observations have been proposed (Bentosela et al., 2024).

Self- and third-party report instruments are also widely used in both human and canine research. In humans, examples include the Adult Attachment Scale (AAS) (Collins and Read, 1990), the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) and Experiences in Close Relationships – Revised (ECR-R) (Brennan et al., 1998; Fraley and Shaver, 2000). For children there are the Attachment Insecurity Screening Inventory – AISI (Spruit et al., 2018; Wissink et al., 2016) and ECR-RCV, the revised child version (Brenning et al., 2014). The AAS, ECR, ECR-R, and ECR-RC adopt a dimensional approach, in which attachment styles are derived from the combination of continuous scores on dimensions such as anxiety, avoidance, and, in the case of the AAS, also dependence. Other instruments, such as the AISI, adopt a categorical model, classifying individuals directly into distinct attachment patterns based on specific response profiles. These conceptual differences may have important implications for how attachment is assessed and interpreted.

In dogs, caregiver-report questionnaires have been employed to estimate attachment patterns, although validated tools remain limited (Riggio et al., 2021). One such instrument is the Dog Attachment Insecurity Screening Inventory (D-AISI), adapted from the AISI to assess avoidant, anxious, and disorganized attachment behaviors in dogs toward their human caregiver. While offering a practical alternative to observational methods, its validation has thus far been restricted to an Italian sample of female dog owners (Riggio et al., 2021).

The interest in interspecific attachment led to the development of original instruments focusing on the caregiver’s perception of their relationship with their pet. One such instrument is the Pet Attachment Questionnaire (PAQ) (Zilcha-Mano et al., 2011), which was theoretically grounded in adult attachment models and developed through the adaptation of items from interpersonal and pet-related scales, as well as from interviews with pet owners, to specifically assess the caregiver’s attachment style toward their animal.

However, although the adaptation of human-based instruments is a common practice in interspecific research, this strategy may present challenges and limitations when applied to species with distinct behavioral repertoires. The Italian version of the D-AISI (Riggio et al., 2021), for example, raises questions regarding the adequacy of the contexts and behaviors it assesses. Some items require caregivers to interpret subtle and complex emotional or motivational states in dogs, such as concern. These items rely on subjective perceptions and attributions, which may be influenced by anthropomorphic biases.

Emphasizing observable behaviors in typical dog–human interactions may provide more concrete and reliable indicators. Although dogs are often seen as children or close companions, roles shaping caregiving and emotional expectations (Savalli and Mariti, 2020), the human–dog bond may involve species-specific behaviors not fully captured by child–caregiver models (Sipple et al., 2021). Reinforcing the complexity of interspecies attachment, Zilcha-Mano et al. (2012) showed that pets can serve as both safe haven and secure base for owners, with effects moderated by individual differences in pet-related attachment orientations. The authors stress the need to observe owner–pet interactions and assess pets’ own attachment orientations, recognizing the reciprocal and dynamic nature of these bonds.

The assessment of canine attachment styles is particularly relevant given emerging evidence that the quality of the attachment bond may mediate behavioral responses to caregiver absence, especially when such responses reach clinically significant levels, as observed in Canine Separation Anxiety (CSA) (Konok et al., 2015, 2019; Parthasarathy and Crowell-Davis, 2006). CSA is one of the most frequently reported forms of anxiety-related behavior by dog guardians, and caregiver absence is consistently identified as a major anxiety-inducing context. Recent evidence from a large Brazilian survey showed that being left alone was the second most frequently reported trigger of anxiety, cited by 20.2% of guardians (de Souza et al., 2025b). This highlights CSA as not only clinically relevant but also highly prevalent in everyday caregiving scenarios. CSA is a behavioral disorder that has received increasing attention in both clinical and scientific contexts due to its substantial impact on canine welfare and the human–dog relationship. It is typically defined as a condition in which dogs exhibit marked behavioral and physiological distress when separated from a specific attachment figure, most often the primary caregiver (Ballantyne, 2018; Ogata, 2016).

In light of this, the present study introduces and evaluates the Dog–Human Attachment Scale (DHAS), a novel caregiver-report instrument specifically designed to assess canine attachment behaviors in a theoretically grounded and ecologically valid manner. Rather than adapting existing human measures, the DHAS was developed from the ground up based on core dimensions of attachment theory and observable dog–human interactions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Item development of the DHAS

Based on the literature on canine attachment (Borrelli et al., 2022; Cimarelli et al., 2021; Konok et al., 2015, 2019; Mariti et al., 2013; Palmer and Custance, 2008; Riggio, 2020; Riggio et al., 2021; Sipple et al., 2021; Solomon et al., 2019; Topál et al., 1998; Völter et al., 2023), the first author’s professional experience as a dog trainer, and the second authors’ experience in behavioral observation, we developed thirty-seven items to assess canine behaviors associated with the dimensions of Anxiety and Avoidance in dog–owner interactions. The items were designed to capture behaviors related to anxiety and avoidance across a variety of potentially stressful contexts for dogs, such as separation from the owner, changes in routine, interactions in new or challenging environments, and interactions with other dogs and people, whether in the presence or absence of the owner. Additionally, the analysis took into account various aspects of the dog–owner relationship, including play, walks, and other daily activities.

Among the anxious behaviors assessed were excessive vocalization, barking, whining and/or howling, constant alertness, trembling, panting, scratching at doors, destruction of household objects, inappropriate elimination (urinating or defecating in unsuitable places), excessive salivation, and self-injury, among others. Avoidant behaviors included distancing, escape attempts, and lack of responsiveness when called or during interactions. Participants were asked to rate the degree to which each item applied to their dog’s behavior using a six-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (always).

The scale was structured based on a bidimensional model encompassing the dimensions of Anxiety and Avoidance, enabling the classification of attachment styles as proposed in the literature (Brennan et al., 1998; Zilcha-Mano et al., 2011). This classification reflects distinct emotional and behavioral regulation strategies toward the attachment figure and was presented to expert judges during the content validation stage.

2.2 Content validity evidence

The thirty-seven items of the DHAS were evaluated by a panel of four experts holding either a master’s or doctoral degree and possessing experience in psychometrics, attachment theory, animal behavior, and the human–animal bond. Prior to the evaluation, the judges were presented with a definition of canine attachment and the attachment styles, as described in the introduction of this article. They were also informed that the scale aimed to assess two main dimensions: anxiety, related to the dog’s stress and discomfort in the absence of the caregiver or in new and challenging situations; and avoidance, which reflects the dog’s level of distancing and resistance to contact with the caregiver.

The experts assessed the items based on five criteria: relevance to the scale (whether the item was related to the concept of canine attachment), relevance to the dimension (whether it appropriately corresponded to the dimension for which it was designed, Anxiety or Avoidance), clarity (whether it was understandable and free from ambiguity), simplicity (whether it was straightforward and easy to comprehend), and concreteness (whether it was specific and applicable to the caregiver’s experience with their dog). For each criterion, the judges responded to a dichotomous question, indicating agreement (yes) or disagreement (no) regarding the item under review. In addition, they were invited to suggest revisions and improvements, thereby contributing to the precision of the scale and its alignment with the study’s objectives.

Items that received suggestions for modification concerning clarity, simplicity, or concreteness were revised to ensure their adequacy. Moreover, items that received more than one vote of disagreement in the criteria of relevance to the scale or relevance to the dimension were considered candidates for removal and were subsequently analyzed to determine the necessity of exclusion. To test the validity of the DHAS, the items resulting from the expert evaluation were revised as needed and then administered to a sample of caregivers, following the procedures described in the subsequent sections.

2.3 Evidence of validity based on internal structure.

2.3.1 Participants

Dog owners residing in Brazil were invited to participate in this stage of the study. The inclusion criteria were being the owner of at least one dog, being over 18 years of age, residing in Brazil, and completing the questionnaire in full.

2.3.2 Instruments

An online questionnaire was used, consisting of the DHAS items resulting from expert evaluation, along with sociodemographic questions. Information was collected about both the dog owners and their dogs. Data regarding the owners included age, gender, marital status, educational level, income, presence of children, prior experience with dogs, ownership of other dogs or animals, number of people in the household, and both location and type of residence. In relation to the dogs, data were collected on age, breed, health history, origin, age at separation from the mother, training level, and neutering status. Additional information was gathered about the dogs’ routine, including walk frequency and duration, engagement in other physical activities, time spent alone, and whether they habitually slept in the owner’s bed.

2.3.3 Data collection procedures

The research instrument was made available through the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES) survey platform from November 14 to December 23, 2024. It was distributed via institutional email to university staff and students, shared through the researchers’ and the UFES Ethology Laboratory’s Instagram accounts, and disseminated via WhatsApp to contacts and groups. Participants were instructed to complete one questionnaire per dog in cases where they owned multiple dogs and wished to report on each. Participants could also provide their email address if they wished to participate in the test–retest phase. The test–retest data collection occurred from January 23 to February 3, 2025. The Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) data collection occurred from June 12 to July 12, 2025 and followed the same procedures as the initial data collection.

