- Department of English and Literature, University of Bisha, Bisha, Saudi Arabia

Introduction: Comparative constructions are a core syntactic and semantic feature across Arabic varieties, yet their dialectal realizations remain unevenly documented. Despite extensive research on Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and major dialects, the comparative system of Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA)—a distinct southern Saudi dialect—has received virtually no systematic linguistic attention. This study addresses this critical gap by identifying the unique forms and functions of comparative constructions in BCA and situating them within the broader spectrum of Arabic dialectology, with reference to parallels and divergences from MSA and other regional varieties.

Methodology: Data were collected from undergraduate student discourse during grammar class interactions and social media content, including TikTok and X (formerly Twitter). Comparative expressions were identified, systematically extracted, and categorized into distinct structural types: simple comparatives, complex comparatives, equality comparisons, non-scalar comparisons, quantitative and qualitative comparisons, intensified comparisons, adverbial and clausal comparisons, and comparative correlatives. A qualitative analysis was conducted to describe the patterns and functions of these constructions in BCA.

Results: The analysis revealed that BCA employs a versatile and adaptive system of comparative constructions, characterized by simplicity and pragmatic efficiency. Unlike the rigid grammatical rules of MSA, which heavily rely on the classical ʔafʕal pattern with case markings, BCA prioritizes syntactic flexibility and contextual clarity. Markers such as ʔaktar (“more”), ʔagall (“less”), and informal terms like zaay and kan (“like”) were prominent. The dialect incorporates nominal, adverbial, and clausal comparisons, enabling speakers to convey equality, difference, and intensification effectively. Expressions such as b-kathiir (“much more”) and b-milyoon marrah (“a million times”) enhance expressiveness, while correlatives like kul ma (“the more”) highlight causal and proportional relationships. These trends align with patterns observed in other Arabic dialects, such as Egyptian and Levantine Arabic, which emphasize accessibility in spoken communication.

Discussion: The findings suggest that BCA adapts traditional grammar to prioritize conversational needs, striking a balance between practicality and clarity. This research contributes to the broader understanding of Arabic dialectal variation and highlights the role of colloquial forms in meeting modern communicative demands. The results offer valuable insights for linguists, translators, and educators working with Arabic dialects.

1 Introduction

Language functions as a core tool of human communication, evolving across time to adapt to shifting cultural, social, and technological landscapes. As these changes unfold, many languages exhibit a tendency toward structural simplification, especially in spoken contexts. This shift from complex formal systems to more intuitive, accessible forms is well-documented across global linguistic landscapes and is particularly salient in the Arabic-speaking world. Arabic, with its vast geographical reach and deep historical roots, presents a rich spectrum of dialectal variation, from Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) to region-specific vernaculars (Holes, 2004; Badawi et al., 2013).

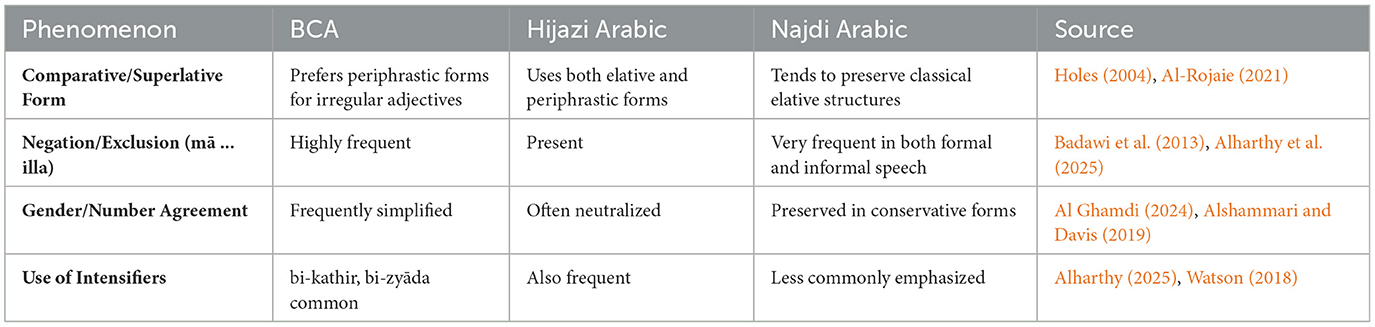

Among the lesser-studied varieties is Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA), spoken in the southwestern region of Saudi Arabia. While dialects such as Hijazi Arabic and Najdi Arabic have been examined in terms of phonological, morphological, and syntactic variation (Alshammari and Davis, 2019; Al-Mubarak, 2016), BCA remains underrepresented in academic literature. Initial studies on BCA indicate morphosyntactic simplification, a tendency toward analytic constructions, and the frequent use of pragmatic intensifiers, marking it as a distinctive dialectal variety that balances expressive richness with structural economy (Alharthy, 2025; Al Ghamdi, 2024).

As MSA continues to dominate formal discourse—literature, education, and media—colloquial dialects like BCA play a central role in informal, spontaneous communication. These dialects evolve to meet the practical demands of everyday interactions, favoring flexibility over rigid grammatical adherence. Within this context, comparative constructions emerge as a key linguistic resource for expressing differences, preferences, and hierarchies.

1.1 The role of comparative constructions in communication

Comparative structures are foundational to descriptive and evaluative discourse. They enable speakers to articulate differences in attributes such as height, size, beauty, skill, or frequency. In BCA, comparatives and superlatives serve not only grammatical functions but also pragmatic ones—allowing for emphasis, emotional expression, and rhetorical effect. Unlike Classical Arabic, which relies heavily on strict morphological agreement, BCA often simplifies these structures by using default masculine forms, adopting periphrastic constructions (e.g., ʔaktar + noun), and integrating intensifiers (e.g., bi-zyāda, bi-kathir) to enhance communicative clarity. These features parallel developments observed in Hijazi Arabic, while Najdi Arabic often retains more conservative agreement and morphological forms (Al-Rojaie, 2021; Alshammari and Davis, 2019).

1.2 Objectives of the study

This study investigates the comparative constructions in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA) with the following objectives:

• To document and classify the syntactic patterns and lexical markers used in BCA to express comparison;

• To analyze pragmatic functions of comparative forms in spoken discourse;

• To contrast BCA's strategies with those of Hijazi, Najdi, and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) varieties;

• To assess the extent to which BCA exhibits linguistic simplification, innovation, or preservation of classical structures.

By situating BCA within the broader landscape of Saudi dialectology, this study expands our understanding of regional variation and highlights the ways in which dialects evolve to accommodate communicative efficiency and social relevance.

1.3 Research questions

To guide this inquiry, the study addresses the following questions:

• What are the different patterns of comparison used in daily communication in BCA?

• How are comparative forms utilized in BCA to express comparison?

• How are superlative forms employed in BCA to convey comparison?

• To what extent does BCA resemble Classical Arabic, MSA, and other spoken Arabic dialects (e.g., Hijazi and Najdi) in expressing comparative and superlative constructions?

1.4 Significance of the study

This research makes an important contribution to Arabic dialectology by offering the first comprehensive analysis of comparative constructions in BCA. It provides empirical data that can:

• Inform teaching and translation curricula that address dialectal variation;

• Support computational models (e.g., dialect identification, sentiment analysis) by mapping syntactic patterns;

• Aid in understanding grammaticalization processes across Arabic dialects;

• Contribute to documenting underrepresented varieties within Saudi Arabia's rich linguistic ecology.

By identifying the comparative strategies in BCA, the study illuminates how dialects pragmatically diverge from formal Arabic while maintaining core grammatical logic. It underscores the dynamic interplay between tradition and innovation in Arabic's spoken forms.

1.5 Linguistic processes in BCA and other dialects

This study also compares BCA's linguistic behavior with Hijazi and Najdi dialects across several morphosyntactic domains (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of selected syntactic and morphological phenomena across Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA), Hijazi Arabic, and Najdi Arabic, based on representative sources.

These comparative dimensions position BCA as a transitional dialect—one that blends the conservative tendencies of Najdi Arabic with the analytic and expressive patterns of Hijazi and southern dialects.

2 Literature review

Comparative constructions in Arabic exhibit significant diversity across Classical Arabic, MSA, and regional dialects. This review synthesizes key studies that have explored these structures, highlighting both historical and contemporary perspectives.

2.1 Classical Arabic

In Classical Arabic, comparatives are typically formed using the elative pattern (َفْعَل, ʾafʿal), followed by the preposition “من” (min, “than”) to introduce the standard of comparison. For example, “منأكبر” (akbar min, “bigger than”) illustrates this structure. Madkhali (2022) provides an in-depth analysis of comparative constructions in the Qur'anic text, identifying three distinct types within both comparative and superlative classes. The study highlights features such as the omission of certain elements, coordination of parameters, and comparisons between items lacking shared properties. These characteristics contribute to the unique syntactic and rhetorical aspects of comparison in the Qur'an, underscoring the linguistic artistry of the sacred text.

2.2 Modern Standard Arabic

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) preserves the classical elative pattern for comparative adjectives, yet it exhibits distinct syntactic and morphological nuances. Notably, comparative adjectives in MSA remain invariable in terms of gender and number, maintaining a fixed form regardless of the subject's grammatical features. The preposition “من” (min) is essential for introducing the standard of comparison. Contemporary linguistic studies have observed a growing tendency toward periphrastic comparative constructions in MSA, indicating a broader shift toward analytical structures. For example, Pietrăreanu (2020) notes the increased use of expressions like “أكثر” (akthar, “more”) in comparative contexts, reflecting a trend toward linguistic simplification and accessibility in modern usage.

