- School of Physical Education (Main Campus), Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China

Background: Weightlifting (WT) and Plyometric training (PT) may lead to comparable enhancements in strength, jump, and sprint performance. However, these two training modalities appear to differ significantly in their primary focus and underlying mechanisms.

Objective: Examining the differences between WT and PT in improving lower extremity sports performance.

Methods: A systematic search was conducted from five databases, including Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, Elsevier, and Springer. Two authors developed specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to screen relevant literature based on the study objectives. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale. We conducted both direct comparisons and network meta-analysis on the eligible studies. The assumptions of similarity, homogeneity, and consistency within the Bayesian network were also confirmed.

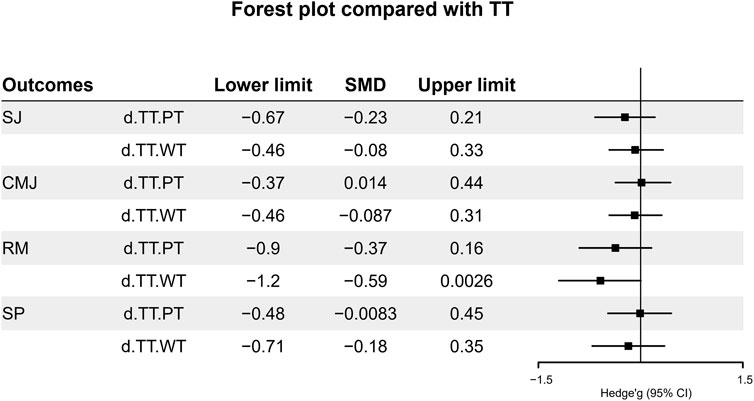

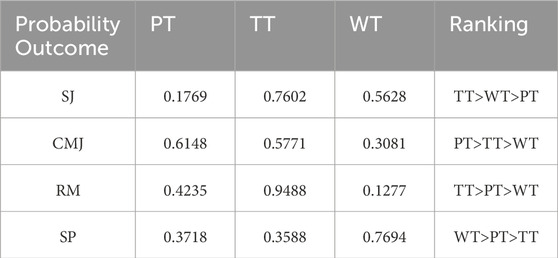

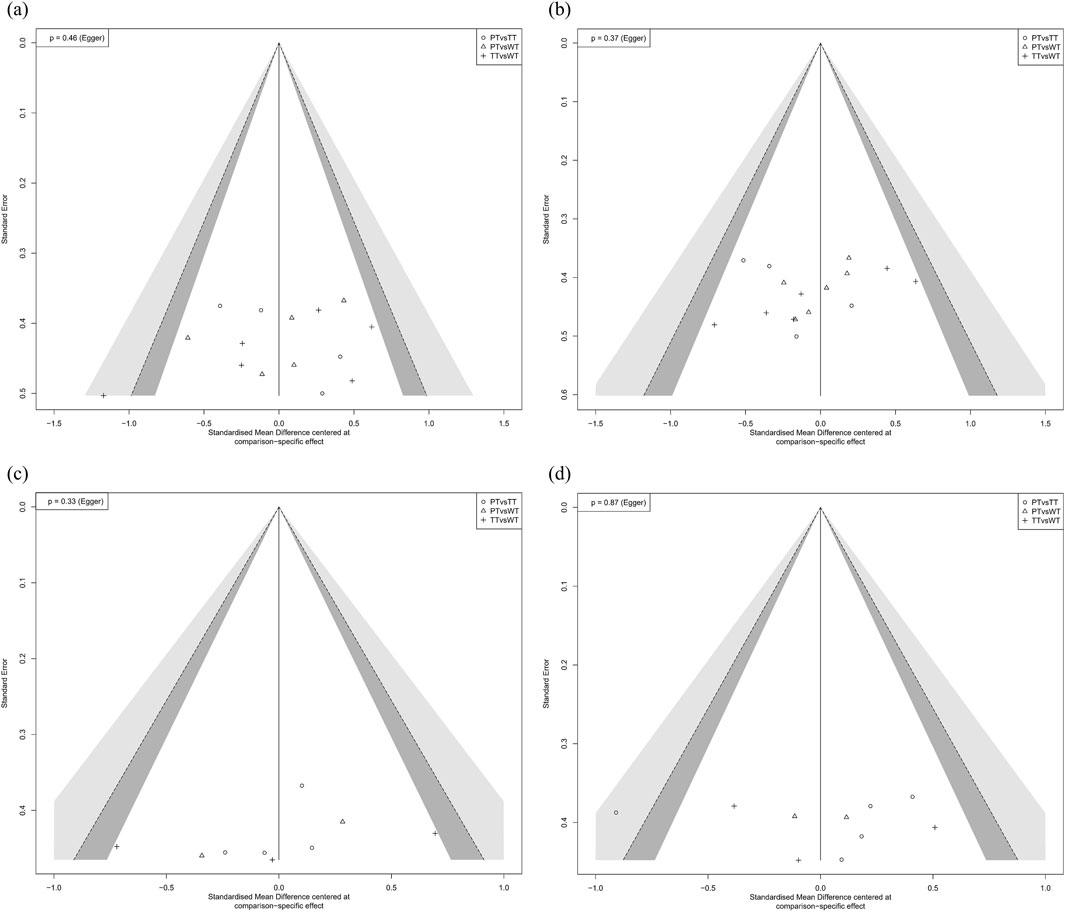

Results: A total of 17 studies met the inclusion criteria, involving 394 participants. All studies were found to have a low or moderate risk of bias, with average score of 4.29. The Bayesian network meta-analysis showed no significant differences. According to the SUCRA rankings, TT was most likely to excel in squat jumps (SJ) (SUCRA = 0.76) and maximum strength (SUCRA = 0.95), WT for sprint (SUCRA = 0.77), and PT for countermovement jumps (SUCRA = 0.76). The tests of similarity, homogeneity and consistency of the network meta-analysis were also generally valid. The funnel plot and Egger regression tests indicated no publication bias.

Conclusion: In summary, the WT programs are more effective at improving sprint performance by increasing power, while the PT programs improve jumping performance by improving the stretch-shortening cycle.

Systematic Review Registration: identifier CRD 420250540130.

1 Introduction

Lower extremity strength and power are foundational to athletic success across diverse sports, from explosive track and field events to dynamic team sports like basketball and soccer (Muehlbauer et al., 2015; Suchomel et al., 2016). These physical traits directly determine an athlete’s capacity to sprint, jump, and change direction rapidly—actions that often differentiate elite competitors (Young et al., 1995; Burnie et al., 2018; Young, 2006; Vosburg et al., 2022; Negra et al., 2020). Yet, despite widespread recognition of its importance, a critical question persists: What is the most effective training methodology to optimize lower-body power and translate it into measurable athletic outcomes?

