- 1Tasmanian School of Medicine, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia

- 2Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia

Introduction: This systematic review evaluates CRISPR–Cas9 mediated gene therapy for inherited bone marrow failure syndromes, a heterogeneous group of rare inherited disorders characterised by cytopenia, cancer predisposition, and multi-organ involvement, for which supportive care and allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation provide cures for some but remain imperfect, donor-limited, and associated with significant morbidity. The objective of this review is to evaluate the current state of CRISPR–Cas9 mediated gene therapy in inherited bone marrow failure syndromes, with a focus on how this technology has been applied in experimental models to correct pathogenic mutations and restore haematopoietic function.

Methods: We searched PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar for studies combining inherited bone marrow failure syndromes with gene editing, prime editing, base editing, or CRISPR–Cas9.

Results: Of 876 records screened, 18 met the inclusion criteria. Fanconi anaemia predominated (n=8), with additional work in severe congenital neutropenia (n=3), Shwachman–Diamond syndrome (n=2), Diamond–Blackfan anaemia (n=2), and single studies in dyskeratosis congenita, congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia, and myelodysplastic syndrome/ acute myeloid leukaemia predisposition.

Discussion: Overall, CRISPR–Cas9 has demonstrated feasibility for ex vivo correction in inherited bone marrow failure syndromes; however, future clinical adaptation will depend on overcoming key hurdles, such as careful assessment of off-target effects and establishing regulatory pathways that enable access for patients with rare diseases, thereby bridging the gap between preclinical and therapeutic application.

Introduction

Inherited bone marrow failure syndromes (iBMFS) are a set of rare genetic disorders characterised by significant cytopenia due to impaired haematopoiesis in the bone marrow. Improvements in whole-genome sequencing have shown that impaired haematopoiesis can occur due to mutations in more than 50 genes, most of which are involved in telomere maintenance, DNA repair, or ribosome biogenesis (1). Ultimately, these mutations lead to increased susceptibility to infection due to reduced white blood cell counts and an increased risk of anaemia or bleeding due to insufficient platelet production (2). The more common iBMFS include Fanconi anaemia, dyskeratosis congenita, Shwachman–Diamond syndrome, reticular dysgenesis, severe congenital neutropenia, and Diamond–Blackfan anaemia (3). This review investigates how widespread the approaches of CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing are in the context of iBMFS.

The current standard treatment options for iBMFS are tailored to the specific disease group and cover a wide range of disease aspects. These include preventing and managing bacterial infections through antibiotics; relieving symptoms such as anaemia by blood transfusions; using immunosuppressants to suppress the immune system; using synthetic steroid androgens such as danazol or oxymetholone to promote healthy haematopoiesis; using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) therapy to promote neutrophil differentiation and survival; and measures that are curative for the haematopoietic compartment, such as haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) from an HLA-compatible donor (4–6). Whilst the only available curative treatment is HSCT, some patients are excluded due to a lack of an HLA-compatible donor or due to comorbidities (5). The cost of transplantation limits its availability in many parts of the world, and the prolonged process of finding a suitable donor adversely affects individuals with severe conditions (7, 8). Stem cell transplantation also carries limitations such as graft-versus-host disease, in which the transplanted immune cells, such as T cells, recognise the host body as foreign and attack host tissues, a complication that can be fatal (9). To avoid this, patients who undergo stem cell transplants often rely on immunosuppressive medication (10). iBMFS frequently affect non-haematopoietic organs (e.g., the endocrine system, liver, gastrointestinal tract, and lungs), and patients have a higher probability of developing leukaemia and non-haematological cancers, which are not altered by stem cell transplantation (5). HSCT has been transformative for many patients with iBMFS, offering the potential for a haematopoietic cure (11). Recent advances in reduced conditioning regimens and donor matching have reduced morbidity and are expected to decrease secondary malignancies that develop later in life, particularly in patients with defects in DNA-damage repair pathways, such as Fanconi anaemia (12). However, for those without an HLA-matched donor, the complexities of iBMFS management and the potential adverse events of HSCT underline the potential clinical benefit of genome editing. Because the patient’s own cells can be modified in these therapies, they have the potential to provide superior clinical outcomes, particularly for patients without an HLA-matched donor.

Recent revolutionary advancements in gene editing technologies offer potential solutions for treating many inherited genetic mutations (13). The ease of isolation and manipulation of haematopoietic stem cells makes diseases of the haematopoietic system particularly well suited to these technologies. A field currently undergoing an explosion in interest is the use of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR-Cas9) gene editing. CRISPR gene editing relies on a guide sequence which, when combined with an enzyme called Cas9, can cut the DNA at a targeted site (14). CRISPR-Cas9 has been established as a powerful and effective tool for genetic engineering and outperforms previously used technologies like zinc finger nucleases (15) and Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (16). Although the first CRISPR-Cas9 adaptive immune system was discovered more than three decades ago in Escherichia coli (17), it took 20 years for scientists to effectively harness the system for effective gene editing, and since then the technology has become wide spread fulfilling the long-standing goal of a precise and efficient method of gene editing in living cells (14, 18).

The first generation CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two components, the Cas9 nuclease enzyme that cuts the DNA at the targeted site and the single guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs the Cas9 to the specific target genomic location through complimentary base pairing with the target DNA sequence (14). Once the Cas9-sgRNA complex forms, it must first recognise a short-conserved DNA sequence motif called a protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) and bind to the target sequence, it then induces a DSB at a site 3 base pairs upstream to the PAM site (19), which activates the cell’s natural DNA repair pathways (20). The two primary mechanisms for repairing these breaks are non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR), each of which leads to different outcome in terms of the precision and nature of the genetic modification introduced (21).

Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is the predominant repair pathway in most cell types because it is activated throughout the cell cycle, particularly in the G1 phase (22). NHEJ repairs the double-strand break (DSB) by directly ligating the broken DNA ends without the need for a homologous template, making it a rapid but error-prone process (23). During NHEJ, the cell’s repair machinery may introduce small insertions or deletions (indels) at the site of the break, which can disrupt the reading frame of a gene and lead to loss-of-function mutations (23). Due to the frequency of indels in NHEJ, this pathway is often exploited in gene knockout experiments, where the goal is to inactivate a gene and study its function, model genetic diseases, or screen for therapeutic targets (24).

Homology-directed repair (HDR) provides a more precise mechanism for editing DNA by utilising a homologous donor template that guides the repair process. HDR is typically active only during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, when a sister chromatid is available as a template for repair, making it largely restricted to mitotic cells (25). However, in HDR-mediated repair, a synthetic donor template—carrying the desired sequence changes flanked by regions of homology to the DNA surrounding the DSB—is introduced into the cell along with the CRISPR–Cas9 components (23). The cellular machinery then uses the homologous sequences on the donor template to accurately repair the break, allowing precise gene modifications such as point mutations or gene insertions or deletions (23, 26). HDR offers significant advantages for therapeutic genome editing that aims to correct pathogenic mutations in monogenic disorders, such as sickle cell disease (27). By introducing specific nucleotide changes, HDR can restore the normal function of a mutated gene, offering a potential cure for certain genetic diseases (27).

However, significant challenges remain with HDR-based gene editing. The efficiency of HDR is generally much lower than that of NHEJ, primarily because HDR is restricted to specific phases of the cell cycle (28). Additionally, delivering the donor template in a form accessible to the repair machinery is technically challenging, and achieving high HDR efficiency often requires optimisation of several factors, including donor template design, the length of homology arms, and the timing of CRISPR–Cas9 delivery (23).

Any use of CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing increases genome instability due to the DSBs created by the nuclease, with reports of chromothripsis and DNA-damage-induced apoptosis resulting from the generation of DSBs (29). This is particularly problematic in the context of Fanconi anaemia, where homology-directed repair is compromised (30). This, coupled with off-target effects, limits the clinical applicability of first-generation CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing.

In summary, although CRISPR–Cas9 with or without templated repair offers a means of modifying the genome, its limitations have driven researchers to investigate more accurate tools with higher editing efficiency and reduced cellular damage as potential therapeutics for inherited diseases. Two advanced technologies developed from CRISPR–Cas9—base editing and prime editing—use different mechanisms to install programmable gene edits and have demonstrated higher accuracy compared with the traditional CRISPR–Cas9 system (31, 32). While the traditional CRISPR–Cas9 approach relies on creating DSBs in DNA, base editing and prime editing modify genetic sequences without introducing DSBs, which has significant implications for reducing the risk of unwanted mutations and enhancing the efficiency of gene editing applications in both research and therapeutic contexts (33, 34).

Base editing (BE) is a second-generation gene editing technique that enables the conversion of one DNA base pair to another, thus enabling single nucleotide changes (35). It consists of a nickase Cas9 protein fused to a deaminase enzyme that chemically modifies a specific base. The two main types of base editors, Cytosine base editors (CBEs) and Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) convert Cytosine to Thymine or Adenine to Guanine respectively. CBEs deaminate Cytosine into Uracil, which is then recognised and repaired by the cell’s repair mechanism as Thymine. Adenine Base Editors (ABEs), convert Adenine to Inosine which is interpreted as Guanine during DNA replication or repair. This is achieved in concert with a mutated version of Cas9, dCas9 that binds to DNA, but does not cut the DNA backbone (35). ABEs exhibit lower off target activity compared to CBEs, likely due to the unique characteristics of adenosine deaminase and its specificity for DNA (31). CBEs have shown high efficiency in correcting genetic mutations caused by G-C base pairs, which are abundant in many genetic disorders (33). BE can be used to correct single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which are responsible for a large set of genetic diseases (36). Regardless of its capability, BE faces certain limitations and technical challenges. One of the main concerns is off-target editing, where the base editor inadvertently modifies sequences other than the intended target, which can arise from unintended deaminase activity within the editing window of the intended target site, or at sites with partial sequence homology (37).