Alsulami (2018) offers a detailed syntactic account of MSA comparatives within the framework of Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG). She categorizes comparative constructions into two main types: simple and complex. Simple comparatives involve an elative adjective followed by a prepositional phrase, a pattern common to many languages. In contrast, complex comparatives are unique to MSA and feature an adjective followed by a nominal complement—often a maṣdar (verbal noun) or a regular noun—forming what resemble adjectival constructs. Unlike periphrastic constructions in other languages, which rely on multi-word analytic expressions, these complex forms in MSA are argued to be independent, productive structures that compensate for morphological gaps. Alsulami positions these constructions as integral to MSA's grammatical system, challenging their classification as merely analytic. Further, Alsulami explores nominal comparatives that quantify nouns, such as “كتب أكثر” (kutubun ʔaktar, “more books”) and “كتب أحسن” (kutubun ʔaḥsan, “better books”). These constructions involve attributive adjectives modifying plural nouns, adhering to defined syntactic constraints. Her study also distinguishes between clausal and phrasal comparatives. Clausal comparatives, typically introduced by “ما ” (maa), contain adjectival, nominal, or adverbial gaps and are prevalent in subcomparative constructions. Phrasal comparatives, in contrast, are introduced by relative elements such as “اذلي” (alladhi), “ما ” (maa), or “م" ن” (man), and feature either nominal gaps or resumptive pronouns. Ambiguity may arise, especially in “ما ” comparatives, where the structure can function either phrasally or clausally depending on contextual interpretation. Alsulami's findings underscore the complexity of MSA's comparative system and the importance of integrating morphological detail with syntactic representation for accurate linguistic modeling.

In a broader comparative context, Ryding (2025), in her review of Haddad's (2023) Grammar of Arabic, highlights the structural differences between MSA and dialects like Lebanese Arabic. While MSA relies on syntactically strict forms such as “هو أطول منك” (“He is taller than you”) with full case marking, dialectal Arabic often simplifies these forms by omitting inflectional endings, producing surface-identical strings without grammatical case realization. This simplification reflects a dialect-wide preference for morphological economy and pragmatic efficiency, especially in informal communication.

Al-Ruwaili (2025) adds a complementary dimension by examining the morphosyntactic behavior of passive participles in MSA and English. Though her primary focus lies in defining the word class status of participles, she also addresses their interaction with comparative structures in MSA. In Arabic, participles such as “مفتوح” (maftu ḥ, “open”) and “مكسور” (maksur, “broken”) frequently serve adjectival roles and may appear in comparative constructions, especially with “أكثر” (ʔaktar) to indicate a relative degree (e.g., “أكثر مفتوحًا”—“more open”). Unlike English, which maintains a rigid distinction between adjectives and participles, MSA exhibits fluid categorial boundaries. This syntactic flexibility facilitates the use of analytic comparatives in both spoken and formal contexts, contributing to a trend of structural simplification and semantic transparency.

Benmamoun and Choueiri (2013) provide a broader dialectal perspective by comparing comparative constructions in MSA and Moroccan Arabic (MA). They note that MSA adheres to morphologically marked comparative forms like “أكبر من” (“bigger than”), governed by rigid syntactic rules. In contrast, MA frequently employs more flexible periphrastic structures such as “كبير كتر من” (“big more than”), indicating a shift toward lexical and analytic expression. This strategy minimizes reliance on complex morphology, aligning with broader typological trends in spoken dialects. Despite these simplifications, Moroccan Arabic ensures semantic clarity through prosodic and contextual cues. Their analysis underscores how Arabic dialects diverge from MSA in balancing formal constraints with communicative efficiency.

The broader landscape of Arabic dialects showcases a rich diversity of comparative strategies, shaped by historical development, language contact, and sociolinguistic variation. Egyptian and Gulf Arabic, for instance, frequently utilize grammaticalized forms like “أكثر” (aktar, “more”) and “أزيد” (azyad, “excessive”) as comparative markers. Meanwhile, Maghrebi dialects—including Moroccan Arabic—display syntactic patterns influenced by Berber and Romance languages, contributing to their analytic character. These regional variations reflect both shared core structures and locally adapted innovations. The following sections will delve into comparative constructions across specific Arabic dialects, highlighting these diverse grammatical pathways and their sociolinguistic implications.

2.3 Bisha Colloquial Arabic

To date, there is a noticeable lack of prior research on syntactic phenomena in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA), with only a few recent contributions addressing specific grammatical domains. These include studies on maṣdar constructions (Alharthy, 2021), negation (Alharthy, 2025), grammaticalization processes (Alharthy, 2024), and active participles (Alharthy, 2025). Beyond these focused investigations, the broader syntactic structure of BCA remains largely underexplored in the linguistic literature.

BCA is a lesser-studied variety spoken in the southwestern region of Saudi Arabia, particularly in the Bisha governorate. As a dialect situated at the crossroads of Najdi, Asiri, and Hijazi linguistic zones, BCA exhibits features that are both unique and hybridized. It is phonologically marked by the preservation of some Classical Arabic consonants, such as /q/ in certain lexical items, while also incorporating regional simplifications and lexical borrowings. Morphosyntactically, BCA often favors analytic constructions, paralleling southern dialectal tendencies toward reduction and periphrasis. These structures are particularly evident in its comparative constructions, which frequently rely on intensified or repetitive forms for emphasis rather than the strict elative paradigm of MSA. Sociolinguistically, BCA plays a vital role in shaping local identity and community belonging. It is the dominant medium of informal communication, oral storytelling, and social media interaction within the Bisha region. Despite increasing exposure to MSA through formal education and media, BCA retains strong vitality in everyday discourse. The lack of prior academic documentation makes BCA a valuable subject for investigating underrepresented comparative forms in Arabic dialectology. This study addresses this research gap by analyzing the structure, frequency, and sociolinguistic context of comparative constructions in BCA, setting the stage for a dialect-specific contrastive analysis with MSA and other regional varieties.

2.4 Levantine Arabic

Hallman (2022) examines the syntax and semantics of comparative structures in Syrian Arabic, identifying that comparative phrases can undergo both overt and covert movement relative to their scalar associate, with specific constraints governing this displacement. These constraints align with those affecting scope interpretation, suggesting that scope construal involves covert movement mechanisms. Additionally, Hallman explores 'Comparative Deletion,' an ellipsis process in clausal comparatives, demonstrating that it relaxes movement barriers during the semantic derivation of these constructions. This phenomenon parallels observations in English; however, Hallman argues that the Arabic data indicate the suspension of movement constraints under Comparative Deletion is unique to comparative constructions, challenging attempts to generalize this effect to ellipsis processes broadly. This research contributes to a deeper understanding of the syntactic behavior of comparatives in Syrian Arabic and offers comparative insights with English, enhancing the broader field of comparative syntax. Levantine Arabic dialects, including Jordanian, Palestinian, and Lebanese, retain the elative form but may substitute the preposition “من” (min) with “عند” (‘ind), creating expressions like أحلى عندك (“prettier than you”) that reflect the Levant's historical language contact.

2.5 North African Arabic

In North African Arabic dialects, comparative constructions often diverge syntactically and morphologically from those found in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). For instance, Benmamoun (2000) highlights that Moroccan Arabic frequently omits the comparative particle “من” (min) and instead utilizes emphatic intensifiers such as بزاف (bzaf, “a lot”) to convey comparative meaning, e.g., كبير بزاف (kbir bzaf, “very big”) in place of elative forms. Similarly, Gebski (2022) notes that Tunisian Arabic demonstrates phonological compaction and structural reduction in comparative and descriptive expressions, a trend influenced by Berber substratum features. Furthermore, Flynn (2024) emphasizes that language contact phenomena in Algerian and Moroccan Arabic have reshaped comparative syntax and emphasis, reinforcing local variation in expression and pronunciation. Collectively, these studies confirm that North African dialects adopt pragmatically driven simplifications in comparison, diverging notably from the formal structure of MSA.

2.6 Saudi Bedouin dialects

In Saudi Arabia's dialects—particularly Najdi, Hijazi, and Bedouin varieties—comparative constructions often exhibit features of emphatic language and morphosyntactic simplification, reflecting both historical influences and contemporary usage trends. For example, the emphatic structure “أكبر بألف مرة” (akbar b-alf marrah, “a thousand times bigger”) is commonly used in oral exaggeration and evaluative speech, particularly in Bedouin and Najdi registers, where expressiveness is culturally valorized. According to Aftan (2024), such constructions are frequently observed in social media sentiment data, with dialect speakers preferring forms like “أحسن منك” (aḥsan mink, “better than you”) or “أحلى منك” (aḥla mink, “prettier than you”) in informal and affective contexts. These simplified comparatives—often devoid of case or gender agreement—contrast with their more formal MSA equivalents (e.g., ʔaḥsanu minka), illustrating a shift toward pragmatic efficiency and syntactic reduction.

Aftan's computational analysis of Saudi dialect corpora using a generative AI model reveals distinct regional preferences for comparative forms. Urban dialects, such as Hijazi Arabic, tend to incorporate periphrastic comparatives (e.g., ʔaktar jamālan min, “more beautiful than”), while rural and Bedouin varieties favor synthetic and intensified forms. His findings also confirm the prevalence of code-switching between Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and local dialects, particularly in online rhetorical or sarcastic discourse, where comparative phrases often carry sentiment polarity. These observations support the growing body of literature suggesting that comparative syntax in Saudi dialects serves not only a grammatical function but also encodes regional identity, emphasis, and emotional tone.

3 Methodology

The study explored comparative patterns in BCA by analyzing selected discourse samples from two primary sources: a) Participants: data were collected from 20 undergraduate students majoring in English language and translation during grammar class interactions. b) Social Media Content: comparative expressions were also gathered from social media posts by influencers and from comments by followers on platforms such as TikTok and X (formerly Twitter). Comparative expressions within these discourse samples were identified and systematically extracted. The extracted lexical items were categorized based on the various comparative structures found in BCA, simple comparatives, complex comparatives, equality comparisons, non-scalar comparisons, quantitative and qualitative comparisons, intensified comparisons, adverbial and clausal comparisons, and comparative correlatives. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data collection and classification, the data was reviewed and validated by two professors specializing in English language and English-Arabic translation. The findings of the study were reported qualitatively, offering a detailed exploration of comparative patterns in BCA.

