- University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany

In the present study we investigate L2-to-L3 priming of motion event (ME) constructions in L1 German learners of English (L2) and Italian (L3). This is a domain in which foreign language (FL) learners often have difficulties adapting to target language norms, especially when the preferential typological encoding patterns of source and target language differ. We adopted a pre-/post-test design to address the question of whether priming affects cross-linguistic awareness of the L3 target structure. This design allowed us to investigate whether and how L2 processing impacts L3 production and cross-linguistic awareness in the learners' L3. The results provide strong evidence that processing ME constructions in the L2 leads to activation of the relevant constructions in the target L3. Our findings provide less conclusive evidence for the occurrence of implicit learning. Concerning cross-linguistic awareness, a numerical trend suggests a weak improvement from the pre-test to the post-test, although no significant effect of priming intervention was found. Our findings indicate that targeted exposure to the L2 has a significant impact on learners' L3. We consider this as further evidence that previously acquired L2s can be used as a strategic resource in the acquisition of additional languages. These findings are thus relevant not only for psycholinguistic research but also for foreign language didactics.

1 Introduction

Evidence that previously acquired L2s can influence the acquisition of an L3 comes mostly from studies on cross-linguistic influence (CLI; e.g., Eibensteiner, 2023; Puig-Mayenco et al., 2020; Sánchez, 2020). However, other methods can be employed to investigate potential interactions between learners' L2 and L3 more directly, such as cross-linguistic priming (e.g., Hartsuiker et al., 2004). Priming studies have the potential to isolate the effects of processing specific L2 constructions on sentence production in the L3. Moreover, structural priming has been linked to different cognitive mechanisms, such as activation, implicit learning, and explicit memory processes. Investigating the effect of L2-to-L3 priming, thus, can help us detect whether these aspects of L2 processing impact L3 production and awareness. Moreover, some of the aforementioned mechanisms have been claimed to be directly or indirectly associated with learning. Thus, the investigation of L2-to-L3 priming effects can help us understand how previously acquired L2s can be used to foster L3 learning. Nonetheless, only one study to our knowledge has tested cross-linguistic priming from the L2 to the L3 (Hartsuiker et al., 2016). This study demonstrated that priming across foreign languages (FL) is possible. However, we are not aware of any studies that have replicated this finding. Moreover, it remains unclear whether the L2-to-L3 priming effects found are due to transient cross-linguistic activation of the primed structure or implicit learning and whether priming can affect not only learners' production, but also their awareness of the primed structure. These are the questions that the present study addresses.

In the present study we investigate L2-to-L3 priming of motion event (ME) constructions in L1 German learners of English (L2) and Italian (L3), a domain in which foreign language (FL) learners have been shown to demonstrate persistent difficulties in adapting to target language patterns (e.g., Laws et al., 2022; Michelotti and Engemann, 2025). Additionally, to investigate the effects of priming on learners' cross-linguistic awareness of ME encoding, we adopt a pre-/post-test design implementing a cross-linguistic awareness task. This design allowed us to test the effect of the L2 on different aspects of awareness and production in the L3 (activation, implicit learning, and cross-linguistic awareness).

1.1 Motion events and their acquisition in learners of typologically different languages

According to Talmy's (1983) typology, languages can be classified into two groups based on how they typically encode motion events (ME). Verb-framed (VF) languages, such as Italian, tend to encode Path of motion in the main verb and Manner of motion is usually encoded in the verbal periphery (1). Moreover, VF languages tend to omit the information of Manner of motion unless this information is crucial for communication purposes (Slobin, 2004; p. 9). On the other hand, in satellite-framed languages—such as German or English—Manner is typically expressed in the main verb whereas Path is usually encoded in so-called satellites (2). In this study, we consider as “satellite” both particles and prepositional phrases, in line with revised versions of Talmy's original proposal (Beavers et al., 2010) (see examples in 2).

(1) La ragazza esce dalla casa ballando

“The girl exits the house dancing”

(2a) Das Mädchen tanzt aus dem Haus.

“The girl dances out of the house.”

(2b) The girl dances out of the house.

Crucially, these patterns only represent preferences in motion encoding in specific languages. Despite being SF languages, English and German also allow the use of VF constructions (see examples in 3).

(3a) Das Mädchen verlässt tanzend das Haus.

“The girl leaves the house dancing.”

(3b) The girl exits the house dancing.

Similarly, VF languages allow the use of SF constructions, but, unlike SF languages, only in specific circumstances. SF constructions can be employed if no boundary crossing is implied in the expression of motion (4) (boundary-crossing constraint, henceforth BC, Slobin and Hoiting, 1994). SF constructions are, however, typically considered less acceptable in a BC context, although their acceptability can be modulated by the type of Manner verb used. For instance, directional Manner verbs such as correre “run” are more acceptable (5) than non-directional Manner verbs such as ballare “dance” (6) (see Hijazo-Gascón, 2021).

(4) La ragazza corre sulle scale

“The girl runs on the stairs”

(5) La ragazza corre fuori dalla casa

“The girl runs out of the house”

(6) La ragazza balla fuori dalla casa

“*The girl dances out of the house”

Given these typological differences, FL learners have difficulties adapting to the target language preferential pattern in the expression of ME constructions. For the scope of this paper, it is particularly relevant to highlight that several studies have found evidence of cross-linguistic influence (CLI) in the acquisition of ME in a VF language by learners of SF languages (Anastasio, 2023; Cadierno and Ruiz, 2006; Larrañaga et al., 2012; Song et al., 2016). Anastasio (2023), for instance, found that the mean percentage of SF constructions in which Path was expressed in directional particles (following the typical SF pattern) produced by advanced English-speaking (SF language) learners of Italian was higher compared to French-speaking (VF language) learners of the same target language.

Interestingly, there is evidence suggesting that even at high levels of proficiency learners do not completely adopt target-like ME framing (e.g., Larrañaga et al., 2012; Treffers-Daller and Calude, 2015). One of the reasons proposed for this difficulty is that the availability of both SF and VF structures makes it unlikely that learners will receive negative feedback when producing a dispreferred motion encoding pattern in the FL (Alghamdi et al., 2019). Nevertheless, several studies have also found that learners improve with higher levels of proficiency in at least some domains of ME expression (e.g., Song et al., 2016; Treffers-Daller and Calude, 2015). For instance, (Treffers-Daller and Calude 2015) found that the performance in a C-test (used as proxy for proficiency) by English learners of French was positively correlated with the number of correct (VF) boundary-crossing descriptions produced. However, not all aspects of ME encoding seem to be equally difficult to acquire. For instance, Larrañaga et al. (2012) found that learners at three different proficiency levels had difficulties producing utterances encoding Manner in an adjunct, whereas learners of all three levels successfully produced Path verbs. These findings align with Treffers-Daller and Calude's (2015) hypothesis that learners of VF languages easily adjust to the target language use of Path verbs as there is ample positive evidence for their use in the input, whereas they might have difficulties learning how to encode Manner, given the relatively low frequency of overall expression of this component in VF languages.

1.2 Priming, activation, implicit learning, and awareness

Structural priming can be defined as the speaker's tendency to repeat a given structure upon hearing it. Structural priming effects in production are usually investigated by exposing participants to sentences which present specific syntactic structures (prime sentences) and testing whether participants reuse these structures in their own production (target) shortly after. Usually, prime sentences present two alternative constructions which can be used to express the same semantic message. An example for this is the dative alternation in English: “The boy gives the letter to the girl” (prepositional object construction—PO) can also be expressed by saying “the boy gives the girl a letter” (direct object construction—DO; see Kootstra and Doedens, 2016; van Dijk and Hopp, 2025 amongst others). As mentioned in Section 1.1, this type of alternation is available also in ME encoding: the same message expressed by the VF construction “the boy enters the house running” can be conveyed by the SF construction “the boy runs into the house.” Nonetheless, priming of ME has been investigated in relatively few studies (Bunger et al., 2013; Montero-Melis et al., 2016; Montero-Melis and Jaeger, 2020) and only one study to date has investigated priming of ME across languages (Baroncini et al., 2025).

