Abstract

Gastric cancer (GC) persists as a leading cause of global cancer morbidity and mortality, with its pathogenesis intricately linked to epigenetic dysregulation. Emerging research specifies the novelty of these mechanisms—including DNA methylation, histone modifications, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), and RNA modifications—in GC initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance. This review systematically examines key epigenetic mechanisms in GC, dissect the therapeutic implications as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Key insights include (1) aberrant methylation of tumor suppressor genes (e.g., CDH1, RUNX3): in early carcinogenesis; (2) histone lactylation and acetylation modulating immune evasion (3) ncRNAs (e.g., miR-21, HOTAIR); as promising biomarkers; and (4) m6A RNA modification in chemotherapy resistance. We further discuss translational applications of epigenetic biomarkers in liquid biopsies and targeted therapies (e.g., DNMT/HDAC inhibitors). Integrating multi-omics and epigenetic editing technologies may advance precision medicine in GC.

1 Introduction

Epigenetic modifications encompass heritable changes in gene activity without altering the DNA sequence, regulating gene expression through mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, and non-coding RNA (ncRNA) interactions (1–4). These reversible modifications serve as molecular switches, enabling spatiotemporal control of gene expression and cellular phenotypes. In gastric cancer (GC), epigenetic dysregulation contributes to precancerous lesions, tumor progression, and therapeutic resistance, offering novel avenues for early intervention and personalized therapy.

GC ranks as the fifth most common malignancy globally, with nearly one million new cases annually and a mortality rate ranking fifth among all cancers (5–7). Due to its insidious early symptoms and lack of specific reliable biomarkers, approximately 60% of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, resulting in a 5-year survival rate below 30%. The role of biomarkers in GC classification has evolved fundamentally, transitioning from irrelevance to central importance. Initially, classification was solely based on morphology (e.g., Lauren classification), with no role for biomarkers. The paradigm shifted with the validation of HER2 as the first actionable predictive biomarker for targeted therapy. The landmark TCGA project in 2014 subsequently established a molecular taxonomy, elevating biomarkers like EBV and MSI to a diagnostic role for defining distinct disease subtypes. In current practice, the role of biomarkers is decisively actionable. The simultaneous testing for a panel of biomarkers (e.g., HER2, PD-L1, MSI) enables clinicians to directly select the most effective targeted or immunotherapy regimens for individual patients. This progression signifies a shift in classification from purely descriptive morphology to a system that directly informs personalized treatment strategies.

Emerging evidence highlights the critical role of epigenetic regulation—including DNA methylation, histone modifications, ncRNAs, and RNA modifications—in GC initiation, progression, and microenvironment remodeling through reversible mechanisms. This review is structured as follows: First, we examine aberrant DNA methylation in early carcinogenesis and progression. Next, we discuss histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, and the roles of non-coding RNAs. We then explore RNA modifications, particularly m6A, in GC pathogenesis. Finally, we evaluate the clinical translation of epigenetic biomarkers and outline future research directions.

2 DNA methylation

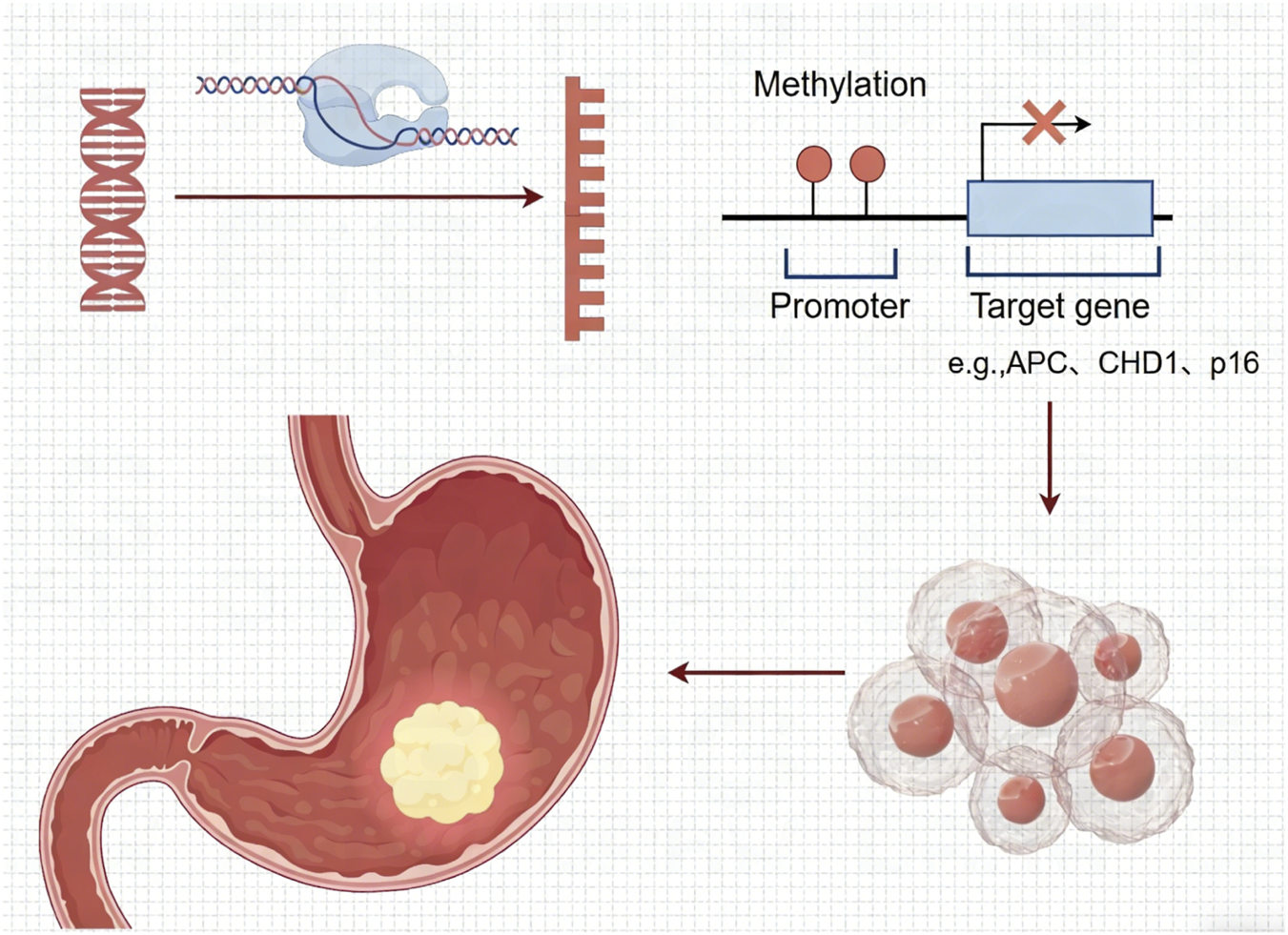

DNA methylation, catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), involves the addition of a methyl group to cytosine at CpG sites, forming 5-methylcytosine (5-mC), which typically inhibits gene expression in cancer (Figure 1); (8). Aberrant DNA methylation is not only a characteristic of end-stage GC, but also an early and driving event in the pathogenesis of GC.

FIGURE 1

Promoter DNA methylation leads to gene suppression, contributing to the pathogenesis of gastric cancer.

2.1 DNA methylation in early gastric carcinogenesis

In precancerous lesions (such as chronic atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia), promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes (e.g., p16, MLH1, APC) is observed (9–11). For instance, CDH1 (E-cadherin) methylation occurs in 30%–50% of premalignant lesions, impairing cell adhesion (12). The mechanisms by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection activates DNMT1 and inflammatory pathways (e.g., NF-κB), inducing genome-wide methylation aberrations that persist as “epigenetic memory” even after eradication contributes to gastric carcinogenesis are associated with activating DNMT1 and inflammatory signaling pathways (e.g., NF-κB), inducing genome-wide methylation aberrations that persist as “epigenetic memory” even after eradication (13–15). Similarly, EBV infection also shapes the gastric methylome distinctly (16–18). Both pathogens can activate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to promote gastric epithelial proliferation (19). Environmental factors (e.g., smoking, diet)can also promote hypermethylation of hub genes including MAPK1 and CDK1 contributing to gastric carcinogenesis (20, 21).

2.2 Dynamic DNA methylation changes in tumor progression

Aberrant methylation affects diverse functional gene groups, including tumor suppressors, DNA repair genes, hox genes, and cell cycle regulators collectively driving GC progression (22). Early-stage localized hypermethylation of tumor suppressors like RUNX3 presents opportunities for demethylating agents. In advanced GC, hypomethylation coexists with hypermethylation. For instance, TIMP3 demethylation promotes tumor invasion, whereas PTEN hypermethylation accelerates metastatic progression (23–25). Notably, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) methylation in metastatic GC carries metastasis-associated methylation signatures (26).

