Abstract

Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma (RLMS) remains a major therapeutic challenge because of frequent postoperative recurrence and the limited benefit of current adjuvant therapies. The marked molecular heterogeneity of RLMS and its incompletely characterized oncogenic drivers have hindered the development of effective targeted therapies. This review proposes an integrative framework that combines transcriptomic subtyping with surgical risk stratification to support artificial intelligence (AI)–guided drug repurposing. The delineation of RLMS subtypes and the identification of potential therapeutic targets through transcriptomic analysis are described, including PDGFRα and VEGFA. The AI-guided screening of approved and investigational drug libraries to identify compounds predicted to reverse subtype-specific molecular programs; preclinical studies highlight candidates such as pazopanib and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors is discussed. Finally, the outline of a personalized strategy is proposed, in which surgical decision-making integrates anatomic risk with molecular signatures to inform the selection of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapies. Integrating surgical management, multi-omics, and computational pharmacology helps bridge the gap from bench to bedside and, ultimately, improve outcomes for patients with RLMS. In contrast to prior work that addresses molecular subtyping or surgical management in isolation, this review presents an integrative framework that links surgical risk stratification with transcriptomic profiling to enable AI-guided drug repurposing and provides a roadmap for personalized RLMS therapy.

1 Introduction

Retroperitoneal sarcomas (RPS) comprise a heterogeneous group of malignancies that pose substantial therapeutic challenges (1). Among RPS, retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma (RLMS) is a common histologic subtype with aggressive behavior and frequent late presentation, partly due to its deep anatomic location (2–4). Complete surgical resection remains the cornerstone of curative-intent therapy. However, local and distant recurrence is common, and outcomes remain poor for patients with recurrent or unresectable disease (5).

Management of RLMS is complicated by substantial molecular heterogeneity. Recent transcriptomic and genomic studies have reported recurrent molecular alterations in RLMS. These include overexpression of receptor tyrosine kinases (e.g., PDGFRα) and angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGFA), as well as dysregulation of cell-cycle and epigenetic pathways (6, 7).

This molecular diversity contributes to variable clinical behavior and treatment response, underscoring the need for subtype-specific therapeutic strategies. Transcriptomic profiling is well suited for RLMS subtyping for its capture of the functional tumor state, including active gene-expression programs that may be more readily targetable than static genomic alterations (8). Moreover, transcriptomic data can identify activated pathways and candidate drug–gene interactions in a dynamic, clinically actionable manner, complementing genomic and proteomic profiling (9, 10).

The high relapse rate in RLMS is further compounded by the inconsistent benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy across patient subgroups (11–13). Emerging evidence suggests that molecular features may predict therapeutic benefit. For example, tumors with angiogenesis-high signatures may derive greater benefit from anti-angiogenic agents, whereas tumors with epigenetic dysregulation may be sensitive to histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (14, 15). These observations highlight the limitations of a uniform treatment approach and reinforce the need for biology-driven, personalized strategies.

To better stratify surgical risk, several tools have been developed, including the SARCO-M model (incorporating tumor size, vascular involvement, and prior resection history) and the RPS surgical complexity score (quantifying operative difficulty based on anatomic involvement) (16–18). These instruments provide a standardized, quantitative basis for preoperative assessment of surgical complexity and postoperative risk, thereby supporting individualized operative planning and multidisciplinary decision-making.

The emergence of precision medicine—enabled by high-throughput multi-omics and advanced artificial intelligence (AI)—offers a promising path forward (19). Recent reviews suggest that AI methods, including machine learning and deep learning, can integrate heterogeneous data (genomic, transcriptomic, and clinical) to identify candidate targets and predict drug response. Such approaches may be particularly valuable for rare, heterogeneous tumors such as RLMS, for which conventional trial designs are often impractical. By leveraging AI, it may be possible to accelerate identification of repurposable drugs tailored to specific molecular subtypes, thereby bridging bench research and clinical application (20, 21). Delineating RLMS molecular subtypes and systematically repurposing existing drugs with AI could enable a new therapeutic paradigm.

Although prior reviews have addressed transcriptomic sarcoma classification, surgical risk modeling in RPS, and AI-guided drug discovery separately, these domains have not been integrated into a cohesive RLMS-specific strategy. This review bridges that gap by proposing an integrative paradigm in which clinical surgical risk and molecular subtyping jointly inform AI-guided therapeutic matching—a holistic approach not yet systematically articulated in the literature.

This review synthesizes a novel approach for RLMS, outlining how the integration of transcriptome-based subtyping with refined surgical risk stratification can create a robust foundation for AI-guided drug repurposing, thereby paving the way for truly personalized therapy.