2.3.4 Evidence of validity based on internal structure: EFA

The dataset was prepared for analysis. We assessed the suitability of the DHAS data for factor analysis, and items with excessive kurtosis that impaired model performance were removed. Items with a high percentage of missing data were also excluded; these referred to situations that caregivers indicated did not apply to their dogs. In addition, items were excluded due to participant´s feedback indicating difficulties in interpretation. This feedback was gathered through an open-ended question at the end of the survey. Remaining missing data were handled using listwise deletion in all subsequent analyses. Before conducting the factor analysis, reverse-coded items were recoded so that higher scores consistently reflected higher levels of attachment-related behaviors. This preprocessing step ensured the interpretability and coherence of the factor structure.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted with the remaining 26 items to evaluate the factorial structure of the DHAS. The adequacy of the data for factor analysis was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. To determine the number of factors to retain, a Parallel Analysis based on the Minimum Rank Factor Analysis method was conducted using polychoric correlation matrices with 500 random permutations (Timmerman and Lorenzo-Seva, 2011). The factorial structure was then examined using the same type of correlation matrix and the Robust Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (RDWLS) estimation method, appropriate for ordinal and non-normally distributed data (Lorenzo-Seva and Ferrando, 2023). Factor rotation was performed using the Robust Promin procedure (Lorenzo-Seva and Ferrando, 2019).

Model fit was assessed using the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI). According to the literature, RMSEA values ≤ 0.08 and CFI and TLI values above 0.90 indicate acceptable model fit (Hoyle and Gottfredson, 2023). Additional fit indices, including the Root Mean Square Residual (RMSR) and the Weighted Root Mean Square Residual (WRMR), were also examined to provide further insight into model-data fit. RMSR values close to or below 0.05 are considered indicative of good fit, and WRMR values below 1.0 are recommended as indicators of acceptable fit (Yu and Muthén, 2002).

2.3.5 Test–retest reliability

Test–retest reliability was assessed by administering the instrument at two time points, with a 30-day interval between the end of the first data collection and the start of the second. Temporal stability was estimated using the intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC(3,1)], and Pearson correlations between the two administrations were also calculated. Confidence intervals were obtained via bootstrapping with 1,000 resamples.

2.3.6 Evidence of validity based on internal structure: CFA

Based on the items that loaded on the three factors identified in the EFA, a CFA was conducted to examine whether the factorial structure was supported in an independent sample and under a more restrictive model without cross-loadings, as is characteristic of CFA. The CFA was performed using ordinal data and the Robust Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (RDWLS) estimation method.

Model fit was evaluated using the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI). According to the literature, RMSEA values ≤ 0.08 and CFI and TLI values above 0.90 indicate acceptable model fit (Hoyle and Gottfredson, 2023).

Using the same sample, factor reliability was assessed using ordinal McDonald’s omega coefficient (ω). In line with contemporary recommendations, no single fixed cutoff value was assumed for omega; however, values above approximately 0.60 are commonly considered acceptable in the context of psychometric scales developed for research purposes (Kalkbrenner, 2024). Omega estimates were computed using the reliability() function from the semTools package, based on polychoric correlation matrices. Similarly, composite reliability was calculated as a complementary indicator of internal consistency and interpreted using the same cautious rationale: although no fixed cutoff value exists for this index, values above approximately 0.60 have been suggested by some authors as indicative of acceptable reliability in research contexts, particularly when considered alongside other reliability evidence (Valentini and Damásio, 2016).

2.3.7 Initial evidence of measure invariance

Differential item functioning (DIF) was examined to evaluate whether items functioned equivalently across guardian gender groups, following the CFA of the final measurement model. DIF analyses were conducted using ordinal logistic regression models implemented within the difNLR framework, specifically through the difORD function (Drabinová and Martinková, 2017; Hladká and Martinková, 2020; Hladká et al., 2025). This approach is grounded in generalized nonlinear logistic models (GLNMs) and detects DIF by comparing nested models using likelihood-ratio tests.

Both uniform DIF (i.e., constant differences between groups across the latent continuum) and non-uniform DIF (i.e., group differences that vary as a function of the trait level) can be tested within this framework. Given the ordinal nature of the items, cumulative logit models were fitted, using standardized observed scores as the matching criterion to approximate the underlying latent trait. p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. DIF analyses were conducted separately for each factor.

2.4 Latent profile analysis

In order to investigate whether participants’ scores reflected the attachment styles described in the literature, we conducted a Latent Profile Analysis (LPA). Factor scores were calculated for the dimensions of the DHAS resulting from EFA, considering only complete cases (listwise deletion), in order to ensure greater robustness and interpretability of the results. The scores were calculated by summing participants’ responses for each dimension of the scale.

The exploration of the optimal number of profiles was conducted estimating models with up to four classes in order to identify the point of stability in fit indices (AIC, SABIC, BIC, LogLik), as recommended by Akogul and Erisoglu (2017).

LPA is a model-based probabilistic mixture approach that identifies unobserved subgroups based on response patterns on continuous indicators. The model assumes that the observed data arise from a finite mixture of latent profiles, each characterized by distinct parameter estimates. Profile-specific means and, depending on model specification, variances and covariances are estimated. Individuals are assigned to profiles probabilistically based on posterior membership probabilities, and profile interpretation relies on comparisons of within-profile parameter estimates (Williams and Kibowski, 2016; Yang et al., 2022).

2.5 Software

Exploratory Factor Analyses (EFA) were conducted using the Factor software (version 12.06.08; Ferrando and Lorenzo-Seva, 2017). All other statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.4.2; R Core Team, 2024) through graphical user interfaces that operate as front ends for R, including JASP (version 0.95.4; JASP Team, 2024) for descriptive statistics and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and jamovi (version 2.7; jamovi, 2024) for latent profile analysis (LPA) and differential item functioning (DIF) analyses.

3 Results

3.1 Evidence of content validity

All items received agreement from at least three judges across all evaluated criteria, and twenty-five items received unanimous agreement across all criteria from the four judges. The only exception was the item “DHASH10. Your dog remains calm and relaxed when you take them to the veterinarian,” which received disagreement from two judges regarding its relevance to the scale and to the proposed dimension (Anxiety). One judge noted that the item could be extremely aversive, thereby compromising the assessment of attachment system activation. However, we chose to retain it in the scale for the internal structure analysis phase, given the item’s relevance in assessing attachment-related behaviors across a range of contexts, from less to more stressful, thus ensuring broader coverage of the latent trait. This decision was supported by our preliminary studies, which indicated that other assessed situations, such as separation from the caregiver, tend to be reported as more anxiety-inducing for Brazilian dogs than visits to the veterinarian. Therefore, the instrument remained composed of thirty-seven items at this stage, including 24 items assessing Anxiety and 13 items assessing Avoidance (the complete list of items is available in the Supplementary Materials).

3.2 Evidence of validity based on internal structure: EFA

The questionnaire received 1,136 responses; however, only 713 responses, each referring to a single dog, met all inclusion criteria and were included in the analyses. The average age of the dog owners was 37.9 years. Most participants identified as female (82.7%), were married or in a stable union (47.5%), had no children (74.9%), and held a graduate-level degree (57.1%). Additionally, 39.6% reported a household income between two and six minimum wages, most were employed (71%), and lived in houses (57.4%) located in urban areas (94.2%), predominantly in the Southeast region of Brazil (68.9%). The average number of people per household was 2.6. Most participants reported being their dog’s primary caregiver (51.6%) and the person responsible for walks (40.7%). The majority stated that they had only one dog (58.6%), that this was not their first pet (74.2%), and that they did not own other non-canine pets (70.3%).

Regarding the dogs, caregivers reported that most were companion dogs (97.6%), female (52.7%), mixed breed (52.7%), spayed or neutered (67.3%), vaccinated annually (93.8%), and without chronic illnesses (81.9%). Additionally, 37% of the dogs had been adopted. The average age of the dogs was 6 years, with an average weight of 14 kg. Most dogs had no formal training (57.4%) and were walked, on average, four times per week. Furthermore, 74.5% of the dogs did not engage in any physical activities other than walks. The majority of owners indicated that the walks lasted less than one hour (60.5%). On average, the dogs were left alone for four hours per day, and most slept in their caregiver’s bed (50.9%).

Several items were removed based on statistical and contextual criteria. Items DHAS28, and DHAS34 with excessive kurtosis, which adversely affected model fit, were excluded. Items DHAS7, DHAS9, DHAS11, DHAS18, DHAS21, DHAS37 were also excluded due to high percentages of missing responses, as they corresponded to scenarios not applicable to many dogs, such as traveling or use of daycare and grooming services. In addition, DHAS17 and DHAS29 were excluded due to elevated missing data and interpretability issues raised through open-ended participant feedback. Respondents often misunderstood these items as referring to leaving the dog unsupervised for several days, leading to confusion and inconsistent response patterns. DHAS1 was also excluded due to a technical error that prevented one of its response categories from being displayed.

