- 1Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Naples, Italy

- 2Institute of Biomolecular Chemistry, National Research Council, Pozzuoli, Italy

- 3Department of Pharmacy, University of Salerno, Salerno, Italy

- 4SDU Biotechnology, Department of Green Technology, Faculty of Engineering, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

The light environment is a key factor regulating the growth and biomass production of microalgae. Photon flux density and spectral composition i.e., the relative contribution of different wavelengths, are among the most important light parameters influencing microalgal efficiency. The red, green and blue bands are used by microalgae as both energy source for photosynthesis and as external cue that triggers biological signaling and physiological adjustments. This study mechanistically explores the effects of light modulation on key metabolites in the emerging model Odontella aurita, the only diatom species currently approved as a food supplement in the EU. Four spectral compositions with red (590–656 nm) ranging from 0% to 60% and blue (422–496 nm) from 60% to 20% were set up under two light conditions: limiting and saturating intensities. Growth and photosynthetic performances were assessed, together with a wide set of metabolites involved in various biochemical pathways including vitamins (A, B1, B2, B6, B8, B9, B12, K1, D2, D3, C and E), auxin, amino acids and other compounds identified by NMR. In addition, the biomass was characterized for its macromolecular composition, carotenoids, phytosterols, total flavonoid and total phenolic content, iron and zinc content, and total antioxidant capacity of the biomass using different assays were evaluated. Results revealed the complementary roles of blue and red lights: blue light enhanced growth and photosynthesis, as well as the use or regulation of photoenergy, whereas red light promoted the regulation of key metabolites e.g., B vitamins or auxin, involved in the modulation of metabolic pathways. These findings provide insight for optimizing diatom cultivation under controlled light environments e.g., with the aim to boost growth and metabolism.

1 Introduction

Light environment is one of the main drivers for phototrophic life, strongly determining the capacity of organisms to grow and produce biomass (Duchene et al., 2025; Prasil et al., 2024). Photosynthesis, growth and cell division are interconnected (Morales et al., 2018; Hoppe et al., 2024; Songserm et al., 2024), even though not always correlated (Giovagnetti et al., 2010; 2012), since they depend on intracellular metabolic fluxes that govern carbon allocation and regulatory processes. Light conditions greatly impact intracellular carbon allocation (Wagner et al., 2017), through traits ascribable to both intensity and spectral composition (Rockwel et al., 2014; Huysman et al., 2013; Lockhart, 2013; de Mooij et al., 2016; Jaubert et al., 2017; Wiltbank and Kehoe, 2019; Falciatore et al., 2022; Bialevich et al., 2022; Broddrick et al., 2022; Agarwal et al., 2023).

From an ecological perspective, time and space variability in light intensity and wavelength are wider in the Ocean compared to land (Duchene et al., 2025). Red light intensity declines faster in water than blue or green light as you go deeper. The ratio of red to blue or green light is well balanced at the surface and decreases exponentially, approaching zero with increasing depth. In coastal and estuarine environments, green light predominates over blue, whereas blue light prevails in offshore or oligotrophic waters. Thus, the presence and intensity of red light can serve as a proxy for the light condition: its absence indicates low irradiance, while increasing red intensity reflects progressively higher light levels. Besides the photoreceptors, within a physiological context, red light is mainly absorbed by chlorophylls while blue is harvested by a greater diversity of molecules, chlorophylls, carotenoids, flavonoids (Liu and van Iersel, 2021), and other active molecules in biochemical pathways, such as FAD (Masuda et al., 2004; He et al., 2024) and vitamin B12 (Padmanabhan et al., 2022).

Free-living photosynthetic organisms, such as microalgae must therefore adapt to a wide range of light conditions, using light both as an energy source to perform photosynthesis and as environmental signal, that triggers biological adjustments (Brunet et al., 2014; Falciatore et al., 2022; Duchene et al., 2025). Spectral sensing and the subsequent intracellular responses, activating or inhibiting biosynthetic pathways, are mainly mediated primarily by photoreceptors (Coesel et al., 2009; Bailleul et al., 2010; Schellenberger Costa et al., 2013; Jungandreas et al., 2014; Wilhelm et al., 2014; Shankar et al., 2022; Falciatore et al., 2022; Zhang P. et al., 2022; Strauss et al., 2023; Mann et al., 2020; Im et al., 2024). It is well known that light spectral composition affects microalgae physiology (Falciatore et al., 2022), yet its impact depends strongly on PAR (Photosynthetically Active Radiation) intensity (Brunet et al., 2014; Pistelli et al., 2023). Indeed, the combination of intensity and spectral composition generates a complex light signal within the 3D water column ecosystem, which cells use to optimize photosynthesis and photoregulation (Pistelli et al., 2023) defined a quantitative index - the Light Energy Index (rel-LEi) - combining color (RGB) intensity and contribution. It corresponds to the sum of the photon flux density of the blue, green and red wavelengths, weighted by their relative photon energy. A higher blue contribution increases rel-LEi, whereas a stronger red contribution decreases it. In this study, the rel-LEi was applied for the cultivation of the centric diatom O. aurita cultivation. This species was selected being an emerging model species (Zhang H. et al., 2022; Ragueneau et al., 2025), the only diatom currently approved as food supplement by the EFSA authority in Europe. It is a high source of polyunsaturated fatty acids (An et al., 2023; Pasquet et al., 2014; Xia et al., 2018), fucoxanthin (Keerthi et al., 2013; Xia et al., 2013; Zhang P. et al., 2022; An et al., 2024) and chrysolamiranin (Xia et al., 2014; 2018), with proven bioactive properties (Moreau et al., 2006; Haimeur et al., 2012; Mimouni et al., 2015; Amine et al., 2016; Hemalatha et al., 2017; Cuong et al., 2024). From an evolutionary perspective, O. aurita belongs to a transition segment from centric pelagic to benthic pennate diatoms (Nonoyama et al., 2019; Sato et al., 2020). Ecologically, O. aurita is widely distributed across temperate coastal areas.

The general aim of the study was to explore how the metabolism of the diatom O. aurita is related to a spectrally-driven photoresponse, i.e. how does the spectral composition shape the PAR intensity response—photoacclimation—of a diatom? Two different PAR conditions, one limiting and one saturating, each generated with four distinct spectral (RGB) compositions, were compared. The mechanistic approach adopted in this study is propaedeutic to tackle the following topics: (i) the “red gradient” to explore if the diatom photoresponse to light intensity is affected by the red:blue ratio, (ii) the spectral and intensity interactions to explore if the spectrally driven photoresponse is shaped by light intensity? and (iii) the “red On/Off” to investigate if the absence of red light alters the photoresponse compared with the same light intensity containing low-level red.

This study emphasizes the effect of light condition on the physiology and the accumulation of key metabolites of O. aurita, such as vitamins, auxin, and amino acids, which play a crucial role in signaling, metabolism, and the homeostasis of photosynthetic organisms (Raschke et al., 2007; Fitzpatrick and Chapman, 2020; Hanson et al., 2000; Fitzpatrick, 2024) while highlighting the lack of information and understanding in microalgae such as diatoms (Del Mondo et al., 2021). The dataset generated in this work covers key biological functions, such as photosynthesis-growth, metabolism-homeostasis and nutrition-interactions: growth and photosynthetic rates, vitamins A, B1, B2, B6, B8, B9, B12, K1, D2, D3, C and E, auxin, amino acids and other small molecules identified from NMR analysis, together with the macromolecular composition, phytosterols, total flavonoids, total phenolic, carotenoids, iron, zinc, and total antioxidant capacity of the biomass (e.g., ORAC, ABTS, FRAP).

Our results highlight how red and blue light differentially modulate metabolites, particularly vitamins and auxin, in diatoms. This information and dataset will be relevant for biotechnological applications involving diatoms (Sansone et al., 2024), systems biology and marine microbiology (Panahi et al., 2020; 2024), synthetic biology (Naduthodi et al., 2021) and biological or ecological modeling (Flynn et al., 2025).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 The Odontella aurita model and experimental design

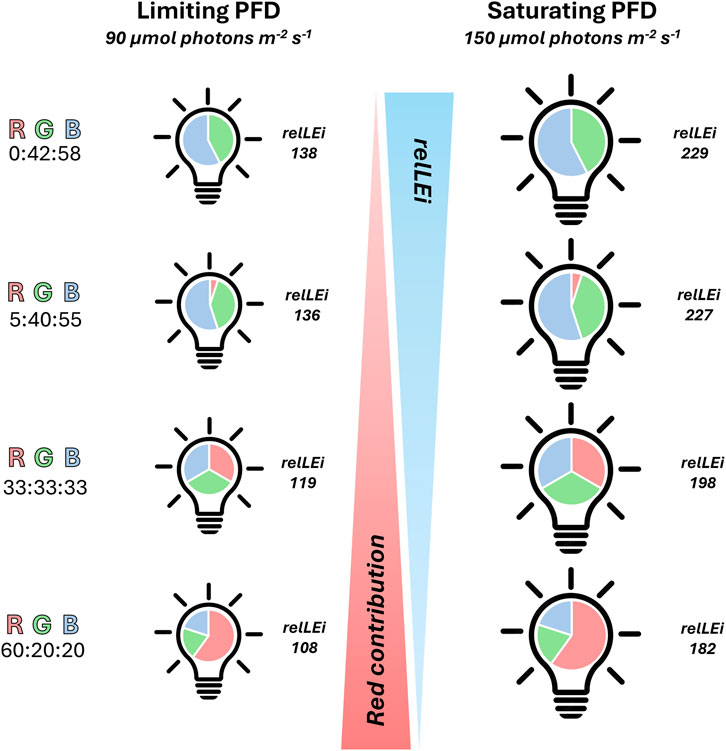

The diatom O. aurita (strain K-1252) was purchased from NORCCA (the Norwegian Culture Collection of Algae, https://norcca.scrol.net). The non-axenic culture of O. aurita was grown at 20 °C in a 3-L glass aquarium containing autoclaved seawater, pre-filtered through a 0.7 μm GF/F glass–fiber filter and amended with f/2 culture medium. Eight light conditions were set up using a patented custom-built LED illumination system (Pistelli et al., 2023) providing a sinusoidal light distribution with a 12h:12h light:dark photoperiod. Four limiting-light (peak irradiance = 90 µmol photons m-2 s-1), and four saturating-light conditions (peak irradiance = 150 µmol photons m-2 s-1) were applied. Within each light intensity regime, four spectral compositions were tested (RGB = 0:42:58, 5:40:55, 33:33:33, 60:20:20; Figure 1). Blue light peaked at 460 nm (422–496 nm), green at 530 nm (480–580 nm) and red at 630 nm (590–656 nm). Light intensity was measured inside each tank with a PAR 4π sensor (QSL 2101, Biospherical Instruments Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), while the spectral composition was measured using a spectroradiometer (Hyper OCR I, Satlantic, Halifax, CA, USA).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the experimental conditions. Four spectral compositions were tested (RGB % = 0:42:58, 5:40:55, 33:33:33, 60:20:20). Blue (422–496 nm), green (480–580 nm) and red light (590–656 nm). On the left side the four limiting light conditions, on the right side the saturating light conditions. Photoperiod: 12h:12h light:dark. RGB = Red Green Blue; PAR, in μmol photons m-2s-1; rel-LEi, in μmol photons m-2s-1. Rel-LEi: relative light energy index (estimated according to Pistelli et al. (2023)).

