- 1Hue Central Hospital, Hue, Vietnam

- 2Cure2Children Foundation, Florence, Italy

- 3Hue University, Hue, Vietnam

- 4Universidade Federal de Sao Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) is a relatively rare complication of bone marrow transplantation (BMT) associated with a high risk of mortality. It generally occurs in the early post-transplant phase during severe thrombocytopenia; however, since most thrombocytopenic cases do not develop DAH, cofactors are at play. Here, we discuss the case of a 4-year-old male child with mild asymptomatic hemophilia A discovered on routine evaluation pre-BMT, who developed DAH after a fully matched sibling BMT for HbE/Beta-thalassemia. The patient presented on day +21 post-BMT with sudden onset of cough followed one day later by hemoptysis. He had received FVIII supplementation with PTT normalization and FVIII levels of 28%. A chest CT scan showed interstitial lung disease with areas of ground glass bilaterally, mainly in the lower lobes. A radiological diagnosis of DAH was made, and the child was treated with additional FVIII concentrate (Advate), blow-by oxygen supplementation, red blood cells transfusion, platelet transfusion, methylprednisolone, tranexamic acid, and antioxidants (vitamin C and E). He responded well and recovered in a few days. Mild hemophilia associated with DAH post-BMT has never been reported before, however, it should be considered as a potentially treatable cause of DAH after BMT. FVIII levels should be part of the routine workup of children developing DAH post-transplantation. In the presence of thrombocytopenia, high FVIII levels of >30-40% might be required to prevent/treat DAH.

Introduction

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) is a critical condition that involves the accumulation of blood within the alveolar spaces of the lung. Although uncommon, it represents a serious complication in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), with a high mortality risk (1–7). This condition frequently develops in the first 30 days post-transplantation (8, 9), and is marked by shortness of breath, pulmonary infiltrates visible on chest X-ray, and increasingly blood-stained samples obtained through bronchoalveolar lavage (10, 11). Robines et al. were the first to report DAH in adults undergoing autologous transplant (12). Since then, numerous cases have been documented, involving both transplant-related and non-transplant-related coagulation disorders (13, 14). The underlying mechanisms of DAH after transplantation are complex, involving immune system dysregulation, inflammation, and damage to the vascular and alveolar structures. In patients with hemophilia, FVIII deficiency may exacerbate post-transplant bleeding and contribute to the development of DAH (13).