Following initial data screening, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted with 26 items. The suitability of the data for factor analysis was confirmed by a significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ² = 2499.0, df = 190; p < 0,001), indicating that the correlation matrix was not an identity matrix. Additionally, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0,76, which is considered acceptable.

Parallel analysis revealed that the first three eigenvalues of the real data accounted for 23.5%, 11.9%, and 9.1% of the variance, respectively. These values exceeded the 95th percentile of variances explained by eigenvalues derived from simulated random data, supporting the retention of three factors due to their significantly greater explained variance compared to what would be expected by chance.

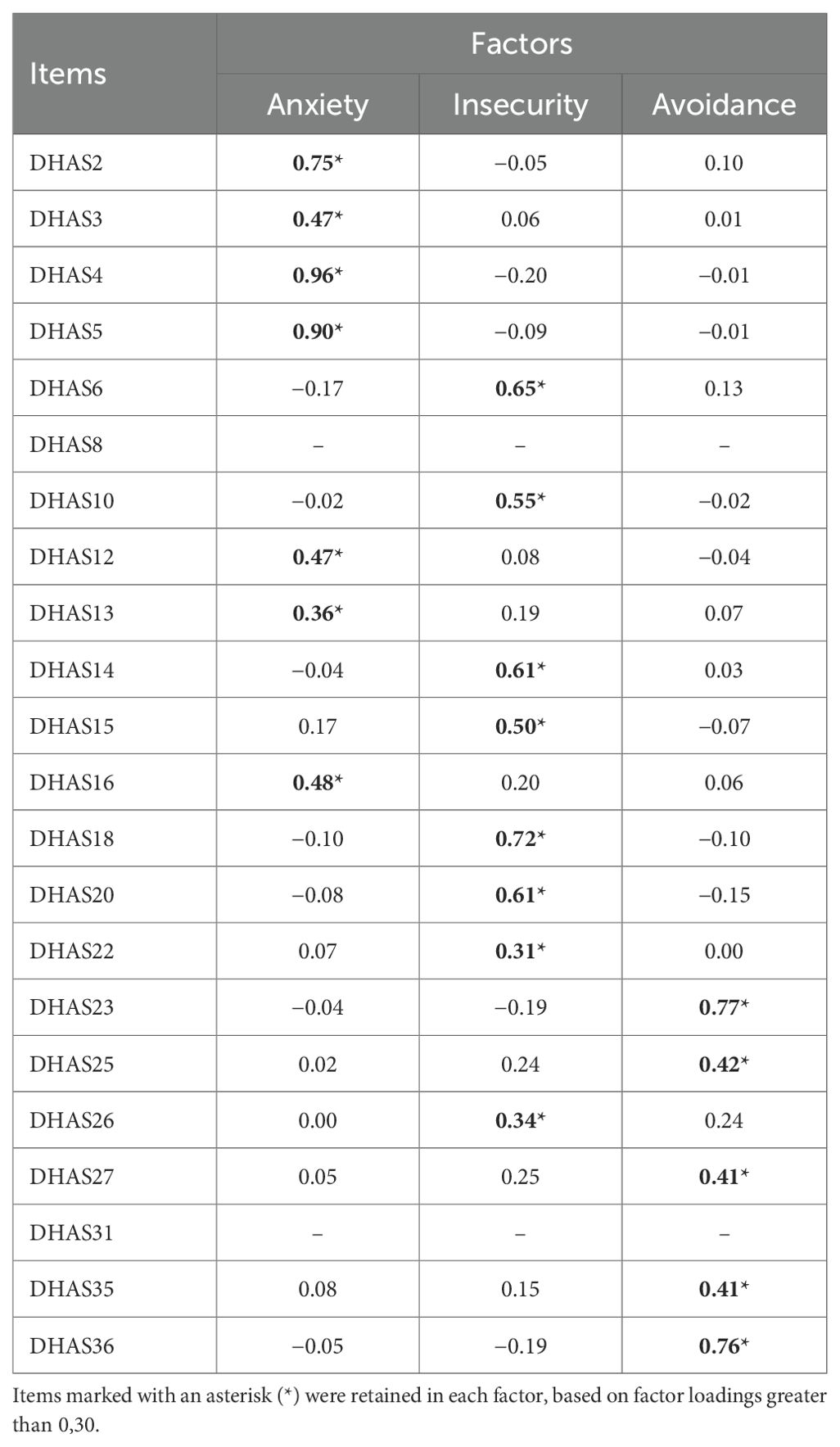

The Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted with three factors. However, item DHAS8 displayed a cross-loading pattern above 0,30 on both the Anxiety and Insecurity factors, and items DHAS24, DHAS30, DHAS31, DHAS32, and DHAS33 did not exhibit satisfactory factor loadings. These items were therefore removed. A new parallel analysis, conducted with the remaining twenty items, again supported the retention of three factors. The new eigenvalues (25.9%, 13.6%, 10.8%) remained above those expected under randomness, confirming the three-factor structure. We then repeated the EFA procedures with three factors, and all 20 remaining items showed adequate loadings.

In the resulting three-factor model, items loading on the Anxiety and Avoidance factors remained consistent with the structure proposed in the content validation phase. A third factor, Insecurity, emerged, grouping items that describe emotional instability in stressful, novel, or social situations, even in the presence of the caregiver. Although not initially hypothesized, this factor demonstrated good reliability and theoretical coherence and was therefore retained in subsequent analyses. The items composing the Insecurity factor were originally designed to measure Anxiety but revealed a distinct dimension, potentially common among dogs with insecure-anxious or insecure-avoidant profiles. In this model, the combination of scores across the three dimensions is intended to identify four attachment style patterns: insecure-anxious (high scores on Anxiety and Insecurity, low Avoidance), insecure-avoidant (high Avoidance and Insecurity, low Anxiety), disorganized (high on all three dimensions), and secure (low overall scores). Table 1 presents the factor loadings of each item grouped by factor.

The model fit indices demonstrated acceptable fit, RMSEA = 0,060, 95% BCa CI [0,055, 0,062]; TLI = 0,93, 95% BCa CI [0,91, 0,95]; and CFI = 0,96, 95% BCa CI [0,94, 0,97], RMSR = 0,060, 95% BCa CI [0,058, 0,060]; and WRMR = 0,054, 95% BCa CI [0,052, 0,056], all within recommended thresholds (< 1,0) (Yu and Muthén, 2002). These results confirm the robustness of the model, including the incorporation of the Insecurity factor, which, although not initially hypothesized, proved to be theoretically coherent and statistically reliable. Thus, the fit indices provide consistent empirical support for retaining the three-dimensional model in subsequent analyses.

3.3 Test–retest reliability

A total of 214 individuals accessed the instrument during the test–retest phase, of whom 112 completed all the questionnaire at both time points and were included in the analyses. The DHAS demonstrated good temporal stability, with adequate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC3,1): Anxiety factor (ICC = 0,76, 95% CI [0,67, 0,83]), Insecurity factor (ICC = 0,86, 95% CI [0,80, 0,90]), and Avoidance factor (ICC = 0,77, 95% CI [0,68, 0,84]). Pearson correlations with BCa bootstrapping also indicated strong associations between the two time points: Anxiety factor (r = 0,78, 95% BCa CI [0,67, 0,86]), Insecurity factor (r = 0,86, 95% BCa CI [0,80, 0,90]), and Avoidance factor (r = 0,77, 95% BCa CI [0,65, 0,85]).

3.4 Evidence of validity based on internal structure: CFA

A total of 301 dogs, each belonging to a different caregiver, were included in the CFA analysis. The dogs’ average age was 6,27 years (SD = 3,93). Most were male (54,5%), mixed-breed (52,5%), neutered (65,8%), and vaccinated annually (95,0%). The majority did not present chronic health conditions (81,7%).

Regarding their guardians, most respondents identified as women (81,4%), with a mean age of 36,87 years (SD = 12,80). They were predominantly single (49,8%), without children (73,8%), and reported having no other pets (61,8%) or dogs (72,8%). A large proportion had completed postgraduate education (58,1%) and reported a household income between two and ten times the minimum wage (64,8%).