Priming effects, in fact, have been found not only when prime and target share the same language (within-language priming) but also when the language of prime and target differs (across-language priming). Within-language effects have been demonstrated also from L2 to L2 (e.g., Jackson and Hopp, 2020; McDonough, 2006; Shin and Christianson, 2012) providing evidence that priming effects do not only occur in the speaker's L1. Moreover, across-language priming effects have been reported across several language combinations: for instance from L1 to L2 (Hartsuiker et al., 2004; van Dijk and Hopp, 2025), and from L3 to L1 (Huang et al., 2019), showing that priming can occur across languages which differ in the way they have been acquired (first language acquisition vs. foreign language acquisition). However, as far as we know, only one study has investigated and detected across-language priming effects from L2 to L3 (Hartsuiker et al., 2016), providing evidence that priming effects can occur across two foreign languages.

Different models have been developed to explain the mechanisms underlying priming. On the one hand, the residual activation account (Pickering and Branigan, 1999) argues that priming results from the activation of specific structures (combinatorial information) during sentence processing which influences subsequent processing or production. On the other hand, the dual-path model (Chang et al., 2006) proposes that priming results from error-based learning mechanisms: speakers' mismatch between the expected input and the received input leads to changes in the speakers' linguistic expectations which in turn leads to implicit learning. While both the residual activation and the implicit learning theories can account for immediate priming effects, only the implicit learning theory successfully accounts for two other effects that occur during priming: the so-called surprisal effect (also called inverse frequency effect) and cumulative priming effect (e.g., Jaeger and Snider, 2013).

The term “surprisal effect” refers to the well-documented tendency by which exposure to infrequent and thus less expected structures leads to stronger priming effects (e.g., Hartsuiker and Westenberg, 2000; van Dijk and Hopp, 2025). This effect is predicted by the implicit learning account which conceptualizes priming as a result of a change in linguistic expectation (Chang et al., 2006, p. 263). The implicit learning account can also explain the occurrence of cumulative priming effects, i.e., the gradual increase in the production of a primed structure as a function of accumulated exposure to the target structure within a task, regardless of the immediately preceding prime (e.g., Kaan and Chun, 2018; Kaschak et al., 2012). This effect is predicted by the implicit learning account according to which structural priming should be long-lasting (Kaschak et al., 2012, p. 729).

Despite their differences, both accounts agree that the mechanisms underlying priming are automatic and unconscious. Nonetheless, there are also explicit mechanisms that can influence priming (e.g., Kootstra and Muysken, 2019): the “lexical boost effect” is considered to be one of them. This is a well-established finding in the priming literature whereby the magnitude of priming tends to be stronger when lexical material is repeated between prime and target. Crucially, it has been argued that this mechanism is linked to explicit memory processes: repeated lexical material can act as a memory cue which will reinforce the tendency to repeat the structure presented in the prime (Chang et al., 2006; Scheepers et al., 2017). Thus, when prime and target share the same lexical materials, explicit memory processes are also at play. Kootstra and Muysken (2019) argue that the surprisal effect is also linked to explicit mechanisms. They argue that the concept of “surprisal” entails some level of enhanced attention toward the unexpected (and in that sense surprising) structure. In this sense, surprisal can be considered equivalent or closely related to the concept of “salience”—the property of a structure to be perceived and distinguished from its environment (Ravid, 1995; p. 117)—which, in turn, leads to awareness, “in the sense that salient linguistic elements lead to higher levels of awareness” (Kootstra and Muysken, 2019, p. 11). Evidence that priming can involve explicit processing comes also from experimental studies (e.g., Ivanova et al., 2020; McDonough and Fulga, 2015; Shin and Christianson, 2012). For instance, Ivanova et al. (2020) fond that participants who paid more attention to the priming task showed stronger priming effects suggesting that conscious mechanisms such as attention can have an impact on priming. Interestingly, Shin and Christianson (2012) also found that a priming intervention had a marginally significant positive effect on learners' performance on a grammaticality judgement task, whereby the participants' performance improved in the post-test compared to the pre-test. Although this result was only marginally significant, this trend at least indicates that priming interventions may have a positive impact not only on learners' language production abilities but also on more explicit tasks which require metalinguistic awareness.

Despite the above findings on the role of explicit processes in priming, existing L2 research has investigated priming and its connection to language learning mainly in terms of implicit learning. In this research domain several studies have tested whether priming effects can last beyond the priming task and whether priming can be used as a learning intervention in L2 learning contexts (Bencini, 2025; Jackson, 2018). Several studies have found evidence that the effects of priming are detectable after the priming task and do indeed transfer to production post-tests (e.g., Coumel et al., 2023; Jackson and Hopp, 2020; McDonough, 2006; Shin and Christianson, 2012). Such longer-term effects were found with respect to several structural alternations, such as passives vs. actives and the dative alternation. Crucially, these effects have been considered as evidence that priming conceptualized as implicit learning could be the cognitive mechanism behind language learning itself (e.g., Coumel et al., 2023; Grüter et al., 2021). Nonetheless, adopting an activation-based view of priming can also open interesting implications for language learning. It has in fact been argued that activation of shared linguistic structures across languages might be the psycholinguistic mechanism underlying CLI (e.g., Serratrice, 2022) and several studies have shown how CLI can positively impact L3 acquisition (e.g., Aribaş and Cele, 2021). Thus, the investigation of priming both in terms of implicit learning and transient activation can help us understand the cognitive mechanism behind language learning.

1.3 Cross-linguistic awareness, metalinguistic knowledge, and noticing

Cross-linguistic awareness can be defined as learners' awareness of connections between the languages of their linguistic repertoire (Jessner, 2006; p. 116). According to (Angelovska and Hahn 2014, p.187) this ability is developed by “focusing attention on and reflecting upon language(s) in use and through establishing similarities and differences among the languages in one's multilingual mind.” (Angelovska 2018, p. 137) also underlines the fact that cross-linguistic awareness is strictly connected with metalinguistic awareness (see also Jessner, 2006, p. 116 for a similar claim). Thus, like metalinguistic awareness, cross-linguistic awareness is characterized by a complex interplay between metalinguistic awareness, metalinguistic knowledge and metalanguage.

Adopting Sharwood Smith's (2008, p. 181) definition, metalinguistic awareness can be defined as a mental ability which allows learners to reflect on linguistic patterns they have noticed through a heightened and sustained degree of awareness. In contrast, metalinguistic knowledge refers to a more explicit construct and reflects verbalized metalinguistic awareness (Angelovska, 2018; p. 137). In order to express this knowledge learners will often need to use metalinguistic terms (e.g., metalanguage). Metalinguistic awareness and knowledge are interconnected, but, crucially, they are not the same. This is evidenced, for instance, by the fact that learners who are able to identify and correct errors are not necessarily able to verbally explain the rationale behind their correction (e.g., Sorace, 1985).

Cross-linguistic awareness, thus, does not necessarily result in verbalized knowledge. However, this leaves us with the question of how awareness can be defined and measured. According to Schmidt (1990), it is possible to distinguish between different degrees of awareness. Crucially for this paper, he mentions “noticing” as a level of this awareness “scale.” Noticing is usually defined as “paying attention to specific linguistic features of the input” (e.g., Ellis, 2017; p. 117) and as such it seems closely related to at least a part of Angelovska and Hahn's definition of cross-linguistic awareness [“focusing attention […] on languages in use” (Angelovska and Hahn 2014, p.187)]. As it emerges from these definitions, the process of paying attention—and thus noticing—is a subjective experience (Schmidt, 1990; p. 132), which makes an external, objective measure of noticing—and thus of awareness—difficult to implement. Quantitative measures of noticing have been developed in studies investigating the effectiveness of input enhancement. For instance, Cho (2010) adopted the following noticing task: students were given a text containing instances of the investigated structure and were asked to circle or underline any and every grammar or content word that they noticed. They were also asked to take notes for a recall summary task in which the accuracy and grammar of the reconstructed sentences were of great importance. Noticing was then measured as the number of total words in the notetaking activity divided by the number of noted words related to the investigated structure. A similar measure of noticing was adopted also by Izumi (2002).