1.1 The clinical landscape and surgical stratification in RLMS

1.1.1 Diagnosis and current therapeutic limitations

Diagnosis of RLMS relies primarily on cross-sectional imaging (CT and MRI) for preoperative evaluation and surgical planning (22, 23). Definitive diagnosis is confirmed on post-resection pathology, which typically shows atypical spindle cells and increased mitotic activity; immunohistochemistry (e.g., SMA, Desmin, and Caldesmon) is supportive (24). Despite advances in surgery, recurrence exceeds 50% within 5 years, underscoring the limitations of local therapy alone (5). The benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy remains inconsistent, and responses vary across patient subgroups (25). Collectively, these observations support a shift from uniform, empiric management to biology-driven, personalized strategies that target the relevant molecular drivers.

1.1.2 The imperative for surgical risk stratification

Surgical management of RLMS is fraught with challenges, as tumors are often large and involve critical structures like the inferior vena cava (IVC), necessitating complex, multi-organ resections (26). While compartmental resection aiming for negative margins (R0/R1) is endorsed, its impact on long-term survival is debated (27, 28). The complexity of these procedures is compounded in recurrent disease due to altered anatomy and adhesions, leading to significant intraoperative blood loss and morbidity.

Therefore, a risk-stratified surgical approach is needed to balance oncologic control with functional outcomes (29). This approach involves preoperative risk categorization based on established factors, including tumor size, major vascular involvement, and prior resection history (30). Emerging tools, such as the SARCO-M model (31) and the RPS surgical complexity score, provide a quantitative basis for stratification (32). This clinical framework also enables integration of molecular data, supporting the hypothesis that tumors with high-risk surgical features may harbor distinct, targetable molecular profiles.

1.2 Decoding RLMS heterogeneity through multi-omics

Given the limitations of clinical and surgical parameters alone in predicting outcomes, there is a pressing need to dissect the biological underpinnings of RLMS aggressiveness and heterogeneity. This is where high-throughput multi-omics technologies offer invaluable insights.

1.2.1 The role of transcriptomics in subtyping

The “omics” revolution—encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—has expanded the analytical scope of cancer biology and enabled more comprehensive molecular characterization. Transcriptomics, particularly RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (33–35), has become central to molecular subtyping (36), enabling comprehensive assessment of gene-expression programs that reflect tumor cell state (37).

In RLMS, transcriptomic profiling is beginning to reveal molecular diversity. For instance, studies have identified subsets characterized by shared gene expression signatures involving dozens to hundreds of genes, such as those enriched for receptor tyrosine kinase signaling (e.g., PDGFRα) and angiogenic pathways (e.g., VEGFA) (38). The identification of such stable transcriptional clusters—rather than individual gene overexpression—provides a more robust basis for molecular taxonomy and reduces susceptibility to biological variance or spatial heterogeneity within tumors.

1.2.2 From molecular subtypes to druggable targets

The primary utility of molecular subtyping lies in its ability to nominate “druggable” targets. The overexpression of PDGFRα and VEGFA in a significant proportion of RLMS cases logically suggests the potential efficacy of anti-angiogenic agents and multi-kinase inhibitors. Furthermore, transcriptome analysis can uncover dysregulated pathways related to apoptosis evasion, cell cycle dysregulation, and epigenetic remodeling—hallmarks of cancer that are increasingly documented in sarcoma biology. For example, alterations in p53 and RB pathways are common in leiomyosarcoma, and epigenetic modifiers such as EZH2 and HDACs have been implicated in sarcoma progression (39–41). Thus, the translation of a distinct molecular subtype into an actionable treatment hypothesis constitutes the critical bridge connecting omics discovery to tangible therapeutic intervention.

1.3 Artificial intelligence as a catalyst for drug repurposing

1.3.1 AI in modern drug discovery

AI is increasingly used in pharmacology to integrate complex biological data and generate predictions of drug efficacy (42). Machine learning and deep learning methods can interrogate large-scale datasets—chemical structures, genomic features, and drug-response profiles—to infer candidate compound–target interactions (43).

The predictive performance of AI platforms (e.g., DLEPS and DeepDRK) depends on the quality, representativeness, and clinical relevance of the training data. These models are often trained on large-scale transcriptomic perturbation resources, such as LINCS L1000, which catalog gene-expression changes induced by thousands of compounds across diverse cell lines (44). Drug-induced transcriptomic responses are strongly context dependent. Therefore, predictions for RLMS may require training or fine-tuning using perturbation data from sarcoma-relevant models (e.g., leiomyosarcoma cell lines and patient-derived xenografts). Recent studies have incorporated lineage-specific data and reported improved performance for drug-sensitivity prediction in sarcoma-relevant settings (45). Validation commonly includes benchmarking against established drug-response datasets, evaluation in independent test sets, and experimental confirmation in preclinical models (46).