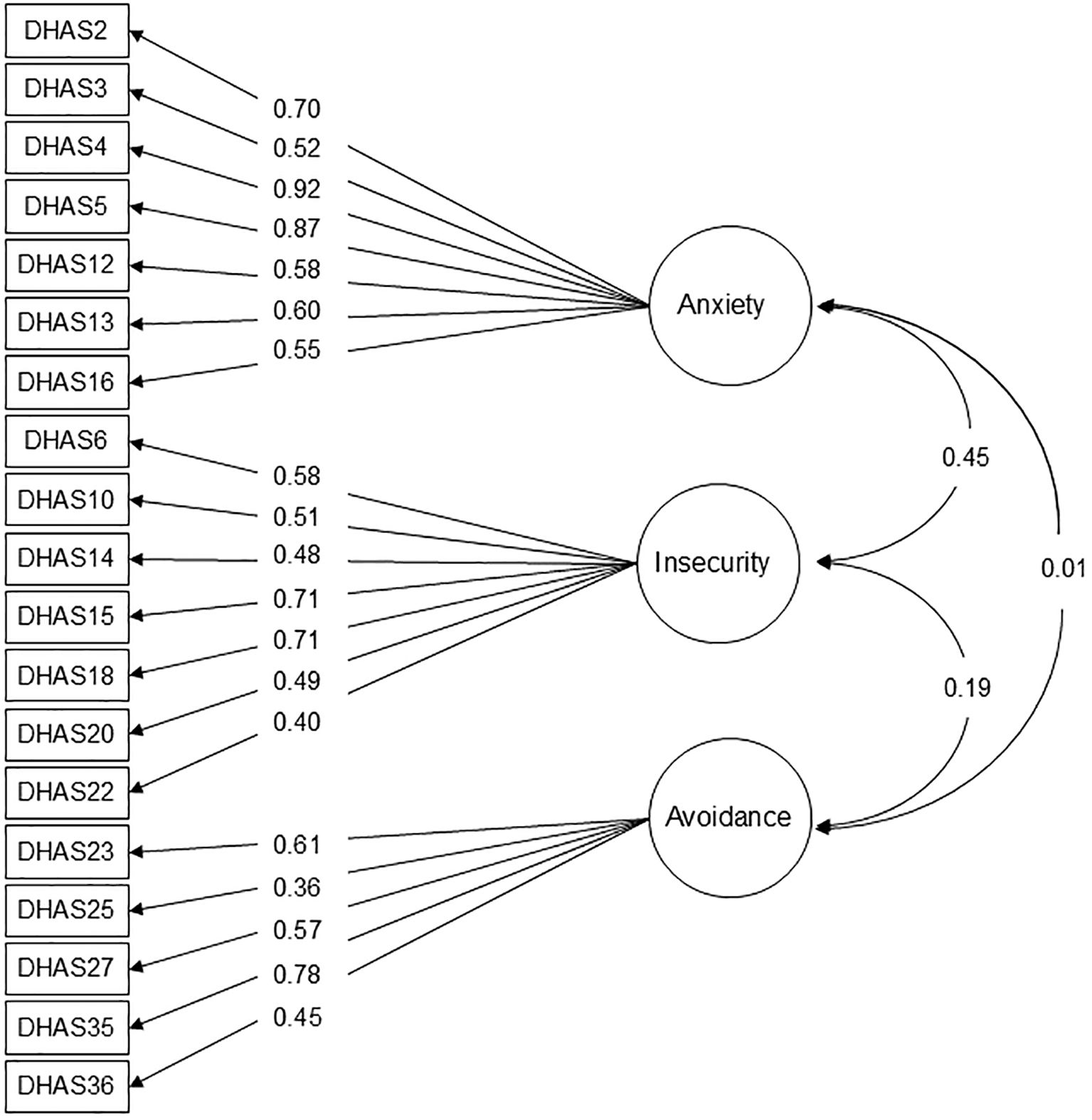

In the CFA, one item from the Insecurity dimension (DHAS 26) showed inadequate factor loading (λ < 0,30) and was therefore removed. After this adjustment, all remaining items loaded adequately on their respective factors (See Figure 1). The DHAS exhibited acceptable model fit in the CFA following item removal, χ²(149) = 501,10, p < 0,001; RMSEA = 0,08 (90% CI [0,08–0,09]); CFI = 0,94; TLI = 0,93; SRMR = 0,09.

Figure 1. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model of the dog–human attachment scale (DHAS). All factor loadings presented in the figure were statistically significant. The covariances between Anxiety and Insecurity as well as between Insecurity and Avoidance were also statistically significant.

Reliability coefficients were acceptable, with ordinal ω = 0,85 for Anxiety, 0,74 for Insecurity, and 0,69 for Avoidance; and CC = 0,86 for Anxiety, 0,76 for Insecurity, and 0,70 for Avoidance.

3.5 Initial evidence of measure invariance

Differential item functioning (DIF) analyses indicated no statistically significant evidence of item-level bias across guardian gender groups after correction for multiple testing. Both uniform and non-uniform DIF effects were non-significant for all items, suggesting comparable item functioning across groups within the limits of the sample.

3.6 Latent profile analysis

The sample’s mean factor scores for the DHAS dimensions were as follows: Anxiety (M = 11,71, SD = 6,89), Insecurity (M = 14,04, SD = 7,10), and Avoidance (M = 8,94, SD = 3,82). Observed scores ranged from 0 to 35 for Anxiety, 0 to 32 for Insecurity, and 0 to 23 for Avoidance. The maximum possible scores on the scale are 35 for Anxiety, 40 for Insecurity, and 25 for Avoidance. The quartile distribution was as follows: for Anxiety, Q1 = 7, Q2 = 11, and Q3 = 16; for Insecurity, Q1 = 9, Q2 = 14, and Q3 = 19; and for Avoidance, Q1 = 7, Q2 = 10, and Q3 = 12.

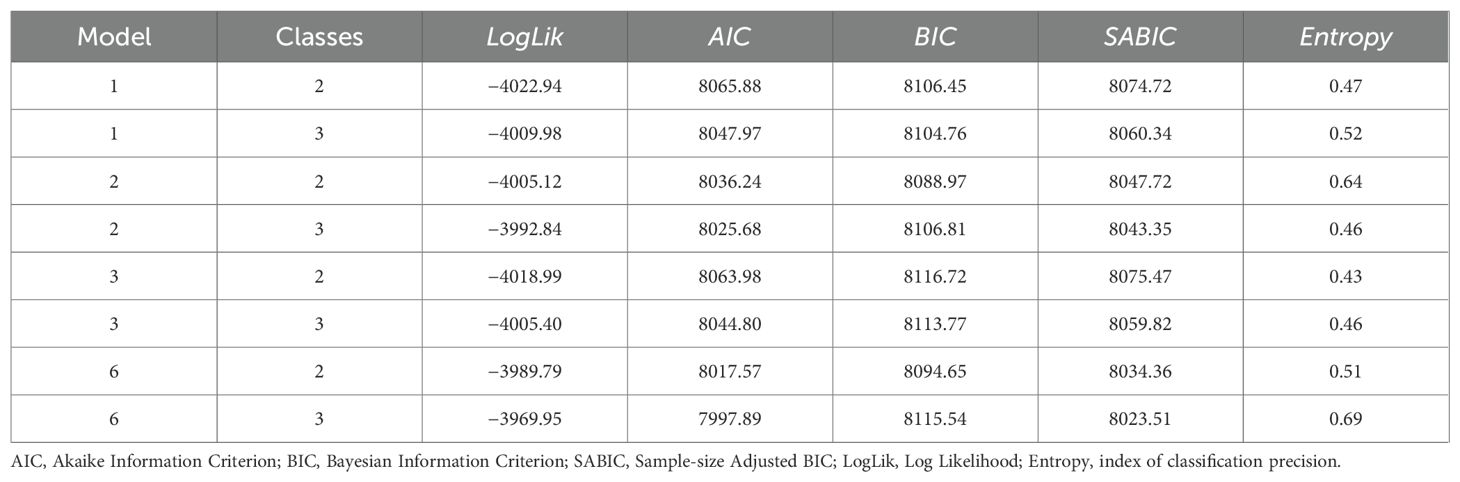

LPA models with up to four latent classes were estimated. However, it was observed that beyond three classes, there was no substantial improvement in model fit indices. Additionally, models with more than three classes presented very small class sizes, suggesting potential overfitting. The Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) was significant up to the three-class solution, indicating a real statistical gain, but became non-significant thereafter. Fit indices and quality indicators for the three-class solution are presented in Table 2. The three-class model with freely estimated variances and covariances (Model 6) was retained, as it presented the best values for AIC and SABIC, as well as adequate class separation (acceptable entropy and good minimum classification probability) and satisfactory class sizes.