Two dominant paradigms have emerged in strength and power training: weightlifting training (WT) and plyometric training (PT). Weightlifting exercises and their derivatives primarily emphasize the development of maximal strength and power through movements such as the snatch and clean and jerk, which involve lifting heavy loads with explosive actions (Morris et al., 2022; Young, 2006). This type of training enhances neuromuscular coordination, muscle hypertrophy, and the ability to generate force rapidly, making it particularly effective for athletes who require high levels of absolute strength and power (Simenz et al., 2005; Ebben, 2009). In contrast, PT focuses on improving the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) efficiency, which is crucial for activities that involve rapid transitions from eccentric to concentric muscle actions, such as jumping and sprinting (Markovic et al., 2007; Watkins, 2009; Booth and Orr, 2016; Komi, 2000). Plyometric exercises, like depth jumps and bounding, aim to increase muscle-tendon stiffness and enhance the storage and release of elastic energy, thereby improving reactive strength and explosive performance (Markovic and Mikulic, 2010). While both modalities enhance power-related metrics, their mechanistic divergence—WT’s emphasis on absolute force versus PT’s SSC efficiency—suggests context-dependent efficacy (Morris et al., 2022; Berton et al., 2018). Determining the performance objectives under which WT or PT should be prioritized, and whether their benefits extend uniformly across key indicators such as vertical jump, sprint speed, and injury resilience, is essential for evidence-based training prescription.

Existing comparative analyses on the efficacy of different training modalities are largely inconclusive, hindering clear guidance for practitioners. For instance, earlier reviews such as those by (Arabatzi et al., 2010; Hackett et al., 2016) concluded that WT and PT did not demonstrate significant differences in improving jumping performance. Early meta-analyses, such as that by (Berton et al., 2018), while reporting advantages of WT over traditional resistance training (TT) for countermovement jump (CMJ) height, also found no significant differences between WT and PT. However, these conclusions were constrained by narrow outcome measures (e.g., CMJ alone) and limited sample sizes (n = 7 studies), failing to account for sport-specific demands or multi-dimensional performance metrics. Subsequent work by (Morris et al., 2022) expanded the evidence base, corroborating WT’s advantages over TT while reaffirming WT-PT equivalence—yet critical gaps persist. The robustness of these findings requires rigorous evaluation against a broader spectrum of athletic tasks, and methodological limitations in prior syntheses may obscure nuanced differences between WT and PT. Notably, conventional pairwise meta-analyses struggle to resolve these questions due to fragmented direct comparisons and heterogeneous study designs.

This uncertainty underscores the need for an analytical framework capable of synthesizing direct and indirect evidence across diverse interventions. Network meta - analysis (NMA) presents a powerful solution to overcome the limitations of traditional pairwise comparisons. NMA combines both direct and indirect evidence from multiple interventions within a unified analytical framework, enabling a more comprehensive comparison of different training methods. This approach allows for a more accurate estimation of the relative effectiveness of WT and PT, even when direct head - to - head comparisons are scarce. By synthesizing data from a broader range of studies, NMA can offer valuable insights into the comparative advantages of these training modalities for enhancing lower - body power and athletic performance. The primary aim of this study is to use network meta - analysis to systematically compare the effectiveness of weightlifting training and plyometric training in terms of lower - body power and athletic performance. Specifically, this study intends to: (1) Assess the relative impact of WT and PT on key measures of lower extremity power, such as vertical jump height, and sprint performance. (2) Investigate the differences in the emphases of three training modalities in enhancing sports performance. (3) Provide evidence-based recommendations for integrating WT and PT into sports training programs. By resolving longstanding controversies in strength programming, this analysis seeks to empower coaches, athletes, and sports scientists with data-driven insights for optimizing lower-body power development.

2 Methods

This systematic review and network meta-analysis has been designed and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020 statement), the extended PRISMA statement for Network Meta-Analyses, and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Page et al., 2021; Shuster, 2011). The completed PRISMA 2020 checklist is available in Supplementary Material S1. The protocol was previously registered in the international database of systematic reviews PROSPERO (ID: CRD420250540130, in April 2024).

2.1 Search strategy

A thorough literature search was carried out across multiple databases, namely Web of Science, PubMed (Pubmed Central), Scopus, Elsevier, and Springer. The search imposed no constraint on the publication date; however, it was confined to articles published in English. To pinpoint relevant studies, Boolean search logic was utilized, with specific search terms crafted around weightlifting training, plyometric training, traditional resistance training, and performance outcomes. The supplementary material holds a detailed account of the search strategy. Subsequently, two researchers independently went through the titles and abstracts of the identified studies to assess their relevance. Full - text versions of studies that appeared eligible were obtained and evaluated against the pre - set inclusion criteria. In cases where the two reviewers disagreed, discussions were held to iron out the differences.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria for the literature were established based on the PICOS (Participants, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, and Study Design) guidelines. Studies involving healthy male or female participants were selected without restrictions on publication dates.

The participants included in this systematic review were individuals who maintained good health throughout the experimental process, with no restrictions on ethnicity, nationality, or sex. Age restrictions are limited to early adulthood (18–30 years old). Studies were excluded if they involved participants with chronic diseases or if they included animal subjects, which were identified and removed during the title and abstract screening phase.

Studies must have compared at least two of the following training modalities: weightlifting training (WT), traditional resistance training (TT), or plyometric training (PT). The intervention period was required to be a minimum of 6 weeks, with at least two training session per week, totaling at least twelve sessions.

The control group performed resistance training or the same regular interventions as the intervention group. For the network meta-analysis, we defined comparison groups based on the interventions studied. In this network, TT was designated as the reference treatment to allow for the quantification of relative treatment effects between PT, WT, and TT. Studies included in the network either compared one of these interventions against TT, or compared PT directly against WT.

Studies were required to report on at least one performance measure, including lower-limb maximum strength (1RM squat), jumping performance (squat jump, countermovement jump), or sprint performance (short-distance sprint).

Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in English were included. For studies based on the same sample, only one article was included to avoid duplication.

Exclusion criteria included duplicate publications, insufficient data availability despite attempts to contact authors, and studies with significant methodological flaws or poor testing protocols. Studies failing to meet the minimum quality standard of 3 points on the PEDro scale.