In the context of RLMS, a transcriptomic signature defining a PDGFRα-overexpressing subtype can be input into an AI platform (e.g., a DLEPS). The system then screens for compounds predicted to reverse this signature, effectively ‘normalizing’ the gene expression profile. This approach directly nominates drugs that are mechanistically poised to counteract the specific oncogenic drivers identified in the patient’s tumor (47, 48).

Recent reviews describe expanding applications of AI across the oncology pipeline, spanning early target discovery through clinical trial design and optimization. In rare cancers such as RLMS, AI-based approaches may partially mitigate small-sample limitations by integrating multimodal data and leveraging transfer learning from larger, related datasets. Explainable AI (XAI) methods are being developed to improve interpretability of model outputs, which may facilitate clinical translation. As these methods mature and are prospectively validated, they may support data-driven, subtype-specific therapeutic recommendations for RLMS (20, 21).

1.3.2 Application in RLMS drug repurposing

In RLMS, AI-guided drug repurposing offers an efficient, hypothesis-generating strategy. Pazopanib, a multikinase inhibitor with activity against VEGFR, is used for advanced RLMS; however, objective response rates are modest. A transcriptomic signature representing a specific RLMS subtype—preferably derived from primary tumors or representative models—can be used as an input to an AI platform. The platform can screen libraries of approved drugs to prioritize candidates predicted to counteract the dysregulated pathways. To improve clinical relevance, the model should be trained and/or validated using sarcoma-relevant transcriptomic perturbation data. This approach has nominated several candidate compounds. For example, these models have prioritized multikinase inhibitors (e.g., pazopanib) and epigenetic modulators (e.g., histone deacetylase inhibitors) based on predicted alignment with RLMS-associated vulnerabilities, including metastasis- and angiogenesis-related programs (49, 50). These in silico predictions provide a hypothesis-generating rationale for preclinical testing in biologically relevant models, such as patient-derived xenografts (PDXs). Therefore, future studies should validate prioritized compounds in RLMS-relevant models (e.g., PDXs and RLMS cell lines) to support translational relevance.

Similarly, olaratumab, an anti-PDGFRα monoclonal antibody, was withdrawn after phase III trials failed to demonstrate a survival benefit. Together, these observations highlight the limitations of empiric targeting in the absence of molecularly informed patient stratification. AI approaches may mitigate this limitation by identifying transcriptomic subsets in which these pathways are dominantly dysregulated, thereby enriching for patients more likely to benefit (51). However, VEGFA expression alone has not been established as a predictive biomarker for VEGF-pathway inhibitors; this underscores the need for multi-gene signatures and functional validation.

1.3.3 Challenges and considerations for AI implementation in RLMS

Although AI-guided drug repurposing is promising, its application to rare tumors such as RLMS presents distinct methodological challenges. First, the scarcity of high-quality, well-annotated transcriptomic datasets from RLMS limits the development and training of robust disease-specific models. Multi-institutional efforts to establish RLMS biobanks with linked clinical annotation and multi-omics data are needed.

Second, the limited interpretability of some models can obscure the biological rationale for drug prioritization and hinder clinical adoption. Explainable AI (XAI) methods are being developed to improve interpretability by linking model outputs to specific pathway-level alterations (52, 53).

Third, because drug-induced expression changes are context dependent, AI-guided hypotheses should be validated in biologically relevant models. Future work should prioritize generating perturbation datasets in RLMS-derived cell lines and PDXs to refine model training and improve prediction accuracy.

AI implementation in rare tumors such as RLMS is further constrained by limited sample size (“small data”). Unlike common cancers, RLMS lacks large, harmonized datasets required for robust model development and training. Collaborative initiatives, including federated learning and multi-institutional data sharing, may be required to address this bottleneck. Integrating radiomics and pathomics with transcriptomic data may strengthen predictive signals, particularly when sample sizes are limited. Such multimodal approaches can improve model generalizability and clinical utility in RLMS (20).

1.4 Data scarcity and alternative strategies for model robustness

Scarcity of high-quality, well-annotated RLMS transcriptomic datasets remains a key bottleneck for developing reliable models. Given the rarity of RLMS, conventional biobanking alone may be insufficient to achieve sample sizes needed for robust machine learning. Several complementary strategies may mitigate this limitation. These include: (1) multi-institutional aggregation of existing datasets with harmonized clinical and molecular annotation; (2) data augmentation (e.g., generative adversarial networks [GANs] and synthetic data generation) with safeguards for biological plausibility; (3) transfer learning, in which models pre-trained on larger related datasets (e.g., other soft-tissue sarcomas) are fine-tuned using available RLMS data; and (4) multimodal integration (e.g., proteomic, metabolomic, and radiomic features) to enrich predictive signals when transcriptomic sample size is limited. Combined with RLMS-focused biobanking, these approaches may improve model generalizability and support translation of AI-guided hypotheses toward clinical evaluation.