4 Data description and analysis

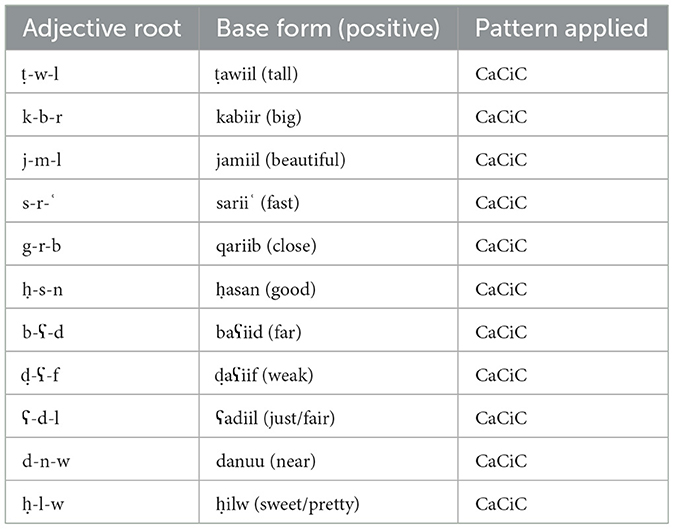

Adjectives play a central role in expressing comparison by highlighting differences in characteristics such as size, color, weight, length, or appearance. In Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA), elative comparative adjectives are primarily employed to denote comparative relationships. These adjectives adhere to specific morphological patterns that trace their origins to the Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) system of adjective formation. Interestingly, superlative adjectives in BCA follow the same morphological structure as comparative adjectives, reinforcing the syntactic parallelism between the two forms. In Arabic linguistics, the formation of comparative adjectives is rooted in a morphological template, termed as the ‘elative' pattern, used to derive both comparative and superlative forms in Arabic. According to Versteegh (2014), this pattern exhibits distinct syntactic and semantic properties across different Arabic varieties. Specifically, comparative adjectives in Arabic are constructed using the ‘ʔaCCaC' pattern, where the Cs represent the consonantal root of the adjective.

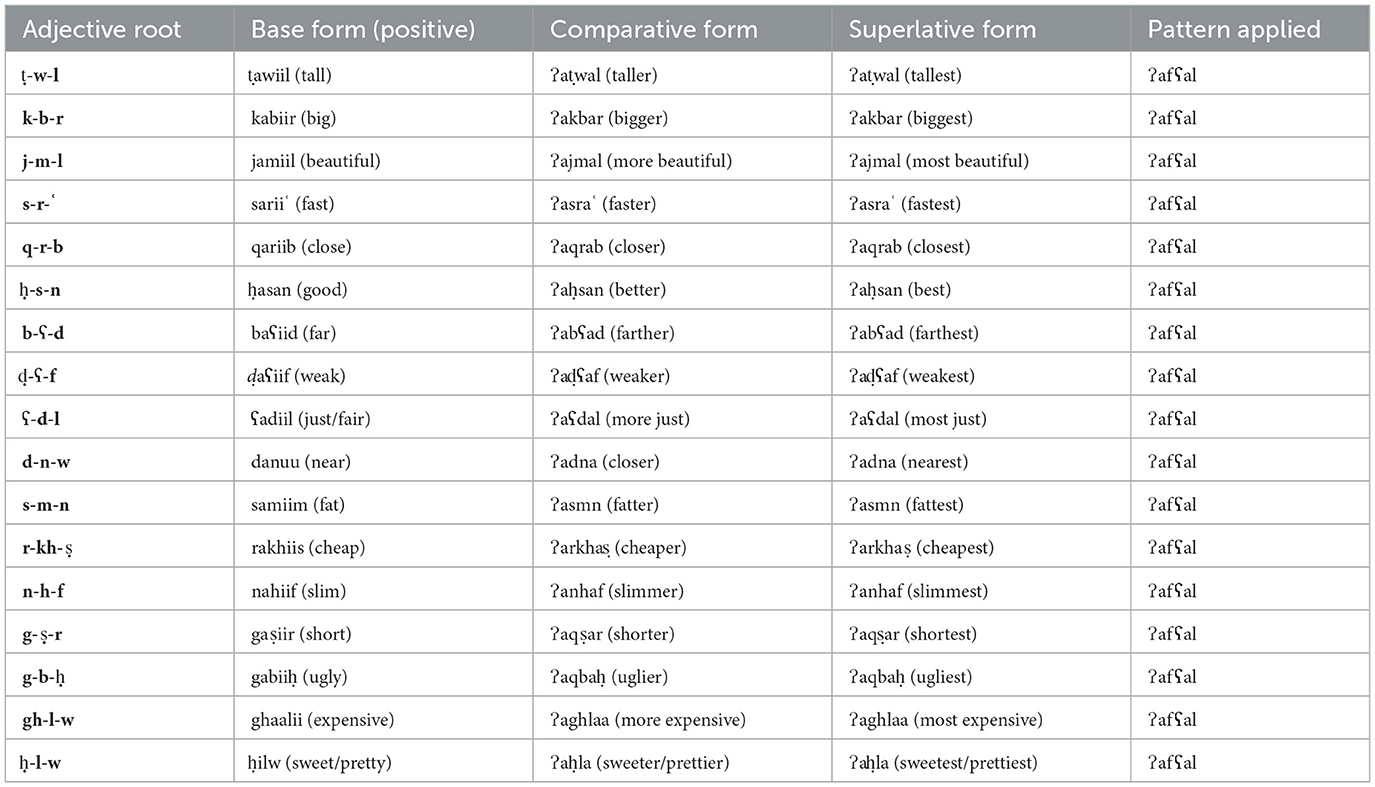

The pattern of comparative adjective formation in Arabic plays a central role in indicating prominence or superiority. Crucially, this same pattern is used to generate superlative adjectives, underscoring its dual function in Arabic morphology (Versteegh, 2014). For instance, consider the roots j-m-l in jamiil (“beautiful”) and ḥ-s-n in ḥasan (“good”). Their elative forms, ʔajmal (“more beautiful”) and ʔaḥsan (“better”), demonstrate how consonantal roots (j-m-l and ḥ-s-n) are slotted into the ʔaCCaC template to produce comparative and superlative forms. This morphological framework, foundational to Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), also governs comparative constructions in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA).

However, this study investigates whether BCA introduces dialect-specific adaptations to these patterns, shedding light on the morphosyntactic evolution of comparative and superlative forms in spoken Arabic dialects. In fact, BCA follows the same template used for forming comparative adjectives in MSA. Table 2 provides the base forms (positive adjectives) commonly used in BCA, along with their morphological patterns based on the CaCiC template, which is prevalent in Arabic adjective formation.

In BCA, the elative pattern ‘ʔafʕal' is used to express superlatives, much like in MSA. The interpretation of the ʔafʕal form as either comparative or superlative depends upon the linguistic context as in خالد أطول من راميXaalid ʔaṭwal min Rami ‘Khalid is taller than Rami' (Comparative Elative) and فاتن أطول طالبه في الفصلFaatin ʔaṭwal ṭaalibah fi l-faṣl ‘Faatin is the tallest student in the class.' (Superlative Elative). In the comparative use, the ʔafʕal form is immediately followed by the preposition ‘min' (‘from'), forming a standard of comparison. In the superlative use, however, the ʔafʕal form functions as the head of a genitive noun phrase (NP) in the construct state (iḍāfah). This construct state inherently blocks the use of the ‘min-phrase', thereby signaling a superlative interpretation. In BCA, as in MSA, superlative elatives generally carry a definite interpretation, which can be established in two ways:

1. Construct state structure (iḍāfah):

The elative adjective inherits definiteness from the noun it governs in the construct state as in ʕali wa xaalid ʔafḍal ṭ- ṭaalibaat ‘Ali and Khalid are the best students' or Xaalid ʔaṭwal ṭaalib fi l-faṣl. ‘Khalid is the tallest student in the class' (Construct State Structure).

2. Definite article ‘l' (the):

The elative takes the definite article ‘l', allowing it to exhibit gender and number agreement with the subject, as in l-iʔxwaan l-ʔafaaḍil ‘Brothers are the best.' Or l-iʔxwaat hum l-ʔafaaḍil ‘sisters are the best.' In these examples, the elative form inherits definiteness from the definite article ‘l' and adjusts to gender and number agreement as required.

If superlative elative forms appear in a construct state, they would be followed by either a definite or an indefinite noun phrase. However, morphological agreement depends on the definiteness of the noun phrase: a) Indefinite Noun Phrase: the elative appears in the masculine singular form, regardless of the gender or plurality of the subject, as in علي وخالد افظل الطلاب(ʕali wa xaalid ʔafzal ṭ- ṭaaliblaab) ‘Ali and Khalid are the best students. 'b) Definite Noun Phrase: the elative can show agreement in gender and number with the subject, such as هي الافظل(hiya l-ʔafḍal) ‘She is the best', هم الافظ(hum l-ʔafaaḍil)‘They are the best', or هم الافظ(hum l-fuḍlayaat) ‘They (feminine) are the best.' A notable characteristic of BCA superlatives is the absence of dual forms, and the lack of gender distinction in plural forms. Unlike other dialects or MSA, where dual agreement is permitted in certain contexts, BCA restricts superlative adjectives to singular forms, even when referring to dual subjects. For example, علي وخالد افظل) طالبينʕali wa xaalid ʔafḍal-aaṭaalib-yaini (‘Ali and Khalid are the best students.' Also, علي وخالد افظل الطلاب(ʕali wa xaalid ʔafḍal ṭ- ṭaaliblaab) ‘Ali and Khalid are the best students,' (both are grammatical in BCA). This constraint simplifies morphological agreement in BCA, favoring syntactic efficiency over formal complexity. Table 3 illustrates how superlative adjectives in BCA are formed using the elative pattern ‘ʔaf ʕal' by inserting consonantal roots into the template. The examples highlight the morphological consistency in superlative formation, reflecting patterns shared with MSA but also demonstrating dialectal adaptations in usage and agreement.