Prime editing is a more advanced and recent approach in gene editing that can correct a broader spectrum of mutations. Prime editing employs a fusion protein consisting of a Cas9 nickase, which introduces a single-strand break in the DNA, and a reverse transcriptase enzyme capable of synthesising new DNA based on an RNA template. This fusion is guided to the target site by a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA), which serves a dual role: it directs the Cas9 nickase to the specific genomic location and carries a template specifying the desired DNA edit (32). The pegRNA includes a spacer sequence that binds to the target DNA, a primer-binding site that allows the reverse transcriptase to initiate DNA synthesis, and a sequence encoding the intended modification. This versatile approach enables prime editing to perform all possible types of substitutions, small insertions, deletions, and even combinations of these changes, surpassing the capabilities of conventional CRISPR–Cas9 systems and base editing techniques (32). Prime editing (PE) is designed to increase the efficiency and precision of incorporated edits and has shown significantly high efficiency across various cell types and organisms, demonstrating its broad applicability (38). This makes prime editing an attractive strategy for therapeutic gene editing applications requiring precise modifications. Despite its advantages, PE still faces technical limitations, with efficiency depending on factors such as cell type, target site, and sequence context. While PE significantly reduces off-target effects compared with traditional CRISPR–Cas9, unintended edits can still occur, including indels at nick sites (39) particularly when the pegRNA has partial homology to other genomic regions. Additionally, delivering PE components into target cells and tissues poses limitations, as PE requires delivery of a large payload, and each delivery approach has specific constraints regarding efficiency, tissue specificity, immunogenicity, and potential toxicity (40). As PE continues to evolve, its efficiency and scope are expected to improve (41). The field now looks to the latest research to determine whether therapeutic levels of editing can be achieved without unintended edits. This systematic review collects and evaluates recent findings to understand where the field is moving and how effective these technologies are likely to be.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

The systematic survey was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines to identify publications relevant to the review’s scope. First, the authors conducted a broad literature search on PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar using the technical terms “CRISPR Cas9”, “base editing”, “prime editing”, and “gene editing” to gather information about studies employing these techniques. The search terms were then narrowed to focus specifically on inherited bone marrow failure syndromes (iBMFS) and were applied on the same platforms using the combinations “inherited bone marrow failure syndromes” and “CRISPR-Cas9”, “inherited bone marrow failure syndromes” and “base editing”, “inherited bone marrow failure syndromes” and “prime editing”, and “inherited bone marrow failure syndromes” and “gene editing”, with no filters applied at this stage. Whilst there is terminological diversity in the characterisation of these disorders, a pilot search using alternative terminology returned no additional relevant primary studies.

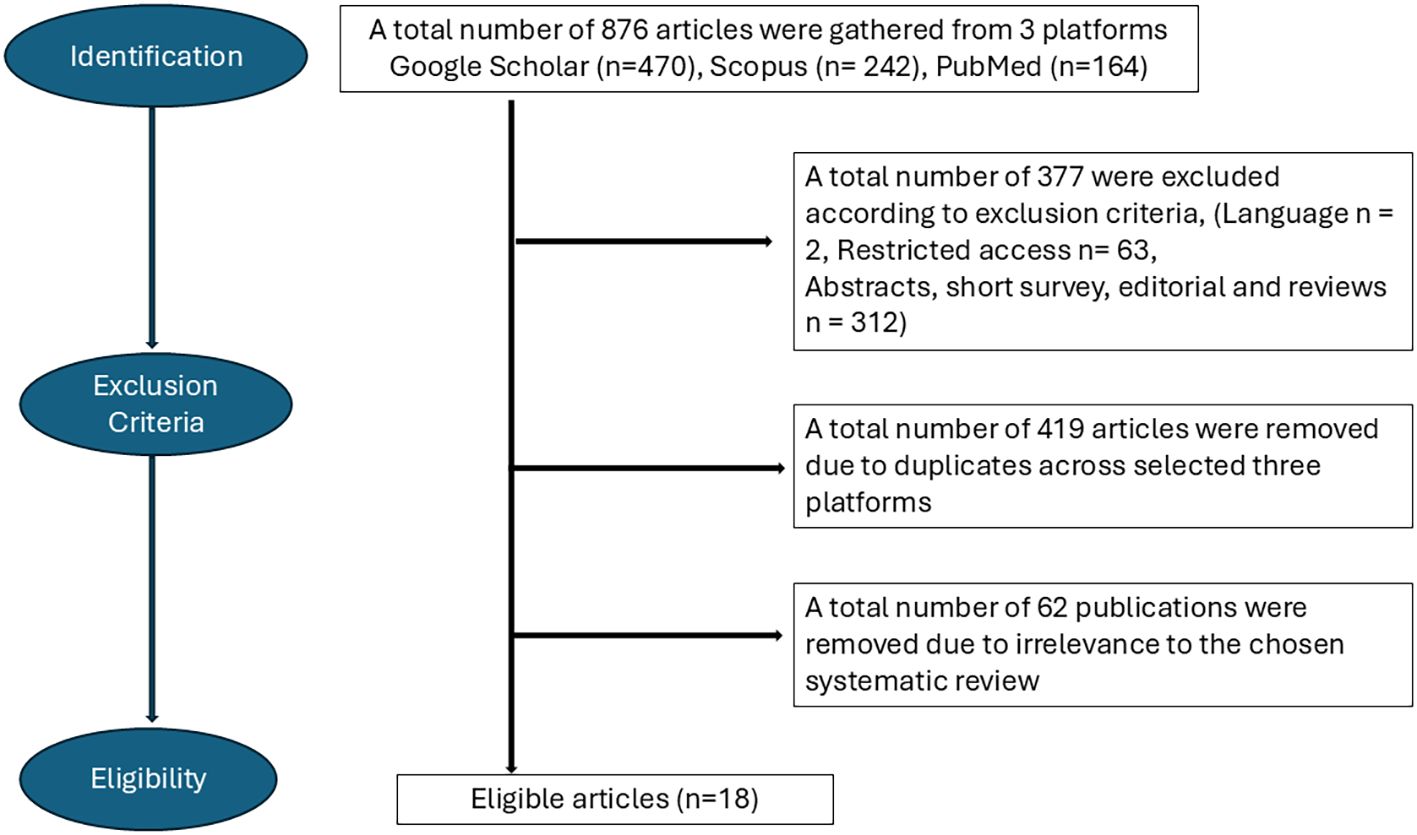

A total of 876 sources were initially gathered. After applying exclusion criteria—removal of duplicates, restricted-access articles, articles in languages other than English, non-primary papers, and irrelevant content—18 papers meeting the inclusion criteria were selected for review. The workflow is shown in Figure 1. Inclusion criteria required that publications fell within the technical scope of the search terms, were published in English, and were openly accessible. The search timeframe included all studies published up to 31/10/2024.

Figure 1. Flowchart depicting the process of selecting eligible articles for the study according to the PRISMA guidelines.

Results and discussion

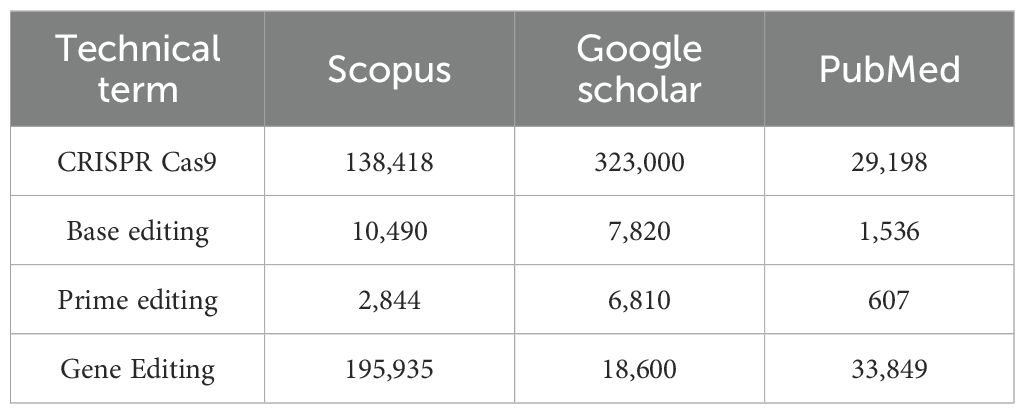

The initial broad search returned a total of 1,016,107 articles across the three platforms (PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar), as shown in Table 1. This included 323,000 articles on CRISPR-Cas9 in Google Scholar alone, highlighting the intense global research focus on CRISPR-Cas9 and the potential future applications of this technology.

Table 1. Results of the initial broad search conducted on overall studies using CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing techniques.

In contrast, when the platforms were queried specifically for combinations of these terms with “inherited bone marrow failure syndromes”, only 876 sources were retrieved, and just 18 met the inclusion criteria of this review. This substantial difference underscores that, whilst genome editing technologies have been extensively studied in general, their translation into iBMFS remains at an early stage. Current literature shows that despite the preclinical and clinical validation of CRISPR-Cas9 therapies in other haematological diseases, applications of CRISPR-Cas9 techniques to iBMFS remain largely unexplored.