Despite these challenges, integrating AI with transcriptomic subtyping provides a pragmatic framework to prioritize personalized therapeutic hypotheses. As data resources expand and methods improve in transparency and validation, AI may become an important component of the RLMS therapeutic development workflow.

1.5 An integrated framework for personalized RLMS management

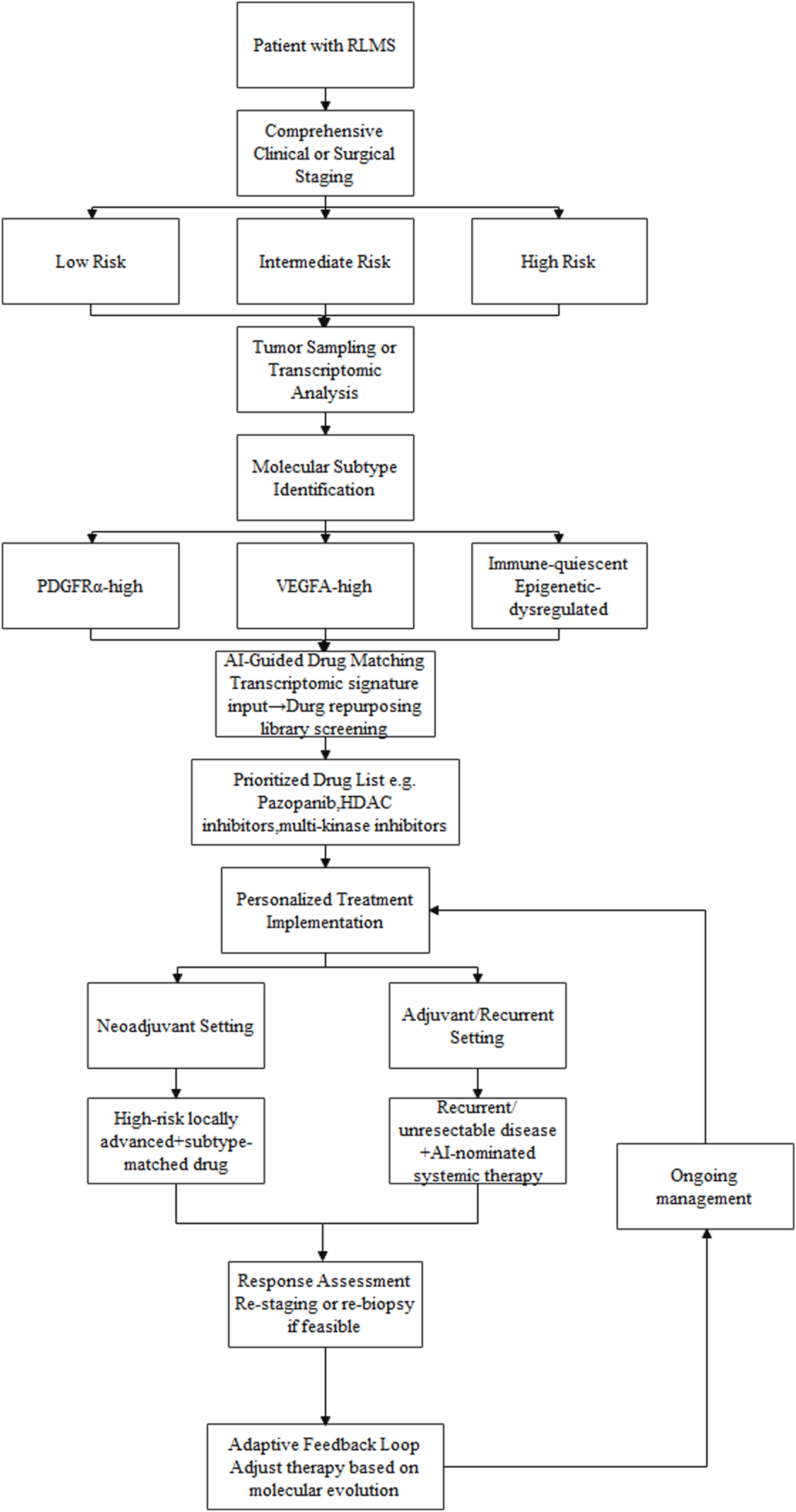

We propose a convergent framework in which surgical risk stratification and molecular subtyping jointly inform therapeutic decision-making, supported by AI. As depicted in Figure 1, the framework is designed as an iterative workflow with feedback across clinical, molecular, and treatment layers:

FIGURE 1

A conceptual framework for integrating clinical risk stratification, transcriptomic subtyping, and AI-guided drug repurposing in RLMS management:The workflow begins with comprehensive clinical and imaging assessment to stratify surgical risk. Tumor samples undergo transcriptomic profiling to define molecular subtypes (e.g., PDGFRα-high, VEGFA-high). These molecular signatures are processed through an AI-based drug prediction platform, which screens repurposing libraries to prioritize candidate drugs (e.g., pazopanib, HDAC inhibitors). The output is integrated with the patient´s clinical risk profile to guide personalized treatment decisions, including neoadjuvant therapy for high-risk locally advanced disease or systemic therapy for recurrent/unresectable cases. Response assessment and potential re-biopsy enable an adaptive feedback loop, allowing therapy to be adjusted based on molecular evolution.