The spectral light intensity was adjusted independently for each wavelength to the value requested during the midday peak using the PAR 4π sensor (QSL 2101). Once this process has been completed successively for the three wavelengths, the PAR intensity of the white light (the sum of red, blue, and green) was verified. The relative light energy index (rel-LEi) was estimated according to Pistelli et al. (2023).

All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Cells were acclimated to the experimental conditions for 2 weeks in a 3-L glass aquarium, during which growth was monitored daily, and medium was added or removed to control biomass development. Cells were counted daily with a Zeiss Axioskop 2 Plus light microscope, with a Sedgewick Rafter counting cell chamber (Pistelli et al., 2021a).

Experiments started with a cell concentration ≈10,174 ± 2,290 cells mL-1, and ended during the exponential growth phase (3 days after onset), with a cell concentration ≈25,429 ± 3,650 cells mL-1. Sampling was done during the dark period before dawn, and before the end of the exponential phase.

Cells were harvested under laminar flow hood using a plankton net (mesh size 40 μm). Then, the biomass from the net was collected in a reduced volume of medium (50 mL) and centrifuged at 2,000 x g for 15 min at 4 °C (DR15P centrifuge, B. Braun Biotech International, Melsungen, Germany). Pellets were weighed, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, stored at −20 °C, and subsequently lyophilized in a Freeze Dryer Modulyo (Edwards). Dry weight was measured (mg DW).

2.2 Light absorption capacity and photosynthetically usable radiations (PUR)

Spectral absorption measurements were performed with a spectrophotometer (Agilent Cary UV-Vis Compact Peltier). Absorption characteristics were measured between 200 and 800 nm to obtain spectral values of the absorption coefficient (m-1) for each wavelength. From the visible part of the spectrum (400–700 nm), the absorption at each wavelength (a(λ)) was integrated (m2) and then normalized to cell concentration to obtain the cell-specific absorption coefficient (a*, m2 cell-1). PUR (photosynthetically usable radiation, Brunet et al., 2014) was thus determined as: PUR(λ) = PAR(λ) x a*(λ). Using the cell-specific absorption coefficient in m2 cell-1, PUR value was thus reported on a cell basis, as PUR cell-1 (µmol photons s-1 cell-1).

2.3 Short incubations for net photosynthesis and respiration rates measurements

Oxygen production in the light i.e., net photosynthesis, and the oxygen consumption in dark i.e., respiration rate, were determined on 50 mL culture subsamples in 6h incubations. Culture subsamples were collected in duplicate in tissue culture flasks right before the start of the light period from each triplicate of the mother culture and kept in their same experimental condition. One of the subsamples was kept in the light and experienced the circadian illumination cycle, from dawn to midday peak, while the other was wrapped in aluminum foil to shield it from light. Dissolved oxygen concentration was measured at the beginning and at the end of the incubation on samples collected form each incubation flask in 12 mL exetainers and fixed by adding 100 µL of 7M ZnCl2. These samples were stored at 4 °C until analysis and analyzed by Membrane Inlet Mass Spectrometry (MIMS, Bay Instruments). Oxygen fluxes - net photosynthesis and respiration rates (O2 pmol cell -1 h-1) - were calculated as follows:

where (O2)t0 and (O2)t6 are the oxygen concentration respectively at the beginning and at the end of the incubation, t is the incubation time (6h) and (cells) is the cell abundance (cells L-1) measured at the beginning of the incubation.

The analysis was run at constant temperature of 20 °C. Ion currents of O2 (mass 32) were registered every 15s for four times from each sample to ensure signal stability. Seawater standards were used to correct for the instrument drift by measuring them every 1h during samples analysis. The standard seawater consisted in 0.2 μm filtered seawater of the same salinity as the samples (38) equilibrated with air by stirring at 20 °C for at least 2h before the analysis. Measures of the air- equilibrated standards were also used as internal calibration to convert the ion currents into gas concentration.

2.4 Biomass composition

2.4.1 Total proteins

Protein content was estimated on aliquots of subsamples of 5 mg DW biomass, following the protocol of Pistelli et al. (2021a).

2.4.2 Total carbohydrates

Total carbohydrate content was determined on 5 mg DW biomass using the phenol sulfuric acid method, described in Pistelli et al. (2021a).

2.4.3 Total lipids and phytosterols

The total lipid content was estimated on aliquots of 5 mg DW biomass, applying the method previously described by Pistelli et al. (2021a). From these samples, the total sterol content was estimated (Pistelli et al., 2021a).

2.5 Metals

2.5.1 Zinc

Zinc concentration in the O. aurita biomass was quantified by using the Zinc Quantification Kit (Cat. No. ab176725, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The assay was performed in triplicate, as follow. Aliquots of 5 mg DW biomass were dissolved in 500 μL RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer (Cat. No. 89900, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and sonicated at 4 °C for 90 s in pulse mode (30 s ON – 30 s OFF – 30 s ON; 70 W maximum output power; 30% of amplitude) with aSONOPULS HD 2070.2 (BANDELIN, Berlin, Germany).

Samples were centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 5 min at 4 °C (Sigma 3-18KS, Sigma Laborzentrifugen, Osterode am Harz, Germany). Cell lysates were then deproteinized adding an equal volume of 7% trichloroacetic acid and centrifuging at 13,000 x g for 5 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were neutralized with 1 M sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, CAS No. 497-19-8; Cat. No. 131648, AppliChem GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany), vortexed and incubated on ice for 5 min. The assay was performed in a black 96-well plate (Cat. No. 3694, Corning Inc, Corning, NY, USA), and fluorescence was measured on an Infinite® M1000 PRO (Ex: 485 nm, Em: 525 nm; TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland). Zinc concentration (pmol. Zn2+ mg-1DW) was calculated from a calibration curve obtained by using zinc chloride (ZnCl2) as standard.

2.5.2 Iron

An aliquot of 5 mg DW biomass was dissolved in 200 μL Iron Assay Buffer. Samples were sonicated at 4 °C for 10 s at 10% of amplitude (70 W maximum output power) with a SONOPULS HD 2070.2 (BANDELIN, Berlin, Germany) and centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were transferred into fresh tubes. From each sample, 50 μL were dispensed into two 96-well plates, one dedicated for the determination of ferrous iron (Fe2+) and one for the determination of total iron. The volume in each well was adjusted to 100 µL with Iron Assay Buffer. Then for total iron determination, 5 μL of Iron Reducer were added, while for ferrous (Fe2+) iron determination, 5 μL of Iron Assay Buffer were added. The plate was incubated on horizontal shaker for 30 min at RT in the dark. Afterwards, 100 μL of Iron Probe were added to each well, and the plate was then incubated again in the same conditions for 1h. The absorbance was measured at 593 nm using a spectrophotometer, and iron concentrations were calculated based on a standard calibration curve.

2.6 Carotenoids

Pigment analysis was conducted by HPLC on an aliquot of 10 mg DW biomass, following the protocol reported in Pistelli et al. (2021a). Extraction was done in 100% Methanol, and samples were sonicated for 90 s in pulse mode (30 s ON – 30 s OFF – 30 s ON; 70 W maximum output power; 30% of amplitude). Extracts (three replicates per sample) were injected in a HPLC Hewlett Packard series 1100, equipped with a reversed-phase column (2.6 mm diameter C8 Kinetex column; 50 x 4.6 mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). Determination and quantification of pigments was carried out using pigment standards purchased from the D.H.I. Water and Environment (Danish Hydraulic Institute; Horsholm, Denmark).

2.7 Total phenolic and flavonoid content (TPC, TFC)

The total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) were estimated on aliquots of 5 mg DW biomass. TPC was measured using the performing Folin-Ciocalteu’s, while TFC was determined with aluminium chloride (AlCl3) colorimetric method, as described in Smerilli et al.(2019).

2.8 Vitamins

The content of twelve vitamins i.e., vitamins A, B1, B2, B6, B8, B9, B12, C, D2, D3, E, and K1 was estimated following Pistelli et al. (2021a). Aliquots of 5 mg DW biomass were used to perform a competitive ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; Li et al., 2025) using specific primary antibody for each vitamin (Pistelli et al., 2023). Vitamin quantification was performed using a calibration curve generated from pure vitamin standards (Supplementary Figure 1).

2.9 Antioxidant properties (ABTS, FRAP, ORAC assays)

Antioxidant capacity was evaluated using three different assays: ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid)) assay, following Pistelli et al. (2021a), ORAC (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity), and FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power), all carried out using aliquots of 5 mg DW biomass, according to Pistelli et al.(2023). Results were expressed in μg TE (Trolox Equivalent) mg-1 DW (ABTS) or ng TE mg-1 DW (ORAC and FRAP).

2.10 Auxin

Aliquots of 5 mg DW biomass were used to perform a competitive ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) using a specific primary antibody (anti- Indole-3-acetic acid antibody mouse monoclonal A0855, Sigma). Auxin was quantified using a calibration curve prepared with pure auxin standard (3-indolacetic acid, Sigma, I2886).

2.11 Metabolomics

Combined extraction of polar and lipophilic metabolites was carried out on 40 mg DW biomass using methanol/water/chloroform (Lindon et al., 2005). Polar and nonpolar fractions were transferred into separate glass vials and the solvents were removed on a rotary evaporator at room temperature under reduced pressure. Samples were stored at −80 °C until spectroscopic analysis. Hydrophilic fractions were resuspended in 630 µL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and mixed with 70 µL of 2H2O (containing 1 mM sodium 3-(trimethylsilyl)[2,2,3,3-2H4] propionate) as the 1H chemical-shift reference and for field-frequency lock, to a final volume 700 µL. Samples were loaded into the auto-sampler and NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance III–600 MHz spectrometer (BrukerBioSpin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany), equipped with a TCI CryoProbe with a Z-axis gradients, at 27 °C. In particular, standard 1D proton spectra and 2D experiments (clean total-correlation spectroscopy TOCSY with DIPSI pulse scheme, heteronuclear single quantum coherence HSQC, and heteronuclear multiple bound correlation HMBC 1H-13C) were acquired providing monodimensional metabolic profiles and homonuclear and heteronuclear spectra for metabolites identification. Metabolites assignment was achieved by comparing chemical shifts with literature (Fan, 1996) and online databases (Wishart et al., 2022). Spectra were automatically reduced to 450 integral segments of 0.02 ppm across 0.60–9.60 ppm, excluding the water resonance (4.60–5.16 ppm) using the AMIX 3.9.15 software package (Bruker Biospin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany). After reduction, the NMR data bins were normalized to the total spectrum area. The resulting matrix was imported into SIMCA-P+14 package (Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden) for multivariate analysis, and orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) was applied. A typical NMR spectrum of the polar fraction of O. aurita is reported in supplementary information (Supplementary Figure 2).

2.12 Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Means and standard deviation (SD) were calculated using the PAST software package, v.3.10 (Hammer et al., 2001). Spearman’srank correlation between the different variables, Student’s t-test and Mann–Whitney tests were carried out in PAST software package, v.3.10 (Hammer et al., 2001). The network relationships plots were generated with the on-line tool Graph Commons (https://graphcommons.com).