Cross-linguistic awareness, however, does not only refer to attentional mechanisms and noticing. Angelovska and Hahn's (2014, p.187) definition of cross-linguistic awareness also underlines the importance of the ability to reflect and establish “similarities and differences among the languages in one's multilingual mind.” As reflection is an introspective process, it follows that it is difficult to assess this aspect of cross-linguistic awareness without at least in part tapping into learners' metalinguistic knowledge and ability to use metalanguage. Only a few studies have attempted to directly assess this aspect of cross-linguistic awareness. For instance, Angelovska (2018) adopted semi-structured interviews in which learners' written production was used as prompt for a language reflection session. Sheppard (2021), instead, developed a “spot the differences” test in which learners were exposed to the same sentence in four different languages and were asked to report any similarities or differences they could find. Grammaticality judgment tasks have also been used to assess learners' cross-linguistic awareness (e.g., Abel-Hardenberg et al., 2025); however this type of task is difficult to implement in the context of ME, where typological differences are not categorical and both VF and SF constructions are in principle possible.

Studies which investigate how cross-linguistic awareness can be enhanced and trained often highlight the beneficial role of tasks which engage learners in contrasting one (or more) languages. Jessner et al. (2016, p. 168) highlight that knowledge of previously acquired languages can benefit the acquisition of additional languages only when it is made explicit through language comparisons. They also list several activities that can help foster cross-linguistic awareness and, crucially, all focus on the comparison between languages: “comparing prefixes and suffixes across languages; looking for supporter languages for a specific structure; finding cognates across languages; and comparing sounds, orthography, and pronunciation.” (Jessner et al., 2016; p. 169). Notably, all these activities require explicit reflection on language.

Studies implementing activities to enhance cross-linguistic awareness most typically include a phase which fosters explicit reflection on the languages spoken by learners. For instance, Irsara (2022) implemented a cross-linguistic awareness intervention with South Tyrolean speakers of Ladin who learned English as a fourth language after Italian and German. In this task, the participants were encouraged to make explicit comparisons between Ladin, Italian, German and English expressions. Another example is the study by Woll and Paquet (2025). Here, the authors developed a didactic method called “plurilingual consciousness-raising task” (“PluriL-CRT”). The main task consists of learners accessing their multilingual repertoire to extract patterns and rules concerning the target structure. Nonetheless, the enhancement of cross-linguistic awareness through incidental learning has also been investigated. Abel-Hardenberg et al. (2025) have tested the awareness of positive transfer possibilities concerning word order in subordinate clauses from learners' L1 (Dutch) to their L3 (German). They found that an implicit intervention in which learners were exposed to L1 and L3 subordinate clauses made salient by the use of typographic input enhancement led to positive results in an immediate post-test. Our study contributes to this line of research, by investigating whether cross-linguistic awareness can be enhanced through simple exposure to different languages, fostering incidental metalinguistic reflections rather than explicit ones.

1.4 The present study

In the present study we aim to investigate whether processing of ME constructions in an L2 can influence the production and awareness of these constructions in the L3. In order to do so, we have adopted the structural priming methodology. The fact that priming has been shown to be linked to (a) the activation of linguistic representations, and (b) implicit learning, allows us to also investigate the underlying mechanisms whereby L2 processing affects L3 production.

We designed an L2-to-L3 (English to Italian) priming experiment in which primes and targets share the same lexical material (lexical repetition) and tested German (SF language) learners of English (SF language) as an L2 and Italian (VF language) as an L3. This task allowed us to test both immediate and cumulative priming effects. In particular, based on an implicit learning account of priming, we expect priming effects to be stronger for the less frequent construction. Since participants are exposed to English primes and English is a SF language, we expect a stronger and more long-lasting effect of English VF primes than of SF primes on learners' Italian target productions. It is worth noting that this hypothesis is based on the assumption that L3 learners are sensitive to the input frequency distribution in their L2 (English). Nonetheless, the expected direction of the cumulative priming effect would be the same even if participants based their linguistic predictions on their L1 (German), which is also classified as a typical SF language.

Crucially, we also adopted a pre/-post-test design testing the effects of the priming intervention on cross-linguistic awareness of ME. The reason why we believe that cross-linguistic priming might have a beneficial effect on cross-linguistic awareness is that previous literature has highlighted the crucial role of activities fostering learners' comparisons between different languages for its development. Even if in the present priming task participants are not prompted to explicitly reflect on language, they are exposed to the same construction in one language when they process the prime and in another language when they (possibly) produce that same structure in the target. We believe that this targeted exposure combined with the explicit memory/attentional mechanism related to the lexical repetition between prime and target could lead participants to notice and become aware of the primed structure.

Our research questions, hypotheses and predictions, therefore, are the following:

RQ1: Does L2 processing lead to changes in L3 production?

If that is the case, we expect to find immediate priming effects from the L2 to the L3 whereby participants produce more VF constructions after an L2 VF prime than after an L2 SF prime or a neutral prime at the beginning of the task (baseline—henceforth BL). Crucially, these effects could be explained both in terms of transient cross-linguistic activation of the primed structure across languages and implicit learning.

RQ2: Is the mechanism underlying changes in L3 production implicit learning?

If that is the case, we expect to find cumulative priming effects whereby the use of the less-frequent VF constructions would increase as the priming task progresses.

RQ3: Can priming lead to increased cross-linguistic awareness of the primed structure?

If that is the case, we expect participants to become implicitly (noticing) and/or explicitly (explicit declarative knowledge) more aware of the primed structure in a cross-linguistic awareness task after the priming intervention (post-test) compared to before the priming intervention (pre-test).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

Forty adult L31 learners of Italian were tested (23 females). Six participants were excluded because they grew up either with Italian or English as a first language. The participants included in the analysis (n = 34) were all native speakers of German. Four of them grew up with an additional language which was neither English nor Italian.2 Detailed information about the participants' profile can be found in Table 1. Informed written consent was collected from all participants before conducting the study.

2.2 Lexical familiarization task

Participants completed a written picture-word matching task in which they had to select between two images the one that matched the meaning of the given word. The aim of this task was to familiarize participants with the Italian Manner verbs used in the priming task. No Path verbs nor Path particles were included in this task. In total, participants read 23 words and saw 23 images which were presented once as target and once as distractor.

2.3 Priming task

The priming experiment was conducted as a written picture description task. In the priming phase, participants were exposed to a written English prime sentence (e.g., “A person runs down the ramp”) and completed a sentence-picture matching activity in which they had to select between two images the one that matched the meaning of the English prime sentence. Then, they were presented with a target picture and were asked to describe it in writing in Italian (for an example of a trial, see Figure 1).

The experimental items consisted of 24 prime-target pairs.3 The experimental targets always depicted a motion event. Half of them depicted a boundary-crossing event (Paths: into, out of) and the other half a non-boundary-crossing one (Paths: up, down). These four Paths were crossed with six different Manners (jump, fly, run, dance, skate, and limp). The experimental targets were always preceded by a target and distractor picture paired with a prime sentence which either presented a ditransitive event (BL), a VF structure or a SF structure. Crucially, when the prime presented a ME, prime and target always matched for Path and Manner with the target image (lexical repetition).