Comprehensive clinical and surgical assessment: Cross-sectional imaging is used to define tumor extent and estimate operative risk, assigning the patient to a prespecified risk stratum (e.g., low, intermediate, high).

Molecular profiling: Tumor tissue undergoes transcriptomic profiling to assign a molecular subtype (e.g., PDGFRα-high, VEGFA-high, immune-quiescent).

AI-guided therapeutic matching: The molecular subtype and associated expression features are entered into an AI-based drug-prediction model to generate a prioritized list of repurposing candidates.

Personalized Treatment Implementation: AI-guided candidate therapies are integrated with the clinical risk profile to inform selection of neoadjuvant or adjuvant strategies.

For example, a patient with high surgical risk and locally advanced disease who exhibits a VEGFA-high subtype could be considered for neoadjuvant therapy with an AI-prioritized anti-angiogenic agent (e.g., pazopanib). This rationale reflects the limited response rates of currently used systemic regimens (e.g., doxorubicin, gemcitabine–docetaxel, and trabectedin), which constrains routine use of neoadjuvant therapy in RLMS. The AI-guided strategy aims to prioritize subtype-matched agents with the potential to improve response. The goal is to facilitate technical downstaging while concurrently targeting biological aggressiveness. After therapy, restaging—and, when feasible, repeat biopsy—could inform subsequent treatment selection, enabling an adaptive, feedback-informed workflow. For patients with recurrent, unresectable disease, AI-prioritized regimens may provide biologically grounded systemic options for evaluation. This strategy is intended to align macroscopic anatomic constraints with molecular tumor biology within a single decision framework.

2 Discussion and future perspectives

Integrating transcriptomic subtyping, surgical risk stratification, and AI-guided drug repurposing may enable a substantively different approach to RLMS management. This framework supports a dynamic, individualized precision-oncology model in which treatment selection is informed by both molecular and surgical risk features. By prioritizing existing drugs for repurposing, the strategy may shorten development timelines and reduce costs relative to de novo drug development. The proposed framework differs from prior work in three respects: (1) it integrates quantitative surgical risk tools (e.g., SARCO-M): with transcriptomic subtypes to inform therapy selection; (2) it emphasizes training and/or validating AI models using RLMS-relevant perturbation data to improve model relevance; (3) it proposes an adaptive management loop in which treatment is iteratively updated based on longitudinal molecular and clinical assessment. Collectively, these elements extend beyond generic precision-oncology frameworks by explicitly accounting for disease-specific surgical constraints and molecular context in therapeutic decision-making.

However, several methodological and translational challenges remain.

Data scarcity and model robustness: Establishing large, well-annotated RLMS biobanks with linked clinical and multi-omics data is important but difficult given disease rarity. To address this limitation, future work should prioritize collaborative frameworks (e.g., federated learning) that enable multi-institutional model training without exchange of raw patient-level data. In addition, in silico modeling based on pathway-level perturbations may help prioritize candidate drugs when patient-derived training data are limited. Recent AI-focused reviews suggest that hybrid strategies—combining real-world biobanking with computational augmentation—may be a pragmatic route toward more robust and clinically applicable models in rare cancers (21).

Algorithm transparency: Limited interpretability of some models motivates development of explainable AI (XAI) methods to improve transparency, support clinical trust, and provide pathway-level biological context (54).

Preclinical and clinical validation: Prospective testing of AI-prioritized drugs in physiologically relevant preclinical models (e.g., PDXs) is an important intermediate step. Future clinical trials should be biomarker driven, enrolling patients by molecular subtype to evaluate the efficacy of repurposed agents in appropriately selected populations.

3 Conclusion

In conclusion, this review outlines a novel integrative paradigm that converges surgical oncology, multi-omics, and computational pharmacology—an approach that has not been systematically articulated for RLMS. By integrating anatomic risk with molecular vulnerabilities using AI, an actionable roadmap to accelerate hypothesis-driven development of personalized therapies for this malignancy is provided.

RLMS remains associated with limited effective systemic treatment options and poor outcomes. The convergence of advanced omics technologies, AI methods, and refined clinical stratification provides an opportunity to improve therapeutic development and evaluation in RLMS. By developing an integrated disease model spanning operative findings and molecular profiling, the field can systematically prioritize and test repurposing hypotheses for existing drugs. This integrative, AI-guided framework can accelerate generation and evaluation of personalized treatment hypotheses and, with rigorous validation, improve outcomes for patients with RLMS.