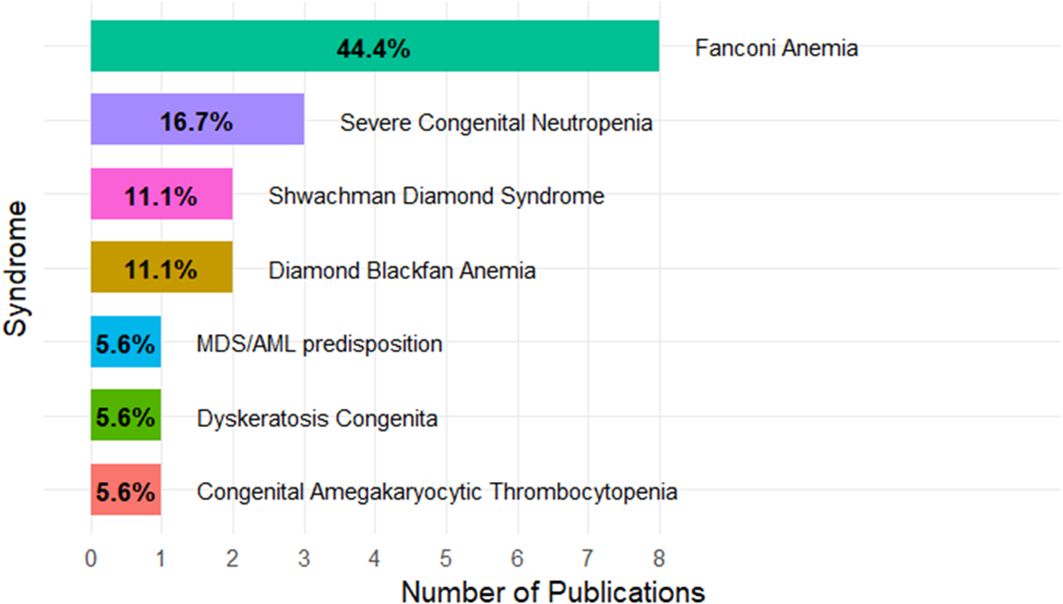

The selected publications across iBMFS are summarised in Figure 2. Of the 18 included studies, the largest number were in Fanconi anaemia (n = 8), followed by severe congenital neutropenia (n = 3), Shwachman–Diamond syndrome (n = 2), and Diamond–Blackfan anaemia (n = 2). Single studies were identified for dyskeratosis congenita, congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia, and MDS/AML predisposition (n = 1 each). Across all studies, 10 focused on correcting the underlying pathogenic mutations, and 8 focused on disease modelling—for example, generating isogenic stem cell or animal models to study disease pathogenesis.

Figure 2. Distribution of publications across inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. The box plot is showing the percentage of the papers included in the review.

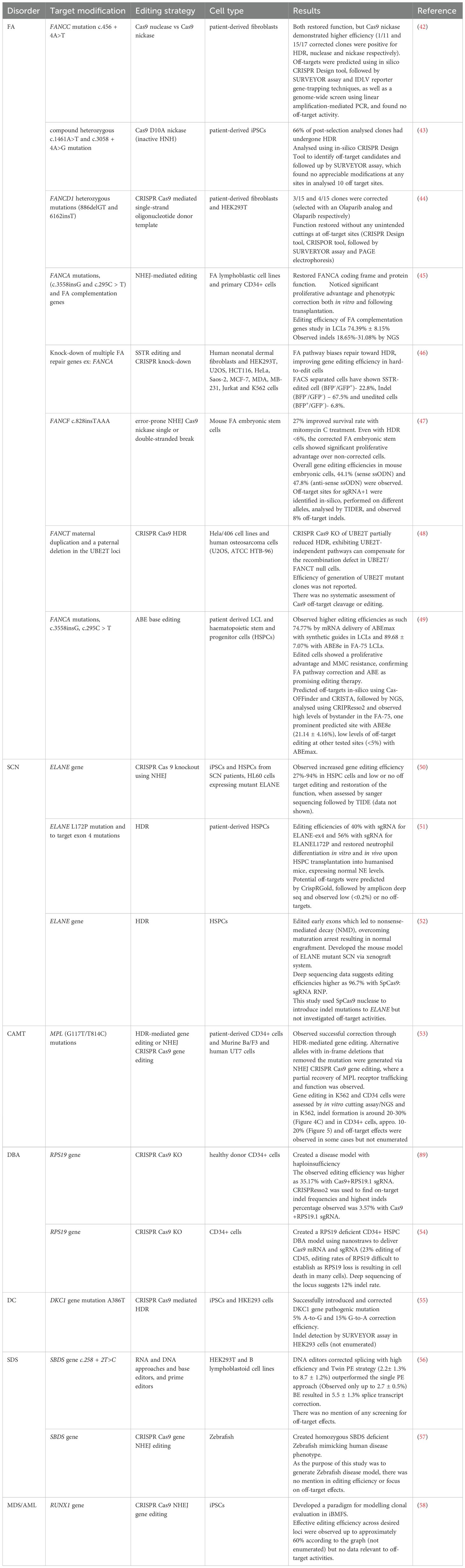

Of the 18 selected studies, 16 relied on conventional CRISPR-Cas9 systems (Table 2). Among these, seven studies adopted HDR-based approaches, reflecting a preference for precise gene correction or targeted knock-in strategies, and seven applied an NHEJ strategy, underscoring its efficiency in generating knockouts or indel-based disruptions. Two studies applied both techniques. Only one recent study employed base editing, while one study applied both prime editing and base editing using engineered RNA and DNA strategies for versatile and precise modification. Taken together, these findings underscore the dominance of conventional CRISPR-Cas9 approaches (HDR and NHEJ). However, the recent inclusion of base editing and prime editing signals a growing shift towards more refined and powerful strategies in genome engineering.

Table 2. Overview of studies using CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing in inherited bone marrow failure syndromes.

Inherited bone marrow failure syndrome and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing

CRISPR-Cas9 has demonstrated potential as an effective therapeutic strategy, with Casgevy now approved for clinical use and clinical trials underway for several CRISPR therapeutics (e.g., BEAM101, Prime Medicine) medicine) (59, 60). When several gene editing techniques are available as potential approaches, factors such as effectiveness, precision, toxicity, and safety—particularly the avoidance of unwanted gene alterations—should be compared to determine the most suitable clinical approach (61). These approaches can be trialled in research laboratories, providing recommendations on optimal strategies for future therapeutic development.

Gene editing techniques are being developed in both in vivo and ex vivo formats. In vivo therapy delivers genetic material directly to the patient’s target organ, mainly using viral vectors (62). Whilst this approach enables direct delivery and often higher editing efficiency, immunogenicity concerns are significant and require long-term assessment (63). Ex vivo therapy involves collecting cells from patients, correcting mutations in these cells, and reintroducing the modified cells back into the patient (64). In the context of iBMFS gene therapy, the harvested haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are typically enriched for CD34+ cells, which constitute approximately 1% of bone marrow and are essential for long-term engraftment. For effective gene therapy, genetic modifications must be permanent and passed on to daughter cells during HSC division, maintaining progenitor capacity and avoiding adverse effects. Ex vivo approaches offer lower toxicity compared with in vivo delivery; however, regulatory hurdles and high costs remain major barriers to clinical translation (65).

Fanconi anaemia

Out of the 18 sources relevant to this literature search, eight studies were related to Fanconi anaemia. Of these eight, three applied HDR-based strategies and used patient-derived fibroblasts, (42, 44) iPSCs (43), and Hela/406 cells and human osteosarcoma cells (U2OS, ATCC HTB-96) (48), showing successful correction of FANCC, FANCI, FANCD1, and FANCT mutations. Whilst the DNA damage repair pathway is known to be defective in Fanconi anaemia cells (particularly in interstrand crosslink repair), the gene editing studies outlined in this review show that HDR remains a potential tool in this context. It has been suggested that this may be due, in part, to alternative pathways operating in cells deficient in canonical double-strand break repair (66). Whilst these papers demonstrate feasibility, prime editing and base editing—which do not rely on double-strand break repair—are likely to repair FA mutations with greater efficiency.

The first published study in Fanconi anaemia using CRISPR Cas9 gene editing used both NHEJ and HDR in patient-derived fibroblasts and HEK293T cells (42). In addition, a mechanistic study using fibroblasts and multiple immortalised human cell lines applied a single-strand template repair (SSTR) approach, a form of HDR (46). NHEJ-mediated correction of FA mutations has also been demonstrated in two studies using multiple models, including FA lymphoblastic cells, patient-derived CD34+ haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), and mouse embryonic stem cells (45, 47). Base editing has been assessed in only one study, using patient-derived lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) and HSPCs (49).

Fanconi anaemia (FA) is the most prevalent iBMFS, occurring in approximately one out of every 100,000 births (67). Fanconi anaemia is caused by mutations in genes involved in the DNA repair system, ultimately leading to defective interstrand crosslink repair, chromosomal instability, and cellular death (68). To date, mutations in at least 22 genes have been identified, with the most common being FANCA, FANCC, and FANCD (69). Patients with FA are characterised by decreased production of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets, alongside physical abnormalities such as kidney problems and heart defects, and an increased risk of cancers such as acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) (70). FA pathway proteins play a central role in repairing DNA interstrand crosslinks and maintaining genomic integrity through HDR of DNA DSBs. Core FANC proteins coordinate the monoubiquitination of FANCD2–FANCI, which facilitates recruitment of downstream effectors and promotes error-free HDR and stabilisation of replication forks (71). In the absence of a functional FA pathway, cells exhibit impaired HDR capacity and rely more heavily on error-prone NHEJ, contributing to chromosomal instability and mutagenic signatures in HSPCs. This is thought to be a major contributor to the bone marrow failure observed in FA (45, 72).

The first attempt at gene editing in FA patients using CRISPR-Cas9 was published in 2015. Correction of the FANCC mutation c.456 + 4A>T in patient-derived fibroblasts was compared between Cas9 nuclease and Cas9 nickase. Gene correction was observed in both, but the Cas9 nickase demonstrated higher HDR activity and reduced NHEJ compared with the nuclease (42). Later, the same research group used FANCI patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to correct compound heterozygous mutations (c.1461A>T and c.3058 + 4A>G) using Cas9 D10A nickase with an inactive HNH domain, which nicks only a single DNA strand and is associated with higher HDR and reduced off-target effects. Furthermore, they analysed 10 off-target candidates contained within genes and did not observe appreciable modifications at any sites. This data supports the notion that iPSCs derived from FANCI can be modified and used as templates for therapeutic cell development (43), whilst iPSC therapies are one potential avenue for treatment of haematopoietic diseases, the modification of HSCs is a far simpler workflow, and more likely to ultimately result in regulatory approval.