The prime sentence was always accompanied by two pictures: one which visually represented the prime sentence and a distractor. When the prime presented a ME, the two pictures only differed in the Path they depicted. This way we made sure that participants had to process the information concerning Path of motion expressed by the prime sentence. The target images were always presented with the Italian word for the ground entity depicted in the given image to help participants in their description.

Three lists were created, so that participants could see the same number of BL, VF and SF primes (eight items per condition), but only one version of each item. In each condition (BL, VF, and SF prime), half of the items depicted boundary-crossing events and half of them non-boundary-crossing events. The items were presented in three blocks. In the first block, participants were only exposed to BL primes; this allowed us to test participants' unprimed production preferences. In the second and third block, participants were exposed to either VF or SF primes, which alternated within the second and third block. A full list of the experimental items can be found in the Supplementary Appendix S1.

In addition, 24 fillers were created. They consisted of 24 prime-target pairs. The target pictures always depicted a transitive event (e.g., showing a ball hitting a wall) and were preceded by a prime sentence which either presented an intransitive, active, or passive structure (e.g., “The woman gives a banana to the boy.”/“The ball hits the football player.”/“The football player is hit by the ball.”). The prime sentence was always accompanied by two pictures: one which visually represented the prime sentence and a distractor. Target images were presented together with the Italian words for the agent and the patient depicted in the picture to aid learners' verbalization.

2.4 Cross-linguistic awareness task

Participants were administered a cross-linguistic awareness task twice: once before the priming experiment (pre-test) and once after it (post-test). The aim of this task was to test whether participants' metalinguistic awareness of ME improved after the priming phase.

During the task participants read Italian sentences and their corresponding translation in English. They were told that each translation pair expressed the same meaning but also presented some differences. Participants were then asked to note down the parts of the sentence which, in their opinion, showed differences between the two languages and to explain how they thought they differed. Participants were allowed to mark and circle words on the screen (for an example of a trial, see Supplementary Appendix S2).

Six translation pairs were created. Each translation pair presented two motion events. All Italian motion events expressed Path through the main verb (e.g., entrare “enter”), whereas all the corresponding English translations expressed Path through a generic motion verb (“go”) or a Manner verb (“climb”) followed by a Path satellite. To make sure that any changes in the performance from the pre- to the post-test were due to the priming exposure and not to general learning effects, we included a control structure which differs structurally between Italian and English, but was not included in the priming phase: Italian clitics (e.g., chiamarlo vs. “to call him”) and reflexive verbs (e.g., annunciarsi vs. “to announce onself”).

The six sentence-pairs were divided into two lists. The order of the lists was counterbalanced to make sure that differences between pre- and post-test were not due to differences in the difficulty of the sentences included in the two lists.4 A full list of the experimental items can be found in the Supplementary Appendix S3.

2.5 Background questionnaire

All participants completed the LEAP-Q questionnaire (Marian et al., 2007) which provides detailed information concerning learners' linguistic profile, including their acquisition of Italian, English and other L2s. A measure of proficiency in Italian and English was calculated as the average of the self-reported ratings in reading, listening and speaking in these languages (see also Treffers-Daller and Calude, 2015, p. 615).

2.6 Debriefing questionnaire

A debriefing questionnaire was administered at the end of the experiment to investigate whether participants had become aware of the structure tested in the experiment. First, participants were asked whether they had noticed any specific pattern during the cross-linguistic awareness task or the priming task. If that was the case, participants were asked to describe the pattern they had noticed and to state at which point of the task they had become aware of it. They were also asked whether they had developed any specific strategies in their answers during the experiment. Finally, participants were asked whether they had noticed any patterns concerning how motion was expressed in the sentences they had read in the experiment.

2.7 Procedure

Participants were recruited via flyers distributed through language schools, university language centers, and personal contacts. After contacting the experimenter via email, participants received detailed information on the study and the link to access the experiment. The experiment was conducted online via the platform Gorilla (www.gorilla.sc) and lasted about an hour. All participants provided informed written consent before the beginning of the study and received a 10€ voucher for their participation.

After completing the consent form, participants were assigned to one of the two cross-linguistic awareness tasks (pre-test). Before the beginning of the task, participants watched a video example showing them how to circle/underline words and to note down the linguistic differences in the experimental platform and completed one practice trial. The presentation of the items was timed so that participants had three minutes for each item. This time limit was implemented to limit differences in the time participants take to reflect on each trial between the pre- and post-test. Participants then completed the lexical familiarization task and were assigned to one of the three lists of the priming task. Before the beginning of the task participants completed two practice trials. The presentation of both prime and target sentences was timed so that participants had 15 s to read the prime sentence and 25 s to type a description of the target. This time limit was implemented to favor spontaneity in the participants' answers and to limit the possibility of them resorting to translation tools. Moreover, the order of the items was pseudorandomized so that each experimental item was followed by a filler. After completing the priming task, the participants completed the second cross-linguistic awareness task (post-test), which was always different from the one they were assigned in the pre-test. Finally, they completed the background and debriefing questionnaire.

2.8 Coding priming task

All sentences were automatically coded using a Python (https://www.python.org) script developed by the first author (see also Michelotti et al., 2025). The output of the script was then manually checked by two native speakers of Italian, and any diverging coding decisions were discussed. If more than one sentence was produced to describe one experimental video, the sentence expressing the highest number of semantic components concerning motion was analyzed (following the richness criterion, see Hickmann et al., 2022). If the richness criterion could not be applied, we analyzed the first sentence produced, as we considered it the most spontaneous answer. For the statistical analysis, sentences were coded for the type of framing they presented as either “VF,” “SF” or “other.” For the purpose of this study, we included in the analysis only sentences which encoded both Path and Manner information, since we assumed based on previous literature (see Section 1.1) that these were the contexts in which learners might have more difficulties adapting to the target language, whereas they might already master the target encoding of Path in isolation (Larrañaga et al., 2012; Treffers-Daller and Calude, 2015). Moreover, this criterion allowed us to include in the analysis only sentences which structurally resembled the given prime sentences. Thus, we coded as VF all sentences which encoded Path in the main verb and Manner in the verbal periphery, and as SF all sentences which encoded Manner in the main verb and Path in a satellite or subordinate clause (see Supplementary Appendix S4). This resulted in the exclusion of 360 utterances yielding a total of 456 data points.

2.9 Coding: cross-linguistic awareness task

For each experimental item, we assigned points for “noticing” and “explaining” the differences in the use of ME (target structure) and clitics/pronouns (control structure) in English and Italian applying the following criteria. Participants were assigned one point for “noticing” a ME each time they either noted down and/or underlined at least one of the following elements: (i) the Italian Path verb (e.g., scende), (ii) the English generic verb (e.g., “go”), or (iii) the English Path satellite (e.g., “up”). Participants were assigned one point for “explaining,” each time they provided a linguistically valid explanation of how the ME construction in Italian differed from English, even if the explanation was not directly related to Talmy's classification. For instance, explanations related to the different number of words needed in Italian and English to express the same concept were also accepted, as they showed that participants were aware of the fact that the two languages used different forms (one vs. two words) to express the same meaning (e.g., scende = one word vs. “go up” = two words). For the control structure (clitics and reflexives), participants were assigned one point for “noticing,” if they either noted down and/or underlined at least one of the following elements: (i) the Italian infinitive + clitic, (ii) the English base form, or (iii) the English pronoun. Since in each experimental sentence participants were presented with two motion events and two control structures, participants could reach a maximum of two “noticing” and two “explaining” points per structure for each item. As participants saw three experimental items per task, the highest score for both the experimental and control structures was six points for “noticing” and six points for “explaining.” If it was clear from the participants' explanations that they had written down or underlined a target or control structure due to noticing of another linguistic phenomenon, we did not assign a noticing point (e.g., participants noted sul tavolo, “onto the table” with the explanation: “in English there is an article”). More detailed information on the coding procedure can be found in Supplementary Appendix S5.