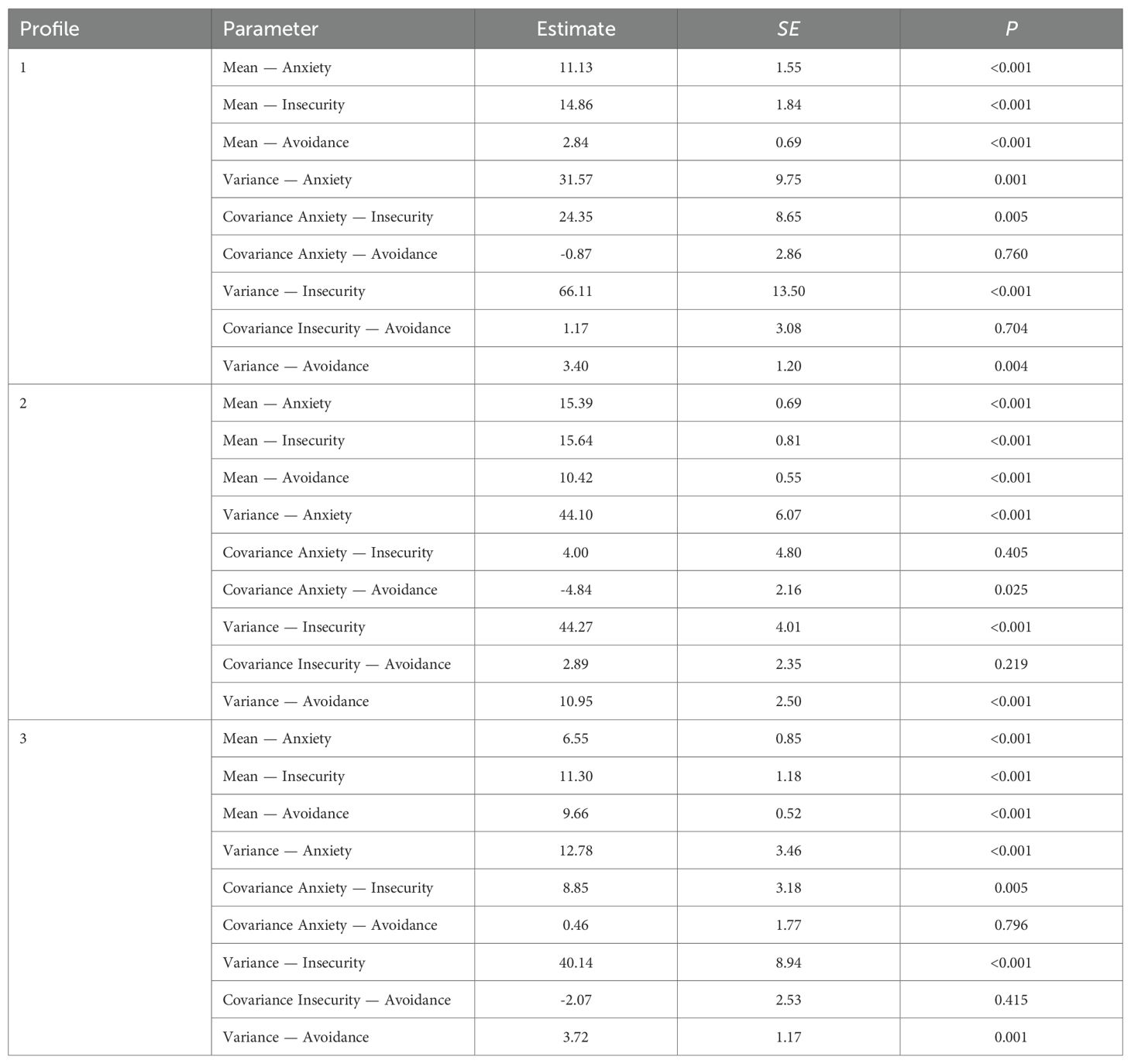

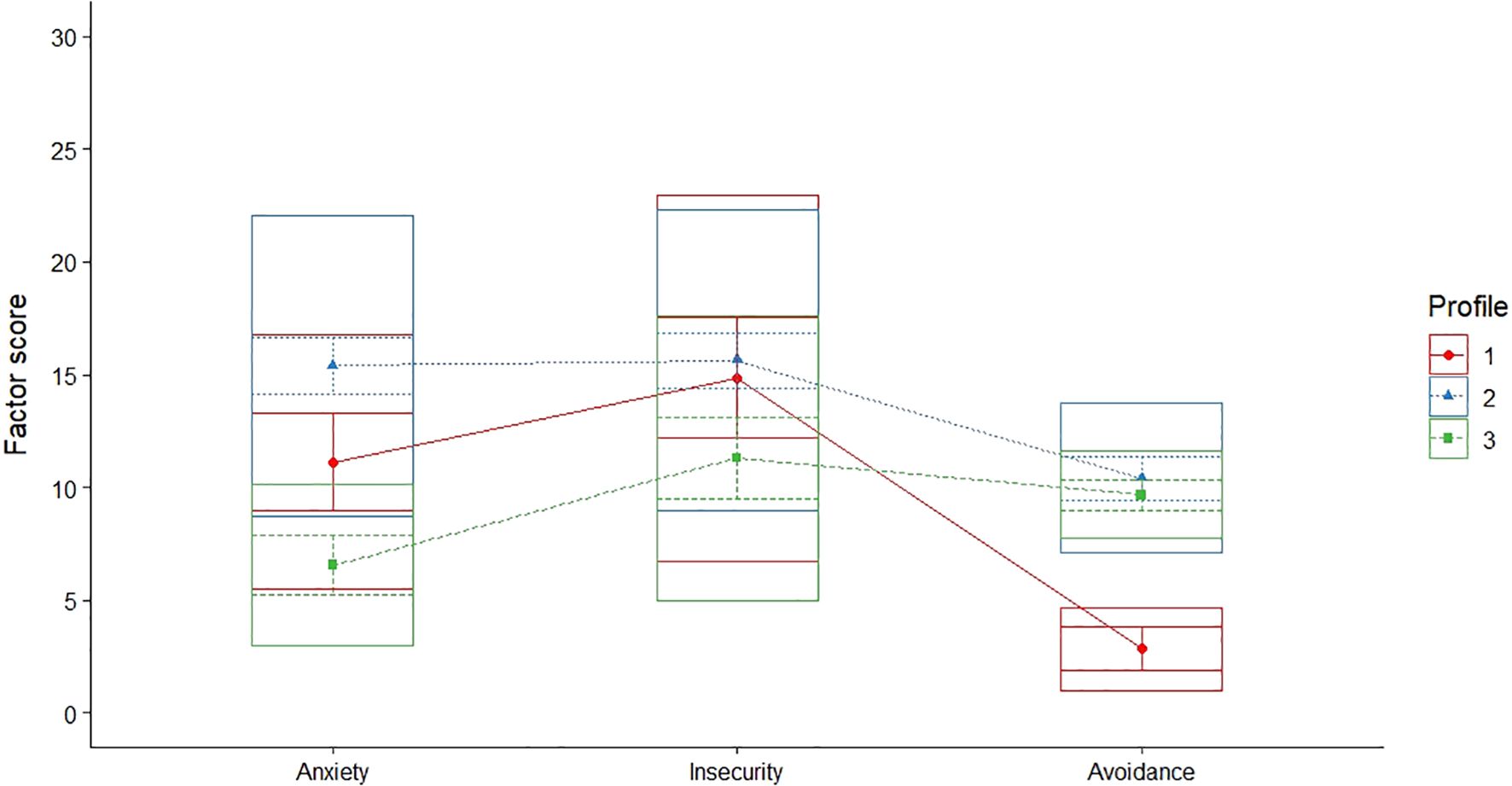

In the retained model (Figure 2), Profile 1 was characterized by moderate to high levels of anxiety and insecurity alongside consistent low levels of avoidance, corresponding to an insecure–anxious attachment pattern. Profile 2 exhibited moderate to high levels across all three dimensions, with greater dispersion in anxiety and insecurity scores, configuring a disorganized attachment pattern. In Profile 3, anxiety scores ranged from low to moderate values, insecurity from moderate to high, and avoidance from moderate to high with comparative lower dispersion; this configuration was interpreted as insecure–avoidant attachment pattern.

Figure 2. Mean scores for the three latent profiles (Profile 1, Profile 2, and Profile 3) across the dimensions of Anxiety, Insecurity, and Avoidance.

Importantly, Latent Profile Analysis is a probabilistic, data-driven approach that identifies patterns of similarity among individuals based on continuous dimensions rather than assigning deterministic or categorical classifications. Accordingly, the absence of a profile characterized by uniformly low levels across all three dimensions does not imply the absence of securely attached dogs in the sample. The identified profiles should therefore be understood as reflecting predominant configurations of attachment-related behaviors. In particular, Profile 3 may encompass individuals presenting low to moderate scores across anxiety, insecurity, and avoidance. Moreover, distancing behaviors at low to moderate levels may reflect expressions of independence or autonomy rather than avoidance per se, suggesting that some cases in the sample may approximate secure attachment patterns. Overall, 16.2% of the sample was classified in the insecure–anxious profile, 47.3% in the disorganized profile, and 36.5% in the insecure–avoidant profile. Classification quality was high, with a minimum posterior probability of class membership of 0.84.