Case report

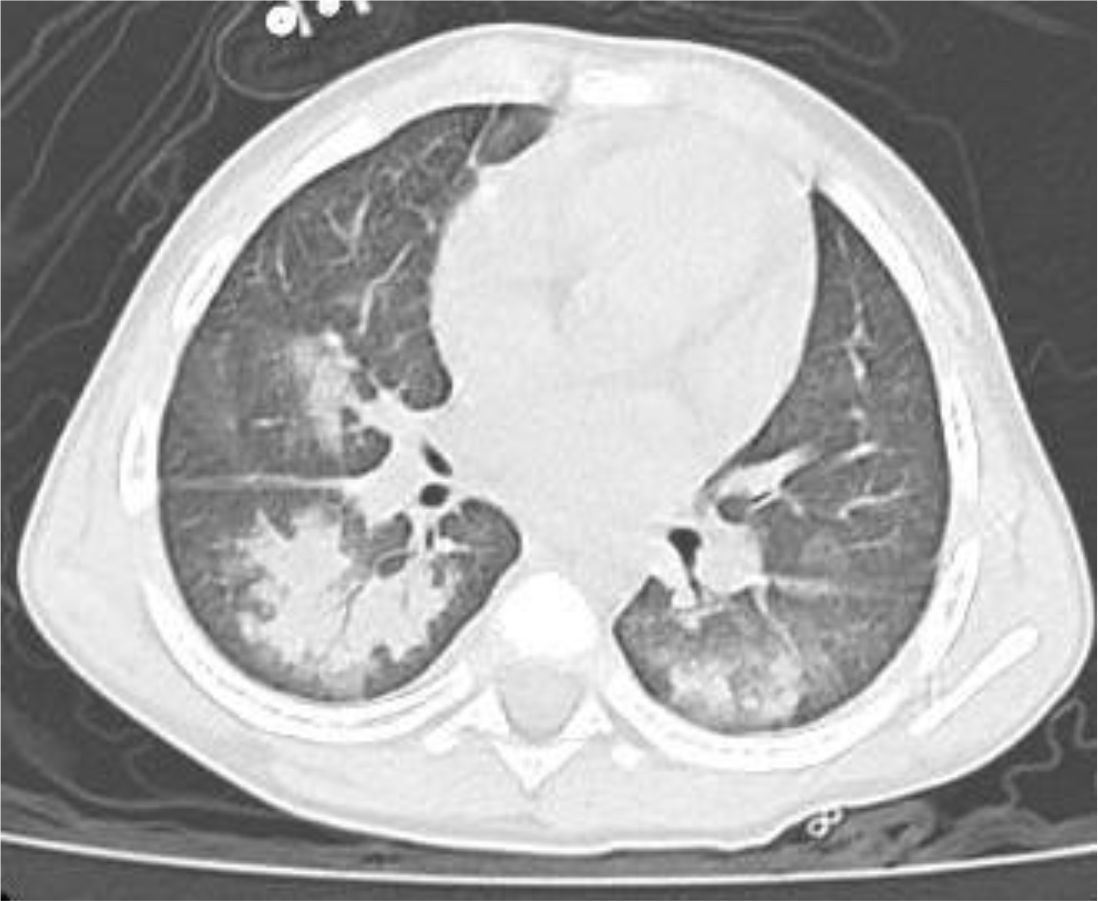

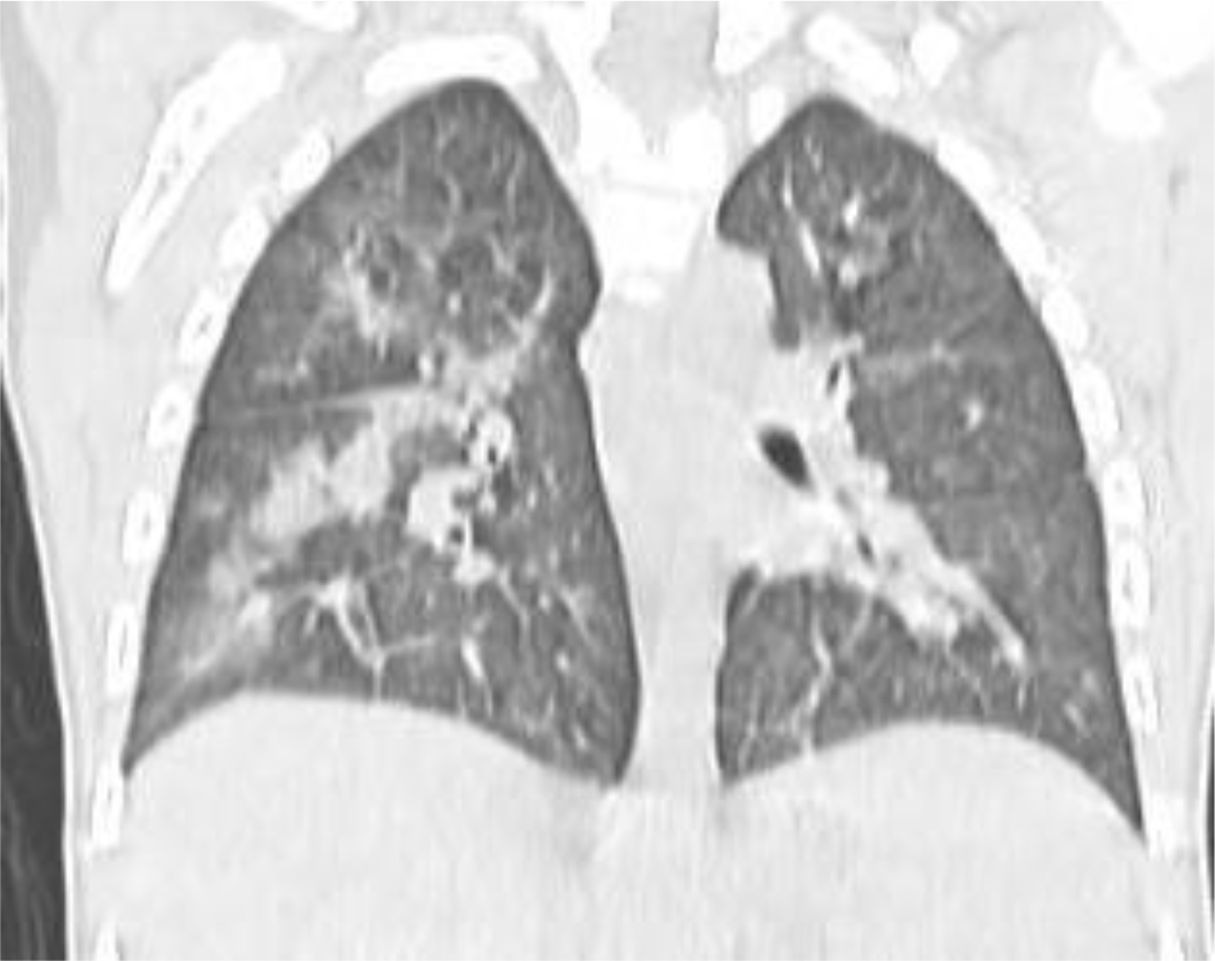

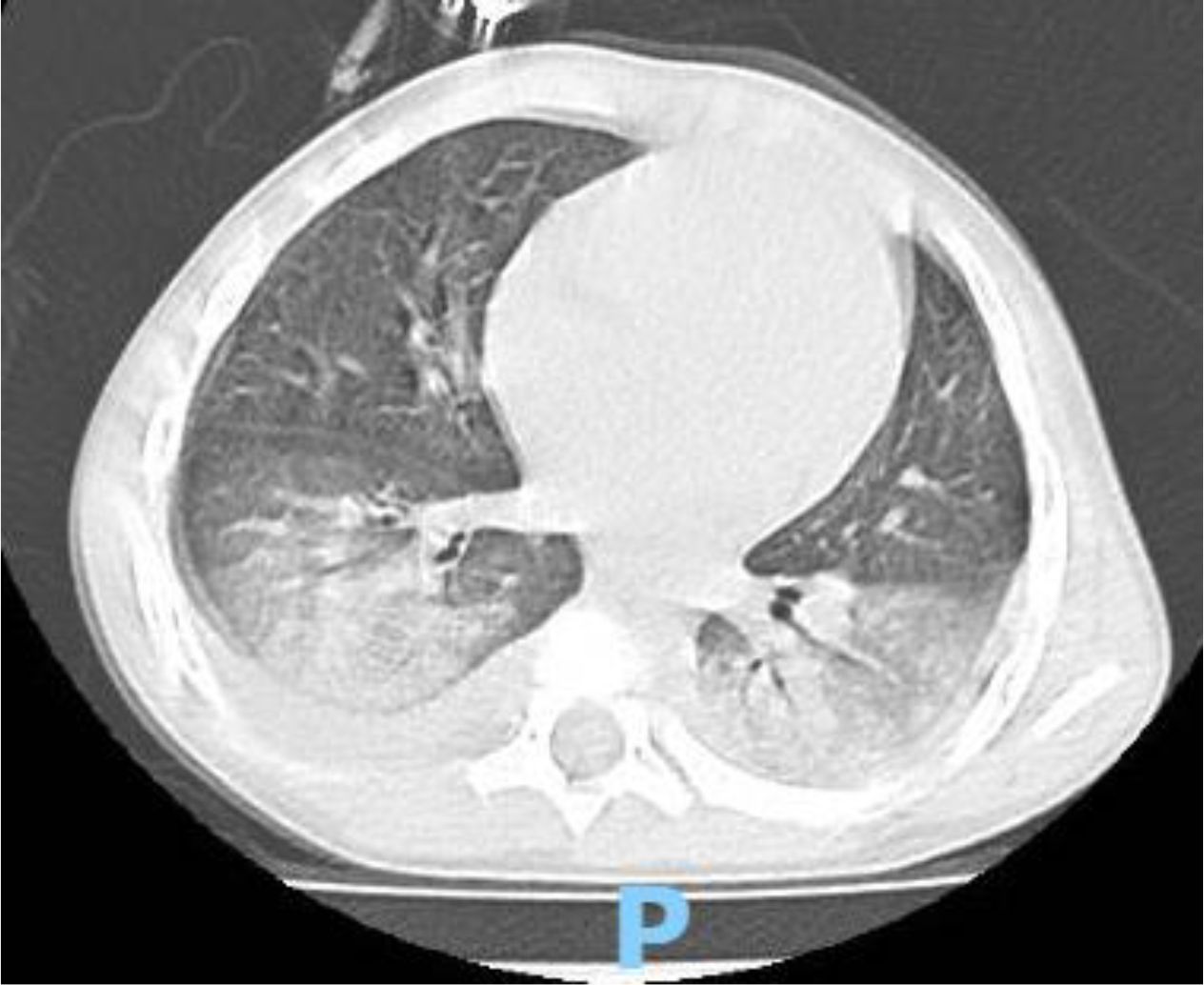

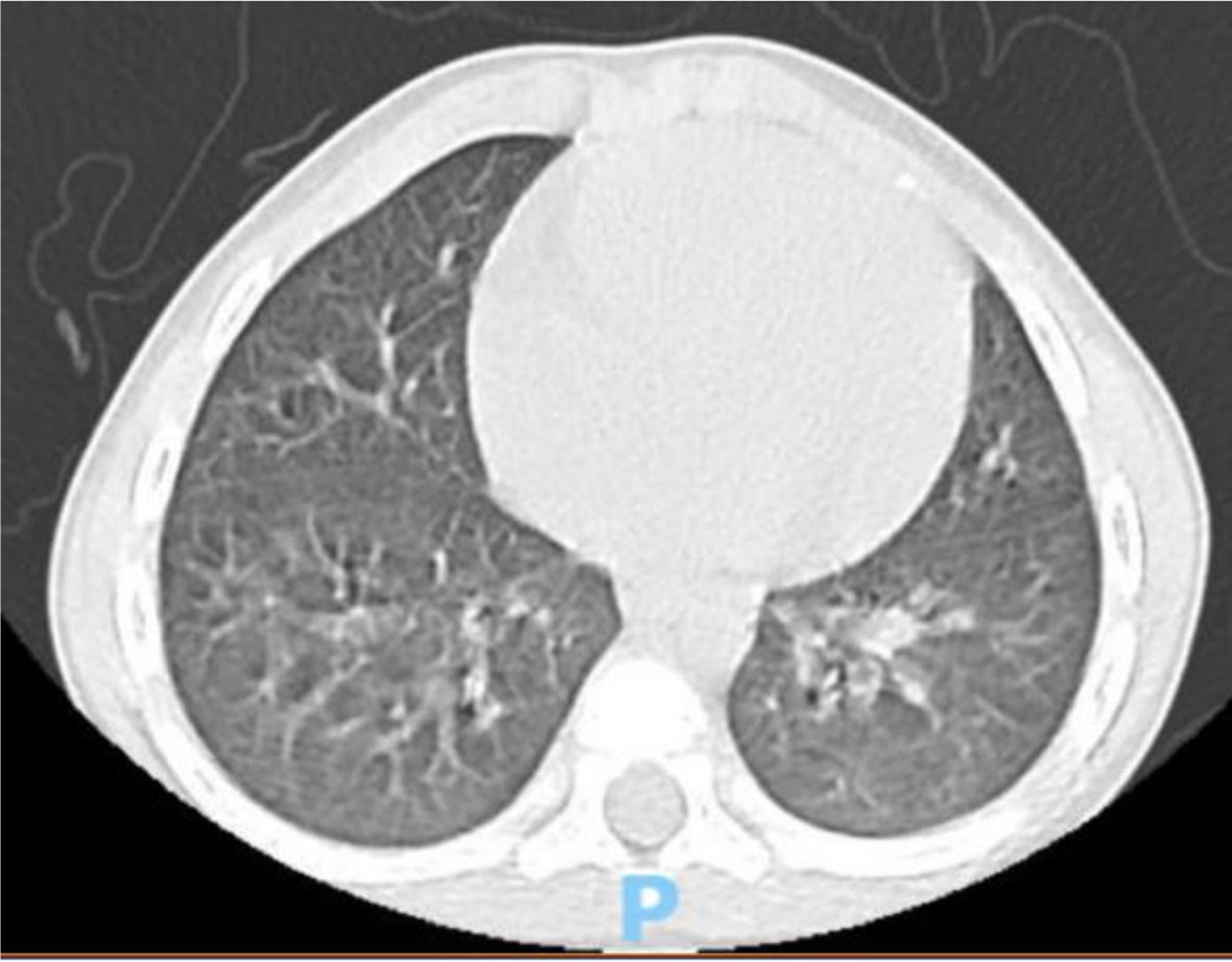

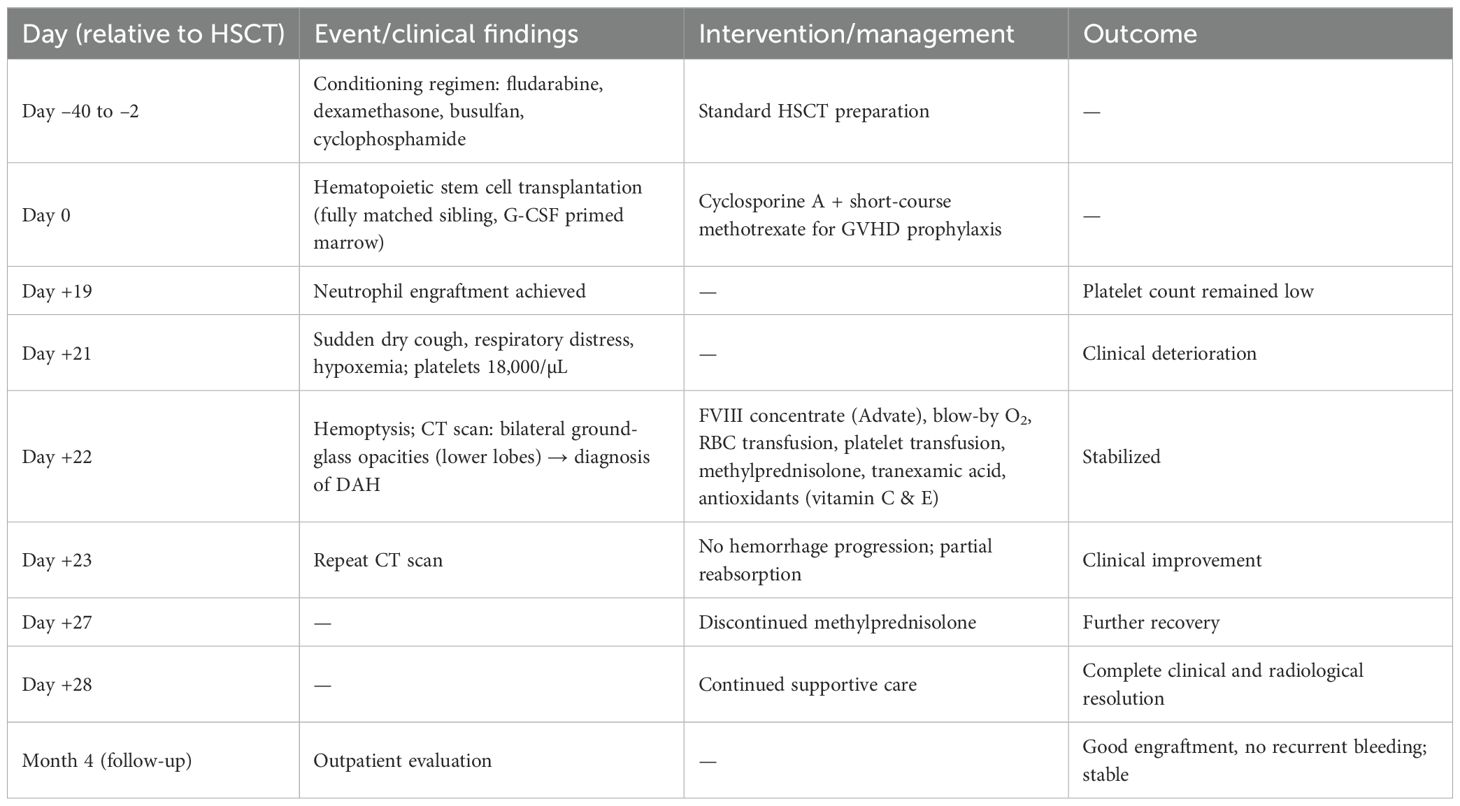

A 4 year-old male was diagnosed with HbE/Beta-thalassemia at age 2 years, and had received monthly red blood cell transfusions since. He was found to have a fully matched sibling and was scheduled for HSCT. At pre-transplant