2.10 Statistical analysis: priming task

To analyze the priming data, we built two generalized mixed effects models (GLMM; package lme4 version 1.1-34, Bates et al., 2015) using R (version 4.4.0, R Core Team, 2023). The dependent variable was the use of VF (1) and SF (0) constructions. The aim of the first model (m1) was to investigate the occurrence of immediate priming effects (RQ1). This model included Prime Type as a categorical predictor (VF, SF, and BL) to which treatment coding was applied. VF was chosen as a reference level in order to test the difference between participants' performance after being exposed to VF primes compared to when being exposed to a SF prime and their performance during the BL. The aim of the second model (m2) was to investigate whether cumulative priming effect occurred during the priming task (RQ2). For this reason, only utterances produced after either a VF or a SF prime were included in the analysis, whereas the utterances produced in the BL phase were excluded. This model included Prime Type as a categorical variable (VF = 0.5 vs. SF = −0.5) and Trial Number as a numerical predictor, which was centered prior to the analysis. The results of a simulation-based power analysis based on Baroncini et al.'s (2025) priming data using the package mixedpower (Kumle et al., 2021) indicated 99% power for the priming effect and 87% power for trial number for m2 (see Supplementary Appendix S6).

For both models we specified the maximal by-subject and by-item random effect structure with a random intercept for participants and item, by-subject random slopes for all the within-participant variables (m1: Prime Type; m2: Prime Type and Trial Number) and by-item random slopes for all the within-item variables (m1: Prime Type; m2: Prime Type and Trial Number; following Coumel et al., 2023, p. 246). If the model did not converge, we removed the random slope which explained the least variance (following Gries, 2021; p. 421) until reaching convergence. More detailed information on model structure and selection can be found in Supplementary Appendix S7.

While running these analyses, some unexpected results emerged (see section 3.1). In order to further investigate these unexpected trends, we ran additional exploratory analyses. To further investigate the results of the first model (m1), we modified the applied contrast to the Priming Type variable to test whether participants' production differed between when they were exposed to a SF prime and the BL (reversed Helmert coding). Additionally, we tested whether participants' self-reported English and Italian proficiency modulated the effects investigated. In order to do so, we included these variables and their interaction with the variables of interest in the models (m1: Prime type; m2: Trial number). Before doing so we checked that this measure did not correlate with each other to avoid collinearity issues (see Supplementary Appendix S8). The model structure and selection criteria were the same as described above, but we also performed backward model selection of the fixed-effect structure using p-values as a model selection criterion (see Gries, 2021, p. 366). The results of these additional analyses can be found in the Supplementary Appendix S9–S11, respectively.

2.11 Statistical analysis: cross-linguistic awareness task

To analyze the data of the cross-linguistic awareness task, we built two linear mixed effects models (LMMs; package lme4 version 1.1-35.3, Bates et al., 2015) using R (version 4.4.0, R Core Team, 2023). The aim of the first model was to investigate whether participants' noticing of ME increased after being exposed to priming of ME (RQ3). For this model, we used the number of points assigned for noticing during the cross-linguistic awareness task as the dependent variable. The aim of the second model was to investigate whether participants' ability to explain the difference between Italian and English ME increased after being exposed to priming of ME (RQ3). In this model the number of points assigned for explaining during the cross-linguistic task was used as dependent variable. Both models included the categorical variables Task (Pre-test = −0.5, Post-test = 0.5) and Structure (Clitics, i.e., control structure = −0.5, ME i.e., target structure = 0.5) and their interaction as fixed effects. For both models we specified the maximal by-subject and by-item random effect structure with a random intercept for participants and item, by-subject random slopes for all the within-participant variables (Task and Structure) and by-item random slopes for all the within-item variables (Task; following Coumel et al., 2023, p. 246). If the model did not converge, we removed the random slope which explained the least variance (Gries, 2021, p. 421) until reaching convergence (more detailed information on model structure and selection can be found in Supplementary Appendix S12). We decided not to report any exploratory analyses testing whether Italian or English proficiency modulated the effects of interest: an analysis of this kind would have necessarily included three-way interactions for which, due to the limited number of data points of our data set (n = 408), the model lacked sufficient statistical power.

2.12 Descriptive analysis: debriefing questionnaire

In addition to the analyses reported above, we carried out a qualitative exploratory analysis of participants' answers to the debriefing questionnaire, to obtain more detailed information on participants' noticing of the primed structure. We analyzed the answers to the debriefing questionnaire by noting whether participants noticed (i) structural or (ii) semantic aspects of ME, or (iii) both. When participants mentioned the use of specific linguistic devices such as gerunds, -ing forms or the use of prepositions, we classified their answers as referring to structural aspects of ME. We classified participants' answers as referring to semantic aspects of ME if they only mentioned having noticed the presence of sentences expressing movement. We then analyzed in more detail the answers of the participants who noticed structural aspects of ME and classified them based on whether they had noticed the use of (i) gerunds, (ii) satellites, or (iii) both (See Table 13.1 in Supplementary Appendix S13 for examples).

3 Results

3.1 Priming task

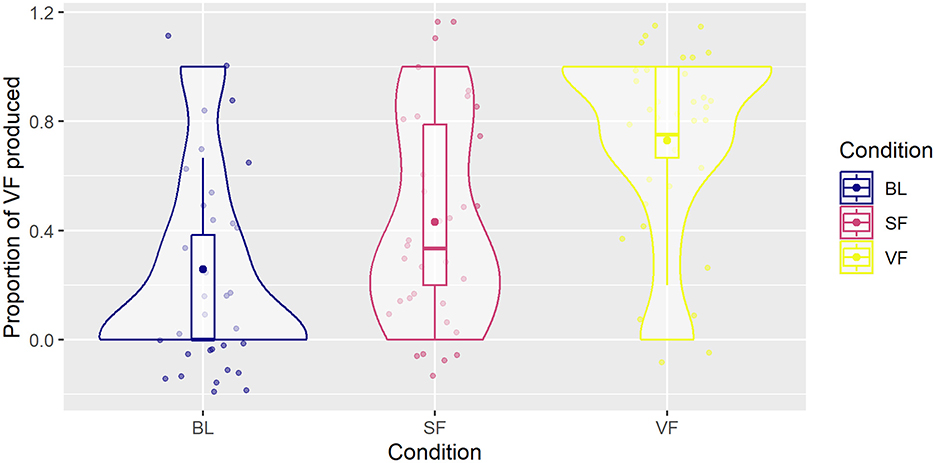

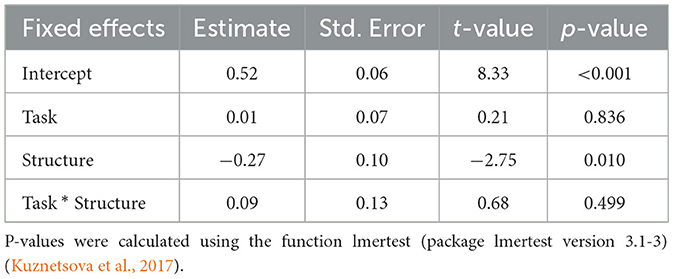

A descriptive analysis of the data revealed that during the BL phase, participants produced more SF constructions (0.74) than VF constructions (0.26), confirming claims in the previous literature that learners of a VF language whose native language is SF have difficulties adapting to ME framing patterns of the target language. Moreover, the proportion of VF constructions produced was higher after being exposed to a VF prime (0.73), than after being exposed to a SF prime (0.43) or during the BL (0.26; see Table 2 and Figure 2). These trends were confirmed by the results of the first GLMM which revealed a significant effect of Prime Type (p < 0.001; Table 3). Interestingly, the results of the descriptive statistics seemed to suggest that the proportion of VF produced was higher after reading a SF prime (0.43) than in the BL (0.26). To test whether this trend was significant we ran an exploratory analysis changing the contrasts applied to the variable Prime Type (reversed Helmert coding—for more detailed information on the model see Supplementary Appendix S9). The model confirmed this initial observation yielding a significant effect of priming type (SF vs. BL—p = 0.016). This result suggests that exposure to SF primes not only did not result in a higher production of SF compared to the BL—as one would expect if exposure to SF primes led to priming of SF construction—but also that the effect of VF primes persisted across conditions. The results of an additional exploratory analysis revealed that this effect was not modulated by either Italian or English proficiency. However, it yielded a significant main effect of Italian proficiency (p < 0.001) suggesting that more proficient Italian learners generally produced more VF constructions independently of the prime condition they were exposed to (Supplementary Appendix S10). The persistent effect of VF primes across conditions is compatible with cumulative priming. However, both visual inspection of Figure 3 and the results of model two (Table 4) do not support this hypothesis, since the effect of Trial Number was not significant (p = 0.497). The result of an additional exploratory analysis revealed that neither Italian nor English proficiency significantly modulated this effect (Supplementary Appendix S11).