Variance and covariance estimates further supported the correspondence between the latent profiles and the attachment patterns (see Table 3). Avoidance variance was low in both the insecure–anxious (Profile 1) and insecure–avoidant (Profile 3) profiles, indicating more consistent behavioral tendencies, expressed as low or high mean levels depending on the profile. Anxiety variance was moderate across all profiles. In contrast, insecurity showed high variance in all profiles, suggesting a broader and more heterogeneous underlying trait. The disorganized profile (Profile 2) presented the highest variances for both avoidance and anxiety, reflecting the greater behavioral inconsistency typically associated with this attachment pattern.

Covariance estimates also aligned with theoretical expectations. In the insecure–anxious profile (Profile 1), anxiety and insecurity were positively associated. In the disorganized profile (Profile 2), a significant negative covariance emerged between anxiety and avoidance, consistent with the variability and fluctuation of behavioral strategies characteristic of this style. In the insecure–avoidant profile (Profile 3), a significant positive association between insecurity and anxiety was observed, indicating that although avoidance represents the predominant strategy, insecurity and anxiety traits are also present and tend to vary together. However, the relatively low variance of avoidance in this profile may have limited the detection of a significant covariance between avoidance and insecurity, as initially expected. Notably, in this profile, avoidance was the only dimension with a moderate mean score above the sample average; insecurity showed moderate values but remained below the overall mean, and anxiety presented the lowest levels among the three dimensions.

4 Discussion

The results of this study provided evidence of content validity, internal structure, response pattern, and temporal stability for the DHAS. The items that comprised the Anxiety and Avoidance factors showed satisfactory correspondence with the dimensions traditionally proposed by attachment theory, as well as with our initial theoretical framework. A third factor emerged empirically, labeled Insecurity, composed of items that reflect the dog’s emotional instability in social, novel, or stressful situations, even in the presence of the caregiver. In other words, this factor captures the dog’s difficulty in using the caregiver as a safe haven. Although this additional dimension was not anticipated in the original development of the scale, it proved to be both empirically robust and conceptually plausible.

The dimension of attachment insecurity may be understood as an affective predisposition shaped by traumatic experiences, or by inconsistency, insensitivity, or unpredictability in interactions with caregiving figures. Our findings suggest that insecurity represents a broader emotional trait, present to varying degrees among anxious and avoidant dogs, and that it may negatively affect behavioral regulation in contexts that activate the attachment system. This interpretation is supported by the theoretical models of Fraley and Shaver (2000), who propose that insecurity can be conceptualized as a latent underlying dimension spanning both anxious and avoidant attachment styles, influencing the formation and maintenance of attachment bonds.

The tridimensional structure resembles the model proposed by the Adult Attachment Scale - AAS (Collins and Read, 1990), which combines three dimensions to derive attachment styles. As in the AAS, the tridimensional structure of the DHAS suggests that attachment may be conceptualized as a combination of multiple behavioral axes, allowing for the identification of additional nuances in attachment patterns.

The DHAS was developed based on observations of behaviors typical of the canine species and considering the interspecies context of the dog–caregiver relationship. This methodological strategy proved important, as it allowed for a more precise capture of behavioral expressions of attachment in everyday situations. In addition, it can be argued that this approach facilitated the empirical identification of a third dimension in the factorial structure of the DHAS, Insecurity. This result reinforces the relevance of a development process grounded in the behavioral specificities of dogs, avoiding the mere transposition of human theoretical categories to the animal context (Sipple et al., 2021; Topál et al., 1998; Zilcha-Mano et al., 2012).

These structural findings were accompanied by robust psychometric properties. The DHAS demonstrated strong reliability in measuring two central dimensions of attachment: anxiety, particularly related to separation, and insecurity associated with the caregiver as a safe haven. Although the avoidance dimension, which represents the secure base and is expressed through behaviors indicating distancing or independence from the caregiver, showed more modest reliability indices, they were still within acceptable limits. In this regard, it is relevant to compare our instrument to the D-AISI study (Riggio et al., 2021), which requires caregivers to interpret complex internal states in their dogs, such as concern, need for security, or emotional validation. This reliance on subjective constructs increases the degree of interpretation demanded from caregivers regarding their dog’s behavior. Such an approach may have contributed to the difficulties observed in measuring similar constructs, as reflected in the low internal consistency values reported in the original study (Riggio et al., 2021) for the “separation anxiety,” “owner as emotional support,” and “owner as a source of positive emotion” subscales.

The temporal stability of the DHAS was evaluated through the administration of the instrument at two distinct time points, with a minimum interval of 30 days. The retest results indicated adequate consistency in owners’ responses. These findings reinforce the robustness of the DHAS in capturing behavioral traits that are relatively stable over time, in line with the literature suggesting that attachment patterns, although influenced by contextual experiences, tend to exhibit a certain degree of continuity (Bowlby, 1988; Collins and Read, 1990; Fraley and Shaver, 2000).

Such stability is especially relevant for the evaluation of affective behaviors in dogs, as it allows for the distinction between situational fluctuations and more enduring characteristics in interactions with the caregiver. These results also support the scale’s utility in applied contexts, such as behavioral interventions, longitudinal monitoring, and the evaluation of changes following training or environmental modifications.

It is important to note that the model fit indices showed better performance in the EFA, indicating that the instrument is more adequately represented by a correlated factor structure that allows for the presence of cross-loadings. To some extent, this result is expected in psychological constructs; however, we emphasize that this pattern reinforces a heterogeneous perspective of attachment, in which anxiety, avoidance, and insecurity do not manifest as pure or isolated phenomena. In this sense, the scale captures the attachment construct more effectively when conceived within a more flexible structure. In this sense, some degree of cross-loadings in the model is to be expected, whereas CFA models with independent-clusters specifications may struggle to accommodate such complexity (Flora and Flake, 2017).

In the final CFA model of the DHAS, the Anxiety factor showed that items DHAS4 and DHAS5 presented the highest factor loadings. These items refer to unexpected changes in the caregiver’s routine, such as absence on unusual days (DHAS4) or changes in departure and return times (DHAS5), situations that challenge the dog’s capacity for emotional regulation and elicit anxiety-related responses. These findings are consistent with Bowlby’s attachment theory (Bowlby, 1973), which emphasizes the predictability and consistency of the attachment figure as fundamental conditions for the development of secure attachment bonds.

Within the Insecurity factor, items DHAS15 and DHAS18 stood out by presenting the highest factor loadings, capturing the dog’s tendency to react anxiously toward strangers even in the presence of the caregiver. This pattern suggests a limitation in the dog’s ability to use the caregiver as a safe haven in such contexts, a core function of the attachment bond related to comfort seeking and emotional regulation under stress (Bowlby, 1988; Topál et al., 1998).

Regarding the Avoidance factor, items DHAS23 and DHAS35 exhibited the highest factor loadings by addressing behaviors in which the dog explores new environments without seeking contact with the caregiver. This pattern is characteristic of dogs that systematically avoid interaction with the attachment figure and is commonly associated with an avoidant attachment style (Riggio et al., 2021; Topál et al., 1998).

Based on this dimensional structure, we next examined how individual differences across anxiety, insecurity, and avoidance clustered within the sample using LPA. LPA is a probabilistic model based on observed patterns among participants and proved useful for understanding how the scale differentiated individuals according to their scores on the three assessed dimensions: anxiety, insecurity, and avoidance. The results of the LPA demonstrated that these scores differentiated three latent profiles compatible with insecure-anxious, disorganized, and insecure-avoidant attachment styles, each characterized by specific combinations of anxiety, insecurity, and avoidance. Importantly, this interpretation is grounded in a dimensional understanding of attachment, in which profiles should not be construed as fixed or categorical classifications. Rather, this approach contributes to the applicability of dimensional frameworks to the assessment of interspecies attachment.

Taken together, our findings align with well-established theoretical developments in the field of human attachment, where attachment patterns are widely understood as continuous variations along underlying dimensions rather than as fixed and mutually exclusive categories (Brennan et al., 1998; Fraley and Shaver, 2000).

Within this dimensional framework, it is important to emphasize that the absence of a distinct secure profile in the LPA solution does not preclude the presence of individuals with relatively low levels across all three dimensions in our sample. Instead, such cases may be embedded within the identified profiles, particularly those characterized by lower anxiety and insecurity, such as Profile 3, reinforcing the interpretation of LPA as a method that captures predominant patterns rather than rigid categories.