2.3 Data extraction

Adhering to the PRISMA guidelines for literature selection and data extraction, the data collection form is based on the extraction form modified from the “Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions” (Higgins et al., 2019). Extracted data included: (1) Basic study information (first author, year of publication). (2) Participant demographics (gender, age, sample size, subject identity). (3) Intervention details (training methods, frequency, load, duration, number of sessions). (4) Outcome measures (1RM squat, squat jump, countermovement jump, sprint). During the process of data extraction, data from all intervention groups is obtained. In instances where direct acquisition of data is not feasible, methodologies such as GetData Graph Digitizer and Cochrane data conversion tools are employed to ensure uniform integration of the data. To maintain rigor, literature lacking crucial data that cannot be converted or that does not meet the established criteria is excluded directly. For the same intervention measures within the same literature, a combined treatment is applied.

2.4 Methodological quality and publication bias

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale, which evaluates external validity (Item 1) and internal validity (Items 2–9), as well as the adequacy of statistical information (Items 10–11). Each criterion met scores 1 point, with a maximum possible score of 10 (excluding Item 1). Studies scoring 6–10 were considered high quality, 4-5 moderate quality, and ≤3 low quality. Two authors independently evaluated the methodological quality of each study, with discrepancies resolved through discussion and consultation.

Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s regression test and funnel plot asymmetry adjustments (Egger et al., 1997).

2.5 Statistical analysis

The Bayesian network meta-analysis model was chosen for its ability to rank interventions based on posterior probabilities. This approach overcomes the limitations of frequentist methods, which estimate parameters by iteratively maximizing the likelihood function. Such methods can lead to instability and biased results. In contrast, the Bayesian model is more flexible and is currently the preferred method in evidence-based research.

The analysis was conducted using R (version 4.3.3 with the gemtc package) and Stata (MP 18). Given the different measurement methods for the outcome indicators, a random effects model was chosen to minimize heterogeneity and determine the overall effect of the training interventions on the outcomes, including 1RM, SJ, CMJ, and SP.

To objectively and accurately reflect the relative effects of the three intervention methods and to exclude the influence of the conventional training control group on effect sizes, direct comparisons were made between the three interventions. The pre- and post-training changes in the experimental and control groups were used to calculate the standardized mean difference (SMD) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) for pooling effect sizes. Heterogeneity was assessed I2 statistic (low <25%, moderate 25%–50%, high >50%). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3 Results

A total of 3,187 references were initially searched from five databases, and an additional eight articles were obtained from reference sources. Duplicates were removed using the “Find Duplicate References” feature in EndNote, resulting in 853 unique papers. After screening titles, abstracts, and full texts, 86 articles were selected for further review. In the end, 17 pieces of literature were selected after a thorough full-text review (Arabatzi et al., 2010; Arabatzi and Kellis, 2012; Berton et al., 2022; Boraczyński et al., 2023; Ciacci and Bartolomei, 2018; Hawkins et al., 2009; Helland et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2004; Ita and Guntoro, 2018; MacDonald et al., 2012; Oranchuk et al., 2019; Ribeiro et al., 2020; Teo et al., 2016; Tricoli et al., 2005; Vissing et al., 2008; Whitehead et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 1993). The flow diagram of the literature is presented in Figure 1.

3.1 Characteristics of study

Ultimately, 17 studies were included in the analysis, comprising 15 two-arm trials and 2 three-arm trials. Among the 17 studies, there were a total of 394 participants distributed across 12 plyometric training groups (n = 134), 13 traditional resistance training groups (n = 142), and 11 Olympic weightlifting training groups (n = 118). The age range of participants was 18–30 years. The fundamental characteristics of the literature are presented in Table 1.

3.2 Methodological quality and risk of bias

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using the PEDro scale for physical therapy. Overall, the average PEDro score of 4.29 indicated that the included studies were of moderate quality as shown in Table 1.

Of the various methods used to assess publication bias, funnel plots are most frequently employed due to their straightforward nature; however, analyzing publication bias with funnel plots necessitates subjective interpretation to detect bias and cannot objectively describe symmetry within the graphical representation. Egger’s tests and adjustments for asymmetry in funnel plots were utilized to assess publication bias. Funnel plot results suggested a generally symmetrical distribution, while Egger’s regression test results indicated no significant publication bias with p > 0.05, thus indicating the absence of publication bias. The findings from both the funnel plot and Egger’s regression tests confirmed that publication bias was largely absent from the studies (Egger et al., 1997). See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Funnel plot for various performance outcomes. Panels (a−d) present the risk of bias results for squat jump, countermovement jump, maximal strength, and sprint, respectively.

3.3 Meta-analysis

The outcome measures selected for the meta-analysis related to lower extremity strength performance were maximum strength, jumping ability, and sprinting ability. Lower limb maximum strength is a key indicator of athletes’ performance in both jumping and sprinting movements. The maximum strength measures included the highest weight achieved in one repetition of squat, half-squat, or leg press exercises. The short-distance sprints were defined by the time taken to complete sprints ranging from 5 to 30 m. Three types of standing vertical jump were assessed: squat jump, countermovement jump.

3.3.1 Bayesian network meta-analysis

A network model was established for the network meta-analysis, which was then compiled using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method. To ensure model convergence, we employed 20,000 pre-iterations and 50,000 actual iterations, a decision guided by established recommendations for MCMC analyses and preliminary checks demonstrating the stability of parameter estimates.

Model convergence was assessed using a combination of diagnostic tools. Trace plots and density plots (detailed in Supplementary Material S5) showed stable fluctuations with good overlap after 20,000 iterations, and the bandwidth in density plots approached and remained stable near zero, indicating effective convergence and saturation. Additionally, the potential scale reduction factor (PSRF), which measures the extent to which the posterior variance has shrunk relative to the prior variance, was used to further confirm convergence.

Model fit was assessed using the posterior mean residual (Dbar) and Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) to evaluate the model’s adequacy to the data.

3.3.2 Testing for consistency

To examine the consistency assumption, a node-splitting method was employed to test one of the foundational assumptions of the network meta-analysis, producing outputs comparing effect sizes using only direct evidence, only indirect evidence, and all evidence combined. Discrepancies between direct and indirect evidence were assessed by examining the p-value column; a p-value of <0.05 for one or more comparisons indicates substantial inconsistencies within the network. A p-value of <0.05 for one or more comparisons indicates significant inconsistencies within the network. Analysis of the output results revealed that all tests for inconsistencies were not statistically significant, indicating a high level of consistency, thereby confirming the validity of the consistency tests for the network meta-analysis. For detailed results, see Supplementary Material S3 for the inconsistency analysis outcomes.