2.3 Summary and future perspectives

Research on DNA methylation in GC has decisively shifted from foundational discovery to clinical translation. Among the plethora of methylated genes reported, a few have emerged with superior merit for specific clinical applications, largely driven by advancements in the last 6 years. For early detection, the most promising and clinically adopted biomarkers are RNF180 and Septin9. Their methylation assays have been endorsed by China’s Expert Consensus and are available as NMPA-approved commercial kits for high-risk population screening (27). For prognostic stratification and monitoring, methylation of SPG20 and FBN1 robustly correlates with poor outcomes, while CPNE1 methylation status shows predictive value for chemotherapy response (28). Technologically, the analysis of EV-derived DNA methylation represents a major innovation for non-invasive detection, while single-cell methylome sequencing is set to resolve tumor heterogeneity (29). In our view, the future lies not in discovering more methylated genes, but in validating and integrating these top-tier candidates (e.g., RNF180/Septin9 for screening, SPG20/FBN1 for prognosis) into multi-analyte liquid biopsy panels to achieve the required sensitivity and specificity for early-stage GC detection (30).

3 Histone modifications

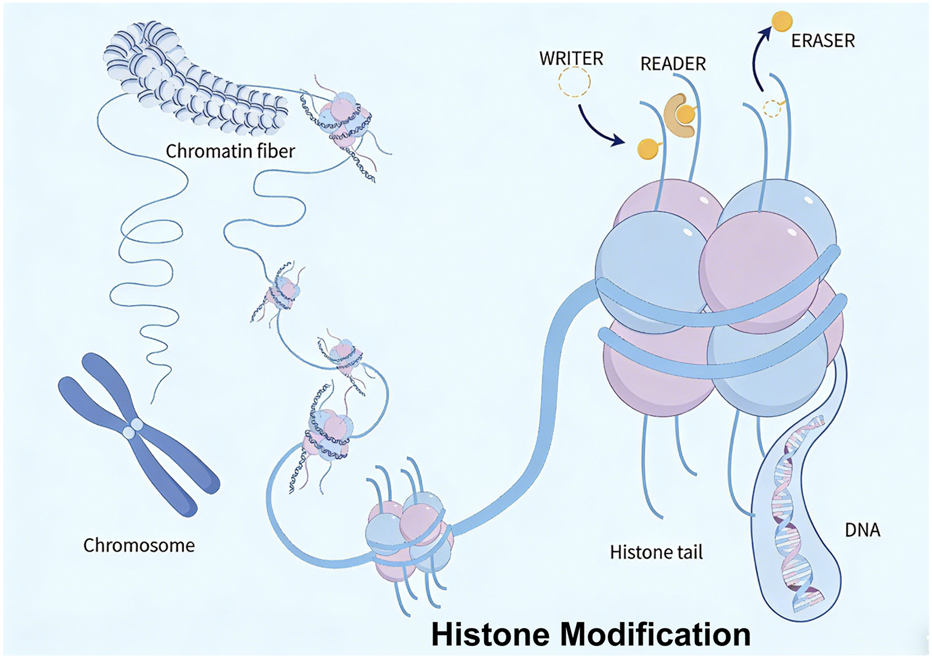

Chromatin, composed of DNA, histones, and non-histone proteins, is dynamically regulated by post-translational modifications (e.g., acetylation, methylation, lactylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination). Histone modifications form a sophisticated regulatory network by exerting crucial effects through coordinated gene expression in GC (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Epigenetic mechanisms of histone modification: acetylation, methylation, lactylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination.

3.1 Functional integration of histone modifications

In the GC microenvironment, lactate accumulation (Warburg effect) drives histone H3K18 lactylation (H3K18la), a recently discovered modification that links cellular metabolism directly to epigenetic regulation. The merit of H3K18la as a biomarker stems from its strong correlation with aggressive disease features, including poor prognosis, immune evasion, and metastasis (31–34). Mechanistically, H3K18la facilitates tumor proliferation and metastasis by recruiting M2 macrophages and activating the VCAM1-AKT pathway (35). While the direct detection of histone lactylation in patient blood remains challenging, its upstream driver (lactate) is readily measurable, and the downstream transcriptional signatures it induces (e.g., VCAM1) hold immediate promise as surrogate liquid biopsy biomarkers. This positions lactylation not only as a compelling therapeutic target but also as the conceptual foundation for a new class of metabolic-epigenetic biomarkers.

Acetylation: H. pylori carcinogenesis is linked to H4 acetylation in the p21 promoter region (36, 37). H3K9 and H4K16 hypoacetylation strongly associated with poorly differentiated GC (37, 38). Overexpression of histone deacetylases (HDACs) correlates with advanced GC stages may predict immunotherapy response (39, 40).

Methylation: Elevated levels of H3K27, H3K4, and H3K9 methylation collectively promote tumor initiation and progression. The histone methylation regulators EZH2, KDM6A, and KDM6B drive GC susceptibility through synergistic control of H3K27me (41). Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) mediated demethylation suppresses antitumor immunity in GC by upregulating exosomal PD-L1 to suppress T-cell responses (42). Histone methyltransferase SETD1A interacts with HIF1α to enhance glycolysis and promote GC progression (43).

Phosphorylation: Histone phosphorylation regulates key processes including DNA repair and apoptosis (44): H. pylori infection induces oncogenic H3S10 phosphorylation (45), while overexpression of phosphorylated H3 predicts inferior survival (46).

Ubiquitination: Histone ubiquitination modulates chromatin structure and degradation, with H2B ubiquitination levels correlating with disease progression (47, 48).

Other histone modifications, such as SUMOylation and ADP-ribosylation, also contribute to GC epigenetics, though their roles are less characterized and warrant further investigation.

3.2 Summary and future perspectives

Although numerous investigations underscore the significance and therapeutic potential of post-translational histone modifications, their downstream targets remain largely elusive. Consequently, research continues to prioritize the exploration of modification targets and pathways, while clinical translation remains limited.

Technologically, Chromatin Immunoprecipitation with highthroughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) enables genome-wide mapping of epigenetic marks; Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation (CUT&Tag) offers a high-resolution technique for profiling histone-DNA interactions; and CUT&Tag with tagmentation-based bisulfite sequencing (CUT&Tag-BS) permits simultaneous detection of histone modifications and DNA methylation, particularly valuable for limited samples. Looking forward, integrating these advanced in situ protein-DNA interaction profiling technologies will facilitate systematic elucidation of genome-wide histone modification landscapes and 3D chromatin dynamics in GC.

4 Chromatin remodeling

Chromatin remodeling complexes, including SWI/SNF and CHD family members, dynamically regulate nucleosome positioning and chromatin accessibility to drive GC progression. These ATP-dependent complexes function as structural effectors of epigenetic regulation and engage in reciprocal crosstalk with DNA methylation, mutually shaping their genomic localization and activity (49). These structural alterations represent fundamental mechanisms underlying gastric tumorigenesis and present promising targets for epigenetic-based therapeutic interventions.

Key remodeling components demonstrate distinct pathological roles: ARID1A (a SWI/SNF subunit) is frequently mutated in GC, with its loss driving malignant progression, immune microenvironment remodeling, and therapy resistance (50–52). CHD4 enhances chemoresistance by stimulating drug efflux and reducing intracellular cisplatin accumulation, while CHD5 acts as a pan-cancer tumor suppressor (53, 54).

Although SWI/SNF complex mutations have been elucidated more recently than those of classic oncogenes, the remarkable heterogeneity in how SWI/SNF dysfunction drives tumorigenesis presents both a challenge and a unique opportunity for developing precision epigenetic therapies in GC.