Statements

Author contributions

NJ: Writing – original draft. ZB: Writing – original draft. ZZ: Writing – review and editing. KW: Writing – original draft. YL: Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by Hebei Provincial Key Research and Development Program (22377702D).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

RLMS, Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma; AI, artificial intelligence; HDAC, histone deacetylase; RPS, Retroperitoneal sarcomas.

References

1.

Sassa N . Retroperitoneal tumors: review of diagnosis and management. Int J Urol (2020) 27:1058–70. 10.1111/iju.14361

2.

van Houdt WJ Zaidi S Messiou C Thway K Strauss DC Jones RL . Treatment of retroperitoneal sarcoma: current standards and new developments. Curr Opin Oncol (2017) 29:260–7. 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000377

3.

Dingley B Fiore M Gronchi A . Personalizing surgical margins in retroperitoneal sarcomas: an update. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther (2019) 19:613–31. 10.1080/14737140.2019.1625774

4.

Strauss DC Hayes AJ Thway K Moskovic EC Fisher C Thomas JM . Surgical management of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma. Br J Surg (2010) 97:698–706. 10.1002/bjs.6994

5.

MacNeill AJ Miceli R Strauss DC Bonvalot S Hohenberger P Van Coevorden F et al Post-relapse outcomes after primary extended resection of retroperitoneal sarcoma: a report from the trans-atlantic RPS working group. Cancer (2017) 123:1971–8. 10.1002/cncr.30572

6.

Landuzzi L Ruzzi F Lollini P-L Scotlandi K . Chondrosarcoma: new molecular insights, challenges in near-patient preclinical modeling, and therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci (2025) 26:1542. 10.3390/ijms26041542

7.

Behjati S Tarpey PS Haase K Ye H Young MD Alexandrov LB et al Recurrent mutation of IGF signalling genes and distinct patterns of genomic rearrangement in osteosarcoma. Nat Commun (2017) 8:15936. 10.1038/ncomms15936

8.

Hettmer S Li Z Billin AN Barr FG Cornelison DDW Ehrlich AR et al Rhabdomyosarcoma: current challenges and their implications for developing therapies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med (2014) 4:a025650. 10.1101/cshperspect.a025650

9.

Xu L . Crosstalk of three novel types of programmed cell death defines distinct microenvironment characterization and pharmacogenomic landscape in breast cancer. Front Immunol (2022) 13:942765. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.942765

10.

Cotto KC Wagner AH Feng Y-Y Kiwala S Coffman AC Spies G et al DGIdb 3.0: a redesign and expansion of the drug-gene interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res (2018) 46:D1068–73. 10.1093/nar/gkx1143

11.

Minard-Colin V Walterhouse D Bisogno G Martelli H Anderson J Rodeberg DA et al Localized vaginal/uterine rhabdomyosarcoma-results of a pooled analysis from four international cooperative groups. Pediatr Blood Cancer (2018) 65:e27096. 10.1002/pbc.27096

12.

Affinita MC Merks JHM Chisholm JC Haouy S Rome A Rabusin M et al Rhabdomyosarcoma with unknown primary tumor site: a report from European pediatric soft tissue sarcoma study group (EpSSG). Pediatr Blood Cancer (2022) 69:e29967. 10.1002/pbc.29967

13.

Di Carlo D Fichera G Minard-Colin V Coppadoro B Orbach D Cameron A et al Prognostic role of bone erosion in orbital RMS: a report from the European pediatric soft tissue sarcoma study group (EpSSG). Front Oncol (2024) 14:1497193. 10.3389/fonc.2024.1497193

14.

Phelps MP Bailey JN Vleeshouwer-Neumann T Chen EY . CRISPR screen identifies the NCOR/HDAC3 complex as a major suppressor of differentiation in rhabdomyosarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2016) 113:15090–5. 10.1073/pnas.1610270114

15.

Lanzi C Favini E Dal Bo L Tortoreto M Arrighetti N Zaffaroni N et al Upregulation of ERK-EGR1-heparanase axis by HDAC inhibitors provides targets for rational therapeutic intervention in synovial sarcoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2021) 40:381. 10.1186/s13046-021-02150-y

16.

Tseng WW Barretta F Conti L Grignani G Tolomeo F Albertsmeier M et al Defining the role of neoadjuvant systemic therapy in high-risk retroperitoneal sarcoma: a multi-institutional study from the transatlantic australasian retroperitoneal sarcoma working group. Cancer (2021) 127:729–38. 10.1002/cncr.33323

17.