In addition to the profile structure identified through LPA, it is important to consider the overall levels of anxiety, insecurity, and avoidance observed in the sample. Descriptive analyses indicated generally higher levels of anxiety and insecurity, suggesting that these dimensions were more salient across the sample as a whole. Both the general levels of these dimensions and the latent profiles identified may be influenced, at least in part, by the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

The present sample was predominantly composed of female guardians living in urban contexts, with relatively high educational levels, a high proportion of single individuals, and a large number of participants without children. This sociodemographic profile reflects a recurrent pattern in Brazilian research involving the development and validation of instruments assessing dog behavior and dog–human relationships. For example, validation studies of relationship- and affect-related instruments in Brazil, such as the Brazilian Portuguese versions of the Dog–Owner Relationship Scale (DORS; Cabral et al., 2023) and the Monash Dog Owner Relationship Scale (MDORS; Soares et al., 2025), have similarly relied on samples composed predominantly of female participants. Likewise, large-scale Brazilian studies examining emotional predispositions and behavioral problems in dogs have reported comparable respondent profiles (Savalli et al., 2019; Savalli et al., 2021).

In the Brazilian validation study of the C-BARQ (Savalli et al., 2021), sociodemographic characteristics of guardians and management practices were systematically associated with attachment-related behaviors in dogs. The instrument includes the assessment of behaviors such as whining, howling, barking, restlessness, and trembling in separation contexts, which constitute central components of the factor termed Separation-Related Problems. Likewise, the C-BARQ assesses dogs’ agitation in response to divided attention from the guardian toward other people or animals, a defining feature of the Attention-Seeking Behavior factor. In addition, the instrument encompasses behaviors such as following the guardian from room to room, sitting in close physical contact, and displaying a strong preference for a specific household member, which together compose the Attachment factor.

In the study by Savalli et al. (2021), dogs belonging to women showed a significantly higher probability of obtaining elevated scores on the Separation-Related Problems factor. A similar pattern was observed for the Attention-Seeking Behavior factor. Moreover, higher scores on the Attachment factor were associated with dogs that slept indoors, reflecting management practices commonly observed in urban contexts, particularly in highly verticalized residential settings.

Finally, it is important to highlight that guardians’ socioeconomic characteristics may influence how they perceive their relationship with the dog, particularly with regard to dimensions such as interaction, perceived proximity, and perceived costs. This phenomenon has been documented in Brazilian studies using the Dog–Owner Relationship Scale (DORS) and the Monash Dog Owner Relationship Scale (MDORS). For example, guardians with higher financial resources (Soares et al., 2025), as well as those with higher educational levels (Cabral et al., 2023), have been associated with lower perceived emotional proximity to their dogs.

Although the present sample was characterized by a predominance of female guardians and relatively high educational levels, initial evidence of measurement invariance was observed with respect to guardian gender. Differential item functioning analyses indicated no statistically significant item-level bias between male and female guardians, suggesting that DHAS items functioned equivalently across these groups within the limits of the sample. This finding supports the interpretation that observed differences in attachment dimensions are unlikely to be attributable to measurement artifacts related to guardian gender, although broader sociodemographic biases remain an important limitation.

This study represents an initial step in the validation of the DHAS. Further investigation is needed to assess its psychometric properties in different cultural contexts and with more diverse samples. Most participants were women and caregivers of companion dogs, with working dogs underrepresented in the sample. Additionally, all data were obtained through owner reports, which may have introduced perceptual biases, as the owner’s own attachment to the dog may influence their perceptions of the dog’s behavior and emotional expressions (Martens et al., 2016). Despite these limitations, initial evidence of measurement invariance across guardian gender was observed, suggesting comparable item functioning between male and female caregivers within the limits of the sample.

Moreover, as with any self-report instrument, responses may be subject to social desirability bias, potentially leading owners to underreport behaviors perceived as undesirable or indicative of insecure attachments. Indeed, during scale refinement, some items with high kurtosis were removed precisely because they explicitly included expressions such as “your dog avoids you”, which may have discouraged accurate reporting; future studies should remain attentive to this issue when developing or adapting similar instruments.

5 Conclusions

The present study provided initial evidence of content validity, internal structure, response patterns, and temporal stability for the Dog–Human Attachment Scale (DHAS), demonstrating its suitability for assessing attachment in the dog–human relationship.

The dimensional structure adopted by the DHAS conceptualizes attachment as a continuum rather than fixed categories, enabling the identification of individual variation in attachment behaviors. This dimensional perspective supports a more flexible and sensitive assessment of the diversity of affective bonds, avoiding rigid classifications that may oversimplify the complexity of dog–caregiver interactions.

The emergence of a third factor, specific to dogs, illustrates the value of developing species-adapted instruments grounded in canine behavior, rather than directly transposing constructs from human models. This species-centered approach fosters meaningful advances in the comparative study of cognition and personality, allowing for the identification of latent traits that might be overlooked in non-adapted frameworks. In this regard, the DHAS represents both a methodological and conceptual advancement, aligning psychometric rigor with the particularities of canine behavior.

Altogether, these findings support the DHAS as a psychometrically robust and behaviorally sensitive instrument tailored to dogs, contributing to the scientific understanding of interspecific attachment and offering promising applications for enhancing animal welfare and caregiver–human interactions. Future studies employing stratified or population-based sampling designs will be particularly important to disentangle instrument-related characteristics from sample-specific effects.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Espírito Santo. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MS: Project administration, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Validation, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. RT: Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported by a doctoral scholarship awarded to the corresponding author by the Espírito Santo Research Support Foundation (FAPES), Grant No. 321/2022.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants in the study, as well as the Ethology Laboratory and the Graduate Program in Psychology at the Federal University of Espírito Santo. The authors also thank FAPES for its support.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors declare and assume full responsibility for the use of generative AI in the preparation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used for English language revision and for assisting in the creation of the latent profile analysis figure.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fetho.2026.1752182/full#supplementary-material

References

Ainsworth M. D. S., Blehar M. C., Waters E., and Wall S. N. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation (New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum).

Akogul S. and Erisoglu M. (2017). An approach for determining the number of clusters in a model-based cluster analysis. Entropy 19, 452. doi: 10.3390/e19090452

Ballantyne K. C. (2018). Separation, confinement, or noises. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 48, 367–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2017.12.005

Bentosela M., Cavalli C., Dzik M. V., Caliva M., and Udell M. A. R. (2024). Effects of a brief separation from the owner while in the home environment: Comparison of fearful and control dogs. Anthrozoös 37, 959–975. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2024.2389643

Borrelli C., Riggio G., Gazzano A., Carlone B., and Mariti C. (2022). Attachment style classification in the interspecific and intraspecific bond in dogs. Dog Behav. 8, 9–18. doi: 10.4454/DB.V8I1.148

Bowlby J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Volume II – Separation: Anxiety and anger (New York, NY: Basic Books).

Bowlby J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory (London, UK: Routledge).

Brennan K. A., Clark C. L., and Shaver P. R. (1998). “Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview,” in Attachment theory and close relationships. Eds. Simpson J. A. and Rholes W. S. (Guilford Press, New York, NY), 46–76.

Brenning K., Van Petegem S., Vanhalst J., and Soenens B. (2014). The psychometric qualities of a short version of the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale – Revised Child version. Pers. Individ. Differ. 68, 118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.005

Cabral F. G. S., Resende B., Mariti C., Howell T., and Savalli C. (2023). Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese dog–owner relationship scale (DORS). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 266, 106034. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2023.106034

Cimarelli G., Schindlbauer J., Pegger T., Wesian V., and Virányi Z. (2021). Secure base effect in former shelter dogs and other family dogs: Strangers do not provide security in a problem-solving task. PloS One 16, e0261790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261790

Collins N. L. and Read S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J. Pers. Soc Psychol. 58, 644–663. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644

de Souza M. C., Bastos G. Q., Gomes C. M. S., and Tokumaru R. S. (2025a). Anxiety in Brazilian dogs: Typical behaviors, anxiety-inducing situations, and sociodemographic factors. Behav. Processes 105241. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2025.105241

de Souza M. C., Bastos G. Q., and Tokumaru R. S. (2025b). Attachment theory applied to the human–dog relationship. J. Vet. Behav. 82, 8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2025.09.005

Drabinová A. and Martinková P. (2017). Detection of differential item functioning with nonlinear regression: A non-IRT approach accounting for guessing. J. Educ. Measurement 54, 498–517. doi: 10.1111/jedm.12158

Ferrando P. J. and Lorenzo-Seva U. (2017). FACTOR (Version 12.06.08) [Computer software] (Tarragona: Universitat Rovira i Virgili). Available online at: http://psico.fcep.urv.es/utilitats/factor/ (Accessed January 29, 2026).