Another study using Cas9 nuclease was performed by Kramarzova et al., who pursued a different strategy, demonstrating the successful correction of a compound heterozygous mutation (886delGT and 6162insT) in FANCD1 primary patient fibroblasts using a CRISPR Cas9-mediated single-strand oligonucleotide donor template. The function of FANCD1 was restored without observing any unintended editing at off-target sites. A pure population of modified cells was obtained using inhibitors of poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP), which suggests the possibility of survival and expansion of genome-modified HSPCs in the presence of PARPi (44).

While most studies highlighted the potential of HDR-mediated gene editing, the feasibility of NHEJ as a therapeutic alternative has been effectively demonstrated. A recent study highlighted the efficacy of NHEJ-mediated editing in restoring the coding frame of various FA complementation genes (including FA-A, FA-B, FA-C, FA-D1, and FA-D2) using compensatory insertions and deletions. This approach was tested in both FA lymphoblastic cell lines and primary CD34+ cells derived from FA patients, which exhibited a significant proliferative advantage and phenotypic correction both in vitro and following transplantation, despite its counterintuitive nature. The results suggest that NHEJ is a simple yet efficient therapeutic alternative to correct mutations across different FA complementation groups (45).

Human Cas9-mediated single-strand template repair (SSTR) requires the FA pathway, which is primarily involved in repairing interstrand crosslinks. Specifically, FANCD2 protein accumulates at Cas9-mediated DSBs during repair, suggesting it plays a direct role in regulating genome editing. One study by Richardson et al. proposed the FA pathway as a “traffic signal”, guiding repair towards templated methods instead of NHEJ. They suggest that enhancing the FA pathway could significantly improve gene editing efficiency, particularly in hard-to-edit cells, although this study was not specifically focused on iBMFS (46). Even though the fundamental DNA repair defects in FA limit gene editing possibilities, in 2019, Van de Vrugt et al. showed that effective restoration of functional FANCF through error-prone NHEJ is possible, with a 27% improved survival rate during mitomycin C (MMC) treatment. The data indicated that templated gene correction could be achieved by either a single- or double-strand break using Cas9 nickase, resulting in monoallelic gene editing and successfully avoiding off-target mutagenesis. Even though templated editing efficiencies were low (<6%), FA embryonic stem cells that had undergone gene correction showed a significant proliferative advantage compared with non-corrected cells, even in the absence of genotoxic stress (47).

One study investigated a clinical paradox. A patient carrying a FANCT mutation had normal peripheral blood counts; on further investigation it was found that this patient also had a paternal deletion in the UBE2T locus but paradoxically normal UBE2T protein levels in B-lymphoblast cells. This study was conducted to explore whether this was achieved by HDR between UBE2T and AluYa5 elements, despite HDR defects in HeLa cells. Introduction of a DSB in the model UBE2T locus in vivo induced single-strand annealing between proximal Alu elements and deletion of the intervening marker, mimicking the UBE2T duplication reversion in the FA patient. The CRISPR Cas9-dependent knockout of UBE2T partially reduced HDR, suggesting that UBE2T-independent pathways can compensate for the recombination defect in UBE2T/FANCT null cells (48).

While most approaches relied on NHEJ and HDR, one of the latest studies showed that base editors are both tolerated and efficient in correcting FA point mutations in patient-derived LCLs and HSPCs. They observed that successful ABE editing restored compound heterogenous mutations (c.2639G>A and c.3788_3790 del TCT and homozygous c.295C>T to wild-type FANCA, describing molecular and phenotypic rescue, including re-expression of the FANCA protein and enhanced cell proliferation in LCLs and HSPCs. Edited cells showed a proliferative advantage and MMC resistance, confirming FA pathway correction. Although engraftment in FA HSPCs remains untested here, in vivo studies in immunodeficient mice confirmed that base editing did not impair engraftment potential. High ABE8e activity led to unintended bystander mutations, but these did not impact FANCA function. Strategies such as RNP delivery or ABE8e variants could reduce off-target effects. Despite the FA pathway’s role in DNA repair, its absence did not interfere with ABE activity in LCLs and HSPCs, suggesting ABE as a promising gene editing therapeutic strategy in FA (49).

Severe congenital neutropenia

Severe congenital neutropenia (SCN) is one of the rare iBMFS and a life-threatening primary immunodeficiency disorder characterised by an absence or severe reduction of functional neutrophils due to genetic mutations affecting granulocyte differentiation and maturation (73). Neutrophils are a crucial part of the innate immune system, responsible for phagocytosis and the elimination of bacterial infections. The absence or severe reduction of neutrophils in affected individuals carries a high risk of recurrent bacterial infections, particularly in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. These infections can lead to complications such as sepsis, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, and enterocolitis (74).

Even though SCN is a multigene syndrome, over 60% of SCN patients have autosomal dominant mutations in the ELANE gene, which encodes neutrophil elastase (NE), a major inflammatory serine protease (75, 76). These mutations result in impaired granulocyte differentiation and maturation, leading to a deficiency in functional neutrophils (77). Mutations in the CSF3R gene, which encodes the receptor for granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), another cytokine regulating neutrophil production and function, are also associated with SCN (78). CSF3R is crucial for the differentiation, proliferation, and survival of neutrophil progenitor cells in the bone marrow. Binding of G-CSF to CSF3R triggers signalling pathways that promote the maturation and release of neutrophils into the bloodstream (79).

Unlike FA, where different approaches have been explored, SCN studies remain HDR- and NHEJ-focused so far. To date, only three publications have been reported. One study adapted NHEJ in SCN patient-derived iPSCs and HSPCs, along with HL60 cells, while the other two applied HDR approaches in patient-derived HSPCs (50–52).

Maturation arrest is a key issue in ELANE-mutation-associated SCN, where myeloid progenitors fail to produce mature neutrophils. Nasri et al. (50) proposed, for the first time, using CRISPR Cas9-mediated ELANE knockout to overcome mutations in the ELANE gene. Using iPSCs and HSPCs from SCN patients, as well as HL60 cells expressing mutant ELANE, ELANE was knocked out using CRISPR Cas9 sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP). This virus- and DNA-free approach showed increased gene editing efficiency and decreased off-target editing because CRISPR Cas9 RNP activity is preserved in cells for only approximately 48 h. Granulocytic differentiation, phagocytic function, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and chemotaxis of knockout cells showed reversion of phenotype such that edited cells resembled control cells from a healthy donor. These results indicate that CRISPR Cas9 knockout followed by autologous transplantation could be a viable treatment for SCN (50).

CRISPR Cas9 RNP was used in another study with adeno-associated virus (AAV)6 as a donor-template delivery system to repair mutations in patient-derived HSPCs. By employing specific sgRNAs to correct the ELANE L172P mutation and to target exon 4 mutations, editing efficiencies of 40% with sgRNA for ELANE-ex4 and 56% with sgRNA for ELANE-L172P were achieved. The gene repair restored neutrophil differentiation in vitro and in vivo upon HSPC transplantation into humanised mice, with normal NE levels confirmed through functional assays (51).

A pooled CRISPR screen in HSPCs was conducted to investigate the correlation between ELANE mutations and neutrophil maturation potential. Editing early exons led to nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), overcoming maturation arrest and resulting in normal engraftment. In contrast, terminal exon frameshift mutations that simulate those seen in SCN did not result in NMD and reflected the neutrophil maturation arrest observed in patient cells. Notably, the study demonstrated that only –1 frame indels inhibited neutrophil maturation, while –2 frame late exon indels were enriched and supported neutrophil survival. The first ever mouse model of ELANE-mutant SCN, exhibiting characteristic maturation arrest at the pre-myelocyte to myelocyte stage, was generated using a human haematopoietic xenograft system. This model provides opportunities to study SCN pathogenesis and to develop improved therapeutic approaches (52). Human ELANE mosaicism reports show that even as low as 11% of haematopoietic precursors with neutrophil maturation potential may prevent neutropenia and MDS/AML development (80, 81). These findings can be incorporated into future studies to better understand the disease and develop novel therapeutic approaches.

Congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia

Out of the 18 publications that met the inclusion criteria, only one has reported the use of CRISPR Cas9-mediated gene editing to correct pathogenic mutations in the myeloproliferative leukaemia virus oncogene (MPL) associated with congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia (CAMT), which employed HDR and combined HDR/NHEJ in patient-derived CD34+ cells. Characterised by a severe reduction in megakaryocyte precursors in the bone marrow, CAMT is another rare inherited disorder within the iBMFS spectrum. Megakaryocytes are responsible for producing platelets, which are crucial for blood clotting, and the absence or reduction of megakaryocytes leads to a significant decrease in platelet production, resulting in thrombocytopenia (82). CAMT is a homozygous recessive disorder caused by mutations in MPL, which encodes the thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor (83), with fewer than 100 reported cases (84). MPL is expressed on the surface of megakaryocytes and plays a crucial role in transducing the TPO signal, which is essential for the development and maintenance of these cells (85). A study showed that, likely due to impaired regulation of haematopoietic stem cell function caused by MPL mutations, approximately 50% of CAMT patients develop aplastic anaemia within the first year of life, and the mortality rate is as high as 50%, with affected individuals dying due to bleeding-related complications and complications associated with haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (86). To date, 36 different mutations in the MPL gene have been identified as causative for CAMT (83).