3.3.3 Intervention comparisons

The Bayesian network model facilitated the merging of effect sizes from all studies, allowing for comparisons between PT and WT, using TT as the reference group. The results showed that among all outcome measures, only the maximum strength indicator displayed significance for traditional resistance training, with statistical relevance. Refer to Figure 3.

3.3.4 SUCRA ranking

To identify the optimal intervention effects across different methodologies, SUCRA ranking probability analyses were conducted for each outcome measure, resulting in the creation of cumulative ranking charts. The outcomes of SJ, CMJ, and RM constituted positive effects, while the SP outcome was considered a negative effect, measured in seconds (s). The final outcomes revealed that TT yielded better improvements in squat jumps and maximum strength; PT showed more effectiveness for countermovement jump; and WT improves short-distance sprinting best. Specific rankings can be referenced in Table 2, which displays the SUCRA rankings.

3.4 Heterogeneity analysis

The outcomes of the heterogeneity analysis indicated that the I2 values for direct pairwise comparisons of the interventions across all outcome indicators were generally below 75%, thus reflecting low heterogeneity. Moreover, the network comparisons of the interventions also had an I2 value generally below 75% and was less than that of the direct comparisons. Please refer to Supplementary Material S4. for details on the heterogeneity analysis.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to investigate whether there are differences in the improvements of strength, jumping, and sprint between weightlifting training (WT) and plyometric training (PT). The network meta-analysis results indicated that WT has a greater advantage in improving sprint performance, traditional resistance training (TT) offers significant benefits in increasing maximal strength and squat jumps (SJ), and PT has a more pronounced effect on countermovement jump (CMJ) performance. However, these results were not statistically significant.

4.1 Plyometric training for lower extremity strength

PT has been widely recognized for its ability to enhance lower extremity strength, power, and sprint performance through its unique physiological mechanisms. The core principle of PT lies in the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC), which involves a rapid eccentric (lengthening) phase followed by an immediate concentric (shortening) contraction (Watkins, 2009; Markovic and Mikulic, 2010; Turner and Jeffreys, 2010; Tomalka et al., 2020). This mechanism allows muscles and tendons to store elastic energy during the eccentric phase, which is then released during the concentric phase, resulting in a more powerful and efficient movement. The SSC is particularly effective in improving sprint performance due to its ability to enhance the rate of force development (RFD) and reduce ground contact time, both of which are critical for explosive movements such as sprinting and jumping.

Physiological adaptations induced by PT include increased tendon stiffness and muscle fiber hypertrophy, particularly in type IIa fibers, which are responsible for fast-twitch muscle contractions (Komi, 2000; Mero and Komi, 1986). Studies have shown that PT can lead to a 24.1% increase in tendon stiffness, which enhances the efficiency of force transmission from muscles to bones, thereby improving power output during explosive movements (Fouré et al., 2010). Additionally, PT has been shown to increase the cross-sectional area (CSA) of key lower extremity muscles, such as the quadriceps and hamstrings, by up to 10%, further contributing to improved strength and power (Vissing et al., 2008). These adaptations are particularly beneficial for sprint performance, as they allow athletes to generate greater force in a shorter amount of time, which is essential for rapid acceleration and high-speed running.

The short ground contact time (<250 ms) characteristic of PT exercises is another key factor that makes it particularly effective for improving sprint performance (Malisoux et al., 2006; Watkins, 2009; Flanagan and Comyns, 2008). During sprinting, the ability to quickly transition from the eccentric to the concentric phase of muscle contraction is crucial for maintaining high running speeds. PT training enhances this ability by improving neuromuscular coordination and increasing the stiffness of the lower extremity muscles and tendons, which reduces the time required to generate force during each stride (Bouguezzi et al., 2020). This is why PT is often more effective than other training modalities for improving sprint-related performance.

In terms of practical applications, PT should be tailored to the athlete’s experience level and specific performance goals. For beginners, it is recommended to start with low-intensity exercises involving 40–80 ground contacts per session, gradually progressing to higher intensities as the athlete becomes more experienced (Jensen and Ebben, 2005). Elite athletes, on the other hand, may benefit from high-intensity PT sessions involving 200–400 ground contacts, as these can further enhance power output and sprint performance. Controversially, many studies have found that high-intensity plyometric training is highly susceptible to injury and fatigue (Tofas et al., 2008; Drinkwater et al., 2009; Chatzinikolaou et al., 2010). For instance, one study found that high-volume plyometric training (212 ground contacts) already severely impairs a muscle’s ability to generate force and slow evoked contraction velocity, even if the athlete doesn’t feel fatigued (Drinkwater et al., 2009). It is crucial to balance training intensity with adequate recovery, as excessive PT can lead to neuromuscular fatigue and muscle damage, particularly in type II fibers, which are highly susceptible to overtraining (Macaluso et al., 2012). In addition, an anonymous survey study showed that many practitioners routinely use significantly lower amounts of sessions than previously recommended in the literature (p < 0.05) (Watkins et al., 2021). Thus, to align with the practical need for safe, effective PT programming (and address the nuance of volume prescription across athlete populations), training design must prioritize individualized volume adjustment (rather than a one-size-fits-all range) and integrated recovery strategies.

In summary, the physiological mechanisms underlying PT, particularly the SSC, make it highly effective for improving sprint performance by enhancing tendon stiffness, muscle fiber hypertrophy, and neuromuscular coordination. To optimize its benefits, PT should be implemented with careful consideration of the athlete’s experience level and recovery needs, ensuring that training intensity is appropriately matched to the desired performance outcomes.

