- 1 School of Geosciences and Civil Engineering, College of Science and Engineering, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan

- 2 Graduate School of Engineering Science, Akita University, Akita, Japan

- 3 Department of Mathematical Science and Electrical-Electronic-Computer Engineering, Akita University, Akita, Japan

- 4 Research Institute of Geology and Geoinformation, Geological Survey of Japan, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), Tsukuba, Japan

- 5 Volcanoes and Earth’s Interior Research Center, Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), Kanagawa, Japan

Amphibole plays a pivotal role in mediating the flux of volatiles and partial melting that ultimately contribute to arc magmatism. The influence of amphibole from the lower crust to the upper mantle remains unclear due to limited opportunities for observation. Amphibole-rich ultramafic rock characterized by large poikilitic hornblende grains with olivine and pyroxenes occurs in the Nishidohira metamorphic rocks in the southern Abukuma Mountains of Northeast Japan (we call poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite hereafter). Amphibole exhibit zoning in color and chemical composition: the dark core has higher TiO2 and Al2O3 contents than the light green rims. Dark-colored high-TiO2 pargasitic amphibole formed early from magmatic melts. Melt compositions calculated from the dark-colored amphibole core based on melt-mineral partitioning indicate that the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite resulted from adakitic magmatic activity. Reactions between pre-existing ultramafic rock and adakitic melt are likely to form poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite when the melt/rock ratio is low, and hornblende gabbro when the ratio is high. The U-Pb zircon age of approximately 120 Ma for poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and associated hornblende gabbro is interpreted as a magmatic age. In the Early Cretaceous tectonic framework of Northeast Japan, adakitic magmatism is attributed to the westward subduction of the Izanagi (or Kula) plate beneath the eastern margin of the Eurasian Plate.

1 Introduction

Amphiboles act as volatiles storage and play a key role in magma differentiation under conditions from the upper mantle to the lower crust (e.g., Davidson et al., 2007; Collins et al., 2020). Fractionation of amphibole significantly affects the evolution of arc magmas (Hidalgo and Rooney, 2010; Kratzmann et al., 2010), eventually leaving amphibole-rich mafic/ultramafic rocks in the lower crust to the uppermost mantle as cumulates or residues. Ultramafic rocks that contain poikilitic hornblende (poikilitic hornblende UMR hereafter), which is characterized by large poikilitic amphibole (typically hornblende in composition) grains enclosing rounded olivine with clinopyroxene/orthopyroxene, is classically referred to as cortlandite (Williams, 1886). Poikilitic hornblende UMR is a minor but often occurring as a component in granitic and metamorphic belts of variable ages (e.g., Tiepolo et al., 2011; Itano et al., 2021) and in the lower crust to upper mantle sequence of supra-subduction ophiolites (Ishiwatari, 1985; Ozawa et al., 2015). Poikilitic hornblende UMR is also found as a sub-arc xenolith (Ishimaru et al., 2009).

Poikilitic hornblende UMR (often refereed as cortlandite) has been reported from several geological units in Japan, such as the Ryoke Belt (Yoshimura et al., 1940; Yagi, 1944; Noto, 1977; Ogiso, 1984; Tanaka et al., 1987; Yamasaki et al., 2012), and the Hida Belt (Itano et al., 2021). Yamasaki et al. (2012) pointed out that examining the crystallization sequence in the poikitic hornblende UMRs, particularly distinguishing between cumulus phases and intercumulus phases, is crucial for understanding the composition of the melt involved in their formation. Yamasaki et al. (2012) also pointed out that the crystallization sequence and chemical trends of minerals in the poikilitic hornblende UMRs from the Ryoke belt are consistent with those expected from island arc magmas. Itano et al. (2021) suggested that the trace element composition of melt calculated from amphibole in the poikilitic hornblende UMRs from the Hida Belt is similar to the average composition of continental arc basalts. Clinopyroxene occurs as a relatively early crystallization phase in one of the Ryoke UMRs (Yamasaki et al., 2012), whereas poikilitic orthopyroxene is observed with poikilitic hornblende in the Hida UMRs (Itano et al., 2021). Poikilitic hornblende UMR exhibits diversity in mineralogy and geochemistry. Further study on UMR is necessary to elucidate the petrogenesis and melt compositions associated with the UMR formation.

Poikilitic hornblende UMR occurs in the Abukuma Metamorphic Belt in the Tohoku region of Japan (Tagiri, 1971; Shimaoka and Watanabe, 1976; Tanaka et al., 1982). In this region, amphibole-rich gabbros are also exposed, providing an excellent opportunity to comprehensively investigate magma evolution involving amphibole. We report petrology, mineral chemistry, and U-Pb dating of zircon of poikilitic hornblende UMR, including associated hornblende gabbro in the Nishidohira metamorphic rocks. As discussed in this paper, the interaction of adakitic melts with ultramafic rocks provides an effective mechanism for the metasomatic introduction of amphibole-forming components. Interestingly, some of the Cretaceous granitic intrusions in the adjacent Kitakami Mountains are characterized by adakitic compositions (Tsuchiya et al., 2005; 2007). Therefore, the Nishidohira poikilitic hornblende UMR provides crucial insights into the relationship between its formation and adakitic magmatic activity, as well as for elucidating the geodynamic history of the study area.

2 Geological background and sample description

The Abukuma Mountains of northeastern Japan are bordered by the Tanakura Tectonic Line to the northeast and the Futaba Fault to the southwest (Figure 1). The Abukuma Metamorphic Belt is widely distributed in the northern part of the southern Abukuma Mountains (Miyashiro, 1961). In this study, we classify the metamorphic rocks in the Hitachi area of the southern Abukuma Mountains into the Nishidohira metamorphic rock, Tamadare metamorphic rock and Hitachi metamorphic rock group (Akazawa, Daioin, and Ayukawa Formations) based on their metamorphic conditions, protoliths and structure (Tagiri, 1971; Shimaoka et al., 1988; Tagiri et al., 2010; 2011; Kanamitsu et al., 2011) (Figure 1). The Irishiken granodiorite body is located north of the Tamadare metamorphic rock and Hitachi metamorphic rock group.

Figure 1. Geological framework of the studied area. (A) Basement geological map of the Northeast Japan showing North Kitakami (NK), South Kitakami (SK) and Abukuma (Abu) (simplified after Wallis et al., 2020). Geological units are Id, Idonnappu; Jo, Joetsu; MT, Mno-Tanba-Ashio; Nd, Nedamo; Nm, Nemuro; RK, Rebun-Kabato; Sy, Sorachi-Yezo; Tk, Tokoro. Major faults are TTL, Tanakura; MTL, Median; ISTL, Itoigawa-Shizuoka; BLT, Butsuzo and TL, Tectonic Line. (B) Geological map of the Southern Abukuma Mountains, simplified after Tagiri et al. (2016). The star indicates the Nishidohira ultramafic-mafic body (This study). Sample locality of granitic rock of the Irishiken Granodiorite body is shown as a solid circle (IRS01). F, formation.

The Hitachi metamorphic rocks consist mainly of low-metamorphic grade of metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks (Tagiri, 1971). Serpentinite is present at the boundary between the Nishidohira and the Akazawa Formation of the Hitachi metamorphic rock (Shimaoka and Watanabe, 1976; Hiroi and Kobayashi, 1996; Tagiri et al., 2010; Yoneguchi et al., 2021). The Tamadare metamorphic rocks are mainly plutonic rock origin metamorphosed under amphibolite facies conditions (Shimaoka et al., 1988). U-Pb zircon ages of 506.7 ± 3.4 Ma were reported from amphibole gneiss and is interpreted as a protolith age (Tagiri et al., 2011).

The Nishidohira metamorphic rocks are located at the southwestern margin of the Hitachi area. Structural studies suggest that the Hitachi metamorphic rocks were thrust onto the Nishidohira metamorphic rocks (Watanabe and Bikerman, 1971; Faure et al., 1986). Andalusite-kyanite-sillimanite-bearing gneisses (AKS gneiss) occur in the Nishidohira metamorphic rocks (Hiroi and Kobayashi, 1996). Yoneguchi et al. (2021) revisited the P-T-Time pathway of AKS gneisses in the Nishidohira metamorphic rocks. Metamorphic grade is from lower to upper amphibolite-facies (Hiroi and Kobayashi, 1996).