Figure 2. Proportion of VF produced by each participant. The plot shows the distribution, quartiles, interquartile range and mean of the data for each priming condition.

Table 3. Parameters of the generalized linear mixed-effects analysis of the likelihood of producing a VF construction as a function of type of prime type (prime_type1 = VF vs. SF; prime_type2 = VF vs. BL).

Figure 3. Proportion of VF produced across trial number in each condition excluding the baseline phase.

Table 4. Parameters of the generalized linear mixed-effects analysis of the likelihood of producing a VF construction as a function of type of prime type and trial number.

3.2 Cross-linguistic awareness task

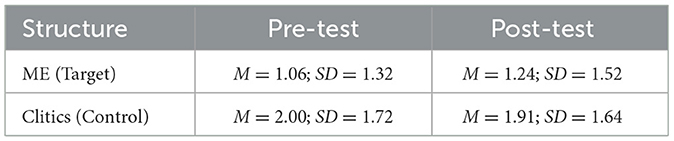

A descriptive analysis of the data revealed that participants tended to notice clitics (control structure) more than ME (target structure) both in the pre-test and in the post-test: on average participants obtained 2.41 and 2.38 points for noticing the control structure in the pre- and post-test respectively, whereas they obtained only 1.41 and 1.59 points for noticing the target structure (ME) in the pre- and post-test respectively (Table 5). The result of model one (Table 6) confirmed this initial observation, revealing a significant main effect of Structure (p = 0.002). Moreover, as can be seen from both Table 5 and Figure 4, participants seemed to have noticed slightly more ME in the post-test than in the pre-test, whereas they showed a slight trend in the opposite direction for the control structure. However, the results of the statistical model revealed this effect to be non-significant (p = 0.612).

Table 5. Mean and SD of the obtained “noticing” points for the control and target structures (ME) across tasks (pre-test vs. post-test). Participants could maximally obtain six points in each condition.

Table 6. Parameters of the linear mixed effects model analysis of the “noticing” points obtained across structure (ME vs. clitics), task (pre vs. post-test) and their interaction.

Figure 4. Mean of the points obtained for noticing clitics (control structure) and ME (target structure). The error bars represent 95% confidence interval.

Similar trends can be observed when analyzing the data concerning participants' ability to explain linguistic differences between English and Italian. Participants seem to have less difficulties explaining the differences between the use of clitics and pronouns than the differences related to the expression of ME (Table 7). The results of the second model (Table 8) revealed this trend to be significant (p = 0.010). From a visual inspection of Figure 5, we can also see a slight improvement in the participants' ability to explain the differences between ME expression in English and Italian from the pre- to the post-test and a slight trend in the opposite direction for the control structure. However, this trend was not found to be significant (p = 0.499).

Table 7. Mean and SD of the obtained “explaining” points for the control (clitics) and target structures (ME) across tasks (pre-test vs. post-test). Participants could maximally obtain six points in each condition.

Table 8. Parameters of the linear mixed effects model analysis of the “explaining” points obtained across structure (ME vs. clitics), task (pre vs. post-test) and their interaction.

Figure 5. Mean of the points obtained for explaining differences in clitics/pronouns (control structure) and ME (target structure) between Italian and English. The error bars represent 95% confidence interval.

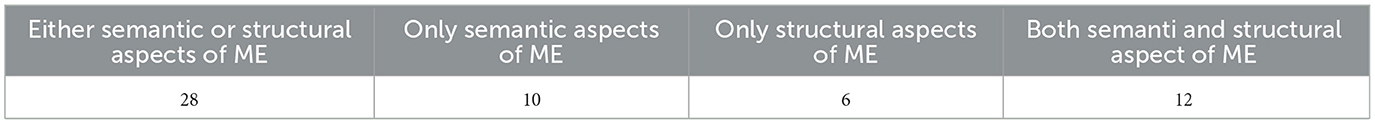

3.3 Descriptive analysis: debriefing questionnaire

The results of the qualitative analysis of the debriefing questionnaires (Table 9) suggest that most participants noticed the use of ME during the experiment. Twenty-eight participants out of thirty-four (82%) mentioned noticing either semantic (n = 10), structural (n =6) or both (n = 12) aspects of ME encoding during the experiment. Those who noticed structural aspects of ME encoding noticed either the use of gerunds (n = 11), the use of satellites (n = 2) or both (n =5; Table 10).

Table 9. Number of participants who mentioned in the debriefing questionnaire noticing either semantic or structural aspects of ME during the experiment.

Table 10. Number of participants who mentioned noticing the use of gerunds, satellites or both during the experiment.

4 Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether processing of ME constructions in the L2 affects the production and awareness of the primed structure in the L3. Crucially, the mechanisms underlying changes in L3 production (transient activation vs. implicit learning) were also investigated. To this aim we administered a L2-to-L3 (English to Italian) priming experiment with a pre-/post-test design testing the effects of the priming intervention on cross-linguistic awareness of the target structure. We hypothesized that processing of ME constructions in the L2 would lead to changes in the production of these constructions in the L3 resulting in immediate priming effects (RQ1). If the mechanism underlying these changes is implicit learning, we would expect cumulative priming effects to emerge, whereby participants would produce more VF constructions as the task progresses (RQ2). We finally hypothesized that the targeted exposure to ME in both the L2 (prime) and L3 (target) during the priming task would lead to either more implicit (noticing) or more explicit (explicit declarative knowledge) cross-linguistic awareness of ME in these two languages (RQ3).

Concerning our first research question, we suggest that the results of the current study provide evidence that processing of ME constructions in the L2 does indeed lead to changes in the production of ME constructions in the L3. As hypothesized, in fact, we found significant immediate priming effects whereby participants produced more VF constructions after a VF prime than after a SF prime and during the BL phase. Immediate priming effects can be explained by both the residual activation and the implicit learning account. We thus conclude that the effects found indicate at least activation of the primed structure across languages from the L2 to the L3. Importantly, since participants read the prime in English and wrote the target description in Italian, the effects found cannot be due to simple repetition, since the lexical material used in primes and targets was never identical.

Concerning our second research question, we did not find evidence for the expected pattern of cumulative priming. We expected the use of the less frequent VF construction to increase as the tasks progressed due to changes in linguistic expectation caused by the high exposure to infrequent English VF constructions during the priming task (50% of the primes were English VF constructions). However, the results of the statistical model revealed no significant effect of trial number, suggesting that participants' VF production did not significantly increase as the priming task progressed. Does this mean that we found no evidence of implicit learning? We believe that the answer to this question needs to be more than a simple no.