3 Results

3.1 Growth, photobiological properties and oxygen flux

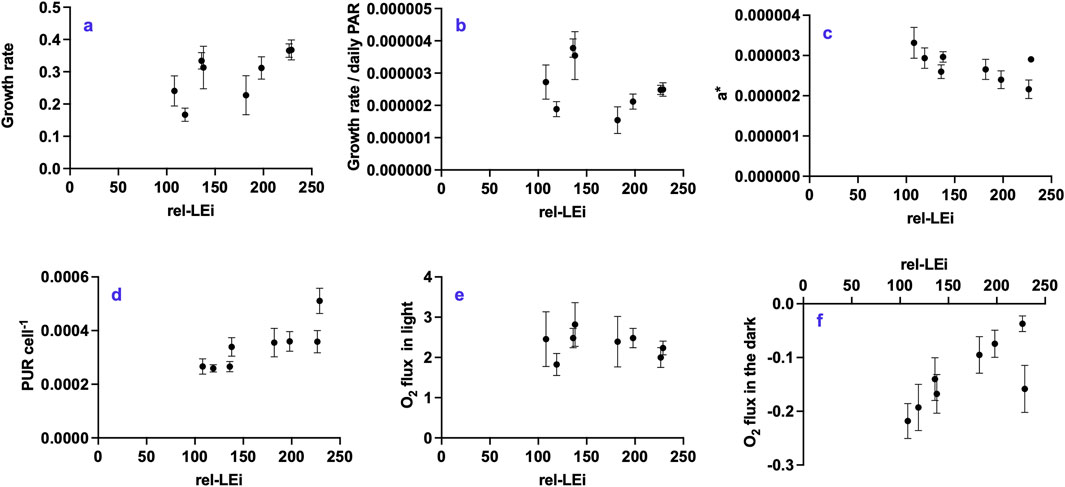

Growth rate was significantly related to rel-LEi (p < 0.001, Figure 2a; Supplementary Table 1) and to blue light intensity (Supplementary Table 2), whereas red light intensity negatively affected growth rate and growth efficiency per daily PAR ((μmol.m-2)−1); Supplementary Table 3). Growth efficiency per daily PAR displayed two distinct significant relationships with rel-LEi with respect to the PAR values (at least p < 0.05; Figure 2b) or with blue contribution (at least p < 0.05). The significant negative relationship between the cell-specific absorption coefficient (a*, m2 cell-1) and rel-LEi (Figure 2c) revealed an ongoing acclimation process in O. aurita to light conditions. Additionally, the absence versus presence of red light (0% vs. 5%) at the two PAR values determined a significant increase of a* (p < 0.05 at low PAR; p < 0.01 at high PAR; Figure 2c). The PUR (Photosynthetically Usable Radiation) was higher under high PAR than under low PAR intensity (p < 0.001), and increased with the rel-LEi (Figure 2d). Similar to a*, the PUR was higher under 0% red compared to 5% red in both low and high PAR values (p < 0.05; Figure 2d). The light-related oxygen production was more variable under low-PAR conditions (CV = 22%) than under high-PAR conditions (CV = 16%; p < 0.01), showing no consistent trend across the eight light climates (Figure 2e). Conversely, the respiration rate was significantly related to the rel-LEi (r = 0.50; p < 0.05; Figure 2f), being significantly higher in cells grown at low PAR (p < 0.05). The absence of red light (0%) compared to its presence (5%) induced a significant increase in respiration rate under both PAR intensity conditions (p < 0.05; Figure 2f). Respiration rate was inversely correlated with absorption coefficient (a*, r = −0.67; n = 24; p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Distribution of the physiological parameters with respect to the rel-LEi (μmol photons m-2s-1): (a) growth rate (d-1); (b) growth rate/daily PAR ratio ((μmol photons m-2)−1); (c) a* (m2 cell-1); (d) PUR cell-1 (μmol photons s-1 cell-1); (e) O2 flux (pmol h-1 cell -1) during incubation in light; (f) O2 flux (pmol h-1 cell -1) during incubation in dark. Rel-LEi: relative light energy index (estimated according to Pistelli et al. (2023)).

3.2 Biomass composition

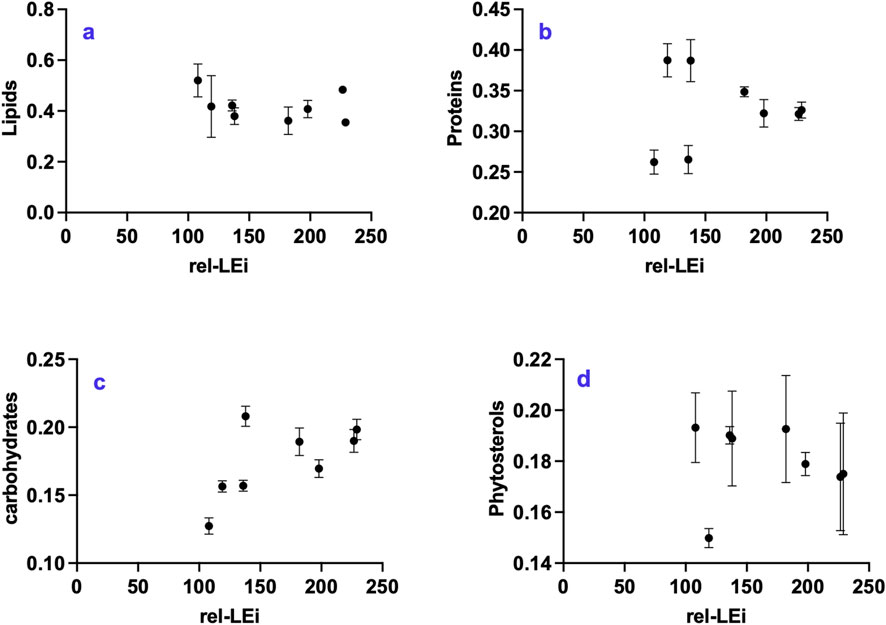

The lipid, protein, and carbohydrate contents were approximately 42.0% (±5.8%), 32.7% (±4.8%) and 17.5% (±2.6%), respectively (Figures 3a–c). Lipids and carbohydrates followed opposite trends (p < 0.05; Figures 3a,c). Within the low PAR intensity cluster, lipids decreased with increased blue contribution (p < 0.01) whereas carbohydrates increased (p < 0.05). Protein content was stable under high PAR, while highly variable within the low PAR cluster (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. Distribution of primary metabolite classes with respect to the rel-LEi (μmol photons m-2s-1): (a) Lipids (mg mg-1 DW); (b) proteins (mg mg-1 DW); (c) carbohydrates (mg mg-1 DW); (d) sterols (mg mg-1 DW). Rel-LEi: relative light energy index (estimated according to Pistelli et al. (2023)).

The absence of red light (0%) compared to its presence (5%) significantly decreased lipid content under high PAR (p < 0.001; Figure 3a), while significantly increasing carbohydrate and protein contents under low PAR (p < 0.001; Figure 3c). Lipid content and respiration rate were negatively correlated within the low PAR cluster (p < 0.05), but positively correlated within the high PAR cluster (p < 0.01).

The phytosterol content was approximately 18.0% ± 1.4% (Figure 3d). Its ratio to total lipids decreased with increasing red intensity (Supplementary Table 3).

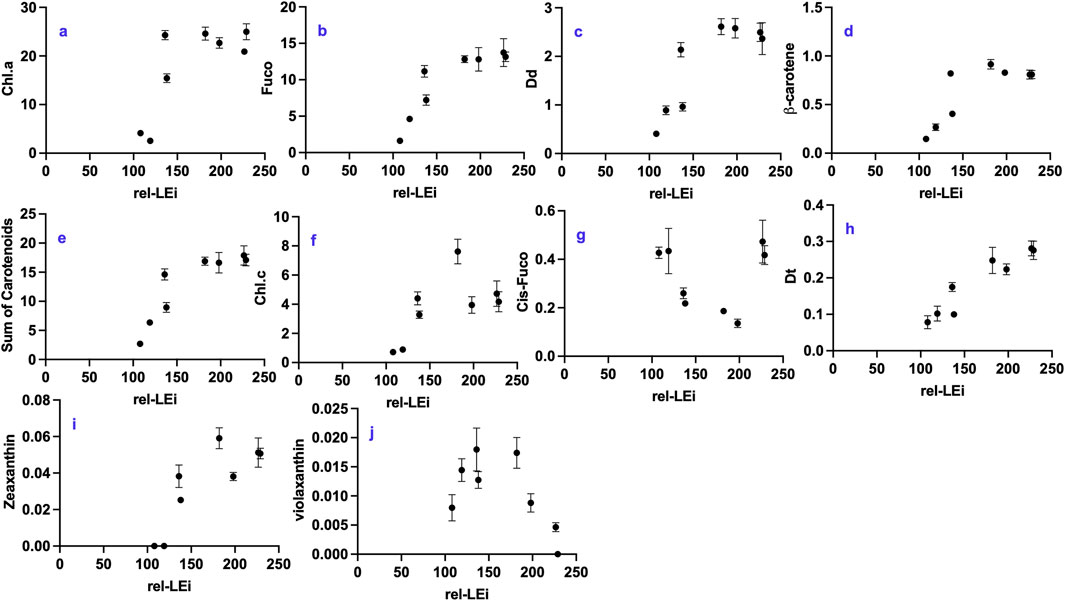

3.3 Pigments

Blue light intensity was found to be the major factor driving the concentrations of pigments, including chlorophyll a (Chl.a), and all carotenoids (Supplementary Table 2). Only violaxanthin decreased with increasing blue intensity (Supplementary Table 2). Chl.a, fucoxanthin (Fuco), diadinoxanthin (Dd), ß-carotene (ß-car), and the sum of carotenoids followed a similar trend: increasing with rel-LEi within the low PAR intensity cluster and reaching a plateau under high PAR intensity (Figures 4a–e). The absence of red light (0%) compared to its presence (5%) under low PAR significantly decreased their concentrations (p < 0.05). Chl.c showed a similar pattern, except that the greatest concentration occurred under high red contribution within the high PAR cluster (Figure 4f). The cis-fucoxanthin concentration was higher under both low and high rel-LEi values i.e., under high red at low PAR and low red at high PAR (Figure 4g).

Figure 4. Distribution of pigment concentrations with respect to the rel-LEi (μmol photons m-2s-1): (a) Chlorophyll a (Chl.a, μg mg-1 DW); (b) fucoxanthin (fuco, μg mg-1 DW); (c) Diadinoxanthin (Dd, μg mg-1 DW); (d) ß-carotene (μg mg-1 DW); (e) sum of carotenoids (μg mg-1 DW); (f) Chlorophyll c (Chl.c; μg mg-1 DW); (g) Cis-fucoxanthin (cis-fuco; μg mg-1 DW); (h) Diatoxanthin (Dt, μg mg-1 DW); (i) Zeaxantin (zea; μg mg-1 DW); (j) Violaxanthin (viol; μg mg-1 DW). Rel-LEi: relative light energy index (estimated according to Pistelli et al., 2023).