Poikilitic hornblende UMR body including hornblende gabbro is in contact with the Nishidohira metamorphic rocks in the east and north, but no clear contact metamorphism is observed (Tanaka et al., 1982). Leucocratic veins, usually a few centimeters thickness, cut the poikilitic hornblende UMR body. Hiroi and Kobayashi (1995) reported staurolite-bearing pelitic metamorphosed xenolith in the poikilitic hornblende UMR body.

The study samples were collected from locations reasonably distant from the surrounding metamorphic rocks and not associated with leucocratic veins to avoid mineralogical and geochemical modifications from these rocks. The Nishidohira poikilitic hornblende UMR consists mainly of large poikilitic hornblende with rounded olivine and subhedral clinopyroxene, with small amounts of biotite, orthopyroxene, and ilmenite (Figure 2). Amphibole shows color zoning from a dark core through a brown rim to a green rim (Figure 3). Abundant ilmenites are present in the dark core (Figure 3E). Green-colored amphibole and clinopyroxene often form a vermicular texture (Figure 3A). Orthopyroxene occurs around olivine or as discrete grains in domains dominated by green-colored amphibole (Figures 2,3). Zircon is confirmed at the grain boundary of the main phases at the intersection. Mineral mode was measured using ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012) from X-ray intensity maps of multiple elements (Figures 2,4). The analytical method for X-ray intensities of multiple elements will be described in Supplementary Material. Olivine accounts for approximately 5% by volume (here, olivine + pyroxenes + amphibole = 100%), pyroxenes account for approximately 50% (of which orthopyroxene is 2%–3%), and amphibole accounts for approximately 45%. The Nisidohira poikilitic hornblende UMR corresponds to hornblende pyroxenite. Hereafter, this is referred to as poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite.

Figure 2. Thin section image of poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite. Plane-polarized and cross-polarized image noting distribution of dark-colored hornblende, Combined X-ray intensity map for Ti (Purple), Ca (Yellow) and Fe (Red) and X-ray intensity map for Ti only (Blue). Amph, amphibole; Cpx, clinopyroxene; Ol, olivine; Opx, orthopyroxene. Orange-colored O, Orthopyroxene. The two panels on the right show X-ray intensity maps of titanium (Ti). Olivine (Ol) is present in high-Ti amphibole, while orthopyroxene (denoted by orange-colored O) is present in low-Ti amphibole.

Figure 3. Photomicrograph of poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite (Sample NSD06) showing distinct color zoning from dark, dark brown to light green in amphibole around clinopyroxene (Cpx) and olivine (Ol) ± orthopyroxene (Opx) (A–D). Plane-polarized (A,C) and corss-polarized (B,D). Back-scattered electron image of dark-colored amphibole. Ilmenites (white phase) are abundantly present in the host amphibolie (gray, entire field of view) (E).

Figure 4. Thin section image of hornblende gabbro (Sample NSD05) (A–D). Plane-polarized (A) and cross-polarized images (B), combined X-ray intensity map for Ti, Ca and Fe allowing mineral phase distribution of hornblende (orange), plagioclase (Green), biotite (Purple) and others (C), and X-ray intensity map for P (light blue) (D) and S (purple) (E). The scale bar in (E) is the same as in A–D. Photomicrograph of hornblende gabbro (Sample NSD05). Plane-polarized (F) and cross-polarized images (G).

Hornblende-biotite gabbro (Hornblende gabbro hereafter) is composed mainly of medium grains of hornblende (<3 mm), biotite (<2 mm) and plagioclase (<3 mm), with small amounts of fine grains of ilmenite, sulfide, apatite and zircon (Figure 4). Using the same method as for the ultramafic rock, mineral modes were measured from X-ray intensity maps of multiple elements. The mineral mode by volume % is as follows: amphibole 74%, plagioclase 10%, biotite 8%, apatite 3%, titanite 2%, sulfide <3%, and zircon <1%.

Granitic rock from the western part of the Irishiken granodiorite body was also sampled (IRS01 in Figure 1), and the U-Pb zircon dating results were compared with the previous data.

3 Mineral chemistry

The analytical methods for X-ray intensity mapping of the sample surface, the major and trace element compositions of minerals, and U-Pb dating of zircon are described in the Supplement. Major and trace element compositions of olivine, clinopyroxene, orthopyroxene, amphibole, plagioclase and biotite in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and hornblende gabbro are presented in Supplementary Material (Supplementary Tables S1–S7).

3.1 Mineral chemistry of poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite

The forsterite content [100 Mg/(Mg + Fe) atomic ratio] of olivine has a range of 65–76 for both NSD04 and NSD06. The core of coarse-grained olivine tends to have a high forsterite content, while the rim and smaller grains usually have a lower Fo content. The MnO content of olivine is 0.2–0.7 wt. % (Supplementary Figure S1). The NiO content of olivine is below the detection limit of the SEM-EDS analysis (<0.5 wt. %).

XMg [Mg/(Mg + Fe) atomic ratio] of clinopyroxene is mostly 0.8–0.85 (Figure 5). The Al2O3 and TiO2 contents of large clinopyroxene are 2-5 wt. % (Al = 0.1–0.2 per formula unit when O = 6) and 0.4–0.8 wt. % (Ti = 0.01–0.03 per formula unit), respectively. Clinopyroxene, which shows a vermicular texture with amphibole, is generally lower in Al2O3 (<2 wt. %, Al < 0.1) and TiO2 (<0.6 wt. %, Ti < 0.01) (Figure 5). The chondrite-normalized REE pattern of large clinopyroxene grains was gently convex with high Sm-Nd and a slight negative Eu anomaly (Supplementary Figure S2). Primitive mantle-normalized trace element patterns of large clinopyroxene exhibit negative anomalies of Nb, Zr and Ti (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 5. Plot of Al (per formula unit O = 6) versus Mg/(Mg + Fe). (A) and Ti (per formula unit O = 6). (B) for clinopyroxene from the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite (NSD4 and NSD06). Amph + Cpx, vermicular aggregate of amphibole and clinopyroxene.

XMg of orthopyroxene is 0.72–0.74. The Al2O3 and CaO contents of orthopyroxene are 1.4–2.5 wt. % and 0.6–0.8 wt. %, respectively. The chondrite-normalized REE pattern of orthopyroxene is gently U-shaped (Supplementary Figure S2). The primitive mantle-normalized trace element pattern exhibits a positive anomaly for Ti (Supplementary Figure S2).