5 Non-Coding RNAs

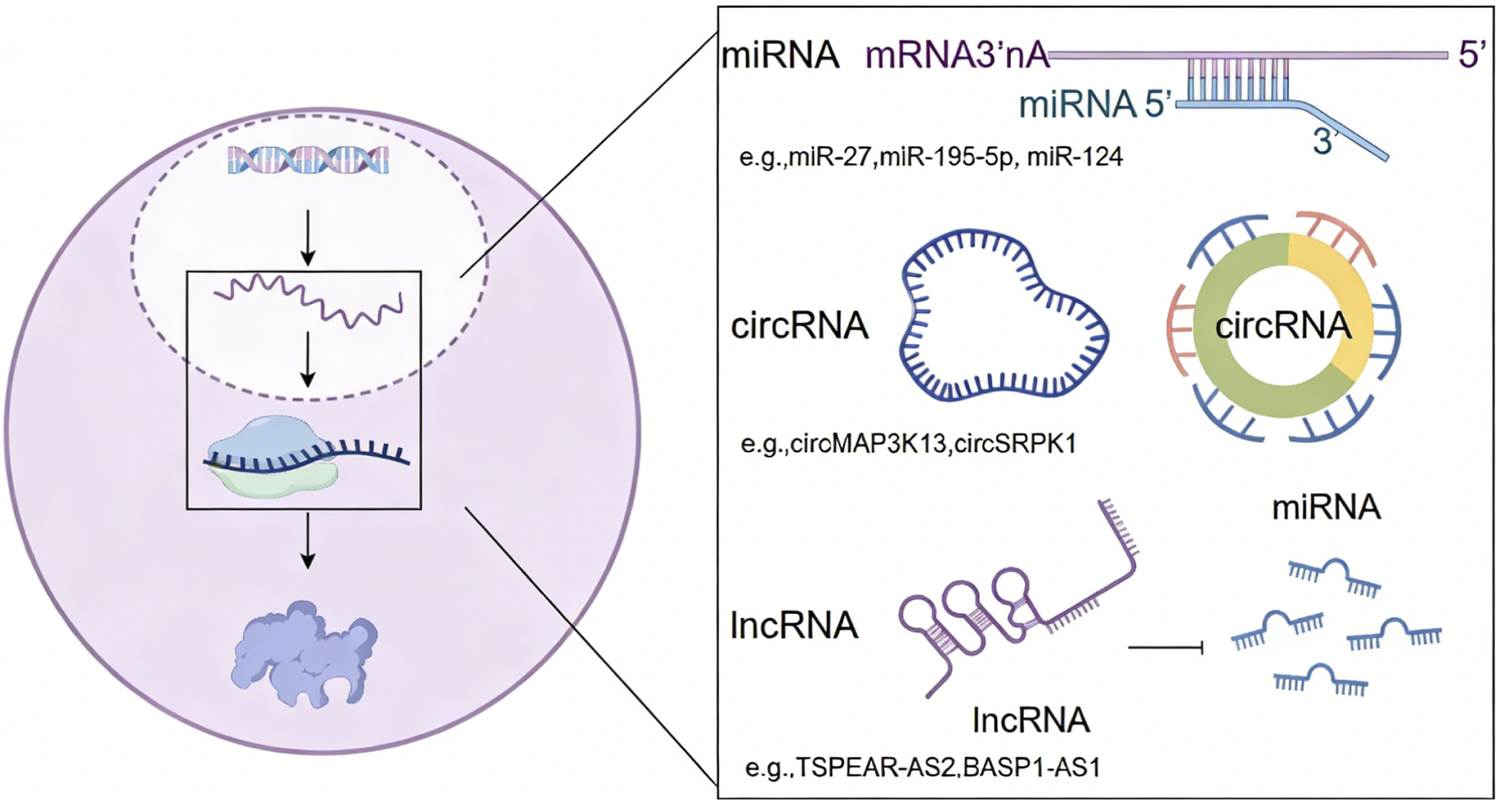

Although less than 2% of the human genome encodes proteins, the vast majority of transcripts consist of non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs). These ncRNAs play crucial roles in GC development by modulating chromatin architecture and gene expression (55, 56); (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

Regulatory functions of non-coding RNAs in GC by modulating gene expression.

5.1 miRNAs

In GC, miRNAs regulate gene expression by binding to the 3′untranslated region (3′UTR) of target mRNAs, leading to mRNA degradation or blocking ribosomal translation. Multiple miRNAs (e.g., miR-27, miR-195-5p, miR-124) have been identified as Influencing factors targeting oncogenic pathways such as EMT as well as Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in GC (57, 58). These findings highlight the critical regulatory roles of miRNAs in GC pathogenesis and their potential as therapeutic targets.

5.2 lncRNAs

The human genome encodes approximately 15,000 lncRNAs characterized by their remarkably diverse mechanisms of action. These regulatory molecules modulate epigenetic modifications through complex interactions suppressing or promoting gastric tumorigenesis (59). For instance, lncRNA TSPEAR-AS2 maintains the stemness of GC stem cells by regulating the miR-15a-5p/CCND1 axis (60). LncRNA BASP1-AS1 mediates histone H3K14 lactylation confering oxaliplatin resistance in GC (61). Despite these advances, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the precise regulatory mechanisms that lncRNAs employ in GC.

5.3 circRNAs

CircRNAs are single-stranded, covalently closed non-coding RNAs produced by back-splicing. They function as miRNA sponges (ceRNAs), modulate protein activity and transcription, and can sometimes be translated into peptides (62). CircRNAs influence GC progression and offer potential as diagnostic markers or therapeutic targets. Such as circMAP3K13 enhances pyroptosis and reduces tumorigenicity and metastasis, circSRPK1 mediates GC progression by interacting with hnRNP A2B1 to regulate RON mRNA alternative splicing (63).

5.4 Summary and future perspectives

In current ncRNA research, systematically characterize functionally significant RNA molecules remains a central challenge. Furthermore, ncRNAs form intricate regulatory networks, for which comprehensive understanding remains limited, like lncRNA interact with various histone modification factors to regulate GC development (64, 65). Critical barriers such as low cross-species homology, tumor heterogeneity, and inefficient in vivo delivery further impede clinical translation.

To address these challenges, emerging technologies and strategies are advancing the field. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics enable precise resolution of ncRNA expression dynamics within tissue microenvironments, while artificial intelligence and large language models offer novel computational frameworks for deciphering ncRNA regulatory networks. Clinically, the exceptional stability of ncRNAs in bodily fluids positions them as promising biomarkers.

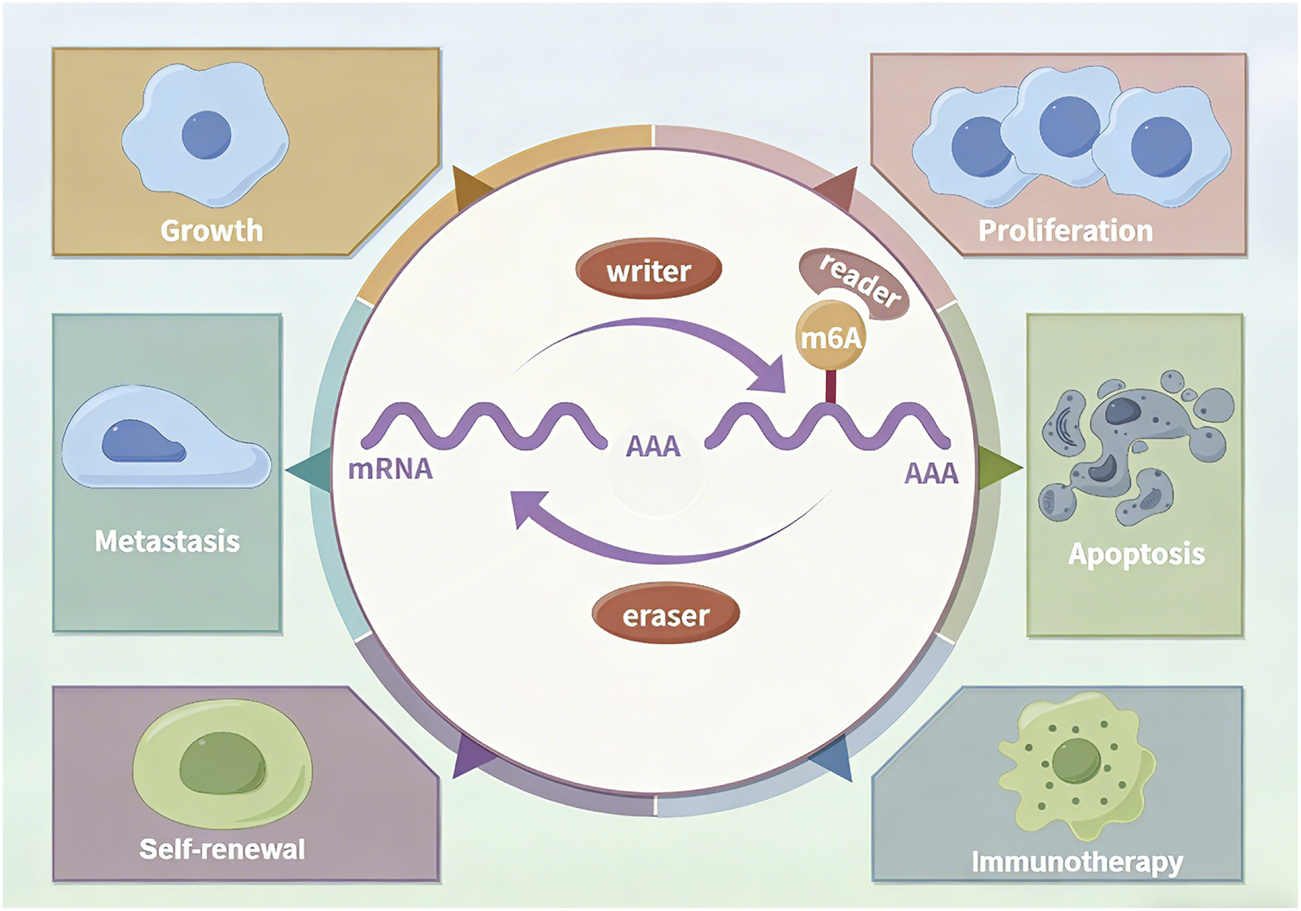

6 RNA modifications

RNA modifications play pivotal roles in GC progression by dynamically regulating RNA stability, splicing, and translational efficiency. RNA modification is coordinately regulated by methyltransferases (“Writers”), demethylases (“Erasers”), and binding proteins (“Readers”), collectively governing diverse malignant behaviors in GC (66–68). Research on m6A modification has dominated the field, whereas progress in understanding many other RNA modifications has lagged behind (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

The m6A Modification: a representative example of RNA modifications.