Diatoxanthin (Dt) was detected under all eight light conditions (Figure 4h), even though sampling occurred during darkness before dawn (Figure 4h). Dt was linearly correlated with rel-LEi (r = 0.87; p < 0.001, Figure 4h), suggesting that its content depended on both light intensity and blue light contribution. Zeaxanthin (Zea) and violaxanthin (Viol), the two precursors of Dd and Dt, belonging to the other xanthophyll cycle, exhibited opposite trends with rel-LEi: Viol decreased, whereas Zea increased (Figures 4i,j). Additionally, Dt was significantly correlated with both Dd (r = 0.87) and Zea (r = 0.88; n = 24; p < 0.001).

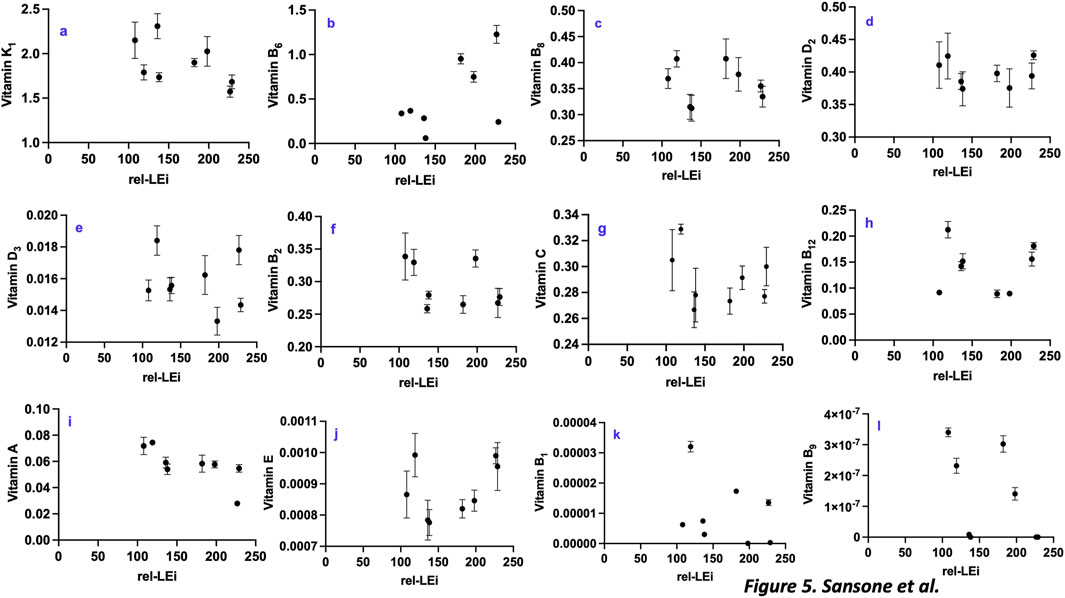

3.4 Vitamins

Vitamin K1, the most abundant vitamin, decreased with rel-LEi (p < 0.005; Figure 5a; Supplementary Table 1), and blue light intensity (Supplementary Table 2), with its concentration significantly higher in the low PAR cluster than in the high PAR cluster (p < 0.05). Vitamin K1 was negatively correlated with proteins and vitamin E (Supplementary Table 4), but was positively correlated with ferric iron (Fe3+), TPC, and FRAP (Supplementary Table 4). The red absence (0% vs. 5%) significantly decreased vitamin K1 concentration, only within the low PAR cluster (p < 0.01; Figure 5a).

Figure 5. Distribution of vitamins with respect to the rel-LEi (μmol photons m-2s-1): (a) Vitamin k1 (μg mg-1 DW); (b) Vitamin B6 (μg mg-1 DW); (c) Vitamin B8 (μg mg-1 DW); (d) Vitamin D2 μg mg-1 DW); (e) Vitamin D3 (μg mg-1 DW); (f) Vitamin B2 (μg mg-1 DW); (g) Vitamin C (μg mg-1 DW); (h) Vitamin B12 (μg mg-1 DW); (i) Vitamin A (μg mg-1 DW); (j) Vitamin E (μg mg-1 DW); (k) Vitamin B1 (μg mg-1 DW); (l) Vitamin B9 (μg mg-1 DW). Rel-LEi: relative light energy index (estimated according to Pistelli et al. (2023)).

Vitamin B6 followed an opposite trend (Figure 5b; Supplementary Table 1), with its concentration significantly lower within low PAR than high PAR intensity cluster (p < 0.001).

Vitamin B6 was negatively correlated with growth efficiency per unit light, the absorption capacity, as well as ABTS, and phytosterols/Lipids ratio (Supplementary Table 5). Additionally, its distribution was positively correlated with the dark respiration rate and Dt (Supplementary Table 5). The red absence (0% vs. 5%) significantly decreased vitamin B6 concentration within the two PAR clusters (p < 0.001; Figure 5b).

Vitamin B8 was strongly dependent on the red light intensity (Supplementary Table 6), and correlated with vitamin B1, B6, B9 and TPC (Supplementary Table 6). Conversely, higher concentrations of vitamin B8 were associated with lower photosynthetic O2 flux, growth rate and the growth efficiency per light unit as well as the ORAC results (Supplementary Table 6). Discriminating the two PAR clusters, vitamin B8 was negatively correlated with rel-LEi within the high PAR cluster (p < 0.001; Figure 5c).

Vitamin D2 did not exhibit a clear trend (Figure 5d), except within the low PAR cluster, in which vitamin D2 was negatively correlated with blue light (p < 0.01; Figure 5d). It is known to be synthesized from ergosterol and is generally not detected in diatoms (Del Mondo et al., 2021); thus, its bacterial origin cannot be excluded. Vitamin D2 was positively correlated with vitamins C, B12 and E as well as with cis-fucoxanthin (Supplementary Table 7). The red absence (0% vs. 5%) significantly increased vitamin D2 within the high PAR cluster (p < 0.05; Figure 5d).

Vitamin D3 was also almost stable among the different light conditions (Figure 5E). Vitamin D3 was negatively correlated with the photosynthetic Oxygen flux (Supplementary Table 8), and Fe2+ (Supplementary Table 8) while positively correlated with the vitamin B1 (Supplementary Table 8). It increased in absence of red (0% vs. 5%) within the high PAR cluster (p < 0.01; Figure 5e).

Vitamin B2 was inversely correlated with the phytosterols vs. lipids ratio (Supplementary Table 9), as well as with the following pigments: chl.a, chl.c, zea, ß-carotene (Supplementary Table 9). Conversely, vitamin B2 was positively correlated with vitamin A and C (Supplementary Table 9). Vitamin B2 displayed a negative relationship with blue light within the low PAR cluster (p < 0.05; Figure 5f).

Vitamin C did not show a trend with rel-LEi (Figure 5g), even though it showed an inverse relationship with rel-LEi within the low PAR cluster (Supplementary Table 10). It was positively related to vitamins A, B2, D2 and E (Supplementary Table 10). As the vitamins D3 and E, vitamin C was negatively correlated with the photosynthetic O2 flux (Supplementary Table 10), as well as to sterols content, ß-carotene, zeaxanthin, TFC and ORAC (Supplementary Table 10).

No significant trend with the rel-LEi was depicted for the vitamin B12 (Figure 5h), while it was negatively correlated with the red intensity (Supplementary Table 10). Within the high PAR cluster, this vitamin significantly increased with rel-LEi and thus blue light (p < 0.01). Also, the red absence (0%) induced its further increase (p < 0.01, compared to red 5%). Vitamin B12 was positively related to the vitamins E, D2, D3 (Supplementary Table 11), although negatively correlated with the photosynthetic O2 flux, Fe3+, Fe2+, TPC, TFC, FRAP and phytosterols content (Supplementary Table 11). Vitamin B12 was correlated with the concentration of the two minor pigments, cis-fucoxanthin and diadinochrome (Supplementary Table 11).

Vitamin A content decreased with blue or green intensity, and rel-LEi increase (Figure 5i; Supplementary Table 9). Its concentration was significantly higher in the low PAR cluster (p < 0.01). Vitamin A followed the same trend that the vitamins C, B2, B8 and K1, zinc and the absorption capacity of O. aurita (a*, Supplementary Table 12). Conversely, this vitamin was negatively correlated with growth rate, dark respiration, chl.a, and many carotenoids, as well as to ORAC (Supplementary Table 12).

Vitamin E did not follow a trend along the rel-LEi scale (Figure 5j). Intriguingly, vitamin E was positively related to blue light and rel-LEi within the high PAR cluster (p < 0.001; Figure 5j; Supplementary Table 13) although negatively correlated with these parameters within the low PAR cluster (p < 0.01; Figure 5j; Supplementary Table 13). Vitamin E was negatively correlated with the photosynthetic O2 flux, vitamin K1, sterols content, zinc and Fe3+ (Supplementary Table 13). Conversely, it was positively related to vitamins C and D2. Also, vitamin E was positively correlated with cis-fucoxanthin and diadinochrome and negatively to violaxanthin (Supplementary Table 13).

Vitamin B1 content was variable among the light conditions, and did not follow any trend with rel-LEi or PAR intensity (p > 0.05; Figure 5k). Vitamin B1 was positively correlated with vitamins B8, B6 and D3 and to the cell weight (Supplementary Table 14). Conversely, vitamin B1 was inversely correlated with the growth rate and photosynthetic O2 flux (Supplementary Table 14).

Vitamin B9 was the least abundant of the 12 analyzed vitamins (Figure 5l). Its distribution was negatively related to the rel-LEi (p < 0.001; Figure 5l), as well as to the blue or green light intensity although positively related to red light intensity (Supplementary Table 15). Vitamin B9 significantly decreased in absence of red (0%) compared to red presence (5%) within the two high and low PAR clusters (p < 0.001; Figure 5l). Also, its concentration was positively correlated with auxin content, vitamins A, K1 and B8, Fe3+, and TPC (Supplementary Table 15). Conversely, its distribution was negatively related to the growth rate, vitamin B12, ORAC and the phytosterols:lipids ratio (Supplementary Table 15).