Only a single publication describes the use of CRISPR Cas9-mediated gene editing to correct pathogenic MPL mutations, reported as a case study. This was performed in primary HSPCs by Cleyrat et al. In this study, G117T/T814C mutant patient-derived cord blood CD34+ cells were successfully corrected through HDR-mediated gene editing. The study also demonstrated that, in addition to precise HDR correction, alternative alleles with in-frame deletions removing the mutation were generated via NHEJ or combined HDR/NHEJ events, and that partial recovery of MPL receptor trafficking and function was observed. Because CAMT patients have high circulating thrombopoietin levels, even partial recovery of MPL expression can significantly increase megakaryocytic differentiation and ameliorate disease (53).

Diamond blackfan anaemia

In Diamond Blackfan anaemia (DBA), no studies have attempted direct correction of pathogenic mutations; however, two studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review used CRISPR-Cas9 knockout (via NHEJ) to generate disease models using healthy donor CD34+ cells.

DBA, an iBMFS characterised by erythroid aplasia associated with skeletal abnormalities and predisposition to AML/MDS due to ribosome dysfunction, is an early-onset disorder with a prevalence of 5–7 cases per million live births (87). More than 20 genes that cause DBA have been identified, and around 70–80% of DBA cases are associated with heterozygous pathogenic variants in ribosomal protein (RP) genes. Variants in non-RP genes such as GATA2 and TSR2 have also been linked to DBA (88).

Since RPS19 biallelic knockout is lethal, and because RPS19 is highly sensitive to cellular stress, traditional delivery methods such as electroporation make it difficult to rescue sufficient viable cells for downstream analyses. To overcome this, Liu et al. developed a novel non-viral nanostraw delivery method to introduce CRISPR-Cas9 mRNA and RPS19-targeting sgRNA into the nucleus of CD34+ HSPCs, enabling gentle editing and improved viability (54).

In parallel, Bhoopalan et al. established an RPS19 haploinsufficiency model through CRISPR-Cas9 knockout in healthy donor CD34+ HSPCs. This model reproduced the DBA phenotype: impaired erythropoiesis, preserved myelopoiesis, increased apoptosis of colony-forming unit erythroid progenitors, and defective bone marrow repopulation (89). These defects were rescued either by lentiviral RPS19 expression or by genetic suppression of TP53, demonstrating that RPS19 haploinsufficiency impairs haematopoietic stem cell function through a TP53-dependent mechanism.

A significant limitation of lentiviral vectors is the difficulty in controlling gene dosage in HSPCs. While RPS19 expression is tightly regulated, overexpression of related genes such as RPL5 and RPL11 can stabilise TP53 by inhibiting MDM2, potentially causing TP53-dependent cell death. Therefore, targeted strategies such as inserting a wild-type cDNA cassette through CRISPR-Cas9 editing, or precise nucleotide base editing (BE) and prime editing (PE), should be considered for future therapeutic approaches (90).

Dyskeratosis congenita

In dyskeratosis congenita (DC), only one study met the inclusion criteria. This study used an HDR approach in patient-derived iPSCs. Unlike FA and SCN, where direct correction in patient HSPCs has been tested, DC research has focused on disease modelling and pathway rescue. As DC patients present with severely shortened telomeres, it is unlikely that correction of the underlying genetic mutation alone will be sufficient to restore telomere length and rescue disease phenotypes.

DC is an iBMFS characterised by marrow failure with oral leukoplakia, nail dystrophy, and reticular hyperpigmentation, along with secondary complications such as MDS, AML, squamous cell carcinoma, and pulmonary fibrosis (91). DC is a multigenetic syndrome, where pathogenic variants in 16 telomere and telomere-associated genes—critical for telomerase complex formation—lead to failure of telomere maintenance and progressive telomere shortening (91, 92).

One of the main disease-causing genes is DKC1, which encodes dyskerin, a protein essential for telomerase complex function. To study the correlation between Wnt signalling and telomere capping in DC, Woo and colleagues generated DC patient-specific iPSCs and then used CRISPR-Cas9 to correct the DKC1 mutation, producing a matched isogenic cell line (55). The group also introduced the DKC1 mutation into wild-type iPSCs, generating isogenic pairs of DC and control iPSC lines, and differentiated these into human intestinal organoids. DC tissue showed impaired Wnt activity leading to intestinal stem cell failure; however, increased expression of the telomere-capping protein TRF2, a Wnt target gene, improved DC phenotypes. The isogenic CRISPR-edited cell lines demonstrated that administering Wnt agonists can rescue intestinal stem cell failure, with agonist-treated organoids displaying detectable proliferative cells, although not as frequently as in organoids derived from CRISPR-corrected cells. These findings suggest that CRISPR-Cas9 can achieve phenotypic correction in some DC stem cells where defective Wnt signalling limits proliferation. Correction can reinstate telomere capping and rescue the stem cell defect. This study provides a foundation for further work examining Wnt pathway regulation in DC mutant stem cells (55).

Shwachman–Diamond syndrome

Even though only two publications that met the inclusion criteria were published on Shwachman–Diamond syndrome (SDS), one study trialled multiple modalities, using engineered RNA and DNA approaches as well as base editing and prime editing to correct a pathogenic variant, tested in HEK293T and B lymphoblastoid cell lines. The other study focused on creating an SBDS-deficient disease model using CRISPR-Cas9 indel mutagenesis (56, 57).

Characterised by three hallmark features—neutropenia, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, and skeletal abnormalities—SDS is another disorder within the iBMFS spectrum and occurs in approximately 1 in 75,000 live births (93, 94). Due to these hallmark features, secondary complications such as failure to thrive, gastrointestinal complications (including steatorrhoea and malabsorption), eczema, and attention deficit disorder are common (95, 96). Approximately 10–30% of patients with SDS later develop myeloid neoplasms such as MDS or AML (97). Approximately 90–95% of SDS cases are caused by biallelic pathogenic variants in the Shwachman–Bodian–Diamond syndrome (SBDS) gene, located on chromosome 7q11, which encodes a ribosome maturation factor. The most common pathogenic variants are c.258 + 2T>C (a splice-site variant) and c.183_1844TA>CT (a two–base pair inversion) (98).

The pathogenic c.258 + 2T>C splice-site variant leads to aberrant pre-mRNA splicing by utilising an upstream cryptic 5′ splice site located at positions c.251–252, causing an 8 bp frameshift deletion (99). In a study evaluating the editing efficiencies of various RNA- and DNA-based approaches—including engineered U1snRNA, trans-splicing, base editors, and prime editors—the authors showed that DNA editors stably corrected the mutation, with higher efficiencies leading to proper SBDS pre-mRNA splicing. Notably, when using a PE2-SpG system, the same pegRNA set was compared using single- or dual-guide RNA approaches. The Twin-PE strategy, where two pegRNAs target complementary DNA strands, produced higher editing efficiency than the single-PE approach (56).

Developing an animal model has been challenging because mice lacking SBDS (sbds-/-) are embryonically lethal. A homozygous SBDS-deficient zebrafish model, incorporating seven indel mutations generated through CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis, closely recapitulates the human disease phenotype, demonstrating growth arrest and gastrointestinal atrophy during the larval stage, along with stress responses—some linked to TP53—contributing to SDS pathophysiology. Homozygous mutant zebrafish showed progressively reduced SBDS protein levels, reflected by decreased 80S ribosomes on polysome analysis (57). This approach provides a pivotal tool for understanding disease mechanisms and forms a foundation for future therapeutic genome correction. Altogether, these studies expand the potential therapeutic role of CRISPR-Cas9 for precise editing and disease modelling.

MDS/AML predisposition

Disorders within the iBMFS spectrum carry an increased tendency to develop haematological malignancies such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). (2) MDS, defined as a clonal haematopoietic disorder by the World Health Organization, is characterised by cytopenias due to decreased haematopoiesis combined with single- or multilineage dysplasia (100). AML is characterised by the rapid proliferation of leukaemic blast cells, with more than 30% myeloid blasts present in the bone marrow (101). Mutations in several genes—including GATA2, RUNX1, CEBPA, ANKRD26, ETC6, DDX41, and SAMD9/SAMD9L—are often identified in association with MDS/AML predisposition (102, 103).

Gene therapy has primarily focused on monogenic causes of bone marrow failure such as FA or SCN, which typically occur early in life. However, one article has been published applying CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing via NHEJ in iPSC-derived HSPCs to model MDS/AML predisposition.

RUNX1 (runt-related transcription factor 1) is recognised as a key factor in embryogenesis and definitive haematopoiesis in vertebrates, essential for HSC formation and subsequent differentiation into myeloid and lymphoid lineages. Mutations in RUNX1 lead to bone marrow failure and an increased risk of developing AML/MDS (104). In a study by Marison et al., CRISPR-Cas9 indels were introduced into patient iPSC-derived HSPCs from FA patients to model progression from iBMFS to MDS and AML. This iPSC-based system enables isogenic comparison and bypasses limitations of mouse models, where spontaneous iBMFS or MDS rarely occurs. Using this platform, researchers demonstrated that engineered RUNX1 mutations promote clonal outgrowth by blunting the P53/P21 checkpoint and activating innate inflammatory signalling—features consistent with FA-associated MDS/AML in patients. This work, which focuses on modelling the complexity of compound genetic lesions in iBMFS, is particularly significant as it establishes a foundation for using CRISPR-Cas9 not only to study but eventually to guide treatment strategies for clonal evolution in high-risk disorders (58).