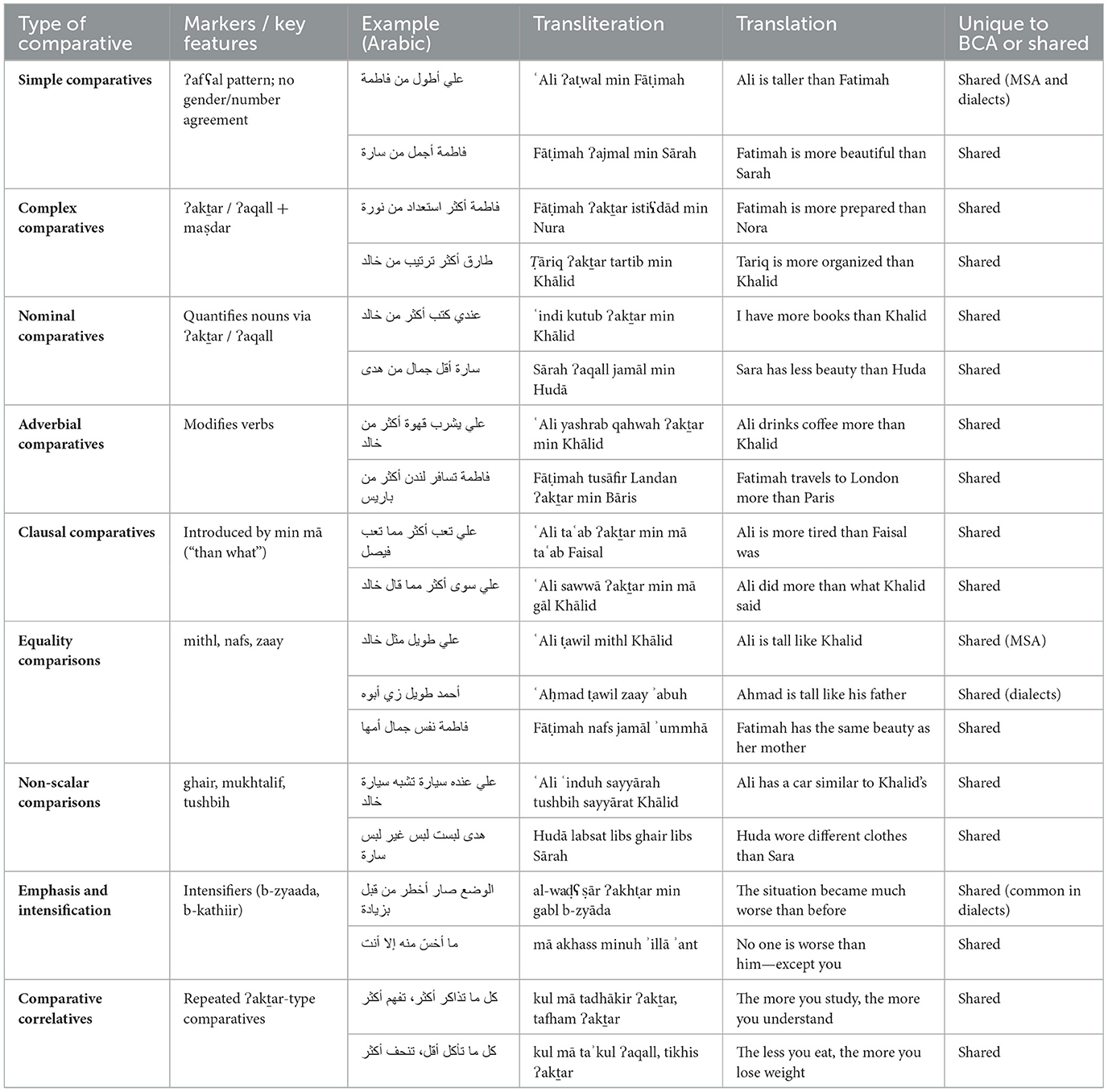

The analysis of adjective formation in BCA reveals a consistent and simplified morphological system grounded in Arabic grammatical traditions. It maintains the ʔafʕal pattern for comparatives and superlatives while streamlining syntactic rules to accommodate dialectal needs. This balance between historical continuity and dialectal adaptation highlights the linguistic flexibility of BCA, making it an ideal case study for examining Arabic morphosyntax in vernacular contexts. BCA exhibits a rich system of comparatives that reflects both morphological simplicity and syntactic flexibility. These comparatives are categorized into simple and complex constructions, each serving distinct functions while adapting to the spoken nature of the dialect. Unlike MSA, BCA does not use case marking, simplifying agreement patterns and relying heavily on contextual cues to convey meaning.

4.1 Simple comparatives

Simple comparatives in BCA are primarily formed using the ʔafʕal pattern, derived from Classical Arabic (CA) and retained in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). This pattern transforms the root consonants of an adjective into a template, enabling the formation of comparative and superlative forms. For example, kabiir (“big”) becomes ʔakbar (“bigger”), and jamiil (“beautiful”) transforms into ʔajmal (“more beautiful”). Examples of simple comparatives in BCA include: علي أطول من فاطمةAli ʔaṭwal min Fatimah– “Ali is taller than Fatimah.” Or فاطمة اجمل من سارة Fatimah ʔajmal min Sara— “Fatimah is more beautiful than Sara.” In predicative use, the comparative adjective functions as the predicate in a verbless sentence (nominal sentence), as in أنت أخسّ منه (ʾanta akhas min-h) ‘You are worse than him', فاطمة احسن من ريمFatimah ʔaḥsan min Reem—“Fatimah is better than Reem.” In attributive use, the comparative adjective modifies the noun directly, maintaining definiteness but keeping the masculine singular form, regardless of the gender or plurality of the subject, as in هو أطولمن احمد Huw ʔaṭwal min Ahmed—“He is taller than Ahmed.” BCA simplify agreement patterns by avoiding gender, number, and case inflections seen in MSA. Instead, comparatives rely on default masculine singular forms, making them practical and accessible for spoken discourse without sacrificing clarity.

4.2 Complex comparatives

Complex comparatives in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA) address cases where adjectives cannot adopt the ʔafʕal pattern, commonly used for comparatives and superlatives in Arabic. These cases typically include adjectives with roots that are either longer or shorter than three consonants, such as musta ʕid (“prepared”), or adjectives that already resemble elative forms, like ʔabyaz (“white”). To handle these exceptions, BCA relies on external comparative markers, such as ʔaktar (“more”) and ʔagall (“less”). These markers are often paired with adjectival maṣdars, nominalized forms derived from adjectives—to form multi-word expressions. This approach allows speakers to express degrees of comparison even for adjectives that do not fit the ʔafʕal morphological pattern. For example, the sentence فاطمة اكثر استعداد من نورة (Fā ṭimah ʔaktar isti ʕdād min Nura) means “Fatimah is more prepared than Nora.” Similarly, من احمد (Fāṭimah ʔaktar tartib min Sāra) translates to “Fatimah is more organized than Sara.” These examples illustrate how BCA employs external markers and adjectival maṣdars to convey complex comparisons, providing greater flexibility in describing qualities that cannot be expressed through simple comparative forms.

Comparative constructions in BCA consist of several key components. The comparee is the entity being compared, such as Fatimah in the examples above. The degree marker indicates the extent of the comparison, such as ʔaḥsan (“better”) or ʔaktar (“more”). The parameter specifies the property or quality being compared, for instance, bil-jism (“in body”), which can a noun (N) or a prepositional phrase (PP). The standard marker introduces the point of comparison, typically min (“than”), followed by the standard, which is the reference point (e.g., Sara). These components work together to form two common patterns:

Comparee + Degree Marker + Parameter (N) + Standard Marker + Standard

Comparee + Degree Marker + Parameter (PP) + Standard Marker + Standard

Using these patterns, sentences like فاطمة احسن بالجسم من سارة (Fāṭimah ʔaḥsan bil-jism min Sāra), meaning “Fatimah is better in body than Sara,” and طارق اشطر بالحساب من فاطمة (Ṭāriq ʔaš ṭar bil-ḥisāb min Fāṭimah), meaning “Tariq is better at arithmetic than Fatimah,” effectively communicate comparisons with contextual precision. BCA comparatives often highlight contrasts in specific attributes, making use of adjectives and prepositional phrases. For instance:

ابها اشد بالبرد من بيشة (ʔAbhā ʔašadd bil-bard min Bisha)—“Abha is colder than Bisha.”

نورة اقل بالجمال من سارة (Nura ʔaqall bil-jamāl min Sāra)—“Nora is less beautiful than Sara.”

طارق اقوى بالانجليزي من العربي (Ṭāriq ʔaqwā bil-ʔinglizi min al-ʕarabi)—“Tariq is stronger in English than in Arabic.” These examples illustrate the use of prepositions (e.g., bil- “in”) to introduce parameters and clarify the domain of comparison, such as beauty, language skills, or climate. Unlike MSA, BCA does not rely on case markings to signal grammatical relationships. Instead, it depends on word order and prepositional markers, enhancing flexibility in spoken interactions.

4.3 Conditionals and temporal clauses in comparisons

A distinctive feature of BCA comparatives is their ability to incorporate conditional and temporal clauses for additional emphasis or context. Conditional clauses, introduced by law (“if”), and temporal clauses, introduced by lama (“when”), allow speakers to express comparisons that depend on specific circumstances or events. For example, the sentence طارق اشطر لو يذاكر من علي (Ṭāriq ʔaš ṭar law ydākir min ʕAli) translates as “Tariq is smarter than Ali if he studies.” Similarly, علي احسن لو بس يركز من خالد (ʕAli ʔaḥsan law bas yarkiz min Khālid) means “Ali is better than Khalid if he concentrates.” Temporal clauses can also be used, as in احمد يستحي اكثر من علي بس يشوفها (ʔAḥmad yistaḥi ʔaktar min ʕAli bas yšufhā), which means “Ahmad is shyer than Ali when he sees her.” Such constructions demonstrate the dynamic nature of BCA syntax, allowing comparisons to reflect conditional relationships or temporal contexts, thereby adding layers of meaning to simple comparisons.