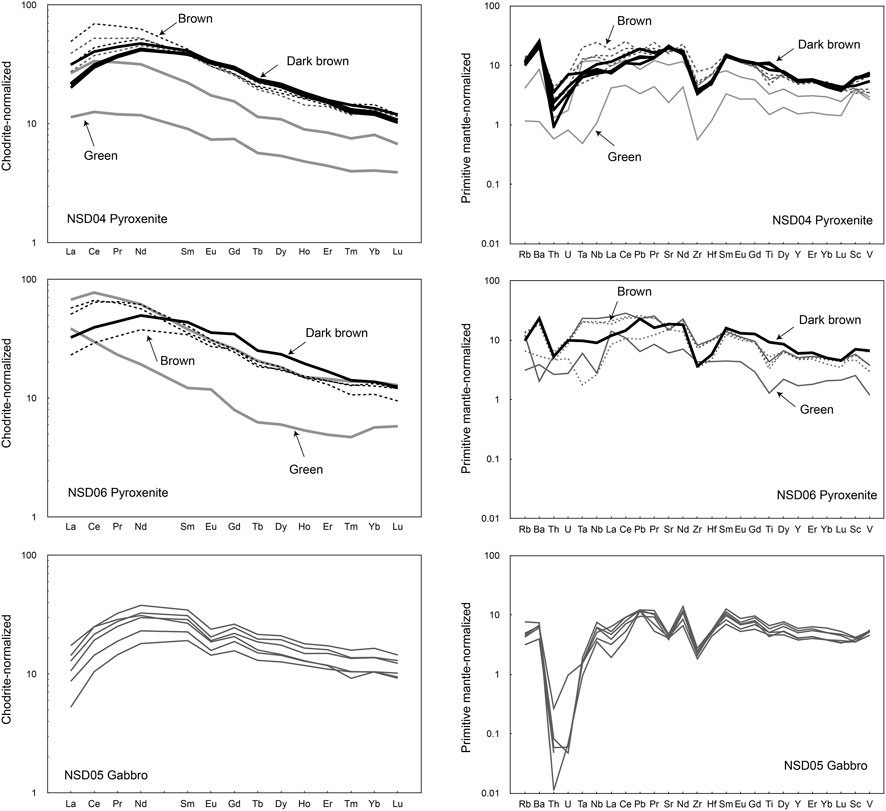

Following the nomenclature of Hawthorne et al. (2012), the dark core and brown-colored margin of poikilitic amphibole is pargasite and magnesiohornblende, while green-colored rim of poikilitic amphibole and vermicular amphibole with clinopyroxene are pargasite, magnesiohornblende and actinolite in composition (Supplementary Figure S3). Dark-colored to brown amphiboles exhibit high TiO2 content (1.3–2.1 wt. %; Ti = 0.2–0.3 when O = 23)., whereas vermicular and green-colored amphiboles contain low amounts (<1 wt. %) (Ti < 0.2 when O = 23) (Figure 6). The XMg (Mg/(Mg + Fe2+) atomic ratio) of amphibole varies between 0.72 and 0.89. Chondrite-normalized REE patterns in the dark-colored core and brown intermediate zone of poikilitic amphibole are convex with high Sm-Nd (Figure 7). Brown-colored intermediate zone has slightly higher LREEs than the dark-colored core. The chondrite-normalized REE pattern of green-colored amphibole generally shows an upward leftward pattern (Figure 7). Primitive mantle-normalized trace element patterns of dark and brown hornblende exhibit negative anomalies of high-field strength elements (HFSEs) such as Th, Zr, and Hf, and high in large ion lithophile elements (LILEs) such as Rb, Ba, and Sr (Figure 7). The absolute amount of REEs and trace elements of green-colored amphibole is lower than those of other amphiboles.

Figure 6. Plot of Ti (apfu: atom per formula unit, O = 23) versus Na + K (apfu: atom per formula unit, O = 23) for amphiboles from the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite (A: NSD 04; B: NSD06) and from hornblende gabbro (C: NSD05). Amph - Cpx, vermicular aggregate of amphibole and clinopyroxene.

Figure 7. Chondrite-normalized rare earth element patterns (left) and primitive mantle-normalized trace element patterns (right) of amphibole from the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite (NSD04 and NSD06) and hornblende gabbro (NSD05).

The XMg and the TiO2 content of biotite is 0.73–0.77 and 1.2–1.9 wt. %, respectively.

3.2 Mineral chemistry of hornblende gabbro

Amphibole is pargasitic to magnesiohornblende in composition (Supplementary Figure S3; Supplementary Table S6). The TiO2 content of amphibole is 0.7–1.3 wt. % (Ti < 0.15 when O = 23) (Figure 6). The XMg of amphibole is 0.60–0.65. Chondrite-normalized REE patterns of amphibole are convex with high Sm-Nd and a negative anomaly for Eu. Primitive mantle-normalized trace element patterns of amphibole show negative anomalies of HFSEs such as Th, Zr and Hf, and U, Sr and Eu (Figure 7).

The XMg and TiO2 content of biotite is 0.62–0.64 and 2.1–2.7 wt. %, respectively.

Anorthite content [100Ca/(Ca + Na) atomic ratio] of plagioclase ranges from 46–55. The K2O content is usually below the detection limit of analysis (<0.2 wt. %).

3.3 U-Pb zircon dating

The results of zircon U-Pb analysis by LA-ICP-MS are presented in Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table S7). The zircon grains in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and hornblende gabbro are mostly less than 300 µm and exhibit a subhedral shape. Cathodoluminescence (CL) images of zircons show both dark and bright color growth domains. Representative CL images of zircon grains with 206Pb/238U ages are shown in Figure 8. The bright-colored domain often surrounds the core domain with the dark CL. Zircons from the Irishiken granitic rock are euhedral with prismatic faces, typically 200 µm in size (Supplementary Figure S4). CL image exhibits concentric oscillatory without inherited core or significant resorption surfaces.

Figure 8. Cathodoluminescence images of representative zircons from the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and hornblende gabbro. Analytical spots for LA-ICP-MS U-Pb dating are shown as circles, with the corresponding 206Pb/238U age (Ma).

The U-Pb isotopic data for zircons are plotted on a Tera-Wasserburg diagram using IsoplotR (Vermeesch, 2018). The individual isotopic ratio of zircon from poikilitic hornblende pyroxenites and hornblende gabbro are mostly consistent, and are located on or very close to the concordia curve of approximately 125–115 Ma (Figure 9). Zircons from the NSD04 (poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite) and hornblende gabbro (NSD05) yielded a well-defined and coherent age population.

Figure 9. Terra-Wasserburg concordia diagrams (left) and 206Pb/238U age (right) of U-Pb zircon data from the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite (Pyroxenite) and hornblende gabbro (Gabbro). Weighted mean of 206Pb/238U age, with the 95% confidence interval shown as a gray-colored band and the dispersion (evaluated at 95% confidence) shown as dotted lines.

The weighted mean 206Pb/238U ages calculated by IsoplotR is 117.5 ± 0.4 Ma (1 σ, n = 37, MSWD = 2.7) for the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite (NSD04), and is 116.3 ± 0.5 Ma (1 σ, n = 16, MSWD = 3) for the hornblende gabbro (NSD05) (Figure 9). Although a limited number of four zircon spots were analyzed for the NSD06 of poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite, these spots yielded concordant individual 206Pb/238U ages of 118–127 Ma. These individual ages are consistent with each other and overlap with uncertainty with the age population from NSD04. The Th/U ratios of all analyzed zircons from both poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and hornblende gabbro are greater than 0.1, indicating a magmatic origin. The weighted mean U-Pb ages of zircons from poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and hornblende gabbro overlap within analytical uncertainty (Figure 9). The identical U-Pb zircon ages are interpreted as the timing of a magmatic event for both ultramafic and gabbroic rocks at approximately 120 Ma.

The age ranges indicated by each U-Pb zircon data are 15 million years for the poikilitic hornblnede pyroxenite and 10 million years for the hornblende gabbro. Itano et al. (2024) reported two U-Pb zircon age populations separated by 10 million years from the poikilitic hornblende UMR in the Hida Belt, based on high-precision analysis using a sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe (SHRIMP) combined with careful petrological observation. This age difference is interpreted as resulting from different zircon forming processes from the same melt, providing petrological evidence of a continuous period of igneous activly over 10 million years. To clarify the significance of the age range of the study samples, further careful high-resolutin and high-precision analysis is required.

The U-Pb zircon data for the Irishiken granitic rock are on the concordia curve on a Tera-Wasserburg diagram, and the mean 206Pb/238U ages for the Irishiken body is 105.9 ± 0.6 Ma (1 σ, n = 27, MSWD = 1.4) (Supplementary Figure S5). This is in good agreement with previous U-Pb zircon data (105.3 ± 0.8 Ma) obtained from the eastern part of the Irishiken body (Takahashi et al., 2016).