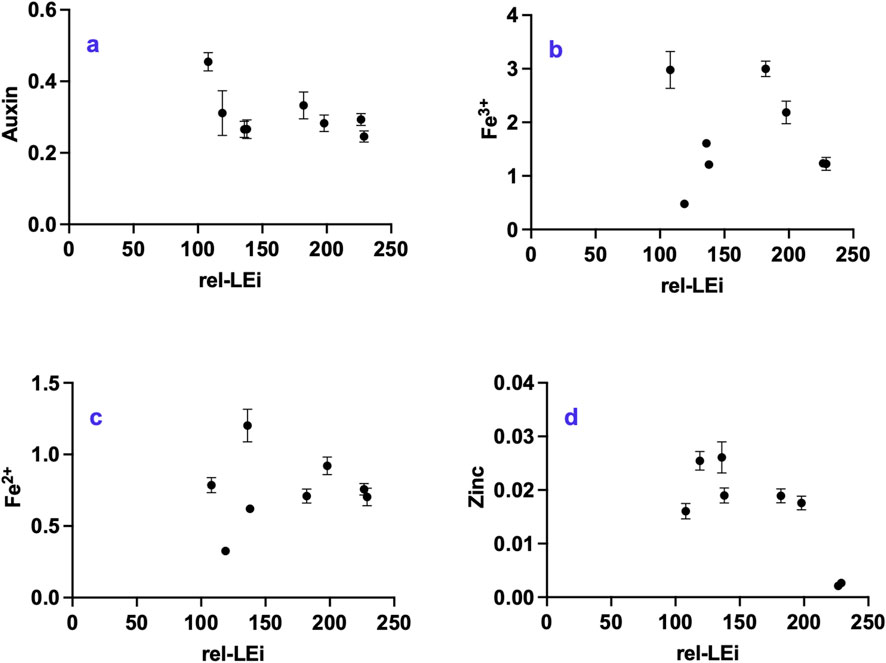

3.5 Auxin

Auxin concentration ranged between 0.24–0.45 pmol mg-1 DW showing a decreasing trend with increasing rel-LEi (Figure 6a). The relationship between auxin and rel-LEi became significant when the two PAR clusters were analyzed separately (low PAR: p < 0.01; high PAR: p < 0.05). Light color affected auxin concentration, with a significant relationship between auxin and red light intensity (r = 0.70, Supplementary Table 16), and a negative correlation with blue and green light intensities (r = −0.64, Supplementary Table 16). Auxin was positively correlated with vitamins B9, B6 and B8 (Supplementary Table 16), and negatively correlated with vitamin B12 (Supplementary Table 16). Auxin was also negatively related to growth rate and the phytosterols: lipids ratio (Supplementary Table 16). Conversely, it was positively correlated with lipid content as well as with Fe3+ and FRAP, which may indicate an effect of auxin accumulation on iron metabolism (Supplementary Table 16).

Figure 6. Distribution of (a) auxin (pmol mg-1 DW); (b) Fe3+ (nmol mg-1 DW); (c) Fe2+ (nmol mg-1 DW); (d) Zinc (nmol mg-1 DW) with respect to the rel-LEi (μmol photons m-2s-1). Rel-LEi: relative light energy index (estimated according to Pistelli et al. (2023)).

3.6 Iron and zinc

Fe3+, the dominant iron form in O. aurita biomass compared to the ferrous cation (Fe2+) (Figures 6b,c), displayed high variability with higher concentrations under maximum red contribution in both PAR clusters (Figure 6b). Within the high PAR cluster, Fe3+ was correlated with red contribution (p < 0.001; Figure 6b; Supplementary Table 3).

The absence of red light (0% vs. 5%) within the low PAR cluster induced a decrease in both Fe3+ and Fe2+, (p < 0.01; Figures 6b,c).

Zn2+ significantly decreased under high rel-LEi (Figure 6d, p < 0.01). The absence of red light (0% vs. 5%) within the low PAR cluster induced a decrease in Zn2+ (p < 0.05; Figure 6d).

3.7 Metabolomics

The main classes of metabolites discriminated by NMR included amino acids (the most abundant were lysine, arginine, ornithine, alanine, glutamate, aspartate, asparagine, and threonine), carboxylic acids (succinate, fumarate), sugars (glucose and sucrose), lipids (short-chain fatty acids), nucleoside derivatives and cofactors (uridine monophosphate/ diphosphate-glucose, ATP/ADP, NAD+), choline moieties (choline, phosphocholine and glycerophosphocholine) and osmolytes (trigonelline, scyllo-inositol).

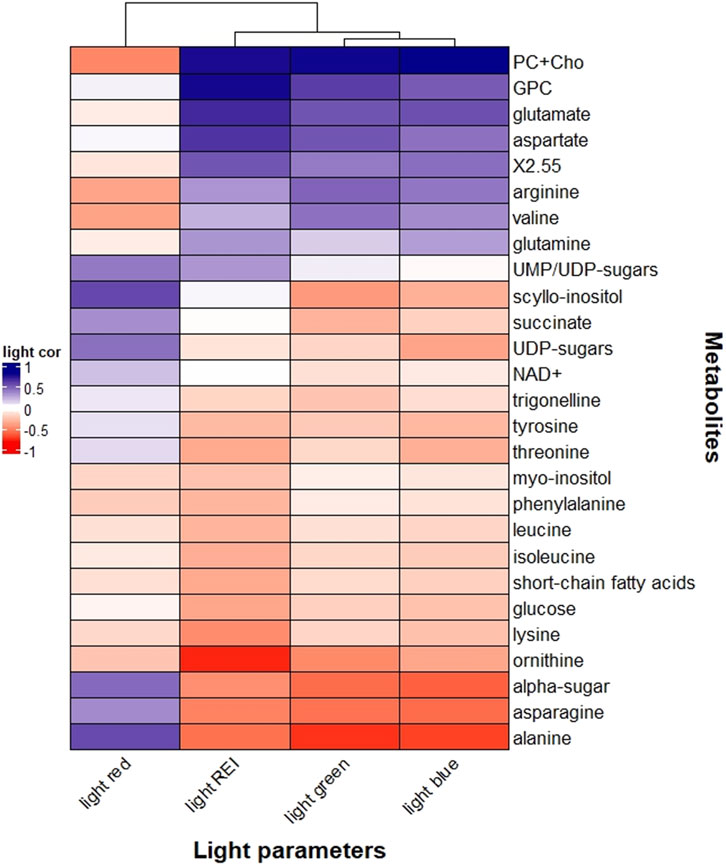

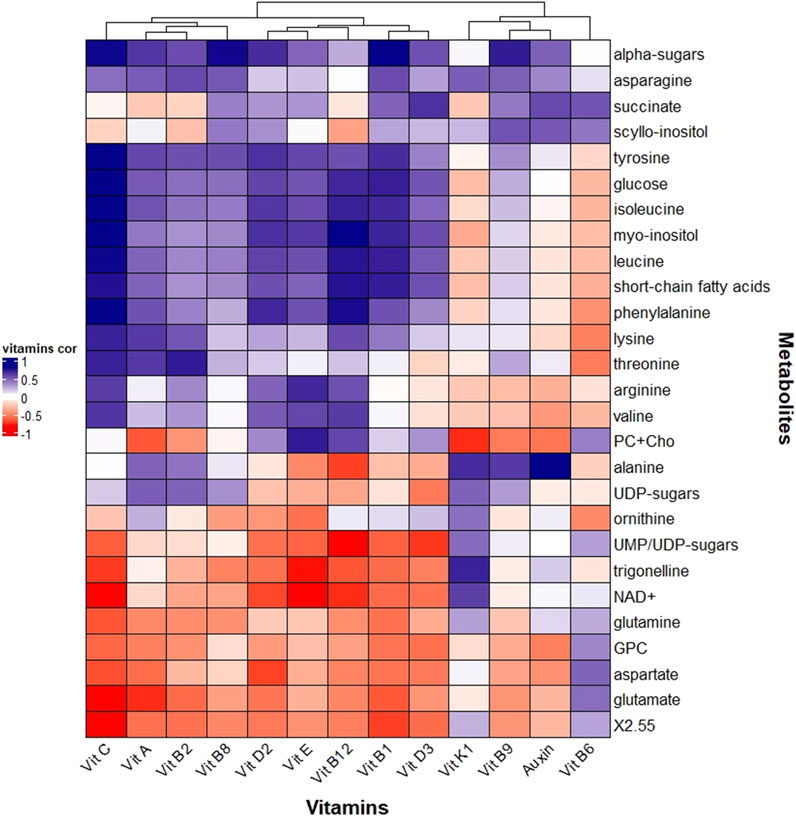

Figures 7, 8 reported correlations between the main metabolites revealed by NMR and light parameters (Figure 7), vitamins or auxin (Figure 8). Correlations with metals and antioxidant capacities were provided in supplementary information (Supplementary Figure 3; Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 7. Heatmap correlation between Odontella aurita metabolomic data and light properties (red light, blue light, green light, and rel-LEi). Pearson correlation was calculated based on Euclidean distance for the metrics and the mean method for clustering criterion. Rel-LEi: relative light energy index (estimated according to Pistelli et al., 2023).

Figure 8. Heatmap correlation between Odontella aurita metabolomic data and vitamins and auxin. Pearson correlation was calculated based on the Euclidean distance for the metrics and the mean method for clustering criterion.

Metabolites correlated with rel-LEi were generally related to blue light (Figure 7). Blue light positively affected choline moieties, including choline, phosphocholine (PC), and glycerophosphocholine and the amino acids glutamine, glutamate, aspartate, arginine, and valine (Figure 7). Choline is involved in lipid metabolism as precursor of phospholipids (Zhang et al., 2021), and therefore plays a role in response to abiotic stress.

The amino acids glutamine, glutamate, aspartate, arginine and valine are involved in protein synthesis and/or nitrogen assimilation or storage.

Aspartate, present in chloroplasts, participates in various metabolic pathways (de la Torre et al., 2014), and is regulated by light (Mills et al., 1980). Also, blue light may affect nitrogen uptake and assimilation thus influencing glutamate and glutamine concentrations (Döhler et al., 1994).

Arginine is known as a nitrogen storage form in photosynthetic organisms (Llácer et al., 2008). Conversely, ornithine–a precursor of arginine (Winter et al., 2015; Majumbar et al., 2016) - decreased with PAR intensity (also with blue or red light, Figure 7). These two amino acids are involved in the urea cycle that diatoms use as pathway for anaplerotic carbon fixation (Allen et al., 2011), to process the nitrogen rich amino acids produced under blue/high light. In contrast to other amino acids, such as glutamine and aspartate (Figure 7), alanine and asparagine were negatively correlated with blue light and rel-LEi while positively to red light (Figure 7). Asparagine, synthesized from glutamine and aspartate, represents a key amino acid in nitrogen metabolism, and it is involved in photorespiration in plants (Ta et al., 1985).

Alanine is closely linked to pyruvate, a product of photosynthesis and a substrate for the respiratory tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Parthasarathy et al., 2019). It contributes to vitamin B5, which is incorporated into coenzyme A (Parthasarathy et al., 2019), a molecule that plays a crucial role in the fatty acid and carbohydrate metabolism, through the TCA cycle (Zhang and Fernie, 2018). These results suggest that blue light may enhance nitrogen assimilation, whereas red light may be involved in the processing of nitrogen-rich amino acids and in (photo)respiration.

This hypothesis was also confirmed by the correlation between red light and succinate (Figure 7). The latter, synthesized in the mitochondria, is involved in the TCA cycle and used by succinate dehydrogenase in respiration and the production of signaling ROS in mitochondria (Jardim-Messeder et al., 2015).

Red light was also positively correlated with α-sugars, UDP-sugars and the carbohydrate scyllo-inositol (Figure 7). α-sugars serve mainly as building blocks of polysaccharides i.e., energy reserve of the cells. Conversely, the role of UDP-glucose in plants is not well defined with possible functions as a precursor of polysaccharides, in biomass accumulation, growth, and programmed cell death, or, as in animals, as an extracellular signaling molecule, activating defense mechanism (van Rensburg and Van den Ende, 2018). The UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase enzyme involved in the synthesis of UDP-glucose was detected in diatoms (Zhang et al., 2023), while its activity increased with light (Meng et al., 2009).