4.2 Weightlifting training for lower extremity strength

The weightlifting training methods, including the clean and jerk, snatch, and deadlift, facilitate the achievement of coordinated triple extension in the primary lower extremity joints (hip, knee, and ankle) during exercise. Weightlifting dates back to ancient China, Egypt, and Greece, and it wasn’t until the 1950s that it found its application in foundational training for non-weightlifting athletes involved in team sports and athletics (Comfort et al., 2023; Todd, 2008; Shurley and Todd, 2012). Since that time, weightlifting-style training methods have been extensively applied in strength training. Fry’s study revealed that weightlifters exhibit a greater proportion of type IIA fibers and a comparatively higher relative content of myosin heavy chain IIA sub than normal adults. Furthermore, weightlifting performance shows strong correlation with the percentage of type IIA fibers (r = 0.94) and the area percentage of type IIA fibers (r = 0.83) (Fry et al., 2003). Numerous cross-sectional studies have provided evidence that high-intensity training in weightlifters results in hypertrophy of type IIA fibers (Fry et al., 2003; Tesch et al., 1984). Longitudinal HIRE studies on non-weightlifters also indicate the potential conversion from IIX to IIA fiber types (Fry, 2004). Olympic weightlifting essentially relies on movements like the clean, jerk, snatch, and deadlift, stressing the quick movement and release of the, thus representing a dynamic and rapid form of training that allows athletes to generate substantial force and power in a brief timeframe; this dynamic and rapid training method effectively improves an athlete’s explosive strength. Similarly, jumping involves quickly moving the body vertically and ‘releasing’ it into the air. This attribute of weightlifting training overlaps with the biomechanics of sprinting and jumping. Extensive longitudinal studies and systematic evaluations have reported the efficacy of weightlifting training in enhancing athletic strength performance. In weightlifting training, the muscle rate of force development and power output are maximized, with numerous researchers discovering that weightlifting significantly enhances power during jumps (Arabatzi and Kellis, 2012; Hawkins et al., 2009; Ostrowski et al., 1997). Garhammer’s study additionally identified similarities between the force-velocity loading profiles of weightlifting training and the movement patterns involved in jumping (Garhammer, 1993). Collectively, these findings suggest that weightlifting training can more effectively improve rapid muscle strength and power output to conventional training methods. Indeed, while weight training greatly enhances lower extremity performance, it also places significant demands on the flexibility of the hip, ankle, and upper limb joints due to its specific movement patterns. People with inadequate joint flexibility and insufficient technical proficiency may fail to experience training benefits, thereby raising their injury risk during exercise. Elite level weightlifters engage in high-intensity resistance exercises (HIRE, ≥80% of 1RM) twice or more each day, accumulating 6-7 sessions a week (Garhammer, 1993; Thrush, 1995). In elite weightlifters, partitioning the predefined training volume into two sessions on the same day can markedly enhance muscle strength, hypertrophy, and maximal neural activation of the trained muscle groups (Häkkinen and Kallinen, 1994; Hartman et al., 2007). Nevertheless, as most exercises executed by weightlifters revolve around competitive lifting and similar multi-joint activities, the same primary muscle groups experience extensive contractions during each training session. Existing evidence further suggests that repeated HIRE targeting the same muscle groups can result in sustained suppression of critical synthetic metabolic mediators, prolonged inflammatory response, and decreased muscle performance (Fry et al., 1994b; Fry et al., 1994a; Fry et al., 2006; Crewther and Christian, 2010; Crewther et al., 2011). Compared to conventional resistance training, weightlifting may yield lower strength development; nevertheless, it demonstrates higher outputs in speed-strength performances in young athletes (Channell and Barfield, 2008). Moreover, the rate of force development (RFD) during weightlifting is considerably greater than that observed during squats (Chimera et al., 2004; Gruber et al., 2007; Young and Bilby, 1993). While there is no direct evidence suggesting adverse effects of weightlifting training on children or adolescents, there remains significant debate regarding its use among younger populations (Storey and Smith, 2012). Consequently, there is still a lack of well-defined physiological guidelines and age-appropriate weightlifting training recommendations.

4.3 Practical variations in lower extremity strength interventions among different training methods

Indeed, numerous studies suggest that traditional heavy resistance training primarily centers on maximizing muscle strength and muscle hypertrophy, which in turn enhances lower extremity performance, thus accounting for the substantial increases in maximal strength. On the other hand, weightlifting and plyometric training methods tend to reduce muscle hypertrophy due to their distinct movement patterns while focusing on enhancing lower extremity explosiveness (Cormie et al., 2011a; Cormie et al., 2011b; Folland and Williams, 2007; Komi, 1984). In exploring the impact of plyometric training, weightlifting training, and TT on performance improvement, the specificity of training methods must be addressed. Concerning training specificity, considerable evidence demonstrates that employing training methods analogous to the targeted movement patterns can result in greater transfer of training effects and subsequently yield better outcomes. Stone indicated that the SSC associated with plyometric training and the triple extension in weightlifting are evidently better aligned with the biomechanics of vertical jump performance (Stone et al., 2022). Additionally, many studies have confirmed the effectiveness of both plyometric training and weightlifting training in increasing power output (Cormie et al., 2011a; Cormie et al., 2011b; Suchomel et al., 2015). In addition, studies have revealed that weightlifting exercises and ultra-length exercises share similarities with the dynamics of jumping (including maximum strength and power, the timing to reach maximum strength and power, and relative strength and power) (Canavan et al., 1996; Haff et al., 2005; Haff et al., 2015). Although TT executes actions that resemble vertical jumps with similar hip, knee, and ankle extension movements, the application of higher loads (above 80% of 1RM) inevitably result in some loss of movement velocity (Cormie et al., 2007; Hedrick and Wada, 2008). Even under lower load conditions (45% 1RM), which are closer to practical movement speeds, TT displays a prominent deceleration phase. This deceleration phase is related to slower concentric velocities, diminished concentric forces, and decreased levels of muscle recruitment; these factors together result in a reduction in maximum power output. Another perspective argues that specificity in strength training is not a requirement; rather, an increase in muscle contractile strength will naturally enhance an athlete’s jumping capability. Supporters of this theory believe that the effectiveness of plyometric training and weightlifting in improving vertical jump performance is due to their ability to enhance muscle contractile capacity (Toumi et al., 2004; Adams et al., 1992). To summarize, while weightlifting and plyometric training may show somewhat less effectiveness in enhancing maximum muscle strength relative to TT, they appear to be more beneficial in improving quick strength. It is advised to integrate weightlifting methods and plyometric training with TT in training regimens.

5 Conclusion

This meta-analysis examined the differences in the effects of two similar training methods on improving lower extremity performance. Our findings affirm the superiority of resistance training in improving maximal strength. However, we observed that weightlifting and its derivatives were more effective in improving sprint performance, while plyometric training was more effective in enhancing countermovement jump. This is because the biggest feature of the WT approach is power enhancement, whereas PT focuses more on stretch-shortening cycle improvement. Therefore, this study suggests that although weightlifting training WT and PT share many similarities, they have different emphases.

Finally, practitioners should integrate these strength training modalities to mutually enhance the training effect, e.g., PT training after resistance training or PT exercises before WT to enhance neuromuscular performance, and these combinations are already widely used.