4 Discussions

4.1 Phase relationships in the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite

Olivine, orthopyroxene and clinopyroxene in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite are surrounded by amphibole (Figures 2,3), indicating the amphibole formed during later crystallization than other mafic minerals. Poikilitic hornblende exhibits a chemical zoning from high-Ti-REEs pargasitic composition in the core part to low-Ti-REEs rim part. Amphibole in direct contact with olivine and subhedral pyroxene tends to exhibit Ti-rich pargasitic amphibole, whereas vermicular clinopyroxene-amphibole and that in contact with orthopyroxene are low-Ti amphibole. Brown-colored intermediate zone of amphibole exhibits slightly higher LREEs and LREE/HREE ratio than the dark-colored core (Figure 7). The partition coefficient between amphibole and melt is generally lower for LREEs than for HREEs, and amphibole crystallized later from the fractionated melt exhibits a higher LREE/HREE ratio. Vermicular clinopyroxene coexisting with low-Ti amphibole has a lower Al2O3 content than the subhedral clinopyroxene surrounded by high-Ti pargasitic amphibole (Figure 5). The vermicular texture of low-Al clinopyroxene and low-Ti amphibole is interpreted to have formed later than high-Ti pargasitic amphibole, through the reaction between high-Al clinopyroxene and a fractionated melt/hydrous fluid derived from the infiltrated melt that formed the high-Ti pargasitic amphibole. In other words, high-Al clinopyroxene and high-Ti pargasitic amphibole are in equilibrium and represent the phases that existed early on. As discussed later, the chemical composition of the melt in equilibrium with subhedral high-Al clinopyroxene and high-Ti pargasitic amphibole exhibit similar characteristics, indicating that both high-Al clinopyroxene and high-Ti pargasitic amphibole crystallized from the same melt. The absence of Eu and Sr negative anomalies in both high-Ti pargasitic amphibole and high-Al clinopyroxene indicate no plagioclase formed before amphibole crystallization. This is consistent with the absence of plagioclase within the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite.

Orthopyroxene in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite is occasionally found around olivine and generally occurs with low-Ti amphibole domain (Figures 2,3). This textural relationship between orthopyroxene and other phases indicates that orthopyroxene formed after olivine and related to the formation of later low-Ti amphibole, likely through reaction of the pre-existing olivine with fractionated orthopyroxene-saturated melt or high-SiO2 hydrous fluid derived from the infiltrated melt (e.g., Morishita et al., 2011). Olivine tends to exhibit rounded shapes, whereas high-Al clinopyroxene shows subhedral shape. Based on these observations, olivine is interpreted as the earliest crystallization phase or pre-existing phase, and later reacted with melt/fluid, forming either high-Ti pargasitic amphibole and/or orthopyroxene.

The next question is whether olivine formed as the earliest crystallization phase from a melt or existed as a phase within pre-existing rocks such as peridotite. As described later, olivine is assumed to be a pre-existing phase of ultramafic rock and has reacted with the infiltrating melt.

4.2 Estimation of melt compositions in the formation of poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and possible origins

Petrographic and chemical evidence suggests that the dark-colored high-Ti pargasitic amphibole in the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite formed early from a magmatic melt. The melt composition that crystallized dark-colored high-Ti pargasitic amphibole is estimated to contain, approximately 59–67 wt. % SiO2, 17–18 wt. % Al2O3 and 2-4 wt. % MgO at around 1,000 °C, as predicted by the empirical chemometric equation (Zhang et al., 2017) using Thermobar (Wieser et al., 2022) (Supplementary Table S4). We also estimate the trace element composition of equilibrium melt with the dark-colored high-Ti pargasitic hornblende using the partition coefficient of Nandedkar et al. (2016) and (Humphreys et al., 2019) (Supplementary Table S8). The estimated melt compositions from amphibole using two partition coefficients have similar geochemical characteristics. The primitive mantle-normalized trace element patterns of calculated melt compositions from dark-colored high-Ti pargasitic amphibole showed high LREE/HREE ratios, weak positive anomaly of Sr and negative anomalies for HFSEs. These characteristics are similar to those from high-Al clinopyroxene and orthopyroxene using the partition coefficient of McDade et al. (2003) (Supplementary Table S8), which is determined for hydrous high-MgO melt and peridotite system (Figure 10B). Since it was considered that high-Al clinopyroxene and high-Ti pargasitic amphibole were in equilibrium, experimental results of hydrous melt are used.

Figure 10. (A) Primitive-mantle normalized trace element patterns for calculated melts in equilibrium with dark-colored high-Ti pargasitic amphibole from poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite using the partition coefficient of Nandedkar et al. (2016) and Humphreys et al. (2019). (B) Comparison of calculated melts from high-Ti pargasitic amphibole using the partition coefficient of Nandedkar et al. (2016) and calculated melts from high-Al clinopyroxene and orthopyroxene using the partition coefficient of McDade et al. (2003). (C) Comparison of calculated melts from high-Ti pargasitic amphibole using the partition coefficient of Nandedkar et al. (2016) and calculated melts from high-Al clinopyroxene using the partition coefficient obtained from 0.5 GPa experimental results of Adam and Green (2003).

Partition coefficients between clinopyroxene and melt for REEs and other trace elements are suggested to decrease with increasing pressure (Adam and Green, 1994; Bédard, 2014). The trace element content in the melt composition calculated under low-pressure conditions is relatively lower than that under high-pressure conditions. The melt compositions calculated using low-pressure (0.5 GPa) experimental results from Adam and Green (2003) (Supplementary Table S8) show lower trace element contents in the calculated melts than those calculated using McDade et al. (2003) (1.3 GPa) (Figure 10C). The geochemical characteristics of the low-pressure melts consistently show features common to those of the high-pressure melts, such as high LREE/HREE ratios, positive anomaly of Sr and negative anomalies for HFSEs (Figure 10). The following discussion does not change significantly whether regardless of high-pressure or low-pressure data are used (Supplementary Figure S6).

The estimated melt compositions from high-Ti pargasitic amphibole compared with the typical magma compositions of Japanese island arcs (Kimura, 2017) (Figure 11). Among these magma compositions, the chemical characteristics of the estimated melt composition are similar to adakitic melt compositions (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Comparison of calculated melts from high-Ti pargasitic amphibole from high-Ti pargasitic amphibole using partition coefficient of Nandedkar et al. (2016) and Humphreys et al. (2019) with the typical magma compositions of Japanese island arcs (Kimura, 2017) (A,B). Comparison of calculated melts from high-Ti pargasitic amphibole with the compositions of Early Cretaceous adakitic granites (C,D) and High-Mg Andesites (HMA) (E,F) from the Kitakami Mountains, Northeast Japan. Normalization values are from McDonough and Sun (1995). Data for Kitakami adakitic granites and HMA are from Tsuchiya et al. (2007) and Tsuchiya et al. (2005), respectively.

Adakite is an intermediate to felsic igneous rock characterized by high Sr concentration, and low Y and heavy REEs concentrations. Adakite was originally defined by Defant and Drummond (1990) as an arc-related volcanic or intrusive rocks formed by partial melting of young subducted oceanic basalt under amphibole/eclogite facies conditions. Since then, several models have been discussed regarding the origin and tectonic setting of adakitic to related high-Mg andesitic melt genesis (e.g., Martin et al., 2005; Moyen, 2009; Castillo, 2012; Zhang et al., 2021). Partial melting of thickened lower crust under garnet-hornblende/eclogite facies conditions may form adakite melts (Yumul et al., 2000; Chung et al., 2003; Condie, 2005; Wang et al., 2005; Macpherson et al., 2006; Qian and Hermann, 2013). Adakitic melt compositions are formed by the fractional crystallization of garnet and/or amphibole from hydrous basalts (Moyen, 2009; Azizi et al., 2019). The formation of high-Mg andesite involves the partial melting of the subducted basalt and subsequent interaction with wedge mantle peridotite (Rapp et al., 1999; Martin et al., 2005). High-Mg andesitic to high-Mg adakitic compositions can be formed by partial melting of metasomatized mantle through slab-melt interaction, followed by mixing with basaltic magmas (Yogodzinski and Kelemen, 1998; Danyushevsky et al., 2008).