6.1 The m6A RNA methylation

The m6A writer METTL3 acts as an oncogene by stabilizing STAT5A and DEK mRNAs, thereby promoting GC progression (69–71), while METTL14-mediated m6A modification suppresses GC progression by regulating miR-30c-2-3p/AKT1S1 axis or lnc-PLCB1/DDX21 axis (72, 73). And METTL16 promotes GC via m6A-modification on FDX1 mRNA (74). Meanwhile reader diversify m6A-mediated phenotypes: YTHDF1 enhances USP14 translation to accelerate tumor growth, and YTHDF2 maintains cancer stemness by regulating ONECUT2 degradation, leading to oxaliplatin resistance (75, 76). Reader hnRNPA2B1 contribute to the maintenance of stemness property via Wnt/β-catenin pathway and exacerbate chemoresistance in GC (77). IGF2BP2-meidated m6A of CSF2 in reprogramming mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which presents a promising therapeutic target for GC (78). Eraser ALKBH5 suppresses GC by suppressing PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling through PKMYT1/WRAP53 m6A demethylation yet promotes GC by activating JAK1 signaling via JAK1 demethylation (79–81). Additionally FTO facilitates metastasis by demethylating m6A from caveolin-1 and circFAM192A (82, 83). This regulatory complexity reveals the therapeutic potential of targeting specific m6A regulators in GC.

6.2 Other RNA methylations

The m7G modification, driven by the METTL1/WDR4 complex, promotes GC progression through enhancing oncogenic tRNA expression and facilitating the translation of oxidative phosphorylation-related genes, thereby accelerating metabolic reprogramming (84). Clinically, prognostic signatures based on m7G-associated lncRNAs show significant value in predicting patient survival and immunotherapy response (85, 86). Similarly, m5C modifications mediated by writers such as NSUN2 contribute to gastric carcinogenesis, with PTEN mRNA m5C modification playing a key role in progression (87). Elevated m5C levels enhance tumor cell invasiveness, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target (88, 89).

6.3 Other RNA modifications

Upregulation of NAT10 by H. pylori infection promotes gastric tumorigenesis through ac4C-mediated stabilization of the oncogenic transcripts MDM2 and HK2 (90, 91). Additionally, NAT10 enhances the hypoxia tolerance of GC cells by mediating ac4C modification on SEPT9 mRNA, which activates the HIF-1 pathway and glycolytic reprogramming. Combining Apatinib with ac4C inhibition presents a promising strategy to overcome resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy (92, 93).

6.4 Summary and future perspectives

The “Writer-Eraser-Reader” network of RNA modifications presents a rich source of biomarkers and therapeutic targets. When evaluating their merit as biomarkers, the key regulators themselves often show the most immediate promise due to their druggable nature and measurable expression changes. For instance, the overexpression of the writer METTL3 and the reader YTHDF1 consistently correlates with poor survival and advanced disease stage, making them strong prognostic biomarkers (69, 75). The eraser FTO is another key player, whose upregulation promotes metastasis and could serve as both a prognostic marker and a therapeutic target (82, 83). The past 6 years have been pivotal in moving from cataloging these modifications to understanding their functional circuits. The current challenge is no longer just discovery but the development of high-throughput methods for absolute quantification of modifications like m6A in clinical samples. We anticipate that in the near future, panels combining the expression levels of key regulators (e.g., METTL3, YTHDF1, FTO) with specific modification signatures on oncogenic transcripts will provide powerful tools for GC diagnosis and subtyping.

7 Clinical translation and future perspectives

7.1 Integrated epigenetic networks and biomarker potential

Emerging evidence reveals that DNA methylation and histone modifications frequently co-occur, forming interconnected epigenetic networks that mutually reinforce regulatory outcomes through cell context-dependent molecular interactions (94). This crosstalk is exemplified in GC cell line AGS, where H3K27me3-marked promoter regions consistently exhibit DNA hypermethylation, suggesting the potential for combined epigenetic targeting strategies (95). The development of diagnostic models incorporating both DNA methylation and histone modification profiles in premalignant lesions holds particular promise (96).

CircRNAs have emerged as attractive biomarker candidates due to their unique covalently closed circular structure, which confers exceptional resistance to exonuclease and RNase R degradation while enabling stage-specific expression patterns across diverse tissues (97). Their remarkable stability in biological fluids makes them ideal for liquid biopsy applications.

Epigenetic-based strategies for GC management have demonstrated remarkable clinical potential across multiple applications. For early detection, China’s Expert Consensus on Early Gastric Cancer Screening Technologies has endorsed RNF180/Septin9 methylation assays as viable screening tools, with NMPA-approved commercial kits now available for high-risk populations (27). Additional promising non-invasive biomarkers including MINT31 and APC methylation are under active investigation (98, 99). Prognostically, hypermethylation of SPG20 and FBN1 has shown significant correlation with poor clinical outcomes, while CPNE1 methylation status serves as a predictive biomarker for chemotherapy response (28).

7.2 Epigenetic-targeted therapies in GC

Several epigenetic inhibitors have shown promise in preclinical and clinical studies for GC. DNMT inhibitors (e.g., azacitidine) and HDAC inhibitors (e.g., vorinostat, chidamide) are being evaluated for their ability to reverse aberrant methylation and acetylation patterns (100–102). Additionally, inhibitors targeting specific epigenetic readers (e.g., BET inhibitors) and writers (e.g., METTL3 inhibitors) are under investigation. For example, STM2457 can precisely target METTL3, minimizing effects on other methyltransferases (103). As the first METTL3 inhibitor to enter clinical evaluation (NCT05584111), STC-15 demonstrates transformative potential in translating epitranscriptomic discoveries into therapeutic applications (104). These inhibitors have demonstrated significant efficacy in suppressing tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, particularly in GC.

In therapeutic development, current epigenetic therapies need optimization through precision delivery systems such as METTL3 siRNA-loaded nanoparticles, rational combination strategies like HDAC inhibitors with immunotherapy, and innovative approaches including CRISPR-dCas9-mediated targeted demethylation to address tumor heterogeneity (105, 106). A new research shows an innovative diagnostic and therapeutic 808 nm NIR laser irradiation-triggered engineered microbe that establishes an efficient delivery platform for DNMT1 inhibitors and iMXene, activating epigenetic immunity and paving the way for the broad application of epigenetic regulation in solid tumor treatment (107).

The translation of epigenetic biomarkers requires rigorous clinical validation. Future research should prioritize the identification and validation of biomarkers with well-defined mechanisms and clear clinical relevance. Successful clinical implementation will depend on multidisciplinary collaboration across molecular biology, materials science and bioinformatics to establish GC-specific epigenetic databases and advance single-cell epigenomic technologies, while developing ethical guidelines for emerging technologies like epigenetic editing. The future of GC epigenetics lies in developing clinically validated high-sensitivity detection systems, implementing multi-omics-guided precision therapy, and building cross-disciplinary innovation ecosystems. As the field transitions from mechanistic discovery to clinical implementation, these advances promise to revolutionize early detection and personalized treatment, ultimately achieving precision medicine for GC patients through sustained collaboration across academia, clinical practice and industry. Advances in ChIP, CUT&Tag, and high-resolution sequencing are profoundly transforming GC epigenetics. Moving forward, integrating multi-omics data across molecular, cellular, and tissue levels will systematically uncover the core functions of epigenetic regulation, translating these insights into clinical predictive models and precision therapies.

Future directions should focus on: (1) elucidating synergistic epigenetic mechanisms to refine diagnostic models; (2) developing real-time liquid biopsy platforms for treatment monitoring and recurrence surveillance; (3) implementing precision medicine approaches through integrated epigenetic profiling. These advances will likely transform GC management from reactive treatment to proactive interception.

8 Conclusion

As summarized in Table 1, the past 6 years have yielded a wealth of candidate epigenetic biomarkers for GC. However, it is clear that not all are created equal. From a translational perspective, DNA methylation markers (particularly RNF180/Septin9) currently hold the most immediate promise for early detection, as evidenced by their regulatory approval and inclusion in clinical guidelines. Non-coding RNAs like miR-21 offer robustness due to their high abundance, while key RNA modification regulators (e.g., METTL3) represent compelling targets for both therapy and companion diagnostics (108, 109). Despite this progress, the field’s primary challenge is no longer discovery but validation and integration. Current liquid biopsy approaches based on single markers still lack the sensitivity for reliable early-stage detection. Therefore, we argue that the most constructive path forward is the development of integrated multi-omics liquid biopsy panels that combine the best-in-class epigenetic markers (e.g., RNF180 methylation) with other analyte types (e.g., fragmentomics, proteomics) to achieve the necessary diagnostic performance.