Complex comparatives in BCA provide an effective framework for expressing nuanced comparisons, particularly for adjectives that cannot adopt the ʔafʕal pattern. These constructions utilize external markers, adjectival maṣdars, and prepositional phrases, ensuring clarity without relying on formal case markings. Conditional and temporal clauses further enhance the expressive capacity of BCA, allowing speakers to frame comparisons dynamically. While these structures simplify grammatical complexity, occasional ambiguities in interpretation highlight the importance of contextual support and flexible teaching approaches when learning or teaching BCA syntax. This analysis underscores the adaptability of Saudi dialects, demonstrating their ability to preserve grammatical precision while accommodating the needs of modern communication. BCA employs a flexible and dynamic system of comparative constructions that diverge from the more rigid grammatical frameworks found in MSA. Unlike MSA, which relies heavily on case markings and formal rules, BCA prioritizes syntactic simplicity and contextual clarity, making it highly effective for natural communication. Comparative structures in BCA can be broadly categorized into nominal, adverbial, and clausal comparatives, each serving specific purposes for expressing differences in quantity, quality, and actions.

4.4 Nominal comparatives

Nominal comparatives in BCA are used to quantify nouns, focusing on differences in amount, size, or attributes. These constructions utilize external markers like ʔaktar (“more”) and ʔagall (“less”) to establish comparisons, particularly when evaluating numerical or qualitative distinctions between entities, as in عندك كتب اكثر من خالد (ʕindak kutub ʔaktar min Khālid) “You have more books than Khalid”, or سارة اقل جمال من هدى (Sāra ʔaqall jamāl min Hudā) “Sara has less beauty than Huda.” These examples demonstrate how nominal comparatives accommodate both concrete objects (e.g., books) and abstract qualities (e.g., beauty). These structures offer flexibility through pre-nominal and post-nominal placements of comparative markers, allowing speakers to emphasize either the comparee or the standard of comparison based on context.

4.5 Adverbial comparatives

Adverbial comparatives in BCA focus on actions, describing differences in frequency or manner rather than qualities or quantities. These structures also use external markers such as ʔaktar (“more”) and ʔagall (“less”) but modify verbs instead of nouns, as in علي يشرب قهوه اكثر من خالد (ʕAli yashrab gahwa ʔaktar min Khālid) “Ali drinks coffee more than Khalid.”, فاطمة تسافر لندن اكثر من باريس (Fāṭimah tusāfir Landan ʔaktar min Bāris) “Fatimah travels to London more than Paris.” Or فاطمة تحب الشاهي اكثر من القهوة (Fāṭimah tu ḥibb al-shāhi ʔaktar min al-qahwa) “Fatimah likes tea more than coffee.” These adverbial comparatives mirror similar constructions in English, focusing on habits, preferences, and repeated actions rather than physical characteristics or attributes. They highlight behavioral patterns and are particularly useful in conversational speech, providing insights into how frequently or intensely an action occurs.

4.6 Clausal comparatives

BCA also supports clausal comparatives, which enable more complex comparisons by embedding clauses to describe actions or quantities. These constructions typically involve the preposition min (“than”) followed by the complementizer maa and mmaa (“what”) to introduce clausal complements. This structure allows comparisons to focus on results or outcomes without repeating information unnecessarily. Examples include علي اكل موز اكثر من ما خالد اكل(ʕAli akal māwz ʔaktar min mā Khālid akal) “Ali ate more bananas than what Khalid ate.” علي سوى اكثر من ما قال خالد (ʕAli sawwā ʔaktar min mā gāl Khālid) “Ali did more than what Khalid said,” and سارة أكثر جمال مما يقولون (Sara ʔaktar jamal min maa ygaloon)، translating to “Sara is more beautiful than what they say.” These clausal comparatives introduce an added layer of syntactic depth, making them ideal for comparisons involving actions, quantities, or events. By embedding relative clauses, they maintain semantic precision while avoiding redundancy.

4.7 Equality comparisons

Equality comparisons in BCA highlight either general similarity or exact equivalence between entities. General similarity is expressed using prepositions such as mithl (“like”) and kan (“as if”), as in علي طويل مثل خالد (Ali ṭawiil mithl Khalid), meaning “Ali is tall like Khalid,” and فاطمة جميلة مثل هدىأمها (Fatimah jamiilah mithl Huda, umha), translating to “Fatimah is beautiful like her mother.” Or فاطمة كنها امها (Fāṭimah kan-ha umm-ha) “Fatimah looks like her mother.” These structures emphasize approximation without implying identical properties, much like the English terms “like” and “as.” To denote exact equality, BCA employs nafs (“same”), often in construct states (iḍāfah) with possessive pronouns to indicate shared attributes. Examples include علي نفس طول خالد (Ali nafs ṭuul Khalid), meaning “Ali has the same height as Khalid,” and شهد عندها نفس ملامح أمها (Shahadʕinda nafs malaamah umaha), translating to “Shahad has the same features as her mother.” Additional examples illustrate the versatility of this construction: علي نفس جسم أبوه (Ali nafs jism ʔabuh), meaning “Ali has the same body as his father,” فاطمة نفس جمال أمها (Fatimah nafs jamal umaha), meaning “Fatimah has the same beauty as her mother.” and فاطمة نفس عيون أمها (Fatimah nafsʕuyun umaha)—“Fatimah has the same eyes as her mother.” In these contexts, nafs highlights direct equivalence, functioning as an emphasis marker (tawkiid), and aligns with the subject in gender and number. Additionally, BCA uses mithl (“same”) to denote exact equality as in علي مثل خالد بالطول (Ali mithl Khalid bi- ṭ- ṭul)—“Ali has the same height as Khalid.” And فاطمة مثل أمها بالجمال (Fatimah mithl umaha bi-l-jamal)—“Fatimah has the same beauty as her mother.” The use of nafs reinforces direct equivalence, functioning as an emphasis marker (tawkiid) that aligns with the subject in gender and number, distinguishing it from the approximate similarity expressed by mithl. In addition to the commonly used markers mithl (“like”) BCA frequently employs zaay (“like”) to express similarity in comparisons. This usage aligns with findings from studies of other Arabic dialects, such as Egyptian Arabic, where zaay serves a similar role. Examples include فاطمة حلوه زي امها (Fatimah ḥilwa zaay ʔumaha)—“Fatimah is beautiful like her mother,” and احمد طويل زي ابوه (A ḥmad ṭawil zaay ʔabuh)—“Ahmad is tall like his father.”

4.8 Non-scalar comparisons

Non-scalar comparisons focus on identity or difference rather than degrees of comparison. Similarity is often expressed through participle adjectives like mushabbah (“similar”) or verbs such as tushbih (“resembles”). For example, علي عنده سياره تشبه سيارة خالد (Ali ʕinduh sayyaarah tushbih sayyaarat Khalid) means “Ali has a car similar to Khalid's car,” and سارة لابسه لبس يشبه لبس نورة (Sara labsah libs yshabbih libs Nora), translating to “Sara wore clothes similar to Nora's.” Another example, البنت حاطهمكياج نفس مكياج المشهورة اللي على التيك توك (al-bint haṭṭah mikyaj nafs mikyaj al-mashhurah ali ʕala al-TikTok), meaning “The girl is wearing makeup like the famous TikToker,” highlights the comparison of actions or appearances. To express distinctions, markers like mukhtalif (“different”) and ghair (“other than”) are employed. For instance, علي عنده سياره مختلفه عن سيارة خالد (Aliʕinda sayyaarah mukhtalifahʕan sayyaarah Khalid) means “Ali has a car different from Khalid's car,” هدى لابسه لبس (Huda labsah libs ghair libs Sara) translates to “Huda wore clothes other than Sara's,” and أحمد يختلف عن أبوه في الطبايع(Ahmad yakhtalif ʕan abuh fi al-tabayʕ)—“Ahmed is different from his father in nature.” These constructions eschew scalar evaluations, emphasizing identity or uniqueness instead, and reflect the dialect's pragmatic and efficient nature.

4.9 Quantitative and qualitative comparisons

BCA employs external markers like ʔaktar (“more”) and ʔagall (“less”) to construct comparisons involving quantity and quality. These markers are particularly useful for adjectives incompatible with the ʔaf ʕal (elative) pattern. Quantity-based comparisons include sentences such as عندي كتب أكثر من خالد (Indi kutub ʔaktar min Khalid), meaning “I have more books than Khalid,” and سارة أقل جمال من نورة (Sara ʔaqall jamal min Nora), meaning “Sara has less beauty than Nora.” Qualitative comparisons focus on attributes or actions, as seen in علي أحسن بالأداء من فيصل (Ali ʔaḥsan bi-ʔadaʔ min Faisal), meaning “Ali performs better than Faisal,” and سارة أحسن بالبث من هدى (Sara ʔaḥsan bil-bath min Huda), translating to “Sara is better at live streaming than Huda.” These flexible structures accommodate a variety of descriptive needs, providing clarity in both spoken and written contexts.