Although constraining tectonic model for the formation of adakitic melts in relation to poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite is difficult, it is noted that adakitic granitic rocks and High-Mg Andesite (HMA) have been reported from the South Kitakami Mountains located in the northeastern part of the Abukuma Mountains (Tsuchiya and Kanisawa, 1994; Tsuchiya et al., 2005; 2007; 2014; 2015) (Figure 1). These adakitic magmas and associated high-Mg andesite formed at 128–113 Ma, according to U-Pb zircon dating (Tsuchiya et al., 2014; 2015; Osozawa et al., 2019). The chemical characteristics of adakitic and related HMAs are similar to those of the melt compositions calculated from high-Ti pargasitic amphibole in the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite (Figure 11). The magmatic ages of the Kitakami adakites and associated HMAs are consistent with U-Pb dating of poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite in this study. Based on temporal and spatial relationships, as well as the melt composition inferred for the formation of the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite, it is suggested that the magmatic event forming adakitic to high-Mg andesite recorded in the Kitakami Mountains and the study area may have been the same magmatic event.

Trace element and isotopic modeling indicates that the Kitakami adakitic magmas originated from partial melting of a mixed source comprising basaltic oceanic crust (N-MORB) with a contribution from subducted sediments (Tsuchiya et al., 2007). The Kitakami High-Mg andesitic rock (HMA hereafter) rarely contains ultramafic xenoliths. Mass balance calculations support an Assimilation-Fractional-Crystallization (AFC) model in the Kitakami HMA formation. The Kitakami HMA can be generated by slab-derived adakitic melt assimilating primordial mantle peridotite while crystallizing phases like orthopyroxene, olivine, and hornblende (Tsuchiya et al., 2005). Micorgabbro boulder containing dunitic xenoliths was also reported from the Kitakami Mountains (Yamasaki and Uchino, 2023). The equilibrium melt compositions with clinopyroxene in the microgabbro are in good agreement with HMAs (bajaite). Yamasaki and Uchino (2023) propose that bajaitic HMA formation is due to the assimilation of dunitic cumulates of lower crustal origin by adakite-related felsic magma. Although the origin of ultramafic rocks differs between Tsuchiya et al. (2005) and Yamasaki and Uchino (2023), the process by which high-Mg andesitic melts form through the reaction between ultramafic rocks and adakitic felsic melt followed by fractional crystallization is identical. The low forsterite content of olivine in the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite supports a cumulate origin derived from earlier magmatic event rather than residual peridotite.

4.3 Pressure-temperature conditions recorded in amphibole in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite

Among the amphiboles, the dark-colored Ti-rich pargasitic amphibole is interpreted as an early crystallization amphibole from the melt. The pressure-temperature conditions recorded in the dark-colored pargasitic amphibole in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite were estimated using Thermobar (Wieser et al., 2022) based on AmpTB2 of Ridolfi (2021). The pressure conditions are estimated to be in the range of 0.4 GPa–0.7 GPa, and the temperature conditions are estimated to be in the range of 870 °C–940 °C (Gray square in Figure 12). The uncertainty of the estimated pressure and temperature are approximately 15% of the estimated pressure and ±20 °C, respectively. Because the dark-colored pargasitic amphibole in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite contains ilmenite exsolution lamellae (Figure 3), indicating that the original composition prior to exsolution lamellae formation had a higher TiO2 content than the present composition. To confirm the difference between the original composition and the other brown amphibole without exsolution, the original composition was estimated and applied to the estimation of P-T conditions. The original amphibole composition was calculated based on ilmenite volume. Ilmenite volume was measured using ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012) from backscatter images of the ilmenite-bearing dark-colored amphibole core of NSD04 sample (e.g., Figure 3E) and mineral density. The modal abundance of ilmenite was measured to be approximately 2%. The contents of MnO and Cr2O3 were ignored. The total oxide content was recalculated as 98 wt. %, excluding H2O, Cl and F (Supplementary Table S4). The TiO2 content in the reconstituted hornblende composition was 3.4 wt. %. The reconstructed composition likely overestimates the volume of ilmenite. This is due to the strong contrast between bright ilmenite and dark hornblende in the BSE image. The TiO2 content obtained by LA-ICPMS from dark-colored amphibole is less than 3 wt. %, although it may substantially include ilmenite exsolution. Although the reconstructed dark-colored amphibole composition contains uncertainties, its P-T conditions are estimated at 0.47 GPa at 930 °C (solid star in Figure 12), which falls within the P-T conditions inferred from the dark-colored Ti-rich parasitic amphibole.

Figure 12. Pressure-temperature (P–T) conditions for hornblende formation in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite (gray square area). Estimated P-T paths in andalusite-kyanite-sillimanite gneisses of the Nishidohira Formation (Hiroi and Kobayashi, 1996; Yoneguchi et al., 2021), and P-T conditions for staurolite-bearing pelitic metamorphosed xenoliths in hornblende pyroxenite body (Hiroi and Kobayashi, 1995) are also shown. Phase diagram of the primitive magnesian andesite composition from water saturation experiments is from Krawczynski et al. (2012). Abbreviations are follows: Ol, olivine; Cpx, clinopyroxene; Opx, orthopyroxene; Plag, plagioclase; Amph, amphibole; NNO, Ni-NiO buffer.

The estimated P-T conditions for pargasitic amphibole formation plot within the amphibole stability field on a phase diagram for a magnesian andesite composition (Krawczynski et al., 2012) (Figure 12). These conditions are observed to lie outside the olivine stability field during the late crystallization stage. This is consistent with the observed rounded morphology of olivine in poikilitic hornblende, suggesting olivine underwent partial resorption by reaction with melt of the formation of poikilitic hornblende.

Yoneguchi et al. (2021) reveal P-T trajectory of pelitic metamorphic rock of the Nishidohira formation. P-T condition of prograde mineral assemblages is estimated as 0.48–0.67 GPa and 530 °C–570 °C, and up to 0.9 GPa from Raman elastic geobarometry on quartz inclusion in garnet (Figure 12). The peak metamorphism is estimated at 139 ± 24 Ma using electron microprobe Th-U-Pb dating of monazite intergrowing. Yoneguchi et al. (2021) also suggested the rapid exhumation of the Nishidohira metamorphic rock, probably the 120–105 Ma thermal event in relation to the activity of younger felsic magmatic intrusion. The estimated pressure conditions and U-Pb zircon dating of poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite formation correspond closely with this magmatic event.

4.4 Relationships between poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and hornblende gabbro, and implication for the geological evolution of the study area

The spatial and temporal relationship between the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and hornblende gabbro strongly suggests that they formed during the same igneous event. Chondrite-normalized REE patterns and primitive mantle-normalized patterns of amphibole generally exhibit similar characteristics, such as relatively higher LREEs than MREE and HREES (Figure 7). It is reasonable to consider that these rocks were formed during the same magmatic event.

The XMg of amphibole in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite is generally higher than that in hornblende gabbro. The difference in XMg of amphibole in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and hornblende gabbro can be explained by the following two scenarios: (1) the formation of the ultramafic rocks prior to gabbroic rocks from the same parental melt, or (2) reaction between pre-existing high-Mg ultramafic rocks and low-Mg melt. Ad discussed in previous sections, the melt composition in involved in the formation of poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite is estimated to be adakitic to high-Mg andesitic composition. Based on this, the second scenario is further considered here. The petrological transition from hornblende-rich ultramafic rocks to hornblende gabbroic rocks is experimentally formed through crystallization during cooling following the reaction between peridotite and hydrated basaltic melt (Wang et al., 2021). Hornblende-rich ultramafic rocks forms through the partial reaction and cooling of pre-existing ultramafic rocks with hydrated melt, whereas hornblende gabbro forms in melt-rich zones. The high XMg composition of amphibolite is buffered by the pre-existing high-Mg ultramafic rocks. Accordingly, the reaction between pre-existing ultramafic rocks and adakite to high-Mg andesitic melts likely forms poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite at low melt/rock ratios and hornblende gabbro at high melt/rock ratios. The relationship between poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and hornblende gabbro is similar to that between dunitic xenoliths and their host microgabbro in the Kitakami Mountains (Yamasaki and Uchino, 2023).