Author contributions

SW: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software. JZ: Writing – review – editing, Data curation, Formal analysis. TX: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Resources, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to ZZU for providing the necessary resources and support that significantly enhanced our research efforts. Their contributions have been instrumental in achieving the outcomes of this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2025.1637520/full#supplementary-material

References

Adams K., O'shea J. P., O'shea K. L., Climstein M. (1992). The effect of six weeks of squat, plyometric and squat-plyometric training on power production. J. Strength Cond. Res. 6, 36–41. doi:10.1519/00124278-199202000-00006

Arabatzi F., Kellis E. (2012). Olympic weightlifting training causes different knee muscle-coactivation adaptations compared with traditional weight training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 26, 2192–2201. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823b087a

Arabatzi F., Kellis E., Saèz-Saez De Villarreal E. (2010). Vertical jump biomechanics after plyometric, weight lifting, and combined (weight lifting + plyometric) training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 24, 2440–2448. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e274ab

Berton R., Lixandrão M. E., Pinto E. S. C. M., Tricoli V. (2018). Effects of weightlifting exercise, traditional resistance and plyometric training on countermovement jump performance: a meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. 36, 2038–2044. doi:10.1080/02640414.2018.1434746

Berton R., Silva D. D. D., Santos M. L. D., Silva C., Tricoli V. (2022). Weightlifting derivatives vs. plyometric exercises: effects on unloaded and loaded vertical jumps and sprint performance. PLoS One 17, e0274962. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274962

Booth M. A., Orr R. (2016). Effects of plyometric training on sports performance. Strength Cond. J. 38, 30–37. doi:10.1519/ssc.0000000000000183

Boraczyński M., Magalhães J., Nowakowski J. J., Laskin J. J. (2023). Short-term effects of lower-extremity heavy resistance versus high-impact plyometric training on neuromuscular functional performance of professional soccer players. Sports 11, 193. doi:10.3390/sports11100193

Bouguezzi R., Chaabene H., Negra Y., Ramirez-Campillo R., Jlalia Z., Mkaouer B., et al. (2020). Effects of different plyometric training frequencies on measures of athletic performance in prepuberal Male soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 34, 1609–1617. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002486

Burnie L., Barratt P., Davids K., Stone J., Worsfold P., Wheat J. (2018). Coaches’ philosophies on the transfer of strength training to elite sports performance. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coa. 13, 729–736. doi:10.1177/1747954117747131

Canavan P. K., Garrett G. E., Armstrong L. E. (1996). Kinematic and kinetic relationships between an olympic-style lift and the vertical jump. J. Strength Cond. Res. 10, 127–130. doi:10.1519/00124278-199605000-00014

Channell B. T., Barfield J. P. (2008). Effect of olympic and traditional resistance training on vertical jump improvement in high school boys. J. Strength Cond. Res. 22, 1522–1527. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318181a3d0

Chatzinikolaou A., Fatouros I. G., Gourgoulis V., Avloniti A., Jamurtas A. Z., Nikolaidis M. G., et al. (2010). Time course of changes in performance and inflammatory responses after acute plyometric exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 24, 1389–1398. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d1d318

Chimera N. J., Swanik K. A., Swanik C. B., Straub S. J. (2004). Effects of plyometric training on muscle-activation strategies and performance in female athletes. J. Athl. Train. 39, 24–31.

Ciacci S., Bartolomei S. (2018). The effects of two different explosive strength training programs on vertical jump performance in basketball. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 58, 1375–1382. doi:10.23736/S0022-4707.17.07316-9

Comfort P., Haff G. G., Suchomel T. J., Soriano M. A., Pierce K. C., Hornsby W. G., et al. (2023). National strength and conditioning association position statement on weightlifting for sports performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 37, 1163–1190. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004476

Cormie P., Mccaulley G. O., Triplett N. T., Mcbride J. M. (2007). Optimal loading for maximal power output during lower-body resistance exercises. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc 39, 340–349. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000246993.71599.bf

Cormie P., Mcguigan M. R., Newton R. U. (2011a). Developing maximal neuromuscular power: part 1--biological basis of maximal power production. Sports Med. 41, 17–38. doi:10.2165/11537690-000000000-00000

Cormie P., Mcguigan M. R., Newton R. U. (2011b). Developing maximal neuromuscular power: part 2 - training considerations for improving maximal power production. Sports Med. 41, 125–146. doi:10.2165/11538500-000000000-00000

Crewther B. T., Christian C. (2010). Relationships between salivary testosterone and cortisol concentrations and training performance in olympic weightlifters. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 50, 371–375.

Crewther B. T., Heke T., Keogh J. W. (2011). The effects of training volume and competition on the salivary cortisol concentrations of olympic weightlifters. J. Strength Cond. Res. 25, 10–15. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181fb47f5

Drinkwater E. J., Lane T., Cannon J. (2009). Effect of an acute bout of plyometric exercise on neuromuscular fatigue and recovery in recreational athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 23, 1181–1186. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31819b79aa

Ebben W. P. (2009). Hamstring activation during lower body resistance training exercises. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 4, 84–96. doi:10.1123/ijspp.4.1.84

Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj 315, 629–634. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Flanagan E. P., Comyns T. M. (2008). The use of contact time and the reactive strength index to optimize fast stretch-shortening cycle training. Strength Cond. J. 30, 32–38. doi:10.1519/ssc.0b013e318187e25b

Folland J. P., Williams A. G. (2007). The adaptations to strength training: morphological and neurological contributions to increased strength. Sports Med. 37, 145–168. doi:10.2165/00007256-200737020-00004

Fouré A., Nordez A., Cornu C. (2010). Plyometric training effects on achilles tendon stiffness and dissipative properties. J. Appl. Physiol. 109, 849–854. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01150.2009

Fry A. C. (2004). The role of resistance exercise intensity on muscle fibre adaptations. Sports Med. 34, 663–679. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434100-00004

Fry A. C., Kraemer W. J., Van Borselen F., Lynch J. M., Marsit J. L., Roy E. P., et al. (1994a). Performance decrements with high-intensity resistance exercise overtraining. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 26, 1165–1173. doi:10.1249/00005768-199409000-00015

Fry A. C., Kraemer W. J., Van Borselen F., Lynch J. M., Triplett N. T., Koziris L. P., et al. (1994b). Catecholamine responses to short-term high-intensity resistance exercise overtraining. J. Appl. Physiol. 77, 941–946. doi:10.1152/jappl.1994.77.2.941