4.10 Emphasis and intensification

Comparatives in BCA often incorporate emphatic markers to enhance expressiveness. Words like maruh (“very”), b-kathiir (“much more”) and b-zyaada (“a lot more”) intensify the degree of comparison, adding emotive depth. For instance, كبيره مره (kabir maruh) ‘very big', الوضع صار أخطر من قبل بزيادة (al-waḍʕṣar ʔakh ṭar min gabl b-zyaada) means “The situation is a lot worse than before,” and السعودية أحسن بالأكل من بريطانيا بكثير (al-Saudiya ʔa ḥsan bil-akl min Biritania b-kathiir) translates to “Saudi Arabia has much better food than Britain.” Similarly, الوضع زمان أفضل بمليون مرة (al-waḍʕ zaman ʔafḍal b-milyoon marrah), meaning “The situation was a million times better in the past,” demonstrates an even higher level of intensification. On the other hand, preferences expressed without reliance on emphasis markers are equally prevalent in BCA. For instance, the sentence بسبريطانيا أحلى بالطبيعة (bas Biritania ʔaḥla bi- ṭ- ṭabi ʕa) translates to “But Britain is more beautiful in nature.” Similarly, constructions that incorporate hyperbolic expressions for intensification, such as فاطمة أحسن منها بألف مرة (Fatimah ʔaḥsan minha bialf marrah), meaning “Fatimah is a thousand times better than her,” البي إم دبليو أحسن بمليون مرة من نيسان (al-BMW ʔaḥsan bimalyoon marrah min Nisan), meaning “The BMW is a million times better than the Nissan,” are common in conversational Arabic. These examples reflect the dynamic range of BCA's comparative structures, from straightforward expressions of preference to highly expressive and emphatic statements. BCA also uses the structure [superlative] + كلهم (kull-hum) to serve to emphasize that the subject stands out distinctly in comparison to the entire group. This usage adds an additional layer of intensity and clarity to the comparison, as in هي أحلاهم كلهم (hiya a ḥlā-hum kull-hum) “she is the most beautiful of all of them,” or أخسهم كلهم (akhas-hum kull-hum) “she is the worst of all of them.' Additionally, BCA uses a special type of constructions that emphasizes a comparison by framing it within a negation, creating a dramatic or emphatic effect, as in ما أخس منه إلا أنت (mā akhas min-hu illā ʾant) “No one is worse than him except you.'

4.11 Comparative correlatives

Comparative correlatives in BCA represent a unique type of comparative construction that expresses a relationship between two parallel degrees of change. These constructions align with English correlatives like “The more you study, the better you perform,” wherein an increase or decrease in one property corresponds to a similar change in another. In BCA, comparative correlatives are formed by repeating comparative markers and linking two clauses with conjunctions or conditional structures. This pattern emphasizes progression or proportional relationships, making it a versatile tool for expressing nuanced ideas in daily communication. The structure of comparative correlatives in BCA consists of three primary components: a) Comparative marker: a repeated marker such as ʔaktar (“more”) or ʔagall (“less”) is used in both clauses, b) Conjunction or conditional: words like law (“if”) or ma (“what”) connect the two clauses, providing a cohesive link, c) Parallel clauses: the two clauses express corresponding increases or decreases in actions or properties. This structure enables speakers to construct sentences that highlight proportional, causal, or behavioral relationships effectively. BCA comparative correlatives can express various types of relationships. Proportional relationships demonstrate direct correspondence between two changes as in the following examples:

- كل ما تذاكر اكثر، تفهم اكثر (Kul ma tdākir ʔaktar, tafham ʔaktar) Gloss: the more you study, the more you understand.

Translation: “The more you study, the more you understand.”

- كل ما تأكل اقل، تخس اكثر (Kul ma taʔkul ʔaqall, tkhis ʔaktar) Gloss: the less you eat, the more you lose weight.

Translation: “The less you eat, the more you lose weight.” Cause-and-effect relationships highlight how one change causes another as in the following:

- كل ما يمطر اكثر، الارض تخضر اكثر (Kul ma yma ṭar ʔaktar, al-ʔarḍ tkhḍar ʔaktar) Gloss: the more it rains, the greener the land gets. Translation: “The more it rains, the greener the land becomes.”

Behavioral correlatives describe habits or tendencies:

- كل ما يتكلم اكثر، يغلط اكثر (Kul ma ytkallam ʔaktar, yighlaṭ ʔaktar) Gloss: the more he talks, the more he makes mistakes. Translation: “The more he talks, the more mistakes he makes.”

In everyday BCA speech, comparative correlatives are frequently used to emphasize causal or proportional relationships, particularly in informal and conversational settings. This flexibility allows speakers to articulate nuanced connections between actions or qualities. For instance:

- كل ما تتأخر عن النوم، تصير تعبان اكثر (Kul ma ttaʔakhkhar ʕan al-nawm, tṣir taʕbān ʔaktar) Gloss: the more you delay sleeping, the more tired you become. Translation: “The more you stay up late, the more tired you become.”

Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA) comparative correlatives exhibit several distinctive syntactic and pragmatic features that enhance their functionality in everyday communication: a) Repetition of Comparative markers: the repetition of markers such as ʔaktar (“more”) or ʔagall (“less”) in both clauses establishes a clear and parallel structure, emphasizing proportional relationships, b) Verb agreement: verbs within each clause maintain agreement with their respective subjects, ensuring grammatical consistency and coherence, c) Contextual clarity: unlike Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), BCA simplifies word order and frequently uses conjunctions to link clauses, making these constructions more accessible and suited for spoken interaction. These syntactic features reflect the adaptability of BCA comparatives, enabling speakers to succinctly and effectively express relationships between changes or contrasts. By prioritizing clarity and reducing grammatical complexity, comparative correlatives in BCA are well-suited for conversational contexts, enhancing their practicality and relevance in daily discourse.

5 Results and discussion

The analysis of comparative constructions in BCA reveals a morphosyntactically rich yet pragmatically simplified system. This system reflects both its ties to MSA and its spoken flexibility, paralleling findings in other Arabic dialects such as Egyptian Arabic (Watson, 2018) and Levantine Arabic (Habash, 2021). Through simple and complex comparatives, equality comparisons, and clausal extensions, BCA exemplifies its ability to accommodate a wide range of comparative meanings in everyday discourse.

5.1 Simple comparatives

Simple comparatives in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA) primarily utilize the ʔafʕal pattern, a morphological structure shared with both Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and many spoken Arabic dialects. This pattern modifies the root consonants of an adjective to express comparative and superlative meanings. For example, constructions such as علي أطول من فاطمة (ʿAli ʔa ṭwal min Fāṭimah, “Ali is taller than Fatimah”) and فاطمة أجمل من سارة (Fāṭimah ʔajmal min Sārah, “Fatimah is more beautiful than Sarah”) illustrate this syntactic template. However, BCA diverges from MSA in certain ways—most notably by defaulting to the masculine singular form of the comparative adjective, regardless of the gender or plurality of the subject. This characteristic simplification reflects a broader trend observed in many spoken varieties of Arabic.

Watson (2018), in her comparative analysis of southern Arabian and other Arabic dialects, notes that dialects such as Egyptian Arabic commonly preserve the elative pattern (ʔafʕal) but often apply it more flexibly, particularly by neutralizing agreement features to ease spoken interaction. Similarly, Habash (2021) emphasizes that Levantine and Egyptian dialects tend to simplify MSA comparative structures in casual speech, allowing for morphosyntactic economy that supports fluid and rapid communication. These observations align with patterns seen in BCA, where comparative forms are adapted for pragmatic efficiency rather than full morphological agreement, thus supporting a growing body of research that documents syntactic simplification across Arabic dialects.

5.2 Complex comparatives

For adjectives that cannot adopt the ʔafʕal pattern—typically due to their non-triconsonantal roots or semantic ineligibility—Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA) employs periphrastic comparatives using external markers such as ʔaktar (“more”) and ʔaqall (“less”). These markers frequently combine with adjectival maṣdars (nominalized adjective forms), as in فاطمة أكثر استعداد من نورة (Fāṭimah ʔaktar istiʕdād min Nura, “Fatimah is more prepared than Nora”) or طارق أكثر ترتيب من خالد (Ṭāriq ʔaktar tartib min Khālid, “Tariq is more organized than Khalid”). This strategy mirrors observations by Benmamoun (2000), who notes that many Arabic dialects—including Moroccan and Levantine Arabic—use ʔaktar with abstract nouns to express comparison when the adjective does not follow the elative derivation pattern.

In his broader typological work, Holes (2004) confirms that both Modern Standard Arabic and colloquial dialects resort to ʔaktar constructions to overcome morphological restrictions, especially for adjectives denoting preparedness, organization, or complexity. These multi-word comparative structures are also documented in dialects of the Levant, where ʔaktar combines with nominalized qualities like ḥilweh (“beauty”) or tartib (“neatness”) to yield expressions such as ʔaktar jamāl (“more beauty”) or ʔaktar tartib (“more organized”), as observed in Watson's (2018) comparative syntax research.

This shared reliance on external comparative markers highlights a cross-dialectal adaptation aimed at preserving semantic transparency and morphological flexibility, supporting the broader trend toward analytic expressions in spoken Arabic.

5.3 Equality comparisons

Equality comparisons in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA) utilize markers such as mithl (“like”), nafs (“same”), and zaay (“like/as”) to express similarity and equivalence. For instance, expressions like علي طويل مثل خالد (ʿAli ṭawil mithl Khālid, “Ali is tall like Khalid”) and فاطمة نفس جمال أمها (Fāṭimah nafs jamāl ʾummhā, “Fatimah has the same beauty as her mother”) illustrate syntactic parallels with both Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and regional dialects. While mithl and nafs are shared with MSA, zaay is widely used in spoken dialects—including BCA—for its informal tone and lack of inflectional complexity. According to Holes (2004), Egyptian and Levantine dialects routinely substitute zaay or zayy for MSA's more formal mithl or ka, favoring simplicity in casual contexts. For example, expressions like هو زي أبوه (huwwa zayy ʾabuh, “He is like his father”) in Egyptian Arabic and هي زي أمها (hiyye zayy ʾummhā, “She is like her mother”) in Levantine Arabic mirror the BCA usage of zaay in statements such as أحمد طويل زي أبوه (ʾA ḥmad ṭawil zaay ʾabuh). These patterns emphasize approximate equality rather than exact sameness, aligning with spoken Arabic's pragmatic focus.