Myo-inositol, a growth and metabolic enhancer (Qian et al., 2021), was detected in O. aurita without any significant relationship with red light. The conversion of myo-inositol to scyllo-inositol (Gross and Meyer, 2003) may be red light-regulated, with the latter correlated with red light (Figure 7). NAD+ (vitamin B3), a cofactor for the enzyme involved in the scyllo-inositol transformation (Yamaoka et al., 2011), was negatively correlated with red light, supporting the accumulation of scyllo-inositol under red light.

Many of the NMR-detected metabolites reported significant correlation with auxin or vitamins corroborating their essential roles e.g., as co-factors, in many biochemical pathways (Figure 8). Our results might shed light on the role of some vitamins in diatoms, such as O. aurita.

Vitamin B9, involved in one-carbon metabolism, correlated with scyllo-inositol, α-sugars, as well as with succinate, alanine and asparagine (Figure 8). The correlation of these metabolites with red light (Figure 7; Supplementary Table 15) suggested an important role of this color on their intracellular fate, with potential involvement of vitamin B9. The red-related photorespiration involving PS I as an electron sink to prevent oxidative damages was supported by the asparagine result (Shi et al., 2022), as well as by the behaviours of vitamin K1, NAD+ and one of its precursors, the trigonelline (Figure 8).

By contrast, vitamin B6 correlated with “high light” and to the photoprotective Dt, was related to aspartate and glutamate (Figure 8), which are light-dependent (Mitchell and Stocking, 1975) and among the most present amino acids in chloroplasts (Kirk and Leech, 1972). Vitamin B6 is known to efficiently quench ROS (Havaux et al., 2009), and to be involved in amino acid metabolism as well as chlorophyll synthesis (Parra et al., 2018). In plants and green algae, the two acidic residues, aspartate and glutamate, are constitutive of the PsBS proteins (Ptushenko et al., 2023) with a pH-sensing role, crucial for photoprotection (Liguori et al., 2019). However, their absence in the photoprotection-involved Lhcx proteins in diatoms (Bailleul et al., 2010) suggested another role - probably still related to light- in these organisms.

Vitamin D3, a sterol derivate, was highly related to succinate (Figure 8), hypothetically indicating their common derivation from acetyl-coA (Warren et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022), even though they belong to different pathways.

Vitamin E, correlated with vitamins D2 and C, was related to choline and phosphocholine, as well as arginine and valine (Figure 8). They were all correlated with blue light and/or rel-LEi (Figure 7). Choline and phosphocholine have an important role for membrane structure (Kent, 1995), while vitamin E, a lipid-soluble antioxidant has a protective role against lipid peroxidation in membranes (Muñoz and Munné-Bosch, 2019). Blue light that boosts growth might therefore induce membrane component synthesis, and in turn its protection. Correlation with arginine and valine enters also in this frame. Arginine is known to be an important amino acid present in membranes (Hristova and Wimley, 2011) while, valine as branch-chained amino acid and building block for proteins, has an important role in membranes (Binder et al., 2007; Frank et al., 2021).

Vitamin A, related to vitamins B2 and C, was correlated with lysine and threonine (Figure 8). Vitamins A and B2 have a plastidial origin (Gerdes et al., 2012), while vitamin C is synthetized in the mitochondria with many functions in chloroplasts (Tóth, 2023). Also, threonine is found in chloroplasts (Nassoury and Morse, 2005; Muthuramalingam et al., 2018), with a role of epigenetic regulation of gene expression (Tóth, 2023), similarly to threonine (Nassoury and Morse, 2005) and lysine (Contreras-de la Rosa et al., 2022).

Auxin also displayed significant relationships with NMR-retrieved metabolites (Figure 8).

Interestingly, auxin presented the same positive correlation pattern as vitamin B9, i.e., with α-sugars, scyllo-inositol, asparagine, succinate and alanine (Figure 8).

Conversely, correlation was negative with choline, phosphocholine (PC) and glycerophosphocholine, aspartate, glutamate, arginine and valine (Figure 8), all of them being positively correlated with blue light (Supplementary Table 3).

NMR-retrieved metabolites did also report correlation with metals (Supplementary Figure 3). For instance, the relationships between ornithine, lysine and asparagine with zinc were depicted. It is well known that lysine chelates zinc, and the latter composes a great number of proteins (Broadley et al., 2007), as for instance the metallothioneins (Pande et al., 1985). Zn was correlated with UDP-sugars (Supplementary Figure 3), and this could be explained by the fact that this metal is a co-factor for enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism (Brand and Heinickel, 1991). Also, iron concentration was correlated with glutamate/glutamine (Supplementary Figure 3), which are involved in iron homeostasis in plants (Kailasam et al., 2020).

The correlations between NMR-retrieved metabolites and antioxidant results (Supplementary Figure 4) confirmed the diversity of the three assays, with ABTS significantly different from FRAP or ORAC. For instance, the antioxidant glutamine, glutamate and aspartate–metabolites involved in the NRF2 signaling pathway (Egbujor et al., 2024) - were strongly related to ORAC and FRAP result (Supplementary Figure 4). Also, NAD+ and its precursor trigonelline were correlated with FRAP and ORAC (Supplementary Figure 4).

Alanine with a protective role in plants (Parthasarathy et al., 2019) was correlated with FRAP and ABTS. Conversely, ornithine–another amino acid with a protective role in plants (Kalamaki et al., 2009) was mainly correlated with ABTS (Supplementary Figure 4).

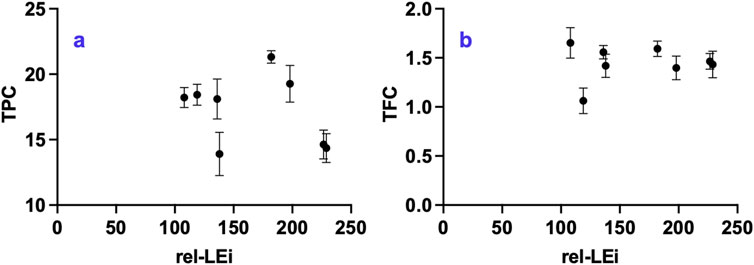

3.8 Total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC)

TPC and TFC did not show overall trend with rel-LEi (Figures 9a,b). Within the high PAR cluster, both decreased significantly with increasing rel-LEi (more markedly for TPC, p < 0.01; Figure 9a). TPC correlated positively with red intensity (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table 3) and inversely with blue intensity (p < 0.05; Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 9. Distribution of (a) Total Phenolic Compounds (TPC, μg mg-1 DW); (b) Total Flavonoid Compounds (TFC; mg-1 DW) vs. the rel-LEi (μmol photons m-2s-1). Rel-LEi: relative light energy index (estimated according to Pistelli et al. (2023)).

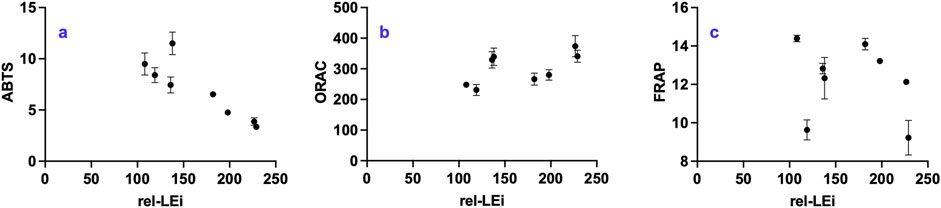

3.9 Antioxidant property

The antioxidant assays ABTS, ORAC, and FRAP target different oxidative mechanisms, which explains the divergent outcomes (Figures 10a–c). ABTS decreased significantly with increasing rel-LEi (p < 0.01; Figure 10a), resulting lower values in the high-PAR than in the low-PAR cluster. Within the low-PAR cluster, the absence versus presence of red light (0% vs. 5%) markedly increased ABTS. ORAC showed no overall trend with rel-LEi (Figure 10b). In both PAR clusters, ORAC was lower at higher red contribution, and vice-versa (Figure 10b); thus, red contribution significantly affected ORAC, whereas PAR played no major role.

Figure 10. Distribution of (a) ABTS (μgTE mg-1 DW); (b) FRAP (ngTE mg-1 DW); (c) ORAC (ngTE mg-1 DW) vs. the rel-LEi (μmol photons m-2s-1). Rel-LEi: relative light energy index (estimated according to Pistelli et al. (2023)). ABTS: 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid); ORAC: Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity, FRAP: Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power.

FRAP values were highly variable and showed no overall trend across the rel-LEi scale (Figure 10C). Within the high-PAR cluster, FRAP decreased as rel-LEi increased with a sharp drop in the absence of red (0% vs. 5%, p < 0.01; Figure 10c). To summarize, the ORAC, ABTS, and FRAP results were differently affected by the light environment due to the modulation of algal metabolism. Although ABTS values decreased with increasing light intensity, ORAC seemed to be more sensitive to the red light contribution.

4 Discussion

Red and blue light are sensed by different photoreceptors and represent crucial signals that strongly modulate metabolic and physiological responses in diatoms (Coesel et al., 2009; Falciatore et al., 2022; Zhang H. et al., 2022; Duchene et al., 2025). Although this study does not permit to address the role of photoreceptors and intracellular signalling on metabolites’variations, it advances understanding of the role of blue and red light in modulating key molecules and metabolic pathways in the diatom O. aurita.

In this context, the network of significant relationships - direct or indirect, causal or casual - between light spectral variables and metabolic cues (Supplementary Figures 5a-c) provides a foundation for further exploration of the potential role of photoreceptors. This study will enable the selection of key targets among compounds or related metabolic pathways of interest, thereby facilitating the investigation of their potential links with cryptochromes and phytochromes. Our results pave the way for subsequent studies addressing this topic by applying molecular tools to the diatom model Phaeodactylum tricornutum, for instance, as well as to the emerging model O. aurita, whose genome sequencing is currently in progress.