Fry A. C., Schilling B. K., Staron R. S., Hagerman F. C., Hikida R. S., Thrush J. T. (2003). Muscle fiber characteristics and performance correlates of Male olympic-style weightlifters. J. Strength Cond. Res. 17, 746–754. doi:10.1519/1533-4287(2003)017<0746:mfcapc>2.0.co;2

Fry A. C., Schilling B. K., Weiss L. W., Chiu L. Z. (2006). beta2-Adrenergic receptor downregulation and performance decrements during high-intensity resistance exercise overtraining. J. Appl. Physiol. 101, 1664–1672. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01599.2005

Garhammer J. (1993). A review of power output studies of olympic and powerlifting: methodology, performance prediction, and evaluation tests. J. Strength Cond. Res 7, 76–89. doi:10.1519/1533-4287(1993)007<0076:aropos>2.3.co;2

Gruber M., Gruber S. B., Taube W., Schubert M., Beck S. C., Gollhofer A. (2007). Differential effects of ballistic versus sensorimotor training on rate of force development and neural activation in humans. J. Strength Cond. Res. 21, 274–282. doi:10.1519/00124278-200702000-00049

Hackett D., Davies T., Soomro N., Halaki M. (2016). Olympic weightlifting training improves vertical jump height in sportspeople: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 50, 865–872. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094951

Haff G. G., Carlock J. M., Hartman M. J., Kilgore J. L., Kawamori N., Jackson J. R., et al. (2005). Force-time curve characteristics of dynamic and isometric muscle actions of elite women olympic weightlifters. J. Strength Cond. Res. 19, 741–748. doi:10.1519/R-15134.1

Haff G. G., Ruben R. P., Lider J., Twine C., Cormie P. (2015). A comparison of methods for determining the rate of force development during isometric midthigh clean pulls. J. Strength Cond. Res. 29, 386–395. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000705

Häkkinen K., Kallinen M. (1994). Distribution of strength training volume into one or two daily sessions and neuromuscular adaptations in female athletes. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 34, 117–124.

Hartman M. J., Clark B., Bembens D. A., Kilgore J. L., Bemben M. G. (2007). Comparisons between twice-daily and once-daily training sessions in male weight lifters. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2, 159–169. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2.2.159

Hawkins S. B., Doyle T. L., Mcguigan M. R. (2009). The effect of different training programs on eccentric energy utilization in college-aged males. J. Strength Cond. Res. 23, 1996–2002. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b3dd57

Hedrick A., Wada H. (2008). Weightlifting movements: do the benefits outweigh the risks? Strength Cond. J. 30, 26–35. doi:10.1519/ssc.0b013e31818ebc8b

Helland C., Hole E., Iversen E., Olsson M. C., Seynnes O., Solberg P. A., et al. (2017). Training strategies to improve muscle power: is olympic-style weightlifting relevant? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 49, 736–745. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001145

Higgins J. P., Li T., Deeks J. J. (2019). Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. Cochrane Handb. Syst. Rev. Interventions, 143–176. doi:10.1002/9781119536604.ch6

Hoffman J. R., Cooper J., Wendell M., Kang J. (2004). Comparison of olympic vs. traditional power lifting training programs in football players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 18, 129–135. doi:10.1519/1533-4287(2004)018<0129:coovtp>2.0.co;2

Ita S., Guntoro T. S. (2018). The effect of plyometric and resistance training on muscle power, strength, and speed in young adolescent soccer players. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 9, 1450. doi:10.5958/0976-5506.2018.00936.1

Jensen R. L., Ebben W. P. (2005). “Ground and knee joint reaction forces during variations of plyometric exercises,” in 23 International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports. ISBS-Conference Proceedings Archive.

Komi P. V. (1984). Physiological and biomechanical correlates of muscle function: effects of muscle structure and stretch-shortening cycle on force and speed. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 12, 81–122. doi:10.1249/00003677-198401000-00006

Komi P. V. (2000). Stretch-shortening cycle: a powerful model to study normal and fatigued muscle. J. Biomech. 33, 1197–1206. doi:10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00064-6

Macaluso F., Isaacs A. W., Myburgh K. H. (2012). Preferential type II muscle fiber damage from plyometric exercise. J. Athl. Train. 47, 414–420. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-47.4.13

Macdonald C. J., Lamont H. S., Garner J. C. (2012). A comparison of the effects of 6 weeks of traditional resistance training, plyometric training, and complex training on measures of strength and anthropometrics. J. Strength Cond. Res. 26, 422–431. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318220df79

Malisoux L., Francaux M., Nielens H., Renard P., Lebacq J., Theisen D. (2006). Calcium sensitivity of human single muscle fibers following plyometric training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 38, 1901–1908. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000232022.21361.47

Markovic G., Mikulic P. (2010). Neuro-musculoskeletal and performance adaptations to lower-extremity plyometric training. Sports Med. 40, 859–895. doi:10.2165/11318370-000000000-00000

Markovic G., Jukic I., Milanovic D., Metikos D. (2007). Effects of sprint and plyometric training on muscle function and athletic performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 21, 543–549. doi:10.1519/R-19535.1

Mero A., Komi P. V. (1986). Force-EMG-and elasticity-velocity relationships at submaximal, maximal and supramaximal running speeds in sprinters. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 55, 553–561. doi:10.1007/BF00421652

Morris S. J., Oliver J. L., Pedley J. S., Haff G. G., Lloyd R. S. (2022). Comparison of weightlifting, traditional resistance training and plyometrics on strength, power and speed: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Med. 52, 1533–1554. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01627-2

Muehlbauer T., Gollhofer A., Granacher U. (2015). Associations between measures of balance and lower-extremity muscle strength/power in healthy individuals across the lifespan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 45, 1671–1692. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0390-z

Negra Y., Chaabene H., Stöggl T., Hammami M., Chelly M. S., Hachana Y. (2020). Effectiveness and time-course adaptation of resistance training vs. plyometric training in prepubertal soccer players. J. Sport Health Sci. 9, 620–627. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2016.07.008

Oranchuk D. J., Robinson T. L., Switaj Z. J., Drinkwater E. J. (2019). Comparison of the hang high pull and loaded jump squat for the development of vertical jump and isometric force-time characteristics. J. Strength Cond. Res. 33, 17–24. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001941

Ostrowski K. J., Wilson G. J., Weatherby R., Murphy P. W., Lyttle A. D. (1997). The effect of weight training volume on hormonal output and muscular size and function. J. Strength Cond. Res. 11, 148–154. doi:10.1519/00124278-199708000-00003