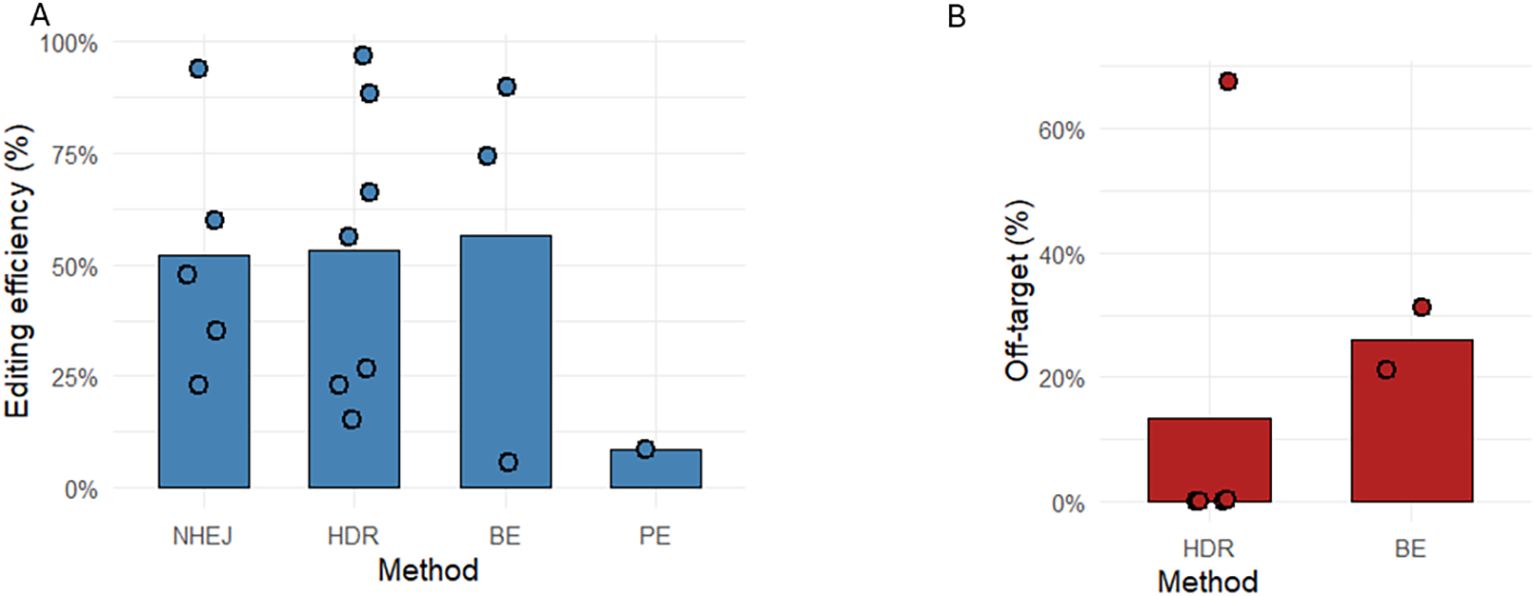

This comparative analysis of genome editing outcomes from all papers that met the inclusion criteria shows editing efficiency across NHEJ, HDR, BE, and PE, and highlights substantial variation in both editing efficiency and off-target editing observed at different loci and with different CRISPR modalities. As shown in Figure 3A, NHEJ and HDR exhibit higher efficiency, ranging from 23% to 94% (NHEJ) and 15–96.7% (HDR); however, these results are skewed to higher efficiencies due to the selection of clones containing CRISPR components. BE efficiency varies between 5.5% and 89.7%, whereas PE yielded a relatively low efficiency (8.7%) in the one included study, consistent with previous reports of widely differing efficiencies of CRISPR–Cas9 at different loci (105) and in certain cellular contexts (32). This has certainly been the prevailing experience amongst researchers, that base editing efficiency is generally higher than prime editing efficiency. Whilst the editing efficiency in the BE and PE papers is directly comparable, they are difficult to compare with the efficiencies reported in the NHEJ and HDR papers. It would be expected that NHEJ efficiency would be much higher than HDR efficiency, but the presence of selection cassettes will skew these results. The efficiencies in the NHEJ and HDR papers are more indicative that these methods are able to generate the intended edits, rather than how useful these techniques will be therapeutically. The details in Table 2 indicate what efficiency is determined by.

Figure 3. Editing efficiency and off-target mutation frequency across CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing strategies. The bar graphs show the mean editing efficiency (%) (A) for each editing method, NHEJ (n=5), HDR (n=7), BE (n=3) and PE (n=1). (B) shows mean off-target mutation rate (%), HDR (n=4), BE (n=2). Individual data points are overlaid on each bar to illustrate the distribution and variability of reported values. Each point represents a single experimental measurement obtained from the published data in this review. Entries where editing efficiency was originally represented as fractions of edited clones were transformed into percentage values to ensure uniform comparison across all studies. Only values explicitly reported in the source datasets were included. Publications with no numerical data or no mentions were excluded from the mean calculations and do not provide individual points.

The off-target mutation profile shows clear modality-specific differences, although the authors note that reporting on off-target editing remains short of best practice in this field, with off-target editing not discussed in 5 papers and not enumerated in 2 of the 18 papers. HDR exhibited the most significant variability, including a high outlier (67.5%), likely reflecting DSB-driven indels that complicate repair outcomes. NHEJ showed approximately 8% off-target events (range 3.57–12%), consistent with the intrinsically error-prone yet mechanistically constrained nature of DSB repair. NHEJ results were not included in Figure 3, as NHEJ is intrinsically error-prone and, by design, attempts to introduce mutations, rendering it meaningless as a comparison. BE showed moderate off-target rates (21–31%), in line with known deaminase-mediated bystander activity; this off-target activity observed in base editing makes it critical to examine the entire editing window to understand how different base editors will modify the genome. Where the anticipated base changes are silent, or result in a conservative amino acid substitution, the higher efficiency of base editing may mean that it is the optimal strategy despite off-target editing. In contrast, no quantitative off-target value was reported for PE in the included publications; however, the range of off-target editing observed in other fields has been 0–2.2% (32, 106).

Notably, off-target susceptibility across all genome editing platforms is strongly modulated by the underlying chromatin architecture, DNA topology, and the cellular context in which editing occurs. Regions of open chromatin, such as transcriptionally active promoters, enhancers, and euchromatic domains, present more accessible DNA substrates, increasing the likelihood of unintended Cas activity or deaminase engagement (107, 108). Conversely, heterochromatin, nucleosome-dense regions, and tightly compacted genome domains can restrict Cas protein–guide RNA binding and reduce off-target interactions (108, 109). In addition, cell-type-specific repair pathway balance, including differential utilisation of mismatch repair, further shapes off-target profiles by altering how unintended breaks or base modifications are resolved. Cells with strong dependence on NHEJ tend to convert unintended Cas9-induced breaks into small indels (110), whereas cell types with robust HDR machinery can incorporate exogenous or ectopic DNA during repair, particularly in S/G2-biased proliferative contexts (111).

While quantitative off-target percentage is a critical metric, the biological significance of off-target edits is determined fundamentally by the nature of the resulting amino acid change. Off-target edits that lead to synonymous changes or conservative amino acid substitutions that preserve chemical similarity are less likely to disrupt protein folding, stability, or interaction surfaces (112). By contrast, non-conservative substitutions—such as charged-to-hydrophobic changes or glycine-to-proline changes—are disproportionately likely to disrupt protein tertiary structure, catalytic function, or protein–protein interactions, especially when they occur within enzymatic cores or structural motifs (113).

Detecting unintended indels, bystander editing, and off-target editing

Unintended genomic alteration is one of the many challenges that faces the application of genome editing. One of the earliest, but still effective, methods used to detect small on-target indels are mismatch-cleavage assays such as the SURVEYOR assay and T7E1 assay (114). Whilst they are simple, rapid, and cost-effective, they rely on the presence or absence of heteroduplexes, and as such do not reveal the mutation structure. This in turn means they can be difficult to interpret if the targeted locus is highly polymorphic (115). Different assays have different strengths and weaknesses; therefore, to accurately quantify off-target activity in CRISPR–Cas9-based gene therapies, the FDA recommends using a combination of methods, including genome-wide analysis. This is comprehensively reviewed elsewhere (116), but approaches that utilise targeted deep sequencing remain the most accurate ways of detecting off-target editing, and include CIRCLE-seq, DIG-seq, CHANGE-seq, RGEN-seq, ONE-seq, Extru-seq, Digenome-seq, or SITE-seq (to measure cell-free DNA), or direct in-cell methods such as BLESS, BLISS, IDLV integration, AAV integration, OliTag-seq, INDUCE-seq, SURRO-seq, ABSOLVE-seq, GUIDE-seq, or Discover-seq (117, 118). To ensure genome stability, complementary methods such as whole-genome sequencing (ideally incorporating long-read data) or specialised structural variant assays, including CAST-seq, LAM-HTGTS, or UDiTaS, can detect large deletions, vector integrations, and translocations (117–120). For editors that use base or prime editing, editor-aware genome-wide assays—e.g., EndoV-seq for ABEs, Detect-seq for CBEs, and emerging PE-focused methods such as TAPE-seq—can help detect editor-specific off-target effects (121–123). Orthogonal strategies provide a comprehensive framework for assessing editing fidelity and should be applied to research as well as preclinical evaluation of CRISPR–Cas9 to align with current regulations and ensure safety prior to patient involvement. Finally, the long-term safety of editing small numbers of HSCs—given that iBMFS typically results in low numbers of CD34+ cells remaining at diagnosis—that will ultimately result in clonal dominance in the HSC compartment will need careful evaluation in patients receiving gene-edited therapies. The safety of trials of base editors in sickle cell disease is being watched closely by researchers and clinicians alike (124).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this review highlights the potential of CRISPR–Cas9-mediated gene therapy in the context of iBMFS. Recent research studies and preclinical trials have begun to explore the applications of this cutting-edge technology, aiming to enhance understanding of its therapeutic use. CRISPR–Cas9 systems have progressed significantly since their introduction to the medical field, demonstrating notable efficiency and precision in targeting specific genetic mutations, and with recently introduced techniques enabling the insertion of large gene fragments into the genome (125) the authors believe that future research will make a significant impact.