TABLE 1

| Biomarker type | Specific marker | GC stage/context | Potential clinical application | Merit/evidence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA methylation | RNF180/septin9 | Early GC/high-risk screening | Early detection | ★★★★★ (NMPA-approved kit; expert consensus endorsement) |

| APC/MINT31 | Early GC/precancerous lesions | Early detection/risk stratification | ★★★★☆ (Consistently reported in cohorts) | |

| SPG20/FBN1 | Advanced GC | Prognosis (poor survival) | ★★★★☆ (Strong correlation in multiple studies) | |

| CPNE1 | Advanced GC (receiving chemo) | Predictive (chemotherapy response) | ★★★★☆ (Identified in comprehensive analyses) | |

| 20-CpG signature | Advanced GC (receiving anti-PD-1) | Predictive (immunotherapy response) | ★★★☆☆ (Promising initial data [37]) | |

| Histone modification | H3K18la | Advanced GC (metabolic subtype) | Prognosis (poor survival, immune evasion) | ★★★☆☆ (Mechanistically strong; direct detection challenging) |

| HDAC overexpression | Advanced GC | Prognosis/predictive (immunotherapy?) | ★★★☆☆ (Correlative data; targeted therapies exist) | |

| Non-coding RNA | miR-21 | Various stages | Diagnosis/prognosis | ★★★★☆ (Extensively validated; high abundance) |

| HOTAIR | Various stages | Prognosis (metastasis) | ★★★☆☆ (Strong functional data) | |

| circPVT1 | Various stages | Diagnosis/prognosis | ★★★☆☆ (Stable in fluids; stage-specific expression) | |

| RNA modification | METTL3 | Advanced GC | Prognosis (poor survival) | ★★★★☆ (Consistent overexpression; pro-tumorigenic function) |

| METTL14 | Advanced GC | Prognosis (better survival) | ★★★☆☆ (Consistently reported) | |

| YTHDF1 | Advanced GC | Prognosis (poor survival) | ★★★★☆ (Critical reader; drives progression) | |

| YTHDF2 | Advanced GC | Predictive (chemotherapy resistance) | ★★★☆☆ (Reported) | |

| FTO | Advanced GC | Prognosis (metastasis) | ★★★☆☆ (Pro-metastatic; potential target) | |

| METTL1 | Advanced GC | Prognosis (poor survival) | ★★★☆☆ (Reported) | |

| NSUN2 | Early GC/precancerous lesions | Early detection/risk stratification | ★★★☆☆ (Strong functional data) | |

| NAT10 | Early GC/precancerous lesions | Early detection/risk stratification | ★★★★☆(Strong functional data) |

Representative epigenetic biomarkers in gastric cancer.

Statements

Author contributions

RZ: Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Software, Investigation, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Resources, Validation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization. JC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the administrative support from The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

- GC

Gastric Cancer

- DNMT

DNA Methyltransferase

- 5-mC

5-Methylcytosine

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- EBV

Epstein-Barr Virus

- HER2

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- MSI

Microsatellite Instability

- PD-L1

Programmed Death-Ligand 1

- p16

Multiple tumor suppressor 1

- MLH1

MutL homolog 1

- APC

Adenomatous Polyposis Coli

- Wnt/β-catenin

Wingless-related integration site/Beta-catenin

- CHD

Chromodomain Helicase DNA-Binding Protein 1

- NF-κB

Nuclear Factor Kappa B

- PI3K/AKT

Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B

- MAPK1

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- CDK1

Cyclin-dependent kinase 1

- RUNX3

Runt-related transcription factor 3

- TIMP3

Metalloproteinase inhibitor 3

- PTEN

Phosphatase and tensin homolog

- ctDNA

Circulating Tumor DNA

- RNF180

Ring finger protein 180

- NMPA

National Medical Products Administration

- SPG20

Spartin

- FBN1

Fibrillin-1

- CPNE1

Copine-1

- EV

Extracellular Vesicle

- H3K18la

Histone H3 Lysine 18 Lactylation

- VCAM1-AKT

Vascular cell adhesion molecule1-protein kinase B

- p21

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A

- HDAC

Histone Deacetylase

- EZH2

Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2

- KDM6A/B

Lysine Demethylase 6A/B

- LSD1

Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1

- SETD1A

SET domain containing 1A

- HIF1α

Hypoxia inducible factor 1

- SUMO

Small ubiquitin-like modifier

- ADP

Adenosine diphosphate

- ChIP-seq

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing

- CUT&Tag

Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation

- CUT&Tag-BS

CUT&Tag with Bisulfite Sequencing

- SWI/SNF

Switch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (chromatin remodeling complex)

- CHD

Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein

- ARID1A

AT-Rich Interaction Domain 1A

- 3′-UTR

3′untranslated region

- EMT

Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition

- ncRNA

Non-Coding RNA

- miRNA

MicroRNA

- lncRNA

Long Non-Coding RNA

- circRNA

Circular RNA

- ceRNA

Competing Endogenous RNA

- TSPEAR-AS2

TSPEAR antisense RNA 2

- CCND1

Cyclin D1

- SRPK1

Serine/arginine protein kinase 1

- hnRNPA2B1

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1

- RON

Macrophage stimulating 1 receptor,MST1R

- m6A

N6-Methyladenosine

- m7G

N7-Methylguanosine

- m5C

5-Methylcytosine (RNA modification)

- ac4C

N4-Acetylcytidine

- METTL1/3/14/16

Methyltransferase-like 1/3/14/16

- YTHDF1/2

YTH N6-Methyladenosine RNA Binding Protein 1/2

- STAT5A

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5A

- DDX21

DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box helicase 21

- FDX1

Ferredoxin 1

- USP14

Ubiquitin-Specific-Processing Protease 14

- ONECUT2

One cut homeobox two

- IGF2BP2

Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 2

- CSF2

Colony stimulating factor 2

- MSC

Mesenchymal Stem Cell

- FTO

Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated Protein

- ALKBH5

AlkB Homolog 5

- PKMYT1

Protein kinase, membrane associated tyrosine/threonine 1

- WRAP53

WD repeat containing antisense to TP53

- JAK1

Janus kinase 1

- WDR4

WD repeat domain 4

- NSUN2

NOP2/Sun RNA Methyltransferase 2

- NAT10

N-Acetyltransferase 10

- MDM2

Murine double minute2

- HK2

Hexokinase 2

- SEPT9

Septin 9

- BET

Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal (protein family)

- CRISPR/dCas9

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/deactivated Cas9

- NIR

Near Infrared

References

1.

Jassim A Rahrmann EP Simons BD Gilbertson RJ . Cancers make their own luck: theories of cancer origins. Nat Reviews Cancer (2023) 23(10):710–24. 10.1038/s41568-023-00602-5

2.

Jones PA . Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Reviews Genet (2012) 13(7):484–92. 10.1038/nrg3230

3.

Zhao S Allis CD Wang GG . The language of chromatin modification in human cancers. Nat Reviews Cancer (2021) 21(7):413–30. 10.1038/s41568-021-00357-x

4.

Lan Q Liu PY Haase J Bell JL Hüttelmaier S Liu T . The critical role of rna M(6)a methylation in cancer. Cancer Research (2019) 79(7):1285–92. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-18-2965

5.

Smyth EC Nilsson M Grabsch HI van Grieken NC Lordick F . Gastric cancer. Lancet (London, England) (2020) 396(10251):635–48. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31288-5

6.

Siegel RL Giaquinto AN Jemal A . Cancer statistics, 2024. CA: A Cancer Journal Clinicians (2024) 74(1):12–49. 10.3322/caac.21820

7.

He F Wang S Zheng R Gu J Zeng H Sun K et al Trends of gastric cancer burdens attributable to risk factors in China from 2000 to 2050. The Lancet Regional Health West Pac (2024) 44:101003. 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.101003

8.

Skvortsova K Iovino N Bogdanović O . Functions and mechanisms of epigenetic inheritance in animals. Nat Reviews Mol Cell Biology (2018) 19(12):774–90. 10.1038/s41580-018-0074-2

9.

Matsusaka K Funata S Fukayama M Kaneda A . DNA methylation in gastric cancer, related to Helicobacter pylori and epstein-barr virus. World Journal Gastroenterology (2014) 20(14):3916–26. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.3916

10.

Kang GH Shim YH Jung HY Kim WH Ro JY Rhyu MG . Cpg island methylation in premalignant stages of gastric carcinoma. Cancer Research (2001) 61(7):2847–51.

11.

Sepulveda JL Gutierrez-Pajares JL Luna A Yao Y Tobias JW Thomas S et al High-definition cpg methylation of novel genes in gastric carcinogenesis identified by next-generation sequencing. Mod Pathology : An Official Journal United States Can Acad Pathol Inc (2016) 29(2):182–93. 10.1038/modpathol.2015.144

12.

Niwa T Tsukamoto T Toyoda T Mori A Tanaka H Maekita T et al Inflammatory processes triggered by Helicobacter pylori infection cause aberrant DNA methylation in gastric epithelial cells. Cancer Research (2010) 70(4):1430–40. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-09-2755

13.

Shijimaya T Tahara T Shimogama T Yamazaki J Kobayashi S Nakamura N et al Gastric microbiome composition accompanied with the Helicobacter pylori related DNA methylation anomaly. Epigenomics (2024) 16(21-22):1329–36. 10.1080/17501911.2024.2418803

14.