evaluation he was found to have mild hemophilia A, with no history of bleeding, and borderline low factor VIII levels discovered because of prolonged PTT at routine pre-anesthesia workup. His baseline FVIII was in the 10-20% range. He had received FVIII supplementation with PTT normalization and 28% FVIII levels. HSCT preparation consisted of fludarabine total dose 200 mg/m2, and dexamethasone total dose 125 mg/m2 on days -40 to -36, fludarabine total dose 180 mg/m2 on days -11 to -6, busulfan oral total dose 14 mg/kg from day -9 to -6, cyclophosphamide total dose 200 mg/kg from day -5 to -2. The graft source was G-CSF-primed marrow, and rejection/graft vs. host disease prophylaxis consisted of cyclosporin A and short course methotrexate. Neutrophil engraftment occurred on day +19. On day 21st post-BMT, while platelets were 18.000/µL and had received the last platelet transfusion 3 days before, he developed dry cough, respiratory distress, and hypoxemia, followed one day later by hemoptysis. He underwent a lung CT scan and found to have interstitial lung disease with areas of ground glass bilaterally, mainly in the lower lobes (Figures 1, 2). FVIII was 28%. He was diagnosed with DAH and was treated with additional FVIII concentrate (Advate), blow-by oxygen supplementation, red blood cells transfusion, platelet transfusion, methylprednisolone, tranexamic acid, and antioxidants (vitamin C and E). A chest CT repeated the following day should no hemorrhage progression and partial reabsorption of the bleeding (Figure 3). Methylprednisolone therapy was discontinued. The child had a complete clinical and radiological resolution in 6 days. (Figure 4). He had good engraftment and otherwise uneventful post-transplant course with a 4-month follow-up at the time of this report (Table 1).