Despite these advances, the journey towards clinical implementation remains complex. Ongoing research must address critical factors such as long-term safety and effectiveness, alongside reducing off-target effects to the lowest possible level. The heterogeneous nature of iBMFS is likely to mean that these approaches are not optimal for all diseases; for example, concerns over the effectiveness of correction strategies in Dyskeratosis Congenita remain unresolved. Nevertheless, the potential of CRISPR–Cas9-based gene therapy remains promising, particularly in settings where no matched donor is available, and potentially in the future for in vivo delivery of gene-editing approaches to non-haematopoietic compartments.

By continuing to refine the understanding and application of this technology, scientists may pave the way for new, life-altering treatments for individuals suffering from iBMFS, ultimately transforming patient outcomes and improving quality of life.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. RK: Writing – review & editing. AH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. KF: Resources, Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. KF is supported by the Alex Gadomski Fellowship, funded by Maddie Riewoldt’s Vision. AH is supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Leadership Fellowship. Additional grant support was provided by NHMRC; KF (GNT 2020517) and RK (GNT 2019968). NM is supported by research training program scholarship from the University of Tasmania.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Kim HY, Kim HJ, and Kim SH. Genetics and genomics of bone marrow failure syndrome. Blood Res. (2022) 57:86–92. doi: 10.5045/br.2022.2022056

2. Dokal I and Vulliamy T. Inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Haematologica. (2010) 95:1236–40. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.025619

3. Moore CA and Krishnan K. Bone marrow failure. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC, Treasure Island (FL (2024).

4. Rappeport JM, Parkman R, Newburger P, Camitta BM, and Chusid MJ. Correction of infantile agranulocytosis (Kostmann’s syndrome) by allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Am J Med. (1980) 68:605–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90312-5

5. Calado RT and Clé DV. Treatment of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes beyond transplantation. Hematology. (2017) 2017:96–101. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.96

6. Bonilla MA, Gillio AP, Ruggeiro M, Kernan NA, Brochstein JA, Abboud M, et al. Effects of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on neutropenia in patients with congenital agranulocytosis. New Engl J Med. (1989) 320:1574–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906153202402

7. Broder MS, Quock TP, Chang E, Reddy SR, Agarwal-Hashmi R, Arai S, et al. The cost of hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in the United States. Am Health Drug Benefits. (2017) 10:366–74.

8. Lu Y, Xiong M, Sun R-J, Zhao Y-L, Zhang J-P, Cao X-Y, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for inherited bone marrow failure syndromes: alternative donor and disease-specific conditioning regimen with unmanipulated grafts. Hematology. (2021) 26:134–43. doi: 10.1080/16078454.2021.1876393

9. Pasquini MC. Impact of graft-versus-host disease on survival. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. (2008) 21:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2008.02.011

10. Lee SJ, Nguyen TD, Onstad L, Bar M, Krakow EF, Salit RB, et al. Success of immunosuppressive treatments in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2018) 24:555–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.10.042

11. Gluckman E, Auerbach A, Ash RC, Biggs JC, Bortin MM, Camitta BM, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplants for Fanconi anemia. A preliminary report from the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. Bone Marrow Transplant. (1992) 10 Suppl;1:53–7.

12. Xu L, Lu Y, Chen J, Sun S, Hu S, Wang S, et al. Fludarabine- and low-dose cyclophosphamide-based conditioning regimens provided favorable survival and engraftment for unmanipulated hematopoietic cell transplantation from unrelated donors and matched siblings in patients with Fanconi anemia: results from the CBMTR. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2023) 58:106–8. doi: 10.1038/s41409-022-01838-9

13. Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, Dicarlo JE, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. (2013) 339:823–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033

14. Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, and Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. (2012) 337:816–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829

15. Urnov FD, Rebar EJ, Holmes MC, Zhang HS, and Gregory PD. Genome editing with engineered zinc finger nucleases. Nat Rev Genet. (2010) 11:636–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2842

16. Miller JC, Tan S, Qiao G, Barlow KA, Wang J, Xia DF, et al. A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. (2011) 29:143–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1755

17. Ishino Y, Shinagawa H, Makino K, Amemura M, and Nakata A. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J Bacteriol. (1987) 169:5429–33. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5429-5433.1987

18. Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H, Richards M, Boyaval P, Moineau S, et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. (2007) 315:1709–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1138140

19. Sternberg SH, Redding S, Jinek M, Greene EC, and Doudna JA. DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature. (2014) 507:62–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13011

20. Jiang F and Doudna JA. CRISPR-cas9 structures and mechanisms. Annu Rev Biophys. (2017) 46:505–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-010822

21. Liu M, Rehman S, Tang X, Gu K, Fan Q, Chen D, et al. Methodologies for improving HDR efficiency. Front Genet. (2018) 9:691. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00691

22. Rothkamm K, Krüger I, Thompson LH, and Löbrich M. Pathways of DNA double-strand break repair during the mammalian cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol. (2003) 23:5706–15. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5706-5715.2003

23. Yang H, Ren S, Yu S, Pan H, Li T, Ge S, et al. Methods favoring homology-directed repair choice in response to CRISPR/Cas9 induced-double strand breaks. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186461

24. Leal AF, Herreno-Pachón AM, Benincore-Flórez E, Karunathilaka A, and Tomatsu S. Current strategies for increasing knock-in efficiency in CRISPR/Cas9-based approaches. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:2456. doi: 10.3390/ijms25052456

25. Song B, Yang S, Hwang G-H, Yu J, and Bae S. Analysis of NHEJ-based DNA repair after CRISPR-mediated DNA cleavage. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:6397. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126397

26. Sansbury BM and Kmiec EB. On the origins of homology directed repair in mammalian cells. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073348

27. Doudna JA. The promise and challenge of therapeutic genome editing. Nature. (2020) 578:229–36. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1978-5

28. Zheng Y, Li Y, Zhou K, Li T, Vandusen NJ, and Hua Y. Precise genome-editing in human diseases: mechanisms, strategies and applications. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. (2024) 9:47. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01750-2

29. Amendola M, Brusson M, and Miccio A. CRISPRthripsis: the risk of CRISPR/Cas9-induced chromothripsis in gene therapy. Stem Cells Trans Med. (2022) 11:1003–9. doi: 10.1093/stcltm/szac064

30. Michl J, Zimmer J, and Tarsounas M. Interplay between Fanconi anemia and homologous recombination pathways in genome integrity. EMBO J. (2016) 35:909–23. doi: 10.15252/embj.201693860

31. Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, et al. Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature. (2017) 551:464–71. doi: 10.1038/nature24644

32. Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature. (2019) 576:149–57. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1711-4

33. Xu F, Zheng C, Xu W, Zhang S, Liu S, Chen X, et al. Breaking genetic shackles: The advance of base editing in genetic disorder treatment. Front Pharmacol. (2024) 15:1364135. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1364135

34. Antoniou P, Miccio A, and Brusson M. Base and prime editing technologies for blood disorders. Front Genome Editing. (2021) 3. doi: 10.3389/fgeed.2021.618406

35. Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, and Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. (2016) 533:420–4. doi: 10.1038/nature17946

36. Chen L, Park JE, Paa P, Rajakumar PD, Prekop H-T, Chew YT, et al. Programmable C:G to G:C genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9-directed base excision repair proteins. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:1384. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21559-9

37. Rees HA and Liu DR. Base editing: precision chemistry on the genome and transcriptome of living cells. Nat Rev Genet. (2018) 19:770–88. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0059-1

38. Chen PJ and Liu DR. Prime editing for precise and highly versatile genome manipulation. Nat Rev Genet. (2023) 24:161–77. doi: 10.1038/s41576-022-00541-1

39. Chen PJ, Hussmann JA, Yan J, Knipping F, Ravisankar P, Chen P-F, et al. Enhanced prime editing systems by manipulating cellular determinants of editing outcomes. Cell. (2021) 184:5635–52.e29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.018

40. Hansen S, Mcclements ME, Corydon TJ, and Maclaren RE. Future perspectives of prime editing for the treatment of inherited retinal diseases. Cells. (2023) 12. doi: 10.3390/cells12030440

41. Doman JL, Sousa AA, Randolph PB, Chen PJ, and Liu DR. Designing and executing prime editing experiments in mammalian cells. Nat Protoc. (2022) 17:2431–68. doi: 10.1038/s41596-022-00724-4

42. Osborn MJ, Gabriel R, Webber BR, Defeo AP, Mcelroy AN, Jarjour J, et al. Fanconi anemia gene editing by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Hum Gene Ther. (2015) 26:114–26. doi: 10.1089/hum.2014.111

43. Osborn M, Lonetree CL, Webber BR, Patel D, Dunmire S, Mcelroy AN, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 targeted gene editing and cellular engineering in Fanconi anemia. Stem Cells Dev. (2016) 25:1591–603. doi: 10.1089/scd.2016.0149

44. Skvarova Kramarzova K, Osborn MJ, Webber BR, Defeo AP, Mcelroy AN, Kim CJ, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated correction of the FANCD1 gene in primary patient cells. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061269

45. Román-Rodríguez FJ, Ugalde L, Álvarez L, Díez B, Ramírez MJ, Risueño C, et al. NHEJ-mediated repair of CRISPR-Cas9-induced DNA breaks efficiently corrects mutations in HSPCs from patients with Fanconi anemia. Cell Stem Cell. (2019) 25:607–21.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.08.016

46. Richardson CD, Kazane KR, Feng SJ, Zelin E, Bray NL, Schäfer AJ, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in human cells occurs via the Fanconi anemia pathway. Nat Genet. (2018) 50:1132–9. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0174-0

47. Van De Vrugt HJ, Harmsen T, Riepsaame J, Alexantya G, Van Mil SE, De Vries Y, et al. Effective CRISPR/Cas9-mediated correction of a Fanconi anemia defect by error-prone end joining or templated repair. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:768. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36506-w

48. Lewis T, Barthelemy J, Virts EL, Kennedy FM, Gadgil RY, Wiek C, et al. Deficiency of the Fanconi anemia E2 ubiqitin conjugase UBE2T only partially abrogates Alu-mediated recombination in a new model of homology dependent recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. (2019) 47:3503–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz026