Niwa T Toyoda T Tsukamoto T Mori A Tatematsu M Ushijima T . Prevention of helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancers in gerbils by a DNA demethylating agent. Cancer Prevention Research (2013) 6(4):263–70. 10.1158/1940-6207.Capr-12-0369

15.

Maekita T Nakazawa K Mihara M Nakajima T Yanaoka K Iguchi M et al High levels of aberrant DNA methylation in helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosae and its possible association with gastric cancer risk. Clin Cancer Research : An Official Journal Am Assoc Cancer Res (2006) 12(3 Pt 1):989–95. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-05-2096

16.

Bessède E Mégraud F . Microbiota and gastric cancer. Semin Cancer Biology (2022) 86(Pt 3):11–7. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.05.001

17.

Ushiku T Chong JM Uozaki H Hino R Chang MS Sudo M et al P73 gene promoter methylation in epstein-barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma. Int Journal Cancer (2007) 120(1):60–6. 10.1002/ijc.22275

18.

Matsusaka K Kaneda A Nagae G Ushiku T Kikuchi Y Hino R et al Classification of epstein-barr virus-positive gastric cancers by definition of DNA methylation epigenotypes. Cancer Research (2011) 71(23):7187–97. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-11-1349

19.

Xu W Huang Y Yang Z Hu Y Shu X Xie C et al Helicobacter pylori promotes gastric epithelial cell survival through the Plk1/Pi3k/Akt pathway. OncoTargets Therapy (2018) 11:5703–13. 10.2147/ott.S164749

20.

Liu W Peng ZZ Zhang T Liao K Li J . Burden, trends, driving factors, and predictions of gastric cancer: a cross-national comparative analysis of China, Japan, and South Korea. BMC Cancer (2025) 25(1):1669. 10.1186/s12885-025-15009-8

21.

Qian Z Bai W Li J Rao X Huang G Zhang X et al Gut microbiome-mediated epigenetic modifications in gastric cancer: a comprehensive multiomics analysis. Front Cellular Infection Microbiology (2025) 15:1585881. 10.3389/fcimb.2025.1585881

22.

Baek SJ Kim M Bae DH Kim JH Kim HJ Han ME et al Integrated epigenomic analyses of enhancer as well as promoter regions in gastric cancer. Oncotarget (2016) 7(18):25620–31. 10.18632/oncotarget.8239

23.

Maruyama S Imamura Y Toihata T Haraguchi I Takamatsu M Yamashita M et al Foxp3+/Cd8+ ratio associated with aggressive behavior in Runx3-Methylated diffuse esophagogastric junction tumor. Cancer Science (2025) 116(1):178–91. 10.1111/cas.16373

24.

Nakamura K Suehiro Y Hamabe K Goto A Hashimoto S Kunimune Y et al A novel index including age, sex, htert, and methylated Runx3 is useful for diagnosing early gastric cancer. Oncology (2025) 103(4):320–6. 10.1159/000541173

25.

Kang YH Lee HS Kim WH . Promoter methylation and silencing of pten in gastric carcinoma. Lab Investigation; a Journal Technical Methods Pathology (2002) 82(3):285–91. 10.1038/labinvest.3780422

26.

Seo SY Youn SH Bae JH Lee SH Lee SY . Detection and characterization of methylated circulating tumor DNA in gastric cancer. Int Journal Molecular Sciences (2024) 25(13):7377. 10.3390/ijms25137377

27.

Nagano S Kurokawa Y Hagi T Yoshioka R Takahashi T Saito T et al Extensive methylation analysis of circulating tumor DNA in plasma of patients with gastric cancer. Scientific Reports (2024) 14(1):30739. 10.1038/s41598-024-79252-y

28.

Qi J Hong B Wang S Wang J Fang J Sun R et al Plasma cell-free DNA methylome-based liquid biopsy for accurate gastric cancer detection. Cancer Science (2024) 115(10):3426–38. 10.1111/cas.16284

29.

Lin B Jiao Z Dong S Yan W Jiang J Du Y et al Whole-genome methylation profiling of extracellular vesicle DNA in gastric cancer identifies intercellular communication features. Nat Communications (2025) 16(1):8084. 10.1038/s41467-025-63435-w

30.

Tang W Zhu Z Wang Z Li G Lin Q Cai S et al DNA methylation profiles predicting response to Anti-Pd-1-Based treatment in patients with advanced gastric cancer. BMC Medicine (2025) 23(1):529. 10.1186/s12916-025-04357-8

31.

Ju J Zhang H Lin M Yan Z An L Cao Z et al The alanyl-trna synthetase Aars1 moonlights as a lactyltransferase to promote Yap signaling in gastric cancer. The J Clinical Investigation (2024) 134(10):e174587. 10.1172/jci174587

32.

Yang H Zou X Yang S Zhang A Li N Ma Z . Identification of lactylation related model to predict prognostic, tumor infiltrating immunocytes and response of immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Front Immunology (2023) 14:1149989. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1149989

33.

Sun X Dong H Su R Chen J Li W Yin S et al Lactylation-related gene signature accurately predicts prognosis and immunotherapy response in gastric cancer. Front Oncology (2024) 14:1485580. 10.3389/fonc.2024.1485580

34.

Tsukihara S Akiyama Y Shimada S Hatano M Igarashi Y Taniai T et al Delactylase effects of Sirt1 on a positive feedback loop involving the H19-Glycolysis-Histone lactylation in gastric cancer. Oncogene (2025) 44(11):724–38. 10.1038/s41388-024-03243-6

35.

Zhao Y Jiang J Zhou P Deng K Liu Z Yang M et al H3k18 lactylation-mediated Vcam1 expression promotes gastric cancer progression and metastasis via Akt-Mtor-Cxcl1 axis. Biochem Pharmacology (2024) 222:116120. 10.1016/j.bcp.2024.116120

36.

Xia G Schneider-Stock R Diestel A Habold C Krueger S Roessner A et al Helicobacter pylori regulates P21(Waf1) by histone H4 acetylation. Biochem Biophysical Research Communications (2008) 369(2):526–31. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.073

37.

Park YS Jin MY Kim YJ Yook JH Kim BS Jang SJ . The global histone modification pattern correlates with cancer recurrence and overall survival in gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surgical Oncology (2008) 15(7):1968–76. 10.1245/s10434-008-9927-9

38.

Wisnieski F Leal MF Calcagno DQ Santos LC Gigek CO Chen ES et al Bmp8b is a tumor suppressor gene regulated by histone acetylation in gastric cancer. J Cellular Biochemistry (2017) 118(4):869–77. 10.1002/jcb.25766

39.

Weichert W Röske A Gekeler V Beckers T Ebert MP Pross M et al Association of patterns of class I histone deacetylase expression with patient prognosis in gastric cancer: a retrospective analysis. The Lancet Oncol (2008) 9(2):139–48. 10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70004-4

40.

Lin Y Jing X Chen Z Pan X Xu D Yu X et al Histone deacetylase-mediated tumor microenvironment characteristics and synergistic immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Theranostics (2023) 13(13):4574–600. 10.7150/thno.86928

41.

Lee SW Park DY Kim MY Kang C . Synergistic triad epistasis of epigenetic H3k27me modifier genes, Ezh2, Kdm6a, and Kdm6b, in gastric cancer susceptibility. Gastric Cancer Official Journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2019) 22(3):640–4. 10.1007/s10120-018-0888-9

42.

Shen DD Pang JR Bi YP Zhao LF Li YR Zhao LJ et al Lsd1 deletion decreases exosomal Pd-L1 and restores T-Cell response in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer (2022) 21(1):75. 10.1186/s12943-022-01557-1

43.

Wu J Chai H Xu X Yu J Gu Y . Histone methyltransferase Setd1a interacts with Hif1α to enhance glycolysis and promote cancer progression in gastric cancer. Mol Oncology (2020) 14(6):1397–409. 10.1002/1878-0261.12689

44.

Murakami Y . Phosphorylation of repressive histone code readers by casein kinase 2 plays diverse roles in heterochromatin regulation. J Biochemistry (2019) 166(1):3–6. 10.1093/jb/mvz045

45.

Yang TT Cao N Zhang HH Wei JB Song XX Yi DM et al Helicobacter pylori infection-induced H3ser10 phosphorylation in stepwise gastric carcinogenesis and its clinical implications. Helicobacter (2018) 23(3):e12486. 10.1111/hel.12486

46.

Takahashi H Murai Y Tsuneyama K Nomoto K Okada E Fujita H et al Overexpression of phosphorylated histone H3 is an indicator of poor prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma patients. Appl Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Morphology : AIMM (2006) 14(3):296–302. 10.1097/00129039-200609000-00007

47.

Wang J Qiu Z Wu Y . Ubiquitin regulation: the histone modifying enzyme's story. Cells (2018) 7(9). 10.3390/cells7090118

48.

Swatek KN Komander D . Ubiquitin modifications. Cell Research (2016) 26(4):399–422. 10.1038/cr.2016.39

49.

Wang ZJ Yang JL Wang YP Lou JY Chen J Liu C et al Decreased histone H2b monoubiquitination in malignant gastric carcinoma. World Journal Gastroenterology (2013) 19(44):8099–107. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.8099

50.