Blue light sensing primarily affects photosynthesis and its conversion into biochemical energy, thereby affecting growth rate, biomass formation, and nitrogen assimilation. It also promotes membrane biosynthesis and the protection of its components, being correlated with arginine and valine. Arginine is an important amino acid present in membranes (Hristova and Wimley, 2011), while valine, a branched-chain amino acid also plays an important role in membranes (Binder et al., 2007; Frank et al., 2021). The enhancement of photosynthesis under blue light, and the consequent rise in energy flux, requires enhanced photoprotection and antioxidant activities to mitigate the reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated during the efficient blue-light harvesting. This is reflected in the accumulation of carotenoids, lipid-soluble antioxidants that sustain photosynthetic efficiency and reduce ROS formation (Foyer and Shigeoka, 2011; Smerilli et al., 2017; 2019). The increase in carotenoids, xanthophyll-cycle pigments (Dd–Dt), and zeaxanthin (together with the decrease in violaxanthin) further confirms the need for photoprotection and antioxidant defense under blue-light, supported by correlations between ORAC and both rel-LEi and blue light. Within the saturating PAR cluster, the correlation between ORAC and Dt (R2 = 0.91), a well-known antioxidant (Pistelli et al., 2021b), as well as DES (De-Expoxidation state, (Dt/(Dt + Dd)), R2 = 0.99), fuco (R2 = 0.63), and cis-fuco (R2 = 0.95) highlight the impact of spectral composition on the oxidative system and the antioxidant network. The increase in PSII associated antioxidant vitamin E confirms this feature (Krieger-Liszkay et al., 2006; Kumar et al., 2021; Niu et al., 2022), together with its inverse relationship with vitamin K1, reinforces this observation. In plants, Vitamin K1 acts as cofactor for PSI-mediated electron transport (Kegel and Crane, 1962). Therefore, its decrease suggests a light-driven modulation of PSI abundance or the PSI/PSII ratio, a known protective mechanism (Tarento et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2021; Mladěnka et al., 2022), also reported in diatoms under high light (Chukhutsina et al., 2013). The decrease of vitamin A with increasing blue light indicates possible spectral-modulated competition between carotenoid and vitamin A biosynthesis, as both derive from β-carotene. Vitamin B6 content did not correlate directly with blue or red light, but with PAR intensity and rel-LEi. Vitamin B6 is present in the chloroplast with potential photoprotective and/or antioxidant role (Havaux et al., 2009), and involved in photorespiration in plants (Liu et al., 2022). It can be used as cofactor for enzymatic reactions, such as decarboxylation (Liu et al., 2022), the key step of respiration (Bender et al., 2022). Indeed, in O. aurita, vitamin B6 was correlated negatively with the absorption capacity, while positively with dark respiration and diatoxanthin, suggesting a role in photoprotection and respiration. Since sampling was performed in the dark, the observed Dt reflects a pool not epoxidized back to Dd overnight, consistent with reports of multiple Dt pools with distinct NPQ capacities in diatoms (Grouneva et al., 2008; Lepetit et al., 2013).

In natural systems, increases in red light are typically accompanied by increases in blue light, while the absence of red light is a clear marker of low irradiance. Our results indicate that red light sensing plays a significant role in carbon storage and nitrogen metabolism. Red intensity strongly affects vitamins B9 and B8, as well as auxin synthesis, consistent with earlier observation in land plants (Kondo et al., 1969). Auxin is known to regulate growth (Mano and Nemoto, 2012; del Mondo et al., 2021; Carrillo-Carrasco et al., 2023), and its role on sexual reproduction in O. aurita has been reported (Sison-Mangus et al., 2022). Although light and auxin play antagonistic roles in regulating critical developmental processes (Xu et al., 2018), auxin displayed an inverse relationship with growth rate but covaried with cell weight and lipid content, supporting its role in maintaining growth rather than promoting cell division. This study points out the crucial role of auxin in diatom metabolism and growth, but cannot discern between diatoms’ synthesis and the result of complex algae–bacteria interactions (Amin et al., 2015), which also involve certain B vitamins (Bertrand et al., 2012; Costas-Selas et al., 2024; Sayer et al., 2024). This is hypothetically the case with vitamin B9, which diatoms actively acquire from bacteria or surrounding environment and known to be highly variable in microalgae (Woortman et al., 2020). The light modulation observed for auxin and vitamins B9, B12, and D2 reveals that light spectral composition may also influence the requirement and uptake of these molecules from the environment, and, hypothetically, bacterial co-metabolism. This represents another important outcome of the study, even though no specific hypothesis or functional mechanism can yet be inferred. Further studies are therefore required to investigate bacterial co-metabolism during O. aurita cultivation, as the microbiome is a key factor for the growth and development of O. aurita (Sison-Mangus et al., 2022) and other diatoms (Sato et al., 2020). The next step will involve the development of an axenic O. aurita culture using an ultrafiltration process to examine the bacterial role, which is preparatory for the targeted domestication of the bacterial community within the culture (Blifernez-Klassen et al., 2021).

The correlation between auxin and four vitamins suggests coordinated regulation of metabolic pathways, as observed between vitamin B9 and auxin in land plants (Li et al., 2023). Red-intensity-related vitamin B9 synthesis has also been observed in seedlings and plants (Hytönen et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2021; Kolton et al., 2022). Folates play a role in one carbon metabolism (Gerdes et al., 2012), a crucial biochemical process in plant that is involved in activation of alternative pathways (García-Valencia et al., 2025) and in responses to external cues (Hanson et al., 2000; Fitzpatrick, 2024). Folates are involved in the functioning of the photosynthetic apparatus (Goroleva et al., 2017), and in light-dependent processes (Jabrin et al., 2003; Okazaki and Yamashita, 2019), such as photorespiration (Hanson et al., 2000), which is consistent with their chloroplast-mediated biosynthesis (Gorelova et al., 2019). Red-dependent photorespiration, involving vitamin B9, might also recruit PSI as an electron sink to prevent oxidative damage, as suggested by its correlation with vitamin K1 (Kegel and Crane, 1962). This is also supported by the red correlation of asparagine (Shi et al., 2022), and by the correlations involving NAD+ and one of its precursors, trigonelline. Indeed, NAD+ is involved in the assembly of the NADH dehydrogenase-like (NDH) complex, which plays a crucial role in Photosystem I (Su et al., 2022).

The inverse correlation between vitamins B12 and B9, as well as with red intensity, might indicate a red-light-regulated conversion of vitamin B12 into vitamin B9, with cobalamin acting as a cofactor of the cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase involved in folate one-carbon metabolism (Mendoza et al., 2023).

Beyond this role, cobalamin serves as a cofactor for various cobalamin-dependent enzymes, such as certain isomerases (Banerjee and Ragsdale, 2003; Takahashi-Iñiguez et al., 2012). This might explain the highly significant relationship between vitamin B12 and the concentrations of two minor carotenoids, cis-fucoxanthin and diadinochrome. Cis-fucoxanthin is an isomer of fucoxanthin, and diadinochrome is related to diadinoxanthin, while fucoxanthin and diadinoxanthin are biosynthetically related (Bai et al., 2022). This hypothesis suggests that vitamin B12 may be used to rearrange certain carotenoids. Moreover, cobalamin is also known to be a component of some blue photoreceptors (Padmanabhan et al., 2022), further linking it to light responses.

Beyond red intensity, our study addresses the question of the absence versus presence of red wavelengths in shaping diatom metabolism. Eight of the twelve estimated vitamins were affected by the presence or absence of red light, confirming the crucial role of red sensing in regulating biochemical metabolism and homeostasis. The molecules most affected by the absence of red light—compared to 5% red—are vitamins B9, B6, and B1. Their content was fostered by the presence of red under both PAR intensities, supporting a role of red sensing in their accumulation. The red modulation of vitamin B9 has been discussed previously, although the lack of red correlation of vitamins B1 and B6 indicates an “On/Off” response. As stated before, the chloroplastic vitamin B6 is involved in photoprotection and antioxidative activity as well as in respiration (Havaux et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2022). Red light sensing–compared to no red - might therefore serve as a signal to increase this vitamin, which in turn may enhance respiration. The latter was correlated with rel-LEi and is significantly lower (p < 0.05) in absence of red compared to 5% presence under high PAR. Vitamin B1 is involved in citric acid cycle or glycolysis (Raschke et al., 2007), and its biosynthesis occurs partly in the chloroplast (Raschke et al., 2007; Fitzpatrick and Chapman, 2020). Its modulation might alter carbon partitioning (Abbriano et al., 2018), as corroborated by the significant decrease in lipid content in the absence of red light under saturating conditions and the increase in carbohydrate and protein pools in the absence of red light under limiting conditions. Other vitamins increase in the absence of red light, although they reveal a dependence on PAR intensity. For example, vitamin B2 increased under low PAR without red, while vitamins B12, A, and D2 increased under high PAR without red. Conversely, vitamin D3 decreased in the same condition.

For biotechnological purposes, particularly in microalgal-based food supplement and feed applications, the bioactive compound content (e.g., vitamins, amino acids, carotenoids) of a bioresource is crucial for eliciting a healthy physiological response in humans or farmed animals. Considering that light-driven modulation of these compounds can enhance the bioactive properties, the outcomes of this study hold significant relevance. Increasing the added value of cultivated biomass is essential for the further development of microalgal-based feeds and food supplements derived from alternative species to Spirulina. In this context, O. aurita represents a promising candidate, as it is already employed as a food complement and as feed, and appears to be active in specific metabolic pathways (Sansone et al., 2025).

5 Conclusion

The results of this study highlight distinct roles—antagonistic or complementary—of PAR, red or blue light intensity, and the presence or absence of a red signal. Red light emerged as a key regulator of biochemical adjustments, particularly in modulating carbon partitioning, and influencing the use of carbon storage. Although vitamins and auxin were identified as central players in maintaining homeostasis and fine-tuning metabolism under changing light conditions in O. aurita, further investigation is needed to evaluate their potential for metabolic engineering strategies aimed at improving productivity (Hanson et al., 2000). The large database generated here provides a valuable resource for advanced data analysis using artificial intelligence, neural networks (Esteves et al., 2025), mathematical modeling, and systems biology. This would enable the development of new hypotheses, the prioritization of different light-related factors, and, ultimately, the prediction of outcomes and optimization of bioengineering systems (Zimmermann and Hurrell, 2002).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

CS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Validation. MR: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. DP: Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis. LP: Methodology, Writing – original draft. MM: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation. FC: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Software. AT: Methodology, Writing – original draft. AI: Methodology, Writing – original draft. FM: Methodology, Writing – original draft. AS: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. SB: Writing – review and editing. FD: Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis. MF: Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis. CB: Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Validation.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Raphaelle Leroux for her help during the experiments with the microalgal cell counts and some laboratory analyses. David Cleal is acknowledged for his help in some samples analysis. The authors thank Mariella Ferrante (SZN) for the critical reading and comments on a previous version of the manuscript. CB warmly thanks FC (FC, “O’ Ingé”), who will retire in 2026, for his long-lasting friendship and collaboration on the topic of light and microalgae, and for the development and set-up of the light system used in our studies. The authors acknowledge the four reviewers for their comments on the previous versions of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphbi.2025.1715336/full#supplementary-material

References

Abbriano, R., Vardar, N., Yee, D., and Hildebrand, M. (2018). Manipulation of a glycolytic regulator alters growth and carbon partitioning in the marine diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. Algal Res. 32, 250–258. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2018.03.018

Agarwal, A., Levitan, O., Cruz de Carvalho, H., and Falkowski, P. G. (2023). Light-dependent signal transduction in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 120 (11), e2216286120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2216286120

Allen, A., Dupont, C., Oborník, M., Horák, A., Nunes-Nesi, A., McCrow, J. P., et al. (2011). Evolution and metabolic significance of the urea cycle in photosynthetic diatoms. Nature 473, 203–207. doi:10.1038/nature10074

Amin, S., Hmelo, L., van Tol, H., Durham, B. P., Carlson, L. T., Heal, K. R., et al. (2015). Interaction and signalling between a cosmopolitan phytoplankton and associated bacteria. Nature 522, 98–101. doi:10.1038/nature14488

Amine, H., Benomar, Y., Haimeur, A., Messaouri, H., Meskini, N., and Taouis, M. (2016). Odontella aurita-enriched diet prevents high fat diet-induced liver insulin resistance. J. Endocrinol. 228 (1), 1–12. doi:10.1530/JOE-15-0316