Trace element content of amphiboles in hornblnede gabbro is, however, slightly lower than in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite. Light REEs tend to be relatively lower in hornblende gabbro than in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite. The strong negative anomalies of U and Th are more pronounced in hornblende gabbro than in poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite. Titanite and apatite, which are Ca-bearing mineral with high concentrations of trace elements, are present in fairly significant amounts in hornblende gabbro (Figure 4). The trace element patterns of amphibole in hornblende gabbro are interpreted to have been influenced by the crystallization of titanite and apatite from a melt. The shape of plagioclase is generally not subhedral to euhedral (Figure 4), indicating that plagioclase is a late crystallization phase. The phase diagram for high-Mg andesite compositions at higher than 0.5 GPa (Figure 12) is consistent with that plagioclase is a later crystallizing phase than amphibole. The early crystallization of Ca-rich minerals such as amphibole, titanite and apatite led to depletion of Ca and trace element abundance in the fractionated melt. This is thought to be the reason why the plagioclase in hornblende gabbro has low anorthite content, despite the melt forming hornblende gabbro having a high-water content.

The contemporaneous adakitic magmatism across both the Abukuma and Kitakami regions implies a large-scale tectonic event in this region. The Early Cretaceous adakitic magmatism in the Kitakami Mountains was interpreted by the subduction of an oceanic spreading ridge (Tsuchiya et al., 2005; 2007; 2015). During the Early Cretaceous, the northeast Japan was an active continental margin on the eastern edge of the Eurasian plate, where the Izanagi (or Kula) plate was subducting westward (Maruyama et al., 1997; Seton et al., 2012). The presence of adakitic magmatic activity in both Kitakami and Abukuma Mountains strongly supports a period of unusual thermal conditions in the subduction zone at eastern margin of the Eurasian plate, likely caused by the subduction of a young and consequently hot oceanic plate.

5 Conclusion

This study comprehensively investigates the petrogenesis of a unique poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite from the southern Abukuma Mountains, Northeast Japan. The poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite represents a key lithological record of Early Cretaceous adakitic magmatism. Petrological and geochemical analyses of the poikilitic hornblende and other minerals demonstrate that the pyroxenite formed through the infiltration and reaction of adakitic to HMA melts with pre-existing ultramafic rocks. Geochronological data from zircon yields a consistent magmatic age of 116–117 Ma for both the poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite and coeval hornblende gabbro. This adakitic influence is not an isolated phenomenon, as similar-aged adakitic magmatism is documented across the Kitakami Mountains, Northeast Japan. This process provides a petrological link to a large-scale, unusual thermal event in the Early Cretaceous subduction zone along the eastern Eurasian plate margin, most plausibly attributed to the subduction of a young, hot oceanic plate (Izanagi or Kula Plate).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AW: Data curation, Writing – original draft. MF: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. KI: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. YH: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. AT: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. TM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. A Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (no. JP19KK0092, JP23K22603 to TM).

Acknowledgements

Comments from Alex Kotov and three reviews improved the revised manuscript significantly. We are grateful to Tomoyuki Mizukami for analytical support and valuable comments. We were able to make use of analytical instruments housed at the GSJ-Lab (M4 Tornado, Bruker) of the Geological Survey of Japan, AIST.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer TY declared a shared affiliation with the author(s) YH to the handling editor at the time of review.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author(s) verify and take full responsibility for the use of generative AI in the preparation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgeoc.2025.1697337/full#supplementary-material

References

Adam, J., and Green, T. H. (1994). The effects of pressure and temperature on the partitioning of Ti, Sr and REE between amphibole, clinopyroxene and basanitic melts. Chem. Geol. 117, 219–233. doi:10.1016/0009-2541(94)90129-5

Adam, J., and Green, T. (2003). The influence of pressure, mineral composition and water on trace element partitioning between clinopyroxene, amphibole and basanitic melts. Eur. J. Mineral. 15, 831–841. doi:10.1127/0935-1221/2003/0015-0831

Azizi, H., Stern, R. J., Topuz, G., Asahara, Y., and Moghadam, H. S. (2019). Late Paleocene adakitic granitoid from NW Iran and comparison with adakites in the NE Turkey: adakitic melt generation in normal continental crust. Lithos 346-347, 105151–105347. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2019.105151

Bédard, J. H. (2014). Parameterizations of calcic clinopyroxene - melt trace element partition coefficients. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 15, 303–336. doi:10.1002/2013GC005112

Castillo, P. R. (2012). Adakite petrogenesis. Lithos 134–135, 304–316. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2011.09.013

Chung, S.-L., Liu, D., Ji, J., Chu, M.-F., Lee, H.-Y., Wen, D.-J., et al. (2003). Adakites from continental collision zones: melting of thickened lower crust beneath southern Tibet. Geology 31, 1021–1024. doi:10.1130/G19796.1

Collins, W. J., Murphy, J. B., Johnson, T. E., and Huang, H. Q. (2020). Critical role of water in the formation of continental crust. Nat. Geosci. 13, 331–338. doi:10.1038/s41561-020-0573-6

Condie, K. C. (2005). TTGs and adakites: are they both slab melts? Lithos 80, 33–44. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2003.11.001

Danyushevsky, L. V., Falloon, T. J., Crawford, A. J., Tetroeva, S. A., Leslie, R. L., and Verbeeten, A. (2008). High-Mg adakites from Kadavu Island Group, Fiji, Southwest Pacific: evidence for the mantle origin of adakite parental melts. Geology 36, 499–502. doi:10.1130/G24349A.1

Davidson, J., Turner, S., Handley, H., Macpherson, C., and Dosseto, A. (2007). Amphibole “sponge” in arc crust? Geology 35, 787. doi:10.1130/G23637A.1

Defant, M. J., and Drummond, M. S. (1990). Derivation of some modern arc magmas by melting of young subducted lithosphere. Nature 347, 662–665. doi:10.1038/347662a0

Faure, M., Lalevée, F., Gusokujima, Y., Iiyama, J. T., and Cadet, J. P. (1986). The pre-cretaceous deep-seated tectonics of the Abukuma massif and its place in the structural framework of Japan. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 77, 384–398. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(86)90148-2

Hawthorne, F. C., Oberti, R., Harlow, G. E., Maresch, W. V., Martin, R. F., Schumacher, J. C., et al. (2012). IMA report: nomenclature of the amphibole supergroup. Am. Mineralogist 97, 2031–2048. doi:10.2138/am.2012.4276

Hidalgo, P. J., and Rooney, T. O. (2010). Crystal fractionation processes at Baru volcano from the deep to shallow crust. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 11. doi:10.1029/2010GC003262

Hiroi, Y., and Kobayashi, E. (1995). New occurrences of staurolite in the western Hitachi district, Abukuma metamorphic terrane, northeastern Japan. Jour. Min. Pet. Econ. Geol. 90, 247–256. doi:10.2465/ganko.90.247

Hiroi, Y., and Kobayashi, E. (1996). Origin of andalusite-kyanite-sillimanite aggregates in the Nishidohira pelitic rocks in the southernmost part of the Abukuma Plateau, Northeast Japan, and the P-T path. Jour. Min. Pet. Econ. Geol. 91, 220–234. doi:10.2465/ganko.91.220

Humphreys, M. C. S., Cooper, G. F., Zhang, J., Loewen, M., Kent, A. J. R., Macpherson, C. G., et al. (2019). Unravelling the complexity of magma plumbing at Mount St. Helens: a new trace element partitioning scheme for amphibole. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 174, 9. doi:10.1007/s00410-018-1543-5

Ishimaru, S., Arai, S., Tamura, A., Takeuchi, M., and Kiji, M. (2009). Subarc magmatic and hydration processes inferred from a hornblende peridotite xenolith in spessartite from Kyoto, Japan. J. Mineralogical Petrological Sci. 104, 97–104. doi:10.2465/jmps.081021b