Page M. J., Mckenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T. C., Mulrow C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj 372, n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

Ribeiro J., Teixeira L., Lemos R., Teixeira A. S., Moreira V., Silva P., et al. (2020). Effects of plyometric versus optimum power load training on components of physical fitness in young male soccer players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 15, 222–230. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2019-0039

Shurley J. P., Todd J. S. (2012). “The strength of nebraska”: Boyd epley, husker power, and the formation of the strength coaching profession. J. Strength Cond. Res. 26, 3177–3188. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823c4690

Shuster J. J. (2011). Review: cochrane handbook for systematic reviews for interventions, version 5.1.0, published 3/2011. Julian P.T. higgins and sally green, editors. Res. Synth. Methods 2, 126–130. doi:10.1002/jrsm.38

Simenz C. J., Dugan C. A., Ebben W. P. (2005). Strength and conditioning practices of national basketball association strength and conditioning coaches. J. Strength Cond. Res. 19, 495–504. doi:10.1519/15264.1

Stone M. H., Hornsby W. G., Suarez D. G., Duca M., Pierce K. C. (2022). Training specificity for athletes: emphasis on strength-power training: a narrative review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 7, 102. doi:10.3390/jfmk7040102

Storey A., Smith H. K. (2012). Unique aspects of competitive weightlifting: performance, training and physiology. Sports Med. 42, 769–790. doi:10.1007/BF03262294

Suchomel T. J., Comfort P., Stone M. H. (2015). Weightlifting pulling derivatives: rationale for implementation and application. Sports Med. 45, 823–839. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0314-y

Suchomel T. J., Nimphius S., Stone M. H. (2016). The importance of muscular strength in athletic performance. Sports Med. 46, 1419–1449. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0486-0

Teo S. Y., Newton M. J., Newton R. U., Dempsey A. R., Fairchild T. J. (2016). Comparing the effectiveness of a short-term vertical jump vs. weightlifting program on athletic power development. J. Strength Cond. Res. 30, 2741–2748. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001379

Tesch P. A., Thorsson A., Kaiser P. (1984). Muscle capillary supply and fiber type characteristics in weight and power lifters. J. Appl. Physiol. Respir. Environ. Exerc. Physiol. 56, 35–38. doi:10.1152/jappl.1984.56.1.35

Thrush J. T. (1995). A simplified approach to program design for elite junior weightlifters. Strength Cond. J. 17, 16–18. doi:10.1519/1073-6840(1995)017<0016:asatpd>2.3.co;2

Todd T. (2008). Al roy: the first modern strength coach. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 79, 14–16. doi:10.1080/07303084.2008.10598224

Tofas T., Jamurtas A. Z., Fatouros I., Nikolaidis M. G., Koutedakis Y., Sinouris E. A., et al. (2008). Plyometric exercise increases serum indices of muscle damage and collagen breakdown. J. Strength Cond. Res. 22, 490–496. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31816605a0

Tomalka A., Weidner S., Hahn D., Seiberl W., Siebert T. (2020). Cross-bridges and sarcomeric non-cross-bridge structures contribute to increased work in stretch-shortening cycles. Front. Physiol. 11, 921. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.00921

Toumi H., Best T. M., Martin A., Poumarat G. (2004). Muscle plasticity after weight and combined (weight + jump) training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 36, 1580–1588. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000139896.73157.21

Tricoli V., Lamas L., Carnevale R., Ugrinowitsch C. (2005). Short-term effects on lower-body functional power development: weightlifting vs. vertical jump training programs. J. Strength Cond. Res. 19, 433–437. doi:10.1519/R-14083.1

Turner A. N., Jeffreys I. (2010). The stretch-shortening cycle: proposed mechanisms and methods for enhancement. Strength Cond. J. 32, 87–99. doi:10.1519/ssc.0b013e3181e928f9

Vissing K., Brink M., Lønbro S., Sørensen H., Overgaard K., Danborg K., et al. (2008). Muscle adaptations to plyometric vs. resistance training in untrained young men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 22, 1799–1810. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318185f673

Vosburg E., Hinkey M., Meyers R., Csonka J., Salesi K., Siesel T., et al. (2022). The association between lower extremity strength ratios and the history of injury in collegiate athletes. Phys. Ther. Sport 55, 55–60. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2022.02.004

Watkins P. (2009). The stretch shortening cycle: a brief overview. Adv. Strength Cond. Res. 1, 7–12.

Watkins C. M., Storey A. G., Mcguigan M. R., Gill N. D. (2021). Implementation and efficacy of plyometric training: bridging the gap between practice and research. J. Strength Cond. Res. 35, 1244–1255. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003985

Whitehead M. T., Scheett T. P., Mcguigan M. R., Martin A. V. (2018). A comparison of the effects of short-term plyometric and resistance training on lower-body muscular performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 32, 2743–2749. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002083

Wilson G. J., Newton R. U., Murphy A. J., Humphries B. J. (1993). The optimal training load for the development of dynamic athletic performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 25, 1279–1286. doi:10.1249/00005768-199311000-00013

Young W. B. (2006). Transfer of strength and power training to sports performance. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 1, 74–83. doi:10.1123/ijspp.1.2.74

Young W. B., Bilby G. E. (1993). The effect of voluntary effort to influence speed of contraction on strength, muscular power, and hypertrophy development. J. Strength Cond. Res. 7, 172–178. doi:10.1519/00124278-199308000-00009

Keywords: olympic weightlifting, plyometric training, stretch-shortening cycle, strength, jump, sprint

Citation: Wang S, Zhen J and Xiao T (2025) Effects of three strength training methods on lower extremity strength, jump and sprint performance: a network meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 16:1637520. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1637520

Received: 29 May 2025; Accepted: 28 October 2025;

Published: 02 December 2025.

Edited by:

Gudberg K. Jonsson, University of Iceland, IcelandReviewed by:

Milos Petrovic, University of Iceland, IcelandSoufiane Kaabi, Université de Pau et des Pays de l'Adour, France

Copyright © 2025 Wang, Zhen and Xiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tao Xiao, eGlhb3Rhb0B6enUuZWR1LmNu

†ORCID: Jie Zhen, orcid.org/0009-0004-2032-0180; Shaohui Wang, orcid.org/0009-0002-3744-9154; Tao Xiao, orcid.org/0009-0009-6719-6347

Shaohui Wang

Shaohui Wang Jie Zhen†

Jie Zhen† Tao Xiao

Tao Xiao