An, S. M. ,, Cho, K., Kim, E. S., Ki, H., Choi, G., and Kang, N. S. (2023). Description and characterization of the Odontella aurita OAOSH22, a marine diatom rich in eicosapentaenoic acid and fucoxanthin, isolated from osan harbor, Korea. Mar. Drugs 21 (11), 563. doi:10.3390/md21110563

An, S. M., Cho, K., Kang, N. S., Kim, E. S., Ki, K., Choi, G., et al. (2024). Development of a cost-effective medium suitable for the growth and fucoxanthin production of the microalgae Odontella aurita using Jeju lava seawater and agricultural fertilizers. Biomass Bioenergy 88, 107310. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2024.107310

Bai, Y., Cao, T., Dautermann, O., Buschbeck, P., Cantrell, M. B., Chen, Y., et al. (2022). Green diatom mutants reveal an intricate biosynthetic pathway of fucoxanthin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119 (38), e2203708119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2203708119

Bailleul, B., Rogato, A., de, M., Coesel, S., Cardol, P., Bowler, C., et al. (2010). An atypical member of the light-harvesting complex stress-related protein family modulates diatom responses to light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 18214–18219. doi:10.1073/pnas.1007703107

Banerjee, R., and Ragsdale, S. W. (2003). The many faces of vitamin B12: catalysis by cobalamin-dependent enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 209–247. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161828

Bender, M. L., Zhu, X. G., Falkowski, P., Ma, F., and Griffin, K. (2022). On the rate of phytoplankton respiration in the light. Plant Physiol. 190 (1), 267–279. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiac254

Bertrand, E. M., Allen, A. E., Dupont, C. L., Norden-Krichmar, T. M., Bai, J., Valas, R. E., et al. (2012). Influence of cobalamin scarcity on diatom molecular physiology and identification of a cobalamin acquisition protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109 (26), E1762–E1771. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201731109

Bialevich, V., Zachleder, V., and Bišová, K. (2022). The effect of variable light source and light intensity on the growth of three algal species. Cells 11, 1293. doi:10.3390/cells11081293

Binder, S., Knill, T., and Schuster, J. (2007). Branched-chain amino acid metabolism in higher plants. Physiol. Plant. 129, 68–78. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.2006.00800.x

Blifernez-Klassen, O., Klassen, V., Wibberg, D., Cebeci, E., Henke, C., Rückert, C., et al. (2021). Phytoplankton consortia as a blueprint for mutually beneficial eukaryote-bacteria ecosystems based on the biocoenosis of botryococcus consortia. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1726. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-81082-1

Brand, I. A., and Heinickel, A. (1991). Key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism as targets of the 11.5-kDa Zn(2+)-binding protein (parathymosin). J. Biol. Chem. 266 (31), 20984–20989. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)54808-0

Broadley, M. R., White, P. J., Hammond, J. P., Zelko, I., and Lux, A. (2007). Zinc in plants. New Phytol. 173, 677–702. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.01996.x

Broddrick, J. T., Ware, M. A., Jallet, D., Palsson, B. O., and Peers, G. (2022). Integration of physiologically relevant photosynthetic energy flows into whole genome models of light-driven metabolism. Plant J. 112, 603–621. doi:10.1111/tpj.15965

Brunet, C., Chandrasekaran, R., Barra, L., Giovagnetti, V., Corato, F., and Ruban, A. V. (2014). Spectral radiation dependent photoprotective mechanism in diatom pseudo-nitzschia multistriata. PLoS ONE 9 (1), e87015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087015

Carrillo-Carrasco, V. P., Hernandez-Garcia, J., Mutte, S. K., and Weijers, D. (2023). The birth of a giant: evolutionary insights into the origin of auxin responses in plants. EMBO J. 42 (6), e113018. doi:10.15252/embj.2022113018

Chang, J., Xie, C., Wang, P., Gu, Z., Han, Y., and Yang, R. (2021). Red light enhances folate accumulation in wheat seedlings. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 22 (11), 906–916. doi:10.1631/jzus.B2100266

Chukhutsina, V. U., Büchel, C., and van Amerongen, H. (2013). Variations in the first steps of photosynthesis for the diatom Cyclotella meneghiniana grown under different light conditions. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1827 (1), 10–18. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.09.015

Coesel, S., Mangogna, M., Ishikawa, T., Heijde, M., Rogato, A., Finazzi, G., et al. (2009). Diatom PtCPF1 is a new cryptochrome/photolyase family member with DNA repair and transcription regulation activity. EMBO Rep. 10, 655–661. doi:10.1038/embor.2009.59

Contreras-de la Rosa, P. A., Aragón-Rodríguez, C., Ceja-López, J. A., García-Arteaga, K. F., and De-la-Peña, C. (2022). Lysine crotonylation: a challenging new player in the epigenetic regulation of plants. J. Proteomics 255, 104488. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2022.104488

Costas-Selas, C., Martínez-García, S., Pinhassi, J., Fernández, E., and Teira, E. (2024). Unveiling interactions mediated by B vitamins between diatoms and their associated bacteria from cocultures. J. Phycol. 60 (6), 1456–1470. doi:10.1111/jpy.13515

Cuong, D. M., Yang, S. H., Kim, J. S., Moon, J. Y., Choi, J., Go, G. M., et al. (2024). Evaluation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity and identification of bioactive compound from the marine diatom, Odontella aurita extract. Appl. Biol. Chem. 67, 46. doi:10.1186/s13765-024-00898-3

de la Torre, F., Cañas, R. A., Pascual, M. B., Avila, C., and Cánovas, F. M. (2014). Plastidic aspartate aminotransferases and the biosynthesis of essential amino acids in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 65 (19), 5527–5534. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru240

de Mooij, T., de Vries, G., Latsos, C., Wijffels, R. H., and Janssen, M. (2016). Impact of light color on photobioreactor productivity. Algal Res. 15, 32–42. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2016.01.015

Del Mondo, A., Smerilli, A., Sané, E., Sansone, C., and Brunet, C. (2021). Challenging microalgal vitamins for human health. Microb. Cell Factories 19 (201), 201. doi:10.1186/s12934-020-01459-1

Döhler, G., and Kugel-Anders, A. (1994). Assimilation of 15N-ammonium by Lithodesmium variabile takano during irradiation with UV-B (300–320 nm) and complemental monochromatic light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 24 (1), 55–60. doi:10.1016/1011-1344(94)07010-5

Duchêne, C., Bouly, J. P., Pierella Karlusich, J. J., Vernay, E., Sellés, J., Bailleul, B., et al. (2025). Diatom phytochromes integrate the underwater light spectrum to sense depth. Nature 637 (8046), 691–697. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-08301-3

Egbujor, M. C., Olaniyan, O. T., Emeruwa, C. N., Saha, S., Saso, L., and Tucci, P. (2024). An insight into role of amino acids as antioxidants via NRF2 activation. Amino Acids 56, 23. doi:10.1007/s00726-024-03384-8

Esteves, A. F., Pardilhó, S., Gonçalves, A. L., Vilar, V. J. P., and Pires, J. C. M. (2025). Unravelling the impact of light spectra on microalgal growth and biochemical composition using principal component analysis and artificial neural network models. Algal Res. 85, 103820. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2024.103820

Falciatore, A., Bailleul, B., Boulouis, A., Bouly, J.-P., Bujaldon, S., Cheminant-Navarro, S., et al. (2022). Light-driven processes: key players of the functional biodiversity in microalgae. Comptes Rendus Biol. 345 (2), 15–38. doi:10.5802/crbiol.80

Fan, W. M. T. (1996). Metabolite profiling by one- and two-dimensional NMR analysis of complex mixtures. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson Spectrosc. 28, 161–219. doi:10.1016/0079-6565(95)01017-3

Fitzpatrick, T. B. (2024). B vitamins: an update on their importance for plant homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 75 (1), 67–93. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-060223-025336

Fitzpatrick, T. B., and Chapman, L. M. (2020). The importance of thiamine (vitamin B1) in plant health: from crop yield to biofortification. J. Biol. Chem. 295 (34), 12002–12013. doi:10.1074/jbc.REV120.010918

Flynn, K. J., Atkinson, A., Beardall, J., Berges, J. A., Boersma, M., Brunet, C., et al. (2025). Projecting future responses of ocean ecosystems requires more realistic plankton simulation models. Nat. Ecol. & Evol., 1–9. doi:10.1038/s41559-025-02788-3

Foyer, C. H., and Shigeoka, S. (2011). Understanding oxidative stress and antioxidant functions to enhance photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 155 (1), 93–100. doi:10.1104/pp.110.166181

Frank, M. W., Whaley, S. G., and Rock, C. O. (2021). Branched-chain amino acid metabolism controls membrane phospholipid structure in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 297 (5), 101255. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101255

García-Valencia, L. E., Garza-Aguilar, S. M., Ramos-Parra, P. A., and Díaz de la Garza, R. I. (2025). Planting resilience: one-carbon metabolism and stress responses. Plant Physiology Biochem. 224, 109966. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.109966

Gerdes, S., Lerma-Ortiz, C., Frelin, O., Seaver, S. M., Henry, C. S., de Crécy-Lagard, V., et al. (2012). Plant B vitamin pathways and their compartmentation: a guide for the perplexed. J. Exp. Bot. 63 (15), 5379–5395. doi:10.1093/jxb/ers208

Giovagnetti, V., Cataldo, M. L., Conversano, F., and Brunet, C. (2010). Functional relation between growth, photosynthetic rate and regulation in the coastal picoeukaryote phaeomonas sp. RCC 503 (pinguiophyceae, stramenopiles). J. Plankton Res. 32 (11), 1501–1511. doi:10.1093/plankt/fbq074

Giovagnetti, V., Cataldo, M. L., Conversano, F., and Brunet, C. (2012). Growth and photophysiological response curves of the two picoplanktonic minutocellus sp. RCC967 and RCC703 (bacillariophyceae). Eur. J. Phycol. 47 (4), 408–420. doi:10.1080/09670262.2012.733030

Gorelova, V., Ambach, L., Rébeillé, F., Stove, C., and Van Der Straeten, D. (2017). Folates in plants: research advances and progress in crop biofortification. Front. Chem. 5, 1–20. doi:10.3389/fchem.2017.00021

Gorelova, V., Bastien, O., De Clerck, O., Lespinats, S., Rébeillé, F., and Van Der Straeten, D. (2019). Evolution of folate biosynthesis and metabolism across algae and land plant lineages. Sci. Rep. 9, 5731. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42146-5

Gross, W., and Meyer, A. (2003). Distribution of myo-inositol dehydrogenase in algae. Eur. J. Phycol. 38 (3), 191–194. doi:10.1080/1364253031000121705

Grouneva, I., Jakob, T., Wilhelm, C., and Goss, R. (2008). A new multicomponent NPQ mechanism in the diatom Cyclotella meneghiniana. Plant Cell Physiol. 49 (8), 1217–1225. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcn097

Haimeur, A., Ulmann, L., Mimouni, V., Guéno, F., Pineau-Vincent, F., Meskini, N., et al. (2012). The role of Odontella aurita, a marine diatom rich in EPA, as a dietary supplement in dyslipidemia, platelet function and oxidative stress in high-fat fed rats. Lipids Health Dis. 11, 147. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-11-147

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T., and Ryan, P. D. (2001). PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron 4, 1–9.