Discussion

DAH is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) (15). This case report highlights a unique presentation of DAH in a pediatric patient with mild hemophilia A, which, to our knowledge, has not been previously documented. DAH typically manifests within the early post-transplant period, coinciding with thrombocytopenia, immune dysregulation, and inflammatory responses (11). The interplay between these factors can compromise alveolar-capillary integrity, leading to hemorrhage. Some studies have suggested that stem cell source and conditioning regimens containing total body irradiation are associated with a higher risk of DAH. The use of stem cells from the umbilical cord was associated with a two-fold higher rate of DAH than stem cells from peripheral blood or bone marrow (5, 16). For this case, a conditioning regimen with busulfan, cyclophosphamide, fludarabine, and dexamethasone was employed. Busulfan may contribute to lung injury but given the prompt resolution in our case it seems unlikely that busulfan toxicity played a role (17). Severe thrombocytopenia is a universal event after standard intensity conditioning, but DAH is quite rare, suggesting additional predisposing factors such as underlying coagulopathies may play a role. In this case, the child had mild asymptomatic hemophilia A, characterized by low baseline FVIII levels (10-20%), which may have acted as a co-factor exacerbating the bleeding tendency and DAH (13). The findings underscore the importance of recognizing coagulopathy as a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of DAH post-transplantation. Regarding the diagnosis, the patient’s presentation on day 21 post-BMT with hemoptysis and radiological findings of ground-glass opacities bilaterally aligns with the typical imaging characteristics of DAH. Although a bronchoalveolar lavage was not done to confirm the presence of blood in the alveoli, the diagnosis was based on clinical and radiologic findings. Treatment of DAH remains a significant challenge despite advancements in transplantation medicines. Approaches often include high-dose corticosteroids, adjustments to immunosuppressive therapy, and supportive measures (4). According to Haider, supportive care may also include platelet transfusion, procoagulant therapies (19). Recently, in order to prevent high-dose steroid exposure and improve survival rates, some novel therapies were investigated. Kalee et al. suggested inhaled and local hemostatic therapies with some preliminary suggestion of efficacy and safety (18). Voigt recommended to use recombinant activated factor VIIa (rFVIIa) in addition to standard therapy (7).

In our case, prompt intervention, including FVIII concentrate administration (Advate, recombinant FVIII, used to maintain FVIII levels > 60%), blow-by oxygen supplementation, supportive care (red blood cells and platelet transfusion), corticosteroid, tranexamic acid, and antioxidants (oral vitamin C and E), led to a rapid resolution of symptoms and radiological abnormalities. Maintaining FVIII levels > 60% with Advate, together with platelet transfusion when counts fell below 20.000/µL, prevented recurrent bleeding. Pastores et al. suggested keeping platelet counts > 50.000/µL in similar DAH cases post-transplant (7). This highlights the importance of early diagnosis and tailored management in improving outcomes.

In fact, the true prevalence of mild and asymptomatic FVIII deficiency is not known since many patients go undiagnosed, particularly in Asia (20), and the possibility of this condition underlying DAH should be kept in mind, particularly because it is a highly treatable cause, presumably with a good prognosis. While FVIII supplementation normalized PTT and improved FVIII levels, the residual coagulopathy may have predisposed the patient to bleeding complications in the presence of severe thrombocytopenia. This finding suggests that higher FVIII levels (>30-40%) might be required to mitigate the risk of DAH in patients with hemophilia A undergoing HSCT.

Conclusion

This case highlights the rare occurrence of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) in a pediatric patient with mild hemophilia A following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Routine evaluation of FVIII levels should be considered for male children developing DAH after HSCT.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

HN: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization, Software, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – original draft, Validation, Formal Analysis, Project administration. LF: Data curation, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation, Software. SB: Writing – review & editing. HL: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. NH: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology. TD: Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Corso S, Vukelja SJ, Wiener D, and Baker W. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage following autologous bone marrow infusion. Bone Marrow Transplant. (1993) 12:301–3.

2. Schmidt-Wolf I, Schwerdtfeger R, Schwella N, Gallardo J, Schmid H. J, Huhn D, et al. Diffuse pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Ann Hematol. (1993) 67:139–41. doi: 10.1007/BF01701739

3. Afessa B, Tefferi A, Litzow MR, and Peters SG. Outcome of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2002) 166:1364–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-792OC

4. Loecher AM, West K, Quinn TD, and Defayette AA. Management of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in the hematopoietic stem cell transplantation population: A systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. (2021) 41:943–52. doi: 10.1002/phar.2630

5. Majhail NS, Parks K, Defor TE, and Weisdort DJ. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and infection-associated alveolar hemorrhage following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: related and high-risk clinical syndromes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2006) 12:1038–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.06.002

6. Wu T, Liu QF, Zhang Y, Fan ZP, Xu D, Sun J, et al. The incidence and risk factors of late-onset non-infectious pulmonary complications after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. ]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. (2010) 31:249–52.