Zhang E Li Y Ma L Ji D Zhang M Lang N . Development and validation of a multiphase computed tomography-based radiomics classifier for differentiating retroperitoneal non-fatty dedifferentiated liposarcoma from leiomyosarcoma. Abdom Radiol (Ny) (2025). 10.1007/s00261-025-05222-1

18.

Gronchi A Strauss DC Miceli R Bonvalot S Swallow CJ Hohenberger P et al Variability in patterns of recurrence after resection of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma (RPS): a report on 1007 patients from the multi-institutional collaborative RPS working group. Ann Surg (2016) 263:1002–9. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001447

19.

Bonvalot S Gronchi A Le Péchoux C Swallow CJ Strauss D Meeus P et al Preoperative radiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for patients with primary retroperitoneal sarcoma (EORTC-62092: STRASS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2020) 21:1366–77. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30446-0

20.

Yuan H Yu K Xie F Liu M Sun S . Automated machine learning with interpretation: a systematic review of methodologies and applications in healthcare. Med Adv (2024) 2:205–37. 10.1002/med4.75

21.

Raj GM Dananjayan S Gudivada KK . Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in clinical medicine: what lies ahead?Med Adv (2024) 2:202–4. 10.1002/med4.62

22.

Fang C Liu J Fan Y Yang J Xiang N Zeng N . Outcomes of hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis based on 3-dimensional reconstruction technique. J Am Coll Surg (2013) 217:280–8. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.03.017

23.

Shaaban AM Rezvani M Tubay M Elsayes KM Woodward PJ Menias CO . Fat-containing retroperitoneal lesions: imaging characteristics, localization, and differential diagnosis. Radiographics (2016) 36:710–34. 10.1148/rg.2016150149

24.

Demicco EG Wagner MJ Maki RG Gupta V Iofin I Lazar AJ et al Risk assessment in solitary fibrous tumors: validation and refinement of a risk stratification model. Mod Pathol (2017) 30:1433–42. 10.1038/modpathol.2017.54

25.

Bonvalot S Rivoire M Castaing M Stoeckle E Le Cesne A Blay JY et al Primary retroperitoneal sarcomas: a multivariate analysis of surgical factors associated with local control. J Clin Oncol (2009) 27:31–7. 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0802

26.

Gaignard E Bergeat D Robin F Corbière L Rayar M Meunier B . Inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma: what method of reconstruction for which type of resection?World J Surg (2020) 44:3537–44. 10.1007/s00268-020-05602-2

27.

Miah AB Hannay J Benson C Thway K Messiou C Hayes AJ et al Optimal management of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma: an update. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther (2014) 14:565–79. 10.1586/14737140.2014.883279

28.

Fairweather M Raut CP . ASO author reflections: rationale for organ resection for retroperitoneal sarcomas. Ann Surg Oncol (2018) 25:940–1. 10.1245/s10434-018-6979-3

29.

ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol (2014) 25(Suppl. 3):iii102–112. 10.1093/annonc/mdu254

30.

Callegaro D Miceli R Mariani L Raut CP Gronchi A . Soft tissue sarcoma nomograms and their incorporation into practice. Cancer (2017) 123:2802–20. 10.1002/cncr.30721

31.

Geady C Bannon JJ Reza S Madanat-Harjuoja L Reinke D Schuetze S et al Measured intrapatient radiomic variability as a predictor of treatment response in multi-metastatic soft tissue sarcoma patients. Sci Rep (2025) 15:27838. 10.1038/s41598-025-12451-3

32.

Swallow CJ Strauss DC Bonvalot S Rutkowski P Desai A Gladdy RA et al Management of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma (RPS) in the adult: an updated consensus approach from the transatlantic australasian RPS working group. Ann Surg Oncol (2021) 28:7873–88. 10.1245/s10434-021-09654-z

33.

Pestana RC Roszik J Groisberg R Sen S Van Tine BA Conley AP et al Discovery of targeted expression data for novel antibody-based and chimeric antigen receptor-based therapeutics in soft tissue sarcomas using RNA-sequencing: clinical implications. Curr Probl Cancer (2021) 45:100794. 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2021.100794

34.

Hasegawa N Hayashi T Niizuma H Kikuta K Imanishi J Endo M et al Detection of novel tyrosine kinase fusion genes as potential therapeutic targets in bone and soft tissue sarcomas using DNA/RNA-based clinical sequencing. Clin Orthop Relat Res (2024) 482:549–63. 10.1097/CORR.0000000000002901

35.

Iwata S . CORR insights®: detection of novel tyrosine kinase fusion genes as potential therapeutic targets in bone and soft tissue sarcomas using DNA/RNA-based clinical sequencing. Clin Orthop Relat Res (2024) 482:564–5. 10.1097/CORR.0000000000002998

36.

Mortazavi A Williams BA McCue K Schaeffer L Wold B . Mapping and quantifying Mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-seq. Nat Methods (2008) 5:621–8. 10.1038/nmeth.1226

37.