Furthermore, Benmamoun (2000) highlights that nafs is consistently used in both MSA and dialects to mark precise equivalence, particularly in quantificational and attributive contexts. This supports the continuity of nafs across varieties, while also underscoring the dialectal divergence introduced by zaay. Collectively, these patterns demonstrate that BCA, like other Arabic dialects, privileges pragmatic efficiency and speaker ease through syntactic simplification and lexical versatility in equality constructions.

5.4 Non-scalar comparisons

Non-scalar comparisons in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA) are used to express similarity or distinction without involving gradability. These constructions commonly include participle adjectives or verbal structures, such as علي عنده سيارة تشبه سيارة خالد (ʾAliʕinduh sayyārah tushbih sayyārat Khālid, “Ali has a car similar to Khalid's car”), where the verb tushbih (“resembles”) signals likeness without indicating a degree. For expressing difference, BCA uses markers such as ghair (“other than”) and mukhtalif (“different”), as in هدى لابسة لبس غير لبس سارة (Hudā lābsah libs ghayr libs Sārah, “Huda wore clothes different from Sara's”). According to Holes (2004), such non-scalar expressions are widespread in Arabic dialects, particularly in Gulf and Egyptian Arabic, where ghayr and mukhtalif are favored for indicating contrast in possession, appearance, or behavior. In Moroccan and Levantine dialects, as noted by Benmamoun (2000), descriptive constructions using alternatives like ḥāja ukhra or ʔishi thāni (“something else”) also serve this non-gradable comparative function. These forms enable speakers to highlight categorical distinctions without invoking a scale, which aligns with the dialects' broader tendency toward pragmatic simplification and clarity in spoken interaction.

This shared dialectal strategy—prioritizing explicitness over morphological complexity—illustrates the flexibility of Arabic varieties in marking difference. The BCA usage of ghair, mukhtalif, and tushbih thus fits within a pan-Arabic pattern that balances syntactic economy with semantic specificity.

5.5 Quantitative and qualitative comparisons

In Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA), markers like ʔaktar (“more”) and ʔaqall (“less”) are employed to express both quantitative and qualitative comparisons. For instance, عندي كتب أكثر من خالد (ʿindi kutub ʔaktar min Khālid, “I have more books than Khalid”) exemplifies a quantity-based comparison, while سارة أحسن بالبث من هدى (Sārah ʔa ḥsan bil-bath min Hudā, “Sara is better at live streaming than Huda”) represents a qualitative evaluation. These constructions are also found in other regional dialects, including Levantine and Gulf Arabic, where simplified and semantically rich comparative forms enhance spoken clarity.

According to Al-Mubarak (2016), comparative markers such as ʔaktar are widely used in Eastern Saudi dialects, especially in Al-Ahsa Arabic, to express both numerical and evaluative comparisons, often without adhering to gender or number agreement rules found in MSA. Fadda (2019), in her study of Arabic variation in Western Amman, similarly notes that ʔaktar frequently functions in quantitative contexts, particularly when describing abstract or countable nouns. This aligns with findings by Al Sheyadi (2022) on Gulf Omani Arabic, where comparative structures are often analytic, relying on lexical markers like ʔaktar combined with a noun or nominalized adjective.

These cross-dialectal patterns support the interpretation that periphrastic comparatives offer a practical alternative to the elative form, allowing speakers to preserve semantic precision while reducing morphosyntactic load. As such, BCA's use of ʔaktar and ʔaqall reflects broader strategies of efficiency and adaptability in spoken Arabic.

5.6 Emphasis and intensification

Comparative constructions in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA) often include intensifiers such as b-kathir (“much more”) and b-zyāda (“a lot more”) to emphasize the degree of comparison, as in الوضعصار أخطر من قبل بزيادة (al-waḍʕṣār ʔakh ṭar min gabl b-zyāda, “The situation is a lot worse than before”). These emphatic markers are consistent with broader tendencies observed in Gulf dialects, where post-comparative intensification is frequently used to add rhetorical force and emotional resonance (Holes, 2004). Such constructions illustrate how spoken Arabic varieties prioritize expressive clarity and conversational immediacy.

A notable feature of BCA comparatives is the use of “لا ... ما” (e.g., “ما أخسّ منه إلا أنت”, “No one is worse than him—except you”), a structure that combines negation with exception to highlight uniqueness or contrast. This pattern has been widely studied in both Classical and colloquial Arabic. Badawi et al. (2013) describe “لا ... ما” as a syntactic frame used to restrict or isolate a referent through emphatic exclusion, especially in evaluative or adversarial contexts. It functions pragmatically to intensify comparison by suggesting that the referent is the only one outside the stated generalization. These constructions reinforce BCA's alignment with dialects that prioritize semantic intensity and stylistic economy, especially in spoken and informal registers.

5.7 Clausal and adverbial comparisons

Clausal comparatives in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA), particularly those introduced by the structure min mā (“than what”), extend comparison beyond single elements to include entire actions or propositions. This pattern, illustrated in sentences like علي تعب أكثر مما تعب فيصل (ʿAli taʿab ʔaktar min mā taʿab Faisal—“Ali is more tired than Faisal was”), reflects a syntactic flexibility also observed in other Arabic varieties. In Levantine Arabic, such constructions are common, and they frequently involve elided or restructured comparative clauses for economy and clarity in speech (Hamouda, 2014). Similarly, adverbial comparisons in BCA, such as علي يذاكر أكثر من خالد (ʿAli yudhākir ʔaktar min Khalid—“Ali studies more than Khalid”), parallel patterns in Egyptian and Palestinian Arabic, where the comparative degree focuses on action intensity rather than just nominal attributes (Darawshe, 2024; Aljuied, 2021). Holes (2004) notes that Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) maintains these structures more rigidly with clearer clause boundaries, but spoken dialects like BCA and Levantine Arabic often simplify them for spontaneous use. These findings align with broader comparative syntax across dialects, confirming that clausal comparatives provide both syntactic and pragmatic flexibility in spoken discourse.

5.8 Comparative correlatives

Comparative correlatives in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA) reflect the broader pattern observed across several Arabic varieties, where proportional relationships are expressed using structures similar to English “the more..., the more...” constructions. For instance, BCA employs expressions like كل ما تذاكر أكثر، تفهم أكثر (kul mā tdākir ʔaktar, tafham ʔaktar)—“The more you study, the more you understand.” This syntactic pattern aligns with the findings of Alqurashi and Borsley (2014), who explore the comparative correlative construction in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and find significant parallels in its morphosyntactic realization across dialects. Their research reveals that dialectal varieties often prefer more streamlined, clause-initial structures while still preserving the logical dependency between clauses. In Egyptian Arabic, Soltan (2019) identifies comparable correlation structures, particularly within informal discourse, where repeated elative markers (e.g., ʔaktar) provide emphasis and clarity. These patterns emphasize a pragmatic approach in Arabic dialects to managing complexity through predictability and repetition. BCA's usage of correlatives therefore fits within this broader cross-dialectal phenomenon, offering evidence of shared grammatical strategies and further supporting the claim that dialects balance syntactic economy with semantic transparency. The pattern confirms Arabic's morphosyntactic versatility and highlights how dialects adapt formal structures for everyday interaction while preserving essential grammatical logic.

The findings of this study on comparative constructions in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA) confirm and enrich current understandings of syntactic simplification and dialectal flexibility in Arabic. The BCA comparative system—characterized by the default use of masculine singular forms in simple comparatives, extensive reliance on periphrastic markers like ʔaktar, and the widespread use of informal intensifiers—mirrors trends seen across Levantine, Gulf, and Egyptian Arabic.

As Holes (2004) and Watson (2018) have argued, most spoken Arabic dialects prioritize morphosyntactic economy in everyday conversation. The BCA data align with this view: for example, BCA consistently simplifies agreement in comparative adjectives, echoing Habash's (2021) observations about Levantine Arabic. Moreover, the functional use of zaay in BCA, paralleling zayy in Egyptian Arabic (Watson, 2018), shows how spoken dialects prefer approximative equality expressions over strict grammatical agreement—highlighting the dialect's sociopragmatic motivations.

In contrast to Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), which maintains strict morphosyntactic constraints (cf. Benmamoun, 2000; Holes, 2004), BCA, like other dialects, employs ʔaktar constructions for non-elative adjectives (e.g., ʔaktar istiʕdād). These periphrastic forms were also documented in Fadda (2019) in the context of Western Amman Arabic and in Al-Mubarak (2016) for Al-Ahsa Arabic. This cross-dialectal trend underscores how periphrastic comparatives serve as a workaround to the limitations of the ʔafʕal morphological paradigm.

Additionally, comparative correlatives such as kul mā tdākir ʔaktar, tafham ʔaktar (“The more you study, the more you understand”) further demonstrate BCA's structural alignment with other dialects. These constructions match patterns documented in Alqurashi and Borsley (2014) for MSA and Soltan (2019) for Egyptian Arabic, confirming the underlying syntactic logic remains stable across varieties, even if surface forms vary. Finally, the BCA-specific use of intensifiers like b-zyaada and emphasis structures such as ma... illa enhances expressive clarity in speech. These emphatic patterns are less common in MSA but have been examined in dialectal speech acts (Badawi et al., 2013), where pragmatic intent supersedes syntactic conservatism.

In summary, BCA reflects both common regional trends in Arabic morphosyntax—such as simplification, analytic constructions, and pragmatic expressiveness—and unique local innovations, particularly in the choice and placement of intensifiers and the frequency of exclusionary comparatives. This dual pattern contributes to the broader Arabic linguistic landscape by showcasing how minor dialects like BCA balance historical continuity with modern communicative needs.

Table 4 outlines the key comparative markers and constructions used in BCA, highlighting unique features alongside those shared with Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and other Arabic dialects. Examples and translations illustrate the contextual application of each type.