7. Pastores SM, Papadopoulos E, Voigt L, and Halpern NA. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: treatment with recombinant factor VIIa. Chest. (2003) 124:2400–3. doi: 10.1016/s0012-3692(15)31709-8

8. Yen KT, Lee AS, Krowka MJ, and Burger CD. Pulmonary complications in bone marrow transplantation: a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Chest Med. (2004) 25:189–201. doi: 10.1016/S0272-5231(03)00121-7

9. Wanko SO, Broadwater G, Folz RJ, and Chao NJ. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage: retrospective review of clinical outcome in allogeneic transplant recipients treated with aminocaproic acid. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2006) 12:949–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.05.012

10. Fan K, Hurley C, McNeil MJ, Agulnik A, Federico S, Qudeimat A, et al. Case report: management approach and use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for diffuse alveolar hemorrhage after pediatric hematopoietic cell transplant. Front Pediatr. (2020) 8:587601. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.587601

11. Fan K, McArthur J, Morrison RR, and Ghafoor S. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front Oncol. (2020) 10:1757. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01757

12. Robbins RA, Linder J, Stahl MG, and Thompson AB. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in autologous bone marrow transplant recipients. Am J Med. (1989) 87:511–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(89)80606-0

13. Kasai H, Terada J, Hoshi H, Urushibara T, Kato F, Nishimura R, et al. Repeated diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in a patient with hemophilia B. Intern Med. (2017) 56:425–8. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.56.7614

14. Witte RJ, Gurney JW, Robbins RA, Linder J, Rennard SI, Arneson M, et al. Diffuse pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage after bone marrow transplantation: radiographic findings in 39 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. (1991) 157:461–4. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.3.1872226

15. Hicks K, Peng D, and Gajewski JL. Treatment of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage after allogeneic bone marrow transplant with recombinant factor VIIa. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2002) 30:975–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703731

16. Keklik F, Alrawi EB, Cao Q, Bejanyan N, Rashidi A, Lazayan A, et al. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage is most often fatal and is affected by graft source, conditioning regimen toxicity, and engraftment kinetics. Haematologica. (2018) 103:2109–15. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.189134

17. Castelli S, Thorwarth A, van Schewick C, Wendt A, Astrahantseff K, Szymansky A, et al. Management of busulfan-induced lung injury in pediatric patients with high-risk neuroblastoma. J Clin Med. (2024) 13. doi: 10.3390/jcm13195995

18. Kalee GL, Emily D, Sonata J, and Christopher D. Managing diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in pediatric HSCT with inhaled and intrabronchial therapy: A case series of targeted hemostatic intervention. Transplant Cell Ther. (2025) 31:S133–57.

19. Haider S, Durairajan N, and Soubani AO. Noninfectious pulmonary complications of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur Respir Rev. (2020) 29. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0119-2019

Keywords: diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, hematopoietic stem cells transplantation, child, hemophilia, thalassemia

Citation: Nguyen HTK, Faulkner L, Bui SBB, Lederman HM, Ho NTT and Dang TT (2025) Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in a child with mild hemophilia A who underwent bone marrow transplantation for thalassemia: a case report. Front. Hematol. 4:1657903. doi: 10.3389/frhem.2025.1657903

Received: 02 July 2025; Accepted: 09 September 2025;

Published: 30 September 2025.

Edited by:

Marcus O. Muench, Vitalant Research Institute, United StatesReviewed by:

Vanya Icheva, University Children’s Hospital Tübingen, GermanyMaria Benkhadra, National Center for Cancer Care and Research, Qatar

Kimberly Uchida, University of Utah Department of Pediatrics - Division of Pediatric Critical Care, United States

Copyright © 2025 Nguyen, Faulkner, Bui, Lederman, Ho and Dang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hoa Thi Kim Nguyen, a2ltaG9hLmZtaUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Hoa Thi Kim Nguyen

Hoa Thi Kim Nguyen Lawrence Faulkner

Lawrence Faulkner Son Binh Bao Bui3

Son Binh Bao Bui3