49. Siegner SM, Ugalde L, Clemens A, Garcia-Garcia L, Bueren JA, Rio P, et al. Adenine base editing efficiently restores the function of Fanconi anemia hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:6900. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34479-z

50. Nasri M, Ritter M, Mir P, Dannenmann B, Aghaallaei N, Amend D, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated ELANE knockout enables neutrophilic maturation of primary hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and induced pluripotent stem cells of severe congenital neutropenia patients. Haematologica. (2020) 105:598–609. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.221804

51. Tran NT, Graf R, Wulf-Goldenberg A, Stecklum M, Strauß G, Kühn R, et al. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated ELANE mutation correction in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells to treat severe congenital neutropenia. Mol Ther. (2020) 28:2621–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.08.004

52. Rao S, Yao Y, Soares De Brito J, Yao Q, Shen AH, Watkinson RE, et al. Dissecting ELANE neutropenia pathogenicity by human HSC gene editing. Cell Stem Cell. (2021) 28:833–45.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.12.015

53. Cleyrat C, Girard R, Choi EH, Jeziorski É, Lavabre-Bertrand T, Hermouet S, et al. Gene editing rescue of a novel MPL mutant associated with congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. (2017) 1:1815–26. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2016002915

54. Liu Y, Schmiderer L, Hjort M, Lang S, Bremborg T, Rydström A, et al. Engineered human Diamond-Blackfan anemia disease model confirms therapeutic effects of clinically applicable lentiviral vector at single-cell resolution. Haematologica. (2023) 108:3095–109. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2022.282068

55. Woo DH, Chen Q, Yang TL, Glineburg MR, Hoge C, Leu NA, et al. Enhancing a Wnt-telomere feedback loop restores intestinal stem cell function in a human organotypic model of dyskeratosis congenita. Cell Stem Cell. (2016) 19:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.05.024

56. Peretto L, Tonetto E, Maestri I, Bezzerri V, Valli R, Cipolli M, et al. Counteracting the common shwachman-diamond syndrome-causing SBDS c.258 + 2T>C mutation by RNA therapeutics and base/prime editing. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24.

57. Oyarbide U, Shah AN, Amaya-Mejia W, Snyderman M, Kell MJ, Allende DS, et al. Loss of Sbds in zebrafish leads to neutropenia and pancreas and liver atrophy. JCI Insight. (2020) 5. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.134309

58. Marion W, Koppe T, Chen CC, Wang D, Frenis K, Fierstein S, et al. RUNX1 mutations mitigate quiescence to promote transformation of hematopoietic progenitors in Fanconi anemia. Leukemia. (2023) 37:1698–708. doi: 10.1038/s41375-023-01945-6

59. Gupta AO, Sharma A, Frangoul H, Dalal J, Kanter J, Alavi A, et al. Initial results from the BEACON clinical study: A phase 1/2 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of a single dose of autologous CD34+ Base edited hematopoietic stem cells (BEAM-101) in patients with sickle cell disease with severe vaso-occlusive crises. Blood. (2024) 144:513–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2024-204888

60. Campbell ST. Approval of the first CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing therapy for sickle cell disease. Clin Chem. (2024) 70:1298–8. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvae038

61. Ritter MU, Nasri M, Dannenmann B, Mir P, Secker B, Amend D, et al. Comparison of gene-editing approaches for severe congenital neutropenia-causing mutations in the ELANE gene. Crispr J. (2024) 7:258–71. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2024.0006

62. Mendell JR, Al-Zaidy SA, Rodino-Klapac LR, Goodspeed K, Gray SJ, Kay CN, et al. Current clinical applications of in vivo gene therapy with AAVs. Mol Ther. (2021) 29:464–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.12.007

63. Raguram A, Banskota S, and Liu DR. Therapeutic in vivo delivery of gene editing agents. Cell. (2022) 185:2806–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.045

64. Gowing G, Svendsen S, and Svendsen CN. Ex vivo gene therapy for the treatment of neurological disorders. Prog Brain Res. (2017) 230:99–132. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2016.11.003

65. Morgan RA, Gray D, Lomova A, and Kohn DB. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy: progress and lessons learned. Cell Stem Cell. (2017) 21:574–90. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.10.010

66. Davis L and Maizels N. Homology-directed repair of DNA nicks via pathways distinct from canonical double-strand break repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2014) 111:E924–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400236111

67. Rosenberg PS, Tamary H, and Alter BP. How high are carrier frequencies of rare recessive syndromes? Contemporary estimates for Fanconi Anemia in the United States and Israel. Am J Med Genet A. (2011) 155a:1877–83. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34087

68. Kottemann MC and Smogorzewska A. Fanconi anaemia and the repair of Watson and Crick DNA crosslinks. Nature. (2013) 493:356–63. doi: 10.1038/nature11863

69. Wegman-Ostrosky T and Savage SA. The genomics of inherited bone marrow failure: from mechanism to the clinic. Br J Haematol. (2017) 177:526–42. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14535

70. Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA, and Rosenberg PS. Cancer in the National Cancer Institute inherited bone marrow failure syndrome cohort after fifteen years of follow-up. Haematologica. (2018) 103:30–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.178111

71. Ceccaldi R, Sarangi P, and D’andrea AD. The Fanconi anaemia pathway: new players and new functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2016) 17:337–49. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.48

72. Adamo A, Collis SJ, Adelman CA, Silva N, Horejsi Z, Ward JD, et al. Preventing nonhomologous end joining suppresses DNA repair defects of Fanconi anemia. Mol Cell. (2010) 39:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.026

73. Berliner N, Horwitz M, and Loughran TP Jr. Congenital and acquired neutropenia. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. (2004), 63–79. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2004.1.63

74. Horwitz MS, Corey SJ, Grimes HL, and Tidwell T. ELANE mutations in cyclic and severe congenital neutropenia: genetics and pathophysiology. Hematology/Oncology Clinics North America. (2013) 27:19–41. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2012.10.004

75. Dale DC, Person RE, Bolyard AA, Aprikyan AG, Bos C, Bonilla MA, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding neutrophil elastase in congenital and cyclic neutropenia. Blood. (2000) 96:2317–22. doi: 10.1182/blood.V96.7.2317

76. Zeng W, Song Y, Wang R, He R, and Wang T. Neutrophil elastase: From mechanisms to therapeutic potential. J Pharm Anal. (2023) 13:355–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2022.12.003

77. Nayak RC, Trump LR, Aronow BJ, Myers K, Mehta P, Kalfa T, et al. Pathogenesis of ELANE-mutant severe neutropenia revealed by induced pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. (2015) 125:3103–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI80924

78. Kosmider O, Itzykson R, Chesnais V, Lasho T, Laborde R, Knudson R, et al. Mutation of the colony-stimulating factor-3 receptor gene is a rare event with poor prognosis in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Leukemia. (2013) 27:1946–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.182

79. Skokowa J, Dale DC, Touw IP, Zeidler C, and Welte K. Severe congenital neutropenias. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2017) 3:17032. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.32

80. Ancliff PJ, Gale RE, Watts MJ, Liesner R, Hann IM, Strobel S, et al. Paternal mosaicism proves the pathogenic nature of mutations in neutrophil elastase in severe congenital neutropenia. Blood. (2002) 100:707–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0060

81. Liu Q, Zhang L, Shu Z, Ding Y, Tang X-M, and Zhao X-D. Two paternal mosaicism of mutation in ELANE causing severe congenital neutropenia exhibit normal neutrophil morphology and ROS production. Clin Immunol. (2019) 203:53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2019.04.008

82. Al-Qahtani FS. Congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia: a brief review of the literature. Clin Med Insights Pathol. (2010) 3:25–30. doi: 10.4137/CPath.S4972

83. Ballmaier M and Germeshausen M. Advances in the understanding of congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematology. (2009) 146:3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07706.x

84. Geddis AE. Congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2011) 57:199–203. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22927

85. Ballmaier M, Germeshausen M, Schulze H, Cherkaoui K, Lang S, Gaudig A, et al. c-mpl mutations are the cause of congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia. Blood. (2001) 97:139–46. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.1.139

86. Tirthani E, Said MS, and De Jesus O. Amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC, Treasure Island (FL (2024).

87. Bartels M and Bierings M. How I manage children with Diamond-Blackfan anaemia. Br J Haematol. (2019) 184:123–33. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15701

88. Ulirsch JC, Verboon JM, Kazerounian S, Guo MH, Yuan D, Ludwig LS, et al. The genetic landscape of Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Am J Hum Genet. (2018) 103:930–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.10.027

89. Bhoopalan SV, Yen JS, Mayuranathan T, Mayberry KD, Yao Y, Lillo Osuna MA, et al. An RPS19-edited model for Diamond-Blackfan anemia reveals TP53-dependent impairment of hematopoietic stem cell activity. JCI Insight. (2023) 8. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.161810

90. Bhoopalan SV, Suryaprakash S, Sharma A, and Wlodarski MW. Hematopoietic cell transplantation and gene therapy for Diamond-Blackfan anemia: state of the art and science. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:1236038. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1236038

91. Savage SA and Niewisch MR. Dyskeratosis congenita and related telomere biology disorders. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, and Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews(®). University of Washington, Seattle (WA (1993). Seattle Copyright © 1993-2025, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved.

92. Nelson ND and Bertuch AA. Dyskeratosis congenita as a disorder of telomere maintenance. Mutat Research/Fundamental Mol Mech Mutagenesis. (2012) 730:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.06.008

93. Minelli A, Nicolis E, Cannioto Z, Longoni D, Perobelli S, Pasquali F, et al. Incidence of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2012) 59:1334–5. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24260

94. Burroughs L, Woolfrey A, and Shimamura A. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: a review of the clinical presentation, molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. (2009) 23:233–48. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.01.007