It is true that our initial hypothesis that the use of the less frequent VF construction would increase as the task progressed was not borne out. However, the results of one of our exploratory analyses revealed an unexpected effect that could be interpreted as cumulative priming. Visual inspection of the data and the results of the statistical model revealed that participants tended to produce more VF constructions after being exposed to SF primes when compared to the initial BL. This suggests that the impact of VF primes persisted across conditions influencing participants' overall performance during the priming task. In other words, VF primes had a long-lasting effect which persisted over and above the immediate effect between prime and target. A similar effect was detected by Muylle et al. (2021). They found that exposing participants to a PO-biased artificial language resulted in an overall increased production of PO constructions, whereas exposure to a DO-biased artificial language resulted in a generally increased production of DO constructions. They interpreted this trend as an effect of cumulative priming. The long-lasting effect of VF primes we found is predicted by the implicit learning account and could, thus, be interpreted as evidence of implicit learning. Notably, the effect goes in the direction predicted by the implicit learning account of priming: since in English, VF constructions are considerably less frequent than SF constructions they are expected to lead to prediction errors which in turn lead to implicit learning.

However, even if the effect we found is more long-lasting than immediate priming effects, it still is relatively short-lived. As such, the occurrence of implicit learning is not the only possible explanation for it. It is possible, for instance, that explicit mechanisms were at play. Although VF and SF constructions convey the same message, they are visually and structurally very different. For once, VF constructions are longer than SF constructions. Length can have an impact on a structure's saliency and, in turn, saliency can impact learners' processing and learning (Knell et al., 2025). It is thus possible that learners perceived VF constructions as more salient than SF constructions leading to differences in processing of these two constructions and, as a result, to different priming effects. Support for this hypothesis also comes from the qualitative analysis of the debriefing questionnaires which revealed that the use of gerunds was noticed by the participants more frequently (n = 16) than the use of satellites (n = 7). To test whether the persisting effect of VF primes is due to surprisal or to differences in visual and structural saliency, it would be interesting to replicate this experiment by changing the language of the primes into a VF language. In this scenario, a stronger priming effect is expected for SF structures following an implicit learning account contrary to what one would expect if the larger priming effects were due to visual saliency. Finally, it would be worth investigating whether the persistent effect of VF primes is mediated by learners' L1. Since VF constructions are surprising not only in learners' L2 (English), but also in their L1 (German), this could have potentially led to stronger surprisal effects caused by the co-activation of the L1. Future studies could address this possibility by testing L2-to-L3 priming of ME in L1 speakers of a typologically equipollent language, which is not strongly biased toward either SF or VF constructions.

Another possible confound that needs to be considered is the presence of cognates between English and Italian. Although no identical cognates were included in the task, some Path verbs can be considered non-identical cognates, in particular the pairs “enter”–entra and “descends”–scende. Research on cognate processing and acquisition has shown that cognates are processed and learned more easily than non-cognates (Arana et al., 2022; Cenoz et al., 2022; Engemann and Radetzky, 2024; Otwinowska and Szewczyk, 2019), thus, it is possible that the stronger influence of VF primes on L3 production is due to the fact that the processing of cognates facilitated the lexical activation of Path verbs compared to the activation of Manner verbs. However, we consider this explanation unlikely, since evidence of a stronger and more long-lasting effect VF primes over SF primes was found also in another across-language priming study of ME where the prime language (German) and the target language (Italian) did not present any cognates (Baroncini et al., 2025).

Although the results presented above might be compatible with our hypothesis that priming from the L2 to the L3 can lead to implicit learning, the absence of the expected cumulative increase of VF constructions during the priming task requires further consideration. It is possible that the lexical overlap between prime and target triggered explicit memory mechanisms which operated concurrently with the implicit mechanisms of abstract priming. The former might have obscured the effects of the latter, thereby making the cumulative priming effects difficult to detect. This explanation is compatible with accounts which argue that the lexical boost effect and abstract priming are linked to two different mechanisms (Chang et al., 2006; Scheepers et al., 2017), and it is supported by the results of the debriefing questionnaire which indicate that most participants in our study were aware of the target structure during the experiment. Furthermore, unlike our study, many studies that have found cumulative priming effects in L2 participants either did not have lexical repetition between prime and target (Kaan and Chun, 2018; van Dijk and Hopp, 2025), or had lexical repetition in only half of the trials (Jackson and Ruf, 2017) or reported that participants did not show awareness of the target structure in the debriefing questionnaire (Hwang, 2022).

It is relevant to note that additional exploratory analyses revealed that neither the immediate nor the cumulative priming effects were modulated by Italian or English proficiency. They did, however, yield a significant main effect of Italian proficiency, suggesting that more proficient Italian L3 learners produced more VF constructions than less proficient learners. This finding aligns with previous research that found that, although ME expression continues to pose difficulties even at high levels of proficiency, L2 learners do improve in this domain as they become more proficient in the target language (e.g., Song et al., 2016; Treffers-Daller and Calude, 2015). Nonetheless, the limited number of participants tested and their highly variable profile in terms of age, proficiency and age of onset (see Table 1) does not allow us to investigate with sufficient accuracy the effects that these variables might have on participants' susceptibility to priming and cross-linguistic awareness.

Concerning our third research question, we did not find evidence of any statistically significant improvement in the cross-linguistic awareness of ME after the priming intervention. Nonetheless, the numerical trends went in the expected direction, showing a slight improvement in noticing and explaining for ME but not for the control structure. It is possible that, given the small numeric difference found between pre- and post-test (0.17 points), the effect size was too small for the effect to be detected and that a larger number of participants and/or items would be necessary for it to become significant.5 Interestingly, even if participants did not show any significant improvement in their cross-linguistic awareness of ME, the results of the descriptive analysis of the debriefing questionnaire revealed that most of the participants (82%) noticed either semantic or structural aspects of ME encoding during the experiment. This suggests that the priming intervention did indeed lead to noticing of ME, as predicted. However, the skills needed for the completion of the cross-linguistic awareness task went beyond mere noticing. Participants were asked to compare structures in two different languages, a task which requires not only noticing but also a high degree of linguistic reflection (Angelovska and Hahn, 2014). It is thus possible that the priming task enhanced only noticing of ME but did not foster a sufficient level of linguistic reflection, which is necessary to develop cross-linguistic awareness skills.

A further relevant point of discussion concerns the limitations and the strength of the designed cross-linguistic task itself. On the one hand, the subjective nature of noticing as well as the strong interrelationship between cross-linguistic awareness, cross-linguistic knowledge and metalanguage make it impossible for an off-line task to capture all the nuances of these processes. We cannot know if every time participants noted down or circled a word, they were really drawn by the structure we targeted. Similarly, we cannot know if the lack of an explanation is due to lack of awareness of the noticed linguistic phenomenon or the lack of technical words to describe it. On the other hand, the statistical analysis revealed a significant difference between the participants' ability of noticing and explaining ME (target structure) compared to clitics/pronouns (control structure). This suggests that the designed task can detect differences in participants' ease in noticing and explaining different linguistic phenomena. Crucially, this effect is in line with previous research concerning the L2 acquisition of these constructions. In fact, it is true that both of these constructions pose difficulties for L2 learners. However, typical issues in clitic acquisition concern the selection of morphological marking for case, gender and number and not their placement—the aspect that was targeted in this task (Sciutti, 2020).

Concerning the relationship between priming and cross-linguistic awareness, we can thus conclude that we found no evidence that the priming intervention had a positive effect on participants' cross-linguistic awareness of ME, although we did find numerical trends whereby participants' awareness of ME (but not the control structure) slightly increased in the post-test compared with the pre-test. Whether the lack of a significant improvement is only due to statistical power or to a limited potential of priming to foster more complex skills than mere noticing should be investigated by future more powered studies. Nonetheless, the cross-linguistic awareness task designed in the present study has been shown to detect differences in participants' noticing and explaining skills, making it a useful resource for future research.