Ishiwatari, A. (1985). Granulite-Facies metacumulates of the Yakuno ophiolite, Japan: evidence for unusually thick Oceanic crust. J. Petrology 26 (1), 1–30. doi:10.1093/petrology/26.1.1

Itano, K., Morishita, T., Nishio, I., Guotana, J. M., Ogusu, Y., Ishizuka, O., et al. (2021). Petrogenesis of amphibole-rich ultramafic rocks in the Hida metamorphic complex, Japan: its role in arc crust differentiation. Lithos 106440, 404–405. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2021.106440

Itano, K., Takehara, M., Horie, K., Iizuka, T., Nishio, I., and Morishita, T. (2024). A long-lived mafic magma reservoir: zircon evidence from a hornblende peridotite in the Hida Belt, Japan. Geology 52, 3–6. doi:10.1130/G51560.1

Kanamitsu, G., Shimojo, M., Hirata, T., Yokoyama, T. D., and Otoh, S. (2011). New detrital-zircon ages from the Hitachi area in Northeast Japan and their geological significance. J. Geogr. (Chigaku Zasshi) 120, 889–909. doi:10.5026/jgeography.120.889

Kimura, J. (2017). Modeling chemical geodynamics of subduction zones using the Arc Basalt Simulator version 5. Geosphere 13, GES01468.1. doi:10.1130/GES01468.1

Kratzmann, D. J., Carey, S., Scasso, R. A., and Naranjo, J.-A. (2010). Role of cryptic amphibole crystallization in magma differentiation at Hudson volcano, Southern Volcanic Zone, Chile. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 159 (2), 237–264. doi:10.1007/s00410-009-0426-1

Krawczynski, M. J., Grove, T. L., and Behrens, H. (2012). Amphibole stability in primitive arc magmas: effects of temperature, H2O content, and oxygen fugacity. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 164, 317–339. doi:10.1007/s00410-012-0740-x

Macpherson, C. G., Dreher, S. T., and Thirlwall, M. F. (2006). Adakites without slab melting: high pressure differentiation of island arc magma, Mindanao, the Philippines. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 243, 581–593. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.12.034

Martin, H., Smithies, R. H., Rapp, R., Moyen, J. F., and Champion, D. (2005). An overview of adakite, tonalite–trondhjemite–granodiorite (TTG), and sanukitoid: relationships and some implications for crustal evolution. Lithos 79, 1–24. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2004.04.048

Maruyama, S., Isozaki, Y., Kimura, G., and Terabayashi, M. (1997). Paleogeographic maps of the Japanese Islands: plate tectonic synthesis from 750 Ma to the present. Isl. Arc 6, 121–142. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1738.1997.tb00043.x

McDade, P., Blundy, J. D., and Wood, B. J. (2003). Trace element partitioning between mantle wedge peridotite and hydrous MgO-rich melt. Am. Mineralogist 88, 1825–1831. doi:10.2138/am-2003-11-1225

McDonough, W. F., and Sun, S.-S. (1995). The composition of the Earth. Chem. Geol. 120, 223–253. doi:10.1016/0009-2541(94)00140-4

Miyashiro, A. (1961). Evolution of metamorphic belts. J. Petrol. 2 (3), 277–311. doi:10.1093/petrology/2.3.277

Morishita, T., Dilek, Y., Shallo, M., Tamura, A., and Arai, S. (2011). Insight into the uppermost mantle section of a maturing arc: the Eastern Mirdita ophiolite, Albania. Lithos 124, 215–226. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2010.10.003

Moyen, J. F. (2009). High Sr/Y and La/Yb ratios: the meaning of the “adakitic signature.”. Lithos 112, 556–574. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2009.04.001

Nandedkar, R. H., Hürlimann, N., Ulmer, P., and Müntener, O. (2016). Amphibole–melt trace element partitioning of fractionating calc-alkaline magmas in the lower crust: an experimental study. Contributions Mineralogy Petrology 171, 71. doi:10.1007/s00410-016-1278-0

Noto, S. (1977). Ultrabasic rocks found in the so-called Ryoke zone, Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture, Japan. Jour. Geol. Soc. Jpn. 83, 543–544. doi:10.5575/geosoc.83.543

Ogiso, K. (1984). Basic rocks from the Miho area, Iida City, Nagano Prefecture (I) – mode of occurrence and petrography-. J. Jpn. Assoc. Mineralogists, Petrologists Econ. Geol. 79, 239–248. doi:10.2465/ganko1941.79.239

Osozawa, S., Usuki, T., Usuki, M., Wakabayashi, J., and Jahn, B. M. (2019). Trace elemental and sr-nd-hf isotopic compositions, and U-Pb ages for the Kitakami adakitic plutons: insights into interactions with the early Cretaceous TRT triple junction offshore Japan. J. Asian Earth Sci. 184, 103968. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2019.103968

Ozawa, K., Maekawa, H., Shibata, K., Asahara, Y., and Yoshikawa, M. (2015). Evolution processes of Ordovician-Devonian arc system in the South-Kitakami Massif and its relevance to the Ordovician ophiolite pulse. Isl. Arc 24, 73–118. doi:10.1111/iar.12100

Qian, Q., and Hermann, J. (2013). Partial melting of lower crust at 10-15 kbar: constraints on adakite and TTG formation. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 165, 1195–1224. doi:10.1007/s00410-013-0854-9

Rapp, R. P., Shimizu, N., Norman, M. D., and Applegate, G. S. (1999). Reaction between slab-derived melts and peridotite in the mantle wedge: experimental constraints at 3.8 GPa. Chem. Geol. 160, 335–356. doi:10.1016/S0009-2541(99)00106-0

Ridolfi, F. (2021). Amp-tb2: an updated model for calcic amphibole thermobarometry. Minerals 11, 324–329. doi:10.3390/min11030324

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S., and Eliceiri, K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2089

Seton, M., Müller, R. D., Zahirovic, S., Gaina, C., Torsvik, T., Shephard, G., et al. (2012). Global continental and ocean basin reconstructions since 200Ma. Earth Sci. Rev. 113, 212–270. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2012.03.002

Shimaoka, H., and Watanabe, J. (1976). On the “Nishidohira metamorphics” of the pre-abean stage in central Japan:1.Description and distribution of the lithofacies. Jour. Geol. Soc. Jpn. 82, 531–542. doi:10.5575/geosoc.82.531

Shimaoka, H., Watanabe, J., and Tsuchiya, T. (1988). Plymetamorphism of the Tamadare Amphibolite Complex - studies on the Koshidai-Takaboyama-Daioh’in structural belt in the Abukuma Mountains, northeast Japan (Part 3). Earth Sci. 42, 359–370. doi:10.15080/agcjchikyukagaku.32.1_15

Tagiri, M. (1971). Metamorphic rocks of the Hitachi district in the southern Abukuma plateau. J. Jpn. Assoc. Mineralogists, Petrologists Econ. Geol. 65, 77–103. doi:10.2465/ganko1941.65.77

Tagiri, M., Morimoto, M., Mochizuki, R., Yokosuka, A., Dunkley, D. J., and Adachi, T. (2010). Hitachi metamorphic rocks: occurrence and geology of meta-granitic rocks with Cambrian SHRIMP Zircon Age. Chigaku Zasshi (Jounal Geogr.) 119, 245–256. doi:10.5026/jgeography.119.245

Tagiri, M., Dunkley, D. J., Adachi, T., Hiroi, Y., and Fanning, C. M. (2011). SHRIMP dating of magmatism in the Hitachi metamorphic terrane, Abukuma Belt, Japan: evidence for a Cambrian volcanic arc. Isl. Arc 20, 259–279. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1738.2011.00764.x

Tagiri, M., Horie, K., and Adachi, T. (2016). Revised stratigraphy and zircon U-Pb age data of the Hitachi metamorphic formations in the southern Abukuma Mountains, and reconstruction of the basement of the Northeast Japan Arc before the opening of the Japan Sea. Jour. Geol. Soc. Jpn. 122, 231–247. doi:10.5575/geosoc.2016.0012