Flora D. B. and Flake J. K. (2017). The purpose and practice of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in psychological research: Decisions for scale development and validation. Can. J. Behav. Science/Revue Can. Des. Sci. du comportement 49, 78–88. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000069

Fraley R. C. and Shaver P. R. (2000). Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 4, 132–154. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.4.2.132

Gácsi M., Maros K., Sernkvist S., Faragó T., and Miklósi Á. (2013). Human analogue safe haven effect of the owner: Behavioural and heart rate response to stressful social stimuli in dogs. PloS One 8, e58475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058475

Hladká A. and Martinková P. (2020). difNLR: Generalized logistic regression models for DIF and DDF detection. R J. 12, 300–323. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2020-014

Hladká A., Martinková P., and Brabec M. (2025). New iterative algorithms for estimation of item functioning. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 51(1), 175–205. doi: 10.3102/10769986241312354

Hoyle R. H. and Gottfredson N. C. (2023). “Structural equation modeling with latent variables,” in APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Washington, DC: American Psychological. 2nd, vol. 2. , 459–490. doi: 10.1037/0000319-021

jamovi (2024). jamovi (Version 2.7) [Computer software] (Sydney: jamovi). Available online at: https://www.jamovi.org.

JASP Team (2024). JASP (Version 0.95.4) [Computer software] (Amsterdam: JASP). Available online at: https://jasp-stats.org/ (Accessed January 29, 2026).

Kalkbrenner M. T. (2024). Choosing between Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, McDonald’s coefficient omega, and coefficient H: Confidence intervals and the advantages and drawbacks of interpretive guidelines. Measurement Eval. Couns. Dev. 57(2), 93–105. doi: 10.1080/07481756.2023.2283637

Konok V., Kosztolányi A., Rainer W., Mutschler B., Halsband U., and Miklósi Á. (2015). Influence of owners’ attachment style and personality on their dogs’ separation-related disorder. PloS One 10, e0118375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118375

Konok V., Marx A., and Faragó T. (2019). Attachment styles in dogs and their relationship with separation-related disorder – A questionnaire based clustering. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 213, 81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2019.02.014

Lorenzo-Seva U. and Ferrando P. J. (2019). Robust Promin: un método para la rotación de factores de diagonal ponderada. Liberabit 25, 99–106. doi: 10.24265/liberabit.2019.v25n1.08

Lorenzo-Seva U. and Ferrando P. J. (2023). A simulation-based scaled test statistic for assessing model-data fit in least-squares unrestricted factor-analysis solutions. Methodology 19, 96–115. doi: 10.5964/meth.9839

Main M. and Solomon J. (1986). “Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern,” in Affective development in infancy. Eds. Brazelton T. B. and Yogman M. W. (Ablex, Norwood, NJ), 95–124.

Mariti C., Ricci E., Carlone B., Moore J. L., Sighieri C., and Gazzano A. (2013). Dog attachment to man: A comparison between pet and working dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 8, 135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2012.05.006

Martens P., Enders-Slegers M. J., and Walker J. K. (2016). The emotional lives of companion animals: Attachment and subjective claims by owners of cats and dogs. Anthrozoös 29, 73–88. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2015.1075299

Nagasawa M., Mogi K., and Kikusui T. (2009). Attachment between humans and dogs. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 51, 209–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5884.2009.00402.x

Ogata N. (2016). Separation anxiety in dogs: What progress has been made in our understanding of the most common behavioral problems in dogs? J. Vet. Behav. 16, 28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2016.02.005

Palmer R. and Custance D. (2008). A counterbalanced version of Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Procedure reveals secure-base effects in dog–human relationships. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 109, 306–319. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2007.04.002

Parthasarathy V. and Crowell-Davis S. L. (2006). Relationship between attachment to owners and separation anxiety in pet dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 1, 109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2006.09.005

Prato-Previde E., Custance D. M., Spiezio C., and Sabatini F. (2003). Is the dog-human relationship an attachment bond? An observational study using Ainsworth’s strange situation. Behav. 140, 225–254. doi: 10.1163/156853903321671514

R Core Team (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 4.4.2) [Computer software] (Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed January 29, 2026).

Riggio G. (2020). A mini review on the dog-owner attachment bond and its implications in veterinary clinical ethology. Dog Behav. 6, 17–26. doi: 10.4454/DB.V6I3.125

Riggio G., Noom M., Gazzano A., and Mariti C. (2021). Development of the dog attachment insecurity screening inventory (D-AISI): A pilot study on female owners. Animals 11, 3381. doi: 10.3390/ani11123381

Savalli C., Albuquerque N., Vasconcellos A. S., Ramos D., de Mello F. T., Mills D. S., et al. (2019). Assessment of emotional predisposition in dogs using PANAS (Positive and Negative Activation Scale) and associated relationships in a sample of dogs from Brazil. Scientific Reports 9, 18386. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54645-6

Savalli C., Albuquerque N., Vasconcellos A. S., Ramos D., de Mello F. T., and Serpell J. A. (2021). Characteristics associated with behavior problems in Brazilian dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 234, 105213. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2020.105213

Savalli C. and Mariti C. (2020). Would the dog be a person’s child or best friend? Revisiting the dog–tutor attachment. Front. Psychol. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.576713

Sipple N., Thielke L., Smith A., Vitale K. R., and Udell M. A. R. (2021). Intraspecific and interspecific attachment between cohabitant dogs and human caregivers. Integr. Comp. Biol. 61, 132–139. doi: 10.1093/icb/icab054

Soares P. H. A., Prata J. C., de Faria A. T., Silveira C. G., Assis I. T., de Castro L. C., et al. (2025). Validation of the Monash dog owner relationship scale (MDORS) for Brazilian Portuguese and factors influencing dog–owner relationships. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 286, 106621. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2025.106621

Solomon J., Beetz A., Schöberl I., Gee N., and Kotrschal K. (2019). Attachment security in companion dogs: Adaptation of Ainsworth’s strange situation. Attach. Hum. Dev. 21, 389–417. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2018.1517812

Spruit A., Wissink I., Noom M. J., Colonnesi C., Polderman N., Willems L., et al. (2018). Internal structure and reliability of the Attachment Insecurity Screening Inventory (AISI) for children aged 6–12. BMC Psychiatry 18, 30. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1608-z

Timmerman M. E. and Lorenzo-Seva U. (2011). Dimensionality assessment of ordered polytomous items with parallel analysis. Psychol. Methods 16, 209–220. doi: 10.1037/a0023353

Topál J., Miklósi Á., Csányi V., and Dóka A. (1998). Attachment behavior in dogs: A new application of Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Test. J. Comp. Psychol. 112, 219–229. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.112.3.219

Valentini F. and Damásio B. F. (2016). Variância média extraída e confiabilidade composta: Indicadores de precisão. Psicol. Teor. Pesqui. 32, e322225. doi: 10.1590/0102-3772e322225

Völter C. J., Starić D., and Huber L. (2023). Using machine learning to track dogs’ exploratory behaviour with or without their caregiver. Anim. Behav. 197, 97–111. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2023.01.004

Waters E. and Deane K. E. (1985). Defining and assessing individual differences in attachment relationships. Monogr. Soc Res. Child Dev. 50, 41. doi: 10.2307/3333826

Williams G. A. and Kibowski F. (2016). “Latent class analysis and latent profile analysis,” in Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. Eds. Jason L. A. and Glenwick D. S. (Oxford University Press, Oxford), 143–151.

Wissink I. B., Colonnesi C., Stams G. J. J. M., Hoeve M., Asscher J. J., Noom M. J., et al. (2016). Validity and reliability of the Attachment Insecurity Screening Inventory (AISI) 2–5 years. Child Indic. Res. 9, 533–550. doi: 10.1007/s12187-015-9322-6

Yang Q., Zhao A., Lee C., Wang X., Vorderstrasse A., and Wolever R. Q. (2022). Latent profile/class analysis identifying differentiated intervention effects. Nurs. Res. 71, 394–403. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000597

Yu C. Y. and Muthén B. (2002). Evaluation of model fit indices for latent variable models with categorical and continuous outcomes. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA.

Zilcha-Mano S., Mikulincer M., and Shaver P. R. (2011). An attachment perspective on human–pet relationships: Conceptualization and assessment of pet attachment orientations. J. Res. Pers. 45, 345–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2011.04.001

Keywords: attachment, attachment styles, canine behavior, human–animal interaction, psychometrics

Citation: de Souza MC and Tokumaru RS (2026) Development and validity evidence of the dog–human attachment scale. Front. Ethol. 5:1752182. doi: 10.3389/fetho.2026.1752182

Received: 22 November 2025; Accepted: 19 January 2026; Revised: 05 January 2026;

Published: 06 February 2026.

Edited by:

Cristiane Gonçalves Titto, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Timothy P. Johnson, University of Illinois Chicago, United StatesPaulo Henrique Araújo Soares, Ciência e Tecnologia do Norte de Minas Gerais (IFNMG), Brazil

Copyright © 2026 de Souza and Tokumaru. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Cecília de Souza, bWFjZWNpbGlhc291emE4M0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Maria Cecília de Souza

Maria Cecília de Souza Rosana Suemi Tokumaru2

Rosana Suemi Tokumaru2