Qu H Fang X . A brief review on the human encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE) project. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics (2013) 11:135–41. 10.1016/j.gpb.2013.05.001

38.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research NetworkCancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address: elizabeth.demicco@sinaihealthsystem.ca, cancer genome atlas research network. Comprehensive and integrated genomic characterization of adult soft tissue sarcomas. Cell (2017) 171:950–65.e28. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.014

39.

Zhang K Wang H . Cancer genome atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi (2015) 18:219–23. 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2015.04.02

40.

Nishio J Nakayama S Aoki M . Myxoid pleomorphic liposarcoma: a review and update. Cancer Genomics Proteomics (2026) 23:1–11. 10.21873/cgp.20557

41.

Busciglio S Cannizzaro IR Luberto A Taiani A Moschella B Ambrosini E et al The pathogenesis of the neurofibroma-to-sarcoma transition in neurofibromatosis type I: from molecular profiles to diagnostic applications. Cancers (Basel) (2025) 17:3955. 10.3390/cancers17243955

42.

Amjad A Ahmed S Kabir M Arif M Alam T . A novel deep learning identifier for promoters and their strength using heterogeneous features. Methods (2024) 230:119–28. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2024.08.005

43.

Vamathevan J Clark D Czodrowski P Dunham I Ferran E Lee G et al Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov (2019) 18:463–77. 10.1038/s41573-019-0024-5

44.

Subramanian A Narayan R Corsello SM Peck DD Natoli TE Lu X et al A next generation connectivity map: L1000 platform and the first 1,000,000 profiles. Cell (2017) 171:1437–52.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.049

45.

Jiang G Zhang S Yazdanparast A Li M Pawar AV Liu Y et al Comprehensive comparison of molecular portraits between cell lines and tumors in breast cancer. BMC Genomics (2016) 17(Suppl. 7):525. 10.1186/s12864-016-2911-z

46.

Aliper A Plis S Artemov A Ulloa A Mamoshina P Zhavoronkov A . Deep learning applications for predicting pharmacological properties of drugs and drug repurposing using transcriptomic data. Mol Pharm (2016) 13:2524–30. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00248

47.

Swinney DC Anthony J . How were new medicines discovered?Nat Rev Drug Discov (2011) 10:507–19. 10.1038/nrd3480

48.

Yao Q Chen Z Cao Y Hu H . Enhancing drug-target interaction prediction with graph representation learning and knowledge-based regularization. Front Bioinform (2025) 5:1649337. 10.3389/fbinf.2025.1649337

49.

Hamberg P Verweij J Sleijfer S . (pre-)clinical pharmacology and activity of pazopanib, a novel multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor. Oncologist (2010) 15:539–47. 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0274

50.

Kumar R Knick VB Rudolph SK Johnson JH Crosby RM Crouthamel MC et al Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic correlation from mouse to human with pazopanib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor with potent antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Mol Cancer Ther (2007) 6:2012–21. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0193

51.

Bruno M De Paolis E Minucci A Piermattei A Maneri G Santoro A et al Comprehensive genomic profiling and clinico-pathologic characterization of primary ovarian leiomyosarcoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer (2025) 35:102010. 10.1016/j.ijgc.2025.102010

52.

Qadri YA Shaikh S Ahmad K Choi I Kim SW Vasilakos AV . Explainable artificial intelligence: a perspective on drug discovery. Pharmaceutics (2025) 17:1119. 10.3390/pharmaceutics17091119

53.

Dias R Torkamani A . Artificial intelligence in clinical and genomic diagnostics. Genome Med (2019) 11:70. 10.1186/s13073-019-0689-8

54.

Gao XJ Ciura K Ma Y Mikolajczyk A Jagiello K Wan Y et al Toward the integration of machine learning and molecular modeling for designing drug delivery nanocarriers. Adv Mater (2024) 36:e2407793. 10.1002/adma.202407793

Summary

Keywords

artificial intelligence, drug repurposing, precision medicine, retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma, surgical oncology, transcriptomics

Citation

Jia N, Bao Z, Zhang Z, Wang K and Li Y (2026) A new paradigm for retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma: integrating transcriptomic subtyping and surgical risk stratification for AI-guided drug repurposing. Oncol. Rev. 20:1744721. doi: 10.3389/or.2026.1744721

Received

12 November 2025

Revised

09 January 2026

Accepted

19 January 2026

Published

04 February 2026

Volume

20 - 2026

Edited by

Zhuang Aobo, Xiamen University, China

Reviewed by

Prabhjot Mundi, Columbia University, United States

Zhaokai Zhou, Central South University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Jia, Bao, Zhang, Wang and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhidong Zhang, zhang_zhi_dong@hebmu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.