Takahashi, Y., Mikoshiba, M., Kubo, K., Iwano, H., Danhara, T., and Hirata, T. (2016). Zircon U-Pb ages of plutonic rocks in the southern Abukuma Mountains: implications for Cretaceous geotectonic evolution of the Abukuma Belt. Isl. Arc 25, 154–188. doi:10.1111/iar.12145

Tanaka, H., Kanisawa, S., and Onuki, H. (1982). Petrology of the Nishidohira cortlandtitic mass in the southern Abukuma Mountains, Northeast Japan. J. Jpn. Assoc. Mineralogists, Petrologists Econ. Geol. 77, 438–454. doi:10.2465/ganko1941.77.438

Tanaka, H., Huang, C.-H., Nakamura, Y., Kurokawa, E., and Nobusaka, M. (1987). Petrology of an epizonal gabbroic suite: the Batow pluton, Yamizo Mountains, Central Japan. J. Jpn. Assoc. Mineralogists, Petrologists Econ. Geol. 82, 419–432. doi:10.2465/ganko1941.82.419

Tiepolo, M., Tribuzio, R., and Langone, A. (2011). High-mg andesite petrogenesis by amphibole crystallization and ultramafic crust assimilation: evidence from Adamello hornblendites (Central Alps, Italy). J. Petrology 52, 1011–1045. doi:10.1093/petrology/egr016

Tsuchiya, N., and Kanisawa, S. (1994). Early Cretaceous Sr-rich silicic magmatism by slab melting in the Kitakami Mountains, northeast Japan. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 99, 22205–22220. doi:10.1029/94JB00458

Tsuchiya, N., Suzuki, S., Kimura, J. I., and Kagami, H. (2005). Evidence for slab melt/mantle reaction: petrogenesis of Early Cretaceous and Eocene high-Mg andesites from the Kitakami Mountains, Japan. Lithos 79, 179–206. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2004.04.053

Tsuchiya, N., Kimura, J. I., and Kagami, H. (2007). Petrogenesis of Early Cretaceous adakitic granites from the Kitakami Mountains, Japan. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 167, 134–159. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2007.07.002

Tsuchiya, N., Takeda, T., Tani, K., Adachi, T., Nakano, N., Osanai, Y., et al. (2014). Zircon U–Pb age and its geological significance of late Carboniferous and Early Cretaceous adakitic granites from eastern margin of the Abukuma Mountains, Japan. Jour. Geol. Soc. Jpn. 120, 37–51. doi:10.5575/geosoc.2014.0003

Tsuchiya, N., Takeda, T., Adachi, T., Nakano, N., Osanai, Y., and Adachi, Y. (2015). Early Cretaceous adakitic magmatism and tectonics in the Kitakami Mountains, Japan. Jpn. Mag. Mineralogical Petrological Sci. 44 (2), 69–90. doi:10.2465/gkk.131228

Vermeesch, P. (2018). IsoplotR: a free and open toolbox for geochronology. Geosci. Front. 9, 1479–1493. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2018.04.001

Wallis, S. R., Yamaoka, K., Mori, H., Ishiwatari, A., Miyazaki, K., and Ueda, H. (2020). The basement geology of Japan from A to Z. Isl. Arc 29, e12339. doi:10.1111/iar.12339

Wang, Q., McDermott, F., Xu, J. F., Bellon, H., and Zhu, Y. T. (2005). Cenozoic K-rich adakitic volcanic rocks in the Hohxil area, northern Tibet: Lower-crustal melting in an intracontinental setting. Geology 33, 465–468. doi:10.1130/G21522.1

Wang, C., Liang, Y., and Xu, W. (2021). Formation of amphibole-bearing peridotite and amphibole-bearing pyroxenite through hydrous melt-peridotite reaction and in situ crystallization: an experimental Study. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2020JB019382. doi:10.1029/2020JB019382

Watanabe, J., and Bikerman, M. (1971). K-Ar age of the Nishidohira gneiss complex in the Abukuma Mountains, Japan. Earth Sci. (Chikyu Kagaku) 25, 23–26. doi:10.15080/agcjchikyukagaku.25.1_23

Wieser, P. E., Petrelli, M., Lubbers, J., Wieser, E., Ozaydin, S., Kent, A. J. R., et al. (2022). Thermobar: an open-source Python3 tool for thermobarometry and hygrometry. Volcanica 5, 349–384. doi:10.30909/vol.05.02.349384

Williams, G. H. (1886). The peridotites of the Cortlandt series on the Hudson River near Peekskill. Amer. Jour. Sci. 31, 26–31. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-31.181.26

Yagi, K. (1944). Petro-chemical studies of ultra-basic rocks (I). J. Jpn. Assoc. Mineralogists, Petrologists Econ. Geol. 32, 60–71. doi:10.2465/ganko1941.32.60

Yamasaki, T., and Uchino, T. (2023). Assimilation of lower-crustal dunite xenoliths into adakite-related felsic magma: new insights into the production of Bajaitic high-Mg andesites. J. Asian Earth Sci. 249, 105613. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2023.105613

Yamasaki, T., Aoya, M., Kimura, N., and Miyazaki, K. (2012). Petrological feature of the Uzukiyama mafic plutonic complex, Iida city, Nagano Prefecture. Bull. Geol. Surv. Jpn. 63, 1–19. doi:10.9795/bullgsj.63.1

Yogodzinski, G. M., and Kelemen, P. B. (1998). Slab melting in the Aleutians: implications of an ion probe study of clinopyroxene in primitive adakite and basalt. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 158, 53–65. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(98)00041-7

Yoneguchi, Y., Tsunogae, T., Takahashi, K., Sakuwaha, K. G., and Ikehata, K. (2021). Pressure-temperature evolution of andalusite-kyanite-sillimanite-bearing pelitic schists from Nishidohira, southern Abukuma Mountains, Northeast Japan: implications for Cretaceous rapid burial and exhumation in the Northeast Asian continental margin. Lithos 406–407, 106522. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2021.106522

Yoshimura, T. (1940). Spinel-bearing gabbroic rocks from Kazisima, Ehime prefecture (part I). Jour. Geol. Soc. Jpn. 47, 265–269. doi:10.5575/geosoc.47.265

Yumur, G. P. Jr., Dimalanta, C. B., Bellon, H., Faustino, D. V., De Jesus, J. V., Tamayo, R. A. Jr., et al. (2000). Adakitic lavas in the Central Luzon back-arc region, Philippines: lower crust partial melting products? Isl. Arc.9, 499–512. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1738.2000.00297.x

Zhang, J., Humphreys, M. C. S., Cooper, G. F., Davidson, J. P., and Macpherson, C. G. (2017). Magma mush chemistry at subduction zones, revealed by new melt major element inversion from calcic amphiboles. Am. Mineralogist 102, 1353–1367. doi:10.2138/am-2017-5928

Keywords: melt-rock interaction, ultramafic rocks, adakite, Island Arc, poikilitic hornblende ultramafic rock, U-Pb zircon dating, Abukuma Mountains (Japan)

Citation: Wakazono A, Fukuyama M, Itano K, Harigane Y, Tamura A and Morishita T (2025) Poikilitic hornblende pyroxenite in the southern end of the Abukuma Mountains, Northeast Japan, as result of adakitic magmatism. Front. Geochem. 3:1697337. doi: 10.3389/fgeoc.2025.1697337

Received: 02 September 2025; Accepted: 20 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Michael Roden, University of Georgia, United StatesReviewed by:

Alexey Kotov, Tokyo University of Science, JapanChunguang Wang, Jilin University, China

Alberto Zanetti, National Research Council (CNR), Italy

Copyright © 2025 Wakazono, Fukuyama, Itano, Harigane, Tamura and Morishita. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tomoaki Morishita, bW9yaXB0YUBzZS5rYW5hemF3YS11LmFjLmpw

Akira Wakazono1

Akira Wakazono1 Mayuko Fukuyama

Mayuko Fukuyama Keita Itano

Keita Itano Tomoaki Morishita

Tomoaki Morishita