Klemm SL Shipony Z Greenleaf WJ . Chromatin accessibility and the regulatory epigenome. Nat Reviews Genet (2019) 20(4):207–20. 10.1038/s41576-018-0089-8

51.

Gu Y Zhang P Wang J Lin C Liu H Li H et al Somatic Arid1a mutation stratifies patients with gastric cancer to Pd-1 blockade and adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy : CII (2023) 72(5):1199–208. 10.1007/s00262-022-03326-x

52.

Ma F Ren M Li Z Tang Y Sun X Wang Y et al Arid1a is a coactivator of Stat5 that contributes to Cd8(+) T cell dysfunction and Anti-Pd-1 resistance in gastric cancer. Pharmacol Research (2024) 210:107499. 10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107499

53.

Wu J Zhou Z Li J Liu H Zhang H Zhang J et al Chd4 promotes acquired chemoresistance and tumor progression by activating the mek/erk axis. Drug Resistance Updates : Reviews Commentaries Antimicrobial Anticancer Chemotherapy (2023) 66:100913. 10.1016/j.drup.2022.100913

54.

Hashimoto T Kurokawa Y Wada N Takahashi T Miyazaki Y Tanaka K et al Clinical significance of chromatin remodeling factor Chd5 expression in gastric cancer. Oncol Letters (2020) 19(1):1066–73. 10.3892/ol.2019.11138

55.

Zhang J Li J Yang S Tang X Wang C Lin J et al Development and validation of an Arid1a-Related immune genes risk model in evaluating prognosis and immune therapeutic efficacy for gastric cancer patients: a translational study. Front Immunology (2025) 16:1541491. 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1541491

56.

Holoch D Moazed D . Rna-mediated epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Nat Reviews Genet (2015) 16(2):71–84. 10.1038/nrg3863

57.

Liu L Tian YC Mao G Zhang YG Han L . Mir-675 is frequently overexpressed in gastric cancer and enhances cell proliferation and invasion via targeting a potent anti-tumor gene Pitx1. Cell Signalling (2019) 62:109352. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.109352

58.

Yan J Zhang Y She Q Li X Peng L Wang X et al Long noncoding rna H19/Mir-675 axis promotes gastric cancer via fadd/caspase 8/Caspase 3 signaling pathway. Cell Physiology Biochemistry : International Journal Experimental Cellular Physiology, Biochemistry, Pharmacology (2017) 42(6):2364–76. 10.1159/000480028

59.

Chua PJ Lim JP Guo TT Khanna P Hu Q Bay BH et al Y-Box binding Protein-1 and Stat3 independently regulate atp-binding cassette transporters in the chemoresistance of gastric cancer cells. Int Journal Oncology (2018) 53(6):2579–89. 10.3892/ijo.2018.4557

60.

Han H Wang S Meng J Lyu G Ding G Hu Y et al Long noncoding rna Part1 restrains aggressive gastric cancer through the epigenetic silencing of pdgfb via the plzf-mediated recruitment of Ezh2. Oncogene (2020) 39(42):6513–28. 10.1038/s41388-020-01442-5

61.

Li Q Wang Y Chen L Shen Y Zhang S Yue D et al Lncrna Tspear-As2 maintains the stemness of gastric cancer stem cells by regulating the Mir-15a-5p/Ccnd1 axis. Biomolecules (2025) 15(9):1227. 10.3390/biom15091227

62.

Zhao Y Liu W Deng K Chen Y Zhou P Liu C et al Lncrna Basp1-As1 drives Pcbp2 K115 lactylation to suppress ferroptosis and confer oxaliplatin resistance in gastric cancer. Free Radical Biology and Medicine (2025) 240:717–34. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2025.09.002

63.

Du K Zhang X Qin Y Ma H Bing C Deng S et al Map3k13-232aa encoded by Circmap3k13 enhances cisplatin-induced pyroptosis by directly binding to Ikkα in gastric adenocarcinoma. Cell Death and Disease (2025) 16(1):667. 10.1038/s41419-025-07991-5

64.

Yu S Chen M Jiang K Chen C Liang J Zheng J et al Circsrpk1 mediated by the exon junction complex promotes gastric cancer progression by interacting with hnrnp A2b1 to regulate ron mrna alternative splicing. Cancer Letters (2025) 629:217879. 10.1016/j.canlet.2025.217879

65.

Lian Y Yan C Lian Y Yang R Chen Q Ma D et al Long intergenic non-protein-coding rna 01446 facilitates the proliferation and metastasis of gastric cancer cells through interacting with the histone lysine-specific demethylase Lsd1. Cell Death and Disease (2020) 11(7):522. 10.1038/s41419-020-2729-0

66.

Pan Y Fang Y Xie M Liu Y Yu T Wu X et al Linc00675 suppresses cell proliferation and migration via downregulating the H3k4me2 level at the Spry4 promoter in gastric cancer. Mol Therapy Nucleic Acids (2020) 22:766–78. 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.09.038

67.

Sang L Sun L Wang A Zhang H Yuan Y . The N6-Methyladenosine features of mrna and aberrant expression of M6a modified genes in gastric cancer and their potential impact on the risk and prognosis. Front Genetics (2020) 11:561566. 10.3389/fgene.2020.561566

68.

Xu P Liu K Huang S Lv J Yan Z Ge H et al N(6)-Methyladenosine-Modified Mib1 promotes stemness properties and peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer cells by ubiquitinating Ddx3x. Gastric Cancer : Official Journal Int Gastric Cancer Assoc Jpn Gastric Cancer Assoc (2024) 27(2):275–91. 10.1007/s10120-023-01463-5

69.

Xu P Yang J Chen Z Zhang X Xia Y Wang S et al N6-Methyladenosine modification of cenpf mrna facilitates gastric cancer metastasis via regulating fak nuclear export. Cancer Communications (London, England) (2023) 43(6):685–705. 10.1002/cac2.12443

70.

Wang Q Chen C Ding Q Zhao Y Wang Z Chen J et al Mettl3-Mediated M(6)a modification of hdgf mrna promotes gastric cancer progression and has prognostic significance. Gut (2020) 69(7):1193–205. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319639

71.

Zang Y Tian Z Wang D Li Y Zhang W Ma C et al Mettl3-Mediated N(6)-Methyladenosine modification of Stat5a promotes gastric cancer progression by regulating Klf4. Oncogene (2024) 43(30):2338–54. 10.1038/s41388-024-03085-2

72.

Liu Y Zhai E Chen J Qian Y Zhao R Ma Y et al M(6) a-Mediated regulation of Pbx1-Gch1 axis promotes gastric cancer proliferation and metastasis by elevating tetrahydrobiopterin levels. Cancer Communications (London, England) (2022) 42(4):327–44. 10.1002/cac2.12281

73.

Fan HN Chen ZY Chen XY Chen M Yi YC Zhu JS et al Mettl14-Mediated M(6)a modification of Circorc5 suppresses gastric cancer progression by regulating Mir-30c-2-3p/Akt1s1 axis. Mol Cancer (2022) 21(1):51. 10.1186/s12943-022-01521-z

74.

Chang M Cui X Sun Q Wang Y Liu J Sun Z et al Lnc-Plcb1 is stabilized by Mettl14 induced M6a modification and inhibits Helicobacter pylori mediated gastric cancer by destabilizing Ddx21. Cancer Letters (2024) 588:216746. 10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216746

75.

Sun L Zhang Y Yang B Sun S Zhang P Luo Z et al Lactylation of Mettl16 promotes cuproptosis via M(6)a-Modification on Fdx1 mrna in gastric cancer. Nat Communications (2023) 14(1):6523. 10.1038/s41467-023-42025-8

76.

Chen XY Liang R Yi YC Fan HN Chen M Zhang J et al The M(6)a reader Ythdf1 facilitates the tumorigenesis and metastasis of gastric cancer via Usp14 translation in an M(6)a-Dependent manner. Front Cell Developmental Biology (2021) 9:647702. 10.3389/fcell.2021.647702

77.

Fan X Han F Wang H Shu Z Qiu B Zeng F et al Ythdf2-Mediated M(6)a modification of Onecut2 promotes stemness and oxaliplatin resistance in gastric cancer through transcriptionally activating tfpi. Drug Resistance Updates : Reviews Commentaries Antimicrobial Anticancer Chemotherapy (2025) 79:101200. 10.1016/j.drup.2024.101200

78.

Wang J Zhang J Liu H Meng L Gao X Zhao Y et al N6-Methyladenosine reader Hnrnpa2b1 recognizes and stabilizes Neat1 to confer chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Cancer Communications (London, England) (2024) 44(4):469–90. 10.1002/cac2.12534

79.

Ji R Wu C Yao J Xu J Lin J Gu H et al Igf2bp2-Meidated M(6)a modification of Csf2 reprograms msc to promote gastric cancer progression. Cell Death and Disease (2023) 14(10):693. 10.1038/s41419-023-06163-7

80.