Finally, we would like to discuss the contribution of the present study to our understanding of language learning and its possible implications for language didactics. Although we did not find conclusive evidence that L2 processing can lead to L3 learning in terms of implicit learning, we did find strong evidence that L2 processing leads to the activation of the processed construction in the L3, replicating the results of Hartsuiker et al. (2016). As mentioned in the introduction, activation is claimed to be the mechanism underlying CLI, which in turn has been shown to have an impact on L3 learning, not only in a negative way, but also in a positive one (e.g., Aribaş and Cele, 2021). We thus consider this further evidence that previously acquired L2s can be used as a strategic resource in the acquisition of additional languages. Crucially, the study shows that exposure to L2 constructions triggers automatic processes, i.e., the activation of the processed sentence in the L3. This suggests that the strategic use of L2s, in addition to activities involving explicit linguistic reflection, can target implicit processes. In practice, this could be implemented by developing activities in which learners are presented with structured targeted input not only in the target language (TL) but also in other languages of their repertoire. One practice that has been adopted in language didactics research to present learners with optimal input for their learning task is so-called input flooding. This technique consists in increasing the frequency of the targeted structure in the input provided to learners and aims at maximizing the chances that learners notice and acquire the target structure (e.g., Loewen et al., 2009; Madlener, 2016). The adoption of input flooding from a Lx to the TL could be particularly beneficial when learners are more proficient in the Lx and are confronted with a complex acquisitional task in the L3. For instance, it might be possible to use this type of targeted exposure as a preparatory activity for more complex tasks in order to activate the targeted structure in learners' mind and make it easier for them to process and produce it in subsequent activities. Moreover, input flooding can be adopted from a multilingual perspective by presenting learners with targeted input in the TL in combination with another language of learners' repertoire, as implemented by Abel-Hardenberg et al. (2025).

5 Conclusion

The present study investigated the effects of a L2-to-L3 priming experiment on the production and cross-linguistic awareness of multilingual learners in their L3. The adoption of the priming paradigm allowed us to investigate two psycholinguistic mechanisms which influence learning: transient activation and implicit learning. Our findings indicate that processing L2 input can activate target L3 constructions, providing strong evidence for transient activation. The results of this study are relevant for our understanding of the psycholinguistic mechanism underlying learning in multilingual learners as well as the implementation of new methods for the assessment of cross-linguistic awareness and can have implications for language didactics in multilingual contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the University of Mannheim (EK Mannheim 28/2021, 25.05.2021). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation. HE: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research presented in this study was funded by a grant of the German Research Foundation (DFG) awarded to the second author Helen Engemann for project P2 (project no. 437487447), Priming in contact-setting bilinguals and monolinguals as a driver of language change, as part of the research unit Structuring the input in language processing, acquisition and change (FOR 5157). The open access publication of this article was funded by the University of Mannheim.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/flang.2025.1728907/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^In this study, we consider as L3 the language under investigation (Italian) and we adopt Hammarberg's definition of L2: “we will use the term […] L2 for any other language that the person has acquired after the L1” (Hammarberg, 2001, p. 22). Thus, the term L3 is used here to draw a clear distinction between the target language (Italian) and all other acquired foreign languages. Furthermore, as in Hammarberg (2001), the term L3 does not necessarily correspond here to the order of acquisition. Therefore, the L3 is not necessarily the third language acquired by the participants.

2. ^The languages spoken by these participants were either SF or typologically equipollent, thus we did not have any reason to assume that these participants would differ in the way they process and produce ME in English and Italian compared to their monolingual peers.

3. ^The number of items was limited by the restricted number of Manners and Paths which can be depicted, easily recognized and are likely to be known to L2 learners (see Michelotti and Engemann, 2025). Nonetheless, the results of a power analysis (see Section 2.9) revealed this number of items to be sufficient to detect the effects of interest (immediate and cumulative priming).

4. ^Given the difficulty in recruiting participants belonging to this very specific population, it was not possible to run an additional study to norm the difficulty level of the sentences included in the task. To make sure that difficulty did not affect the results, we thus employed list randomization.

5. ^As our study is the first one to adopt this task, we could not conduct a data-based power analysis.

References

Abel-Hardenberg, N., Poarch, G. J., and Michel, M. (2025). The effect of pedagogical translanguaging, typographic input enhancement, and input flood on the awareness for syntactic L1–L3 transfer opportunities in Dutch learners of L3 German. J. Eur. Sec. Lang. Assoc. 9, 124–138. doi: 10.22599/jesla.119

Alghamdi, A., Daller, M., and Milton, J. (2019). The persistence of L1 patterns in SLA: the boundary crossing constraint and incidental learning. Vigo Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 16, 81–106. doi: 10.35869/vial.v0i16.94

Anastasio, S. (2023). Motion event construal in L2 French and Italian: from acquisitional perspectives to pedagogical implications. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 61, 37–60. doi: 10.1515/iral-2022-0046

Angelovska, T. (2018). Cross-linguistic awareness of adult L3 learners of English: a focus on metalinguistic reflections and proficiency. Lang. Aware. 27, 136–152. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2018.1431243

Angelovska, T., and Hahn, A. (2014). “Raising language awareness for learning and teaching L3 grammar,” in The Grammar Dimension in Instructed Second Language Learning, eds. A. Benati, C. Laval, and M. J. Arche (London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic), 185–207. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303945889_Raising_Language_Awareness_for_Learning_and_Teaching_L3_Grammar (Accessed May 28, 2025).

Arana, S. L., Oliveira, H. M., Fernandes, A. I., Soares, A. P., and Comesaña, M. (2022). The cognate facilitation effect depends on the presence of identical cognates. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 25, 660–678. doi: 10.1017/S1366728922000062

Aribaş, D. S., and Cele, F. (2021). Acquisition of articles in L2 and L3 English: the influence of L2 proficiency on positive transfer from L2 to L3. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 42, 19–36. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2019.1667364

Baroncini, I., Michelotti, A., and Engemann, H. (2025). Priming motion events in Italian heritage language speakers: agents and mechanisms of language change. Linguist Approaches Biling. doi: 10.1075/lab.24048.bar

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., and Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Beavers, J., Levin, B., and Wei Tham, S. (2010). The typology of motion expressions revisited. J. Linguist. 46, 331–377. doi: 10.1017/S0022226709990272

Bencini, G. M. L. (2025). Structural Priming in Sentence Production. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781009236713

Bunger, A., Papafragou, A., and Trueswell, J. (2013). Event structure influences language production: evidence from structural priming in motion event description. J. Mem. Lang. 69, 299–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2013.04.002

Cadierno, T., and Ruiz, L. (2006). Motion events in Spanish L2 acquisition. Annu. Rev. Cogn. Linguist. 4, 183–216. doi: 10.1075/arcl.4.08cad

Cenoz, J., Leonet, O., and Gorter, D. (2022). Developing cognate awareness through pedagogical translanguaging. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 25, 2759–2773. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2021.1961675

Chang, F., Dell, G. S., and Bock, K. (2006). Becoming syntactic. Psychol. Rev. 113, 234–272. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.2.234

Chen, X., Wang, S., and Hartsuiker, R. J. (2023). Do structure predictions persevere to multilinguals' other languages? Evidence from cross-linguistic structural priming in comprehension. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 26, 653–669. doi: 10.1017/S1366728922000888

Cho, M. Y. (2010). The effects of input enhancement and written recall on noticing and acquisition. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 4, 71–87. doi: 10.1080/17501220903388900

Coumel, M., Ushioda, E., and Messenger, K. (2023). Second language learning via syntactic priming: investigating the role of modality, attention, and motivation. Lang. Learn. 73, 231–265. doi: 10.1111/lang.12522

Eibensteiner, L. (2023). L3 acquisition of aspect: the influence of structural similarity, analytic L2 and general L3 proficiency. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 61, 1827–1858. doi: 10.1515/iral-2021-0220

Ellis, N. C. (2017). “Implicit and explicit knowledge about language,” in Language Awareness and Multilingualism, eds J. Cenoz, D. Gorter, and S. May (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 113–124. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-02240-6_7