6 Implications and limitations of the study

The comparative system in Bisha Colloquial Arabic (BCA) demonstrates a compelling balance between morphological economy and communicative efficacy. While structurally grounded in frameworks familiar from Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and other regional dialects, BCA exhibits a strong tendency toward functional simplification, driven by the demands of informal speech. For instance, the consistent use of the masculine singular form in simple comparatives, regardless of gender or number, and the widespread preference for periphrastic constructions (e.g., ʔaktar, ʔagall) in complex comparatives, point to an overarching dialectal strategy that prioritizes fluency and cognitive ease over morphological precision.

This simplification facilitates spontaneous and efficient communication, particularly in socially dynamic contexts such as oral storytelling, online discourse, and everyday conversation. Furthermore, BCA's frequent use of emphatic and contrastive forms—such as ma… illa (“none except”)—underscores the dialect's orientation toward expressiveness and rhetorical force, reflecting the sociocultural value placed on vivid and emphatic speech in the Bisha region.

From a comparative dialectological perspective, BCA both aligns with broader Arabic dialect trends and introduces localized innovations. Shared features include the reduction of grammatical agreement, reliance on external comparative markers, and the pragmatic flattening of formal structures. However, BCA distinguishes itself through region-specific features, such as the use of unique intensifiers (b-zyaada, marrah) and a marked tendency toward non-scalar comparisons, especially in familial or material contexts. These features not only enrich the typology of comparative constructions in Arabic but also affirm BCA's status as a linguistically distinct and understudied variety, underscoring the importance of fine-grained, locality-sensitive analysis in Arabic linguistics.

6.1 Implications

• Dialectal identity and documentation

The findings offer compelling linguistic evidence for recognizing BCA as an autonomous dialect within the Saudi Arabic continuum. This contributes to ongoing efforts in mapping micro-dialectal boundaries and supports the need for descriptive documentation of marginalized or underrepresented speech communities in the Arabian Peninsula.

• Pragmatics and language teaching

The pragmatic orientation and structural simplification observed in BCA have potential implications for language pedagogy, especially in designing dialect-inclusive curricula for teaching Arabic as a spoken language. Such models could promote linguistic diversity while making spoken Arabic more accessible to learners unfamiliar with formal MSA conventions.

• Computational applications

The study's documentation of BCA comparative patterns provides valuable linguistic data for natural language processing (NLP). These insights can inform the development of dialect-specific tools such as automatic dialect classifiers, sentiment analysis engines, and conversational agents tailored to Saudi Arabic, thereby improving model accuracy and regional relevance.

• Sociolinguistic insight

The variation in marker preference (e.g., zaay, kan, nafs) reflects social stratification and generational shifts. As such, comparative constructions in BCA may serve as sociolinguistic indicators of identity, levels of formality, or even rhetorical intent (e.g., sarcasm, intimacy), offering a lens for studying language and society in southern Saudi Arabia.

6.2 Challenges and limitations

Despite its contributions, this study faces several limitations that should be addressed in future research:

• Lack of prior research

The limited availability of previous studies on BCA constrained opportunities for detailed cross-dialectal comparison. Much of the comparative analysis relied on broader Gulf or Hijazi data, which may obscure finer distinctions specific to BCA.

• Oral data variability

As a predominantly spoken and undocumented dialect, BCA exhibits significant internal variation based on speaker age, gender, education, and context. This introduces challenges in identifying stable grammatical patterns and underscores the need for corpus-based, community-centered fieldwork.

• Fluid formal–informal boundaries

The interaction between BCA and MSA—particularly in semi-formal or mediated contexts (e.g., social media, broadcast media)—remains fluid and underexplored. Systematic analysis of code-switching patterns is essential for understanding how speakers navigate stylistic boundaries in practice.

• Linguistic standardization and language change

With the increasing penetration of MSA through education, media, and technology, there is a risk of structural convergence and dialectal erosion. Longitudinal research is needed to monitor how BCA's comparative system evolves over time, and whether unique features persist, shift, or vanish under external linguistic pressures.

7 Conclusion

The analysis of comparative constructions in BCA reveals a dynamic and adaptable linguistic system that seamlessly balances structural simplicity with expressive richness, effectively catering to the demands of informal and fast-paced communication. Unlike MSA, which relies on rigid grammatical rules and case markings, BCA emphasizes contextual clarity, informal structures, and pragmatic flexibility, making it well-suited for spoken discourse. The findings demonstrate that BCA employs a diverse range of comparative constructions, including simple comparatives, complex comparatives, equality comparisons, non-scalar comparisons, quantitative and qualitative comparisons, adverbial and clausal comparisons, and comparative correlatives.

Key linguistic strategies in BCA include the productive use of the ʔafʕal pattern for simple comparatives and the reliance on external markers like ʔaktar (“more”) and ʔagall (“less”) for complex comparatives, accommodating adjectives that do not conform to traditional morphological patterns. Additionally, the use of informal markers like zaay or kan (“like”) alongside MSA equivalents such as mithl and ka highlights the dialect's tendency to simplify structures while preserving semantic precision. The incorporation of prepositional phrases, nominal comparisons, and the omission of case markings further underscores BCA's focus on ease of communication in everyday contexts. Comparative correlatives in BCA are used to allow for the expression of proportional and causal relationships through repeated comparative markers and syntactic parallels. These constructions not only enhance the expressive capacity of the dialect but also align with the spoken rhythm and relational dynamics of BCA. When compared with other Arabic dialects, the findings highlight shared strategies such as the use of informal markers and simplified syntax, as well as dialect-specific features that distinguish BCA. For example, the absence of case markings and the prevalence of conversational structures reflect trends observed across Gulf Arabic dialects, supporting prior findings in Arabic sociolinguistics (e.g., Holes, 2004).

In conclusion, the comparative constructions in BCA demonstrate a versatile framework that meets the demands of modern communication while maintaining cultural and linguistic continuity. These insights contribute to a broader understanding of Arabic dialectology, offering valuable implications for linguistic research, language teaching, and computational applications like machine translation. Future studies could explore comparative constructions across other Saudi dialects to further enrich the understanding of regional linguistic diversity within the Arabic-speaking world.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

FA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. I have used CHATGPT scholar (AI) in refining the written text and in translating Arabic examples into their suitable English equivalents.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aftan, S. S. (2024). Developing a generative AI model to enhance sentiment analysis for the Saudi dialect (Master's thesis, Texas Tech University). Texas Tech University Repository. Available online at: https://ttu-ir.tdl.org/items/a36dc4b8-82b0-4057-9bd4-ec059b3e1c48

Al Ghamdi, M. A. (2024). Gender agreement in southwestern Saudi dialects. J. Arab. Linguist. 6, 53–71.

Al Sheyadi, S. B. (2022). Sociolinguistic variation in the Yāl Sa‘ad Dialect in northern Oman (Doctoral dissertation, University of Essex). University of Essex Research Repository. Available online at: http://repository.essex.ac.uk/id/eprint/32097/

Alharthy, F. (2021). Masdar constructions in Southern Saudi Arabic: A concise reference (Doctoral dissertation). Colchester: University of Essex. Available online at: https://repository.essex.ac.uk/31925/1/Fatemathesis.pdf

Alharthy, F. (2024). Grammaticalization of modal verbs in Bisha Colloquial Arabic. Int. J. Linguist. Stud. 4, 57–70. doi: 10.32996/ijls.2024.4.3.14

Alharthy, F. (2025). Quantifiers in Bisha Colloquial Arabic: a syntactic perspective. Forum Linguist. Stud. 7, 903–912. doi: 10.30564/fls.v7i2.8490

Alharthy, F. M., Alsairi, M. A., and Ali, J. K. M. (2025). Negation in Bisha Arabic. Dirasat: Hum. Soc. Sci. 52, 113–130. doi: 10.35516/hum.v52i6.6714

Aljuied, F. M. J. (2021). The Arabic (Re)dubbing of wordplay in Disney animated films (Doctoral dissertation, University College London). Available online at: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10134617/

Al-Mubarak, G. (2016). An investigation of sociolinguistic variation in al-?Aḥsā? Arabic (Doctoral dissertation, SOAS University of London). Available online at: https://www.academia.edu/download/105511270/AlMubarak_4254.pdf

Alqurashi, A., and Borsley, R. D. (2014). The Comparative Correlative Construction in Modern Standard Arabic. University of Essex Repository. Available online at: https://repository.essex.ac.uk/11786/1/alqurashi-borsley.pdf (Accessed June 24, 2025).

Al-Rojaie, Y. (2021). Perceptual mapping of linguistic variation in Saudi Arabic dialects. Pozn. Stud. Contemp. Linguist. 57, 299–324. doi: 10.1515/psicl-2021-0019

Al-Ruwaili, S. F. (2025). A systematic contrastive study of the word class status of passive participles in English and MSA. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 1.

Alshammari, W., and Davis, S. (2019). “Diminutive and augmentative formation in northern Najdi/Hā'ili Arabic,” in Perspectives on Arabic Linguistics XXXI, eds. A. Khalfaoui, and Y. Haddad (John Benjamins Publishing Company), 51–74. doi: 10.1075/sal.8

Alsulami, H. (2018). Comparative constructions in Modern Standard Arabic: an HPSG analysis. Linguist. J. Arab World 14, 33–56.

Badawi, E., Carter, M. G., and Gully, A. (2013). Modern Written Arabic: A Comprehensive Grammar. Routledge. Available online at: https://www.routledge.com/Modern-Written-Arabic-A-Comprehensive-Grammar/Badawi-Carter-Gully/p/book/9780415667494 (Accessed June 24, 2025).

Benmamoun, E. (2000). The Feature Structure of Functional Categories: A Comparative Study of Arabic Dialects. Oxford University Press. Available online at: https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Feature_Structure_of_Functional_Cate.html?id=bADDh1IZ4wUC (Accessed June 24, 2025).