Hu Y Gong C Li Z Liu J Chen Y Huang Y et al Demethylase Alkbh5 suppresses invasion of gastric cancer via Pkmyt1 M6a modification. Mol Cancer (2022) 21(1):34. 10.1186/s12943-022-01522-y

81.

Zheng Z Lin F Zhao B Chen G Wei C Chen X et al Alkbh5 suppresses gastric cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis by inhibiting the translation of uncapped Wrap53 rna isoforms in an M6a-Dependent manner. Mol Cancer (2025) 24(1):19. 10.1186/s12943-024-02223-4

82.

Fang Y Wu X Gu Y Shi R Yu T Pan Y et al Linc00659 cooperated with Alkbh5 to accelerate gastric cancer progression by stabilising Jak1 mrna in an M(6) a-Ythdf2-Dependent manner. Clin Translational Medicine (2023) 13(3):e1205. 10.1002/ctm2.1205

83.

Zhou Y Wang Q Deng H Xu B Zhou Y Liu J et al N6-Methyladenosine demethylase fto promotes growth and metastasis of gastric cancer via M(6)a modification of Caveolin-1 and metabolic regulation of mitochondrial dynamics. Cell Death and Disease (2022) 13(1):72. 10.1038/s41419-022-04503-7

84.

Wu X Fang Y Gu Y Shen H Xu Y Xu T et al Fat mass and obesity-associated protein (fto) mediated M(6)a modification of Circfam192a promoted gastric cancer proliferation by suppressing Slc7a5 decay. Mol Biomedicine (2024) 5(1):11. 10.1186/s43556-024-00172-4

85.

Xu X Huang Z Han H Yu Z Ye L Zhao Z et al N(7)-Methylguanosine trna modification promotes gastric cancer progression by activating Sdhaf4-Dependent mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Cancer Letters (2025) 615:217566. 10.1016/j.canlet.2025.217566

86.

Zhao B Fang F Liao Y Chen Y Wang F Ma Y et al Novel M7g-Related lncrna signature for predicting overall survival in patients with gastric cancer. BMC Bioinformatics (2023) 24(1):100. 10.1186/s12859-023-05228-w

87.

Ma M Li J Zeng Z Zheng Z Kang W . Integrated analysis from multicentre studies identities M7g-Related lncrna-derived molecular subtypes and risk stratification systems for gastric cancer. Front Immunology (2023) 14:1096488. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1096488

88.

Zhao G Liu R Ge L Qi D Wu Q Lin Z et al Nono regulates M(5)C modification and alternative splicing of pten mrnas to drive gastric cancer progression. J Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research : CR (2025) 44(1):81. 10.1186/s13046-024-03260-z

89.

Li Y Xia Y Jiang T Chen Z Shen Y Lin J et al Long noncoding rna Diaph2-As1 promotes neural invasion of gastric cancer via stabilizing Nsun2 to enhance the M5c modification of Ntn1. Cell Death and Disease (2023) 14(4):260. 10.1038/s41419-023-05781-5

90.

Liu K Xu P Lv J Ge H Yan Z Huang S et al Peritoneal high-fat environment promotes peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer cells through activation of Nsun2-Mediated Orai2 M5c modification. Oncogene (2023) 42(24):1980–93. 10.1038/s41388-023-02707-5

91.

Deng M Zhang L Zheng W Chen J Du N Li M et al Helicobacter pylori-induced Nat10 stabilizes Mdm2 mrna via rna acetylation to facilitate gastric cancer progression. J Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research : CR (2023) 42(1):9. 10.1186/s13046-022-02586-w

92.

Wang Q Li M Chen C Xu L Fu Y Xu J et al Glucose homeostasis controls N-Acetyltransferase 10-Mediated Ac4c modification of Hk2 to drive gastric tumorigenesis. Theranostics (2025) 15(6):2428–50. 10.7150/thno.104310

93.

Yang Q Lei X He J Peng Y Zhang Y Ling R et al N4-Acetylcytidine drives glycolysis addiction in gastric cancer via Nat10/Sept9/Hif-1α positive feedback loop. Adv Science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany) (2023) 10(23):e2300898. 10.1002/advs.202300898

94.

Chen C Wang Z Lin Q Li M Xu L Fu Y et al Nat10 promotes gastric cancer liver metastasis by modulation of M2 macrophage polarization and metastatic tumor cell hepatic adhesion. Adv Science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany) (2025) 12(15):e2410263. 10.1002/advs.202410263

95.

Sogutlu F Pekerbas M Boztas G Bayram E Pariltay E Cogulu O et al The anticancer potential of Origanum onites L. in gastric cancer through epigenetic alterations. BMC Complementary Medicine Therapies (2025) 25(1):220. 10.1186/s12906-025-04942-7

96.

Gao F Ji G Gao Z Han X Ye M Yuan Z et al Direct chip-bisulfite sequencing reveals a role of H3k27me3 mediating aberrant hypermethylation of promoter cpg islands in cancer cells. Genomics (2014) 103(2-3):204–10. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.12.006

97.

Padmanabhan N Ushijima T Tan P . How to stomach an epigenetic insult: the gastric cancer epigenome. Nat Reviews Gastroenterol and Hepatology (2017) 14(8):467–78. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.53

98.

Nie Y Gao X Cai X Wu Z Liang Q Xu G et al Combining methylated Septin9 and Rnf180 plasma markers for diagnosis and early detection of gastric cancer. Cancer Communications (London, England) (2023) 43(11):1275–9. 10.1002/cac2.12478

99.

Hideura E Suehiro Y Nishikawa J Shuto T Fujimura H Ito S et al Blood free-circulating DNA testing of methylated Runx3 is useful for diagnosing early gastric cancer. Cancers (2020) 12(4). 10.3390/cancers12040789

100.

Li G Ping M Guo J Wang J . Comprehensive analysis of Cpne1 predicts prognosis and drug resistance in gastric adenocarcinoma. Am Journal Translational Research (2024) 16(6):2233–47. 10.62347/niyr2094

101.

Momparler RL . Pharmacology of 5-Aza-2'-Deoxycytidine (decitabine). Semin Hematology (2005) 42(3 Suppl. 2):S9–16. 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2005.05.002

102.

Dai W Liu S Zhang J Pei M Xiao Y Li J et al Vorinostat triggers Mir-769-5p/3p-Mediated suppression of proliferation and induces apoptosis via the Stat3-Igf1r-Hdac3 complex in human gastric cancer. Cancer Letters (2021) 521:196–209. 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.09.001

103.

Singh A Chang TY Kaur N Hsu KC Yen Y Lin TE et al Cap rigidification of Ms-275 and chidamide leads to enhanced antiproliferative effects mediated through Hdac1, 2 and tubulin polymerization inhibition. Eur Journal Medicinal Chemistry (2021) 215:113169. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113169

104.

Yankova E Blackaby W Albertella M Rak J De Braekeleer E Tsagkogeorga G et al Small-molecule inhibition of Mettl3 as a strategy against myeloid leukaemia. Nature (2021) 593(7860):597–601. 10.1038/s41586-021-03536-w

105.

Rosenfeld YO Rausch O McMahon J Vasiliauskaite L Saunders C Sapetschnig A et al 1373 Stc-15, an oral small molecule inhibitor of the rna methyltransferase Mettl3, inhibits tumour growth through activation of anti-cancer immune responses and synergises with immune checkpoint blockade. J ImmunoTherapy Cancer (2022) 10(Suppl. 2):A1427. 10.1136/jitc-2022-SITC2022.1373

106.

Sukocheva OA Liu J Neganova ME Beeraka NM Aleksandrova YR Manogaran P et al Perspectives of using microrna-loaded nanocarriers for epigenetic reprogramming of drug resistant colorectal cancers. Semin Cancer Biology (2022) 86(Pt 2):358–75. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.05.012

107.

Davalos V Esteller M . Cancer epigenetics in clinical practice. CA: A Cancer Journal Clinicians (2023) 73(4):376–424. 10.3322/caac.21765

108.

Lou C Li Y Zhan R Fang Y Zhang A Liu Y et al Photo-triggered engineered microbes achieving dual epigenetic immunomodulation for gastric cancer. Biomaterials (2026) 325:123608. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2025.123608

109.

Zhang Y Liu H Li W Yu J Li J Shen Z et al Circrna_100269 is downregulated in gastric cancer and suppresses tumor cell growth by targeting Mir-630. Aging (2017) 9(6):1585–94. 10.18632/aging.101254

Summary

Keywords

biomarker, DNA methylation, epigenetics, gastric cancer, histone modification, non-codingRNA

Citation

Zeng R and Chen J (2026) Advances in epigenetics of gastric cancer. Oncol. Rev. 20:1656621. doi: 10.3389/or.2026.1656621

Received

30 June 2025

Revised

08 January 2026

Accepted

13 January 2026

Published

28 January 2026

Volume

20 - 2026

Edited by

Li-Juan Zhao, Zhengzhou University, China

Reviewed by

Anupam Chatterjee, Royal Global University, India

Abdullah Mamun, University of Mississippi, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Zeng and Chen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianning Chen, chjning@mail.sysu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.